Abstract

The present investigation examined the interaction of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness in regard to levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms among people with HIV/AIDS. Participants included 98 (31 women; Mage = 44.97 years, SD = 7.70) adults with HIV/AIDS. As predicted, there was a significant interaction for disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness in regard to anxiety symptoms. Individuals who endorsed both higher levels of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and lower levels of mindful-based attention and awareness reported the greatest degrees of anxiety symptoms, while those endorsing both lower levels of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and higher levels of mindful-based attention and awareness reported the lowest levels of anxiety symptoms. Although the interaction for depressive symptoms was not significant, a conceptually similar pattern of results was observed. Also consistent with prediction, the main effects of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness were significantly positively and negatively associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms, respectively. Findings suggest that certain self-regulatory styles may be important factors to consider in better understanding emotional vulnerability among persons living with HIV/AIDS.

Keywords: Anxiety, Coping, Depression, HIV/AIDS, Mindfulness, Stigma

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an infectious disease that is transmitted via exposure to contaminated bodily fluids (e.g., blood, semen). The recognition of HIV and its progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is now widely recognized as a pandemic problem (United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS] & World Health Organization [WHO], 2007). Estimates from empirical work suggest that 33 million individuals worldwide are currently infected with HIV and approximately 2 million have died from AIDS within the last year (UNAIDS & WHO, 2007). Although significant clinical progress has been made in regard to the treatment and disease management of HIV/AIDS in recent years (e.g., Lima et al., 2007), efforts to understand the psychosocial consequences of this disease are only beginning to emerge.

One body of work addressing psychosocial factors related to HIV/AIDS suggests this disease may be linked to clinically meaningful affective symptoms and problems. There are at least three streams of empirical evidence that indicate an association between HIV/AIDS and dysfunctional or personally problematic negative affective experiences. First, studies have found that life stress is a common experience among persons living with HIV/AIDS (Catz, Gore-Felton & McClure, 2002; Leserman, 2003; Siegel, Schrimshaw & Pretter, 2005). Specifically, persons living with HIV/AIDS commonly experience clinically significant negative affective symptoms due to suffering from the physical and social aspects of the medical illness (e.g., symptom onset and management, stigma related to the disease; Siegel et al., 2005). These same HIV/AIDS infected individuals also report a higher incidence of life stressors not related to the disease (e.g., abuse history) than their counterparts without HIV/AIDS (Leserman, Whetten, Lowe, Strangl, Schwartz, & Thielman, 2005). Second, although some initial work indicated that there might not be a robust relation between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders (e.g. Chuang, Jason, Pajurkova, & Gill, 1992; Rabkin, Ferrando, Jacobsberg, & Fishman, 1997), other studies have consistently supported a linkage (Maj, Janssen et al., 1994). In a meta analysis of extant work on this topic, Ciesla and Roberts (2001) found that persons with HIV/AIDS were approximately two times more likely to have a history of major depressive disorder than individuals not infected with the virus. Subsequent investigations have also supported a depression-HIV association (Bing et al., 2001; Cruess et al., 2003; Morrison et al., 2002). And finally, although anxiety symptoms and disorders have been relatively less intensively studied than depression in the HIV/AIDS literature, emerging work highlights a relationship (Kimerling, Calhoun, Forehand et al., 1999; Olley, Zeier, Seedat, & Stein, 2005; Smith, Egert, Winkel, & Jacobson, 2002; Tsao, Doubalian, Moreau, & Dobalian, 2004). The most consistent relations appear to be with traumatic stress symptoms as well as posttraumatic stress disorder (Kimerling et al., 1999; Tedstone & Tarrier, 2003), generalized anxiety (Haller & Miles, 2003; Tsao et al., 2004), and to a lesser extent, panic psychopathology (Bing et al., 2001; Orlando, Burnam et al., 2001).

Whereas past work has largely focused on documenting a relation between HIV/AIDS and negative emotional symptoms and disorders (Bing et al., 2001; Cruess et al., 2003; Morrison et al., 2002), considerably less attention has focused on processes that may underlie such associations. One line of inquiry has begun to focus on how an individual responds (i.e., self regulatory behavior) to HIV/AIDS-related stress. Drawing from stress and coping models of risk and resiliency (e.g., Masten, 1994), some work has indicated that avoidant coping longitudinally predicts greater HIV disease progression (Ironson et al., 2005) and denial coping predicts more rapid progression to AIDS (Ironson et al., 1994; Leserman et al., 2002) as well as increased risk of mortality (Ironson et al., 1994). One important life stressor that may promote emotional distress (e.g., anxiety and depressive symptoms) in the lives of persons living with HIV/AIDS is stigma related to the disease (Bunn, Solomon, Miller, & Forehand, 2007; Clark, Linder, Armistead, & Austin, 2003; Silver, Bauman, Camacho, & Hudis, 2003). Indeed, a number of studies report that HIV/AIDS-related stigma is associated with poor psychological outcome. For example, one prospective study has documented that among Asian and Pacific Islanders with HIV/AIDS, HIV/AIDS-related stigma predicted increased psychological distress (including anxiety and depressive symptoms; Kang, Rapkin, & DeAlmeida, 2006). Other work indicates that HIV/AIDS-related stigma is related to decreased global psychological functioning and self-esteem (Clark et al., 2003, Bunn, Solomon, Miller, & Forehand, 2007; Preston, D’Augelli, Kassab, & Starks, 2007) and increased levels of anxiety and depression symptoms (Lee, Kochman, & Sikkema, 2002; Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, 2001; Vanable, Carey, Blair, & Littlewood, 2006). Despite the apparent effects of HIV/AIDS-related stigma on psychological health, empirical research has not extensively examined the ways in which coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma, specifically, is related to depressive and anxiety symptoms. One exception is a recent study by Varni, Miller, Gonzalez, Cassidy, and Solomon (under review) who found that disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma is associated with higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. These findings are broadly consistent with theory and research on self-regulation, whereby disengagement responses to aversive life events (e.g., HIV/AIDS-related stigma) are utilized in the short-term in an attempt to reduce aversive affective states, but yield longer-term negative emotional consequences (e.g., greater levels of affective symptoms; Compas et al., 2001; Feldner, Zvolensky, & Leen-Feldner, 2004; Mineka, 1985).

Another self-regulatory factor of possible relevance to better understanding anxiety and depressive symptoms among persons with HIV/AIDS is mindfulness. In general, there has been a recent and wide-spread proliferation of mindfulness-based conceptualizations of psychological vulnerability and treatments for addressing affective symptoms and disorders as well as other clinical conditions (Eifert & Forsyth, 2005; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999; Kabat-Zinn, Lipworth, Burney, & Sellers, 1986; Linehan, 1993; Parks, Anderson & Marlatt, 2001; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002; Walser & Westrup, 2007). Brown and Ryan (2003) have developed a theoretically-grounded and empirically promising self-report measure entitled the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), which assesses individual differences in the frequency of mindful states over time (MacKillop & Anderson, 2007). According to Brown and Ryan (2003), mindful-based attention and awareness, as indexed by the MAAS, denotes conscious “attention to, and awareness of, what is occurring in the present moment” (p. 824). Some initial work has demonstrated that higher levels of mindfulness, as indexed by self-reported mindful attention and awareness, have been concurrently associated with both lower anxiety (Vujanovic, Zvolensky, Bernstein, Feldner, & McLeish, 2007) and depressive symptoms (Zvolensky, Solomon et al., 2006) among non-HIV/AIDS adult populations. It remains unclear, however, whether mindful-based attention and awareness is similarly related to the expression of anxiety and depression symptoms among persons living with HIV/AIDS. To the extent mindful-based attention and awareness promotes a more adaptive self-aware stance, persons living with HIV/AIDS may be less prone to react in a dysfunctional manner (e.g., catastrophizing) to HIV/AIDS-related and other life stressors.

Beyond the main effects of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness, it is possible these factors also may interact in a clinically-meaningful way in regard to anxiety and depressive symptoms. We theorized that mindful-based attention and awareness might interact with disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma to significantly alter vulnerability for depressive and anxiety symptoms. Specifically, given the negative associations between mindful-based attention and awareness and anxiety and depressive symptoms in past work (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Vujanovic et al., 2007; Zvolensky et al., 2006), higher levels of mindful-based attention and awareness may weaken the expected positive association between higher levels of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and negative affect variables. Similarly, lower levels of mindful-based attention and awareness and higher levels of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma may be the combination associated with the highest levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Together, the present investigation sought to replicate and uniquely extend prior findings (Varni et al., under review) by examining the singular and interactive relations of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness in regard to anxiety and depressive symptoms among adults currently living with HIV/AIDS. First, it was hypothesized that disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma would be concurrently associated with greater levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. This hypothesis was based on Varni et al.’s (under review) past work that suggests disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma is related to greater anxiety and depressive symptoms among persons living with HIV/AIDS and that disengagement coping, in general, is related to greater disease-related impairment among persons living with HIV/AIDS (Ironson et al., 1994; Leserman et al., 2002). Second, it was hypothesized that mindful-based attention and awareness would be associated with lesser levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. This hypothesis was derived from previous research that suggests mindful-based attention and awareness is associated with lesser levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms among non-HIV/AIDS populations (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Vujanovic et al., 2006; Zvolensky et al., 2006). Finally, it was hypothesized that disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma would interact with mindful-based attention and awareness in the prediction of anxiety and depressive symptoms above and beyond the variance accounted for by the individual main effects. Specifically, it was hypothesized that higher levels of mindful-based attention and awareness would weaken the associations between higher levels of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and greater degrees of anxiety and depressive symptoms. In a related fashion, it was further hypothesized that lower levels of mindful-based attention and awareness and higher degrees of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma would be associated with the highest levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Method

Participants

Participants included 98 (31 women; Mage = 44.97 years, SD = 7.70; observed range = 24 – 64) people with HIV/AIDS who participated in a previous study (see Bunn et al., 2007). These participants were originally recruited through AIDS Service Organizations (ASO’s), Comprehensive Care Clinics, advertisements in local newspapers, and word of mouth in Vermont, New Hampshire, and areas of Massachusetts and Maine, and agreed to be contacted for future studies. The racial/ethnic distribution of the sample was 85.7% Caucasian, 2% African American, 7.1% Latino/a, 3.1% Native American, and 2% “other.” 39.8% of the sample identified as exclusively heterosexual, 46.9% as exclusively homosexual, 9.2% as bisexual, and 4.1% as neither exclusively heterosexual nor exclusively homosexual. Although 91.9% of the sample reported having at least a high school or equivalent (G.E.D.) degree, more than half (63.6%) reported being unemployed, with the majority of participants (64.3%) reporting a household income under $20,000. More than half of the sample (58.2%) reported having a spouse or partner. Participants were eligible for this study if they were at least 18 years of age and self-reported having a HIV or AIDS diagnosis. Exclusionary criteria for the investigation included limited mental competency (indexed by not being oriented to person, place, or time) or the inability to provide informed, written consent during the consenting process of the previous study (see Bunn et al., 2007).

Measures

The Response to Stress Questionnaire-HIV/AIDS Stigma (RSQ; Connor-Smith, Compas, Wadsworth, Thomsen, & Saltzman, 2000) assesses self-regulatory responses to a stressor as described by Compas et al.’s (2001) theoretical coping model, including disengagement coping (DE-Coping) and primary and secondary control engagement coping. The questionnaire can be adapted to direct the participants’ focus towards a particular source of stress. In this study, participants were directed to think about how the stigma of HIV/AIDS caused them to experience stress. Participants reported different ways that the stigma of HIV/AIDS caused them stress and indicated how stressful each problem was for them and how much control they believed they had over the problem on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 4 = very). Participants could report up to 10 ways in which the stigma of HIV/AIDS was stressful to them and were asked to think about the most stressful problem reported as a reference for the rest of the questionnaire. Participants were then asked to indicate on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 4 = a lot) how much they used each listed strategy to cope with that particular problem.

This study, specifically, utilized the DE-Coping subscale. The DE-Coping subscale consists of 9 items assessing avoidance (e.g., ‘I try not to think about it, to forget all about it.’), denial (e.g., ‘When I am around other people I act like the problems related to the stigma of HIV/AIDS never happened.’), and wishful thinking (e.g., ‘I deal with the problems related to the stigma of HIV/AIDS by wishing they would just go away, that everything would work itself out.’). All items are coded so that higher scores indicate using DE-Coping strategies more often. The DE-Coping subscale demonstrated good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .78.

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003) is a 15-item questionnaire on which participants indicate, on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = almost always to 6 = almost never), their lack of attention and awareness to present events and experiences. All items of the MAAS are scored such that a higher score represents greater attention and awareness paid to present activities and experiences. When participants were administered the MAAS for the current study, an extra anchor was added to the scale (7 = I don’t know). To remain consistent with the original validation and scoring of the MAAS, all scores of 7 were counted as missing data. Only participants answering at least half (8 items) of the scale items were included in analyses (only 3 participants were removed). Individual means were computed so that missing values did not distort the mean. Each mean was then multiplied by 15 to allow for all scores to be on the same scale. The MAAS has shown good internal consistency and construct validity across a wide range of samples (α = .80 – .87; Brown & Ryan, 2003; MacKillop & Anderson, 2007; Vujanovic et al., 2007; Zvolensky et al., 2006) and has evidenced high internal consistency in the present sample (α = .90).

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1993) is a 21-item questionnaire on which participants indicate on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all to 3 = severely) the degree to which they were bothered by each symptom of anxiety in the past week. Higher scores are indicative of greater anxiety symptom severity. The BAI has demonstrated both good internal consistency and convergent validity in past research (Steer, Ranieri, Beck, & Clark, 1993) and in the current study (α = .93).

The Beck Depression Inventory- II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a 21-item questionnaire that assesses the severity of depression symptoms. Since many of the somatic symptoms of depression overlap with HIV-specific symptoms, only the first 12 items, which are representative of the cognitive-affective depression subscale (Beck & Steer, 1993), were utilized for analyses. This method of examining depression is consistent with previous work on HIV/AIDS and depression (Kalichman, Sikkema, & Somlai, 1995). The severity of each symptom is rated on a Likert-type scale from 0 to 3. Total scores (sum of items) greater than 10 are indicative of clinical depression. The overall BDI-II has demonstrated high internal consistency and reliability, as well as good convergent and discriminant validity (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996; Steer & Beck, 2000). The cognitive-affective depression subscale evidenced high internal consistency in the present sample (α = .93).

Procedure

Participants were first contacted by phone to confirm their interest in participating in the study. They were then mailed a packet of measures with instructions for completing and returning the packet in the addressed and pre-paid envelope provided to them. Participants that returned the packet were mailed a 60-minute phone card for completing the measures. Of the 133 individuals contacted, 98 (73.68%) returned the completed measures packet. This study was approved by the University of Vermont Institutional Review Board.

Data Analytic Strategy

Criterion variables in the hierarchical regression analyses included the BAI and the BDI-II scores. The main effects of DE-Coping and the MAAS-Total scores (mean centered) were simultaneously entered at step 1. At step 2, the interaction of DE-Coping and MAAS-Total scores were entered. To examine the form of significant interactions, following Cohen and Cohen (1983, p. 323), symptom values were computed by inserting specific values for each predictor variable (e.g., one-half standard deviation above and below the mean of the predictor variables) into the regression equations associated with the described analysis.

Results

Descriptive Data and Correlations among Theoretically-Relevant Variables

Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations of all variables are reported in Table I. The DE-Coping variable was negatively related to MAAS-Total; these variables shared 24% variance with one another. The DE-Coping factor was strongly significantly positively associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms (r = .59 and .61, respectively). Similarly, the MAAS-Total score was strongly significantly negatively correlated to anxiety and depressive symptoms (r = −.59 and −.64, respectively).

Table I.

Descriptive Data and Zero-order Relations between Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DE-Coping1 | --- | −.49** | .61** | .59** | 2.33 | 0.65 | 1.00–3.78 |

| 2 | MAAS-Total2 | --- | −.59** | −.64** | 61.14 | 16.77 | 20.36–90 | |

| 3 | BAI3 | --- | .73** | 16.21 | 13.05 | 0–49 | ||

| 4 | BDI-II4 | --- | 9.37 | 8.07 | 0–31 |

Note:

= p < .05,

= p < .01,

Disengagement Coping sub-scale, Response to Stress Questionnaire-HIV/AIDS Stigma (RSQ; Connor-Smith et al., 2000),

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003),

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1990),

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996).

Hierarchical Regression Analyses

Please see Table II for a summary of hierarchical regression analyses. For BAI scores, the main effects of DE-Coping and MAAS-Total at step 1 accounted for 48 % of the variance (β =. 42, p < .001 and β = − .39, p < .001, respectively). At step 2, the addition of the interaction term accounted for an additional 3% of the variance (p = .01).

Table II.

Predictors of BAI and BDI-II Scores

| ΔR2 |

t (each predictor) |

β | sr2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: BAI | |||||

| Step 1 | .48 | <.001 | |||

| DE-Coping | 4.88 | .42 | .21 | <.001 | |

| MAAS-Total | − 4.51 | − .39 | .18 | <.001 | |

| Step 2 | .03 | .01 | |||

| DE-Coping × MAAS-Total | − 2.53 | − .19 | .07 | .01 | |

| Dependent variable: BDI-II | |||||

| Step 1 | .51 | <.001 | |||

| DE-Coping | 4.26 | .36 | .17 | <.001 | |

| MAAS-Total | − 5.45 | − .46 | .25 | <.001 | |

| Step 2 | .02 | .08 | |||

| DE-Coping × MAAS-Total | − 1.75 | − .13 | .03 | .08 |

Note: β = standardized beta weights, sr2 = squared semi-partial correlation. DE Coping = Disengagement Coping sub-scale, Response to Stress Questionnaire-HIV/AIDS Stigma (RSQ; Connor-Smith et al., 2000), MAAS-Total = Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003), BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996),

BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1990).

For BDI-II scores, step 1 of the model accounted for 51% of the variance with significant contributions by the main effects of DE-Coping (β =. 36, p < .001) and MAAS-Total (β = − .46, p < .001). At step 2, the addition of the interaction term accounted for an additional 2% of the variance (p = .08).

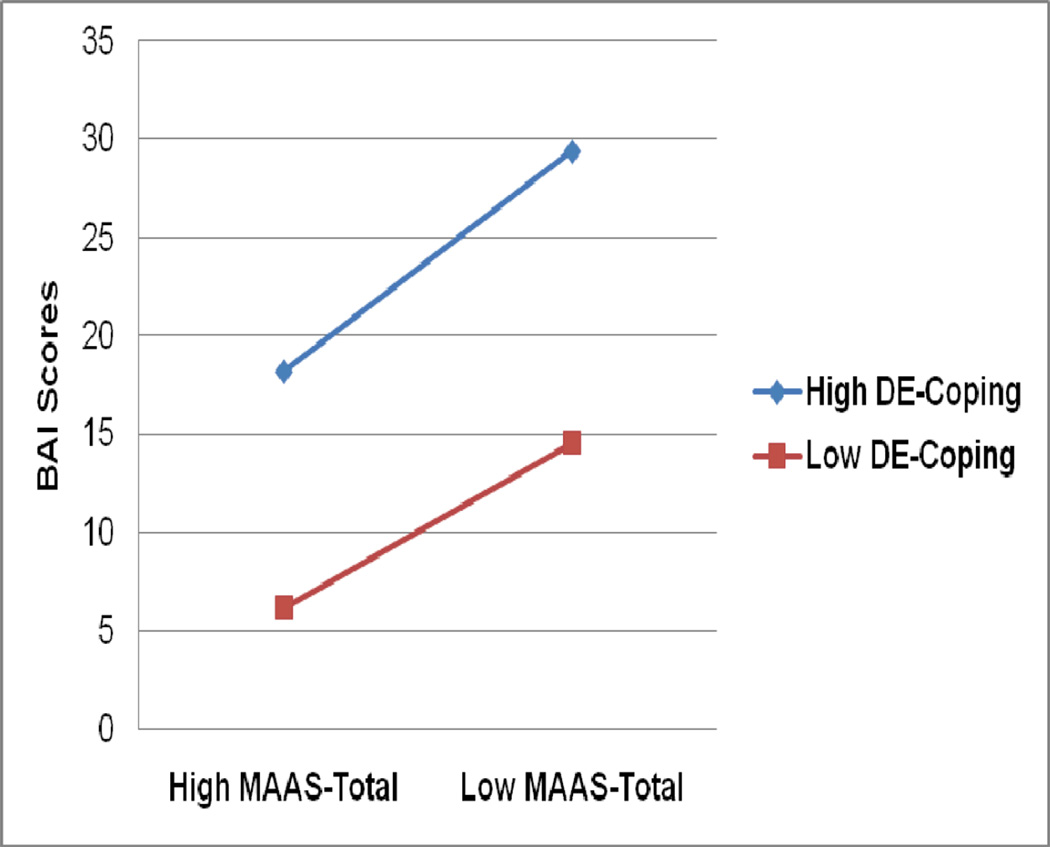

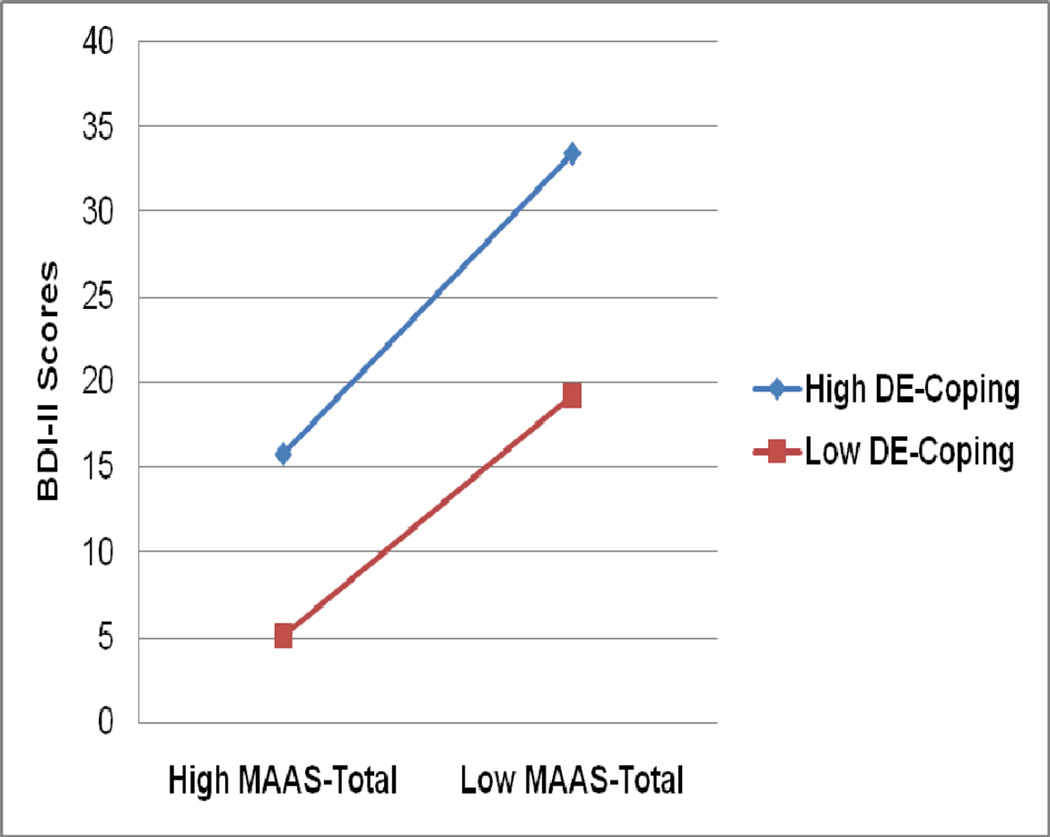

The form of the interactions was examined for each criterion variable by plotting the mean value according to Cohen and Cohen (1983, p. 323). As is evident in Figure 1, the form of the interaction for anxiety symptoms indicates that co-occurring high levels of DE-Coping and low MAAS-Total yield the greatest levels of depressive symptoms. High levels of DE-Coping and high levels of MAAS-Total were largely comparable to low DE-Coping and low MAAS-Total. Individuals with low levels of DE-Coping and high levels of MAAS-Total evidenced the lowest levels of depressive symptoms. Although the interaction for BDI-II scores was not significant, an essentially identical pattern of findings was evident as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

BAI scores as a function of the interaction of DE-Coping and MAAS-Total among participants 0.5 standard deviation above and/or below the mean.

Figure 2.

BDI-II scores as a function of the interaction of DE-Coping and MAAS-Total among participants 0.5 standard deviation above and/or below the mean.

Discussion

Although there is a growing recognition that individuals living with HIV/AIDS may be at increased risk for negative emotional experiences (Catz et al., 2002; Leserman, 2003; Siegel et al., 2005) and one study that suggests disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma is related to anxiety and depressive symptoms (Varni et al., under review), work has not yet explored the role of mindful-based attention and awareness and ways in which this self-regulation factor may interact with disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma in the prediction of anxiety and depressive symptoms. To address this gap in the existing literature, the present study sought to evaluate the interaction of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness in regard to anxiety and depressive symptoms among adults living with HIV/AIDS.

Consistent with expectation, there was a significant interaction for disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness in regard to anxiety symptoms. The size of the observed interaction was 3% of unique variance above and beyond the significant main effects for anxiety symptoms (see Table II). Inspection of the form of the interaction was in accord with the a priori theoretical formulation. Specifically, higher levels of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and lower levels of mindful-based attention and awareness were associated with the greater degrees of anxiety symptoms (see Figure 1). Similarly, lower levels of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and higher levels of mindful-based attention and awareness were associated with the lower levels of anxiety symptoms (see Figure 1). Although the interaction of disengagement coping and mindful attention and awareness regarding depressive symptoms did not meet the traditional significance level (p < .05), a nearly identical conceptual pattern of results were observed. Specifically, the form of the interaction (see Figure 2.) was identical to that of the interaction for anxiety symptoms. Further evaluation of the possible relevance of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness in terms of depressive symptoms is warranted before more firm conclusions are drawn. Overall, this pattern of results highlight the possible clinically-relevant interplay between two theoretically promising self-regulatory variables (disengagement coping and mindful-based attention and awareness) in regard to anxiety, and perhaps depressive, symptoms among persons living with HIV/AIDS.

There also was empirical evidence of significant main effects that were large in effect size for the studied self-regulatory variables in regard to anxiety and depressive symptoms. First, as in past work (Varni et al., under review), there was a significant main effect for disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma, such that higher levels were related to increases in levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Here, the size of the observed relations was large in magnitude, explaining 21% and 17% of variance in the model for anxiety and depressive symptoms, respectively. These findings are consistent with idea that disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma may be related to a greater tendency to experience more intense anxiety and depressive symptoms. Second, there was a significant main effect for mindful-based attention and awareness in regard to anxiety and depressive symptoms. Specifically, higher levels of mindful-based attention and awareness were associated with decreases in levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. A stronger relationship was evident for depressive relative to anxiety symptoms, a pattern in accord with past work focused on this construct (Zvolensky et al., 2006). These findings replicate and uniquely extend past work among non-HIV/AIDS populations denoting a relation between mindful-based attention and awareness and affective vulnerability (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Vujanovic et al., 2006; Zvolensky et al., 2006). Finally, although not the main focus of the present investigation per se, it is noteworthy that disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness were significantly negatively correlated yet shared only 24% variance with one another. This finding is important because it indicates that these two self-regulatory behaviors are tapping different, albeit related, types of putative vulnerability processes for anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Together, a possible implication of the present findings is that there may be segments of the adult population with HIV/AIDS who are at relatively greater risk for anxiety and depressive symptoms by virtue of individual variation in disengagement coping style for HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness. The identification of such interactions is clinically important, as it helps to refine our understanding of complex associations between self-regulatory style and affective vulnerability among persons living with HIV/AIDS. For example, the identification of moderating variables helps to theoretically identify certain subpopulations at greatest risk for affective disturbances that can then ultimately be targeted for specialized intervention (Zvolensky, Schmidt, Bernstein, & Keough, 2006). The current study findings may ultimately suggest that there is merit in exploring the role of self-regulatory processes, namely disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness, as therapeutic processes in regard to anxiety and depressive symptoms among persons with HIV/AIDS. This type of perspective is consistent with a larger clinical literature focused on addressing mindfulness processes as a way to improve psychological health (Eifert & Forsyth, 2005; Kabat-Zinn et al., 1986; Linehan, 1993; Parks et al., 2001; Segal et al., 2002; Walser & Westrup, 2007).

The present study has a number of limitations that deserve further comment. First, due to the cross-sectional and correlational nature of the present research design, it is not possible to make causal statements concerning any of the relevant constructs. One important next step in this line of inquiry would therefore be to use prospective research methodologies to evaluate the consistency of the present findings over time or to experimentally manipulate certain regulatory strategies in the laboratory and test singular and interactive effects to theoretically-relevant stressors (e.g., bodily sensations). Second, although approaching significance, the interaction for depressive symptoms was not significant at the traditional p <.05 level. Here, future work is needed to replicate and further extend these findings. Given that we found an identical pattern of results regarding the form of the interactions for depressive and anxiety symptoms, it may be the case that our sample was not at the magnitude needed for sufficient statistical power to test the interaction for depressive symptom. Third, although the sample was generally representative of the ethnic composition of the state of Vermont and Northern New England, it was comprised of predominately Caucasian older adults. To improve generalizability of the observed effects, future research could sample from locations with more diverse demographic characteristics. Fourth, the current study tested the associations between disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness, a specific mindfulness-based construct (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Mindful attention, as developed by Brown and Ryan (2003), is only one type of mindfulness construct and others have postulated different but related conceptualizations (e.g., Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006; Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Hayes & Feldman, 2004). To continue to build upon the extant mindfulness literature, and to empirically better understand distinctions between various facets of mindfulness, it may be prudent to examine the interplay between disengagement coping and other mindfulness-based constructs (see Baer et al., 2006). Moreover, future inquires may benefit from examining the role of other self-regulatory factors and vulnerability characteristics (e.g., emotional vulnerability, personality facets, other coping mechanisms) to further delineate underlying processes related to anxiety and depression among people living with HIV/AIDS. Fifth, the current study was focused on clarifying the singular and interactive effects of disengagement coping with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and mindful-based attention and awareness at a broad-based level in terms of depressive and anxiety symptoms. The study sample was not large enough to provide a basis to meaningfully examine the role of gender and sexual orientation. Future work may therefore benefit by exploring whether the current findings are similarly evident among both females and males and individuals identifying as gay or heterosexual. Sixth, disease specific data such as severity and stage of illness was not available for inclusion in analyses. Extension and replication of this work may consider controlling for and examine the effects of these characteristics and other HIV/AIDS specific markers (e.g., CD4-T cell count, HIV/AIDS-related symptom distress). Finally, self-report measures were utilized as the primary assessment methodology for many of the key constructs. The utilization of self-report methods does not fully protect against reporting errors and may be influenced by shared method variance. Thus, future studies could build on the present work by utilizing a multi-method approach.

Overall, the current investigation suggests certain self-regulatory styles may be important factors to consider in better understanding emotional vulnerability among persons living with HIV/AIDS. Further investigation of the role of self-regulation processes may aid in developing more efficient and targeted intervention strategies for addressing anxiety and depressive symptoms among persons living with HIV/AIDS.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all members of the Person Environment Zone Projects, especially Tracy Nyerges and Susan E. Varni for their efforts regarding data collection and management.

This research was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health Grant, "Rural Ecology and Coping with HIV Stigma", RO1 MH 066848 obtained by Sondra E. Solomon, Ph.D. and Carol T. Miller, Ph.D. This work also was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health Diversity Supplement (1 R01 MH076629-01) awarded to Adam Gonzalez, and by National Institute of Mental Health and Drug Abuse research grants (1 R01 MH076629-01 and 1 R03 DA16307-01) awarded to Dr. Michael J. Zvolensky.

References

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13:27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. BDI: Beck Depression Inventory manual. New York, NY, US: Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio, TX, US: Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berger B, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing and Health. 2001;24:518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, Turner BJ, Eggan F, Beckman R, Vitiello B, Morton SC, Orlando M, Bozzette SA, Ortiz-Barron L, Shapiro M. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn JY, Solomon SE, Miller CT, Forehand R. Measurement of stigma in people with HIV: A re-examination of the HIV Stigma Scale. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19:198–208. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catz SL, Gore-Felton C, McClure JB. Psychological distress among minority and low-income women living with HIV. Behavioral Medicine. 2002;28:53–59. doi: 10.1080/08964280209596398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang HT, Jason GW, Pajurkova EM, Gill MJ. Psychiatric morbidity in patients with HIV infection. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;37:109–115. doi: 10.1177/070674379203700207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:725–730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HJ, Linder G, Armistead L, Austin B. Stigma, disclosure, and psychological functioning among HIV-infected and non-infected African-American women. Women & Health. 2003;38:57–71. doi: 10.1300/j013v38n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, US: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith JK, Compas BE, Wadsworth ME, Thomsen AH, Saltzman H. Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;66:976–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess DG, Petitto JM, Leserman J, Douglas SD, Gettes DR, Ten Have TR, Evans DL. Depression and HIV infection: Impact on immune functioning and disease progression. CNS Spectrums. 2003;8:52–58. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eifert GH, Forsyth JP. Acceptance and commitment therapy for anxiety disorders: A practitioner’s guide to using mindfulness, acceptance, and values-based behavior change strategies. Oakland, CA, US: New Harbinger Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Feldner MT, Zvolensky MJ, Leen-Feldner E. A critical review of the literature on coping and panic disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:123–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Haller DL, Miles DR. Suicidal ideation among psychiatric patients with HIV: Psychiatric morbidity and quality of life. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;7:101–108. doi: 10.1023/a:1023985906166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AM, Feldman G. Clarifying the construct of mindfulness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of change in therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11:255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Balbin E, Stuetzle R, Fletcher MA, O’Cleirigh C, Laurenceau JP, Schneiderman N, Solomon G. Dispositional optimism and the mechanisms by which it predicts slower disease progression in HIV: Proactive behavior, avoidant coping, and depression. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;12:86–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1202_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Schneiderman H, Kumar M, Antoni MH, et al. Psychosocial stress, endocrine and immune response in HIV-1 disease. Homeostasis in Health and Disease. 1994;35:137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R, Sellers W. Four-year follow-up of a meditation-based stress reduction program for the self-regulation of chronic pain: Treatment outcomes and compliance. Clinical Journal of Pain. 1986;2:159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kang E, Rapkin BD, DeAlmeida C. Are psychological consequences of stigma enduring or transitory? A longitudinal study of HIV stigma and distress among Asians and Pacific Islanders living with HIV illness. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20:712–723. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, Calhoun KS, Forehand R, Armistead L, Morse E, Morse P, Clark R, Clark L. Traumatic stressing HIV-infected women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1999;11:321–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RS, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Internalized stigma among people living with HIV-AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6:309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J. The effects of stressful life events, coping, and cortisol on HIV infection. CNS Spectrums. 2003;8:25–30. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900023439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Petitto JM, Gu H, Gaynes BN, Barroso J, Golden RN, Perkins DO, Folds JD, Evans DL. Progression to AIDS, a clinical AIDS condition and mortality: Psychosocial and physiological predictors. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:1059–1073. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Whetten K, Lowe K, Stangl D, Swartz MS, Thielman NM. How trauma, recent stressful events, and PTSD affect functional health status and health utilization in HIV-infected patients in the south. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67:500–507. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000160459.78182.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima VD, Geller J, Bangsberg DR, Patterson TL, Daniel M, Kerr T, Montaner JSG, Hogg RS. The effect of adherence on the association between depressive and mortality among HIV-infected individuals first initiating HAART. AIDS. 2007;21:1175–1183. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32811ebf57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. In: Linehan MM, editor. Diagnosis and Treatment of Mental Disorders. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Anderson EJ. Further psychometric validation of the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2007;29:289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Maj M, Janssen R, Starace F, Zaudig M, Satz P, Sughondhabirom B, Luabeya MA, Riedel R, Ndetei D, Calil HM. WHO neuropsychiatric AIDS study, cross-sectional phase I: Study design and psychiatric findings. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:39–49. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010039006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Resilience in individual development: Successful adaption despite risk and adversity. In: Wang MC, Gordon EW, editors. Educational Resilience in Inner-city America: Challenges and Prospects. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1994. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S. Animal models of anxiety-based disorders: Their usefulness and limitations. In: Tuma HA, Maser JD, editors. Anxiety and the anxiety disorders. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1985. pp. 194–244. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Have TT, Gettes DR, Chiappini MS, Weber AL, Brinker-Spence P, Bauer RM, Douglas SD, Evans DL. Depression and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:789–796. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olley BO, Zeier MD, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Post-traumatic stress disorder among recently diagnosed patients with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2005;17:550–557. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Burnam A, Beckman R, Morton S, London A, Bing E, Fleishman J. Re-estimating the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a nationally representative sample of persons receiving care for HIV: Results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2001;11(2):75–82. doi: 10.1002/mpr.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks GA, Anderson BK, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention therapy. In: Heather N, Peters TJ, Stockwell T, editors. International Handbook of Alcohol Dependence and Problems. New York, NY, US: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2001. pp. 575–592. [Google Scholar]

- Preston DB, D’Augelli AR, Kassab CD, Starks MT. The relationship of stigma to the sexual risk behavior of rural men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19:218–230. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin JG, Ferrando SJ, Jacobsberg LB, Fishman B. Prevalence of axis I disorders in an AIDS cohort: A cross-sectional, controlled study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1997;38:146–154. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Schrimshaw EW, Pretter S. Stress-related growth among women living with HIV/AIDS: Examination of an explanatory model. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;28:403–414. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver EJ, Bauman LJ, Camacho S, Hudis J. Factors associated with psychological distress in urban mothers with late-stage HIV/AIDS. 2003 doi: 10.1023/b:aibe.0000004734.21864.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MY, Egert J, Winkel G, Jacobsen J. The impact of PTSD on pain experience in personas with HIV/AIDS. Pain. 2002;98:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00431-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Beck AT. The Beck Depression Inventory-II. In: Craighead WE, Nemeroff CB, editors. The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology and behavioral science. 3rd. ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY, US: Wiley; 2000. pp. 178–179. [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Ranieri WF, Beck AT, Clark DA. Further evidence for the validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory with psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1993;7:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Tedstone JE, Tarrier N. Posttraumatic stress disorder following medical illness and treatment. Clinical psychology Review. 2003;23:409–448. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao JC, Dobalian A, Moreau C, Dobalian K. Stability of anxiety and depression in a national sample of adults with human immunodeficiency virus. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192:111–118. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000110282.61088.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, & World Health Organization. AIDS Epidemic Update. AIDS Epidemic Update. 2007 http://data.unaids.org/pub/EPISlides/2007/2007_epiupdate_en.pdf.

- Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:473–782. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni SE, Miller CT, Gonzalez A, Cassidy DG, Solomon SE. The relationship between HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological well-being depends on coping with stigma. (under review) [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, Feldner M, McLeish AC. A test of the interactive effects of anxiety sensitivity and mindfulness in the prediction of anxious arousal, agoraphobic cognitions, and body vigilance. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:1393–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walser RD, Westrup D. Acceptance & Commitment Therapy for the Treatment of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Trauma-related Problems: A Practitioner’s Guide to Using Mindfulness and Acceptance Strategies. Oakland, CA, US: New Harbinger Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB, Bernstein A, Keogh ME. Risk-factor research and prevention programs for anxiety disorders: A translational research framework. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1219–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Solomon SE, McLeish AC, Cassidy D, Bernstein A, Bowman CJ, Yartz AR. Incremental validity of mindfulness-based attention in relation to the concurrent prediction of anxiety and depressive symptomatology and perceptions of health. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2006;35:148–158. doi: 10.1080/16506070600674087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]