Abstract

Objective

To identify strategies with tactics that enable point-of-care (POC) testing (medical testing at or near the site of care) to improve outcomes effectively in emergencies, disasters, and public health crises, especially where community infrastructure is compromised.

Design

Logic model-critical path-feedback identified needs for improving practices. Reverse stress analysis showed POC should be integrated, responders properly trained, and devices staged in small-world networks (SWNs). We summarize first responder POC resources, strategize test clusters, address assay environmental vulnerabilities, and design tactics useful for SWNs, alternate care facilities, shelters, point-of-distribution centers, and community hospitals.

Participants and Environment

Emergency-disaster needs assessment survey respondents and Center experience.

Outcomes

Important tactics are: a) develop training/education courses and “just-in-time” on-line web resources to assure the competency of POC coordinators and high quality testing performance; b) protect equipment from environmental extremes by sealing reagents, controlling temperature and humidity to which they are exposed, and establishing near-patient testing in defined environments that operate within current FDA licensing claims (illustrated with HIV-1/2 tests); c) position testing in defined sites within SWNs and other environments; d) harden POC devices and reagents to withstand wider ranges of environmental extremes in field applications; e) promote new POC technologies for pathogen detection and other assays, per needs assessment results; and f) select tests according to mission objectives and value propositions.

Conclusions

Careful implementation of POC testing will facilitate evidence-based triage, diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of victims and patients, while advancing standards of care in emergencies and disasters, as well as public health crises.

Keywords: Alternate care facility (ACF), bedside testing, crisis standard of care, critical path, emergency medical system (EMS), environmental stress, near-patient testing (NPT), needs assessment, point of distribution, reverse stress analysis, therapeutic turnaround time (TTAT), triage, small-world network (SWN), shelter, value proposition

GOAL

The goal of this paper is to present a framework whereby point-of-care (POC) testing, defined as medical testing at or near the site of care, will enhance crisis standards of care in emergencies, disasters, and devastating conditions, such as pandemic influenza in the United States or newborn HIV-1/2 contracted from infected mothers in Africa. These situations all would benefit from rapid evidence-based assessment of victims and patients.

RATIONALE

In catastrophic disaster situations where significant injuries and deaths occur, and infrastructure is compromised, health professionals and first responders are faced with challenges that require them to adapt usual standards of care. This deviation from traditional treatment protocols is referred to as “crisis standards of care.”

Point-of-care technologies have progressed substantially over the past three decades. 1,2 Limited POC equipment and basic test menus already are used by responders (Table 1). In this article, POC testing includes “near-patient” and “bedside” testing. In vitro diagnostic instruments require a sample for analysis, while monitoring devices, such as pulse oximeters and capnography, do not. Competency of operators of handheld POC devices has improved, but serious gaps in technological applications and practical implementation exist when not in regulated hospital and clinic environs.

Table 1.

Current POC Inventory of First Responder Teams

| Category | Types of Test(s) | Disaster Medical Assistance Teams | Local Emergency Medical Service |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Transfusion | ABO blood typing | Wet chemistry1 (test set 1) | None |

| Cardiac Monitoring | Electrocardiogram | ProPaq CS2 (test set 2) LifePak 10 or 123,4 (test set 3) |

LifePak 125 (test set 3) |

| Coagulation | Prothrombin Time | i-STAT analyzer PT/INR cartridge1,6 | None |

| Diagnostic Imaging | Ultrasound | Sonosite MicroMaxx (test set 4) | Not adopted uniformly7 |

| Glucose Monitoring | Capillary blood glucose | One Touch Ultra4 | Accu-Chek Advantage8

Precision Xtra9 Precision XceedPro10 |

| Hematology | Hemoglobin and Hematocrit | i-STAT analyzer with EC8+ cartridge1,6 (test set 5) Hemoglobinometer3 |

None |

| White blood cell count | Microscopy, hemocytometer1,3 | ||

| Non-invasive SpO2 Monitoring | Pulse oximetry | ProPaq CS2 (test set 2) Nonin Onyx 95501,3 |

LifePak 125 (test set 3) |

| Non-invasive pCO2 Monitoring | Capnography | LifePak 10 or 123,4 (test set 3) | LifePak 125 (test set 3) |

| Bacteriology | Gram’s stain | Gram positive and Gram negative bacterial differentiation with microscopy1 | None |

| Whole-Blood Analysis | Electrolytes and Metabolites | i-STAT analyzer with EC8+ cartridge1,6 (test set 5) | None |

| Blood gases | i-STAT analyzer with EC8+ cartridge1,6 (test set 5) | ||

| Vital Signs | Blood pressure | LifePak 10 or 123,4 (test set 3) ProPaq CS2 (test set 2) |

LifePak 125 (test set 3) |

| Heart rate | |||

| Respiratory rate | |||

| Temperature |

Test set: 1: ABO blood and Rh typing; 2: 3- or 5-lead ECG, respiration rate, invasive pressure monitoring (arterial, venous, intracranial), non-invasive blood pressure monitoring, temperature, pulse oximetry, and capnography; 3: 12-lead ECG, pulse oximetry, non-invasive blood pressure monitoring, capnography, temperature, respiratory rate, and biphasic defibrillation; 4: D velocity color Doppler, M-mode, and Duplex Imaging; and 5: pH, pO2, pCO2, total CO2, HCO3, O2 saturation, hemoglobin, hematocrit, ionized Ca++, Na+, K+, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glucose.

Abbreviations: ABO, ABO blood groups; CO2, carbon dioxide; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; ECG, electrocardiogram; INR, international normalized ratio; pCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PT, prothrombin time; Rh, Rhesus factor; and SpO2, oxygen saturation.

Piggott W. National Disaster Medical System presentation 2007. Available at: http://www.azdhs.gov/phs/edc/edrp/es/pdf/ndms_piggott.pdf, Accessed on August 30, 2011.

Texas Health Resources Field Surge Program presentation. Available at: www.ehcca.com/presentations/emsummit2/cannefax_pc2.pdf, Accessed on August 30, 2011.

Toledo, Ohio Disaster Medical Assistance Team support website. Available at: http://mediccom.org/public/tadmat/training/NDMS/Part_V.pdf, Accessed on August 30, 2011.

Missouri State Disaster Medical Assistance Team inventory website. Available at: http://mo1dmat.org/logistics/DMAT%20Basic%20Load%20(Rev%2021-Gen-II)%20(2-6-08).xls, Accessed on August 30, 2011.

Personal communication, Natalie Garcia, Paramedic, American Medical Response, Stockton, CA, May 1, 2011.

Email correspondence, Dr. David Lipin, Commander, Disaster Medical Assistance Team, CA-6, August 17, 2010.

Sonosite website. Available at: http://www.sonosite.com/healthcare-professions/ems/testimonials/, Accessed on August 30, 2011.

California Emergency Medical Services inventory document. Available at: http://intranasal.net/EMS%20training%20materials/Fresno%20CA%20EMS%20pediatric%20seizure%20protocol%20(dose%20too%20low).pdf, Accessed on August 30, 2011.

El Dorado County Emergency Medical Services alert notice for glucose meters, issued December 28, 2010. El Dorado County website. Available at: www.edcgov.us/Government/.../2010-07_Glucose_Test_Strip_Recall.aspx, Accessed on August 30, 2011.

St. Peter’s Hospital and Medical System website. Available at: http://www.stpetes.org/html/pointofcare/Procedures/WBG%20April%202009.html. Accessed on August 30, 2011.

Guidelines for urgent POC testing outside the hospital do not exist, applications in crises are inconsistent, and practice standards have yet to be established. These circumstances can present legal and ethical challenges. Thus, we describe how to improve crisis standards of care by using POC testing at the point of need, where speed is crucial, results high are impact, and rapid response can help optimize diagnostic-therapeutic (Dx-Rx) cycles by decreasing therapeutic turnaround time (TTAT). 3

Our approach starts from gap analysis with an integrated logic model, incorporates objective needs assessment survey results, uses reverse stress analysis to mitigate risk of failure, and then, concludes that POC approaches represents swift, viable, and useful options to sustain evidence-based screening, triage, diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment in crises, whether in developed nations or low-resource countries.

METHODS: ANTICIPATORY STRATEGIES

Logic Model-Critical Path-Feedback

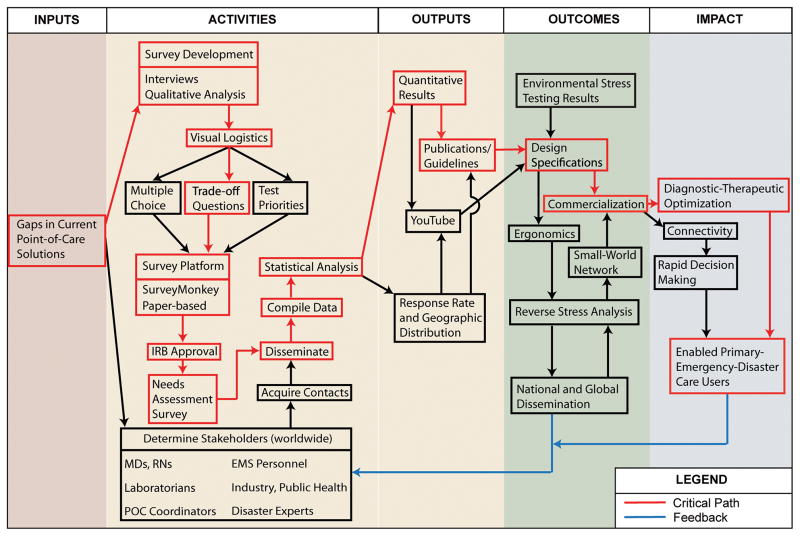

The UC Davis POC Technologies Center (http://www.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/pathology/poctcenter/) innovated a method called “LoC

PaF

PaF

” for Logic Model Critical Path Feedback that facilitates development of POC technologies for crisis care (Figure 1). This feedback system, which thus far primarily has guided the development of new POC pathogen detection, identifies the critical path (the slowest sequence of tasks or nodes) and links feedback loops within a logic model 4–8 that consists of inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes. A systematic approach to enhancing practice assures that POC research, design, and product commercialization will be iterated efficiently to arrive at optimal devices with test clusters that satisfy user objectives. Needs assessment surveys of stakeholders represent the engine that drives the process.

” for Logic Model Critical Path Feedback that facilitates development of POC technologies for crisis care (Figure 1). This feedback system, which thus far primarily has guided the development of new POC pathogen detection, identifies the critical path (the slowest sequence of tasks or nodes) and links feedback loops within a logic model 4–8 that consists of inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes. A systematic approach to enhancing practice assures that POC research, design, and product commercialization will be iterated efficiently to arrive at optimal devices with test clusters that satisfy user objectives. Needs assessment surveys of stakeholders represent the engine that drives the process.

Figure 1.

Needs Assessment Logic Map + Critical Path + Feedback

Needs Assessment Surveys

Needs assessment surveys 9–12 documented the presence of input gaps (left side, Figure 1) which, in the case of pathogen detection, were: a) lack of an appropriate preanalytical solution because exposed whole-blood samples often become contaminated, b) deficient transportable multiplex testing, and c) no definitive POC solution suitable for crises, despite the fact that survey respondents recognized the need for rapid diagnosis of infectious diseases, tracking of pandemics, and other urgencies. Then, working through the flowchart provides rational guidance for developing new POC test clusters that work well in emergencies and disasters. The POC Technologies Center developed a portfolio of devices tuned to the strategic roadmap generated through this logic model-critical path-feedback approach.

Reverse Stress Analysis

Reverse stress analysis identifies potentially disastrous events and then works backward to invent or innovate new technologies and efficient strategies that prepare for those events. Motivated by bank failures in 2009, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision issued a consultative document questioning the adequacy of bank stress testing procedures prior to the financial crisis and determined that the financial crisis was far worse than any of the stress testing protocols had predicted. 13 In this paper, “Crisis” means a dramatic upheaval or serious disease leading to an unstable, dangerous, or decisive outcome affecting an individual, group, community, or whole society, especially when changes occur abruptly with little or no warning.

Similarly, by means of reverse stress analysis, recent disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina, the Haiti earthquake, and the Eastern Japan Great Earthquake and tsunami, highlight gaps to be filled where POC testing can improve preparedness and responsiveness, since typically, it is the only form of diagnostic testing remaining when infrastructure is destroyed or collapses, 14,15 and in some cases, such as meters for self-monitoring of capillary blood glucose by children and adults with diabetes, must be rapidly deployed to shelters during recovery in order to avoid excess morbidity and mortality. 16

Robustness Evaluation

Table 1 lists common POC devices and tests carried by first responder teams in the United States. While these devices may be transported in protective containers and might be operated in controlled environments, test and quality control reagents most often are not protected from extremes of temperature, humidity, and other environmental factors encountered when in field settings. By means of static stress evaluation, Louie et al. 17 documented that test strips used with glucose meters and blood gas cartridges for the handheld i-STAT (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) are highly susceptible and fail when exposed to hot and cold temperature ranges typically encountered during emergencies and disasters.

RESULTS: EVIDENCE-BASED TACTICS

Environmental Stress

The Center has extended environmental stress evaluation to dynamic temperature and humidity profiles based on weather patterns in subtropical, tropical, hot, and cold sites of emergencies-disasters and discovered failure modes that could lead to unacceptable clinical misinterpretation of results. 18 To avoid risk of errors occurring with human subjects in actual field settings, POC resources should be stored within temperature limits set by manufactures, illustrated for HIV-1/2 assays in Table 2, so that the claimed sensitivity and specificity (see right-hand side) will be attained.

Table 2.

HIV Tests with Environmental Limits and Sensitivity

| Manufacturer | Product Trade Name | Sample Type | Storage Temp. (°C, °F) | Shelf Life (mo) | Analysis Time (min) | Sn (%) | Sp (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acon Labs1 www.aconlabs.com San Diego, CA |

HIV 1/2/O Tri-line Human Immunodeficiency Virus Rapid Test Device | serum, plasma | 12 | 5–15 | 99.9 | 99.8 | |

| AmeriTek2 www.ameritek.org Everett, WA |

HIV ½ Test | wb, serum, plasma | room temperature | 5–30 | na | na | |

| Bionor Laboratories3 www.bionor.no Skein, Norway |

BIONOR™ HIV-1&2 Kit | wb, serum, plasma, saliva | 12 | na | 100 | 98.8 | |

| BIONOR™ HIV-1&2 Confirmatory | wb, serum, plasma | 12 | 45 | na | na | ||

| Bio-Rad4 www.bio-rad.com Hertfordshire, UK |

Genie™ III HIV-1/HIV-2 Assay | wb, serum, plasma | 2–30, 36–86 | 15 | 100 | ≥99 | |

| Genie™ Fast HIV ½ Assay5 | wb, serum, plasma | 2–30, 36–86 | 10–30 | 100 | ≥99 | ||

| Calypte Biomedical6 www.calypte.com Portland, OR |

Aware™ HIV-1/2 BSP | wb | 2–30, 36–86 | 20 | 100 | 99.8 | |

| Aware™ HIV-1/2 OMT | oral fluid | 2–30, 36–86 | 20 | 99.5 | 99.8 | ||

| Aware™ HIV-1/2 U | urine | 2–30, 36–86 | 20 | 97.2 | 100 | ||

| Core Diagnostics7 www.corediag.com Birmingham, UK |

Core HIV 1&25 | wb, serum, plasma | 4–30, 39–86 | 30 | 100 | 97.5 | |

| Core Combo HIV-HBsAg-HCV Kit | wb, serum, plasma | 2–8, 36–46 | 15–30 | 100 | 99.8 | ||

| Fujirebio Diagnostics8 http://www.fujirebio.co.jp Tokyo, Japan |

SERODIA® - HIV-1/2 | serum, plasma | 2–10, 36–50 | na | na | na | |

| Hema Diagnostics9, 10 www.rapid123.com/ Miramar, Florida |

Rapid 1-2-3 HEMA Express | wb, serum, plasma | 15–30, 59–86 | 30–15 | 99.6 | 100 | |

| Rapid 1-2-3 HEMA HIV Dipstick | wb, serum, plasma | 15–30, 59–86 | 30–15 | 99.5 | 100 | ||

| Inverness Medical11, 12 www.invernessmedicalpd.com Princeton, NJ |

Clearview® COMPLETE HIV 1/2 | wb13, serum, plasma | 8–30, 46–86 | 24 | 15 | 99.7 | 99.9 |

| Clearview® COMPLETE HIV 1/2 STAT-PAK | wb2, serum, plasma | 8–30, 46–86 | 24 | 15 | 99.7 | 99.9 | |

| Determine® HIV-1/2 | wb, serum, plasma | 2–30, 36–86 | 14 | 15 | 100 | 99.8 | |

| Determine® HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo | wb, serum, plasma | 2–30, 36–86 | 10 | 20 | 100 | 99.2–99.6 | |

| OraSure Technologies10, 14 www.orasure.com Bethlehem, PA |

OraQuick ADVANCE® HIV-1/2 Rapid HIV-1/25,15 | wb13, plasma, oral fluid13 | 2–27, 35–80 | 6 | 20 | 100 | 98.9 |

| Orgenics10, 16 www.orgenics.com Yavne, Israel |

DoubleCheck™ II HIV 1&25 | serum, plasma | 2–8, 36–46 | 15 | 11 | 100 | 99.3 |

| DoubleCheckGold™ HIV 1&2 Whole Blood | wb, serum, plasma | 2–30, 36–86 | 15 | 15 | 100 | 99 | |

| ImmunoComb® II HIV 1&2 BiSpot5 | serum, plasma | 2–8, 36–46 | 15 | 36 | 100 | 99.4 | |

| ImmunoComb® II HIV 1&2 CombFirm | serum, plasma | 2–8, 36–46 | na | 99.7 | 100 | ||

| ImmunoComb® II HIV 1&2 TriSpot Ag-Ab | serum, plasma | 2–8, 36–46 | na | 100 | 99.3 | ||

| PointCare™ HIV Whole Blood/Serum/Plasma | wb, serum, plasma | 2–30, 36–86 | 15 | 100 | 99 | ||

| RapidSignal™ HIV 1&2 Serum/Plasma Cassette | serum, plasma | 2–30, 36–86 | 15 | 99.9 | 99.6 | ||

| Princeton Biomeditech17 www.pbmc.com Princeton, NJ |

BioSign HIV-1/HIV-2 WB | na | room temperature | na | na | na | |

| Premier Medical18 Corporation Limited www.premiermedcorp.com Daman, India |

First Response® HIV 1-2-0 Test Strip (Serum/Plasma/Whole Blood)5 | wb, serum, plasma | 4–30, 39–86 | 10 | 100 | 99.5 | |

| First Response® HIV Card Test 1–2.O5 | wb, serum, plasma | 4–30, 39–86 | 24 | ≥15 | 100 | 99.9 | |

| Standard Diagnostics19 www.standardia.com Kyonggi-do, Korea |

SD Bioline HIV 1/2 3.0 | wb, serum, plasma | 15–30, 34–86 | 24 | 5–20 | 100 | 99.8 |

| Trinity Biotech12, 20 www.unigoldhiv.com Co Wicklow, Ireland |

Uni-Gold™ HIV | wb, serum, plasma | 2–27, 36–81 | 15 | 10 | 100 | 99.7–100 |

| Uni-Gold™ Recombigen® HIV15 | wb13, serum, plasma | 2–27, 36–81 | 12 | 10 | 100 | 99.7 |

Abbreviations: na, not available; Sn, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; and wb, whole blood.

Infectious Diseases page. Acon Laboratories Web site. Available at: http://www.aconlabs.com/infect.html. Accessed July 07, 2011.

Infectious Disease Tests page. Brochure. Ameritek Web site. Available at: http://www.ameritek.org/images/Infectious-brochure.jpg. Accessed July 07, 2011.

BIONOR HIV-1&2 Kit, BIONOR HIV-1&2 Confirmatory Test. Brochures. BIONOR Web site. Available at: http://www.bionor.no/hiv.htm. Accessed July 11, 2011.

Genie™ III HIV-1/HIV-2 Assay, Genie™ Fast HIV ½ Assay. Bio-Rad Web site. Available at: http://www.bio-rad.com/. Accessed July 11, 2011.

CE marked.

Aware™ HIV-1/2 BSP, Aware™ HIV-1/2 OMT, Aware™ HIV-1/2 U. Product inserts. Calypte Biomedical Corporation Web site. Available at: http://www.calypte.com/index.asp. Accessed July 11, 2011.

Rapid Test page. Core HIV 1&2, Core Combo HIV-HBsAg-HCV Kit. Product inserts. Core Diagnostics Web Site. Available at: http://www.corediag.com/rapidtest.html. Accessed July 07, 2011.

SERODIA® Series page. Fujirebio Diagnostics Web site. Available at: http://www.fujirebio.co.jp/english/product/serodia.html#02. Accessed July 07, 2011.

Products/HIV page. Hema Diagnostics Systems Web site. Available at: http://www.rapid123.com/products_hiv.html. Accessed July 07, 2011.

Rational Pharmaceutical Management Plus. 2009. HIV Test Kits Listed in the USAID Source and Origin Wiaver: Procurement Information Document. Fifth edition. Edited by A. Johnson. Submitted to the U.S. Agency for International Development by the Rational Pharmaceutical Management Plus Program. Arlington, VA: Management Sciences for Health.

Clearview® COMPLETE HIV ½, Clearview® COMPLETE HIV ½ STAT-PAK. Inverness Medical Web site. Available at: http://www.invernessmedicalpd.com/default.aspx. Accessed July 11, 2011.

Determine® HIV ½, HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo. Product specifications pages. Determine Web site. Available at: http://www.determinetest.com/default.aspx. Accessed July 11, 2011.

CLIA waived.

OraQuick ADVANCE® Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test. Custom Letter and Package Insert-English. OraSure Technologies Web site. Available at: http://www.orasure.com/products-infectious/products-infectious-oraquick.asp. Accessed July 11, 2011.

FDA approved.

DoubleCheck™ II HIV 1&2, DoubleCheckGold™ HIV 1&2 Whole Blood, ImmunoComb® II HIV 1&2 BiSpot, ImmunoComb® II HIV 1&2 CombFirm, ImmunoComb® HIV 1&2 TriSpot Ag-Ab, PointCare™ HIV, RapidSignal™ HIV 1&2 Serum/Plasma Cassette, RapidSignal™ HIV 1&2 Whole Blood/Serum/Plasma Cassette. Product inserts. Orgenics Web site. Available at: http://www.orgenics.com. Accessed July 11, 2011.

Products: BioSign® Infectious Disease Tests page. Princeton BioMeditech Corporation Web site. Available at: http://www.pbmc.com/products/infectious.shtm. Accessed July 08, 2011.

First Response® HIV 1-2-0 Human Immmunodeficiency Virus Rapid Test Strip (Serum/Plasma/Whole Blood), First Response® HIV 1–2.O Card Test Rapid HIV Card Test Whole Blood/Serum/Plasma. Package inserts. Premier Medical Corporation Web site. Available at: http://www.premiermedcorp.com/infectiousdiseases.html. Accessed July 11, 2011.

SD Bioline HIV ½ 3.0. Brochure. Standard Diagnostics Incorporated Web site. Available at: http://www.standardia.com/html_e/. Accessed July 11, 2011.

Uni-Gold™ HIV, Uni-Gold™ Recombigen® HIV pages. Trinity Biotech Web site. Available at: http://www.trinitybiotech.com/PointOfCare/Pages/PointOfCare.aspx. Accessed July 11, 2011.

Hence, cartridges, cassettes, test strips, and test kits must be protected from environmental extremes. Strategic tactics include improving intrinsic robustness of assays; sealing test strips, cartridges, and cassettes in protective covers; transporting supplies insulated from temperature and humidity extremes; and appropriately staging POC testing. In view of the current partially complete knowledge of environmental vulnerabilities of POC reagents for most important tests, responder teams may not be adequately prepared to assure the quality of test results. Until manufactures produce more durable products, POC testing operators must minimize chances of unexpected or unrecognized failures in patient profiling.

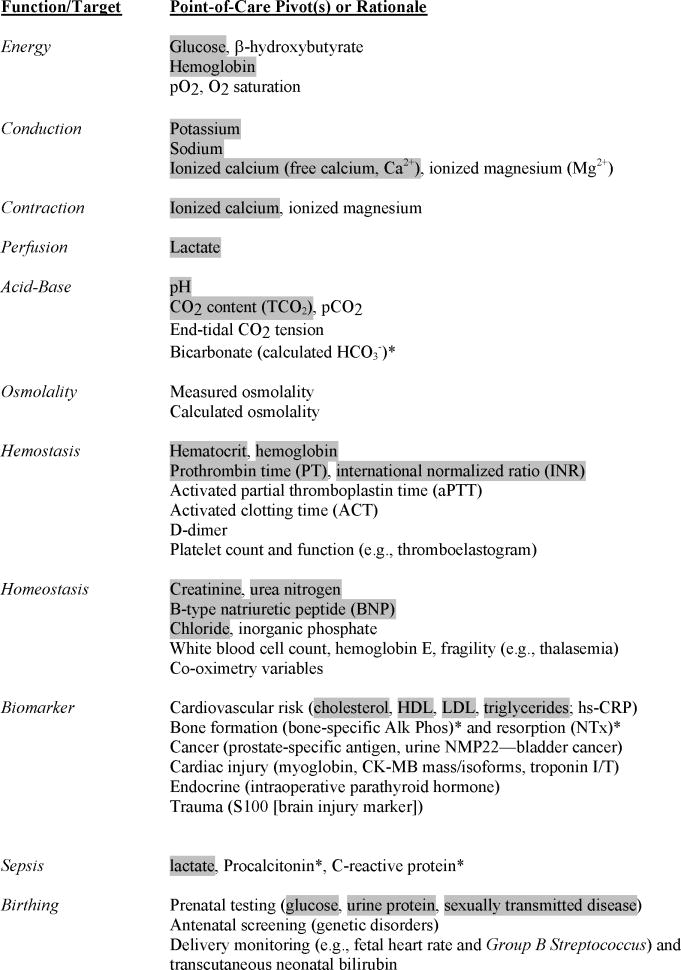

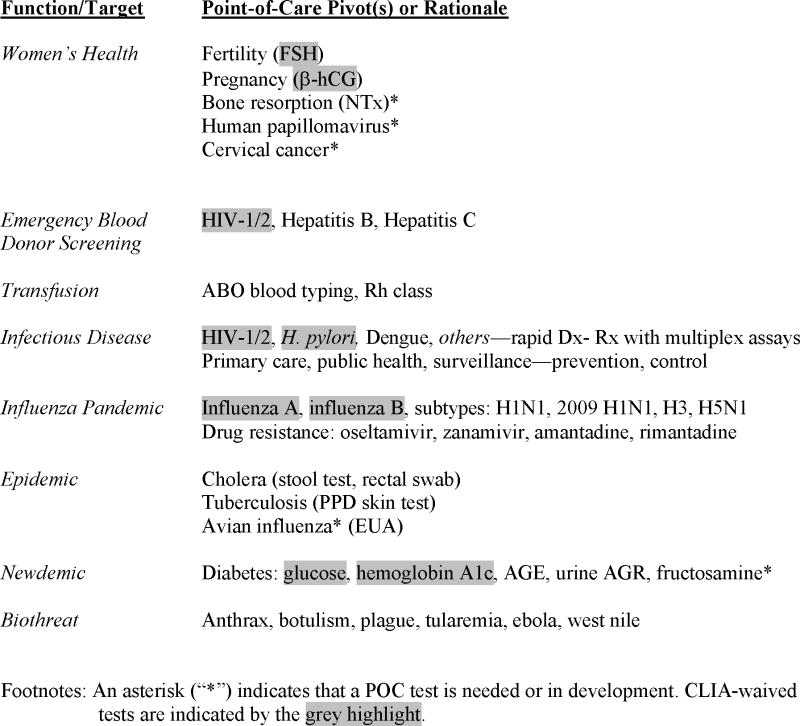

Crisis Care Profile

Table 3 presents problem-focused POC in vitro tests available to assess pathophysiological status. Ultimately, test results help predict survival. For instance, POC lactate is predictive of mortality in severe sepsis among high prevalence HIV-1 patients in low-resource settings where laboratories cannot supply full data supporting risk scoring systems. 19,20 Further, noting the devastating effects of historical disasters on clinical laboratories, where for the most part they have become inoperable, 14,15 positioning POC testing in or near customary health care delivery sites allows some control of the local environment, provides fast therapeutic turnaround time, achieves efficiency through daily use, and avoids the need for excessive stockpiling. Note that Table 3 identifies so-called “CLIA-waived” tests that do not have strict operator requirements for performing tests in the US.

Table 3.

Crisis Care Profile

|

|

Laboratory facilities were destroyed in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and thus were lacking during the first weeks of intervention; the use from the beginning of the crisis of “a (donated) point-of-care device (i-STAT) was very efficient for the detection of aberrant kidney function and electrolyte parameters.” 21 Vanholder et al. stated, 21 “This was a major advantage since it permitted patient stratification into conservative management or dialysis in view of the scarcity of dialysis possibilities and of intravenous fluids for rehydration…and monitoring or critically ill patients, e.g. diabetics with ketoacidosis.” Thus, POC devices should be more widely available in small-world networks in order to be prepared immediately to use them during crises, such as during extrications from earthquake trauma with crush syndrome when hematocrit, base deficit, and potassium are needed for acute management 22 —hence, the importance of the crisis care profile at the point of need.

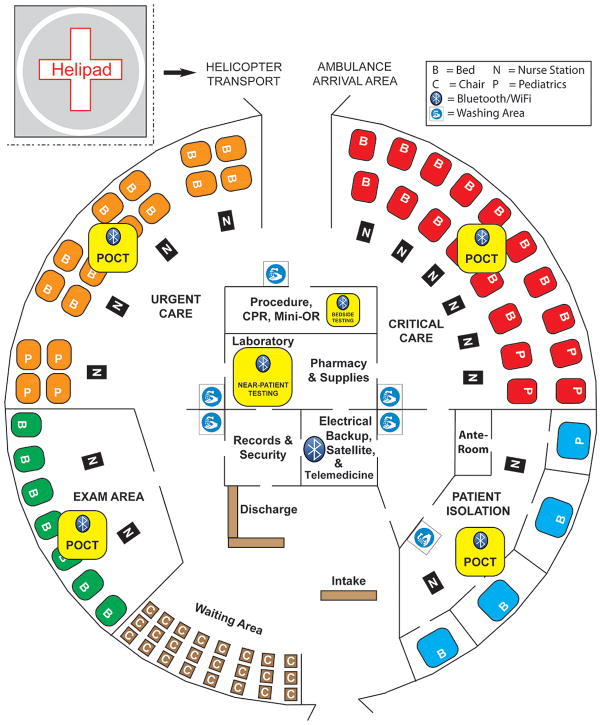

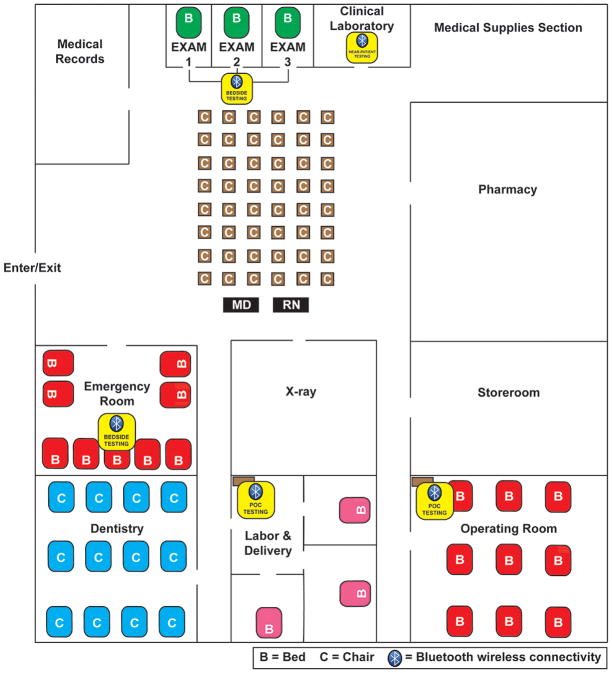

Small-World Networks

Figure 2 shows a conceptual design for an alternate care facility with POC resources, which can be reconfigured to fit the physical dimensions of actual structures 23–26 that become available locally at or near disasters. Figure 3 illustrates a comparable set-up in the urgent care entrance area of a typical community hospital found in low-resource countries. This type of facility is common at nodes of small-world networks (SWNs) in rural regional health care systems outside the United States.

Figure 2.

Alternate Care Facility with Fast Therapeutic Turnaround Time

Figure 3.

Low-Resource Community Hospital with Near-patient and POC Testing

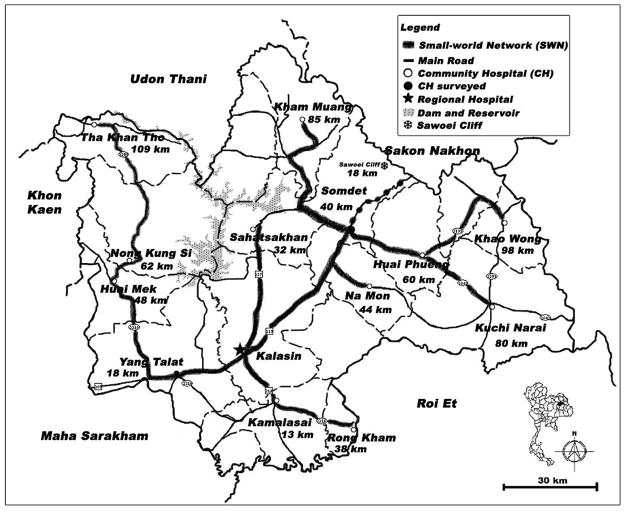

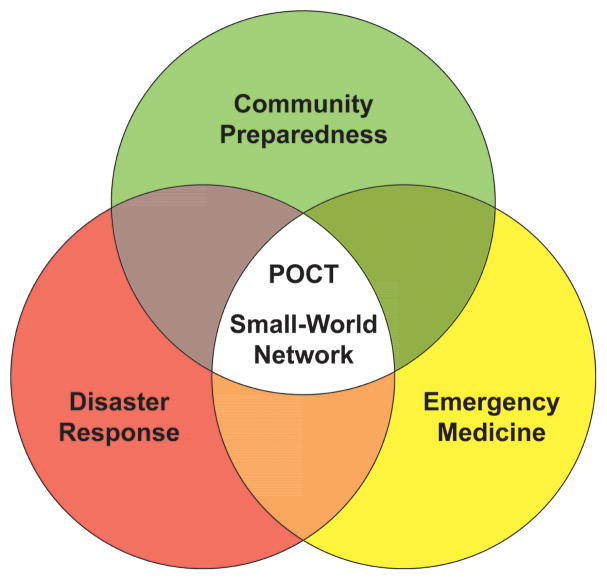

Figure 4 illustrates an actual SWN in Kalasin Province, an economically impoverished area in northeastern Thailand called Isaan, where such a community hospital can be found. The advantage of the SWN-POC approach is that local community and regional healthcare leaders can blend preparedness synergistically with routine daily use of POC testing to fulfill both disaster needs and emergency medicine goals within the SWN (Figure 5). 27

Figure 4. Small-World Network in Kalasin Province, Thailand.

This province is located in rural northern Isaan, a low-resource region of Thailand isolated geographically by rugged terrain. Ambulance transport time to regional hospitals is significant despite modest distances between the small-world network hubs, where, ideally, POC testing should be situated to simultaneously and cost-effectively accelerate daily urgent and emergency care, as well as facilitate preparedness for crises.

Figure 5.

Tactical Integration and Optimization Improve the Standard of Care

Mobility, Flexibility, and Synergism

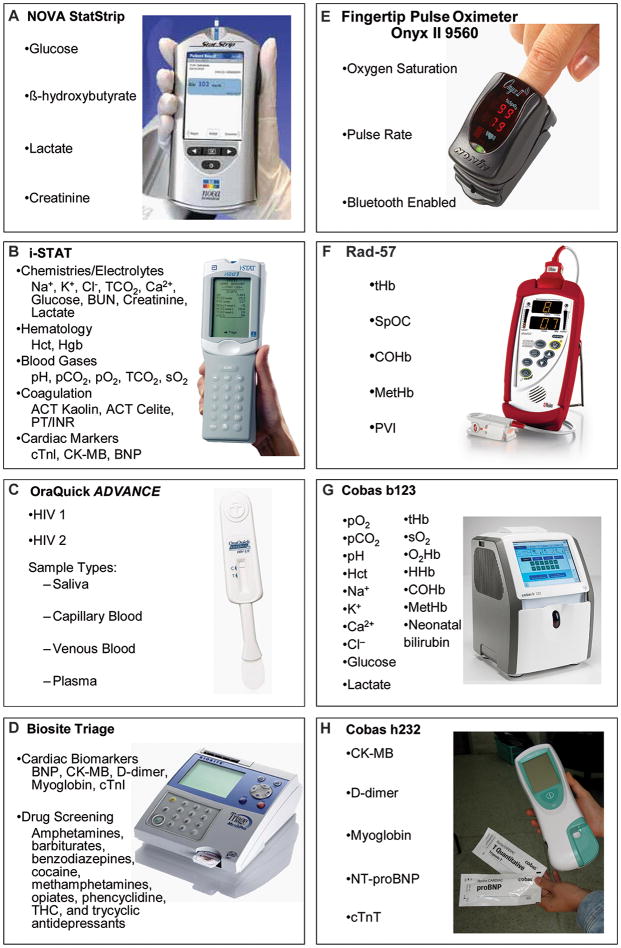

Mobile POC testing can be used flexibly in numerous settings, including transport, such as ambulances, helicopters, and large jets used primarily in developed countries, and vans, trucks, and emergency medical systems (EMS) vehicles used in low-resource settings. Figure 6 shows new types of POC devices and test clusters. These instruments can expand medical intelligence significantly during disaster, emergency, and public health responses.

Figure 6. POC Technologies of High Value in Crises.

This figure presents a collage of POC devices that cover many testing and monitoring needs of first responders. The device in frame A is CLIA-waived for glucose, frame B for hematology and all chemistries/electrolytes except lactate, frame C for saliva and capillary and venous blood, and frame D for B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP). Frames E and F show monitoring devices useful for O2 saturating and hemoglobin trend following. Devices in frames G and H, which are not available in the U.S. or Western Europe, provide valuable evidence-based test results for blood gases, electrolytes, co-oximetry, cardiac biomarkers, and coagulation status. Manufacturers and websites: A) StatStrip, www.novabiomedical.com; B) i-STAT, www.abbottpointofcare.com; C) OraQuick ADVANCE, www.orasure.com; D) Triage, www.biosite.com; E) Onyx II, www.nonin.com; F) Rad-57, www.masimo.com; G) Cobas b123, www.roche.com; and H) Cobas h232, www.roche.com.

If a) protective temperature-humidity storage containers (which the Center is developing) are used, b) instruments are operated within environmental tolerances specified by manufactures, and/or c) weather conditions are benign and present no challenges, then POC tests can be performed directly in the field with assurance of accurate test results, providing operators are trained, competent, experienced, and coordinated.

Pathogen Tactical Landscape

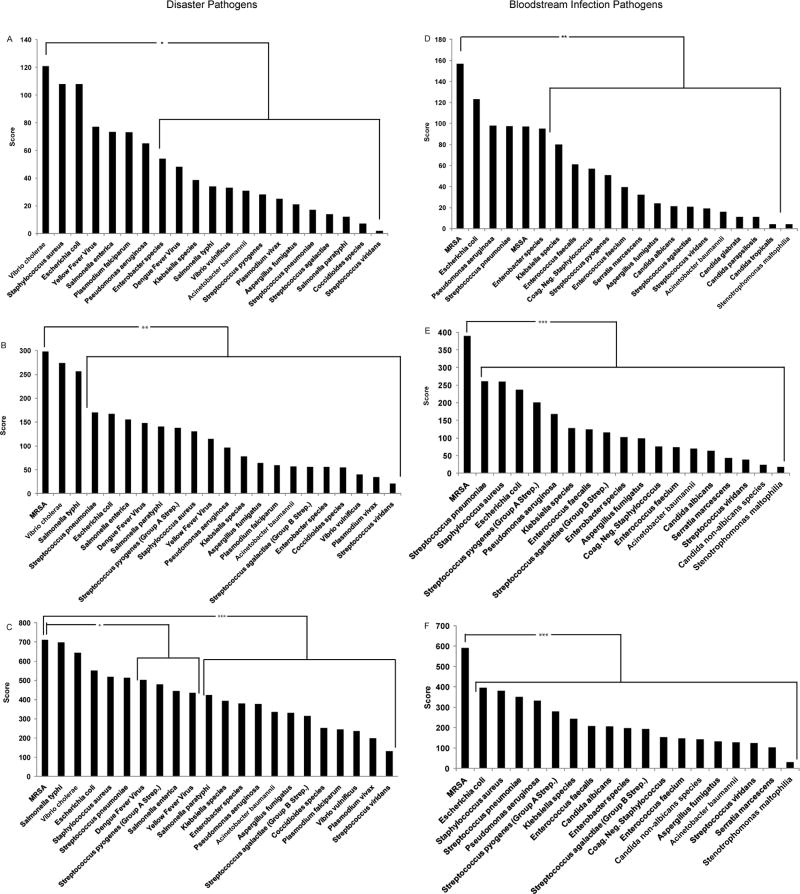

While portable nucleic acid detection instruments are not yet commercially available for multiplex pathogen detection (but under development in the Center), tactics to fulfill needs have been established by analyzing surveys of disaster experts, POC users, and laboratory professionals (Figure 7), 9–12 who identified risk areas (e.g., MRSA, cholera, and Dengue fever) where current diagnostic tools are deemed inadequate for crises in light of the fact that conventional hospital infrastructure could be compromised and microbiology laboratories inoperable or inaccessible. Besides detecting highly ranked pathogens, helping conserve drugs in short supply, and determining epidemiological patterns of drug resistance, survey respondents stated that POC devices should be fast (<1 hour analysis time), highly specific (>90%), handheld, and capable of retaining biohazards. 9–12

Figure 7. Pathogen Detection Needs Assessment: Comparison of Three Surveys.

Frames A, B, and C display results for pathogen priorities in disaster settings from three surveys: A) editorial board members of two disaster journals (n=19), 10 B) readership of Point of Care (POC) (n= 47), 11 and C) members of the American Association of Clinical Chemistry (AACC) (n=100), 12 respectively. Frames D, E, and F display results of high priority pathogens for bloodstream infection testing from the same groups: D) editorial board members (n=21), E) POC (n=49), and F) AACC (n=83). Pathogens located within brackets were ranked lower statistically in pair-wise comparison with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Survey respondents were asked to rank pathogens from 1–10, 1 being the most important, for both disaster and bloodstream infectious disease testing. The needs assessment surveys improved over time. The original survey provided to the disaster editorial board members did not differentiate between MRSA and Staphylococcus aureus for disasters; therefore, frame A does not have MRSA represented, and the selection of Staphylococcus aureus would encompass MRSA preference.

Analysis of Variance and Tukey Test (SPSS 19, Chicago, IL) were used for comparisons. Asterisks represent statistical significance: * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, and *** P<0.001, while n represents the number of respondents for each specific question, which differs depending on the number of questions respondents answered.

DISCUSSION

Crisis Standards of Care

The fundamental concept of standard of care is based on the legal case, Vaughn v. Menlove (1837), wherein the judge instructed the jury to reason whether the defendant “proceed[ed] with such reasonable caution as a prudent man would have exercised under such circumstances.” This concept is modified in “crisis standards of care,” which Institute of Medicine (IOM) committees define as “a substantial change in usual healthcare operations and the level of care it is possible to deliver, which is made necessary by a pervasive (e.g., pandemic influenza) or catastrophic (e.g., earthquake, hurricane) disaster.” 28,29 For in vitro diagnostics, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) uses the “Emergency Use Authorization” 30 to accelerate approval and availability of essential tests, such as the 2009 H1N1 Influenza assay (not POC) in time of urgent need.

The “Point” of Crisis Point of Care

Various authors argue the legal 31,32 and practical 33 implications of modifications in the standard of care as it was historically defined, but most probably would agree that the practice of medicine in emergency, disaster, and public health crises would benefit from appropriate rapid on-site testing that improves evidence-based decision-making under stressful circumstances, whatever and wherever they might be.

Modern crises, which we term “newdemics,” 34 appear uniquely and suddenly to affect broad populations and geographic areas. Mobile POC testing can serve well as a common denominator used to gather medical evidence. Ideally, it should not be derived exclusively or even mostly from rescue team caches and external good will, but instead, with planning, be part and parcel of daily medical care. Then, evidence obtained can efficiently and quickly guide any deviations in the standard of care that are warranted by unique circumstances, such as the rational selection of alternate antibiotics based on pathogen identity when first line drugs become exhausted in sites isolated by weather, earthquakes, or quarantines.

Key Elements

The IOM 29 codified a framework for crisis standards of care that encompasses key elements: a) fairness—standards that are, to the highest degree possible, recognized as fair by all those affected by them, b) equitable processes—transparency (in design and decision making), consistency, proportionality (in relation to the scale of the disaster and resources available), and accountability, c) community and provider engagement, education, and communication, and d) the Rule of Law.

Fundamental to this IOM vision is, “Evidence-based clinical processes and operations,” exactly the principle used in this article to guide strategic planning regarding tactics that determine how to implement POC approaches. Hence, future innovations in the underpinnings of crisis standards of care should arise proactively by soliciting input, feedback, and guidance from stakeholders, including communities that represent vulnerable and at-risk populations, in order to arrive at a consensus.

Vision

We envision implementing POC testing within “small-world networks” (SWNs), 27,34 which are comprised of the regional health care delivery systems, nodal placement sites for POC testing, and established EMS transport modalities and routes. Small-world networks facilitate daily use of POC testing, so that preparedness is community-based and in place daily, ordinary urgent care and emergency services are served, health professional are practiced at delivering POC test results at the bedside, and the total scheme is medically sound (Table 4). By synthesizing documented needs, addressing gaps not yet filled, and reducing risks throughout the SWN with use of POC testing, we arrive at the following recommended strategies intended to improve crisis standards of care and the effectiveness of future responses.

Table 4.

Small-World Network Practice Principles Using POC Testing

| SWN Attribute | POC Innovation | Overriding Principle(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Remote node at periphery of SWN | Cardiac biomarkers [e.g., Cobas h232 handheld cardiac troponin T & BNP testing] | In remote emergency rooms where physicians do not want to hold acute myocardial infarction patients overnight because of the risk of death, fast diagnosis with POC testing triggers triage & rapid transport |

| Physician primary care at poorly served hubs & border posts | Multiplex testing | Physicians living on site in low-resource settings improve workflow when rapid test results are available directly at Primary Care Units (PCUs) |

| PCUs & their local village hubs | Hemoglobin A1C (& capillary glucose) in the village where people live | Knowledge of diabetes control success at the village level aids local community hospital care team to adjust therapy rapidly for both acute & chronic patients |

| Demographic care units determined by village population clustering | Non-invasive hemoglobin monitoring for critically ill hospitalized patients | Endemic Dengue fever outbreaks with hemorrhagic fever require frequent decisions regarding need for transfusion at critical hemoglobin depletion levels typically guided by conventional spun Hct |

| Ambulance transport routes | Oxygen saturation (pulse oximetry) | Continuous monitoring of the effectiveness of ventilation during prolonged transport within or outside SWN improves outcomes |

| Nodes subject to isolation during earthquakes, tsunamis, or floods | Emerging POC pathogen detection for bacteria and viruses | Direct nucleic acid detection provides an efficient alternative to traditional culture methods that typically are not available in small community hospitals & in times of crisis, may not be accessible at all |

| Added value, cost-effectiveness, & community preparedness | Preparedness & “just-in-time” education & training resources | Familiarity performing POC testing on a daily basis lends to expertise in times of crises, such as local pandemics, regional disasters, or newdemics, & supports community-based preparedness |

Strategic Initiatives

First, test clusters available must be modular, scalable, flexible, deployable, focused (see Table 3), and as noted above, enhanced and augmented to enable POC multiplex pathogen detection and drug resistance markers to counter pandemics, disaster-disabled or isolated microbiology laboratories, and other public health risks. Pathogen detection devices should have form factors recommended by needs assessment surveys. 9–12 For example, biohazards must be contained and test cassettes should be disposable without risk of instrument contamination.

Second, as technological progress moves more tests to the point of need, education must follow suit, in fact, anticipate the change. Training, quick reference cards, just-in-time web resources (e.g., http://www.youtube.com/POCTCTR#p/u/1/9ELSR7z0U4w), standardized education of POC coordinators, and understanding of quality assurance/quality control presages this basic paradigm shift to the crisis hybrid laboratory 35 and team competency prior to deployment. For example, in Haiti, HIV-1/2 testing of victims was inadequate so volunteers could not properly assess exposure resulting from accidental needle sticks to themselves, and even then, selection of kits would have to be based on anticipated environmental conditions through weather profiling 18 and ease of use by responders (see Table 2).

Third, storage, transport, and operating conditions must meet manufacturer specifications for environmental limits until such time as more robust products and storage solutions are produced. 36,37 These specifications can be found on the package inserts of medical devices or test reagents. Availability of temperature and humidity profiles that model conditions in emergencies and disasters 18 facilitates not only conceptual instrument design (e.g., handheld battery-powered platforms that perform measurements at body temperature in cold environments), but also the future evaluation and production of appropriate equipment and durable reagents for “hardened” POC devices.

Fourth, incremental staging of POC in SWNs, described above, will help assure greater flexibility in screening, triage, treatment, and follow-up monitoring, when POC testing is located in alternate care and community facilities in the U.S. or low-resource countries. Fifth, POC resources for these types of settings can be enhanced with connectivity and remote telecommunications, 38 as portrayed in Figures 2 and 3, to improve throughput, tracking, and other operational factors. Point-of-care connectivity in “field area networks” (FANs) should be developed in conformance with established standards published by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. Hospitals in the U.S. now have POC coordinators, either medical technologists or nurses, who manage POC and its infrastructure. Hence, sixth, responder teams would benefit from their participation or appointment of a POC coordinator among the team.

Value Propositions

The value of improving crisis standards of care using POC testing resides in part in the everyday improvement of urgent and emergency services within the SWN, that is, practical community-based preparedness (see Figure 7) for acute and chronic medical cases without heavy capital investment in resources that are used infrequently, or perhaps never, nor in reagents that could expire on the shelf before being used. 39 In view of potential high impact, POC testing for crises should be investigated further and its merits determined with regional demonstration projects in different global sites and configurations, including temporary and mobile structures, such as the ACF and POC-augmented community or mobile hospital.

Real-world experiments already have shown the efficacy of this approach for the care of acute coronary syndrome patients with myocardial infarction, where the value of rapid diagnosis and treatment in the low-resource SWN is deemed higher than the costs of POC implementation, and POC supplies are obtained as needed. Value also derives from non-invasive POC technologies, such as continuous oxygen saturation monitoring with fingertip pulse oximeters, which are inexpensive devices (now ~$30) that can accompany patients in ambulances for stabilization during transfer to regional referral centers and can be used anywhere in the emergency room and community hospital 40 and capnography for monitoring exhaled carbon dioxide to assist ventilator management. 41

CONCLUSIONS

Careful implementation of POC testing will facilitate evidence-based screening, triage, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up monitoring of victims and patients, while advancing performance in emergency and disaster medicine. Ultimately, integration of POC testing in small-world networks (SWNs) should improve crisis standards of care and outcomes—the SWN is the map, POC testing is the compass, and both are necessary to navigate future challenges with evidence-based medicine.

The more POC testing is used daily by responders during non-disaster conditions in their home facilities, the better their competency and less they need to be trained just before being called to assist in crises. Currently, enhancement of awareness, availability of educational resources, and practical training courses that assure operator competency will improve responder team preparedness prior to the advent of formal guidelines that we expect will codify at least some of the strategies and tactics offered in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported primarily by the Point-of-Care Testing Center for Teaching and Research (POCT•CTR) and in part by a National Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) Point-of-Care Technologies Center grant (Dr. Kost, PI, NIH U54 EB007959). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIBIB or the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank other Center team members who contributed, including Stephanie Sumner, Dr. Wanvisa Boonlert, staff researchers, and undergraduate students at the University of California, Davis. Figures and tables were provided with permission and courtesy of Knowledge Optimization®, Davis, CA.

References

- 1.Kost GJ, editor. Principles and Practice of Point-of-Care Testing. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price CP, St John A, Kricka LL, editors. Point-of-Care Testing: Needs, Opportunity, and Innovation. Washington DC: AACC press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kost GJ. The hybrid laboratory, therapeutic turnaround time, critical limits, ® performance maps, and Knowledge Optimization. In: Kost GJ, editor. Principles and Practice of Point-of-Care Testing. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Julian DA. The Utilization of the logic model as a system level planning and evaluation device. Evaluation Program Planning. 1997;20:251–257. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torghele K, Buyum A, Dubruiel N, et al. Logic model use in developing a survey instrument for program evaluation: emergency preparedness summits for schools of nursing in Georgia. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24(5):472–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacPhee M. Developing a practice-academic partnership logic model. Nurs Outlook. 2009;57:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson DE, Broemeling A-M, Wong ST. A results-based logic model for primary healthcare: A conceptual foundation for population-based information systems. Healthcare Policy. 2009;5:33–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sitaker M, Jernigan J, Ladd S, et al. Adapting logic models over time: The Washington State Heart Disease Stroke Prevention Program experience. [Accessed August 29, 2011];Prev Chronic Dis. 2008 5(2) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/apr/07_0249.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kost GJ, Hale KN, Brock TK, et al. Point-of-care testing for disasters: Needs assessment, strategic planning, and future design. Clin Lab Med. 2009;29:583–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brock TK, Mecozzi DM, Sumner SL, et al. Evidence-based point-of-care test cluster and device design for disaster preparedness. Am J Disaster Med. 2010;5:285–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mecozzi DM, Brock TK, Tran NK, et al. Evidence-based point-of-care device design for emergency and disaster care. Point of Care. 2010;9:65–69. doi: 10.1097/POC.0b013e3181d9d47a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kost GJ, Mecozzi DM, Brock TK. Assessing needs for point-of-care testing in emergencies and disasters. 2011. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Principles for sound stress testing practices and supervision. Basel, Switzerland: Bank for International Settlements; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawai T, Tatsumi N. POCT for earthquakes and disaster preparedness. In: Kost GJ, editor. Principles and Practice of Point-of-Care Testing. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. pp. 407–408. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kost GJ, Tran NK, Tuntideelert M, et al. Katrina, the tsunami, and point-of-care testing: Optimizing rapid response diagnosis in disasters. Amer J Clin Pathol. 2006;126:513–520. doi: 10.1309/NWU5E6T0L4PFCBD9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ceflau WT, Smith SR, Blonde L, et al. The Hurricane Katrina aftermath and its impact on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:158–160. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louie RF, Sumner SL, Belcher S, et al. Thermal stress and point-of-care testing performance: suitability of glucose test strips and blood gas cartridges for disaster response. Disas Med Publ Health Prepared. 2009;3:13–17. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181979a06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson WJ, Louie RF, Yu JN, et al. Dynamic temperature and humidity profiles for assessing the suitability of point-of-care testing during emergencies and disasters. Proceedings of the American Association for Clinical Chemistry Annual National Meeting; Atlanta, Georgia. July 24–28, 2011; p. A155. [Best Abstract Award] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore CC, Jacob ST, Pinkerton R, et al. Point-of-care lactate testing predicts mortality of sepsis in a predominantly HIV type 1-infected patient population in Uganda. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:215–222. doi: 10.1086/524665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riviello ED, Letchford S, Achieng L, et al. Critical care in resource-poor settings: Lessons learned and future directions. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:860–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206d6d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanholder R, Borniche D, Claus S, et al. When the Earth trembles in the Americas: the experience of Haiti and Chili 2010. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;117:184–197. doi: 10.1159/000320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubota M, Ishida H, Kojima Y, et al. Impact of mobile clinical analysers on disaster medicine: A lesson from crush syndrome in the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji earthquake. Biomed Instr Tech. 2003;37:259–262. doi: 10.2345/0899-8205(2003)37[259:IOMCAO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam C, Waldhorn R, Toner E, et al. The prospect of using alternative medical care facilities in an influenza pandemic. Biosecurity Bioterrorism. 2006;4:84–905. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2006.4.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cantrill S, Pons PT, Bonnett CJ, et al., editors. Disaster alternate care facilities: Selection and operation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altegovt BM, Stroud C, Nadig L, et al., editors. Workshop Summary. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2010. Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events. Medical Surge Capacity. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glassman ES, Parrillo SJ. Use of alternate healthcare facilities as alternate transport destinations during a mass-casualty incident. Prehospital Disaster Medicine. 2010;25:178–82. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00007949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kost GJ, Kost L, Suwanyangyuen A, et al. Emergency cardiac biomarkers and point-of-care testing: Optimizing acute coronary syndrome care using small-world networks in rural settings. Point of Care. 2010;9:53–64. doi: 10.1097/POC.0b013e3181d9d45c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altevogt BM, Stroud C, Hanson SL, et al., editors. Guidance for establishing crisis standards of care for use in disaster situations: A letter report. Washington D.C: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stroud C, Altevogt BM, Nadig L, et al., editors. Crisis standards of care: Summary of a workshop series. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed August 29, 2011];Emergency Use Authorization of Medical Products. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm125127.htm.

- 31.Pope TM, Palazzo MF. Legal briefing: Crisis standards of care and legal protections during disasters and emergencies. J Clin Ethics. 2010;21:358–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodge JG, Courtney B. Assessing the legal standard of care in public health emergencies. JAMA. 2010;303:361–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Annas GJ. Standard of—in sickness and in health and in emergencies. N England J Med. 2010;362:2126–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhle1002260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kost GJ. Newdemics, public health, small-world networks, and point-of-care testing. Point of Care. 2006;5:138–144. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kost GJ. The hybrid laboratory: Shifting the focus to the point of care. Med Lab Obs. 1992;24(9 Supplement):17–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grissom TE, Farmer JC. The provision of sophisticated critical care beyond the hospital: Lessons from physiology and military experiences that apply to civil disaster medical response. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:S13–S21. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000151063.85112.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Department of Homeland Security. A Companion to the National Preparedness Guidelines. Washington D.C: Homeland Security; 2007. Target Capabilities List. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu JN, Brock TK, Mecozzi DM, et al. Future connectivity for disaster and emergency point of care. Point of Care. 2010;9:185–192. doi: 10.1097/POC.0b013e3181fc95ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodwig FR. Emergency preparedness essential: a pathologist’s stance on POCT. Med Lab Obs. 2006;38:18, 20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Point-of-Care Technologies Center. Disaster Point of Care. [Accessed August 29, 2011];Noninvasive Monitoring. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/POCTCTR#p/u/1/9ELSR7z0U4w.

- 41.Venticinque SG, Grathwohl KW. Critical care in the austere environment: Providing exceptional care in unusual places. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:S284–92. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817da8ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]