Abstract

Background and Objectives

Although hyperglycemia is thought to increase the generation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), studies have not shown a consistent relationship between abnormal glucose metabolism and serum AGEs. We investigated the relationship between a dominant serum AGE, N-carboxymethyl-lysine (CML), and glucose metabolism.

Subjects and Methods

Serum CML, fasting plasma glucose, and glucose tolerance were measured in 755 adults in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Fasting plasma glucose was categorized as normal (≤99 mg/dL), impaired (100-125 mg/dL), and diabetic (>125 mg/dL). Two-hour plasma glucose on oral glucose tolerance testing was categorized as normal (≤139 mg/dL), impaired (140-199 mg/dL), and diabetic (>200 mg/dL).

Results

The proportion of adults with normal, impaired, and diabetic fasting plasma glucose was 73.8%, 22.9%, and 2.9%, respectively, and the proportion with normal, impaired, and diabetic 2-hour plasma glucose was 73.1%, 19.2%, and 7.7%, respectively. Serum CML (μg/mL) was not associated with abnormal fasting plasma glucose (Odds Ratio [O.R.] 0.60, 95% Confidence Interval [C.I.] 0.15-2.36, P = 0.47) in a multivariate, ordered logistic regression model, adjusting for age, race, gender, body mass index, and chronic diseases. Serum CML (μg/mL) was associated with abnormal 2-hour plasma glucose on glucose tolerance testing (O.R. 0.15, 95% C.I. 0.04-0.63, P = 0.009) in a multivariate, ordered logistic regression model, adjusting for the same covariates.

Conclusions

Elevated CML, a dominant AGE, was not associated with elevated fasting plasma glucose and was associated with a reduced odds of abnormal glucose tolerance in older community-dwelling adults.

Keywords: advanced glycation end products, aging, diabetes, glucose tolerance

Introduction

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are bioactive molecules that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes, atherosclerosis, and renal insufficiency (1,4,27). AGEs are formed by the non-enzymatic glycation of proteins and other molecules. Two major sources of AGEs are exogenous AGEs ingested in foods and endogenous AGEs formed in the body. The generation of AGEs is widely thought to be increased in patients with diabetes (27). Carboxymethyl-lysine (CML) is a dominant AGE in both serum and tissues (4,20), and elevated serum CML concentrations have been described in patients with diabetes and related complications (3,5).

Although hyperglycemia is thought to increase the endogenous production of AGEs, the clinical evidence that AGEs are associated with abnormal glucose metabolism has been inconsistent between studies. Elevated serum CML concentrations have been described in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes (2,11) and are deposited in higher concentrations in cardiac tissue in diabetic subjects (21). Abnormal fasting plasma glucose was not correlated with serum AGEs in diabetics (17). Serum AGEs and hemoglobin A1c were significantly correlated in two studies (17,26), but no correlation was found in four other studies (10,13,19,24). We postulated that higher fasting plasma glucose and abnormal glucose tolerance are associated with elevated serum AGE concentrations. To address this hypothesis, we characterized the relationship between fasting plasma glucose and glucose tolerance with serum CML, a dominant AGE, in a cohort of community-dwelling men and women.

Methods

Subjects

The study subjects consisted of participants in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) who were seen between April 2002 and August 2007. The BLSA is a prospective open cohort study of community-dwelling volunteers, largely from the Baltimore/Washington area. The study was established in 1958 and is described in detail elsewhere (25). BLSA participants return every two years to the Gerontology Research Center in Baltimore, Maryland, for 2.5 days of medical, physiological, and psychological examinations (25). Blood pressure was measured in the morning, after a light breakfast, with subjects in the seated position, and after a quiet resting period of 5 min. Blood pressure (BP) was measured in both arms with a mercury sphygmomanometer using an appropriately sized cuff. The BP values used in this study are the average of the second and third measurements on both the right and left arms. Height, weight, and waist circumference were measured in all participants. Body mass index was determined as kg/m2. Smoking status was ascertained by a questionnaire that classified each subject as a non-smoker, former smoker, or current smoker. The BLSA has continuing approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the MedStar Research Institute, and the protocol for the present study was also approved by the IRB of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Laboratory methods

Blood samples were drawn from the antecubital vein between 7 and 8 AM after an overnight fast. Subjects were not allowed to smoke, engage in physical activity, or take medications before the sample was collected. Subjects were sitting in a semi-reclining chair during glucose tolerance testing (GTT). Fasting plasma and serum were collected at baseline, after which subjects drank 75 g glucose in 300 mL solution (SunDex; Fisherbrand, Pittsburgh, PA), and blood samples were drawn 2 h after oral administration. Concentrations of plasma triglycerides and total cholesterol were determined by an enzymatic method (Abbott Laboratories ABA-200 ATC Biochromatic Analyzer, Irving, TX). The concentration of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol was determined by a dextran sulfate-magnesium precipitation procedure (30). Serum interleukin-6 was measured using an immunoassay (Quantikine IL-6, R & D Systems, Minneapolis). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol concentrations were estimated by using the Friedewald formula (8). Hemoglobin A1c was measured by a BioRad Instrument (Hercules, CA). Plasma glucose concentration was measured by the glucose oxidase method (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, CA). Samples were stored continuously at −70° C until the time of analysis of serum AGEs. The measure of serum AGEs in this study was serum carboxymethyl-lysine (CML). CML is a dominant circulating AGE, one of the best characterized of all the AGEs, and a dominant AGE in tissue proteins (20). CML was measured in duplicate using a competitive ELISA (AGE-CML ELISA, Microcoat, Penzberg, Germany) (3). This assay has been validated (31), is specific, and shows no cross-reactivity with other compounds (3).

Statistical methods

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation. Body mass index was categorized as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal range (18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (>25-29.9 kg/m2) and obese (>30 kg/m2) according to World Health Organization criteria (12). Normal fasting glucose (NFG), impaired fasting glucose (IFG), and diabetic fasting glucose (DFG) were defined as fasting plasma glucose ≤99 mg/dL, 100-125 mg/dL, and >125 mg/dL, respectively (6). Normal glucose tolerance (NGT), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and diabetic glucose tolerance (DGT) were defined as 2-h plasma glucose of ≤139 mg/dL, 140-199 mg/dL, and >200 mg/dL, respectively (6). Renal insufficiency was defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation of Levey and colleagues (15). Subjects with LDL >160 mg/dL were classified as having high LDL (7). Ordered multivariate logistic regression models were used to examine the relationship between serum CML (per 1 standard deviation [SD]), demographic, anthropometric, laboratory, and clinical characteristics and fasting plasma glucose and glucose tolerance. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.13 (Cary, NC).

Results

The proportion of adults with normal, impaired, and diabetic fasting plasma glucose was 73.8%, 22.9%, and 2.9%, respectively, and the portion with normal, impaired, and diabetic 2-hour plasma glucose was 73.1%, 19.2%, and 7.7%, respectively. Demographic, disease, and other characteristics of the 755 study subjects by normal, impaired, and diabetic fasting glucose concentrations are shown in Table 1. There were significant differences in age, race, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and the proportion of subjects with hypertension, diabetes, angina, myocardial infarction, and renal insufficiency between the three different fasting glucose categories. There were no significant differences between the three groups in serum CML, current smoking, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, stroke, heart failure, cancer, and osteoarthritis. The proportion of subjects in this study with stroke and/or heart failure was <2%.

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Subjects by Fasting Plasma Glucose Concentrations in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.

| Characteristic | Fasting Plasma Glucose | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤99 mg/dL (n = 557) |

100-125 mg/dL (n = 173) |

>125 mg/dL (n = 25) |

|||

| Age (years) | 62.0 (14.1) | 68.1 (11.7) | 69.8 (10.9) | <0.0001 | |

| Male gender (%) | 44.5 | 65.3 | 72.0 | <0.0001 | |

| Race, white (%) | 52.0 | 60.7 | 67.3 | 0.03 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (%) |

<18.5 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0 | <0.0001 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 40.4 | 18.5 | 8.0 | ||

| 25.0-29.9 | 35.6 | 46.8 | 32.0 | ||

| ≥30 | 23.3 | 34.1 | 60.0 | ||

| Current smoking (%) | 4.7 | 3.5 | 16.0 | 0.27 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 124 (16) | 131 (15) | 135 (16) | <0.0001 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 70 (9) | 72 (10) | 71 (9) | 0.007 | |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 5.3 (0.5) | 5.6 (0.6) | 6.7 (1.7) | <0.0001 | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 99 (62) | 114 (67) | 159 (83) | <0.0001 | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 196 (36) | 191 (38) | 185 (33) | 0.08 | |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 117 (33) | 115 (32) | 107 (32) | 0.28 | |

| LDL cholesterol ≥ 160 mg/dL (%) | 10.3 | 10.4 | 8.0 | 0.86 | |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 60 (18) | 54 (15) | 46 (16) | <0.0001 | |

| Serum CML (μg/mL) | 0.47 (0.13) | 0.47 (0.14) | 0.46 (0.15) | 0.66 | |

| Hypertension (%) | 25.8 | 45.7 | 56.0 | <0.0001 | |

| Diabetes (%) | 1.4 | 12.7 | 56.0 | <0.0001 | |

| Angina (%) | 9.3 | 13.9 | 28.0 | 0.003 | |

| Myocardial infarction (%) | 2.3 | 7.5 | 12.0 | 0.0002 | |

| Stroke (%) | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.87 | |

| Heart failure (%) | 0.4 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.14 | |

| Cancer (%) | 9.7 | 12.7 | 16.0 | 0.35 | |

| Osteoarthritis (%) | 25.0 | 27.7 | 20.0 | 0.62 | |

| Renal insufficiency (%) | 2.5 | 2.9 | 12.0 | 0.03 | |

Serum CML was not associated with abnormal fasting plasma glucose concentrations in multivariate ordered logistic regression models adjusting for age, race, gender, and body mass index, and also after further adjusting for hypertension, angina, myocardial infarction, and renal insufficiency (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariate Ordered Logistic Regression Models for Serum CML and Other Factors with Abnormal Fasting Plasma Glucose Concentrations in Adults in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||

| Serum CML (μg/mL)1 | 0.33 | 0.09-1.18 | 0.08 | |

| Age (years) | 1.04 | 1.03-1.05 | <0.0001 | |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Serum CML (μg/mL)1 | 0.68 | 0.18-2.63 | 0.57 | |

| Age (years) | 1.05 | 1.03-1.06 | <0.0001 | |

| Race (white) | 0.57 | 0.39-0.82 | 0.003 | |

| Male gender | 2.20 | 1.54-3.15 | <0.0001 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 3.23 | 0.32-32.32 | 0.75 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 1.00 | --- | --- | |

| 25.0-29.9 | 2.63 | 1.66-4.16 | 0.82 | |

| ≥30 | 4.21 | 2.56-6.92 | 0.09 | |

| Model 3 | ||||

| Serum CML (μg/mL)1 | 0.60 | 0.15-2.36 | 0.47 | |

| Age (years) | 1.04 | 1.02-1.06 | <0.0001 | |

| Race (white) | 0.61 | 0.42-0.90 | 0.01 | |

| Male gender | 2.13 | 1.43-3.16 | 0.0002 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 2.48 | 0.23-26.27 | 0.87 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 1.00 | --- | --- | |

| 25.0-29.9 | 2.40 | 1.51-3.82 | 0.74 | |

| ≥30 | 3.62 | 2.18-5.99 | 0.11 | |

| Hypertension | 1.64 | 1.12-2.38 | 0.01 | |

| Angina | 0.81 | 0.46-1.43 | 0.47 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.72 | 0.76-3.90 | 0.19 | |

| Renal insufficiency | 1.06 | 0.70-1.62 | 0.77 | |

Per 1 SD increase in CML (0.13 μg/mL).

Demographic, disease, and other characteristics of 754 study subjects as classified by normal, impaired, and diabetic 2-hour plasma glucose concentrations on oral glucose tolerance testing are shown in Table 3. One participant with fasting plasma glucose concentrations was missing 2-hour glucose concentration measurements. There were significant differences in age, race, body mass index, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, serum CML, and the proportion of subjects with hypertension, diabetes, angina, and myocardial infarction between the three different 2-hour plasma glucose categories. There were no significant differences in diastolic blood pressure or the proportion of subjects who were current smokers, or who had history of stroke, heart failure, cancer, or osteoarthritis between the three different 2-hour plasma glucose categories. A higher prevalence of renal insufficiency was marginally associated with abnormal 2-hour plasma glucose (P = 0.06).

Table 3. Characteristics of Study Subjects by Oral Glucose Tolerance Test in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.

| Characteristic | 2-Hour Plasma Glucose | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤139 mg/dL (n = 551) |

140-199 mg/dL (n = 145) |

≥200 mg/dL (n = 58) |

|||

| Age (years) | 61.8 (13.7) | 67.6 (13.0) | 71.7 (11.2) | <0.0001 | |

| Male gender (%) | 45.4 | 62.1 | 65.5 | <0.0001 | |

| Race, white (%) | 67.2 | 66.9 | 64.8 | 0.58 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) |

<18.5 | 0.4 | 2.4 | 1.7 | <0.0001 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 39.4 | 23.5 | 13.8 | ||

| 25.0-29.9 | 37.4 | 37.2 | 44.8 | ||

| ≥30 | 22.9 | 37.9 | 39.7 | ||

| Current smoking (%) | 3.3 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 0.87 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 125 (15) | 133 (15) | 132 (18) | <0.0001 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 70 (15) | 71 (8) | 70 (12) | 0.29 | |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 5.4 (0.5) | 5.5 (0.5) | 6.3 (1.2) | <0.0001 | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 97 (61) | 121 (68) | 140 (77) | <0.0001 | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 197 (35) | 193 (37) | 190 (44) | 0.0005 | |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 117 (33) | 116 (31) | 107 (39) | 0.02 | |

| LDL cholesterol ≥ 160 mg/dL (%) | 11.1 | 8.9 | 5.2 | 0.13 | |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 61 (18) | 54 (17) | 47 (11) | <0.0001 | |

| Serum CML (μg/mL) | 0.48 (0.13) | 0.44 (0.14) | 0.46 (0.15) | 0.007 | |

| Hypertension (%) | 26.9 | 40.7 | 51.7 | <0.0001 | |

| Diabetes (%) | 1.3 | 5.5 | 50.0 | <0.0001 | |

| Angina (%) | 8.4 | 16.6 | 22.4 | 0.0003 | |

| Myocardial infarction (%) | 2.9 | 4.8 | 10.3 | 0.02 | |

| Stroke (%) | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.76 | |

| Heart failure (%) | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 0.24 | |

| Cancer (%) | 9.3 | 13.8 | 15.5 | 0.13 | |

| Osteoarthritis (%) | 25.2 | 24.8 | 29.3 | 0.78 | |

| Renal insufficiency (%) | 36.1 | 38.6 | 51.7 | 0.06 | |

Serum CML (per 1 SD increase) was significantly associated with abnormal 2-hour plasma glucose concentrations on oral glucose tolerance testing in multivariate ordered logistic regression models adjusting for age, gender, race, and body mass index, and also adjusting further for hypertension, angina, myocardial infarction, and renal insufficiency (Table 4). It is striking that the odds ratios suggest that elevated serum CML is associated with a lower odds of having impaired or diabetic glucose tolerance.

Table 4. Multivariate Ordered Logistic Regression Models for Serum CML and Other Risk Factors Associated with Abnormal Oral Glucose Tolerance in Adults in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||

| Serum CML (μg/mL)1 | 0.09 | 0.02-0.32 | 0.0003 | |

| Age (years) | 1.05 | 1.03-1.06 | <0.0001 | |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Serum CML (μg/mL)1 | 0.16 | 0.04-0.62 | 0.008 | |

| Age (years) | 1.05 | 1.04-1.07 | <0.0001 | |

| Male gender | 1.83 | 1.29-2.59 | 0.0007 | |

| Race (white) | 0.90 | 0.62-1.31 | 0.58 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 21.08 | 3.82-116.42 | 0.004 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 1.00 | --- | --- | |

| 25.0-29.9 | 2.05 | 1.20-2.88 | 0.02 | |

| ≥30 | 3.42 | 2.05-5.25 | 0.91 | |

| Model 3 | ||||

| Serum CML (μg/mL)1 | 0.15 | 0.04-0.63 | 0.009 | |

| Age (years) | 1.05 | 1.04-1.07 | <0.0001 | |

| Race (white) | 1.09 | 0.74-1.60 | 0.68 | |

| Male gender | 2.11 | 1.43-3.11 | 0.0002 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 22.14 | 3.98-123.00 | 0.003 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 1.00 | --- | --- | |

| 25.0-29.9 | 1.78 | 1.14-2.78 | 0.01 | |

| ≥30 | 3.13 | 1.93-5.07 | 0.80 | |

| Hypertension | 1.46 | 1.01-2.11 | 0.05 | |

| Angina | 1.56 | 0.92-2.64 | 0.10 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.78 | 0.35-1.75 | 0.54 | |

| Renal insufficiency | 0.59 | 0.39-0.89 | 0.01 | |

Per 1 SD increase in CML (0.13 μg/mL).

Since CML can also be generated by lipoxidation and through the myeloperoxidase pathway in the presence of inflammation or chronic disease, the relationship between demographic factors, lipids, IL-6, and chronic diseases with serum CML was examined in univariate linear regression models (Table 5). Age, body mass index, current smoking triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, angina, osteoarthritis, and renal insufficiency were significantly associated with log serum CML concentrations. IL-6 and total cholesterol were not significantly associated with log serum CML concentrations. The variables that were significantly associated with log serum CML in univariate analyses were entered into a multivariate linear regression model together (Table 6). In a final multivariate model, body mass index, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and renal insufficiency were significantly associated with log serum CML.

Table 5. Univariate Linear Regression Models of Serum Lipids, Interleukin-6, and Other Factors with Log Serum Carboxymethyl-lysine.

| Characteristic | Beta | SE | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.004 | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Male gender | 0.008 | 0.021 | 0.72 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −0.016 | 0.002 | <0.0001 |

| Current smoking | −0.098 | 0.049 | 0.05 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | −0.006 | 0.004 | 0.14 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | −0.001 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | −0.00003 | 0.0035 | 0.92 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | −0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.49 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.004 | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 0.035 | 0.023 | 0.12 |

| Diabetes | −0.008 | 0.045 | 0.86 |

| Angina | 0.066 | 0.034 | 0.05 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.007 | 0.055 | 0.90 |

| Stroke | −0.105 | 0.168 | 0.53 |

| Cancer | 0.065 | 0.034 | 0.06 |

| Osteoarthritis | 0.064 | 0.024 | 0.008 |

| Renal insufficiency | 0.110 | 0.028 | <0.0001 |

Table 6. Multivariate Linear Regression Model for Lipids and Other Factors with Log Serum Carboxymethyl-lysine.

| Characteristic | Beta | SE | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.06 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −0.013 | 0.003 | <0.0001 |

| Current smoking | −0.080 | 0.052 | 0.12 |

| Triglycerides | −0.001 | 0.0002 | 0.0009 |

| HDL cholesterol | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Angina | 0.055 | 0.040 | 0.16 |

| Osteoarthritis | 0.039 | 0.028 | 0.17 |

| Renal insufficiency | 0.117 | 0.034 | 0.0006 |

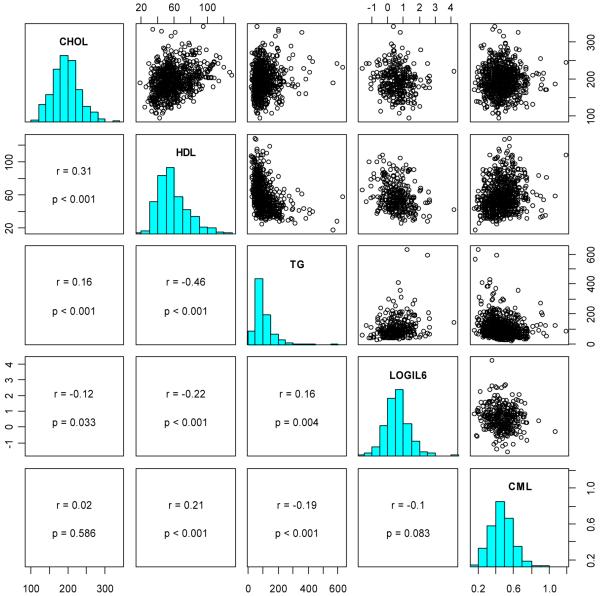

The Spearman correlations and scatterplots of total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, IL-6, and serum CML are shown in Figure 1. CML was positively correlated with HDL cholesterol and negatively correlated with triglycerides. There was no significant correlation between CML and log IL-6 or with total cholesterol.

Figure 1.

Paired scatterplots and correlations between total cholesterol (CHOL), HDL cholesterol (HDL), triglycerides (TG), log interleukin-6 (LOGIL6), and carboxymethyl-lysine (CML). On the diagonal, the marginal distributions are shown as histograms. In the lower left of the triangle, the respective correlation coefficients, confidence intervals, and p-values are shown. For clarity, and since correlations are scale independent, we omitted the axis labels.

Discussion

Using data from a community-dwelling population of men and women and extensive measures of glucose metabolism, we found no evidence that serum CML, a dominant AGE, is associated with impaired glucose metabolism. On the contrary, adults with elevated serum CML were less likely to show impaired or diabetic 2-hour plasma glucose concentrations on oral glucose tolerance testing. These findings are in frank contrast to our original hypothesis, since it has been widely thought that abnormal glucose metabolism leads to the increased endogenous generation of systemic AGEs. However, our findings are consistent with a previous study that found no relationship between serum CML and fasting plasma glucose (17), and other studies where the relationship between serum AGEs and hemoglobin A1c was inconsistent (10,13,17,19,24,26). In a recent longitudinal study, the authors were unable to detect any significant change in CML concentration after insulin treatment that normalized plasma glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes (16). The discrepancy between elevated serum CML concentrations in diabetic subjects (2,3,11) might be explained by the hypothesis that the endogenous generation of AGEs is important among people with advanced diabetes and advanced renal disease but not in relatively healthy community-dwelling adults, such as participants in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging.

Our previous studies show that older adults with elevated serum CML have a higher risk of cardiovascular mortality (22) and incident renal insufficiency (23), which underscores the potential clinical relevance of serum CML as a marker for AGEs in humans. A limitation of the study is that multiple AGEs were not measured in the circulation. Measurement of multiple AGEs in large epidemiological studies involving hundreds of participants can be a challenge. When multiple AGEs have been measured in studies involving smaller numbers of participants, moderate and significant correlations have been described between the circulating AGEs (27

A strength of this study is that abnormal glucose metabolism was carefully assessed by both fasting plasma glucose and oral glucose tolerance testing in a large sample of community-dwelling adults. The findings cannot necessarily be extrapolated to men and women with a higher burden of chronic diseases, those with advanced diabetes, and people with end-stage renal disease. It is noteworthy that most of the previous literature has focused on the relationship between AGEs and clinical outcomes in groups of patients with diabetes and renal disease.

As CML can also be formed through lipoxidation, the relationship between lipids and CML were examined in the present study. Triglycerides were negatively correlated and HDL cholesterol was positively correlated with serum CML. No relationship was found between total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol with serum CML concentrations.

The relative contribution of diet to serum CML concentrations in the present study cannot be addressed, since dietary intake of AGEs must be assessed using special dietary questionnaires, and such information is not available in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Western diets are rich in AGEs, as AGEs are found in foods processed at high temperatures (9,13). About 10% of ingested AGEs are absorbed and two-thirds are retained in tissues (14). Studies by Uribarri and colleagues show that dietary intake of AGEs correlates well with serum AGE levels (27,28). In patients with diabetes or renal failure, serum CML concentrations can be increased or decreased up to one-half or greater through dietary restriction or increased consumption of AGEs in food (18,28).

In conclusion, elevated serum CML concentrations were not associated with elevated fasting plasma glucose and were associated with reduced odds of abnormal glucose tolerance in older community-dwelling adults. The relative contribution of diet versus abnormal glucose metabolism as sources of AGEs needs to be investigated further in community-dwelling adults.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant R01 AG027012, R01 AG029148, and the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, NIH.

References

- 1.Basta G, Schmidt AM, de Caterina R. Advanced glycation end products and vascular inflammation: implications for accelerated atherosclerosis in diabetes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;63:582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg TJ, Clausen JT, Torjesen PA, Dahl-Jørgensen K, Bangstad HJ, Hanssen KF. The advanced glycation end product Nε(carboxymethyl)lysine is increased in serum from children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1997–2002. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.11.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boehm BO, Schilling S, Rosinger S, Lang GE, Lang GK, Kietsch-Engel R, Stahl P. Elevated serum levels of Nε-carboxymethyl-lysine, an advanced glycation end product, are associated with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and macular oedema. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1376–1379. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1455-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohlender JM, Franke S, Stein G, Wolf G. Advanced glycation end products and the kidney. Am. J. Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F645–F659. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00398.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busch M, Franke S, Wolf G, Brandstädt A, Ott U, Gerth J, Hunsicker GL, Stein G. The advanced glycation end product Nε-carboxymethyllysine is not a predictor of cardiovascular events and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetic kidney disease and hypertension. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2006;48:571–579. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3160–3136. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Frederikson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg T, Cai W, Peppa M, Dardaine V, Baliga BW, Uribarri J, Vlassara H. Advanced glycoxidation end products in commonly consumed foods. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004;104:1287–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.05.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirata K, Kubo K. Relationship between blood levels of N-carboxymethyl-lysine and pentosidine and the severity of microangiopathy in type 2 diabetes. Endocrine J. 2004;51:537–544. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.51.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang JS, Shin CH, Yang SW. Clinical implications of Nε(carboxymethyl)lysine, advanced glycation end product, in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2005;7:263–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2004.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James PT, Leach R, Kalamara E, Shayeghi M. The worldwide obesity epidemic. Obes. Res. 2001;9(suppl 4):228S–233S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilhovd BK, Berg TJ, Birkeland KI, Thorsby P, Hanssen KF. Serum levels of advanced glycation end products are increased in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1543–1548. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koschinsky T, He CJ, Mitsuhashi T, Bucala R, Liu C, Buenting C, Heitmann K, Vlassara H. Orally absorbed reactive glycation products (glycotoxins): an environmental risk factor in diabetic nephropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6474–6479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mentink CJAL, Kilhovd BK, Rondas-Colbers GJWM, Torjesen PA, Wolffenbuttel BHR. Time course of specific AGEs during optimized glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes. Netherlands J. Med. 2006;64:10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miura J, Yamagishi SI, Uchigata Y, Takeuchi M, Yamamoto H, Makita Z, Iwamoto Y. Serum levels of non-carboxymethyllysine advanced glycation endproducts are correlated to severity of microvascular complications in patients with type 1 diabetes. J. Diabet. Compl. 2003;17:16–21. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(02)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Negrean M, Stirban A, Stratmann B, Gawlowski T, Horstmann T, Götting C, Kleesiek K, Mueller-Roesel M, Koschinsky T, Uribarri J, Vlassara H, Tschoepe D. Effects of low- and high-advanced glycation endproduct meals on macro- and microvascular endothelial function and oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;85:1236–1243. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ono Y, Aoki S, Ohnishi K, Yasuda T, Kawano K, Tsukada Y. Increased serum levels of advanced glycation end-products and diabetic complications. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 1998;41:131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(98)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy S, Bichler J, Wells-Knecht KJ, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. N epsilon-(carboxymethyl)lysine is a dominant advanced glycation end product (AGE) antigen in tissue proteins. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10872–10878. doi: 10.1021/bi00034a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schalkwijk CG, Baidoshvili A, Stehouwer CD, van Hinsbergh VW, Niessen HW. Increased accumulation of the glycoxidation product Nε(carboxymethyl)lysine in hearts of diabetic patients: generation and characterization of a monoclonal anti-CML antibody. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1636:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Semba RD, Bandinelli S, Sun K, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Plasma carboxymethyl-lysine, and advanced glycation end product, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in older community-dwelling adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009 Aug 13; doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02438.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semba RD, Fink JC, Sun K, Bandinelli S, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Carboxymethyl-lysine, an advanced glycation end product, and decline of renal function in older community-dwelling adults. Eur J Nutr. 2009;48:38–44. doi: 10.1007/s00394-008-0757-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharp PS, Rainbow S, Mukherjee S. Serum levels of low molecular weight advanced glycation end products in diabetic subjects. Diabet. Med. 2003;20:575–579. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shock NW, Greulich RC, Andres RA, Arenberg D, Casta PT, Lakatta EG, Tobin JP. Normal Human Aging: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D.C.: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan KCB, Chow WS, Ai VHG, Metz C, Bucala R, Lam KSL. Advanced glycation end products and endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1055–1059. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.6.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uribarri J, Cai W, Peppa M, Goodman S, Ferrucci L, Striker G, Vlassara H. Circulating glycotoxins and dietary advanced glyation endproducts: two links to inflammatory response, oxidative stress, and aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007;72:427–433. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uribarri J, Peppa M, Cai W, Goldberg T, Lu M, Baliga S, Vassalotti JA, Vlassara H. Dietary glycotoxins correlate with circulating advanced glycation end product levels in renal failure patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2003;42:532–538. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00779-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vlassara H, Striker G. Glycotoxins in the diet promote diabetes and diabetic complications. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2007;7:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s11892-007-0037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warnick G, Benderson J, Albers J. Dextran sulfate-Mg2+ precipitation procedure for quantification of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol. Clin. Chem. 1982;28:1379–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, Frischmann M, Kientsch-Engel R, Steinmann K, Stopper H, Niwa T, Pischetsrieder M. Two immunochemical assays to measure advanced glycation end-products in serum from dialysis patients. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2005;43:503–511. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]