Abstract

Daily rhythmic processes are coordinated by circadian clocks, which are present in numerous central and peripheral tissues. In mammals, two circadian clocks, the food-entrainable oscillator (FEO) and methamphetamine-sensitive circadian oscillator (MASCO), are “black box” mysteries because their anatomical loci are unknown and their outputs are not expressed under normal physiological conditions. In the current study, the investigation of the timekeeping mechanisms of the FEO and MASCO in mice with disruption of all three paralogs of the canonical clock gene, Period, revealed unique and convergent findings. We found that both the MASCO and FEO in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice are circadian oscillators with unusually short (∼21 h) periods. These data demonstrate that the canonical Period genes are involved in period determination in the FEO and MASCO, and computational modeling supports the hypothesis that the FEO and MASCO use the same timekeeping mechanism or are the same circadian oscillator. Finally, these studies identify Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice as a unique tool critical to the search for the elusive anatomical location(s) of the FEO and MASCO.

Keywords: food anticipatory activity, restricted feeding, suprachiasmatic nuclei, knockout, C57BL/6J

Temporal processes are controlled by circadian clocks, which produce self-sustained oscillations in physiology and behavior with endogenous periods of ∼24 h that can be synchronized to environmental cues such as the light/dark cycle and food availability. Circadian studies have traditionally focused on the master clock in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN), and more recently on peripheral oscillators such as those in liver and muscle. Two extra-SCN oscillators, the food-entrainable oscillator (FEO) and methamphetamine-sensitive circadian oscillator (MASCO), have been defined on the basis of circadian behavioral rhythms induced by food and methamphetamine, respectively, but these remain “black box” mysteries because their anatomical loci are unknown and their outputs are not expressed under normal physiological conditions (1–4).

Recent studies of the FEO and MASCO have suggested that they use a molecular timekeeping mechanism that is distinct from other circadian oscillators because they function when the canonical circadian genes are disrupted (5–11; see also refs. 12, 13). Because only two paralogs of the Period gene, Per1 and Per2, are necessary to generate circadian rhythms in the SCN, previous studies concluded that the FEO and MASCO are “noncanonical” clocks in part because they are functional in Per1−/−/Per2−/− mice (5, 6). Although the third Period paralog, Per3, is not usually considered a functional component of circadian clocks, we recently demonstrated that Per3 participates in period determination in certain peripheral circadian oscillators (14, 15). We hypothesized that Per3 may also be a constituent of the FEO and MASCO and/or could be compensating for the loss of functional PER1 and PER2, therefore necessitating analyses of the FEO and MASCO in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice.

The current study of the FEO and MASCO in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice revealed unique and convergent findings. Though we confirmed the previous finding that the MASCO is rhythmic when the canonical clock genes are disrupted, we found that the Period genes are, in fact, involved in determining the periods of the FEO and MASCO. Furthermore, both the FEO and MASCO had similar and unusually short periods, suggesting that they may be the same oscillator or that they use the same timekeeping mechanism.

Results

Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− MASCO Is a Circadian Oscillator with a Short Period.

We first generated Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice congenic with the C57BL/6J strain and found that their wheel-running activity appeared rhythmic in the light/dark cycle, with activity beginning ∼2 h before lights off in 12 h light/12 h dark (12L:12D; Fig. 1 and Fig. S1) and ∼5 h before lights off in 18L:6D (Fig. 2 and Fig. S4), but their daily rhythms of activity were abolished in constant darkness [similar to other circadian mutant mice (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1); the wild-type wheel-running activity rhythm is shown in Fig. 1A for reference]. These data suggest that the light/dark cycle can drive rhythmicity in the SCN (alternatively, the light/dark input could drive rhythmicity in another brain region associated with masking, but we will refer to it as the SCN rhythm herein for ease of discussion) in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice, but the SCN rhythm is abrogated in constant darkness.

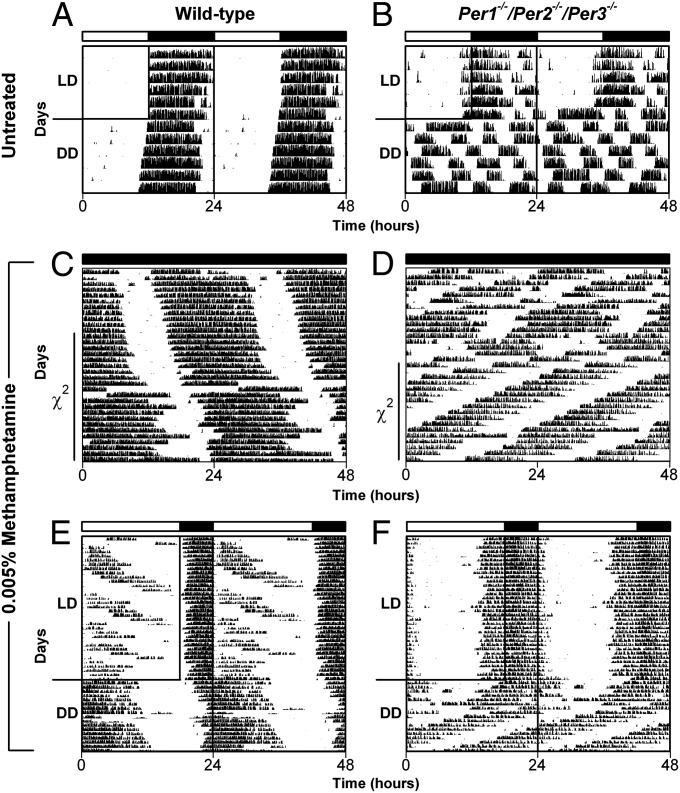

Fig. 1.

The period of the MASCO rhythm is short in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice. Representative double-plotted actograms (5-min bins) from wild-type (A, C, and E) and Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− (B, D, and F) mice. (A and B) Mice (no methamphetamine treatment) were maintained in 12L:12D (LD; indicated by white and black bars above actograms; the time of darkness is outlined on the left halves of the actograms) for 6 d and then released into constant darkness (DD) for 6 d. (C and D) Mice were maintained in constant darkness (black bar above actograms) and administered 0.005% methamphetamine in their drinking water (days 1–33 of methamphetamine treatment shown in the actograms). The days used for χ2 periodogram are indicated by solid vertical lines. (E and F) Mice were administered 0.005% methamphetamine and maintained in 18L:6D for 78 d and then released into DD (days 45–95 of methamphetamine treatment are shown here). The untreated wild-type data (shown in A) was taken from our previously published dataset (14). (B–F) Representative actograms from a total of n = 10, 3, 6, 4, and 3 observations, and all individual actograms are presented in Fig. S1 (B), Fig. S2 A and B (C and D), and Fig. S3 A and B (E and F), respectively.

Fig. 2.

Food anticipatory activity during daily (24-h) restricted feeding of Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice in the light/dark cycle. (A) Representative double-plotted actogram of wheel-running activity (5-min bins) of a Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mouse maintained in the light/dark cycle (18L:6D, light/dark conditions indicated by white and black bars, respectively, above the actogram, and the dark phase is outlined with a black box on the left half of the actogram). The time when food was available is shown by gray shading on the left half of the actogram. Activity onset occurred ∼5 h before lights off and ended at lights on during ad libitum feeding. The mouse was fed ad libitum for 5 d, then fasted for 48 h to characterize activity during fasting before restricted feeding. The mouse was returned to ad libitum feeding for 3 d, then fed 8 h/d for 2 d and then for 6 h/d for 9 d. On the 10th day of restricted feeding, food was left in the cage, and the mouse ate ad libitum for 3 d. The mouse was fasted for 48 h and then returned to ad libitum feeding. (B) χ2 periodogram analysis performed on days 1–9 of restricted feeding (indicated on the y axis of the actogram in A). The dotted line in the periodogram shows the significance level P = 0.001. A total of six individual actograms and periodograms are shown in Fig. S4.

To determine if the MASCO is functional in the absence of all functional PERIOD, we administered methamphetamine (0.005% in drinking water) to Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice in constant darkness (Fig. 1D; the SCN rhythm is dampened in constant darkness as shown in Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). After several days of methamphetamine treatment (1–12 d), all Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice examined exhibited short (∼21.5 h) methamphetamine-induced wheel-running activity rhythms (Fig. 1D and Fig. S2B). The Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− MASCO rhythm (n = 6) was significantly shorter than the >24-h wheel-running activity rhythms observed in wild-type mice (n = 3) administered methamphetamine (t = 5.9, P < 0.001; Fig. 1C and Fig. S2 A and C). These data demonstrate that although the MASCO is rhythmic when all Period paralogs are disrupted, functional PERIOD nonetheless participates in the period determination of MASCO.

The locomotor activity rhythm in wild-type rodents during short-term treatment with methamphetamine represents the integrated outputs of the SCN and MASCO, suggesting that the two oscillators are coupled (3, 16, 17) (Fig. 1C and Fig. S2A). However, during long-term exposure to methamphetamine in a 24-h light/dark cycle, the MASCO rhythm dissociates from the SCN-controlled activity rhythm in wild-type mice (1, 17, 18) (Fig. 1E and Fig. S3A; the MASCO rhythm dissociates from the SCN-controlled rhythm in three of four wild-type mice). To examine coupling between the light-driven SCN and the MASCO in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice, we administered methamphetamine (0.005%) to mice maintained in the light/dark cycle (18L:6D; Fig. 1F and Fig. S3B). We found that the MASCO rhythm did not dissociate from the light-driven SCN-controlled nocturnal activity rhythm during >75 d of methamphetamine treatment (compared with wild-type mice in the same condition in Fig. 1E and Fig. S3A), but was relatively coordinated to the light-driven SCN rhythm, as evidenced by the irregularity in the onset of activity (Fig. 1F). The 21-h period of the Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− MASCO rhythm was observed upon release of the mice into constant darkness (Fig. 1F; as in Fig. 1D and Fig. S2B). Furthermore, the MASCO rhythm appeared to free-run from the phase of activity onset in the light/dark cycle, suggesting that the Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− MASCO was entrained to the light/dark cycle (possibly through coupling with the light-driven SCN rhythm).

Variable Patterns of Daily Food Anticipatory Activity in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− Mice.

Food anticipatory activity, which is an output of the FEO, occurs before food availability only under conditions of timed food restriction. Food anticipatory activity can be distinguished from the locomotor activity rhythm controlled by the SCN (which occurs during the night in nocturnal mice) by restricting food availability to the daytime. To investigate timekeeping by the FEO in the absence of functional PERIOD, we first provided food only during the day to Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice in light/dark conditions (18L:6D; n = 6; Fig. 2 and Fig. S4 D–F: 6 h/day restricted feeding; Fig. S4 A–C: 4 h/d restricted feeding). Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice maintained in light/dark conditions (18L:6D) exhibited daytime food anticipatory activity before food availability. To determine if FEO timekeeping persisted in constant feeding conditions, we assessed food anticipatory activity during fasting after restricted feeding. We found that anticipatory activity returned at the same time of prior entrainment to feeding in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice in the light/dark cycle. These data suggest that in the light/dark cycle (in the presence of light-driven SCN rhythmicity), the FEO in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice entrains to the timing of food availability.

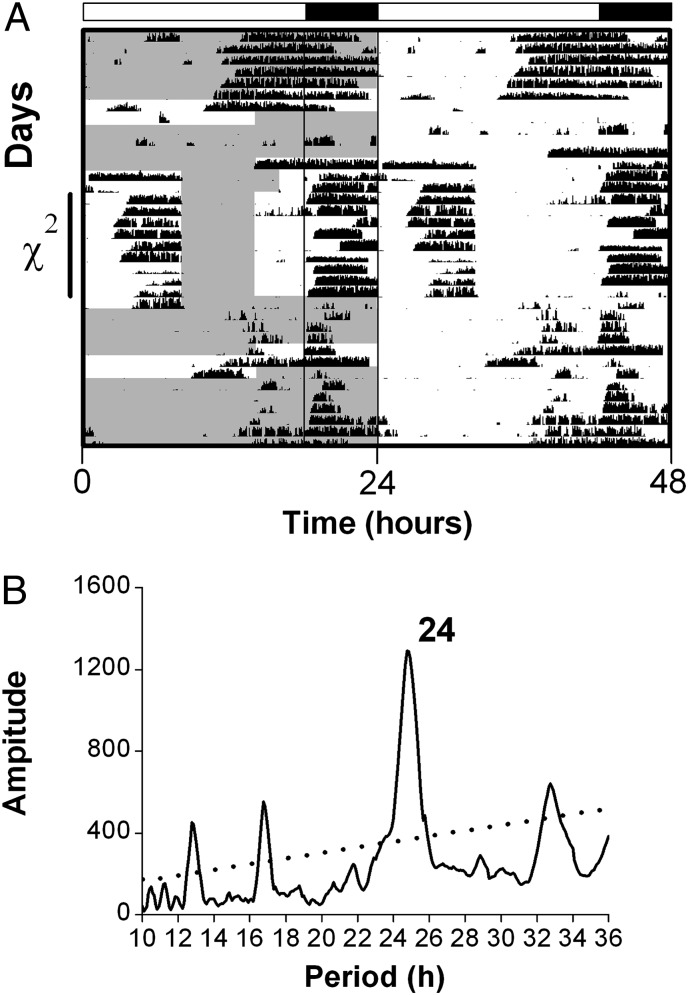

To eliminate the influence of the light-driven SCN rhythm on the FEO, we next restricted food availability to Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice (n = 15) in constant darkness (the mutant SCN is not rhythmic in constant darkness; Fig. 3A and Figs. S5 and S6: 6 h/d restricted feeding; Fig. 3C and Fig. S7: 4 h/d restricted feeding). During food deprivation before restricted feeding, most Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice exhibited ultradian bouts of activity as well as a long (12–24 h) bout of wheel-running activity. During restricted feeding, locomotor activity was typically consolidated before food presentation, but activity sometimes persisted until food was presented, whereas sometimes activity bouts occurred at various times before food was available (as seen in the group average activity profiles; Fig. S8 A–C). During food deprivation in the majority of Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice, activity during fasting did not occur at the predicted phase of entrainment to food availability and did not differ markedly from activity observed during food deprivation before restricted feeding (Fig. 3 A and C and Figs. S5–S7 and S8 A–C). From these data, we concluded that the Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− FEO did not entrain to the 24-h cycle of restricted feeding in constant darkness.

Fig. 3.

Variable patterns of food anticipatory activity during daily (24-h) restricted feeding of Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice in constant darkness. Representative double-plotted actograms (5-min bins) of wheel-running activity of Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice maintained in constant darkness (indicated by black bars above actograms). Gray shading on left halves of the actograms indicates when food was available. Mice were fed ad libitum for 5 d, then fasted for 48 h to characterize activity during fasting before restricted feeding. Mice were returned to ad libitum feeding for 3 d, then fed 8 h/d for 2 d. In A, the mouse was then fed for 6 h/d for 9 d, whereas in C, the mouse was fed for 6 h/d for 2 d and then 4 h/d for 9 d. On the 10th day of restricted feeding, food was left in the cage, and mice ate ad libitum for 2 d (A) or 4 d (C). Mice were then fasted for 48 h and returned to ad libitum feeding. The χ2 periodograms (B and D) correspond to the actograms shown in A and C, respectively. χ2 periodogram analysis was performed on days 1–10 of restricted feeding, as indicated on y axes of the actograms. The dotted lines in the periodograms show the significance level P = 0.001. All individual actograms and periodograms (n = 15 in total) are shown in Figs. S5, S6 and S7.

Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− FEO Is a Circadian Oscillator with a ∼21-h Period.

Our observation that the MASCO period is short in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice drew our attention to a similar pattern of activity during restricted feeding in these mice—namely, some components of the food anticipatory activity of Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice displayed a short (∼21 h) period similar to the period of the MASCO rhythm (Fig. 3 and Figs. S5–S7). χ2 periodogram analyses of locomotor activity during restricted feeding sometimes detected this ∼21-h period (in addition to the 24-h period; Figs. S5B and S6A), especially in mice fed 4 h/d (Fig. 3D and Fig. S7A).

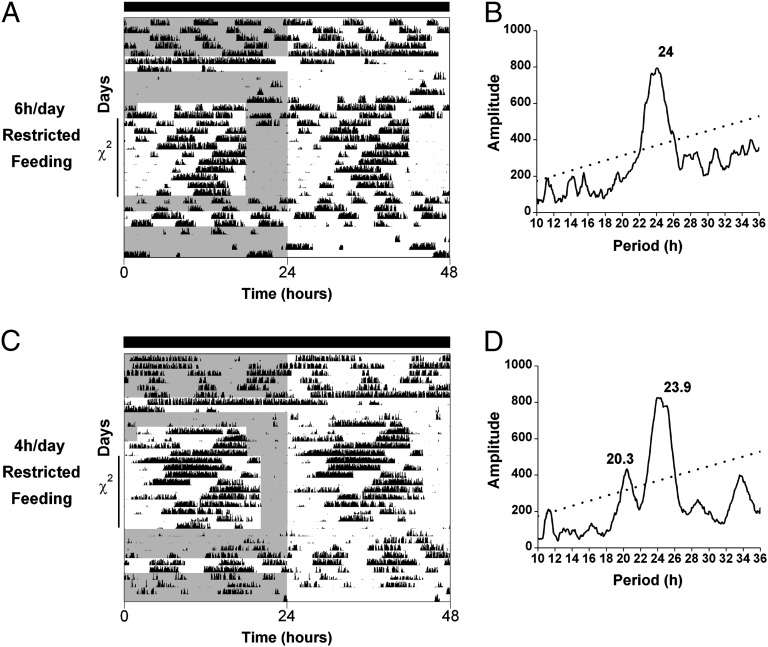

This observation led us to hypothesize that the Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− FEO is a circadian oscillator, but because it has a short (21 h) period, it is unable to entrain to the 24-h cycle of restricted feeding in constant darkness. To test this hypothesis, we performed restricted feeding of Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice on a 21-h cycle in constant darkness (n = 5; Fig. 4 and Fig. S9; food was available with a 21-h periodicity; group average activity profiles shown in Fig. S8D). Two Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice entrained to the 21-h cycle of restricted feeding and food anticipatory activity also persisted during food deprivation following an intervening day of ad libitum feeding (Fig. 4 A and B). Two other Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice took several days to entrain to the 21-h cycle of restricted feeding (Fig. 4 C and E). One Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mouse did not entrain to the 21-h cycle of restricted feeding (Fig. 4D). χ2 periodogram analyses detected only a 21-h period in the mice that entrained to the 21-h cycle of restricted feeding (Fig. S9 A–C and E). These data demonstrate that the Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− FEO is a circadian oscillator with a ∼21-h period.

Fig. 4.

Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice entrain to a 21-h cycle of food availability. (A–E) Double-plotted actograms (5-min bins) of wheel-running activity of Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice maintained in constant darkness (indicated by black bars above actograms). Gray shading on left halves of the actograms indicates when food was available. Mice were fed ad libitum for nine cycles and then fed 6 h per 21-h cycle for 12 cycles. Following one cycle of ad libitum feeding, mice were food-deprived for 36 h and then fed ad libitum. The data are plotted on a 21-h cycle (shown on x axes). All individual actograms (n = 5) are shown. Corresponding periodograms are shown in Fig. S8.

Computational Modeling of the FEO/MASCO and SCN as Coupled Limit-Cycle Oscillators.

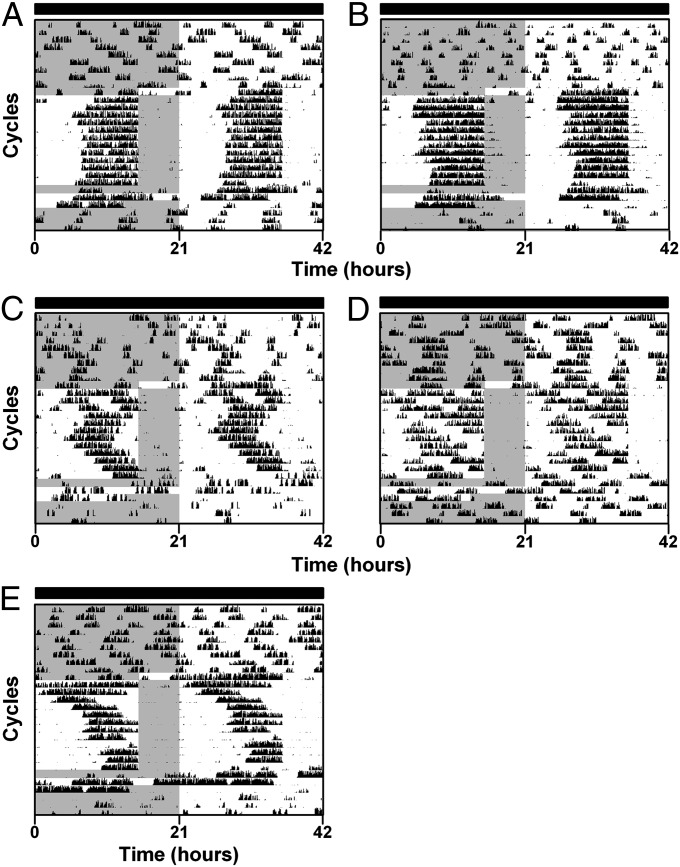

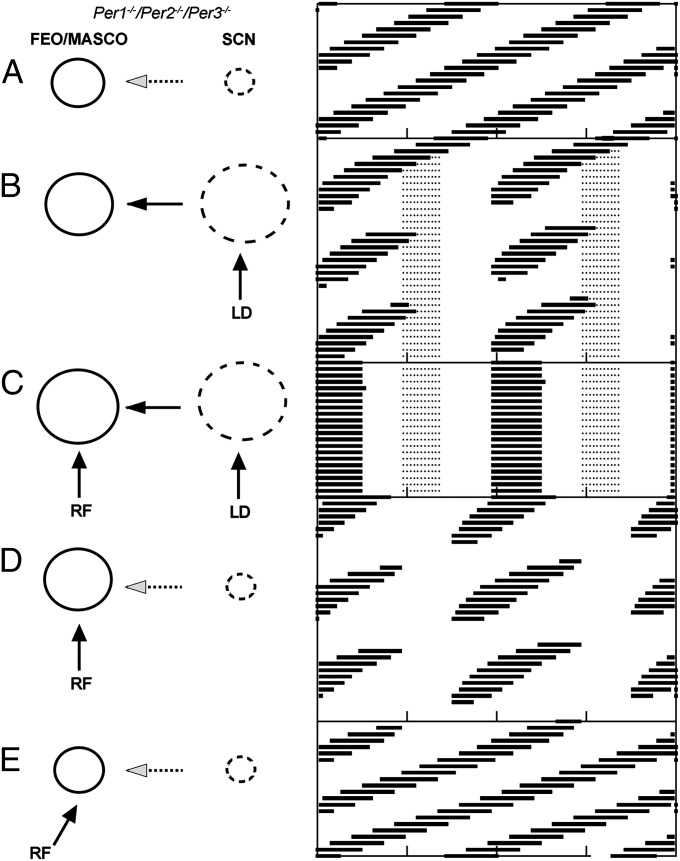

Our experiments showed that the Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− MASCO was coupled to the light-driven SCN oscillator in the light/dark cycle, but free-ran with a short period when the SCN rhythm was dampened in constant darkness. Similarly, the Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− FEO entrained to a 24-h cycle of restricted feeding when the mice were maintained in the light/dark cycle. However, in constant darkness, the Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− FEO entrained to a 21-h cycle, but not a 24-h cycle, of restricted feeding. We next determined if these experimental observations were consistent with a model where the SCN and FEO/MASCO are coupled oscillators with distinct periods. We analyzed the output of a simple mathematical model, where the SCN and FEO/MASCO are limit-cycle oscillators forced by the light/dark cycle or by restricted feeding, respectively. For simplicity, coupling between oscillators was set in only one direction, from the SCN to the FEO/MASCO, disregarding feedback from the latter to the master circadian clock.

Based on our experimental results in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice, the FEO/MASCO was simulated by an oscillator with a free-running period of 21 h, and the SCN was simulated by a damped limit-cycle oscillator. The computer simulation demonstrated that, in constant darkness, the FEO/MASCO free-runs because the SCN oscillator is damped (Fig. 5A). In the presence of the light/dark cycle, however, the damped SCN is passively driven, thus indirectly affecting the dynamics of the FEO/MASCO with a 24-h periodicity (Fig. 5B). When this indirect drive is outside the range of entrainment of the FEO/MASCO, it becomes relatively coordinated.

Fig. 5.

Computational simulations of a model of coupled SCN and MASCO/FEO limit-cycle oscillators with distinct periods. (A–E) The FEO/MASCO (solid circle; indicates self-sustained oscillator) and SCN (dashed circle; indicates damped or passively driven oscillator) are modeled as limit-cycle oscillators (Left) forced by the light/dark cycle (LD) or by restricted feeding (RF), respectively. Relative circle sizes are proportional to oscillator periods and amplitudes. Simulated double-plotted actograms (Right) of the locomotor activity rhythm controlled by the FEO/MASCO (black lines) or SCN (dashed gray lines) in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice are shown for each condition. In the model, the period of the FEO/MASCO is 21 h. In constant darkness (A), the SCN is damped and the FEO/MASCO free-runs with a 21-h period. In the 24-h light/dark cycle (B), the SCN is driven and the FEO/MASCO is in relative coordination. When food is restricted to the daytime on a 24-h cycle in the light/dark cycle (C), the SCN is driven and the FEO/MASCO is entrained. When food is restricted on a 24-h cycle in constant darkness (D), the SCN is damped and the FEO/MASCO is in relative coordination. When food is restricted on a 21-h cycle (deviation from 24-h period indicated by angle of RF arrow) in constant darkness (E), the SCN is damped and the FEO/MASCO is entrained. Parameters: damped oscillator SCN: aL = 0.32, bL = 0.3, cL = 0.8, dL = 0.5; FEO/MASCO: aF = 0.85, bF = 0.52, cF = 0.8, dF = 0.5; coupling CLF = 0.14, CFL = 0. L = 1 (light/dark condition) or L = 0 (constant darkness); Ldur = 1; F = 0.3 (RF) or F = 0 (ad libitum food); Fdur = 1, phase relationship between LD and RF ΦLF = 12 h.

When both 24-h light/dark and 24-h restricted feeding inputs are combined, as when daytime restricted feeding (24-h cycle) is performed in the light/dark cycle, the FEO/MASCO is entrained (Fig. 5C), as this two-zeitgeber system configuration allows stronger entrainment, even when they are in antiphase (19). If, however, 24-h restricted feeding is the only input, as in constant darkness, relative coordination of the FEO/MASCO is observed (Fig. 5D). When the periodicity of restricted feeding (21-h restricted feeding) is approximated to that of the free-running period of the FEO/MASCO (21 h), entrainment of this oscillator is achieved in this complex system.

Discussion

Studies of the FEO and MASCO are challenging because their rhythms are not expressed under normal physiological conditions. Behavioral experiments have demonstrated that both the MASCO and FEO rhythms persist in SCN-lesioned rodents and display the properties of circadian oscillators (reviewed in ref. 4; see also refs. 1 and 2). However, the anatomical loci of these oscillators are unknown (despite exhaustive searches for the FEO; reviewed in ref. 20). Recent studies investigating the FEO and MASCO in circadian mutant mice have raised the possibility that these oscillators do not require canonical circadian genes to maintain their rhythmicities (5–11). In this study, we initially sought to investigate the putative noncanonical nature of the MASCO and FEO, and, surprisingly, found that the canonical Period genes participate in period determination in the MASCO and FEO.

Relative to the FEO, studies of the circadian properties of the MASCO are technically more feasible. The free-running MASCO rhythm is readily expressed within several days of methamphetamine administration. In mice with disrupted canonical circadian genes, the SCN rhythm is disabled by releasing the animals into constant darkness, thus circumventing the need for SCN lesion. Using this approach, we found that the MASCO period in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice is unusually short (21.5 h). All previous studies of wild-type and circadian mutant mice have reported MASCO periods >24 h (3, 6, 7). Thus, Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice are unique in that they have a short-period MASCO rhythm.

In contrast to the MASCO, observing the free-running rhythm of the FEO has been nearly impossible. By definition, a free-running circadian rhythm can only be observed in constant conditions—that is, ad libitum feeding or food deprivation (in SCN-lesioned mice in constant darkness) in the case of the FEO. However, the output of the FEO is not expressed under ad libitum feeding conditions and mice cannot survive more than ∼48 h of food deprivation, thus leading to seemingly insurmountable technical difficulties in measuring the free-running rhythm of the FEO. To our knowledge, only one study has reported the observation of a nonentrained FEO rhythm in one SCN-lesioned rat fed on a 23-h cycle (21). In the current study, we observed the nonentrained FEO rhythm in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice during restricted feeding on a 24-h cycle in constant darkness. Consistent with the simulations of the mathematical model presented herein, we found that when the light-driven SCN rhythm is damped by release into constant darkness, the Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− FEO, which has a 21-h period, cannot entrain to the 24-h cycle of restricted feeding, thus allowing the expression of the free-running (or relatively coordinated) FEO rhythm. This finding represents a pivotal advance in our ability to study the timekeeping properties of the FEO, and this technique can be applied to investigation of other circadian mutants as well as wild-type rodents.

The cyclic input that we refer to as the light-driven SCN rhythm could also be conferred if the light/dark cycle drives rhythmicity in a different brain region (other than the SCN). In this sense, the damped oscillator in the model could be replaced by the light/dark cycle zeitgeber and yield the same results. Therefore, though we believe the SCN is a strong candidate for the anatomical locus receiving light input and driving rhythmic behavior in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice, this is not necessarily the case. However, our conclusions about the MASCO and FEO in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice hold true regardless of whether the SCN or another brain region is receiving light/dark input.

Previous studies of the FEO in mice with disrupted canonical circadian genes have been inconclusive, in part due to the absence of clear data showing that food anticipatory behavior persists during food deprivation (i.e., in constant conditions) in constant darkness (when the SCN rhythm is disabled) (5, 8, 9, 11). The finding that food anticipatory activity in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice entrains to a 21-h cycle of restricted feeding and persists during food deprivation after an intervening day of ad libitum feeding is definitive evidence that the FEO is a circadian oscillator in the absence of all PERIOD. Despite our finding that both the MASCO and FEO are rhythmic in the absence of functional PERIOD, the periods of both oscillators were markedly shortened. These data demonstrate that the canonical Period genes are involved in period determination in the MASCO and FEO.

The MASCO appears to be coupled to the light-driven SCN damped oscillator in light/dark conditions in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice, because the MASCO rhythm did not dissociate from the nocturnal activity rhythm even after long-term (>75 d) methamphetamine treatment in the light/dark cycle (although the MASCO may be relatively coordinated to the SCN). Similarly, our data show that the food anticipatory activity of Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice entrains to a 24-h cycle of restricted feeding in the light/dark cycle, but not in constant darkness, suggesting that the FEO is coupled to the light-driven SCN. These experimental data are consistent with our mathematical model of coupled SCN and FEO/MASCO limit-cycle oscillators, where the SCN oscillator is light-driven, but damps in constant darkness.

Previous studies have suggested that the MASCO and FEO may be the same circadian oscillator (2, 4, 22–24). The current study provides additional evidence supporting this hypothesis. First, the MASCO and FEO in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice have similar and unique short periods. Second, the Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− MASCO and FEO behave distinctly in light/dark and constant darkness conditions, but the distinct outputs are similar between the MASCO and FEO, and are consistent with the computer simulations of the model.

The current study also identifies Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice as an invaluable tool in the search for the anatomical location(s) of the MASCO and FEO. Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice are unique because their FEO and MASCO have distinctive short periods, whereas classical circadian oscillators requiring PERIOD (such as the SCN) are disabled in constant darkness. Thus, the search for the MASCO and FEO can be revitalized by surveying tissues to identify loci with ∼21-h periods of rhythmicity in Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice.

In summary, the work presented here demonstrates that the canonical Period genes are involved in timekeeping in the FEO and MASCO, and we have identified Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice as a tool for solving the enigmas of the MASCO and FEO.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

We obtained mPer1−/−, mPer2−/−, and mPer3−/− mice (congenic with the 129/Sv genetic background, and provided by David Weaver, University of Massachusetts, Worcester, MA) (25, 26) and backcrossed them with wild-type C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory) for at least 15 generations (14, 27) (C57BL/6J Per1−/−, Per2−/−, and Per3−/− mice were deposited at Jackson Laboratory, stock nos. 10491, 10492, and 10493, respectively). Period mutant mice were crossed with each other until we generated several Per1+/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− breeding pairs. Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice used for experiments (males and females) were generated from these breeders. Genotyping for the Period genes was performed as previously described (25, 26). C57BL/6J wild-type mice were from our breeding colony at Vanderbilt University. The wild-type mouse shown in Fig. 1A is a Per2+/+ from our previous study (14). The mice were bred and group housed in the Vanderbilt University animal facility in a 12L:12D cycle [light intensity ∼350 lux (lx)] and provided food and water ad libitum. The mean (± SD) ages of the mice at the beginning of the experiments were as follows: wild type, 93 ± 35 d; Per1+/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/−, 105 ± 39 d). All experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Vanderbilt University (M/08/096).

Recording and Analyses of Circadian Behavior.

Animals were singly housed in cages (length × height × width: 29.5 × 11.5 × 12 cm) with unlimited access to a running wheel (diameter 11 cm), food (unless otherwise indicated), and water. The cages were placed in light-tight, ventilated boxes in light/dark conditions (light intensity: 200–300 lx) or in constant darkness (as indicated for each experiment). Cages were changed every 3 wk. Wheel-running activity (recorded every minute by computer) was monitored and analyzed using ClockLab (Actimetrics). Normalized activity data were double-plotted in actograms in 5-min bins using ClockLab. Periods were determined by χ2 periodogram with α = 0.001 (the days used for analyses are indicated for each experiment). When multiple periods were detected by χ2, fast Fourier transform was used to determine the dominant period.

Methamphetamine Treatment and Analyses.

The mice were provided with 0.005% methamphetamine (Sigma) in their drinking (tap) water. χ2 periodogram analyses were used to determine the periods of the methamphetamine-induced wheel-running rhythms on days 12–33 of methamphetamine treatment (it often took several days for a stable methamphetamine-induced rhythm to be observed). Changes in phases and/or periods of methamphetamine-induced rhythms occurred frequently (both spontaneously and after cage changes), and the days used for χ2 analyses were altered in these instances (as indicated in figures and legends).

Restricted Feeding and Analyses.

Mice were fed LabDiet 5L0D (Purina). Because we previously found that Bmal1−/− mice must be offered food on the bottom of the cage during restricted feeding to prevent death (11), we placed food on the bottom of the cage and in the hopper during restricted feeding of Per1−/−/Per2−/−/Per3−/− mice. Mice were allowed to eat as much as they desired during the time when food was available. When food was removed, the light-tight box was opened and all food was removed from the wire top and from the bottom of the cage. During restricted feeding experiments performed in constant darkness, an infrared viewer (FIND-R-SCOPE Infrared Viewer; FJW Optical Systems, Inc.) was used to add and remove food from cages so that mice were not exposed to visible light. During ad libitum feeding and food deprivation, the light-tight boxes were not opened to avoid any external cues associated with food availability. During this time, the well-being of the mouse was monitored by assessing wheel-running data collected by computer.

Restricted feeding in the light/dark cycle was performed in 18L:6D because we found in our previous studies that food anticipatory activity was more robust in long photoperiods, and we wanted to provide ideal conditions for observing food anticipatory in our current experiments (11). Restricted feeding protocols differed slightly for each experiment (as indicated in figures and legends), but the typical protocol was as follows: After a brief period (5–14 d) of acclimation to the wheel-running cage and light-tight box, mice were food-deprived for 48 h to assess activity during fasting before restricted feeding. Following 1–3 d of ad libitum feeding, mice were food-deprived for 24 h and then fed 6 h/d (Figs. 2 and 3A and Figs. S4 D and E, S5, and S6) or 4 h/d (Fig. 3C and Figs. S4 A–C and S7) for 10 d. After this period of restricted feeding, mice were fed ad libitum for 0–4 d [Fig. 3A and Fig. S5: 2 d ad libitum; Fig. S6: 0 d ad libitum; Fig. 2 and Fig. S4: 3 d ad libitum; Fig. 3C and Fig. S7: 4 d ad libitum; Fig. 4 and Fig. S9: one cycle (21 h) ad libitum] and then food-deprived for 48 h.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaStat (Systat Software, Inc.). Independent t tests (two-tailed) were used to compare two groups. Significance was ascribed at P < 0.05.

Computer Simulations.

SCN and FEO/MASCO oscillators were simulated by coupled Pittendrigh-Pavlidis equations, forced by light/dark (L) or restricted feeding (F), respectively (SI Materials and Methods). In all simulations, L had a 1-h duration and amplitude 1, whereas F had amplitude 0.3 and 1-h duration. A fixed 12-h phase relationship was set between L and F. To attain a damped SCN oscillator, the parameter set values were chosen so as to leave the oscillator out of the self-sustainment domain. Simulations were performed using the CircadianDynamix software (www.neurodynamix.net), which is an extension of Neurodynamix II (28).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. W. Otto Friesen for Neurodynamix software. This research was supported by National Science Foundation Grant IOS-1146908 and the National Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Centers MICROMouse Program U24DK076169 (to S.Y.; www.mmpc.org). Support was also provided by the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System; National Institutes of Health Grant DK085712; and Diabetes Research and Training Center Grant DK20593 (to K.D.N.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1206213109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Honma K, Honma S, Hiroshige T. Disorganization of the rat activity rhythm by chronic treatment with methamphetamine. Physiol Behav. 1986;38:687–695. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honma K, Honma S, Hiroshige T. Activity rhythms in the circadian domain appear in suprachiasmatic nuclei lesioned rats given methamphetamine. Physiol Behav. 1987;40:767–774. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tataroglu O, Davidson AJ, Benvenuto LJ, Menaker M. The methamphetamine-sensitive circadian oscillator (MASCO) in mice. J Biol Rhythms. 2006;21:185–194. doi: 10.1177/0748730406287529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mistlberger RE. Circadian food-anticipatory activity: Formal models and physiological mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1994;18:171–195. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storch KF, Weitz CJ. Daily rhythms of food-anticipatory behavioral activity do not require the known circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6808–6813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902063106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohawk JA, Baer ML, Menaker M. The methamphetamine-sensitive circadian oscillator does not employ canonical clock genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3519–3524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813366106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honma S, Yasuda T, Yasui A, van der Horst GT, Honma K. Circadian behavioral rhythms in Cry1/Cry2 double-deficient mice induced by methamphetamine. J Biol Rhythms. 2008;23:91–94. doi: 10.1177/0748730407311124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitts S, Perone E, Silver R. Food-entrained circadian rhythms are sustained in arrhythmic Clk/Clk mutant mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R57–R67. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00023.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iijima M, et al. Altered food-anticipatory activity rhythm in Cryptochrome-deficient mice. Neurosci Res. 2005;52:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masubuchi S, Honma S, Abe H, Nakamura W, Honma K. Circadian activity rhythm in methamphetamine-treated Clock mutant mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1177–1180. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pendergast JS, et al. Robust food anticipatory activity in BMAL1-deficient mice. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feillet CA, et al. Lack of food anticipation in Per2 mutant mice. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2016–2022. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendoza J, Albrecht U, Challet E. Behavioural food anticipation in clock genes deficient mice: Confirming old phenotypes, describing new phenotypes. Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9:467–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pendergast JS, Friday RC, Yamazaki S. Distinct functions of Period2 and Period3 in the mouse circadian system revealed by in vitro analysis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pendergast JS, Niswender KD, Yamazaki S. Tissue-specific function of Period3 in circadian rhythmicity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honma S, Honma K, Hiroshige T. Methamphetamine effects on rat circadian clock depend on actograph. Physiol Behav. 1991;49:787–795. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90319-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masubuchi S, et al. Clock genes outside the suprachiasmatic nucleus involved in manifestation of locomotor activity rhythm in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4206–4214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuesta M, Aungier J, Morton AJ. The methamphetamine-sensitive circadian oscillator is dysfunctional in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oda GA, Friesen WO. Modeling two-oscillator circadian systems entrained by two environmental cycles. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson AJ. Lesion studies targeting food-anticipatory activity. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1658–1664. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephan FK. Resetting of a feeding-entrainable circadian clock in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1992;52:985–995. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90381-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honma S, Kanematsu N, Honma K. Entrainment of methamphetamine-induced locomotor activity rhythm to feeding cycles in SCN-lesioned rats. Physiol Behav. 1992;52:843–850. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90360-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honma S, Honma K, Hiroshige T. Methamphetamine induced locomotor rhythm entrains to restricted daily feeding in SCN lesioned rats. Physiol Behav. 1989;45:1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90237-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mistlberger RE. Neurobiology of food anticipatory circadian rhythms. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:535–545. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shearman LP, Jin X, Lee C, Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Targeted disruption of the mPer3 gene: Subtle effects on circadian clock function. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6269–6275. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.17.6269-6275.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bae K, et al. Differential functions of mPer1, mPer2, and mPer3 in the SCN circadian clock. Neuron. 2001;30:525–536. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pendergast JS, Friday RC, Yamazaki S. Endogenous rhythms in Period1 mutant suprachiasmatic nuclei in vitro do not represent circadian behavior. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14681–14686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3261-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friesen WO, Friesen JA. Neurodynamix II. Concepts in Neurophysiology Illustrated by Computer Simulations. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.