Abstract

Phosphoinositides (PIs) are lipid components of cell membranes that regulate a wide variety of cellular functions. Here we exploited the blue light-induced dimerization between two plant proteins, cryptochrome 2 (CRY2) and the transcription factor CIBN, to control plasma membrane PI levels rapidly, locally, and reversibly. The inositol 5-phosphatase domain of OCRL (5-ptaseOCRL), which acts on PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3, was fused to the photolyase homology region domain of CRY2, and the CRY2-binding domain, CIBN, was fused to plasma membrane-targeting motifs. Blue-light illumination (458–488 nm) of mammalian cells expressing these constructs resulted in nearly instantaneous recruitment of 5-ptaseOCRL to the plasma membrane, where it caused rapid (within seconds) and reversible (within minutes) dephosphorylation of its targets as revealed by diverse cellular assays: dissociation of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 biosensors, disappearance of endocytic clathrin-coated pits, nearly complete inhibition of KCNQ2/3 channel currents, and loss of membrane ruffling. Focal illumination resulted in local and transient 5-ptaseOCRL recruitment and PI(4,5)P2 dephosphorylation, causing not only local collapse and retraction of the cell edge or process but also compensatory accumulation of the PI(4,5)P2 biosensor and membrane ruffling at the opposite side of the cells. Using the same approach for the recruitment of PI3K, local PI(3,4,5)P3 synthesis and membrane ruffling could be induced, with corresponding loss of ruffling distally to the illuminated region. This technique provides a powerful tool for dissecting with high spatial–temporal kinetics the cellular functions of various PIs and reversibly controlling the functions of downstream effectors of these signaling lipids.

Keywords: endocytosis, polarity, rapamycin, ion channel, ruffles

Phosphoinositides (PIs) are key signaling components of cell membranes that result from the reversible phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol at the 3, 4, and 5 positions of the inositol ring. These reactions give rise to seven PI species that regulate a variety of cell processes including membrane trafficking, cytoskeleton dynamics, cell migration, cytokinesis, and ion and metabolite fluxes across membranes. Their signaling is linked to their different subcellular localization, rapid turnover, and distinct repertoire of binding proteins (1–3). Given these properties, functional interrogation of PI signaling through experimental manipulation requires precise spatial and temporal control.

To date, most studies investigating the role of these lipids have relied on pharmacological or genetic perturbations of the enzymes responsible for PI synthesis and degradation. Small molecules that affect these enzymes have been developed, but, as is the case with all drugs, their off-target effects cannot be excluded. Genetic manipulations (knockout, knockdown, and overexpression studies), as well as studies of patients harboring mutations in such enzymes, have greatly advanced our understanding of the functions of these lipids (2–5). However, these experimental approaches involve long-term changes that can result in compensatory adaptive responses and can cloud a clean interpretation of results. The recently characterized voltage-sensitive inositol 5-phosphatases (5-ptases) are a very powerful tool to deplete PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 rapidly in the plasma membrane but cannot be applied broadly to the study of other PI-metabolizing enzymes and do not allow local regulation within a cell (6, 7).

Methods that use chemicals to induce protein dimerization acutely also have been developed. The FKBP–FRB rapamycin-dependent dimerization system was used to recruit different PI-metabolizing enzymes to specific membranes (8, 9). It thus has helped explore effects of PIs on a variety of parameters such as signal output, endocytosis, ion-channel gating, plasma membrane actin regulation, and endosome maturation (8–13). Although this technique has been instrumental in advancing our understanding of PI signaling, it still has limitations. Dimerization is virtually irreversible on the time-scale of lipid signaling, and it requires a cofactor (rapamycin or a rapalogue) that must penetrate the cell membrane, thus affecting speed of action and limiting its applicability to living organisms. Moreover, drugs cannot be applied with subcellular precision, although the use of caged rapamycin activated by UV has been reported (14).

During the last few years there have been major developments in the field of optogenetics, the methodology that allows noninvasive manipulation of cell function by genetically encoded light-sensitive probes (15). This technique has gained widespread application in the regulation of neuronal function via light-regulated ion channels. In addition, light-controlled dimerization systems have been introduced that promise to have a major impact in cell biology, including the regulation of phospholipid metabolism (16) and manipulations of cell function at subcellular resolution (17, 18). There are several variants of the technology (19, 20). One is based on two plant proteins, cryptochrome 2 (CRY2) and the transcription factor CIB1, that together control expression of genes regulating floral initiation. Upon blue-light illumination, a FAD molecule bound to the photolyase homology region (PHR) of CRY2 (CRY2PHR) absorbs a photon, causing a conformational change in this domain that promotes binding to the N-terminal portion of CIB1 (CIBN) (Fig. 1A) (21). In this study we exploited the light-inducible interaction of these two domains for the acute manipulation of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 in the plasma membrane via the recruitment of 5-ptases or PI3-kinase. We show that this system produces a nearly instantaneous and reversible change in the levels of the two PIs with subcellular spatial control. When used with focal illumination, it had a robust impact on cell polarity, caused not only by perturbations of the local plasma membrane but also by compensatory changes at other regions of the cell surface.

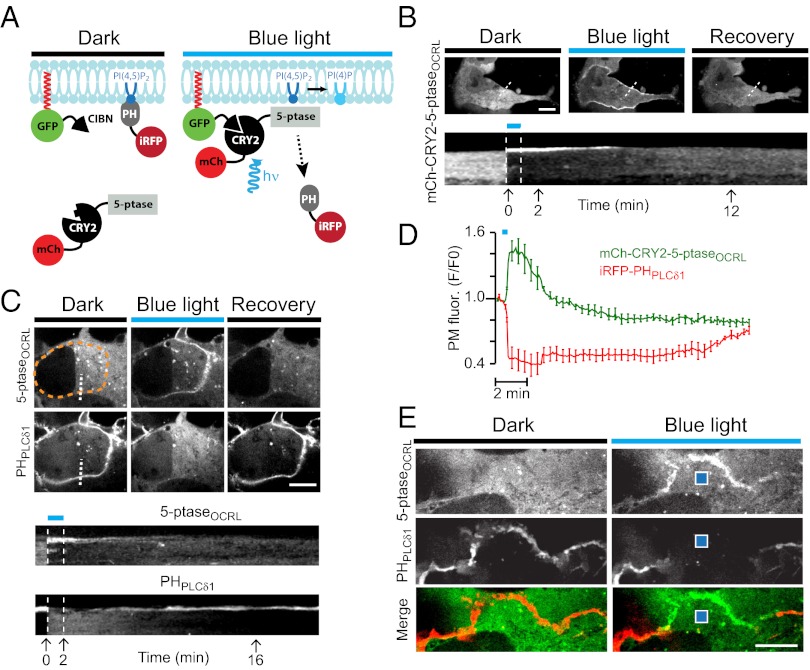

Fig. 1.

Rapid PI(4,5)P2 dephosphorylation produced by blue light-induced recruitment of a 5-ptase to the plasma membrane of COS-7 cells. (A) Schematic drawing depicting constructs used to induce and detect PI(4,5)P2 dephosphorylation. (B) (Upper) Confocal micrographs showing the localization of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL before, during, and 10 min after illumination with 20 × 300-ms blue-light pulses. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (Lower) Kymograph drawn along the dashed white line in the upper panel illustrating the nearly instantaneous (within seconds) plasma membrane recruitment of the 5-ptase. Pictures in the upper row are from the time-points indicated below the kymograph. (C) (Upper) Confocal micrographs showing the localization of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL and iRFP-PHPLCδ1 before, during, and 16 min after blue-light illumination. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (Lower) Kymographs drawn along the dashed white lines in the fields shown in the upper panel. Pictures in the upper row are from the time-points indicated below the kymograph. (D) Dynamics of plasma membrane-associated fluorescence for mCh-CRY2PHR-5paseOCRL (green) and iRFP-PHPLCδ1 (red) before, during, and after blue-light illumination (n = 12 cells). (E) Confocal micrographs of the peripheral region of a cell expressing both mCh-CRY2-5paseOCRL (green) and iRFP-PHPLCδ1 (red) before and 10 s after a single 100-ms blue-light pulse delivered locally (blue square). Note that the effect of illumination occurs only in the adjacent plasma membrane region. (Scale bar: 5 μm.)

Results and Discussion

Blue Light-Induced Recruitment of a 5-Ptase Dephosphorylates PI(4,5)P2 in the Plasma Membrane.

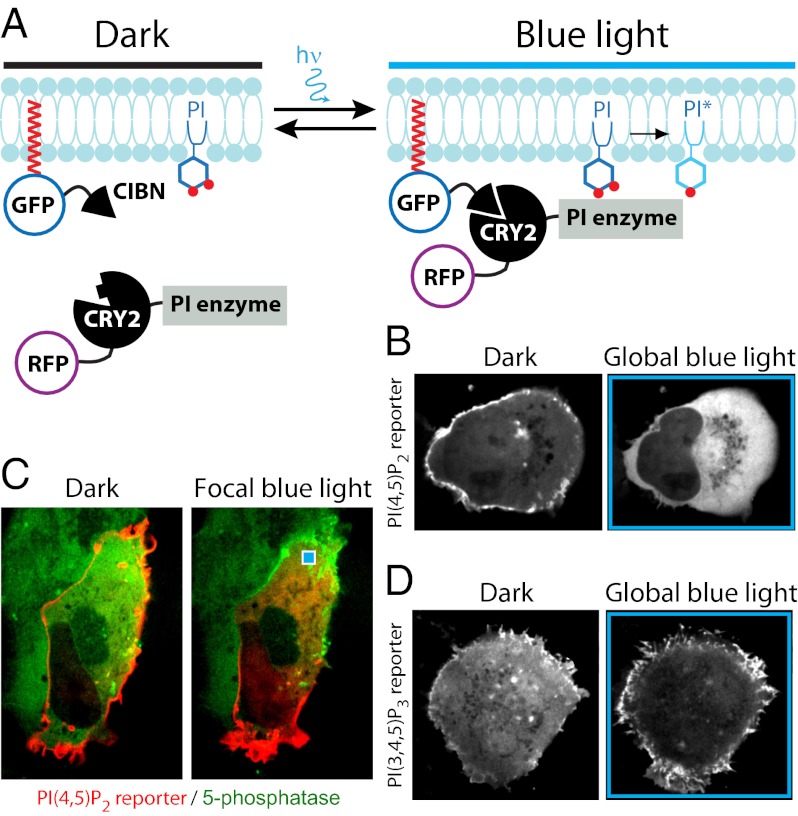

The CRY2–CIBN dimerization system was used to recruit phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphatase modules [i.e., modules that dephosphorylate the 5-position of the inositol ring of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3] to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1A). mCherry-tagged constructs comprising CRY2PHR fused to 5-ptase modules of OCRL or INPP5E (22, 23) (mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL and mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseINPP5E, respectively) were coexpressed in COS-7 cells with a CIBN-GFP fusion protein comprising a C-terminal CAAX box for plasma-membrane targeting (CIBN-GFP-CAAX). Global cell illumination and fluorescence confocal microscopy revealed that exposure of cells to a train of 20 × 300-ms blue-light pulses (488 nm, except for electrophysiology experiments; see below) resulted in a rapid recruitment of both 5-ptases to the plasma membrane (t1/2 = 2.8 ± 0.8 s for 5-ptaseINPP5E and t1/2 = 3.0 ± 0.7 s for 5-ptaseOCRL) and that this recruitment was reversible upon interruption of the illumination (t1/2 of recovery = 3.6 ± 0.5 min for 5-ptaseINPP5E and 3.8 ± 0.6 min for 5-ptaseOCRL). Both 5-ptase modules were recruited efficiently to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1A). However, because the 5-ptase module of OCRL was more potent in depleting PI(4,5)P2 (see below), subsequent experiments (except when indicated) were performed with OCRL.

Coexpression of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL with the near-infrared PI(4,5)P2 biosensor iRFP-PHPLCδ1 (24, 25) made possible simultaneous blue-light illumination and dual-color imaging, allowing us to show that 5-ptase recruitment correlated with the rapid (t1/2 = 3.1 ± 0.2 s, n = 32) and reversible (t1/2 = 6.8 ± 1 min) displacement of the biosensor from the plasma membrane. Such displacement peaked even before the peak of 5-ptase recruitment (Fig. 1 C and D and Movie S1). Notably the depletion of PI(4,5)P2 from the plasma membrane had no effect on the association of the CIBN fusion protein with the plasma membrane (Fig. S2E). The changes in the localization of the 5-ptase recovered within minutes, consistent with the reported time constant of the dissociation of CRY2 and CIBN (21). The recovery of PI(4,5)P2 lagged slightly because of the additional time required for its resynthesis after dissociation of the highly active 5-ptase from the plasma membrane (Fig. 1D).

Besides offering the advantage of reversibility, the time-course of PI(4,5)P2 dephosphorylation afforded by the CRY2–CIBN dimerization system is more than an order of magnitude faster than that of the rapamycin-dependent dimerization system (8). In addition, this system offers the possibility of recruiting the 5-ptase locally within a cell. When a single 100-ms blue-light pulse was delivered to a 4-μm2 spot (i.e., the small volume of cytoplasm underlying this spot) near the cell edge, robust mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL recruitment occurred only in the directly adjacent plasma membrane region, with corresponding displacement of iRFP-PHPLCδ1 (Fig. 1E and Movie S2).

Selective PI(4,5)P2 Dephosphorylation in the Ventral Cell Membrane.

Efficient local recruitment of the phosphatase near an illuminated cytoplasmic region could be achieved by combining the CRY2–CIBN system with total internal reflection fluorescent microscopy (TIRFM). TIRFM illumination minimizes fluorophore bleaching and phototoxicity and allows direct quantification of changes in plasma membrane fluorescence (26). Although such illumination selectively activates only the small fraction of cytosolic CRY2 fusion protein within the evanescent field (i.e., the “ventral” cell region closely apposed to the cell substrate), it still was efficient in promoting the association of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL with the nearby plasma membrane (Fig. 2 A and B and Movie S3). A key difference between global illumination (by either confocal or epifluorescence microscopy) and TIRFM illumination was that maximal recruitment of the 5-ptase with TIRFM required longer blue-light exposure to allow a sufficient number of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL molecules to diffuse through the evanescent field. A direct comparison of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL recruitment to the ventral plasma membrane after evanescent wave or global (epifluorescence) illumination is shown in Fig. S1 B–D. Further experiments were performed with a train of light pulses (>20) eliciting maximal plasma membrane translocation.

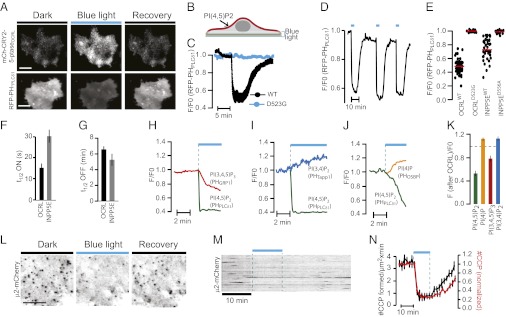

Fig. 2.

PI changes produced by blue light-induced 5-ptase recruitment to the plasma membrane and arrest of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Both illumination and image recording of COS-7 cells were carried out by TIRFM. (A) Images of cells expressing mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL (Upper) and RFP-PHPLCδ1 (Lower) before, during, and 10 min after exposure to a train of 30 × 300-ms blue-light pulses delivered through the evanescent field. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (B) Schematic drawing illustrating blue-light delivery through TIRF illumination and selective dephosphorylation of PI(4,5)P2 on the ventral cell membrane. (C) TIRFM recordings of plasma membrane RFP-PHPLCδ1 fluorescence following blue-light exposure of cells coexpressing CIBN-CAAX and CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL (black) or catalytically inactive CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL(D523G) (blue). Data are presented as means ± SEM for 44 WT and 17 D523G cells. (D) TIRFM recording of plasma membrane RFP-PHPLCδ1 fluorescence of a cell subjected to three 30 × 200-ms sequential illumination pulse trains showing reproducible PI(4,5)P2 dephosphorylation. (E) Scatterplot showing the drop in plasma membrane RFP-PHPLCδ1 fluorescence from cells coexpressing CIBN-CAAX and CRY2-5-ptaseINPP5E, CRY2-5-ptaseINPP5E(D556A), CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL, or CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL(D523G) (n = 16–40 cells). (F) The t1/2 for RFP-PHPLCδ1 plasma membrane dissociation following recruitment of CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL or CRY2-5-ptaseINPP5E (n = 32 and 28 cells, respectively). (G) The t1/2 for RFP-PHPLCδ1 reassociation with the plasma membrane (n = 32 and 28 cells). (H–J) Dual-color TIRFM recordings from single cells expressing CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL, CIBN-CAAX, and pairs of fluorescent proteins as indicated during exposure to 30 × 200-ms blue-light pulses. Note that data points for GFP imaging were collected only during blue-light illumination. (K) Average change in plasma membrane fluorescence for the data presented in H–J (n = 8–40 cells). (L–N) TIRFM analysis of cells expressing CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL, CIBN-CAAX, and μ2-mCherry before, during, and after exposure to a 10-min train (200 ms, 5-s interpulse intervals) of blue-light pulses. (L) μ2-mCherry fluorescence reflecting individual clathrin-coated pits (fluorescence is shown in black for clarity) in a small cell region before, during, and 20 min after the illumination. (Scale bar: 3 μm.) (M) Representative kymograph. (N) Average number (± SEM) of μ2-mCherry spots (red) and newly formed spots (black) (n = 6 cells).

Recruitment of the 5-ptase by a train of 30 × 300-ms pulses via the evanescent field produced rapid (t1/2 = 20 ± 2 s, n = 32) dissociation of cotransfected RFP-PHPLCδ1from the ventral plasma membrane, demonstrating PI(4,5)P2 5-dephosphorylation. RFP-PHPLCδ1 dissociation was reversed completely within 10 min (Fig. 2 A–C), and repetitive trains delivered after recovery of RFP-PHPLCδ1 elicited identical responses (Fig. 2D). When the wild-type catalytic module was replaced by a catalytically inactive mutant (Fig. 2C), there was no displacement of RFP-PHPLCδ1 from the plasma membrane, confirming that the catalytic action of the 5-ptase is responsible for PI(4,5)P2 5-dephosphorylation. The specificity of the 5-ptase reaction was assessed further with biosensors for the other plasma membrane substrate for this module, PI(3,4,5)P3, and for the products of its catalytic action, PI(4)P and PI(3,4)P2. Dual-wavelength recordings showed that plasma membrane recruitment of 5-ptaseORCL was associated not only with loss of plasma membrane fluorescence for PI(4,5)P2 reporters (GFP- or RFP-PHPLCδ1) but also with loss of fluorescence for a PI(3,4,5)P3 reporter (mCherry-PHGRP1) and with an increase in plasma membrane fluorescence for a PI(4)P reporter (GFP-PHOSBP) and a PI(3,4)P2 reporter (mRFP-PHTapp1) (Fig. 2 H–K) (27–29).

The loss of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 from the ventral plasma membrane was validated further by the arrest of endocytic clathrin-coated pit formation. TIRFM of COS-7 cells expressing the mCherry-tagged μ2-subunit of the clathrin adaptor AP2 (μ2-mCherry) revealed the typical appearance and disappearance of fluorescent spots (Movie S4) reflecting the nucleation, growth, and fission of clathrin-coated pits. Blue light-induced recruitment of 5-ptaseOCRL to the plasma membrane resulted in rapid (within 2 min) and dramatic (80%) loss of μ2-mCherry spots (Fig. 2 L–N). The few remaining μ2-mCherry spots became less fluorescent and static. As cells were allowed to recover in the absence of blue light, dynamic μ2-mCherry spots reappeared within 10 min, consistent with the recovery time of PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 2C and Movie S1). Similar results were obtained in cells expressing mRFP-tagged clathrin light chain (CLC-mRFP) (Fig. S3 A and B).

Comparison of Dimerization Components.

TIRFM was used to compare the efficiency of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseINPP5E relative to mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL in dephosphorylating PI(4,5)P2. Although the dynamics of the recruitment and release of these two modules at the plasma membrane were nearly identical (Fig S1A), 5-ptaseINPP5E was about 50% less efficient and half as fast as 5-ptaseOCRL in displacing RFP-PHPLCδ1 from the plasma membrane (Fig. 2 E and F). Whether the difference reflects the intrinsic catalytic activities of the two phosphatase modules or a better presentation of 5paseOCRL in the context of our dimerization system is an open question. The recovery of PI(4,5)P2 upon interruption of blue-light illumination, which reflects primarily dissociation of the CRY2–CIBN dimer, was similar for the two phosphatases (t1/2 = 6.4 ± 0.3 for CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL and 5.5 ± 0.6 min for CRY2-5-ptaseINPP5E) (Fig. 2G).

The properties of different plasma membrane-anchoring motifs as plasma membrane localized “baits” for recruiting CRY2-5-ptases were compared also. CIBN-GFP-CAAX was compared with three other constructs in which the CIBN-GFP modules were (i) N-terminally tagged with the 11 N-terminal amino acid residues of Lyn kinase (which undergo myristoylation and palmitoylation), (ii) N-terminally tagged with the 10 N-terminal residues from Lck (which undergo myristoylation and 2× palmitoylation), or (iii) C-terminally tagged with the transmembrane domain of human Syntaxin1A. These three fusion proteins localized to the plasma membrane, and blue-light illumination caused translocation of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL to this membrane in these cells (Fig. S2 A and B). Although the kinetics of translocation was comparable to those seen in cells expressing CIBN-GFP-CAAX, the magnitude of the translocation was lower (Fig. S2B). Nevertheless, recruitment of CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL by all baits resulted in similar displacement of RFP-PHPLCδ1, suggesting that the amount of 5-ptase recruited is not rate limiting in dephosphorylating PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. S2 C and D).

We attempted to target the CRY2PHR modules, rather than CIBN modules, to the plasma membrane via a lipid anchor and to fuse the 5-ptase to the CIBN module. Such a method would allow induction of dimerization with a more precise level of subcellular resolution because the light-sensitive component would be tethered to the membrane rather than free in the cytosol. However, the constructs that we generated were found to dimerize much less efficiently, possibly because of steric hindrance, and they were not studied further.

Blue Light-Induced Inhibition of KCNQ2/3 Channel Current.

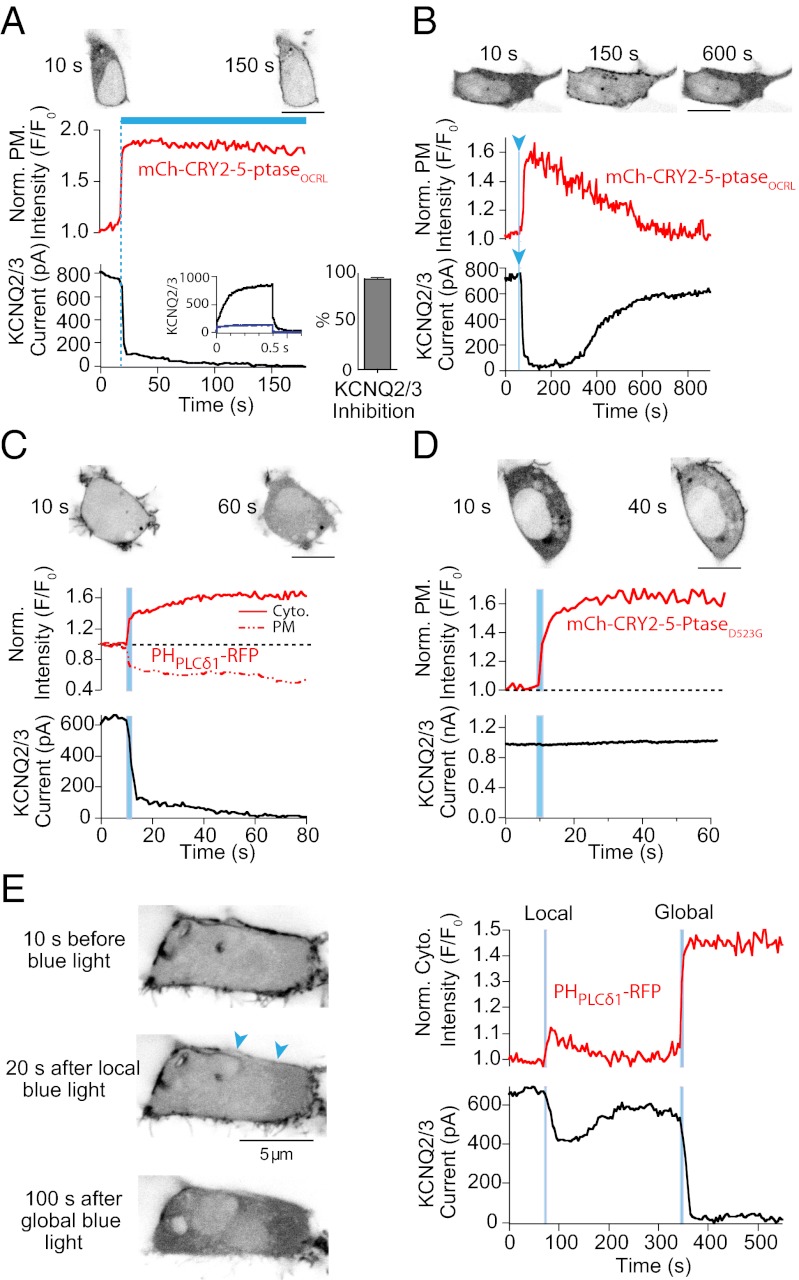

To assess the effect of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL recruitment on PI(4,5)P2 dephosphorylation with maximal temporal resolution, whole-cell currents in KCNQ2/3 (KV7.2/7.3) channels were measured simultaneously with confocal imaging. KCNQ2/3 channels need PI(4,5)P2 as a positive cofactor to remain open, and depletion of PI(4,5)P2 results in channel closure (8, 9). Illuminating tsA-201 cells with sustained blue light (458 nm) resulted in rapid recruitment of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL to the plasma membrane and nearly immediate (t1/2 = 1.2 ± 0.3 s; n = 9) and complete (95%) inhibition of KCNQ2/3 currents that persisted throughout the illumination period (Fig. 3A). The reversibility of the blue light-mediated CRY2–CIBN interaction is highlighted again by the recovery of KCNQ2/3 currents (t1/2 = 286 ± 33 s; n = 5) nearly to control levels following a brief (1-s) pulse of blue light (Fig. 3B). Coexpression of KCNQ2/3 channels with CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL and the PI(4,5)P2 biosensor RFP-PHPLCδ1 permits simultaneous monitoring of PI(4,5)P2 by two different methods. The rapid displacement of the PI(4,5)P2 biosensor from the plasma membrane and the precipitous fall in KCNQ2/3 currents were synchronous (Fig. 3C). The reduction of KCNQ2/3 currents occurs before maximal recruitment of the 5-ptase, again indicating that more enzyme is expressed than is needed for strong PI(4,5)P2 depletion. Recruitment of the catalytically inactive mutant to the plasma membrane resulted in no change in either RFP-PHPLCδ1 fluorescence intensity or KCNQ2/3 currents (Fig. 3D), confirming that neither blue light alone nor any cellular change that occurs as a result of recruitment is responsible for loss of PI(4,5)P2.

Fig. 3.

Blue light-induced recruitment of a 5-phosphatase to the plasma membrane rapidly decreases KCNQ2/3 current. (A) (Top) Confocal micrographs show subcellular distribution of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL 10 s before and 150 s after blue-light illumination. Simultaneous measurement of normalized mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL fluorescence intensity at the plasma membrane (Middle) and whole-cell KCNQ2/3 currents (Bottom) from a tsA-201 cell following sustained, global illumination of the cell with 458-nm blue light. Fluorescence intensity was normalized to initial intensity (F/F0). (Inset) KCNQ2/3 current traces before (black) and after (blue) illumination. The histogram summarizes the percentage inhibition of KCNQ2/3 currents following mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL recruitment (n = 9). (B) (Top) Confocal micrographs show subcellular distribution of mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL 10 s before and 150 s and 600 s after blue-light illumination. Simultaneous confocal measurement of normalized mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL fluorescence intensity at the plasma membrane (Middle) and KCNQ2/3 currents (Bottom) following a 1-s blue-light pulse. (C) (Top) Confocal micrographs show subcellular distribution of PHPLCδ1-RFP 10 s before and 60 s after blue-light illumination. (Middle) Confocal time series measurements of normalized PHPLCδ1-RFP fluorescence intensity in the cytoplasm (solid red line) and plasma membrane (dashed red line) following recruitment of CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL with a 1-s pulse of blue light. (Bottom) Whole-cell KCNQ2/3 current recordings in response to the same stimulus. (D) (Top) Confocal micrographs show subcellular distribution of PHPLCδ1-RFP 10 s before and 40 s after blue-light illumination. Measurement of fluorescence intensity of PHPLCδ1-RFP (Middle) at the plasma membrane and whole-cell KCNQ2/3 current (Bottom) following the recruitment of CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL(D523G) with a 2-s pulse of blue light. (E) (Left) Confocal micrographs of a tsA-201 cell expressing CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL, CIBN-CAAX, KCNQ2/3, and PHPLCδ1-RFP 10 s before, 20 s after local (area of local stimulation = 2 × 5 μm; blue arrowheads), and 100 s after global illumination of the cell with blue light. (Right) Concurrent monitoring of normalized cytoplasmic PHPLCδ1-RFP fluorescence intensity (Upper) and KCNQ current (Lower) following local and global illumination with blue light.

As described, a great advantage of the CIBN–CRY2 system over chemical dimerization is the ability to recruit the 5-ptase to the plasma membrane in a spatially defined manner. When a single 1-s pulse of blue light was delivered to a 5 × 2 μm spot near the cell edge, CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL was recruited to and dephosphorylated PI(4,5)P2 only in the proximity of the illuminated region (Fig. 3E). This local perturbation in PI(4,5)P2 led to a partial decrease in whole-cell KCNQ2/3 currents. After recovery, global illumination with blue light resulted in a larger decrease of KCNQ2/3 currents and a larger increase in cytoplasmic RFP-PHPLCδ1 fluorescence.

Acute Local Perturbation of Actin Nucleation by Focal Blue-Light Illumination.

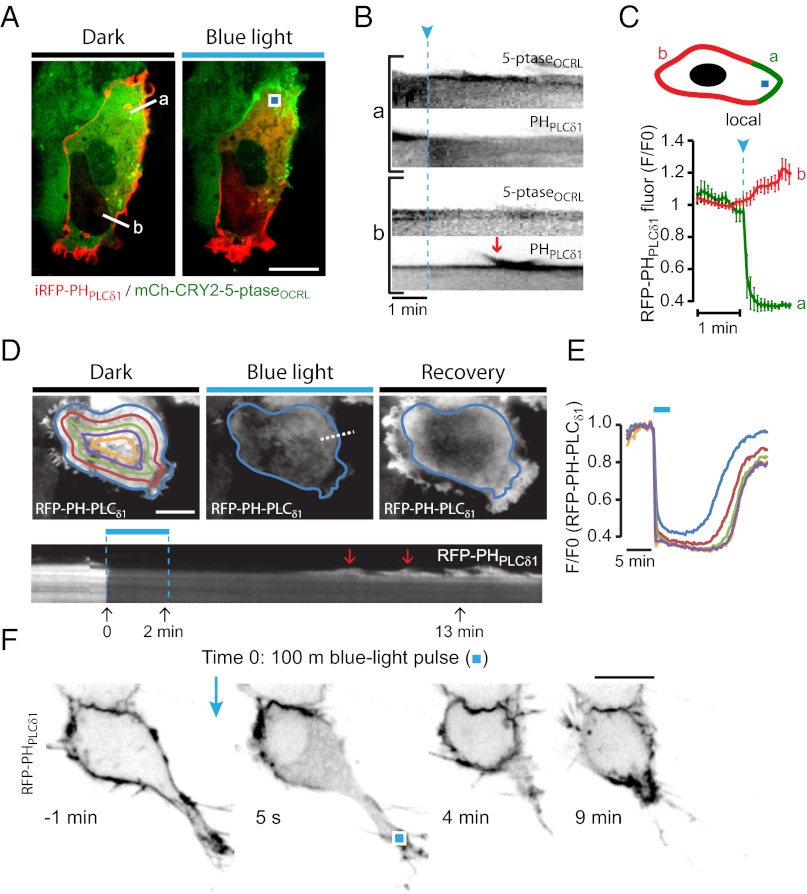

Consistent with the role of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 in the nucleation of actin at the plasma membrane (30), global recruitment of 5-ptaseOCRL resulted in the loss of peripheral actin, decreased membrane ruffling, and retraction of the cell edges (Fig. S3 C–E). Thus, we explored the use of the mCh-CRY2–CIBN 5-ptase system to induce local perturbations of the actin cytoskeleton and changes in cell polarity. As shown by confocal microscopy, when a single 100-ms blue-light pulse was delivered to an ∼4-μm2 region of COS-7 cells expressing CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL and iRFP-PHPLCδ1, the rapid and selective loss of iRFP-PHPLCδ1 from the adjacent plasma membrane region was accompanied by local loss of ruffling and cell retraction. Interestingly, these local perturbations correlated with increased ruffling and increased plasma membrane association of iRFP-PHPLCδ1 at the opposite pole of the cell. This phenomenon is illustrated by individual images (Fig. 4 A and B and Movie S5) and by a quantification of the redistribution of the RFP-PHPLCδ1 fluorescence obtained from the analysis of 10 cells (Fig. 4C). The changes at sites distant from the illuminated area may reflect increased availability of the PI(4,5)P2 probe and of actin and actin-nucleating proteins as they dissociate from the illuminated side. A compensatory increase in PI(4,5)P2 levels also could occur through the redistribution of PI kinases and phosphatases. Gradients of PIs generated by asymmetric distribution of kinases and phosphatases, with an impact on cell polarity, have been described in polarized epithelial cells (30) and in Dictyostelium discoideum (31), where the concentration of PI3-kinase and of PTEN at opposite poles of the cell generate a PI(3,4,5)P3 gradient. Such gradients develop rapidly, within seconds, similar to the ones we describe here.

Fig. 4.

Local perturbation of actin dynamics induced by focal blue light-dependent recruitment of a 5-ptase. (A) Confocal micrographs of a COS-7 cell expressing mCh-CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL (green), CIBN-CAAX, and iRFP-PHPLCδ1 (red) before and 10 s after exposure to a single, locally delivered 100-ms blue-light pulse (blue square). (B) Kymographs drawn along the two white lines in A, either close to (a) or far from (b) the site of focal blue-light illumination. The red arrow indicates a peripheral ruffle. (C) Quantification of the change in plasma membrane RFP-PHPLCδ1 fluorescence close to (green) or far from (red) the site of focal blue-light illumination as shown in the drawing. Data shown are from 10 cells (means ± SEM). (D and E) TIRFM analysis of a COS-7 cell expressing CIBN-CAAX, CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL, and RFP-PHPLCδ1 before, during, and after exposure to a train (30 × 200 ms) of blue-light pulses delivered through the evanescent field. (D) TIRFM images (Upper) and kymograph drawn along the white dotted line (Lower). Note the appearance of RFP-PHPLCδ1–positive ruffles during the recovery phase (red arrows). At time point 2 min there is a change in the position of the cell causing a downward shift in the kymograph of approximately 1 μm. (E) TIRFM recordings of RFP-PHPLCδ1 fluorescence (average of eight cells). Lines represent fluorescence change for the corresponding color-coded areas in D, Left. (F) Confocal micrographs of RFP-PHPLCδ1 fluorescence in a PC-12 cell coexpressing CRY2-5-ptaseOCRL and CIBN-CAAX before and after exposure to a locally delivered 100-ms blue-light pulse (blue square). Black-and-white signal has been inverted for clarity. (Scale bars: 10 μm.)

The adaptive response produced by a localized depletion of PI(4,5)P2 was illustrated in a subset of cells in which PI(4,5)P2 was depleted selectively on the ventral plasma membrane via a train of blue-light pulses delivered through the evanescent field. Surprisingly, upon interruption of the illumination, the recovery of RFP-PHPLCδ1 fluorescence on the ventral plasma membrane, which proceeded in a centripetal direction, was associated with a pronounced ruffling at the cell periphery that greatly exceeded the preillumination ruffling and resulted in an extension of the cell edges (Fig. 4 D and E and Movies S6 and S7).

A striking example of the impact of PI(4,5)P2 dephosphorylation on cell polarity was provided by the effect of local PI(4,5)P2 depletion on the tip of a PC12 cell process. A single 100-ms blue-light pulse induced loss of PI(4,5)P2, resulting in a dramatic retraction of the process (Fig. 4F and Movie S8).

Global and Local PI(3,4,5)P3 Synthesis In Response to Light-Dependent PI3-Kinase Recruitment.

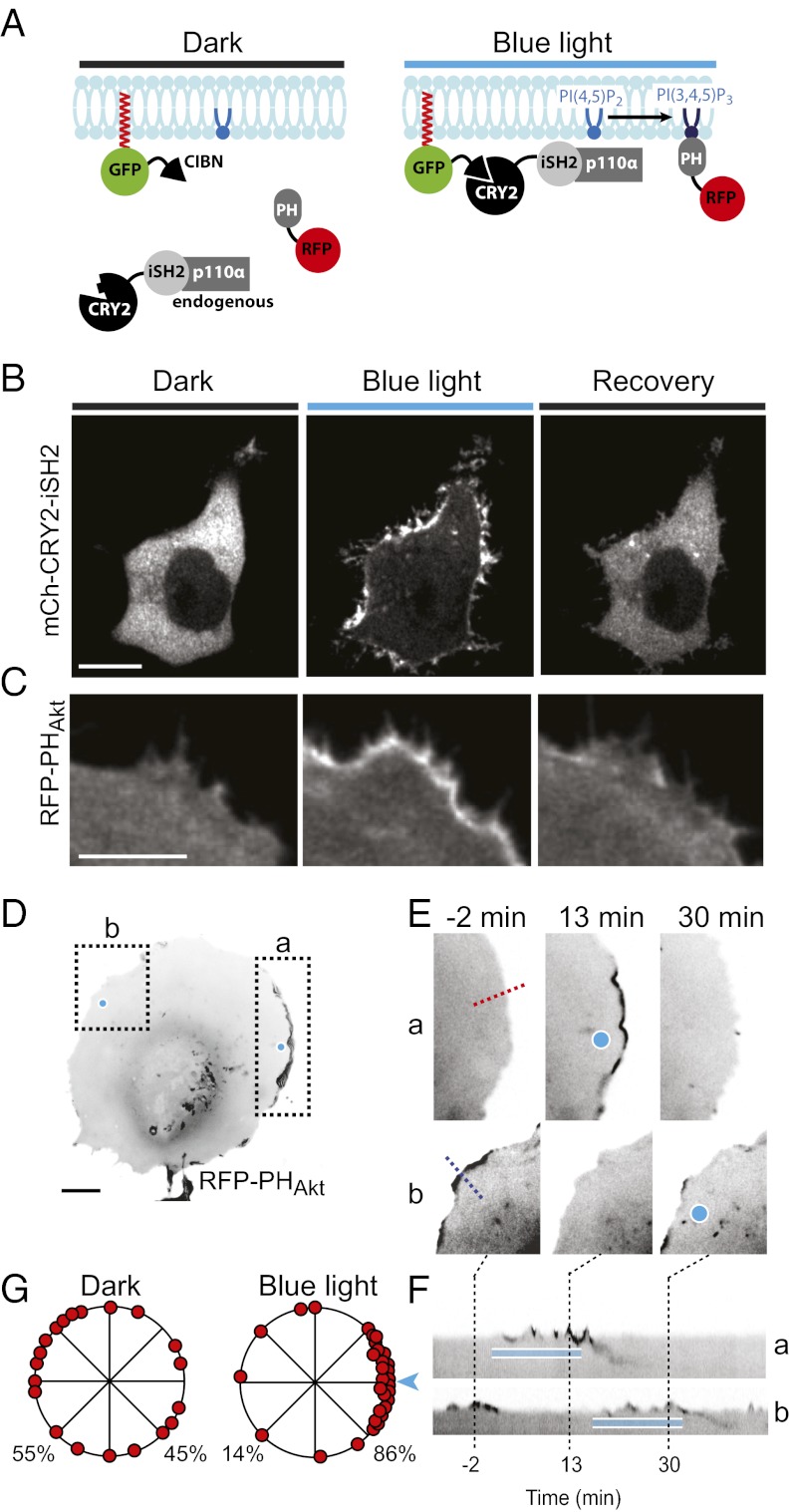

Next, we assessed the potential of the CRY2–CIBN system to generate PI(3,4,5)P3 at the plasma membrane. A “light-inducible” PI3-kinase was generated using the strategy used previously for the nonreversible rapamycin heterodimerization system (8), i.e., by fusing the inter-SH2 (iSH2) region of the p85α regulatory subunit of class I PI3-kinases to the C terminus of mCh-CRY2. iSH2 binds endogenous PI3-kinase p110α catalytic subunits constitutively, so that upon blue-light illumination the subunits are recruited along with the iSH2 region to the plasma membrane (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Global and local membrane ruffling produced by light-induced PI(3,4,5)P3 synthesis. (A) Schematic drawing depicting constructs used to induce blue light-mediated plasma membrane recruitment of the endogenous catalytic p110α-subunit of PI3-kinase using the iSH2 region of the regulatory p85α-subunit as bait. (B) Confocal micrographs of a COS-7 cell expressing CIBN-CAAX and mCh-CRY2-iSH2. Images were taken before, during, and 10 min after the cells were exposed to a 5-min train (60 × 200 ms) of blue-light pulses. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (C) Confocal micrographs showing a portion of a COS-7 cell expressing CIBN-CAAX, CRY2-iSH2, and RFP-PHAkt before, during, and 10 min after cell-wide blue-light illumination. (Scale bar: 5 μm.) (D) Confocal micrograph of a COS-7 cell expressing CIBN-CAAX, CRY2-iSH2, and RFP-PHAkt (RFP signal is shown in black). (Scale bar: 10 μm.) The cell was subjected to sequential focal illumination at two opposite sites as indicated by small blue circles. (E) Magnifications of the two boxed areas in D (a and b) at the times indicated. (F) Kymographs drawn along the blue and red lines in E. (G) Diagrams showing the distribution of RFP-PHAkt–positive membrane ruffles in the absence or presence of focal blue-light illumination at the site indicated. Data shown are pooled from five cells.

Confocal microscopy imaging of serum-starved COS-7 cells coexpressing mCh-CRY2-iSH2 and the membrane-targeting component CIBN-GFP-CAAX showed rapid (t1/2 = 14 ± 2 s, n = 12 cells) plasma membrane translocation of mCh-CRY2-iSH2 upon global blue-light illumination. Translocation was associated with pronounced membrane ruffling (Fig. 5B and Movie S9), as expected given the powerful stimulating activity of PI(3,4,5)P3 on Rac activation and thus on Rac effectors that control actin nucleation (32, 33). Coexpression of CIBN-GFP-CAAX and a nonfluorescent iSH2 (CRY2-iSH2) along with the PI(3,4,5)P3 reporter RFP-PHAkt showed redistribution of RFP-PHAkt from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane upon blue-light illumination, confirming PI(3,4,5)P3 generation in this membrane (Fig. 5C). Such redistribution was reversed by allowing the cells to recover in the absence of blue light or by the addition of the PI3-kinase inhibitors wortmannin (0.5 μM) or LY294002 (50 μM) (Fig. 5C and Fig. S4). Local illumination of the same cells produced local PI(3,4,5)P3 elevation and ruffling with reciprocal loss of membrane ruffles in other parts of the cell, thus inducing cell polarity (Fig. 5 D–G and Movie S10).

Concluding Remarks

Chemically dependent dimerization methods for the acute recruitment of catalytic modules to control PI metabolism on specific membranes have been used successfully in numerous studies (8–13). The light-dependent system described here offers several advantages over chemical dimerization for the control of PI levels. (i) It produces at least an order of magnitude faster response. (ii) It is reversible, with a t1/2 of minutes. (iii) It avoids potential off-target effects of the drug. (iv) It allows the independent study of multiple cells in a cohort of cells. (v) It allows spatial control of dimerization, and hence of PI regulation, with high subcellular precision. (vi) It can, in principle, be applied to tissues of an intact organism, as in the case of widely used optogenetic methods involving light-sensitive channels, thus overcoming problems related to systemic drug administration and permeability barriers.

A disadvantage of light-dependent dimerization, which may limit some applications and in particular applications to living organisms, is that cells and tissues expressing the two components of the system must be protected from green/blue light until the time of the experiment. Other optogenetic systems work in the far red portion of the spectrum but require cofactors (19, 20). An additional drawback of the system is that it precludes the use of green or blue light-emitting fluorescent proteins, thereby limiting multiparametric imaging of effects induced by the dimerization in living cells. However, as we have shown here, the recent introduction of near-infrared fluorescent proteins allows two-color imaging before and during blue-light illumination (Fig. 1C).

Reversibility and the possibility of achieving local cell modifications are particularly strong advantages of light-dependent dimerization. Reversibility allows for internal controls in a variety of experimental paradigms. Local control, as previously demonstrated in the case of Rac activation (17, 18), makes the system suitable for studying mechanisms regulating cell polarity and directed cell growth, because these processes have been shown to be heavily dependent on PI gradients (34–36). We found that focal recruitment of PI-metabolizing enzymes rapidly causes lipid gradients resulting in cell polarization, driven not only by the spatially restricted changes at sites of illumination but also by compensatory reactions in distal regions. Because local changes in lipid levels are expected to occur physiologically, as the cell interfaces with the heterogeneous local environment, the technique described here allows the study of cellular responses to spatially localized signals. Importantly, local control allows selective manipulation of distinct compartments of large cells, such as dendrites and axons of neurons. The impact of the activation of an inositol 5-phosphatase at the tip of a growing neurite of a PC12 cell (Fig. 4F) provides a striking example of the potential of this technique to study the role of PIs in neurite navigation.

In conclusion, the system described here allows unprecedented spatial and temporal control of plasma membrane PIs within single cells. This method can be modified by targeting different PI metabolizing enzymes to various cellular membranes. It will allow further detailed dissection of the function of various PIs and will permit reversible perturbation of cellular processes downstream of these signaling lipids.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Reagents.

CRY2-mCherry and CIBN-GFP-CAAX were kind gifts from Chandra Tucker (University of Colorado Denver, Denver, CO) (21). Blue light-recruitable 5-phosphatases were generated by fusing the catalytic domains of human INPP5E (residues 214–644) and OCRL (234–539) to the C terminus of mCherry-CRY2. The light-inducible PI3-kinase was generated by fusing the iSH2 domain of human p85α (residues 420–615) to the C terminus of mCherry-CRY2. The near-infrared PI(4,5)P2 biosensor iRFP-PHPLCδ1 was generated by N-terminal fusion of iRFP (31857; Addgene) (24) with the pleckstrin homology domain of human PLCδ1 (residues 11–140) (25). All cloning was done using standard molecular biology techniques. Detailed information about cloning and other fusion proteins used in this study is found in SI Materials and Methods.

Cell Culture and Transfection for Imaging.

COS-7 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 4.5g/L glucose, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 10% (vol/vol) FBS and were cultured in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% (vol/vol) CO2. PC-12 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 25 mM glucose, 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated horse serum, and 5% (vol/vol) FBS. Transient transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Before imaging, cells were transferred to a buffer containing (in mM) 125 NaCl, 4.9 KCl, 1.28 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 3 glucose, and 25 Hepes adjusted to pH 7.4 with 2 M NaOH.

Confocal Microscopy.

Spinning-disk confocal microscopy was performed using the Improvision UltraVIEW VoX system (Perkin-Elmer) built around a Nikon Ti-E inverted microscope, equipped with PlanApo objectives (60× 1.45-NA) and controlled by Volocity (Improvision) software. Laser light (488 nm) was used to induce dimerization between CRY2 and CIBN and to image GFP-fusion proteins, and 561-nm and 640-nm laser lines were used to image mCherry/mRFP and iRFP, respectively. Images typically were sampled at 0.2 Hz with exposure times in the 100- to 500-ms range. A built-in fluorescence recovery after photobleaching unit was used to deliver 488-nm light with subcellular precision, using 2% of the total laser output (50 mW) and 100- to 200-ms illumination. All imaging was performed at 37 °C except for the experiments shown in Fig. 3 (see below), which were performed at room temperature.

TIRFM.

To visualize plasma membrane fluorescence selectively, cells were imaged at 37 °C with a total internal reflection fluorescent (TIRF) microscope setup built around a Nikon TiE microscope equipped with 60× 1.49-NA and 100× 1.49-NA objectives. Excitation light was provided by 488-nm (for GFP and blue-light activation) and 561-nm (mCherry and mRFP) diode-pumped solid-state lasers coupled to the TIRF illuminator through an optical fiber. The output from the lasers was controlled by an acousto-optic tunable filter, and fluorescence was detected with an EM-CCD camera (DU-887; Andor). Acquisition was controlled by Andor iQ software. Images typically were sampled at 0.2 Hz with exposure times in the 100- to 500-ms range.

Dual Electrophysiological/Confocal Recordings.

KCNQ2/3 currents were recorded from transfected tsA-201 cells in whole-cell, gigaseal voltage clamp configuration using borosilicate glass pipettes with resistance of ∼2.2 MΩ. Recordings were made using an Axon Axopatch 200B amplifier with Pulse software (HEKA). Currents were filtered at 2.9 kHz with sampling intervals of 200 μs. Confocal images were taken using a Zeiss 710 laser-scanning confocal microscope, equipped with a 63× 1.49-NA objective. Dimerization was induced using the 458-nm laser line. Cells were recorded in a 100-μL chamber continuously superfused (1 mL/min) with Ringer's solution containing (in mM) 160 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 8 glucose, pH 7.4 (NaOH). Internal solution was (in mM): 175 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 5 Hepes, 0.1 K4BAPTA, 3 Na2ATP, 0.1 Na3GTP, pH 7.4 (KOH). Electrophysiological and imaging experiments were done at room temperature (21–23 °C).

Image Analysis and Statistics.

Changes in plasma membrane fluorescence (TIRFM) or redistribution of fluorescence between the plasma membrane profile and the cytosol (confocal microscopy) were analyzed off-line using Fiji (http://fiji.sc/wiki/index.php/Fiji). Fluorescence changes were quantified using IgorPro (Wavemetrics Inc.). All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t tests; P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chandra Tucker and Matthew Kennedy for the kind gifts of CRY2-mCherry and CIBN-GP-CAAX, and Stacy Wilson for advice and support regarding imaging. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants NS36251 and DK082700 and by grants from the Ellison and Simons Foundations (to P.D.C.), by NIH Grant NS08174 (to B.H.), and by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Swedish Research Council (to O.I-H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See Author Summary on page 13894 (volume 109, number 35).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1211305109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Odorizzi G, Babst M, Emr SD. Phosphoinositide signaling and the regulation of membrane trafficking in yeast. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vicinanza M, D’Angelo G, Di Campli A, De Matteis MA. Function and dysfunction of the PI system in membrane trafficking. EMBO J. 2008;27:2457–2470. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCrea HJ, De Camilli P. Mutations in phosphoinositide metabolizing enzymes and human disease. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:8–16. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00035.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Bankaitis VA. Phosphoinositide phosphatases in cell biology and disease. Prog Lipid Res. 2010;49:201–217. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villalba-Galea CA. New insights in the activity of voltage sensitive phosphatases. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1541–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falkenburger BH, Jensen JB, Hille B. Kinetics of PIP2 metabolism and KCNQ2/3 channel regulation studied with a voltage-sensitive phosphatase in living cells. J Gen Physiol. 2010;135:99–114. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suh BC, Inoue T, Meyer T, Hille B. Rapid chemically induced changes of PtdIns(4,5)P2 gate KCNQ ion channels. Science. 2006;314:1454–1457. doi: 10.1126/science.1131163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varnai P, Thyagarajan B, Rohacs T, Balla T. Rapidly inducible changes in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate levels influence multiple regulatory functions of the lipid in intact living cells. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:377–382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200607116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zoncu R, et al. Loss of endocytic clathrin-coated pits upon acute depletion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3793–3798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611733104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zoncu R, et al. A phosphoinositide switch controls the maturation and signaling properties of APPL endosomes. Cell. 2009;136:1110–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heo WD, et al. PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(4,5)P2 lipids target proteins with polybasic clusters to the plasma membrane. Science. 2006;314:1458–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1134389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fili N, Calleja V, Woscholski R, Parker PJ, Larijani B. Compartmental signal modulation: Endosomal phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate controls endosome morphology and selective cargo sorting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15473–15478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607040103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Umeda N, Ueno T, Pohlmeyer C, Nagano T, Inoue T. A photocleavable rapamycin conjugate for spatiotemporal control of small GTPase activity. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12–14. doi: 10.1021/ja108258d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenno L, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K. The development and application of optogenetics. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:389–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toettcher JE, Gong D, Lim WA, Weiner OD. Light-based feedback for controlling intracellular signaling dynamics. Nat Methods. 2011;8:837–839. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu YI, et al. A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature. 2009;461:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levskaya A, Weiner OD, Lim WA, Voigt CA. Spatiotemporal control of cell signalling using a light-switchable protein interaction. Nature. 2009;461:997–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature08446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tucker CL. Manipulating cellular processes using optical control of protein-protein interactions. Prog Brain Res. 2012;196:95–117. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-59426-6.00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Y, Melia TJ, Toomre DK. Using light to see and control membrane traffic. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:822–830. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy MJ, et al. Rapid blue-light-mediated induction of protein interactions in living cells. Nat Methods. 2010;7:973–975. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ooms LM, et al. The role of the inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases in cellular function and human disease. Biochem J. 2009;419:29–49. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pirruccello M, De Camilli P. Inositol 5-phosphatases: Insights from the Lowe syndrome protein OCRL. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filonov GS, et al. Bright and stable near-infrared fluorescent protein for in vivo imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:757–761. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stauffer TP, Ahn S, Meyer T. Receptor-induced transient reduction in plasma membrane PtdIns(4,5)P2 concentration monitored in living cells. Curr Biol. 1998;8(6):343–346. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steyer JA, Almers W. A real-time view of life within 100 nm of the plasma membrane. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:268–275. doi: 10.1038/35067069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klarlund JK, et al. Regulation of GRP1-catalyzed ADP ribosylation factor guanine nucleotide exchange by phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1859–1862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balla A, Tuymetova G, Tsiomenko A, Várnai P, Balla T. A plasma membrane pool of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate is generated by phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type-III alpha: Studies with the PH domains of the oxysterol binding protein and FAPP1. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1282–1295. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dowler S, et al. Identification of pleckstrin-homology-domain-containing proteins with novel phosphoinositide-binding specificities. Biochem J. 2000;351:19–31. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin-Belmonte F, et al. PTEN-mediated apical segregation of phosphoinositides controls epithelial morphogenesis through Cdc42. Cell. 2007;128:383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janetopoulos C, Ma L, Devreotes PN, Iglesias PA. Chemoattractant-induced phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate accumulation is spatially amplified and adapts, independent of the actin cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8951–8956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402152101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takenawa T, Suetsugu S. The WASP-WAVE protein network: Connecting the membrane to the cytoskeleton. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:37–48. doi: 10.1038/nrm2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridley AJ, Paterson HF, Johnston CL, Diekmann D, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell. 1992;70:401–410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gassama-Diagne A, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate regulates the formation of the basolateral plasma membrane in epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:963–970. doi: 10.1038/ncb1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iijima M, Devreotes P. Tumor suppressor PTEN mediates sensing of chemoattractant gradients. Cell. 2002;109:599–610. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00745-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janetopoulos C, Borleis J, Vazquez F, Iijima M, Devreotes P. Temporal and spatial regulation of phosphoinositide signaling mediates cytokinesis. Dev Cell. 2005;8:467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]