Abstract

There is concern in Australia that droughts substantially increase the incidence of suicide in rural populations, particularly among male farmers and their families. We investigated this possibility for the state of New South Wales (NSW), Australia between 1970 and 2007, analyzing data on suicides with a previously established climatic drought index. Using a generalized additive model that controlled for season, region, and long-term suicide trends, we found an increased relative risk of suicide of 15% (95% confidence interval, 8%–22%) for rural males aged 30–49 y when the drought index rose from the first quartile to the third quartile. In contrast, the risk of suicide for rural females aged >30 y declined with increased values of the drought index. We also observed an increased risk of suicide in spring and early summer. In addition there was a smaller association during unusually warm months at any time of year. The spring suicide increase is well documented in nontropical locations, although its cause is unknown. The possible increased risk of suicide during drought in rural Australia warrants public health focus and concern, as does the annual, predictable increase seen each spring and early summer. Suicide is a complex phenomenon with many interacting social, environmental, and biological causal factors. The relationship between drought and suicide is best understood using a holistic framework. Climate change projections suggest increased frequency and severity of droughts in NSW, accompanied and exacerbated by rising temperatures. Elucidating the relationships between drought and mental health will help facilitate adaptation to climate change.

Keywords: self-harm, depression, rainfall, weather

Suicide, a tragic event with repercussions throughout the community, is a frequent cause of death in Australia. The Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that in 2008 suicide ranked 14th among causes of deaths registered in Australia. In recent decades, the rate has been highest in males aged 30–49 y and over 75 y (1). There is concern in Australia that the incidence of suicide is increased by drought (2). Much of rural Australia, including NSW, experiences prolonged periods of dryness and low rain. In this study, drought is defined as a persistent lack of rainfall compared with a location’s median rainfall (Materials and Methods).

There are several plausible mechanisms by which drought may increase the suicide rate. First, droughts increase the financial stress on farmers and farming communities. Such difficulty may occur in conjunction with other economic stresses, such as rising interest rates, falling commodity prices, or an unfavorable foreign exchange rate. Second, environmental degradation can take a great psychological toll (3), which may be acute during droughts, linked with decisions and actions to sell or kill starving animals or to destroy orchards and vineyards, which in some cases were accumulated painstakingly over generations. Such loss, and even the apprehension of loss, undoubtedly places a burden on the mental health of farmers and their families. This mourning may not be confined to farmers, but also may extend to other sections of the community likely to be impoverished by long-term environmental degradation. The experience of seeing suffering wild plants and animals, or parched urban parks and gardens, and contemplation of their loss is likely to be extremely painful for some individuals. Some people may have especially high sensitivity to nature (4) and thus may be at greater risk of self-harm during drought, irrespective of whether their residence is rural or urban. However, alongside the many complex influences affecting suicide rates, we did not assume that this would be a clear signal.

To date, few studies have examined the relationship between suicide and drought. Despite the dearth of data, however, drought has been strongly linked with Australian rural suicide rates by news media and suicide prevention advocacy groups, such as the national depression initiative “Beyondblue.” Attribution of suicide risk to drought is less certain than these reports suggest, and thus warrants investigation. One analysis of annual suicide rates in NSW found an association between suicide and year-to-year decline in annual rainfall between 1964 and 2001 (2). In that study, a 300-mm decrease in rainfall was associated with an ∼8% increase in suicide rate above the mean annual rate.

Another study in NSW found an association between suicide and drought over the period 1901–1998. That study focused on the association of conservative government and suicide (5). The authors argued that conservative administrations placed greater stress on individualism, diminishing social capital and enhancing the risk of suicide in vulnerable individuals. The authors controlled for drought (among other factors) and found that drought years were associated with an increase in suicide risk of ∼7% in men and 15% in women across the whole population. To our knowledge, no other studies of suicide and drought, either in or beyond Australia, have been published. However, numerous studies have explored links between suicide and climate variables other than drought. For example, temperature has been studied in many locations using various methods to define the exposure variable including daily, monthly, and annual measures (6, 7). These studies yielded conflicting results. Some found a decreased suicide rate associated with an increase in temperature (8), whereas others observed the converse (9). One study found a U-shaped response, with elevated suicide risk on extremely cold and hot days (10).

The most consistent finding possibly related to climate is a seasonal variation, with a suicide peak evident in spring. This finding is consistently observed in extratropical locations in both hemispheres (6). Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain this association, including direct and indirect climatic effects. An early theory, supporting an indirect climatic causal influence, is that social life intensifies in spring (11). A similar indirect climatic influence is implicit in the “broken promise” hypothesis, which suggests that suicide is triggered in vulnerable persons when their expectations of better times following winter are unfulfilled (12). More direct climatic influences are suggested by theories that propose biochemical and neurologic changes associated with circannual rhythms, especially related to enhanced vitamin D production from greater sunlight exposure (13). Another hypothesis links increased spring pollen exposure with coincidental binge drinking, which interact to aggravate the immune response and increase suicidal depression in allergy sufferers (14).

Results

We calculated the Hutchinson Drought Index (15), which counts consecutive months of lower-than-median rainfall based on percentiles of rainfall records at each location, to investigate whether suicide risk rose with increasing duration of drought. This index has been found to successfully identify periods of declared agricultural drought. Because the Hutchinson Drought Index is skewed with many zeros, we used a logarithmic transformation. The monthly maximum temperature anomalies were not correlated with the drought index in our data (SI Appendix). Rainfall was not included directly in any of the models that we used.

We fitted monthly Poisson time series generalized additive models (GAMs). We expected a substantial increase in suicide associated with drought in rural men over age 30 y (assuming that this subgroup contained a high proportion of farmers), and anticipated that other age/sex/location subgroups could have different (even nonlinear) associations. We used the generalized cross-validation tool in the MGCV package of R (16) to automatically estimate the appropriate shape of subgroup response functions.

Our core model included the predictors season, age group, and sex-specific long-term suicide trends in 11 regions of NSW. We then added the drought index and temperature as the key climatic predictive variables and tested for associations with suicide. We assessed the possibility of modification of the assessed effect of the drought index on suicide owing to any of the other covariates. We used the Schwarz Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for each model to identify the best-performing model. The addition of an interaction term on sex and region improved the BIC score over the core model. The BIC scores did not show strong support for the models with the climatic predictors compared with more parsimonious models that included only season, age, sex, region, and long-term trends on time.

We then explored suicide risk in rural men by fitting interaction terms by age, sex, and geographic location. The 11 regions were classified as rural or urban based on the location of the major cities in NSW (Materials and Methods). We used the category of rural males age >30 y as a proxy indicator for farmers, although this likely underestimated the suicide risk in farmers, given that other researchers found a higher risk of suicide in this group compared with the surrounding rural population (17, 18).

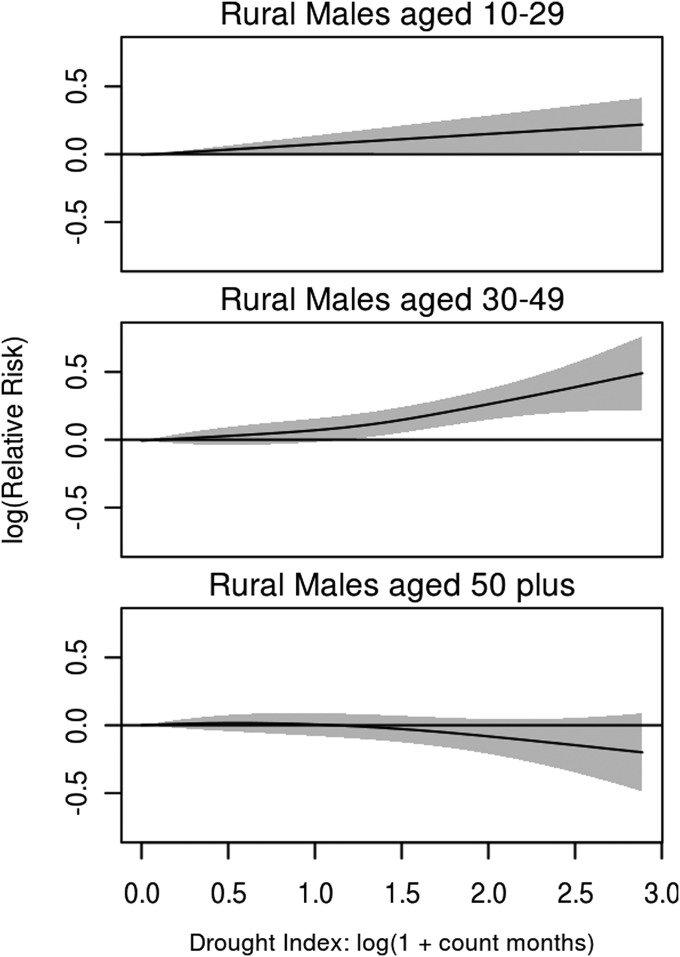

Figs. 1 and 2 show the response functions for suicide risk and drought in rural subgroups with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For example, the estimated relationship between drought and suicide among males aged 30–49 y is shown by a more or less straight line, rising with drought duration as measured by the drought index. A statistically significant increase in risk of 15% (95% CI, 8–22%; P < 0.0001) was found when the drought index rose from the first to the third quartile.

Fig. 1.

Association between suicide risk and drought in rural males. Shaded areas represent 95% CIs.

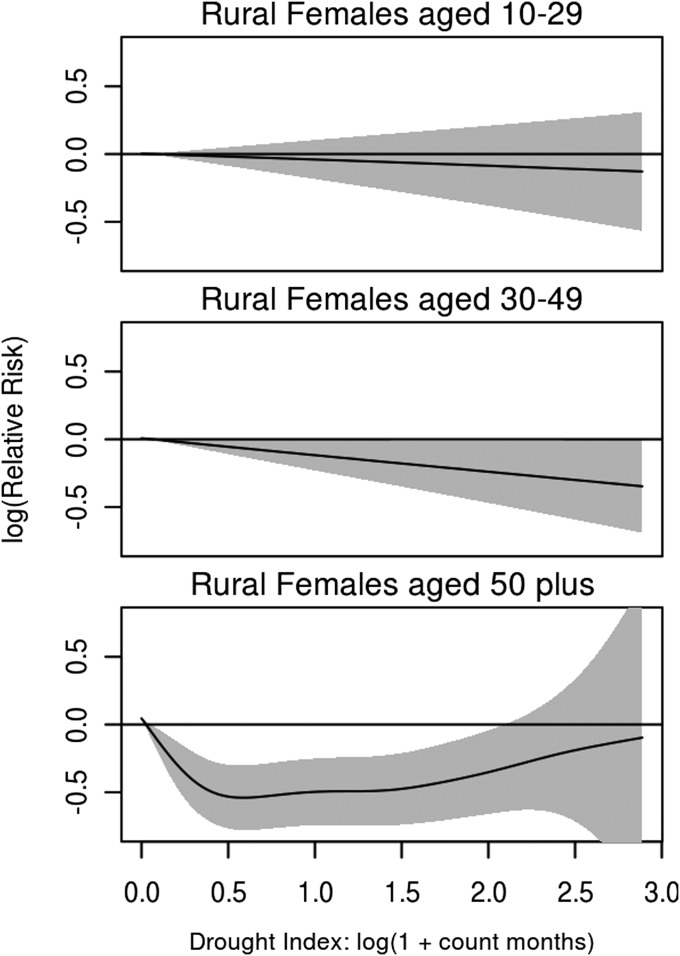

Fig. 2.

Association of suicide risk and drought in rural females. Shaded areas represent 95% CIs.

The predicted number of annual suicides in rural males aged 30–49 associated with drought over our study period was 4.01 (95% CI, 2.14–6.05), accounting for 9% of the total number in that group over the entire 38 y of our study. Given that drought is episodic and confined to a minority of the study years, the modeled impact of drought on the number of suicides in this subpopulation is much greater than 4 per annum during drought years.

The rural female associations showed a statistically significant decrease in risk (−0.72 per annum; 95% CI, −1.32 to −0.01; P < 0.05). This finding was unanticipated, given that an earlier study (albeit conducted over a different time period) found a greater risk in females compared with males (5). We found that modeling the males and females separately in the rural 30–49 y age group was more statistically significant than when these were combined in the model (P < 0.0001, likelihood ratio test). We also found a statistically significant increase in risk associated with drought for rural males aged 10–29 y (P < 0.01). Our analyses for the urban population found no association between drought and suicide. Subgroup results are provided in SI Appendix.

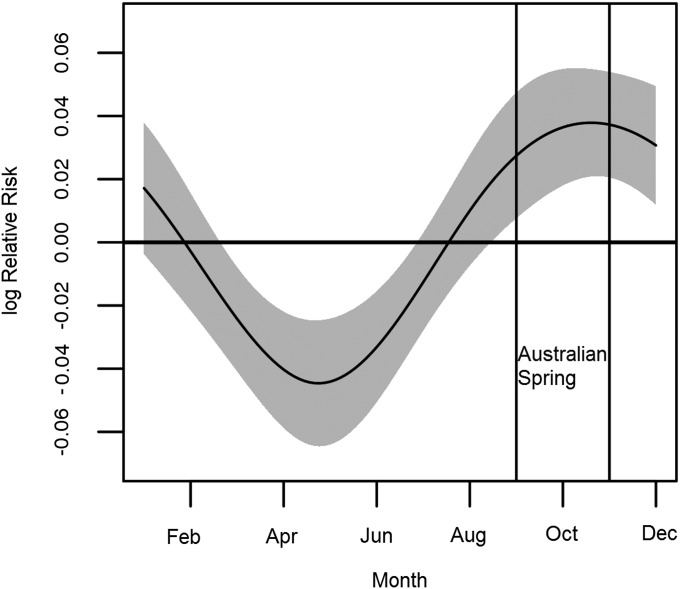

Fig. 3 shows the estimated increased relative risk during spring and early summer. The relative risk of suicide increased as a linear function with warmer-than-average months. Relative risk rose by ∼3% (95% CI, 1–5%) per interquartile range rise in monthly maximum temperature anomaly (i.e., 1.6 °C).

Fig. 3.

Suicide risk peaks in spring and early summer. This curve is a cyclic spline derived from the core GAM (age, sex, rural location, and trend) adjusted for temperature but excluding drought.

Discussion

Our analysis of the relationship between drought and suicide was stratified by age, sex, and regional subgroups to explore different potential effects of drought, especially on farmers and farm workers. We were particularly interested in the category of rural men aged 30 y and older as a group likely to include many farmers. Our results showed an increased risk of suicide during drought in rural males aged 10–29 y and 30–49 y, but a decreased risk in rural females aged >30 y.

Although we found an increased risk due to drought in rural males aged 30–49 y, consistent with our original hypothesis that drought increases suicide risk among farmers and farming communities, the BIC rankings did not strongly support inclusion of the drought variable in the most parsimonious model (SI Appendix). This may be due to the occurrence of this association only in the subgroups of rural males aged 10–29 y and 30–49 y, with the relationship between drought and suicide in other subgroups (especially rural females) being different, nonexistent, or opposite. However, given our numerous model combinations, inferences based on models with less support from the BIC scores should be interpreted with caution.

Our results are broadly consistent with data from other studies of suicide and climate, notably that of Nicholls et al. (2), and the results in males reported by Page et al. (5). We found distinct age, sex, regional, and long-term time trends in suicide rates with increased risk associated with spring and a smaller association with above-average maximum temperatures.

The decrease in suicide risk associated with drought for rural females contradicts the data of Page et al. (5), who reported an increased risk for women during drought years. However, that study was conducted over a much longer time period with different explanatory variables. Unlike ours, it included the “sedative epidemic” of 1960–1967 (19), a period of easy availability of barbiturates, during which female suicide rates were much higher than in subsequent years.

Our modeling results do suggest that drought increases the suicide rates for males aged 30–49 in rural communities, and it is likely that many of these men are farmers or farmworkers (18). However, the risk for rural females fell. There are several possible explanations for this finding. One is that rural women may have access to more diverse social support mechanisms and thus may be able to find outlets to relieve stress. Rural women also may be more personally resilient, even in the face of drought-related hardships, including the need to care for severely depressed partners. Further, community support may strengthen, and people may pull together more as droughts persist and worsen, reinforcing social support networks in ways that particularly benefit rural women. Another possibility is that the drought declarations by the government (and associated welfare support) have a differentially beneficial influence on rural women.

Our study raises several unanswered questions. One is whether there are finer resolution regional differences, with some locations experiencing an association more than (or differently from) others. Furthermore, a marked decrease in the NSW rural suicide rates became apparent starting around 1997, even though much of NSW was in severe drought from 2000 to 2007. In 1997, in response to the Port Arthur Massacre, strict restrictions were placed on gun availability, which might have reduced suicides in general, including those associated with drought, especially in the rural community (20). The last 10 years has also seen an intensification of suicide prevention campaigns (21), increased drought support payments, and wider availability of improved antidepressant drugs. Finally, changes have been made to the way in which cause of death is coded in the database, which might have led to substantial underreporting (22).

Our study has several limitations. One is that suicide is influenced by both long-term and short-term factors, and suicidal events are likely to be lagged sometimes. The manifestation of drought’s influence on suicide is likely to be complicated by these different time scales and causal pathways. We used the best available suicide and climatic data; however, the uncertain quality of the rainfall data might have reduced the precision of our calculated drought index. The drought index is based on the percentile ranking of each 6-mo average out of the entire 118 y of available rainfall record (1890–2008). Such a long period is needed to calculate extreme rainfall deficits. However, spatial rainfall models are generally considered to be of lesser quality in Australia before 1920 owing to the sparsely distributed network of monitoring stations in place at that time. In our case, however, the study region of NSW was relatively densely populated even in the 1890s. Therefore, we believe it is legitimate to include rainfall data from the entire available period to support our analysis.

Another potential limitation is that the spatial interpolation technique used by the Bureau of Meteorology to produce the rainfall data (the Barnes inverse distance-weighted method) does not account for the influence of elevation. However, although such deficiencies would affect the magnitudes of rainfall values, they would have less effect on the percentile ranks used in the calculation of the drought index.

Suicide is a complex phenomenon with many causal influences, and thus the lack of markedly strong signals in this analysis is not surprising. Future research may benefit from the use of a more holistic framework to systematically investigate how combinations and interactions among various factors influence suicide risk. Indeed, a framework for analyzing rural livelihoods that addresses these issues does exist (23), in the form of assessment of “five capitals” comprising financial, physical, social, human, and natural forms. This conceptualization includes a more comprehensive range of explanatory variables than we have modeled in the present study. For example, we included monthly temperature anomalies as a nuisance parameter to control for potential confounding; however, it may be that the increased risk of suicide mortality is related to the fact that droughts often have higher-than-average temperatures, which can increase mortality due to thermal stress (although, as noted in Results, these variables are not highly correlated in our dataset).

In this framework, multiple alternate hypotheses could be explored rigorously, and the potential interplay among biological, social, and environmental mechanisms examined. Other important variables to include might be selected from different perspectives that emphasize elements from the five types of capital. For example, a biological perspective might suggest immune system function, physiological strain, and psychiatric effects of vitamin D and serotonin as indicators of human capital. An economical perspective could select farmer debt and terms of trade as indicators of financial capital. An environmental perspective might add pollen concentrations or soil degradation to drought as indicators of natural capital. A sociological perspective could identify politics and disadvantaged groups such as indigenous Australians as measures of social capital. Finally a psychological perspective could identify depressing elements of the built environment to include as indications of physical capital. Teasing apart this complex mix of causal influences is made difficult by lack of appropriate data and is beyond the scope of this paper.

It is also important to consider the various elements of environmental factors, mental health, and depression. For example, a recent study found no relationship between drought and mental health indicators (24), possibly implying an association between drought and suicide but not between drought and depression. Such an approach may help disentangle the numerous putative risk factors for rural and farmer suicide in NSW, revealing a clearer picture of the influence of drought on suicide.

Suicide and drought is an important research theme in Australia because the continent is often affected by drought. Furthermore, climate change projections indicate future increases in the frequency, intensity, and area affected by droughts in NSW, along with decreases in rainfall and humidity (25, 26). Even though these projections are less certain than those for temperature, if the rainfall changes are unexpectedly slight, then warmer temperatures (which are more confidently predicted) will exacerbate dry periods owing to increased evapotranspiration (27). Thus, droughts are likely to increase.

Conclusions

This study addresses the substantial concern in Australia that droughts increase suicide in farmers and farm workers. We found clear evidence to support this hypothesis, with the modeled number of suicides in rural males aged 30–49 y due to drought representing ∼9% of total deaths in that group over the entire 38 y of our study period 1970–2007. This subgroup is suspected to be at higher risk because of its many farmers and farmworkers. We also found an increased risk of suicide associated with drought in rural males aged 10–29 y, supporting the inference that there are flow-on effects to the broader rural community.

We investigated the data on drought and suicide at monthly and regional scales, controlling for season, age, sex, and trends over time. Using the Hutchinson Drought Index, we identified a multifaceted relationship between suicide and drought. This finding broadens the relevance of this drought index, which had previously been found to be significantly associated with declared agricultural drought.

An unexpected result was the statistically significant reduction in suicide risk during drought in rural females aged >30 y. A prominent finding was the increased risk of suicide in spring and early summer, but a lower risk of suicide in spring than during drought periods in males aged 30–49 y. However, because spring occurs every year, and because it increases the risk of suicide in all regions, for both sexes, and all age groups, the burden of suicide during spring is probably slightly greater than that of drought. We also found an association between times of unusually high maximum temperatures and increased suicide risk.

Improved understanding of these issues has important public health implications, including the timing of suicide prevention campaigns. Identifying the periods of greatest risk may allow better use of limited resources, such as promotion of counseling services to target vulnerable persons, not only during extended droughts, but also each spring. Finally, we suggest that future suicide research should consider the causation of suicide using a holistic framework that involves financial, physical, social and human factors together with natural influences, such as season and climate change.

Materials and Methods

Drought Index.

We assessed the relationship between suicide and the Hutchinson Drought Index using time series Poisson GAMs of monthly data for 11 regions of NSW between 1970 and 2007. It is possible to distinguish four types of droughts: Climatic drought (based on precipitation), agricultural drought (plant and crop stress), hydrological drought (stream flow), and socioeconomic drought (supply and demand of water). Several drought indices are available. To select the index for the present study, we used three criteria: (i) applicability to suicide in NSW; (ii) ease of calculation and validity of underlying assumptions; and (iii) availability of spatial data to represent the extent of the droughts across the study regions. Based on these criteria, we chose the Hutchinson Drought Index (15), which integrates consecutive months of lower-than-median rainfall based on percentiles of rainfall records at each location. A full description and R codes are provided in SI Appendix.

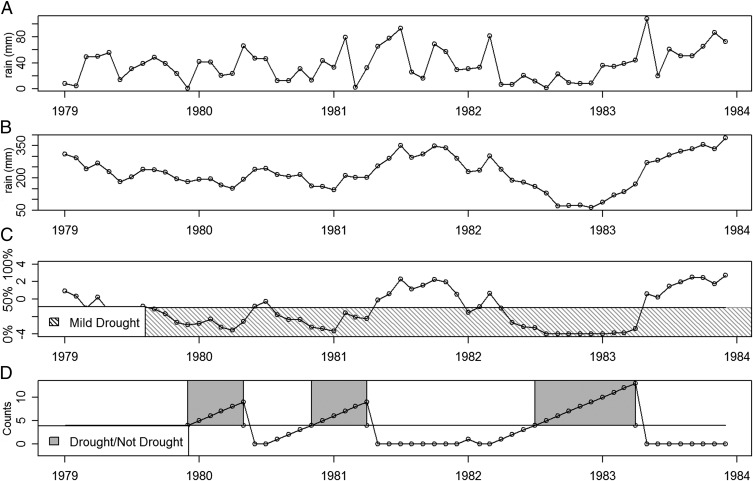

The original method identified a threshold via calibration with NSW government drought declarations data to produce a binary variable for drought. However, we used the index as a continuous variable because we suspected that suicide risk would rise with increasing duration of drought. Because the drought index is skewed, we performed a logarithmic transformation. The steps taken to calculate the index are shown graphically in Fig. 4. First, the raw monthly rainfall totals (Fig. 4A) were integrated to rolling 6-mo total rainfall values (Fig. 4B) and expressed as percentiles with respect to the rainfall totals for the same 6-mo sequence over all the years of record (Fig. 4C). These percentiles were then linearly rescaled to lie between −4 and +4, in keeping with the range of the Palmer Index (28). Then an accounting procedure was used to integrate these percentile ranks (Fig. 4D). The consecutive months were counted whenever the index dropped below −1 (the threshold for mild drought on the Palmer Index). The count was reset to 0 each time the drought index rose above −1 and was restarted whenever the drought index fell below −1 again.

Fig. 4.

Drought index in Central West NSW during a period that included a severe drought (1982–1983). The raw monthly rainfall totals (A) were integrated to rolling 6-mo totals (B), which were then ranked into percentiles by month and rescaled to range between −4 and +4 (C). Mild drought is below −1, and so consecutive months below this threshold were counted (D). A period of 5 or more consecutive months was defined as a drought in the original method.

The best agreement with the occurrence of drought declarations for this index was found when this threshold was set at 5 mo. At this level, the optimal balance of declared droughts were successfully identified (50%) with the fewest false-positives, with a mean of 2 per drought declaration zone. As a sensitivity analysis, we assessed an enhancement to the index that increases the threshold amount of rainfall required to end a drought period from the original cutoff of −1 to a more substantial amount of 0 (i.e., the median rainfall). Descriptive statistics for the drought index are provided in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Ethical approval for this work was granted by the Australian National University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol no. 2004/0293).

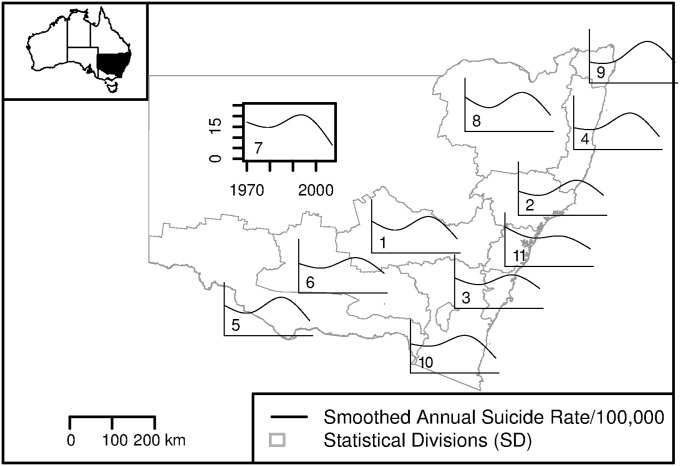

Study Region.

The geographic regions of the present study are areas termed Statistical Divisions (SDs) in the Australian Bureau of Statistics’s population census (Fig. 5). The 11 regions were classified as rural or urban based on the locations of the three major cities of NSW: Sydney (Fig. 5, no. 11), Newcastle (Hunter SD, Fig. 5, no. 2), and Wollongong (Illawarra SD, Fig. 5, no. 3). All other SDs were classed as rural. Two SDs (North West and Far Western) were merged because their populations were considered too small to yield reliable suicide rates. All SD boundaries remained consistent from 1970 to 2007, another benefit compared with smaller areas with boundaries that change over time, confounding exposure estimation in time series studies (29).

Fig. 5.

NSW SD boundaries with annual suicide rate. Axes are shown on only one plot for simplicity. All axes have the same scale (y-axis, 0–25). Numbers refer to the SD numbers in SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2.

Suicide Data.

Deidentified unit records for each suicide (as determined by a coroner) in NSW between January 1970 and October 2007 were extracted from the Australian Causes of Death Unit Record File. (Data available on request from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The Australian mortality data we use are only available subject to approval by data custodians in the government.) The final months of 2007 were excluded because of the known delay in reporting of suicide deaths. The suicide records include the day of death, age, sex, and place of usual residence of the person who died. Unfortunately, the exact location of death and time living at the place of usual residence are not recorded in the mortality database, hindering precise exposure estimation. The causes of death were coded using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system, which was revised three times during the study period. The codes for suicide and intentional self-inflicted injury were E950.0–E959.9 in ICD-8 (used in 1970–1978) and ICD-9 (used in 1979–1996) and X60–X84.9 and Y87.0 in ICD-10 (used from 1997 to the present). There are some issues with the comparability of ICD codes across coding system changes. For suicide deaths, ICD-8, -9, and -10 classifications are considered comparable across this period (30). We included a long-term trend variable in models that would account for changes in the time series such as this. In some other studies, injuries coded as “undetermined if accidental or intentional” are included with suicides (ICD-8 and ICD-9 codes E980.0–E989.9 and ICD-10 codes Y10.0–Y34.9, Y87.2, and Y89.9) (31–33). Over the study period, some changes to suicide coding caused some differences in the number of deaths coded as undetermined; thus, we only used these codes in a sensitivity analysis to check for the possibility of bias owing to misclassification for the other years of the study (22). The annual suicide rates per 100,000 for each SD between 1970 and 2007 are shown in Fig. 5, and summary statistics are provided in SI Appendix, Table S2.

Population Data.

We used the Australian census of population and housing data collected every 5 y. These data were available for local government areas for 1971–1981 and for statistical local areas for 1986–2006 (data available from the Australian Social Science Data Archives, Canberra, Australia). We assigned each local area to its SD region and categorized the populations into 10-y age groups from 10 y to 70 y and older. The population of each age and sex group in each region was linearly interpolated by month for inclusion in our models.

Climate Data.

Monthly rainfall data for 1890–2008 at a resolution of 0.25 degrees latitude and longitude were used. The meteorological surfaces were constructed by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology using the Barnes inverse distance-weighted spatial interpolation approach adopted by the National Climate Centre of the Bureau of Meteorology’s Research Centre in Melbourne. Monthly average maximum temperatures were obtained as well. That gridded dataset extends from 1950 to 2008. Monthly maximum temperature anomalies were calculated as the difference between each month’s temperature and the long-term average for that month. The gridded monthly rainfall data were used to calculate a drought index based on 6-mo percentiles for each grid cell’s entire rainfall record. These grid values were then averaged within our spatial units. We used a PostgreSQL database (http://www.postgresql.org) with the PostGIS spatial extension (http://postgis.refractions.net/) for our spatial data analysis. The Australian weather data we use are available from the Bureau of Meteorology Web site (http://www.bom.gov.au/).

Model Selection Procedure.

We performed model selection using the BIC, with the model with the lowest BIC value considered the best model. Initially, we fitted a model of the death counts per month controlling for age, sex, region, season, and long-term trend in suicide rate without including climatic variables. Population was included as an offset. At first, we did not include climate variables so that we could assess the control required for our other covariates. We tested a quasi-Poisson generalized linear model to check for overdispersion. We also tested models for age-, sex-, and region-specific time trends. The trend was assumed to be unrelated to drought but to be driven by longer-term secular trends and changes, such as disease classification coding changes, antidepressant availability, or the 1997 gun control policy introduced after the Port Arthur Massacre (20). A natural cubic spline with 3 df on the sequential month rank was considered sufficient to capture these changes. Such trends may vary across age, sex, and region groups. We assessed the presence of such differences using interaction models of these variables, allowing a specific trend for each group (e.g., a sex-specific or age-specific trend), as well as three-way interactions (e.g., an age-and-sex specific trend), and finally a complete interaction as age-, sex-, and region-specific trends. There appeared to be a seasonal pattern, so we used a cyclic cubic spline with 4 df. We then added the drought term and the maximum temperature terms as penalized regression splines in GAMs, using the generalized cross-validation tool to automatically estimate the appropriate curvature of these response functions (16). Using the estimated optimal smooth on these terms, we used generalized linear models to assess all of the potential paired combination interaction models.

Analysis Code.

Analyses were performed using R statistical language and environment version 2.10.0 (http://www.r-project.org). An Sweave file of the R codes used in drought index calculation and model fitting, along with additional graphs and tables, are provided in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Keith Dear for statistical advice, the reviewers for their constructive suggestions that contributed to the completeness of the final version of the manuscript, and Prof. Tony McMichael and Prof. Bryan Rodgers for financial support for this work.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1112965109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Causes of Death, Australia, 2008. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicholls N, Butler CD, Hanigan I. Inter-annual rainfall variations and suicide in New South Wales, Australia, 1964-2001. Int J Biometeorol. 2006;50:139–143. doi: 10.1007/s00484-005-0002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speldewinde PC, Cook A, Davies P, Weinstein P. A relationship between environmental degradation and mental health in rural Western Australia. Health Place. 2009;15:865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louv R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page A, Morrell S, Taylor R. Suicide and political regime in New South Wales and Australia during the 20th century. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:766–772. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.10.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon P, Kalkstein A. Climate–suicide relationships: A research problem in need of geographic methods and cross-disciplinary perspectives. Geography Compass. 2009;3:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deisenhammer EA. Weather and suicide: The present state of knowledge on the association of meteorological factors with suicidal behaviour. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108:402–409. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai J-F. Socioeconomic factors outweigh climate in the regional difference of suicide death rate in Taiwan. Psychiatry Res. 2010;179:212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim Y, Kim H, Kim D-S. Association between daily environmental temperature and suicide mortality in Korea (2001-2005) Psychiatry Res. 2011;186:390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Wang D, Wang X. Suicide and meteorological factors in Huhhot, Inner Mongolia. Crisis. 1997;18:115–117. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.18.3.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durkheim E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabennesch H. When promises fail: A theory of temporal fluctuations in suicide. Soc Forces. 1988;67:129–145. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert G, Reid C, Kaye D, Jennings G, Esler M. Increased suicide rate in the middle-aged and its association with hours of sunlight. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:793–795. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reeves GM, Tonelli LH, Anthony BJ, Postolache TT. Precipitants of adolescent suicide: Possible interaction between allergic inflammation and alcohol intake. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2007;19:37–43. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2007.19.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith DI, Hutchinson MF, McArthur RJ. Climatic and Agricultural Drought: Payments and Policy. Canberra, Australia: Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies, Australian National University; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood S. Fast, stable direct fitting and smoothness selection for generalized additive models. J R Stat Soc B. 2008;70:495–518. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page AN, Fragar LJ. Suicide in Australian farming, 1988-1997. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36:81–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller K, Burns C. Suicides on farms in South Australia, 1997-2001. Aust J Rural Health. 2008;16:327–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2008.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliver RG, Hetzel BS. An analysis of recent trends in suicide rates in Australia. Int J Epidemiol. 1973;2:91–101. doi: 10.1093/ije/2.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leigh A, Neill C. Do gun buybacks save lives? Evidence from panel data. Am Law Econ Rev. 2010;12:462–508. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM. Changes in depression awareness and attitudes in Australia: The impact of Beyondblue: the national depression initiative. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:42–46. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Leo D. Suicide mortality data need revision. Med J Aust. 2007;186:157–158. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kokic P, Davidson A, Boero Rodrigez V. Australia’s grain industry: Factors influencing productivity growth. Australian Commodities. 2006;13:705–712. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly BJ, et al. Determinants of mental health and well-being within rural and remote communities. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:1331–1342. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirono DGC, Kent DM, Hennessy KJ, Mpelasoka F. Characteristics of Australian droughts under enhanced greenhouse conditions: Results from 14 global climate models. J Arid Environ. 2011;75:566–575. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christensen JH, et al. Regional climate projections. In: Solomon SD, et al., editors. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 2007. pp 848–940. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholls N, Collins D. Observed climate change in Australia over the past century. Energy Environ. 2006;17:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer W. 1965. Meteorological Drought. (US Department of Commerce Weather Bureau, Washington, DC), Research paper no. 45.

- 29.Blake M, Bell M, Rees P. Creating a temporally consistent spatial framework for the analysis of inter-regional migration in Australia. Int J Popul Geogr. 2000;6:155–174. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Suicides 1921–1998. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steenkamp M, Harrison J. Suicide and Hospitalised Self-Harm in Australia. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caldwell TM, Jorm AF, Dear KB. Suicide and mental health in rural, remote and metropolitan areas in Australia. Med J Aust. 2004;181(7, Suppl):S10–S14. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkinson D, Gunnell D. Youth suicide trends in Australian metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas, 1988-1997. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:822–828. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.