Abstract

Although possible sources and functions of the resting-state networks (RSNs) of the brain have been proposed, most evidence relies on circular logic and reverse inference. We propose that autonomic arousal provides an objective index of psychophysiological states during rest that may also function as a driving source of the activity and connectivity of RSNs. Recording blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal using functional magnetic resonance imaging and skin conductance simultaneously during rest in human subjects, we found that the spontaneous fluctuations of BOLD signals in key nodes of RSNs are associated with changes in nonspecific skin conductance response, a sensitive psychophysiological index of autonomic arousal. Our findings provide evidence of an important role for the autonomic nervous system to the spontaneous activity of the brain during “rest.”

Introduction

Despite an explosion of interest in the default mode network (DMN) (Raichle et al., 2001) and the anticorrelated task-positive network (TPN) (Fox et al., 2005), which compose the resting-state networks (RSNs) of the brain during “rest” (Deco et al., 2011), hypotheses about the functional role of spontaneous brain activity nearly always rely on the logically flawed practice of reverse inference (Deco et al., 2011; Poldrack, 2011). Among others, one attempt to explore the causal basis of RSNs has been the simultaneous recording of the brain's electrophysiological activity (Mantini et al., 2007). However, the electrical activity of the brain is known to fundamentally relate to blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) activity (Logothetis et al., 2001). Thus, electrophysiological measures may merely provide a more specific explanation of the neural activity relating to spontaneous BOLD fluctuations (Fox and Raichle, 2007), rather than a causal explanation or objective index of mental states.

By definition, rest suggests no specific instructions. Therefore, we cannot use the common approach of task-induced changes in psychological processes to examine brain activity; activity could no longer be labeled “spontaneous.” However, it has been recognized that rest is more akin to a task (with relatively unknown psychological correlates) than to a baseline (Deco et al., 2011). One tenable approach to objectively measure mental states during rest is to use psychophysiological indices, much as has been done for decades in emotion research (Schachter and Singer, 1962). In relation to RSNs, the “signal” is primarily thought to comprise a combination of anatomical and functional neural connectivity patterns (Fox and Raichle, 2007; Mantini et al., 2007; Honey et al., 2009), while the “noise” is related to purportedly confounding sources, such as activity related to the autonomic nervous system (ANS; e.g., heart-rate, respiration) (Chang and Glover, 2009; Iacovella and Hasson, 2011). However, evidence suggests that variation in arousal and other ANS activity can affect RSNs (Birn et al., 2008; Iacovella and Hasson, 2011). A significant relationship between ANS activity and RSNs would provide evidence that psychophysiological states during resting-state data collection are a potential source and/or functional explanation of correlational patterns in spontaneous brain activity.

We studied the contribution of ANS to RSN activity by measuring nonspecific (nontask) skin conductance response (SCR) and related brain activity and connectivity during rest. SCR shares common neural regions with the TPN [e.g., anterior insular (AI) and anterior cingulate cortices (ACC)] for autonomic, affective, and cognitive integration (Critchley, 2002; Critchley et al., 2011). While respiratory and heart rate variability (HRV) can serve as indices of ANS activity at the same filter band for resting-state functional connectivity MRI (rs-fcMRI) (Shmueli et al., 2007; Birn et al., 2008), the typical SCR curve and hemodynamic response function exhibit similar waveforms (Boucsein, 1992), sparing the need for convolution (Patterson et al., 2002) and facilitating modeling. Because the brain is part of a dynamic homeostatic system (Thompson and Varela, 2001; Craig, 2002; Deco et al., 2011), we hypothesized that autonomic arousal would be associated with resting-state functional activity and connectivity of the brain.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Healthy volunteers (N = 15, male only, mean ± SD age, 27.1 ± 8.2 years) participated in this study. The consent procedure was approved by the institutional review board of Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Data acquisition

Skin conductance recording.

GSR100C (BIOPAC Systems), together with the base module MP150 and the AcqKnowledge software (version 3.9.1.6), was used to record skin conductance during the rs-fcMRI session. The GSR100C applies a constant voltage (0.5 V) between the two electrodes attached to the skin to measure skin conductance. It measures the skin conductance level (SCL) and SCR, which vary with sweat gland activity due to stress, arousal, or emotional excitement. Skin conductance, measured in μS, was recorded using a 2000 Hz sampling rate (gain = 2 μS/V, both high-pass filters = DC, low-pass filter = 10 Hz). Two EL507 disposable EDA (isotonic gel) electrodes were placed on the palmar surface of the distal phalanges of the big and second toes of the left foot after cleaning with alcohol preps. The signal was low-pass filtered (using the MRI-Compatible MRI CBL/FILTER System MECMRI-TRANS) to reduce radio frequency interference from the scanner. Digital event markers were recorded to enable precise time alignment of skin conductance recording with scan onsets. BIOPAC recording was synchronized to the E-Prime program via the parallel port of the computer.

Image data acquisition.

MRI acquisitions were obtained on a 3 T Siemens Allegra MRI system at Mount Sinai School of Medicine. All participants underwent one session with rs-fcMRI first and then fMRI. The scan session lasted ∼1 h in total length. Foam padding was used to reduce participant head motion. All images were acquired along axial planes parallel to the anterior commissure (AC)–posterior commissure (PC) line. A high-resolution T2-weighted anatomical volume of the whole brain was acquired on an axial plane parallel to the AC–PC line with a turbo spin-echo pulse sequence with the following parameters: 40 axial slices of 4 mm thickness; skip = 0 mm; repetition time (TR) = 4050 ms; echo time (TE) = 99 ms; flip angle = 170°; field of view (FOV) = 240 mm; matrix size = 448 × 512, voxel size = 0.47 × 0.47 × 4 mm. One run of T2*-weighted images was acquired for rs-fcMRI. Slices were obtained corresponding to the T2-weighted images. The rs-fcMRI was performed using a gradient echoplanar imaging (EPI) sequence with the following parameters: 40 axial slices, 4 mm thick; skip = 0 mm; TR = 2500 ms; TE = 27 ms; flip angle = 82°; FOV = 240 mm; and matrix size = 64 × 64. The rs-fcMRI run started with two dummy volumes before the onset of the fixation to allow for equilibration of T1 saturation effects, followed by 144 image volumes.

Resting-state functional connectivity MRI procedure.

For the rs-fcMRI, fixation crosshairs were presented in the center of the screen using E-Prime (Psychology Software Tools) for the duration of the run, which lasted 360 s (6 min). Participants were instructed to maintain gaze on the fixation crosshairs and to minimize movement, with the following instruction on the screen before the onset of the scan: “This session takes approximately 6 min. You do not need to perform any tasks during this session. Just fix your eyes at the crosshairs. It is very important that you do not move your head or feet during this time or at all throughout the scan.”

Data analysis

Skin conductance response preprocessing.

The SCR waveform was downsampled by averaging the data points in each 2.5 s bin to match the TR (2.5 s) of the EPI scan of imaging acquisition. Then the SCR waveform (without thresholding) was detrended to remove the typical slow linear decrease of SCL as a function of relaxation time, and bandpass filtered with the same frequency range (0.01–0.12) as in typical rs-fcMRI analysis. Another consideration related to the frequency range selection is to overlap the known HRV, another important index of ANS activity (Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology, 1996). The power spectral density of HRV in the low-frequency (LF) range (0.04–0.15) and in the high-frequency range (0.15–0.40) corresponds to both sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. The power in the very LF range (<0.04) warrants further examination. Individual skin conductance time series during the resting-state scan were also examined and compared to the standardized SCR curve (Boucsein, 1992; Patterson et al., 2002; Bach et al., 2010) to identify and count the number of SCRs.

Coherence analysis.

Coherence analysis between the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) seed (see seed region definition in functional connectivity analysis) and SCR was also conducted to depict the nature of the correlation between this region of interest (ROI) and SCR. Both PCC time course and SCR were detrended before computing coherence using the mscohere function in Matlab (MathWorks) to estimate the magnitude squared coherence function. FFT length, which determines the frequencies at which the coherence is estimated, was 129; sampling frequency was 1/2.5 Hz; the number of samples to use for each section was 18; and the number of samples by which the sections overlapped was 9 (50%). Following Fisher's r-to-z transformation, the data points of magnitude squared coherence against frequency from each subject were averaged and were then transformed back to r.

Regression analysis.

General linear modeling (GLM) of the imaging data was conducted using statistical parametric mapping (SPM8; Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK). The EPI scans were realigned to the first volume, timing corrected, coregistered to the T2 image, normalized to a standard template [Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI)], and spatially smoothed with an 8 × 8 × 8 mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel. Timing correction of the scan was to the first slice which occurred at 0 s. However, the SCR was an average of the samples collected from time point 0 to 2.5 s. GLM (Friston et al., 1994) was then conducted with the SCR time series as a predictor of the observed BOLD signals. The regressor was not generated as in standard fMRI data analysis by convolving default SPM basis function with delta functions, because there was no sequence of individual events. Low-frequency drifts in signal were removed using a standard high-pass filter with a 128 s cutoff. Serial correlation was estimated using an autoregressive AR(1) model. Mean voxel value was used for global calculation and grand mean scaling was applied with global normalization to remove nonspecific noise (Van Dijk et al., 2010). Ventricle and white-matter signals were extracted using corresponding mask and entered as covariates. In addition, the six parameters generated during motion correction were also entered as covariates.

Subsequently, the relationship between SCR and BOLD was tested by employing a mixed effect model (Friston et al., 2005) implemented in SPM12 α (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging). The mixed effect model was used because unlike event-related fMRI, the number of the nonspecific SCRs could not be controlled; nonspecific SCRs varied considerably across subjects (mean = 5.8, SD = 5.7). The fixed-effect model was specified and estimated first using the data from all subjects. Then the mixed effect model was specified and estimated. The resultant voxelwise statistical maps were thresholded for significance using a cluster-size algorithm that protects against an inflation of the false-positive rate of multiple comparisons. An uncorrected p value of 0.05 for the height (intensity) threshold of each activated voxel and an extent threshold of k = 120 were used. A Monte Carlo simulation of the brain volume of the current study was conducted to establish an appropriate voxel contiguity threshold (Slotnick and Schacter, 2004). Assuming an individual voxel type I error of p < 0.05, a cluster extent of 120 contiguous resampled voxels (2 × 2 × 2 mm3) was indicated as necessary to correct for multiple voxel comparisons at p < 0.05. The same cluster-level threshold was applied to all contrasts. Statistical results were mapped onto the surface of the cerebral cortex.

Functional connectivity analysis.

Functional connectivity, operationally defined as simple correlations between activation of brain areas (Friston et al., 1997), was computed using the traditional correlation analysis of the time courses among brain regions (Koshino et al., 2005). For each subject, time series volumes of rs-fcMRI scan images were preprocessed using the Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State fMRI (DPARSF) toolbox (Chao-Gan and Yu-Feng, 2010). The analysis included slice timing correction, realignment (to the first volume), coregistration, normalization (to the MNI space with unified segmentation on T2 images), spatial smoothing (using a 8 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel), and detrending (to remove the systematic drift or trend) and temporal filtering [bandpass, 0.01∼0.12, based on coherence analysis, which is wider than 0.01∼0.08 (Biswal et al., 1995), to reduce the effect of low frequency drift and high frequency physiological signal or noise]. To examine the connectivity of the default mode network, the time course of the PCC (left and right combined) was extracted using the automated anatomical labeling template (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002). Then the resting-state fMRI data analysis toolkit (REST) (Song et al., 2011) was used to calculate the voxelwise linear correlation between the mean time course of the PCC and the time course of each voxel in the whole brain, with six head motion parameters, global mean signal, white-matter signal, and CSF signal as covariates. To explore the effect of SCR, the second voxelwise connectivity analysis was performed by adding the SCR as a covariate to regress out the SCR effect. The correlation coefficients were transformed using Fisher's r-to-z transformations. A paired t test was conducted between the functional connectivity of PCC before and after regressing out the SCR effect.

Psychophysiological interaction analysis.

Psychophysiological interaction (PPI) analysis was conducted, setting PCC as the seed region, to examine whether fluctuations in arousal (the psychological factor, reflected by SCR) modulate connectivity between PCC and other key regions [such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC)] in the RSNs. The raw spontaneous fluctuation (SF) wave of skin conductance was decimated to 10 Hz from an original sampling rate of 200 Hz, detrended to remove SCL change, and then zero-phase filtered with a bandpass filter of 0.01–0.40 Hz. The SCRalyze (version 2.1.6) package (Bach et al., 2009, 2010, 2011) was used to deconvolve the SCR signal, generating the onset and amplitude vectors of SCR. Because a fixed number of SCRs is assumed and only their amplitudes are estimated, the amplitude of “unnecessary” SFs is estimated to be close to zero. Events where the amplitude was below a threshold (in unit of μS, varied across subjects) were excluded. The onset and amplitude vectors were used in a second GLM using the amplitude vectors as the modulator of the onset stick of SCR, convolved with the hemodynamic response function, but not SCR function, prepared for the PPI analysis. All the covariates used in the first GLM were also used here for the second GLM and the following PPI analysis.

From the first-level analysis, the BOLD signal of the PCC ROI was extracted by using the PCC mask (as in previous functional connectivity analysis), and the PPI variables were created using the F contrast of the SCR regressor. SF amplitude was not included because it does not depend on tonic arousal, while the number of SFs does. GLM was conducted with PPI regressors of (1) interaction of PCC by SCR, (2) main effect of PCC, and (3) main effect of SCR, corresponding to PPI.ppi, PPI.Y, and PPI.P in the design matrix. Here PPI.P (SCR) was treated as the psychological factor. The second-level group data analysis was then conducted using the mixed-effect model. The threshold was the same as in the previous GLM analysis (individual voxel p < 0.05 and extent k > 120 voxels). The significantly activated regions may indicate that (1) the contribution of PCC to those regions is altered by the experimental (psychological) context (here it is the SCR that is related to arousal), or (2) the response of those regions to SCR due to the contribution of PCC.

Results

Coherence between the posterior cingulate cortex and SCR

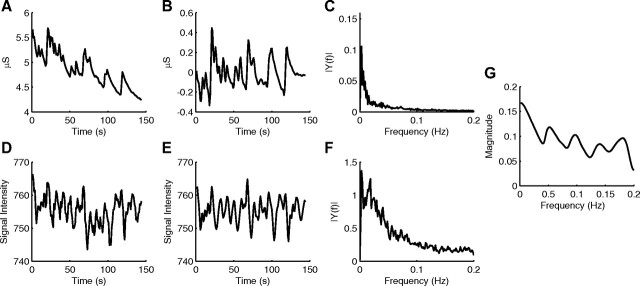

Because PCC is the key node of the DMN (Greicius et al., 2003), we first examined the time course of the PCC ROI and SCR (Fig. 1A,B,D,E, from a single subject). The averaged power spectral density showed that SCR and PCC time courses share the same frequency range (Fig. 1C,F, averaged across all subjects). Coherence analysis, to identify variations of the two signals with similar spectral properties, showed that the activity of the PCC ROI and SCR covary (Fig. 1G, averaged across all subjects). This indicates a potentially important relationship between spontaneous BOLD fluctuations of PCC and SCR activity. The pattern of coherence between BOLD signal of PCC and SCR may reflect the underlying control of the ANS by the DMN and/or TPN, or brain response to ANS activity.

Figure 1.

An example of SCR and PCC time courses from a single participant, along with frequency analyses of all subjects. A, Raw unfiltered skin conductance signal showing the nonspecific SCRs during rest from a single subject. B, Bandpass-filtered signal showing SCR curves after detrending of A. C, Average power spectral density of SCR signal for 15 subjects. D, PCC time course from a single subject. E, Bandpass-filtered and detrended PCC time course of D. F, Average power spectral density of PCC signal for 15 subjects. G, Averaged PCC-SCR coherence of 15 subjects.

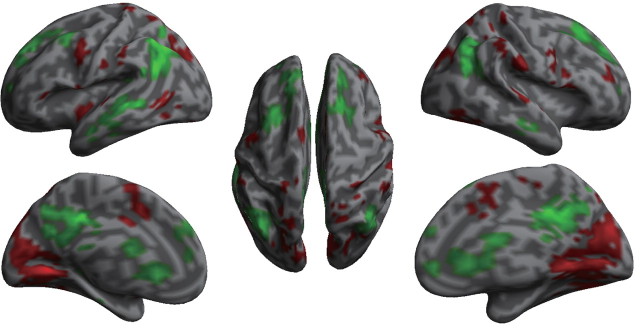

Brain activity as a function of nonspecific SCR

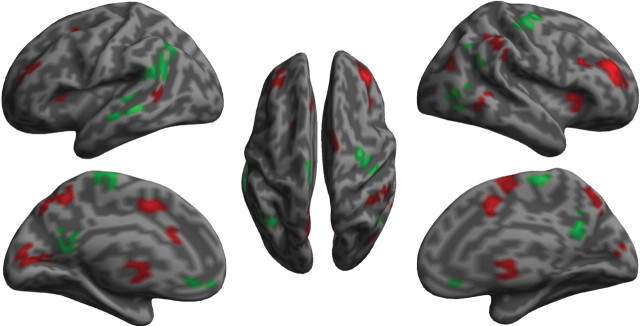

GLM showed that deactivation of the PCC (and precuneus) of DMN and activation of the ACC and AI of the TPN, were significantly correlated with nonspecific SCR (Fig. 2; Table 1). The activity of other regions of the DMN, such as subgenual ACC, and of the TPN, such as supplementary motor area, middle frontal gyrus, and inferior parietal lobule, also showed significant negative and positive correlations with SCR. More specifically, the findings indicate that increases in autonomic arousal relate to decreased DMN and increased TPN activity.

Figure 2.

Brain activation associated with nonspecific skin conductance response. The red color indicates voxels with positive relationships, while the green color indicates voxels with negative relationships.

Table 1.

Positive and negative correlation between SCR and brain activation

| Region | L/R | BA | MNI coordinates |

T | z | p | k | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||||

| Positive | |||||||||

| Cerebellum (VI) | L | −28 | −64 | −26 | 3.70 | 3.60 | 0.000 | 1992 | |

| Cerebellum (VI) | R | 20 | −58 | −20 | 3.14 | 3.07 | |||

| Vermis (IV) | −2 | −58 | −18 | 2.57 | 2.53 | ||||

| Cerebellum (I) | L | −38 | −48 | −32 | 2.41 | 2.38 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus | R | 46/10 | 40 | 42 | 24 | 3.34 | 3.26 | 0.001 | 591 |

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | R | 24 | 6 | 6 | 44 | 2.97 | 2.91 | 0.002 | 1358 |

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | L | 24 | −6 | 6 | 46 | 2.82 | 2.77 | ||

| Supplementary motor area | R | 6 | 8 | 2 | 68 | 2.49 | 2.45 | ||

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | L | 24 | −10 | 24 | 22 | 2.23 | 2.21 | ||

| Insula | L | −32 | 24 | 12 | 2.14 | 2.12 | |||

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | L | 24 | −2 | 26 | 22 | 2.08 | 2.06 | ||

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | L | 24 | 0 | 12 | 34 | 2.07 | 2.05 | ||

| Caudate nucleus | L | −20 | 2 | 24 | 2.06 | 2.05 | |||

| Calcarine cortex | L | 17/18 | −16 | −74 | 10 | 2.75 | 2.70 | 0.003 | 437 |

| Calcarine cortex | R | 17 | 6 | −80 | 8 | 1.88 | 1.87 | ||

| Middle frontal gyrus | L | 46 | −32 | 40 | 22 | 2.72 | 2.67 | 0.004 | 317 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | R | 45 | 34 | 20 | 22 | 2.64 | 2.6 | 0.005 | 515 |

| Insula | R | 30 | 20 | 6 | 2.57 | 2.54 | |||

| Caudate nucleus | R | 20 | 20 | 4 | 2.30 | 2.28 | |||

| Precuneus | L | 7 | −12 | −52 | 50 | 2.62 | 2.58 | 0.005 | 524 |

| Precuneus | R | 7 | 4 | −64 | 50 | 2.33 | 2.30 | ||

| Middle temporal gyrus | R | 21 | 56 | −50 | 4 | 2.59 | 2.55 | 0.005 | 153 |

| Cerebellum (VIII) | L | −28 | −58 | −50 | 2.57 | 2.53 | 0.006 | 107 | |

| Middle occipital gyrus | R | 19 | 38 | −68 | 26 | 2.53 | 2.50 | 0.006 | 144 |

| Cerebellum (VIII) | R | 12 | −36 | −50 | 2.52 | 2.48 | 0.006 | 386 | |

| Inferior parietal lobule | R | 40 | 34 | −40 | 54 | 2.44 | 2.41 | 0.008 | 400 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | R | 40 | 54 | −40 | 40 | 2.43 | 2.40 | ||

| Negative | |||||||||

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | 21 | −62 | −34 | 0 | 3.24 | 3.17 | 0.001 | 381 |

| Paracentral lobule | R | 4 | 4 | −26 | 64 | 3.18 | 3.11 | 0.001 | 453 |

| Paracentral lobule | L | 4 | −6 | −28 | 72 | 2.61 | 2.57 | ||

| Precentral gyrus | R | 4 | 40 | −18 | 56 | 3.08 | 3.02 | 0.001 | 335 |

| Postcentral gyrus | R | 6 | 34 | −28 | 68 | 1.86 | 1.85 | ||

| Precuneus/posterior cingulate gyrus | R | 23 | 8 | −56 | 28 | 2.92 | 2.87 | 0.002 | 407 |

| Precuneus | L | 23 | −2 | −58 | 20 | 2.35 | 2.32 | ||

| Precuneus | L | 30 | −6 | −54 | 14 | 2.32 | 2.29 | ||

| Gyrus rectus | R | 11 | 2 | 28 | −18 | 2.65 | 2.61 | 0.004 | 328 |

| Medial orbital gyrus | L | 11 | −2 | 52 | −12 | 2.48 | 2.45 | ||

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | L | 32 | −4 | 34 | −8 | 1.99 | 1.97 | ||

| Middle temporal gyrus | R | 37 | 46 | −68 | 6 | 2.64 | 2.6 | 0.005 | 164 |

| Inferior temporal gyrus | R | 19 | 46 | −68 | −6 | 2.16 | 2.14 | ||

| Superior temporal gyrus | L | 42 | −60 | −46 | 20 | 2.48 | 2.45 | 0.007 | 563 |

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | 21 | −50 | −54 | 22 | 2.37 | 2.35 | ||

| Angular gyrus | L | 40/39 | −36 | −58 | 38 | 2.2 | 2.18 | ||

| Superior temporal gyrus | R | 39 | 48 | −54 | 24 | 2.35 | 2.32 | 0.01 | 179 |

| Angular gyrus | R | 39 | 50 | −60 | 38 | 2.13 | 2.11 | ||

L, Left; R, right; BA, Brodmann's area. Height threshold: T = 1.66, p < 0.05; extent threshold: k = 120.

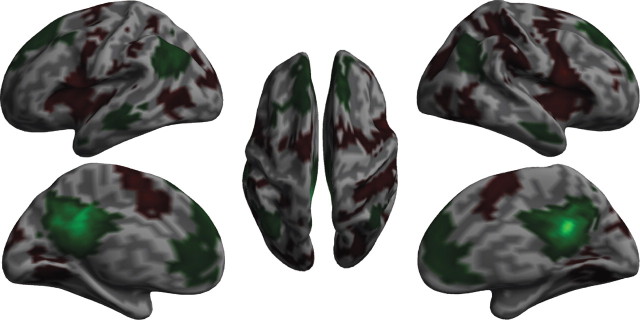

Functional connectivity change after regressing out SCR

Using PCC as the seed, the functional connectivity between the PCC and other brain regions showed a significant positive correlation with DMN and anticorrelation with TPN (Fig. 3; Table 2). The magnitude of the anticorrelation between PCC (of the DMN) and frontoparietal regions (of the TPN) was stronger before in contrast to after SCR was regressed out (Fig. 4; Table 3). There was also greater PCC connectivity with other regions in the DMN (especially the medial prefrontal cortex) when SCR was not regressed out. However, under SCR modeling, there was no significant change of connectivity between PCC and AI, indicating that the intrinsic anticorrelation was not significantly affected by SCR, although the amplitudes of both regions were negatively and positively correlated with SCR, as shown in GLM analyses.

Figure 3.

Connectivity between PCC and other brain regions without regressed out SCR-related brain activity. The green color indicates voxels with positive connectivity to PCC, while the red color indicates voxels with anticorrelated connectivity. p < 0.001 and k > 120 resampled voxel size thresholds were used to plot this figure.

Table 2.

One sample t test of the functional connectivity with PCC as the seed

| Region | L/R | BA | MNI coordinates |

T | z | P | k | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||||

| Positive | |||||||||

| Posterior cingulate gyrus | R | 31 | 4 | −46 | 26 | 44.75 | Inf | 0.000 | 30521 |

| Posterior cingulate gyrus | L | 31 | −10 | −46 | 32 | 26.91 | 7.36 | ||

| Precuneus | L | 7 | −4 | −62 | 34 | 22.13 | 6.99 | ||

| Precuneus | R | 23/7/31/29 | 8 | −58 | 28 | 17.22 | 6.50 | ||

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | 10 | 0 | 50 | −2 | 11.03 | 5.56 | |||

| Superior frontal gyrus (medial) | L | 9 | −4 | 44 | 44 | 9.59 | 5.24 | ||

| Superior frontal gyrus | R | 8/9/10 | 22 | 26 | 52 | 9.14 | 5.14 | ||

| Superior frontal gyrus (medial) | L | 8 | −2 | 34 | 56 | 9.07 | 5.12 | ||

| Superior frontal gyrus (medial) | 10/11/32 | 0 | 54 | 32 | 8.71 | 5.03 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (orbital) | R | 25/32 | 4 | 30 | −8 | 8.52 | 4.97 | ||

| Middle frontal gyrus | L | 8/9/10 | −20 | 26 | 48 | 7.44 | 4.66 | ||

| Superior frontal gyrus | L | 8/9/10 | −16 | 22 | 56 | 7.37 | 4.64 | ||

| Superior frontal gyrus (medial) | R | 8/9/10 | 10 | 46 | 40 | 7.27 | 4.61 | ||

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | R | 10/32 | 8 | 52 | 14 | 6.43 | 4.32 | ||

| Thalamus | R | 12 | −26 | 12 | 4.19 | 3.32 | |||

| Caudate nucleus | L | −12 | 8 | 14 | 3.66 | 3.02 | |||

| Medial orbital gyrus | L | 11/10 | −2 | 68 | −8 | 3.53 | 2.94 | ||

| Caudate nucleus | R | 10 | 4 | 14 | 3.39 | 2.85 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus | R | 9 | 46 | 22 | 50 | 3.32 | 2.81 | ||

| Hippocampus | L | −30 | −24 | −12 | 2.45 | 2.20 | |||

| Angular gyrus | R | 39/7 | 48 | −60 | 32 | 11.78 | 5.70 | 0.000 | 3052 |

| Superior parietal gyrus | R | 7 | 34 | −76 | 52 | 6.05 | 4.17 | ||

| Angular gyrus | L | 39 | −48 | −64 | 28 | 11.25 | 5.60 | 0.000 | 3671 |

| Middle occipital gyrus | L | 19 | −36 | −64 | 30 | 9.09 | 5.12 | ||

| Middle temporal gyrus | R | 21 | 64 | −4 | −16 | 8.63 | 5.01 | 0.000 | 2703 |

| Middle temporal pole | R | 21/38 | 56 | 10 | −28 | 5.99 | 4.15 | ||

| Inferior temporal gyrus | R | 20/37/20 | 66 | −12 | −28 | 4.28 | 3.37 | ||

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | 21 | −58 | −26 | −8 | 6.98 | 4.51 | 0.000 | 3177 |

| Temporal pole | L | 38 | −46 | 14 | −36 | 4.22 | 3.33 | ||

| Superior temporal pole | L | 38 | −50 | 20 | −24 | 3.08 | 2.65 | ||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | 47/11 | −28 | 28 | −22 | 2.80 | 2.45 | ||

| Inferior temporal gyrus | L | 20 | −64 | −48 | −20 | 2.78 | 2.44 | ||

| Cerebellum (II) | R | 24 | −84 | −36 | 5.23 | 3.83 | 0.000 | 2430 | |

| Cerebellum (I) | R | 40 | −54 | −40 | 4.68 | 3.57 | |||

| Vermis | 8 | −46 | −44 | 4.56 | 3.51 | 0.000 | 436 | ||

| Cerebellum (I) | L | −38 | −70 | −36 | 4.33 | 3.39 | 0.000 | 1166 | |

| Negative | |||||||||

| Rolandic operculum | R | 6/22 | 46 | 2 | 16 | 12.30 | 5.80 | 0.000 | 83763 |

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | L | 32/24 | −8 | 4 | 46 | 11.31 | 5.61 | ||

| Superior temporal gyrus | L | 38/41/42 | −52 | 8 | −4 | 10.77 | 5.50 | ||

| Supplementary motor area | L | 6 | −6 | −4 | 56 | 10.65 | 5.48 | ||

| Inferior frontal gyrus (opercular) | L | 44 | −56 | 10 | 10 | 9.75 | 5.28 | ||

| Cerebellum (VI) | L | −28 | −40 | −34 | 9.45 | 5.21 | |||

| Superior frontal gyrus | L | 6 | −22 | −6 | 68 | 9.13 | 5.13 | ||

| Precentral gyrus | R | 4/6 | 50 | 2 | 26 | 8.94 | 5.09 | ||

| Inferior frontal gyrus (triangular) | L | 45/46/47 | −34 | 28 | 0 | 8.88 | 5.07 | ||

| Precentral gyrus | L | 6 | −56 | 0 | 38 | 8.84 | 5.06 | ||

| Inferior parietal gyrus | R | 2/40 | 44 | −36 | 54 | 8.78 | 5.04 | ||

| Postcentral gyrus | R | 2/3 | 40 | −40 | 62 | 8.71 | 5.03 | ||

| Insula | R | 38 | 12 | 0 | 8.26 | 4.90 | |||

| Insula | L | −44 | −2 | −4 | 8.18 | 4.88 | |||

| Cuneus | L | 18 | −6 | −88 | 22 | 8.13 | 4.87 | ||

| Rolandic operculum | L | 6/22 | −40 | 2 | 16 | 8.12 | 4.86 | ||

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | 37 | −48 | −54 | −2 | 7.73 | 4.75 | ||

| Postcentral gyrus | L | 1/3/4/6 | −40 | −10 | 42 | 7.67 | 4.73 | ||

| Calcarine cortex | R | 17 | 24 | −58 | 6 | 7.29 | 4.61 | ||

| Superior occipital gyrus | R | 19/18/7 | 26 | −72 | 22 | 7.20 | 4.58 | ||

| Superior frontal gyrus | R | 6 | 24 | −4 | 66 | 7.04 | 4.53 | ||

| Cerebellum (VIII) | R | 30 | −56 | −54 | 6.82 | 4.46 | |||

| Cerebellum (VIII) | L | −24 | −62 | −54 | 6.69 | 4.41 | |||

| Superior occipital gyrus | L | 7/18/19 | −20 | −76 | 26 | 6.65 | 4.40 | ||

| Middle frontal gyrus | R | 8/9/10/46 | 40 | −6 | 58 | 6.64 | 4.39 | ||

| Middle occipital gyrus | L | 18/19 | −20 | −90 | 14 | 6.63 | 4.39 | ||

| Lingual gyrus | L | 19/18 | −18 | −64 | −4 | 6.59 | 4.38 | ||

| Putamen | R | 32 | 12 | 8 | 6.53 | 4.35 | |||

| Lingual gyrus | R | 18/19 | 16 | −60 | 2 | 6.48 | 4.33 | ||

| Inferior parietal gyrus | L | 2/40 | −58 | −28 | 50 | 6.31 | 4.27 | ||

| Supramarginal gyrus | R | 40/2 | 60 | −30 | 30 | 6.25 | 4.25 | ||

| Middle occipital gyrus | R | 19/18 | 26 | −84 | 18 | 5.94 | 4.13 | ||

| Superior parietal gyrus | L | 7/40 | −22 | −56 | 50 | 5.76 | 4.06 | ||

| Inferior occipital gyrus | R | 19 | 34 | −78 | −12 | 5.59 | 3.99 | ||

| Inferior frontal gyrus (orbital) | R | 11 | 20 | 38 | −16 | 5.52 | 3.96 | ||

| Fusiform gyrus | R | 37/20 | 24 | −78 | −4 | 5.29 | 3.86 | ||

| Superior parietal gyrus | R | 7 | 18 | −62 | 50 | 5.26 | 3.84 | ||

| Middle frontal gyrus | L | 10/9/46 | −40 | 50 | 28 | 5.15 | 3.79 | ||

| Superior temporal gyrus | R | 42/22 | 66 | −28 | 14 | 4.82 | 3.64 | ||

| Cerebellum (II) | L | −4 | −74 | −36 | 4.70 | 3.58 | |||

| Supramarginal gyrus | L | 2/40 | −58 | −32 | 38 | 4.67 | 3.57 | ||

| Middle temporal gyrus | R | 37 | 48 | −70 | 6 | 4.62 | 3.54 | ||

| Temporal pole | R | 36 | 30 | 6 | −40 | 4.37 | 3.41 | ||

| Cerebellum (IX) | L | −14 | −50 | −54 | 4.29 | 3.37 | |||

| Inferior temporal gyrus | L | 20/36/37 | −36 | −8 | −42 | 4.22 | 3.33 | ||

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | R | 32/24 | 14 | 5 | 47 | 4.17 | 3.31 | ||

| Parahippocampal gyrus | R | 34/36 | 18 | 2 | −20 | 4.11 | 3.28 | ||

| Precentral gyrus | R | 4 | 14 | −36 | 56 | 4.09 | 3.26 | ||

| Parahippocampus | L | 28 | −20 | 8 | −26 | 4.00 | 3.21 | ||

| Temporal pole (superior temporal gyrus) | L | 38 | −28 | 12 | −28 | 3.59 | 2.97 | ||

| Cerebellum (VI) | R | 26 | −64 | −22 | 3.56 | 2.96 | |||

| Cerebellum (II) | R | 6 | −74 | −36 | 3.52 | 2.93 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus | L | 19 | −36 | −80 | −4 | 3.35 | 2.83 | ||

| Medial orbital gyrus | L | 11 | −22 | 38 | −14 | 3.12 | 2.67 | ||

| Cerebellum (I) | R | 52 | −46 | −28 | 2.99 | 2.59 | |||

| Fusiform gyrus | L | 37/20 | −28 | −4 | −34 | 2.96 | 2.57 | ||

| Inferior frontal gyrus (orbital) | L | 11 | −12 | 20 | −18 | 2.88 | 2.51 | ||

| Inferior temporal gyrus | R | 20/37 | 42 | −10 | −36 | 2.75 | 2.42 | ||

| Precentral gyrus | L | 4 | −12 | −20 | 80 | 2.23 | 2.03 | ||

| Temporal pole (mid temporal gyrus) | L | 36 | −22 | 10 | −36 | 2.07 | 1.91 | ||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | R | 47 | 50 | 44 | −12 | 2.02 | 1.87 | ||

| Precuneus | R | 7 | 14 | −80 | 48 | 1.82 | 1.71 | ||

L, Left; R, right; BA, Brodmann's area. Height threshold: T = 1.76, p < 0.05; extent threshold: k = 120 voxels.

Figure 4.

The connectivity changes in default mode and other brain networks before and after regressing SCR out. The red color indicates voxels with decreased anticorrelated connectivity, while the green color indicates voxels with decreased positive connectivity with PCC after regressing out SCR.

Table 3.

PCC connectivity differences before and after SCR was regressed out

| Region | L/R | BA | MNI coordinates |

T | z | p | k | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||||

| After–before | |||||||||

| Superior temporal gyrus | L | 22 | −58 | −22 | 2 | 3.98 | 3.20 | 0.001 | 1368 |

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | 37/21 | −42 | −66 | 10 | 2.81 | 2.46 | ||

| Inferior temporal gyrus | L | 37 | −50 | −54 | −4 | 2.70 | 2.39 | ||

| Lingual gyrus | L | 19 | −24 | −66 | 0 | 2.31 | 2.10 | ||

| Hippocampus | L | −34 | −32 | −6 | 3.79 | 3.09 | 0.001 | 191 | |

| Hippocampus | L | −18 | −32 | 0 | 3.63 | 3.00 | 0.001 | 262 | |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | L | 30 | −14 | −44 | −10 | 2.94 | 2.55 | ||

| Inferior frontal gyrus (triangular) | L | 45 | −52 | 18 | 4 | 3.53 | 2.93 | 0.002 | 693 |

| Precentral gyrus | L | 6 | −50 | 6 | 20 | 3.03 | 2.61 | ||

| Inferior frontal gyrus (orbital) | L | 44 | −54 | 16 | 18 | 2.29 | 2.08 | ||

| Inferior parietal lobule | L | 40 | −34 | −36 | 32 | 3.52 | 2.93 | 0.002 | 261 |

| Superior temporal gyrus | R | 22/13 | 42 | −24 | −2 | 3.50 | 2.92 | 0.002 | 739 |

| Substantia nigra | L | −14 | −14 | −12 | 3.28 | 2.78 | 0.003 | 372 | |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | L | 36 | −16 | −6 | −30 | 3.19 | 2.72 | 0.003 | 145 |

| Inferior temporal gyrus | L | 20 | −52 | −38 | −20 | 3.18 | 2.71 | 0.003 | 145 |

| Insula | R | 30 | 12 | −18 | 3.10 | 2.66 | 0.004 | 156 | |

| Putamen | R | 30 | 12 | −6 | 2.25 | 2.05 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus | L | 46/9 | −46 | 34 | 36 | 2.10 | 1.93 | ||

| Middle occipital gyrus | L | 19 | −40 | −60 | 2 | 2.09 | 1.92 | ||

| Lingual gyrus | R | 19 | 16 | −40 | −12 | 3.09 | 2.65 | ||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | R | 45 | 50 | 24 | 20 | 3.06 | 2.64 | 0.004 | 457 |

| Orbital frontal gyrus | L | 11 | −22 | 32 | −14 | 3.03 | 2.61 | 0.005 | 172 |

| Superior temporal gyrus | L | 22 | −52 | −8 | −2 | 2.99 | 2.59 | 0.005 | 274 |

| Orbital frontal gyrus | L | 47 | −34 | 56 | −8 | 2.62 | 2.33 | 0.010 | 149 |

| Fusiform gyrus | R | 37 | 36 | −40 | −20 | 2.51 | 2.25 | 0.012 | 135 |

| Before–after | |||||||||

| Postcentral gyrus | R | 2 | 64 | 0 | 30 | 4.27 | 3.36 | 0.000 | 186 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | R | 6 | 14 | −8 | 76 | 4.06 | 3.25 | 0.001 | 150 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | L | 9 | −12 | 58 | 38 | 3.67 | 3.02 | 0.001 | 130 |

| Cerebellum (II) | L | −42 | −72 | −50 | 3.60 | 2.98 | 0.001 | 231 | |

| Precuneus | L | 31 | −10 | −44 | 44 | 3.42 | 2.87 | 0.002 | 540 |

| Precuneus | R | 7/31 | 6 | −52 | 42 | 2.81 | 2.46 | ||

| Posterior cingulate cortex | R | 31/23/29 | 2 | −40 | 20 | 2.17 | 1.98 | ||

| Cerebellum (VI) | R | 12 | −56 | −20 | 3.26 | 2.77 | 0.003 | 510 | |

| Cerebellum (II) | L | −22 | −84 | −32 | 3.2 | 2.73 | 0.003 | 439 | |

| Inferior occipital gyrus | R | 19 | 34 | −90 | −10 | 3.05 | 2.63 | 0.004 | 378 |

| Precuneus | L | 5 | −12 | −40 | 60 | 3.15 | 2.69 | 0.004 | 175 |

| Postcentral gyrus | L | 3 | −24 | −36 | 58 | 2.88 | 2.51 | ||

| Postcentral gyrus | R | 2 | 26 | −48 | 56 | 3.08 | 2.64 | 0.004 | 245 |

| Superior parietal lobule | R | 7 | 24 | −64 | 56 | 2.64 | 2.34 | ||

| Supplementary motor area | L | 6 | −8 | −2 | 52 | 2.73 | 2.41 | 0.008 | 123 |

| Superior parietal lobule | L | 7 | −18 | −64 | 58 | 2.93 | 2.55 | 0.005 | 127 |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | L | 36 | −16 | −16 | −30 | 2.91 | 2.53 | 0.006 | 132 |

| Superior frontal gyrus (Medial) | R | 9 | 8 | 56 | 46 | 2.91 | 2.53 | 0.006 | 120 |

| Superior frontal gyrus (Medial) | R | 8 | 6 | 38 | 60 | 2.88 | 2.51 | 0.006 | 130 |

| Posterior cingulate gyrus | R | 23 | 8 | −28 | 28 | 2.67 | 2.36 | 0.009 | 138 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | R | 47 | 38 | 24 | −14 | 2.40 | 2.16 | 0.015 | 133 |

| Insula | R | 32 | 30 | −2 | 2.00 | 1.85 | |||

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | R | 24 | 4 | 38 | 18 | 2.39 | 2.15 | 0.016 | 216 |

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | R | 32 | 2 | 40 | 26 | 1.86 | 1.74 | ||

L, Left; R, right; BA, Brodmann's area. Height threshold: T = 1.76, p < 0.05; extent threshold: k = 120 voxels.

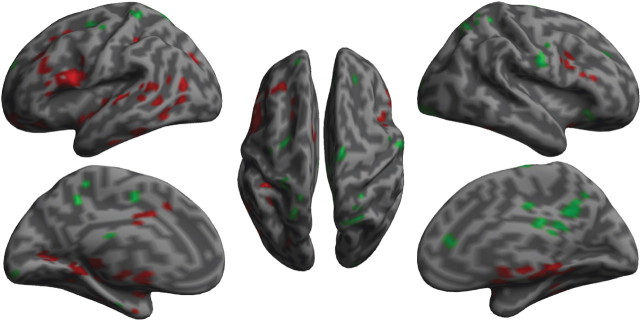

Psychophysiological interaction

Treating arousal (indexed by SCR) as the psychological context and using the BOLD signal of PCC as the physiological signal, the PPI analysis showed an enhanced positive connectivity between PCC and other brain regions in the DMN (e.g., vmPFC and PCC itself; Fig. 5, regions in green; Table 4), as well as an enhanced anticorrelation between PCC and regions in the TPN (e.g., ACC, precentral gyrus, areas near/along intraparietal sulcus). These findings are consistent with our functional connectivity analysis using the classic rs-fcMRI analytic method (Fox et al., 2005). The intrinsic connectivity between PCC and AI was not significantly modulated. Interestingly, the anticorrelation between PCC and visual cortex was significantly enhanced by SCR.

Figure 5.

Psychophysiological interaction (PPI) analysis results. Regions in green indicate that the contribution of PCC to those regions is increased by SCR, or the response of those regions to SCR is increased due to the contribution of PCC. Regions in red indicate an enhanced anticorrelation between PCC and these regions by SCR.

Table 4.

Positive and negative psychophysiological interaction

| Region | L/R | BA | MNI coordinates |

T | z | p | k | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||||

| Positive | |||||||||

| Angular gyrus | L | 39 | −42 | −64 | 46 | 4.69 | 4.53 | 0.000 | 8187 |

| Posterior cingulate gyrus | 23 | 0 | −34 | 40 | 4.56 | 4.41 | |||

| Angular gyrus | R | 39 | 42 | −62 | 36 | 4.51 | 4.36 | ||

| Posterior cingulate gyrus | L | 23 | −6 | −40 | 40 | 4.31 | 4.18 | ||

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | 21 | −52 | −58 | 22 | 4.13 | 4.02 | ||

| Posterior cingulate gyrus | R | 23 | 12 | −46 | 36 | 3.95 | 3.85 | ||

| Precuneus | L | 7 | −4 | −58 | 36 | 3.89 | 3.79 | ||

| Middle temporal gyrus | R | 21 | 50 | −56 | 20 | 3.47 | 3.40 | ||

| Superior frontal gyrus | L | 8 | −18 | 40 | 38 | 3.95 | 3.85 | 0.000 | 2033 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | L | 6 | −34 | 8 | 50 | 3.77 | 3.68 | ||

| Superior frontal gyrus | L | 9 | −16 | 42 | 30 | 3.55 | 3.47 | ||

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | 21 | −52 | −36 | −4 | 3.42 | 3.35 | 0.000 | 888 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | R | 8 | 22 | 24 | 48 | 3.10 | 3.05 | 0.001 | 3228 |

| Middle frontal gyrus (orbital) | R | 10 | 8 | 50 | −2 | 2.82 | 2.78 | ||

| Anterior cingulate gyrus (pregenu) | R | 32 | 4 | 38 | 0 | 2.17 | 2.15 | ||

| Middle temporal gyrus | R | 21 | 66 | −10 | −14 | 2.79 | 2.76 | 0.003 | 324 |

| Brainstem | L | −10 | −28 | −30 | 2.18 | 2.16 | 0.015 | 223 | |

| Negative | |||||||||

| Lingual gyrus | L | 18 | −8 | −62 | −2 | 4.26 | 4.14 | 0.000 | 8536 |

| Lingual gyrus | R | 18 | 22 | −68 | −12 | 3.80 | 3.71 | ||

| Fusiform gyrus | L | 37 | −26 | −56 | −18 | 3.30 | 3.24 | ||

| Cuneus | R | 18 | 6 | −78 | 26 | 3.29 | 3.23 | ||

| Lingual gyrus | R | 19 | 18 | −50 | 2 | 3.24 | 3.18 | ||

| Calcarine cortex | R | 17 | 16 | −66 | 18 | 3.23 | 3.17 | ||

| Cuneus | L | 18 | −6 | −90 | 28 | 3.15 | 3.10 | ||

| Middle occipital gyrus | L | 19 | −26 | −80 | 30 | 3.04 | 2.99 | ||

| Calcarine cortex | L | 18 | −2 | −86 | 10 | 2.94 | 2.90 | ||

| Thalamus | L | −10 | −20 | 6 | 3.66 | 3.57 | 0.000 | 124 | |

| Supplementary motor area | R | 6 | 2 | 10 | 58 | 3.63 | 3.55 | 0.000 | 1430 |

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | L | 24 | −6 | 0 | 38 | 3.06 | 3.01 | ||

| Anterior cingulate gyrus | R | 24 | 6 | 10 | 42 | 2.69 | 2.65 | ||

| Paracentral lobule | R | 4 | 4 | −30 | 56 | 2.39 | 2.37 | ||

| Superior parietal lobule | L | 7 | −20 | −60 | 54 | 3.41 | 3.35 | 0.000 | 247 |

| Precentral gyrus | L | 6 | −48 | 2 | 34 | 3.41 | 3.34 | 0.000 | 423 |

| Inferior temporal gyrus | L | 37 | −50 | −66 | −8 | 3.34 | 3.28 | 0.001 | 260 |

| Superior parietal lobule | R | 7 | 20 | −58 | 54 | 3.19 | 3.13 | 0.001 | 591 |

| Postcentral gyrus | R | 2 | 32 | −42 | 64 | 3.02 | 2.97 | ||

| Supramarginal gyrus | R | 2/40 | 60 | −18 | 26 | 2.95 | 2.91 | 0.002 | 1094 |

| Superior temporal gyrus | R | 22 | 62 | −12 | 4 | 2.57 | 2.54 | ||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | R | 44 | 48 | 6 | 24 | 2.46 | 2.43 | ||

| Middle frontal gyrus | R | 46 | 40 | 46 | 28 | 2.94 | 2.90 | 0.002 | 202 |

| Postcentral gyrus | L | 1 | −18 | −30 | 72 | 2.92 | 2.88 | 0.002 | 172 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | L | 1 | −58 | −26 | 50 | 2.77 | 2.73 | 0.003 | 350 |

| Lenticular nucleus | L | −24 | 4 | −12 | 2.74 | 2.70 | 0.003 | 228 | |

| Insula | L | −36 | −8 | −6 | 2.73 | 2.69 | |||

| Superior temporal gyrus | L | 22 | −52 | 16 | −10 | 2.70 | 2.66 | 0.004 | 326 |

| Caudate nucleus | R | 16 | 2 | 12 | 2.68 | 2.65 | 0.004 | 198 | |

L, Left; R, right; BA, Brodmann's area. Height threshold: T = 1.65, p < 0.05; extent threshold: k = 120.

Discussion

Although complex approaches have been used to examine the functional fractionation of the DMN (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2010), and RSNs more generally (Deco et al., 2011), task-based comparisons to spontaneous resting activity (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2010) and computational simulations (Deco et al., 2011) cannot provide an objective index of mental state during rest. This limitation raises questions about possible psychological processes that may relate and/or contribute to RSN activity and connectivity. Some more popular hypotheses about the functional basis of RSNs have included the generation of spontaneous thoughts (Mason et al., 2007) and self-relevant mental simulations (Buckner et al., 2008), as well as predictions about and preparation for environmental demands (Deco et al., 2011). Previous associations of SCR with the TPN suggest that SCR has some putative contributions to consciousness and bodily awareness/interoception (Craig, 2009). Thus SCR, in relation to spontaneous brain activity, is an excellent index of homeostatic monitoring, some of which may be conscious. In addition to being a good index of autonomic activity, the nonspecific SCRs during “rest” (in contrast to the specific SCR related to a stimulus) occur about 1–3 times per minute (Boucsein, 1992), an oscillation occurring within the typically used filter band of 0.01–0.08 Hz for rs-fcMRI analysis (Biswal et al., 1995).

Our findings suggest that autonomic arousal, and the bodily and psychophysiological states that it reflects, have a critical relationship to the intrinsic properties of RSNs. Combinations of physiological recording and neuroimaging have not only permitted scientists to index emotion objectively, but also to identify the relationships between bodily arousal, brain activity, and possibly mental states (Harrison et al., 2010). With a few key exceptions (e.g., affective neuroscience), psychophysiological measures are most commonly used as a means to remove noise from the brain's signal in neuroimaging methodology (Critchley et al., 2011). In contrast to the usual effort to exclude psychophysiological measures from the brain activity as noise, we present evidence that general ANS activity is significantly related to spontaneous BOLD activity. The fact that activity of the key nodes of the DMN and the anticorrelated TPN is associated with SCR suggests that a significant portion of RSN activity may be linked to monitoring internal bodily and psychophysiological states (Thompson and Varela, 2001; Craig, 2002, 2009).

Previous associations of SCR with the AI and ACC have led some to conclude that activity of DMN and TPN may reflect a dynamic relationship between externally and internally (especially in relation to interoception) focused attention (Critchley et al., 2011). The AI integrates high-order cognitive, sensory, and interoceptive signals, contributing to the conditions of core affective feeling and/or subjective awareness (Craig, 2009). The ACC, in direct coupling with the AI, functions to implement neurobehavioral responses consistent with subjective experience (Medford and Critchley, 2010). The AI and ACC are also implicated in the monitoring and control, respectively, of autonomic activity (Critchley et al., 2011). Thus, the observed positive correlation between SCR and the TPN, as well as the decrease in PCC connectivity after SCR-related activity is removed (i.e., identified as noise), suggest increased attentional coupling with interoception during rest. When external demands are limited, it seems that spontaneous activity of the brain, in part, may function to increase processing (both unconscious and conscious) of the state of the body. In contrast to approaches that consider bodily processes as noise in relation to activity of the brain, our findings provide support for an embodied mind (Thompson and Varela, 2001), a view that necessitates recognition of a dynamic relationship among mental states, bodily functions, and brain processes (Thompson and Varela, 2001; Harrison et al., 2010; Critchley et al., 2011; Deco et al., 2011).

The idea that limited external demands may increase focus on internal bodily processes and psychophysiological state is somewhat consistent with a previous examination of SCR and task-related brain activity (Patterson et al., 2002). However, SCR may not reflect a single physiological or psychological process (Boucsein, 1992; Critchley, 2002). Patterson et al. (2002) have previously shown that changes in SCR are correlated with activation of DMN regions (e.g., vmPFC) that influence the sympathetic nervous system, independent of the tasks being performed. Consistent with their overall theory, our findings further showed that decreased activation and enhanced connectivity of vmPFC and PCC in DMN and activation of ACC/AI in TPN are related to SCR. The broad involvement of brain regions/networks suggests that SCR may reflect a multifaceted psychophysiological response and interaction. Given the present findings, along with others that suggest that autonomic activity can impact RSNs (Shmueli et al., 2007), as well as the potential relationship between autonomic activity and consciousness, important contributions from the body and mind to RSNs are potentially being overlooked in current analyses of spontaneous fluctuations of the brain.

Although we speculate that bodily arousal shapes neural responses of the RSN, it is also possible that activity of this network produces the arousal changes themselves, or a third factor, such as cognitive processes, drives both. Given that our methods are correlational, this question could not be answered in the current study and calls for further investigation. However, the present results may have implications for existing resting-state studies that have not taken arousal into account, especially those that compare DMN across health and disease states. For example, the abnormal connectivity patterns of DMN in patients with autism spectrum disorders might be related to deficits of ANS, creating the classic third variable problem.

There is also the possibility that motion is a contributing variable (i.e., motion may be a factor in some presently observed patterns). Our findings on this issue were mixed. In GLM, after the motion-related effects were regressed out (using the six motion correction parameters in the modeling), there was no activation associated with SCR in the precentral gyrus. Actually, SCR was negatively correlated with the activation of precentral gyrus and positively correlated with activation of the caudate, indicating the possibility of motor inhibition. However, our PPI analysis showed an enhanced anticorrelation between PCC and motor areas, which may suggest a contribution of motion, though it may also reflect top-down control.

At the very least, our findings, along with the findings of others (Shmueli et al., 2007; Birn et al., 2008), suggest considerable benefit of measuring and incorporating (rather than excluding) psychophysiological signals (especially ANS activity) in rs-fcMRI and fMRI. There are likely numerous sources driving the spontaneous fluctuations of the brain, some of which undoubtedly relate to neural activity (Mantini et al., 2007) and anatomical structure (Honey et al., 2009). However, methods which exclude signals from the body (Birn et al., 2008; Chang and Glover, 2009; Iacovella and Hasson, 2011), or rely mostly on reverse inference (Deco et al., 2011), are limiting the means by which we can understand the causal and functional basis of RSNs. SCR is not the only, nor necessarily the best, means to index psychophysiological states (Critchley et al., 2011). Although the present findings suggest an important role of the ANS in RSNs, the ANS has both sensory (afferent) and motor (efferent) subsystems, which are difficult to tease apart (Harrison et al., 2010). Further, SCR is but one of a variety of measures (e.g., electrodermal, cardiovascular, and blood pressure responses) to assess ANS activity. Given the ability of SCR to predict RSN activity, inclusion of multiple physiological measures may increase the amount of RSN variance that can be predicted. Using pattern classification analysis with multiple physiological indices may also help to identify the probable psychophysiological states of the subject during rest (Stephens et al., 2010). Such a program of research could provide important insight into the sources and functions of RSNs.

Finally, we would be remiss to ignore some additional questions raised by our findings. There are multiple factors that may underlie the pattern of correlations between SCR and rs-fcMRI, such as autonomic arousal, interoceptive awareness, volitional and cognitive intent, and perhaps others. A simplistic explanation for the present association between SCR fluctuations and the TPN may have to do with suppression of natural urges during rest. ACC and AI have previously been shown to help control and suppress spontaneous blinking (Lerner et al., 2009). Thus, our findings may simply reflect participants' efforts to remain still during the resting task. Even if true, this conclusion would still suggest a relation between physiological states during rest and the correlational patterns of RSNs. Alternatively, the present findings may relate to the emergence of subjective awareness, in part related to interoception, and subsequent implementation of consistent neurobehavioral responses (Medford and Critchley, 2010). If true, the latter explanation would relate to empirical evidence that the brain is one part of a dynamic homeostatic system, which includes the body and its environmental context (Thompson and Varela, 2001). This evidence advocates not only for more inclusive and objective means to measure the functional role of and contributions to RSNs, but also for consideration of the mind/brain/body relationship, both in the context of RSNs and in cognitive neuroscience more generally.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R21MH083164 and R01MH094305, and two Research Enhancement Awards from Queens College, City University of New York (to J.F.), Ministry of Science and Technology (973 Program, 2011CB711000) to Y.L., along with the National Center for Research Resources Grant UL1 RR029887 and James S. McDonnell Foundation Grant 22002078 (to P.R.H.). The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the aforementioned funding agencies. We thank Michael I. Posner, Evan Thompson, and Richard Bodnar for comments on earlier versions of the manuscript; and Xun Liu, Yunsoo Park, and Kevin Guise for help with data collection.

References

- Andrews-Hanna JR, Reidler JS, Sepulcre J, Poulin R, Buckner RL. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain's default network. Neuron. 2010;65:550–562. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach DR, Flandin G, Friston KJ, Dolan RJ. Time-series analysis for rapid event-related skin conductance responses. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;184:224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach DR, Flandin G, Friston KJ, Dolan RJ. Modelling event-related skin conductance responses. Int J Psychophysiol. 2010;75:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach DR, Daunizeau J, Kuelzow N, Friston KJ, Dolan RJ. Dynamic causal modeling of spontaneous fluctuations in skin conductance. Psychophysiology. 2011;48:252–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birn RM, Murphy K, Bandettini PA. The effect of respiration variations on independent component analysis results of resting state functional connectivity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2008;29:740–750. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucsein W. Electrodermal activity. New York: Plenum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain's default network—anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Glover GH. Effects of model-based physiological noise correction on default mode network anti-correlations and correlations. Neuroimage. 2009;47:1448–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao-Gan Y, Yu-Feng Z. DPARSF: a MATLAB toolbox for “pipeline” data analysis of resting-state fMRI. Front Syst Neurosci. 2010;4:13. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:655–666. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. How do you feel–now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD. Electrodermal responses: what happens in the brain. Neuroscientist. 2002;8:132–142. doi: 10.1177/107385840200800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Nagai Y, Gray MA, Mathias CJ. Dissecting axes of autonomic control in humans: insights from neuroimaging. Auton Neurosci. 2011;161:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deco G, Jirsa VK, McIntosh AR. Emerging concepts for the dynamical organization of resting-state activity in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Worsley KJ, Poline J-P, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ. Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: a general linear approach. Hum Brain Mapp. 1994;2:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Buechel C, Fink GR, Morris J, Rolls E, Dolan RJ. Psychophysiological and modulatory interactions in neuroimaging. Neuroimage. 1997;6:218–229. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Stephan KE, Lund TE, Morcom A, Kiebel S. Mixed-effects and fMRI studies. Neuroimage. 2005;24:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:253–258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison NA, Gray MA, Gianaros PJ, Critchley HD. The embodiment of emotional feelings in the brain. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12878–12884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1725-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey CJ, Sporns O, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, Thiran JP, Meuli R, Hagmann P. Predicting human resting-state functional connectivity from structural connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2035–2040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811168106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacovella V, Hasson U. The relationship between BOLD signal and autonomic nervous system functions: implications for processing of “physiological noise.”. Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;29:1338–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshino H, Carpenter PA, Minshew NJ, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Just MA. Functional connectivity in an fMRI working memory task in high-functioning autism. Neuroimage. 2005;24:810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner A, Bagic A, Hanakawa T, Boudreau EA, Pagan F, Mari Z, Bara-Jimenez W, Aksu M, Sato S, Murphy DL, Hallett M. Involvement of insula and cingulate cortices in control and suppression of natural urges. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:218–223. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK, Pauls J, Augath M, Trinath T, Oeltermann A. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature. 2001;412:150–157. doi: 10.1038/35084005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantini D, Perrucci MG, Del Gratta C, Romani GL, Corbetta M. Electrophysiological signatures of resting state networks in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13170–13175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700668104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MF, Norton MI, Van Horn JD, Wegner DM, Grafton ST, Macrae CN. Wandering minds: the default network and stimulus-independent thought. Science. 2007;315:393–395. doi: 10.1126/science.1131295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medford N, Critchley HD. Conjoint activity of anterior insular and anterior cingulate cortex: awareness and response. Brain Structure and Function. 2010;214:535–549. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0265-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JC, 2nd, Ungerleider LG, Bandettini PA. Task-independent functional brain activity correlation with skin conductance changes: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1797–1806. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA. Inferring mental states from neuroimaging data: from reverse inference to large-scale decoding. Neuron. 2011;72:692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter S, Singer JE. Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychol Rev. 1962;69:379–399. doi: 10.1037/h0046234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli K, van Gelderen P, de Zwart JA, Horovitz SG, Fukunaga M, Jansma JM, Duyn JH. Low-frequency fluctuations in the cardiac rate as a source of variance in the resting-state fMRI BOLD signal. Neuroimage. 2007;38:306–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotnick SD, Schacter DL. A sensory signature that distinguishes true from false memories. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:664–672. doi: 10.1038/nn1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song XW, Dong ZY, Long XY, Li SF, Zuo XN, Zhu CZ, He Y, Yan CG, Zang YF. REST: a toolkit for resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging data processing. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens CL, Christie IC, Friedman BH. Autonomic specificity of basic emotions: evidence from pattern classification and cluster analysis. Biol Psychol. 2010;84:463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:354–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson E, Varela FJ. Radical embodiment: neural dynamics and consciousness. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001;5:418–425. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01750-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk KR, Hedden T, Venkataraman A, Evans KC, Lazar SW, Buckner RL. Intrinsic functional connectivity as a tool for human connectomics: theory, properties, and optimization. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:297–321. doi: 10.1152/jn.00783.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]