Abstract

Background

Mexican immigrants in the US do not have increased risk for alcohol use or alcohol use disorders when compared to Mexicans living in Mexico, but they are at higher risk for drug use and drug use disorders. It has been suggested that both availability and social norms are associated with these findings. We aimed to study whether the opportunity for alcohol and drug use, an indirect measure of substance availability, determines differences in first substance use among people of Mexican origin in both the US and Mexico, accounting for gender and age of immigration.

Methods

Data come from nationally representative surveys in the United States (2001–2003) and Mexico (2001–2002) (combined n=3,432). We used discrete time proportional hazards event history models to account for time-varying and time-invariant characteristics. The reference group was Mexicans living in Mexico without migration experience.

Results

Female immigrants were at lower risk of having opportunities to use alcohol if they immigrated after the age of 13, but at higher risk if they immigrated prior to this age. Male immigrants showed no differences in opportunity to use alcohol or alcohol use after having the opportunity. Immigration was associated with having drugs opportunities for both sexes, with larger risk among females. Migration was also associated with greater risk of using drugs after having the opportunity, but only significantly for males.

Conclusions

The impacts of immigration on substance use opportunities are more important for drugs than alcohol. Public health messages and educational efforts should heed this distinction.

Keywords: substance use opportunity, migration, Mexican-American population, alcohol, drugs

1. Introduction

Burnam (Burnam et al., 1987) first showed that US born nationals of Mexican ancestry have higher rates of substance use disorders when compared to immigrants of Mexican origin. Further studies have confirmed these findings (Alegria et al., 2006; Breslau et al., 2007; Grant et al., 2004; Ortega et al., 2000; Vega et al., 1998a). Whether Mexican immigrants in the US, compared to nationals in their home country, have higher rates of substance use and substance use disorders because of the immigration process is a matter of debate. The scant research in this area suggests that compared to Mexican nationals living in Mexico, Mexican immigrants face an increased likelihood of drug use and drug use disorders, but contradictory results have been reported for alcohol use and alcohol use disorders (Borges et al., 2011, 2006; Caetano and Medina-Mora, 1988).

The alleged differential impact of immigration on alcohol and drugs among immigrants reported previously (Borges et al., 2011) is puzzling. Two factors may be involved (Babor et al., 2003), substance availability (i.e, the likelihood that one will come into contact with alcohol and drugs in a society (Stockwell and Gruenewald, 2001)) and social norms on alcohol and drug use (i.e., the proscriptive and prescriptive, correct use of substances in a given society; Hawks et al., 2002). One way to better understand the contribution of changes in availability and in social norms to the rates of substance use in immigrants is to differentiate risk for substance use opportunity (or chance to try a substance, an indirect measure of substance availability; Anthony, 2002) from risk for substance use given the opportunity. In a place where a substance is not available, there is no opportunity to be offered the substance and thus no further substance use. Exposure to the opportunity to use drugs is a necessary stage along the path to initiation of drug use (Wagner and Anthony, 2002) that may be directly targeted through demand control policies in the US (Van Etten and Anthony, 1999) and Mexico (Benjet et al., 2007b). If immigrants have a greater risk of exposure to substance use opportunities than non-immigrant nationals, but do not have a greater risk of use given the opportunity, we can deduce that changes in substance use are due to greater availability; on the other hand if immigrants have a similar exposure to substance use opportunities, but a greater risk of use given the opportunity we can deduce that changes in norms (or other factors such as immigration stress) primarily contribute to the increase in substance use. If immigrants have both increased risk of substance use opportunities and of use given the opportunity then we can assume both factors play a substantial role.

Social norms are more tolerant for alcohol use in Mexico than in the US, with binge and public drinking widely accepted in Mexico (World Health Organization, 2004). On the other hand, the availability of alcohol may not differ between countries, and may even be higher in Mexico for youth due to differences in the legal drinking age and differential enforcement of laws to prohibit underage drinking and sales to minors (Lange et al., 2002). The availability of drugs is higher in the US than in Mexico (UNODC, 2011), with lifetime prevalence of cannabis and cocaine use reaching 7.8% and 4.0% in Mexico while in the US it was 42.4% and 16.2% (Degenhardt et al., 2008) and norms regarding drug use are also more tolerant in the US, with “strong proscriptive norms against illicit drug use and high levels of protective factors (family stability and cohesiveness)” in Latin American countries such as Mexico (Canino et al., 2008, p.71).

Gender differences in opportunities to use substances may also help explain sex differences regarding the impact of immigration on drug use (Van Etten and Anthony, 2001; Wells et al., 2011). That US nativity and acculturation is associated to increased substance use and substance use disorders for females of Mexican origin more so than males of Mexican origin, has been known in the field (Zemore, 2007). Nevertheless, possible sex differences in alcohol and drug use comparing Mexican immigrants to Mexican nationals with no migration history have not been formally investigated. Finally, it can be argued that exposure opportunities for immigrants are very dependent on early socialization experiences. To account for early immigration experiences, we followed prior work by dividing the immigrants into those who arrived in the US at age 13 or older and those who arrived at age 12 or younger (Borges et al., 2011).

We aimed to study whether the opportunity for alcohol and drug use, an indirect measure of substance availability, determines differences in first substance use among people of Mexican origin in both the US and Mexico. Additionally we explore the differential effect by gender and by age of immigration as those who migrate up to age 12 will have early socialization experiences more similar to the US population while those who migrate after age 12 have early socialization experiences more similar to the Mexican population. Our main hypotheses are that the opportunity to use alcohol will be similar for Mexican male immigrants in the US when compared to Mexican males living in Mexico, but the opportunity to use drugs will be higher among immigrant males. For females, opportunities for using both alcohol and drugs will be higher among immigrants compared to Mexican females in Mexico. Alcohol and drug use, following exposure opportunity, is hypothesized to be equal for immigrants compared to Mexicans in Mexico, with no gender effect as reported in prior publications (Van Etten and Anthony, 2001; Wells et al., 2011).

2. Methods

2.1 Samples

We combined data on the Mexican population from the Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS; Medina-Mora et al., 2003) with data on the Mexican-origin population in the United States from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES; Heeringa et al., 2004) using the same methodology than in previous studies (Borges et al., 2011). The total sample size for our analyses was 3,432 persons. Of these, 2,878 are from the MNCS. The CPES respondents include 66 respondents from the NCSR and 488 respondents from the NLAAS. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Harvard Medical School, the University of Michigan, and the National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente.

Migration Groups

For this paper, we focus only on three mutually exclusive groups of interest across this transnational population: 1) Non-migrants in Mexico with no migrant in their family; 2) Mexican-born immigrants in the US who arrived at age 13 or older (1st generation); 3) Mexican-born immigrants in the US who arrived at age 12 or younger (1.5 generation). The first group is from the MNCS and the next two groups from the CPES population. The decision to use this cutoff for age at migration was made based on previous research we had performed on immigration and risk for psychiatric and substance use disorders (Breslau et al., 2007), where the statistical significance of the difference in risk for disorder between early- and late-arriving immigrants was maximized with this cutoff.

2.2 Measures

Assessment of substance use and opportunities to use

The WMH computer assisted version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Kessler and Üstün, 2004) was administered. The substance use section includes questions regarding the lifetime use (defined as consumption of the substance at least once at any time in one’s life) of illicit drugs and opportunity to use drugs. The substances included were marijuana, cocaine in any of its presentations, sedatives or stimulants used without a medical prescription such as methamphetamine, and other substances (e.g., heroin, inhalants, LSD, etc.) which were grouped as “other drugs.” Participants were asked about each category of drugs openly and then presented with a list of numerous different street names for these drugs.

The question regarding opportunity to use drugs was posed after the questions about drug use such that opportunities to use drugs referred to all the drugs previously presented to the respondents. Opportunity to use illicit drugs was defined as having the opportunity to use any type of illicit drug independently of whether or not the respondent did so. For example, someone offered the respondent drugs or the respondent was present when others were consuming and could have done so if he or she chose to. The respondents were asked the age of their first opportunity to use, the age of onset of drug use and the number of opportunities to use before first use. Retrospective ages of onset (AOO) were obtained using a series of questions designed to avoid implausible response patterns. First, a question aimed at obtaining the exact age of onset was asked. If unable to report the exact age, subsequent questions probed for approximate ages in ascending order using anchoring events or stages such as grade in school. A series of parallel questions were also asked for lifetime alcohol use (>12 drinks per year) and first opportunity to use alcohol.

2.3 Assessment of socio-demographic correlates

Other Covariates

Analyses also used sociodemographic information collected in the WMH-CIDI on gender, age, educational attainment, and marital status.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

To describe and compare sex and migration group specific estimates of the prevalence and timing of initial opportunity for, and subsequent initiation of drug and of alcohol use, we used standard survey data analysis procedures so that point and variance estimates and hypothesis tests properly accounted both for design effects arising from the use of stratification, clustering and unequal selection probabilities in the component surveys and for the restriction of the present analysis to the three migration groups (subdomains) of interest (Korn and Graubard, 1999). Since the CPES is comprised of two surveys with partially overlapping sampling frames, the NCSR and the NLAAS, CPES statisticians developed integrated weights so that the samples could be combined to jointly represent the total of 15.76 million Mexican- Americans in the US sampling frame (Heeringa and Berglund, 2007; National Institute of Mental Health, 2010). The Mexican sampling frame does not overlap with the US sampling frame, so in the combined sample we treated each frame as a separate domain for purposes of design-based variance estimation (Kish, 1999; Korn and Graubard, 1999). Hence, we calibrated the MNCS weights to represent 40.6 million individuals, based on the estimated number of 18 to 65 years old lived in households in towns (> 2,500 inhabitants) in the Mexican Census of the Populations and Households, 2000 (INEGI: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática10).

To estimate and compare gender and migration group specific differences in age of first opportunity for substance use and of duration from first opportunity to first use, we fitted discrete-time proportional hazards regression models on a dataset with person-years as the units of analysis (Chambless and Boyle, 1985; Efron, 1988; Willett and Singer, 1993). The person-years analyses allows us to take account of the temporal ordering of the migration, initial exposure opportunity and initial substance use events (Willett and Singer, 1993), to adjust for time-varying and time-fixed covariates and to use design-based estimation methods to account for survey design effects (Korn and Graubard, 1999).

Our use of discrete time event history analyses (Willett and Singer, 1993) relied on retrospective age-at-onset reports to establish a temporal order between the predictors and the outcomes. Design-based standard errors were estimated using the Taylor linearization method (Binder, 1983) with SUDAAN version 10.01 (Research Triangle Institute, 2009) and were used in Wald tests for statistical significance in contingency table analyses (e.g. Wald chi-square tests for association) as well as for regression coefficients (e.g., adjusted log hazard ratios). Design-weighted survival (Kaplan-Meier) curves were produced in Stata (Stata Corp LP, 2009), using output from SUDAAN.

3. Results

While the Mexicans living in Mexico without migration experience or a migrant relative (Mexican population for short) and those in the CPES that migrated at age 12 or younger had larger proportions of females than males, the opposite is true for those in the CPES that migrated at age 13 or older (Table 1). Those in CPES that migrated at age 12 or younger had the largest proportion of respondents in the youngest groups, while the Mexican population tends to be more evenly distributed across the four age groups.

Table 1.

Population characteristics by migrant group. Mexican sample from the MNCS & CPES (N=3432).

| Total | Mexican national no migrant in family |

Mexico born immigrant migrated at age ≥13 |

Mexico born immigrant migrated at age ≤12 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=3432 |

N=2878 |

N=417 |

N=137 |

|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1347 (47.9) | 1088 (45.7) | 209 (57.0) | 50 (44.9) |

| Female | 2085 (52.1) | 1790 (54.3) | 208 (43.0) | 87 (55.1) |

| Age | ||||

| 18–25 | 814 (26.5) | 709 (28.9) | 58 (15.1) | 47 (36.4) |

| 26–35 | 1041 (30.4) | 810 (27.4) | 181 (40.3) | 50 (33.4) |

| 36–45 | 778 (21.5) | 661 (20.9) | 96 (25.3) | 21 (15.8) |

| 46–89 | 779 (21.6) | 698 (22.8) | 82 (19.3) | 19 (14.4) |

Weighted percentages.

Table 2 shows the lifetime prevalence of first opportunity to use alcohol and drugs, and of use of alcohol and drugs among those that were offered alcohol or drugs, for the total population and by sex. Starting with the total population, in three variables there were large differences in the lifetime prevalences according to migration groups. Those in the CPES that migrated at age 13 or older had a higher proportion that used alcohol when offered, had a higher prevalence of opportunity to use drugs and were more likely to use drugs after having the opportunity when compared to the Mexican population. On the other hand, those in CPES that migrated while young (less than 13 years of age) had a higher prevalence of opportunity to use drugs and were more likely to use drugs after having the opportunity. When separated by sex, there was no difference in exposure opportunity to use alcohol among males, and no differences in likelihood to use after being offered alcohol and drugs among females.

Table 2.

Lifetime prevalence of opportunities to use alcohol and drugs by migration group and lifetime prevalence of alcohol use and drug use among those with exposure. Mexican sample from the MNCS & CPES (N=3432).

| Alcohol |

Drugs |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to opportunity |

>12 drinks per year given opportunity |

Exposure to opportunity |

Ever use given opportunity |

|||||

| N | n(%) | N | n(%) | N | n(%) | N | n(%) | |

| Total | 3390 | 28711 (85.2) | 2845 | 1427 (54.4) | 3304 | 11011 (38.3) | 1099 | 256 (25.7) |

| No migrant in family | 2841 | 2420 (85.7) | 2397 | 1147 (50.9) | 2755 | 811 (32.1) | 810 | 166 (21.0) |

| Mexico born migrated at age ≥13 | 413 | 324 (81.0) | 323 | 209 (68.0) | 412 | 195 (50.9) | 194 | 59 (31.6) |

| Mexico born migrated at age ≤12 | 136 | 127 (93.1) | 125 | 71 (53.3) | 137 | 95 (69.6) | 95 | 31 (37.0) |

| X2(df=2) | 5.84 | 44.86* | 57.15* | 12.40* | ||||

| Male Only | 1338 | 1238 (92.3) | 1230 | 965 (77.4) | 1316 | 759 (59.1) | 757 | 201 (28.9) |

| No migrant in family | 1080 | 996 (91.1) | 990 | 760 (75.3) | 1061 | 566 (52.7) | 565 | 128 (22.8) |

| Mexico born migrated at age ≥13 | 208 | 193 (94.5) | 192 | 167 (85.2) | 205 | 148 (72.2) | 147 | 54 (36.9) |

| Mexico born migrated at age ≤12 | 50 | 49 (97.2) | 48 | 38 (69.3) | 50 | 45 (82.8) | 45 | 19 (47.1) |

| X2(df=2) | 3.96 | 12.33* | 22.49* | 12.94* | ||||

| Female Only | 2052 | 1633 (78.6) | 1615 | 462 (29.3) | 1988 | 342 (18.8) | 342 | 55 (16.2) |

| No migrant in family | 1761 | 1424 (81.1) | 1407 | 387 (27.6) | 1694 | 245 (14.2) | 245 | 38 (14.9) |

| Mexico born migrated at age ≥13 | 205 | 131 (62.9) | 131 | 42 (34.3) | 207 | 47 (23.3) | 47 | 5 (10.7) |

| Mexico born migrated at age ≤12 | 86 | 78 (89.8) | 77 | 33 (38.9) | 87 | 50 (58.9) | 50 | 12 (25.4) |

| X2(df=2) | 9.55* | 4.65 | 28.35* | 4.63 | ||||

Weighted percentages;

significance at p<0.01.

Note missing values.

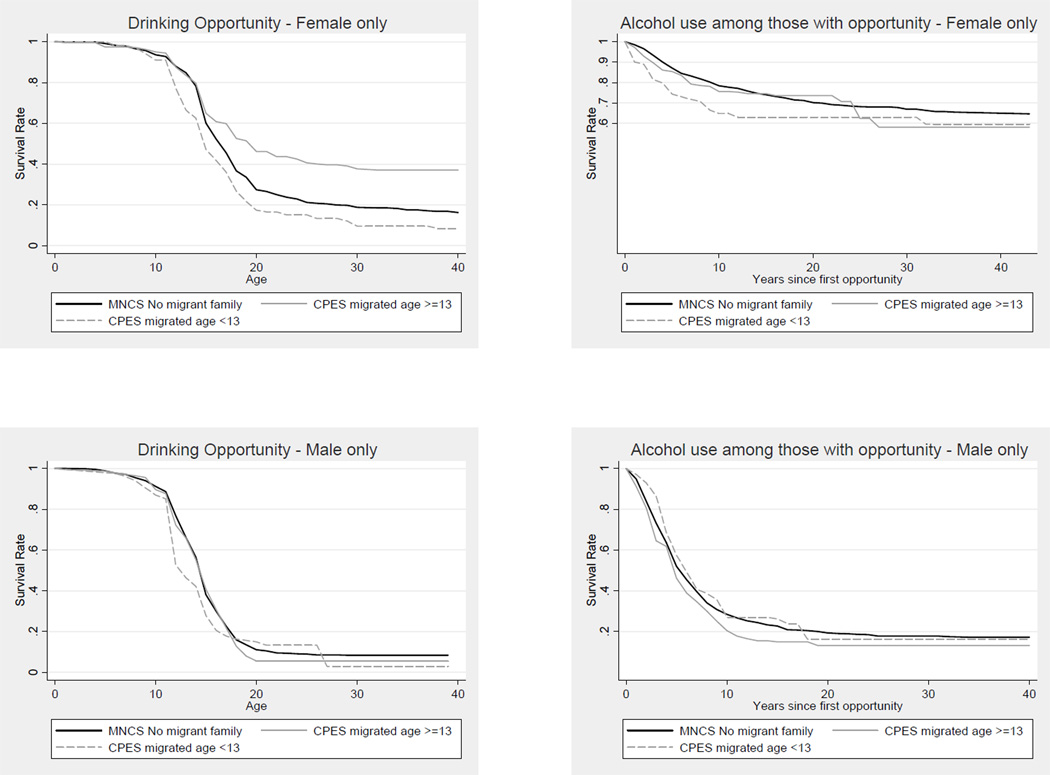

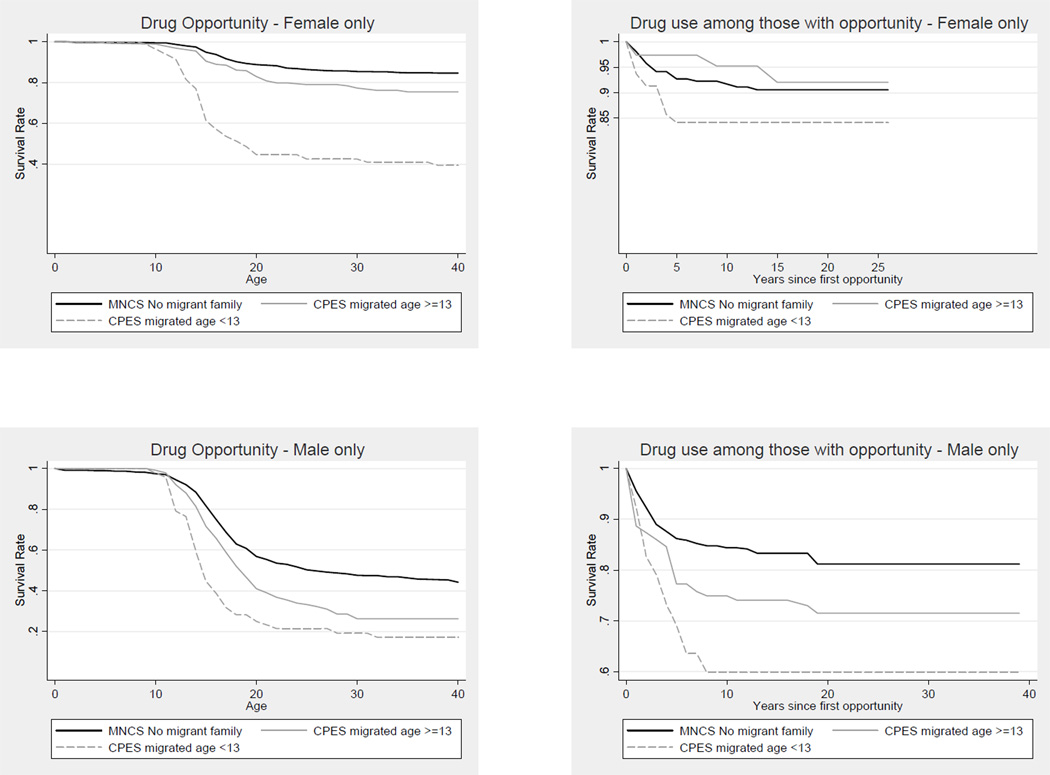

Since a key concept is how long it takes from first opportunity to first use of alcohol-drug use, survival curves are especially informative. In Figure 1 we show figures for alcohol and in Figure 2 we show similar figures for drugs, both disaggregated by sex. For alcohol use first (Figure 1), among females, those in the CPES that migrated at age 13 or older and those from the MNCS without migration experiences are the ones less prone to be offered alcohol. Given the opportunity, again those in the CPES that migrated at 13 or older are the ones less prone to use alcohol. Among males, the curves for alcohol are much more similar, with few differences across groups. For drug use (Figure 2), among females, even when the prevalences are much lower, the MNCS without migration experience is the group less likely to use drugs. Among males, larger differences are apparent now, with those that immigrated while young (less than 13 years) more likely to be offered and to use once offered. In all instances, the use after opportunity tends to occur quickly.

Figure 1.

Survival rates of alcohol opportunity and use given opportunity by sex and migrant group. Mexican sample from the MNCS & CPES (N=3,432)

Figure 2.

Survival rates of drug opportunity and use given opportunity by sex and migrant group. Mexican sample from the MNCS & CPES (N=3,432)

Results from discrete time proportional hazards regression model for age of initial exposure and for time to first use once exposed, for alcohol and drugs, separately for males and females are presented on Table 3. All models used the MNCS without migration experiences as the comparison group for adjusted hazard ratio (HR) calculations. For alcohol use opportunities and alcohol use given the opportunity, no sex interactions were found. For males, immigration did not increase the risk of being offered alcohol. Female immigrants were at lower risk of having opportunities to use alcohol if they immigrated after the age of 13, but at higher risk if they immigrated prior to this age. There was no association between alcohol use after having the opportunity among immigrants, neither for males nor females.

Table 3.

Hazard ratio of exposure to opportunity of alcohol and drug use and use given the opportunity by migration groups and sex. Mexican sample from the MNCS–CPES (N=3432).

| Alcohol |

Drug |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to opportunity |

First drink after opportunity1 |

Exposure to opportunity |

First use after opportunity1 |

|

| HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | |

| Males | ||||

| Mexico born migrated at ≥13 y | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 1.7 (1.2–2.4)* | 2.2 (1.2–4.0)* |

| Mexico born migrated at ≤12 y | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 2.8 (1.6–5.0)* | 2.3 (1.3–4.2)* |

| X2 df=2 | 1.54 | 2.31 | 24.15* | 8.82* |

| Females | ||||

| Mexico born migrated at ≥13 y | 0.5 (0.3–0.8)* | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 3.0 (1.8–5.1)* | 2.6 (0.8–8.3) |

| Mexico born migrated at ≤12 y | 1.4 (1.1–1.8)* | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 7.3 (4.2–12.7)* | 2.1 (0.7–6.6) |

| X2 df=2 | 15.36* | 1.33 | 84.46* | 2.79 |

| Total | ||||

| Interaction sex*migration category X2 df=2 | 1.17 | 2.60 | 6.32* | 0.28 |

Time varying. HR(95%CI)= Hazard Ratio; confidence interval 95%. Survival model person-year data controlled by age, education, and marital status. Reference group: No family migrant (n= 2878).

Significance at p<0.05.

For drug use, a sex interaction was found for being offered drugs with females showing higher HR than males in both instances. The migration experience dramatically increased the rates of opportunity to being offered drugs in all groups. For drug use after being given the opportunity, all migration experiences showed increased HR when compared to the MNCS without migration experiences, but this increase in risk lacked statistical significance for females even though they were of similar magnitude than the ones observed for males. No sex interaction was found.

4. Discussion

The main finding of this study is that the immigration process was associated with opportunity to use and use given the opportunity depending on the substance and sex of the respondent. Our first hypothesis was partially confirmed: compared to the Mexican population, male immigrants in the US had equal risk of ever being offered alcohol (as expected), but females showed mixed results with a decrease in risk (among females that immigrated at older ages, not expected) and an increased risk (among females that immigrated at younger ages, as expected). Thus, for alcohol, differential availability does not play a role for males as it does for females. With regards to drugs, as per our hypothesis, we found that the increased opportunity for drug use was apparent for immigrants of both sexes, with higher HRs found for female immigrants. Thus, for drugs, availability likely plays a role in increased drug use rates for immigrants of both sexes, but is particularly pronounced for females. Our next hypothesis was only partially confirmed: risk of using alcohol given the opportunity was similar for male and female immigrants compared to male and female nationals in Mexico (as expected); it was also similar for using drugs once offered for females immigrants (as expected), but drug use given the opportunity was higher for immigrant males compared to male nationals (not expected).

These results, in general, shed light upon the potential role of availability and social norms upon changes in immigrant substance use. The lack of differences in rates of alcohol use and alcohol use disorders between male immigrants and non-immigrant nationals that we reported previously (Borges et al., 2011) may indeed be due to similarities in the availability (exposure opportunity) of alcohol in both countries, a key factor in the epidemiology of alcohol use (Babor et al., 2003). As the exposure opportunity for alcohol among males was more than 90% in the Mexican population, a limitation is that we may lack variability in this outcome. However, there are more exposure opportunities for females who arrive in the US as children, perhaps signaling greater alcohol control for young females in Mexico than in the U.S. and perhaps reflecting the higher degree of acculturation of those who arrive as children as opposed to older ages which would be consistent with the findings of increased substance use among more acculturated female immigrants (Zemore, 2005). It is interesting that given the opportunity, the likelihood to use alcohol is no different among immigrants (both male and female) compared to the Mexican population suggesting that social norms related to alcohol use are quite similar among these groups, regardless of the alleged larger levels of stress and other changes associated with the migration experience.

For drug use, the current results suggest that the increased drug use and drug use disorders found in Mexican immigrants may be primarily related to greater availability (exposure opportunity) of drugs in the US, compared to Mexico. Even when it is well accepted that larger availability of drugs is related to drug use, this is a factor hardly mentioned in the study of immigration and substance use disorders. This factor seems to be independent of any additional impact that the immigration process may have on increasing levels of stress (Alegria et al., 2006; Warner et al., 2006), acculturation (Vega et al., 1998a) and even norms related to alcohol and drug use in the society (Zemore, 2007). Our finding that female immigrants had larger HRs for opportunity to use drugs when compared to males are in line with a large body of research in the US on drug use contrasts between immigrants and US born of Mexican (Vega et al., 1998b) or Hispanic origin nationals (Canino et al., 2008). Prior research in the US on risk factors for opportunities to use drugs have focused on environmental factors, such as bad neighborhood, or more individual factors, such as peer drug use or lack of parental supervision (Storr et al., 2011). Given the low SES associated with the Mexican migration to the US and the fragmentation of families of migrants with few social ties in the US (Canino et al., 2008), these factors may be very relevant for this population and research in the area is necessary and could be promising. As a context to further interpret our results, it also should be stressed the sex differences in baselines rates of alcohol and drug use in Mexico, with women’s rates far below men’s rates, so that for women, compared to men, a large proportional impact on their baseline rates could be expected in their route to approach the US baseline rates.

Our results regarding the lack of differences (interactions) in the HRs for males and females once drugs have been offered are in line with other research in this area, including recent results from a large group of countries (Benjet et al., 2007a; Van Etten and Anthony, 1999; Wells et al., 2011), but others (Chen et al., 2004) have found differences by sex. Whether someone that has been offered alcohol or drugs chooses to use (or not use) can arguably be more related to societal norms, among a cadre of other risk factors (Warner et al., 2006), including genetically based factors (Agrawal and Lynskey, 2008; Merikangas et al., 2009). Interestingly, while males of both immigrant groups had increased HRs for drug use given the opportunity when compared to the Mexican population, female immigrants also showed increased HRs, but they were non-significant. It is possible that male immigrants enter into an environment with little supervision and more peer pressure (Storr et al., 2011; Van Etten and Anthony, 1999) or that some of the increase availability in income among males immigrants are diverted to drug use (Degenhardt et al., 2008). On the other hand, limited statistical power due to the small number of females with drug use opportunities and the small number of female drug users among those exposed to opportunities is a concern, which limits our ability to reach a more definitive conclusion regarding female immigrant drug use when given the opportunity.

Some further limitations may apply to our findings. We assumed that age at first opportunity to use is an indirect measure of availability but to the extent that other variables, such as memory, peer influences or other variables, differentially impact on one of these two concepts, these two variables may not be exactly parallel. Our questionnaire only differentiates between alcohol and drug use opportunity, but not between classes of drugs such as marijuana or cocaine. All information was obtained by self-report and is limited by the willingness of respondents to report on substances that are often illegal. As mentioned elsewhere (Wagner and Anthony, 2002) this limitation is less applicable to the concept of exposure opportunity since being offered a drug is not illegal in itself. Our household surveys excluded homeless and institutionalized people, populations known to have a high prevalence of substance use. This study was about the migration experience of Mexicans to the US. Whether these results would be applicable to immigrants from other nationalities or ethnic backgrounds is a matter of debate and care should be use when generalizing these results (Alegria et al., 2006). Nevertheless, it is of interest that a differential impact of immigration on alcohol and drug use, similar to the one reported here, was also found among youths from the Island of Puerto Rico and the US mainland (Merikangas et al., 2009).

Assessments were based on respondent recall, which is likely to result in underestimates of prevalence and may introduce bias if recall is differential across migration groups. For instance, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that differential recall contributes to our finding that early age at migration predicts high likelihood of having the opportunity to use substances is partially due to age related recall bias, i.e., that younger people are more likely to recall events in adolescence because they are more recent. Migrants who arrived at early ages were also younger at the time of the interview. We also note that this finding is consistent with research showing large differences in the experience of migrants due to the age at which they arrive in the US (Rumbaut, 2004). Finally, despite using the same diagnostic interview, the two surveys differed in several ways, including the auspices of the survey. We cannot rule out the possibility that these methodological differences contributed to the observed differences in prevalence estimates in the CPES compared with the MNCS. While we decided to study the impact of age at arrival in the US to stress the normative influences of the US culture for those who immigrated while youths, there is the potential that the number of years living in the US also exerts a specific influence on the exposure to substances and the decision to use substances, as showed by others (Vega et al., 1998). Since these two approaches are collinear, we cannot study the two at the same time.

5. Conclusions

These limitations notwithstanding, we showed that an increase in drug availability, indirectly measured by opportunity to use drugs, is a key factor in the greater drug use of Mexican immigrants. While affecting both sexes, females suffered more the effects of greater availability. For alcohol, there do not appear to be differences among male immigrants and male Mexican nationals with regards to availability and social norms as indirectly assessed via exposure opportunities and use given the opportunity. For females there are differences only for exposure opportunities and these differences are dependent upon age of migration, females arriving in the US during childhood being exposed to a greater availability of alcohol. Public health messages and educational efforts should take into consideration this distinction among drug and alcohol use in male and female immigrants.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

Support for survey data collection came from funding provided by NIMH Grant R01 MH082023 (J. Breslau, P.I.). Funding organization (NIMH) had no interference on the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

G. Borges collected data in Mexico, analyzed the data, and wrote the initial draft and the final version of the article.

C. Rafful wrote drafts and discussed earlier versions and reviewed the final version of the article.

Benjet participated in planning and data analyses, and reviewed the final version of the article.

D. J. Tancredi consultant for statistical analyses, discussed earlier versions, and reviewed the final version of the article.

N. Saito performed program writing and statistical analyses, discussed earlier versions, and reviewed the final version of the article.

S. Aguilar-Gaxiola discussed drafts and reviewed the final version of the article.

M.E. Medina-Mora collected data in Mexico and reviewed the final version of the article.

J. Breslau participated in planning and data analyses, and reviewed the final version of the article.

All authors helped to conceptualize the study.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Are there genetic influences on addiction: evidence from family, adoption and twin studies. Addiction. 2008;103:1069–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Canino G, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Nativity and DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Puerto Ricans, Cuban Americans, and non-Latino Whites in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2006;67:56–65. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC. Epidemiology of drug dependence. In: Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff C, editors. Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress. Brentwood, TN: American College of Neuropsychophamacology; 2002. pp. 1557–1573. [Google Scholar]

- Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Geisbrecht N, Graham K, Grube J, Gruenewald P, Hill L, Holder H, Homel R, Österberg E, Rehm J, Room R, Rossow I. Research and Public Policy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity. [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Fleiz C, Blanco J, Zambrano J, Rojas E, Ramirez M. Prevalence and socio demographic correlates of drug use among adolescents: results from the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey. Addiction. 2007a;102:1261–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Blanco J, Zambrano J, Orozco R, Fleiz C, Rojas E. Drug use opportunities and the transition to drug use among adolescents from the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007b;90:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder DA. On the variances of asymptotically normal estimators from complex surveys. Int. Stat. Rev. 1983;51:279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Breslau J, Orozco R, Tancredi DJ, Anderson H, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Mora ME. A cross-national study on Mexico-US migration, substance use and substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Lown A, Ye Y, Robertson MJ, Cherpitel C, Greenfield T. Alcohol use disorders in national samples of Mexican-Americans. The Mexican National Addiction Survey and the U.S. National Alcohol Survey. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2006;28:425–449. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Borges G, Kendler KS, Su M, Kessler RC. Risk for psychiatric disorder among immigrants and their US-Born descendants: evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007;195:189. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243779.35541.c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnam MA, Hough RL, Karno M, Escobar JI, Telles CA. Acculturation and lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans in Los Angeles. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1987;28:89–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Medina-Mora ME. Acculturation and drinking among people of Mexican descent in Mexico and the United States. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1988;49:462–471. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Vega WA, Sribney WM, Warner LA, Alegria M. Social relationships, social assimilation, and substance-use disorders among adult Latinos in the US. J. Drug Issues. 2008;38:69–101. doi: 10.1177/002204260803800104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless LE, Boyle KE. Maximum-likelihood methods for complex sample data- logistic-regression and discrete proportional hazards models. Communication Stats.Theory Methods. 1985;14:1377–1392. [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Dormitzer CM, Bejarano J, Anthony JC. Religiosity and the earliest stages of adolescent drug involvement in seven countries of Latin America. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004;159:1180–1188. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Anthony JC, Angermeyer M, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, Huang Y, Karam A, Kostyuchenko S, Lepine JP, Mora ME, Neumark Y, Ormel JH, Pinto-Meza A, Posada-Villa J, Stein DJ, Takeshima T, Wells JE. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Logistic regression, survival analysis, and the Kaplan-Meier curve. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988;83:414–425. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Anderson K. Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites in the United States results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004;61:1226–1233. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.12.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawks D, Scott K, McBride M. Prevention of Psychoactive Substance Use: a Selected Review of What Works in the Area of Prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa S, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2004;13:221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa S, Berglund P. Integrated weights and sampling error codes for design based analysis. http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/cpes/using.xml?section=Weighting. National Institutes of Mental Health Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Survey Program Data Set. User GuIde (29.07.2010) 2007

- INEGI: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, G.e.I. Censo general de poblacion y vivienda 2000: Población en hogares y sus viviendas. 2010 http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/olap/Proyectos/bd/censos/cpv2000/Pobladores.asp?s=est&c=10260&proy=cpv00_phv.INEGI (11.11.11).

- Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish L. Cumulating/combining population surveys. Survey Method. 1999;25:129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of Health Surveys. New York: Wiley Interscience; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lange JE, Voas RB, Johnson MB. South of the border: a legal haven for underage drinking. Addiction. 2002;97:1195–1203. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Munoz CL, Benjet C, Jaimes JB, Bautista CF, Velazquez JV, Guiot ER, Ruiz JZ, Rodas LC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Prevalence of mental disorders and use of services: results from the Mexican National Survey of Psychiatric Epidemiology. Salud Ment. 2003;26:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K, Conway KP, Swendsen J, Febo V, Dierker L, Brunetto W, Stolar M, Canino G. Substance use and behaviour disorders in Puerto Rican youth: a migrant family study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2009;63:310–316. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.078048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys. 2010 www.icpsr.umich.edu/CPES/.CPES (16.3.10).

- Ortega AN, Rosenheck R, Alegria M, Desai RA. Acculturation and the lifetime risk of psychiatric and substance use disorders among Hispanics. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2000;188:728–735. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN version 10.0.1. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. Ages, life stages, and generational cohorts: decomposing the immigrant first and second generations in the United States. Int. Migr. Rev. 2004;38:1160–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corp LP. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell T, Gruenewald P. Controls on the physical availability of alcohol. In: Heather N, Peters TJ, Stockwell T, editors. International Handbook of Alcohol Dependence and Problems. New York: John Wiley; 2001. pp. 699–719. [Google Scholar]

- Storr CL, Wagner FA, Chen CY, Anthony JC. Childhood predictors of first chance of use and use of cannabis by young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNODC. World Drug Report 2011. New York: United Nations Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten ML, Anthony JC. Comparative epidemiology of initial drug opportunities and transitions to first use: marijuana, cocaine, hallucinogens and heroin. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten ML, Anthony JC. Male-female differences in transitions from first drug opportunity to first use: searching for subgroup variation by age, race, region, and urban status. J. Women Health. 2001;10:797–804. doi: 10.1089/15246090152636550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Alderete E, Kolody B, Aguillar-Gaxiola S. Illicit drug use among Mexicans and Mexican Americans in California: the effects of gender and acculturation. Addiction. 1998a;93:1839–1850. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931218399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alderete E, Catalano R, Caraveo-Anduaga J. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1998b;55:771–778. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Into the world of illegal drug use: exposure opportunity and other mechanisms linking the use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and cocaine. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002;155:918–925. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.10.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner LA, Valdez A, Vega WA, de la Rosa M, Turner RJ, Canino G. Hispanic drug abuse in an evolving cultural context: an agenda for research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JE, Haro JM, Karam E, Lee S, Lepine LP, Medina-Mora ME, Nakane H, Posada J, Anthony JC, Cheng H, Degenhardt L, Angermeyer M, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Glantz M, Gureje O. Cross-national comparisons of sex differences in opportunities to use alcohol or drugs, and the transitions to use. Subst. Use Misuse. 2011;46:1169–1178. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.553659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, Singer JD. Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. J. Consult. Clin. Psych. 1993;61:952–964. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Comparative quantification of health risks. Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004. Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE. Re-examining whether and why acculturation relates to drinking outcomes in a rigorous, National Survey of Latinos. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29:2144–2153. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000191775.01148.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE. Acculturation and alcohol among Latino adults in the United States: a comprehensive review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:1968–1990. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]