Abstract

The promiscuity of the enzyme norcoclaurine synthase is described. This biocatalyst yielded a diverse array of substituted tetrahydroisoquinolines by cyclizing dopamine with various acetaldehydes in a Pictet-Spengler reaction. This enzymatic reaction may provide a biocatalytic route to a range of tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids.

Keywords: Biocatalysis, Pictet-Spengler reaction, Norcoclaurine synthase, Tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids

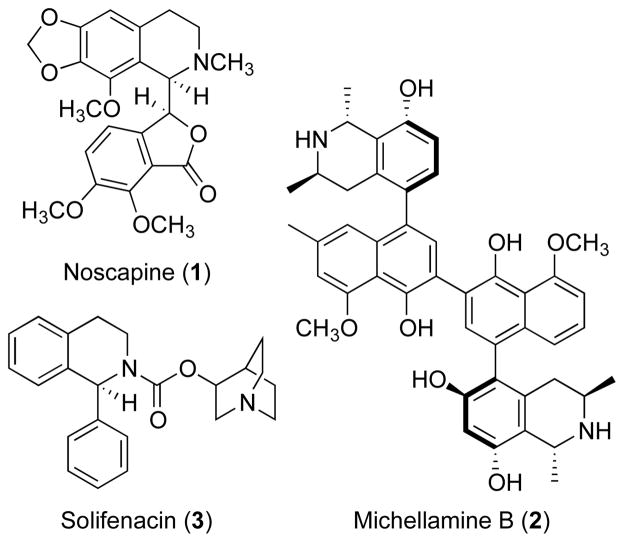

The tetrahydroisoquinoline moiety is found in many natural products and synthetic pharmaceuticals. In particular, this chiral N-heterocyclic scaffold is an integral part of all tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloid natural products. The benzylisoquinoline biosynthetic pathways in plants lead to a large group of alkaloids including the well-known analgesics morphine and codeine, which are isolated from the opium poppy. Additional examples of industrially important tetrahydroisoquinolines include noscapine (1, Figure 1), which has been used as an antitussive since the 19th century, and the anticancer properties of this compound were recently reported.1 The (S)-configured antimuscarinic drug Michellamine B (2),2 isolated from Ancistrocladus plants, is one of many tetrahydroisoquinolines with anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) activity.3 The synthetic compound Solifenacin (3) has a urinary antispasmodic effect.4

Figure 1.

Examples of naturally occurring and synthetic pharmaceutically active tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids.

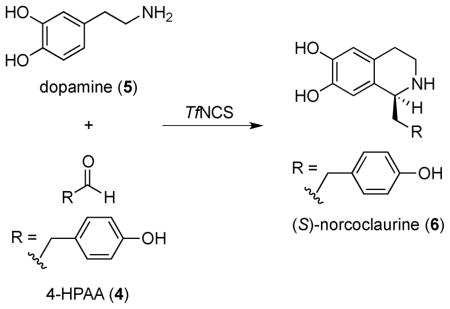

Norcoclaurine synthase (NCS) – one of three known Pictet-Spenglerases5 – catalyzes the C-C bond forming reaction between 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (4-HPAA, 4) and dopamine (5) to afford (S)-norcoclaurine (6) (Table 1), a compound with antiallergic6 and β-adrenergic7 properties, and the biosynthetic precursor to all known naturally occurring tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids. Uncatalyzed Pictet-Spengler reactions with phenylethylamines and aldehydes yield racemic mixtures of tetrahydroisoquinolines.8 Several catalysts have been developed for Pictet-Spengler reactions utilizing substituted tryptamines to yield tetrahydro-β-carbolines.9

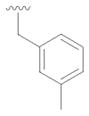

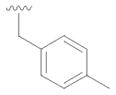

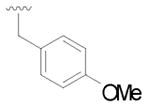

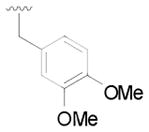

Table 1.

Percent conversion of aldehydes 4,7–25 with TfNCS after 3 hours reaction time. Reaction conditions were as described in the text [dopamine (5) (1 mM), aldehyde 4,7–25 (1 mM), TfNCS (300 μM), TRIS buffer (100 mM, pH 7)]. All enzymatic reactions were performed alongside a control using boiled enzyme to ensure that no reaction occurs in the absence of enzyme.

| ||

|---|---|---|

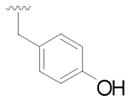

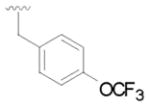

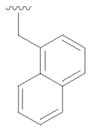

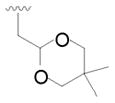

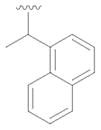

| R = | Product | % conv. after 3 h |

4 |

6 | 60 |

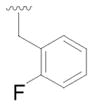

7 |

26 | 65 |

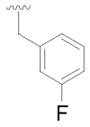

8 |

27 | 66 |

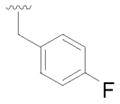

9 |

28 | 71 |

10 |

29 | 66 |

11 |

30 | 58 |

12 |

31 | 57 |

13 |

32 | 69 |

14 |

33 | 69 |

15 |

34 | 65 |

16 |

35 | 51 |

17 |

36 | 68 |

18 |

37 | 61 |

19 |

38 | 71 |

20 |

39 | 42 |

21 |

40 | 52 |

22 |

not detected | --- |

|

23 |

not detected | --- |

|

24 |

not detected | --- |

25 |

not detected | --- |

For production of tetrahydroisoquinolines, the use of asymmetric catalysts for the enantioselective hydrogenation of dihydroisoquinoline derivatives10 can be numbered among the few stereoselective chemical methods reported to produce this class of compounds.

The Pictet-Spenglerase enzymes could, in principle, be used to produce enzymatically tetrahydroisoquinolines in an enantioselective fashion. The stereoselectivity of the NCS catalyzed reaction to yield (S)-configured products has already been shown in various examples in the literature.5c,5d,11,12 However, a key limitation of biocatalytic approaches is the strict substrate specificity of many enzymes. An enzyme must have broad substrate specificity to be practical for wide synthetic application. Here we describe the substrate scope and limitations of the Pictet-Spenglerase NCS, a study that provides a foundation for developing a general biocatalytic strategy for the synthesis of tetrahydroisoquinolines.

Affinity-tagged NCS from Thalictrum flavum (TfNCS) was overexpressed in Eschericha coli and purified using nickel resin in good yields as previously reported.12 This readily produced heterologous enzyme was used to probe systematically the enzymatic requirements for the aldehyde substrate using, in addition to the natural substrate 4-HPAA (4),13 19 aldehyde analogs (7–24). These aldehydes were synthesized either by oxidation of the corresponding alcohols with Dess-Martin periodinane (7–15, 17, 19, 20) or by reduction of the corresponding Weinreb amide with LAH (18), or were commercially available (16, 21–24).14 For the enzymatic assay, we chose to use one of the reported conditions under which NCS had been assayed in previous studies. Specifically we used TRIS–buffered aqueous media at neutral pH with substrate concentrations at 1 mM. While substantial background reaction can often be observed for the Pictet-Spengler reaction, under these conditions no tetrahydroisoquinoline product was detected after 3 hours reaction time with boiled enzyme by HPLC using UV detection at 228 nm. We further controlled for the non-enzymatic background reaction by including a control using boiled (inactive) enzyme with each reaction; in each case, no tetrahydroisoquinoline product was detected by HPLC. Therefore, we could be certain that all tetrahydroisoquinoline products observed were generated enzymatically. Briefly, TfNCS (300 μM) was added to a solution of TRIS buffer (100 mM, pH 7.0) containing dopamine (1 mM) and aldehyde (1 mM). The enzymatic reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature for 1 hour, after which it was quenched with MeOH, and then analyzed by electrospray LC-MS. Authentic standards of each norcoclaurine analog 26–40 were synthesized on a milligram scale, fully characterized by NMR and HRMS analysis and run along with the enzymatic assay (Supporting Information).

TfNCS proved to have exceptionally broad aldehyde substrate specificity, turning over aldehydes 4,7–21 (Table 1). The structures of substrates 4,7–21 vary widely, and include phenylacetaldehydes substituted with various electron-withdrawing or donating groups, heteroaromatic moieties, aromatic bicyclics, aliphatic (hetero)cycles and aliphatic open-chained compounds. Only the products of the smallest, acetaldehyde (23) and propionaldehyde (24) and the α-substituted aldehydes, benzaldehyde (22) and 25 could not be detected.

Reaction rates of aldehydes 4,7–21 were evaluated by measuring the amount of dopamine consumed over time by HPLC using 0.5, 1, 2 and 3 hour time points (Supporting Information). These assays show that 4,7–21 are turned over at a comparable rate with an average consumption of 65% dopamine (5) after 3 hours. A slight disfavor (42–52%) for the aliphatic compounds 20 and 21 as well as the unsubstituted phenylacetaldehyde 16 could be observed (Table 1). In summary, we found that TfNCS was able to catalyze the reaction between dopamine and acetaldehydes containing more than 3 carbon atoms and that are unsubstituted at the α-position. Aromatic acetaldehydes appear to be slightly superior substrates compared to bulky aliphatic compounds. Overall, however, all the aldehydes appeared to be converted in qualitatively similar rates. The aldehyde substrate flexibility provides a general method for the enzymatic preparation of 1-(ortho-, meta- and para-substituted benzyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolines.

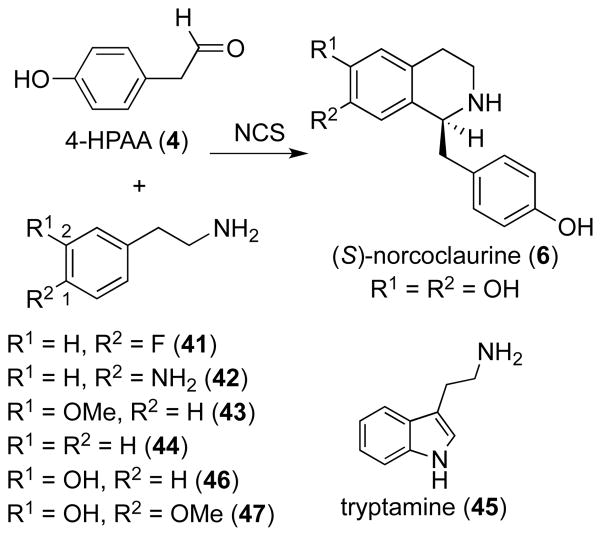

In contrast to the relaxed substrate specificity observed for the aldehyde substrate, NCS showed a strict requirement for the amine substrate, dopamine (5). We failed to detect any product for enzymatic reactions utilizing the native aldehyde substrate 4-HPAA (4) and the commercially available phenethylamines 41–44 (Scheme 1). Tryptamine (45), the natural substrate of strictosidine synthase, the Pictet-Spenglerase that catalyzes formation of tetrahydro-β-carbolines,15 was also not turned over. Overall, this substrate specificity is consistent with earlier mechanistic studies of NCS. Luk et al.12 proposed the formation of a quinoid at the C-2 position of the aromatic ring, which requires that the phenethylamine substrate contains a hydroxy group at the C-2 position. Therefore, while 46 and 47 (Scheme 1) could be turned over by NCS,12 substrates 41–45 could not.

Scheme 1.

Phenethylamines 41–47 assayed with TfNCS and with co-substrate 4-HPAA (4).

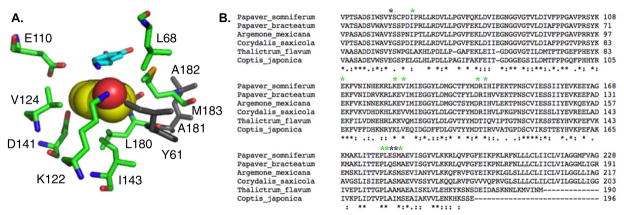

The crystal structure of TfNCS, which was recently published in 2009,16 revealed that this enzyme harbors a relatively shallow active site (Figure 2), which is consistent with the range of aldehydes that can be turned over by NCS. With the exception of the residues that directly interact with the aldehyde functional group, the binding pocket for substrate 4 appears to consist largely of hydrophobic interactions that could presumably accommodate substrate analogs 7–21. The aromatic 4-HPAA (4) and dopamine (5) appear to stack together in the enzyme active site (Figure 2A), but given the turnover of aliphatic aldehyde substrates, this stacking interaction must not be essential. We note that Ile143 appears to be close to the alpha carbon of 4, and this residue may be responsible for preventing turnover of α-substituted aldehydes. We hypothesize that the strict amine substrate specificity is not governed by the confines of the enzyme active site, but instead by the reactivity requirements of the substrate.

Figure 2.

A. The norcoclaurine active site (2VQ5) surrounding the aldehyde substrate 4. The co-substrate 5 is in blue. Lys122 and Glu110 are important for catalysis.16 All conserved residues that surround 5 are in green; residues that vary amongst annotated NCS enzymes are in grey. B. Alignment of annotated NCS enzymes. Residues labeled with * are shown in panel A and are conserved; * are in panel A but are not conserved amongst the NCS homologs.

In summary, we have showed that the enzyme norcoclaurine synthase can be used as a biocatalyst to yield a variety of substituted tetrahydroisoquinolines. We further note that the potential of the enzyme in a multi-gram scale enantioselective preparation of (S)-norcoclaurine itself was recently described.11 The easy overexpression in E. coli and purification on large scale, as well as the stability of the protein, suggests potential applications in synthetic chemistry.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Karlsruhe House of Young Scientists (KHYS) for financial support. We thank Anne Rüger, KIT, for the synthesis of aldehyde 25.

Footnotes

Experimental procedures and spectral characterization.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Jackson T, Chougule MB, Ichite N, Patlolla RR, Sing M. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;63:117–126. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0720-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd MR, Hallock YF, Cardellina JH, II, Manfredi KP, Blunt JW, McMahon JB, Buckheit RW, Jr, Bringmann G, Schäffer M, Cragg GM, Thomas DW, Jato JG. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1740–1745. doi: 10.1021/jm00038a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng P, Huang N, Jiang ZY, Zhang Q, Zheng YT, Chen JJ, Zhang XM, Ma YB. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:2475–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrams P, Andersson KE. BJU Int. 2007;100:987–1006. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Kutchan TM. Phytochemistry. 1993;32:493–506. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)95128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) De-Eknamkul W, Suttipantaa N, Kutchan TM. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:177–181. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Samanani N, Liscombe DK, Facchini PJ. Plant J. 2004;40:302–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Minami H, Dubouzet E, Iwasa K, Sato F. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6274–6282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pyo MK, Lee DH, Kim DH, Lee JH, Moon JC, Chang KC, Yun-Choi HS. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:4110–4114. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsukiyama M, Ueki T, Yasuda Y, Kikuchi H, Akaishi T, Okumura H, Abe K. Planta Medica. 2009;75:1393–1399. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pesnot T, Gershater MC, Ward JM, Hailes HC. Chem Commun. 2011;47:3242–3244. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05282e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Kampen D, Reisinger CM, List B. Top Curr Chem. 2010;291:395–456. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-02815-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yamada H, Kawate T, Matsumizu M, Nishida A, Yamaguchi K, Nakagawa M. J Org Chem. 1998;63:6348–6354. doi: 10.1021/jo980810h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Taylor MS, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10558–10559. doi: 10.1021/ja046259p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zhuang W, Hazell RG, Jorgensen KA. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:2566–2571. doi: 10.1039/b505220c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Seayad J, Seayad AM, List B. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1086–1087. doi: 10.1021/ja057444l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Raheem IT, Thiara PS, Jacobsen EN. Org Lett. 2008;10:1577–1580. doi: 10.1021/ol800256j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Sewgobind NV, Wanner MJ, Ingemann S, de Gelder R, van Maarseveen JH, Hiemstra H. J Org Chem. 2008;3:6405–6408. doi: 10.1021/jo8010478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pyo MK, Lee DH, Kim DH, Lee JH, Moon JC, Chang KC, Yun-Choi HS. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:4110–4114. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonamore A, Rovardi I, Gasparrini F, Baiocco P, Barba M, Molinaro C, Botta B, Boffi A, Macone A. Green Chem. 2010;12:1623–1627. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luk LYP, Bunn S, Liscombe DK, Facchini PJ, Tanner ME. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10153–10161. doi: 10.1021/bi700752n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Synthesized by Parikh-Doehring oxidation as described previously: Hirose T, Sunazuka T, Tian Z-H, Handa M, Uchida R, Shiomi K, Harigaya Y, Omura S. Heterocycles. 2000;53:777–784.

- 14.Aldehyde 25 was synthesized as described in: Hoffmann S, Nicoletti M, List B. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13074–13075. doi: 10.1021/ja065404r.

- 15.Bernhardt P, Usera AR, O’Connor SE. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:4400–4402. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.06.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ilari A, Franceschini S, Bonamore A, Arenghi F, Botta B, Macone A, Pasquo A, Belluci L, Boffi A. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:897–904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.