Abstract

Endoglycoceramidase (EGCase) is a glycosidase capable of hydrolyzing the β -glycosidic linkage between the oligosaccharides and ceramides of glycosphingolipids (GSLs). Three molecular species of EGCase differing in specificity were found in the culture fluid of Rhodococcus equi (formerly Rhodococcus sp. M-750) and designated EGCase I, II, and III. This study describes the molecular cloning of EGCase I and characterization of the recombinant enzyme, which was highly expressed in a rhodococcal expression system using Rhodococcus erythropolis. Kinetic analysis revealed the turnover number (kcat) (kcat) of the recombinant EGCase I to be 22- and 1,200-fold higher than that of EGCase II toward GM1a and Gb3Cer, respectively, although the Km of both enzymes was almost the same for these substrates. Comparison of the three-dimensional structure of EGCase I (model) and EGCase II (crystal) indicated that a flexible loop hangs over the catalytic cleft of EGCase II but not EGCase I. Deletion of the loop from EGCase II increased the kcat of the mutant enzyme, suggesting that the loop is a critical factor affecting the turnover of substrates and products in the catalytic region. Recombinant EGCase I exhibited broad specificity and good reaction efficiency compared with EGCase II, making EGCase I well-suited to a comprehensive analysis of GSLs.

Keywords: endoglycoceramidase, glycosphingolipid, flexible loop, globo-series glycosphingolipids, oligosaccharide, Rhodococcus

Glycosphingolipids (GSLs), amphipathic compounds consisting of oligosaccharides and ceramide (Cer) moieties, are ubiquitous in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. More than 500 species of GSLs differing in oligosaccharides and Cer moieties have been characterized, some of which represent potential biomarkers for diseases and cell development. For instance, Forssman antigen is specifically detected in some gastric, colonic, and lung cancers (1), and stage-specific embryonic antigen (SSEA)-3 and SSEA-4, highly expressed at a stage of embryonic development, are utilized as a marker of embryonic stem cells (2) and induced pluripotent stem cells (3).

The classification of GSLs, into ganglio-series, globo-series and lacto-series GSLs, is entirely based on the structure of the saccharide moiety. However, the Cer moiety, composed of a sphingoid base and fatty acyl chain linked by an N-acyl linkage, shows heterogeneity in carbon chain length, and saturation and hydroxylation status, etc. The complexity of the Cer moiety prevents the comprehensive analysis of cellular GSLs by MS and/or LC-MS. Removal of the Cer moiety makes the analysis of GSLs much simpler and easier. For this purpose, chemical methods such as ozonolysis (4) and osmium-catalyzed periodate oxidation (5) have been developed. These chemical methods, however, require complicated and time-consuming procedures with relatively low yield (6). Alternatively, enzymes capable of detaching intact oligosaccharides from various GSLs were found in actinomycetes (7) and the leech (8), designating endoglycoceramidase (EGCase) and Cer glycanase, respectively. (EC 3.2.1. 123). Three molecular species of EGCase (EGCase I, II, and III) were found in the culture fluid of Rhodococcus equi (formerly named Rhodococcus sp. M-750) (9), a pathogen causing bronchopneumonia in horses (10). Two (EGCase II and III) of three EGCase species have been cloned from R. equi M-750 and characterized (11, 12). EGCase II mainly hydrolyzed ganglio- and lacto-series GSLs, whereas globo-series GSLs are hydrolyzed very slowly and 6-gala-series GSLs, possessing a common structure R-Gal β1-6Galβ-Cer, are completely resistant to hydrolysis by EGCase II (9). In contrast, EGCase III (renamed endogalactosylceramidase, EGALC) hydrolyzed 6-gala-series GSLs but not ganglio-, lacto- and globo-series GSLs (12). Enzymes possessing similar specificity to EGCase II have been found not only in actinomycetes (7, 9) and the leech (8, 13), but also in earthworm (14), jellyfish (15) and hydra (16). The molecular cloning of animal EGCase has been performed in the last two animals. Molecular cloning (11) and X-ray crystal analysis (17) of EGCase II revealed that the enzyme, belonging to glycoside hydrolase (GH) family 5, was composed of an N-terminal (β / α)8 domain and a C-terminal β -sandwich domain.

The oligosaccharides released by EGCases could be labeled by aromatic amine-based fluorescent reagents (18–22) and analyzed sensitively by HPLC and MS or LC-MS (23). Recently, Fujitani et al. (24) reported the cellular glycomics of GSLs based on the preparation of oligosaccharides with rhodococcal EGCase followed by glycoblotting and MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS. Jellyfish EGCase and rhodococcal EGALC were also utilized for the synthesis of fluorescent GSLs and neoglycoconjugates by utilizing their transglycosylation reactivity (25, 26).

A recombinant rhodococcal EGCase II is now commercially available. However, the enzyme is not suitable for a comprehensive analysis of GSLs because of its narrow specificity, e.g., weak activity for globo-series GSLs and fucosyl-GM1a (27). It is worth noting that biologically important antigens such as Forssman, SSEA-3, and SSEA-4 are globo-series GSLs (1, 2).

This study describes the first molecular cloning and characterization of EGCase I, expressed in R. erythropolis by a rhodococcal expression system. The recombinant EGCase I was found to exhibit broad specificity and good reaction efficiency compared with EGCase II and EGALC: i.e., the recombinant EGCase I efficiently hydrolyzed not only ganglio-series GSLs but also globo-series GSLs and fucosyl-GM1a. Furthermore, we report a distinct structural difference, which may explain in part the difference in specificity and reaction efficiency between EGCase I and EGCase II, based on the three-dimensional structure of both EGCases.

The broad specificity and good reaction efficiency make EGCase I the best enzyme reported so far for detaching the oligosaccharide moiety from various GSLs, and the enzyme could be applicable for the comprehensive analysis of GSLs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

LA taq was purchased from Takara Bio Inc., Japan. The restriction enzyme and Ligation-Convenience Kit were obtained from Nippon Gene, Japan. Precoated Silica gel 60 TLC plates were purchased from Merck, Germany. GD1a, GM1a, Gb4Cer, GlcCer, GM3, and GM4 were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Japan. Gb3Cer was obtained from Nacalai Tesque, Japan. C12-NBD-Gb3Cer was purchased from Matreya, USA. LacCer was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany. Forssman antigen was kindly donated by Dr. M. Suzuki, RIKEN, Japan. NeogalatriaosylCer (trigalactosylCer, TGC) was prepared from the turban shell of Turbo cornutus by a method described previously (28). Fucosyl-GM1a was prepared from porcine brain as described (27). C12-NBD-GM1a was also prepared as reported previously (29). Triton X-100 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The electro-competent cells of R. erythropolis JCM3201 were prepared as described (30).

Cloning of a gene encoding EGCase I2

A putative gene encoding EGCase I was found in the R. equi genomic database (31) by TBLASTN using the amino acid sequence of EGCase II or EGALC as a query. Genomic DNA of R. equi M-750 was prepared as described previously (11) and used as a template for amplifying egcase I. PCR was carried out using the following two primers for amplification of egcase I: LCH169-E1S (5 ′ -GGCATATGCGCAAAACCGTTGTCGCATTCG-3 ′ ) and LCH169-E1A (5 ′ -CCAAGCTTGGAGCTTCCGGAGCTGC-3 ′ ). These two primers contained a NdeI site and an HindIII site, respectively. The conditions for amplification were 30 cycles (each consisting of denaturation at 98°C for 30 s, annealing at 58°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 120 s) using TaKaRa LA Taq DNA polymerase. The amplified product was digested with NdeI and HindIII, and inserted into the corresponding sites of pTip LCH 2.2 (30) to generate a C-terminal His6-tagged protein. The recombinant plasmid was designated as pTip-EGCI.

Sequence analysis and homology modeling of EGCase I

The alignment of amino acid sequences of EGCase I and II and EGALC were conducted with CLUSTAL X (32) and shaded in ESPript 2.2 (33). A three-dimensional model of EGCase I was built by MODELER 8v2 (34) based on the crystal structure of the catalytic domain of EGCase II (17) (PDB ID: 2osw, 2osx and 2osy). The model was validated by the PROCHECK program (35). The secondary structure of jellyfish EGCase (15) was predicted by PSIPRED v3.0 (36).

Expression and purification of the recombinant EGCase I

R. erythropolis JCM3201 cells were mixed with 100 ng of pTip-EGCI and transferred to a 0.2 cm gap cuvette (Bio-Rad) and electroporated (2.5 kV, 25 μ F, 400 Ω ) with Gene pulser II (Bio-Rad). The electroporated cells were transferred to Luria-Bertani agar plates supplemented with 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol and incubated at 30°C for 4 days. Transformed R. erythropolis JCM3201 cells were grown at 30°C for 48 h in 20 ml of Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol with shaking. The culture was then transferred into 200 ml of fresh medium and incubated until the A600 reached approximately 0.6. Thiostrepton was added at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml to cause transcription. After 24 h at 30°C, the cells were harvested by centrifugation (7,500 g for 10 min) and the supernatant was saturated with 70% ammonium sulfate and left overnight at 4°C. The precipitate was collected with centrifugation at 7,500 g for 60 min at 4°C, and dissolved in 20 ml of 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The sample solution was applied to a column of Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 500 mM NaCl, and the column was washed with 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 500 mM NaCl and 50 mM imidazole. The recombinant EGCase I was eluted from the column with 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 500 mM NaCl and 200 mM imidazole. The purified enzyme was dialyzed against 20 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5.

Protein assay and SDS-PAGE

Protein content was determined by the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce) with BSA as a standard. SDS-PAGE was carried out according to the method of Laemmli (37). The proteins were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB).

EGCase assay and definition of enzyme units

The activity of EGCase was measured using GM1a as a substrate. Two nmol of GM1a was incubated at 37°C with an appropriate amount of enzyme in 20 μ l of reaction buffer [50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5 containing 0.1% (w/v) Triton X-100]. The reaction was terminated by heating in a boiling water bath for 5 min. After drying using a Speed Vac concentrator, the sample was dissolved in 10 μ l of methanol and applied to a TLC plate, which was developed with chloroform-methanol-0.02% CaCl2 (5:4:1, v/v/v). The remaining GM1a and oligosaccharide generated by hydrolysis were visualized by spraying the TLC plate with orcinol-H2SO4 reagent and scanned with a Shimadzu CS-9300 chromatoscanner with the reflection mode set at 540 nm. The extent of hydrolysis was calculated as follows: hydrolysis (%) = (peak area for oligosaccharide) × 100 / (peak area for oligosaccharide + peak area for remaining substrate). One unit of EGCase was defined as the amount of enzyme that hydrolyzes 1 μ mol of GM1a per min under the conditions described above.

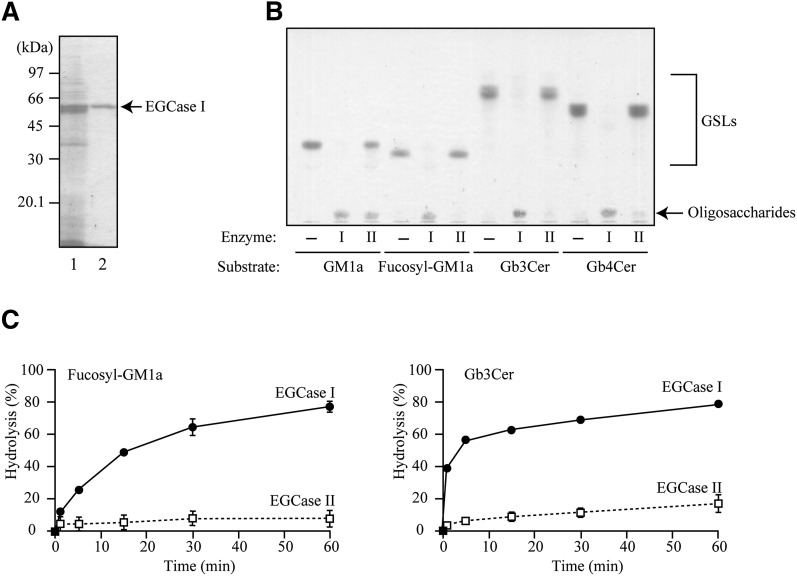

When the substrate specificity of EGCase I was compared with that of EGCase II, the same amount of enzyme protein (Fig. 2B) or the same amount of enzyme unit (Fig. 2C) was used for the assay. In the latter experiment (Fig. 2C), both enzyme activities were standardized using GM1a.

Fig. 2.

Substrate specificity of the purified recombinant EGCase I. A: SDS-PAGE showing the purification of the recombinant EGCase I. The purified protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and visualized with CBB. Lane 1, unbound fraction; lane 2, eluted fraction from a Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow column. B: TLC showing the oligosaccharides released from several GSLs by EGCase I and II. Each GSL (2 nmol) was incubated with 100 ng (for GM1a and Fucosyl-GM1a), 200 ng (for Gb3Cer), or 1 μ g (for Gb4Cer) of the recombinant EGCase I (I) or EGCase II (II), or without enzyme (−) at 37°C for 60 min (GM1a, Fucosyl-GM1a, and Gb3Cer) or for 16 h (Gb4Cer). Samples were loaded onto a TLC plate that was developed with chloroform-methanol-0.02% CaCl2 (5:4:1, v/v/v). GSLs and oligosaccharides were visualized with orcinol-H2SO4 reagent. C: The time course for hydrolysis of Fucosy-GM1a and Gb3Cer by EGCase I (closed circle) and EGCase II (open square). Each GSL (2 nmol) was incubated with 0.4 mU (Fucosy-GM1a) or 2.5 mU (Gb3Cer) of the recombinant EGCase I or EGCase II. The extent of hydrolysis was calculated by the method described in EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES. Values represent the mean ± SD (n = 3).

Assay of transglycosylation activity of EGCase I

The transglycosylation reaction of EGCase I was carried out using GM1a as a donor substrate and various alkanols as an acceptor substrate. The reaction mixture contained 2 nmol of GM1a and 1 mU of the enzyme in 20 μ l of 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5, containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 10% 1-alkanols. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the reaction was stopped by heating in a boiling water bath for 5 min. The reaction mixture was evaporated dry, dissolved in 10 μ l of methanol, and applied to a TLC plate, which was then developed with chloroform-methanol-0.02% CaCl2 (5:4:1, v/v/v). GSLs and transglycosylation products were visualized by spraying the TLC plate with orcinol-H2SO4 reagent and quantified with the CS-9300 at 540 nm.

Expression and purification of loop-deleted mutant EGCase II

The Δloop (loop-deleted mutant) EGCase II, which lacks residues from Asn148 to Gly154, was generated by PCR using a PrimeSTAR Mutagenesis Basal Kit (Takara Bio) according to the instructions of the manufacturer with a pTEG3 plasmid containing egcase II C-terminal His6-tagged EGCase II (11) as a template, EGC2Deli-S (5 ′ -CCGGAGGGCGCCATCGGCAACGGCGCA-3 ′ ) as a sense primer, and EGC2Deli-A (5 ′ -CGGCTACCGCGGGAGGCCCCACTAGCG-3 ′ ) as an anti-sense primer. After confirmation of the desired mutations by DNA sequencing, the plasmid containing loop-deleted EGCase II (Δloop) was introduced into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). Transformed cells were grown at 37°C for 12 h in 5 ml of Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml carbenicillin. The culture was then transferred into 500 ml of the same medium and incubated at 25°C until the A600 reached 0.5. Isopropyl β -d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to the culture at a final concentration of 1 mM to cause transcription. After 16 h at 18°C, the cells were harvested by centrifugation (7,500 g for 10 min) and suspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. After sonication for 150 s, cell debris was removed by centrifugation (25,000 g for 30 min at 4°C) then purified on a column of Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow as described above. To perform the Western blotting, proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using a semi-dry blotter (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked with 3% (w/v) skim milk in TBS for 1 h and washed three times with T-TBS (TBS containing 0.02% Tween 20). The membrane was incubated with anti His6 antibody (Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature and washed three times with T-TBS. Then it was incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG goat antibody for 1.5 h at room temperature. After three washes with T-TBS, the membrane was stained with a peroxidase staining kit (Nacalai Tesque) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Kinetic study

For the kinetic analysis, EGCase I (5 ng for GM1a or 10 ng for Gb3Cer) was incubated at 37°C for 10 min in 20 μ l of the reaction buffer. EGCase II and the Δloop mutant were assayed at 37°C for 10 min (for GM1a) or 60 min (for Gb3Cer) in the reaction buffer with 50 ng (for GM1a) or 400 ng (for Gb3Cer) of enzyme in a total volume of 20 μ l. The concentration of substrates was 1.5–1,500 μ M. The parameters Km and kcat were obtained by fitting the experimental data to the Michaelis-Menten kinetics model.

RESULTS

Molecular cloning of EGCase I from genomic DNA of R. equi M-750

Three EGCases differing in specificity were found in the culture fluid of Rhodococcus sp. M-750 (9), which was recently identified as R. equi. The cloning of EGCase II and III (renamed EGALC) revealed the two enzymes to be homologous in primary structure (26% identity at the amino acid level) (12), suggesting that EGCase I is also homologous to EGCase II and EGALC. Actually, a search using the amino acid sequence of EGCase II or EGALC as a query specified a high-scoring segment pair (HSP) sequence from 4063996 to 4065273 in the R. equi genome database (31). The deduced amino acid sequence of this HSP showed 28% and 29% identity with EGCase II and EGALC, respectively. We cloned the open reading frame (ORF) containing this HSP sequence from the genomic DNA of R. equi strain M-750. The DNA sequence of the cloned ORF showed 89.6% identity with that of corresponding HSP in the genome database. Multiple alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of the ORF with EGCase II and EGALC showed that 8 amino acid residues, which are essential for the catalytic activity of GH5 glycosidases (38), were all conserved in the ORF (Fig. 1). Among the 8 residues, two glutamates, Glu214 and Glu339 at the end of β -strand 4 and 7, were considered as an acid/base catalyst and nucleophile, respectively (12, 17) (Fig. 1). The N-terminal sequence, Ala-Pro-Pro-Pro-Thr-Pro, of the ORF is completely consistent with that previously determined by protein sequencing of the purified EGCase I (Fig. 1) (39), strongly suggesting the ORF encodes EGCase I. The sequence upstream from the N-terminal Ala was predicted to be a secretory signal peptide.

Fig. 1.

Alignments of amino acid sequences of EGCase I and II and EGALC. The deduced amino acid sequences of EGCase I, EGCase II, and EGALC found in R. equi were aligned using Clustal X. Identical and similar residues are shown by white letters on a black background and black letters in an open box, respectively. Amino acid residues conserved in GH family 5 glycosidases are indicated by open arrowheads. Two glutamates, possibly functioning as an acid/base catalyst and nucleophile, respectively, are indicated by closed arrowheads. The secondary structural elements of EGCase II are shown above the amino acid residues of EGCase I.

Purification of the recombinant EGCase I expressed in R. erythropolis

At first, we expressed the recombinant EGCase I in E. coli BL21 (DE3). However, the expression level of the protein was insufficient to characterize this enzyme. Thus, we used a novel rhodococcal expression system with R. erythropolis as the host cell (30) to express the recombinant EGCase I. The expression vector was designed to contain a secretory signal peptide of EGCase I per se at the N-terminal end (Fig. 1) and His6-tag at the C-terminal end. The expression of the recombinant EGCase I was found in the culture supernatant of R. erythropolis transformed with the putative EGCase I gene but not mock transfectant (data not shown). The recombinant enzyme was precipitated by ammonium sulfate from the culture supernatant and purified on a Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow column (Fig. 2A). In a typical experiment, 1 mg of the purified EGCase I was obtained from a 1 L culture of the transformed R. erythropolis.

Substrate specificity of the recombinant EGCase I

The substrate specificity of the recombinant EGCase I was examined using various GSLs (Table 1). The enzyme hydrolyzed various GSLs possessing the β -glucosyl-Cer linkage, i.e., ganglio- and globo-series GSLs, LacCer, although the hydrolysis of GlcCer was very slow under the conditions used (Table 1). On the other hand, GSLs possessing the β -galactosyl-Cer linkage, e.g., TGC, sulfatide, and GM4, were completely resistant to hydrolysis by the enzyme. Sphingomyelin is not a substrate for EGCase I, EGCase II, or EGALC.

TABLE 1.

Substrate specificity of the recombinant EGCase I

| Class and Name | Structure | Hydrolysis (%)a |

| Ganglio-series | ||

| GD1a | NeuAc α 2-3Gal β 1-3GalNAc β 1-4(NeuAc α 2-3)Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer | 100 |

| GD1b | Gal β 1-3GalNAc β 1-4(NeuAc α 2-8NeuAc α 2-3)Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer | 100 |

| GD3 | NeuAc α 2-8NeuAc α 2-3Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer | 100 |

| GM1a | Gal β 1-3GalNAc β 1-4(NeuAc α 2-3)Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer | 100 |

| Fucosyl-GM1a | Fuc α 1-2Gal β 1-3GalNAc β 1-4(NeuAc α 2-3)Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer | 100 |

| GM3 | NeuAc α 2-3Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer | 100 |

| GM4 | NeuAc α 2-3Gal β -Cer | N.D.b |

| Globo-series | ||

| Gb3Cer | Gal α 1-4Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer | 100 |

| Gb4Cer | GalNAc β 1-3Gal α 1-4Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer | 33.9 ± 0.2 (100)c |

| Forssman | GalNAc α 1-3GalNAc β 1-3Gal α 1-4Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer | 25.2 ± 7.7 (47.5 ± 13.9) c |

| LacCer | Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer | 29.9 ± 2.9 (65.9 ± 8.7) c |

| GlcCer | Glc β -Cer | 6.7 ± 0.8 (20.7 ± 1.0) c |

| TGC | Gal β 1-6Gal β 1-6Gal β -Cer | N.D. |

| Sulfatide | HSO3-3Gal β -Cer | N.D. |

| Sphingomyelin | Choline phosphate-Cer | N.D. |

Various GSLs (2 nmol) were incubated at 37°C for 12 h with 1 mU (or 10 mU) of recombinant EGCase I in 20 μ l of 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5, containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Values represent the mean ± SD (n = 3).

The extent of hydrolysis was calculated as follows: hydrolysis (%) = (peak area for oligosaccharide) × 100 / (peak area for oligosaccharide + peak area for remaining substrate).

Not detected.

The number in parenthesis represents the hydrolysis of GSLs by using 10 mU of EGCase I.

Next, the specificity of EGCase I was carefully compared with that of EGCase II using fucoysl-GM1a, Gb3Cer, and Gb4Cer, which are somewhat resistant to hydrolysis by EGCase II (9, 27). The purified EGCase I hydrolyzed these GSLs very efficiently, whereas almost no hydrolysis was observed using the same protein amount of EGCase II (Fig. 2B). Figure 2C shows the time course for the hydrolysis of fucosyl-GM1a and Gb3Cer with the same units of recombinant EGCase I and II (0.4 mU for fucosyl-GM1a and 2.5 mU for Gb3Cer), indicating that EGCase I hydrolyzed these GSLs much faster than did EGCase II (Fig. 2C).

Kinetic parameters of EGCase I and EGCase II

Steady-state kinetic parameters of EGCase I and EGCase II were determined using GM1a (ganglio-series GSL) and Gb3Cer (globo-series GSL). Although the Michaelis constant (Km) of both enzymes was similar for the two substrates (Table 2, EGCase I and EGCase II), the turnover numbers (kcat) of EGCase I toward GM1a and Gb3Cer were 22- and 1,209-fold higher than those of EGCase II, respectively (Table 2, EGCase I and EGCase II), indicating that EGCase I exhibits a high reaction efficiency toward these substrates. Furthermore, the substrate specificity of the enzymes was shown to be clearly different, i.e., the kcat/Km of EGCase II was 44.7-fold higher for GM1a than Gb3Cer, whereas that of EGCase I was only 1.7-fold higher for GM1a than Gb3Cer (Table 2), indicating Gb3Cer is resistant to hydrolysis by EGCase II but not EGCase I. These results indicated that EGCase I shows broad specificity and good reaction efficiency compared with EGCase II.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of EGCase I, EGCase II, and loop-deleted mutant (Δloop) EGCase II

| Substrate | Enzyme | Km | kcat | kcat/Km |

| mM | s − 1 | M − 1s − 1 | ||

| GM1a | EGCase I | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 120 ± 7 | 32 × 10 |

| EGCase II | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 5.7 ± 0.3 | 1.3 × 10 | |

| Δloop EGCase II | 0.34 ± 0.07 | 11 ± 2 | 3.1 × 10 | |

| Gb3Cer | EGCase I | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 85 ± 10 | 19 × 10 |

| EGCase II | 0.23 ± 0.03 | (6.9 ± 0.7) × 10 | 0.30 × 10 | |

| Δloop EGCase II | 0.31 ± 0.02 | (20 ± 2) × 10 | 0.66 × 10 |

Kinetic parameters were determined by quantifying the released oligosaccharides and remaining GSLs using TLC chromatoscanner. Values represent the mean ± SD (n = 3).

General properties of the recombinant EGCase I

The recombinant EGCase I showed strong activity under weakly acidic conditions with a maximum pH at 5.5–6.0 when GM1a was used as a substrate (Fig. 3A); this pH optimum was similar to that of EGCase II and EGALC (12). The activity was enhanced by addition of the nonionic detergent Triton X-100 or an organic solvent, such as dimethylformamide (DMF), tetrahydrofuran (THF), or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), into the reaction mixture (Fig. 3B). Like jellyfish EGCase and rhodococcal EGALC, EGCase I catalyzed a transglycosylation reaction by which the oligosaccharide moiety of GM1a was transferred to the primary hydroxyl group of various 1-alkanols (Fig. 3C). Among 1-alkanols tested, EGCase I preferred alkanols with a relatively long carbon chain such as pentanol and hexanol as an acceptor substrate (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Characterization of the recombinant EGCase I. A: pH dependency of the recombinant EGCase I for the hydrolysis of GSLs. Fifty millimolar sodium acetate buffer (open square, pH 3.5–6.0) and Tris-HCl buffer (closed square, pH 6.5–8.0) were used. B: Effects of the detergent and organic solvents on the hydrolysis of GM1a by EGCase I. GM1a (2 nmol) was incubated with 0.1 mU of the recombinant EGCase I in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5, at 37°C for 1 h. C: Transglycosylation activity toward several 1-alkanols by EGCase I. GM1a (2 nmol) was incubated with 1 mU of the recombinant EGCase I in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5, containing organic solvent at a concentration of 10% (v/v) at 37°C for 30 min. Values represent the mean ± SD (n = 3).

Mechanical insights into the difference in reaction efficiency between EGCase I and EGCase II

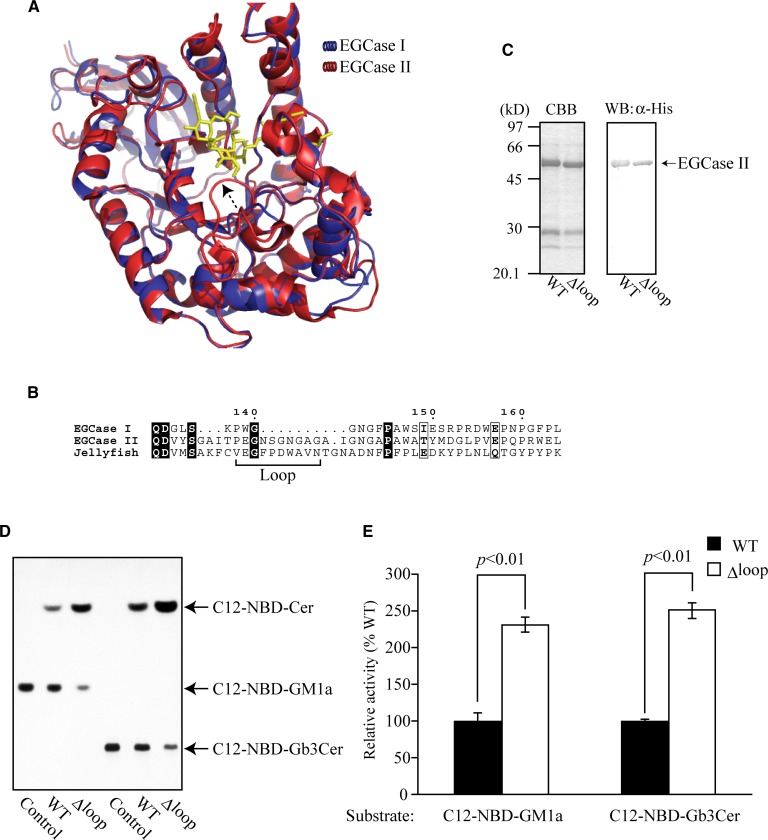

A three-dimensional model of EGCase I was generated by homology modeling using the crystal structure of EGCase II (17) as a template (Fig. 4A , blue). The model showed a (β / α)8 barrel structure typical for GH family 5 glycosidase. The crystal structure of EGCase II shows a highly disordered and flexible loop region (Pro145 to Gly154) hanging over the active site (17). This region was absent in EGCase I (Fig. 4A, B). Jellyfish EGCase (15), with similar specificity to EGCase II but not EGCase I, also possessed the random coil loop at the corresponding position (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Mechanical insights into the difference in reaction efficiency between EGCase I and EGCase II. A: Superposition of the structures of EGCase I (model) and EGCase II (crystal, Protein Data Bank code 2osx). Dotted arrow denotes the EGCase II-specific flexible loop. B: Alignment of amino acid sequences of EGCase I and II and jellyfish EGCase around the flexible loop. C: CBB-staining (left panel) and Western blotting (right panel) of the purified wild-type (WT) and loop-deleted mutant (Δloop) EGCase II. D: TLC showing the fluorescent Cers released from 0.4 nmol of C12-NBD-labeled GM1a and Gb3Cer by WT and Δloop EGCase II. Each GSL was incubated with 50 ng (GM1a) and 400 ng (Gb3Cer) of WT and Δloop EGCase II for 10 min (GM1a) or for 60 min (Gb3Cer). Fluorescent Cer and GSLs were quantified with the fluorescent detector (excitation 475, emission 525 nm). E: Relative activities of WT and Δloop EGCase II toward C12-NBD-GM1a and C12-NBD-Gb3Cer. Values represent the mean ± SD (n = 3).

To examine the effect of a flexible loop on the specificity and reaction efficiency of EGCase II, a mutant EGCase II (Δloop) which lacks the region (Asn148 – Gly154) was generated and purified (Fig. 4C). The activity of the purified mutant was increased about 2.5-fold compared with that of the wild-type EGCase II when measured using GM1a and Gb3Cer as a substrate (Fig. 4D, E). A steady-state kinetic analysis indicated that kcat and kcat/Km values were significantly increased, but the Km value was almost the same as that of the wild-type enzyme (Table 2, EGCase II, and Δloop EGCase II). These results indicate that the loop is a critical factor affecting the turnover of substrates and products in the catalytic region of EGCase II.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we cloned the gene encoding EGCase I and showed a reproducible and efficient method to prepare a recombinant enzyme using a rhodococcal expression system. The recombinant EGCase I efficiently hydrolyzed globo-series GSLs and fucosyl-GM1a (Fig. 2), which are strongly resistant to hydrolysis by EGCase II (9, 11, 27). EGCase II is currently used to obtain intact oligosaccharides and Cers from GSLs. However, EGCase I would be more useful for this purpose because of the broad specificity and good reaction efficiency shown in this study.

EGCase or Cer glycanase has been found in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, i.e., actinomycetes (Rhodococcus sp. and Corynebacterium sp.) (7, 40, 41), leeches (Hirudo medicinalis and Macrobdella decora) (8, 13), hard-shelled clams (Merecenaria merecenaria) (20), earthworms (Lumbricus terrestaris) (14), jellyfish (Cyanea nozakii) (15), and hydra (Hydra magnipapillata) (16). The EGCases from the jellyfish and hydra exhibit the EGCase II-like specificity, i.e., they hydrolyzed ganglio-series GSLs much faster than globo-series GSLs (15, 16), whereas the enzymes from the leech and earthworm show an EGCase I-like specificity, i.e., the enzymes hydrolyzed globo-series GSLs as well as ganglio-series GSLs with a similar efficiency (13, 42). In this context, the leech enzyme is also useful for the preparation of oligosaccharides from various GSLs (22). However, the gene encoding it has yet to be cloned, and thus, a recombinant enzyme is not available at present.

EGCase I, like other EGCases (7, 8, 12, 15), required a detergent for the efficient hydrolysis of GSLs (Fig. 3B), possibly because GSL substrates are hydrophobic and do not dissolve well in the reaction buffer without a detergent. Triton X-100 was effective for the hydrolysis of GSLs by EGCase I (Fig. 3B); however, it is not easy to remove after the reaction, interfering with the analysis of GSL-oligosaccharides by the MS analysis. Alternatively, organic solvents such as DMF, THF, and DMSO were found to be effective for the hydrolysis of GSLs by EGCase I in place of detergents (Fig. 3B). The use of organic solvents, which could be removed by drying under N2 gas or Speed-Vac concentrator, did not affect the MS analysis.

We found that EGCase I catalyzes a transglycosylation reaction, which transfers the sugar moiety of GSLs to the primary hydroxyl group of several 1-alkanols (Fig. 3C). Previously, we utilized the transglycosylation reaction of EGALC to label the oligosaccharide moiety of GSLs with fluorescent alkanols (43). The fluorescent oligosaccharides obtained were successfully separated by TLC as well as HPLC, and were sensitively detected by a fluorescent detector (16). Using the EGCase I, transglycosylation-based direct fluorescent labeling could be applicable for various GSLs including globo-series GSLs.

A comparison of the three-dimensional structure of EGCase II (crystal) and EGCase I (model) may provide mechanical insights into the difference in the efficiency of these two enzymes. That is, a flexible loop hanging over the catalytic cleft is present in EGCase II but not EGCase I. The complex structure of EGCase II with GM3 (NeuAc α 2-3 Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer) revealed that the 4-hydroxyl group of the internal β -galactose in GM3 is located close to the loop (17). On the other hand, the 4-hydroxyl group is substituted with α -galactose in globo-series GSLs such as Gb3Cer (Gal α 1-4Gal β 1-4Glc β -Cer), suggesting that the presence of a loop could affect the turnover of substrates and products in the catalytic region. The loop is completely lacking in EGCase I (Fig. 4A, B), which may be why EGCase I hydrolyzes Gb3Cer much faster than EGCase II. Actually, the deletion of the loop in the mutant EGCase II (Δloop EGCase II) improved the hydrolysis of Gb3Cer (Fig. 4D, E). The kinetic analysis indicated that the turnover number (kcat) of Δloop EGCase II increased but the Km value was unchanged compared with the wild-type EGCase II (Table 2). These results may indicate that this loop is not likely to interfere with the binding of the substrate to the active site but rather inhibits the release of products from the active site. Elucidating the complex crystal structure of EGCase I with Gb3Cer is required for further analysis of the interaction between the substrate and enzyme, and this is being attempted in our laboratory.

A high-throughput analysis of GSLs was conducted using oligosaccharides obtained by the ozonolysis of GSLs (44). However, the chemical method resulted in a low yield of GSL-oligosaccharides (6). Furthermore, intact Cers were not obtained. The use of EGCase provided intact oligosaccharides as well as Cers from GSLs with a high yield. Recently, Fujitani et al. (24) reported a comprehensive analysis of GSLs in various cells by EGCase-based cleavage of GSLs, followed by glyco-blotting and MALDI-TOF/TOF MS analysis. They indicated that the use of a mixture of EGCase I and II is effective for detaching the GSL-oligosaccharides quantitatively from various cells, because EGCase I hydrolyzed efficiently globo-series GSLs and EGCase II, lacto-series GSLs (9).

EGCase I, occasionally in combination with EGCase II, depending on the species of GSLs in samples, could become a powerful tool for the comprehensive analysis of GSLs, and may lead to the discovery of GSLs as new biomarkers of diseases and different cell lineages.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- CBB

- Coomassie Brilliant Blue

- DMF

- dimethylformamide

- EGALC

- endogalactosylceramidase

- EGCase

- endoglycoceramidase

- Cer

- ceramide

- GH

- glycoside hydrolase

- GSL

- glycosphingolipid

- HSP

- high-scoring segment pair

- kcat

- turnover number (kcat)

- Δloop

- loop-deleted mutant

- SSEA

- stage-specific embryonic antigen

- TGC

- trigalactosylCer

- THF

- tetrahydrofuran

This work was supported in part by the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (M.I.), Basic Research B from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (M.I.), and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists (Y.I.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Hakomori S., Wang S. M., Young W. W., Jr 1977. Isoantigenic expression of Forssman glycolipid in human gastric and colonic mucosa: its possible identity with ‘A like antigen’ in human cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 74: 3023–3027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannagi R., Cochran N. A., Ishigami F., Hakomori S., Andrews P. W., Knowles B. B., Solter D. 1983. Stage-specific embryonic antigens (SSEA-3 and -4) are epitopes of a unique globo-series ganglioside isolated from human teratocarcinoma cells. EMBO J. 2: 2355–2361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi K., Tanabe K., Ohnuki M., Narita M., Ichisaka T., Tomoda K., Yamanaka S. 2007. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 131: 861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiegandt H., Bucking H. W. 1970. Carbohydrate components of extraneuronal gangliosides from bovine and human spleen, and bovine kidney. Eur. J. Biochem. 15: 287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakomori S. I. 1966. Release of carbohydrates from sphingoglycolipid by osmium-catalyzed periodate oxidation followed by treatment with mild alkali. J. Lipid Res. 7: 789–792 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yowler B. C., Stoehr S. A., Schengrund C. L. 2001. Oxidation and base-catalyzed elimination of the saccharide portion of GSLs having very different polarities. J. Lipid Res. 42: 659–662 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito M., Yamagata T. 1986. A novel glycosphingolipid-degrading enzyme cleaves the linkage between the oligosaccharide and ceramide of neutral and acidic glycosphingolipids. J. Biol. Chem. 261: 14278–14282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S. C., Degasperi R., Muldrey J. E., Li Y. T. 1986. A unique glycosphingolipid-splitting enzyme (ceramide-glycanase from leech) cleaves the linkage between the oligosaccharide and the ceramide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 141: 346–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito M., Yamagata T. 1989. Purification and characterization of glycosphingolipid-specific endoglycosidases (endoglycoceramidases) from a mutant strain of Rhodococcus sp. Evidence for three molecular species of endoglycoceramidase with different specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 264: 9510–9519 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prescott J. F. 1991. Rhodococcus equi: an animal and human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4: 20–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Izu H., Izumi Y., Kurome Y., Sano M., Kondo A., Kato I., Ito M. 1997. Molecular cloning, expression, and sequence analysis of the endoglycoceramidase II gene from Rhodoccocus species strain M-777. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 19846–19850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishibashi Y., Nakasone T., Kiyohara M., Horibata Y., Sakaguchi K., Hijikata A., Ichinose S., Omori A., Yasui Y., Imamura A., et al. 2007. A novel endoglycoceramidase hydrolyzes oligogalactosylceramides to produce galactooligosaccharides and ceramides. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 11386–11396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou B., Li S. C., Laine R. A., Huang R. T., Li Y. T. 1989. Isolation and characterization of ceramide glycanase from the leech, Macrobdella decora. J. Biol. Chem. 264: 12272–12277 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter B. Z., Li S. T., Li Y. T. 1992. Ceramide glycanase from the earthworm, Lumbricus terrestris. Biochem. J. 285: 619–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horibata Y., Okino N., Ichinose S., Omori A., Ito M. 2000. Purification, characterization, and cDNA cloning of a novel acidic endoglycoceramidase from the jellyfish, Cyanea nozakii. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 31297–31304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horibata Y., Sakaguchi K., Okino N., Iida H., Inagaki M., Fujisawa T., Hama Y., Ito M. 2004. Unique catabolic pathway of glycosphingolipids in a hydrozoan, Hydra magnipapillata, involving endoglycoceramidase. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 33379–33389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caines M. E. C., Vaughan M. D., Tarling C. A., Hancock S. M., Warren R. A. J., Withers S. G., Strynadka N. C. J. 2007. Structural and mechanistic analyses of endo-glycoceramidase II, a membrane-associated family 5 glycosidase in the apo and GM3 ganglioside-bound forms. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 14300–14308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higashi H., Ito M., Fukaya N., Yamagata S., Yamagata T. 1990. Two-dimensional mapping by the high-performance liquid chromatography of oligosaccharides released from glycosphingolipids by endoglycoceramidase. Anal. Biochem. 186: 355–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohara K., Sano M., Kondo A., Kato I. 1991. Two-dimensional mapping by high-performance liquid chromatography of pyridylamino oligosaccharides from various glycosphingolipids. J. Chromatogr. 586: 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basu S. S., Dastgheibhosseini S., Hoover G., Li Z. X., Basu S. 1994. Analysis of glycosphingolipids by fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis using ceramide glycanase from Mercenaria mercenaria. Anal. Biochem. 222: 270–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wing D. R., Garner B., Hunnam V., Reinkensmeier G., Andersson U., Harvey D. J., Dwek R. A., Platt F. M., Butters T. D. 2001. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of ganglioside carbohydrates at the picomole level after ceramide glycanase digestion and fluorescent labeling with 2-aminobenzamide. Anal. Biochem. 298: 207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neville D. C., Coquard V., Priestman D. A., te Vruchte D. J., Sillence D. J., Dwek R. A., Platt F. M., Butters T. D. 2004. Analysis of fluorescently labeled glycosphingolipid-derived oligosaccharides following ceramide glycanase digestion and anthranilic acid labeling. Anal. Biochem. 331: 275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlsson H., Halim A., Teneberg S. 2010. Differentiation of glycosphingolipid-derived glycan structural isomers by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Glycobiology. 20: 1103–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujitani N., Takegawa Y., Ishibashi Y., Araki K., Furukawa J., Mitsutake S., Igarashi Y., Ito M., Shinohara Y. 2011. Qualitative and quantitative cellular glycomics of glycosphingolipids based on rhodococcal endoglycosylceramidase-assisted glycan cleavage, glycoblotting-assisted sample preparation, and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization tandem time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 41669–41679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horibata Y., Higashi H., Ito M. 2001. Transglycosylation and reverse hydrolysis reactions of endoglycoceramidase from the jellyfish, Cyanea nozakii. J. Biochem. 130: 263–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishibashi Y., Kiyohara M., Okino N., Ito M. 2007. Synthesis of fluorescent glycosphingolipids and neoglycoconjugates which contain 6-gala oligosaccharides using the transglycosylation reaction of a novel endoglycoceramidase (EGALC). J. Biochem. 142: 239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu X., Monjusho H., Inagaki M., Hama Y., Yamaguchi K., Sakaguchi K., Iwamori M., Okino N., Ito M. 2007. Fucosyl-GM1a, an endoglycoceramidase-resistant ganglioside of porcine brain. J. Biochem. 141: 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsubara T., Hayashi A. 1981. Structural studies on glycolipid of shellfish. III. Novel glycolipids from Turbo cornutus. J. Biochem. 89: 645–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakagawa T., Tani M., Kita K., Ito M. 1999. Preparation of fluorescence-labeled GM1 and sphingomyelin by the reverse hydrolysis reaction of sphingolipid ceramide N-deacylase as substrates for assay of sphingolipid-degrading enzymes and for detection of sphingolipid-binding proteins. J. Biochem. 126: 604–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakashima N., Tamura T. 2004. A novel system for expressing recombinant proteins over a wide temperature range from 4 to 35 degrees C. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 86: 136–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Letek M., Gonzalez P., Macarthur I., Rodriguez H., Freeman T. C., Valero-Rello A., Blanco M., Buckley T., Cherevach I., Fahey R., et al. 2010. The genome of a pathogenic rhodococcus: cooptive virulence underpinned by key gene acquisitions. PLoS Genet. 6: e1001145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D. G. 1997. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 4876–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gouet P., Robert X., Courcelle E. 2003. ESPript/ENDscript: extracting and rendering sequence and 3D information from atomic structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 3320–3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martí-Renom M. A., Stuart A. C., Fiser A., Sánchez R., Melo F., Šali A. 2000. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29: 291–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. 1993. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 26: 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones D. T. 1999. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 292: 195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laemmli U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 227: 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakon J., Adney W. S., Himmel M. E., Thomas S. R., Andrew Karplus P. 1996. Crystal structure of thermostable family 5 endocellulase E1 from Acidothermus cellulolyticus in complex with cellotetraose. Biochemistry. 35: 10648–10660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ito M., Ikegami Y., Yamagata T. 1991. Activator proteins for glycosphingolipid hydrolysis by endoglycoceramidases: elucidation of biological functions of cell-surface glycosphingolipids in situ by endoglycoceramidases made possible using these activator proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 266: 7919–7926 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ashida H., Yamamoto K., Kumagai H., Tochikura T. 1992. Purification and characterization of membrane-bound endoglycoceramidase from Corynebacterium sp. Eur. J. Biochem. 205: 729–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakaguchi K., Okino N., Sueyoshi N., Izu H., Ito M. 2000. Cloning and expression of gene encoding a novel endoglycoceramidase of Rhodococcus sp. strain C9. J. Biochem. 128: 145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y. T., Li S. C. 1989. Ceramide glycanase from leech, Hirudo medicinalis, and earthworm, Lumbricus terrestris. Methods Enzymol. 179: 479–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishibashi Y., Nagamatsu Y., Meyer S., Imamura A., Ishida H., Kiso M., Okino N., Geyer R., Ito M. 2009. Transglycosylation-based fluorescent labeling of 6-gala series glycolipids by endogalactosylceramidase. Glycobiology. 19: 797–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagahori N., Abe M., Nishimura S. 2009. Structural and functional glycosphingolipidomics by glycoblotting with an aminooxy-functionalized gold nanoparticle. Biochemistry. 48: 583–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]