Abstract

AIM: To investigate the genomic copy number alterations that may harbor key driver genes in gastric tumorigenesis.

METHODS: Using high-resolution array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), we investigated the genomic alterations of 20 advanced primary gastric adenocarcinomas (seventeen tubular and three mucinous) of Chinese patients from the Jilin province. Ten matching adjacent normal regions from the same patients were also studied.

RESULTS: The most frequent imbalances detected in these cancer samples were gains of 3q26.31-q27.2, 5p, 8q, 11p, 18p, 19q and 20q and losses of 3p, 4p, 18q and 21q. The use of high-resolution array CGH increased the resolution and sensitivity of the observed genomic changes and identified focal genetic imbalances, which included 54 gains and 16 losses that were smaller than 1 Mb in size. The most interesting focal imbalances were the intergenic loss/homozygous deletion of the fragile histidine triad gene and the amplicons 11q13, 18q11.2 and 19q12, as well as the novel amplicons 1p36.22 and 11p15.5.

CONCLUSION: These regions, especially the focal amplicons, may harbor key driver genes that will serve as biomarkers for either the diagnosis or the prognosis of gastric cancer, and therefore, a large-scale investigation is recommended.

Keywords: Array comparative genomic hybridization, Amplicon, Gastric adenocarcinoma, Oncogene, Fragile histidine triad

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide. Although its incidence has gradually decreased in many Western countries, the incidence of gastric cancer still remains high in South and Central America and is highest in Eastern Asia, specifically in China, South Korea and Japan[1,2]. The most common gastric malignancy is adenocarcinoma[3], which is characterized by multiple genetic instabilities, as are other adenocarcinomas. One of these genetic instabilities is chromosomal instability, a common consequence of a chromosomal or chromosome-segment abnormality, that causes DNA copy number changes during tumor progression. These alterations may lead to a loss of function of tumor suppressor genes (inactivation) and/or a gain of function of oncogenes (activation). High-level DNA copy number changes (amplification/amplicons) in tumors are frequently restricted to certain chromosomal regions containing well-known oncogenes that are also overexpressed or activated[4,5]. Some oncogenes, such as NMYC, LMYC and GLI, were originally discovered because of their genomic amplification in human tumors[4]. An analysis of the composition of DNA amplifications showed that human cancer can be classified via DNA copy number profiling because such amplifications are non-randomly selected with respect to the biological backgrounds of cancer[6]. Therefore, the detection and discovery of unidentified or incompletely described amplicons and relevant genes located within these amplicons can lead to the identification of genes putatively involved in growth control and tumorigenesis.

Recently available whole-genome array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), a high-throughput genomic technology, facilitates the accumulation of high-resolution data of genomic imbalances associated with disease. In this study, we identified possible candidate genes that could provide insight into the pathology of gastric adenocarcinoma through the integration of genomic copy number changes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumor samples

This study included seventeen tubular and three mucinous adenocarcinomas of advanced primary stomach cancer samples from Jilin Province in North-Eastern China (Table 1). Of the twenty samples studied, thirteen were from males and seven were from females. The mean age was 62.1 (ranging from 52 to 76) years. The stage of each tumor was classified according to the tumor node metastasis classification of the International Union Against Cancer. The histopathological grades were as follows: Grade 1 (well-differentiated/low grade adenocarcinoma), no cases; Grade 2 (moderately differentiated/intermediate-grade adenocarcinoma), five (tubular) cases; and Grade 3 (poorly differentiated/high-grade adenocarcinoma), 15 (12 tubular and three mucinous) cases. Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain information concerning postsurgical pathological stages. Tumor samples were obtained surgically in the First Hospital of Jilin University; paired adjacent normal tissue was also collected as a control for comparison with the tumor. All patients had negative histories of exposure to either chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery, and there were no other diagnosed cancers. An informed consent with approval of the ethics committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University was obtained from all participating patients.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics, risk factors and overall genomic imbalances in 20 gastric adenocarcinomas

| No. | ID | Sex/age (yr) | T/N/M stage | Tumor type | Histology grade (differentiated) | Tumor location | Smoke history | Drink history | Genomic size of total gain (Mb) | Genomic size of total loss (Mb) | Net imbalances (Mb) (%)2 |

| 1 | T64 | M/75 | T3/N3/M0 | Tubular | Poorly | Upper (CR), lower (AA) | Y | Y | 290.7 | 147.3 | +143.4 (4.8) |

| 2 | TW0800 | M/65 | T3/N3/M0 | Tubular | Poorly | Upper (CR/GF), central (GB) | N | N | 388.9 | 205.3 | +183.6 (5.6) |

| 3 | T74 | M/58 | T3/N3/M0 | Tubular | Poorly | Central (GB) | N | Y | 290.1 | 412.3 | -122.2 (4.1) |

| 4 | TW0784 | M/75 | T3/N1/M0 | Tubular | Poorly | Upper (CR/GF) | N | N | 3.4 | 0 | +3.4 (0.1) |

| 5 | T66 | M/50 | T3/N2/M0 | Tubular | Poorly | Lower (AA) | N | Y | 34.2 | 0 | +34.2 (1.1) |

| 6 | T78 | F/59 | T3/N1/M0 | Tubular | Poorly | Lower (AA) | N | N | 146.2 | 0 | +107.4 (3.6) |

| 7 | T41 | M/73 | T3/N2/M0 | Tubular | Poorly | Lower (AA/P) | Y | Y | 7.2 | 0 | +7.2 (0.2) |

| 8 | T47 | F/52 | T3/N1/M0 | Tubular | Poorly | Lower (AA) | N | N | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 (0.0) |

| 9 | T38 | F/53 | T2/N1/M0 | Tubular | Poorly | Lower (AA/P) | N | N | 294.3 | 37.4 | +256.9 (8.6) |

| 10 | TW0796 | M/56 | T3/N1/M0 | Tubular | Poorly | Lower (AA/P) | Y | Y | 224.4 | 11.9 | +212.5 (7.1) |

| 11 | TW0807 | M/54 | T3/N0/M0 | Tubular | Poorly | Lower (AA/P) | Y | Y | 191.7 | 43.7 | +148.0 (4.9) |

| 12 | TW0813 | F/57 | T3/N2/M0 | Tubular1 | Poorly | Lower (AA/P) | N | N | 76.1 | 54.6 | +21.5 (0.7) |

| 13 | T52 | M/73 | T3/N2/M0 | Tubular | Moderately | Upper (CR/GF) | N | N | 333.9 | 361.8 | -27.9 (0.9) |

| 14 | TW0797 | M/62 | T3/N1/M0 | Tubular | Moderately | Upper (CR/GF) | N | Y | 161.1 | 0 | +161.1 (5.4) |

| 15 | TW0782 | M/53 | T3/N2/M0 | Tubular | Moderately | Upper (CR/GF) | Y | N | 290.1 | 108.3 | +181.8 (6.1) |

| 16 | TW0780 | F/59 | T2/N0/M0 | Tubular | Moderately | Lower (AA/P) | N | N | 4.1 | 4.16 | -0.06 (0.0) |

| 17 | T75 | M/69 | T3/N2/M0 | Tubular | Moderately | Lower (AA) | Y | Y | 28 | 0 | +28.0 (0.9) |

| 18 | T76 | F/59 | T3/N1/M0 | Mucinous | Poorly | Upper (CR/GF) | Y | Y | 99.1 | 0 | +99.1 (3.3) |

| 19 | TW0789 | M/64 | T3/N1/M0 | Mucinous | Poorly | Lower (AA/P) | N | N | 504.5 | 167.6 | +336.9 (11.2) |

| 20 | TW0774 | F/76 | T3/N3/M0 | Mucinous | Poorly | Lower (AA/P) | N | N | 41.4 | 90.4 | -49.0 (1.6) |

Signet ring cell;

Percent of net imbalances calculated based on 3000 Mb of genome size. F: Female; M: Male; T: Tumor; N: Node; M: Metastasis ; CR: Cardiac region; GF: Gastric fundus; GB: Gastric body; AA: Antral area; P: Pylorus; Y: Yes; N: No.

Twenty tumor samples and ten paired adjacent normal tissues were snap-frozen after surgical resection and stored at -80 °C. DNA was isolated from the tumor tissue by proteinase K digestion followed by phenol-chloroform extraction according to standard protocols.

Array CGH assay

Array CGH was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modifications on a 385k oligonucleotide chip (Roche/NimbleGen Systems Inc., Madison, WI). Commercially available pooled normal control DNA (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) was used for reference. The patient DNA and the reference DNA were labeled with either cyanine 3 (Cy-3) or cyanine 5 (Cy-5) by random priming (Trilink Biotechnologies, San Diego, CA) and then hybridized to the chip via incubation in the MAUI hybridization system (BioMicro Systems, Salt Lake City, UT). After 18-h hybridization at 42 °C, the slides were washed and scanned using a GenePix 4000B (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Statistical analysis

Profile smoothing and breakpoint detection were performed with NimbleScan version 2.4 and SignalMap version 1.9 (NimbleGen Systems). If a smoothed copy number log2 ratio was above 0.15 or below -0.15 across five neighboring probes, it was defined as a gain or a loss, respectively. Amplifications were defined as those with a smoothed DNA copy number ratio above 0.5.

RESULTS

Overview of genomic imbalances in 20 primary gastric adenocarcinomas

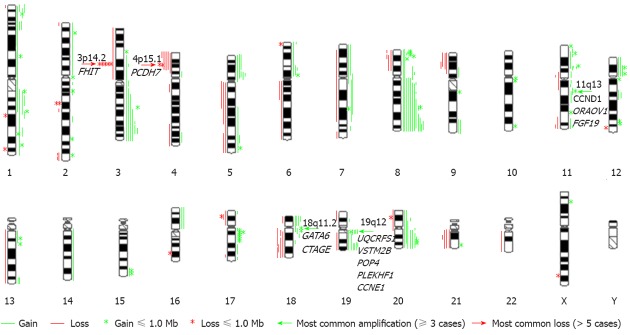

An overview of genomic imbalances in the twenty advanced primary gastric adenocarcinomas is shown in Figure 1. Genomic copy number changes (gains, losses, amplifications or homozygous deletions) were detected in all cases except one. Net gains (15 cases) of genetic material were more frequent than net losses (4 cases). The sizes of the net genomic imbalances per sample ranged from a loss of 122.2 Mb (4.1% of genome) to a gain of 336.9 Mb (11.2% of genome) (Table 1). The mean number of gains per case was 9.0, ranging from 0 to 40, and the mean number of losses per case was 3.5, ranging from 0 to 14. The gain sizes ranged from 56.3 kb to 158.6 Mb, and the loss sizes ranged from 150.1 kb to 131 Mb. Approximately 28% (70/250) of the genomic imbalances were smaller than 1 Mb; from this subset, 21.6% (54/250) of the total imbalances were gains, and 6.4% (16/250) were losses. The most frequent genomic imbalances detected in these cancer samples were gains of 3q26.31-q27.2 (6/20), 5p (5/20), 8q [12/20: 8q22.2-q22.3 (10), 8q24.13-q24.22 (12)], 11p (6/20), 18p (4/20), 19q (8/20) and 20q (8/20) and losses of 3p14.2 (6/20), 4p15.1 (6/20), 18q21.2-q22.1 (4/20) and 21q21.1-q21.2 (4/20). However, no genomic imbalances were detected in the ten paired adjacent tissues, demonstrating that these genomic imbalances are tumor related.

Figure 1.

An overview of genomic imbalances in 20 primary gastric adenocarcinomas. The total number of gains was 180 (54 ≤ 1 Mb), and the total number of losses was 70 (16 ≤ 1 Mb). Partial or whole gains of 8q (12/20), 19q (8/20), and 20q (8/20) were most frequent. The most common amplicons were of the 11q13, 18q11.2 and 19q12 regions (green arrows). The loss of the FHIT gene and the partial loss of 4p with the smallest region of overlap including the PCDH7 gene were the most frequent losses (red arrow).

Genomic regions with amplification: Possible diagnostic marker loci

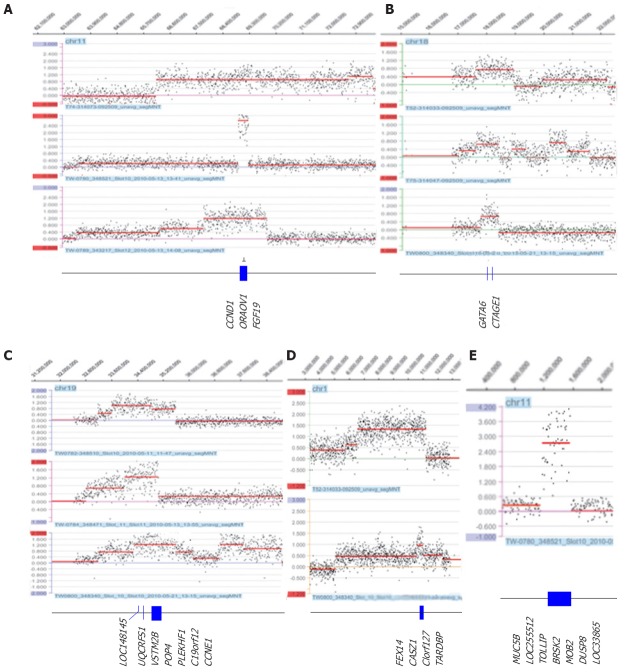

The most prominent feature in this study was the amplicons of 11q13 (two tubular and one mucinous), 18q11.2 (three tubular) and 19q12 (three tubular), as well as the novel amplicons 1p36.22 (two tubular) and 11p15.5 (three tubular) (Table 2 and Figure 2). Amplification of 11q13 had the smallest region of overlap (SRO) of 343.7 kb, which included the CCND1, ORAOV1 and FGF19 genes. Amplification of 18q11.2 had an SRO of 625.0 kb, which included the GATA6 and CTAGE genes. Amplification of 19q12 had an SRO of 1.4 Mb, which included nine genes: LOC148145, LOC10050583, UQCRFS1, LOC284395, VSTM2B, POP4, PLEKHF1, C19orf12 and cyclin E1 (CCNE1). The SRO of the novel amplification 1p36.22 was 418.7 kb and included FEX14, CASZ1, C1orf127 and TARDBP. The SRO of the other novel amplification, 11p15.5, was 343.7 kb and included MUC5B, LOC255512, TOLLIP, BRSK2, HCCA2, DUSP8 and LOC338865. Other regions in which amplification was detected were 8p23.1, 8q24.21, 10q26.12q26.13, 11q13, 12p12.1, 12q15, 17q12 and 20q13.2; these regions are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Amplification segments and the genes involved

| Chr. region | Amp | Gain | SRO, bp (hg 18) | Size (kb) | Genes | Selected references |

| 1p36.221 | 2 | 1 | 10 587 540-11 006 299 | 418.7 | PEX14, CASZ1, C1orf127, TARDBP | N/A |

| 1q21.2 | 1 | 3 | 148 737 723-149 062 575 | 324.9 | TARS2, ECM1, ADAMTSL43, MCL13, ENSA2, GOLPH3L, HORMAD13, CTSS, CTSK, ARNT2 | Gastric cancer[7], adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction[8]3, basal/luminal breast cancer[9]3, hepatocellular carcinoma[10] |

| 8p23.1 | 2 | 3 | 10 475 239-10 562 632 10 681 251-10 943 920 11 250 228-11 887 602 | 87.4 262.7 637.4 | RP1 L1 PINX1, XKR6 TDH, FAM167A, BLK, GATA4234, NEIL22, FDFT123, CTSB23 | Gastric cancer[7,11], esophageal adenocarcinoma[12,13]3,[14],[15]3, adenocarcinomas of the gastroesophageal junction[16]3, small bowel adenocarcinoma[17] |

| 8q24.21 | 1 | 11 | 128 331 422-128 837 626 | 506.2 | POU5F1B, LOC727677, MYC23 | Various cancer[5], esophageal adenocarcinoma[14], gastric cancer[18],[19]2,[20], papillary renal cell carcinoma[21]3 |

| 10q26.12 | 1 | 0 | 121 881 486-123 931 430 | 2050.0 | PPAPDC1A, LOC283089, WDR11, FGFR23, ATE13, NSMCE4A3, TACC23 | Breast cancer[22]3, gastric carcinoma[20] |

| 10q26.13 | 126 212 750-126 362 686 | 149.9 | LHPP, FAM53B | |||

| 11p15.51 | 1 | 0 | 1 175 114-1 556 281 | 381.2 | MUC5B, LOC255512, TOLLIP, BRSK2, HCCA2, DUSP8, LOC33865 | N/A |

| 11p13 | 2 | 1 | 34 675 094-35 068 916 | 393.8 | APIP3, PDHX3 | Breast cancer[23], gastric cancer cell line[24], head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell line[25]3 |

| 11q13.2q13.3 | 3 | 0 | 68 912 663-69 256 388 | 343.7 | CCND123, ORAOV123, FGF193 | Various cancers[5], gastric cancer[7,11,20],[26]2, hepatocellular carcinoma[27]2, esophageal adenocarcinoma[14], esophageal and gastric cancer[26], esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[28]3, laryngeal/pharyngeal cancer[29]3 |

| 12p12.1 | 2 | 2 | 25 150 060-25 437 736 | 287.7 | LRMP3, CASC1, LYRM5, KRAS23 | Various cancers[5], esophageal adenocarcinoma[14], gastric cancer[11,20],[30]2, ovarian cancer[31]3 |

| 12q15 | 2 | 0 | 67 475 003-67 875 102 68 037 717-68 318 830 | 400.1 281.1 | MDM22, CPM YEATS4 (GAS41)3, FRS23, CCT23, LRRC10 | Various cancers[5], esophageal adenocarcinoma[14], gastric cancer[20,32], liposarcomas[33]3, melanoma cell line[34]3 |

| 17q12 | 2 | 1 | 35 000 176-35 150 077 | 149.9 | NEUROD2, PPP1R1B2, STARD32, TCAP, PNMT2, PERLD12, ERBB22, C17orf37, GRB72 | Various cancers[5], gastric cancer[11,20],[35-37]2,[38],[39]2 |

| 18q11.2 | 3 | 2 | 17 800 202-18 425 167 | 625.0 | GATA634, CTAGE1 | Pancreatic carcinoma[40,41]3, esophageal adenocarcinoma[14],[42]3 |

| 19q12 | 3 | 3 | 33 606 476-35 037 396 | 1340.9 | LOC148145, LOC10050583, UQCRFS12, LOC284395, VSTM2B, POP42, PLEKHF12, C19orf122, CCNE12 | Gastric cancer[43]2,[44],[45]2, esophageal/gastric cardiac adenocarcinoma[12] |

| 20q13.2 | 1 | 6 | 51 568 862-51 993 797 | 424.9 | ZNF2173, SUMO1P1, BCAS13 | Esophageal adenocarcinoma[14], adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction[46]3, breast cancer[47], gastric adenocarcinoma[48], glioblastoma[49], various cancers[50] |

Novel amplicon;

Gene and references that are overexpressed when amplified in gastric cancer;

Genes (and references) that are overexpressed when amplified in types of cancer other than gastric cancer;

Underexpression has been reported in gastric cancer. SRO: Smallest region of overlap; N/A: Not available.

Figure 2.

Representative amplifications detected by array comparative genomic hybridization and the genes that are located in the smallest region of overlap. The most common amplicons at 11q13 (A), 18q11.2 (B) and 19q12 (C) and novel amplicons at 1p36.22 (D) and 11p15.5 (E) region (log2 > 0.5). The x-axis indicates the genomic location, and the y-axis indicates the log2 ratio.

The most common losses involved the fragile histidine triad/FRA3B and PDCH7 genes

Six cases had a loss of the fragile histidine triad (FHIT) gene, which maps to the common fragile site 3p14.2. Five of these were intergenic losses of the FHIT gene, and one of these five cases (T38) showed a homozygous deletion. The sizes of these losses ranged from 88.3 kb to 762.5 kb (Table 3 and Figure 3). Another common loss identified in all six cases was the 4p15.1 region (Table 3 and Figure 3). Two cases (TW789 and TW782) had an intergenic loss of the PDCH7 gene.

Table 3.

Summary of losses of FHIT at 3p14.2 and of PDCH7 at 4p15.1

| Gene | Chromosome region | Case | Genomic coordinates (NCBI build 36.3; hg18) | Size (kb) |

| FHIT (HD) | 3p14.2 | T38 | 60 775 135-61 162 550 | 387.4 |

| FHIT | 3p14.2 | TW0789 | 59 762 657-60 525 130 | 762.5 |

| FHIT intron | 3p14.2 | TW800 | 60 781 394-60 987 631 | 206.2 |

| FHIT | 3p14.2 | TW813 | 59 900 085-60 543 794 | 437.5 |

| FHIT etc. | 3pter-p11.2 | T74 | 37 570-88 331 466 | 88 300.0 |

| FHIT intron | 3p14.1 | T782 | 60 343 805-60 493 871 | 150.1 |

| PDCH7 etc. | 4p16.3-p13 | T64 | 2 431 351-44 331 469 | 41 900.0 |

| PDCH7 | 4p15.1 | TW789 | 29 575 024-30 487 701 | 912.7 |

| PDCH7 etc. | 4pter-p14 | TW807 | 191-37 525 019 | 37 500.0 |

| PDCH7 etc. | 4pter-p14 | TW774 | 191-38 356 422 | 38 400.0 |

| PDCH7 | 4p15.1 | TW782 | 30 393 830-30 637 746 | 243.9 |

| PDCH7 etc. | 4pter-p14 | TW813 | 191-38 993 759 | 39 000.0 |

HD: Homozygous deletion.

Figure 3.

Intergenic loss of FHIT/FRA3B on 3p14.2 (A) and PDCH7 on 4p15.1 (B) detected by array comparative genomic hybridization. The x-axis indicates the genomic location, and the y-axis indicates the log2 ratio.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated gene/segmental genomic copy number alterations in twenty advanced primary gastric adenocarcinomas (seventeen tubular and three mucinous) via whole-genome array CGH. We observed that the total number of gains/amplifications (180) was 2.6 times the total number of losses (70). Nineteen out of the 20 cases had genomic imbalances; fifteen of these had net genomic gains (3.4-336.9 Mb), and four of these had net genomic losses (0.06-122.2 Mb), indicating that genomic gains are more common than losses (Figure 1). These findings are compatible with previous findings determined via conventional CGH[7-51]. However, we discovered cryptic genomic imbalances smaller than 1.0 Mb in 28% (70/250) of the total imbalances (with an average of 3.5 per case) and narrowed down the SROs of losses or of gains/amplifications to those including interesting genes or focal genomic segments. These findings are explained by the resolution of the array that we used. The most interesting cryptic imbalances were losses of 3p14.2 and 4p15.1 (Figure 3) and amplifications of 1p36.22, 11p15.5, 11q13, 18q11.2 and 19q12 (Figure 2).

The loss of 3p14.2 in six of our cases encompassed the FHIT gene, which was discovered at the FRA3B locus on the short arm of chromosome 3 and is the most active common chromosome fragile site in the human genome. FHIT’s loss of function as a tumor suppressor gene due to breakage, allelic loss, occasional homozygous deletion and promoter hypermethylation has been evaluated in different types of epithelial tumors, including gastric cancer, which is strongly associated with direct or indirect exposure to environmental carcinogens[52-54]. The FHIT protein is absent in more than 50% of the observed cases, both in gastric cancer cell lines and in primary gastric adenocarcinomas, irrespective of any specific histotype, indicating that alterations of the FHIT gene can play a role in tumorigenicity as an important and preliminary genetic alteration in the cell[55]. However, subsequent additional genetic changes involving other tumor suppressor genes or oncogenes may be necessary for tumor progression. In our six cases who had lost the FHIT gene, five showed an intergenic loss of FHIT, ranging in size from 150 kb to 762.4 kb. One case had a homozygous deletion of part of the FHIT gene (case T36); however, no deletion of this region was found in the normal adjacent tissue of the same case (date not shown). This finding suggests that FHIT loss, not normal copy number variation, is clearly linked to tumorigenicity. However, copy number variations, particularly losses including the FHIT gene, have been reported in the normal population[56], raising the question of whether constitutional copy number loss of the FHIT gene increases tumorigenicity susceptibility.

The other most common loss was of 4p15.1, detected in six cases and encompassing the PDCH7 gene. PDCH7 is an integral membrane protein that is thought to function in cell-cell recognition and adhesion. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) or deletion of this region has been reported in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and in some head and neck squamous cell carcinomas[57,58]. Recently, a genome-wide analysis revealed a single-nucleotide polymorphism in PDCH7 whose risk allele affects overall survival in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer[59].

Gene/chromosomal segment amplifications are thought to reflect genetic instabilities in solid-tumor cells[60]. Such amplifications commonly consist of double minutes (DMs) or homogeneous staining regions or are dispersed at the genomic level; they are usually correlated with protein levels of genes[61]. It has been proposed that the activation of proto-oncogenes by amplification plays an important role in the development of many human solid tumors. Therefore, detection of specific gene amplifications in tumor cells can lead to the identification of genes putatively involved in growth control and tumorigenesis. In our study, we identified the novel amplicons 1p36.22 and 11p15.5 as well as prominent amplicons 11q13, 18q11.2 and 19q12 (≥ 3 cases with amplification).

LOH or the loss of the short arm of chromosome 1, which includes band p36, has been reported in various cancers[62], supporting the possibility that this region encompasses at least one tumor suppressor gene, as opposed to one or more oncogenes. The CASZ1 gene on 1p36, which was amplified in our cases, has been implicated as a candidate tumor suppressor gene in neuroblastomas[63]. However, our study revealed three cases with a gain of 1p36.22. Of these, two cases with high-level amplification of a 418.7 kb SRO, which includes the PEX14, CASZ1, C1orf127 and TARDBP genes, had not previously been reported. Further studies could determine whether this amplification induces overexpression of proteins. The other novel amplicon, found in one case, was the 11p15.5 region, which is 343.7 kb and includes the MUC5B, TOLLIP, BRSK2, HCCA2, DUSP8 and LOC33865 genes. The MUC5B gene encodes a member of the mucin family of proteins, which are highly glycosylated macromolecular components of mucus secretions. This family member is the major gel-forming mucin in mucus. The expression of this gene has been associated with a type of gastric carcinoma but not with the clinical-biological behavior of the tumors[64,65]. The TOLLIP gene encodes a ubiquitin-binding protein that interacts with several toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling cascade components. The TOLLIP protein regulates inflammatory signaling and is involved in interleukin-1 receptor trafficking and the turnover of the IL1R-associated kinase; a possible association with human cancer development has been suggested[66]. The BR serine/threonine kinase 2 (BRSK2) gene acts as a checkpoint kinase upon DNA damage induced by UV irradiation or methyl methane sulfonate[67]. Clinical implications of BRSK2 expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma have been suggested[68]. The hepatocellular carcinoma-associated gene 2 (HCCA2) gene was initially identified as a HCC-specific protein. It was subsequently found to interact with MAD2L2 and might function in cell cycle regulation[69]. The dual specificity phosphatase 8 (DUSP8) gene is a member of the DUSP subfamily. DUSPs inactivate their target kinases by dephosphorylating both the phosphoserine/threonine and phosphotyrosine residues. These genes negatively regulate members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) superfamily (MAPK/ERK, SAPK/JNK, p38), which are involved in cellular proliferation and differentiation. The roles of the DUSPs in the regulation of MAPK activities have been highlighted as part of the oncogenic process[70]. Overall, any of the genes in this region are likely to play an important role in the progression of cancer.

The amplification of 11q13 ranged from 343.7 kb to 20.5 Mb and had an SRO of 343.7 kb, which included the CCND1, ORAOV1 and FGF19 (BLC6) genes. The variously sized 11q13.3 amplicon containing CCND1 is one of the most frequent amplification events in human tumors. Computational genome-wide approaches to identify driver genes have reported CCND1 as one of the most common somatic focal amplifications in human cancers[5]. As shown in our 11q13 amplification, the ORAOV1 and FGH19 genes lie within 15 kb of CCND1, and they are invariably co-amplified with CCND1. However, the limited data show that their expression levels depend on the type of tumor, indicating that the driver gene can be tissue-type dependent/specific. The co-expression of FGH19 with or without CCND1 has been found in HCC, but an absence of FGH19 expression has been found in breast cancer and oral cancer[27]. Future work can determine whether FGH19 is co-expressed with CCND1 in primary gastric adenocarcinoma, even given that recently published whole-genome expression data did not show a significant correlation or co-expression of amplification/expression of CCND1 and FGH19[35,43]. ORAOV1 overexpression has been found in all amplified HCCs; however, ORAOV1 does not promote tumorigenicity in p53-/-; Myc hepatoblasts, nor is it cooperative with FGFR1 or CCND1[27]. A total of four cases in this study had a gain of the 18q11.2 region. Of these, three cases had amplifications ranging from 625.0 kb to 1.3 Mb with an SRO of 625.0 kb, which includes the GATA6 and CTAGE genes. This 18q11.2 amplification, along with expression and epigenetic studies, supports the oncogenic function of GATA6 in esophageal carcinoma, colon cancer and pancreatic cancer[40,42,71,72] but not in gastric adenocarcinoma. Upregulation of GATA6 has been reported in the transition from normal esophageal epithelium to Barrett adenocarcinoma and adenocarcinoma[42,71]. A 0.36 kb amplification including GATA6 and CTAGE1 has been found in pancreatic carcinoma[40,41], and dysregulation (overexpression) of GATA6 contributes to colorectal tumorigenesis and tumor invasion[72]. Moreover, in that study GATA6 was overexpressed not only in the cases with an amplification of GATA6 but also in the cases without amplification[72]. However, CTAGE was rarely overexpressed, indicating that GATA6 is the driver in this amplicon[41] and suggesting that GATA6 overexpression may play a role in the early stages of tumor development. A contradictory result showing underexpression of the GATA6 gene has been reported in gastric adenocarcinoma[36], demonstrating that the oncogenic function of GATA6 in gastric adenocarcinoma needs to be investigated. Our observed amplification of 19q12 with an SRO of 1.4 Mb includes the nine genes LOC148145, LOC10050583, UQCRFS1, LOC284395, VSTM2B, POP4, PLEKHF1, C19orf12 and CCNE1. This 19q12 amplification has been found in gastric cancer and esophageal adenocarcinoma[12,44,45]. Of these genes, CCNE1, an E type cyclin, has traditionally been considered the target of the 19q amplification, which is also one of the most common amplification products in various tumor types[5,12]. However, a comprehensive analysis of the 19q12 amplification in gastric cancer has revealed clustered overexpression of CCNE1 as well as UQCRFS1, POP4, C19orf12 and RMP, indicating potential functions of other genes in this region in tumor development[45]. In ovarian cancer, it has been suggested that the CCNE1 gene is the key driver in this 19q12 amplicon and is correlated with the gain in the 20q11 region that includes the TPX2 gene[73]. It is not clear whether the CCNE1 gene is a key driver in other types of tumors, including gastric cancer tumors, because no detailed study has been conducted; it is also possible that this gene is tissue specific, as shown in 19q12. However, the gain of the 20q11 region is one of the most common findings in gastric cancer, and the correlation between 19q12 and 20q11 in gastric cancer needs to be investigated.

Other amplifications found were 1q21.2 (1 amp/3 gains), 8p23.1 (2 amps/3 gains), 8p23.1 (2 amps/3 gains), 8q24.21 (1 amp/11 gains), 10q26.12q26.13 (1 amp), 11p13 (2 amps/1 gain), 12p12.1 (2 amps/2 gains), 12q15 (2 amps), 17q12 (2 amps/1 gain) and 20q13.2 (1 amp/6 gains). We summarized these amplifications and the expression of the gene(s) corresponding to these amplicons in various primary epithelial tumor and cell lines (Table 2). MCL1 on 1q21.1, MYC on 8q24.21, KRAS on 12p12.1, MDM2 on 12q15, ERBB2 on 17q12 and ZNF217 on 20q13.2 are well-acknowledged oncogenes in several tumors[5]. Recently published data suggest that the same amplifications do not necessarily induce the same gene expression in different tissue types[27], implying that driver genes can be tissue-type specific and making it necessary to acquire and investigate both amplification and overexpression information for different tumor types, even in the case of well-validated oncogenes.

In summary, the array CGH technique allows for comprehensive, rapid and reliable analysis of the whole genome of primary gastric adenocarcinomas and enables the refined and detailed study of amplifications and regions of recurrent copy number change. This approach makes it possible to identify putative oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that may deserve further investigation. In this context, we identified candidate target genes/genomic segments of amplification that may help to direct therapeutics against gastric cancer.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastric cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide. Although its incidence has gradually decreased in many Western countries, the incidence of gastric cancer still remains high in South and Central America and is highest in Eastern Asia, specifically in China, South Korea and Japan. Searching for biomarkers for gastric cancer has proven to be quite challenging.

Research frontiers

Cancer is a genetic disease that involves multiple genetic alterations. Understanding the molecular profile of tumor tissue is crucial for efficiently targeting cancer cells. In this study, the authors identified possible candidate target genes that could provide insight into the pathogenesis of gastric adenocarcinoma through the integration of genomic copy number changes.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Recent reports have highlighted the oncogenic addiction associated with oncogene amplification as a driver gene in carcinogenesis and target treatments. In this research paper, the authors identified novel amplicons that have not been published previously and that could be new target sites for potential diagnosis, prognosis and treatment.

Applications

To learn how these new amplicons are induced and change gene expression, this study may represent a future strategy for therapeutic intervention in the treatment of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma.

Peer review

The paper was designed to be a proof of principle for using cytogenomic microarrays on a larger study to ascertain biomarkers for various gastric neoplasms. The authors did a very thorough analysis of the genetic alterations and of the discussion of the possible genes involved. As claimed, they showed the power of the cytogenomic microarray in detecting common genetic alterations in various gastric tumors. The study was organized in a very clear manner and each common abnormality was compared in a thoughtful manner.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Hitoshi Tsuda, MD, PhD, Diagnostic Patho-logy Section, Clinical Laboratory Division, National Cancer Center Hospital, 5-1-1 Tsukiji, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0045, Japan; Dr. Debra F Saxe, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322, United States

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasako M, Inoue M, Lin JT, Khor C, Yang HK, Ohtsu A. Gastric Cancer Working Group report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40 Suppl 1:i28–i37. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MG, Hold GL, Tahara E, El-Omar EM. Cellular and molecular aspects of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2979–2990. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i19.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brison O. Gene amplification and tumor progression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1155:25–41. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(93)90020-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, Barretina J, Boehm JS, Dobson J, Urashima M, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myllykangas S, Tikka J, Böhling T, Knuutila S, Hollmén J. Classification of human cancers based on DNA copy number amplification modeling. BMC Med Genomics. 2008;1:15. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura Y, Noguchi T, Kawahara K, Kashima K, Daa T, Yokoyama S. Genetic alterations in 102 primary gastric cancers by comparative genomic hybridization: gain of 20q and loss of 18q are associated with tumor progression. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:1328–1337. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isinger-Ekstrand A, Johansson J, Ohlsson M, Francis P, Staaf J, Jönsson M, Borg A, Nilbert M. Genetic profiles of gastroesophageal cancer: combined analysis using expression array and tiling array--comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;200:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adélaïde J, Finetti P, Bekhouche I, Repellini L, Geneix J, Sircoulomb F, Charafe-Jauffret E, Cervera N, Desplans J, Parzy D, et al. Integrated profiling of basal and luminal breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11565–11575. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong N, Chan A, Lee SW, Lam E, To KF, Lai PB, Li XN, Liew CT, Johnson PJ. Positional mapping for amplified DNA sequences on 1q21-q22 in hepatocellular carcinoma indicates candidate genes over-expression. J Hepatol. 2003;38:298–306. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vauhkonen H, Vauhkonen M, Sajantila A, Sipponen P, Knuutila S. Characterizing genetically stable and unstable gastric cancers by microsatellites and array comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;170:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin L, Aggarwal S, Glover TW, Orringer MB, Hanash S, Beer DG. A minimal critical region of the 8p22-23 amplicon in esophageal adenocarcinomas defined using sequence tagged site-amplification mapping and quantitative polymerase chain reaction includes the GATA-4 gene. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1341–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes SJ, Glover TW, Zhu XX, Kuick R, Thoraval D, Orringer MB, Beer DG, Hanash S. A novel amplicon at 8p22-23 results in overexpression of cathepsin B in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12410–12415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu J, Ajani JA, Hawk ET, Ye Y, Lee JH, Bhutani MS, Hofstetter WL, Swisher SG, Wang KK, Wu X. Genome-wide catalogue of chromosomal aberrations in barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: a high-density single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:1176–1186. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goh XY, Rees JR, Paterson AL, Chin SF, Marioni JC, Save V, O’Donovan M, Eijk PP, Alderson D, Ylstra B, et al. Integrative analysis of array-comparative genomic hybridisation and matched gene expression profiling data reveals novel genes with prognostic significance in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2011;60:1317–1326. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.234179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Dekken H, Tilanus HW, Hop WC, Dinjens WN, Wink JC, Vissers KJ, van Marion R. Array comparative genomic hybridization, expression array, and protein analysis of critical regions on chromosome arms 1q, 7q, and 8p in adenocarcinomas of the gastroesophageal junction. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2009;189:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diosdado B, Buffart TE, Watkins R, Carvalho B, Ylstra B, Tijssen M, Bolijn AS, Lewis F, Maude K, Verbeke C, et al. High-resolution array comparative genomic hybridization in sporadic and celiac disease-related small bowel adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1391–1401. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakakura C, Mori T, Sakabe T, Ariyama Y, Shinomiya T, Date K, Hagiwara A, Yamaguchi T, Takahashi T, Nakamura Y, et al. Gains, losses, and amplifications of genomic materials in primary gastric cancers analyzed by comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;24:299–305. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199904)24:4<299::aid-gcc2>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozma L, Kiss I, Hajdú J, Szentkereszty Z, Szakáll S, Ember I. C-myc amplification and cluster analysis in human gastric carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:707–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng DF, Sugihara H, Mukaisho K, Ling ZQ, Hattori T. Genetic lineage of poorly differentiated gastric carcinoma with a tubular component analysed by comparative genomic hybridization. J Pathol. 2004;203:884–895. doi: 10.1002/path.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furge KA, Chen J, Koeman J, Swiatek P, Dykema K, Lucin K, Kahnoski R, Yang XJ, Teh BT. Detection of DNA copy number changes and oncogenic signaling abnormalities from gene expression data reveals MYC activation in high-grade papillary renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3171–3176. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner N, Lambros MB, Horlings HM, Pearson A, Sharpe R, Natrajan R, Geyer FC, van Kouwenhove M, Kreike B, Mackay A, et al. Integrative molecular profiling of triple negative breast cancers identifies amplicon drivers and potential therapeutic targets. Oncogene. 2010;29:2013–2023. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klingbeil P, Natrajan R, Everitt G, Vatcheva R, Marchio C, Palacios J, Buerger H, Reis-Filho JS, Isacke CM. CD44 is overexpressed in basal-like breast cancers but is not a driver of 11p13 amplification. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120:95–109. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukuda Y, Kurihara N, Imoto I, Yasui K, Yoshida M, Yanagihara K, Park JG, Nakamura Y, Inazawa J. CD44 is a potential target of amplification within the 11p13 amplicon detected in gastric cancer cell lines. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;29:315–324. doi: 10.1002/1098-2264(2000)9999:9999<::aid-gcc1047>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Järvinen AK, Autio R, Kilpinen S, Saarela M, Leivo I, Grénman R, Mäkitie AA, Monni O. High-resolution copy number and gene expression microarray analyses of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines of tongue and larynx. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:500–509. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bizari L, Borim AA, Leite KR, Gonçalves Fde T, Cury PM, Tajara EH, Silva AE. Alterations of the CCND1 and HER-2/neu (ERBB2) proteins in esophageal and gastric cancers. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;165:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawey ET, Chanrion M, Cai C, Wu G, Zhang J, Zender L, Zhao A, Busuttil RW, Yee H, Stein L, et al. Identification of a therapeutic strategy targeting amplified FGF19 in liver cancer by Oncogenomic screening. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kashyap MK, Marimuthu A, Kishore CJ, Peri S, Keerthikumar S, Prasad TS, Mahmood R, Rao S, Ranganathan P, Sanjeeviah RC, et al. Genomewide mRNA profiling of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma for identification of cancer biomarkers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:36–46. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.1.7090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibcus JH, Menkema L, Mastik MF, Hermsen MA, de Bock GH, van Velthuysen ML, Takes RP, Kok K, Alvarez Marcos CA, van der Laan BF, et al. Amplicon mapping and expression profiling identify the Fas-associated death domain gene as a new driver in the 11q13.3 amplicon in laryngeal/pharyngeal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6257–6266. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mita H, Toyota M, Aoki F, Akashi H, Maruyama R, Sasaki Y, Suzuki H, Idogawa M, Kashima L, Yanagihara K, et al. A novel method, digital genome scanning detects KRAS gene amplification in gastric cancers: involvement of overexpressed wild-type KRAS in downstream signaling and cancer cell growth. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsuda H, Birrer MJ, Ito YM, Ohashi Y, Lin M, Lee C, Wong WH, Rao PH, Lau CC, Berkowitz RS, et al. Identification of DNA copy number changes in microdissected serous ovarian cancer tissue using a cDNA microarray platform. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;155:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss MM, Kuipers EJ, Postma C, Snijders AM, Pinkel D, Meuwissen SG, Albertson D, Meijer GA. Genomic alterations in primary gastric adenocarcinomas correlate with clinicopathological characteristics and survival. Cell Oncol. 2004;26:307–317. doi: 10.1155/2004/454238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Italiano A, Bianchini L, Keslair F, Bonnafous S, Cardot-Leccia N, Coindre JM, Dumollard JM, Hofman P, Leroux A, Mainguené C, et al. HMGA2 is the partner of MDM2 in well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcomas whereas CDK4 belongs to a distinct inconsistent amplicon. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2233–2241. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valsesia A, Rimoldi D, Martinet D, Ibberson M, Benaglio P, Quadroni M, Waridel P, Gaillard M, Pidoux M, Rapin B, et al. Network-guided analysis of genes with altered somatic copy number and gene expression reveals pathways commonly perturbed in metastatic melanoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myllykangas S, Junnila S, Kokkola A, Autio R, Scheinin I, Kiviluoto T, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Hollmén J, Knuutila S, Puolakkainen P, et al. Integrated gene copy number and expression microarray analysis of gastric cancer highlights potential target genes. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:817–825. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang S, Jeung HC, Jeong HJ, Choi YH, Kim JE, Jung JJ, Rha SY, Yang WI, Chung HC. Identification of genes with correlated patterns of variations in DNA copy number and gene expression level in gastric cancer. Genomics. 2007;89:451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varis A, Wolf M, Monni O, Vakkari ML, Kokkola A, Moskaluk C, Frierson H, Powell SM, Knuutila S, Kallioniemi A, et al. Targets of gene amplification and overexpression at 17q in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2625–2629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorringe KL, Boussioutas A, Bowtell DD. Novel regions of chromosomal amplification at 6p21, 5p13, and 12q14 in gastric cancer identified by array comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;42:247–259. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Junnila S, Kokkola A, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Puolakkainen P, Monni O. Genome-wide gene copy number and expression analysis of primary gastric tumors and gastric cancer cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwei KA, Bashyam MD, Kao J, Ratheesh R, Reddy EC, Kim YH, Montgomery K, Giacomini CP, Choi YL, Chatterjee S, et al. Genomic profiling identifies GATA6 as a candidate oncogene amplified in pancreatobiliary cancer. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu B, Luo M, Lakkur S, Lucito R, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Frequent genomic copy number gain and overexpression of GATA-6 in pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1593–1601. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.10.6565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alvarez H, Opalinska J, Zhou L, Sohal D, Fazzari MJ, Yu Y, Montagna C, Montgomery EA, Canto M, Dunbar KB, et al. Widespread hypomethylation occurs early and synergizes with gene amplification during esophageal carcinogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cui J, Chen Y, Chou WC, Sun L, Chen L, Suo J, Ni Z, Zhang M, Kong X, Hoffman LL, et al. An integrated transcriptomic and computational analysis for biomarker identification in gastric cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1197–1207. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varis A, van Rees B, Weterman M, Ristimäki A, Offerhaus J, Knuutila S. DNA copy number changes in young gastric cancer patients with special reference to chromosome 19. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1914–1919. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leung SY, Ho C, Tu IP, Li R, So S, Chu KM, Yuen ST, Chen X. Comprehensive analysis of 19q12 amplicon in human gastric cancers. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:854–863. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Dekken H, Vissers K, Tilanus HW, Kuo WL, Tanke HJ, Rosenberg C, Ijszenga M, Szuhai K. Genomic array and expression analysis of frequent high-level amplifications in adenocarcinomas of the gastro-esophageal junction. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;166:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nonet GH, Stampfer MR, Chin K, Gray JW, Collins CC, Yaswen P. The ZNF217 gene amplified in breast cancers promotes immortalization of human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1250–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weiss MM, Snijders AM, Kuipers EJ, Ylstra B, Pinkel D, Meuwissen SG, van Diest PJ, Albertson DG, Meijer GA. Determination of amplicon boundaries at 20q13.2 in tissue samples of human gastric adenocarcinomas by high-resolution microarray comparative genomic hybridization. J Pathol. 2003;200:320–326. doi: 10.1002/path.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mao XG, Yan M, Xue XY, Zhang X, Ren HG, Guo G, Wang P, Zhang W, Huo JL. Overexpression of ZNF217 in glioblastoma contributes to the maintenance of glioma stem cells regulated by hypoxia-inducible factors. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1068–1078. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quinlan KG, Verger A, Yaswen P, Crossley M. Amplification of zinc finger gene 217 (ZNF217) and cancer: when good fingers go bad. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1775:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guan XY, Fu SB, Xia JC, Fang Y, Sham JS, Du BD, Zhou H, Lu S, Wang BQ, Lin YZ, et al. Recurrent chromosome changes in 62 primary gastric carcinomas detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;123:27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(00)00306-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Croce CM, Sozzi G, Huebner K. Role of FHIT in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1618–1624. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dillon LW, Burrow AA, Wang YH. DNA instability at chromosomal fragile sites in cancer. Curr Genomics. 2010;11:326–337. doi: 10.2174/138920210791616699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saldivar JC, Shibata H, Huebner K. Pathology and biology associated with the fragile FHIT gene and gene product. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109:858–865. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baffa R, Veronese ML, Santoro R, Mandes B, Palazzo JP, Rugge M, Santoro E, Croce CM, Huebner K. Loss of FHIT expression in gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4708–4714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Available from: http: //genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/

- 57.Yoshida K, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Seki N, Sasaki M, Sugano S. Cloning, expression analysis, and chromosomal localization of BH-protocadherin (PCDH7), a novel member of the cadherin superfamily. Genomics. 1998;49:458–461. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zondervan PE, Wink J, Alers JC, IJzermans JN, Schalm SW, de Man RA, van Dekken H. Molecular cytogenetic evaluation of virus-associated and non-viral hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of 26 carcinomas and 12 concurrent dysplasias. J Pathol. 2000;192:207–215. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH690>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang YT, Heist RS, Chirieac LR, Lin X, Skaug V, Zienolddiny S, Haugen A, Wu MC, Wang Z, Su L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of survival in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2660–2667. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwab M. Oncogene amplification in solid tumors. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:319–325. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1999.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Albertson DG. Gene amplification in cancer. Trends Genet. 2006;22:447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ragnarsson G, Eiriksdottir G, Johannsdottir JT, Jonasson JG, Egilsson V, Ingvarsson S. Loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 1p in different solid human tumours: association with survival. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1468–1474. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Z, Yang X, Li Z, McMahon C, Sizer C, Barenboim-Stapleton L, Bliskovsky V, Mock B, Ried T, London WB, et al. CASZ1, a candidate tumor-suppressor gene, suppresses neuroblastoma tumor growth through reprogramming gene expression. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1174–1183. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pinto-de-Sousa J, David L, Reis CA, Gomes R, Silva L, Pimenta A. Mucins MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC6 expression in the evaluation of differentiation and clinico-biological behaviour of gastric carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2002;440:304–310. doi: 10.1007/s00428-001-0548-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pinto-de-Sousa J, Reis CA, David L, Pimenta A, Cardoso-de-Oliveira M. MUC5B expression in gastric carcinoma: relationship with clinico-pathological parameters and with expression of mucins MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC6. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:224–230. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0968-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen Y, Choong LY, Lin Q, Philp R, Wong CH, Ang BK, Tan YL, Loh MC, Hew CL, Shah N, et al. Differential expression of novel tyrosine kinase substrates during breast cancer development. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:2072–2087. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700395-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lu R, Niida H, Nakanishi M. Human SAD1 kinase is involved in UV-induced DNA damage checkpoint function. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31164–31170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Niu GM, Ji Y, Jin DY, Hou J, Lou WH. [Clinical implication of BRSK2 expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma] Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi. 2010;90:1084–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li L, Shi Y, Wu H, Wan B, Li P, Zhou L, Shi H, Huo K. Hepatocellular carcinoma-associated gene 2 interacts with MAD2L2. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;304:297–304. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9512-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Keyse SM. Dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs) and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kimchi ET, Posner MC, Park JO, Darga TE, Kocherginsky M, Karrison T, Hart J, Smith KD, Mezhir JJ, Weichselbaum RR, et al. Progression of Barrett’s metaplasia to adenocarcinoma is associated with the suppression of the transcriptional programs of epidermal differentiation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3146–3154. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Belaguli NS, Aftab M, Rigi M, Zhang M, Albo D, Berger DH. GATA6 promotes colon cancer cell invasion by regulating urokinase plasminogen activator gene expression. Neoplasia. 2010;12:856–865. doi: 10.1593/neo.10224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Etemadmoghadam D, George J, Cowin PA, Cullinane C, Kansara M, Gorringe KL, Smyth GK, Bowtell DD. Amplicon-dependent CCNE1 expression is critical for clonogenic survival after cisplatin treatment and is correlated with 20q11 gain in ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]