Abstract

Despite advances in controlled drug delivery, reliable methods for activatable, high-resolution control of drug release are needed. We hypothesized that the photothermal effect mediated by a near-infrared (NIR) laser and hollow gold nanospheres (HAuNS) could modulate the release of anticancer agents. We tested this hypothesis by developing biodegradable and biocompatible microspheres (1~15 µm) containing the antitumor drug paclitaxel (PTX) and HAuNS (~35 nm in diameter) displaying surface plasmon absorbance in the near-infrared (NIR) region. HAuNS-containing microspheres exhibited an NIR light-induced thermal effect similar to that of plain HAuNS. Rapid, repetitive PTX release from the PTX/HAuNS-containing microspheres was observed when microspheres were irradiated with NIR light (808 nm), whereas PTX release became insignificant when NIR light was switched off. The release of PTX from the microspheres could be readily controlled by NIR laser output power, duration of laser irradiation, treatment frequency, and the concentration of HAuNS embedded inside the microspheres. In vitro, cancer cells incubated with PTX/HAuNS-loaded microspheres and irradiated with NIR light displayed significantly greater cytotoxic effects than cells incubated with the microspheres alone or cells irradiated with NIR light alone, owing to NIR light-triggered drug release. Treatment of human U87 gliomas and MDA-MB-231 mammary tumor xenografts in nude mice with intratumoral injection of PTX/HAuNS-loaded microspheres followed by NIR irradiation resulted in significant tumor growth delay compared to tumors treated with HAuNS-loaded microspheres (no PTX) and NIR irradiation or with PTX/HAuNS-loaded microspheres alone. Our data support the feasibility of a therapeutic approach in which NIR light is used for simultaneous modulation of drug release and induction of photothermal cell killing.

Keywords: Near-infrared light, Photothermal effect, Hollow gold nanospheres, Microspheres, Paclitaxel, Triggered drug release

Introduction

Controlled drug delivery occurs when a polymer, whether natural or synthetic, is combined with a drug or other active agent in such a way that the active agent is released from the material in a predetermined manner. The release of the active agent may be constant over a long period, it may be cyclic, or it may be triggered by the environment or other external events. The main purpose behind controlling drug delivery is to achieve more effective therapies while eliminating the potential for both under- and overdosing. A major challenge for drug delivery is to control drug release both spatially and temporally. Drug delivery triggered by internal or external stimuli, such as pH,[1, 2] enzymes,[3, 4] magnetism,[5, 6] ultrasound,[7–10] and heat,[11] has recently attracted much attention because it represents a strategy to increase the drug concentration at the target location, decrease systemic toxicity, and allow greater temporal control over drug release compared to traditional drug delivery systems.

Light-triggered drug release is an attractive approach for the spatiotemporal control of drug delivery. Delivery systems responsive to light on the basis of photochemical mechanisms have been evaluated for such a purpose. [12–14] However, ultraviolet/visible light was used to activate the release of drugs from these systems, which limits their use to in vitro situations because ultraviolet/visible light cannot penetrate skin. An alternative approach is to use the photothermal phenomenon mediated by gold nanoparticles. Gold nanostructures such as gold nanoshells,[15, 16] hollow gold nanospheres (HAuNS),[17, 18] and gold nanorods [19, 20] have been used for photothermal ablation of cancer cells. These noble metal nanoparticles exhibit a strong optical extinction at near-infrared (NIR) wavelengths (700–850 nm) owing to the localized surface plasmon resonance of their free electrons upon excitation by an electromagnetic field. Absorption of NIR light results in resonance and the transfer of thermal energies to the surrounding medium or tissue. NIR light (700–850 nm) can readily penetrate skin and go deep into the tissue because tissue absorption of light in the NIR region is minimal.[21] Bikram et al.[22] embedded SiO2-Au nanoshells within temperature-sensitive hydrogels and demonstrated modulated drug delivery profiles. However, this system has not yet been translated to injectable colloidal delivery vehicles suitable for in vivo applications. Bedard et al.[23] fabricated multi-layered polyelectrolyte microshells containing aggregates of colloidal gold from which they showed NIR-triggered release of dextran. Wu et al.[24] used a femtosecond pulsed laser to trigger release of a dye molecule from liposomes containing HAuNS. However, the release of therapeutically significant anticancer drugs from these systems was not investigated. In vivo evaluation of these delivery systems, which must be tested before progress toward clinical use can be made, has not been performed.

We hypothesized that the photothermal effect mediated by a near-infrared (NIR) laser and hollow gold nanospheres (HAuNS) could modulate the release of anticancer agents. To test our hypothesis, we fabricated polymeric microspheres based on biodegradable, biocompatible poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) copolymers containing paclitaxel (PTX) as an anticancer drug and HAuNS as the photothermal coupling agent and evaluated the drug release properties, in vitro cytotoxicity, and in vivo antitumor activity of these microspheres mediated by NIR light.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of HAuNS and PTX–loaded PLGA microspheres

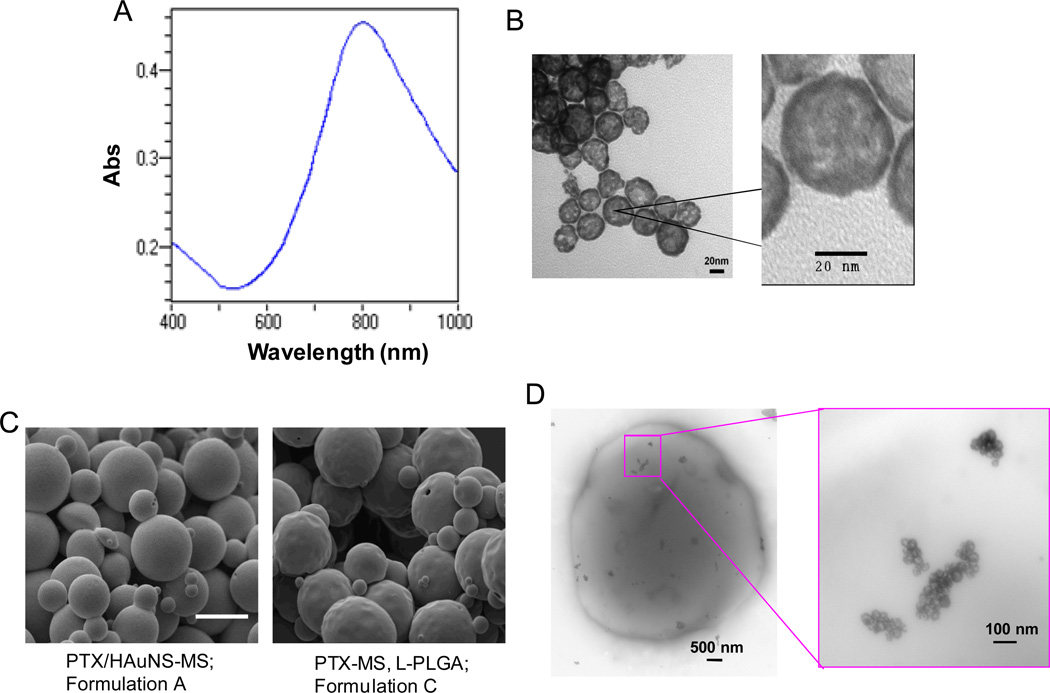

HAuNS were prepared by the cobalt nanoparticle-mediated reduction of chloroauric acid. The absorption spectrum of HAuNS showed the plasma resonance peak tuned to the NIR region (λmax=808 nm) (Fig. 1A). TEM images revealed the near-spherical morphology of HAuNS (Fig. 1B). The average diameter of HAuNS and the thickness of the Au shell were 36 nm and 4 nm, respectively, as measured from the TEM images. This is consistent with the average diameter determined by dynamic light scattering, which yielded a mean diameter of 34 nm. No apparent aggregation or change in the UV-visible spectrum was observed when HAuNS were suspended in pure water at room temperature over a period of 1 month. Table 1 summarizes the parameters used in the preparation of the various microspheres. PTX was readily loaded into PLGA microspheres, with encapsulation efficiency (EE) close to 100% due to its hydrophobic nature. More than 90% of HAuNS were encapsulated into the microspheres by the double emulsion method (Table 1). Figures 1C and 1D show SEM and TEM photographs of PTX/HAuNS microspheres. The size of the microspheres was between 1–10 µm. All formulations of microspheres had a dense texture and nonporous surface. The introduction of HAuNS into PTX-loaded microspheres formed from PLGA resulted in a smoother surface than those without HAuNS (compare formulations A and C in Fig. 1C). This phenomenon is analogous to the role reinforcing steel bars play in concrete, as HAuNS nanoparticles made the PLGA microspheres denser and harder.[25] TEM photographs of PTX/HAuNS-MS revealed the dispersion of clusters of HAuNS in the PLGA matrix (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

(A) Absorption spectrum of HAuNS showing the plasmon resonance peak tuned to the NIR region (λmax=808 nm). (B) TEM images of HAuNS revealing the morphology of the hollow nanospheres. Bar, 20 nm. (C) SEM images of PTX-loaded, HAuNS-embedded microspheres (PTX/HAuNS-MS) and microspheres containing only PTX (PTX-MS). The presence of HAuNS resulted in microspheres with a smoother surface. Bar, 10 µm. (D) TEM photographs of a PTX/HAuNS-MS showing clusters of HAuNS dispersed within the polymeric matrix.

Table 1.

Preparation parameters for PLGA microspheres*

| Formulation | Microspheres | HAuNS loading (particles/mg microspheres) |

EE of PTX loading (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | PTX/HAuNS-MS | 9.4×109 | 102 |

| B | PTX/HAuNS-MS | 4.7×1010 | 97.8 |

| C | PTX-MS | -- | 104 |

| D | HAuNS-MS | 9.4×109 | -- |

The concentration of PLGA in the organic phase was 30% (w/v). The concentration of polyvinyl alcohol in the outer aqueous phase was 2% (w/v). The theoretical PTX loading was 5% (w/w) for all formulations. HAuNS, hollow gold nanospheres; EE, encapsulation efficiency; PTX, paclitaxel; MS, microspheres.

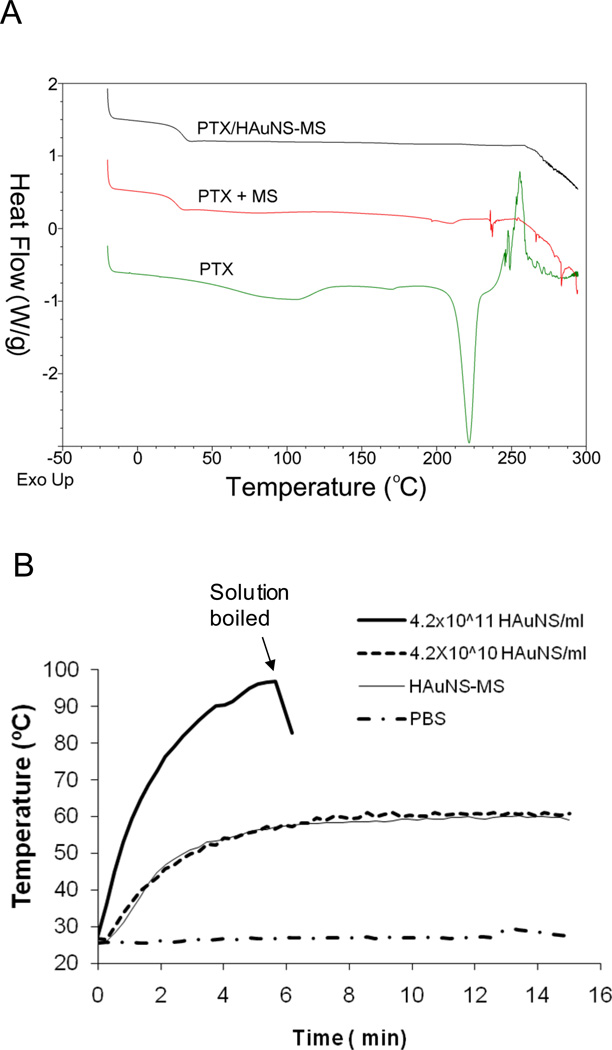

DSC thermograms for both PTX alone and the mixture of PTX and plain PLGA microspheres exhibited a single melting endothermal peak at around 210°C, just before degradation. In addition, the PTX thermogram showed an endothermic dehydration peak at ~85°C (Fig. 2A). These data are consistent with data in the literature for hydrated crystalline PTX.[26] Both endothermic dehydration and melting peaks were missing in PTX/HAuNS-MS, suggesting that PTX was molecularly dispersed in the PLGA polymeric matrix.

Fig. 2.

(A) DSC thermograms of PTX/HAuNS-MS, pure PTX, and a physical mixture of PLGA and PTX (5% PTX, w/w). An endothermic peak at around 210°C, representing the melting point of PTX, was present in the physical mixture of PTX and MS, but not in PTX/HAuNS-MS, suggesting that PTX was dissolved in PLGA polymer at the molecular level. (B) Comparison of the temperature changes in aqueous solutions containing HAuNS and HAuNS-MS after exposure to NIR light at an output power of 4.5 W/cm2. HAuNS-loaded PLGA microspheres elevated the temperature of the water to the same extent as did HAuNS alone at a concentration of 4.2×1010 nanoparticles/mL.

Continuous exposure of aqueous suspensions of HAuNS and HAuNS-MS to NIR light resulted in the rapid elevation of their temperatures. At a laser output power of 1.5 W (~4.5 W/cm2) and an equivalent HAuNS concentration of 4.2×1010 particles/mL, the temperatures of both suspensions (HAuNS and HAuNS-MS) were elevated 23.3°C after 5 min of exposure. At a higher HAuNS concentration of 4.2×1011 particles/mL, the aqueous solution reached the boiling point in less than 5 min. In comparison, no significant temperature change was observed when PBS was exposed to the laser light (Fig. 2B). Plain PLGA-MS in PBS at a concentration of 50 mg/mL also did not cause temperature change upon NIR light irradiation (data not shown). These results indicate that HAuNS-loaded PLGA-MS was able to elevate the temperature of water to the same extent as HAuNS alone at a concentration of 4.2×1010 nanoparticles/mL and that encapsulation of HAuNS into PLGA-MS did not adversely affect the absorption of NIR light and the photothermal conversion capacity of HAuNS.

NIR light triggered release of PTX from PTX/HAuNS-MS

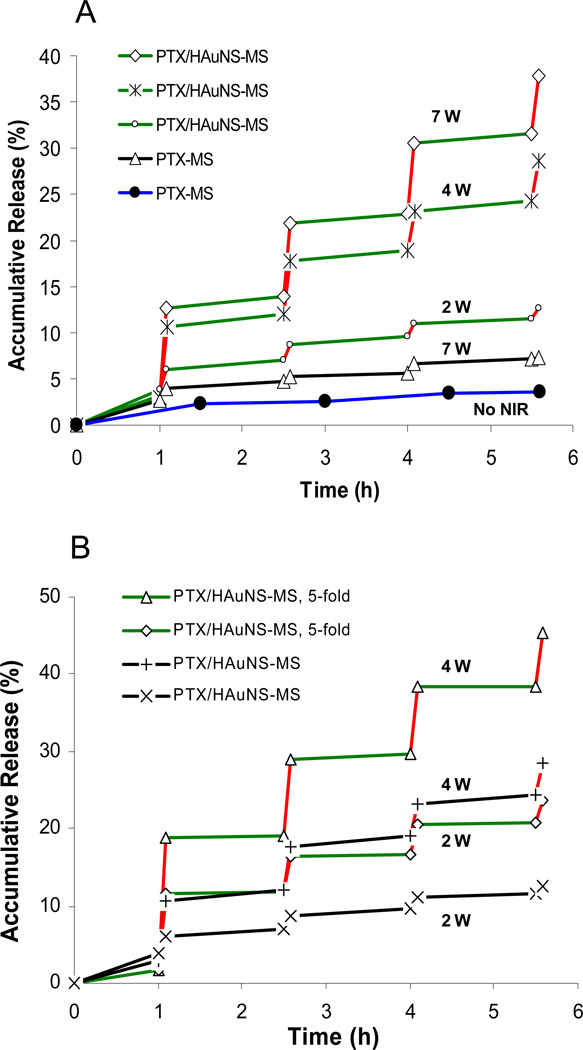

Figure 3 shows the characteristics of PTX release from PTX/HAuNS-MS (formulations A and B) and from PTX-MS (formulation C) prepared from PLGA. The microsphere suspensions (10 mg/mL) were irradiated repeatedly using an NIR laser over a period of 5 min, followed by 1.5-h intervals with the laser turned off. The red lines in Fig. 3 indicate the time periods during which the microspheres were irradiated using the NIR laser. A rapid increase in PTX release from PTX/HAuNS-MS was observed upon NIR irradiation, and the PTX release slowed significantly when NIR irradiation was switched off. After the first NIR exposure for 5 min at 7-W output power, the cumulative release, defined as the percentage of released PTX to total entrapped PTX, increased from 3.2% to 12.6%. However, only about 1% of PTX (from 12.6% to 13.9%) was released during the subsequent 1.5 h of incubation without NIR light exposure. During the second 5-min NIR exposure, the PTX release rate was elevated rapidly, with an 8% (from 13.9% to 21.9%) increase in cumulative release. There were 7.4% and 6.2% increases in cumulative PTX release for the third and fourth NIR exposure cycles, respectively. In contrast, less than 1% of PTX was released during the 1.5-h periods without NIR light exposure in each of the following three incubation periods. The accumulated release of PTX over the whole course of the experiment approached 40% when PTX/HAuNS-MS were exposed to the NIR laser 4 times for 5 min each. In comparison, PTX-MS (without HAuNS) subjected to the same treatment protocol displayed a cumulative release of <7% over the entire experimental period. PTX-MS without laser irradiation had an accumulated release of only 3.6% (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

NIR light triggered release of PTX from PTX/HAuNS-MS. Red lines represent the 5-min period during which the microspheres were irradiated with NIR laser. (A) PTX release profiles of PTX/HAuNS-MS (formulation B) at an NIR output power of 7 W (◇), 4 W (*), and 2 W (○); PTX release profiles from PTX-MS (formulation C) at an NIR output power of 7 W (△) and without NIR exposure (●). (B) PTX release from PTX/HAuNS-MS containing 4.7×1010 HAuNS/mg PLGA (formulation B) at an NIR output power of 4 W (△) and 2 W (◇); PTX release from PTX/HAuNS-MS containing 9.4×109 HAuNS/mg PLGA (formulation A) at an NIR output power of 4 W (+) and 2 W (×), respectively. The spot size was 10 mm in diameter.

The drug release increased with increasing NIR laser power. During the first NIR light exposure, 9.4%, 7.5%, and 2.1% of PTX was released from the PTX/HAuNS-MS at output powers of 7 W, 4 W, and 2 W, respectively (Fig. 3A). The amount of PTX released also increased with increasing HAuNS loading in the microspheres. After NIR laser exposure, more PTX was released from the PTX/HAuNS-MS containing a higher concentration of HAuNS than from those containing a lower concentration of HAuNS. For example, 17.2% of PTX was released from PTX/HAuNS-MS (formulation B) during the first NIR light irradiation at an output power of 4 W. In comparison, 9.4% of PTX was released from PTX/HAuNS-MS containing 5-fold less HAuNS (formulation A) (Fig. 3B).

In vitro cytotoxicity

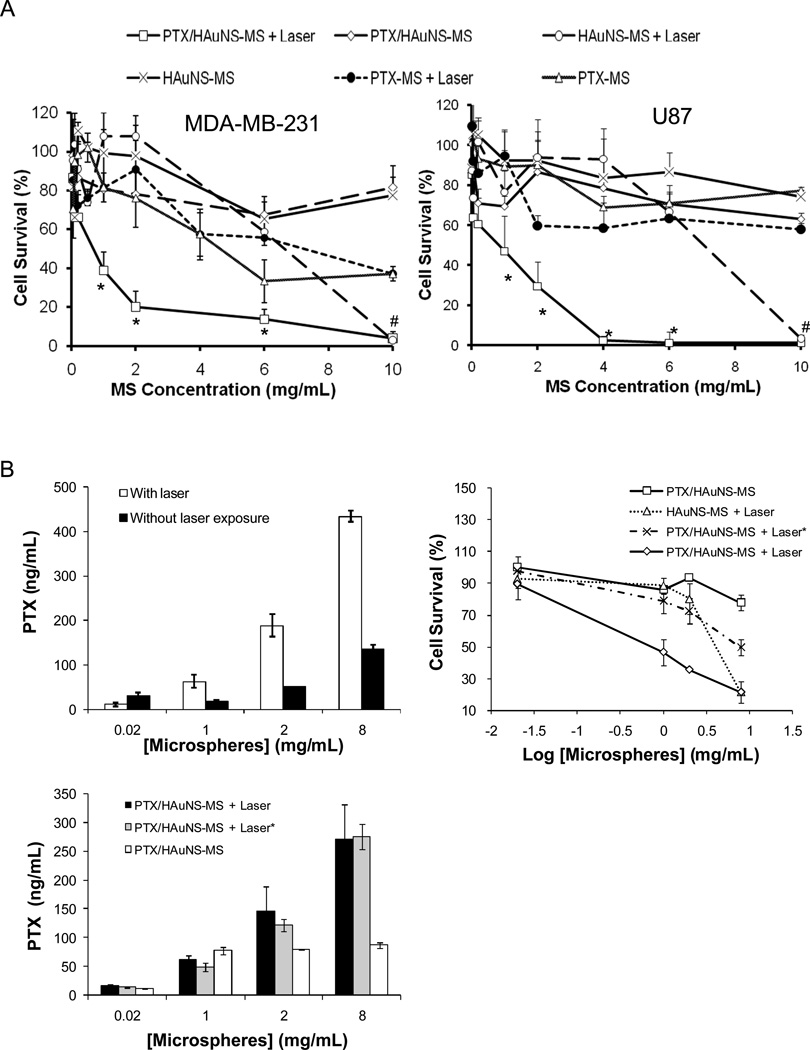

The cytotoxic effects of PTX/HAuNS-MS, with or without NIR irradiation, in MDA-MB-231 and U87 cells are shown in Figure 4. There was a significant difference between the cell-killing effect of PTX/HAuNS-MS combined with NIR irradiation and that of PTX/HAuNS-MS alone. For example, when MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with PTX/HAuNS-MS at concentrations of 1 mg/mL and 10 mg/mL, 80.6% and 81.6% of the cells, respectively, were viable after 72 h of incubation. However, when cells were incubated with PTX/HAuNS-MS at the same microsphere concentrations and irradiated with NIR, only 38.8% and 3.9% of the cells, respectively, survived (Fig. 4A). Moreover, when cells were incubated with HAuNS-MS (no PTX) at microsphere concentrations of 0.05–6.0 mg/mL, more than 60% of the cells were viable, regardless of whether the cells were irradiated with the NIR laser. Significant cell killing was observed with HAuNS-MS only at the highest microsphere concentration tested (10 mg/mL). Similar findings were observed with U87 cells (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

(A) Cytotoxicity in the presence and absence of NIR irradiation. MDA-MB-231 or U87 glioma cells were incubated with various microsphere formulations for 72 h. For NIR treatment, cells were irradiated with an NIR laser 4 times at an output power of 2 W for 3 min each. Cells were incubated with PTX/HAuNS-MS, PTX-MS, and HAuNS-MS. Data are presented as mean plus/minus standard deviation of triplicate measurements. *P<0.01 compared to all the other treatment groups. #p<0.01 compared to all the other treatment groups except cells treated with HAuNS-MS. (B) Effect of free PTX released into the medium on cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 cells. PTX concentrations in cell culture media in the presence and absence of laser irradiation (top left), and in culture media 72 h after incubation with MDA-MB-231 cells (bottom) were quantified by HPLC (n = 4). Cell survival was determined using MTT assay (n = 3) after 72h incubation (top right). Treatment with (PTX/HAuNS-MS + laser*) indicates PTX/HAuNS-MS in cell culture medium was first irradiated by NIR laser, followed by transferring the medium including microspheres into cell culture wells with MDA-MB-231 cells. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

To further study whether there is synergistic interaction between photothermal effect and PTX’s cytotoxic effect, we conducted cytotoxicity study against MDA-MD-231 cells using culture medium pre-incubated with PTX/HAuNS-MS and treated with NIR laser. As shown in Figure 4B, irradiation of PTX/HAuNS-MS with NIR laser at 2W for 5 min caused significant increase of the concentration of free PTX in culture medium when the concentration of microspheres was greater than 1.0 mg/mL (Fig. 4B, top left). Treatment with PTX/HAuNS-MS alone at 0.02, 1.0, 2.0, and 8.0 mg/mL caused 0.03±2.6%, 14.3±1.3%, 6.6±1.5%, 22.2±4.8% cell killing, respectively. In comparison, when PTX/HAuNS-MS in culture medium was pre-irradiated with NIR laser, the percent of cell killed increased to 2.3±9.1%, 21.2±7.8%, 27.4±8.1%, 50.2±4.7%, respectively. The significant enhancement in cell killing did not involve photothermal killing effect, because PTX/HAuNS-MS was irradiated in the absence of cells. However, when PTX/HAuNS-MS were irradiated with NIR laser in the presence of MDA-MB-231 cells, the percent of cells killed was 10.6±9.4%, 53.2±8.2%, 64.3±0.9%, 78.4±6.9% at PTX/HAuNS-MS concentrations of 0.02, 1.0, 2.0, and 8.0 mg/mL, respectively. When cells were treated with HAuNS-MS (without PTX) and NIR laser under the same conditions, the percentages of cell killed were 7.4±5.3%, 11.4±4.8%, 19.8±9.7%, and 78.4±1.0% at HAuNS-MS concentrations of 0.02, 1.0, 2.0, and 8.0 mg/mL, respectively (Fig. 4B, top right). There was no significant difference in the concentration of free PTX in culture media after 3 days of incubation with MDA-MB-231 cells between those pre-treated with PTX/HAuNS-MS and NIR laser, and those irradiated together with PTX/HAuNS-MS and the cells (Fig. 4B, bottom).

In vivo antitumor activity

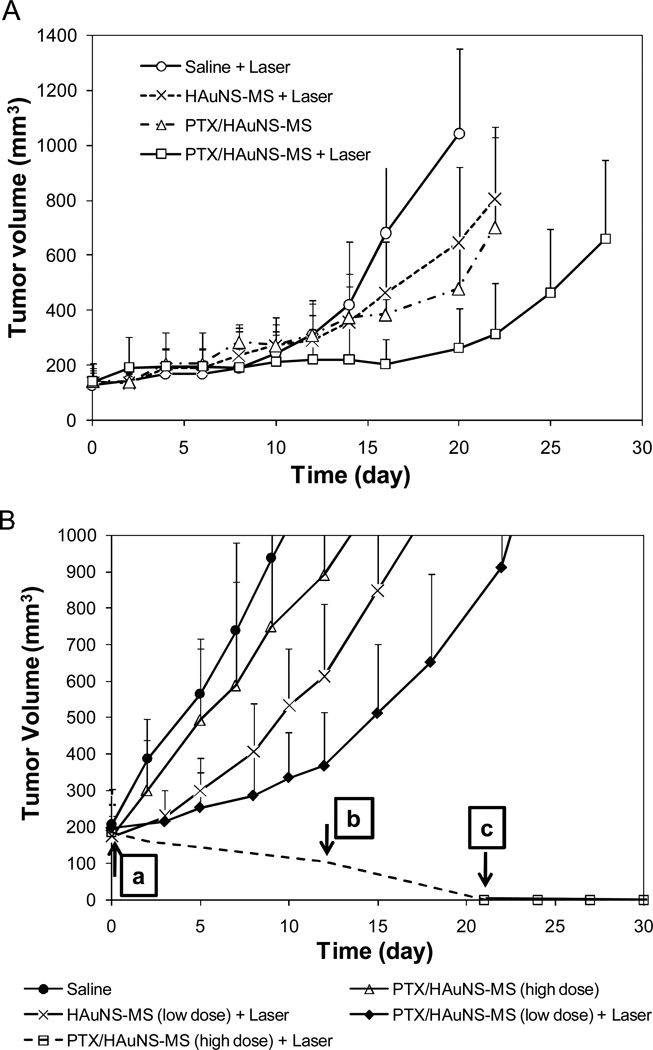

Figure 5A shows the U87 tumor growth curves after intratumoral injection of various microspheres. The tumor growth delays, expressed as the number of days for tumors to grow from 100 mm3 to 500 mm3, were 27.5±3.8 (n=4), 21.5±1.7 (n=4), 19.0±3.5 (n=4), and 14.8±1.8 (n=5) days for mice treated with PTX/HAuNS-MS plus NIR light irradiation, PTX/HAuNS-MS, HAuNS-MS plus NIR light irradiation, and saline plus NIR light irradiation, respectively. Treatment with both PTX/HAuNS-MS and NIR laser caused a significant growth delay compared to treatments with HAuNS-MS (without PTX) plus laser (p = 0.045), PTX/HAuNS-MS without laser (p = 0.016), and saline plus laser (p = 0.003).

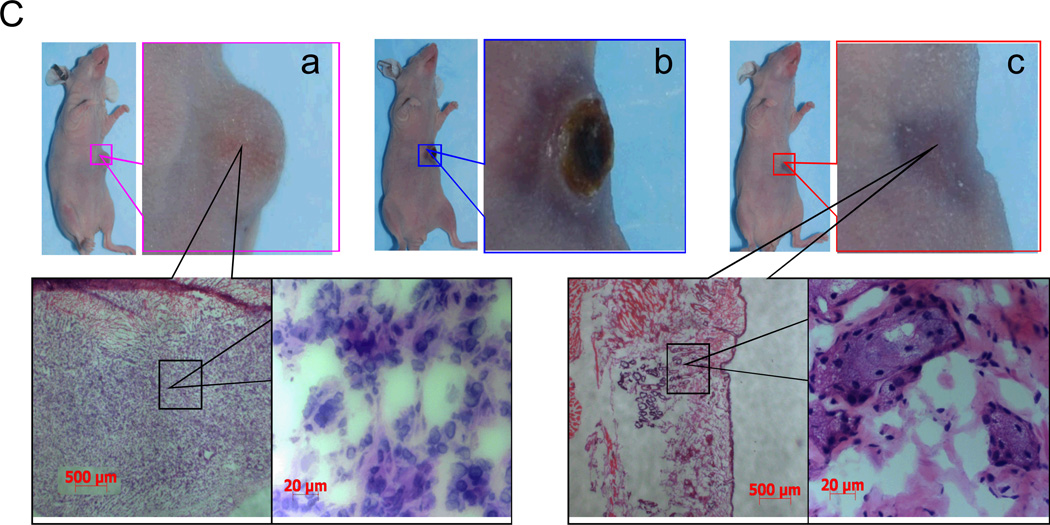

Fig. 5.

(A) Antitumor effects of various treatments on U87 human gliomas grown in nude mice. The microspheres were injected intratumorally in a single dose when tumor volume reached 100 mm3. Data are presented as mean ± SD tumor volumes (n = 4–5). (B) Antitumor effects of various treatments on MDA-MB-231 human breast carcinoma inoculated into the mammary fat pads of nude mice. The microspheres were injected intratumorally in a single dose when tumor volume measured 200 mm3. Data are presented as mean ± SD tumor volumes (n = 5). Arrows indicate times at which tumors were removed for histologic analysis; (a–c) correspond to photographs a–c shown in (C). (C) Microphotographs of tumor tissues removed at different times from mice treated with PTX/HAuNS-MS at a high dose of 6.0 mg equivalent PTX/kg (2.82×1010 HAuNS particles/mouse) plus laser irradiation. Tumors were burned initially, but gradually healed and became scars. No microscopic tumor cells were found in the scar tissues.

The average MDA-MB-231 tumor growth curves after treatment with the microspheres at various doses are presented in Figure 5B. The tumor growth delays were 25.0±3.5, 19.8±4.0, 15.8±6.1, and 10.2±2.8 days for mice treated with PTX/HAuNS-MS plus laser (low dose), HAuNS-MS plus NIR laser (low dose), PTX/HAuNS-MS (high dose), and saline, respectively. Similar to the findings with U87 tumors, treatment with combined PTX/HAuNS-MS and laser at a lower dose of microspheres (1.0 mg equivalent PTX/kg, 4.7×109 HAuNS particles/mouse) caused significant growth delay compared to treatments with saline (p < 0.0001) or HAuNS-MS plus NIR laser (p = 0.037). At a higher dose of PTX/HAuNS-MS (6.0 mg equivalent PTX/kg, 2.82×1010 HAuNS particles/mouse), NIR laser irradiation caused burning of tissue and extensive necrosis in the first 3 weeks after the initiation of treatment. The burned tissues gradually healed, however, and by 20 days after treatment, all tumors had disappeared completely, with only scar tissue remaining. Histologic examination confirmed the absence of tumor cells in the remaining scar tissue (Fig. 5C). In contrast, mice treated with the same dose of PTX/HAuNS-MS, but without NIR laser irradiation, showed minimal antitumor activity; the tumor growth delay, measured in days for tumors to grow from 200 mm3 to 1000 mm3, did not differ significantly from that in mice treated with saline control (p = 0.056) (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

Despite advances over the past few decades, spatial and temporal control of drug release characteristics remains a challenge. Among the various external stimuli evaluated, the use of NIR light as a source of drug release control is a promising approach. NIR light is already being used in the clinic for molecular imaging and for cancer ablation therapy. In this study, we found that the photothermal effect mediated by an NIR laser and HAuNS could modulate the release of anticancer agents.

We selected HAuNS because these nanoparticles possess excellent colloidal stability, are small in size (35–40 nm in diameter), and display tunable and strong absorption bands in the NIR region. HAuNS coated with a monoclonal antibody or peptides have recently been targeted to solid tumors after systemic administration for enhanced photothermal ablation therapy.[17, 18] By incorporating HAuNS into PLGA microspheres, we anticipated that the small size and strong surface plasma absorption of HAuNS would result in a drug delivery system that is highly responsive to NIR laser irradiation. We chose to incorporate PTX into the HAuNS-containing PLGA microspheres to demonstrate NIR light–triggered release of a highly hydrophobic drug. PTX is a widely used anticancer agent with demonstrated antitumor efficacy against breast, ovarian, lung, and head and neck cancers.[27–30]

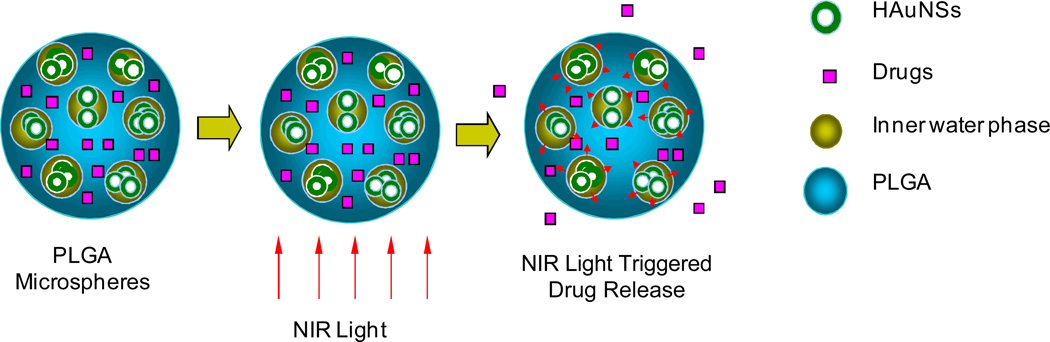

Figure 6 depicts the proposed mechanism of NIR light–triggered release of drugs from PLGA microspheres, as well as the hypothetical structure of microspheres containing HAuNS and PTX. Because the microspheres were prepared by a W1/O/W2 double-emulsion solvent evaporation method, it was anticipated that PTX dissolved in the organic phase together with the PLGA polymer would be uniformly distributed within the polymer, whereas HAuNS nanoparticles dissolved in the original aqueous phase would be dispersed in the water phase inside the microspheres (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Hypothetical structure of PTX/HAuNS-MS and proposed mechanism of NIR-triggered drug release from the microspheres. PTX is dispersed uniformly in the matrix of PLGA polymer, whereas HAuNS are primarily dispersed in the water phase within the microspheres.

The structural features of PTX/HAuNS microspheres depicted in Figure 6 are supported by TEM study, which showed the formation of HAuNS clusters within the microspheres, possibly as a result of the inner water droplets containing a high local concentration of HAuNS (Fig. 1D), and by DSC analysis, which revealed that the liposoluble PTX was dispersed in PLGA polymer at the molecular level (Fig. 2A). HAuNS recovered from PTX/HAuNS microspheres had the same absorption property as HAuNS shown in Figure 1A (data not shown). Thus the encapsulation process did not affect the optical property of HAuNS. In vitro studies confirmed that HAuNS-containing microspheres were capable of raising the temperature of the aqueous solution as much as did plain HAuNS at the same concentration (Fig. 2B). Importantly, the heat generated was sufficient for triggering PTX release. The release of PTX from microspheres containing HAuNS could be readily modulated by controlling the NIR laser output power, the duration and frequency of laser irradiation, and the HAuNS payload in the microspheres (Fig. 3). These results indicate that PTX release from PTX/HAuNS-MS resulted directly from the photothermal effect mediated by HAuNS embedded in the microspheres. The polymer chains became increasingly more flexible due to a rapid elevation of the local temperature of the microspheres upon NIR irradiation, resulting in increased release of the PTX drug molecules from the PLGA matrix (Fig. 6).

In vitro cytotoxicity studies confirmed that the antitumor effect of PTX/HAuNS-MS was enhanced when cells were irradiated with NIR laser. Significant cell killing was observed with PTX/HAuNS-MS plus NIR irradiation but not with PTX/HAuNS-MS alone or PTX-MS alone, indicating that the amount of PTX released from the PTX-containing microspheres in the absence of NIR light was insufficient to kill tumor cells. In addition, PTX/HAuNS-MS plus NIR irradiation, but not HAuNS-MS plus NIR laser, caused significant cytotoxicity at microsphere concentrations of up to 6 mg/mL (0.3 mg equivalent PTX/mL), indicating that PTX released from PTX/HAuNS-MS was primarily responsible for the cell killing achieved with PTX/HAuNS-MS plus NIR at these concentrations. At higher concentrations of HAuNS-MS (≥10 mg/mL), the photothermal effect mediated by HAuNS was sufficient to ablate the tumor cells (Fig. 4A). Further studies suggest that at microspheres concentrations of 1.0 and 2.0 mg/mL, treatments with PTX/HAuNS-MS plus NIR laser caused greater cell killing effect than combined cell killing effect achieved with HAuNS-MS plus laser (pure photothermal killing effect) and with culture media containing PTX/HAuNS-MS pre-exposed to NIR laser (pure cytotoxic effect of the drug) (Fig. 4B). Because there was no difference in drug concentration after 72 h cell incubation between the culture medium that was irradiated with PTX/HAuNS-MS in the absence of cells and the culture medium that was irradiated with PTX/HAuNS-MS in the presence of cells, the observed enhanced cell killing with PTX/HAuNS-MS plus laser could be attributed to a synergistic interaction between PTX and photothermal effect mediated through PTX/HAuNS-MS.

Enhanced antitumor activity with PTX/HAuNS-MS followed by NIR irradiation was also demonstrated in vivo in experimental tumor models. Significantly higher antitumor activity against subcutaneously inoculated U87 tumors was achieved with combined PTX/HAuNS-MS and NIR laser than with PTX/HAuNS-MS alone (low PTX release rate and no photothermal effect) or with HAuNS-MS plus NIR laser (photothermal effect but without PTX) (Fig. 5A). Similar findings were observed in an orthotopically inoculated mammary MDA-MB-231 tumor model (Fig. 5B). Notably, at a high dose of PTX/HAuNS-MS (6.0 mg equivalent PTX/kg), cure of tumors was achieved with PTX/HAuNS-MS combined with NIR laser, whereas PTX/HAuNS-MS alone at the same dose had little antitumor effect. The enhanced antitumor activity in tumors treated with combined PTX/HAuNS-MS and NIR is most likely a result of both the cytotoxic effect of PTX release from the microspheres induced by NIR light and the photothermal effect mediated by HAuNS embedded in the microspheres.

Novel polymeric drug delivery systems, including injectable microspheres, have been developed for local delivery of PTX in order to meet the challenges encountered in the clinical use of PTX, i.e., hypersensitivity reactions and cumulative toxicity.[31] Owing to the strong hydrophobic interaction between PTX and hydrophobic PLGA polymer, PTX release from this commonly used biodegradable polyester has proven to be extremely slow. To enhance the release of PTX from PLGA microspheres, PLGA was blended with low-molecular-weight amphipathic diblock copolymers. This resulted in an up to 20-fold increase in the burst effect.[31] Hence, the release of PTX from PLGA microspheres is uncontrollable and unpredictable, and only a small portion of the drug is eventually released, limiting the therapeutic efficacy of such methods. In this study, we demonstrated not only that NIR light could modulate release of PTX from PLGA microspheres in a controlled fashion but also that the approach significantly enhanced the antitumor efficacy of PTX-PLGA microspheres in vivo. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the feasibility of enhancing the antitumor effect with light-modulated drug release in vivo. Our data also suggest a potential therapeutic advantage to combining photothermal ablation therapy with NIR light-modulated drug release.

Sanchez-Iglesias et al. [32] recently describes a novel colloidal composites containing gold nanoparticle cores covered by a thin layer of metallic nickel and a poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (pNIPAM) shell. The authors showed that the pNIPAM shell could be swollen or collapsed as a function of temperature, thus allowing capture and release of various types of molecules. By incorporating hollow gold nanospheres into biodegradable PLGA microspheres, photothermal effect could be modulated with NIR light, which is the optimal wavelength that allows penetration of light deep into soft tissues (~5 cm).

The size of the microspheres is depending upon how these microspheres are applied. If the microspheres are intended for intracellular delivery of anticancer agents (i.e. paclitaxel), PTX/HAuNS-embedded particles of smaller size (<1 µm) may result in more efficient cellular uptake. If the intended application is for intratumoral delivery, release of the anticancer drugs in the interstitial space with microspheres of larger sizes (<1 µm) may be sufficient. Future studies on the cellular uptake and antitumor efficacy of PTX/HAuNS-embedded particles of different sizes are needed in order to better define the role of particle size in different applications. The detailed mechanism of PTX release, particularly the effect of HAuNS-mediated photothermal response on the mobility of polymer chains and permeability to hydrophobic drugs, also needed to be investigated.

Conclusion

This work demonstrates the feasibility of modulated drug release using NIR light as the external stimuli. Rapid and repetitive drug release could be readily achieved upon NIR irradiation. Owing to the ability of NIR to penetrate deep tissues, modulation of drug release with NIR light may find applications in the treatment of cancer and other diseases. In addition, intratumoral administration of the microspheres demonstrated in the current study for anticancer therapy shows that the microspheres containing HAuNS and anticancer agents may also be used in chemo-embolization applications where controllable and repetitive release of anticancer drugs in response to an NIR laser beam is needed.

Experimental Section

Reagents

PLGA (lactide:glycolide = 50:50, viscosity = 0.20 dl/g) was purchased from DURECT Corp. (Cupertino, CA). Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA; MW ~25000, 88 mol% hydrolyzed) was purchased from Polysciences, Inc. (Warrington, PA). PTX was provided by Yunnan Hande Bio-Tech Co., Ltd. (Houston, TX). Trisodium citrate dehydrate (>99%), cobalt chloride hexahydrate (99.99%), sodium borohydride (99%), and chloroauric acid trihydrate (ACS reagent grade) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) and were used as received. 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and Tween 80 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Methylene chloride was obtained from Baxter Healthcare Corp. (Deerfield, IL).

Cell lines

U87 (human glioma) and MDA-MB-231 (human breast carcinoma) cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/nutrient mixture F-12 Ham and 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY).

Synthesis and characterization of HAuNS

HAuNS were synthesized according to previously reported procedures.[17, 18] Briefly, cobalt nanoparticles were first synthesized by reducing cobalt chloride (1 mL, 0.4 mol/L) with sodium borohydride (4.5 mL, 1 mol/L) in deionized water containing 2.8 mL of 0.1 mol/L sodium citrate. HAuNS were obtained by adding chloroauric acid into the solution containing cobalt nanoparticles. The size of the HAuNS was determined using dynamic light scattering on a Brookhaven particle size analyzer (Holtsville, NY). Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy was recorded on a Beckman Coulter spectrometer (Fullerton, CA). The morphology of HAuNS was examined with a JEM 1010 transmission electron microscope (TEM) (Peabody, MA). The concentration of the nanoparticles was estimated based on absorbance at 808 nm and an extinction coefficient of ε = 8.3×109 L/mol/cm (1.37×10−11 mL/particle/cm).

Preparation and characterization of PLGA microspheres

A modified water-in-oil-in-water (W1/O/W2) double-emulsion solvent evaporation method was employed to prepare PLGA microspheres containing PTX and HAuNS (PTX/HAuNS-MS). The first emulsion was formed by mixing an aqueous solution (0.08 mL) containing HAuNS with dichloromethane (0.8 mL) containing PLGA (240 mg) and PTX (12.6 mg), which was then injected into an aqueous solution of polyvinyl alcohol (2% PVA, 8.0 mL) serving as the external aqueous phase. W1/O/W2 emulsion was achieved using a POLYTRON PT-MR 3000 benchtop homogenizer from Kinematica AG (Lucerne, Switzerland) at 15,000 rpm. The microspheres were formed after the organic solvent was completely evaporated, washed three times with water, and freeze-dried. Microspheres containing only PTX (PTX-MS) and microspheres containing only HAuNS (HAuNS-MS) were also prepared using the same procedures.

The size and morphology of the microspheres were examined with a JSM-5910 scanning electron microscope (JEOL, USA, Inc., Peabody, MA). Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on a Q2000 system from TA Instruments (New Castle, DE). Samples of ~5 mg were first held isothermal at −20°C for 5 minutes and then heated to 300°C at a rate of 20°C/min. All DSC tests used aluminum pans and 50 mL/min of N2 purge. For measuring the photothermal effect of the HAuNS-containing microspheres, 808-nm NIR laser light was delivered through a quartz cuvette containing the HAuNS or HAuNS-containing microspheres (100 µL). A thermocouple was inserted into the solution perpendicular to the path of the laser light. The temperature was measured over a period of 15 min. Phosphate-buffered saline was used as a control. The laser was a continuous-wave GCSLX–05–1600m-1 fiber-coupled diode laser (China Daheng Group, Beijing, China). A 5-m, 600-µm core BioTex LCM-001 optical fiber (Houston, TX) was used to transfer laser light from the laser unit to the target. This fiber had a lens mounting at the output that allowed the laser spot size to be changed by changing the distance from the output to the target. The output power was independently calibrated using a handheld optical power meter (model 840-C; Newport, Irvine, CA) and was found to be 1.5 W for a spot diameter of 6.5 mm (~4.5 W/cm2) and a 2-amp supply current.

PTX and HAuNS loading and encapsulation efficiency

The amount of PTX in the microspheres was determined by an Agilent 1100 Series high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Santa Clara, CA), used according to the reported procedures.[33] PTX loading was expressed as PTX content in dry microspheres (w/w). The entrapment efficiency (EE) was expressed as the percentage of the actual PTX loading over the theoretical PTX loading. The loading efficiency for HAuNS was determined by measuring the absorbance of the microspheres at 808 nm. A standard curve was constructed with known concentrations of HAuNS in aqueous solution.

NIR light-triggered release of PTX from PLGA microspheres

The release studies were performed at room temperature. A solution of 20 mg PTX/HAuNS-MS in 2 mL 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% Tween 80 was placed in a test tube. A laser probe (10 mm spot diameter) was fixed 5 cm from the center of the test tube. The samples were irradiated with the 808-nm NIR light at an output power of 2–10 W over a period of 5 min (Diomed 15 plus, Cambridge, UK). At various times, aliquots were drawn from the test tube and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min, and the released free PTX was quantified by HPLC.

In vitro cytotoxicity

Cells (1.0×104) were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h to allow the cells to attach to the surface of the wells. The cells were then exposed to 0.01–10.0 mg/mL of PTX/HAuNS-MS, HAuNS-MS, or PTX-MS. The microsphere-treated cells were irradiated 4 times with NIR light at an output power of 2 W (3-min duration each time, 1-h intervals between irradiations) and a spot diameter of 10 mm. Microsphere-treated cells not irradiated with NIR laser were used as a control. All cells were incubated at 37°C for 72 h. Cell survival was determined using the MTT cytotoxicity assay according to the manufacturer-recommended procedures. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate measurements.

To evaluate the relative contribution of the cytotoxic effect of PTX and photothermal effect of the microspheres, the cytotoxic activity of HAuNS-MS (without drug), PTX/HAuNS-MS, culture medium containing PTX/HAuNS-MS pre-treated with laser in the absence of cells, and PTX/HAuNS-MS treated with laser in the presence of MDA-MB-231 cells were compared. The concentrations of microspheres were 0.02, 1.0, 2.0, and 8.0 mg/mL. NIR light was delivered at an output power of 2 W and a spot diameter of 10 mm (2.55 W/cm2) for a period 5 min. Cell survival was determined using the MTT assay as described before. The PTX concentration in the medium after laser irradiation and after 72 h of incubation was measured by HPLC.

In vivo antitumor activity

All experiments involving animals were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Female nude mice (nu/nu; 18–22 g; 6–8 weeks of age; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation and inoculated subcutaneously with U87 cells (5×106 cells in 0.1 ml PBS). When the tumor volume reached about 100 mm3, the mice were randomly allocated into four groups (n=4–5). Groups 1 and 2 received 20-µL intratumoral injections of PTX/HAuNS-MS (PTX: 1.0 mg/kg; 4.7×109 HAuNS particles/mouse; formulation A). Group 3 received 20-µL intratumoral injections of HAuNS-MS (4.7×109 HAuNS particles/mouse; formulation D). Group 4 received 20-µL intratumoral injections of saline. Tumors in mice from groups 1, 3, and 4 were irradiated with NIR light at an output power of 1.5 W for 5 min (1 treatment/day, total of four treatments for each tumor). For NIR treatment, the laser probe (10 mm spot diameter) was fixed 4 cm from the tumors. Tumor growth was determined 2–3 times a week by measuring two orthogonal tumor diameters. Tumor volume was calculated according to the formula (a×b2)/2, where a and b are the long and short diameters of a tumor, respectively. The effect of treatment on tumor growth was expressed as the growth delay, defined as the time in days for tumors in the treated groups to grow from 100 mm3 to 500 mm3.

Antitumor efficacy was further investigated in female nude mice bearing tumors from human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells (5×106 cells in 0.1 ml PBS) inoculated orthotopically in the mammary fat pads. When the tumor volume reached about 200 mm3, the mice were randomly allocated into five groups (n = 5). Mice in groups 1–3 received intratumoral injections of PTX/HAuNS-MS (formulation A) at an equivalent PTX dose of 1.0 mg/kg (4.7×109 HAuNS particles/mouse, low dose), 6.0 mg/kg (2.82×1010 HAuNS particles/mouse, high dose), and 6.0 mg/kg (2.82×1010 HAuNS particles/mouse, high dose), respectively. Group 4 received intratumoral injections of HAuNS-MS (formulation D) at a dose of 4.7×109 HAuNS particles/mouse (low dose). Group 5 received intratumoral injections of saline. The tumors in groups 1, 2, and 4 were also irradiated with the NIR laser at an output power of 1.5 W for 5 min (2 laser treatments/day for 4 consecutive days; total 8 treatments). Tumor growth was measured weekly, using the same protocol as described above. Tumor growth delay was defined as the time in days for tumors in the treated groups to grow from 200 mm3 to 1000 mm3.

For histologic evaluation, tumors were removed and cryosectioned for hematoxylin and eosin staining. The slices were examined under a Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 microscope equipped with a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 color camera (Thornwood, NY).

Data analysis

Mean differences in the tumor growth delay (number of days required to grow from 100 mm3 to 500 mm3 for U87 tumors or from 200 mm3 to 1000 mm3 for MDA-MB-231 tumors) were analyzed by Student’s t test, with P < 0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dawn Chalaire for editing the article. This work is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 CA119387), a Seed Grant through the Alliance for NanoHealth by the Department of Army Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center (W81XWH-07-2-0101), and the John S. Dunn Foundation.

References

- 1.Lee ES, Oh KT, Kim D, Youn YS, Bae YH. J. Controlled Rel. 2007;123:19. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perelman LA, Pacholski C, Li YY, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sailor MJ. Nanomed. 2008;3:31. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai CY, Trewyn BG, Jeftinija DM, Jeftinija K, Xu S, Jeftinija S, Lin VSY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4451. doi: 10.1021/ja028650l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meers P. Adv. Drug Deliver. Rev. 2001;53:265. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ankareddi I, Hampel ML, Sewell MK, Kim D-H. Nanotech. 2007;2:431. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derfus AM, von Maltzahn G, Harris TJ, Duza T, Vecchio KS, Ruoslahti E, Bhatia SN. Adv. Mater. 2007;19:3932. [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Geest BG, Skirtach AG, Mamedov AA, Antipov AA, Kotov NA, De Smedt SC, Sukhorukov GB. Small. 2007;3:804. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deckers R, Rome C, Moonen CTW. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2008;27:400. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernot S, Klibanov AL. Adv. Drug Deliver. Rev. 2008;60:1153. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HJ, Matsuda H, Zhou HS, Honma I. Adv. Mater. 2006;18:3083. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Needham D, Dewhirst MW. Adv. Drug Deliver. Rev. 2001;53:285. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang ZY, Smith BD. Bioconjug. Chem. 1999;10:1150. doi: 10.1021/bc990087h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wijtmans M, Rosenthal SJ, Zwanenburg B, Porter NA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11720. doi: 10.1021/ja063562c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez-Lorenzo C, Bromberg L, Concheiro A. Photochem. Photobiol. 2009;85:848. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch LR, Stafford RJ, Bankson JA, Sershen SR, Rivera B, Price RE, Hazle JD, Halas NJ, West JL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:13549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loo C, Lin A, Hirsch L, Lee MH, Barton J, Halas N, West J, Drezek R. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2004;3:33. doi: 10.1177/153303460400300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu W, Xiong C, Zhang G, Huang Q, Zhang R, Zhang JZ, Li C. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:876. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melancon MP, Lu W, Yang Z, Zhang R, Cheng Z, Elliot AM, Stafford J, Olson T, Zhang JZ, Li C. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1730. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang XH, El-Sayed IH, Qian W, El-Sayed MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2115. doi: 10.1021/ja057254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi H, Niidome T, Nariai A, Niidome Y, Yamada S. Chem. Lett. 2006;35:500. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weissleder R. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:316. doi: 10.1038/86684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bikram M, Gobin AM, Whitmire RE, West JL. J. Controlled Rel. 2007;123:219. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bedard MF, Braun D, Sukhorukov GB, Skirtach AG. ACS Nano. 2008;2:1807. doi: 10.1021/nn8002168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu G, Mikhailovsky A, Khant HA, Fu C, Chiu W, Zasadzinski JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8175. doi: 10.1021/ja802656d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.You J, Cui FD, Li QP, Han X, Yu YW, Yang MS. Int. J. Pharm. 2005;288:315. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liggins RT, Hunter WL, Burt HM. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997;86:1458. doi: 10.1021/js9605226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowinsky EK, Cazenave LA, Donehower RC. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1247. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.15.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu Q, Vincent M, Logan D, Mackay JA, Evans WK. Lung Cancer. 2005;50:355. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schrijvers D, Vermorken JB. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2005;17:218. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000158735.91723.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saloustros E, Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V. Exp. Opin. Pharmacother. 2008;9:2603. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.15.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson JK, Hung T, Letchford K, Burt HM. Int. J. Pharm. 2007;342:6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Iglesias A, Grzelczak M, Rodriguez-Gonzalez B, Guardia-Giros P, Pastoriza-Santos I, Perez-Juste J, Prato M, Liz-Marzan LM. ACS Nano. 2009;3:3184. doi: 10.1021/nn9006169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.You J, Hu FQ, Du YZ, Yuan H. Biomacromol. 2007;8:2450. doi: 10.1021/bm070365c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]