Abstract

Hyoid fractures in athletes are rare injuries that can be difficult to diagnose. Typically resulting from a direct blow to the anterior neck, hyoid fractures can lead to subcutaneous edema and subsequent airway compromise. The treatment of this fracture depends largely on the severity of the presenting symptoms. Generally, these fractures do not require surgical intervention but warrant close observation for delayed onset of airway obstruction. To raise awareness of this potentially dangerous fracture, the authors present 2 cases of isolated hyoid fractures in collegiate football players at our institution.

Keywords: hyoid fracture, athletes, football

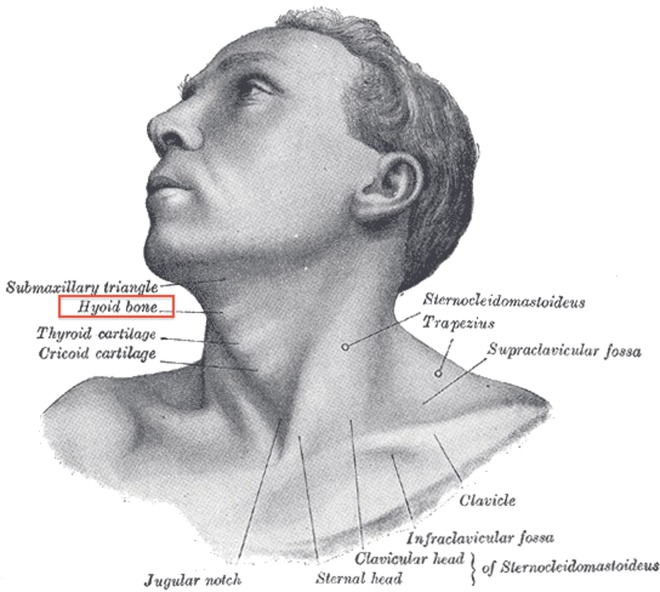

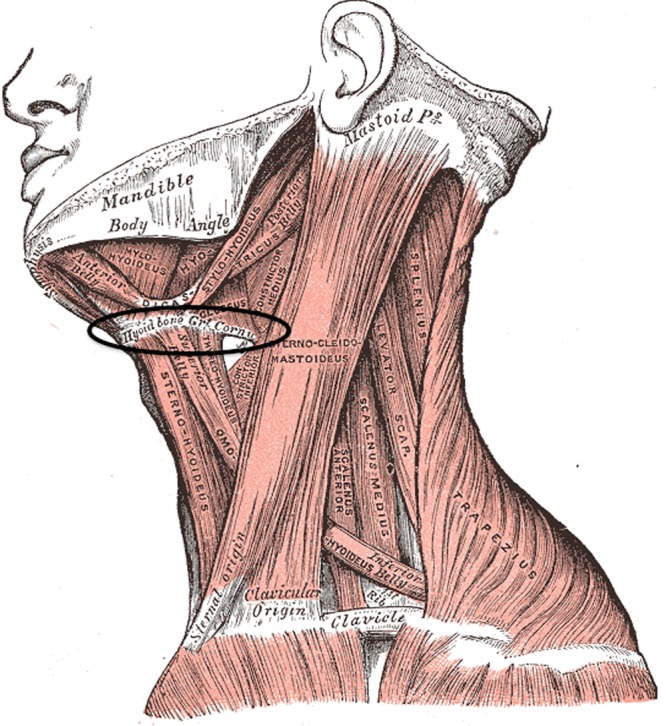

The hyoid bone lies inferior to the protruding mandible bone and anterior to the cervical spine (Figure 1). These structures protect the hyoid from direct injury, making isolated fractures of hyoid bone rare. Most hyoid fractures are the result of motor vehicle accidents or strangulations; to date, only 3 cases of hyoid fractures with sports-related mechanisms (basketball, ice hockey, and karate) have been reported.5,6,8,15

Figure 1.

The hyoid bone lies inferior to the protruding mandible bone, superior to thyroid cartilage, and anterior to the cervical spine. These structures protect the hyoid from direct-impact injury; however, neck extension increases its exposure and risk to direct and indirect trauma.

Used with permission from Henry Gray, Anatomy of the Human Body (Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1918).

The diagnosis of a hyoid fracture can be difficult and may be easily overlooked. Hyoid fractures can result in potentially devastating sequelae, including subcutaneous edema and subsequent airway compromise that may necessitate surgical airway institution.9-12 This anatomically small but potentially dangerous fracture was diagnosed in 2 collegiate football players in the same week.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 21-year-old collegiate football player sustained a hit to his anterolateral neck by another player’s helmet during a full-contact football practice session. When the collision occurred, the injured player had his appropriately fitted football helmet fully secured with a chin strap. There was immediate anterior neck pain, but the player was able to finish the practice. Later that evening, he developed progressive dysphagia, odynophagia, and voice changes, which led him to report the incident to athletic trainers. The player denied shortness of breath or dyspnea but reported mild hemoptysis, labored swallowing, and increased anxiety. He denied headaches, loss of consciousness, upper extremity weakness, and paresthesia. He was taken to the emergency department, where he underwent further evaluation.

Physical examination revealed normal vital signs, including respiratory rate, no stridor or anterior cervical ecchymosis, normal oral cavity, symmetrical uvula and palate, and normal results from nasal and mandibular examination with diffuse right-side anterior neck tenderness. Findings from cranial nerve examination were normal.

Imaging included 2 cervical spine octagonal radiographs, which revealed normal results. Cervical computed tomography (CT) angiography revealed normal extracranial carotid and vertebral arteries and a fracture of the right greater horn of the hyoid bone (cornua majora). There was mild diastasis of the right hyoid synchondrosis, with a subtle effacement of the right paralaryngeal fat adjacent to the fracture, suggestive of soft tissue edema (Figure 2). Because of ongoing vocal changes and dysphagia, the player underwent nasopharyngoscopy demonstrating normal endolarynx without lacerations, swelling, or hematoma.

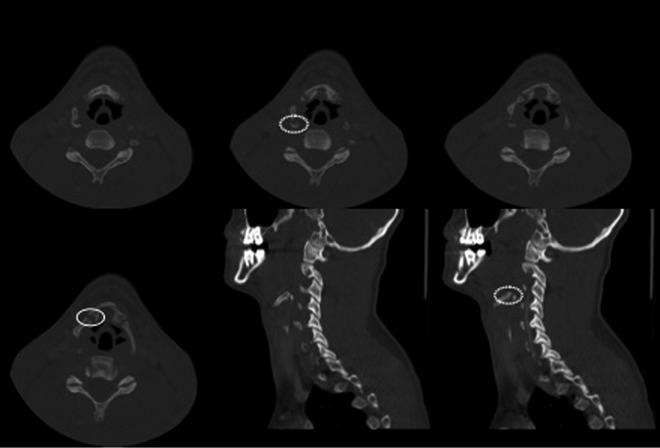

Figure 2.

Cervical computed tomography angiography demonstrates a small fracture of the right greater horn (dotted circle). Also shown is mild diastases of the right hyoid synchondrosis (solid circle) with a subtle effacement of the right paralaryngeal fat adjacent to the fracture suggestive for edema.

The player was admitted for 48 hours of observation on liquid diet and gradually progressed. He was restricted at practice for 11 days, allowing only running, conditioning, and noncontact drills. On postinjury day 14, he was symptom free and cleared for full participation.

Case 2

A 21-year-old collegiate football player sustained a direct blow to the anterior neck in a collision with another player while standing on the sideline. His helmet was unsecured when another player collided with him, forcing his face mask down into his anterior neck. He immediately experienced anterior neck pain, voice changes, hoarseness, and difficulty swallowing.

Immediate physical examination revealed normal vital signs without stridor, anterior cervical ecchymosis, or crepitus. He had a normal oral cavity, symmetrical uvula/palate, and nontender mandible/maxilla. He had diffuse right-side anterior neck tenderness with normal cranial nerves. He did not have hemoptysis but reported odynophagia and labored swallowing of liquids. Because of voice changes, persistent odynophagia, and labored swallowing, he was taken to the emergency department for further evaluation.

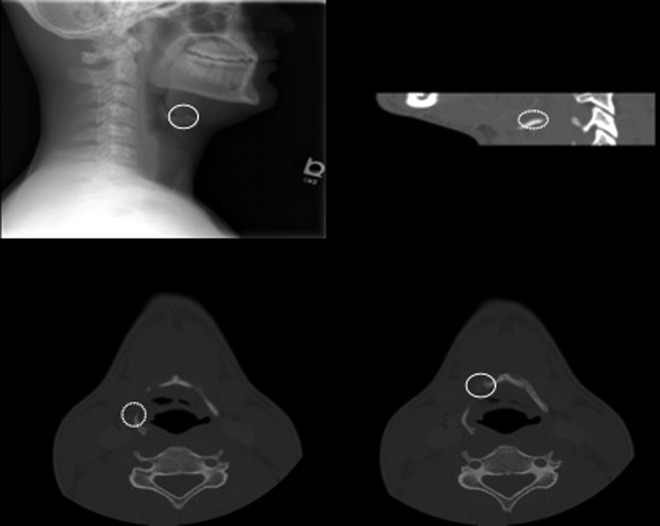

Two octagonal soft tissue neck radiographs did not demonstrate prevertebral soft tissue swelling or retropharyngeal gas. He had a widely patent airway with a vertical lucency through the hyoid bone, representing a hyoid fracture (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Octagonal soft tissue neck radiographs do not demonstrate prevertebral soft tissue swelling or retropharyngeal gas. There is a widely patent airway and a vertical lucency on the lateral view of the hyoid bone suggestive of the fracture (circle).

Cervical CT angiography demonstrated a fracture through the right greater horn (cornua majora) of the hyoid bone with inferomedial angulation of the more posterior fragment (Figure 4). There was slight diastasis of the synchondrosis between the hyoid body and the right greater horn without significant surrounding soft tissue edema.

Figure 4.

Plain lateral radiograph and computed tomography images demonstrating fracture through the right greater horn (dotted circle) with inferomedial angulation of the more posterior fragment. There is a small diastasis of the synchondrosis between the hyoid body and the right greater cornu (solid circle).

Flexible laryngoscopy was performed because of ongoing dysphagia, odynophagia, and vocal changes, and it showed normal vocal cords, patent subglottis, and normal supraglottic structures.

He was admitted for 24 hours for observation and progressed from a liquid diet. After 3 days of rest, he began running and noncontact drills. After 6 days, he was cleared to full-contact practice and was completely symptom free on day 7.

Discussion

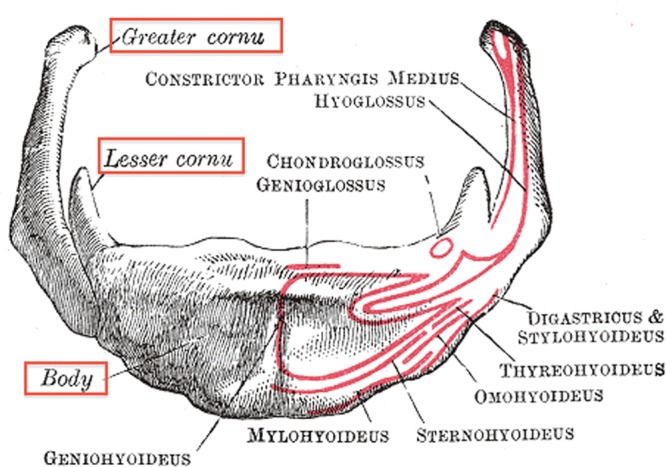

Fracture of the hyoid bone is rare, accounting for only 0.002% to 1% of all fractures.6,17 It can cause pharyngeal laceration or anterior cervical soft tissue swelling, leading to secondary airway compromise.9-12 The hyoid bone is located in the anterior neck at the level of C3-4, and it consists of the body and greater and lesser horns (Figure 5). The fibrous connection between the greater horns and the body undergoes full osseous fusion in adulthood. In both cases, partial diathesis of this synchondrosis was recognized on the radiographs and CT scans and suggested hyoid trauma (Figure 4). Hyoid fractures are classified according to the anatomy mechanism and the direction of force (anterior-posterior compression and avulsion).13,19

Figure 5.

Hyoid bone consists of the body and the greater and lesser horns. The fibrous connection between the greater horns and the body undergoes full osseous fusion in midadulthood. Multiple anterior neck muscles insert on its superior an inferior surface.

Used with permission from Henry Gray, Anatomy of the Human Body (Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1918).

The hyoid bone supports muscular attachments. The suprahyoid, stylohyoid, geniohyoid, and infrahyoid muscles elevate and elongate and, conversely, depress and shorten the floor of the mouth during swallowing (Figure 6). The function of surrounding musculature explains the labored swallowing and odynophagia associated with injury to the hyoid bone. Sudden cervical hyperextension, with or without a direct blow to the neck, can cause isolated hyoid fractures.14

Figure 6.

Hyoid bone has numerous muscular attachments that allude to its biomechanical function in the anterior neck. The intricate function of surrounding musculature explains the labored swallowing and odynophagia associated with injury to the hyoid bone.

Used with permission from Henry Gray, Anatomy of the Human Body (Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1918).

In both these cases, injury occurred with a direct blow to the anterior neck. Both athletes noticed progressive pain with swallowing, difficulty with drinking and eating, and anterior neck pain exacerbated by cervical extension and lateral rotation.

Symptom presentation was variable, with the first athlete able to continue practice. Worsening symptoms occurred 4 to 6 hours following the trauma. In the second case, symptoms occurred immediately after the impact, preventing the athlete from continuing practice. Both players developed voice changes, hoarseness, and pain with phonation immediately after the injury.

Papavasiliou and Speas identified the oblique view of the cervical spine to visualize the hyoid bone, eliminating superimposition of the 2 horns.16 This view may be best for screening athletes with anterior cervical trauma. The hyoid fracture can go undetected unless the examiner maintains a high degree of suspicion.21

CT scan is recommended for anterior neck pain, dysphagia, voice changes, and hemoptysis because it can confirm hyoid fractures and simultaneously image associated injuries, including cervical spine10 and mandibular fractures,6 vascular trauma2 and pharyngeal lacerations.4 Laryngoscopy is highly recommended in cases of hemoptysis, dyspnea, and voice changes, and it assesses active and passive vocal cord motility.6,9,14

Management of hyoid fractures is determined largely by the severity of symptoms. Asymptomatic fractures require close observation. Analgesics, soft collar immobilization, and liquid/soft diet modification can be useful. As dysphagia, odynophagia, anterior neck pain, and voice improve, diet progression and outpatient follow-up can be initiated. Most athletes may resume athletic activities with return of painless swallowing, normal cervical range of motion, and resolution of dysphonia.5,6,8,15

Symptomatic hyoid fractures associated with pharyngeal lacerations may require surgical repair or partial hyoid excision.7,13 In the case of respiratory compromise, rapid intervention to secure the airway, either with endotracheal intubation or surgical tracheostomy, should be considered.11,20

Both athletes were monitored for 24 to 48 hours as inpatients and released after their diet progressed and odynophagia and dysphonia improved. Long-term sequelae of hyoid fractures are rare but can involve persistent dysphagia1 or pseudoaneurysm of the external carotid artery.2

Athletes presenting with direct trauma to the anterior neck with dysphagia, difficulty swallowing, coughing, voice changes, and anterior neck pain should be carefully evaluated clinically and radiographically. Anterior neck trauma should be monitored even in the absence of these signs because of the possible delay in the onset of symptoms as well as the risk of progression to airway obstruction.3,18,20,22

References

- 1. Anthony R, Martin-Hirsch D, England J. Dysphagia secondary to iatrogenic hyoid bone fracture. Br J Neurosurg. 2000;14:337-338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Campbell AS, Butler AP, Grandas OH. A case of external carotid artery pseudoaneurysm from hyoid bone fracture. Am Surg. 2003;69:534-535 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carroll B, Boulanger B, Gens D. Hyoid bone fracture secondary to gunshot. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10:177-179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chadwick DL. Closed injuries of the larynx and pharynx. J Laryngol Otol. 1960;74:306-324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chowdhury R, Crocco AG, El-Hakim H. An isolated hyoid fracture secondary to sport injury: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:411-414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dalati T. Isolated hyoid bone fracture: review of an unusual entity. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:449-452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. David S, Corrigan AM. Fracture of the hyoid bone presenting as a dislocated mandible. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1989;18:89-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dohring A, Kahle M. [Isolated hyoid bone fractures] [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2000;103:996-998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eliachar I, Goldsher M, Golz A, Joachims HZ. Hyoid bone fractures with pharyngeal lacerations. J Laryngol Otol. 1980;94:331-335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Graf C. Laceration of the pharynx with fracture of the hyoid bone: report of a case and discussion. J Trauma. 1969;9:812-818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaufman HJ, Ciraulo DL, Burns RP. Traumatic fracture of the hyoid bone: three case presentations of cardiorespiratory compromise secondary to missed diagnosis. Am Surg. 1999;65:877-880 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krekorian KA. Perforation of the pharynx with fracture of the hyoid bone. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1964;73:583-594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lakhia TS, Shah RB, Kapoor L. Fracture of the hyoid bone. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:232-234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levine E, Taub P. Hyoid bone fractures. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73:1015-1018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maran AG, Stell PM. Acute laryngeal trauma. Lancet. 1970;28(7683): 1107-1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Papavasiliou CG, Speas CJ. Fractures of the hyoid bone. Radiology. 1959;72:872-874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stiebler A, Maxeiner H. [Non-strangulation-induced injuries of the larynx and hyoid bone] [article in German]. Beitr Gerichtl Med. 1990;48:309-315 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Szeremeta W, Morovati SS. Isolated hyoid bone fracture: a case report and review of the literature. J Trauma. 1991;31:268-271 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weintraub CM. Fractures of the hyoid bone. Med Leg J. 1961;29:209-216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whyte AM. Fracture of the hyoid bone associated with a mandibular fracture. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:805-807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zachariades N. Fracture of the hyoid bone: an unusual case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;59:663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zachariades N, Mezitis M. Fracture of the hyoid bone: report of a case. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:402-405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]