Abstract

Background:

Several sports medicine reviews have highlighted a 3- to 6-month time frame for return to play after splenic lacerations. These reviews are based on several well-defined grading scales for splenic injury based on computed tomography (CT). None of the articles suggest that serial CT scanning is necessary for follow-up; some even indicate that it has no role in the management of these injuries.

Hypothesis:

With proper follow-up and possibly the use of serial CT scanning or other imaging modalities, it may be possible for athletes to safely return to play sooner than what current guidelines recommend.

Study Design:

The authors present 2 cases of professional hockey players who both suffered grade III splenic lacerations while playing.

Methods:

Both players were treated conservatively and monitored with serial CT scanning until radiographic and clinical findings suggested complete healing.

Results:

Both players were able to return to full-contact professional hockey within 2 months after suffering grade III splenic lacerations. Neither athlete suffered any complications after his return.

Conclusions:

With CT scanning, 2 athletes were able to return to play earlier (2 months) than previously recommended (3-6 months) without compromising their safety.

Clinical relevance:

Additional cases must be examined before outlining more definitive recommendations regarding splenic lacerations in sports, but it is possible that elite athletes may return to play sooner than what the current literature recommends.

Keywords: spleen, laceration, hockey, return to play

The spleen is the most frequently injured abdominal organ in sports and the most common cause of death due to abdominal trauma among athletes,16 yet no consensus exists in regard to nonoperative management and return to play. We present 2 unique cases of splenic lacerations in professional hockey players who returned to play within 2 months of their injuries. These players were treated nonoperatively and monitored with intravenous contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT), allowing them to return to play in significantly less time than what many sports medicine physicians currently recommend.

Case 1

A 24-year-old male professional hockey player was checked hard against the boards during a game. He continued to play and completed the game. He described minimal discomfort to the team’s athletic trainer after the game and was observed. He presented to the team physician the following day with mild left upper abdominal and left shoulder pain. A CECT was obtained that demonstrated a 3-cm laceration extending from the capsule to the hilum with an associated hemoperitoneum, consistent with a grade III splenic laceration (Figure 1A).14 There was no active extravasation. After an outpatient trauma surgery evaluation, the player refrained from physical activity, and a follow-up CECT scan was planned for 3 weeks.

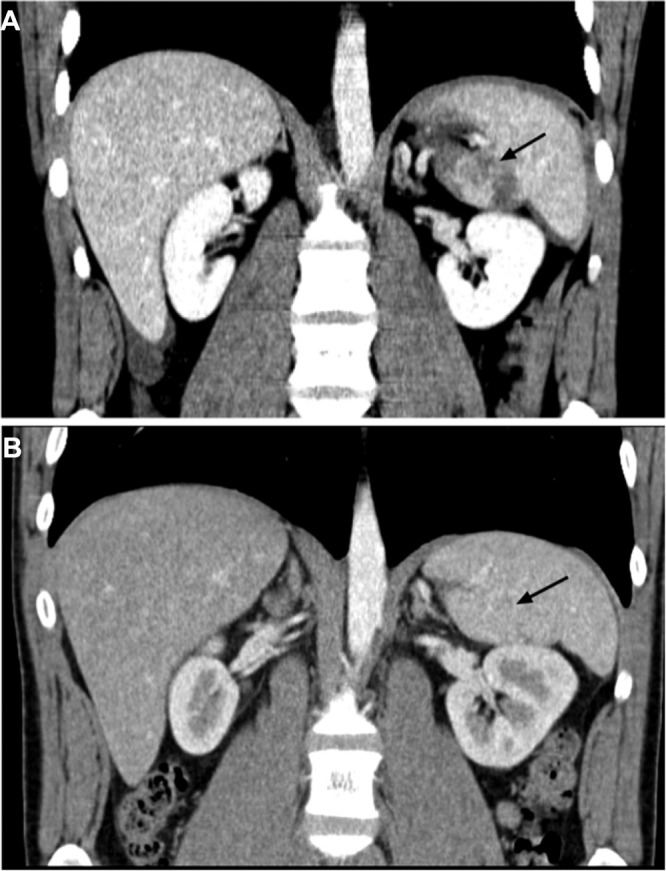

Figure 1.

Coronal reformatted images of the abdomen demonstrate a low attenuation splenic laceration adjacent to the splenic hilum: A, day 1 with resolution; B, day 59. Images acquired following the intravenous administration of iohexol (Omnipaque 300; 100 mL) on a Siemens Sensation 40 scanner (slice collimation, 24 × 1.2 mm; 0.8 pitch; 120 kV; reference, 300 mA, utilizing dose modulation or similar protocol; reformats: axial, 3 mm; sagittal, 2 mm; coronal, 2 mm).

Four days later, the patient presented to the emergency department with increasing left upper quadrant pain radiating to the left shoulder. A repeat CECT demonstrated mildly increased hemoperitoneum extending into the pelvis. The size of the laceration was unchanged, and the patient’s hematocrit level was 40.2%. He was given intravenous fluids, which improved his condition and pain. He was admitted to the intensive care unit for observation while he was further hydrated. His hematocrit level remained stable, and he was discharged 2 days later.

Two days after discharge, he presented with new right-sided upper quadrant and lower chest pain. CECT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed persistent hemoperitoneum with a small pleural effusion. His hematocrit reading was 34.6%. He was given intravenous fluids and discharged from the hospital.

Twenty-one days after the injury, he became asymptomatic; a follow-up appointment at 29 days confirmed clinical resolution, and a repeat CECT showed a healing splenic laceration without significant intraabdominal fluid. He was allowed to begin light aerobic activities with gradual advancement as tolerated. At the final follow-up visit, the player was clinically asymptomatic. An abdominal CECT at 59 days postinjury demonstrated complete resolution of the laceration and hemoperitoneum (Figure 1B). He was cleared to resume full practice without restriction the following day. His return to hockey was uneventful.

Case 2

A 29-year-old male professional hockey player suffered similar trauma while being checked against the boards. He completed the game but afterward developed generalized abdominal pain and was sent to a local hospital for evaluation. A CECT demonstrated a fractured 11th rib and a 4-cm splenic laceration sparing the hilum, consistent with a grade III splenic laceration. There was no active extravasation or hemoperitoneum. He was admitted for observation. During his hospitalization, his hematocrit level was stable. He was discharged on hospital day 5.

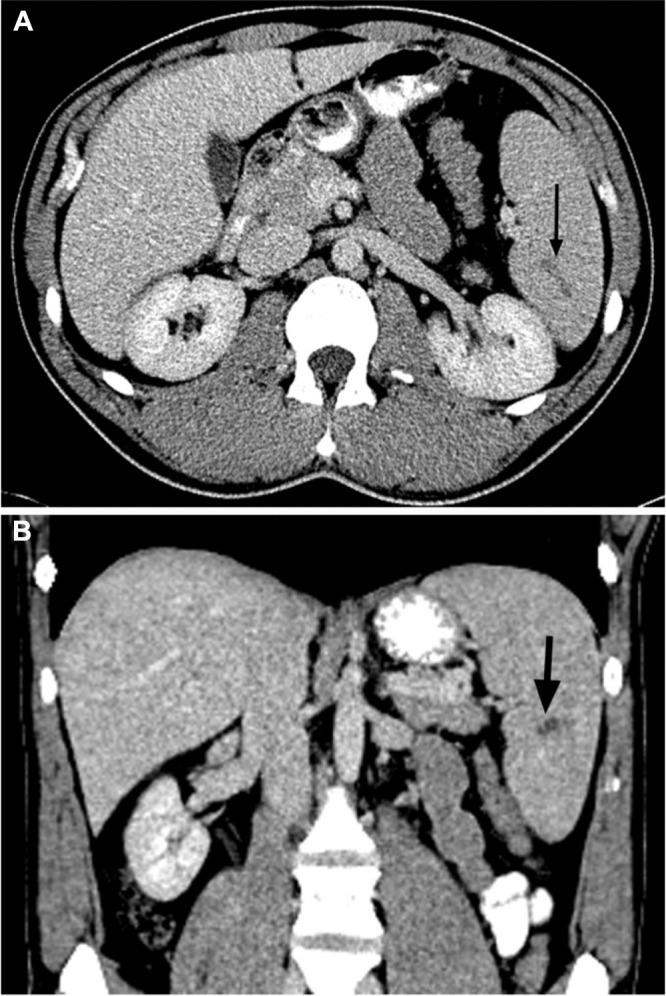

The player visited our sports medicine clinic 19 days after the injury. He had been asymptomatic since postinjury day 14 but was advised to refrain from extensive physical activity. One week later (4 weeks postinjury), a CECT showed a healing grade III splenic laceration (Figure 2). There was no associated hematoma or hemoperitoneum.

Figure 2.

Day 19: axial (A) and coronal (B) contrast-enhanced computed tomography images of the abdomen demonstrating a low attenuation splenic laceration adjacent to the splenic hilum.

Fifty-four days postinjury at follow-up with a traumatologist, he was asymptomatic. A CECT demonstrated a completely resolved splenic laceration. He was permitted by team physicians to return to hockey and was provided with a graded exercise program. He returned uneventfully to full-contact hockey 61 days postinjury.

Discussion

Splenic injuries often present with vague symptoms and may be difficult to diagnose. The first patient demonstrated the Kehr sign, which is pain in the left shoulder after blunt abdominal trauma and can be a sign of splenic damage.10 It is a nonspecific finding, especially in the setting of athletic collision.

The use of serial computed tomography (CT) evaluation has vastly improved diagnostic and prognostic capabilities in the setting of blunt trauma to the spleen, but there is no consensus regarding the necessity or timeline of such follow-up. Splenic injuries from direct trauma include laceration, hematoma, and infarction; these can be identified by CT.2 The most widely used tool for grading splenic injury on CT is the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma’s Organ Injury Scale.14 The majority of evidence supports the use of CT in the evaluation of splenic injury; the impact of clinical correlation, regardless of CT grading, is an issue. A recent review by the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma concluded that there is no evidence to support the use of routine CT scanning of clinically improving patients.1 However, this recommendation is based on all hospitalized patients and does not consider the special circumstances of professional athletes.

Currently, nonoperative management of hemodynamically stable patients with splenic injuries up to grade III is the preferred method of treatment, but return-to-play guidelines are not well defined.8 When caring for professional athletes, establishing a time frame that maximizes healing and minimizes complications and missed playing time is crucial.

A recent sports medicine review of splenic injuries in athletes shows that the differences in return-to-play guidelines among physicians are vast.8 A survey of Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practitioners found no discernable pattern regarding the recommendation for return to contact sports after splenic trauma.5 Savage et al indicated that splenic healing occurs within 2 to 2.5 months, regardless of the severity of initial injury, but they stressed the importance of clinical correlation.17 Within the pediatric surgical literature, multiple authors support 3 months for healing prior to return to activity.3,7,15 Return-to-play decisions are inherently difficult in professional athletes without data to support extended recovery time. In fact, there are case reports of high level athletes choosing splenectomy, rather than nonoperative healing, to return to full-contact sports.18

Performing intravenous CECT scans provides timely and detailed diagnosis of abdominal injuries, including splenic injury, following trauma.20 Some authors do not recommend reimaging the spleen with CECT to determine healing, but the available literature does not address the challenges of treating professional athletes.1,8,9,19 CECT has both a monetary cost and a radiation exposure cost. The range of radiation exposures from a single CECT of the abdomen and pelvis in the literature is approximately 3.5 to 25 mSv (approximately 4.5-5.3 mSv per scan at our institution).12 The professional hockey player in case 1 received 5 total scans, 2 of which were performed early in recovery secondary to worsening symptoms. The player in case 2 received 3 scans. In total, these players incurred a radiation exposure higher than that of the average population.6 Despite the lack of scientific evidence demonstrating a causative relationship between medical radiation exposure and cancer, there has been mounting concern over growing medical radiation exposure based on the epidemiologic data from atomic bomb survivors.6,12 Some authors contend that this fear is exaggerated, and they argue in favor of medical necessity.13 In response to these concerns, the pediatric literature has suggested follow-up with ultrasound.4,11 Likewise, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may provide a means to evaluate splenic healing following trauma. However, there is no specific literature comparing the accuracy of CECT, ultrasound, and MRI in documenting splenic healing. CECT remains the imaging modality of choice for the initial evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma, and further study is required before recommending ultrasound or MRI for follow-up imaging. Serial clinical examination complemented with CECT imaging may allow high-level athletes to return to play earlier than what current guidelines recommend. The periodic clinical evaluation and repeat CECT scans were used to carefully evaluate the course of healing of these lacerations. As soon as these athletes were asymptomatic and imaging demonstrated complete healing, both were permitted to resume play without restriction and had uneventful returns to professional hockey.

Conclusions

These 2 cases illustrate that splenic injuries must be dealt with on a case-by-case basis, and they question the notion that activity restrictions must be imposed for 3 months or more as previously published.3,7,8,15 Neither of these athletes has experienced sequelae from his injury, and both continue to play professional hockey. Our current practice is to allow athletes with splenic lacerations to resume unrestricted sporting activities when symptoms have resolved and complete healing is documented by CECT. Given the clinical experience from these 2 cases, providers should consider reimaging approximately 8 weeks postinjury or 6 weeks from the resolution of symptoms. Additional cases must be examined before outlining more definitive recommendations and return-to-play timelines regarding splenic lacerations in sports. Likewise, further study is required before recommending ultrasound or MRI for evaluation of splenic healing.

References

- 1. Alonso M, Brathwaite C, Garcia V, et al. ; EAST Practice Management Guidelines Work Group. Practice Management Guidelines for the Nonoperative Management of Blunt Injury to the Liver and Spleen. Chicago, IL: Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma; 2003:1-32 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Becker CD, Mentha G, Terrier F. Blunt abdominal trauma in adults: role of CT in the diagnosis and management of visceral injuries. Part 1: liver and spleen. Eur Radiol. 1998;8(4):553-562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown RL, Irish MS, McCabe AJ, Glick PL, Caty MG. Observation of splenic trauma: when is a little too much? J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34(7): 1124-1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Emery KH, Babcock DS, Borgman AS, Garcia VF. Splenic injury diagnosed with CT: US follow-up and healing rate in children and adolescents. Radiology. 1999;212(2):515-518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fata P, Robinson L, Fakhry SM. A survey of EAST member practices in blunt splenic injury: a description of current trends and opportunities for improvement. J Trauma. 2005;59(4):836-841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fazel R, Krumholz HM, Wang Y, et al. Exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):849-857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gandhi RR, Keller MS, Schwab CW, Stafford PW. Pediatric splenic injury: pathway to play? J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34(1):55-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gannon EH, Howard T. Splenic injuries in athletes: a review. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2010;9(2):111-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lawson DE, Jacobson JA, Spizarny DL, Pranikoff T. Splenic trauma: value of follow-up CT. Radiology. 1995;194(1):97-100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lowenfels AB. Kehr’s sign: a neglected aid in rupture of the spleen. N Engl J Med. 1966;274(18):1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lynch JM, Meza MP, Newman B, Gardner MJ, Albanese CT. Computed tomography grade of splenic injury is predictive of the time required for radiographic healing. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32(7):1093-1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marin D, Nelson RC, Rubin GD, Schindera ST. Body CT: technical advances for improving safety. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197(1):33-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McCollough CH. Defending the use of medical imaging. Health Phys. 2011;100(3):318-321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Jurkovich GJ, Shackford SR, Malangoni MA, Champion HR. Organ injury scaling: spleen and liver (1994 revision). J Trauma. 1995;38(3):323-324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pranikoff T, Hirschl RB, Schlesinger AE, Polley TZ, Coran AG. Resolution of splenic injury after nonoperative management. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29(10):1366-1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rifat SF, Gilvydis RP. Blunt abdominal trauma in sports. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2003;2(2):93-97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Savage SA, Zarzaur BL, Magnotti LJ, et al. The evolution of blunt splenic injury: resolution and progression. J Trauma. 2008;64(4):1085-1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Terrell TR, Lundquist B. Management of splenic rupture and return-to-play decisions in a college football player. Clin J Sport Med. 2002;12:400-402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thaemert BC, Cogbill TH, Lambert PJ. Nonoperative management of splenic injury: are follow-up computed tomographic scans of any value? J Trauma. 1997;43(5):748-751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Walter KD. Radiographic evaluation of the patient with sport-related abdominal trauma. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2007;6(2):115-119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]