Abstract

Background:

Medial elbow injuries are common among baseball pitchers. Easily accessed methods to assess medial elbow stress may be useful in identifying individuals with increased injury risk.

Hypothesis:

Pitch velocity (PV) is positively associated with higher medial elbow adduction moments.

Study Design:

Cohort study; Level of evidence, 2.

Methods:

Participants included 26 uninjured high school pitchers, 15 to 18 years in age. Three-dimensional data and PV were collected as athletes threw 10 fastballs for strikes to a regulation-distance target. Variables of interest were the normalized peak internal elbow adduction moment and peak PV. Linear regression was performed to evaluate the influence of PV on the adduction moment.

Results:

For the group, mean PV was 71 mph (range, 58-81 mph), and the adduction moment was 0.558 Nm/Ht × mass (range, 0.378-0.723). PV was positively associated with the adduction moment (P < 0.01, R2= 0.373).

Conclusions:

Talented young pitchers may be more susceptible to elbow injuries as a consequence of a biomechanical coupling between PV and upper extremity joint moments.

Clinical Relevance:

PV may be measured easily and serve as an indicator of medial elbow stress.

Keywords: biomechanics, throwing, upper extremity, adolescent, injury risk

Elbow injuries in the youth baseball athlete are a concern. Lyman et al12 reported that 26% of adolescent pitchers experience elbow pain in a given season, and the number of reconstructive surgeries performed to treat ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) injury among youth players is increasing.3 The injury mechanism for medial elbow injuries has been attributed to excessive ligament tension during the late phase of cocking.7 This may result in an acute tear or, more frequently, the repetitive microtrauma over multiple seasons, resulting in a degenerative tear.15 Thus, minimizing medial elbow tension experienced during pitching is a reasonable strategy for prevention of UCL injury.

Multiple risk factors for elbow injury in the youth baseball pitcher have been identified.11,12,14 Pitch volume over the course of a season and year, type of pitches thrown, pitching with arm fatigue, advancing age and weight, and inadequate rest over the course of a year have all been associated with throwing-related elbow pain and injury.11,12,14 More recently, greater pitch velocity (PV) has been related to an increased risk of elbow injury in youth and adult pitchers.2,14 The association between throwing velocity and elbow injury is alarming, as increasing velocity is the goal of many pitchers. Furthermore, a high PV is considered a hallmark of talented youth pitchers, suggesting that the best pitchers may be the most vulnerable to injury.

Biomechanical studies have provided insight into the relationship between PV and elbow injury.2,5 Escamilla et al5 compared the biomechanics of uninjured American (n = 11) and Korean (n = 8) professional pitchers. The investigators reported that the American group had a 10% greater PV than the Korean group. The American pitchers also exhibited greater medial elbow varus torque. Although Escamilla et al5 hypothesized that the difference in elbow kinetics might be attributed to pitching velocity, this relationship was not evaluated.

Identifying risk factors for elbow injuries is necessary for development and implementation of effective injury prevention programs. Although higher medial elbow adduction moments of the elbow have been associated with changes in UCL appearance9 and injury risk, 3-dimensional motion analysis testing is not available for all athletes. Ideally, injury risk factors should be identified with readily available resources. Establishing PV as a surrogate of medial elbow stress may be a clinically useful means for identifying athletes at increased risk for injury. Furthermore, the association between PV and medial elbow kinetics has not been described. Thus, the purpose of this investigation was to assess the relationship between PV and 3-dimensional elbow kinetics. We hypothesized that PV would be positively associated with higher medial elbow adduction moments.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Twenty-six uninjured high school–aged baseball pitchers participated in a study approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Eligibility included a minimum of 3 years of experience as a starting pitcher in organized baseball preceding study enrollment, age of 14 to 18 years, absence of throwing arm injury, no physical limitations with baseball activities, and a willingness to participate in the study. The absence of injury was confirmed by a physical examination performed by a board-certified sports physical therapy specialist (WJH). Unrestricted participation in baseball activities was confirmed by a QuickDash sports score of ≤ 10%.8

Procedures

After consent and parental assent were obtained, participants completed a 10- to 15-minute warm-up that included jogging, stretching, level ground tossing, and off-the-mound pitching. They then threw pitches from a portable pitching mound to a target. Three-dimensional throwing limb and trunk biomechanics and PV were simultaneously collected while athletes pitched. All procedures were performed in a biomechanics research laboratory.

Data Collection

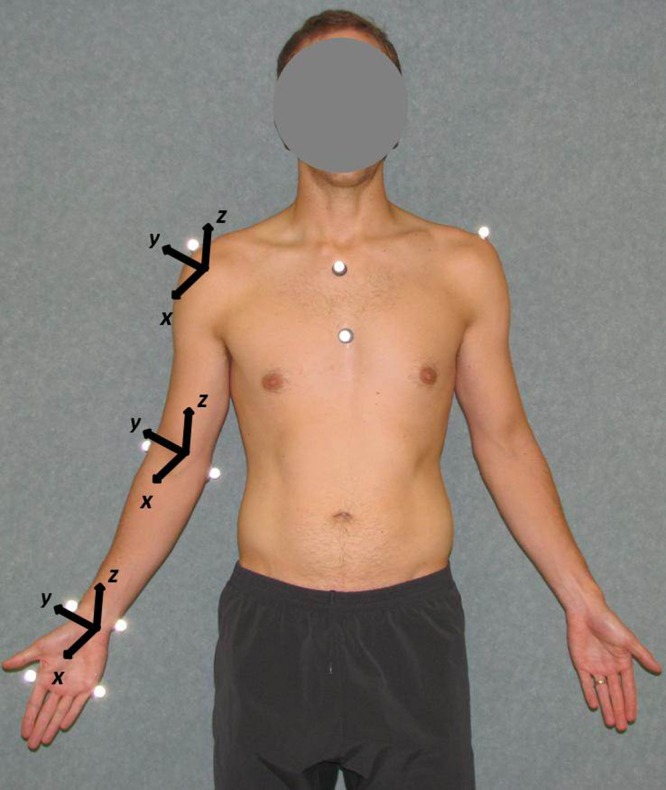

Three-dimensional trunk and throwing limb biomechanics were collected with a 10-camera, 3-dimensional motion capture system (Motion Analysis Corp, Santa Clara, California). Motion data were collected at 500 Hz and low pass filtered at 6 Hz with a fourth-order, zero-lag digital Butterworth filter. Retroreflective markers were secured over anatomic landmarks (bilaterally over the distal acromion, lateral second metacarpal head, medial fifth metacarpal head, radial and ulnar styloid processes, medial and lateral epicondyles of the elbow, spinous process of the 7th and 12th vertebrae, xiphoid process, and sternal notch) to define joint centers, joint axes, measure segment length, and track motion (Figure 1). Laboratory precision of 3-dimensional kinematics was within 2°. Two-dimensional video data were also captured from 3 digital cameras (Sony Corp, New York, New York) which provided full-body anterior, lateral, and overhead views.

Figure 1.

Anterior view of marker placement and axis orientations for the upper extremity.

A 3-dimensional motion capture static reference trial to define joint axes was captured prior to pitching while participants were positioned in an anatomic neutral posture within the collection volume. The coordinate system was defined as follows: anterior (+) and posterior (–) of the x axis, medial (+) and lateral (–) of the y axis, and superior (+) and inferior of the z axis (Figure 1). The testing protocol consisted of throwing fastballs from an indoor pitching mound to a regulation-distance strike zone target (18.4 m) using a full windup. An examiner positioned behind the target recorded PV with a radar gun (Jugs Sports, Tualatin, Oregon). Manufacturer-reported precision of the radar gun was ±0.5 mph. Testing was concluded after 10 pitches had been thrown for strikes. Pitches that deviated more than ±5% of the mean velocity were excluded from analysis.

Data Management

Three-dimensional throwing limb calculations were based on a previously described model.13 The upper extremity model was developed using Visual3D (C-Motion Inc, Germantown, Maryland) and consisted of rigid body segments including the trunk, upper arm, lower arm, and hand. Joint kinetics were derived using inverse dynamics.10 The inertial properties4 of the segments were input into the model. The force applied by the baseball to the hand was calculated using an impulse momentum relationship with the baseball modeled as a 142-g mass. The point of force application on the hand was assumed to be the midpoint between the second and fifth metacarpals.

Variables of interest included the peak internal elbow adduction moment, which was identified by visual inspection of the entire pitching motion and normalized to participant height and mass to permit between-subject comparisons and peak PV. For both the peak elbow adduction moment and the peak PV, the value for each trial was recorded, and the average of the 10 trials was averaged and used for analysis. Statistical testing was performed with commercially available software (SPSS 15.0, Chicago, Illinois). Linear regression analysis was used to evaluate the impact of peak PV on the peak elbow adduction moment. Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe group characteristics. Statistical significance was established a priori at α ≤ 0.05.

Results

Mean participant age was 16 ± 1.1 years. The sample included 5 athletes aged 15 years, 9 who were 16 years old, 6 who were 17 years old, and 6 who were 18 years old.

Mean values for the group included a PV of 71 ± 6 mph and peak internal elbow adduction moment of 0.558 ± 0.099 Nm/Ht × mass.

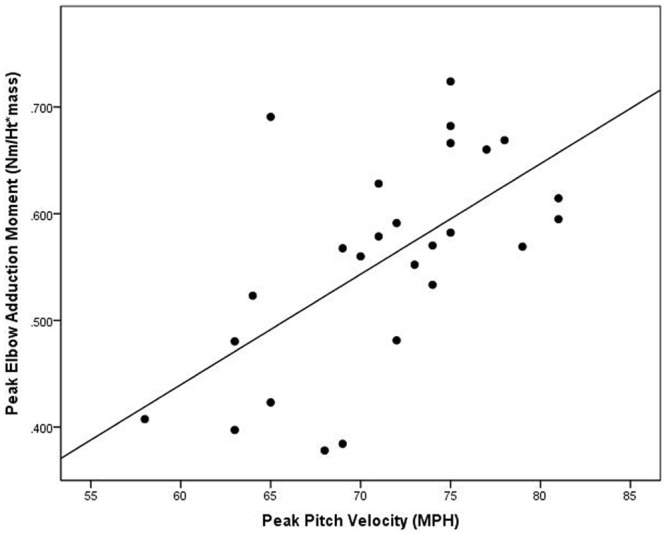

PV was a significant predictor of the peak elbow adduction moment (P < 0.01, R2 = 0.373) (Figure 2), as greater velocities were positively associated with higher moments.

Figure 2.

The influence of the peak pitch velocity on the peak elbow adduction moment (P < 0.01, R2 = 0.373).

Discussion

Consistent with our hypotheses, there was a very strong positive association between the PV and the peak elbow adduction moment. This finding suggests that individuals with greater throwing velocities may be more vulnerable to elbow injury, particularly of the UCL. This interpretation of the potential impact of PV on elbow injury risk is consistent with the work of Bushnell et al,2 who prospectively assessed maximum PV in 23 uninjured professional pitchers. The 9 individuals who subsequently sustained an elbow injury had a significantly greater PV (89 mph) than that of the uninjured (85 mph). This relationship may be explained, as PV and the medial elbow adduction moment are in part biomechanically correlated. The calculation of a joint moment is performed using inverse dynamics, which includes acceleration, or the derivative of velocity, of a limb segment.16 If the arm is moving faster to generate greater ball velocity, there will be a concomitant increase in the joint moments. The results from this study suggest that measuring PV may be useful in identifying individuals at risk for elbow injury and may be used as a surrogate for more expensive, time-consuming laboratory measures.

Although the ultimate goal is to prevent throwing arm injuries in this population, it is usually not reasonable to limit a pitcher’s throwing velocity. Results from this study may be useful, however, for enhancing current injury prevention guidelines. Currently, limiting the throwing volume is advocated as a critical injury prevention strategy in youth pitchers.6 The recommendation to limit the number of pitches thrown in a game, during a week, and over the course of the season is based on work by Lyman et al,11 who documented a relationship between throwing volume and arm pain in youth baseball pitchers. The rationale is that a greater volume of pitches thrown may contribute to microtrauma and lead to overuse injuries. The intensity of the load that the throwing limb is exposed to also has the potential to contribute to overuse injury by increasing tissue demands. For example, the pitcher who throws 100 pitches in a game with an average velocity of 83 mph would experience a greater volume of work compared with a pitcher throwing 100 pitches with an average velocity of 75 mph. These findings are in agreement with the work of Olsen et al,14 who surveyed 140 adolescent pitchers, including 95 who had previously sustained a shoulder or elbow injury and 45 who had never been injured. Olsen et al14 reported that a fastball PV greater than 85 mph increased the odds of a throwing-arm injury by 2.58 times. This is not the first suggestion to use PV as a marker of injury risk. Axe1 suggested that youth baseball athletes who throw faster and further than their peers are at increased risk for shoulder and elbow injury. Collectively, these results suggest that future injury prevention guidelines should incorporate throwing velocity to determine an appropriate pitch count.

There are limitations to this study. It is possible that there are additional characteristics of the pitching motion that may be meaningful contributors to PV and the elbow adduction moment that were not captured, including arm strength, range of motion, and alterations in the timing of muscle recruitment that may affect dynamic joint stability. Furthermore, individuals with very poor mechanics may experience high elbow adduction moments during pitching that we did not capture with this sample.

This study design incorporated a single testing session of uninjured athletes. Neither the repeatability of these laboratory measures nor the pitching mechanics of the study participants was evaluated to determine the magnitude of error of the measures of interest. It is also unknown if there is a threshold at which PV or the elbow adduction moment may be directly related to injury risk.

Conclusions

Pitchers with the greatest PV have greater medial elbow adduction moments. Joint moments are biomechanically related to PV, as arm velocity is a component of the moment calculation. Thus, talented youth pitchers may be at increased risk for elbow injury as a consequence of this biomechanical coupling. These results emphasize the importance of following existing guidelines, limiting pitch volume and type to minimize the effects of cumulative microtrauma in this population. Expanding pitch guidelines to include throwing velocity may be necessary to protect from future throwing-arm injury.

References

- 1. Axe MJ. Recommendations for protecting youth baseball pitchers. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2001;9:147-153 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bushnell BD, Anz AW, Noonan TJ, Torry MR, Hawkins RJ. Association of maximum pitch velocity and elbow injury in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(4):728-732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cain EL, Jr, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, et al. Outcome of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow in 1281 athletes: results in 743 athletes with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2426-2434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dempster W. Space Requirements of the Seated Operator. Wright-Patterson AFB, OH: Wright-Patterson Air Force Base; 1955 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Escamilla RF, Fleisig GS, Zheng N, Barrentine SW, Andrews JR. Kinematic comparisons of 1996 Olympic baseball pitchers. J Sports Sci. 2001;19(9):665-676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Cutter GR, et al. Risk of serious injury for young baseball pitchers: a 10-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):253-257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233-239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gummesson C, Ward MM, Atroshi I. The shortened disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hurd WJ, Kaufman KR, Murthy NS. Relationship between the medial elbow adduction moment during pitching and ulnar collateral ligament appearance during magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1233-1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaufman KR, An KN, Chao EY. A comparison of intersegmental joint dynamics to isokinetic dynamometer measurements. J Biomech. 1995;10:1243-1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lyman S, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Osinski ED. Effect of pitch type, pitch count, and pitching mechanics on risk of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(4):463-468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lyman S, Fleisig GS, Waterbor JW, et al. Longitudinal study of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(11):1803-1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morrow MM, Hurd WJ, Kaufman KR, An KN. Shoulder demands in manual wheelchair users across a spectrum of activities. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2010;20(1):61-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Olsen SJ, 2nd, Fleisig GS, Dun S, Loftice J, Andrews JR. Risk factors for shoulder and elbow injuries in adolescent baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(6):905-912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilk KE, Reinold MM, Andrews JR. Rehabilitation of the thrower’s elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23(4):765-801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Winter DA. In: Winter DA, ed. Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement. New York: Wiley & Sons, Inc:75-102 [Google Scholar]