Abstract

Context:

Ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) insufficiency of the elbow can be a debilitating injury that often prevents athletes from competing effectively. The overhead athlete is particularly susceptible to this injury because the anterior bundle of the UCL is the primary restraint to the valgus stress that is created during the throwing motion. Repetitive trauma from constant overhead or throwing activity can ultimately render the ligament incompetent and cause recurrent pain and instability.

Results:

The authors currently use a “docking” technique that provides excellent graft fixation and reduces ulnar nerve related complications.

Conclusions:

This article details the assessment of the throwing athlete with valgus instability secondary to UCL insufficiency and highlights the technical aspects for reconstruction. The majority of athletes who undergo UCL reconstruction of the elbow can successfully return to their preinjury function.

Strength-of-Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT):

A

Keywords: overhead athlete, ulnar collateral ligament, docking technique

The anterior bundle of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) of the elbow is the primary restraint to valgus load. It has been well documented that throwing athletes are prone to injury of this structure secondary to the repetitive valgus loads subjected to the elbow with overhead pitching.1-6 Originally described in javelin throwers, this injury is most commonly seen in overhead throwing athletes, with baseball pitchers being the most prevalent group of patients. Injury to the UCL has also been shown in wrestlers, tennis players, professional football players, and arm wrestlers. Symptomatic valgus instability can arise in these athletes after a UCL injury, thus necessitating operative intervention.1-6 Although injury to the UCL in the nonthrowing athlete can have excellent results with nonoperative intervention, the overhead throwing athlete may find an injury to the UCL of the elbow to be a career-ending event if surgical intervention is not employed.

Treatment Options

Athletes with partial tears or those with overlapping symptoms secondary to medial epicondylitis or ulnar nerve symptoms are initially treated conservatively with activity modification and a shoulder- and elbow-strengthening program. Few studies have evaluated nonoperative treatment of UCL injuries in throwing athletes. Rettig et al8 evaluated 31 throwing athletes that were treated nonoperatively and found that only 42% were able to return to their previous level of competition. Those who did return did so at an average of 24.5 weeks. Athletes with isolated complete tears and symptomatic instability are usually candidates for ligament reconstruction, and we rarely recommend nonoperative treatment for those patients. Generally, the indication for surgery is based on the patients’ subjective symptoms, mainly the inability to compete due to refractory medial elbow pain. Therefore, the decision to operate is not so much based on whether the tear is partial or complete or on timing of the season but more on the degree of symptoms and whether the athletes feel as though they can compete at their desired level. For those patients who are candidates for nonoperative management, we generally would recommend a rehabilitation period consisting of rest followed by a gradual strengthening program for a total of 3 months. After 3 months, a tossing program is initiated, following by mound progression for pitchers with a gradual return to play. Some physicians have advocated using platelet-rich plasma injections for treatment of partial UCL tears, but we do not have any experience with this.

In terms of surgery, reconstruction has clearly been shown to be superior to repair. Reconstruction options include the classic Jobe technique7 and other more recently described techniques, including the DANE TJ reconstruction, which uses hybrid fixation of the graft.4

Development Of The “Docking” Procedure

Early experience of UCL reconstruction led to some concerns about the original procedure as described by Jobe.7 These concerns included (1) the ability to adequately tension the graft at the time of final fixation, (2) potential complications from detachment of the flexor origin, (3) potential complications from the placement of 3 large drill holes in a limited area on the epicondyle, (4) complications from routine ulnar nerve transposition, and (5) the strength of suture fixation of the free tendon graft. Therefore in 1996, the senior author (DWA) began to look for alternative methods to reconstruct the UCL to address these concerns. The resulting procedure is referred to as the “docking” technique and highlights the following: (1) using a muscle-splitting “safe zone” approach,9 (2) avoiding routine transposition of the ulnar nerve, (3) reducing the number of large drill holes from 3 to 1 in the medial epicondyle, and (4) addressing tendon length to ensure proper tensioning and fixation in bony tunnels.

Anesthesia And Positioning

The procedure is generally performed under regional anesthesia. Some cases obviate the need for arthroscopic evaluation and treatment of certain intraarticular pathologies (loose bodies, posterior medial impingement). This is performed before the UCL reconstruction. With use of an arm holder, the humerus and forearm are positioned across the patient’s chest for the arthroscopic evaluation of the elbow. The supine position allows for easy conversion to the open UCL procedure once arthroscopy has been completed.

Surgical Technique

Once the arthroscopy has been completed, the arm is released from the arm holder when indicated and then placed on the hand table. In cases where the palmaris longus tendon is absent, the gracilis tendon is harvested at this time. Otherwise, the ipsilateral palmaris longus tendon is harvested through a 1-cm incision in the volar wrist flexion crease over the tendon. At the time of harvest, the visible portion of the tendon is tagged with a No. 1 Ethibond suture (Ethicon, Inc., Johnson & Johnson) in a Krackow fashion, and the remaining tendon is then harvested using a tendon stripper (Figures 1-3). The incision is then closed with interrupted nylon sutures, and the tendon is placed in a moist sponge on the back table

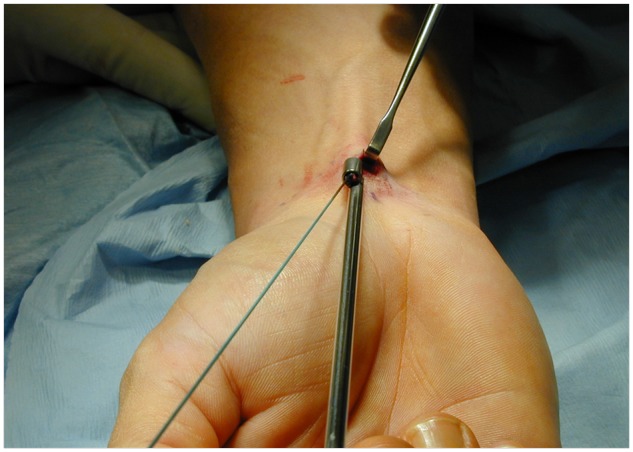

Figure 1.

When present, the palmaris longus is harvested for graft reconstruction. The visible portion of the tendon is tagged with a suture.

Figure 2.

A tendon stripper is used to harvest the remaining tendon once it has been identified and tagged.

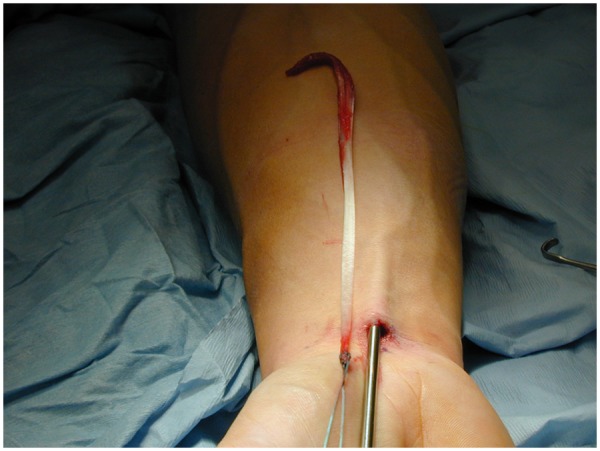

Figure 3.

Final picture demonstrating complete harvest of the Palmaris tendon.

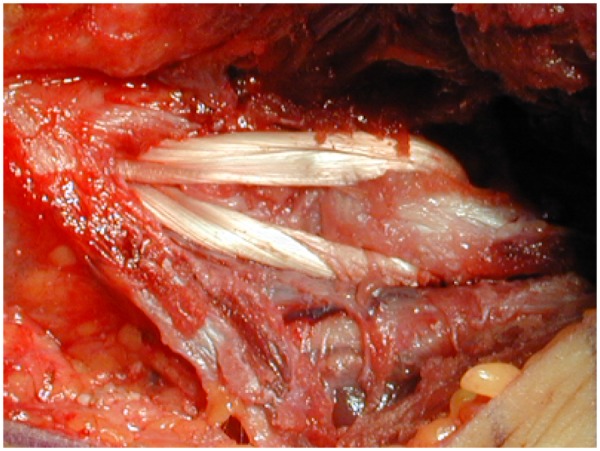

After the arm is exsanguinated to the level of the tourniquet, an 8- to 10-cm incision is created from the distal third of the intermuscular septum across the medial epicondyle to a point 2 cm beyond the sublime tubercle of the ulna. While the fascia of the flexor-pronator mass is exposed, care is taken to identify and preserve the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, which frequently crosses the operative field. A muscle-splitting approach is then utilized through the posterior one-third of the common flexor pronator mass within the most anterior fibers of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (Figure 4). This approach is beneficial because it utilizes a true internervous plane, allows for adequate exposure of the native UCL, and is less traumatic than detaching the entire flexor-pronator mass from its origin. The anterior bundle of the UCL is now incised longitudinally to expose the joint.

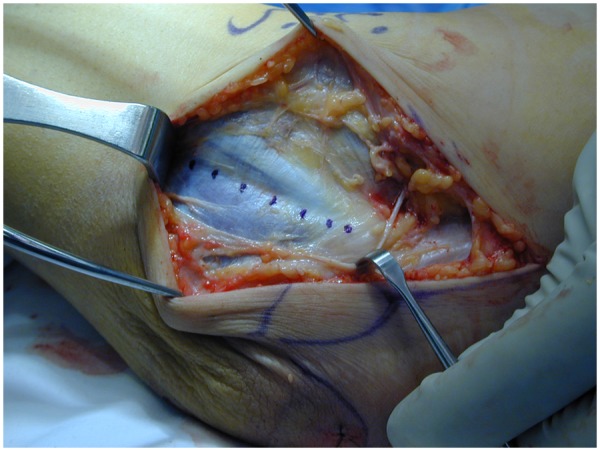

Figure 4.

A muscle-splitting approach is utilized through the posterior one third of the common flexor pronator mass within the most anterior fibers of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (dotted line).

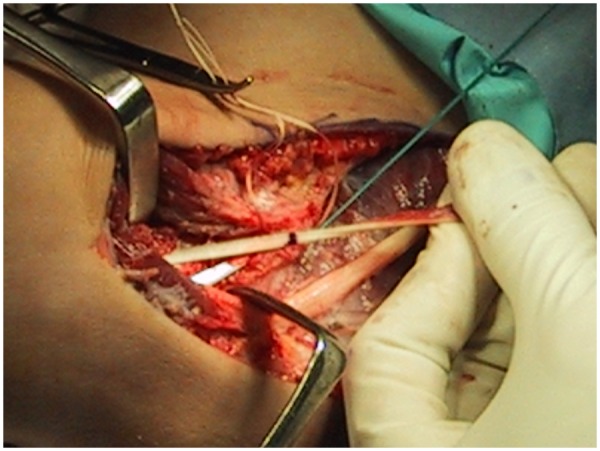

The tunnel positions for the ulna are exposed first. The posterior tunnel requires that the surgeon subperiosteally expose the ulna 4 to 5 mm posterior to the sublime tubercle while meticulously protecting the ulnar nerve (Figure 5). With use of a 3-mm burr, tunnels are made anterior and posterior to the sublime tubercle such that a 2-cm bridge exists between them. The tunnels are connected with a small, curved curette, with care not to violate the bony bridge. A suture passer is used to pass a looped suture through the tunnel. To expose the humeral tunnel position, the incision within the native UCL is extended proximally to the level of the epicondyle. A longitudinal tunnel is then created along the axis of the medial epicondyle with a 4-mm burr; care is taken not to violate the posterior cortex of the proximal epicondyle. The upper border of the epicondyle, just anterior to the intramuscular septum, is then exposed, and 2 small anterior exit punctures are made with a 1.5-mm burr. They should be approximately 5 mm to 1 cm apart from each other. Again, a suture passer is used from each of the 2 exit punctures to pass a looped suture, which will be used for graft passage. With the elbow reduced, the incision in the native UCL is repaired using a 2-0 absorbable suture.

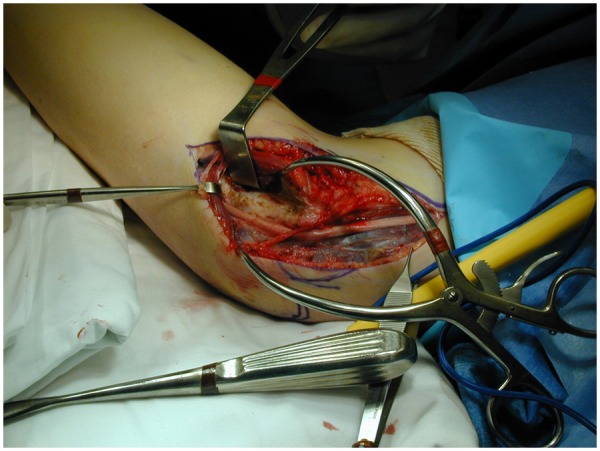

Figure 5.

The sublime tubercle is exposed subperiosteally in preparation for drilling ulnar tunnels.

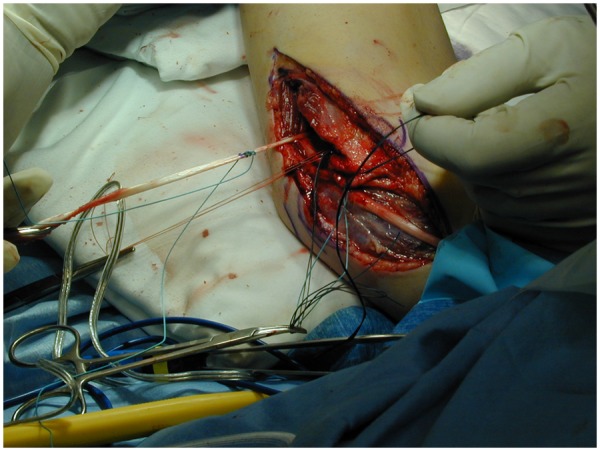

With the forearm supinated and a mild varus stress applied to the elbow, the graft is then passed through the ulnar tunnel anterior to posterior (Figure 6). The limb of the graft on which sutures have already been placed is then passed into the humeral tunnel with the sutures exiting one of the small humeral exit punctures. This first limb of the graft is now securely “docked” in the humerus. With the elbow reduced, the graft is tensioned by flexing and extending the elbow to take any creep out of the graft. Then, in approximately 30° of flexion, final graft length is determined by placing the second limb of the graft adjacent to the humeral tunnel. Final length is determined by referencing the graft to the exit hole in the humeral tunnel. This point is marked on the graft, and a No. 1 Ethibond suture is placed in a Krackow fashion (Figure 7). The excess graft is then excised immediately above the Krackow stitch, and this end of the graft is then docked securely in the humeral tunnel, with the sutures exiting the free exit puncture.

Figure 6.

The graft is passed through the ulnar tunnel anterior to posterior. The limb with sutures is ultimately docked into the humerus.

Figure 7.

Final length is determined by referencing the graft to the exit hole in the humeral tunnel. This point is marked on the graft, and a No. 1 Ethibond suture is placed in a Krackow fashion.

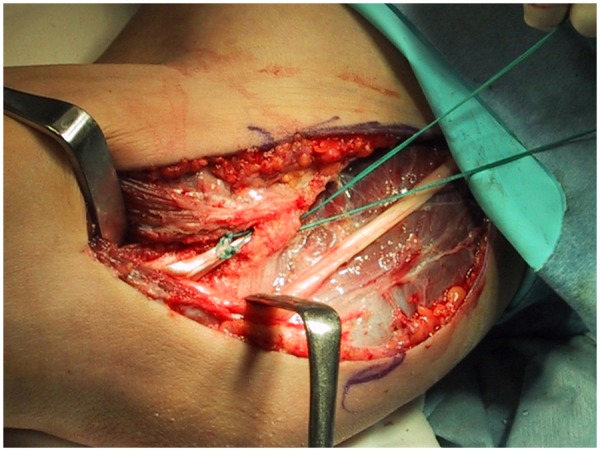

Final graft tensioning is performed by taking the elbow through a full range of motion. Once the surgeon is satisfied, the 2 sets of graft sutures are tied over the bony bridge on the humeral epicondyle (Figures 8 and 9). After the tourniquet is deflated and hemostasis achieved, an ulnar nerve transposition is performed, if indicated. This is performed only when the preoperative examination is consistent with ulnar neuritis. Otherwise, the fascia over the flexor pronator mass is reapproximated, and the remaining wound is closed in layers. The elbow is then placed in a plaster splint at 45° of flexion and neutral rotation with the hand and wrist free.

Figure 8.

Once both limbs of the graft have been successfully docked into the humeral tunnel, the graft sutures are tied down.

Figure 9.

Final photograph demonstrating the completed UCL reconstruction.

Postoperative Management

Immediately after surgery, the arm is placed in a plaster splint for approximately 1 week. At the first postoperative visit, the sutures are removed, and the elbow is placed in a hinged brace. Initially, motion is allowed only from 30° to 90° of flexion. In the third to fifth week, 15° to 105° of flexion is allowed. Wrist flexion of the contralateral limb is also encouraged if the palmaris longus was harvested from that forearm. At 6 weeks, the brace is discontinued, and formal physical therapy is begun, which focuses on shoulder and forearm strengthening as well as elbow range of motion. By 12 weeks, the patient is advanced to an aggressive physical therapy program, which includes trunk strengthening as well as shoulder and scapula strengthening. A formal tossing program is begun at 16 weeks. Initially, throwing starts at a distance of 45 ft (13.7 m) and is advanced at regular stages. If pain occurs during any stage, the patient is instructed to back up to the previous stage of therapy. If at 9 months the patient can throw pain free from 180 ft (54.9 m), he or she is allowed to begin pitching from a mound. Competitive pitching is generally discouraged until 1 year postoperatively.

The most common postoperative complications are medial forearm numbness secondary to injury to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and ulnar neuropathy. Fortunately, both issues are typically traction injuries related to retractor placement and usually resolve on their own. Much less common is fracture at the sublime tubercle or medial epicondyle secondary to inadequate spacing of tunnel placement.

Results

Conway et al3 conducted the first outcome study on the original procedure, as described by Jobe, which included detachment of the flexor-pronator mass and routine transposition of the ulnar nerve. Only 68% of the athletes in that series were able to return to either their previous level of competition or one higher. In addition, 21% of the patients developed postoperative ulnar nerve neuropathies.

Thompson et al10 were the first to report on 83 athletes who underwent UCL reconstruction based on a muscle-splitting approach without transposition of the ulnar nerve. Of these 83 patients, 33 were followed for at least 2 years. The surgical result was excellent in 27 of 33 patients (82%), good in 4 (12%), and fair in 2 (6%). These results improved to 93% excellent when those patients who had had a prior procedure were excluded. Several authors have since reported on UCL reconstruction using a muscle-splitting approach or transposing the ulnar nerve subcutaneously and noted lower ulnar nerve-related complication rates ranging from 8% to 9%.1,4,5,10

We have reported on 100 consecutive UCL reconstructions based on the docking technique with an average follow-up of 3 years.5 No patients were lost to follow-up. Ninety of 100 patients (90%) returned to or exceeded their previous level of competition for at least 1 year, meeting the Conway-Jobe classification criteria of “excellent.” Additionally, 7 patients had a good result, which means that they were able to compete at a lower level for at least 12 months. Two patients (2%) had poor results and were not able to return to throwing. Other authors have also reported excellent results using both the docking and Jobe techniques.1,10

In this series, 22% of patients underwent a subcutaneous transposition with fascial sling at the time of surgery. None of these patients suffered postoperative complications. Two athletes (2%) required transposition postoperatively after they had returned to throwing for at least 1 year; neither had preoperative symptoms, and both had excellent results at the time of follow-up.

We sometimes find it necessary to perform an arthroscopic evaluation both anteriorly and posteriorly for patients prior to reconstruction. It is not unusual for this patient group to develop intra-articular pathology secondary to valgus extension overload. In this series, 45 of 100 patients (45%) had associated intraarticular pathology that were all managed arthroscopically just before reconstruction.5 Of these patients, detection of the lesions on preoperative imaging studies occurred in only 25 of the 45 cases. Without arthroscopy, a posterior arthrotomy is necessary to treat such pathology that necessitates transposition of the ulnar nerve. Arthroscopy is a minimally invasive approach and has the added benefit of avoiding obligatory transposition of the nerve.

Summary

The modifications in the docking technique have resulted in excellent outcomes for athletes at all levels of play and have proven to be a minimally invasive and reliable method of reconstruction of the UCL.

References

- 1. Cain EL, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, et al. Outcome of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow in 1281 athletes: results in 743 athletes with minimum 2 year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2426-2434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Callaway GH, Field LD, Deng XH, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of the medial collateral ligament of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79(8):1223-1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Conway JE, Jobe FW, Glousman RE, Pink M. Medial instability of the elbow in throwing athletes. Treatment by repair or reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(1):67-83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dines JS, ElAttrache NS, Conway JE, et al. Clinical outcomes of the DANE TJ technique to treat ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(12):2039-2044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dodson CC, Thomas A, Dines JS, et al. Medial collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow in throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(12):1926-1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Field LD, Callaway GH, O’Brien SJ, Altchek DW. Arthroscopic assessment of the medial collateral ligament complex of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(4):396-400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jobe FW, Stark H, Lombardo SJ. Reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(8):1158-1163 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rettig AC, Sherrill C, Snead DS, et al. Nonoperative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries in throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(1):15-17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith GR, Altchek DW, Pagnani MJ, Keeley JR. A muscle-splitting approach to the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow. Neuroanatomy and operative technique. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(5):575-580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thompson WH, Jobe FW, Yocum LA, Pink MM. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in athletes: muscle-splitting approach without transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(2):152-157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]