Abstract:

Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) genetically modified to express T cell receptors (TCR) specific to known melanoma antigens, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells-1 (MART-1), and gp100 can elicit objective tumor regression when administered to patients with metastatic melanoma. It has also been demonstrated that modifications within the constant regions of a fully human TCR can enhance surface expression and stability without altering antigen specificity. In this study, we evaluated the substitution of murine constant regions for their human counterpart within the DMF5 MART-1-specific TCR. Unlike previous studies, all modified TCRs were inserted into retroviral vectors and analyzed for expression and function following a clinical transduction protocol. PBL were transduced with retroviral supernatant generated from stable packaging lines encoding melanoma-specific TCRs. This protocol resulted in high levels of antigen-specific T cells without the need for additional peptide stimulation and selection. Both the human and murinized TCR efficiently transduced PBL; however, the murinized TCR exhibited significantly higher tetramer binding, mean fluorescence intensity, as well as, increased in vitro effector function following our clinical transduction and expansion protocol. Additional TCR modifications including insertion of a second disulfide bond or the linker modifications evaluated herein did not significantly enhance TCR expression or subsequent in vitro effector function. We conclude that the substitution of a human constant region with a murine constant region was sufficient to increase receptor expression and tetramer binding as well as antitumor activity of the DMF5 TCR and could be a tool to augment other antigen-specific TCR.

Keywords: Melanoma, MART-1, T cell receptor, Retrovirus, Gene therapy, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Currently patients with metastatic melanoma have few curative options for therapy, as standard chemotherapy typically induces only transient beneficial responses. Immunotherapy in the form of high-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) can induce durable complete responses, but only in a small percentage of patients [1, 2]. Adoptive cell transfer (ACT) with autologous tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) has shown promise in phases I and II clinical trials, obtaining response rates of 49–72%, with many durable long-term survivors [3–5]. However, there are patients for whom TIL ACT is not a viable option: those without tumors that are easily resectable; those from whom TIL cannot be successfully cultured and expanded in vitro; and those whose TIL do not exhibit robust, specific effector function. As an alternative to TIL ACT, we and others have successfully redirected non-reactive autologous peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) using T cell receptor (TCR) gene transfer to mediate antigen-specific tumor reactivity [6–10]. In a clinical trial, Morgan et al. [11] reported that a MART-1-specific TCR (DMF4), isolated and cloned from the TIL of a responding patient, resulted in a 13% objective response rate when introduced into non-reactive PBL from different melanoma patients via retroviral transduction. In a separate, but related effort, a high avidity TCR (DMF5) was cloned that also recognized MART-1, and when expressed in patient PBL conferred enhanced tetramer binding and functional activity as measured by interferon-γ (IFNγ) release and cytotoxicity, and when evaluated in a phase II trial, the response rate was 30% by RECIST criteria [12, 13]. These data suggest that increased TCR avidity may enhance tumor recognition and provide a more effective therapy; however, with an objective response rate below that of TIL therapy, additional improvements to ACT using genetically modified T cells are needed.

Several investigators have described methods for improving the surface expression and effector function of transduced TCR by introducing a variety of genetic modifications, such as addition of murine sequences and cysteine substitutions into the coding regions of the human TCR α- and β-chain constant regions [14–18]. It was reported that replacement of the entire human constant region or select residues of this region with its murine counterpart resulted in enhanced antitumor activity and improved pairing between α and β chains of the exogenous TCR [15, 19]. In addition, modifications to introduce a second disulfide bond within the TCR constant region also resulted in enhanced antitumor activity presumably due to improved pairing [16]. However, the bulk of the published literature evaluates TCR function following RNA electroporation or retroviral co-transduction with individual vectors encoding the TCR α and β chains, respectively. Both methods result in relatively low levels of TCR expression making it difficult to evaluate differences attributable to these receptor modifications. Recently, PBL were co-transduced with separate vectors encoding the human TCR α and β chains to generate a TCR directed against Wilms tumor antigen 1 (WT-1) [17]. The WT-1 TCR was then modified to improve pairing between the TCR α and β chains by either the addition of a cysteine residue to create a second disulfide bond or replacement of the human constant region with its’ murine counterpart. Based on tetramer staining, the proportion of tetramer-positive T cells was low for all the WT-1 TCR tested, therefore, repeated antigen-specific peptide stimulation was required to increase the number of antigen-specific T cells. Importantly, following multiple rounds of peptide stimulation, neither the addition of a second disulfide bond within the constant region of the WT-1 wild-type TCR nor replacement of the human constant region with that of murine origin was found to confer improved function on these cells. Interestingly, only T cells transduced with TCRs modified to improve pairing were able to bind significant levels of WT-1 tetramer following peptide stimulation. However, while the wild-type TCR could not efficiently bind tetramer based on FACS analysis, it was functionally equivalent to the modified TCR populations as measured by IFNγ release and cytotoxicity. These findings suggest that tetramer binding and TCR avidity or antitumor reactivity are not directly correlated implying that TCR modifications to improve pairing can enhance tetramer binding, but may not confer a functional advantage to the modified T cells.

Based on these findings, the series of experiments described herein were carried out to evaluate the effects of modification of the constant regions of the DMF5 HLA-A2-restricted MART-1-specific TCR. Using clinical grade, high-titer retroviral supernatant generated by stable packaging clones, TCR transductions yielded a high proportion (typically >50%) of antigen-specific tetramer-positive T cells, abrogating the need for additional peptide stimulation [9, 20, 21]. To directly compare differences between TCR expression and function, wild type and modified TCR were transduced into the same patient PBL and evaluated prior to and following our clinical rapid expansion protocol (REP) which involves non-specific TCR activation with a soluble anti-CD3 antibody and the use of irradiated peripheral blood monocyte (PBMC) feeders [22]. The addition of a cysteine residue to promote formation of a second disulfide bond, the substitution of a murine constant region and the introduction of an optimized linker sequence between the α and β chain coding regions were each evaluated for their ability to enhance the antitumor activity of gene modified T cells [23]. Under REP conditions, where the majority of TCR-transduced PBL are tetramer positive, we found that a chimeric murine-human TCR conferred enhanced TCR expression and antitumor reactivity in comparison to the wild-type TCR.

Materials and methods

Patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells and cell lines

Melanoma cell lines HLA-A2+/MART-1+ (526, 624, and 624.38) and HLA-A2− (888 and 938) were isolated from surgically resected metastases as previously described [24] and were cultured in R10 medium consisting of RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone, Logan, UT). All peripheral blood mononuclear cells and lymphocytes used for transduction and as feeder cells were obtained from aphereses of Surgery Branch, NCI patients on IRB-approved protocols and cultured in AIM-V medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% human AB serum (Valley Biomedical, Winchester, VA), β-mercaptoethanol, non-essential amino acids, HEPES and l-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

DMF5 vector modifications

To create the Mur-F5-cys, plasmid DNA (pMSGV1-F5 M-A2aB) encoding the Mur-F5 retroviral vector was modified using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The α chain was amplified using a 5′-specific primer, GGAACGTTCATCACTGACAAATGCGTGCTGGACATGAAAGCTA and 3′-αcysrev primer, TAGCTTTCATGTCCAGCACGCATTTGTCAGTGATGAACGTTCC. The β-chain was amplified using a 5′-specific primer, GGGGTCCACAGTGGGGTCTGCACGGACCCTCAGGCCTACA and 3′-βcysrev primer, TGTAGGCCTGAGGGTCCGTGCAGACCCCACTGTGGACCTCC (mutated bases are underlined). Insertion of an optimized linker sequence between the α and β chains of Mur-F5 and Mur-F5-cys was done using two-step overlapping PCR using pMSGV1-F5M-A2aB and pGEM-F5MAcys and pGEM-F5MBcys as templates, respectively. Initially, the α chains were amplified with a 5′-specific primer engineered to add a PciI restriction enzyme cleavage site 5′ to the start codon, CCCCACATGTATGGAAATCCTTGGAGTTTTAC and a 3′-specific primer engineered to add the first 60 bp of the optimized linker sequence 3′ to the constant region coding sequence, CCGGCCTGCTTCAGCAGGCTGAAGTTGGTGGCTCCGGATCCGGACCGCTTGGCCCGTCAACTGGACCACAGCCTCAGCGT. The β-chains were amplified with a 5′-specific primer engineered to add the terminal 60 bp of the optimized linker sequence 5′ to the start codon, CCACCAACTTCAGCCTGCTGAAGCAGGCCGGCGACGTGGAGGAGAACCCCGGCCCCATGAGAATCAGGCTCCTGTGCTGT and a 3′-specific primer engineered to add a SalI restriction site 3′ to the constant region coding sequence, CCCCGTCGACTCATGAATTCTTTCTTTTGACCATAG. The resulting overlap of 20 bp centrally located in the linker sequence allowed a second amplification with the α and β PCR products, using the 5′ PciI primer and 3′SalI primer described above. Directional cloning was performed using PciI and SalI digest of the new constructs, compatible with NcoI and XhoI digest of an MSGV1 backbone. All PCR products were gel purified (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and final constructs were fully sequenced for verification (Macrogen, Rockville, MD, USA). 293T cells were transiently transfected and retroviral supernatant was harvested after 48 h.

Retroviral supernatant

Clinical grade gamma-retroviral vector supernatant encoding the DMF5 TCR (WT-F5) was produced at the Indiana University Vector Production Facility (Indianapolis, IN). Clinical grade retroviral supernatant encoding the murinized DMF5 receptor (Mur-F5) was produced at the Surgery Branch Vector Production Facility (NCI, Bethesda, MD). Briefly, a human ecotropic cell line, Phoenix ECO (kindly provided by Dr. Gary Nolan, Stanford University, Stanford, CA), was transfected with WT- or Mur-F5 plasmid in the presence of lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The transiently generated retroviral supernatant was used to transduce the PG13 (ATCC CRL-10686) gibbon ape leukemia virus packaging cell line. High-titer clones were identified by RNA dot blot, and following PBL transduction, cytokine release assays were used to select the final packaging clones. The selected packaging clones were then used to generate retroviral vector supernatant as described previously with only slight modifications [20]. Briefly, following supernatant harvest, the product was clarified by “modified” step-filtration in which the 20-μm filter was omitted from the clarification process. For transduction experiments, supernatant was diluted with D10 medium consisting of high-glucose (4.5 g/L), Dulbecco’s modified essential medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone, Logan, UT) and a final concentration of 6 mM glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

PBL transduction

For virus titer determinations, PBL (2 × 106 cell/mL) were stimulated with IL-2 (300 IU/mL) and OKT3 (50 ng/mL) on Day 0. Non-tissue culture treated 6-well plates were coated with retronectin (Takara Bio, Otsu, Shiga, Japan) at 10 μg/mL, 2 mL/well on day 1 and stored overnight at 4°C. Serial dilutions of vector supernatant (4 mL/well, diluted with D10) were applied to plates on day 2 followed by centrifugation at 2,000×g for 2 h at 32°C. Half the volume was aspirated and PBL were added (0.25–0.5 × 106 cell/mL, 4 mL/well), centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000×g followed by incubation at 37°C/5% CO2. Vector titers were calculated as follows: [(percentage of tetramer-positive cells × total cell number × dilution factor)]/supernatant volume. For the clinical transduction protocol, a second transduction on day 3 was performed as described above. Cells were maintained in culture at 0.7–1.0 × 106 cell/mL. After harvest of one time stimulated cells for testing (S1d8-11), cells were rapidly expanded (REP) in the presence of soluble OKT3 (300 IU/mL), IL-2 (6,000 IU/mL) and irradiated feeders as previously described [22]. After day 5 of REP, cells were maintained in culture at 0.7–1.0 × 106 cell/mL until harvested for testing on days 7–10 (R2d7–10).

FACS analysis

Receptor expression was analyzed using PE-conjugated HLA*A201/MART-1:27-35L peptide tetramer (Beckman-Coulter, San Jose, CA) in combination with APC-, PE-Cy7-, and APC-Cy7-conjugated antibodies directed at human CD3, CD4 and/or CD8 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Phenotype analysis was performed as above with the addition of antibodies directed at CD62L, CD45RO, CD27, CD69 (all APC-conjugated) and CD45RA, CCR7, CD28, and CD70 (FITC-conjugated). (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA; except αCCR7, Ebioscience, San Diego, CA). Isotype controls followed manufacturer’s recommendations. Immunofluorescence analyzed as relative log fluorescence of live cells was measured using a FACSCantoII flow cytometer (Becton–Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Cells were stained in FACS buffer containing PBS, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, and 0.02% sodium azide.

Cytokine release assays

TCR-transduced effector cells (1 × 105) and melanoma cell lines (1 × 105) were placed in overnight co-culture (200 μL) at 37°C/5% CO2. Supernatants were harvested for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect IFNγ (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA). IL-2 assays were carried out as described above with the addition of α-IL-2R monoclonal antibody at 5 μg/mL. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed for presence of IL-2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

51Cr release assay

The ability of TCR-transduced PBL to lyse targets was measured using a 51Cr release assay as described [12]. Briefly, decreasing ratios of effector and 51Cr-labeled target cells (E:T) were co-incubated in R10 medium in 96-well plates for 4 h at 37°C. Percent lysis was measured by the 51Cr release into the medium: percentage lysis = (sample release − minimum release)/(maximum release − minimum release) × 100. Duplicate samples were averaged. Specificity controls include untransduced (UT) S1 and R2 PBL, as well as, TCR-transduced PBL targeting mel624 (HLA-A2+/MART-1+) and mel938 (HLA-A2−) target cell lines.

Statistical analysis

The results of cytokine secretion were compared using a paired Student’s t test. P values are two-tailed and indicated in the figures. The results of TCR modifications were compared using a one-way analysis of variance.

Results

A murine-human hybrid MART-1 specific TCR enhanced receptor expression in TCR-transduced human PBL

A retrovirally encoded TCR was created in which the original human constant regions of the MART-1 specific DMF5 TCR isolated from a patient’s TIL (referred to as WT-F5) were replaced by mouse sequences to generate a hybrid, murinized TCR (referred to as Mur-F5, Fig. 1). Plasmids encoding each receptor were used to generate stable packaging clones and clinical grade retroviral supernatant was used for TCR transduction of PBL. The titers for both WT-F5 and Mur-F5 were nearly identical, 1.46 ± 0.22 × 106 and 1.52 ± 0.16 × 106 transducing units (TU)/mL, respectively. PBL transductions consisted of spinoculation on two consecutive days with cells maintained in culture for approximately one additional week before undergoing a REP. Cells sampled prior to the REP were designated S1, denoting a stimulation and one exposure to OKT3; cells sampled after expansion were designated R2, denoting a REP and a second exposure to OKT3. To prevent assay variability in pairwise comparisons, all relevant samples for a single patient (untransduced, S1 WT-F5, S1 Mur-F5, R2 WT-F5, and R2 Mur-F5) were analyzed in the same experiment.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of gammaretroviral vectors encoding DMF5 TCR modifications. The DMF5 (WT-F5) TCR was cloned into the pMSGV1 gammaretroviral backbone. The modified TCR containing murine constant regions (denoted by the gray shaded box) was designated Mur-F5. The 2A sequences are derived from foot and mouth disease virus (F2A) and Turkey rhinotracheitis virus (T2A)

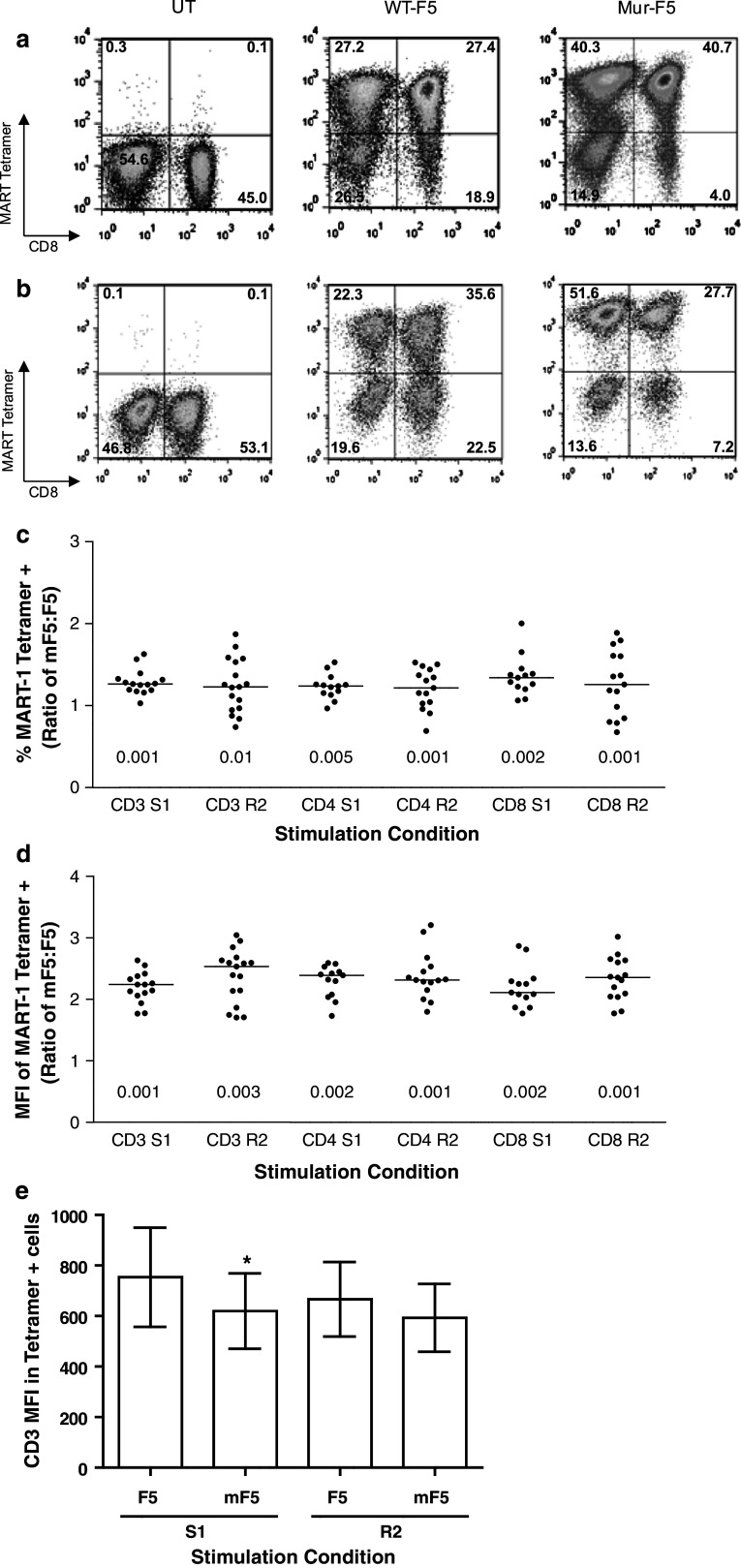

After stimulation and transduction with either the WT-F5 or Mur-F5 TCR, Mur-F5-transduced PBL yielded a significantly higher percentage of T cells capable of binding MART-1-specific tetramer, a surrogate for TCR expression and transduction efficiency. In a representative experiment, PBL transduced with the Mur-F5 TCR bound higher levels of tetramer as compared to WT-F5, 74 and 57%, respectively (Fig. 2a). In addition, the tetramer positive, Mur-F5 transduced cells had a visibly higher mean fluorescence intensity as compared to WT-F5 [mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), 1372 and 521, respectively, Fig. 2a] indicating increased expression of the Mur-F5 TCR on a per-cell basis. After a REP, the Mur-F5-transduced cells continued to exhibit enhanced tetramer binding (77 and 61%, respectively) as well as a significantly higher MFI than WT-F5 (1,866 and 696, respectively, Fig. 2b). In six independent experiments, the murinized form of the receptor exhibited a significant increase in the number of tetramer-positive cells in the bulk CD3+ population, as well as, the CD4+ and CD8+ subpopulations (p ≤ 0.05 for all pairs, Fig. 2c). The MFI of the Mur-F5 tetramer-positive cells was approximately twofold higher than the MFI of the WT-F5 transduced PBL (Fig. 2d). The MFI of the tetramer-positive Mur-F5-transduced PBL for the CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations following S1 or R2 was significantly higher than the corresponding WT-F5 groups (Fig. 2d, p ≤ 0.001). The enhanced tetramer binding and the higher MFI of the cells expressing the hybrid receptor were not patient-specific phenomena and were seen in at least nine different patients’ PBL in six independent experiments. Interestingly, while the CD3 MFI was significantly higher in the F5 S1 cells (p = 0.04), there was no difference in CD3 expression between the Mur-F5 and F5 TCR-transduced PBL following a REP (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of TCR expression and tetramer binding following transduction with gammaretroviral vectors encoding the WT-F5 or Mur-F5 TCR. Bulk human PBL were transduced with WT-F5 or Mur-F5 retroviral supernatant and placed into culture with media containing low doses of IL-2. No additional specific stimulation was performed. A representative FACS analysis of TCR-transduced PBL under a S1 and b R2 conditions for the respective TCR (gated on CD3+/CD8+/MART-1 tetramer+ cells). c Percent tetramer expression in Mur-F5 TCR-transduced PBL relative to wild-type, expressed as mean ± SEM. All S1 p < 0.001, R2 CD3 p = 0.006, CD4 p = 0.0052, CD8 p = 0.0272. d Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of the MART-1 tetramer signal as a measure of surface expression in Mur-F5 TCR-transduced PBL relative to wild type, expressed as mean ± SEM. All p < 0.001. e CD3 MFI of the S1 and R2 CD3+/MART-1 tetramer+ cells (*p ≤ 0.05). The results of at least six independent experiments

A murine-human hybrid MART-1 specific TCR enhanced antitumor activity following a rapid expansion

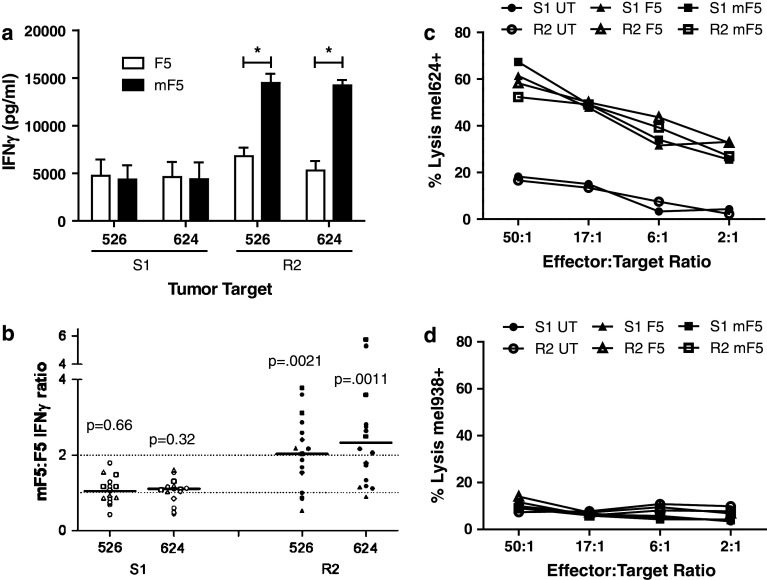

TCR-transduced PBL expressing WT-F5 or Mur-F5 were maintained in culture for 7–9 days before being placed into a REP. S1 and R2 cells were sampled and tested in the same assay for each group of patients. In a representative experiment, no significant functional differences were observed between the two receptors in S1 cells tested on day 8, however, significantly more IFNγ was released by R2 cells expressing the murinized receptor tested 7 days after the REP (Fig. 3a). There was substantial patient-to-patient variability within both the S1 and R2 groups; however, the R2 Mur-F5 cells consistently released an average of twofold more IFNγ when compared with S1 cells assayed at the same time from the same patient (Fig. 3b). The WT-F5 and Mur-F5 transduced cells were also analyzed for antigen-specific cytolytic function. TCR-transduced PBL were able to specifically lyse HLA-A2+/MART-1+ targets (Fig. 3c), but did not lyse HLA-A2− targets (Fig. 3d); however no significant differences were observed between the WT-F5 and Mur-F5 TCR-transduced PBL following S1 or R2. In addition, no significant differences in IL-2 secretion were observed between the WT-F5 and Mur-F5 TCR-transduced PBL following S1 or R2 (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

In vitro functional analysis of TCR-transduced PBL following an initial stimulation (S1) or a rapid expansion (R2). Bulk human PBL were transduced with WT-F5 or Mur-F5 retroviral supernatant and placed into culture with media containing low doses of IL-2. S1 cells were sampled 7–9 days after initial OKT3 stimulation. R2 cells were sampled 7–10 days after rapid expansion with high-dose IL-2, OKT3 and irradiated allogeneic feeders. a A representative assay showing IFNγ release following overnight co-culture with HLA-A2+/MART-1+ tumor targets (*p < 0.01). Data shown are from the PBL of three separate patients. Cells released no IFNγ against HLA-mismatched controls (data not shown). b The IFNγ ratio of Mur-F5:WT-F5 for S1 and R2 cell populations following overnight co-culture with HLA-A2+/MART-1+ tumor cell lines. Mur-F5 transduced cells released a median 2.2-fold more IFNγ (range 0.5–5.8). HLA-mismatched lines showed no specific release of IFNγ (data not shown), p values are indicated for both S1 and R2 for the given target cell line with the results from at least six independent experiments. S1 and R2 cells were evaluated for their ability to lyse c HLA-A2+/MART-1+ (mel624) or d HLA-A2− (mel938) targets at decreasing ratios of effector to target (E:T) ratios. Data shown is from the PBL of three separate patients. No significant differences were observed between both S1 and R2 or F5 and mF5 TCR-transduced cells within or between groups

T cell differentiation markers on WT- and Mur-F5 transduced T cells

In an effort to determine if the differentiation state of the T lymphocyte can affect TCR expression or downstream cell function, phenotypic analysis was performed to look for differential expression of known markers of cell differentiation. We examined both S1 and R2 WT- and Mur-F5 TCR-transduced PBL, respectively. The phenotypic analysis was based on nomenclature adopted by Foster and others who defined the major differentiation subsets on the basis of CD45RA and CD62L expression with double positives identified as naïve cells [25–27].

PBL transduced with either the WT-F5 or the Mur-F5 TCR gated on CD3+/MART-1 tetramer+ cells showed similar surface marker expression with a large naïve-like population of CD45RA+/CD62L+ T cells after the initial stimulation (S1, Fig. 4a). Both TCR also yielded similar levels of central memory-like (CD45RA−/CD62L+) and effector memory-like (CD45RA−/CD62L−) T cells. As described earlier, differences in receptor expression and effector function were not seen until after a REP (Figs. 2, 3). Following a REP, the naïve-like population in both the WT-F5 and Mur-F5 TCR-transduced PBL, was no longer present (Fig. 4b). In addition, there appears to be a greater proportion of central memory-like cells (CD45RA−/CD62L+) in the Mur-F5 TCR-transduced cells following a REP (37.5 and 17.5%, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Assessment of phenotypic markers of differentiation on WT-F5 and Mur-F5-transduced PBL following and initial stimulation (S1) or a rapid expansion (R2). There were no phenotypic differences between cells transduced with either the WT- or Mur-F5 TCR retroviral vector. However, there were distinct differences between S1 and R2 cells within a given transduced population. All plots are gated on CD3+/CD8+/MART-1 tetramer+ cells, representative of six patients. a S1 cells in both WT- and Mur-F5 cells had a sizeable CD45RA+/CD62L+ (or T naïve-like population). b After rapid expansion the T naïve-like population was no longer discernible with the majority of cells expressing a central memory (CD45RA−/CD62L+) or effector-like (CD45RA−/CD62L−) phenotype. The T cell subsets are described as follows: T N naïve, T CM central memory, T EM effector memory, T T terminally differentiated

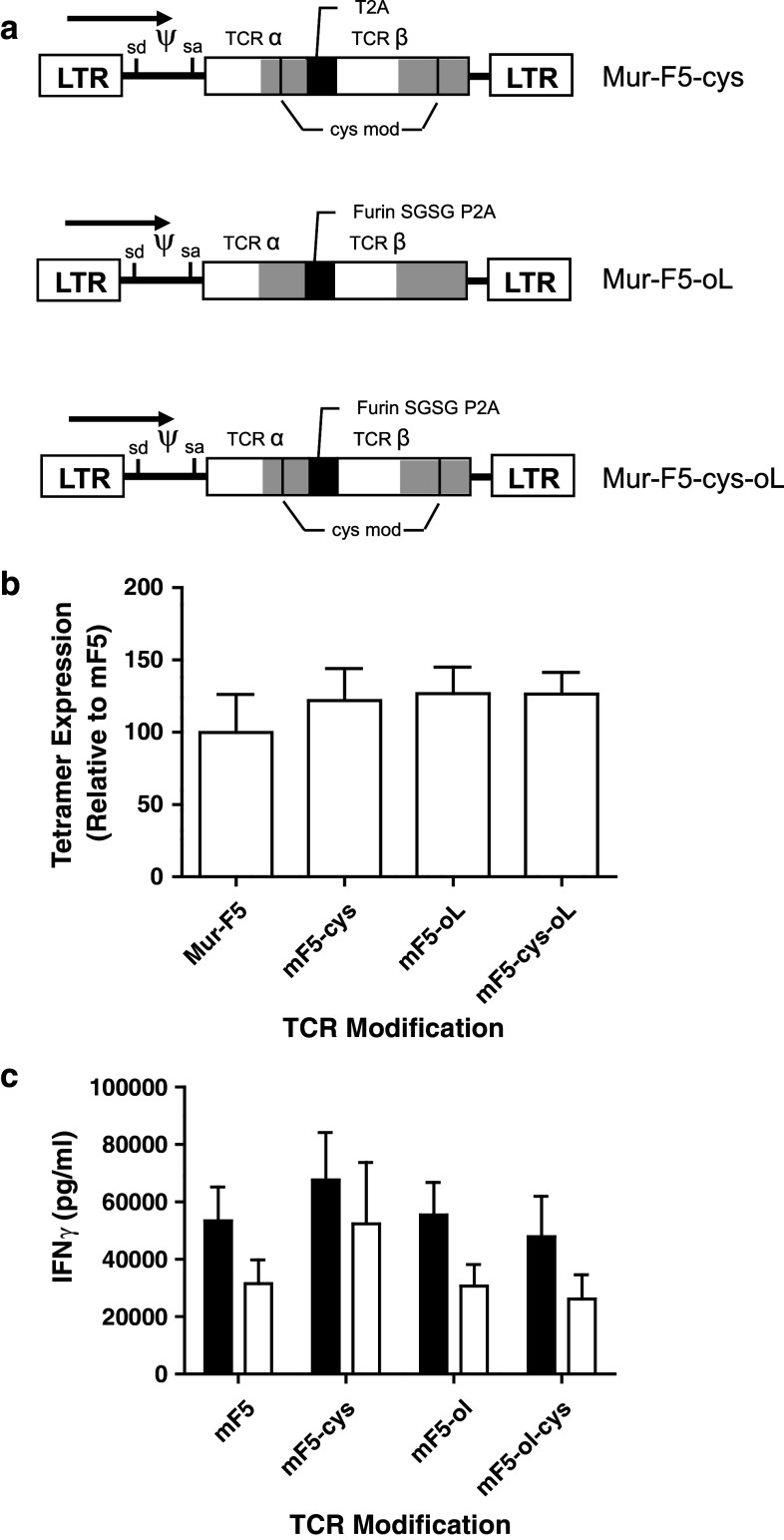

Vector modifications to the Mur-F5 did not further enhance TCR expression or function

Given the increased function of R2 cells transduced with the Mur-F5 TCR, we explored the use of additional vector modifications to further enhance the tetramer binding and, more importantly, effector function of the TCR-transduced PBL. Using previously described techniques [16–18, 28, 29], the Mur-F5 TCR was modified to promote a second disulfide bond between the constant regions of the α and β chains. In addition, an optimized intrachain linker sequence consisting of a furin cleavage site followed by an SGSG spacer and a P2A linker (furin SGSGP2A) was inserted into the original Mur-F5 and into the cysteine-modified Mur-F5 (Fig. 5a) [23]. The addition of a second disulfide bond alone or in combination with the optimized linker sequence resulted in slightly higher levels of tetramer binding as compared to Mur-F5 (Fig. 5b). However, the data demonstrated that neither the formation of a second disulfide bond in the constant region of the modified TCR nor the linker optimization provided any significant functional benefit as all TCR-transduced cell populations secreted similar levels of IFNγ (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of modifications to the high avidity wild-type DMF5 TCR following a REP. PBL were transduced with a gammaretroviral vector encoding the indicated TCR construct. a TCR modifications indicating the location of cysteine residues and substitution of the T2A linker for the optimized furinSGSGP2A linker are indicated. The P2A sequence was derived from the porcine teschovirus. b Tetramer expression relative to the mF5 TCR of transduced PBL 7 days post-REP as described. c IFNγ release of R2 cells relative to mF5, not normalized for tetramer expression. Cells released no IFNγ against antigen negative, HLA mis-matched controls (data not shown). Data representative of at least three independent experiments (one-way ANOVA, p > 0.05)

Discussion

We have described previously, efforts to improve the pairing and subsequent function of a MART-1 reactive TCR by the creation of a murine-hybrid TCR, as well as, the addition of a second disulfide bond within the constant region of the TCR [15, 16]. While most of the initial studies introduced TCR α and β chains via RNA electroporation, we sought to evaluate two MART-1-specific TCR (WT-F5 and Mur-F5) that share the same variable region sequences and differ only in the constant regions of the TCR, using clinical grade retroviral vectors of equivalent titers in a clinical transduction protocol. This approach generates highly transduced PBL which enables us to compare TCR expression and function without the need for multiple rounds of in vitro stimulation. A significant increase in both TCR expression, based on MFI, and tetramer binding was observed in both the Mur-F5 S1 and R2 cell populations (Fig. 2). In addition, following the REP Mur-F5 TCR-transduced PBL demonstrated significantly improved function as measured by IFNγ release (Fig. 3). There was no increase in the CD3 MFI following the REP indicating that the overall level of TCR expression was the same for both the WT-F5 and Mur-F5 TCR-transduced PBL. Because the WT-F5 and Mur-F5 TCR have identical variable region sequences, this data suggests that the enhanced tetramer binding and function following the REP in the Mur-F5 transduced cells is likely due to the addition of the murine constant region resulting in improved pairing between the TCR α and β chains and increased levels of MART-1-reactive TCR on the cell surface. In contrast, previous reports [17] have shown no functional differences in long-term cultures of genetically modified T cells when expressing comparable levels of TCR; however, the PBL in those experiments had experienced at least six rounds of peptide stimulation to achieve TCR levels comparable to the levels of WT-F5 and Mur-F5 TCR expression in transduced PBL following a single stimulation. In addition, the level of tetramer-positive cells in those experiments was drastically reduced compared to the levels we have seen following transduction with WT-F5 and Mur-F5 both after a single stimulation and a REP. However, only the modified TCR in those experiments bound significant amounts of tetramer following in vitro peptide stimulation suggesting that the TCR modifications improved pairing and exogenous TCR expression on the cell surface. It is possible that TCR modifications affect each TCR differently and in the case of modified WT-1 TCRs, the benefits of improved pairing are only observed when the level of TCR is limiting. In the case of the MART-1 reactive TCR, it has recently been shown that both partial and fully murinized TCR are less likely to form mixed dimmers in the presence of an endogenous human TCR [19]. Thus, the preferential pairing associated with the murine constant region sequences would prevent the dilution of the antigen-specific endogenous TCR on the cell surface capable of binding tetramer, as well as, mediating the enhanced antitumor activity.

In a recent review, Gattinoni et al. [30] described a model for linear differentiation/activation of T cells. It is unknown whether the introduction of an exogenous murine-human chimeric TCR would have an effect on T cell differentiation in a T cell already expressing an endogenous TCR. In this model, as T lymphocytes differentiate from naïve-like to effector cells, they acquire a greater capacity to release IFNγ during an antigen-specific response, which might account for the enhanced antitumor activity of the Mur-F5 TCR following a REP. Our data suggest that expression of an exogenous high avidity TCR, either WT-F5 or Mur-F5, did not adversely affect the ability of a T cell expressing an endogenous receptor to become activated and differentiate into effector T cells (Fig. 4). However, because the overall TCR expression did not change between S1 and R2 cells (Fig. 2), differentiation into a more effector-like cell cannot alone account for the enhanced tetramer binding and expression of the Mur-F5 TCR on the cell surface. In fact, even though the WT-F5 TCR-transduced PBL exhibited higher levels of effector-memory T cells following a REP, functionally they produced less IFNγ when stimulated with the appropriate HLA-restricted tumor antigen-positive targets. As mentioned previously, the highest objective response rates for the treatment of patients with melanoma are observed following TIL ACT. Interestingly, the differentiation phenotype of TIL, similar to an R2 cell, is CD45RA−/CD62L− or that of an effector T cell. In contrast, recent mouse data would suggest that less differentiated cells (more similar to S1 cells) would be more effective at mediating tumor regression and cures in mice [3, 31]. Clearly more studies will be required to determine which T cell subpopulation is optimal for successful ACT immunotherapy using genetically modified PBL.

In an effort to further enhance TCR pairing and improve function, modifications to the Mur-F5 TCR were made including addition of a second disulfide bond within the constant region of the TCR and use of an optimized 2A linker sequence (Fig. 5). All the constructs showed enhanced tetramer binding when compared with the original Mur-F5 TCR most likely as a result of enhanced TCR cell surface expression due to improved pairing. However, increased tetramer binding did not correlate with enhanced function as measured by cytokine release. These results suggest that while TCR modifications may enhance tetramer binding, when the level of tetramer binding is high, possibly approaching saturation, any added functional benefit may not be easily observed. Taken together, we have shown that replacing the human constant region of a TCR with its murine counterpart can lead to enhanced tetramer binding and function of TCR-transduced PBL following a REP. It would appear that genetic modifications to the constant regions of human TCRs will need to be evaluated independently for each TCR being developed, particularly in the case of low avidity TCRs where the added functional benefits may be more pronounced. In addition, one can now minimize the degree of murine sequence necessary to reduce the formation of mixed dimmers while maintaining the preferential pairing of an exogenous TCR. Efforts are underway to determine additional genetic modifications that could further enhance T cell function in bulk PBL and specific T cell subsets that might mediate improved tumor regressions in vivo.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Arnold Mixon and Shaun Farid for assistance with flow cytometry and Dr. Paul F. Robbins for critical review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Balch C, Atkins M, Sober A. Cutaneous Melanoma. In: Devita V Jr, Helman S, Rosenber S, editors. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. 7. Philadelphia: Lippincott Willliams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 1754–1808. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith FO, Downey SG, Klapper JA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, et al. Treatment of metastatic melanoma using interleukin-2 alone or in conjunction with vaccines. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5610–5618. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dudley ME, Yang JC, Sherry R, Hughes MS, Royal R, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5233–5239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2346–2357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298:850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen CJ, Zheng Z, Bray R, Zhao Y, Sherman LA, et al. Recognition of fresh human tumor by human peripheral blood lymphocytes transduced with a bicistronic retroviral vector encoding a murine anti-p53 TCR. J Immunol. 2005;175:5799–5808. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engels B, Uckert W. Redirecting T lymphocyte specificity by T cell receptor gene transfer—a new era for immunotherapy. Mol Aspects Med. 2007;28:115–142. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y, Zheng Z, Robbins PF, Khong HT, Rosenberg SA, et al. Primary human lymphocytes transduced with NY-ESO-1 antigen-specific TCR genes recognize and kill diverse human tumor cell lines. J Immunol. 2005;174:4415–4423. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes MS, Yu YY, Dudley ME, Zheng Z, Robbins PF, et al. Transfer of a TCR gene derived from a patient with a marked antitumor response conveys highly active T-cell effector functions. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:457–472. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clay TM, Custer MC, Sachs J, Hwu P, Rosenberg SA, et al. Efficient transfer of a tumor antigen-reactive TCR to human peripheral blood lymphocytes confers anti-tumor reactivity. J Immunol. 1999;163:507–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Hughes MS, Yang JC, et al. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314:126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson LA, Heemskerk B, Powell DJ, Jr, Cohen CJ, Morgan RA, et al. Gene transfer of tumor-reactive TCR confers both high avidity and tumor reactivity to nonreactive peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2006;177:6548–6559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson LA, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Cassard L, Yang JC, et al. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood. 2009;114:535–546. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulter JM, Jakobsen BK. Stable, soluble, high-affinity, engineered T cell receptors: novel antibody-like proteins for specific targeting of peptide antigens. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;142:454–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen CJ, Zhao Y, Zheng Z, Rosenberg SA, Morgan RA. Enhanced antitumor activity of murine-human hybrid T-cell receptor (TCR) in human lymphocytes is associated with improved pairing and TCR/CD3 stability. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8878–8886. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen CJ, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA, et al. Enhanced antitumor activity of T cells engineered to express T-cell receptors with a second disulfide bond. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3898–3903. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas S, Xue S-A, Cesco-Gaspere M, San Jose E, Hart DP, et al. Targeting the Wilms tumor antigen 1 by TCR gene transfer: TCR variants improve tetramer binding but not the function of gene modified human T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:5803–5810. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuball J, Dossett ML, Wolfl M, Ho WY, Voss R-H, et al. Facilitating matched pairing and expression of TCR chains introduced into human T cells. Blood. 2007;109:2331–2338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bialer G, Horovitz-Fried M, Ya’acobi S, Morgan RA, Cohen CJ, et al. Selected murine residues endow human TCR with enhanced tumor recognition. J Immunol . 2010;184(11):6232–6241. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeves L, Cornetta K. Clinical retroviral vector production: step filtration using clinically approved filters improves titers. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1993–1998. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeves L, Smucker P, Cornetta K. Packaging cell line characteristics and optimizing retroviral vector titer: the National Gene Vector Laboratory experience. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:2093–2103. doi: 10.1089/104303400750001408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riddell SR, Greenberg PD. The use of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies to clone and expand human antigen-specific T cells. J Immunol Methods. 1990;128:189–201. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90210-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wargo J, Robbins P, Li Y, Zhao Y, El-Gamil M, et al. Recognition of NY-ESO-1 + tumor cells by engineered lymphocytes is enhanced by improved vector design and epigenetic modulation of tumor antigen expression. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:383–394. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0562-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Topalian S, Solomon D, Rosenberg S. Tumor-specific cytolysis by lymphocytes infiltrating human melanomas. J Immunol. 1989;142:3714–3725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster AE, Marangolo M, Sartor MM, Alexander SI, Hu M, et al. Human CD62L-memory T cells are less responsive to alloantigen stimulation than CD62L + naive T cells: potential for adoptive immunotherapy and allodepletion. Blood. 2004;104:2403–2409. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders M, Malegapuru W, Shaw S. Human naive and memory T cells: reinterpretation of helper-inducer and suppressor-inducer subsets. Immunol Today. 1988;9:195–199. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(88)91212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Palmer DC, Wrzesinski C, Kerstann K, et al. Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the in vivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells. J Clin Investig. 2005;115:1616–1626. doi: 10.1172/JCI24480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boulter JM, Glick M, Todorov PT, Baston E, Sami M, et al. Stable, soluble T-cell receptor molecules for crystallization and therapeutics. Protein Eng. 2003;16:707–711. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuball J, Hauptrock B, Malina V, Antunes E, Voss R-H, et al. Increasing functional avidity of TCR-redirected T cells by removing defined N-glycosylation sites in the TCR constant domain. J Exp Med. 2009;206:463–475. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gattinoni L, Powell DJ, Jr, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: building on success. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:383–393. doi: 10.1038/nri1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hinrichs CS, Kaiser A, Paulos CM, Cassard L, Sanchez-Perez L, et al. Type 17 CD8+ T cells display enhanced antitumor immunity. Blood. 2009;114:596–599. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]