Background: BRAFV600E melanoma cells develop resistance to vemurafenib. The BRAF/ERK axis controls melanoma cell proliferation. Aurora B is a key actor of mitosis.

Results: The BRAF/ERK axis regulates Aurora B. Vemurafenib-resistant melanoma cells are sensitive to Aurora B inhibition.

Conclusion: Aurora B is a valuable target in melanoma cells.

Significance: Our findings provide insights into Aurora B regulation and on new druggable targets to overcome vemurafenib resistance.

Keywords: Cancer Biology, Drug Action, ERK, Melanoma, Mitosis, Aurora B, Vemurafenib

Abstract

Metastatic melanoma is a deadly skin cancer and is resistant to almost all existing treatment. Vemurafenib, which targets the BRAFV600E mutation, is one of the drugs that improves patient outcome, but the patients next develop secondary resistance and a return to cancer. Thus, new therapeutic strategies are needed to treat melanomas and to increase the duration of v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF) inhibitor response. The ERK pathway controls cell proliferation, and Aurora B plays a pivotal role in cell division. Here, we confirm that Aurora B is highly expressed in metastatic melanoma cells and that Aurora B inhibition triggers both senescence-like phenotypes and cell death in melanoma cells. Furthermore, we show that the BRAF/ERK axis controls Aurora B expression at the transcriptional level, likely through the transcription factor FOXM1. Our results provide insight into the mechanism of Aurora B regulation and the first molecular basis of Aurora B regulation in melanoma cells. The inhibition of Aurora B expression that we observed in vemurafenib-sensitive melanoma cells was rescued in cells resistant to this drug. Consistently, these latter cells remain sensitive to the effect of the Aurora B inhibitor. Noteworthy, wild-type BRAF melanoma cells are also sensitive to Aurora B inhibition. Collectively, our findings, showing that Aurora B is a potential target in melanoma cells, particularly in those vemurafenib-resistant, may open new avenues to improve the treatment of metastatic melanoma.

Introduction

Metastatic melanomas represent the most deadly form of skin cancer. Malignant melanoma is curable by surgical excision when detected at an early stage, but once it has metastasized, the complete removal is not possible and metastatic melanoma is highly refractory to all existing treatments. Patients with metastatic melanoma have a median survival that typically ranges from 6 to 10 months. Dacarbazine was a standard of metastatic melanoma treatment, but the response to this chemotherapy drug was often incomplete and associated with disease relapse. Recently, targeted therapies have shown their efficiency in melanoma treatment. The monoclonal antibody against the negative T-cell regulator cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (Ipilimumab) improves the overall survival, but its best overall response rate is limited to only 10% of patients (1). Furthermore, targeted therapy against BRAFV600E with vemurafenib in a subset of melanomas has shown the potential to improve the overall survival of patients. However, the patients invariably develop relapses and show progressive disease after a period free of progression. Thus, new therapeutic strategies are urgently needed to lengthen the response to Raf inhibitors. BRAFV600E mutation is found in about 40–60% of melanomas (2), and 48% of them respond to vemurafenib treatment (3). Thus, the search remains to find efficient treatment for the majority of patients who develop melanoma.

Tumor progression depends on expansion of tumor cells through mitotic cell division. This process requires numerous proteins and protein complexes that will ensure the accurate control of the events involved in the mitotic cell cycle. Among them, the chromosomal passenger protein complex, composed of Aurora B kinase, Survivin, Borealin, and INCENP, is a critical mitotic regulator (4). Chromosomal passenger protein complex function is essential to chromosome condensation, kinetochore-chromosome attachment, chromosome alignment at the metaphase plate, and control of the spindle checkpoint. Given their function in the control of the G2/M phase, the expression of the chromosomal passenger protein complex proteins is controlled in a cell cycle-dependent manner. However, increased expression of some of these components such as Aurora B and Survivin has been observed in a spectrum of cancers, including melanoma (5, 6), and predicts early tumor recurrence and poor prognosis (7, 8).

Their targeting is therefore being pursued as attractive cancer targets. Although Survivin function in melanoma cells is well documented that of Aurora B is less well determined. Aurora B belongs to the mammalian Aurora Kinase family Aurora A (AURKA), Aurora B (AURKB), and Aurora C (AURKC). Inhibitors of Aurora kinases, ZM447439, PHA-680, hesperadin, PF-03814735, SNS-314, VE-465, and MK0457/VX-680, have shown promising anti-tumor effects in several cell types (9, 10), including melanoma cells (5, 6). Recently, AZD1152, a highly potent and specific aurora kinase inhibitor with 1000-fold selectivity for Aurora B over Aurora A kinase activity, has been developed (11). AZD1152 is a prodrug that is metabolized in the serum to its active form AZD1152-hydroxyquinazoline pyrazol anilide (HQPA),5 an ATP binding pocket competitor. Preclinical studies have shown the antineoplasic properties of AZD1152 in acute myelogenous leukemia, multiple myeloma, colorectal and breast cancer, yet the effect of AZD1152 remains to be explored in melanoma cells.

Here, we confirm an increased expression of Aurora B during melanoma progression that starts in cells from the vertical growth phase melanomas. We show that Aurora B inhibition by AZD1152-HQPA triggers cell cycle arrest, cellular senescence, and cell death by mitotic catastrophe. Similar results were obtained with Aurora B specific siRNA. Preclinical studies show that Aurora B inhibition by AZD1152-HQPA dramatically inhibits growth of human melanoma xenografts. Additionally, we provide insights into the mechanisms of Aurora B regulation in melanoma cells by demonstrating that Aurora B is a target of the ERK pathway. Stimulation of the ERK pathway by growth factors enhances Aurora B expression, whereas its inhibition by vemurafenib strongly decreases Aurora B mRNA and protein levels. Vemurafenib also triggered a decrease in the level of FOXM1, a factor reported to regulate the transcription of Aurora B. Collectively, these observations indicate that the BRAF/ERK axis controls Aurora B at the transcriptional level. The decreased expression of Aurora B upon vemurafenib in the vemurafenib-sensitive melanoma cells is recovered in cells resistant to this drug. In these latter cells, we demonstrate that Aurora B inhibition promotes cell death of vemurafenib-resistant melanoma cells. This study may open new therapeutic strategies targeting Aurora B to improve the management of metastatic melanoma.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

AZD1152-HQPA and vemurafenib (PLX-4032) were obtained from Selleck Chemicals LLC (Houston, TX). Labrafil M1944Cs was purchased from Gattefosse (Saint Priest, France). Monoclonal antibodies to Aurora B and caspase-3 were from BD Transduction Laboratories, and monoclonal antibodies to ERK2 (D-2), AIF (E-1), and actin (9) and polyclonal antibodies to Rb (C-15), FOXM1 (A-11), p53 (DO-1), and HSP60 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Monoclonal antibodies to phospho-histone H3 (Ser-10), phospho-Aurora B (Thr-232), procaspase-2, and phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204) and polyclonal antibodies to phospho-RB (Ser-807/811), histone H3, AKT, pS473-AKT, pT68-CHK2, and PARP were from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Beverly, MA). Monoclonal antibody to γH2AX was from Millipore. Polyclonal antibody to Smac-Diablo was from Upstate Cell Signaling (Billerica, MA).

Cell Cultures

Human melanocyte cultures were obtained from the foreskins of Caucasian children as described previously (12). The different melanoma cell lines were described previously (13).

Construction of Vemurafenib-resistant Melanoma Cells

Fresh sterile tissues were obtained from surgical waste from patients diagnosed with metastatic melanoma at the Nice Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Hospital and were treated as reported previously (#1 and #2) (14). Informed consent was obtained from the patients. Genomic DNA was prepared with the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen). DNA was amplified by PCRs with specific primers, and Sanger sequencing was performed on a 3730 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems). We established vemurafenib-resistant melanoma cells by exposing vemurafenib-naive parental melanoma cells (#1) or the human melanoma cell line WM9 (a gift of Dr. M. Herlyn, The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia) to incremental increases of vemurafenib. Vemurafenib-resistant selection continued until the melanoma cells could sustain viability and proliferate when challenged with 20 μm vemurafenib. Sequencing of the vemurafenib-resistant melanoma cells indicated that they did not harbor secondary BRAF mutations or N-RAS mutations.

Transient Transfection of siRNA

Briefly, a single pulse of 50 nm siRNA was administered to the cells at 50% confluency by transfection with 5 μl of LipofectamineTM RNAiMAX in Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen). Control scrambled (siC) and Aurora B specific-siRNA (siAURKB) was described previously (15).

Subcellular Fractionation and Western Blot Assays

Subcellular fractionation was performed using proteoextract subcellular proteome extraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Calbiochem). Western blotting experiments were performed as described previously (16). Western blot analysis data were repeated at least three times.

Cell Viability Test

Cell viability was assessed using the cell proliferation kit II (XTT; Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cell viability, measured at 490 nm, was expressed as the percentage of the value in DMSO-treated cells.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were stained with propidium iodide (40 μg/ml) containing ribonuclease A (10 μg/ml) and were analyzed using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (MACSQuant® analyzer) and MACSQuantifyTM software.

Caspase Activities

Proteins were extracted with a buffer containing 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors.

Samples (50 μg) were incubated with or without 0.2 mm N-acetyl-DEVD-amido-4-methylcoumarin (caspase-3) or 0.2 mm N-acetyl-VDVAD-amido-4-methylcoumarin (caspase-2) in triplicate. To assess specific caspase activities, hydrolysis was followed at different times at 37 °C in the presence or absence of 1 mm N-acetyl-DEVD-CHO or N-acetyl-VDVAD-CHO (Villeurbanne, France). Caspase activities were expressed as arbitrary units. Each experiment was done in triplicate.

Senescence-associated β-Galactosidase Assay and Immunofluorescence

The senescence β-galactosidase staining kit (Cell Signaling Technology) and immunofluorescences were performed as reported before (14).

mRNA Preparation, Real Time/Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCRs were performed as reported previously (17). Primer sequences for each cDNA were designed using qPrimer depot (primerdepot.nci.nih.gov) and are available upon request.

In Vivo Murine Cancer Model

Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with French law and were approved by a local institutional ethical committee. Animals were maintained in a temperature-controlled facility (22 °C) on a 12-h light/dark cycle and were given free access to food (standard laboratory chow diet from UAR, Epinay-S/Orge, France). Human A375 melanoma cells (2.5 × 106 cells) were inoculated subcutaneously into 6-week-old female immune-deficient Athymic Nude FOXN1nu mice (Harlan Laboratory). When the tumors became palpable, mice received a daily intratumoral injection for 7 days of AZD1152-HQPA (30 mg/kg/day) dissolved in a mixture of Labrafil M1944 Cs, dimethylacetamide, and Tween 80 (90:9:1, v/v/v). Control mice were injected with Labrafil alone.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the average ± S.D. and were analyzed by Student's t test using Microsoft Excel software. A p value of 0.05 (*, p < 0.05) or less (**, p < 0.01, and ***, p < 0.001) was interpreted as indicating statistical significance when comparing experimental and control groups.

RESULTS

Aurora B Inhibition Induces Melanoma Cell Growth Arrest

We first examined Aurora B expression in normal human melanocytes and in melanoma cell lines of different stages of progression. As reported previously, Aurora B was expressed at high levels in metastatic melanoma (supplemental Fig. S1A) (6).

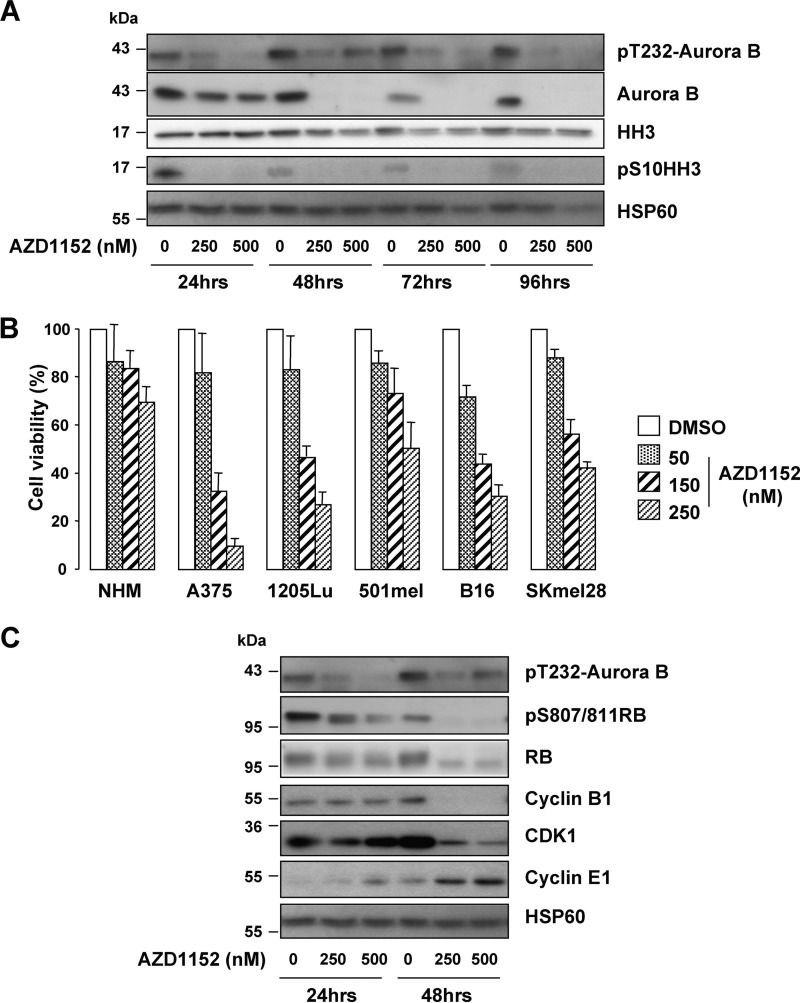

We next conducted experiments to assess the effect of the Aurora B-specific inhibitor, AZD1152-HQPA (herein referred to as simply AZD1152), on melanoma cell viability. Activation of Aurora B kinase occurs through its autophosphorylation of Thr-232 in the kinase activation loop (18). Detection of this modification with anti-phosphothreonine 232 Aurora B antibody revealed a decreased Aurora B phosphorylation in response to AZD1152 treatment (Fig. 1A). Decreased Aurora B phosphorylation was observed as early as 30 min post-AZD1152 treatment (data not shown). Chromosome condensation during mitosis requires phosphorylation of histone H3 on serine 10 by Aurora kinase B (19). In this regard, the reduced Histone H3 serine 10 phosphorylation confirmed the efficiency of AZD1152. AZD1152 also caused a reduction in Aurora B expression, in agreement with findings in breast cancer cells (20). Having shown the efficiency of AZD1152, normal human melanocytes and melanoma cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations of AZD1152 from 50 to 250 nm, and cell proliferation was assessed (Fig. 1B). Normal melanocytes were highly resistant to the AZD1152 effect with only 30% reduction in cell proliferation at the highest concentration of 250 nm. In contrast, all the melanoma cell lines tested displayed higher sensitivity to AZD1152 effect (Fig. 1B). AZD1152 also showed potent inhibition of melanoma cells in a colony-forming assay (supplemental Fig. S1B). The pro-apoptotic inducer staurosporine, used as positive control, also dramatically inhibited melanoma cell growth. These results demonstrate that melanoma cell lines of different genetic background and species are sensitive to the growth inhibitory activity of AZD1152.

FIGURE 1.

Inhibition of metastatic melanoma cell proliferation by the Aurora B inhibitor AZD1152. A, human A375 melanoma cells were exposed to increasing concentration of AZD1152-HQPA (250 and 500 nm), and lysates were analyzed with the indicated antibodies. B, normal human melanocytes, human melanoma cells (A375, 1205LU, 501mel, and SkMel28), and mouse B16 melanoma cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of AZD1152-HQPA for 48 h, and then cell proliferation was assessed using the colorimetric XTT assay. C, lysates of A375 cells exposed to increasing concentrations of AZD1152 (250 and 500 nm) were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

In agreement with a proliferation cessation, human A375 melanoma cells exposed to AZD1152 showed a decreased phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein on Ser-807/811 and a shift down of total Retinoblastoma protein (RB), signs of hypophosphorylation (Fig. 1C). Cyclin B1 and cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) level also declined post-AZD1152 treatment and that of Cyclin E1 increased.

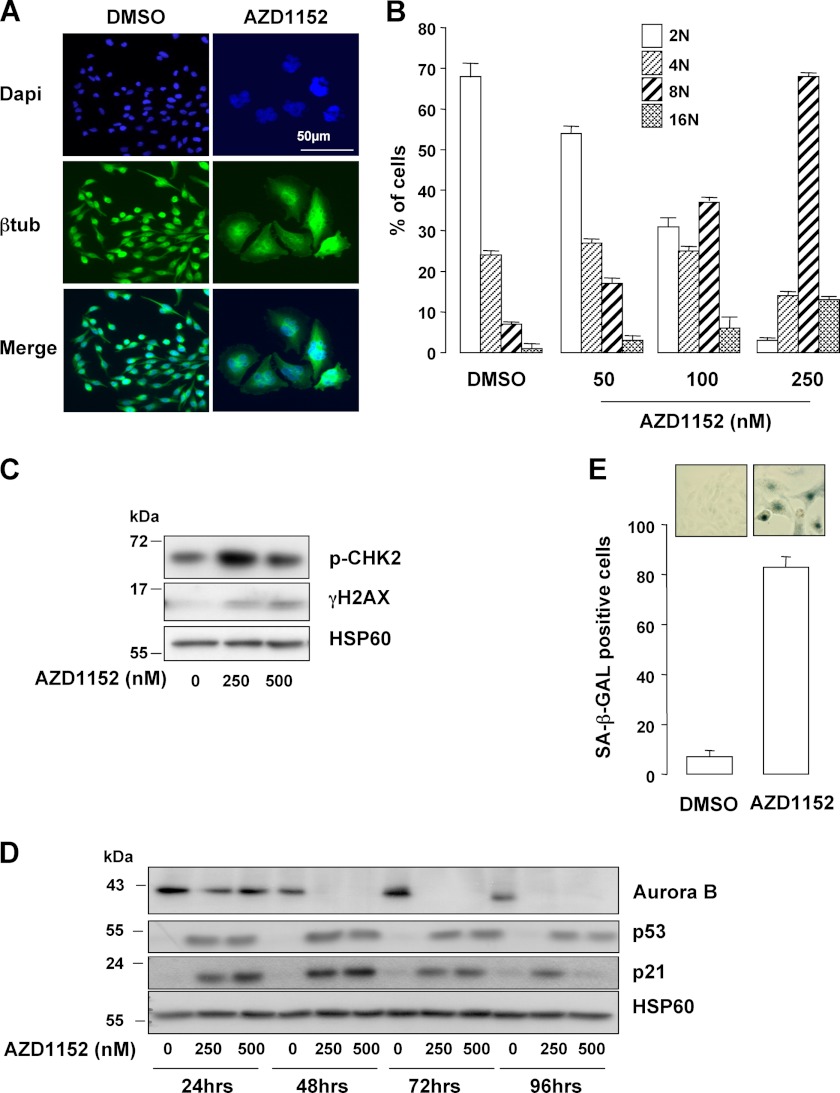

Reduction of phosphorylated Ser-10 Histone H3 has been associated with cytokinesis failure. Immunofluorescence with antibody to β-tubulin and DAPI staining revealed enlargement and polyploidization of A375 cells exposed to AZD1152 (Fig. 2A). Flow cytometry analysis confirmed that A375 melanoma cells exposed to AZD1152 became polyploid as illustrated by the high proportion of 8N and 16N cells 48 h post-treatment (Fig. 2B). Note that a small proportion of 8N and 16N cells may be observed in control conditions that may reflect the disruption of the normal cell cycle control observed in transformed cells. The percentage of 8N A375 cells rose from 7% before treatment to 70% at 48 h with AZD1152. Karyokinesis failure was associated with DNA damages and senescence entry. Indeed, AZD1152 triggered activation of the DNA damage response pathway, illustrated by the detection of activated phospho-CHK2 (p-CHK2) and the increase in γH2AX levels (Fig. 2C). Senescence-like phenotypes such as senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) staining (Fig. 2E), increased cell size (supplemental Fig. S2A), and cell granularity (supplemental Fig. S2B) were observed in cells that remained attached to the culture dishes in response to AZD1152. In these conditions, p53 and its target gene p21Cip were up-regulated (Fig. 2D). Several other melanoma cell lines and the freshly isolated melanoma cells tested also underwent senescence-like phenotypes such as SA-β-Gal staining (supplemental Fig. S2C), indicating this process was not unique to a particular cell type.

FIGURE 2.

Aurora B inhibition induces polyploidization and senescence entry. A, immunofluorescence experiments of A375 cells exposed to 250 nm AZD1152-HQPA for 48 h were labeled with anti-β-tubulin antibody (btub). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. B, FACS analysis of A375 melanoma cells exposed to increasing concentrations of AZD1152-HQPA for 48 h. C, A375 cells treated with AZD1152-HQPA for 24 h were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to phospho-Ser-387 CHK2 (pCHK2) and γH2AX. HSP60 ensures the even loading of each lane. D, human A375 melanoma cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of AZD1152-HQPA (250 and 500 nm), and lysates were analyzed with antibodies to p53 and p21. E, A375 cells were exposed to AZD1152-HQPA 250 nm for 96 h and cells remained adherent were analyzed for the SA-β-Galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) reactivity. The percentage of means ± S.D. was derived from counting 100 cells in duplicate plates.

Inhibition of Aurora B by a genetic approach (siRNA) engendered similar results. A dramatic reduction in the number of A375 cells as a function of time was observed (supplemental Fig. S3A) and was associated with a time-dependent decrease in Histone H3 phosphorylation at serine 10, in the level of CDK1 and Cyclin B1 and with the hypophosphorylation of the Retinoblastoma protein (RB) (supplemental Fig. S3B). Conversely, the level of; cyclin E1 increased. These observations thereby demonstrate that suppression of Aurora B activity triggers a cell cycle arrest.

Aurora B Inhibition Promotes Death by Mitotic Catastrophe

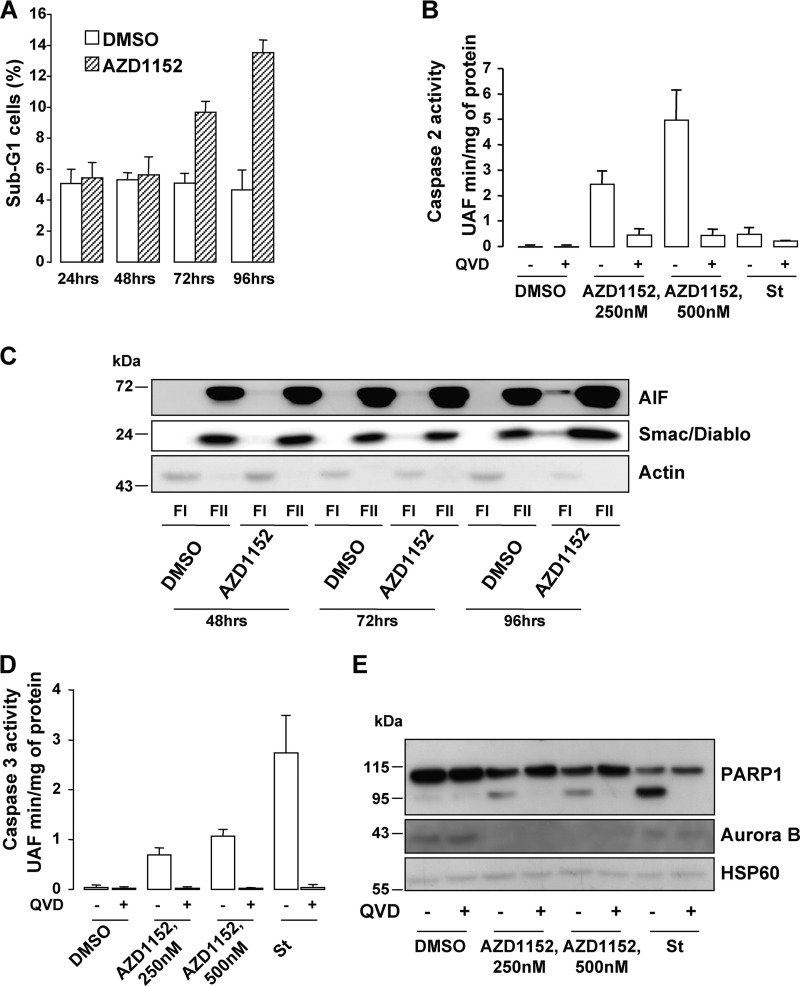

A sub-G1 fraction was detectable 72 h post-AZD1152 exposure (Fig. 3A). Cell death occurring during mitosis is referred to as a mitotic catastrophe and often takes place in conjunction with apoptosis. Activation of caspase-2 and release of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and SMAC/DIABLO from mitochondria were suggested as characteristics of mitotic catastrophe (21).

FIGURE 3.

Aurora B inhibition triggers cell death. A, sub-G1 FACS analysis of A375 melanoma cells exposed to 250 nm AZD1152-HQPA using propidium iodide. B, caspase-2 activity was assessed in lysates of A375 cells exposed to AZD1152-HQPA for 96 h. When indicated, the pan-caspase inhibitor QVD-OPH (QVD, 20 mm) was added to the reactions. The pro-apoptotic inducer staurosporine (1 μm) was used as a negative control. C, cytoplasmic (FI) and microsomal (FII) fractions of A375 cells exposed for the time indicated to 250 nm AZD1152-HQPA were analyzed by Western blotting with AIF, Smac/Diablo, and actin antibodies. D, caspase-3 activity was assessed in lysates of A375 cells exposed to AZD1152-HQPA for 96 h. When indicated, the pan-caspase inhibitor QVD-OPH (20 mm) was added to the reactions. The pro-apoptotic inducer staurosporine (1 μm) was used as a positive control. E, A375 cell lysates exposed for 96 h to 250 nm AZD1152-HQPA with or without 20 mm QVD-OPH were analyzed by Western blotting with total PARP1, Aurora B, and HSP60 antibodies.

AZD1152-mediated caspase-2 activation was observed by fluorometric assay and was abolished by the caspase inhibitor QVD (Fig. 3B). Kinetic experiments showed the disappearance of the inactive procaspase-2 with the concomitant detection of the cleaved fragments in Western blot experiments (supplemental Fig. S4A). These observations indicated that the inactive procaspase-2 was processed to its catalytically active form. Furthermore, cell fractionation assays showed the presence of AIF and SMAC/DIABLO in the cytoplasmic fraction of cells exposed to AZD1152 relative to control cells, with a maximum release after 96 h (Fig. 3C). AZD1152 also triggered caspase-3 activation (Fig. 3D) and the cleavage of PARP, one of the best studied caspase-3 substrates (Fig. 3E). Both caspase-3 and PARP cleavage were prevented in the presence of the caspase inhibitor QVD. Staurosporine, a mitotic catastrophe-independent inducer of apoptotic cell death, did not promote procaspase-2 processing nor the generation of active fragments, but as expected, it enhanced caspase-3 activity and cleavage of PARP. These events were counteracted by QVD (Fig. 3, B, D, and E). AZD1152, the efficiency of which was monitored by the disappearance of Aurora B in Western blot, promoted caspase-2 activation as evidenced by the disappearance of the inactive procaspase-2 in several cell lines and freshly isolated melanoma cells (supplemental Fig. S4B). Similarly, Aurora B inhibition by siRNA elicited cell death in all the melanoma cells tested. An increase in the sub-G1 population (supplemental Fig. S5) and a time-dependent disappearance of procaspase-2 with the concomitant appearance of its cleaved fragments (supplemental Fig. S6A) were indeed observed. Cell fractionation assays also showed the presence of AIF and SMAC/DIABLO in the cytoplasmic fraction in Aurora B-silenced cells relative to cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (supplemental Fig. S6B). Aurora B knockdown and staurosporine enhanced caspase-3 enzymatic activity (supplemental Fig. S6C) and cleavage of PARP (supplemental Fig. S6D), and both were impaired by QVD treatment. Thus, Aurora B inhibition either by pharmacological (AZD1152) or genetic (siRNA) approaches ends in apoptosis of melanoma cells.

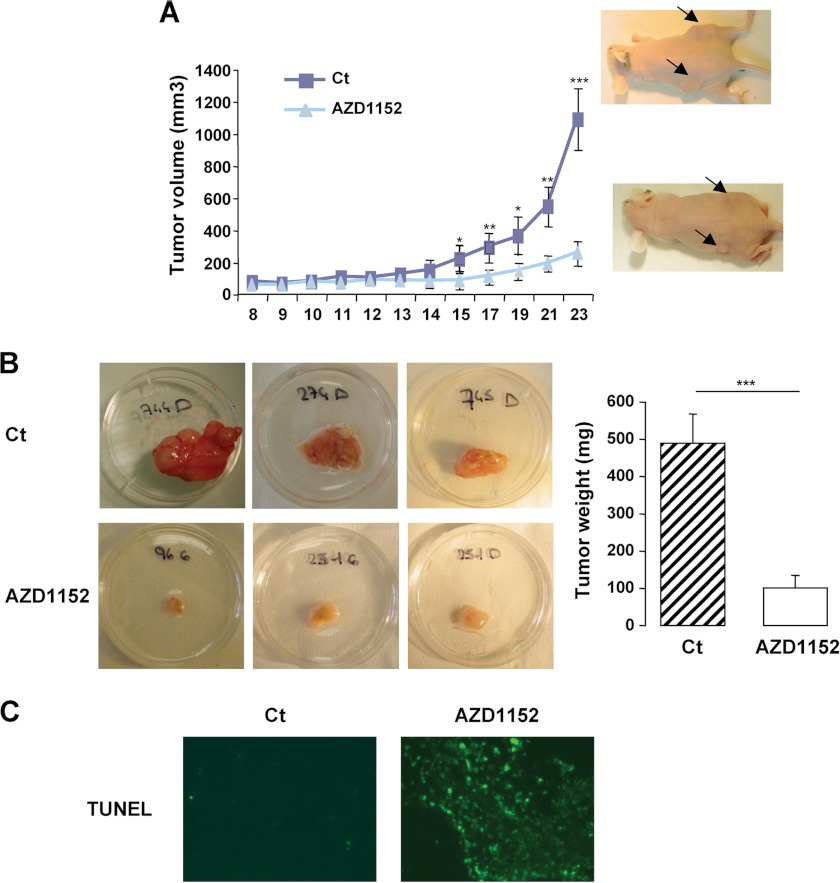

AZD1152 Prevents Growth of Human Melanoma Tumor Xenografts

The antineoplasic effect of AZD1152 was next investigated in vivo. To this aim, the highly aggressive A375 melanoma cells were engrafted subcutaneously into 6-week-old female athymic nude mice. When the tumors became palpable (0.2–0.5 cm3), mice were treated with the Aurora kinase inhibitor at a dose of 30 mg/kg or with its vehicle (labrafil) for 7 days. Tumors were measured over a period of 15 days. Dose of AZD1152 was based on a previous report (20). Treatment with the inhibitor dramatically impaired melanoma tumor growth (Fig. 4A) compared with tumors that received the vehicle alone. Excised tumors in the AZD1152 group weighed significantly less than those in the control group and appeared less vascularized (Fig. 4B). Consistently, a section of AZD1152-treated tumors revealed the presence of cell death as illustrated by the high percentage of TUNEL-positive cells compared with control of tumor sections where almost no TUNEL-positive cells could be observed (Fig. 4C). Thus, Aurora B inhibition by AZD1152 displays clear anti-melanoma abilities also in vivo.

FIGURE 4.

In vivo anti-tumor effect of the Aurora B inhibitor AZD1152. A, A375 melanoma cells (2.5 × 106) were subcutaneously engrafted in athymic nude mice. Mice were injected with the vehicle alone (Ct) or with AZD1152-HQPA. The growth tumor curves were determined by measuring the tumor volume using the equation V = (L × W2)/2. Results are presented as mean (±S.E.) tumor volumes (mm3), and p values are from Student's t test (*, p = 0.05; **, p = 0.01; ***, p = 0.001) comparing tumor size in AZD1152-HQPA-treated versus vehicle at each point. B, representative images and means of subcutaneous tumor weight from control (Ct) and AZD1152-HQPA treated mice are shown. C, TUNEL assay on 7-μm tumor sections.

Aurora B Is Controlled by the ERK Signaling Pathway

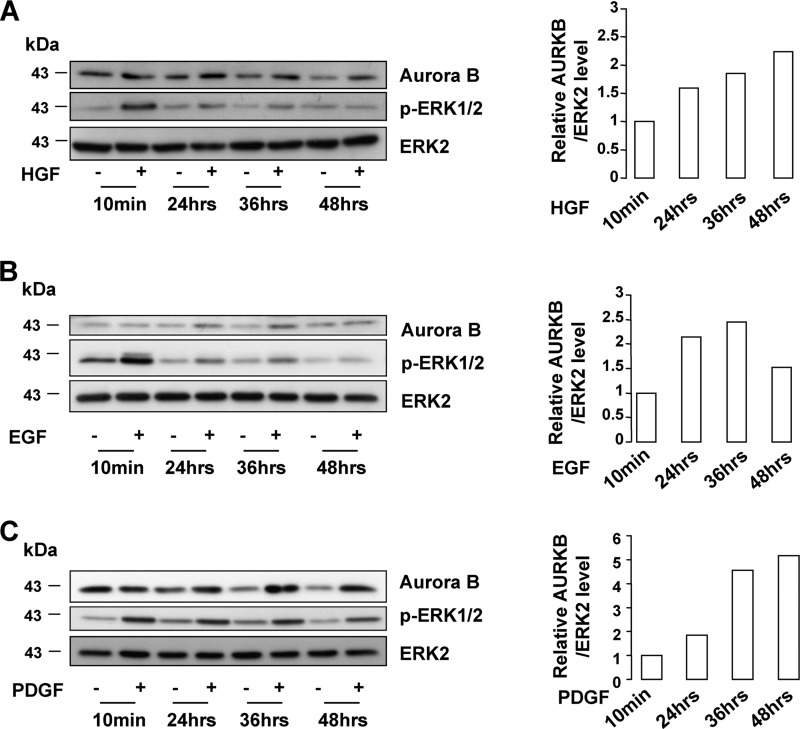

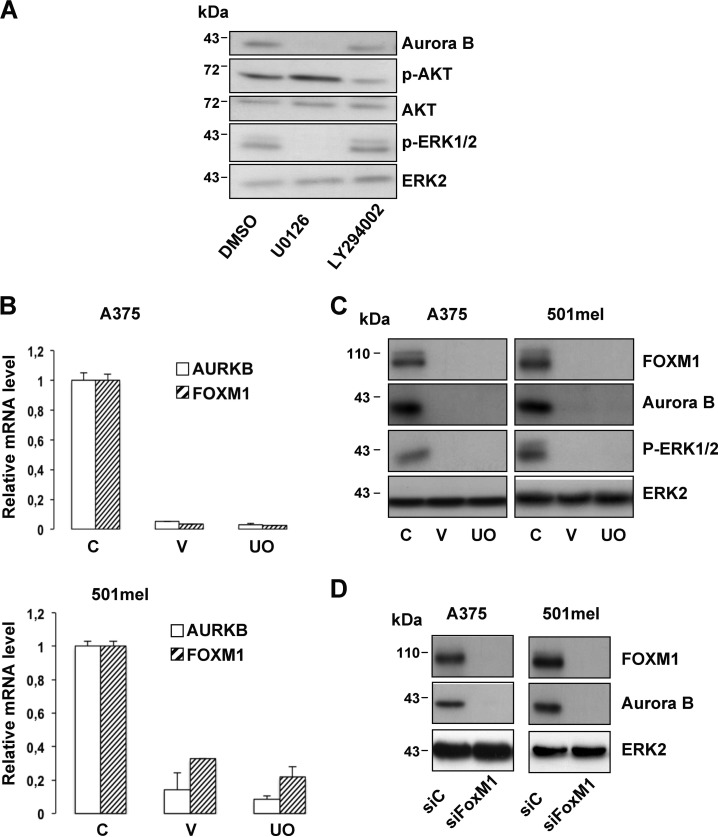

BRAF, which controls the activity of the ERK pathway, is critical for mitotic spindle formation and activation (22, 23). Thus, we were wondering whether Aurora B, which is a critical mitotic regulator, could be a target of the ERK pathway. In MeWo melanoma cells that do not harbor the BRAFV600E activating mutation, ERK activity stimulation by HGF, EGF, or PDGF was associated with increased Aurora B levels (Fig. 5, A–C). However, inhibition of the ERK pathway by U0126 or vemurafenib, currently used in clinics for the treatment of melanoma, impaired Aurora B expression in A375 cells (Fig. 6, A and C). In agreement with these observations, the increased Aurora B expression was associated with an increased level of phospho-ERK1/2 during melanoma progression, although we failed to detect a perfect correlation (supplemental Fig. S1A). Contrastingly, inhibition of the PI3K pathway by LY294002 modestly reduced the Aurora B level (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, our results showed that vemurafenib decreased the mRNA level of Aurora B, indicating that the ERK signaling pathway controls Aurora B at the transcriptional level (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, we found that vemurafenib and UO126 also diminished to a similar extent the mRNA level of FOXM1, a known regulator of Aurora B (24). This inhibition was also seen at the protein level (Fig. 6C). Additionally, FOXM1 silencing by siRNA decreased Aurora B expression (Fig. 6D). Altogether, our results indicate that the BRAF/ERK axis controls Aurora B expression at the transcriptional level through FOXM1.

FIGURE 5.

Aurora B level is up-regulated upon growth factor ERK pathway. MeWo cells were treated with increasing duration of HGF (10 ng/ml) (A), EGF (10 ng/ml) (B), or PDGF (20 ng/ml) (C). Western blots were performed for Aurora B, p-ERK1/2, and ERK2. The densitometric scanning of the AURKB immunoblot bands was performed digitally using the ImageJ software program (National Institutes of Health) and was normalized to the total ERK expression levels.

FIGURE 6.

Aurora B mRNA and protein levels are decreased in response to ERK inhibition. A, A375 melanoma cells were exposed to pharmacological inhibitors of the ERK (U0126, 10 μm) and PI3K (LY294002, 10 μm) signaling pathways for 48 h and were analyzed by Western blotting. B, quantitative PCR analysis of Aurora B and FOXM1 mRNA expression in A375 (upper panel) and 501mel (bottom panel) melanoma cells treated with vemurafenib (V, 10 μm) or UO126 (UO, 10 μm) for 48 h. C is control. C, A375 (left panel) or 501mel (right panel) melanoma cells were exposed to vemurafenib (V, 10 μm) or UO126 (UO, 10 μm) for 48 h. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. C is control. D, Western blot analysis of lysates from A375 (left panel) or 501mel (right panel) transfected with scrambled siRNA control (siC) or FOXM1 siRNA (siFOXM1).

Aurora B Is a Potential Target in Vemurafenib-resistant Melanoma Cells

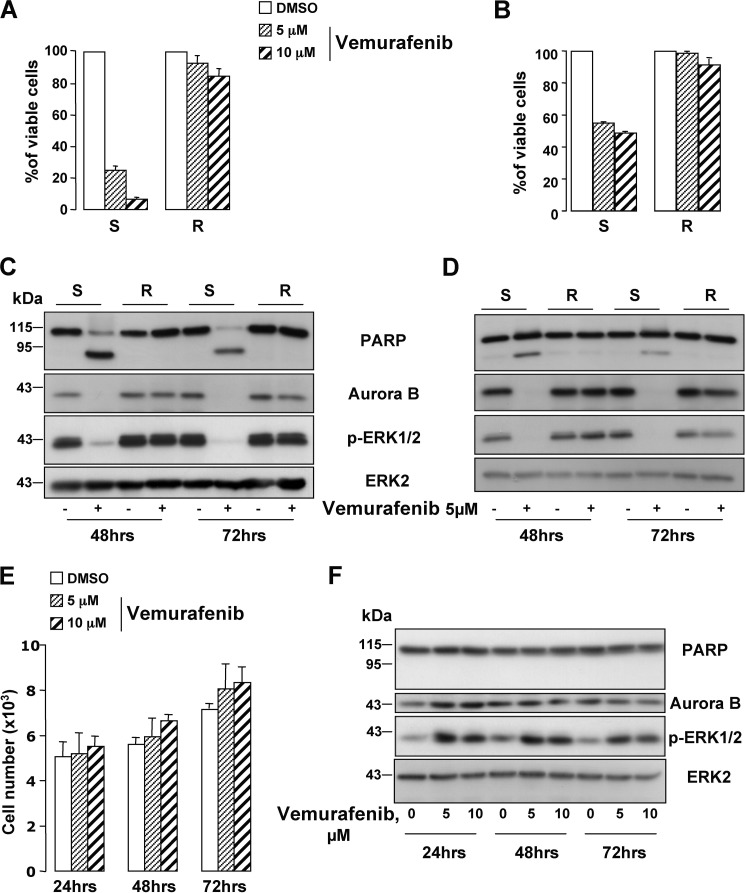

Acquired resistance to vemurafenib is a major obstacle to the effectiveness of this treatment, rendering urgent the identification of alternate targets to treat melanoma in these patients. Melanoma cells, isolated from a human biopsy, and the WM9 melanoma cell line, both harboring the BRAFV600E mutation (supplemental Fig. S7A) (25), were rendered resistant to vemurafenib. XTT-based proliferation assays indicate that vemurafenib diminished the viability (80%) of the parental cells (Fig. 7, A and B). In contrasting, the two types of melanoma cells resistant to vemurafenib displayed almost no decrease in viability or in ERK activity (Fig. 7, C and D) in response to vemurafenib, demonstrating that they escaped the effect of the drug. Interestingly, vemurafenib triggered a diminution of Aurora B levels in the parental cells, whereas Aurora B expression was rescued in vemurafenib-resistant cells (Fig. 7, C and D). This observation agrees with a return to cell proliferation of the resistant cells and the disease relapse in patients. In MeWo melanoma cells expressing wild-type BRAF, vemurafenib did not decrease the proliferation nor induced PARP cleavage (Fig. 7, E and F). Noteworthy, in BRAF-wild-type MeWo cells, vemurafenib induced a stimulation of ERK (increase in phosphorylated ERK1/2), rather than an inhibition. Consequently, an increase in Aurora B level could be observed.

FIGURE 7.

Aurora B is re-expressed in vemurafenib-resistant melanoma cells. Freshly isolated human melanoma cells (#1) (left panel) (A) and WM9 cell line (right panel) (B) were rendered resistant to vemurafenib by continuous in vitro culture in increasing concentrations of the drug. Cell viability of the parental (vemurafenib-sensitive) (S) and of the resistant (R) melanoma cells treated with vemurafenib 5 and 10 μm for 48 h was assessed by XTT. C and D, vemurafenib-sensitive (S) and -resistant (R) melanoma cells (#1, left panel and WM9, right panel) were treated with 5 μm vemurafenib. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. E, effect of vemurafenib 5 and 10 μm on the number of MeWo melanoma cells by cell count. F, MeWo melanoma cells were exposed to 5 and 10 μm vemurafenib for the time indicated on the figure and analyzed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies.

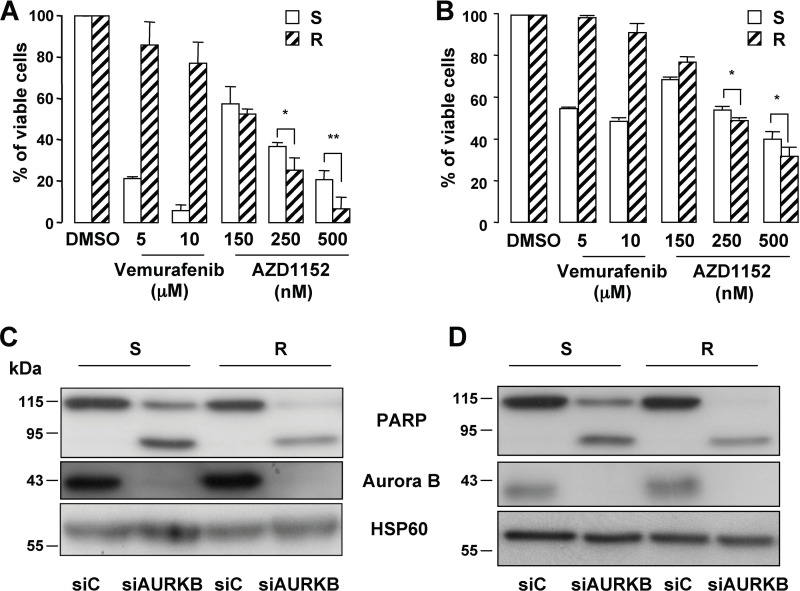

Thus, these observations prompted us to investigate whether the Aurora B inhibitor, AZD1152, could be a therapeutic option. Interestingly, XTT tests showed that vemurafenib-resistant cells remained sensitive to AZD1152. AZD1152 was able to trigger death of the resistant cells, even more efficiently than in the parental vemurafenib-sensitive cells (Fig. 8, A and B). Cell death was evidenced by the processing of procaspase-2 and by the cleavage of PARP (supplemental Fig. S7B), as well as by an increase of dead cells that stained positive for the propidium iodide (supplemental Fig. S7, C and D). In agreement with our previous results (supplemental Fig. S6D), inhibition of Aurora B by specific siRNA led to a processing of PARP as a readout of cell death (Fig. 8, C and D). A processing of PARP was also observed in the resistant cells. Noteworthy, PARP cleavage was higher in the resistant cells relative to the sensitive parental cells. Collectively, these observations indicate that Aurora B inhibition may be a valuable therapeutic option in patients with BRAFV600E metastatic melanoma that developed secondary resistance to vemurafenib and in patients with wild-type BRAF (Fig. 1B and data not shown).

FIGURE 8.

Aurora B is a potential therapeutic target in vemurafenib-resistant melanoma cells. A and B, XTT proliferation assay was performed on the vemurafenib-sensitive (S) and -resistant (R) melanoma cells (#1, left panel and WM9, right panel) treated with increasing concentrations of vemurafenib or AZD1152 for 48 h. Data are significantly different from the sensitive cells at **, p < 0.01, and *, p < 0.05. C and D, Western blot experiment of cell lysates from vemurafenib-sensitive (S) and -resistant (R) melanoma cells (#1, left panel, and WM9, right panel) transfected with Aurora B-specific inhibitor for 96 h.

DISCUSSION

This study has focused upon Aurora B as a potential therapeutic target in melanoma treatment. More particularly, our results indicate that Aurora B inhibition could be a therapeutic option not only in individuals whose melanoma is a wild type for BRAF and for whom there is a current lack of therapies but it also could be seen as an option to lengthen the initial response to Raf inhibitor of BRAFV600E melanoma cells.

Aurora kinase B plays a key role during mitosis, where it is involved in the acute regulation of karyokinesis and cytokinesis, two processes with fundamental consequences on cell proliferation and survival. In contrast to normal cells (26), the cycle of activation/deactivation (degradation) of Aurora B is compromised in tumor cells. Sustained over-representation of Aurora B has been shown to perturb mitotic checkpoints leading to chromosomal aberrations and to result in genomic instability and aneuploidy (27). In the context of melanoma cells, Wang et al. (6) previously reported that Aurora B increased with melanoma progression and that its inhibition could be an anti-melanoma strategy. Here, we confirm these observations in another set of melanoma cells, reinforcing the notion that Aurora B is a valuable therapeutic option.

We show that inhibition of Aurora B by pharmacological (AZD1152) or genetic loss of function (siRNA) approaches elicits melanoma senescence and death. Senescence-like phenotypes are illustrated by polyploidization, enlarged and granular cell shape, and detection of the β-galactosidase activity and of markers of DNA damages. Cell death by mitotic catastrophe is evidenced by polyploidization, caspase-2 activation, and detection of dead cells. Previous works with pan-Aurora inhibitors in melanoma cells (5, 28) and in other tumor types (10, 20) reported similar effects. The progressive disappearance of both Cyclin B1 and CDK1 after Aurora B suppression is consistent with cells that exit mitosis without completion of cytokinesis and with cells that enter a new round of cell division at a higher DNA content. An increased level in Cyclin E, which is implicated in the G1/S transition, also accords well with this deregulated mitotic progression. Consistently, Cyclin E up-regulation was also associated with cell death (29).

In addition to inhibiting Aurora B activity, AZD1152 treatment also dramatically decreases the Aurora B level in melanoma cells. This is reminiscent of a previous report indicating that AZD1152 increased polyubiquitination and proteosomal degradation of Aurora B (20). Aurora B functions in complex with Survivin, Borealin, and INCENP allowing the docking of Aurora B at the right place at the right time during mitosis (30). Depletion of any one subunit of the Aurora B-INCENP-Borealin-Survivin complex caused a substantial reduction not only in the corresponding target but also in the other subunits and may promote cell death (31, 32). Therefore, by using AZD1152, several actors and tumor signaling circuitries may be simultaneously disabled, amplifying the anti-tumor effect of the Aurora B inhibitor.

Little is known about the mechanisms of Aurora B regulation, although the product of the EWS-fli1 translocation genes and FOXM1 were reported to control Aurora B transcription (24, 33, 34). We find that inhibition of BRAF/ERK axis by either vemurafenib or UO126 in BRAFV600E melanoma cells decreases FOXM1 and Aurora B mRNA and protein levels. Additionally, FOXM1 inhibition by siRNA decreases Aurora B expression. However, growth factors, such as HGF, EGF, or PDGF, that are important in melanoma development and progression (35–37) stimulate ERK activity and increase the protein level of Aurora B. Aurora B-regulation by EPS8, a substrate of the EGF receptor pathway (6), or by HGF (38) in HEK293 cells and hepatocytes, respectively, was previously reported. Therefore, although it remains to clearly determine how the BRAF/ERK signaling pathway controls the transcription of Aurora B, our results indicate that this transcriptional regulation could be mediated by FOXM1.

Of note, vemurafenib can elicit senescence-like phenotypes in BRAFV600E melanoma cells such as a SA-β-Gal reactivity (data not shown), but it does not trigger polyploidization, indicating that it does not recapitulate all the phenotypes of Aurora B inhibition. The discrepancies between the phenotypes triggered by the two drugs are consistent with the notion that BRAF/ERK signaling pathway has likely several other downstream targets in addition to Aurora B.

As reported previously, wild-type BRAF melanoma cells are resistant to the cytostatic/cytotoxic effect of vemurafenib, and vemurafenib stimulates the ERK activity, rather than inhibiting it (39, 40). Consistently, an increased level of Aurora B could be observed after 24 h.

Interestingly, we observe that vemurafenib resistance of melanoma cells is accompanied by Aurora B re-expression, which likely drives their return to proliferation. Aberrant PDGF signaling has been previously associated with vemurafenib resistance (41), and our results demonstrate that PDGF increases the Aurora B level. Thus, the PDGF-PDGF receptor β axis could mediate resistance by favoring Aurora B recovery. Dysregulation of other signaling molecules, such as HGF or EGF that enhances the Aurora B level, could also contribute to vemurafenib resistance. More importantly, AZD1152 prevents growth of both BRAFV600E-sensitive and BRAFV600E melanoma cells resistant to vemurafenib. Noteworthy, the AZD1152 effect is slightly but significantly higher in vemurafenib-resistant melanoma cells compared with the sensitive parental cells. Using PARP cleavage as a readout of cell death, similar observations have been made with Aurora B-specific siRNA. These findings are important for the management of BRAFV600E mutant melanomas but also for those that are BRAF wild type. Indeed, there are no efficient cures for non-BRAFV600E-mutated melanomas, which represent half of all the cases. Collectively, our data disclose new therapeutic options for metastatic melanoma, using the targeting of Aurora B.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the C3M imaging core facility (Microscopy and Imaging Platform Côte d'Azur) and the C3M animal room facility.

This work was supported in part by INSERM, the “Fondation de France,” and the “Société Française de Dermatologie.”

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7.

- HQPA

- hydroxyquinazoline pyrazol anilide

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- SA-β-Gal

- senescence-associated β-galactosidase

- AIF

- apoptosis-inducing factor

- HGF

- hepatocyte growth factor

- BRAF

- v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hodi F. S., O'Day S. J., McDermott D. F., Weber R. W., Sosman J. A., Haanen J. B., Gonzalez R., Robert C., Schadendorf D., Hassel J. C., Akerley W., van den Eertwegh A. J., Lutzky J., Lorigan P., Vaubel J. M., Linette G. P., Hogg D., Ottensmeier C. H., Lebbé C., Peschel C., Quirt I., Clark J. I., Wolchok J. D., Weber J. S., Tian J., Yellin M. J., Nichol G. M., Hoos A., Urba W. J. (2010) Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 711–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davies H., Bignell G. R., Cox C., Stephens P., Edkins S., Clegg S., Teague J., Woffendin H., Garnett M. J., Bottomley W., Davis N., Dicks E., Ewing R., Floyd Y., Gray K., Hall S., Hawes R., Hughes J., Kosmidou V., Menzies A., Mould C., Parker A., Stevens C., Watt S., Hooper S., Wilson R., Jayatilake H., Gusterson B. A., Cooper C., Shipley J., Hargrave D., Pritchard-Jones K., Maitland N., Chenevix-Trench G., Riggins G. J., Bigner D. D., Palmieri G., Cossu A., Flanagan A., Nicholson A., Ho J. W., Leung S. Y., Yuen S. T., Weber B. L., Seigler H. F., Darrow T. L., Paterson H., Marais R., Marshall C. J., Wooster R., Stratton M. R., Futreal P. A. (2002) Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 417, 949–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chapman P. B., Hauschild A., Robert C., Haanen J. B., Ascierto P., Larkin J., Dummer R., Garbe C., Testori A., Maio M., Hogg D., Lorigan P., Lebbe C., Jouary T., Schadendorf D., Ribas A., O'Day S. J., Sosman J. A., Kirkwood J. M., Eggermont A. M., Dreno B., Nolop K., Li J., Nelson B., Hou J., Lee R. J., Flaherty K. T., McArthur G. A. (2011) Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2507–2516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ruchaud S., Carmena M., Earnshaw W. C. (2007) Chromosomal passengers. Conducting cell division. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 798–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pirker C., Lötsch D., Spiegl-Kreinecker S., Jantscher F., Sutterlüty H., Micksche M., Grusch M., Berger W. (2010) Response of experimental malignant melanoma models to the pan-Aurora kinase inhibitor VE-465. Exp. Dermatol. 19, 1040–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang X., Moschos S. J., Becker D. (2010) Functional analysis and molecular targeting of aurora kinases A and B in advanced melanoma. Genes Cancer 1, 952–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kurai M., Shiozawa T., Shih H. C., Miyamoto T., Feng Y. Z., Kashima H., Suzuki A., Konishi I. (2005) Expression of Aurora kinases A and B in normal, hyperplastic, and malignant human endometrium. Aurora B as a predictor for poor prognosis in endometrial carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 36, 1281–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin Z. Z., Jeng Y. M., Hu F. C., Pan H. W., Tsao H. W., Lai P. L., Lee P. H., Cheng A. L., Hsu H. C. (2010) Significance of Aurora B overexpression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Aurora B overexpression in HCC. BMC Cancer 10, 461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jani J. P., Arcari J., Bernardo V., Bhattacharya S. K., Briere D., Cohen B. D., Coleman K., Christensen J. G., Emerson E. O., Jakowski A., Hook K., Los G., Moyer J. D., Pruimboom-Brees I., Pustilnik L., Rossi A. M., Steyn S. J., Su C., Tsaparikos K., Wishka D., Yoon K., Jakubczak J. L. (2010) PF-03814735, an orally bioavailable small molecule aurora kinase inhibitor for cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 9, 883–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tao Y., Leteur C., Calderaro J., Girdler F., Zhang P., Frascogna V., Varna M., Opolon P., Castedo M., Bourhis J., Kroemer G., Deutsch E. (2009) The aurora B kinase inhibitor AZD1152 sensitizes cancer cells to fractionated irradiation and induces mitotic catastrophe. Cell Cycle 8, 3172–3181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mortlock A. A., Foote K. M., Heron N. M., Jung F. H., Pasquet G., Lohmann J. J., Warin N., Renaud F., De Savi C., Roberts N. J., Johnson T., Dousson C. B., Hill G. B., Perkins D., Hatter G., Wilkinson R. W., Wedge S. R., Heaton S. P., Odedra R., Keen N. J., Crafter C., Brown E., Thompson K., Brightwell S., Khatri L., Brady M. C., Kearney S., McKillop D., Rhead S., Parry T., Green S. (2007) Discovery, synthesis, and in vivo activity of a new class of pyrazoloquinazolines as selective inhibitors of aurora B kinase. J. Med. Chem. 50, 2213–2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Larribere L., Khaled M., Tartare-Deckert S., Busca R., Luciano F., Bille K., Valony G., Eychene A., Auberger P., Ortonne J. P., Ballotti R., Bertolotto C. (2004) PI3K mediates protection against TRAIL-induced apoptosis in primary human melanocytes. Cell Death Differ. 11, 1084–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robert G., Gaggioli C., Bailet O., Chavey C., Abbe P., Aberdam E., Sabatié E., Cano A., Garcia de Herreros A., Ballotti R., Tartare-Deckert S. (2006) SPARC represses E-cadherin and induces mesenchymal transition during melanoma development. Cancer Res. 66, 7516–7523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giuliano S., Cheli Y., Ohanna M., Bonet C., Beuret L., Bille K., Loubat A., Hofman V., Hofman P., Ponzio G., Bahadoran P., Ballotti R., Bertolotto C. (2010) Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor controls the DNA damage response and a lineage-specific senescence program in melanomas. Cancer Res. 70, 3813–3822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hauf S., Cole R. W., LaTerra S., Zimmer C., Schnapp G., Walter R., Heckel A., van Meel J., Rieder C. L., Peters J. M. (2003) The small molecule Hesperadin reveals a role for Aurora B in correcting kinetochore-microtubule attachment and in maintaining the spindle assembly checkpoint. J. Cell Biol. 161, 281–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Larribere L., Hilmi C., Khaled M., Gaggioli C., Bille K., Auberger P., Ortonne J. P., Ballotti R., Bertolotto C. (2005) The cleavage of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor, MITF, by caspases plays an essential role in melanocyte and melanoma cell apoptosis. Genes Dev. 19, 1980–1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ohanna M., Giuliano S., Bonet C., Imbert V., Hofman V., Zangari J., Bille K., Robert C., Bressac-de Paillerets B., Hofman P., Rocchi S., Peyron J. F., Lacour J. P., Ballotti R., Bertolotto C. (2011) Senescent cells develop a PARP-1 and nuclear factor-κB-associated secretome (PNAS). Genes Dev. 25, 1245–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yasui Y., Urano T., Kawajiri A., Nagata K., Tatsuka M., Saya H., Furukawa K., Takahashi T., Izawa I., Inagaki M. (2004) Autophosphorylation of a newly identified site of Aurora-B is indispensable for cytokinesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12997–13003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song L., Li D., Liu R., Zhou H., Chen J., Huang X. (2007) Ser-10 phosphorylated histone H3 is involved in cytokinesis as a chromosomal passenger. Cell Biol. Int. 31, 1184–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gully C. P., Zhang F., Chen J., Yeung J. A., Velazquez-Torres G., Wang E., Yeung S. C., Lee M. H. (2010) Antineoplastic effects of an Aurora B kinase inhibitor in breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 9, 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Castedo M., Perfettini J. L., Roumier T., Andreau K., Medema R., Kroemer G. (2004) Cell death by mitotic catastrophe. A molecular definition. Oncogene 23, 2825–2837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cui Y., Borysova M. K., Johnson J. O., Guadagno T. M. (2010) Oncogenic B-Raf(V600E) induces spindle abnormalities, supernumerary centrosomes, and aneuploidy in human melanocytic cells. Cancer Res. 70, 675–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cui Y., Guadagno T. M. (2008) B-Raf(V600E) signaling deregulates the mitotic spindle checkpoint through stabilizing Mps1 levels in melanoma cells. Oncogene 27, 3122–3133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang I. C., Chen Y. J., Hughes D., Petrovic V., Major M. L., Park H. J., Tan Y., Ackerson T., Costa R. H. (2005) Forkhead box M1 regulates the transcriptional network of genes essential for mitotic progression and genes encoding the SCF (Skp2-Cks1) ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 10875–10894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Paraiso K. H., Xiang Y., Rebecca V. W., Abel E. V., Chen Y. A., Munko A. C., Wood E., Fedorenko I. V., Sondak V. K., Anderson A. R., Ribas A., Palma M. D., Nathanson K. L., Koomen J. M., Messina J. L., Smalley K. S. (2011) PTEN loss confers BRAF inhibitor resistance to melanoma cells through the suppression of BIM expression. Cancer Res. 71, 2750–2760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kimura M., Uchida C., Takano Y., Kitagawa M., Okano Y. (2004) Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the human aurora B promoter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 316, 930–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tomonaga T., Nomura F. (2007) Chromosome instability and kinetochore dysfunction. Histol. Histopathol. 22, 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arbitrario J. P., Belmont B. J., Evanchik M. J., Flanagan W. M., Fucini R. V., Hansen S. K., Harris S. O., Hashash A., Hoch U., Hogan J. N., Howlett A. R., Jacobs J. W., Lam J. W., Ritchie S. C., Romanowski M. J., Silverman J. A., Stockett D. E., Teague J. N., Zimmerman K. M., Taverna P. (2010) SNS-314, a pan-Aurora kinase inhibitor, shows potent anti-tumor activity and dosing flexibility in vivo. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 65, 707–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dhillon N. K., Mudryj M. (2003) Cyclin E overexpression enhances cytokine-mediated apoptosis in MCF7 breast cancer cells. Genes Immun. 4, 336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vader G., Kauw J. J., Medema R. H., Lens S. M. (2006) Survivin mediates targeting of the chromosomal passenger complex to the centromere and midbody. EMBO Rep. 7, 85–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mackay A. M., Ainsztein A. M., Eckley D. M., Earnshaw W. C. (1998) A dominant mutant of inner centromere protein (INCENP), a chromosomal protein, disrupts prometaphase congression and cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 140, 991–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yamanaka Y., Heike T., Kumada T., Shibata M., Takaoka Y., Kitano A., Shiraishi K., Kato T., Nagato M., Okawa K., Furushima K., Nakao K., Nakamura Y., Taketo M. M., Aizawa S., Nakahata T. (2008) Loss of Borealin/DasraB leads to defective cell proliferation, p53 accumulation, and early embryonic lethality. Mech. Dev. 125, 441–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma R. Y., Tong T. H., Cheung A. M., Tsang A. C., Leung W. Y., Yao K. M. (2005) Raf/MEK/MAPK signaling stimulates the nuclear translocation and transactivating activity of FOXM1c. J. Cell Sci. 118, 795–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wakahara K., Ohno T., Kimura M., Masuda T., Nozawa S., Dohjima T., Yamamoto T., Nagano A., Kawai G., Matsuhashi A., Saitoh M., Takigami I., Okano Y., Shimizu K. (2008) EWS-Fli1 up-regulates expression of the Aurora A and Aurora B kinases. Mol. Cancer Res. 6, 1937–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Beuret L., Flori E., Denoyelle C., Bille K., Busca R., Picardo M., Bertolotto C., Ballotti R. (2007) Up-regulation of MET expression by α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone and MITF allows hepatocyte growth factor to protect melanocytes and melanoma cells from apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14140–14147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boone B., Jacobs K., Ferdinande L., Taildeman J., Lambert J., Peeters M., Bracke M., Pauwels P., Brochez L. (2011) EGFR in melanoma. Clinical significance and potential therapeutic target. J. Cutan. Pathol. 38, 492–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Otsuka T., Takayama H., Sharp R., Celli G., LaRochelle W. J., Bottaro D. P., Ellmore N., Vieira W., Owens J. W., Anver M., Merlino G. (1998) c-Met autocrine activation induces development of malignant melanoma and acquisition of the metastatic phenotype. Cancer Res. 58, 5157–5167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Factor V. M., Seo D., Ishikawa T., Kaposi-Novak P., Marquardt J. U., Andersen J. B., Conner E. A., Thorgeirsson S. S. (2010) Loss of c-Met disrupts gene expression program required for G2/M progression during liver regeneration in mice. PLoS One 5, pii: e12739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hatzivassiliou G., Song K., Yen I., Brandhuber B. J., Anderson D. J., Alvarado R., Ludlam M. J., Stokoe D., Gloor S. L., Vigers G., Morales T., Aliagas I., Liu B., Sideris S., Hoeflich K. P., Jaiswal B. S., Seshagiri S., Koeppen H., Belvin M., Friedman L. S., Malek S. (2010) RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature 464, 431–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Poulikakos P. I., Zhang C., Bollag G., Shokat K. M., Rosen N. (2010) RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signaling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature 464, 427–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nazarian R., Shi H., Wang Q., Kong X., Koya R. C., Lee H., Chen Z., Lee M. K., Attar N., Sazegar H., Chodon T., Nelson S. F., McArthur G., Sosman J. A., Ribas A., Lo R. S. (2010) Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS up-regulation. Nature 468, 973–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.