Abstract

Systemic candidiasis is a fungal infection which coupled with solid malignancies places patients at high risk of succumbing to the disease. Few studies have shown evidence of the relationship between systemic candidiasis and malignancy-induced immunosuppression disease especially in breast cancer. At present, animal studies that exclusively demonstrate this relationship have yet to be conducted. The exact causative mechanism of systemic candidiasis is currently under much speculation. This study therefore aimed to demonstrate this relationship by observing the histopathological changes of organs harvested from female Balb/c mice which were experimentally induced with breast cancer and inoculated with systemic candidiasis. The mice were randomly assigned to five different groups (n=12). The first group (group 1) was injected with phosphate buffer solution, the second (group 2) with systemic candidiasis, the third (group 3) with breast cancer and the final two groups (groups 4 and 5) had both candidiasis and breast cancer at two different doses of candidiasis, respectively. Inoculation of mice with systemic candidiasis was performed by an intravenous injection of Candida albicans via the tail vein following successful culture methods. Induction of mice with breast cancer occurred via injection of 4T1 cancer cells at the right axillary mammary fatpad after effective culture methods. The prepared slides with organ tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acidic schiff and gomori methenamine silver stains for a histopathological analysis. Grading of primary tumour and identification of metastatic deposits, as well as scoring of inflammation and congestion in all the respective organs was conducted. Statistical tests performed to compare groups 2 and 4 showed that group 4 exhibited a highly statistically significant increase in organ inflammation and congestion (p<0.01). The median severity of candidiasis in the kidneys and liver also increased in group 4 as compared to group 2. In conclusion, based on the above evidence, systemic candidiasis significantly increased in mice with breast cancer.

Keywords: systemic candidiasis, breast cancer, Candida albicans, 4T1 mouse cancer model, metastasis, immunosuppression

Introduction

Candidiasis is a disease caused by Candida sp which are part of the normal flora found in the upper respiratory, gastrointestinal and female genital tract of the human body. Most cases of Candida infection result from Candida albicans, which is an opportunistic infection as it does not induce disease in immunocompetent individuals but can only do so in those with an impaired host immune defence system. The Candida infection is generally classified into superficial and deep. It commonly infects the nails, skin and mucous membranes, especially the oropharynx, vagina, oesophagus and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Occasionally, Candida sp invade the bloodstream and spread to other deep structure organs in the body such as kidneys, lungs and brain, causing systemic candidiasis (1).

Although a decrease in bloodstream infection has been noted, the number of risk factors which may eventually lead to systemic candidiasis have been on the increase (2). Risk factors for systemic candidiasis include immunosuppression due to chemotherapy or corticosteroid therapy, diabetes mellitus, low birth weight in neonates, broad spectrum antibiotics, long-term catheterization, haemodialysis and parenteral nutrition. However, a significant observation was that the three main groups of patients associated with systemic candidiasis are those with neutropenic cancer, organ or stem cell transplant patients and those undergoing intensive care procedures.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among Malaysian women, with approximately 1 in 20 developing breast cancer in their lifetime (3). There is a marked geographical difference in the worldwide incidence of breast cancer, with a higher incidence in developed countries compared to developing countries. In a survey conducted in two prominent hospitals in Malaysia, the age incidence was similar. Moreover, it was discovered that on average, half of the cases were delayed in presentation. This delay was possibly attributed to a strong belief in traditional medicine, the negative perception of the disease, poverty and poor education, coupled with fear and denial (3,4).

While the exact mechanism leading to systemic candidiasis is not known, the initiation and progression of systemic candidiasis can be viewed as an imbalance in the host-pathogen relationship in favour of Candida albicans. Previous studies showed that invasive candidiasis is a common and serious complication of cancer and its therapy (5). In cancer patients, it has been hypothesized that it develops from initial GI colonization with subsequent translocation into the bloodstream. It is unclear what components of the innate immune system are necessary for the prevention of Candida albicans dissemination from the GI tract, but it is hypothesized that neutropenia and GI mucosal damage are critical in allowing widespread invasive Candida albicans disease (6).

Few studies have documented the co-existence and plausible relationship between breast cancer and systemic candidiasis (7–10). However, there have been no authentic studies on systemic candidiasis and its relationship with breast cancer in experimentally induced mice. This study aimed to establish a hypothetical relationship between the most common type of cancer in women in Malaysia and systemic candidiasis by using a mouse breast cancer model with Candida inoculation. Results from this study will provide the groundwork from which further studies, such as immunology, can be carried out to better understand the pathogenesis of Candida in cancer patients. It may also help bring better insight into the current treatment and pathophysiology of cancer which has itself been shown to be a risk factor to the predisposition of candidiasis.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Female Balb/c mice were used for the investigation, after prior approval from the Ethics committee. The mice were divided into five groups (Table I). Dosing began when the mice were 10 weeks old and weighed 15–25 g. They were housed in groups of 6 mice for each metal cage located within the Animal Housing Facility in the International Medical University. The mice were fed with standard mice chow and were given free access to water. The weight of the mice was recorded at the start, once every week thereafter and finally at the end of the experiment.

Table I.

Characteristics of the five groups.

| Group no. | Group description | Concentration per dose of 0.1 ml (cells/ml) | Duration before dissection (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control group (injected with PBS only) | - | 2 |

| 2 | Mice inoculated with Candida albicans | 5×106 | 2 |

| 3 | Mice induced with breast cancer | 1×105 | 4 |

| 4 | Mice induced with breast cancer and subsequently inoculated with Candida albicans | 1×105 of 4T1 breast cancer cells and 5×106 for Candida albicans | 3 + 1 |

| 5 | Mice induced with breast cancer and subsequently inoculated and with Candida albicans | 1×105 of 4T1 breast cancer cells 5×108 for Candida albicans | 3 + 1 |

Culture of Candida yeast cells

The Candida yeast cells were obtained from patient clinical isolates (International Medical University Research Lab, Wong et al). Samples were used after permission was obtained from the investigator. The cells were then subcultured onto a solid media of Sabouraud agar by streaking methods and stored in an incubator at 37°C. Before harvesting the colonies for inoculation, one of the Candida colonies was subcultured in the YPD broth and left for 72 h in a shaking incubator (Certomat S11) fixed at 100 rpm at a controlled temperature of 37°C. After 3 days or on the stipulated day of inoculation, serum was added into the broth to allow for germ tube formation to occur and left in the shaking incubator for an additional 3 h with similar settings. The colonies were then harvested by means of centrifugation. The volume and concentration needed for inoculation were prepared by dilutions and calculated using a haemocytometer.

Inoculation of mice with systemic candidiasis

The mice were first placed inside a retainer. A 27G needle syringe was then used to inject 0.1 ml of Candida blastospores suspended in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) at a concentration of 5×106 cells/ml via the tail vein using ethanol swap. This step was repeated with another group of mice at a concentration of 5×108 cells/ml.

Culture of 4T1 breast cancer cells

The breast cancer cells (4T1 cell line; International Medical University Research Lab, Radhakrishnan et al) were maintained and subcultured into a 25-cm3 culture flask until the cells were healthy and had achieved a steady replicative rate. They were then harvested by means of centrifugation and kept suspended in the culture medium. The volume and concentration needed for inoculation was prepared by dilutions and calculated using a haemocytometer.

Inducing mice with 4T1 cancer cells

The mice were first anesthesized with diethyl ether before an injection of 0.1 ml of 1×105 cells/ml was administered subcutaneously into the mammary fatpad at the axilla of the right arm.

Sample collection

The mice were weighed at the end of the experiment before being sacrificed with diethyl ether in a desiccator. The organs harvested were spleen, kidneys, lungs, heart and brain. The tumours from groups 3, 4 and 5 were also harvested. They were subsequently fixed in 10% formalin for at least 2 days.

Tissue processing

The fixed organs were then sectioned and processed to paraffin blocks. Sections of 4 μm were taken on glass slides and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid schiff (PAS) and gomori methenamine silver (GMS). The sections were then dehydrated, cleared and mounted with cover slips using DPX mountant media.

Results

The slides were observed under a light microscope in order to grade the primary tumour, presence of metastatic deposits, and extent of candidiasis in all the organs by comparatively examining both the hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, PAS and GMS, and the extent of organ inflammation and congestion. A correlation was then made between the pathological lesions observed in the groups and the mean gross weight changes.

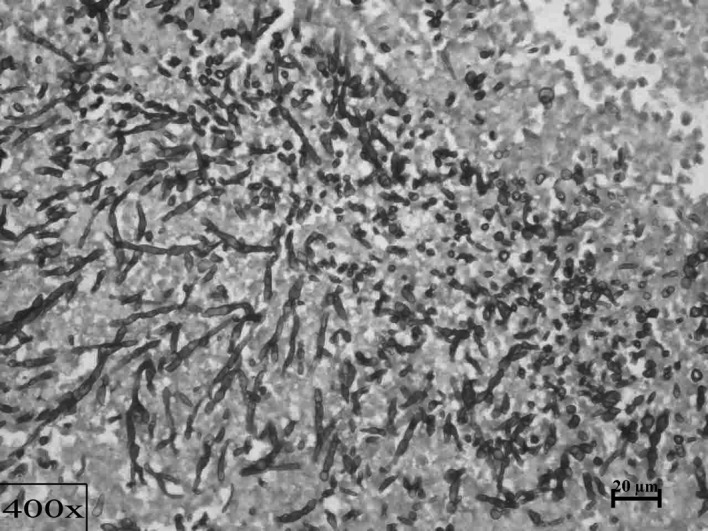

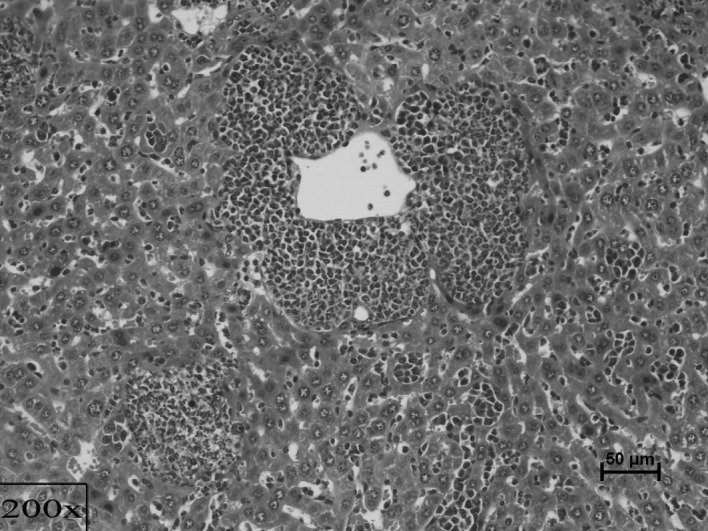

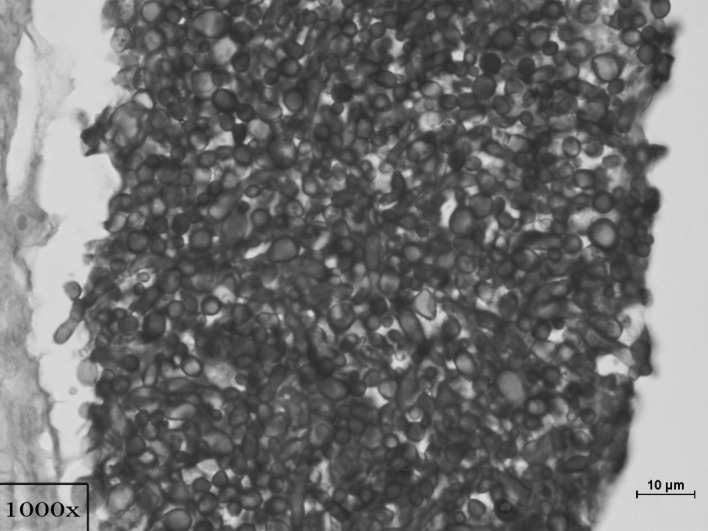

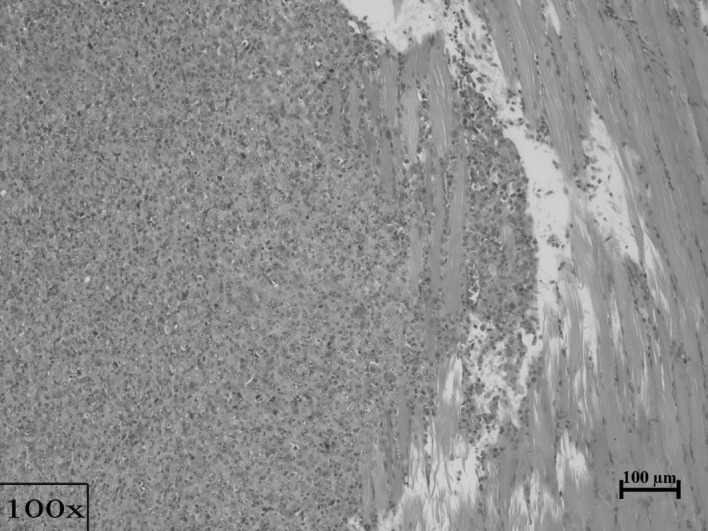

The histopathological scoring of inflammation and congestion changes in these organs was based on the technique employed by Kah Heng et al and Black et al (11,12) (Figs. 3 and 4). Scoring of candidiasis was with reference to Black et al and Balish et al (12,13) (Figs. 2 and 3). Grading of the primary tumour was carried out using the conventional method of analyzing the similarity of the cells to its tissue of origin as poorly, moderately and severely differentiated (14) (Figs. 1 and 4).

Figure 3.

A colony of Candida in the central region of a huge abscess in the liver, surrounded by inflammation (×100, PAS).

Figure 4.

Extensive metastasis of cancer in the liver among micro-abscesses filled with chronic inflammatory cells, Candida and debris (×200, PAS).

Figure 2.

Growth of a large colony of Candida yeast cells and hyphae in the renal parenchyma (×1000, PAS).

Figure 1.

Poorly differentiated breast carcinoma cells with multiple mitotic figures in the primary tumour, extending into chest wall muscle (×100, H&E).

Statistical analysis

In this study, 60 samples were studied and analyzed. Analytical data were expressed as a mean with standard deviation and a 95% confidence interval. The level of significance was set at 0.05. Statistical tests used were: The i) paired t-test for comparison of initial and final mean weight of mice in each group, ii) Kruskal-Wallis test for global comparison of groups for all the parameters, iii) non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between two groups for each parameter and iv) Spearman’s rho test for the correlation of candidiasis, cancer metastases, inflammation and congestion.

The statistical tests were conducted with the aid of SPSS Statistical software version 16. For the individual tests, p<0.05 was considered to be significant. The paired t-test is a parametric method employed to test for any significant difference between the means on the same or related subject over time or in differing circumstances. From the test conducted, it was found that p<0.05 in all the groups, with groups 1, 2 and 3 showing p<0.01. Thus, a significant difference in the weight of the mice in all the groups at the beginning and the end of the experiment was noted (Table II).

Table II.

Results of the paired t-test for gross weight of mice at the beginning and end of the experiment.

| Group | Mean initial weight (g) | Mean final weight (g) | Asymptote significance (p<0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17.71 | 19.09 | 0.001b |

| 2 | 18.36 | 16.85 | 0.009b |

| 3 | 19.00 | 20.00 | 0.000b |

| 4 | 19.40 | 18.01 | 0.039a |

| 5 | 20.25 | 18.04 | 0.032a |

The mean gross weight in grams, noted at the beginning and end of the experiment, was included.

Significant difference at p<0.05 and

p<0.01.

Based on a global comparison for metastasis in each of the organs for all groups, the Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups 3 and 4 showed a significant difference in all the organs except the brain (p<0.01; Table III). The kidneys showed a greater level of significance (p<0.01) as compared to the other organs. This shows that the presence of candidiasis, as in the case of group 4, has an effect on the extent of the metastatic growth in these organs.

Table III.

Results obtained from the Kruskal-Wallis test for global comparison of organ metastases among the groups and the Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups 3 and 4 for the extent of organ metastases.

| Organs | Asymptote significance (p<0.05) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Kruskal-Wallis test of global comparison | Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups 3 and 4 | |

| Brain | 1.000 | - |

| Kidneys | 0.000b | 0.000b |

| Lungs | 0.000b | 0.016a |

| Liver | 0.000b | 0.015a |

| Spleen | 0.000b | 0.016a |

Significant difference at p<0.05 and

p<0.01.

By comparing the median severity of candidiasis between groups 2 and 4, a significant difference in severity was observed in the kidneys and liver. In the kidneys of group 2, the severity of candidiasis was mild, while that in group 4 was moderate (Table IV). These observations were also observed in slides stained in PAS and GMS.

Table IV.

Histopathological scoring of candidiasis in hematoxylin and eosin.

| Experimental group | Median of severity of candidiasis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Brain | Kidneys | Lungs | Liver | |

| Group 2- | ||||

| Mice with Candida (5×106 cells/ml) | − | + | − | − |

| Group 4- | ||||

| Mice with breast cancer and Candida (5×106 cells/ml) | − | ++ | − | ++ |

Absent (−), mild (+), moderate (++) and severe (+++).

The Kruskal-Wallis test used for global comparison between groups 2 and 4, and 4 and 5 for inflammation and congestion showed a significant difference of p<0.01 in all the organs (Tables V and VI). The Mann-Whitney U test used for comparison between groups 2 and 4 for inflammation response showed a significant difference in all the organs. This shows that the co-existence of both candidiasis and cancer in the mice had a heightened effect on the severity of inflammation as compared to mice with candidiasis alone.

Table V.

Results of Kruskal-Wallis for global comparison among groups and Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups 2 and 4 for organ inflammation response.

| Organs | Asymptote significance (p<0.05) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Kruskal-Wallis test of global comparison | Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups 2 and 4 | |

| Brain | 0.000b | 0.000b |

| Kidneys | 0.000b | 0.005b |

| Lungs | 0.000b | 0.000b |

| Liver | 0.000b | 0.000b |

Significant difference at p<0.05 and

p<0.01.

Table VI.

Results of Kruskal-Wallis for global comparison among groups and Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups 4 and 5 for organ congestion.

| Organs | Asymptote significance (p<0.05) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Kruskal-Wallis test of global comparison | Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups 4 and 5 | |

| Brain | 0.000b | 0.000b |

| Kidneys | 0.000b | 0.000b |

| Lungs | 0.000b | 0.006b |

| Liver | 0.000b | 0.000b |

Significant difference at p<0.05 and

p<0.01.

The Mann-Whitney test was used for comparison between groups 4 and 5 to examine the extent of candidiasis. The findings showed that the increase in the Candida dosage injected into group 5 at a concentration of 5×108 cells/ml compared to 5×106 cells/ml in group 4, showed a statistically significant difference in the brain and lungs (p<0.01; Table VII). The Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups 4 and 5 for inflammation and congestion showed a significant difference in the inflammatory response at the liver with p<0.01. This means that the increased dose in group 5 showed a statistically significant effect on the inflammatory response noted in the liver and congestion observed in the brain and the lungs.

Table VII.

Results of hte Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups 4 and 5 for the extent of candidiasis, organ inflammation and organ congestion.

| Organs | Asymptote significance (p<0.05) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Extent of candidiasis | Organ inflammation | Organ congestion | |

| Brain | 0.000b | 0.070 | 0.004b |

| Kidneys | 0.308 | 0.265 | 0.229 |

| Lungs | 0.000b | 0.314 | 0.013a |

| Liver | 0.808 | 0.000b | 1.000 |

Significant difference at p<0.05 and

p<0.01.

The correlation between candidiasis and cancer metastases was positive in the kidneys and liver for a significance level of 0.01 (Table VIII). However, no correlation was found in the brain, while in the lungs the correlation was not significant. The correlation between candidiasis and inflammation was shown to be positively correlated with significance at a level of 0.01 in the kidneys, lungs and liver, while the brain only showed significance at a level of 0.05. The correlation between candidiasis and congestion was positive at a significance level of 0.01 in all of the organs.

Table VIII.

Correlation coefficient between candidiasis with cancer metastases, organ inflammation and organ congestion.

| Comparison organs | Spearman rho correlation coefficient between candidiasis and cancer metastases | Spearman rho correlation coefficient between candidiasis and organ inflammation | Spearman rho correlation coefficient between candidiasis and organ congestion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | 0 (no correlation) | 0.272a | 0.553b |

| Kidneys | 0.347b | 0.619b | 0.537b |

| Lungs | 0.212 | 0.587b | 0.544b |

| Liver | 0.485b | 0.614b | 0.616b |

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 (2-tailed) and

0.01 levels (2-tailed).

Discussion

Few studies have been conducted on experimental systemic candidiasis in mice. Information obtained from these studies on the necessary dosages, as well as previous observations were used to make comparisons with this study (15–17). Some of these studies have been dedicated to the observations of the correlation between systemic candidiasis and other forms of immunosuppression such as chemotherapy, steroid therapy, antibiotic therapy, as well as other types of malignancies such as leukemia and esophageal cancer.

However, an exclusive study on systemic candidiasis and its relationship with breast cancer has yet to be conducted, even though there are a few epidemiological studies that have shown a co-existence of breast cancer and systemic candidiasis in humans (7,10,18). This study aimed to focus on the relationship between systemic candidiasis and breast cancer by examining the behaviour of candidiasis when the body is subjected to a chronic disease state. Therefore, breast cancer was not only selected as an ideal representation of a chronic illness, but also one that is capable of suppressing the host immune system (19–22).

To study how the presence of a chronic illness such as breast cancer can, by itself, be attributed to the increased severity of candidiasis, this novel study focused on the growth of systemic candidiasis following the induction of mice with breast cancer. Scores were calculated based on the severity of candidiasis and grading of the primary tumour, and identification of their metastatic deposits was conducted. Other parameters taken into consideration included gross weight of the mice at the beginning and end of the study, as well as inflammation and congestion in the respective organs which were studied by scoring on a semi-quantitative scale using an established technique as mentioned earlier.

Systemic candidiasis

In group 2, the mice were solely inoculated with systemic candidiasis by intravenous injection via the tail vein for a duration of two weeks. During the course of the experiment, signs of the disease were noted in these mice. Their eyeballs protruded, their fur roughened and they were generally less active as compared to the normal group. Moreover, increased group huddle and sleep were noted. The mice also appeared very weak and thin with the curvatures of the bony structures beneath the mice visible to the naked eye. In addition, the weight taken at the beginning and end of the experiment showed that there was a statistically significant reduction in their mean weight. This was attributed to the possible loss of appetite and general cachexic state of the mice. Histopathologically, favourable growth of the Candida colonies in the form of hyphae, yeast cells and pseudohyphae were discovered in the kidneys, pelvis and tubule region, but not in many of the other organs. This was attributed to the mild dose of 5×106 cells/ml Candida cells injected and the short duration of the experiment as also shown by Wong et al (16).

Breast cancer study

In group 3, the mice were injected at the mammary fatpad with 4T1 cancer cells in the right axilla region at a concentration of 1×106 cells/ml (23). After four weeks of growth and metastases, the mice were sacrificed for analysis. During the course of the investigation, the weights of the mice were reduced for the first week before gradually increasing in the 3rd week. The growth of the primary tumour was detected as a palpable mass as early as the 10th day and as late as the 14th day. The mice were generally active for the first two weeks with no apparent deviations from those usually observed in the normal control group. However, by the 3rd week, the mice began to exhibit signs of lethargy and did not move as often. Furthermore, the mass of tumour began to appear significantly enlarged to the naked eye by the middle of 3rd week. General appetite was good. No distinct changes to the fur, eyes or prominent curvatures of the bony structures were noted.

Grading for the primary tumour showed it to be moderate to poorly differentiated with the majority of the tumours being poorly differentiated. Metastatic deposits were discovered in the lungs, liver and spleen with varying frequencies among the mice. The gross morphology of the other organs did not exhibit any crude changes, with the exception of the spleen which was markedly enlarged as compared to that found in the normal group. The tumour appeared hard and smooth in texture with a glistening surface.

Scoring for inflammation showed that the median of severity of the entire group was mild in both the lungs and liver. The median severity of congestion found in the kidneys, lungs and liver were mild, while congestion found in the brain was mild to moderate. In the liver, however, the micro-abscesses that were observable in group 2, were not noted in the group as a whole. Therefore, in the group with breast cancer, the severity of inflammation and congestion observed in the organs were mostly mild in severity with metastatic deposits found in the lungs, liver and spleen.

Correlation between systemic candidiasis and breast cancer

In group 4, the mice were first induced with breast cancer for three weeks and subsequently inoculated with Candida at a concentration of 5×106 cells/ml for one week. The time of induction with breast cancer was set at three weeks, based on studies showing that by this period, adequate metastases have occurred in all these organs (23,24). The initial stages of tumour growth and changes in the mice were similar to those found in group 3. However, when Candida was injected, changes in group 2 were noted within days instead of the 2nd week as in the case of group 2. These changes included protruding eyes, roughened fur and general inertia, with increased huddle and sleep. In the final stages of the investigation, a surge in the growth of tumour size was observed.

Grading carried out for the primary tumour showed poorly differentiated tissue with atypical cells and a high number of mitotic figures. Metastatic deposits were also found in the lungs, liver, spleen and even in the kidneys at a higher frequency as compared to that of group 3. These differences were statistically significant (p<0.05). Thus, an increased frequency of metastatic deposits occurred in these organs in group 4 as compared to that in group 3. This suggests a possible role of Candida causing immunosuppression which, by itself, attributed to the increased metastatic deposits of the cancer found in these organs. It also explains the late surge in tumour growth noted late in the investigation.

Notable changes in the kidneys include candidiasis involvement in the renal parenchyma, renal tubules and pelvis. Within the liver parenchyma and vasculature, distinct changes such as micro-abcesses, chronic inflammation and congestion were observed at a greater level in this group as compared to that noted in group 2. This group also showed an increased group median of severity in Candida infection in the kidneys and liver. The kidneys showed a moderate severity as compared to a mild one in group 2, while the liver showed a moderate severity of candidiasis as compared to the absence of candidiasis noted in group 2. Thus, this group showed extra involvement of the liver compared to only the kidneys as was the case in group 2. This observation holds true in scoring performed for both PAS and GMS.

Scoring of inflammation showed a moderate severity as noted in the brain, kidneys and lungs, while the liver showed severe changes as compared to only mild ones found in all the organs in group 2. Comparison of inflammation severity between the two groups was statistically significant (p<0.01).

As for congestion, group 4 showed a moderate congestion in the brain and kidneys as compared to a mild one in group 2 and while congestion in the lungs was not observed in group 2, group 4 showed mild congestion. Furthermore, the liver showed severe congestion as compared to just moderate congestion found in group 2. A comparison between groups 2 and 4 for congestion was statistically significant (p<0.05). In conclusion, severity of candidiasis, inflammation and congestion were found at greater levels in breast cancer induced mice with candidiasis as compared to mice with only candidiasis.

Dose-dependent study

In group 5, the mice were first induced with breast cancer and, subsequently, with candidiasis at a higher dose of 5×108 cells/ml. These mice were similar to group 3 at the initial stages of cancer growth. However, when candidiasis was injected, the mice died within the first week of inoculation at varied periods as compared to group 4 where the time of inoculation with candidiasis was one week and mice survived till the end of investigation. The sudden immediate death was attributed to septicaemia.

Grading on the primary tumour showed the tumours to be poorly differentiated. Metastatic deposits were found in the kidneys, lungs, liver and spleen. Scoring of candidiasis showed mild severity in the brain while the kidneys showed moderate and the lungs severe candidiasis. The liver, on the other hand, showed mild to moderate severity. Statistical tests comparing differences in candidiasis severity between groups 4 and 5 found a significant difference in the brain and lungs (p<0.01). This means that with an increased dose, the brain and lungs exhibit candidiasis with increased levels of severity. It is possible that with a higher dose, the higher reaches of the body are more easily accessed as the amount of dose eliminated by the liver or spleen is less.

In the scoring for inflammation, the brain showed mild severity while the kidneys, lungs and liver showed moderate severity. However, only the liver showed a statistically significant difference when compared to group 4. Inflammation was much less in severity compared to that in group 4, which may be attributed to the short period of inoculation time before the demise of the mice resulting in inadequate time for chronic inflammation to occur.

In the scoring for congestion, group 5 showed severe congestion in all the organs. However, only the brain and the lungs showed a statistically significant difference with group 4, which was shown to have a greater level of congestion. This may be attributed to the acute changes noted in the host response to a foreign pathogen.

Correlation of candidiasis, cancer metastases, organ inflammation and organ congestion

The correlation between candidiasis and cancer metastases was found to be significant in the kidneys and liver (p<0.01). This shows that in the kidneys and liver, an increase in cancer metastatic deposits was accompanied by an increase in candidiasis severity. When correlating candidiasis with inflammation and congestion, it was found to be statistically significant (p<0.05) in all the organs. Thus, increased levels of candidiasis are accompanied by increased levels of inflammation and congestion in the respective organs studied.

In conclusion, the mouse model of inducing breast cancer was successful, as well as the method and technique of inducing candidiasis was effective. The mouse model and method and technique were attributed to the efficient culture methods. Moreover, growth of breast cancer and candidiasis were observable in all the relevant groups. The weight of the mice was also correlated with the pathology suffered by the mice. All the objectives were carried out with precision and successfully achieved.

An analysis was performed based on the scoring of candidiasis, grading of metastatic deposits, inflammation and congestion in the brain, kidneys, lungs and liver of the mice in all the groups. The inflammation and congestion parameters showed a statistically significant increase in severity in all the organs as compared to the group of mice with systemic candidiasis and breast cancer, and that of systemic candidiasis alone. The median severity of the entire group for candidiasis scoring in the kidneys and liver also increased for the group of mice with systemic candidiasis and breast cancer.

Therefore, based on these evidences, systemic candidiasis appears to be more severe in experimentally induced mice with breast cancer than in mice without.

Acknowledgements

This investigation was funded by research grant no. BMS I-02/2008 (12) from the International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

References

- 1.Levinson W. Review of Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 9th edition. The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2006. pp. 134–136. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson MD. Changing patterns and trends in systemic fungal infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(Suppl 1):5–11. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yip CH, Taib NA, Mohamed I. Epidemiology of breast cancer in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006;7:369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hisham AN, Yip CH. Overview of breast cancer in Malaysian women: a problem with late diagnosis. Asian J Surg. 2004;27:130–133. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiNubile MJ, Hille D, Sable CA, Kartsonis NA. Invasive candidiasis in cancer patients: observations from a randomized clinical trial. J Infect. 2005;50:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh AY, Kohler JR, Coggshall KT, van Rooijen N, Pier GB. Mucosal damage and neutropenia are required for candida albicans dissemination. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4:35–38. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottfredsson M, Vredenburgh JJ, Xu J, Schell WA, Perfect JR. Candidemia in women with breast carcinoma treated with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation. Cancer. 2003;98:24–30. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghoneum M, Gollapudi S. Phagocytosis of Candida albicans by metastatic and non metastatic human breast cancer cell lines in vitro. Cancer Detect Prev. 2004;28:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson LM, Krotz S, Weitzman SA, Thimmapaya B. Breast cancer-specific expression of the Candida albicans cytosine deaminase gene using a transcriptional targeting approach. Cancer Gene Ther. 2000;7:845–852. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safdar A, Chaturvedi V, Cross EW, Park S, Bernard EM, Armstrong D. Prospective study of Candida species in patients at a comprehensive cancer center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2129–2133. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.7.2129-2133.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee KH, Chen YS, Judson JP, Chakravarthi S, Sim YM, Er HM. The effect of water extracts of Euphorbia hirta on cartilage degeneration in arthritic rats. Malays J Pathol. 2008;30:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black CA, Eyers FM, Russell A, Dunkley ML, Clancy RL, Beagley KW. Increased severity of Candida vaginitis in BALB/c nu/nu mice versus the parent strain is not abrogated by adoptive transfer of T cell enriched lymphocytes. J Reprod Immunol. 1999;45:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(99)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balish E. A URA3 null mutant of Candida albicans (CAI-4) causes oro-oesophageal and gastric candidiasis and is lethal for gnotobiotic, transgenic mice (Tgepsilon26) that are deficient in both natural killer and T cells. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:290–295. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.004846-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar VRSC, Robbins SL. Robbins Basic Pathology. 7th edition. Saunders; 2003. pp. 436–438. [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Repentigny L. Animal models in the analysis of Candida host-pathogen interactions. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong SF, Mak JW, Pook CK. Potential use of a monoclonal antibody for the detection of Candida antigens in an experimental systemic candidiasis model. Hybridoma. 2008;27:361–373. doi: 10.1089/hyb.2008.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashman RB, Papadimitriou JM. Murine candidiasis. Pathogenesis and host responses in genetically distinct inbred mice. Immunol Cell Biol. 1987;65:163–171. doi: 10.1038/icb.1987.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talarmin JP, Boutoille D, Tattevin P, et al. Epidemiology of candidemia: a one-year prospective observational study in the west of France. Med Mal Infect. 2009;4:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandeville R, Lamoureux G, Legault-Poisson S, Poisson R. Biological markers and breast cancer. A multiparametric study II Depressed immune competence. Cancer. 1982;50:1280–1288. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821001)50:7<1280::aid-cncr2820500710>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semiglazov VF, Kondrat’ev VB, Mar’enko AI, L’Vovich EG, Sofronov BN. Immunologic reactivity of breast cancer patients. Vopr Onkol. 1978;24:74–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Contreras Ortiz O, Stoliar A. Immunological changes in human breast cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1988;9:502–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das SN, Khanna NN, Khanna S. A multiparametric observation of immune competence in breast cancer and its correlation with tumour load and prognosis. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1985;14:374–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pulaski BA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Mouse 4T1 breast tumor model. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001;20:2–11. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im2002s39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tao K, Fang M, Alroy J, Sahagian GG. Imagable 4T1 model for the study of late stage breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:228–236. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]