Background: Meizothrombin is a proteinase produced as an intermediate during thrombin formation catalyzed by prothrombinase.

Results: Rapid kinetic studies reveal its slow equilibration between forms with differing function.

Conclusion: Meizothrombin exists in a slow and reversible equilibrium between equally populated zymogen- and proteinase-like states.

Significance: We provide novel insights into its enigmatic properties and its role as an intermediate in prothrombin activation.

Keywords: Blood Coagulation Factors, Prothrombin, Serine Protease, Thrombin, Thrombomodulin

Abstract

Thrombin is produced by the ordered action of prothrombinase on two cleavage sites in prothrombin. Meizothrombin, a proteinase precursor of thrombin, is a singly cleaved species that accumulates abundantly as an intermediate. We now show that covalent linkage of the N-terminal propiece with the proteinase domain in meizothrombin imbues it with exceptionally zymogen-like character. Meizothrombin exists in a slowly reversible equilibrium between two equally populated states, differing by as much as 140-fold in their affinity for active site-directed ligands. The distribution between the two forms, designated zymogen-like and proteinase-like, is affected by Na+, thrombomodulin binding, or active site ligation. In rapid kinetic measurements with prothrombinase, we also show that the zymogen-like form is produced following the initial cleavage reaction and slowly equilibrates with the proteinase-like form in a previously unanticipated rate-limiting step before it can be further cleaved to thrombin. The reversible equilibration of meizothrombin between zymogen- and proteinase-like states provides new insights into its ability to selectively exhibit the anticoagulant function of thrombin and the mechanistic basis for its accumulation during prothrombin activation. Our findings also provide unexpected insights into the regulation of proteinase function and how the formation of meizothrombin may yield a long lived intermediate with an important regulatory role in coagulation.

Introduction

Thrombin is produced in the penultimate reaction of the blood clotting cascade by the proteolytic activation of prothrombin (1, 2). In addition to catalyzing reactions essential for the formation of the thrombus, it also functions as a key regulatory end product. Its activation of factors V and VIII increases flux through the cascade (3). In complex with thrombomodulin (TM),2 it catalyzes protein C activation, thereby also functioning as a negative feedback effector of coagulation (4, 5). Thus, the action of thrombin on a range of protein substrates lies at the heart of the regulated blood clotting response.

Thrombin utilizes two exosites, termed anion-binding exosite 1 (ABE1) and anion-binding exosite 2 (ABE2), distant from the catalytic site to bind its diverse substrates and ligands (6, 7). Protein recognition through ABE1 partially underlies its pan-specific action on a range of protein substrates (7). Fragment 1.2 (F12), which represents ∼50% of the prothrombin molecule and is produced as an activation fragment upon its conversion to thrombin, is an authentic protein ligand for ABE2 (8). Binding of TM to ABE1 permits thrombin to function in the anticoagulant pathway but precludes its action on numerous other substrates (4). This switch in specificity arises in part from competition between TM and procoagulant substrates for binding ABE1 (9). It is also proposed to result from proteinase allostery associated with TM binding (10).

Extensive literature backs a central role for Na+ in regulating thrombin by affecting its partitioning between a “fast” procoagulant form and a “slow” form with anticoagulant function (11, 12). Although changes in the fractional saturation of thrombin with Na+ have been proposed as a predominant mechanism for the allosteric control of thrombin, it is now clear that this is unlikely to represent a physiologically meaningful mechanism for the regulation of enzymic function (13). Nevertheless, mutagenesis studies drawing from studies with Na+ have been successful in yielding a variety of thrombin mutants that selectively exhibit anticoagulant function with impaired ability to act on procoagulant substrates (14). Although initial work in this area proposed that these mutations represent thrombin forms stabilized in the slow form, terminology since has evolved into a discussion of the specific regulated states of thrombin in terms of Na+-free E* and E forms as well as Na+-bound E (15).

A more general framework for the consideration of proteinase allostery and its regulation by ligand binding is based on the finding that thrombin can exist in a reversible equilibrium between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms (13). Ligation at the active site, the Na+ site, and most likely ABE1 favors the proteinase-like states (13, 16). On the other hand, F12 binding to ABE2 has a reciprocal effect by preferentially binding the zymogen-like species (13). Thus, the distribution of thrombin between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms is dictated by the complement of ligands bound to the enzyme (13, 16). The various thrombin mutants with selectively anticoagulant profiles represent variously destabilized forms that are zymogen-like with poor activity toward substrates, such as fibrinogen, that bind with modest affinity to thrombin. Binding of TM, however, rescues protein C activation by driving the destabilized forms to the proteinase-like state. These points summarize how ligand-dependent allostery can be achieved within this framework.

An essential feature of this model lies in the opposing effects of F12 binding to ABE2 in comparison with the binding of ligands to ABE1, the Na+ site, and the active site. However, based on its modest binding affinity, only a relatively small fraction (∼17%) of thrombin is expected to be bound to F12 even at the maximal concentrations of the two species that could be produced in blood (13). Thus, the ability of F12 to favor the zymogen-like species is unlikely to play a prominent regulatory role under physiologically relevant conditions.

The conversion of prothrombin to thrombin results from the essentially sequential action of prothrombinase at Arg320 followed by cleavage at Arg271 in consecutive enzyme-catalyzed reactions (17, 18). Meizothrombin (mIIa), which is produced following the initial cleavage reaction, accumulates abundantly as an intermediate (18). The intermediate is a proteinase that retains covalent linkage between the catalytic domain and the N-terminal F12 region (19). The basis for the altered specificity profile of mIIa relative to thrombin is considered to lie in the fact that it is thrombin-like but retains the ability to bind membranes afforded by the F12 region (19, 20). However, mIIa curiously exhibits an impaired ability to clot fibrinogen but a normal ability to bind TM and participate in protein C activation much as the thrombin mutants selectively engineered as anticoagulants (20).

Concerns related to the functional significance arising from the modest affinity of F12 for ABE2 in thrombin are obviated in the case of mIIa because of covalent linkage between the F12 region and the proteinase domain. Consequently, our prior findings with thrombin suggest that mIIa might be exceptionally zymogen-like provided the covalently linked F12 region makes comparable contacts with ABE2 in the proteinase domain with analogous functional consequences as it does in its reversible interaction with thrombin. In the present study, we investigated this idea and provide new insights into the likely basis for the skewed specificity profile of mIIa as well as the kinetics of prothrombin activation by prothrombinase.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Human plasma used for protein isolation was a generous gift of the Plasmapheresis Unit of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. d-Phenylalanyl-l-proline-l-arginine chloromethyl ketone (FPRck; Calbiochem), dansylarginine-N-(3-ethyl-1,5-pentanediyl)amide (DAPA; Hematologic Technologies), H-d-phenylalanyl-l-pipecolyl-l-arginine-p-nitroanilide (S2238; DiaPharma), Nα-dansyl-(p-guanidino)-phenylalanine-piperidide (I-2581; DiaPharma), and choline chloride (Acros Organics, catalogue number 219770500) were from the indicated suppliers. Concentrations of stock solutions prepared in water were determined using E342M = 8,270 m−1·cm−1 (S2238), E330M = 4,010 m−1·cm−1 (DAPA), and E342M = 4,105 m−1·cm−1 (I-2581). Small unilamellar phospholipid vesicles composed of 75% (w/w) hen egg l-α-phosphatidylcholine and 25% (w/w) porcine brain l-α-phosphatidylserine (Avanti) (PCPS) were prepared and quality-controlled as described (21). Concentrations of PCPS refer to those of monomeric phospholipids determined by oxidation and inorganic phosphate analysis (22). Unless otherwise noted, all measurements were conducted in 20 mm Hepes, 0.15 m NaCl, 0.1% (w/v) polyethylene glycol (Mr = 8,000), 5 mm CaCl2, pH 7.5 (Assay Buffer) at 25 °C.

Proteins

Prothrombin, factor X, and factor V were isolated from human plasma by established procedures (23, 24). Factor Xa and factor Va were purified and quality-controlled following preparative activation of factor X by the purified activator from Russell's viper venom or of factor V by thrombin as described previously (18, 25). Thrombin was purified following preparative activation of prothrombin as described (26). Ecarin was purified from the venom of Echis carinatus pyramidum (Latoxan, France) with minor modifications to described procedures (27). In a final step following high resolution ion exchange chromatography, the sample was subjected to gel filtration using a 1.5 × 48-cm column of Sephacryl S-100 (GE Healthcare). Fractions containing ecarin activity were pooled, concentrated by centrifugal ultrafiltration (Amicon), and stored frozen in aliquots at −80 °C. Recombinant factor V lacking B-domain residues 811–1491 was expressed on a large scale in baby hamster kidney cells and purified as described (28). Cleavage of this material with thrombin and its repurification yielded two-chain Va with the same polypeptide structure as Va produced from plasma factor V (29). The recombinant extracellular domain of thrombomodulin (sTM) was expressed in mammalian cells and purified as described (30). The production and purification of recombinant tick anticoagulant peptide has been described (31). Recombinant prothrombin variants containing Ala in place of catalytic Ser195 (IIA195), Gln in place of Arg271 (IIQ271), and Gln in place of Arg155, Arg271, and Arg284 (IIQQQ) were produced and purified following large scale culturing of stably transformed HEK293 cell lines in serum-free medium containing vitamin K as described (32). In IIA195, numbering is according to chymotrypsinogen (33). For the remaining variants, residue numbers correspond to those obtained by sequential numbering of mature prothrombin (34). Quality control by N-terminal sequencing and analysis of 4-carboxyglutamate following base hydrolysis confirmed that the purified recombinant variants of prothrombin possessed a correctly processed N terminus with 4-carboxyglutamic acid content that was indistinguishable from the prothrombin purified from plasma (35). Prothrombin variants were exchanged into Assay Buffer by centrifugal gel filtration before use. Protein concentrations were determined using the following molecular weights and extinction coefficients (E2800.1% in mg−1·cm2), respectively: Xa, 45,300 and 1.16 (36); all prothrombin variants, 72,000 and 1.47 (37); thrombin, 37,500 and 1.89 (26); Va, 175,000 and 1.78 (28); sTM, 75,000 and 0.64 (calculated) (30); recombinant tick anticoagulant peptide, 6,980 and 2.56 (31).

Meizothrombin Production

Meizothrombin was produced in situ by treating the prothrombin variant with ecarin and maintaining the cleaved product on ice for use within 4 h for each experiment. This approach was taken to preclude perturbations that might result from attempts to repurify the cleaved product by ion exchange (27). IIA195 or IIQQQ (5 μm in Assay Buffer) was treated with ecarin for 10 min at 25 °C and rapidly cooled on ice. The final concentration of ecarin varied between 0.003 and 0.05 A280/ml depending on the results of test reactions performed for each preparation and reaction condition. For studies in which the Na+ concentration was varied, mIIa was produced in 20 mm Bistris propane, 150 mm choline chloride, 0.1% (w/v) polyethylene glycol (Mr = 8,000), 5 mm CaCl2, pH 7.5. Quantitative cleavage at Arg320 by ecarin and the stability of the resulting mIIa variant in each experiment was assessed by SDS-PAGE analysis of samples taken before the addition of ecarin, immediately after cleavage, and at the end of the 4-h experiment window.

Rapid Kinetics of Fluorescent Probe Binding

Continuous measurement of the binding of DAPA or I-2581 to proteinase was performed using an SX20 stopped-flow instrument with a 20-μl cell (Applied Photophysics, UK). Fluorescence was measured using λex = 280 nm and measuring broadband fluorescence (λem > 500 nm) with a long pass filter (LWP-500, Miles Girot) in the emission beam. Reactions were followed at 25 °C following rapid mixing of proteinase (0.6 μm IIa or mIIa variant) with 12–16 different concentrations of probe in excess of proteinase. Traces were typically acquired using two time scales (2,000 points in 0.05–0.2 s followed by 1,000 points in 4–8 s) to permit description of the fast and slow phases of the reaction. For measurements of probe dissociation, 0.6 μm proteinase premixed with 4 μm probe was rapidly incubated with an equal volume of 200–800 μm FPRck in Assay Buffer. The dissociation rate constant was independent of FPRck at final concentrations ranging from 250 to 400 μm, signifying the kinetic isolation of the limiting dissociation rate constant. For stopped-flow studies in which [Na+] was varied, initial stock solutions were prepared in 20 mm Bistris propane, 0.15 m choline chloride, 0.1% (w/v) polyethylene glycol (Mr = 8,000), 5 mm CaCl2, pH 7.5, and reactant solutions were prepared by mixing with appropriate volumes of the same buffer containing 0.15 m NaCl in place of choline chloride to achieve the indicated concentration of Na+ at constant ionic strength. For reactions with sTM, mIIa variants (0.6 μm) were premixed with increasing concentrations of sTM (0–1 μm; 10 different concentrations) before rapid mixing with the probe.

Stopped-flow Measurements of Prothrombin Cleavage

Fluorescence traces were obtained using the same settings as used in the probe binding studies. Fluorescence was measured following rapid mixing of equal volumes of substrate solution containing 0.6 μm IIQ271 and 2 μm DAPA in Assay Buffer with preassembled enzyme solution containing 0.9 μm Va, 0.6 μm Xa, 300 μm PCPS, and 2 μm DAPA or I-2581 in Assay Buffer. Data were collected using two time scales as described above.

Rapid Chemical Quench

Discontinuous prothrombin conversion experiments were performed in an RQF-3 quench flow instrument (KinTek Corp., Austin, TX). Mixing lines and sample loops were independently calibrated using solutions containing p-nitrophenol (Sigma) of known absorbance. Gravimetric and absorbance measurements of dummy quenched samples established dilution factors and sample recoveries for the different reaction loops used. Reactant syringe A contained 0.6 μm IIQ271 and 2 μm DAPA or I-2581 in Assay Buffer. Reactant syringe B contained 0.9 μm Va, 0.6 μm Xa, 300 μm PCPS, and 2 μm DAPA or I-2581 in Assay Buffer. The reaction was trigged by rapid mixing of equal volumes of reactants and quenched at the indicated time by mixing with Assay Buffer containing 50 mm EDTA and 1 μm recombinant tick anticoagulant peptide in place of CaCl2. Zero time points were obtained by omitting Va and Xa from reactant syringe B. The quenched effluent was collected into capped and preweighed tubes (Minisorp, Nunc, Denmark) containing 2 μl of a 20 mm FPRck solution in 10 mm HCl and frozen for future analysis by SDS-PAGE. FPRck was omitted from the tubes for measurements of product formation inferred from S2238 hydrolysis or from DAPA fluorescence. In each case, subsamples were adjusted for the calibrated reaction loop dilutions and recoveries. Steady state fluorescence of enzyme-bound probe in the quenched samples was determined in a black 96-well plate (Corning, catalogue number 3650) and a Gemini fluorescence plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) using λex = 280 nm and measuring broadband fluorescence with a 500-nm long pass filter in the emission beam. The difference in fluorescence intensity before and after the addition of 10 μm FPRck was assumed to signify the signal associated with proteinase product in the quenched sample. Alternatively, the samples were further diluted, and initial rates of S2238 hydrolysis were measured following the addition of 100 μm S2238 as described (38). Initial rates were converted to concentration of product based on the linear dependence of the initial rate on known concentrations of thrombin done with each experiment. Based on prior experience with bovine prothrombinase (21) and measurements of the instrument dead time, the discrepancy between the intended and observed quench time was assumed to be 4 ms or less. To accommodate this delay, the intended quench times were incremented by 4 ms for analysis.

SDS-PAGE and Quantitative Western Blotting

SDS-PAGE analysis of prothrombin cleavage under steady state conditions was performed using a reaction mixture containing 5 μm IIWT, 8 μm DAPA, 30 nm Va, 50 μm PCPS, and 3 nm Xa in Assay Buffer at 25 °C. Samples withdrawn at various times were quenched, subjected to SDS-PAGE, stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, and analyzed using procedures detailed previously (18). Samples from rapid chemical quench studies were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting and quantitative imaging of near infrared fluorescence. SDS-PAGE was conducted using 10% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen) using samples adjusted to a load of 0.1 μg/lane based on the initial substrate concentration. Separated proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose (0.2-mm pore, Bio-Rad) and blocked in 20 mm Hepes, 0.15 m NaCl, 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, pH 7.4 (HBS-Tween) containing 5% (v/v) Bailey's Irish Cream (39). The blots were incubated for 1 h with 3.5 μg/ml sheep anti-prothrombin polyclonal antibody (Hematologic Technologies, Essex Junction, VT) prepared in HBS-Tween containing 1% (v/v) Bailey's Irish Cream. Following washes with HBS-Tween, blots were probed with a 15,000-fold dilution of IR800-conjugated anti-sheep antibody (Rockland Immunochemicals Inc., Gilbertsville, PA) in HBS-Tween containing 1% (v/v) Bailey's Irish Cream. After thorough washing with HBS-Tween followed by air drying, fluorescence was detected by scanning with a LI-COR Odyssey infrared scanner (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) at 800 nm with the resolution set at 84 mm and intensity set at 4. Quantitative analysis was performed on inverted and unscaled images at 16-bit resolution using the considerations described previously (18).

Data Analysis

In stopped-flow studies, 10–20 replicates were taken for each concentration set and averaged following elimination of the first 2 ms of data. For studies with thrombin, the traces were initially empirically fitted to a single exponential function to extract the limits of the data and permit normalization of the traces to the initial signal, thereby correcting for free probe fluorescence prior to global analysis. For studies with mIIa, a similar approach was taken for normalization by fitting to a three-exponential function prior to global analysis. In cases where global analysis was impractical, fits to the three-exponential function were used to extract the dependence of the normalized fractional amplitude (A/Atot) of the fast and slow phases on the concentration of varied ligand. For this approach, component amplitudes corresponding to rate constants >5 s−1 were summed to represent the fast phase. Stopped-flow kinetic traces of probe binding to proteinase corrected for free probe fluorescence were globally analyzed according to Scheme 1 or 2 using KinTek Global Kinetic Explorer (KinTek Corp.) (40). For analysis according to Scheme 2, e·P (where P represents an active site probe) and E·P were assumed to exhibit identical fluorescence. Microscopic reversibility and detailed balance were accounted for by assuming that the distribution between e·P and E·P satisfied the relationship ([e]/[E]) × KE,P = Ke,P × KConf. This assumption is valid if e·P and E·P yield identical signals. Analysis of prothrombin or IIQ271 cleavage was performed using the system of equations listed in the supplemental material.

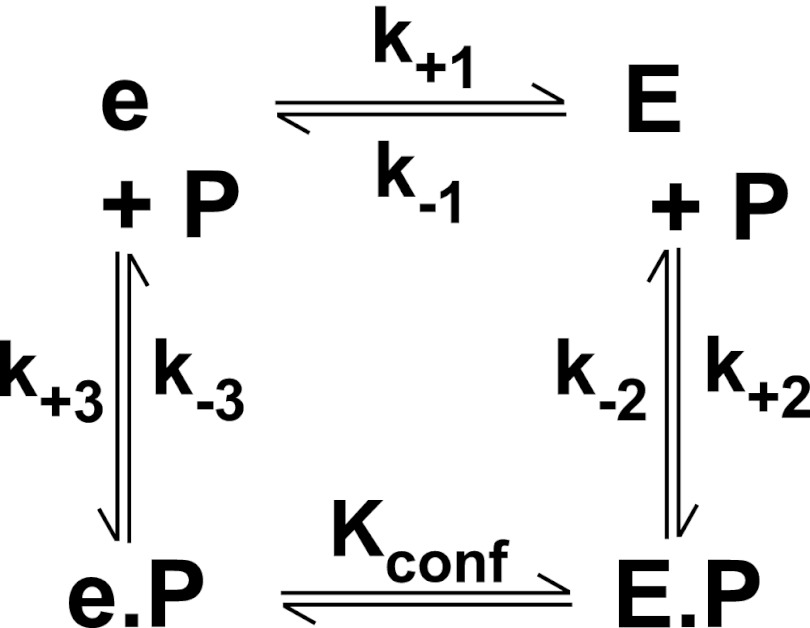

SCHEME 1.

Reaction of thrombin with an active site probe (P). Thrombin is proposed to exist in a pre-equilibrium between e and E of which E binds P with high affinity to form E·P, resulting in an increase in fluorescence intensity.

SCHEME 2.

Reaction of mIIa with an active site probe (P). mIIa is proposed to exist in an equilibrium between e and E. E binds P with high affinity to form E·P, whereas e binds P with much weaker affinity. The fluorescence increase associated with the formation of e·P or E·P is assumed to be identical. The interconversion between e·P and E·P is described by KConf = e·P/E·P.

RESULTS

Experimental Design

Ecarin selectively cleaves prothrombin at Arg320 to yield mIIa. However, the product is rapidly and near quantitatively autolyzed, leading to the removal of the propiece and the formation of a proteinase species resembling thrombin (41). Consequently, most studies have relied on mIIa stabilized by covalent modification of the active site or by the use of tight binding inhibitors to preclude autolysis (41). However, ligation of the active site by reversible or irreversible inhibitors is established to drive zymogen-like forms of thrombin to proteinase-like states (13, 16). Consequently, we pursued studies with mIIa variants that do not require active site ligation for stability. In the first case, catalytically active but stable mIIaQQQ was produced from IIQQQ in which Arg155, Arg284, and Arg271 were replaced with Gln to abrogate cleavage at these sites (32). For secure interpretations, we have also confirmed key findings with mIIaA195 produced from IIA195 in which the catalytic serine was replaced with alanine (13). mIIaA195 is catalytically inactive but stable despite the presence of Arg residues at the autolytic sites and is expected to retain the ability to bind active site ligands. In a further strategy to ensure valid conclusions, we have studied the reaction of thrombin and both mIIa variants with DAPA and I-2581, which represent related but chemically dissimilar active site-binding probes (42). Although data obtained in the reaction of mIIaQQQ with I-2581 are presented, equivalent conclusions but with minor differences in detail could be derived with both mIIa variants and both active site probes.

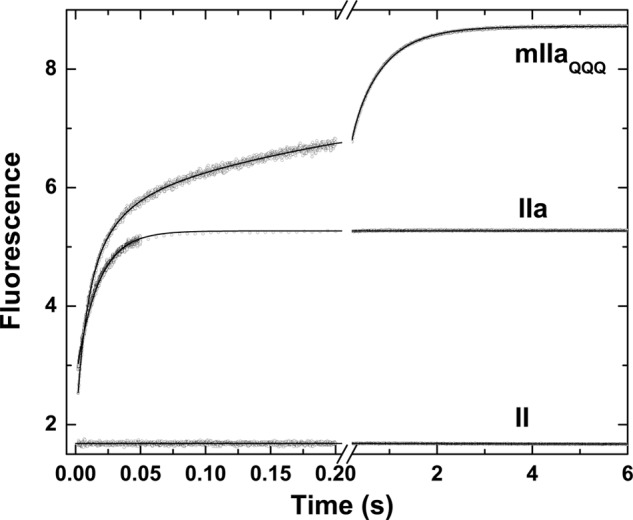

Binding of Active Site Probes to Prothrombin and Derivatives

The kinetics of binding of I-2581 was assessed by rapid kinetic measurements of probe fluorescence. Fluorescence was measured by excitation of the protein at 280 nm to allow energy transfer to the dansyl moiety in either probe, thereby further enhancing confidence in the relationship between probe binding and changes in fluorescence intensity (43). Rapid mixing of thrombin with a saturating concentration of I-2581 produced a rapid increase in fluorescence that plateaued within 100 ms, whereas mixing of prothrombin with the probe produced no change in signal (Fig. 1). This finding is consistent with the need for a mature active site, which is absent in the zymogen, for I-2581 binding (44). In contrast, rapid mixing of I-2581 with mIIaQQQ produced a markedly biphasic change in fluorescence. Approximately 50% of the fluorescence change occurred on the time scale of the fluorescence change seen with thrombin, whereas the remaining half occurred over several seconds (Fig. 1). The larger increase in fluorescence with mIIa is in line with a larger quantum yield for probe fluorescence bound to the active site of mIIa relative to thrombin (43, 44). Although the trace obtained with thrombin could be approximated with a single exponential function with t½ ∼14 ms, empirical description of the trace obtained with mIIaQQQ required analysis according to a two- or three-exponential function with time constants differing by ∼30-fold (Fig. 1). Prior reaction of either thrombin or mIIaQQQ with FPRck abrogated the fluorescence increase, further confirming active site binding as the source of the fluorescence increase. Furthermore, similar results were obtained using DAPA or mIIaA195 (not shown). The findings suggest that the binding of probes to the active site of mIIa is more complex than their binding to the active site of thrombin.

FIGURE 1.

Kinetics of I-2581 binding to prothrombin and its derivatives. Fluorescence traces were obtained using λex = 280 nm and λem >500 nm following rapid mixing of equal volumes of a 0.6 μm concentration of the indicated derivative and 4 μm I-2581 at 25 °C in Assay Buffer. The average of four to six traces acquired over a split time scale is illustrated in each case, and the fitted lines are drawn according to the following analyses: prothrombin (II), straight line with near-zero slope; thrombin (IIa), single exponential function with offset = 2.79 ± 0.002, A = 2.55 ± 0.004, and k = 59.3 ± 0.2 −−1; mIIaQQQ, three-exponential function with offset = 2.09 ± 0.002, A1 = 2.88 ± 0.02, k1 = 94.5 ± 1.3 s−1, A2 = 1.22 ± 0.02, k2 = 18.2 ± 0.5 s−1, A3 = 2.74 ± 0.01, k3 = 1.59 ± 0.01 s−1.

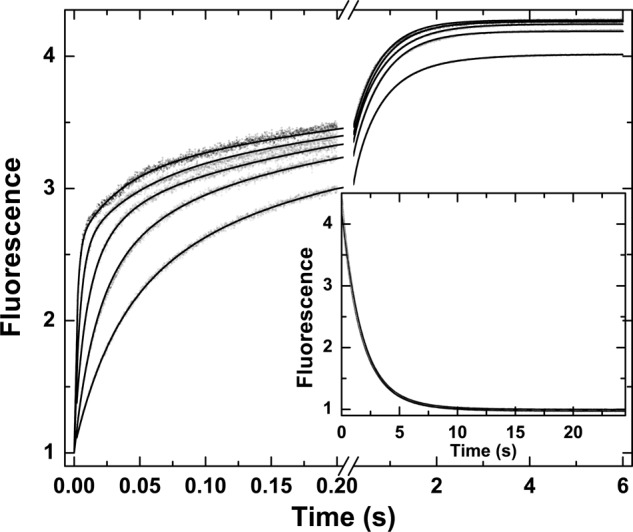

Kinetics of Probe Binding to Thrombin

Despite the apparent lack of complexity in stopped-flow traces of I-2581 binding to thrombin (Fig. 1), global analysis of traces obtained over a wide range of concentrations revealed the likely presence of at least one step in addition to the bimolecular reaction between probe and proteinase. In combination with the global analysis of traces obtained at different concentrations of probe, an additional fitting constraint was sought from the measured kinetics of probe dissociation derived from rapid mixing of thrombin pre-equilibrated with I-2581 with a vast excess of FPRck (Fig. 2). Based on prior findings with thrombin (13), the most parsimonious and satisfactorily constrained global analysis could be performed by assuming an initial equilibrium between two forms of the proteinase (e and E), only one of which binds the probe with detectable affinity relevant to the present reaction conditions (Scheme 1). This is obviously a limiting case of the more general model wherein e also binds probe but with lower affinity (see below). However, this aspect is not resolvable under the current experimental conditions. Global analysis according to this scheme yielded an adequate description of the data (Fig. 2). Provided Scheme 1 applies, the fitted constants reveal that the partitioning of thrombin between e and E is derived from rapid interconversions between the two forms that are in a ∼20:∼80 distribution (Table 1). Equivalent conclusions can be drawn from a global analysis of measurements with increasing concentrations of DAPA (Table 1). Evidence supporting the applicability of Scheme 1 is derived from the following: equivalence of the kinetic constants for the probe-independent steps inferred from studies with DAPA or I-2581 (Table 1), agreement between the inferred binding constants for the two probes and their respective measured equilibrium dissociation constants (30, 42, 45), and prior studies suggesting that ∼15% of thrombin is zymogen-like and can be further stabilized in the proteinase-like state with active site ligation (13). Thus, the presence of a relatively minor distribution of thrombin between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms, predicted from thermodynamic measurements, can evidently be corroborated by the global analysis of stopped-flow kinetic studies.

FIGURE 2.

Kinetics of I-2581 binding to thrombin. Selected fluorescence traces are illustrated following rapid mixing of thrombin with increasing concentrations of I-2581 to yield final concentrations of 0.3 μm thrombin and 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 μm (bottom to top) I-2581. Inset, dissociation trace obtained following reaction of 0.6 μm thrombin preincubated with 4 μm I-2581 with 800 μm FPRck. The lines are drawn following global analysis of these and other data according to Scheme 1 to yield the fitted constants listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Constants for the binding of active site-directed fluorescent probes to thrombin and meizothrombin variants

Constants ± 95% confidence limits were determined from global fitting according to Scheme 1 (for thrombin (IIa)) or Scheme 2 (for mIIa). The symbolic constants correspond to those listed in the two schemes.

| Species | Probe | k+1 | k−1 | fea | fE | k+2 | k−2 | KE,Pb | k+3 | k−3 | Ke,P | KConf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s−1 | s−1 | μm−1·s−1 | s−1 | nm | μm−1·s−1 | s−1 | nm | |||||

| IIa | I-2581 | 98.9 ± 2.8 | 20.5 ± 1.6 | 0.18 | 0.82 | 49.4 ± 0.6 | 1.02 ± 0.001 | 20.6 ± 0.02 | NAc | NA | NA | NA |

| IIaA195 | I-2581 | 81.4 ± 2.1 | 16.8 ± 0.9 | 0.17 | 0.83 | 34.2 ± 0.3 | 5.84 ± 0.04 | 171 ± 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| IIa | DAPA | 113 ± 2 | 27.1 ± 0.6 | 0.19 | 0.81 | 71.1 ± 0.6 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 3.2 ± 0.11 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| mIIaA195 | I-2581 | 1.67 ± 0.01 | 2.33 ± 0.06 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 32.7 ± 0.3 | 5.95 ± 0.01 | 182 ± 1.3 | 0.95 ± 0.11 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 940 ± 10 | 0.27 ± 0.09 |

| mIIaQQQ | I-2581 | 1.67 ± 0.01 | 1.93 ± 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 57.3 ± 0.2 | 0.54 ± 0.01 | 9.3 ± 0.01 | 1.76 ± 0.01 | 2.30 ± 0.23 | 1310 ± 110 | 0.008 ± 0.001 |

| mIIaQQQ | DAPA | 1.70 ± 0.17 | 1.89 ± 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 92.5 ± 0.6 | 0.26 ± 0.006 | 2.84 ± 0.05 | 2.33 ± 0.07 | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 250 ± 20 | 0.013 ± 0.003 |

a Fraction of enzyme in the e and E forms in the initial equilibrium is denoted by fe and fE.

b KE,P = k−2/k+2 is the equilibrium dissociation constant for P binding to E. Ke,P = k−3/k+3 is the equilibrium dissociation constant for P binding to e. Propagation of errors in the rate constants was used to estimate confidence limits in the calculated equilibrium constants (59).

c NA, not applicable.

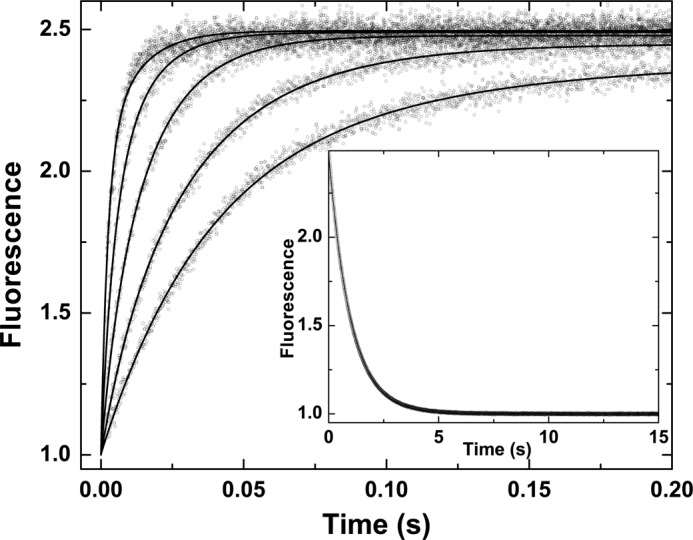

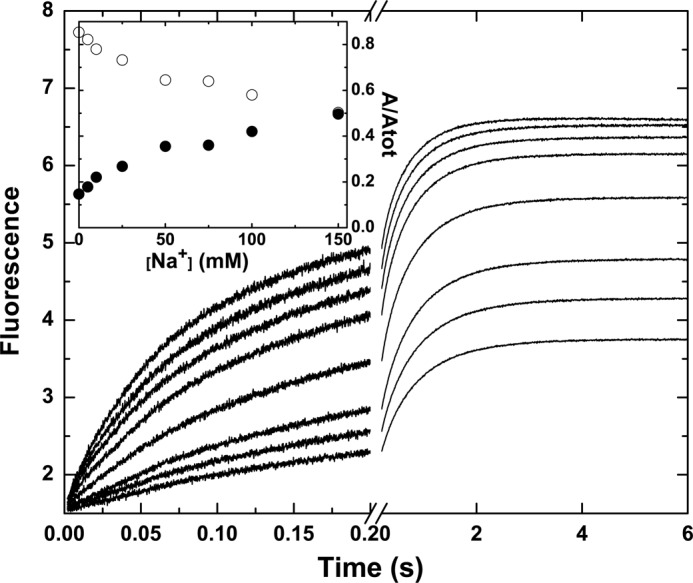

Kinetics of Probe Binding to mIIa

Global analysis of probe binding to mIIaQQQ was also pursued using traces obtained at different concentrations of I-2581 and by measuring probe dissociation by trapping studies with FPRck (Fig. 3). Increasing concentrations of probe yielded proportional increases in the rate constant for the fast phase with only minor effects on the rate constant for the slow phase (Fig. 3). These findings implicate the fast phase in the bimolecular interaction between probe and proteinase, whereas the slow phase likely reflects a unimolecular step in the reaction. Because of the informative nature of the complex curve shapes, global analysis was feasible using a more general reaction scheme than the one used for thrombin (Scheme 2). Both e and E can bind probe with different affinities with the underlying assumption that e·P and E·P yield identical fluorescence changes. This important and simplifying assumption is based on the equivalent fluorescence changes observed for the binding of DAPA to a zymogen-like variant of thrombin and the wild type proteinase despite vastly different affinities (46). Global analysis according to Scheme 2 provided a satisfactory description of the data (Fig. 3). The fitted constants reveal that the two enzyme forms in the initial equilibrium are approximately equally populated and interconvert slowly (t½ ∼ 0.6 s) (Table 1). Rate constants for this probe-independent step were equivalent whether inferred from studies with I-2581 or DAPA or even using mIIaA195 (Table 1). Furthermore, in all combinations, e bound P with an affinity that was significantly weaker than that inferred for P binding to E. Although KE,P for the binding of DAPA or I-2581 to mIIaQQQ was consistent with values measured for thrombin, mIIaA195 bound the probe more weakly in line with the lower affinity measured for DAPA binding to the comparable mutation in thrombin (45). Thus, comparable conclusions regarding the slow interconversion between the two enzyme forms and the higher affinity of E for P can be drawn independently of the probe and mutations used to stabilize mIIa. We suggest that e represents a zymogen-like form and that E represents a proteinase-like form of mIIa wherein the relative amplitude of the fast phase roughly bears on the proportion of E and that of the slow phase roughly bears on the proportion of e in the initial equilibrium. This contention is supported by the ability of the fractional amplitudes of the fast and slow phases derived from empirical analyses (below) to approximate the relative fractions of e and E inferred from global analyses (Table 1).

FIGURE 3.

Kinetics of I-2581 binding to mIIaQQQ. Selected fluorescence traces are illustrated following rapid mixing of mIIaQQQ with increasing concentrations of I-2581 to yield final concentrations of 0.3 μm proteinase and 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 μm (bottom to top) I-2581. Inset, dissociation trace obtained following reaction of 0.6 μm mIIaQQQ preincubated with 4 μm I-2581 with 800 μm FPRck. The lines are drawn following global analysis of these and other data according to Scheme 2 to yield the fitted constants listed in Table 1.

Modulation of the Distribution of mIIa between e and E Forms

We surmise that the species e and E reflect zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms on the basis of our initial expectations for a thrombin variant containing F12 covalently linked to ABE2 and by the much weaker affinity of e for active site probes in comparison with E (i.e. Ke,P > KE,P) (Table 1). This idea is experimentally testable using the established ability of Na+ and the proposed ability of sTM binding to ABE1 to alter the equilibrium distribution between zymogen-like and proteinase-like states in thrombin variants (13).

Stopped-flow studies assessed the binding of I-2581 to mIIaQQQ at varying concentrations of Na+ (0–0.15 m) but at constant ionic strength by compensation with choline chloride (13). As the Na+ concentration was decreased from 0.15 to 0 m, the relative amplitude of the slow phase was markedly increased (Fig. 4). A meaningful global analysis of the data was precluded by the unknown complexity of the equilibria associated with Na+ binding to e and E forms and the effects of cation binding on the affinity of the two forms for P. Instead, we sought a mechanism-independent assessment by extracting the relative amplitudes of the fast and slow phases following fitting of the traces to a three-exponential rise. The roughly equal contribution of the two phases seen at 0.15 m Na+ changed systematically with decreasing concentrations of the cation (Fig. 4, inset). At 0 m Na+, the slow phase accounted for ∼85% of the total amplitude. Given the rough correspondence between the fractional amplitude of the slow phase and the fraction of the e form in the initial equilibrium, the findings indicate that the equilibrium distribution between e and E is substantially shifted in favor of e at 0 m Na+. When taken together with the zymogen-like character of thrombin in the absence of Na+ established in previous work (13), these data provide one line of evidence supporting the proposal that the e and E forms reflect zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms of mIIa, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

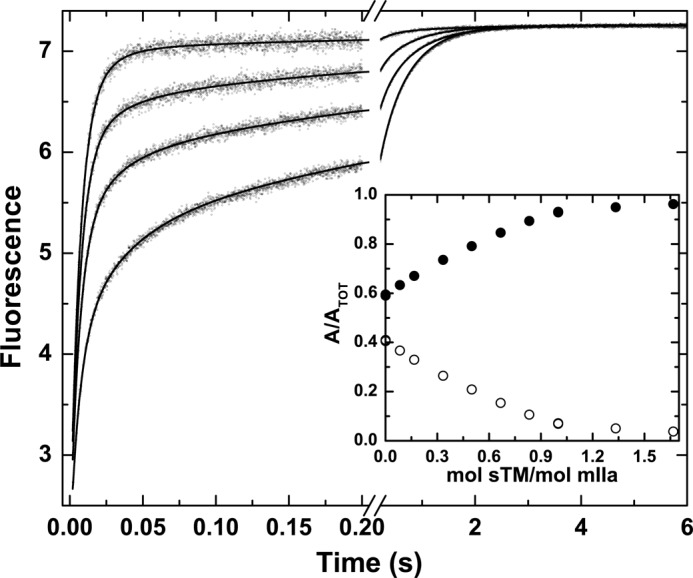

Na+-dependent modulation of probe binding to mIIaQQQ. Stopped-flow fluorescence traces of the binding of I-2581 to mIIaQQQ at final concentrations of 0.5 and 0.3 μm, respectively, are illustrated at final Na+ concentrations ranging from 0 to 150 mm (bottom to top). Inset, fractional amplitudes of the slow phase (○) and the fast phase (●) as a function of Na+.

In an alternate strategy, stopped-flow measurements were conducted following rapid mixing of I-2581 with mIIaQQQ preincubated with increasing concentrations of sTM (Fig. 5). The fractional amplitude of the fast phase increased saturably with increasing concentrations of sTM, reaching a limiting value nearing 1 with very little of the slow phase evident (Fig. 5, inset). The dependence of the fractional amplitudes of the two phases became saturated at approximately a molar equivalent of sTM in relation to the concentration of mIIaQQQ (Fig. 5, inset). These findings are consistent with the 10−8 m affinity expected for the interaction of sTM with mIIa (20). The predominance of the fast phase at saturating concentrations of sTM indicates that it binds differentially to e and E forms to shift the initial equilibrium far to the right in favor of E. The prior proposal that sTM binding to ABE1 is likely to favor proteinase-like thrombin over zymogen-like forms is based on the enhanced affinity of ABE1 ligands for the proteinase relative to the zymogen (47). Consequently, the findings with sTM provide a second line of evidence to support the idea that the e and E forms represent zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms of mIIa, respectively.

FIGURE 5.

sTM-dependent modulation of probe binding to mIIaQQQ. Stopped-flow fluorescence traces of the binding of I-2581 to mIIaQQQ at final concentrations of 0.5 and 0.3 μm, respectively, are illustrated at final sTM concentrations of 0, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 μm (bottom to top). Inset, fractional amplitudes of the slow phase (○) and the fast phase (●) as a function of sTM.

Zymogen-like and Proteinase-like mIIa during Prothrombin Cleavage

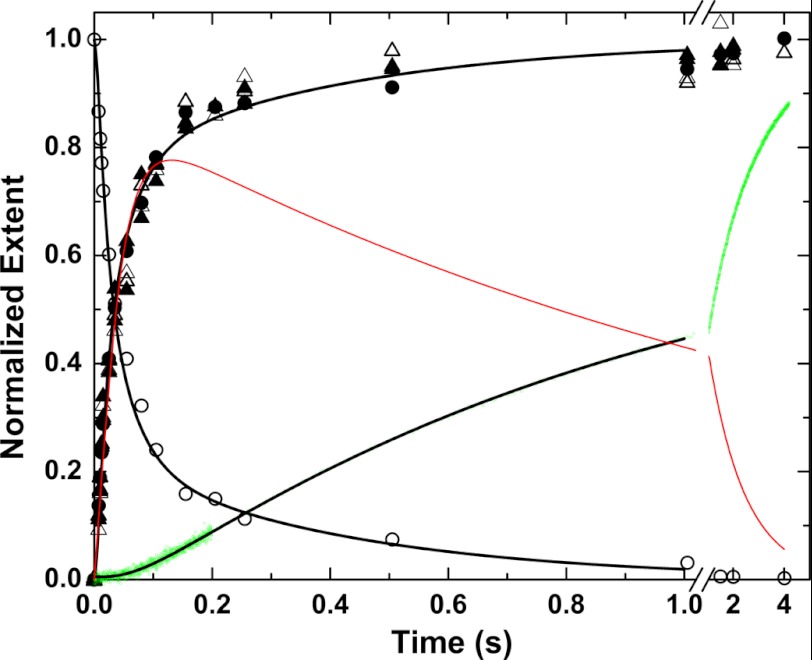

It follows that slow equilibration between zymogen-like (e) and proteinase-like (E) forms should be evident following the initial cleavage of prothrombin at Arg320 by prothrombinase. This possibility was tested by examining the action of prothrombinase on IIQ271 that can only be cleaved at Arg320 to yield mIIa (18). Rapid kinetic studies were pursued using [E] ∼ [S] to approximate single turnover leading to rapid cleavage of the substrate. This approach would permit detection of slow steps that might follow the cleavage reaction. Accordingly, substrate depletion and product formation detected by rapid chemical quench and SDS-PAGE were rapid and essentially complete within 200 ms (Fig. 6). Equivalent results were obtained when the concentration of proteinase product in the quenched samples was assessed by peptidyl substrate cleavage or by monitoring the enhanced fluorescence of DAPA bound to the active site of the proteinase product (Fig. 6). However, continuous monitoring of proteinase formation in the presence of DAPA yielded a strikingly shifted progress curve (Fig. 6). The fluorescence increase was preceded by a prominent lag (Fig. 6). Only minor amounts of product detected in the first 200 ms continued to increase well after the near quantitative exhaustion of substrate in the quenched samples. This discrepancy points to a delay on the time scale of seconds before cleaved product can bind DAPA with high affinity. Trivial explanations that the probe binds slowly to proteinase product or that the action of prothrombinase on prothrombin was inefficiently quenched are ruled out by the measured rate constants for probe binding (Table 1), the extensive control experiments done in rapid chemical quench studies with bovine prothrombinase (21), and the initial slopes of the progress curves (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Cleavage of IIQ271 by prothrombinase under conditions approximating single turnover. Kinetic measurements were performed following rapid mixing of equal volumes of 0.6 μm prothrombinase (0.6 μm Xa, 0.75 μm Va, and 300 μm PCPS) and 0.6 μm IIQ271 in the presence of 2 μm DAPA. Substrate depletion (○) and product formation (●) were measured discontinuously following rapid chemical quench and SDS-PAGE. Alternatively, proteinase product was inferred in the quenched samples by initial velocity measurements of S2238 hydrolysis (△) or by the enhanced steady state fluorescence of DAPA (▴). Product formation was also measured continuously by stopped flow (green dots) by monitoring the enhanced fluorescence of DAPA bound to the proteinase product. The black lines are drawn by simulation/fitting according to supplemental Scheme IS using the considerations, assumptions, and constants listed. The red line depicts the difference between the fitted product time course from rapid chemical quench and the fitted line for the continuous stopped-flow measurement.

One explanation lies in the extension of the slow equilibration between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms (Scheme 2) to the pathway of product formation following cleavage at Arg320 by prothrombinase. Both e and E are indistinguishable by SDS-PAGE. In addition, peptidyl cleavage or probe binding measured using saturating ligand concentrations in quenched samples would also quantitatively shift the equilibrium to favor E (t½ < 1 s), well within the time scale of the assay. Thus, discontinuous measurements by chemical quench would yield the sum of both products. In contrast, the stopped-flow fluorescence measurements would be biased toward detecting E because of its higher affinity for the probe. The difference between the two types of measurements illustrates the prominent contribution of the slow interconversion between zymogen-like and proteinase-forms of mIIa to total product detected by rapid chemical quench (Fig. 6).

Kinetic simulations and fitting approaches used generalized supplemental Scheme IS to assess whether these ideas were consistent with published steady state kinetic measurements (18) and the constants determined for probe binding to mIIaQQQ (Table 1). The bulk of the rate constants needed for robust accounting for rapid kinetic data using supplemental Scheme IS are unknown as are numerous mechanistic details. However, supplemental Scheme IS provided an adequate description of the data (Fig. 6) using the rate constants in Table 1 and the various assumptions described (supplemental material). We offer this only to propose qualitative agreement between our interpretations and the rapid kinetic studies pending proper investigation. Our interpretations also provide a potential explanation for analogous findings of unknown significance made previously in rapid kinetic studies of prothrombin activation in the bovine system (21).

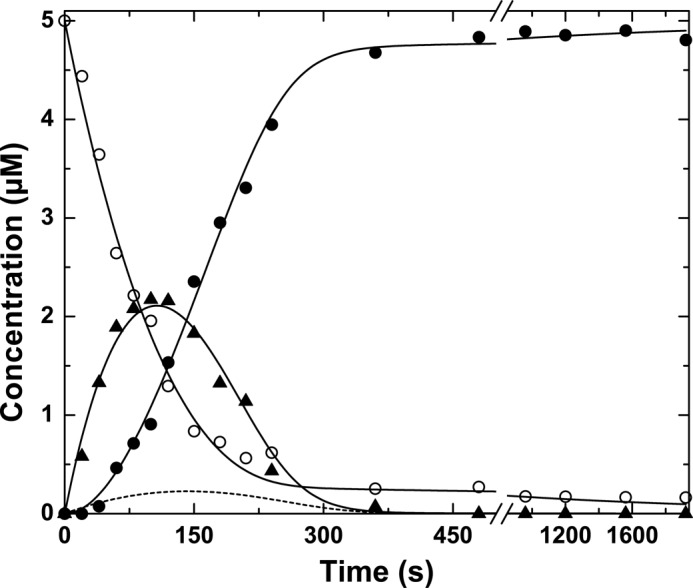

The Rate-limiting Step in Prothrombin Activation

Additional evidence for the slow equilibration of meizothrombin between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms was sought from the action of prothrombinase on prothrombin under steady state conditions. As established in prior work (18), the essentially ordered action of prothrombinase on Arg320 in prothrombin followed by cleavage of the mIIa intermediate at Arg271 yields a profile in which the consumption of prothrombin and the delayed appearance of thrombin is separated by the transient accumulation of mIIa (Fig. 7). Steady state kinetic constants for the individual half-reactions have been determined using IIQ271 and mIIa covalently inhibited with FPRck (18). However, simulation of the two sequential enzyme-catalyzed reactions (supplemental Scheme IIS) using the individually determined steady state parameters failed to provide a satisfactory accounting for the amplitude of mIIa accumulating as an intermediate (Fig. 7). Thus, additional steps separating the two half-reactions are likely necessary to account for the action of prothrombinase on prothrombin.

FIGURE 7.

Prothrombin cleavage by prothrombinase under steady state conditions. The reaction mixture contained 5 μm prothrombin, 30 nm Va, 30 μm PCPS, and 3 nm Xa (3 nm prothrombinase), and 8 μm DAPA in Assay Buffer at 25 °C. Samples withdrawn at the indicated times were quenched and subjected to SDS-PAGE, and protein bands were visualized by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The fates of prothrombin (○), mIIa (▴), and thrombin (●) were determined by quantitative analysis following scanning densitometry. The dashed line illustrates the fate of mIIa predicted by supplemental Scheme IIS using published steady state kinetic constants for the individual half-reactions. The solid lines were derived from fitting/simulation using supplemental Scheme IIIS using the parameters listed in the supplemental material.

Prior work has established the essential role of the zymogen to proteinase transition following the initial cleavage of prothrombin at Arg320 in facilitating subsequent cleavage at Arg271 (46). It follows that slow equilibration between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms of mIIa must separate the formation of mIIa as a product from its productive interaction with prothrombinase as a substrate (supplemental Scheme IIIS). Accordingly, supplemental Scheme IIIS could provide a reasonable accounting for the progress curves of substrate depletion, transient accumulation of total mIIa, and delayed appearance of thrombin (Fig. 7). Thus, the slow and reversible interconversion between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms of mIIa plays an essential role in regulating the kinetics of prothrombin activation and the sequential action of prothrombinase on prothrombin.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides unexpected insights into coagulation proteinase function resulting from the convergence of ideas developed in two independent lines of investigation. Drawing from the findings in thermodynamic studies of the reversible interaction of F12 with thrombin (13), we now show that mIIa is zymogen-like because of covalent linkage between the F12 region and the proteinase domain. Despite cleavage following the equivalent of Arg15 in chymotrypsinogen (19, 33), mIIa is in a slow and reversible equilibrium between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms that are approximately equally populated. In the second, we draw from ideas developed in mechanistic studies of the stepwise action of prothrombinase on prothrombin (18, 46) to show that the reversible equilibrium between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms of mIIa likely plays an unexpected but dominant role in determining the kinetics of prothrombin activation.

The peculiar specificity profile of mIIa has implicitly been attributed to its ability to bind membranes through the F12 domain (19, 20). Membrane binding by the proteinase undoubtedly plays a role in affecting its ability to act on membrane-bound substrates in a way that makes it distinct from thrombin. However, an additional explanation for the specificity profile of mIIa lies in the reversible equilibrium between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms. We propose that the appearance of an altered specificity profile for mIIa arises from the differential ability of the diverse thrombin substrates and ligands to bind the active site and/or ABE1 and favor the proteinase-like state. Substrates, such as fibrinogen, found in plasma at concentrations at or below Km (48) would not significantly perturb the equilibrium, yielding lower rates of cleavage by mIIa. In contrast, TM, which binds with high affinity to mIIa (20), would favor the proteinase-like state and fully rescue its ability to activate protein C. This provides an explanation for why mIIa exhibits reduced procoagulant but normal anticoagulant function (20, 49). Because the zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms are approximately equally populated, the appearance of altered specificity arising from such effects is expected to be in the order of 2–3-fold. These ideas are generally consistent with measurements comparing the action of thrombin and mIIa on its various substrates (20). In the case of much larger observed differences, we suggest that those arise from the added contributions of membrane binding and/or the occlusion of ABE2 by the covalently attached F12 domain.

The ability of mIIa to hydrolyze S2238 at the same rate as thrombin is seemingly inconsistent with its proposed zymogen-like character (19). However, this is fully consistent with the ability of saturating concentrations of peptidyl substrate to favor the proteinase-like state much as has been documented with active site-directed ligands in the present study. The re-equilibration would occur on a time scale (10 × t½ ∼ 7 s) that would be undetectable by initial velocity measurements under steady state conditions.

The basis for the exceptionally zymogen-like character of mIIa lies in the large thermodynamic differences in the interaction of F12 with the zymogen relative to proteinase (13). Although it is the fragment 2 region of F12 that contacts ABE2 in the proteinase domain, fragment 2 does not show an ability to discriminate between zymogen and proteinase as does F12 (32). This suggests that the distal fragment 1 region plays a key role in enforcing the zymogen-like character of mIIa irrespective of its ability to confer Ca2+-dependent membrane binding to the proteinase. This likely represents part of the explanation for why proteolytic removal of the fragment 1 region to produce mIIaΔF1 yields a proteinase with a specificity profile and other features closer to that of thrombin (20). It also provides a potential explanation for why the x-ray structure of the proteinase domain of mIIaΔF1 closely resembles that of thrombin, although in this case, it is difficult to exclude the effects of covalent modification of the active site with FPRck (50, 51).

The terminology we use is analogous to that used in the voluminous literature on the Na+-dependent (albeit rapid) transitions of thrombin or mIIaΔF1 between E* and E forms wherein only E binds Na+ (15). We balk at equating our findings with those based on varying or 0 m Na+ as it is now clear that the previously proposed equilibrium between E* and E in thrombin would be well in favor of E bound to Na+ at physiological pH, temperature, and salt (13).

Changing reasons, some of which are considered below, have been proposed over time to argue that ideas related to interconversions between zymogen- and proteinase-like forms proposed in previous work (13, 16, 52) are “inconsistent with more than 20 years of enzymatic studies” (53), “confound E* for a zymogen form” (51), or are “an induced-fit mechanism in disguise at variance with kinetics of ligand binding and structural biology” (15). The categorical argument that E* cannot represent a zymogen-like form because the salt bridge between the chymotrypsinogen-equivalent residues Ile16 and Asp194 is correctly formed is not well founded (54). The zymogen to proteinase transition that accompanies salt bridge formation is associated with the ordering of several loops and the formation of the oxyanion hole (16). Thermodynamic additivity in these changes drives proteinase maturation and underlies the ability of ligands to affect interconversions between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms (13). These ideas, which are supported by NMR studies of variously ligated forms of thrombin and the numerous deformed thrombin structures, justify consideration of the findings in terms of reversible transitions between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms (15, 16). The additional criticism (15) that rapid interconversions between such states are inconsistent with kinetic findings is also misleading because the prior thermodynamic approaches provide no information on rate. Indeed, our present findings clearly show that such transitions can be slow. Because a reversible equilibrium between two enzymic forms can account for rapid kinetic measurements measuring a particular signal, there is no reason to exclude a variety of possible intermediates that may be accessible by alternate measurement strategies. Finally, recent studies with mIIa have established an ∼6-fold weaker affinity for Na+ binding in comparison with thrombin (55). This is also in line with expectations of a system in which a zymogen-like form is prevalent (13).

The observation that slow equilibration between zymogen- and proteinase-like forms of mIIa also follows the initial action of prothrombinase at Arg320 in prothrombin meshes in an unexpected way with evidence implicating the zymogen to proteinase transition in facilitating the second cleavage reaction at Arg271 (46). We propose that this slow interconversion separates the release of product from the first half-reaction and its productive interaction with prothrombinase as a substrate for the second half-reaction, thereby representing a previously undocumented rate-limiting step in thrombin formation (Scheme 3). These proposals are based on findings with isolated mIIa, rapid kinetic studies showing a large delay between cleavage at Arg320 by prothrombinase and the appearance of product that can bind active site ligand, and the fact that the inclusion of this step provides for the first time an adequate description of the fate of mIIa during prothrombin activation. The kinetic schemes that form the bases for these analyses are arguable because of numerous unverified assumptions and simplifications. Nevertheless, their basis lies in the unanticipated physical evidence that the process previously referred to as ratcheting between zymogen and proteinase configurations of product/substrate actually occurs in a way to limit the rate of thrombin formation and the extent to which mIIa accumulates as an intermediate (46).

SCHEME 3.

Revised scheme for prothrombin activation by prothrombinase. The individual half-reactions of prothrombin activation are separated by the slow and reversible equilibration of the intermediate, meizothrombin, between zymogen-like (mIIa′) and proteinase-like (mIIa) states. Steady state kinetic constants listed correspond to those determined for the action of prothrombinase on IIQ271 or mIIa covalently inactivated with FPRck (18).

Interpretations related to the near exclusively ordered action of prothrombinase on prothrombin have recently become controversial (56–58). Kinetic modeling studies have led to the proposal that both ratcheting of substrate and two interconverting forms of prothrombinase are responsible for the two cleavage reactions (57). The rate constants proposed for a possible ratcheting step are >20-fold slower than those shown by the present direct measurement and represented as unidirectional (57). Alternatively, others have argued that the equilibrium between E* and E detected in Na+ binding studies with mIIaΔF1 need to be accounted for in explaining the pathway of prothrombin activation (51). In this case, the measured rate constants were ∼50-fold larger than those seen in the present work (51). Thus, both alternative proposals are inconsistent with the findings of the present study. The key feature of the interconversion between zymogen-like and proteinase-like forms of mIIa germane to accounting for prothrombin cleavage lies in the facts that it proceeds slowly (t½ ∼ 0.7 s) and reversibly.

The dominant role proposed for this slow ratcheting step in regulating prothrombin cleavage raises questions as to why it has not been evident in previous steady state kinetic studies and whether steady state kinetic constants determined for the second half-reaction already take this step into account (18, 27). The failure of prior work to detect this step most likely lies in the use of mIIa modified with FPRck or mIIa isolated in the presence of DAPA as a substrate for the second reaction (17, 18, 27). Covalent modification of the active site or DAPA binding would be expected to shift the equilibrium in favor of the proteinase-like form. Thus, the conversion of the proteinase-like form of mIIa to thrombin is appropriately reflected by the steady state kinetic constants determined in this way. A related question is why ligands, such as DAPA, used to monitor reaction progress do not fundamentally alter the kinetics of intermediate accumulation or thrombin formation (46). The explanation for this lies in the fact that the rate constants governing the ratcheting step are slow and rate-limiting (Scheme 3). This equilibrium will be pulled to the right by the selective action of prothrombinase on the proteinase-like form of mIIa with the same time constant regardless of the presence of DAPA.

We also suggest that there may be physiological significance for our findings beyond filling in important mechanistic details on how prothrombin is activated. The amount of mIIa produced as an intermediate is determined in a dominant way by the slow and reversible ratcheting step. Consequently, a sizable fraction of mIIa evident at any time represents the zymogen-like variant, refractory to both further cleavage and inhibition by proteinase inhibitors. This species may be washed downstream from its site of formation in flowing blood, bind thrombomodulin, and participate in protein C activation, thereby demarcating the limits of the clot. This provides a plausible scenario for why it may be important to produce a long lived intermediate with selectively anticoagulant function even before thrombin is produced.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to our colleague Rodney Camire for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-74124 and HL-108933.

This article contains supplemental Schemes IS–IIIS.

- TM

- thrombomodulin

- DAPA

- dansylarginine-N-(3-ethyl-1,5-pentanediyl)amide

- FPRck

- d-phenylalanyl-l-proline-l-arginine chloromethyl ketone

- F12

- fragment 1.2

- IIQ271

- prothrombin containing Gln in place of Arg271

- IIQQQ

- prothrombin variant containing Gln in place of Arg155, Arg271, and Arg284

- IIA195

- prothrombin variant containing Ala in place of catalytic Ser195

- IIaA195

- thrombin prepared from IIA195

- I-2581

- Nα-dansyl-(p-guanidino)-phenylalanine-piperidide

- mIIa

- meizothrombin

- mIIaQQQ

- meizothrombin prepared from IIQQQ

- mIIaA195

- meizothrombin prepared from IIA195

- mIIaΔF1

- meizothrombin variant lacking the fragment 1 region

- PCPS

- small unilamellar phospholipid vesicles composed of 75% (w/w) hen egg l-α-phosphatidylcholine and 25% (w/w) porcine brain l-α-phosphatidylserine

- sTM

- extracellular domain of thrombomodulin

- S2238

- H-d-phenylalanyl-l-pipecolyl-l-arginine-p-nitroanilide

- ABE

- anion-binding exosite

- Bistris propane

- 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane

- dansyl

- 5-dimethylaminonaphthalene-1-sulfonyl.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mann K. G., Jenny R. J., Krishnaswamy S. (1988) Cofactor proteins in the assembly and expression of blood clotting enzyme complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 57, 915–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mann K. G., Nesheim M. E., Church W. R., Haley P., Krishnaswamy S. (1990) Surface-dependent reactions of the vitamin K-dependent enzyme complexes. Blood 76, 1–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mann K. G. (2003) Thrombin formation. Chest 124, 4S-10S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Esmon C. T. (2003) The protein C pathway. Chest 124, 26S-32S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Esmon C. T., Esmon N. L. (2011) The link between vascular features and thrombosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 73, 503–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bode W. (2006) The structure of thrombin: a janus-headed proteinase. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 32, Suppl. 1, 16–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lane D. A., Philippou H., Huntington J. A. (2005) Directing thrombin. Blood 106, 2605–2612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arni R. K., Padmanabhan K., Padmanabhan K. P., Wu T. P., Tulinsky A. (1993) Structures of the noncovalent complexes of human and bovine prothrombin fragment 2 with human PPACK-thrombin. Biochemistry 32, 4727–4737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jakubowski H. V., Kline M. D., Owen W. G. (1986) The effect of bovine thrombomodulin on the specificity of bovine thrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 3876–3882 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ye J., Esmon N. L., Esmon C. T., Johnson A. E. (1991) The active site of thrombin is altered upon binding to thrombomodulin. Two distinct structural changes are detected by fluorescence, but only one correlates with protein C activation. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 23016–23021 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Di Cera E. (2003) Thrombin interactions. Chest 124, 11S-17S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Di Cera E., Page M. J., Bah A., Bush-Pelc L. A., Garvey L. C. (2007) Thrombin allostery. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 9, 1291–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kamath P., Huntington J. A., Krishnaswamy S. (2010) Ligand binding shuttles thrombin along a continuum of zymogen- and proteinase-like states. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 28651–28658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Di Cera E. (1998) Anticoagulant thrombins. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 340–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pozzi N., Vogt A. D., Gohara D. W., Di Cera E. (2012) Conformational selection in trypsin-like proteases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 22, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lechtenberg B. C., Johnson D. J., Freund S. M., Huntington J. A. (2010) NMR resonance assignments of thrombin reveal the conformational and dynamic effects of ligation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 14087–14092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krishnaswamy S., Church W. R., Nesheim M. E., Mann K. G. (1987) Activation of human prothrombin by human prothrombinase. Influence of factor Va on the reaction mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 3291–3299 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Orcutt S. J., Krishnaswamy S. (2004) Binding of substrate in two conformations to human prothrombinase drives consecutive cleavage at two sites in prothrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54927–54936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Doyle M. F., Mann K. G. (1990) Multiple active forms of thrombin. IV. Relative activities of meizothrombins. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 10693–10701 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cote H. C., Bajzar L., Stevens W. K., Samis J. A., Morser J., MacGillivray R. T., Nesheim M. E. (1997) Functional characterization of recombinant human meizothrombin and Meizothrombin(desF1). Thrombomodulin-dependent activation of protein C and thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI), platelet aggregation, antithrombin-III inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 6194–6200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walker R. K., Krishnaswamy S. (1994) The activation of prothrombin by the prothrombinase complex. The contribution of the substrate-membrane interaction to catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 27441–27450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gomori G. (1942) A modification of the colorimetric phosphorus determination for use with the photoelectric colorimeter. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 27, 955–960 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baugh R. J., Krishnaswamy S. (1996) Role of the activation peptide domain in human factor X activation by the extrinsic Xase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 16126–16134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orcutt S. J., Pietropaolo C., Krishnaswamy S. (2002) Extended interactions with prothrombinase enforce affinity and specificity for its macromolecular substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46191–46196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buddai S. K., Toulokhonova L., Bergum P. W., Vlasuk G. P., Krishnaswamy S. (2002) Nematode anticoagulant protein c2 reveals a site on factor Xa that is important for macromolecular substrate binding to human prothrombinase. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 26689–26698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lundblad R. L., Kingdon H. S., Mann K. G. (1976) Thrombin. Methods Enzymol. 45, 156–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boskovic D. S., Krishnaswamy S. (2000) Exosite binding tethers the macromolecular substrate to the prothrombinase complex and directs cleavage at two spatially distinct sites. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38561–38570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Toso R., Camire R. M. (2004) Removal of B-domain sequences from factor V rather than specific proteolysis underlies the mechanism by which cofactor function is realized. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21643–21650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bradford H. N., Micucci J. A., Krishnaswamy S. (2010) Regulated cleavage of prothrombin by prothrombinase: repositioning a cleavage site reveals the unique kinetic behavior of the action of prothrombinase on its compound substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 328–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lu G., Chhum S., Krishnaswamy S. (2005) The affinity of protein C for the thrombin·thrombomodulin complex is determined in a primary way by active site-dependent interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 15471–15478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krishnaswamy S., Vlasuk G. P., Bergum P. W. (1994) Assembly of the prothrombinase complex enhances the inhibition of bovine factor Xa by tick anticoagulant peptide. Biochemistry 33, 7897–7907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kamath P., Krishnaswamy S. (2008) Fate of membrane-bound reactants and products during the activation of human prothrombin by prothrombinase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30164–30173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bode W., Mayr I., Baumann U., Huber R., Stone S. R., Hofsteenge J. (1989) The refined 1.9 Å crystal structure of human α-thrombin: interaction with d-Phe-Pro-Arg chloromethylketone and significance of the Tyr-Pro-Pro-Trp insertion segment. EMBO J. 8, 3467–3475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Degen S. J., MacGillivray R. T., Davie E. W. (1983) Characterization of the complementary deoxyribonucleic acid and gene coding for human prothrombin. Biochemistry 22, 2087–2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Price P. A. (1983) Analysis for γ-carboxyglutamic acid. Methods Enzymol. 91, 13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Di Scipio R. G., Hermodson M. A., Davie E. W. (1977) Activation of human factor X (Stuart factor) by a protease from Russell's viper venom. Biochemistry 16, 5253–5260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mann K. G., Elion J., Butkowski R. J., Downing M., Nesheim M. E. (1981) Prothrombin. Methods Enzymol. 80, 286–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Betz A., Krishnaswamy S. (1998) Regions remote from the site of cleavage determine macromolecular substrate recognition by the prothrombinase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10709–10718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Elbrecht A., Rowley D., O'Malley B. W. (1987) Irish Cream liqueur as a blocking agent in DNA dot blots. Boehringer Mannheim Biochemica 4, 12–13 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Johnson K. A., Simpson Z. B., Blom T. (2008) Global kinetic explorer: a new computer program for dynamic simulation and fitting of kinetic data. Anal. Biochem. 387, 20–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Doyle M. F., Haley P. E. (1993) Meizothrombin: active intermediate formed during prothrombinase-catalyzed activation of prothrombin. Methods Enzymol. 222, 299–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nesheim M. E., Prendergast F. G., Mann K. G. (1979) Interactions of a fluorescent active-site-directed inhibitor of thrombin: dansylarginine N-(3-ethyl-1,5-pentanediyl)amide. Biochemistry 18, 996–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Krishnaswamy S., Mann K. G., Nesheim M. E. (1986) The prothrombinase-catalyzed activation of prothrombin proceeds through the intermediate meizothrombin in an ordered, sequential reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 8977–8984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hibbard L. S., Nesheim M. E., Mann K. G. (1982) Progressive development of a thrombin inhibitor binding site. Biochemistry 21, 2285–2292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Izaguirre G., Swanson R., Raja S. M., Rezaie A. R., Olson S. T. (2007) Mechanism by which exosites promote the inhibition of blood coagulation proteases by heparin-activated antithrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33609–33622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bianchini E. P., Orcutt S. J., Panizzi P., Bock P. E., Krishnaswamy S. (2005) Ratcheting of the substrate from the zymogen to proteinase conformations directs the sequential cleavage of prothrombin by prothrombinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10099–10104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Anderson P. J., Bock P. E. (2003) Role of prothrombin fragment 1 in the pathway of regulatory exosite I formation during conversion of human prothrombin to thrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 44489–44495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Higgins D. L., Lewis S. D., Shafer J. A. (1983) Steady state kinetic parameters for the thrombin-catalyzed conversion of human fibrinogen to fibrin. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 9276–9282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shim K., Zhu H., Westfield L. A., Sadler J. E. (2004) A recombinant murine meizothrombin precursor, prothrombin R157A/R268A, inhibits thrombosis in a model of acute carotid artery injury. Blood 104, 415–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Martin P. D., Malkowski M. G., Box J., Esmon C. T., Edwards B. F. (1997) New insights into the regulation of the blood clotting cascade derived from the x-ray crystal structure of bovine meizothrombin des F1 in complex with PPACK. Structure 5, 1681–1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Papaconstantinou M. E., Gandhi P. S., Chen Z., Bah A., Di Cera E. (2008) Na+ binding to meizothrombin desF1. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3688–3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Huntington J. A. (2009) Slow thrombin is zymogen-like. J. Thromb Haemost. 7, Suppl. 1, 159–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Page M. J., Di Cera E. (2006) Role of Na+ and K+ in enzyme function. Physiol. Rev. 86, 1049–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Di Cera E. (2009) Serine proteases. IUBMB Life 61, 510–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kroh H. K., Tans G., Nicolaes G. A., Rosing J., Bock P. E. (2007) Expression of allosteric linkage between the sodium ion binding site and exosite I of thrombin during prothrombin activation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16095–16104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brufatto N., Nesheim M. E. (2003) Analysis of the kinetics of prothrombin activation and evidence that two equilibrating forms of prothrombinase are involved in the process. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6755–6764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kim P. Y., Nesheim M. E. (2007) Further evidence for two functional forms of prothrombinase each specific for either of the two prothrombin activation cleavages. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 32568–32581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lee C. J., Wu S., Eun C., Pedersen L. G. (2010) A revisit to the one form kinetic model of prothrombinase. Biophys. Chem. 149, 28–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bevington P. R., Robinson K. D. (1992) Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences, 2 Ed., pp. 38–52, McGraw-Hill, New York [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.