Background: Molecular signals that control how long activated lymphocytes remain activated are unknown.

Results: Unphosphorylated STAT3 interacts with and sequesters pFoxO1/pFoxO3a in cytoplasm whereas pSTAT3 terminates TCR activation by inducing nuclear localization of FoxO1/FoxO3a and p27Kip1 expression.

Conclusion: STAT3/FoxO are gatekeepers that determine whether T cells remain quiescent or proliferate.

Significance: STAT3 is convergence point for mechanisms that regulate cellular quiescence and lymphocyte activation.

Keywords: Cellular Immune Response, Cytokine, FoxO, Interleukin, STAT3, T Cell

Abstract

An important feature of the adaptive immune response is its remarkable capacity to regulate the duration of inflammatory responses, and effector T cells have been shown to limit excessive immune responses by producing anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-27. However, how anti-inflammatory cytokines mediate their suppressive activities is not well understood. In this study, we show that STAT3 contributes to mechanisms that control the duration of T cell proliferation by regulating the subcellular location of FoxO1 and FoxO3a, two Class O Forkhead transcription factors that mediate lymphocyte quiescence and inhibit T cell activation. We show that active FoxO1 and FoxO3a reside exclusively in the nucleus of naïve T cells whereas inactive pFoxO1 and pFoxO3a were most abundant in activated T cells and sequestered in their cytoplasm in association with unphosphorylated STAT3 (U-STAT3) and 14-3-3. We further show that FoxO1/FoxO3a rapidly relocalized into the nucleus in response to pSTAT3 activation by IL-6 or IL-10, and the accumulation of FoxO1/FoxO3a in their nuclei coincided with increased expression of p27Kip1 and p21WAF1. STAT3 inhibitors completely abrogated cytokine-induced translocation of FoxO1/FoxO3a into the nucleus. In naïve or resting STAT3-deficient T cells, expression of pFoxO1/pFoxO3a was predominantly in the cytoplasm and correlated with defects in p27Kip1 and p21WAF1 expression, suggesting requirement of STAT3 for importation or retention of FoxO in the nucleus and attenuation of lymphocyte proliferation. Taken together, these results suggest that U-STAT3 collaborates with 14-3-3 to sequester pFoxO1/pFoxO3a in cytoplasm and thus prolong T cell activation, whereas pSTAT3 activation by anti-inflammatory cytokines would curtail the duration of TCR activation and re-establish lymphocyte quiescence by inducing nuclear localization of FoxO1/FoxO3a and FoxO-mediated expression of growth-inhibitory proteins.

Introduction

Class O Forkhead transcription factors (FoxO)2 are important T lymphocyte quiescence factors present at high levels in the nucleus of naïve and resting T cells (1, 2). Constitutive activation of FoxO1 and FoxO3a contributes to the maintenance of naïve or resting T lymphocytes in the quiescent state by up-regulating the expression of p27Kip1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that promotes cell cycle arrest (2–4). FoxO proteins also prevent T cell activation and proliferation by up-regulating IκB expression, promoting IκB-mediated sequestration of NF-κB in the cytoplasm, and inhibiting transcription of IL-2 (4). However, upon TCR engagement, PI3K/AKT phosphorylates and inactivates FoxO, induces their expulsion from the nucleus by the 14-3-3 scaffolding protein, and thereby overrides the block on T cell activation imposed by FoxO proteins (2, 5). Binding of 14-3-3 to the FoxO proteins not only promotes nuclear export of the pFoxO·14-3-3 complex, it inhibits the nuclear import of FoxO by interfering with the function of its nuclear localization signal (NLS) (6). Diminution in p27Kip1 and IκB levels caused by FoxO inactivation allows cell cycle progression, IL-2 production, and initiation of T cell proliferation (2, 7, 8). However, unbridled activation of T cells must be avoided. Thus, effector T cells have been shown to limit T cell proliferative responses by producing the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (9). However, the exact mechanisms that terminate T cell activation and mediate suppressive activities of IL-10 are not well understood.

STAT3 is an abundant latent cytoplasmic transcription factor. Similar to FoxO proteins, biological activity of STAT3 is regulated by post-transcriptional mechanisms that regulate their subcellular localization (10). Prior to activation, unphosphorylated STAT3 (U-STAT3) exists in the cytoplasm as stable antiparallel dimers, which are structurally distinct from the activated tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) dimer (11, 12). After activation, the pSTAT3 dimer assumes a parallel conformation, unmasks its NLS, allowing it to enter the nucleus via importin-α3-dependent transport to activate gene transcription (12). Although the U-STAT3 protein also enters the nucleus, it is rapidly transported back to the cytoplasm by the nuclear export factor, Crm1 (13). Although transcription-dependent functions of pSTAT3 are well documented (14), it is only recently that transcription-independent function of U-STAT3 in the cytoplasm was discovered (15, 16). A high level of U-STAT3 in IL-6-stimulated T cells was found to compete with IκB for p65/p50 to form a U-STAT3·U-NF-κB complex, and this finding has led to significant interest in identifying other transcription factors that might also interact with U-STAT3 in the cytoplasm. We recently showed that STAT3 inhibits T cell proliferation by enhancing expression of FoxO1 and FoxO3a, leading to increased expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins (17). We also showed that it limits the expansion of activated T cells by constraining their ability to produce IL-2 through FoxO1- and FoxO3a-dependent increases in IκB and IκB-mediated sequestration of NF-κB in the cytoplasm (17). However, we did not examine whether STAT3 also regulated activities of FoxO protein through direct protein-protein interactions. In view of the discovery of transcription-independent functions of U-STAT3 in the cytoplasm (15, 16), it was of interest to determine whether U-STAT3 interacts with pFoxO proteins in the cytoplasm.

In this report, we describe a novel mechanism by which U-STAT3 contributes to mechanisms that sequester pFoxO1 and pFoxO3a in the cytoplasm and thus prolonged duration of TCR activation. However, we found that exposure of activated T cells to cytokines that activate pSTAT3 induced translocation of FoxO1 and FoxO3a into the nucleus and led to enhanced expression of growth-inhibitory proteins. Data presented in this report thus suggest a mechanism by which anti-inflammatory cytokines terminate T cell activation and re-establish lymphocyte quiescence.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) were from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice with conditional deletion of STAT3 in the CD4+ T cell compartment (STAT3KO) have been described previously (18). Animal care and use were in compliance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Analysis of CD4+ T-helper Cells

CD4+ T cells isolated from spleen or lymph nodes (>98%) were activated in plate-bound anti-CD3 Abs (10 μg/ml) and soluble anti-CD28 Abs (3 μg/ml) without exogenous cytokines or Abs (Th0 condition) as described (18). In some experiments the cells were activated in plate-bound anti-CD3 Abs (10 μg/ml) and soluble anti-CD28 Abs (3 μg/ml) under Th1, Th2, or Th17 polarization condition: Th1 condition, anti-CD3/CD28 + anti-IL-4 Abs (10 μg/ml) and IL-12 (10 ng/ml); Th17 condition, anti-CD3/CD28 + IL-6 (10 ng/ml) + TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) + anti-IFN-γ Abs (10 μg/ml) + anti-IL-4 Abs (10 μg/ml); Th2 condition, anti-CD3/CD28 + anti-IFN-γ Abs (10 μg/ml) and IL-4 (10 ng/ml). For intracellular cytokine detection, cells were restimulated for 5 h with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (20 ng/ml)/ionomycin (1 μm). Golgi-stop was added in the last hour, and intracellular cytokine staining was performed using BD Biosciences Cytofix/Cytoperm kit as recommended (BD Pharmingen). FACS analysis was performed on a Becton-Dickinson FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) using monoclonal antibodies specific to CD4, CD62L, CD44, CD45RB, IL-17, and IFN-γ mAbs and corresponding isotype control Abs (BD Pharmingen) as described previously (19).

Cytokine Analysis

WT or STAT3KO mouse T cells were activated for 4 days with anti-CD3/CD28 Abs under Th1 or Th2 polarization condition, and multiplex ELISA of supernatants for IL-2 secretion was performed using a commercial ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as described (19).

Western Blot and Immunoprecipitation Analysis

Preparation of whole cell lysates and immunodetection were performed as described (20). Briefly, samples (20–40 μg/lane) were fractionated on 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE, and antibodies used were: STAT3, pSTAT3, pFoxO1, pFoxO3a (Cell Signaling Technology); p27Kip1, GAPDH, Oct1, β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). For some experiments nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents from Pierce, and the quality of the preparations was always verified by analysis of proteins differentially enriched in the nucleus (Oct1) or the cytoplasm (GAPDH). For immunoprecipitation analysis, 0.2 mg of whole cell extract was incubated with Dynabeads protein G and anti-FoxO3a or anti-pFoxO1(Thr-24)/FoxO3a (Thr-32) Abs as recommended (Dynal/Invitrogen). Preimmune serum was used in parallel as controls, and signals were detected with HRP-conjugated secondary F(ab′)2 Ab (Zymed Laboratories Inc.) using the ECL-PLUS system (Amersham Biosciences).

Cell Transfection

CD4+ T cells were transiently transfected with plasmids expressing WT FoxO1-GFP fusion proteins (Addgene, Cambridge, MA) (5) or truncated FoxO1 in-frame with GFP as described (21) using the Nucleofector device and corresponding kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD).

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy

Purified CD4+ T cells from C57BL6 mice were grown on chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) and stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 Abs for varying amounts of time in the presence or absence of exogenous cytokines. Cells were fixed, blocked with 5% goat serum, and then incubated with primary antibodies (FoxO1, FoxO3a, pFoxO3a, STAT3, pSTAT3) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology or Cell Signaling. Slides were washed, incubated in Alexa Fluor 488- or Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated secondary Abs (Invitrogen) containing DAPI and examined on laser scanning confocal microscope as described (17).

RESULTS

STAT3 Interacts with FoxO Proteins in the Cytoplasm of Activated T Cells

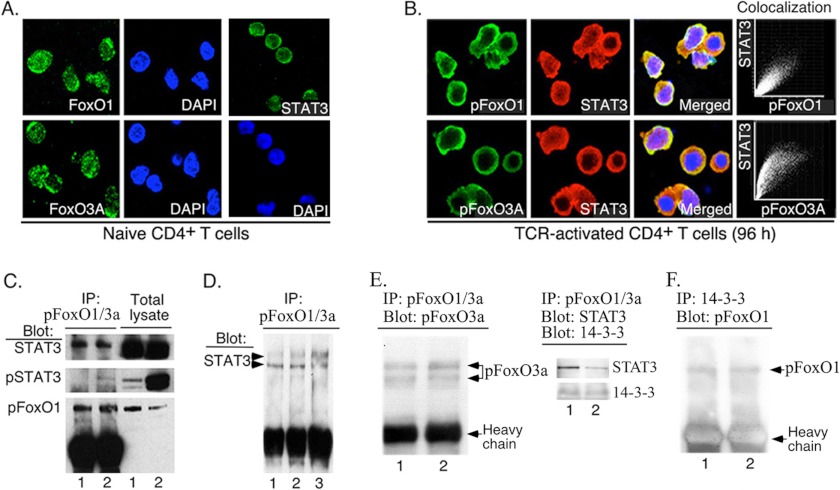

In a previous study, we showed that STAT3 induced the transcription of FoxO1 and FoxO3a genes and that the resulting increase in expression of FoxO1 and FoxO3a enhanced their transcriptional activities in T cells (17). In this study, we have investigated whether STAT3 interacts with FoxO proteins and whether such protein-protein interactions can enhance activities of FoxO proteins in T cells. We stimulated mouse naïve CD4+ T cells with anti-CD3/CD28 for 4 days and analyzed the effects of TCR activation on the spatial localization of FoxO1, FoxO3a, U-STAT3, and pSTAT3 proteins by confocal microscopy. In naïve CD4+ T cells most FoxO1 and FoxO3a were detected in the nucleus (Fig. 1A) but the FoxO proteins relocalized to the cytoplasm after 96-h stimulation (Fig. 1B), consistent with TCR-mediated expulsion of pFoxO from the nucleus of the activated T cells (3). Most of the STAT3 in 96-h activated T cells were in the cytoplasm; and as indicated by the co-localization plots and the yellow/brownish signals of the merged images, both pFoxO1 and pFoxO3a co-localize with U-STAT3 in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1B). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the co-localization plots might simply reflect fortuitous spatial co-localization of the proteins in the cytoplasm. To determine whether STAT3 interacts with pFoxO, we stimulated mouse naïve CD4+ T cells with anti-CD3/CD28 for 4 days, prepared cytoplasmic extracts, and performed immunoprecipitations using Abs specific to pFoxO1/pFoxO3a as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitates using Abs specific to STAT3 or pSTAT3 demonstrated that pFoxO1/pFoxO3a and FoxO3a interacted with U-STAT3 and pSTAT3 (Fig. 1C) regardless of TCR activation. To further confirm our results showing that U-STAT3 interacts with FoxO, we stimulated human Jurkat T cells and performed immunoprecipitation using FoxO3a antibodies. Again, Western blot analysis using STAT3-specific Abs established the direct interaction between U-STAT3 and pFoxO3a (Fig. 1D), underscoring the potential importance of the interaction between U-STAT3 and pFoxO1/FoxO3a proteins in human and mouse T cells. In line with a report that 14-3-3ζ associates with STAT3 (22), we show that 14-3-3 interacts with the FoxO·STAT3 complex (Fig. 1, E and F).

FIGURE 1.

STAT3 co-localized and interacted with pFoxO1 and pFoxO3a in the cytoplasm of activated T cells. A and B, WT naïve CD4+ T cells (A) were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 96 h (B). Cells were fixed and stained with DAPI prior to visualization of subcellular localization of FoxO (green), STAT3 (red), or nuclei (blue) by immunofluorescence on laser confocal microscope. C, whole cell extracts from naïve (lane 1) or 96 h (lane 2) TCR-stimulated primary CD4+ T cells were precipitated (IP) with anti-pFoxO1/pFoxO3a Abs and analyzed by Western blotting (Blot) with anti-STAT3, anti-pSTAT3, or anti-pFoxO1 Ab. D, interactions of FoxO3a with STAT3 in whole cell extracts of resting (lane 1), TCR-activated (lane 2) human Jurkat T cells, or activated mouse T cells (lane 3) were analyzed by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. E and F, co-immunoprecipitation was performed in anti-CD3/CD28-activated CD3+ T cells (lane 1) and AE7 CD4+ T cell lines (lane 2).

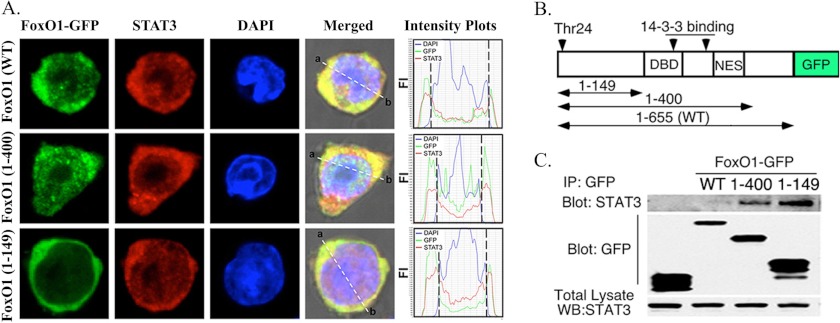

FoxO proteins contain several domains and critical residues that contribute to their nuclear localization or nuclear exclusion, including the NLS, DNA binding domain, and a leptomycin-B-sensitive nuclear export signal (21). To characterize regions of the FoxO1 protein that interact with STAT3, we transfected mouse primary T cells with cDNA constructs expressing fusion proteins consisting of full-length or truncated FoxO1 in-frame with GFP (Fig. 2A). Full-length FoxO1-(1–655)- and FoxO1-(1–400)-GFP contain a DNA binding domain and nuclear export signal, whereas FoxO1-(1–149)-GFP does not contain these amino acid sequences (Fig. 2B) (21). However, FoxO1-(1–149)-GFP contains the critical Thr-24 residue that is required for binding to 14-3-3 or Crm1 and nuclear exclusion of FoxO1 (21). As indicated on fluorescence-intensity plots, full-length FoxO1-(1–655)- and FoxO1-(1–400)-GFP localized to the cytoplasm and to a lesser extent in nucleus of activated T cells (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, FoxO1-(1–149)-GFP localizes exclusively to the cytoplasm of the activated T cells, consistent with a previous report (21). Nonetheless, each of the FoxO1-GFPs co-localized with STAT3 in cytoplasm (yellow signals in merged image; Fig. 2A). Furthermore, immunoprecipitation analysis revealed direct interactions between STAT3 and each of the three FoxO-GFP recombinant proteins, with the strongest intensity observed with FoxO1-(1–149) (Fig. 2C, top panel). However, Western blot analysis detected higher amount of FoxO1-(1–49) in transfected T cells, suggesting that the strong interaction observed with STAT3 derived in part from higher transfection efficiency of FoxO1 (1–149) (Fig. 2C, bottom panel). The binding of STAT3 to residues close to the binding site of 14-3-3 suggests possible formation of a novel transcription factor complex comprising of pFoxO, U-STAT3, and 14-3-3 in the cytoplasm. Taken together with results of a recent study showing that STAT3 interacts with 14-3-3ζ (22), these results suggest that STAT3 may stabilize interactions between 14-3-3 and pFoxO and thus contribute to mechanisms that sequester pFoxO1/pFoxO3a in the cytoplasm of activated T cells.

FIGURE 2.

STAT3 interacts with the N-terminal 149 amino acids of FoxO1. A, T cells were transiently transfected with plasmids expressing full-length or truncated FoxO1 in-frame with GFP, and subcellular localization of STAT3 or FoxO fusion proteins was visualized by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. B, schematic description of the FoxO1 constructs in context of their functional domains is shown at the top of figure. DNA-binding domain (DBD), nuclear export signal (NES), and 14-3-3 binding sequences are shown. C, whole cell extracts from T cells expressing FoxO1-GFP fusion proteins were precipitated (IP) with anti-GFP Abs, and precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting (Blot; WB) with anti-STAT3 or anti-GFP Abs. Results are representative of >3 independent experiments.

IL-10- and IL-6-induced Nuclear Translocation of FoxO1/FoxO3a Requires STAT3 Activation

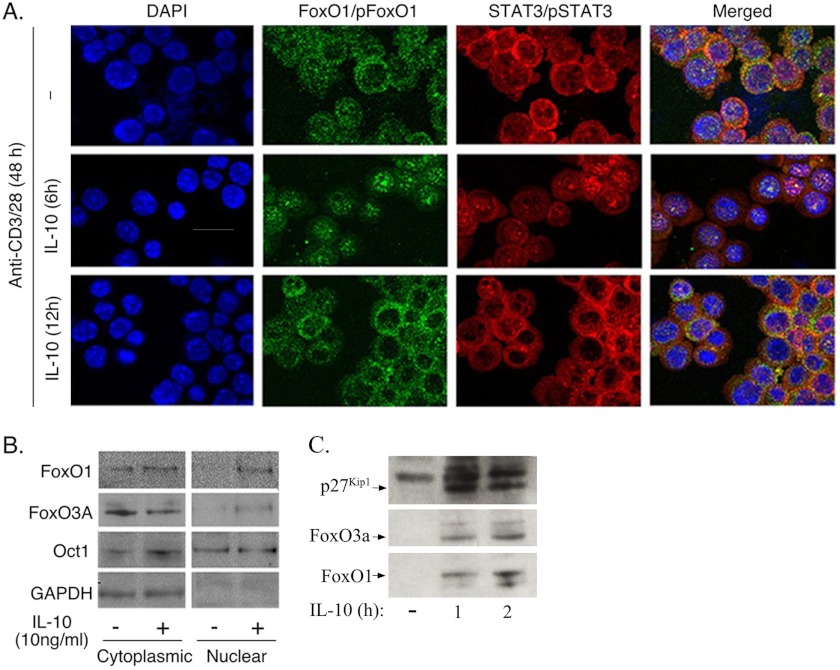

Effector T cells limit tissue injury during infection by producing cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-27 that induce IL-10 (23, 24). IL-10 in turn suppresses prolonged inflammatory responses by curtailing T cell proliferation through STAT3-dependent mechanisms (9, 25, 26). In this study, we examined whether tyrosine phosphorylation of U-STAT3 by IL-10 could destabilize the complex interactions between pFoxO, U-STAT3, and 14-3-3 in the cytoplasm and promote nuclear localization of FoxO. We therefore stimulated T cells with IL-10 after TCR activation with anti-CD3/CD28 and examined whether the activation of STAT3 by IL-10 would facilitate nuclear localization of FoxO. In the cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 48 h, we detected intense pFoxO-specific (intense green signals) and STAT3-specific (intense red signals) immunoreactivity in the cytoplasm, suggesting the co-localization (intense orange/yellow signals in merged image) of pFoxO1 and U-STAT3 in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3A). However, in the T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 42 h and then exposed to IL-10 for an additional 6 h, we detected a substantial increase in the number of activated T cells expressing FoxO1 and pSTAT3 in the nucleus (Fig. 3A, middle panels). Interestingly, in T cells that were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 36 h followed by exposure to IL-10 for an additional 12 h, the FoxO1 proteins relocalized to the cytoplasm and co-localized with U-STAT3 (Fig. 3A, bottom panels). The latter result suggests that the IL-10-mediated nuclear localization of FoxO1 is transient and temporally correlates with the relatively short duration of pSTAT3 signaling. To confirm these results biochemically, we prepared nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from the T cells activated in the presence or absence of IL-10. In line with our immunocytochemical data, Western blot analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts detected increases in FoxO1 and FoxO3a proteins in the nucleus of IL-10-treated T cells but not in nuclei of the untreated T cells (Fig. 3B). Because FoxO proteins maintain lymphocytes in a quiescent state, in part, by up-regulating the expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins, we examined whether exposure of activated T cells to IL-10 would enhance their expression. We detected increase in the level of p27Kip1 (Fig. 3C), indicating a link between IL-10-induced increase of the nuclear localization of FoxO1 and FoxO3a and enhanced expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p27Kip1.

FIGURE 3.

FoxO1 and STAT3 relocalized into the nucleus in response to IL-10 stimulation. Mouse naïve CD4+ T cells were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 48 h, and IL-10 was added to some cultures after 36 or 42 h. Cells were fixed and stained with DAPI, and spatial localization of FoxO (green), STAT3 (red), or nuclei (blue) was visualized by confocal microscopy (A). B and C, subcellular localization of FoxO1, FoxO3a, or p27Kip1 protein was also detected by Western blotting. Results are representative of >3 independent experiments.

Another cytokine that mediates its biological activities through activation of STAT3 is IL-6 (11). We therefore examined whether IL-6 can also enhance nuclear localization of FoxO proteins. Likewise, exposure of activated T cells to IL-6 induced translocation of FoxO3a and pSTAT3 into the nucleus (Fig. 4A), suggesting that this may be a common attribute of cytokines that activate STAT3. To firmly establish the role of STAT3 in mediating FoxO translocation into the nucleus, we examined whether two distinct STAT3 inhibitors, ORLL-NIH001 and STAT3VIII, could abrogate IL-6-mediated nuclear translocation of FoxO3a. ORLL-NIH001 is a synthetic small molecule that inhibits STAT3 and STAT3-mediated diseases whereas STAT3VIII is a cell-permeable porphyrin compound that binds STAT3 and prevents STAT3 SH2 domain-mediated ligand binding and dimerization (27). Both inhibitors strongly inhibited IL-6-induced STAT3 nuclear translocation and DNA binding activity with no effect on other STAT proteins (27). We stimulated naïve CD4+ T cells with anti-CD3/CD28 Abs in the presence or absence IL-6 and show here that the IL-6-induced nuclear localization of FoxO3a was abrogated by ORLL-NIH001 or STAT3VIII (Fig. 4B), providing further evidence for the involvement of STAT3 in cytokine-mediated nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling of FoxO proteins.

FIGURE 4.

FoxO3a and STAT3 relocalized into the nucleus in response to IL-6 by STAT3-dependent mechanism. A, mouse naïve CD4+ T cells were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 48 h, and IL-6 was added to some cultures after 42 h. B, mouse naïve CD4+ T cells were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 48 h. IL-6 and/or STAT3 inhibitors (STAT3VIII and ORLL-NIH001) were added to some cultures after 42 h as indicated. Cells were fixed and stained with DAPI prior to visualization of subcellular localization of FoxO (green), STAT3 (red), or nuclei (blue) by confocal microscopy. Results are representative of >3 independent experiments.

Loss of STAT3 Results in Nuclear Exclusion of FoxO1 and FoxO3a in Naïve CD4+ T Cells

We next used STAT3-deficient T cells to examine directly the role of STAT3 in nuclear import of FoxO proteins in T cells. Analysis of subcellular locations of FoxO proteins revealed that both FoxO1 and FoxO3a predominantly localized to the nucleus of WT naïve T cells whereas the FoxO proteins were detected mainly in the cytoplasm of the STAT3KO naïve T cells (Fig. 5A). However, FoxO1 and FoxO3a levels were much reduced in STAT3KO T cells (Fig. 5A), consistent with previous report of STAT3-mediated induction of the expression of FoxO1 and FoxO3a (17). We also detected a marked increase in the expression of cell surface markers of lymphocyte activation on STAT3KO cells (Fig. 5B), suggesting that STAT3-deficient naïve T cells are preactivated. Thus, the sequestration of pFoxO1 and pFoxO3a in the cytoplasm of naïve STAT3KO T cells derived in part from their preactivated state and may underscore the requirement of STAT3 for importation of FoxO proteins into the nucleus. It is however interesting that the overall reduction in FoxO proteins and their sequestration in the cytoplasm STAT3KO T cells correlate with the down-regulation of p27Kip1 and p21WAF1 (Fig. 5C). Analysis of T cells stimulated for 4 days further revealed an exaggerated increase in IL-2 production (Fig. 5D) and marked increase in expression of effector cytokines, IFN-γ and IL-17 (Fig. 5E) by STAT3KO T cells. Together, these results suggest that loss of STAT3-mediated up-regulation of FoxO1/FoxO3a led to a decrease in the cell cycle inhibitor, p27Kip1, and an inability to attenuate or terminate proliferative responses of STAT3KO T cells.

FIGURE 5.

Loss of STAT3 correlates with nuclear exclusion of FoxO1 and FoxO3a. A, WT or STAT3KO naïve CD4+ T cells were fixed and stained with DAPI, and subcellular location of FoxO (green) or nuclei (blue) was visualized by confocal microscopy. B and C, cell surface expression of activation markers on naïve or TCR-activated T cells was analyzed by FACS (B), and expression of p27Kip1 and p21WAF1 was analyzed by Western blotting (C). D and E, CD4+ T cells were propagated under Th1, Th2, or Th17 polarization condition for 4 days and then analyzed for IL-2 secretion by ELISA (D) or intracellular cytokine expression (E). Numbers in quadrants (B and E) indicate percent of T cells expressing IL-17, IFN-γ, and/or IL-2. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have provided data showing that STAT3 regulates nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling of Class O Forkhead transcription factors and may therefore be involved in mechanisms that terminate or regulate the duration T cell activation. We show that active unphosphorylated FoxO proteins reside predominantly in the nucleus of naïve T cells (Figs. 1A and 5A) and that in response to TCR activation FoxO proteins become phosphorylated (pFoxO) and relocalize into the cytoplasm. It is notable that pFoxO1 and pFoxO3a remained sequestered in the cytoplasm through 4 days of T cell activation, suggesting that T lymphocytes can be maintained in the activated state, insofar as pFoxO proteins remain sequestered in the cytoplasm. The pFoxO1 and pFoxO3a proteins co-localized with the abundant latent cytoplasmic transcription factor, U-STAT3 (Fig. 1B), and we demonstrate that U-STAT3 interacts directly with pFoxO1 and pFoxO3a in the cytoplasm of activated T cells (Fig. 1, C and D). We have mapped the STAT3-FoxO1 interaction site to the N-terminal amino acids 1–149 of FoxO1 (Fig. 2C), a region of the FoxO1 protein that contains binding sites for the 14-3-3 scaffolding protein. Because STAT3 also interacts with 14-3-3 proteins (Fig. 1, E and F) (22), it may well be that STAT3 plays a role in stabilizing interactions between 14-3-3 and inactive pFoxO proteins, thereby contributing to mechanisms that sequester pFoxO1 and pFoxO3a in the cytoplasm of activated T cells. However, an equally plausible explanation for existence of U-STAT3 in a complex with pFoxO and 14-3-3 in the cytoplasm may be to provide a rapid mechanism for attenuating T cell activation. Thus, U-STAT3 may serve as a target for tyrosine phosphorylation by cytokines leading to disruption of the protein-protein interactions that promote sequestration of pFoxO proteins in the cytoplasm.

It is intriguing that cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-27 that suppress autoimmune inflammation inhibit T cell proliferation by inducing STAT3-mediated production of IL-10 (23, 24, 28). Although exact mechanisms that are responsible for the suppressive activities of IL-10 are still not clear, the primary mechanism is through STAT3-dependent transcriptional activation of growth-inhibitory genes (25, 26). Consistent with the notion that activation of STAT3 might contribute to mechanisms that terminate TCR activation, data presented here reveal that exposure of activated T cells to IL-10 induced rapid relocalization of pFoxO1 and pFoxO3a from the cytoplasm into the nucleus (Fig. 3, A and B). Moreover, the resulting increase of FoxO1 and FoxO3a in the nucleus coincided with elevated levels of p27Kip1 (Fig. 3C). In this context, it is interesting that FoxO proteins were detected mainly in the cytoplasm of the STAT3KO naïve T cells (Fig. 5A), suggesting a potential role of STAT3 in nuclear import and/or retention of FoxO in nuclei of T cells. We have also shown that loss of STAT3 correlates with the down-regulation of FoxO1 and FoxO3a, decrease in the levels of cell cycle inhibitors, p27Kip1 and p21WAF1 and inability to attenuate or terminate T cell proliferative responses (17).

U-STAT3 exists in the cytoplasm as antiparallel dimers, and tyrosine phosphorylation induces them to assume a parallel conformation (12). Although STAT3 regulates cellular processes mainly through transcription-dependent functions of pSTAT3 in the nucleus, our data showing that U-STAT3 binds and may contribute to the sequestration of pFoxO proteins in the cytoplasm of activated T cells suggest a potentially important transcription-independent function of U-STAT3 in T cells. It is therefore of note that U-STAT3, induced to a high level due to activation of the STAT3 gene in response to ligands such as IL-6, binds to unphosphorylated NF-κB, in competition with IκB, to form a novel transcription factor complex in the cytoplasm (14). Interestingly, it was also shown that the U-STAT3·p65/p50 trimolecular complex subsequently relocalizes from the cytoplasm into the nucleus with help from the nuclear localization signal of STAT3 and importin-α3-mediated mechanisms (14). Similar to IκB interaction with and sequestration of unphosphorylated NF-κB in the cytoplasm, members of the 14-3-3 family proteins interact with and sequester pFoxO proteins in the cytoplasm (6, 29). In concert with a recent report showing that 14-3-3ζ interacts with STAT3 and regulates its functions in plasma cells (22), we show here that 14-3-3 interacts with the FoxO·STAT3 complex.

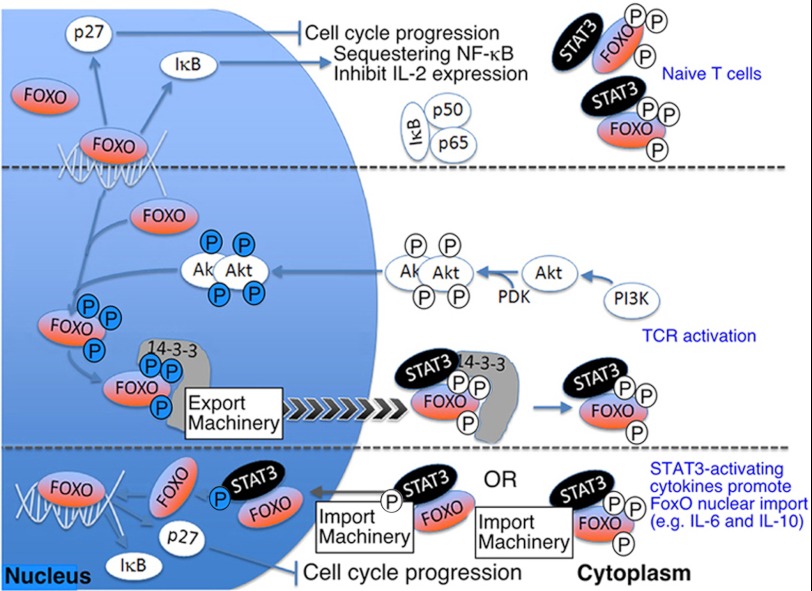

Taken together with our results showing the binding of STAT3 to the N-terminal region of FoxO1 that also interacts with 14-3-3, it may well be that an increase in pSTAT3/U-STAT3 in response to IL-10 or IL-6 signaling might promote formation of a more stable STAT3·pFoxO complex, with subsequent accumulation of the complex in the nucleus aided by the piggybacking of pFoxO on pSTAT3 NLS. Clearly, further studies are required to appreciate fully functional implications of the interaction between STAT3 and FoxO proteins in T cells. Nevertheless, data presented here suggest STAT3 as a convergence point for mechanisms that regulate cellular quiescence and T cell activation (Fig. 6), with STAT3 serving as a gatekeeper that determines whether T cells remain quiescent or proliferate by modulating FoxO nuclear/cytoplasmic localization in response to TCR and cytokine signals.

FIGURE 6.

A model for the regulation of the duration of T cell activation. Top panel, constitutive activation of FoxO1 and FoxO3a in the nucleus contributes to maintenance of naïve or resting T cells in a quiescent state by (i) up-regulating expression of IκB and the cell cycle inhibitory protein p27Kip1, promoting IκB-mediated sequestration of NF-κB in the cytoplasm, and inhibiting IL-2 production. Middle panel, upon TCR activation, PI3K/AKT phosphorylates FoxO, mediates their expulsion to the cytoplasm where they are sequestered in a transcription factor complex comprising of pFoxO1/pFoxO3a, 14-3-3, and U-STAT3. Bottom panel, anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-10 induce STAT3 activation. Conformational change from anti-parallel U-STAT3 into parallel pSTAT3 conformation results in: (i) disruption of pFoxO·14-3-3·U-STAT3 complex/displacement of 14-3-3; (ii) unmasking of STAT3 NLS; (iii) translocation of FoxO and STAT3 proteins into the nucleus aided by piggybacking of FoxO/pFoxO on pSTAT3 NLS and importin-α3; (iv) FoxO-mediated transcription of growth-inhibitory genes (e.g. IκB, p27Kip1); (v) termination of T cell proliferation and reestablishment of lymphocyte quiescence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Terry Unterman (Northwestern University Medical School, Chicago) for providing FoxO1-GFP plasmids, Dr. Robert Fariss (NEI Institute Imaging Facility, National Institutes of Health) for assistance with confocal microscopy, Rashid M. Mahdi (Molecular Immunology Section, NEI, National Institutes of Health) for technical assistance, and Dr. Li Zhang (Molecular Immunology Section, NEI, National Institutes of Health) for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NEI and Intramural Research Programs.

- FoxO

- Class O Forkhead transcription factor

- NLS

- nuclear localization signal

- pSTAT3

- tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT3

- TCR

- T cell receptor

- U-STAT3

- unphosphorylated STAT3.

REFERENCES

- 1. Liu J. O. (2005) The yins of T cell activation. Sci. STKE 2005, re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coffer P. J., Burgering B. M. (2004) Forkhead-box transcription factors and their role in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 889–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brunet A., Bonni A., Zigmond M. J., Lin M. Z., Juo P., Hu L. S., Anderson M. J., Arden K. C., Blenis J., Greenberg M. E. (1999) Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell 96, 857–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lin L., Hron J. D., Peng S. L. (2004) Regulation of NF-κB, Th activation, and autoinflammation by the Forkhead transcription factor FoxO3a. Immunity 21, 203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stahl M., Dijkers P. F., Kops G. J., Lens S. M., Coffer P. J., Burgering B. M., Medema R. H. (2002) The Forkhead transcription factor FoxO regulates transcription of p27Kip1 and Bim in response to IL-2. J. Immunol. 168, 5024–5031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Silhan J., Vacha P., Strnadova P., Vecer J., Herman P., Sulc M., Teisinger J., Obsilova V., Obsil T. (2009) 14-3-3 protein masks the DNA binding interface of Forkhead transcription factor FoxO4. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19349–19360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dijkers P. F., Medema R. H., Pals C., Banerji L., Thomas N. S., Lam E. W., Burgering B. M., Raaijmakers J. A., Lammers J. W., Koenderman L., Coffer P. J. (2000) Forkhead transcription factor FKHR-L1 modulates cytokine-dependent transcriptional regulation of p27Kip1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 9138–9148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaplan M. H., Daniel C., Schindler U., Grusby M. J. (1998) STAT proteins control lymphocyte proliferation by regulating p27Kip1 expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 1996–2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O'Garra A., Vieira P. (2007) TH1 cells control themselves by producing interleukin-10. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 425–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Darnell J. E., Jr. (1997) STATs and gene regulation. Science 277, 1630–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Levy D. E., Darnell J. E., Jr. (2002) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 651–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mertens C., Darnell J. E., Jr. (2007) SnapShot: JAK-STAT signaling. Cell 131, 612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meyer T., Vinkemeier U. (2004) Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of STAT transcription factors. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 4606–4612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang J., Liao X., Agarwal M. K., Barnes L., Auron P. E., Stark G. R. (2007) Unphosphorylated STAT3 accumulates in response to IL-6 and activates transcription by binding to NFκB. Genes Dev. 21, 1396–1408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gao S. P., Bromberg J. F. (2006) Touched and moved by STAT3. Sci. STKE 2006, pe30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ng D. C., Lin B. H., Lim C. P., Huang G., Zhang T., Poli V., Cao X. (2006) STAT3 regulates microtubules by antagonizing the depolymerization activity of stathmin. J. Cell Biol. 172, 245–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oh H. M., Yu C. R., Golestaneh N., Amadi-Obi A., Lee Y. S., Eseonu A., Mahdi R. M., Egwuagu C. E. (2011) STAT3 protein promotes T cell survival and inhibits interleukin-2 production through up-regulation of Class O Forkhead transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 30888–30897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu X., Lee Y. S., Yu C. R., Egwuagu C. E. (2008) Loss of STAT3 in CD4+ T cells prevents development of experimental autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 180, 6070–6076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Amadi-Obi A., Yu C. R., Liu X., Mahdi R. M., Clarke G. L., Nussenblatt R. B., Gery I., Lee Y. S., Egwuagu C. E. (2007) Th17 cells contribute to uveitis and scleritis and are expanded by IL-2 and inhibited by IL-27/STAT1. Nat. Med. 13, 711–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Egwuagu C. E., Yu C. R., Zhang M., Mahdi R. M., Kim S. J., Gery I. (2002) Suppressors of cytokine signaling proteins are differentially expressed in Th1 and Th2 cells: implications for Th cell lineage commitment and maintenance. J. Immunol. 168, 3181–3187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao X., Gan L., Pan H., Kan D., Majeski M., Adam S. A., Unterman T. G. (2004) Multiple elements regulate nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling of FoxO1: characterization of phosphorylation- and 14-3-3-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Biochem. J. 378, 839–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang J., Chen F., Li W., Xiong Q., Yang M., Zheng P., Li C., Pei J., Ge F. (2012) 14-3-3ζ interacts with STAT3 and regulates its constitutive activation in multiple myeloma cells. PLoS One 7, e29554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fitzgerald D. C., Zhang G. X., El-Behi M., Fonseca-Kelly Z., Li H., Yu S., Saris C. J., Gran B., Ciric B., Rostami A. (2007) Suppression of autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system by interleukin 10 secreted by interleukin 27-stimulated T cells. Nat. Immunol. 8, 1372–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Awasthi A., Carrier Y., Peron J. P., Bettelli E., Kamanaka M., Flavell R. A., Kuchroo V. K., Oukka M., Weiner H. L. (2007) A dominant function for interleukin 27 in generating interleukin 10-producing anti-inflammatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 8, 1380–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Murray P. J. (2005) The primary mechanism of the IL-10-regulated antiinflammatory response is to selectively inhibit transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 8686–8691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Murray P. J. (2006) STAT3-mediated anti-inflammatory signalling. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 1028–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yu C. R., Lee Y. S., Mahdi R. M., Surendran N., Egwuagu C. E. (2012) Therapeutic targeting of STAT3 (signal transducers and activators of transcription 3) pathway inhibits experimental autoimmune uveitis. PLoS One 7, e29742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stumhofer J. S., Silver J. S., Laurence A., Porrett P. M., Harris T. H., Turka L. A., Ernst M., Saris C. J., O'Shea J. J., Hunter C. A. (2007) Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nat. Immunol. 8, 1363–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Obsil T., Obsilova V. (2008) Structure/function relationships underlying regulation of FOXO transcription factors. Oncogene 27, 2263–2275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]