Background: Cellular processes involved in healing injured skeletal muscle fibers are poorly understood.

Results: Using an improved quantitative membrane proteomics approach for cells and tissues, we have identified accumulation of mitochondria at the site of sarcolemma injury as a key requirement for myofiber healing.

Conclusion: Mitochondria are the earliest responders to myofiber injury.

Significance: This work identifies a novel function of mitochondria in muscle injury.

Keywords: Intracellular Trafficking, Mitochondria, Proteomics, Sarcolemma, Skeletal Muscle, Muscle Injury

Abstract

Skeletal muscles are proficient at healing from a variety of injuries. Healing occurs in two phases, early and late phase. Early phase involves healing the injured sarcolemma and restricting the spread of damage to the injured myofiber. Late phase of healing occurs a few days postinjury and involves interaction of injured myofibers with regenerative and inflammatory cells. Of the two phases, cellular and molecular processes involved in the early phase of healing are poorly understood. We have implemented an improved sarcolemmal proteomics approach together with in vivo labeling of proteins with modified amino acids in mice to study acute changes in the sarcolemmal proteome in early phase of myofiber injury. We find that a notable early phase response to muscle injury is an increased association of mitochondria with the injured sarcolemma. Real-time imaging of live myofibers during injury demonstrated that the increased association of mitochondria with the injured sarcolemma involves translocation of mitochondria to the site of injury, a response that is lacking in cultured myoblasts. Inhibiting mitochondrial function at the time of injury inhibited healing of the injured myofibers. This identifies a novel role of mitochondria in the early phase of healing injured myofibers.

Introduction

Skeletal muscles routinely undergo mechanical injury followed by full healing. The healing often further enhances the muscle function. In the early phase of healing, the injured sarcolemma is repaired, and the injury to the myofiber is contained by the formation of a stump that prevents the rest of the myofiber from becoming necrotic (1–3). This is followed by a late phase of healing where the stump and necrotic tissue are cleared by inflammatory cells, the myogenic cells are activated to fuse with the myofibers, and the damaged muscle is regenerated (4, 5). In the early phase, trafficking of proteins and lipids to the injured sarcolemma augments healing of the injured myofiber. In the late phase, trafficking across sarcolemma helps in cell-cell and cell-matrix signaling (1, 6–8). Thus, monitoring dynamic changes in the sarcolemmal proteome would improve our understanding of how these two phases are regulated and help to better understand various neuromuscular disorders associated with defects in myofiber degeneration and regeneration (6, 9). Such changes have been studied during the late phase of healing; however, little is known about such changes during the early phase of myofiber healing (2, 3, 7, 8).

There are several studies that have analyzed the whole proteome of the muscle tissue and cultured muscle cells (10–16). A few studies have also analyzed the membrane proteins present in the sarcolemma (17–21). These latter studies did not capture the proteome associated with the inner or outer leaflet of the sarcolemmal proteome, which is key for sarcolemmal function and is the target of mutations leading to many muscular dystrophies (6). Commonly used methods for isolation of cell membrane proteome are based on subcellular fractionation and result in preparations containing abundant cytosolic proteins (18, 22–24). At least three different affinity-based enrichment strategies have been developed to increase the purity and yield of cell membrane proteome (22). One approach uses biotin to selectively tag cell surface proteins followed by the use of streptavidin beads to pull down the tagged proteins (25, 26). Another approach relies on the assumption that the majority of membrane proteins are glycosylated, and lectin (27) or hydrazide chemistry (28) is used to tag these proteins. Yet another approach has exploited the electrostatic interaction between cationic colloidal silica and anionic membrane lipids on the cell surface to increase the stability and density of the plasma membrane and, subsequently, to separate it using centrifugation (29). These approaches for isolating sarcolemmal proteome from muscles rely on the use of a large amount of tissue (17, 19, 20, 20, 21). Thus, they are not well suited for studying the effects of focal muscle injuries or studying smaller muscles. In addition to approaches to enrich cell membrane proteins, the use of proteome-wide monitoring of small changes in the level of sarcolemmal proteins requires increased sensitivity in detecting these changes. Mass spectrometry (MS) is a technique well suited for large scale monitoring of changes in protein levels, and isotopic labeling of proteins has emerged as an efficient approach for MS-based detection of small changes in protein levels (30). Isotopic labeling has been carried out using different techniques, including iTRAQ (isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation), ICAT (isotope-coded affinity tags), and stable isotope labeling of amino acids in culture (SILAC)3 (30, 31). The SILAC approach has also been extended to detect differential protein expression in animal tissues by feeding animals for multiple generations a diet containing amino acids that have a stable isotope of carbon, 13C6 (30, 32, 33).

In the present study, we have combined features of the existing proteomic approaches to develop a unified method for improved recovery of sarcolemmal proteins from mononucleate and multinucleate myocytes. This involves biotin tagging of sarcolemmal proteins followed by affinity-based enrichment of sarcolemmal fragments containing biotinylated and other proteins tightly associated with the sarcolemma. Using this rapid two-step procedure, we isolated the sarcolemma and associated proteome from muscle cells in culture (C2C12 and immortalized mouse primary myoblasts) and from myofibers isolated from mouse muscle tissue. This approach provided improved sensitivity of detection of sarcolemmal proteins, even from small muscle samples. We applied this approach in combination with stable isotope labeling of proteins in mice and studied changes in the sarcolemmal proteome during the early phase of myofiber injury. We found an increased association of active mitochondria with the injured sarcolemma within seconds of myofiber injury. This response involved accumulation of mitochondria at the site of myofiber injury but is lacking in cultured muscle cells. This identified an unrecognized response of mitochondria to muscle injury and demonstrates the utility of our proteomic approach for studying even small and acute changes in sarcolemmal proteome.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

C2C12 myoblast cell line was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with Glutamax, high glucose, 110 mg/liter sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and with 100 μg/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). H2K myoblasts were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), 2% chicken embryo extract (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY), and 100 μg/ml each of penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen). Prior to culturing H2K cells, 10 μg of γ-interferon (Roche Applied Science) was added to 500 ml of the constituted media, and culture dishes were coated with 0.1% gelatin at room temperature for 30 min.

Animal Husbandry, Generation of Stable Isotope Labeling in Mammals (SILAM) Mouse, and Myofiber Isolation

Methods involving animals were approved by the local Institutional Animal Research Committee, and animals were maintained in a facility accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Lysine (13C6)-labeled C57BL6 mice were developed by feeding a custom diet containing “heavy” (13C6) lysine at 1% level that adheres to the regular laboratory mouse nutritional standards (mouse feed pellets l-lysine (13C6, 99%); Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA). Briefly, C57BL6 breeding pairs were obtained and housed in an individually vented cage system under a controlled 12-h light/dark cycle with free access to feed and water. The pregnant mother was fed with a customized heavy lysine diet until the litter (F1 generation) was weaned. After weaning, the pups were continued on a heavy lysine diet and bred to obtain the next litter (F2 generation). Incorporation of (13C6) lysine in tissue proteins was monitored using mass spectrometry in the mother and in each generation. Results demonstrated an improvement in labeling efficiency in the tissues in each generation upon continuous feeding with the heavy lysine diet. By F2 generation, the incorporation efficiency of heavy lysine was 98–100% average labeling efficacy of all uniquely identified proteins for the different tissues tested, including skeletal muscle, brain, and liver. The labeling efficacy for skeletal muscles was 98.26 ± 3.5% (supplemental Fig. 1). Incorporation efficiencies we obtained are similar to those described earlier (34). Prior to harvesting the muscle tissue, mice were perfused with PBS and then euthanized with carbon dioxide asphyxiation. The desired muscles (EDL, soleus, and tibialis anterior) were carefully dissected while handling the tissue by tendons only and avoiding stretching or touching the muscle fibers. Muscle tissues were removed immediately, weighed, and processed for subcellular fractionation and sarcolemmal protein extraction as described below. For myofiber isolation, a sterile solution of collagenase type 1 (2 mg/ml in DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared immediately before tissue extraction. The extracted muscles were placed into individual vials of collagenase and incubated in a 35 °C shaking water bath for 1–2 h depending on the size of the muscle. The fibers were then liberated by gentle trituration with a fire-polished wide-mouthed Pasteur pipette that had been rinsed in DMEM containing 10% horse serum. The medium was removed carefully, and the fibers were washed three times with DMEM. The fibers were then used for biotinylation and membrane sheet preparation as described below. For injury, the biotinylated myofibers were passed through a narrow-mouthed Pasteur pipette, resulting in <10% hypercontracted fibers.

Cell Surface Biotinylation

C2C12, H2K myoblasts, or muscle fibers were washed three times with cold Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS; Sigma-Aldrich) and treated with 0.5 mg/ml EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) made in cold HBSS (pH 7.4). The cells or fibers were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C, followed by a single wash with cold HBSS and then incubated with cold 0.1 m Tris-HCl solution, pH 7.4, at 4 °C for 10–15 min to quench unreacted biotin.

Isolation of Sarcolemmal Proteome by Detergent-based Solubilization

Cell surface proteins of C2C12 cells grown in one cell culture dish (15-cm diameter) were biotinylated using EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in HBSS. Biotinylated cells were lysed at room temperature with 1 ml of cold RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing protease inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell lysates were harvested using a cell scraper and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube, and the total amount of protein was estimated using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Up to 800 μg of protein was incubated for 1 h with 200 μl of Dynabeads MyOneTM Streptavidin C1 magnetic beads (Invitrogen) pre-equilibrated with RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich). The beads were collected using the Dynamag-2 magnet (Invitrogen). To remove weakly/nonspecifically bound cytosolic proteins, the beads were washed once with cold RIPA buffer, followed by high salt and high pH washes. For the high salt wash, buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 150 mm NaCl was used for 10 min. For high pH, two washes (5 and 30 min each) with cold 100 mm sodium carbonate solution, pH 11.5, were given. All salts were subsequently removed by two washes with water. All washes were done at 4 °C in the presence of protease inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Isolation of Sarcolemmal Proteome by Cell Rupture and Membrane Sheet Preparation

C2C12 myoblasts were grown in one or two cell culture dishes (15-cm diameter), and H2K myoblasts were grown in three 15-cm dishes. Subsequently, cultured cells or muscle fibers were treated with biotin as described above. Biotinylated cells or fibers were washed once with cold HBSS. Subsequently, 2 ml of ice-cold HBSS containing protease inhibitors was added to each 15-cm dish, and the cells were collected using a cell scraper. The cell suspension was homogenized with 50 strokes in a tight fitting 2-ml Dounce homogenizer using pestle B (Corning Inc.). Lysis was confirmed microscopically, and the homogenate was centrifuged at low speed (800 × g, 10 min, 4 °C) to remove intact nuclei. The postnuclear supernatant was removed, and the protein concentration was estimated using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). The postnuclear supernatant was then bound to pre-equilibrated streptavidin beads and processed as above, except that the streptavidin beads were not given the first wash with RIPA buffer.

Sample Preparation, In-gel Digestion, and Peptide Extraction

The streptavidin beads containing bound biotinylated plasma membrane proteins were rinsed twice with cold water and resuspended in 2× SDS sample buffer containing 2.5% β-mercaptoethanol. The sample was heated at 50 °C for 30 min to elute the proteins bound to the beads, followed by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE using a precast 4–12% gel (BisTris Novex minigel, Invitrogen). The gel was fixed with methanol/water/acetic acid (45:50:5, v/v/v) for 30 min, and subsequently bands were visualized by staining with Bio-Safe Coomassie Blue (Bio-Rad). The fractionated gel lane was excised into 35 bands. Each slice was destained with 50% acetonitrile (v/v) and 100 mm NH4HCO3, dehydrated with 100% acetonitrile. Gel pieces were rehydrated in 10–20 μl of cold digestion buffer (12.5 ng/μl of sequencing grade trypsin (Promega) in 50 mm NH4HCO3) and incubated at 4 °C for 45 min. The excess buffer was removed and replaced with 5 μl of 50 mm NH4HCO3. Digestion with trypsin was carried out overnight at 37 °C. Tryptic peptides were extracted with 50% acetonitrile with 5% formic acid, repeated twice. Pooled peptides were dried by vacuum centrifugation and resuspended in 10 μl of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid.

LC-MS/MS

All analyses were carried out on a hybrid Thermo LTQ-Orbitrap-XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled online to a nano-LC system (Eksigent, Dublin CA). The concentrated peptides from each band were injected via an autosampler (6 μl) and loaded onto a Symmetry C18 trap column (5 μm, 300-μm inner diameter × 23 mm, Waters) for 10 min at a flow rate of 10 μl of 0.1% formic acid/min. The sample was subsequently separated by a C18 reverse-phase column (3.5 μm, 75 μm × 15 cm, Dionex) at a flow rate of 250 nl/min. The mobile phases consisted of water with 0.1% formic acid (A) and 90% acetonitrile (B). A 65-min linear gradient from 5 to 60% B was employed. Eluted peptides were introduced into the mass spectrometer via a 20-μm inner diameter, 10-μm silica tip (New Objective Inc., Woburn, MA) adapted to a nanoelectrospray source (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The spray voltage was set at 1.4 kV, and the heated capillary was set at 200 °C. The LTQ-Orbitrap-XL mass spectrometer was operated in data-dependent mode with dynamic exclusion in which one cycle of experiments consisted of a full MS in the Orbitrap (300–2000 m/z) survey scan (profile mode for SILAM and centroid for label-free), 30,000 resolution, and five subsequent MS/MS scans in the LTQ of the most intense peaks in centroid mode using collision-induced dissociation with the collision gas (helium) and normalized collision energy value set at 35%.

Database Search and Analysis

Proteins were identified from raw MS and MS/MS data using the Sequest algorithm in Bioworks Browser version 3.3.1 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) against the Uniprot mouse database (UniProt release-2010_11, 16,333 entries) indexed for fully tryptic, 300–4000 mass range, and two missed cleavages. Mass tolerance was set at 50-ppm error for MS and 1-Da error for MS/MS and potential modification of oxidized methionine (15.99492 Da). Protein identifications were filtered as follows: ΔCN > 0.1; XCorr > 1.9, 2.2, 2.5, and 3.5 for z = 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively; two distinct peptides; and peptide probability of <1 × 10−3. For protein identification and quantification of SILAM samples, we used Integrated Proteomics Pipeline (IP2) version 1.01 software developed by Integrated Proteomics Applications, Inc. (San Diego, CA) Mass spectral data were converted to MS1 and MS2 files using RawExtract version 1.9.1.1 and uploaded into IP2 software. Files from each lane were searched against the forward and reverse Uniprot mouse database (UniProt release-2010_11, 16,333 entries) for tryptic peptides allowing one missed cleavage and possible modification of oxidized methionine (15.99492 Da) and heavy lysine (6.0204 Da). IP2 uses the Sequest 2010 (06_10_13_1836) search engine. Mass tolerance was set at ±30 ppm for MS and ±1.5 Da for MS/MS. Data were filtered based on a global 3% false discovery rate and at least one peptide per protein at a 0.1% false discovery rate. All of the bands from each lane were summed in the analysis. Census software version 1.77, built into the IP2 platform, was used to determine the ratios of unlabeled and labeled peptide pairs using an extracted chromatogram approach. The distribution of ratios was corrected for error in sample mixing. Data were checked for validity by using regression correlation better than 0.98 for each peptide pair. A one-sample t test was performed to identify proteins that were significantly (p < 0.05) different from a value of 1 (no change); these were retained for further analysis.

Bioinformatics Analysis

The molecular mass values and percentage of the protein covered by the matched peptides were retrieved from Bioworks output files. The subcellular location of each identified protein was determined using the Gene Ontology (GO) and keyword information available from the UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProt release 2011_08-Jul 27, 2011). The list was subsequently curated based on a review of the published literature to assign unique localization for each protein.

Live Imaging of Myofiber and Myotube Injury

For imaging mitochondrial dynamics and healing of injured myofibers, live myoblasts/myotubes or myofibers isolated from EDL and soleus muscles as described above were used. The fibers were plated on Matrigel-coated dishes in H2K myoblast cell culture medium (described above) and maintained for 1–2 days in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2. For imaging mitochondria, live fibers/cells were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C in 100 nm MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos (Invitrogen). The excess dye was washed off, and the fibers were transferred to cell imaging medium (HBSS with 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) and imaged on an inverted Olympus IX81 microscope (Olympus America) custom equipped with a CSUX1 spinning disc confocal unit (Yokogawa Electric Corp., Tokyo, Japan), pulsed laser Ablate!TM (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc., Denver, CO), and diode laser of 561 nm (Cobolt, Stockholm, Sweden). Images were acquired using Evolve 512 EMCCD (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) at 1 Hz. Image acquisition and laser injury were controlled using Slidebook 5.0 (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc., Denver, CO).

RESULTS

Isolation of Sarcolemmal Proteome Using the Membrane Solubilization Approach

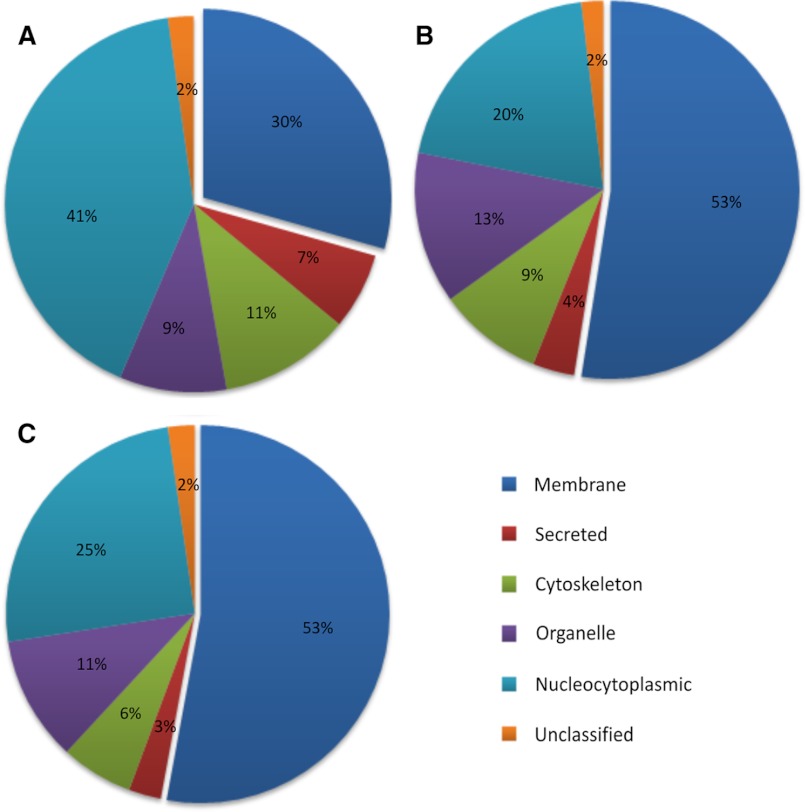

Use of biotin tagging of cell surface proteins together with streptavidin beads has been used to pull down cell surface proteins from cells and tissue (25, 26). Thus, we used this approach to enrich plasma membrane proteins from cultured myoblasts. Cell surface proteins were biotinylated using Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (biotin) and solubilized using RIPA buffer (35, 36), and the biotinylated proteins were isolated using streptavidin-conjugated agarose or magnetic beads, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Magnetic beads allowed greater recovery of proteins as compared with agarose beads (data not shown) and were used for all subsequent experiments. To improve recovery of hydrophobic proteins and peptides, isolated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, the gel lane was cut into 30–35 bands, and proteins trapped in their denatured state in the gel pieces were digested with trypsin followed by LC-MS/MS analysis (Fig. 1). With these optimizations, we were able to identify a total of 544 unique proteins in two combined biological replicate preparations (supplemental Table S1). Based on GO annotations and published literature, we determined that membrane proteins represented less than one-third (29%) of these proteins, whereas cytosolic proteins represented 41% of the total proteins (Fig. 2A).

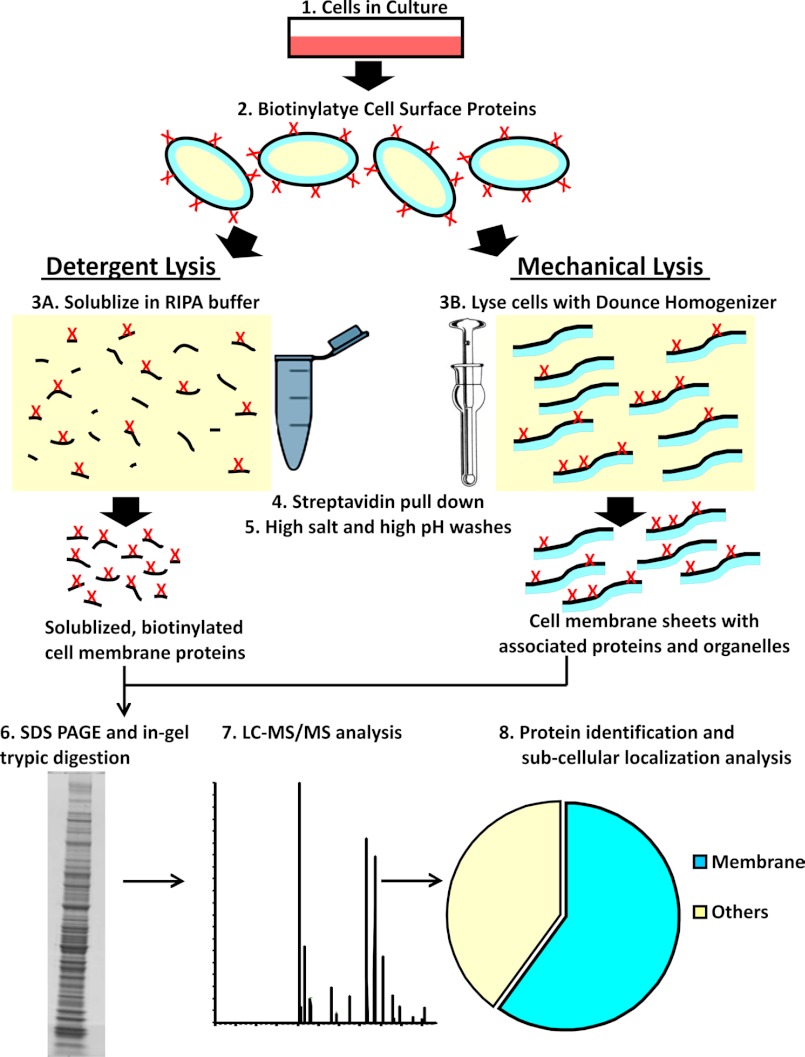

FIGURE 1.

Schematic illustration of detergent and mechanical lysis approaches used to isolate sarcolemmal proteome. Cultured muscle cells were biotinylated, and the cell surface proteins were extracted either by lysing cells with detergent or by mechanical homogenization. Biotinylated cell surface proteins were then purified by binding with magnetic streptavidin beads and sequentially washing with a high salt (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, and 150 mm NaCl) and high pH buffer (100 mm sodium carbonate, pH 11.5) to remove nonspecifically bound proteins. Detergent lysis allowed isolation of only the biotinylated proteins, whereas mechanical lysis resulted in membrane sheets containing biotinylated and non-biotinylated proteins embedded in or tightly associated with the membrane sheet. The isolated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by LC-MS/MS after in-gel digestion with trypsin.

FIGURE 2.

Pie charts showing the subcellular localization of proteins. Shown are proteins identified in the cell surface proteome of C2C12 myoblasts processed using the detergent solubilization approach (A) and from C2C12 (B) and H2K (C) myoblasts using the mechanical lysis approach. Each protein was designated only one subcellular location, and the number of proteins in each compartment has been represented as a percentage of total proteins identified. The subcellular location of the identified proteins was determined by the Gene Ontology database (see the Uniprot Web site) as well as literature search. Data used to construct these pie charts are presented in supplemental Tables S1–S4, which also detail the information on all of the proteins identified in two independent biological replicates, including the percentage of coverage and number of peptide hits.

Isolation of Sarcolemmal Proteome Using the Membrane Sheet Approach

One possible reason for low enrichment of membrane proteins could be that in many membrane proteins, primary amines are either not present or not exposed at the extracellular face of the cell, making these proteins impervious to labeling and pull-down using biotin and streptavidin. Thus, to further enrich the sarcolemmal proteome, we utilized a double enrichment approach. Following labeling of the cells with biotin, instead of solubilizing with detergent, the cell membrane was mechanically ruptured using a Dounce homogenizer. The resulting cell membrane fragments contained not only the biotinylated proteins but also other proteins that are embedded in or tightly associated with the plasma membrane sheet and are inaccessible to labeling by biotin (Fig. 1). As depicted in Fig. 1, this approach will also enrich organelle proteins that are associated with the sarcolemma such that high salt and high pH buffer wash does not dissociate them from the sarcolemmal membrane sheets. In general, this approach is similar to affinity-based enrichment techniques used for the isolation of plasma membrane proteins from non-muscle cells (37–39). The plasma membrane sheets can then be separated from other membranes by using streptavidin beads that will bind the biotinylated proteins present only in the plasma membrane sheets. Any non-specifically attached proteins can be washed off of these sheets by sequentially washing with high salt and high pH buffers as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Isolated proteins were resolved and analyzed by LC-MS/MS as described above. We analyzed two biological replicates and identified 579 unique proteins. Based on GO annotation and published literature, the proportion of membrane proteins obtained using the “membrane sheet” approach increased to 53%. Furthermore, the proportion of nucleo-cytoplasmic proteins decreased by 2-fold compared with the detergent solubilization approach at 20% (Fig. 2B and supplemental Table S2). We evaluated the reproducibility of this approach by four independent experiments, each of which resulted in a similar percentage of proteins belonging to different subcellular locations (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of sarcolemma-associated proteins identified from C2C12 cells using the mechanical lysis approach in four independent biological replicates (experiments E1–E4)

Subcellular localization of identified proteins was determined according to a Uniprot Gene Ontology database and literature search. Each protein was designated with only one subcellular location, and the number of proteins in each compartment has been represented as the percentage of total proteins identified.

| E-1 | E-2 | E-3 | E-4 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | |

| Membrane | 46 | 46 | 47 | 51 | 47 ± 2 |

| Secreted | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 ± 1 |

| Cytoskeleton | 10 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 10 ± 1 |

| Nucleocytoplasmic | 30 | 25 | 27 | 26 | 27 ± 2 |

| Organelle | 10 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 10 ± 2 |

| Unclassified | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 ± 0 |

Although C2C12 cells represent a useful myogenic cell line, in view of the tumorigenic nature of these cells, we tested this approach on mouse primary myoblast cell line (H2K) (40). We identified a total of 964 unique proteins in two independent experiments (supplemental Table S3). Of these, 53% of the proteins were membrane proteins, and the rest exhibited a similar distribution across the various subcellular locations as observed in the C2C12 cells (Fig. 2C).

Isolation of the Cell Surface Proteome of Myofibers

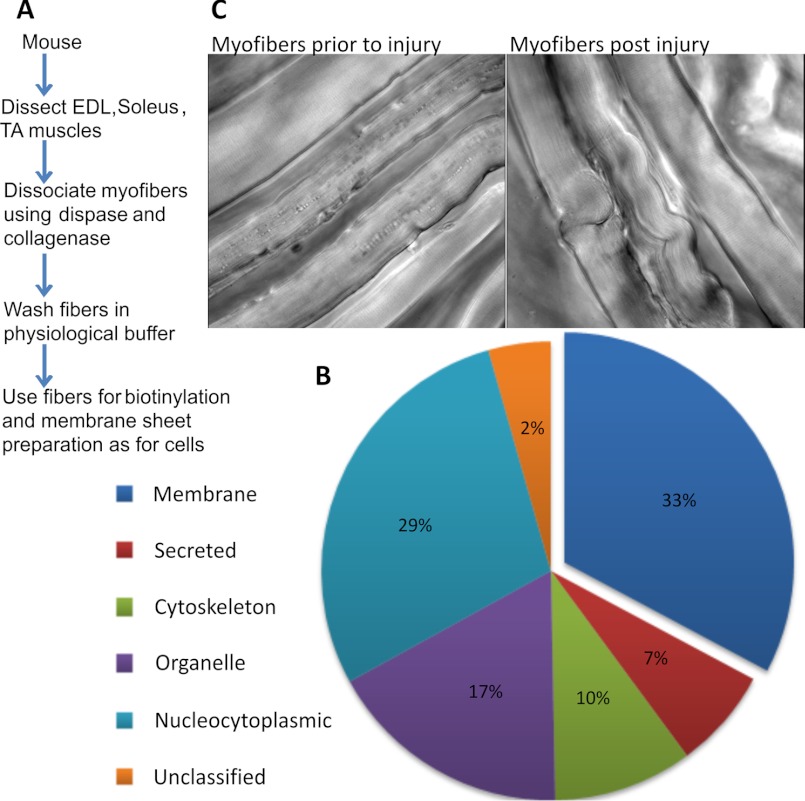

Earlier studies have used density gradient centrifugation to isolate sarcolemma from muscle (18, 22, 23). This requires a large amount of muscle tissue and therefore is not suited for isolating sarcolemmal proteins from smaller muscles or where changes are limited to a part of the muscle tissue. Also, with existing approaches, caution needs to be exercised when interpreting proteomic findings using total tissue extracts because homogenized muscle tissue contains proteins from other sources like endothelial and blood cells. We tested the utility of our approach in addressing the limitations of the existing approaches for isolating sarcolemmal proteome from muscle fibers. To reduce the contribution of proteins from non-muscle cells, we dissociated myofibers instead of using whole muscle lysates (Fig. 3A). From two experiments where the EDL and soleus myofibers were used together, the myofiber sarcolemmal proteome isolated using the membrane sheet enrichment approach provided 451 unique proteins (supplemental Table S4). Of these, subcellular locations were ascribed for 431 proteins, and 33% of these proteins are membrane proteins (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained using the tibialis anterior muscle (data not shown). The sarcolemma-associated proteins isolated included integral and peripheral sarcolemmal proteins implicated in healing of injured cells and myofibers: dysferlin, annexin A1, TRIM 72, and PTRF (1, 41–44) (supplemental Table S4). In addition to identifying standard integral plasma membrane proteins like CD147 and Na,K-ATPase, many other proteins were identified using our approach, including dystrophin and its associated glycoproteins, which have not been identified in many of the earlier mass spectrometric analyses of the total muscle proteome due to their low abundance and large molecular weight. Therefore, the membrane sheet approach offers the sensitivity for generating a comprehensive data set for even low abundance proteins present in the sarcolemma.

FIGURE 3.

Sarcolemmal proteomics of healthy and injured myofibers. A, experimental work flow for isolation of the sarcolemmal proteome from isolated muscle fibers. B, pie chart showing the subcellular localization of all proteins identified, which was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Supplemental Table S4 provides the complete list of proteins identified and used in making the pie chart. C, transmitted light images showing a portion of the EDL muscle that has been mildly disaggregated and left uninjured or mechanically injured as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

Quantitative Analysis of the Cell Surface Proteome of Myofibers in Response to Injury

To identify changes in the myofiber sarcolemmal proteome during 10 min of repair following acute injury, we used muscle tissue from metabolically l-lysine (13C6)-labeled mice, termed SILAM (33) or SILAC mice (32), coupled to LC-MS/MS for protein identification and quantification. The cell surface of the isolated fibers from heavy lysine-labeled and unlabeled mice were biotinylated as described before, except this time we used the intact myofibers obtained from EDL and soleus muscles of mice fed with normal (12C6) l-lysine and heavy (13C6) l-lysine. Fibers from the heavy or light lysine-labeled mice were injured by passage through a narrow bore pipette. In independent experiments, we tested the extent of injury and the healing ability of EDL and soleus muscle fibers following mechanical injury by the ability of the fibers to exclude FM1-43 dye, whose fluorescence increases significantly upon entering injured myofiber and binding the intracellular membrane (supplemental Fig. 2) (1). Fibers that heal will manage to exclude this dye. We found that this approach of myofiber injury resulted in injury of >50% of fibers, and >77% of the injured fibers healed within the 10 min at 37 °C. Fig. 3C shows the morphology of the myofibers prior to and immediately following the injury of EDL muscle.

For proteomic analysis, the injury-triggered alteration in the cell surface level of proteins was quantified in four independent muscle pairs; in two pairs, SILAC-labeled muscles were injured, whereas unlabeled muscles were not injured, and in the other two, unlabeled muscles were injured and SILAC-labeled muscles were not injured. Injured fibers were allowed to heal for 10 min in the presence of 2 mm calcium. At this point, all myofibers from the heavy lysine-labeled and unlabeled muscle were pooled together and processed as before to isolate the cell surface proteome. Using this approach, we were able to identify and quantitate 493 protein pairs.

For all peptides detected in any experiment, the ratio of labeled and unlabeled peptide pairs was determined from the extracted ion chromatogram for heavy and light peptide with a regression correlation of >98%. In each experiment, the ratio of labeled to unlabeled protein and the S.D. value of this ratio were calculated by averaging ratios for the individual peptides corresponding to that protein. This value was also used to carry out one sample t test for each experiment, which identified 320 protein pairs that were significantly (p value <0.05) different from a value of 1 (no change). By curating this list further for proteins that were detected in at least three of the four muscle pairs analyzed, we identified 110 proteins with altered protein expression. The -fold change (ratio of injured versus uninjured) obtained from these independent experiments was used to rank the proteins. Table 2 lists 25 proteins whose sarcolemmal abundance increased the most in response to myofiber injury. The subcellular localization for each of these proteins was determined based on gene ontology annotation.

TABLE 2.

Proteins whose abundance at the sarcolemma increased in injured muscles

Injury-triggered alteration in the level of cell surface proteins was quantified in four biological replicates (experiments E1–E4). In each experiment, -fold change for individual protein and the S.D. value were calculated by averaging the ratio of labeled and unlabeled peptide pairs detected for that protein. Each labeled and unlabeled peptide ratio was determined from the extracted ion chromatogram for heavy and light peptide with a regression correlation of >98%. We used one sample t test for each experiment to identify proteins that were significantly (p < 0.05) different from a value of 1 (no change). Of these proteins, the top 25 that are present in at least three of the four replicate experiments are shown here. The average -fold change obtained from these independent experiments was used to rank the proteins. The subcellular localization for each protein, based on gene ontology annotation, shows an abundance of mitochondrial proteins.

| Accession | Description | Change (injured/uninjured) |

Subcellular location | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-1 | E-2 | E-3 | E-4 | Average | |||

| -fold | |||||||

| P05202 | Aspartate aminotransferase | 1.77 | 1.32 | 1.99 | 1.69 | Mitochondrion matrix | |

| P08249 | Malate dehydrogenase | 1.61 | 1.31 | 2.48 | 1.02 | 1.60 | Mitochondrion matrix |

| P51174 | Long chain-specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 1.79 | 1.52 | 1.86 | 1.04 | 1.55 | Mitochondrion matrix |

| P97807 | Fumarate hydratase | 1.39 | 1.92 | 1.08 | 1.46 | Mitochondrion | |

| P54071 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP) | 2.12 | 0.80 | 1.57 | 1.31 | 1.45 | Mitochondrion |

| P42125 | 3,2-trans-Enoyl-CoA isomerase | 1.62 | 1.18 | 1.94 | 0.93 | 1.42 | Mitochondrion matrix |

| Q8BH95 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | 1.43 | 1.43 | 1.33 | 1.40 | Mitochondrion matrix | |

| Q99KI0 | Aconitate hydratase | 1.49 | 1.33 | 1.57 | 1.08 | 1.37 | Mitochondrion |

| Q91WD5 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) iron-sulfur protein 2 | 1.18 | 1.52 | 1.37 | 1.36 | Mitochondrion inner membrane | |

| Q60597 | 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 component | 1.12 | 1.40 | 1.51 | 1.34 | Mitochondrion matrix | |

| O08749 | Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase | 1.29 | 1.30 | 1.59 | 1.07 | 1.31 | Mitochondrion matrix |

| P47934 | Carnitine O-acetyltransferase | 1.47 | 1.40 | 1.27 | 1.08 | 1.31 | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| Q9D6R2 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase (NAD) subunit α | 1.47 | 1.33 | 1.09 | 1.30 | Mitochondrion | |

| Q9CZU6 | Citrate synthase | 1.38 | 1.33 | 1.40 | 1.06 | 1.29 | Mitochondrion matrix |

| Q8QZT1 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase | 1.67 | 1.09 | 1.33 | 1.07 | 1.29 | Mitochondrion |

| P31001 | Desmin | 1.76 | 0.93 | 1.06 | 1.25 | Cytoplasm | |

| Q91VD9 | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75-kDa subunit | 1.20 | 1.59 | 0.95 | 1.24 | Mitochondrion inner membrane | |

| P82348 | γ-Sarcoglycan | 1.99 | 0.61 | 1.09 | 1.23 | Cell membrane | |

| Q91YT0 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein 1 | 1.17 | 1.50 | 0.98 | 1.21 | Mitochondrion inner membrane | |

| Q8BKZ9 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase protein X component | 1.05 | 1.22 | 1.37 | 1.21 | Mitochondrion matrix | |

| Q91Z83 | Myosin-7 | 1.39 | 0.64 | 1.59 | 1.16 | 1.20 | Cytoplasm (myofibril) |

| P47738 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | 1.05 | 1.08 | 1.29 | 1.33 | 1.19 | Mitochondrion matrix |

| Q9CZ13 | Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 1 | 1.17 | 1.45 | 0.91 | 1.18 | Mitochondrion inner membrane | |

| Q9D0M3 | Cytochrome c1, heme protein | 1.23 | 1.45 | 0.81 | 1.16 | Mitochondrion inner membrane | |

| Q99LC3 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 α subcomplex subunit 10 | 1.11 | 1.46 | 0.91 | 1.16 | Mitochondrion matrix | |

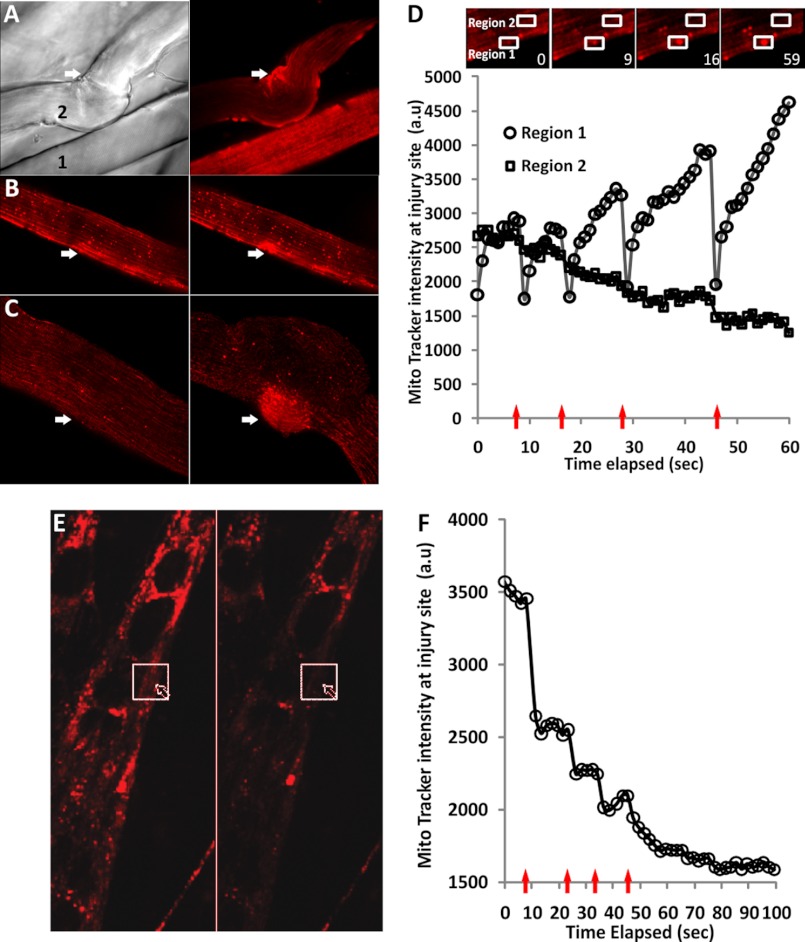

In agreement with previous reports regarding TRIM72/MG53 accumulation at the site of myofiber injury (42), we did find in two experiments an increase in the level of this protein at the injured sarcolemma; however, this result did not pass our statistical filtering criteria described above. The level of the protein PTRF, which anchors MG53 (43), was found to be decreased at the injured sarcolemma in the only experiment it was detected in. Interestingly, most (21 of 25) proteins that showed the greatest increase following injury are mitochondrial proteins, including the mitochondrial matrix proteins (Table 2). The presence of matrix proteins indicated that the increase may be due to accumulation and tighter association (not fusion) of the mitochondria to the sarcolemma. Previously, electron microscopic analysis of muscles several hours after cold or chemical injury showed an increased number of mitochondria at the site of injury (3). This increase could occur due to accumulation of the existing mitochondria at the site of the injury or due to new mitochondria synthesis at the site of the injury. Our proteomics data showed that the increased number of mitochondrial proteins in the sarcolemmal preparation could be detected within minutes of injury, which is too soon for new mitochondrial synthesis and argues against mitochondrial biosynthesis as the basis for this increased accumulation. To test if myofiber injury caused mitochondria to rapidly move to and accumulate at the site of injury, we processed the EDL tissue as described for cell surface biotinylation, with the modification that instead of biotin the tissues were incubated for 10 min with the MitoTracker dye, and the fibers were then imaged live at 37 °C in injured or uninjured myofibers. Uninjured myofibers exhibited striated distribution throughout the length of the myofiber (fiber 1 in Fig. 4A). However, in injured fibers (fiber 2 in Fig. 4A), the mitochondrial labeling was increased at the site of injury (judged by the point of fiber contraction). Because this approach is not feasible for real-time visualization of mitochondrial dynamics during the course of myofiber injury, we attempted to visualize mitochondrial dynamics by laser-induced injury of individual myofibers. Using FM1-43 dye, we first established the ability to injure myofibers isolated from EDL and soleus muscles such that they can successfully heal from injury (supplemental Fig. 2). Next, using this same approach, we monitored the response of mitochondria to laser-induced myofiber injury. For this, we labeled myofibers, as above, with MitoTracker dye. The fibers were washed free of the dye and imaged in real time prior to injury and as they were injured using a pulsed laser. In 70% of the injured myofibers, mitochondria were found to accumulate at the site of the injury in a manner directly dependent on the extent of the injury; minor injury causes lower and major injury causes higher accumulation of mitochondria (Fig. 4, B and C and supplemental Movie 1). Accumulation of mitochondria at the site of the injury occurred within seconds of the injury, and repeated injury at the same site resulted in cumulative increase of mitochondria at the site of the injury with each injury (Fig. 4D, Region 1). At the site proximal to the site of injury, there was continuous decrease in mitochondrial staining during the course of imaging (Fig. 4D, Region 2). These observations indicate that the myofiber injury-induced increase in mitochondrial proteins at the sarcolemma is due to rapid (within seconds) accumulation of mitochondria to the injured sarcolemma from regions proximal to the site of the injury. The MitoTracker dye used in these experiments would diffuse out of the mitochondria if the mitochondria were to lose integrity, causing a loss in dye signal. The finding that the increase in dye signal we detect is sustained (Fig. 4D and supplemental Movie 1) suggests that the mitochondria accumulating at the sites of injury are not losing their function. These observations suggest that the mitochondria translocate to the site of myofiber injury and become tightly associated with the injured sarcolemma, resulting in an increase in mitochondrial protein as identified in our proteomics experiments.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of myofiber injury on mitochondrial distribution. A, MitoTracker Red (CM-H2XRos)-labeled EDL muscle was loosely dissociated with collagenase and mechanically injured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Shown are the transmitted light image (left) and MitoTracker staining (right) of uninjured (1) and injured (2) myofibers 10 min following mechanical injury. B, myofibers were labeled with MitoTracker, and the excess dye was washed multiple times. The fibers were then injured using a high intensity pulsed laser, and the images show independent fibers before (left) and 50 s after (right) injury. B, mild injury; C, severe injury; the injury sites are marked by the arrows. D, plot showing MitoTracker intensity at the site of injury (Region 1) and an adjacent region (Region 2) for a fiber that was mildly injured five times (arrows). Due to the use of a high intensity laser for the injury, each injury resulted in quenching of the fluorescence of the mitochondria present at the wound site prior to injury, the recovery of this fluorescence to higher than preinjury value suggesting accumulation of new mitochondria because the MitoTracker used for labeling was removed by multiple washes. The inset shows an enlarged image of the fiber at the start of imaging (0 s) and various time intervals postinjuries. Note the accumulation of the mitochondria at the site of injury (Region 1), whereas a site adjacent to the injury (Region 2) shows decreased mitochondrial fluorescence. E, C2C12 myotubes were labeled with MitoTracker, and following removal of excess dye, the myotube was injured multiple times using a pulsed laser and imaged at 2-s intervals. A myotube before (left) and 100 s after (right) laser injury is shown. The arrow marks the site of injury, and the box marks the region where the MitoTracker intensity was measured. F, plot showing MitoTracker intensity (arbitrary units (a.u.)) at the site of injury. With each of the four injuries (arrows), the myotube healed (indicated by lack of hypercontraction), but the MitoTracker staining intensity decreased irreversibly with each injury. Loss of MitoTracker staining occurred even for mitochondria distal from the site of injury.

In a similar analysis of the effect of cell injury on cytosolic proteins that appear at the cell surface in C2C12 myoblasts, seven proteins were identified, none of which were mitochondrial proteins (45). This observation was confirmed by our similar analysis of cultured C2C12 myoblasts.4 These results suggest that the mitochondrial translocation to the injured sarcolemma may be specific to myofibers. To test this, we labeled the C2C12 myoblasts (data not shown) and myotubes (Fig. 4E) with the MitoTracker dye and carried out localized laser injury on these cells. Following laser injury, mitochondrial translocation to the site of injury was not observed. Instead, mitochondria remained at the same location as before. The only change that was commonly observed was a loss in mitochondrial potential leading to the loss of MitoTracker from the mitochondria in the injured myoblasts. Similar results were also observed even in the case of primary mouse myoblasts (data not shown).

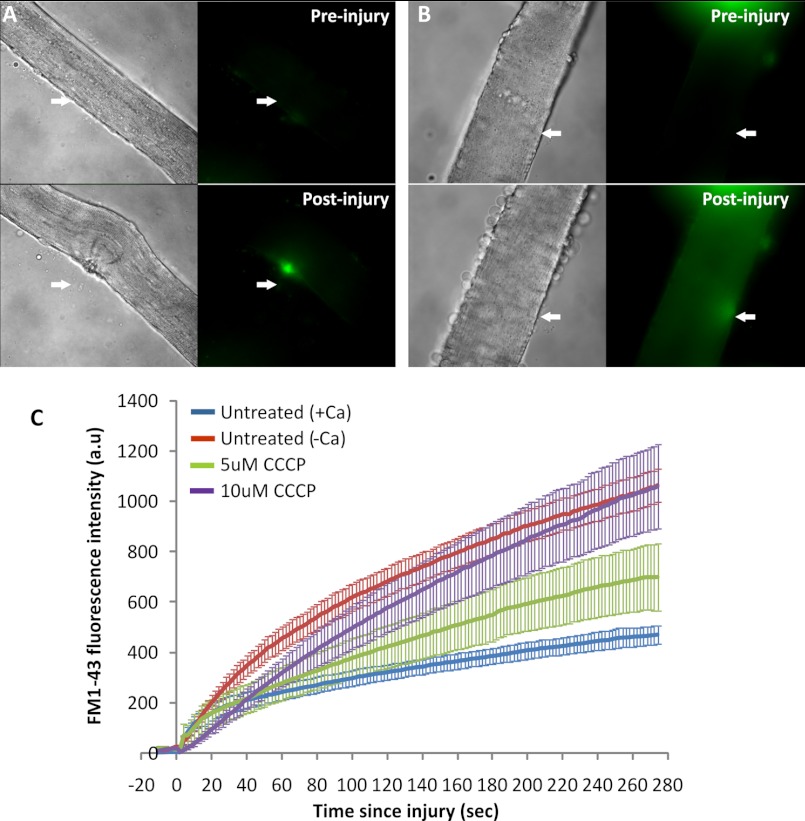

To examine if the accumulation of functional mitochondria is involved in the process of healing the injured myofiber, we reasoned that blocking mitochondrial function should impact the ability of the injured myofibers to heal. For this, we acutely treated the myofibers with varying concentrations of the mitochondrial uncoupler, CCCP. Treatment of myofibers with 5 or 10 μm CCCP for 30 min did not compromise the viability of the myofibers, as judged by the entry of FM1-43 into the myofiber (Fig. 5B, Preinjury); however, if during this period the fibers were injured by a pulsed laser, the healing of the fiber was compromised in a CCCP concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5, B and C). Fibers that were injured similarly but were not treated with CCCP were capable of healing in a calcium-dependent manner (Fig. 5, A and C, and supplemental Fig. 2).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of inhibiting mitochondrial function on myofiber healing. Myofibers isolated from EDL muscle were injured using a high intensity pulsed laser in the presence of 2 μm FM1-43 dye. The myofibers were either not treated (A) or treated with 10 μm CCCP for 30 min prior to injury (B). C, plot showing the kinetics of increase in FM1-43 intensity (arbitrary units (a.u.)) following injury averaged for up to 10 myofibers in each condition. The error bars define the S.E. in the signal at each time point.

DISCUSSION

Several proteomic comparisons of whole skeletal muscle tissue have been reported (10–13). However, the sarcolemmal proteome is poorly characterized because proteomic profiling of the sarcolemma remains challenging due to the low abundance of these proteins as compared with other proteins in muscle. In this study, we have established an improved proteomic approach to study sarcolemmal and associated proteome of cultured muscle cells as well as tissue. Although cultured muscle cells are useful in studying various aspects of skeletal muscle biology, as highlighted by this and other studies, the information obtained from the skeletal muscle tissue, either individual fibers or whole muscle, is physiologically more relevant. Therefore, there is a need to develop approaches that allow study of the sarcolemma from both of these sources, namely cells in culture and myofibers. An earlier report of isolated C2C12 myoblast cell surface proteome, using membrane fractions obtained by centrifugal isolation, identified 213 protein spots on a two-dimensional gel and 653 unique spots in total cell lysate, resulting in membrane protein enrichment of <33% (14). In comparison, our membrane sheet enrichment strategy resulted in the identification of 53% membrane proteins in cell culture and 33% membrane proteins from myofibers. Another such study used oligosaccharide-based labeling of cell surface proteins and identified 128 cell surface N-linked glycoproteins in C2C12 cells (16). Use of our approach in C2C12 cells enabled identification of 168 integral sarcolemmal membrane proteins and 284 sarcolemma-associated proteins. Thus, compared with the existing approaches, our approach for isolating plasma membrane sheets offers improved coverage of the sarcolemmal proteome. Some of the proteins we obtained were classified in the GO database to be localized to subcellular locations other than plasma membrane. This is due to multiple localizations of some proteins (e.g. endoplasmic reticulum-resident proteins GRP78/BiP and protein-disulfide isomerase are also present at the plasma membrane) (46, 47). Similarly, elongation factor-1α, which has a well established role in protein synthesis in the cytoplasm, also has a role in cytoskeletal reorganization (48).

Use of the membrane enrichment strategy to isolate the cell surface proteome of myofibers identified many low abundance sarcolemmal proteins implicated in muscle diseases, including dysferlin, myotilin, dystrophin, and its associated membrane glycoproteins (α-sarcoglycan, γ-sarcoglycan, δ-sarcoglycan, and α-syntrophin). Many of these proteins have not been identified earlier in the mass spectrometric analysis of the total muscle proteome (49). A more recent study reported the use of direct on-membrane digestion of one-dimensional blots of a sarcolemma-enriched fraction isolated from the hind leg muscle homogenate by subcellular fractionation followed by the lectin agglutination technique (19). Mass spectrometric analysis of the proteins obtained after on-membrane digestion identified only 16 proteins, including dysferlin, dystrophin, α-syntrophin, ryanodine receptor, myosin heavy chain, calcium-transporting ATPase, aldolase, and mitochondrial F1-ATPase. Our membrane sheet enrichment protocol reported in this study utilized smaller muscles (EDL and soleus in place of gastrocnemius) and still identified more sarcolemmal membrane proteins (59 proteins) in the muscle fiber preparations. This included not only those proteins identified by Lewis and Ohlendieck (19) but several additional proteins, such as δ-sarcoglycan, γ-sarcoglycan, sarcolemma-associated protein, cadherin, and sodium-potassium ATPase. Moreover, proteins that only had a single peptide hit in this study (19), like α-sarcoglycan and muscle creatine kinase, were also better represented in the proteomic profile obtained in our study because more peptide hits were obtained for each protein (supplemental Table S4). These findings demonstrate the utility of our plasma membrane proteome isolation approach in the analysis of small tissue samples, making it a potentially valuable tool in gaining insights into sarcolemmal proteome changes associated with normal and pathophysiological conditions.

Quantitative proteomics using SILAC provides a useful and powerful strategy to investigate the global changes in the levels of individual proteins in a biological sample. Use of our proteomics approach for monitoring sarcolemma-associated proteins in resting myofibers identified a large number of mitochondrial proteins (>20% of total proteins) that belonged to inner or outer mitochondrial membrane as well as mitochondrial matrix (supplemental Table S4). This suggests that there is a tight association of mitochondria with the sarcolemma. Unlike myofibers, a similar analysis of C2C12 sarcolemmal proteome using this approach showed that <7% mitochondrial proteins are associated with the sarcolemmal proteome.4 Other organelles tightly associated with the myofiber sarcolemma include the endoplasmic reticulum and endosomes.

Using the proteomic approach described here together with in vivo stable isotope labeling of proteins, we quantitatively compared the differences between the myofiber sarcolemma-associated proteome from uninjured versus acutely injured myofibers following 10 min of healing. Although small changes in the level of proteins previously implicated in myofiber repair MG53 and PTRF were detected, the largest and statistically significant increase was observed for mitochondrial proteins. This finding, although unexpected, is not unprecedented because accumulation of mitochondria at the site of myofiber injury has previously been observed by an EM-based analysis of acute muscle injury in vivo (3).

Our results indicated that injury may be causing a rapid and robust sarcolemmal association of mitochondria, which was confirmed by live imaging of injured myofibers. Interestingly, this response of mitochondria is limited to the myofibers and does not occur in myoblasts and myotubes. The latter observation is in agreement with a recent study using C2C12 myoblasts in culture, which reported that seven proteins, including cytoskeleton, endoplasmic reticulum, and nuclear proteins, are exposed on the surface of cultured cells following mechanical injury (45). The selective accumulation of active mitochondria at the site of injury and tight association with the injured myofiber sarcolemmal membrane raises questions regarding the potential functional role of this process. A dose-dependent decrease in the kinetics of healing of the injured myofibers by mitochondrial uncoupler CCCP provides evidence that mitochondrial function is required for the healing of the injured myofibers. Treatment with 10 μm CCCP inhibited the ability of the injured myofibers to heal and also affected the ability of some of the treated myofibers to undergo contracture (Fig. 5B). Therefore, mitochondrial accumulation has a functional role in the healing of the injured myofiber. In the EM study by Papadimitriou et al. (3), it was noted that the injured myofiber heals the site of the injury without the formation of a new sarcolemma. If so, accumulating mitochondria could function as “sandbags” soaking up the flood of extracellular calcium by rapidly sequestering it. Additionally, they could also be providing the barrier function against inflow of other extracellular fluids while the myofibers build the new sarcolemma. Moreover, because repair of injured cell requires a variety of energy-dependent processes (50, 51), the presence of a rich supply of active mitochondria would also meet the local energy demand for healing of the injured sarcolemma. Mitochondria have been reported to associate with sarcolemma during myogenesis, where it provides OXPHOS proteins to the sarcolemma (52). In view of the functional role of mitochondria in myofiber repair, it is plausible that mitochondrial myopathies and other diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction could have an associated myofiber repair deficit. Indeed, subsarcolemmal accumulation of mitochondria is a distinguishing feature of mitochondrial myopathy, and these patients suffer from poor tolerance to exercise (53). Antioxidants, which are useful in the treatment of mitochondrial myopathy (53), have recently been reported to aid in the healing of injured myofibers (54). Although further studies are needed to identify the mechanism and role(s) of mitochondria at the site of sarcolemma injury and the relevance of this process in muscle diseases, our study highlights a previously unrecognized function of mitochondria in muscles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Terry Partridge for providing the H2K mouse myoblasts, Dr. Susan Knoblach and K. Nagaraju for help in generating SILAM mice, and Dr. Heather Gordish-Dressman for statistical analysis of the proteomics data.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1AR055686 and P50AR060836 (to J. K. J.). The mass spectrometry and microscopy facilities used are supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P30HD040677 (Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center) and R24HD050846 (National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research) and National Institutes of Health, NCRR, Grant UL1RR031988 (George Washington University Children's National Medical Center, Clinical and Translational Science Institute).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S4, Figs. 1 and 2, and Movie 1.

N. Sharma, S. Medikayala, K. J. Brown, Y. Hathout, and J. K. Jaiswal, unpublished observations.

- SILAC

- stable isotope labeling of amino acids in culture

- SILAM

- stable isotope labeling in mammals

- EDL

- extensor digitorum longus

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution

- Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin

- sulfosuccinimidyl-6-[biotin-amido]hexanoate

- RIPA

- radioimmune precipitation assay

- GO

- Gene Ontology

- CCCP

- carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bansal D., Miyake K., Vogel S. S., Groh S., Chen C. C., Williamson R., McNeil P. L., Campbell K. P. (2003) Defective membrane repair in dysferlin-deficient muscular dystrophy. Nature 423, 168–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carpenter S., Karpati G. (1989) Segmental necrosis and its demarcation in experimental micropuncture injury of skeletal muscle fibers. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 48, 154–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Papadimitriou J. M., Robertson T. A., Mitchell C. A., Grounds M. D. (1990) The process of new plasmalemma formation in focally injured skeletal muscle fibers. J. Struct. Biol. 103, 124–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Faulkner J. A., Brooks S. V., Opiteck J. A. (1993) Injury to skeletal muscle fibers during contractions. Conditions of occurrence and prevention. Phys. Ther. 73, 911–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grounds M. D. (1991) Toward understanding skeletal muscle regeneration. Pathol. Res. Pract. 187, 1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wallace G. Q., McNally E. M. (2009) Mechanisms of muscle degeneration, regeneration, and repair in the muscular dystrophies. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71, 37–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bansal D., Campbell K. P. (2004) Dysferlin and the plasma membrane repair in muscular dystrophy. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 206–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chargé S. B., Rudnicki M. A. (2004) Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol. Rev. 84, 209–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cohn R. D., Campbell K. P. (2000) Molecular basis of muscular dystrophies. Muscle Nerve 23, 1456–1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gelfi C., Vasso M., Cerretelli P. (2011) Diversity of human skeletal muscle in health and disease. Contribution of proteomics. J. Proteomics 74, 774–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ohlendieck K. (2011) Skeletal muscle proteomics. Current approaches, technical challenges, and emerging techniques. Skelet. Muscle 1, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Raddatz K., Albrecht D., Hochgräfe F., Hecker M., Gotthardt M. (2008) A proteome map of murine heart and skeletal muscle. Proteomics 8, 1885–1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vitorino R., Ferreira R., Neuparth M., Guedes S., Williams J., Tomer K. B., Domingues P. M., Appell H. J., Duarte J. A., Amado F. M. (2007) Subcellular proteomics of mice gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. Anal. Biochem. 366, 156–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tannu N. S., Rao V. K., Chaudhary R. M., Giorgianni F., Saeed A. E., Gao Y., Raghow R. (2004) Comparative proteomes of the proliferating C2C12 myoblasts and fully differentiated myotubes reveal the complexity of the skeletal muscle differentiation program. Mol. Cell Proteomics 3, 1065–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kislinger T., Gramolini A. O., Pan Y., Rahman K., MacLennan D. H., Emili A. (2005) Proteome dynamics during C2C12 myoblast differentiation. Mol. Cell Proteomics 4, 887–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gundry R. L., Raginski K., Tarasova Y., Tchernyshyov I., Bausch-Fluck D., Elliott S. T., Boheler K. R., Van Eyk J. E., Wollscheid B. (2009) The mouse C2C12 myoblast cell surface N-linked glycoproteome. Identification, glycosite occupancy, and membrane orientation. Mol. Cell Proteomics 8, 2555–2569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seiler S., Fleischer S. (1982) Isolation of plasma membrane vesicles from rabbit skeletal muscle and their use in ion transport studies. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 13862–13871 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seiler S., Fleischer S. (1988) Isolation and characterization of sarcolemmal vesicles from rabbit fast skeletal muscle. Methods Enzymol. 157, 26–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lewis C., Ohlendieck K. (2010) Mass spectrometric identification of dystrophin isoform Dp427 by on-membrane digestion of sarcolemma from skeletal muscle. Anal. Biochem. 404, 197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ohlendieck K., Ervasti J. M., Snook J. B., Campbell K. P. (1991) Dystrophin-glycoprotein complex is highly enriched in isolated skeletal muscle sarcolemma. J. Cell Biol. 112, 135–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Charuk J. H., Howlett S., Michalak M. (1989) Subfractionation of cardiac sarcolemma with wheat germ agglutinin. Biochem. J. 264, 885–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elschenbroich S., Kim Y., Medin J. A., Kislinger T. (2010) Isolation of cell surface proteins for mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Expert Rev. Proteomics 7, 141–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jarrold B., DeMuth J., Greis K., Burt T., Wang F. (2005) An effective skeletal muscle prefractionation method to remove abundant structural proteins for optimized two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 26, 2269–2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huber L. A., Pfaller K., Vietor I. (2003) Organelle proteomics. Implications for subcellular fractionation in proteomics. Circ. Res. 92, 962–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elia G. (2008) Biotinylation reagents for the study of cell surface proteins. Proteomics 8, 4012–4024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peirce M. J., Cope A. P., Wait R. (2009) Proteomic analysis of the lymphocyte plasma membrane using cell surface biotinylation and solution-phase isoelectric focusing. Methods Mol. Biol. 528, 135–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ghosh D., Krokhin O., Antonovici M., Ens W., Standing K. G., Beavis R. C., Wilkins J. A. (2004) Lectin affinity as an approach to the proteomic analysis of membrane glycoproteins. J. Proteome Res. 3, 841–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wollscheid B., Bausch-Fluck D., Henderson C., O'Brien R., Bibel M., Schiess R., Aebersold R., Watts J. D. (2009) Mass spectrometric identification and relative quantification of N-linked cell surface glycoproteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 378–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chaney L. K., Jacobson B. S. (1983) Coating cells with colloidal silica for high yield isolation of plasma membrane sheets and identification of transmembrane proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 10062–10072 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kline K. G., Sussman M. R. (2010) Protein quantitation using isotope-assisted mass spectrometry. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 39, 291–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brewis I. A., Brennan P. (2010) Proteomics technologies for the global identification and quantification of proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 80, 1–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krüger M., Moser M., Ussar S., Thievessen I., Luber C. A., Forner F., Schmidt S., Zanivan S., Fässler R., Mann M. (2008) SILAC mouse for quantitative proteomics uncovers kindlin-3 as an essential factor for red blood cell function. Cell 134, 353–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McClatchy D. B., Liao L., Park S. K., Xu T., Lu B., Yates Iii J. R. (2011) Differential proteomic analysis of mammalian tissues using SILAM. PLoS One 6, e16039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zanivan S., Krueger M., Mann M. (2012) In vivo quantitative proteomics. The SILAC mouse. Methods Mol. Biol. 757, 435–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Donoghue P., Staunton L., Mullen E., Manning G., Ohlendieck K. (2010) DIGE analysis of rat skeletal muscle proteins using nonionic detergent phase extraction of young adult versus aged gastrocnemius tissue. J. Proteomics 73, 1441–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nagaraj N., Lu A., Mann M., Wiśniewski J. R. (2008) Detergent-based but gel-free method allows identification of several hundred membrane proteins in single LC-MS runs. J. Proteome Res. 7, 5028–5032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhao Y., Zhang W., Kho Y., Zhao Y. (2004) Proteomic analysis of integral plasma membrane proteins. Anal. Chem. 76, 1817–1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang Z., Zhang L., Hua Y., Jia X., Li J., Hu S., Peng X., Yang P., Sun M., Ma F., Cai Z. (2010) Comparative proteomic analysis of plasma membrane proteins between human osteosarcoma and normal osteoblastic cell lines. BMC Cancer 10, 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weekes M. P., Antrobus R., Lill J. R., Duncan L. M., Hör S., Lehner P. J. (2010) Comparative analysis of techniques to purify plasma membrane proteins. J. Biomol. Tech. 21, 108–115 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morgan J. E., Beauchamp J. R., Pagel C. N., Peckham M., Ataliotis P., Jat P. S., Noble M. D., Farmer K., Partridge T. A. (1994) Myogenic cell lines derived from transgenic mice carrying a thermolabile T antigen. A model system for the derivation of tissue-specific and mutation-specific cell lines. Dev. Biol. 162, 486–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McNeil A. K., Rescher U., Gerke V., McNeil P. L. (2006) Requirement for annexin A1 in plasma membrane repair. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35202–35207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cai C., Masumiya H., Weisleder N., Matsuda N., Nishi M., Hwang M., Ko J. K., Lin P., Thornton A., Zhao X., Pan Z., Komazaki S., Brotto M., Takeshima H., Ma J. (2009) MG53 nucleates assembly of cell membrane repair machinery. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 56–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhu H., Lin P., De G., Choi K. H., Takeshima H., Weisleder N., Ma J. (2011) Polymerase transcriptase release factor (PTRF) anchors MG53 protein to cell injury site for initiation of membrane repair. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12820–12824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lennon N. J., Kho A., Bacskai B. J., Perlmutter S. L., Hyman B. T., Brown R. H., Jr. (2003) Dysferlin interacts with annexins A1 and A2 and mediates sarcolemmal wound healing. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50466–50473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mellgren R. L. (2010) A plasma membrane wound proteome. Reversible externalization of intracellular proteins following reparable mechanical damage. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 36597–36607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Honscha W., Ottallah M., Kistner A., Platte H., Petzinger E. (1993) A membrane-bound form of protein-disulfide isomerase (PDI) and the hepatic uptake of organic anions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1153, 175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shin B. K., Wang H., Yim A. M., Le Naour F., Brichory F., Jang J. H., Zhao R., Puravs E., Tra J., Michael C. W., Misek D. E., Hanash S. M. (2003) Global profiling of the cell surface proteome of cancer cells uncovers an abundance of proteins with chaperone function. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7607–7616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Negrutskii B. S., El'skaya A. V. (1998) Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1α. Structure, expression, functions, and possible role in aminoacyl-tRNA channeling. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 60, 47–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Doran P., Martin G., Dowling P., Jockusch H., Ohlendieck K. (2006) Proteome analysis of the dystrophin-deficient MDX diaphragm reveals a drastic increase in the heat shock protein cvHSP. Proteomics 6, 4610–4621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sonnemann K. J., Bement W. M. (2011) Wound repair. Toward understanding and integration of single-cell and multicellular wound responses. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 27, 237–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McNeil P. L., Steinhardt R. A. (2003) Plasma membrane disruption. Repair, prevention, and adaptation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 697–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kim B. W., Lee J. W., Choo H. J., Lee C. S., Jung S. Y., Yi J. S., Ham Y. M., Lee J. H., Hong J., Kang M. J., Chi S. G., Hyung S. W., Lee S. W., Kim H. M., Cho B. R., Min D. S., Yoon G., Ko Y. G. (2010) Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system is recruited to detergent-resistant lipid rafts during myogenesis. Proteomics 10, 2498–2515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tarnopolsky M. A., Raha S. (2005) Mitochondrial myopathies. Diagnosis, exercise intolerance, and treatment options. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 37, 2086–2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Howard A. C., McNeil A. K., McNeil P. L. (2011) Promotion of plasma membrane repair by vitamin E. Nat. Commun. 2, 597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.