Background: β-Scorpion toxins enhance activation of voltage-gated sodium (NaV) channels.

Results: Four amino acid residues in the IIISS2-S6 extracellular loop contribute to toxin binding and efficacy.

Conclusion: The pore module of domain III and the voltage-sensing module of domain II form the receptor site.

Significance: Scorpion toxins make a three-point interaction with NaV channels and alter voltage sensor function.

Keywords: Nerve, Neurotoxin, Signal Transduction, Sodium Channels, Sodium Transport, β-Scorpion Toxin, Neuromuscular Paralysis, Voltage-gated Sodium Channels, Voltage-sensor Trapping

Abstract

Activation of voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels initiates and propagates action potentials in electrically excitable cells. β-Scorpion toxins, including toxin IV from Centruroides suffusus suffusus (CssIV), enhance activation of NaV channels. CssIV stabilizes the voltage sensor in domain II in its activated state via a voltage-sensor trapping mechanism. Amino acid residues required for the action of CssIV have been identified in the S1-S2 and S3-S4 extracellular loops of domain II. The extracellular loops of domain III are also involved in toxin action, but individual amino acid residues have not been identified. We used site-directed mutagenesis and voltage clamp recording to investigate amino acid residues of domain III that are involved in CssIV action. In the IIISS2-S6 loop, five substitutions at four positions altered voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A. Three substitutions (E1438A, D1445A, and D1445Y) markedly decreased voltage-sensor trapping, whereas the other two substitutions (N1436G and L1439A) increased voltage-sensor trapping. These bidirectional effects suggest that residues in IIISS2-S6 make both positive and negative interactions with CssIV. N1436G enhanced voltage-sensor trapping via increased binding affinity to the resting state, whereas L1439A increased voltage-sensor trapping efficacy. Based on these results, a three-dimensional model of the toxin-channel interaction was developed using the Rosetta modeling method. These data provide additional molecular insight into the voltage-sensor trapping mechanism of toxin action and define a three-point interaction site for β-scorpion toxins on NaV channels. Binding of α- and β-scorpion toxins to two distinct, pseudo-symmetrically organized receptor sites on NaV channels acts synergistically to modify channel gating and paralyze prey.

Introduction

Voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels initiate action potentials in nerve and muscle (1). They activate and then inactivate on the millisecond time scale to generate a pulse of inward sodium current that underlies the rising phase of the action potential. The α subunit of Nav channels has four homologous domains (I–IV), and each domain is composed of six transmembrane segments, S1-S6 (2). The first four segments, S1-S4, form the voltage-sensing module, and 4–8 positively charged arginine or lysine residues at every third position in the S4 segment serve as gating charges (2). The S5-S6 segments form the pore module, and the short SS1 and SS2 segments between them form the vestibule and narrow selectivity filter at the extracellular end of the pore (2). The three-dimensional arrangement of these segments has been defined by x-ray crystallography of mammalian Kv1.2 channels (3), a Kv1.2-Kv2.1 chimera (4), and the bacterial NaV channel, NavAb (5).

Several classes of neurotoxins act at distinct receptor sites on NaV channels (6, 7). The α-scorpion toxins bind at neurotoxin receptor site 3 and slow NaV inactivation, whereas the β-scorpion toxins bind at neurotoxin receptor site 4 and enhance activation (7). These effects work together to depolarize nerve and muscle fibers and cause conduction block. β-Scorpion toxins are thought to act via a voltage-sensor trapping mechanism in which the bound toxin binds and stabilizes the voltage sensor in domain II in its activated conformation (8, 9). Toxin derivatives can act as agonists or competitive antagonists of voltage-sensor trapping (10). Previous ligand binding (8, 9) and electrophysiological studies (11) defined a molecular map of the receptor site for β-scorpion toxin IV of Centruroides suffusus suffusus (CssIV)3 in the S1-S2 (IIS1-S2) and S3-S4 (IIS3-S4) extracellular loops of the voltage-sensing module in domain II. Structural studies of homotetrameric NaV and KV channels show that the S5-S6 loop in each subunit is in close proximity to the S1-S2 and S3-S4 loops of the adjacent subunit (3–5). Therefore, the conformational change of the voltage-sensing module of one subunit in response to depolarization can be transmitted to the pore module of the neighboring subunit in clockwise direction to open the central ion conduction pore. Analysis of channel chimeras showed that the IIISS2-S6 region is important in binding of β-scorpion toxins (8) and in determining the specificity for binding of a β-scorpion toxin to individual Nav channel subtypes (12). These results led us to hypothesize that the single receptor site for the β-scorpion toxin CssIV in Nav channels (8) is formed by IIS1-S2, IIS3-S4, and IIISS2-S6 extracellular loops. In the present work, we mapped the individual amino acid residues that contribute to the receptor site for the β-scorpion toxin derivative CssIVE15A. Five substitutions at four positions in the region between Asn1436 and Asp1445 altered toxin binding and/or efficacy for voltage-sensor trapping. Three of them markedly decreased voltage-sensor trapping, whereas two increased voltage-sensor trapping. These bidirectional effects suggest that residues in IIISS2-S6 make both positive and negative interactions with bound toxin. Our data show that IIS3-S4 plays a primary role, whereas IIS1-S2 and IIISS2-S6 play important secondary roles, in determining binding affinity and efficacy at a single β-scorpion toxin receptor site. They also indicate that the SS2-S6 loop in domain III is in close proximity to the voltage-sensing module of domain II in mammalian NaV channels, as suggested by the structure of bacterial NaV channels (5).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Scorpion Toxin

A high-affinity mutant derivative of toxin IV from C. suffusus suffusus, CssIVE15A (11), was used for all experiments. It was prepared as described previously (11).

Mutagenesis

PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis was employed to generate single point mutations in WT rNav1.2 cDNA (9, 11). Alanine-scanning mutagenesis was performed on the majority of the residues in IIISS2-S6 region. Chimeras were constructed for residues that are not conserved between β-scorpion toxin-sensitive rNav1.2 and β-scorpion toxin-resistant hNav1.5 channels. For some charged residues, charge-reversal mutants were also generated to explore the role of charged amino acid side chains in voltage-sensor trapping of the β-scorpion toxin. All the WT and mutant cDNAs were subcloned into the pCDM8 vector (13).

cDNA Transfection

Detailed cDNA transfection procedures have been described elsewhere (9, 11). cDNAs encoding WT or mutant rNav1.2a channels were co-transfected into tsA-201 cells with the marker protein pEBO-pCD8-leu2 using the calcium phosphate method. Transfected cells were subcloned 12–18 h after transfection, and electrophysiological recordings were carried out 1–24 h later. WT and mutant rNav1.2a cDNAs were always transfected in parallel to ensure that differences from WT were truly caused by mutations. Polystyrene microspheres conjugated with anti-CD8 antibody were added in the extracellular recording solution to identify the cell surface CD8 protein as a marker of cells expressing NaV1.2 channels.

Electrophysiological Recording and Data Analysis

The whole cell patch clamp configuration was utilized to record Na+ current. The extracellular recording solution contained (in mm) NaCl (150), Cs-HEPES (10), MgCl2 (1), KCl (2), CaCl2 (1.5), and 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4. The intracellular recording solution contained (in mm) N-methyl-d-glucamine (190), HEPES (10), MgCl2 (10), NaCl (10), and EGTA (5), pH 7.4. Linear leak and capacitance currents were subtracted using an online P/−4 subtraction paradigm. To assess the extent of negative shift of the voltage dependence of activation caused by CssIVE15A, tsA-201 cells were held at −100 mV and test depolarizations were applied to potentials from −100 to +20 mV in 5-mV increments. Current-voltage (I-V) plots were generated from peak currents elicited at each test potential. The test depolarization was either applied alone or was preceded by a 1-ms prepulse to +50 mV followed by a 60-ms interval at the holding potential. We tested the functional properties of each mutant rNav1.2a construct in the absence of toxin to examine the effect of the mutant residue, followed by recordings in the presence of CssIVE15A. The voltage dependence and kinetics of each mutant channel were initially screened with 500 nm CssIVE15A to detect differences from WT. All data were analyzed with Igor Pro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Normalized I-V curves were fit with a function including a one-component Boltzmann equation of the form (V − Vrev) × Gmax/(1 + exp[(V½ − V)/k]), where V½ is the half-activation voltage in mV, and k is a slope factor in mV. In the presence of both CssIVE15A and a prepulse, I-V plots were fit with a two-component Boltzmann equation. All data are presented as mean ± S.E. The mean values for voltage dependence of activation and inactivation for all mutants are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

TABLE 1.

Voltage dependence of activation

The current-voltage relationship of WT and mutant channels was measured as described under ”Experimental Procedures“ under control conditions without toxin. The voltage of half-activation (V0.5) and slope factor of each channel were derived from fitting the corresponding voltage-dependent activation curve with a single Boltzmann equation. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.

| Channel | V0.5 | Slope | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| mV | |||

| WT | −30.8 ± 0.8 | −5.4 ± 0.3 | 7 |

| N1436G | −31.5 ± 0.7 | −5.1 ± 0.2 | 5 |

| E1438A | −33.9 ± 1.0 | −4.8 ± 0.2 | 5 |

| L1439A | −29.2 ± 0.9 | −6.1 ± 0.1 | 5 |

| D1445A | −32.5 ± 0.4 | −4.9 ± 0.3 | 5 |

| D1445Y | −32.4 ± 1.1 | −4.8 ± 0.2 | 5 |

TABLE 2.

Voltage dependence of activation with CssIVE15A

The voltage dependence of activation was measured as described under ”Experimental Procedures“ in the presence of 500 nm CssIVE15A but without the prepulse. The voltage of half-activation (V0.5) and slope factor of each channel were derived from fitting the corresponding voltage-dependent activation curve with a single Boltzmann equation. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.

| Channel | V0.5 | Slope | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| mV | |||

| WT | −30.5 ± 0.5 | −6.0 ± 0.1 | 33 |

| N1436G | −29.1 ± 1.3 | −5.4 ± 0.4 | 7 |

| E1438A | −30.3 ± 0.8 | −5.7 ± 0.2 | 7 |

| L1439A | −32.3 ± 2.4 | −6.5 ± 0.3 | 5 |

| D1445A | −29.4 ± 0.9 | −5.1 ± 0.3 | 4 |

| D1445Y | −32.0 ± 1.0 | −5.1 ± 0.3 | 5 |

Structural Modeling of the CssIV-Nav1.2 Complex

Homology and de novo modeling of the voltage-sensing module of domain II and pore-forming module of domain III of the rat Nav1.2 channel was performed using the Rosetta-membrane method (14–16). The voltage-sensing module (residues Val748–Gly879) and pore-forming module (residues Ser1336–Phe1476) from Nav1.2 were aligned with the voltage-sensing module (residues Met1–Pro128) and pore-forming module (residues Gly129–Met221) from the NavAb channel (5), respectively, using ClustalX software (17). 5,000 models were generated in the first round of modeling using cyclic coordinate descent loop modeling (18) in the Rosetta-membrane method followed by model clustering (19). The 20 largest clusters of models from the first round of modeling were then used as input for the second round of modeling using the kinematic loop modeling protocol (20) in the Rosetta-membrane method followed by model clustering (19). The centers of the largest clusters of models and the lowest energy models were visually examined, and the best NaV1.2 model was chosen based on a fit with available experimental data on key residues contributing to interaction between the β-scorpion CssIV toxin and the Nav1.2 channel (8, 9, 11, 21). Modeling of the β-scorpion toxin was performed using the Rosetta method for modeling of soluble proteins (22) and the structure of neurotoxin 2 (X8, PDB 1JZA) using ClustalX software (17). The β-scorpion CssIV toxin model was then docked with the best NaV1.2 model in the same starting orientation as in a recently published model of β-scorpion CssIV complex with the NaV1.2 voltage-sensing module of domain II (11). The docked model of β-scorpion CssIV toxin bound to the voltage-sensing module of domain II and pore-forming module of domain III of NaV1.2 was then subjected to Rosetta full atom relax protocol (22) using 1000 independent simulations and the lowest energy model was chosen as the best model.

RESULTS

Modification of Voltage-dependent Activation of WT rNav1.2a Channels by CssIVE15A

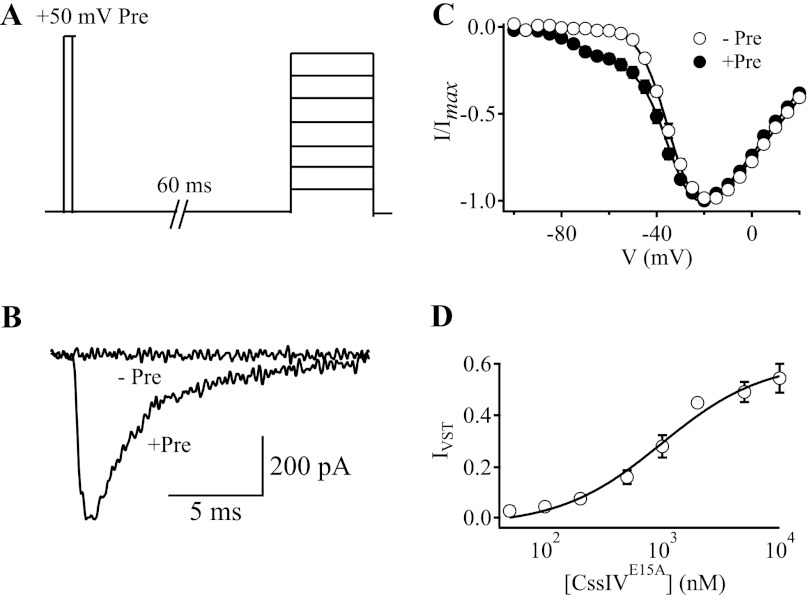

As in our previous work (11), we used the toxin mutant CssIVE15A, which has increased affinity but an identical mechanism of action compared with CssIV itself. We measured voltage-sensor trapping using a three-pulse protocol in the whole cell patch clamp configuration. Following equilibration of the toxin with its receptor sites, cells were depolarized to 50 mV for 1 ms to activate the voltage sensor and allow voltage-sensor trapping, repolarized to the holding potential of −100 mV for 60 ms to allow recovery of the channels from fast inactivation, and finally depolarized to a range of test pulse potentials to record Na+ current (Fig. 1A). As reported previously (11), CssIVE15A shifted the voltage dependence of activation of WT rNav1.2a channels to more negative membrane potentials, but only following the strong depolarizing prepulse (11). In the presence of 500 nm CssIVE15A but with no prepulse, WT rNav1.2a channels did not conduct Na+ current at a test potential of −60 mV (Fig. 1B). In contrast, when a 1-ms prepulse to 50 mV was applied 60 ms before each test pulse, marked Na+ current was observed at −60 mV (Fig. 1B), and a substantial component of the Na+ current was activated with a negatively shifted voltage dependence (Fig. 1C). With 500 nm CssIVE15A, a mean of 16.2% of the peak Na+ current was activated at −60 mV (Fig. 1, B and C, and Table 3). The additional current generated by depolarization to −60 mV following a strong, short-duration prepulse was termed “IVST,“ for voltage-sensor trapping current (11). Fitting a function with two Boltzmann components to the +Pre I-V curve (Fig. 1C) yielded the following fitting parameters: Va1 = −34.2 ± 0.9 mV, k1 = −6.4 ± 0.2 mV, Va2 = −76.1 ± 1.3 mV, k2 = −6.4 ± 0.4 mV. In this equation, Va1 and k1 are the voltage of half-maximal activation and the slope factor of the first Boltzmann component, respectively, and Va2 and k2 are the voltage of half-maximal activation and the slope factor of the second, more negatively shifted component, respectively (Fig. 1C). The negatively shifted component represented 9.4 ± 0.02% of the total conductance of the +Pre curve. Fitting the concentration-response curve (IVST versus toxin concentration) with a first-order Hill equation resulted in an EC50 of 1100 nm for toxin binding to WT rNav1.2a channels in the resting state (Fig. 1D). These data suggest that CssIVE15A binds to WT rNav1.2a channels in the resting state and, in response to strong, transient depolarization, traps the voltage sensor in its activated state. In the following sections, we first describe the functional properties of several informative mutants, followed by presentation of a two-dimensional molecular map and three-dimensional model of the toxin-receptor interaction in the IIISS2-S6 region.

FIGURE 1.

Voltage-sensor trapping activity of CssIVE15A on WT rNav1.2a channels. The cell membrane was depolarized to a series of potentials ranging from −100 to +20 mV in 5-mV increments with or without a +50 mV, 1-ms conditioning prepulse. When used, the prepulse was applied 60 ms earlier than the I-V pulse protocols. A, pulse protocol with a +50-mV, 1-ms prepulse. B, voltage-sensor trapping current, IVST, in response to 15-ms test pulse depolarizations to −60 mV. The traces were acquired with (+Pre) or without (−Pre) the prepulse. C, I-V plots obtained for WT rNav1.2a channel with (filled circles, +Pre) or without (open circles, −Pre) the prepulse. The solid lines are global fits of a function with 2 Boltzmann components to the I-V curves without and with prepulses. D, IVST concentration plot with the prepulse (open circles). IVST was normalized to the maximal peak current of the I-V plot in the presence of the prepulse. IVST concentration data were fit with first-order Hill equations (n ≥ 4). Error bars represent S.E.

TABLE 3.

IVST and EC50 of WT and mutant channels in the presence of CssIVE15A

IVST is the normalized voltage-sensor trapping current observed at a test pulse to −60 mV following a prepulse (see text). For channels in which saturating effects of CssIVE15A could be recorded, KD values were calculated from fitting the data to the voltage-sensor trapping model. IVST data are presented as mean ± S.E.

| Channel | Concentration | IVST (+Pre) | n | EC50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | nm | |||

| WT | 50 | 3.2 ± 1.7% | 3 | 1100 |

| 100 | 5.0 ± 0.9% | 8 | ||

| 200 | 7.9 ± 1.0% | 6 | ||

| 500 | 16.2 ± 2.6% | 5 | ||

| 1,000 | 28.0 ± 4.3% | 4 | ||

| 2,000 | 44.8 ± 1.0% | 5 | ||

| 5,000 | 48.9 ± 3.9% | 10 | ||

| 10,000 | 54.2 ± 5.5% | 3 | ||

| N1436G | 20 | 9.24 ± 1.0% | 6 | 274.2 |

| 50 | 11.5 ± 2.5% | 4 | ||

| 100 | 17.5 ± 2.9% | 9 | ||

| 200 | 28.5 ± 2.8% | 12 | ||

| 500 | 38.2 ± 3.8% | 7 | ||

| E1438A | 500 | 3.7 ± 0.54% | 7 | NAa |

| L1439A | 100 | 6.6 ± 1.8% | 7 | 1071.5 |

| 200 | 17.4 ± 2.1% | 5 | ||

| 500 | 31.3 ± 6.6% | 5 | ||

| 1,000 | 38.0 ± 4.6% | 8 | ||

| 2,000 | 59.7 ± 3.9% | 4 | ||

| 5,000 | 71.6 ± 6.7% | 4 | ||

| D1445A | 500 | 4.8 ± 0.7% | 4 | NA |

| D1445Y | 500 | 0.4 ± 0.3% | 5 | NA |

a NA, not applicable.

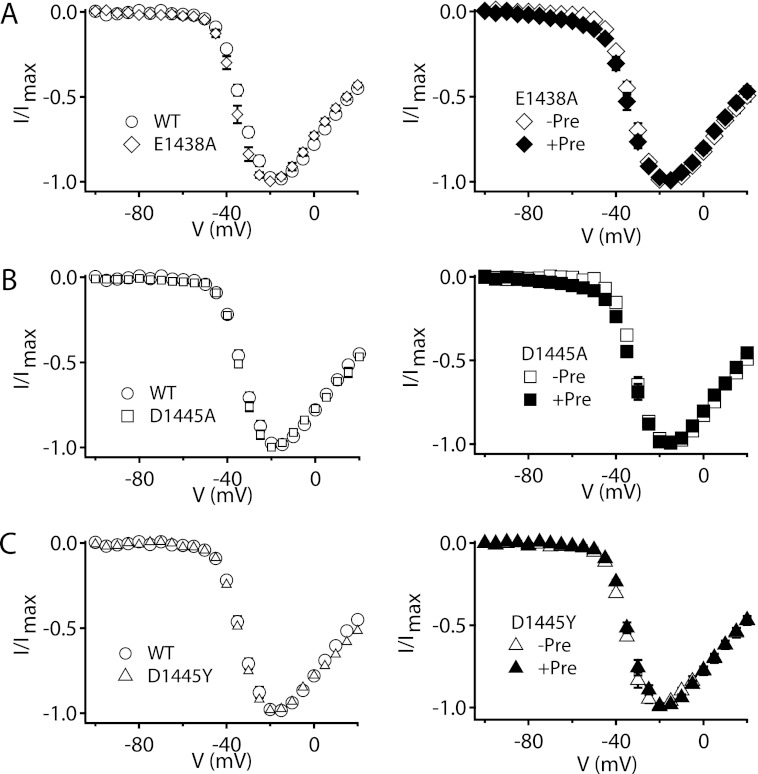

Loss of Voltage-sensor Trapping by CssIVE15A with NaV1.2a Mutants E1438A, D1445A, and D1445Y

In the absence of toxin, mutation E1438A in NaV1.2a channels did not affect the I-V relationship compared with WT (Fig. 2A, left, Table 1). These results indicate that this mutation does not alter the voltage-dependent activation of Na+ channels. As for WT channels, 500 nm CssIVE15A did not induce detectable Na+ current when cells expressing E1438A channels were depolarized to −60 mV without a preceding depolarizing prepulse (Fig. 2A, right, Table 2). However, the I-V relationship of NaV1.2a/E1438A was altered only slightly by a 1-ms depolarizing prepulse to 50 mV in the presence of CssIVE15A (Fig. 2A, right), and IVST was only 3.67 ± 0.54% at 500 nm (Table 3). These results show that CssIVE15A had reduced voltage-sensor trapping activity on the NaV1.2a/E1438A mutant channel. This lack of effect on NaV1.2a/E1438A could be caused by decreased binding affinity to the resting state, decreased voltage-sensor trapping efficacy, or a combination of both effects.

FIGURE 2.

Voltage-sensor trapping activity of CssIVE15A on E1438A, D1445A, and D1445Y mutant NaV1.2a channels. Left column, I-V plots of WT rNav1.2 (open circles), E1438A (open diamonds, A), D1445A (open squares, B), and D1445Y (open triangles, C) mutant channels in the absence of toxin; right column, I-V plots of E1438A (A), D1445A (B), and D1445Y (C) mutant channels in the presence of 500 nm CssIVE15A with (filled symbols, +Pre) or without (open symbols, −Pre) a prepulse.

The mutations NaV1.2a/D1445A and NaV1.2a/D1445Y also impaired voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A (Fig. 2, B and C, Table 3). Neither NaV1.2a/D1445A nor NaV1.2a/D1445Y altered the I-V relationships in the absence of toxin (Fig. 2, B and C, left, Table 1). These results indicate that neither mutation altered the voltage dependence of activation of Nav channels. For NaV1.2a/D1445A, IVST was decreased to 4.8 ± 0.7% at 500 nm CssIVE15A compared with 16.2 ± 2.6% for WT. Interestingly, a single residue chimera between β-toxin-sensitive rNav1.2 and β-toxin-insensitive hNav1.5 at the same locus, D1445Y, completely abolished voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A at 500 nm (Fig. 2C, right, Table 3). These results suggest that Asp1445 is crucial for modification of voltage dependence of activation of Nav channels by CssIVE15A. The mutations NaV1.2a/D1445A and NaV1.2a/D1445Y might reduce voltage-sensor trapping activity by CssIVE15A via reduced toxin binding affinity for the resting state, decreased voltage-sensor trapping efficacy, or a combination of both effects.

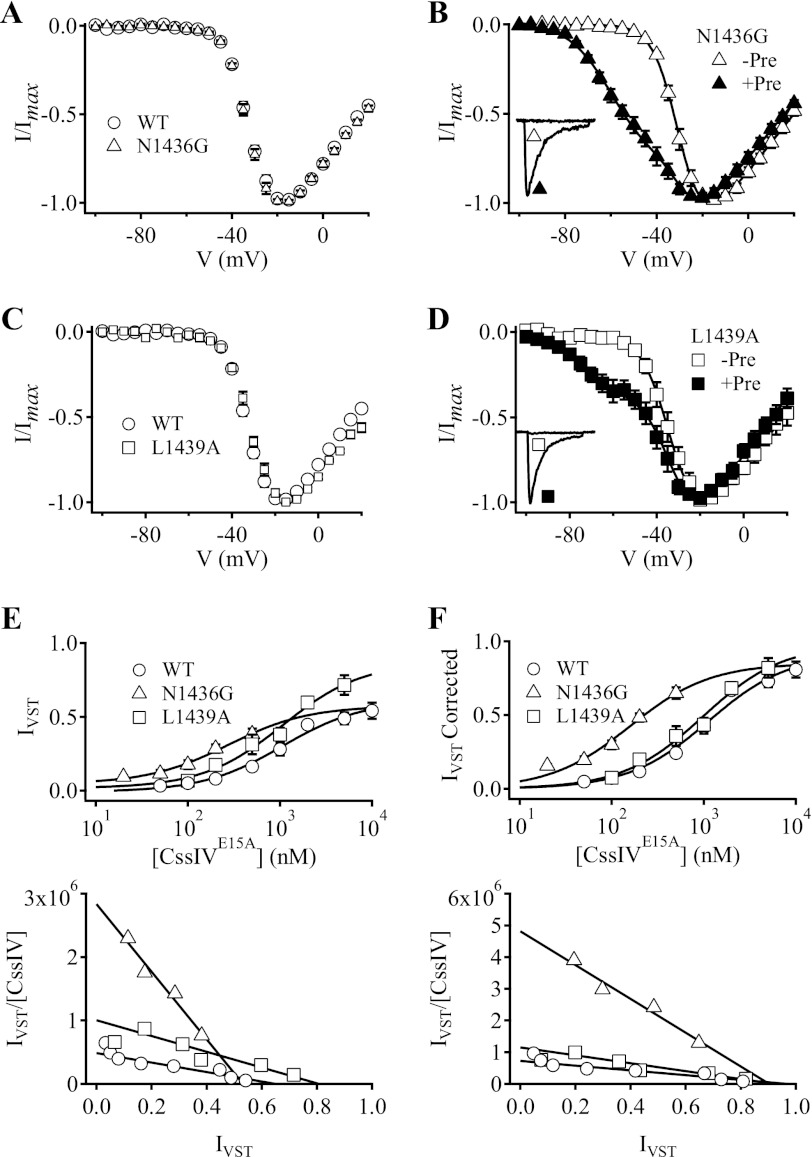

Increased Voltage-sensor Trapping with NaV1.2a Mutants N1436G and L1439A

In our previous studies, we identified three consecutive mutations in the IIS3-S4 extracellular linker that markedly enhanced voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A (11). This enhancement resulted from substantially increased binding affinity of CssIVE15A to the resting state of the mutant channels (11). In our present study of the IIISS2-S6 region, we identified two mutations (N1436G and L1439A) that greatly enhance voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A.

Mutation NaV1.2a/N1436G did not affect the I-V relationship compared with WT in the absence of toxin, indicating that voltage-dependent activation of the mutant channel remained unchanged (Fig. 3A, Table 1). Similarly, in the presence of 500 nm CssIVE15A but with no prepulse, the voltage-dependent activation of mutant NaV1.2a/N1436G was no different from WT (Fig. 3B, Table 2). No IVST was detectable at −60 mV without the prepulse (Fig. 3B, inset). However, following a 1-ms prepulse to 50 mV in the presence of 500 nm CssIVE15A, IVST increased to 38.2 ± 3.8% (Fig. 3B), which was 2.4-fold greater than WT. Fitting the concentration-response curve for this mutant with a first-order Hill equation yielded an efficacy for voltage-sensor trapping by bound CssIV that was similar to WT, but an EC50 that was lower than WT (Fig. 3E, top). Re-plotting these data in a Scatchard-like plot reveals the decrease in EC50 for voltage-sensor trapping by NaV1.2/N1436G as an increase in slope (Fig. 3E, bottom). In our voltage-sensor trapping protocol, we must repolarize to −100 mV to allow for recovery from fast inactivation after the prepulse to 50 mV induces voltage-sensor trapping (Fig. 1A). Inevitably, there is a partial reversal of voltage-sensor trapping during this repolarization. Correction for this loss of IVST during the 60-ms repolarization in our voltage-sensor trapping protocol further illustrates the shift of the EC50 for voltage-sensor trapping by NaV1.2a/N1436G to lower concentrations in both concentration-response curve and Scatchard-like formats (Fig. 3F). These data suggest that the NaV1.2a/N1436G mutation enhances voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A by increasing toxin binding affinity to N1436G channels in the resting state. The values for EC50 derived from these results obtained with preincubation of toxin at −100 mV are essentially equivalent to the Kd for binding of CssIVE15A to the resting state of the voltage sensor, according to the biophysical model of voltage-sensor trapping developed previously (11).

FIGURE 3.

Voltage-sensor trapping activity of CssIVE15A on N1436G and L1439A mutant NaV1.2 channels. A, normalized I-V plots obtained in the absence of toxin for WT (open circles) and N1436G mutant channels (open triangles). B, normalized I-V plots for N1436G mutant channels in the presence of 500 nm CssIVE15A with (filled triangles, +Pre) or without (open triangles, −Pre) a +50-mV, 1-ms prepulse. Inset, IVST traces recorded in the presence of 500 nm CssIVE15A with a 15-ms test pulse to −60 mV in the absence (open triangle) or presence (filled triangle) of the prepulse. The solid lines are global fits to I-V curves with and without a prepulse with parameters Va1 = −29.6 mV, k1 = −5.5 mV, Va2 = −56.5 mV, k2 = −9.6 mV. 0% conductance was activated with the more negative voltage dependence without the prepulse, whereas 56.4% of the total conductance was activated with the more negative voltage dependence with the prepulse. C, I-V plots obtained in the absence of toxin for WT rNav1.2a channels (circles) and L1439A mutant channels (squares). D, I-V plots for L1439A mutant channels in the presence of 500 nm CssIVE15A with (filled squares, +Pre) or without (open squares, −Pre) the prepulse. Inset, IVST traces recorded in the presence of 500 nm CssIVE15A with a 15-ms depolarizing test pulse to −60 mV in the absence (open square) or presence (filled squares) of a +50-mV, 1-ms prepulse 60 ms earlier. The solid lines are global fits to I-V curves with and without prepulses with parameters Va1 = −32.8 mV, k1 = −6.4 mV, Va2 = −70.2 mV, k2 = −10.3 mV. 0% conductance was activated with the more negative voltage dependence without the prepulse, whereas 24.5% of the total conductance was activated with the more negative voltage dependence with the prepulse. E, top, concentration-response curves for normalized IVST of WT, N1436G (open triangles), and L1439A (open squares) mutant channels induced by CssIVE15A following the prepulse. IVST values were normalized to the current at the peak of the I-V curves for the corresponding mutants in the presence of toxin. The concentration-response data were fit with first-order Hill equations (n > = 4). Bottom, the same results are re-plotted as a Scatchard-like plot, in which the slope is proportional to Kd and the intercept is maximum IVST. Note the reduced apparent Kd (i.e. increased slope) for N1436G compared with the increased in maximum IVST for L1439A. F, the results from panel E were re-plotted after correction for the loss of IVST during the 60-ms repolarization to −100 mV.

As we observed for NaV1.2a/N1436G, the voltage dependence of activation of the L1439A mutant was similar to WT in the absence of CssIVE15A (Fig. 3C, Table 1). In the presence of 500 nm CssIVE15A but with no prepulse, the voltage-dependent activation of L1439A was not altered either (Fig. 3D, Table 2). However, following a 1-ms prepulse to 50 mV in the presence of 500 nm CssIVE15A, IVST was increased to 31.3 ± 6.6% (Fig. 3D, Table 3), 1.9-fold greater than WT. Fitting the concentration-response curve for this mutant with a first-order Hill equation revealed greater efficacy than for WT (Fig. 3E). On the other hand, the EC50 was similar to WT after correction for loss of IVST during the 60-ms repolarization step in our stimulus protocol (Fig. 3F). These data suggest that the L1439A mutation enhanced voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A in a different manner than for NaV1.2a/N1436G, increasing the efficacy of voltage-sensor trapping by bound CssIVE15A rather than increasing binding affinity to resting Nav channels. The effect of the L1439A mutation on efficacy was diminished when the results were corrected for loss of IVST during repolarization (compare Fig. 3, E and F). This comparison suggests that the primary effect of the L1439A mutation is to slow the reversal of voltage-sensor trapping upon repolarization, and this effect is compensated for by the correction for loss of voltage-sensor trapping upon repolarization to −100 mV applied in Fig. 3F. This mechanism derives further support from kinetic analysis of the rates of onset and reversal of voltage-sensor trapping below.

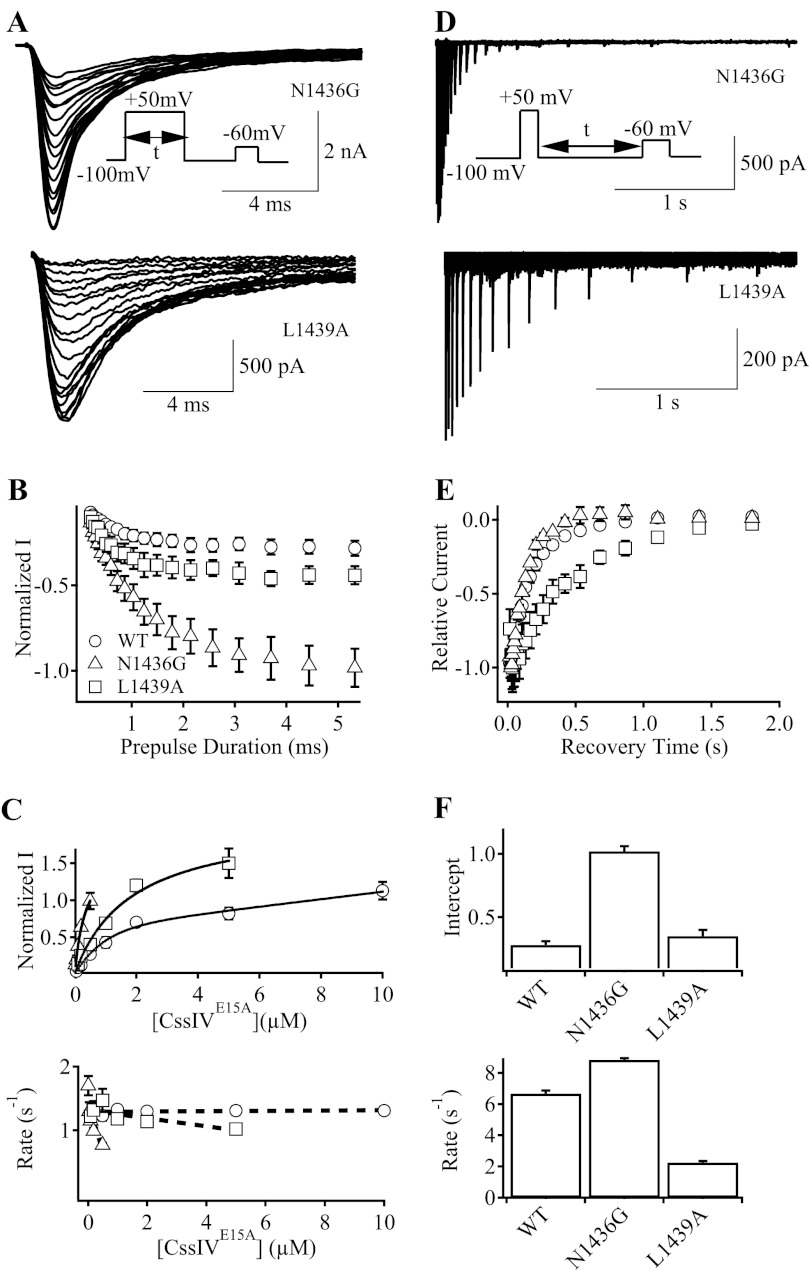

Differences in the efficacy of voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A for mutants NaV1.2a/N1436G and NaV1.2a/L1429A might arise from differences in the rate of onset of voltage-sensor trapping at the prepulse potential and/or in the rate of reversal of voltage-sensor trapping upon repolarization. To measure the rate of onset of voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A, we varied the duration of the prepulse to 50 mV from 0 to 5 ms, followed by a 60-ms interval of repolarization at the holding potential and a 15-ms test pulse to −60 mV (Fig. 4A, inset) and recorded the increase in IVST with increasing prepulse duration (Fig. 4A). These values for IVST after prepulses of increasing duration were normalized to the maximal peak current of a preceding I-V plot measured with no prepulse (Fig. 4B). In this experimental protocol, IVST increased with prepulse duration and reached a maximal effect at ∼1 ms for NaV1.2a/L1439A and ∼4 ms for NaV1.2a/N1436G (Fig. 4B). The extent of voltage-sensor trapping also increased with toxin concentration for both mutants as expected for a bimolecular binding reaction between CssIV and its receptor site in the resting state of Na+ channels (Fig. 4C, top). The increase was greatest for the N1436G mutant because of its higher toxin-binding affinity. The rate constants for onset of voltage-sensor trapping did not increase with toxin concentration (Fig. 4C, bottom). These results are consistent with our three-step model for voltage-sensor trapping in which the final trapping step is concentration independent (8, 9, 11). However, the rate constant for the onset of voltage-sensor trapping decreased significantly with toxin concentration for N1436G, consistent with slowed activation of toxin-bound channels (see “Discussion”).

FIGURE 4.

Rates of the development and recovery of voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A on N1436G and L1439A mutant channels. To measure the rates of the development of voltage-sensor trapping (A–C), the cell membrane was depolarized to +50 mV for durations that varied from 0 to 5 ms, followed by repolarization to the holding potential for 60 ms and by a 15-ms depolarizing test pulse to −60 mV (A, upper panel inset). A, IVST traces at −60 mV for N1436G (upper panel) and L1439A (lower panel) mutant channels. Some traces were omitted for clarity. B, plots of normalized IVST versus prepulse duration for WT rNav1.2a (circles), N1436G (squares), and L1439A (triangles) channels. C, magnitude of IVST (upper panel) and the time constants (lower panel) of the development of voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A in WT rNav1.2a, N1436G, and L1439A channels at a series of CssIVE15A concentrations. To measure the rates of recovery from voltage-sensor trapping (D–F), the cell membrane was depolarized to +50 mV for 1 ms followed by a repolarization to the resting potential for 20–3000 ms and by a test pulse to −60 mV for 15 ms (D, inset). D, IVST traces for N1436G (upper panel) and L1439A mutant channels (lower panel). E, plots of peak IVST in D versus recovery time for WT rNav1.2a (open circles), N1436G (open squares), and L1439A (open triangles) channels. F, intercept extrapolated to t = 0 (upper panel) and time constants (lower panel) of the recovery of the voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A in WT rNav1.2a, N1436G and L1439A mutant channels.

To measure the rate of reversal of voltage-sensor trapping, we depolarized the cell to 50 mV for 1 ms, followed by repolarization to the resting membrane potential for 0–3,000 ms, and depolarization to −60 mV for 15 ms to measure IVST (Fig. 4D, inset), and we measured the peak values for IVST during repetitive application of this pulse protocol with increasing repolarization times (Fig. 4D). These values for IVST were normalized to the maximal peak current from a preceding I-V plot with no prepulse. The rate of reversal of voltage-sensor trapping at −100 mV for NaV1.2a/N1436G was comparable with WT (Fig. 4, E, and F, bottom). In contrast, the rate of reversal of voltage-sensor trapping at −100 mV was substantially decelerated for NaV1.2a/L1439A (Fig. 4, E, and F, bottom). On the other hand, the extent of voltage-sensor trapping was greatest for N1436G because of its high toxin-binding affinity (Fig. 4F, top). The striking differences in the kinetics of onset and reversal of voltage-sensor trapping for N1436G and L1439A mutants are considered further under “Discussion.”

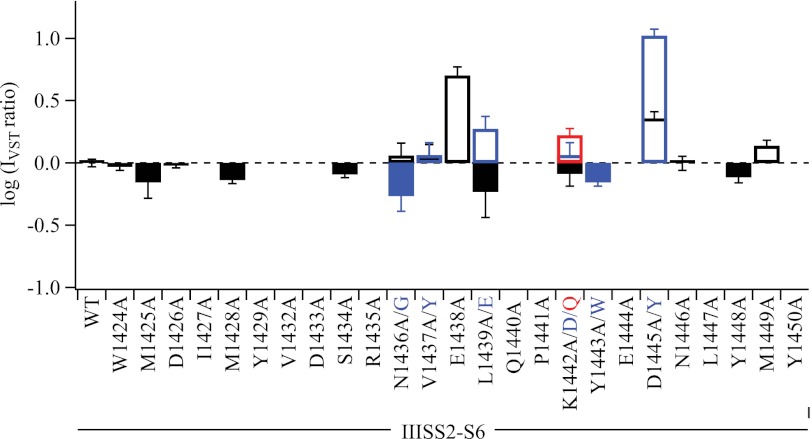

A Molecular Map of the β-Scorpion Toxin Receptor Site in the IIISS2-S6 Loop

Our previous studies of NaV1.2a channel chimeras implicated the extracellular IIS1-S2 and IIS3-S4 loops of Nav channels in formation of the receptor site for β-scorpion toxins and defined several amino acid residues in the IIS1-S2 and IIS3-S4 linkers that contribute to the receptor site for β-scorpion toxin CssIVE15 (8, 9, 11). To complete the mapping of the receptor site for β-scorpion toxin on Nav channels, we constructed 32 mutants by substitutions for 25 residues in IIISS2-S6. Unfortunately, 11 of those mutants did not conduct detectable Na+ current when expressed in tsA-201 cells. A linear map of the functional effects of the remaining 21 mutants is illustrated in Fig. 5 in terms of the IVST ratio (mutant/WT). This partial scan of amino acid residues in IIISS2-S6 revealed several positions of interest (Fig. 5). Four residues in the IIISS2-S6 loop (Asn1436, Glu1438, Leu1439, and Asp1445) are important for CssIV voltage-sensor trapping, but they are not as closely co-localized in the linear amino acid sequence as the hot spot of consecutive residues observed in IIS3-S4 (11). Mutations of these amino acid residues can either increase or decrease voltage-sensor trapping by CssIVE15A. These results uncover a substantial role for single amino acid residues in the IIISS2-S6 loop in voltage-sensor trapping of CssIV toxin. However, compared with our previous experiments (11), these effects are weaker than those in the IIS3-S4 loop. Therefore, our results as a whole suggest that the IIS3-S4 loop plays the primary role in binding and voltage-sensor trapping by CssIV toxin and controls the functional effects of the toxin, whereas IIS1-S2 and IIISS2-S6 segments play important, but secondary roles.

FIGURE 5.

Voltage-sensor trapping activity of CssIVE15A in WT and mutant Nav1.2a channels in IIISS2-S6 extracellular linker. IVST ratio was defined as IVST(mut)/IVST(WT) and plotted as a logarithm. At some loci multiple mutants were studied and the data corresponding to each mutant and its corresponding tick label are color-coded. For instance, L1439A and L1439E are plotted in black and blue, respectively, in the bar graph.

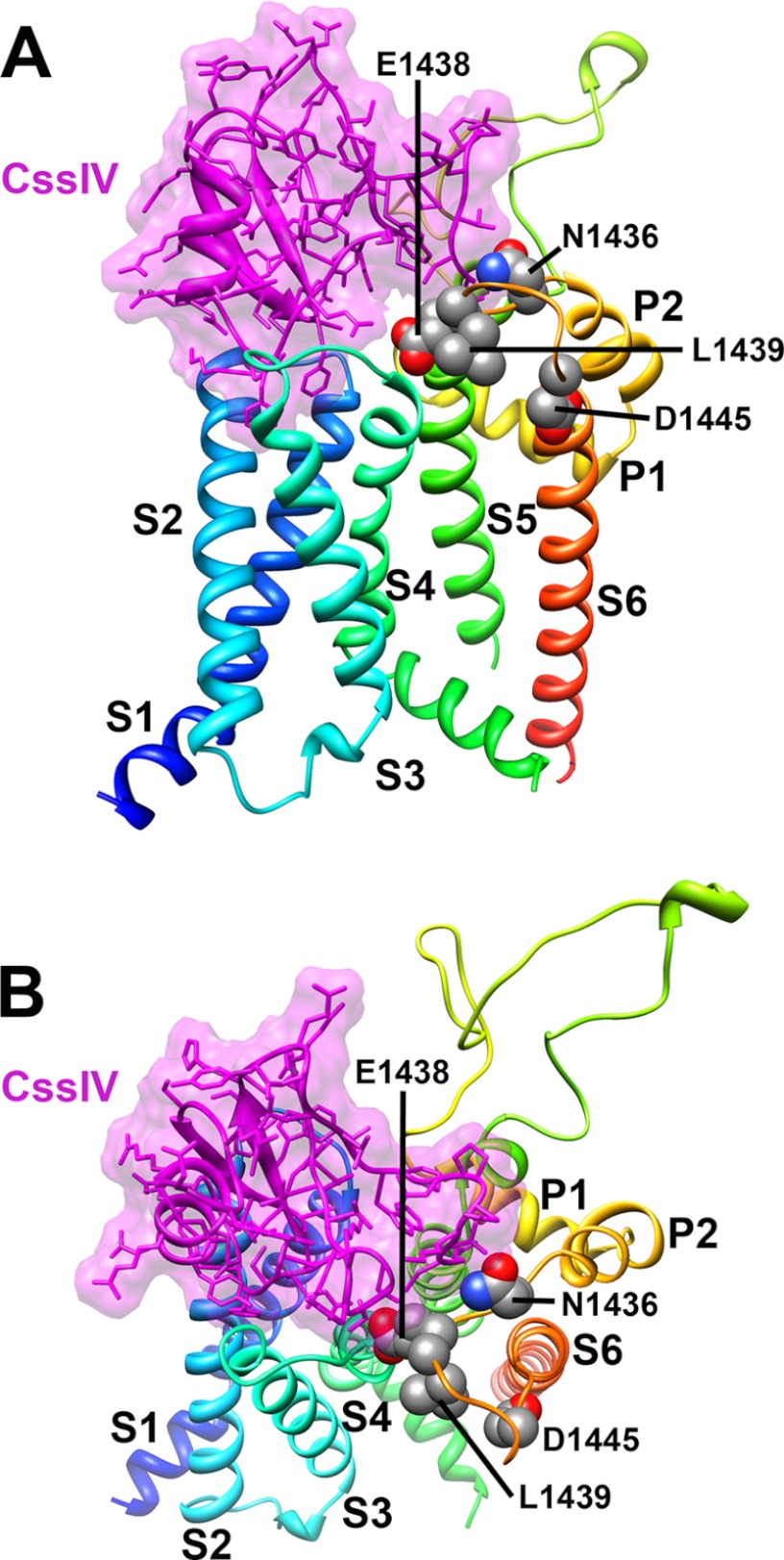

A Structural Model for the β-Scorpion Toxin-NaV Channel Complex

We used the Rosetta-membrane program to develop a molecular model of the CssIV toxin receptor site based on the crystal structure of the bacterial NaV channel NavAb (5). Because they are not present in the NavAb structure, the extracellular loops of the NaV1.2 channel were built ab initio using the kinematic loop protocol in the Rosetta-Membrane algorithm. The CssIV toxin was then docked in the putative receptor site formed by the cleft among the IIS1-S2, IIS3-S4, and IIISS2-S6 loops of the NaV1.2 channel as described under “Experimental Procedures” (Fig. 6). CssIV docks in the center of these three extracellular loops, and nearly all of the amino acid residues in the NaV1.2 channel that were most important for CssIV binding point toward the bound toxin. In IIISS2-S6, Asn1436, Glu1438, and Leu1439 are well positioned to interact with the bound CssIV toxin (Fig. 6). In contrast, Asp1445 is located on the opposite side of the IIISS2-S6 loop; therefore, mutations in this position likely affect toxin binding indirectly through interactions with Asn1436, Glu1438, and/or Leu1439 positioned across the IIISS2-S6 loop from Asp1445. It is also possible that the prediction of the fold of the IIISS2-S6 loop in our Rosetta model is inaccurate with respect to placement of Asp1445. However, models that allow Asn1436, Glu1438, Leu1439, and Asp1445 to all interact directly with bound CssIV would require distortions of the conformation of this region of the NaV channel that seem incompatible with the NavAb crystal structure. Therefore, we favor the conclusion that Asp1445 interacts with bound CssIV indirectly, perhaps by influencing the conformation of Asn1436, Glu1438, and Leu1439, which are just across the S5-S6 helical bundle from it.

FIGURE 6.

Structural model of β-scorpion CssIV binding to voltage-sensing module II and pore-forming module III of Nav1.2 channels. Segments S1 through S6 of the voltage-sensing and pore-forming modules colored individually and labeled. A, transmembrane view of the structural model with the voltage-sensing module segments S2, S4, and S6 on the front. Side chains of key residues in the pore-forming module III highlighted in this paper are shown in space filling representation and labeled. β-Scorpion CssIV is colored magenta with all other side chains shown in stick representation. B, view of the structural model from the extracellular side of the membrane. This figure was generated using Chimera (26).

As in our previous models of the CssIV-NaV channel complex (11), the wedge-shaped core domain of CssIV is bound between the two faces of the IIS1-S2 and IIS3-S4 loops. This orientation of CssIV places its amino acid residues whose side chains are most important for determining toxin affinity and efficacy in position to interact with these two extracellular loops. In contrast, the N- and C-terminal segments of CssIV point toward the IIISS2-S6 loop, but the only amino acid residue that is required for toxin binding in this part of the toxin, Trp58, interacts with the channel indirectly through its neighboring residues in this structural model. Thus, in this region of the toxin-receptor complex, the identity of the side chains of the amino acid residues on the NaV1.2 channel are important determinants of toxin binding and efficacy, but the overall shape of the CssIV toxin and its backbone carbonyls may be sufficient to sustain essentially normal interaction with the NaV channel, even when one amino acid residue has been mutated to alter the interactions of its side chain. The IIISS2-S6 loop of the NaV1.2 channel may provide a stable wall against which the toxin leans to exert force on the gating movements of the IIS3-S4 segment and thereby trap the voltage sensor in its activated conformation.

DISCUSSION

The Receptor Site for β-Scorpion Toxins Includes Amino Acid Residues in the IIISS2-S6 Loop

In our previous experiments, we mapped the molecular determinants of voltage-sensor trapping in domain II (8, 9, 11). These results demonstrated that both IIS1-S2 and IIS3-S4 loops are required for normal binding and voltage-sensor trapping by β-scorpion toxins, but the IIS3-S4 loop plays a dominant role as mutations in it have larger effects on binding affinity and unique effects on toxin efficacy (11). Based on the domain-swapped organization of the voltage-sensing module and pore module of KV and NaV channels revealed by x-ray crystallography (4, 5), we hypothesized that amino acid residues in the IIISS2-S6 loop would also play an important role in toxin binding and action. In the experiments described here, we have identified key amino acid residues in IIISS2-S6 that are critical for voltage-sensor trapping by CssIV. These data confirm the involvement of the IIISS2-S6 loop in voltage-sensor trapping by β-scorpion toxins. This conclusion is in agreement with our previous finding that transferring the entire IIISS2-S6 region of a β-scorpion toxin-insensitive Nav channel (Nav1.5) to a β-scorpion toxin-sensitive Nav channel (Nav1.2) markedly decreased the binding affinity of β-scorpion toxins in Nav channels (8). Similarly, our results agree with previous evidence that this segment of NaV channels determines the specificity for β-scorpion toxin interaction with different channel subtypes (12, 23).

Hydrophilic Pathway for Access to the CssIV Receptor Site

In the crystal structures of the Kv1.2-Kv2.1 chimera (4) and NavAb (5), several phospholipid molecules were observed tightly bound to each subunit of the channel proteins. However, no phospholipid molecules were observed in the extracellular aqueous cleft formed by the S1-S2 and S3-S4 loops of one subunit and the S5-S6 loop of the neighboring subunit. This observation is consistent with the conclusion that this surface is hydrophilic and water accessible. Therefore, it is likely that the large, highly charged β-scorpion toxins approach their receptor site on NaV channels from the extracellular medium, rather than from the membrane phase. This inference agrees with previous findings that CssIV toxin does not partition into the cell membrane (24).

Mutations in the IIISS2-S6 Region Can Strengthen or Weaken Voltage-sensor Trapping by CssIVE15A

Unlike the IIS1-S2 loop where only two mutants reduced the binding affinity of β-scorpion toxins, we identified both mutants that enhance and mutants that weaken voltage-sensor trapping in IIISS2-S6. The unidirectional effects of mutations in IIS1-S2 suggest that key residues in this loop form only positive interactions with CssIV, whereas the bidirectional mutational effects in IIISS2-S6 suggest that residues in IIISS2-S6 form both positive and negative interactions with toxin residues. These differential positive and negative binding interactions of amino acid residues may contribute to the efficacy of the bound toxin in voltage-sensor trapping.

Eight high-impact residues in IIS3-S4 were identified in our previous experiments (11). Five of those residues strongly reduced or even abolished voltage-sensor trapping, whereas the other three greatly enhanced voltage-sensor trapping. Similar to IIS3-S4 mutations, we identified two mutants in IIISS2-S6 that enhanced voltage-sensor trapping and three mutations at two residues markedly decreased voltage-sensor trapping. However, these high-impact residues are not in consecutive positions, in contrast to the hot spot of critical amino acid residues in the IIS3-S4 loop, and they have lesser effects on toxin action.

Nav1.2a/N1436G is a single residue chimera between Nav1.2a, on which β-toxins have strong voltage-sensor trapping action, and Nav1.5, on which β-toxins have very weak voltage-sensor trapping action (8). Interestingly, the N1436G mutation strongly enhanced voltage-sensor trapping by β-toxins. In this respect, it is similar to the N842R mutant in the IIS3-S4 loop, which is also a single residue chimera between rNav1.2a and hNav1.5 (8, 11). CssIV can trap the voltage-sensor of N842R at the resting membrane potential without a depolarizing prepulse, whereas a prepulse is required to observe increased voltage-sensor trapping with N1436G. CssIV has similar efficacy for voltage-sensor trapping Nav1.2a/N1436G as for WT, but it has a lower EC50 that indicates higher affinity binding for CssIV. In contrast, CssIV has a higher efficacy for voltage-sensor trapping of Nav1.2a/L1439A than WT, but binds to Nav1.2a/L1439A with an EC50 that is similar to WT. Therefore, mutation N1436G increased voltage-sensor trapping by CssIV via increasing its binding affinity to channels in the resting state, similar to N842R, V843A, and E844N described previously (11). In contrast, mutation L1439A increased voltage-sensor trapping via increasing the efficacy of voltage-sensor trapping by CssIV, primarily by slowing the reversal of voltage-sensor trapping. It is likely that Leu1439 is not required for toxin binding to channels in resting state, but stabilizes voltage-sensor trapping by enhancing CssIV binding to activated Nav channels.

IIISS2-S6 Plays a Secondary Role in Voltage Sensor Trapping

Our previous mapping of the key amino acid residues for CssIV binding to the IIS1-S2 and IIS3-S4 loops and our new data described here emphasize the dominant role of IIS3-S4 in determining β-scorpion toxin binding affinity and voltage-sensor trapping. Altogether, the results suggest that β-scorpion toxins interact with short segments of IIS1-S2 and IIISS2-S6 and a broader region of IIS3-S4. Evidently, these three distant regions of the primary structure of Nav channels are close to each other in the three-dimensional structure of NaV channels and form a single toxin-binding site that interacts with the bound toxin on three sides (8, 9, 11).

Our voltage sensor-trapping model predicts that β-scorpion toxins bind to their receptor site in the resting state of NaV channels and then, upon activation of the voltage sensor, trap the voltage sensor in domain II in an activated conformation. This effect causes the channel to activate at more negative membrane potentials because one of the voltage sensors is already activated. This three-step model predicts that the rate of toxin binding would be concentration-dependent, the activation of the voltage sensor would be voltage-dependent, and the trapping process would be both concentration- and voltage-independent. Our studies of the kinetics of onset and reversal of CssIV action agree with this model: toxin binding increases with concentration, as assessed from the maximal effect of CssIV, but the rate of voltage sensor trapping does not increase with concentration (Fig. 4). Unexpectedly, however, the rate of voltage sensor trapping for mutant N1436G decreased significantly with concentration (Fig. 4C). This effect is predicted by the voltage sensor-trapping model if bound CssIV both enhances the extent of voltage sensor trapping and also slows the transition into the activated or trapped states. This would occur if binding favors the trapped state but the bound toxin also presents a kinetic barrier to the conformation change into the activated or trapped states. Further development of our voltage sensor-trapping model and additional kinetic data under a wider range of conditions will be required to explore this idea further.

Spatial Arrangement of the Four Domains of NaV Channels

The crystal structures of KV1.2, KV1.2-KV2.1, and NavAb channels (3–5) have a domain-swapped arrangement of their voltage-sensing modules and pore modules in which the voltage sensor of one subunit interacts noncovalently with the pore domain of the neighboring subunit in clockwise order as viewed from the extracellular solution. Vertebrate NaV channels are composed of four homologous, but nonidentical domains in a single polypeptide. Our studies of amino acid residues required for toxin binding and voltage-sensor trapping in IIS1-S2, IIS3-S4, and IIISS2-S6 (see Refs. 8, 9, and 11, and this paper) show that the IIISS2-S6 loop is in close proximity to the voltage-sensing module of domain II. Therefore, the domain-swapped arrangement of bacterial NaV channels is present in mammalian NaV1.2 channels, and the four domains of mammalian Nav channels must also be arranged in a clockwise manner as viewed from the extracellular side.

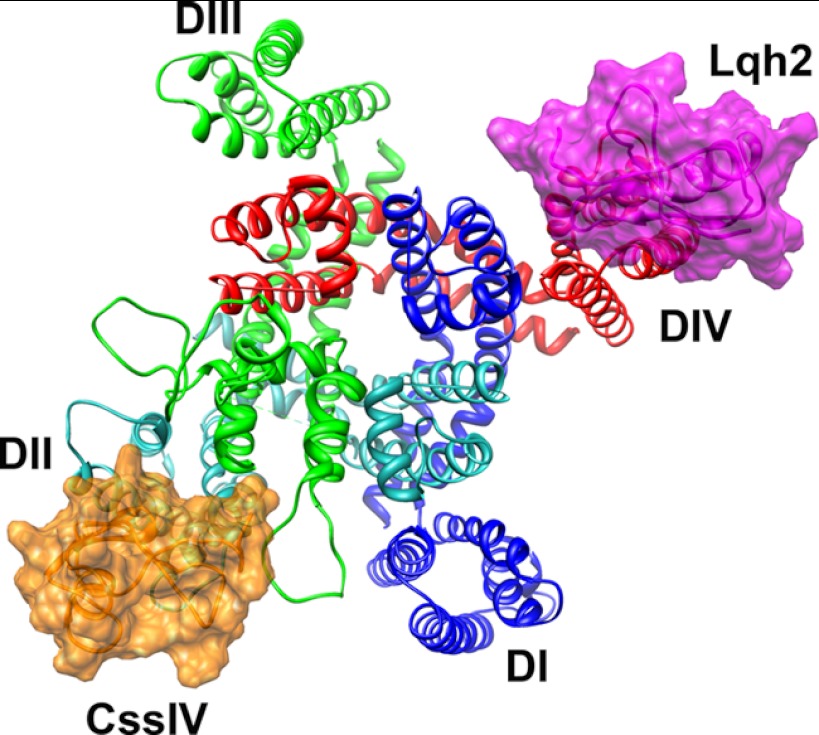

Single Receptor Sites for α- and β-Scorpion Toxins on NaV Channels

Vertebrate NaV channels have four homologous domains connected by large intracellular linkers (2). The short, highly conserved intracellular linker connecting domains III and IV serves as the fast inactivation gate, and α-scorpion toxins slow fast inactivation specifically. Identification of the amino acid residues in the IVS3-S4 loop that are required for high affinity binding of α-scorpion toxins led to the proposal that the voltage sensor in domain IV is primarily involved in fast inactivation (13). Consistent with that model, mutations of the gating charges in the IVS4 segment completely occlude the effects of α-scorpion toxins on gating current (27). Fluorescent labeling studies show that the four voltage sensors in the different domains are functionally specialized. The voltage sensors in domains I and II activate most rapidly and drive the rapid activation of Na+ conductance, whereas the voltage sensor in domain IV activates slowly with a time course similar to fast inactivation (28). Detailed mapping of the amino acid residues in the ISS2-S6, IVS1-S2, and IVS3-S4 segments that are required for high-affinity binding of α-scorpion toxins has led to the conclusion that these three extracellular loops form the receptor site for α-scorpion toxins with a similar conformation as we have proposed here for the receptor site for β-scorpion toxins (29). Moreover, single amino acid mutations in the IVS3-S4 loop reduce binding of α-scorpion toxins by nearly 100-fold (13, 29, 30). These results argue strongly that the high-affinity receptor site for α-scorpion toxins on the voltage sensor in domain IV is unique and cannot be substituted by the other three voltage sensors in NaV channels.

Our results on β-scorpion toxins also point to a single unique receptor site on NaV channels. The single amino acid mutation G845N in IIS3-S4 completely blocks voltage-sensor trapping by β-scorpion toxins (8), indicating that binding to the toxin receptor site in domain II is required for toxin action. Similarly, other mutations clustered near Gly845 have dramatic effects on toxin binding and efficacy (9, 11), indicating that toxin binding to the other three voltage-sensing modules cannot substitute for domain II. Thus, it seems most likely that both α- and β-scorpion toxins exert their toxic effects by interaction with a single receptor site on one voltage sensor.

Placing the α- and β-scorpion toxins onto a projection of their binding sites on NaV channels illustrates the pseudo 2-fold symmetric relationship of these two distinct scorpion toxin receptor sites, with the α-scorpion toxin receptor site formed by the voltage sensor in domain IV interacting with the pore module of domain I and the β-scorpion toxin receptor formed by the voltage sensor of domain II interacting with the pore domain of domain III (Fig. 7). Evidently, these two toxins bind to voltage-sensor domains having different physiological functions in vertebrate NaV channels and in that way impose different functional modifications, slowed inactivation for the α-scorpion toxins and negatively shifted activation for the β-scorpion toxins. These two functional effects are synergistic and act together to yield depolarization block of action potential conduction in nerve and muscle fibers. To our knowledge, this is the first example of two distinct toxins from a single type of venom that bind to pseudo-symmetric receptor sites and act synergistically to alter neuromuscular function and immobilize prey.

FIGURE 7.

Structural model of NavAb with both α- and β-scorpion toxins bound. View of the structural model from the extracellular side of the membrane. Four domains of a sodium channel colored individually and labeled. β-Scorpion CssIV (colored orange) and α-scorpion toxin (colored magenta) are shown in schematic and surface representation. This figure was generated using Chimera (26).

In contrast to this model of scorpion toxin action, homotetrameric KV channels bind hanatoxin and other cysteine-knot gating modifier toxins to receptor sites on all four voltage sensors (31). Transplanting voltage sensors among different KV channels or from NaV channels onto KV channels transfers toxin sensitivity, although the form and affinity of toxin action are often substantially altered (25, 32). These studies raised the possibility that gating-modifier toxins in general are promiscuous and can alter the function of any voltage sensor. Our studies show that this is not the case for scorpion toxins acting on four-domain mammalian NaV channels. The α- and β-scorpion toxins each have a specific receptor site on NaV channels, which are related by a pseudo 2-fold axis of symmetry in the channel structure. The high-affinity, synergistic actions of these two toxin types enable potent paralysis of prey by scorpion venoms. Evidently, evolution of the scorpion toxins has allowed them to act selectively yet synergistically on two different vertebrate NaV voltage sensors and thereby enhance the potency of venoms containing both toxin types.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Research Grants U01 NS058039 (to W. A. C. and M. G.) and R01NS15751 (to W. A. C.), and a grant from the Binational Agricultural Research and Development Fund of the United States and Israel (to M. G. and W. A. C.).

- CssIV

- IV of Centruroides suffusus suffusus

- IVST

- voltage-sensor trapping current.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hille B. (2001) Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes, 3rd Ed., Sinauer Associates Inc., Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 2. Catterall W. A. (2000) From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms. The structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron 26, 13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Long S. B., Campbell E. B., Mackinnon R. (2005) Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K+ channel. Science 309, 897–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Long S. B., Tao X., Campbell E. B., MacKinnon R. (2007) Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature 450, 376–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Payandeh J., Scheuer T., Zheng N., Catterall W. A. (2011) The crystal structure of a voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature 475, 353–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Catterall W. A. (1980) Neurotoxins that act on voltage-sensitive sodium channels in excitable membranes. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 20, 15–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Catterall W. A., Cestèle S., Yarov-Yarovoy V., Yu F. H., Konoki K., Scheuer T. (2007) Voltage-gated ion channels and gating modifier toxins. Toxicon 49, 124–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cestèle S., Qu Y., Rogers J. C., Rochat H., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (1998) Voltage-sensor trapping. Enhanced activation of sodium channels by β-scorpion toxin bound to the S3-S4 loop in domain II. Neuron 21, 919–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cestèle S., Yarov-Yarovoy V., Qu Y., Sampieri F., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (2006) Structure and function of the voltage sensor of sodium channels probed by a β-scorpion toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21332–21344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karbat I., Ilan N., Zhang J. Z., Cohen L., Kahn R., Benveniste M., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A., Gordon D., Gurevitz M. (2010) Partial agonist and antagonist activities of a mutant scorpion β-toxin on sodium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 30531–30538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang J. Z., Yarov-Yarovoy V., Scheuer T., Karbat I., Cohen L., Gordon D., Gurevitz M., Catterall W. A. (2011) Structure-function map of the receptor site for β-scorpion toxins in domain II of voltage-gated sodium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 33641–33651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leipold E., Hansel A., Borges A., Heinemann S. H. (2006) Subtype specificity of scorpion β-toxin Tz1 interaction with voltage-gated sodium channels is determined by the pore loop of domain 3. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 340–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rogers J. C., Qu Y., Tanada T. N., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (1996) Molecular determinants of high affinity binding of α-scorpion toxin and sea anemone toxin in the S3-S4 extracellular loop in domain IV of the Na+ channel a subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 15950–15962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yarov-Yarovoy V., Baker D., Catterall W. A. (2006) Voltage sensor conformations in the open and closed states in ROSETTA structural models of K+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7292–7297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yarov-Yarovoy V., Schonbrun J., Baker D. (2006) Multipass membrane protein structure prediction using Rosetta. Proteins 62, 1010–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barth P., Schonbrun J., Baker D. (2007) Toward high-resolution prediction and design of transmembrane helical protein structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15682–15687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jeanmougin F., Thompson J. D., Gouy M., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1998) Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 403–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang C., Bradley P., Baker D. (2007) Protein-protein docking with backbone flexibility. J. Mol. Biol. 373, 503–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bonneau R., Strauss C. E., Rohl C. A., Chivian D., Bradley P., Malmström L., Robertson T., Baker D. (2002) De novo prediction of three-dimensional structures for major protein families. J. Mol. Biol. 322, 65–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mandell D. J., Coutsias E. A., Kortemme T. (2009) Sub-angstrom accuracy in protein loop reconstruction by robotics-inspired conformational sampling. Nat. Methods 6, 551–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cohen L., Karbat I., Gilles N., Ilan N., Benveniste M., Gordon D., Gurevitz M. (2005) Common features in the functional surface of scorpion β-toxins and elements that confer specificity for insect and mammalian voltage-gated sodium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 5045–5053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rohl C. A., Strauss C. E., Misura K. M., Baker D. (2004) Protein structure prediction using Rosetta. Methods Enzymol. 383, 66–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gurevitz M., Karbat I., Cohen L., Ilan N., Kahn R., Turkov M., Stankiewicz M., Stühmer W., Dong K., Gordon D. (2007) The insecticidal potential of scorpion β-toxins. Toxicon 49, 473–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cohen L., Gilles N., Karbat I., Ilan N., Gordon D., Gurevitz M. (2006) Direct evidence that receptor site-4 of sodium channel gating modifiers is not dipped in the phospholipid bilayer of neuronal membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 20673–20679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bosmans F., Swartz K. J. (2010) Targeting voltage sensors in sodium channels with spider toxins. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 31, 175–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF chimera, a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sheets M. F., Kyle J. W., Kallen R. G., Hanck D. A. (1999) The Na channel voltage sensor associated with inactivation is localized to the external charged residues of domain IV, S4. Biophys. J. 77, 747–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chanda B., Bezanilla F. (2002) Tracking voltage-dependent conformational changes in skeletal muscle sodium channel during activation. J. Gen. Physiol. 120, 629–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang J., Yarov-Yarovoy V., Kahn R., Gordon D., Gurevitz M., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (2011) Mapping the receptor site for α-scorpion toxins on a Na+ channel voltage sensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 15426–15431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gur M., Kahn R., Karbat I., Regev N., Wang J., Catterall W. A., Gordon D., Gurevitz M. (2011) Elucidation of the molecular basis of selective recognition uncovers the interaction site for the core domain of scorpion α-toxins on sodium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 35209–35217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li-Smerin Y., Swartz K. J. (2000) Localization and molecular determinants of the hanatoxin receptors on the voltage-sensing domains of a K+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 115, 673–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bosmans F., Martin-Eauclaire M. F., Swartz K. J. (2008) Deconstructing voltage sensor function and pharmacology in sodium channels. Nature 456, 202–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]