Abstract

The purpose of this review is to provide a summary of studies on the effectiveness nutrition education interventions used by college students. Electronic databases such as Medline, Science Direct, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), and Google Scholar were explored for articles that involved nutrition education interventions for college students and that were published between 1990 and 2011. Fourteen studies, which involved a total of 1668 college students as respondents, were identified and met the inclusion criteria. The results showed that there were 3 major forms of nutrition education interventions: web-based education, lectures, and supplement provisions. Dietary intake measures were used in almost all studies and were primarily collected with food records, recall, food frequency questionnaires, and dietary habit questionnaires. The outcome measures varied among the studies, with indicators such as consumption of food, nutrition knowledge, dietary habits, physical activity, and quality of life. Methodological issues were also identified. In general, college students experienced significant changes in their dietary habits after the interventions were employed. The highlighted methodological issues should be considered to improve the quality of similar research in future.

Keywords: dietary habits, education, intervention studies, nutrition, programme effectiveness, young adult

Introduction

College students between the ages of 18 and 24 years gain new experiences and personal freedom as well as develop a sense of identity as they ascend from adolescence to adulthood (1). Unfortunately, during this phase, the tendency to engage in unhealthy dieting, meal skipping, and fast food consumption is rather common. Minimal physical activity is also a norm (1). Poor eating habits and limited physical activity can likely increase the risk for osteoporosis, obesity, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, and cancer later in life (1). Such an unhealthy lifestyle is further linked to health-related quality of life (HRQoL), which is related to an individual’s nutritional status (2). All of these associations suggest that it is important to establish good eating habits at an early age (3).

Nutrition education is widely used for a range of population groups as a medium to deliver healthy diet and nutrition information; however, this type of intervention is still rarely implemented for college students. While there are various modes of nutrition education interventions, their effectiveness on eating habits remains unclear. This review thus intends to describe the impact of different nutrition education interventions on the dietary habits of college students by reviewing previous studies from developed nations.

Materials and Methods

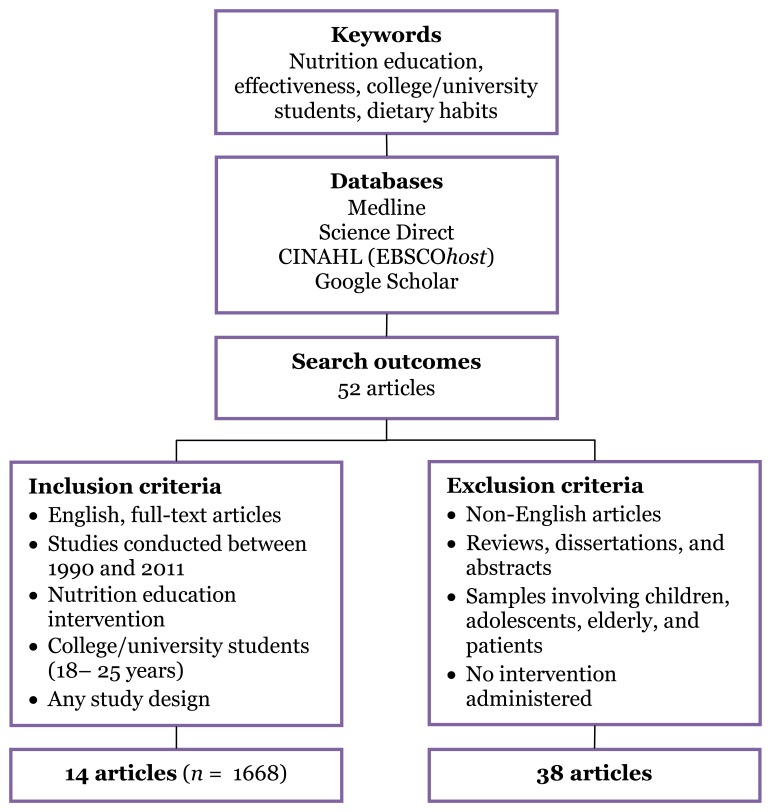

Articles were identified through relevant databases (i.e., Medline, Science Direct, CINAHL [EBSCOhost], and Google Scholar) from 1990 until 2011 using the following keywords: nutrition education, effectiveness, college/university students, and dietary habits.

The keyword-based screening strategy alone generated 52 articles, but only 14 met the specified inclusion criteria: 1) the participants were 18 to 25 years (college/university students), 2) the study design was cross-sectional, exploratory, longitudinal, or randomised controlled trials (RCT), and 3) they were available in full-text form. Studies published in languages other than English, reviews, and abstracts were excluded. The included studies were subsequently reviewed based on the study design, year, country, sample size, duration, type of nutrition intervention, and outcome measures. The selection method is summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

The process of article selection

Results

The 14 studies included 1668 participants (Table 1). These studies involved more female college students (n = 1113) than males (n = 555) and that many of the studies were conducted in the United States of America. Only 2 studies were conducted elsewhere: in Korea and in Israel.

Table 1:

Studies using nutrition education as interventions for college students

| 1. Ha and Caine-Bish, 2011 (20) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States | An interactive, introductory nutrition course focusing on disease prevention |

|

|

| Design | |||

| Longitudinal | |||

| Duration | |||

| 15 weeks | |||

| Sample | |||

| 80 college students | |||

| 2. Gow et al., 2010 (21) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States | An online intervention to

reduce adult obesity rates with 4 modalities:

|

|

|

| Design | |||

| RCT | |||

| Duration | |||

| 3 months | |||

| Sample | |||

| 159 first year college students (CG = 40, OI = 40, FI = 39, CI = 40) | |||

| 3. Poddar et al., 2010 (22) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States | A web-based intervention using an online course system (email messages, posted information, and behaviour checklists with tailored feedback) |

|

|

| Design | |||

| Experimental | |||

| Duration | |||

| 5 weeks | |||

| Sample | |||

| 294 college students (IG = 148, CG = 146) | |||

| 4. Ha and Caine-Bish, 2009 (9) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States | Class lectures covered nutrition knowledge related to prevention of chronic diseases, healthful dietary choices, increasing fruits and vegetables, promoting active lifestyles, and interactive hands-on activities |

|

|

| Design | |||

| Longitudinal | |||

| Duration | |||

| 15 weeks | |||

| Sample | |||

| 80 college students | |||

| 5. Ha et al., 2009 (8) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States | A class-based nutrition intervention combined with traditional lectures, interactive hands-on activities, and dietary feedback |

|

|

| Design | |||

| Longitudinal | |||

| Duration | |||

| 15 weeks | |||

| Sample | |||

| 80 college students | |||

| 6. White et al., 2009 (3) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States |

|

|

|

| Design | |||

| Randomised and longitudinal | |||

| Duration | |||

| 3 years | |||

| Sample | |||

| 144 college students | |||

| 7. You et al., 2009 (4) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| Korea | Nutrition education (diet therapy, exercise, and behavioural modification) and supplementation (sea tangle) |

|

|

| Design | |||

| Longitudinal | |||

| Duration | |||

| 8 weeks | |||

| Sample | |||

| 22 Korean female college students | |||

| 8. Franko et al., 2008 (1) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States | MyStudentBody.com- Nutrition (MSB-N) Internet-based nutrition and physical activity education program |

|

|

| Design | |||

| RCT | |||

| Duration | |||

| 6 months | |||

| Sample | |||

| College students from 6 universities in the States (Experimental I = 139, Experimental II = 148) | |||

| 9. Endevelt et al., 2006 (11) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| Israel | Four topics:

|

|

|

| Design | |||

| Cross-sectional | |||

| Duration | |||

| 10-hour nutrition workshop (2 days) in 2003 and 2004 | |||

| Sample | |||

| 122 second-year medical students (1st and 2nd class) | |||

| 10. Abood et al., 2004 (23) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States | Focused on nutrition

knowledge, self-efficacy in making healthful dietary choices, and

dietary practices to demonstrate treatment effect

|

|

|

| Design | |||

| Longitudinal | |||

| Duration | |||

| 8 weeks | |||

| Sample | |||

| 30 college female athletes (IG = 15, CG = 15) | |||

| 11. Levy and Auld, 2004 (24) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States | Demonstration versus hands-on cooking classes |

|

|

| Design | |||

| Exploratory | |||

| Duration | |||

| 3 months | |||

| Sample | |||

| 65 first-semester college students (IG = 33, CG = 32) | |||

| 12. Matvienko et al., 2001 (25) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States | • College course composed of both lectures and laboratory exercises |

|

|

| Design | |||

| RCT | |||

| Duration | |||

| 16 months | |||

| Sample | |||

| 40 first-year female college students (IG = 21, CG = 19) | |||

| 13. Winzelberg et al., 2000 (26) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States | Internet-based, computer-assisted health education programme |

|

|

| Design | |||

| RCT | |||

| Duration | |||

| 3 months | |||

| Sample | |||

| 43 female students (IG = 23, CG = 20) | |||

| 14. Aaron et al., 1995 (27) | |||

| Country | Intervention | Result/conclusion(s) | Comment(s) |

| United States | Provision of nutrient intake information at lunch at college |

|

|

| Design | |||

| Experimental | |||

| Duration | |||

| 2 weeks | |||

| Sample | |||

| 90 college students (IG = 65, CG = 25) | |||

Abbreviation: RCT = randomised controlled trial, IG = intervention group, CG = control group

Only 1 study was cross-sectional by design, 4 were RCTs, and 9 were longitudinal studies. Sample sizes varied greatly across the studies, ranging from 22 to 294 participants. Nine out of 14 studies reported the questionnaire validity and reliability. Survey feasibility was reported in 1 study, but the validity of other self-report measures was not indicated. The overall study duration ranged from 2 days to 3 years.

The modes of intervention also differed among the studies (Table 1). As the delivery mode, 3 studies used web-based education, 1 study provided dietary supplements, and the other studies used educational lectures. The methods of lecture differed: some studies used traditional lectures combined with handson activities, while others utilised debates on nutritional treatments and cooking classes. Only 2 studies employed social cognitive theory (SCT) as a theory-based intervention. In another study, sea tangle (20 g/day) was distributed as a supplement to a combination of diet therapy, exercise, and behavioural modification (4).

To measure dietary changes before and after the intervention, most studies used the food frequency questionnaire, 3-day dietary record, and 24-hour food recall questionnaire (Table 2). Data were analysed and presented as nutrient intake. In addition, dietary habit questionnaires were used, and the results showed that the total score significantly increased after an 8-week body weight control programme (4).

Table 2:

Measurement instruments and corresponding outcomes

| No. | Authors | Measurement instrument | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ha and Caine-Bish (20) |

|

|

| 2. | Gow et al. (21) |

|

|

| 3. | Poddar et al. (22) |

|

|

| 4. | Ha and Caine-Bish (9) |

|

|

| 5. | Ha et al. (8) |

|

|

| 6. | White et al. (3) | Questionnaires based on the following

health behaviours:

|

|

| 7. | You et al. (4) |

|

|

| 8. | Franko et al. (1) |

|

|

| 9. | Endevelt et al. (11) |

|

|

| 10. | Abood et al. (23) |

|

|

| 11. | Levy and Auld (24) |

|

|

| 12. | Matvienko et al. (25) |

|

|

| 13. | Winzelberg et al. (26) |

|

|

| 14. | Aaron et al. (27) |

|

|

Only 1 study highlighted HRQoL issues in relation to nutrition education, which was assessed using the generic Short Form-36 (SF-36) (4). However, SF-36 is an instrument that has been widely used for population-based HRQoL rating (5).

Discussion

This brief review compiles evidence on the effectiveness of nutrition education interventions that have been used for college/university students in developed countries. Methodological issues, types of nutrition education interventions, dietary habits, related outcomes, and suggestions for future investigations are highlighted.

Because females out-numbered the males with a ratio of 2:1 across all studies, the overall sample composition may be imbalanced. This higher rate of female participation may be related to the increasing proportion of women in tertiary institutions (6). A recent report in Malaysia indicates that the proportion of female to male students has increased to a current ratio of 65:35 (7), and the same trend is believed to occur in other countries. Regarding attitudes toward nutrition, females exceeded their male counterparts. Similar findings have been previously discovered, such that females reported more positive attitudes towards healthy eating and greater health-consciousness than males did (8,9). These results imply that female students are highly motivated and are more interested in their health, body weight, and body image than male students are. Furthermore, the transition from home to college has often been identified to be a potentially critical period for weight gain among young adults, and in comparison to men, women have especially been eager to change their body shape and weight to conform with current fashion trends (10). Consequently, female students are more likely to be respondents in weight- and body shape–related programmes involving nutrition education interventions.

Regarding the methodological issues, most techniques seem to require several improvements. The common usage of cross-sectional design (11) in most investigations has its drawbacks, such that group differences can only be gauged at one time point and temporal changes could not be assessed. This methodological challenge may prevent experimentally conclusive and sustainable evidence. The sample sizes in several studies were also rather small, ranging from 22 to 43 participants. Thus, the findings may be limited and may lack generalisability because the data could only be analysed using less powerful statistical techniques and the study samples were likely not representative of the more general population . In addition, the reliability and validity of the assessment tools were not comprehensively reported, which is a methodological weakness because these indicators are essential for determining the effectiveness of the interventions (12).

A variety of outcomes have been reported across the interventions studied. Encouraging and positive results with improved health outcomes have been demonstrated in most studies. Nonetheless, more than half of the studies have not reported any preliminary evaluations of newly developed interventions. Such initial evaluations are crucial because they can facilitate subsequent modifications to ensure that an intervention is feasible and acceptable for use in an actual study (12). As a result, later experimental investigations may be less exposed to methodological flaws and may thus provide stronger outcomes.

The results for dietary habits showed that the combination of nutrition education and supplement provision was significantly beneficial in improving body composition, dietary habits, daily nutrient intake, and quality of life in a sample of Korean students (4). Supplements have been commonly administered to either healthy or unhealthy Korean populations (13). Furthermore, a few studies have also reported changes in dietary habits after interventions involving educational lectures as a nutrition improvement tool. For instance, Ha and Caine-Bish (9) have successfully showed an increased consumption of fruits and vegetables after nutrition interventions. Because dietary habits could worsen during university years, any undesirable dietary norm should be addressed at earlier ages and preferably through individuals’ routine learning environments (9). Hence, nutrition education is a well-suited technique to improve both students’ dietary habits and their awareness of overall health.

HRQoL data have been universally used to assess populations with illness and disability, to identify health disparities and needs and to monitor health changes over time (5). HRQoL refers to an individual’s satisfaction or happiness with the domains of life that are affected by health (5). Based on our review, HRQoL as related to dietary habits was not directly or extensively studied among college students. Because HRQoL represents a vital and holistic parameter for population healthcare needs, future investigations should include nutrition-related HRQoL as an outcome measure.

Additionally, research should focus on the development of nutrition education tools, which are not only effective but also interesting and practical for the current generation of students. For example, the effectiveness of the short messaging system has been demonstrated in smokers, diabetics, and bulimia nervosa patients (14). Another recommendation is to target nutrition education for first-year university students, who may still be adjusting to the collegiate environment and experiencing independence in life for the first time.

Several drawbacks of this review deserve attention. In particular, our limited accessible online databases generated only 14 articles that met the inclusion criteria from Medline, Science Direct, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), and Google Scholar. With a small number of reported RCTs and lacking studies from developing countries, we could not provide a more comprehensive, potentially less-biased review. We did find 5 investigations from developing countries, which included Malaysia and Indonesia, but they unfortunately did not conform to the aims of our review. These studies were either focused on primary school children (15–17) or the elderly (18,19), which did not meet our main target sample of college/university students. Future studies should also enrol larger samples, with the provision of sample size calculations, and a more balanced gender representation. With the majority of respondents being women across the studies, we acknowledge that this review may be biased toward female nutritional habits. Because publications in languages other than English were excluded, additional information from these studies could complement the existing research findings.

Conclusion

Despite several methodological limitations, we found that significant and beneficial changes in dietary habits have been found for college students after the implementation of nutrition interventions via various techniques. In particular, nutrition education and its combination with supplement provision appeared to be the best methods for enhancing students’ eating habits and promoting healthier diets and lifestyles. Nonetheless, these findings are more representative of the female populations in developed nations, and we suggest that further trials of similar nature, with improved methodology and in less-developed countries, are highly important.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design, critical revision of the article: LPP

Collection, assembly, analysis, and interpretation of the data, drafting of the article: WPEWD

Final approval of the article: LPP, WPEWD

References

- 1.Franko DL, Cousineau TM, Trant M, Green TC, Rancourt D, Thompson D, et al. Motivation, self-efficacy, physical activity and nutrition in college students: Randomized controlled trial of an internet-based education program. Prev Med. 2008;47(4):369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell KL, Ash S, Bauer JD. The impact of nutrition intervention on quality of life in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients. Clin Nutr. 2008;27(4):537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White S, Park YS, Isreal T, Cordero ED. Longitudinal evaluation of peer health education on a college campus: Impact on health behaviors. J Am Coll Health. 2009;57(5):497–505. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.5.497-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.You JS, Sung MJ, Chang KJ. Evaluation of 8-week body weight control program including sea tangle (Laminaria japonica) supplementation in Korean female college students. Nutr Res Prac. 2009;3(4):307–314. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2009.3.4.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware JE Jr, Gandek B. Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):903–912. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldin C, Katz LF, Kuziemko I. The homecoming of American college women: The reversal of the college gender gap. J Econ Perspect. 2006;20(4):133–156. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapoor C, Au E. University gender gap. New Straits Times. 2011 Sep 8; Main:1 (col. 1)

- 8.Ha EJ, Caine-Bish N, Holloman C, Lowry-Gordon K. Evaluation of effectiveness of class-based nutrition intervention on changes in soft drink and milk consumption among young adults. J Nutr. 2009;8:50. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-8-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ha EJ, Caine-Bish N. Effect of nutrition intervention using a general nutrition course for promoting fruit and vegetable consumption among college students. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41(2):103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grogan S. Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Routledge Taylor and Francis Group; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Endevelt R, Shahar DR, Henkin Y. Development and implementation of a nutrition education program for medical students: A new challenge. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2006;19(3):321–330. doi: 10.1080/13576280600938232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Contento IR, Randell JS, Basch CE. Review and analysis of evaluation measures used in nutrition education intervention research. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34(1):2–25. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ock SM, Hwang SS, Lee JS, Song CH, Ock CM. Dietary supplement use by South Korean adults: Data from the national complementary and alternative medicine use survey (NCAMUS) in 2006. Nutr Res Prac. 2010;4(1):69–74. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2010.4.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishna S, Boren SA. Diabetes self-management care via cell phone: A systematic review. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2(3):509–517. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zalilah MS, Siti Sabariah B, Norlijah O, Normah H, Maznah I, Zubaidah J, et al. Nutrition education intervention improves nutrition knowledge, attitude and practices of primary school children: A pilot study. Int Elect J Health Educ. 2008;11:119–132. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatik M, Endy PP, Toto S. Effect of nutrition education for mother on the food consumption and nutrion status of the children that infected by primary tubercolusis at Dokter Kariadi Hospital Semarang. Indones J Clin Nutr. 2004;1(2) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zulkarnaini, Toto C, Untung SW. Pengaruh pendidikan gizi pada murid sekolah dasar terhadap peningkatan pengetahuan, sikap dan perilaku ibu keluarga mandiri sadar gizi di Kabupaten Indragiri Hilir. Indones J Clin Nutr. 2006;3(1) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaitun Y, Low TS. Assessment of nutrition education needs among a sample of elderly Chinese in an urban area. Mal J Nutr. 1995;1:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siti Nur Asyura A, Suzana A, Suriah AR, Noor Aini MY, Zaitun Y, Fatimah A, et al. Proceedings of the 7th National Symposium on Health Sciences. 2008 Jun 18—19. Kuala Lumpur (MY): Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia; 2008. Effectiveness of an intervention programme for promotion of healthy ageing and risk reduction of chronic diseases; pp. 172–177. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ha EJ, Caine-Bish N. Interactive introductory nutrition course focusing on disease prevention increased whole-grain consumption by college students. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43(4):263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gow RW, Trace SE, Mazzeo SE. Preventing weight gain in first year college students: An online intervention to prevent the “freshmen fifteen”. Eat Behav. 2010;11(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poddar KH, Hosig KW, Anderson ES, Nickols-Richardson SM, Duncan SE. Web-based nutrition education intervention improves self-efficacy and selfregulation related to increased dairy intake in college students. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(11):1723–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abood DA, Black DR, Birnbaum RD. Nutrition education intervention for college female athletes. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2004;36(3):135–137. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy J, Auld G. Cooking classes outperform cooking demonstrations for college sophomores. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2004;36(4):197–203. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matvienko O, Lewis DS, Schafer E. A college nutrition science course as an intervention to prevent weight gain in female college freshman. J Nutr Educ. 2001;33(2):95–101. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winzelberg AJ, Eppstein D, Eldredge KL, Wilfley D, Dasmahapatra R, Dev P, et al. Effectiveness of an internet-based program for reducing risk factors for eating disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(2):346–350. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aaron JI, Evans RE, Mela DJ. Parodoxical effect of a nutrition labeling scheme in a student cafeteria. Nutr Res. 1995;15(9):1251–1261. [Google Scholar]