Background: Blimp1 is required for development and maintenance of homeostasis in various tissues.

Results: Conditional Blimp1 inactivation in adult mice promoted decreased osteoclast differentiation and increased bone mass without severe defects in other tissues.

Conclusion: Blimp1 inhibition increases bone mass.

Significance: Blimp1 is a new molecular target for preventing pathological bone loss.

Keywords: Bone, Genetics, Osteoclast, Osteoporosis, Transcription Repressor

Abstract

Bone resorption, which is regulated by osteoclasts, is excessively activated in bone destructive diseases such as osteoporosis. Thus, controlling osteoclasts would be an effective strategy to prevent pathological bone loss. Although several transcription factors that regulate osteoclast differentiation and function could serve as molecular targets to inhibit osteoclast formation, those factors have not yet been characterized using a loss of function approach in adults. Here we report such a study showing that inactivation of B-lymphocyte induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp1) in adult mice increases bone mass by suppressing osteoclast formation. Using an ex vivo assay, we show that osteoclast differentiation is significantly inhibited by Blimp1 inactivation at an early stage of osteoclastogenesis. Conditional inactivation of Blimp1 inhibited osteoclast formation and increased bone mass in both male and female adult mice. Bone resorption parameters were significantly reduced by Blimp1 inactivation in vivo. Blimp1 reportedly regulates immune cell differentiation and function, but we detected no immune cell failure following Blimp1 inactivation. These data suggest that Blimp1 is a potential target to promote increased bone mass and prevent osteoclastogenesis.

Introduction

Osteoclasts mediate bone resorption and thereby play an essential role in maintaining bone mass and homeostasis (1). Dysregulation of osteoclast differentiation or function causes an imbalance in bone formation and resorption, leading to pathogenic conditions such as osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, lytic bone metastases, or Paget's bone disease (2). Since osteoclasts could potentially be targeted therapeutically to treat skeletal diseases, their differentiation and function are required to understand thorough molecular analysis. Osteoclasts originate from monocyte/macrophage precursors that undergo differentiation in response to signaling through the receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL2; 3). RANKL induces osteoclast differentiation by activating the nuclear factor of activated T cells, cytoplasmic, calcineurin- dependent 1 (Nfatc1), the essential transcription factor required for osteoclastogenesis (4). NFATc1 transactivates “osteoclastic” genes encoding factors such as dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (Dc-stamp), which facilitates fusion and multinucleation, cathepsin K (Ctsk), which promotes bone matrix degradation, and Nfatc1 itself, to drive differentiation in an auto-amplification manner (5, 6).

Recently, we identified a novel mechanism that controls osteoclast differentiation via transcriptional repressors (7). We found that B-cell lymphoma 6 (Bcl6), originally identified in a translocation junction in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (8), was required to maintain osteoclast progenitors in an undifferentiated state by repressing osteoclastic genes such as Nfatc1. B-lymphocyte induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp1) was induced by RANKL stimulation and suppressed Bcl6 expression by binding to the Bcl6 promoter. Furthermore, we also found that osteoclast-specific Blimp1-deficient mice exhibited impaired osteoclast differentiation and increased bone mass due to Bcl6 accumulation in osteoclast progenitors (7). These findings suggest that Blimp1 promotes bone resorption by eliminating Bcl6, a negative regulator of osteoclastogenesis. Transcriptome analysis of osteoclastogenesis also suggests that Blimp1 serves as a transcriptional repressor to block anti-osteoclastogenic genes (9).

Blimp1 is reportedly essential for specification and maintenance of primordial germ cells through silencing of somatic programs (10). Blimp1 is also known to function in terminal differentiation of immunoglobulin-secreting plasma cells by repressing mature B cell genes, maintenance of T cell homeostasis by regulating the differentiation of naïve T cells into subpopulation with specific functions such as effecter T cells, and regulating maturation and homeostasis of natural killer cells (11–14). Blimp1 is also highly expressed in the intestinal epithelium until the suckling to weaning transition and controls epithelial maturation in mice (15, 16). Several inactivation models have been applied to investigate Blimp1 function (7, 9, 11–17); however, the inducible inactivation model at an adult stage has not well been documented. Inactivation of Blimp1 at an adult stage would reveal whether it represents an appropriate target to develop Blimp1-inhibiting reagents to treat adult diseases such as osteoporosis. Conditional inactivation using an inducible Cre-loxP system could serve to mimic administration of the Blimp1 inhibitor.

In this study, we established an inducible inactivation model in which Blimp1 is systemically knocked out at an adult stage by crossing mice harboring Mx1Cre transgene and loxP-flanked Blimp1 alleles. We report that conditional inactivation of Blimp1 promoted increased bone mass and decreased osteoclast formation in the absence of immune system defects. Our observations suggest that Blimp1 could be targeted as a strategy to increase bone mass.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

The inducible conditional Blimp1 knock-out mice (Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl) were generated by crossing Blimp1fl/fl mice carrying loxP-flanked Blimp1 alleles and Mx1Cre transgenic mice. Eight-week-old Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice and Blimp1fl/fl littermate control mice received a total of three intraperitoneal injections of 250 μg of pI-pC (Sigma-Aldrich) administered every 3 days to induce Cre activation. After 5 weeks, animals were sacrificed, and bone, spleen, bone marrow, and serum were collected and analyzed. Osteoblast-specific Blimp1 knock-out mice were generated by crossing Blimp1fl/fl mice with Col1a1Cre transgenic mice (18). Animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in animal facilities certified by Keio University School of Medicine animal care committee. Animal protocols were also approved by the committee.

Cell Culture

Bone marrow cells isolated from femurs and tibias were cultured for 72 h in αMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, JRH Biosciences Lenexa, KS) and GlutaMax (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with M-CSF (50 ng/ml, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Tokyo, Japan). Adherent cells were collected and 1 × 105 cells were cultured with M-CSF (50 ng/ml) and recombinant soluble RANKL (25 ng/ml, PeproTech Ltd., Rocky Hill, NJ) in the presence or absence of recombinant interferon β (IFN, 100 units/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) in 96-well culture plates. Osteoclastogenesis was evaluated by May-Grünwald Giemsa and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining (5, 19). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts were prepared and cultured with bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP2) to induce osteoblast differentiation as described (20). Mouse primary osteoblasts prepared from newborn calvaria were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid, and 5 mm β-glycerophosphate in the presence or absence of BMP2 (200 ng/ml) and IFN (100 units/ml).

ELISA

Serum levels of C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTx) and IgG were measured by RatLaps EIA (Immunodiagnostics Systems Ltd.) and Mouse IgG EIA (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Shiga, Japan), respectively, following the manufacturers' instructions.

Quantitative PCR Analysis

Total RNAs were isolated from cells and tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and cDNA synthesis was undertaken using oligo(dT) primer and reverse transcriptase (Wako Pure Chemicals Industries, Osaka, Japan). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using SYBR Premix ExTaq II reagent and the DICE Thermal cycler (Takara Bio Inc.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were matched to a standard curve generated by amplifying serially diluted products using the same PCR reactions. β-Actin (Actb) expression served as an internal control. Primer sequences were as follows: Actb-forward: 5′-TGAGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC-3′; Actb-reverse: 5′-AAGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAAAGAG-3′; Bcl6-forward: 5′-AGACGCACAGTGACAAACCATACA-3′; Bcl6-reverse: 5′-GCTCCACAAATGTTACAGCGATAGG-3′; Blimp1-forward: 5′-TTCTTGTGTGGTATTGTCGGGACTT-3′; Blimp1-reverse: 5′-TTGGGGACACTCTTTGGGTAGAGTT-3′; Ctsk-forward: 5′-ACGGAGGCATTGACTCTGAAGATG-3′; Ctsk-reverse: 5′-GGAAGCACCAACGAGAGGAGAAAT-3′; Dc-stamp-forward: 5′-TCCTCCATGAACAAACAGTTCCAA-3′; Dc-stamp-reverse: 5′-AGACGTGGTTTAGGAATGCAGCTC-3′; Nfatc1-forward: 5′-CAAGTCTCACCACAGGGCTCACTA-3′; Nfatc1-reverse: 5′-GCGTGAGAGGTTCATTCTCCAAGT-3′; Runx2-forward: 5′-GACGTGCCCAGGCGTATTTC-3′; Runx2-reverse: 5′-AAGGTGGCTGGGTAGTGCATTC-3′; Col1a1-forward: 5′-CCTGGTAAAGATGGTGCC-3′; Col1a1-reverse: 5′-CACCAGGTTCACCTTTCGCACC-3′; Ocn-forward: 5′-TAGCAGACACCATGAGGACCCT-3′; Ocn-reverse: 5′-TGGACATGAAGGCTTTGTCAGA-3′.

Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorter Analysis

Splenocytes and bone marrow cells were layered onto a lympholyte-M gradient (CEDERLANE, Hornby, ON, Canada). After centrifugation, monolayer cells were collected from the upper layer and incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies diluted 1:200 for 30 min on ice. Cells were washed twice and suspended in 5% FBS-PBS containing propidium iodide. Analysis was performed using fluorescence-activated cell sorter (BD FACSAria II, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Data were analyzed using BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Antibodies for c-Fms (AFS98), B220 (RA3–6B2), CD3 (500A2), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (HL3), Gr-1 (RB6–8C5), IgM (II/41), and c-Kit (2B8) were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA).

Analysis of Skeletal Morphology

Mouse hindlimbs were collected from Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice and Blimp1fl/fl littermate control mice 5 weeks after pI-pC injections. Tissues were fixed with 70% ethanol and subjected to dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) analysis to measure bone mineral density (BMD). Sections were prepared in the same way for staining with toluidine blue O and for TRAP activity. Bone histomorphometric analysis was performed to quantify bone parameters as described (7). Col1a1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice and Blimp1fl/fl littermate controls were subjected to DEXA analysis at 8 weeks of age.

RESULTS

Blimp1 Inactivation Inhibits Osteoclast Differentiation

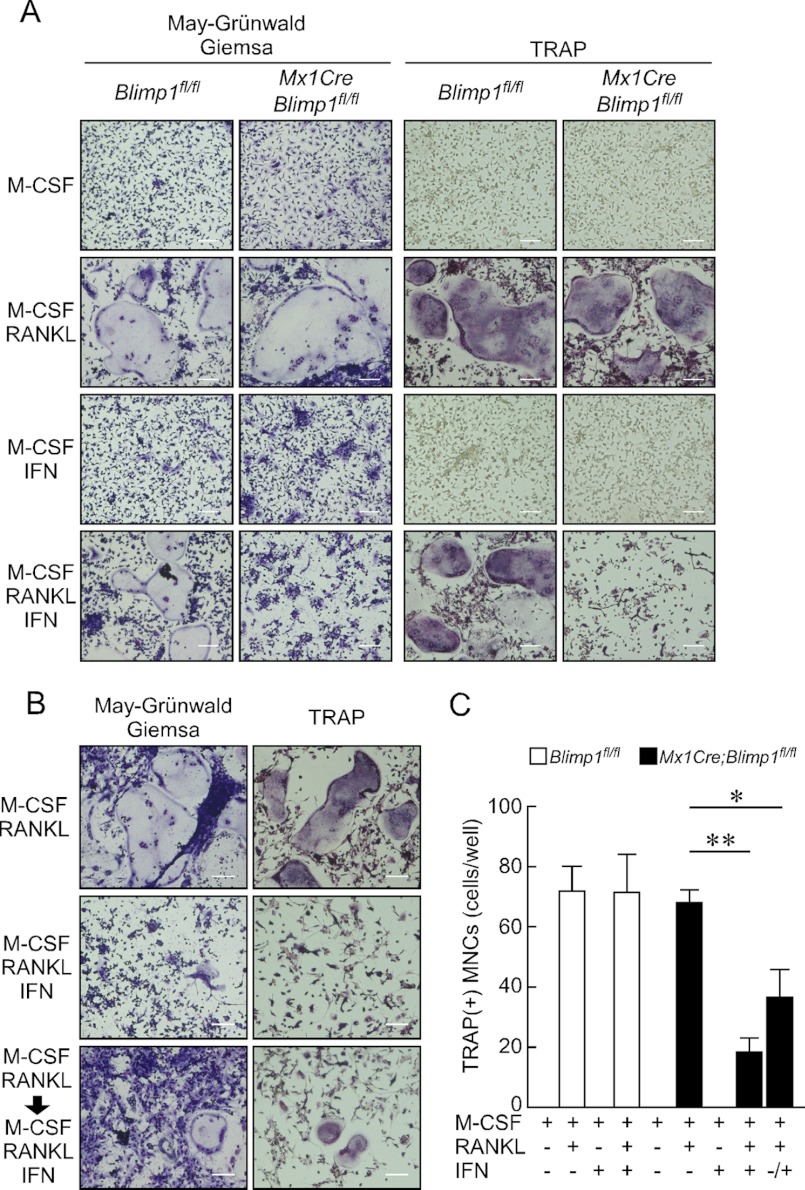

In a previous ex vivo study, the Mx1 promoter was shown to be activated by treatment with IFN (21). IFN reportedly inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro and in vivo (22), however, IFN at concentrations sufficient to activate the Mx1 promoter (100 units/ml) did not inhibit osteoclast formation in Blimp1fl/fl cells (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. S1). Thus we employed this IFN concentration in the following experiments. First, Blimp1 was deleted by IFN treatment in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl osteoclast progenitor cells, which were then cultured in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL (Fig. 1A). Blimp1 deletion in osteoclast progenitors significantly inhibited multinuclear TRAP-positive cell formation (Fig. 1A). IFN was then added to the culture 1 day after RANKL stimulation, and osteoclastogenesis was also significantly inhibited in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl cells but not in Blimp1fl/fl cells (Fig. 1, A and B). The number of TRAP-positive multinuclear cells formed by RANKL stimulation was significantly reduced in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl cells compared with Blimp1fl/fl cells, Mx1Cre cells or IFN(−) controls (Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. S2). These ex vivo analyses indicate that Blimp1 is essential for osteoclastogenesis of osteoclast progenitors, even after RANKL stimulation.

FIGURE 1.

Blimp1 inactivation impairs osteoclast differentiation. Bone marrow cells prepared from Blimp1fl/fl and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice were subjected to osteoclast formation in vitro. A, osteoclast precursor cells pre-treated with IFN (100 units/ml) were cultured for 5 days and subjected to May-Grünwald Giemsa and TRAP staining to assess osteoclast differentiation. Bar, 100 μm. B, osteoclast precursor cells were cultured for 5 days with or without IFN and subjected to similar analysis after RANKL stimulation. Bars: 100 μm. C, number of TRAP-positive cells containing more than three nuclei was scored. White (Blimp1fl/fl) and black (Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl) bars indicate means ± S.D. (**, p < 0.001; n = 3).

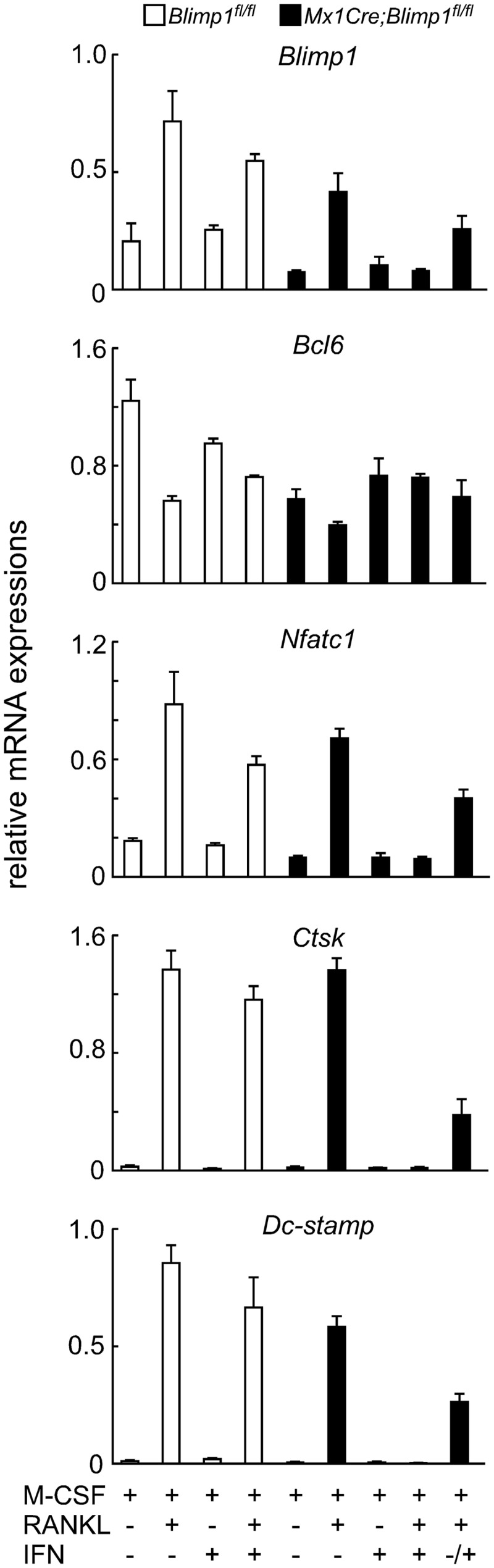

Evaluation of expression of osteoclast differentiation markers by qPCR confirmed the inhibitory effects of Blimp1 inactivation on osteoclast differentiation (Fig. 2). Bcl6 expression is reportedly inhibited by Blimp1 in osteoclastogenesis (7). Indeed, we found that Bcl6 expression was suppressed in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl cells in the presence of RANKL and the absence of IFN. However, IFN treatment of Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl cells blocked Bcl6 suppression, even in the presence of RANKL (Fig. 2). Inhibited osteoclastogenesis seen in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl cells following Blimp1 inactivation was confirmed by down-regulation of osteoclastic genes such as Nfatc1 (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Blimp1 inactivation inhibits expression of osteoclast-specific genes. Bone marrow cells prepared from Blimp1fl/fl (white bars) and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl (black bars) mice were cultured in the presence or absence of RANKL with or without IFN for 5 days. Gene expression was analyzed by qPCR. Data represent mean expression of indicated gene relative to Actb ± S.D. (n = 3).

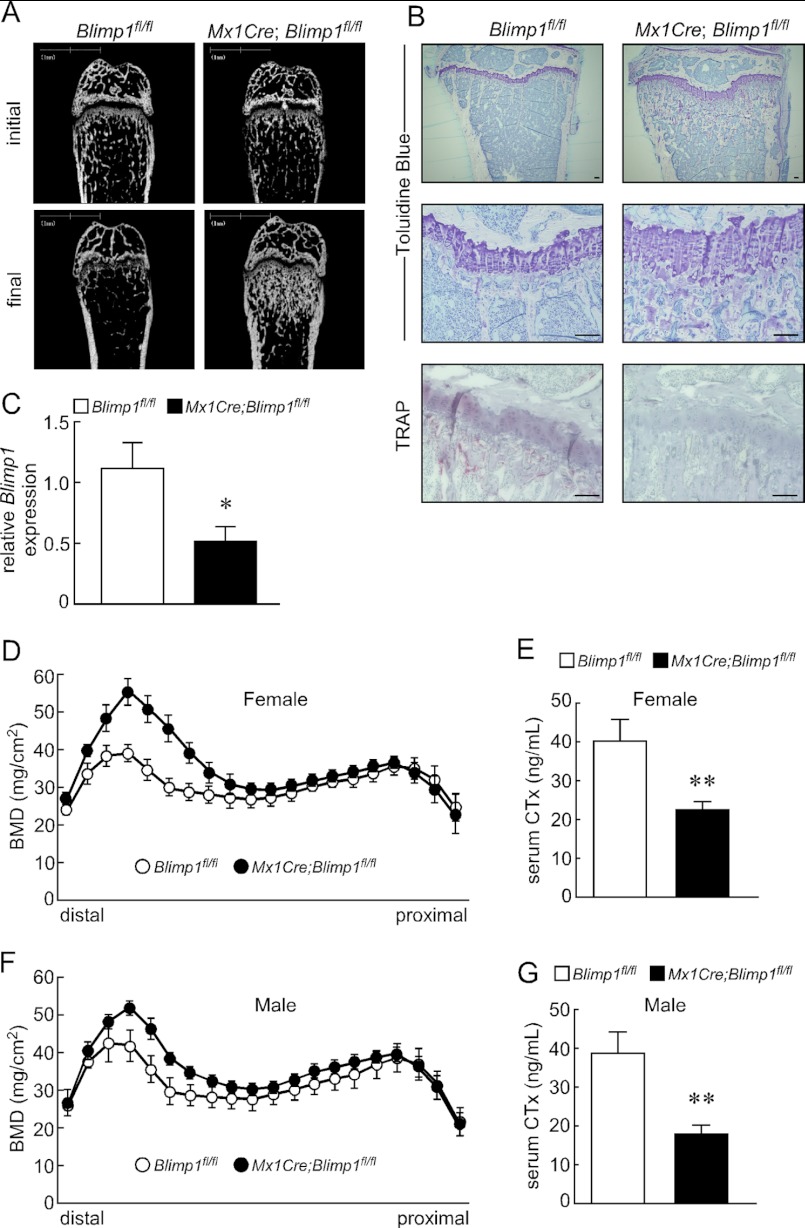

Blimp1 Inactivation Increases Bone Mass

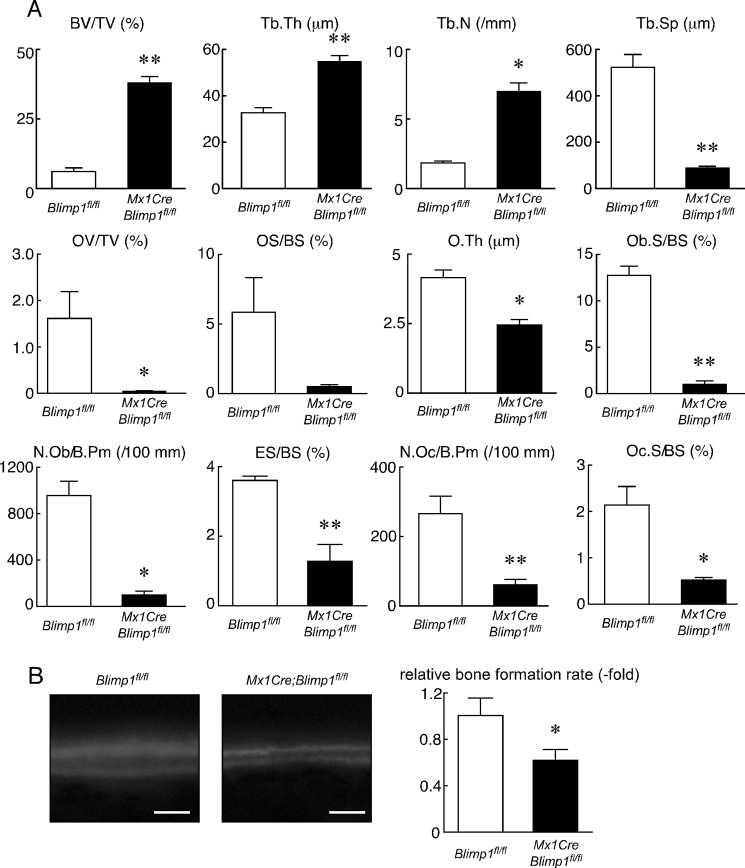

To assess skeletal phenotypes following Blimp1 inactivation in adult animals, we collected the long bones (tibias and femurs) from eight-week-old Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl and Blimp1fl/fl littermate controls before (initial) and 5 weeks after final injection of polyinosine-polycytidylic acid (pI-pC) used to activate the Mx1 promoter by inducing IFN. These mice survived, grew normally and did not show pathologies such as abnormal weight loss (data not shown). Microradiographical analysis of femurs showed no gross in bone mass between Blimp1fl/fl and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice before pI-pC injection. However, markedly increased trabecular bone mass was evident in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice that received pI-pC compared with Blimp1fl/fl mice (Fig. 3A). Photomicrographs of toluidine blue O staining of femurs from Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl and Blimp1fl/fl mice after pI-pC injection confirmed the phenotypes (Fig. 3B). TRAP staining of femurs revealed significant inhibition of TRAP-positive osteoclast formation in pI-pC injected Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice relative to Blimp1fl/fl mice (Fig. 3B). Reduced Blimp1 expression seen in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl bones relative to control bones was confirmed by qPCR (Fig. 3C). Increased bone mass and inhibited bone resorption in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice with pI-pC treatment relative to Blimp1fl/fl mice were also detected by DEXA analysis and serum CTx levels, respectively (Fig. 3, D–G). In both male and female mice, pI-pC treatment promoted increased bone mineral density (BMD) (Fig. 3, D and F) and decreased bone resorption (Fig. 3, E and G) in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice compared with Blimp1fl/fl mice. These data demonstrate that Blimp1 loss in adult mice significantly reduces bone resorbing activity and increases bone mass, and that effects were not affected by gender. We undertook morphometric analysis of pI-pC treated Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl and Blimp1fl/fl mice, and found that increase of bone volume per total volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb. Th) and trabecular number (Tb. N), and decreased trabecular spaces (Tb. Sp) in the secondary trabecular area by conditional inactivation of Blimp1 (Fig. 4A). We also found that decreased eroded surface per bone surface (ES/BS), osteoclast number per bone perimeter (N.Oc/B.Pm) and osteoclast surface per bone surface (Oc.S/BS) in the secondary trabecular area by conditional inactivation of Blimp1 (Fig. 4A). This analysis indicates that marked augmentation in bone mass (based on BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N, and Tb.Sp) was likely due to severely impaired bone resorption following inhibition of osteoclastogenesis (indicated by ES/BS, N.Oc/B.Pm, and Oc.S/BS). These data are consistent with the histological and biochemical analyses as shown in Fig. 3. Histomorphometrical analysis also indicated that Blimp1 deficiency decreased osteoblast differentiation and bone formation (based on OV/TV, OS/BS, O.Th, and Ob.S/BS). Toluidine blue staining revealed a reduced number of osteoblasts per perimeter (N.Ob/B.Pm) in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl compared with Blimp1fl/fl mice (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, a calcein double labeling assay showed reduced bone formation following conditional inactivation of Blimp1 (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 3.

Conditional inactivation of Blimp1 increases bone volume. A, micro CT analysis of femurs of Blimp1fl/fl and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl female mice before (initial) and 5 weeks after (final) pI-pC injection. Bars: 1 mm. B, longitudinal sections of tibias of Blimp1fl/fl and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl female mice were stained with toluidine blue and TRAP activity and shown by low and high magnification. Bars: 100 μm. C, qPCR analysis of Blimp1 in long bones of Blimp1fl/fl and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl female mice treated with pI-pC. Bars indicate mean expression relative to Actb ± S.D. (n = 3). D and F, BMD of equal longitudinal division of femurs of Blimp1fl/fl and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice. Data are means ± S.D. (n = 5 mice/group). Female and male BMD are shown in D and F, respectively. E and G, serum CTx levels in Blimp1fl/fl (white bars) and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl (black bars) mice. Bars indicate mean serum CTx (ng/ml) ± S.D. (**, p < 0.001; n = 5 mice/group). Female and male Serum CTx levels are shown in E and G, respectively. Analyses were undertaken 5 weeks after completion of pI-pC injections (B–G).

FIGURE 4.

Conditional inactivation of Blimp1 alters bone resorption and formation parameters. A, bone histomorphometrical analysis of femurs of Blimp1fl/fl (white bars) and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl (black bars) female mice 5 weeks after pI-pC injection. Data represent the mean value of the indicated parameter ± S.D. (*, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001; n = 5 mice/group). B, left panel, Calcein-labeled bones were observed under a fluorescence microscope. Bars: 10 μm. Right panel, white (Blimp1fl/fl) and black (Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl) bars indicate mean relative bone formation rate ± S.D. (*, p < 0.01; n = 5).

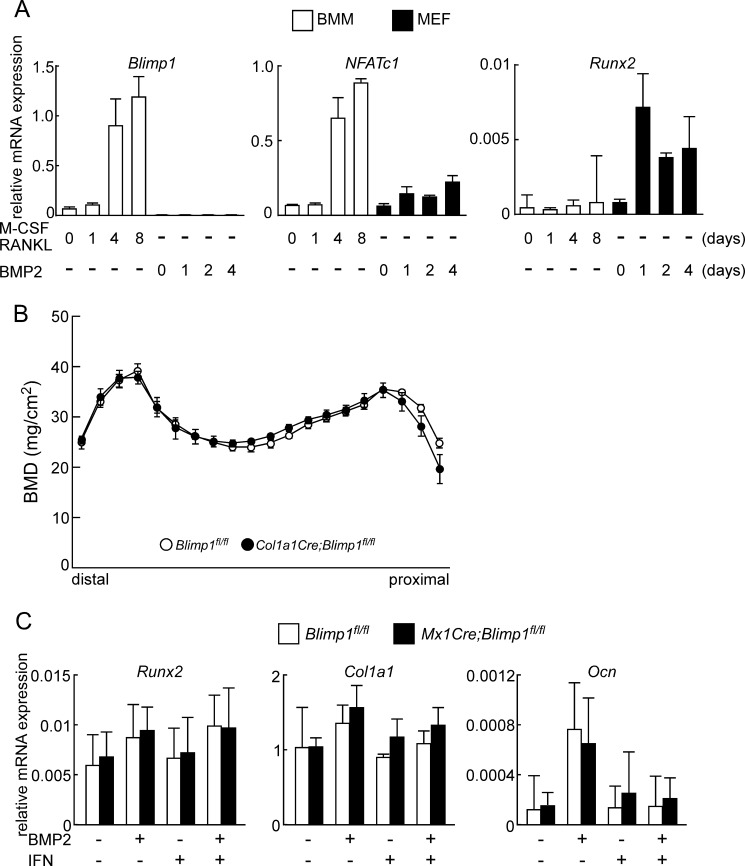

Overall phenotypes seen following Blimp1 inactivation are likely due to disruptions in the coupled activity of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, since osteoblast activity is known to be paralleled with osteoclast activity (23). To study a potential role for Blimp1 in osteoblasts, Blimp1 expression was analyzed in osteoclasts and osteoblasts in cultured cells from wild-type mice (Fig. 5). Mouse bone marrow macrophages (BMMs) were cultured for osteoclast formation in the presence of M-CSF plus RANKL. In contrast, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were stimulated for osteoblast differentiation by BMP2. Then, these cells were subjected to qPCR analysis (Fig. 5A). Blimp1 was expressed in osteoclasts, which also expressed Nfatc1, but was little detected in MEFs stimulated to undergo osteoblast differentiation, even in cells positive for Runx2, a master regulator of osteoblastogenesis. Blimp1 expression was significantly higher in osteoclasts than in osteoblasts. We also generated osteoblast-specific Blimp1 conditional knock-out mice (Col1a1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl); however, no significant phenotypic differences were seen between Col1a1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl and control Blimp1fl/fl mice (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, osteoblast-related gene expression in primary osteoblasts isolated from Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl was comparable to that seen in Blimp1fl/fl osteoblasts, even in the presence of IFN (Fig. 5, B and C). Thus, we conclude that Blimp1 is dispensable for osteoblastogenesis and that increased bone mass seen following systemic Blimp1 inactivation in vivo is likely due to effects primarily in osteoclasts.

FIGURE 5.

Blimp1 expression is crucial for osteoclastogenesis. A, BMMs (white bars) and MEFs (black bars) prepared from wild type mice were subjected to osteoclastogenic or osteoblastogenic culture, respectively, followed by qPCR analysis. Bars indicate mean expression of indicated genes relative to Actb ± S.D. (n = 3). B, BMD of equal longitudinal division of femurs of Blimp1fl/fl and Col1a1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice. Data are means ± S.D. (n = 5 mice/group). C, mouse primary osteoblasts from Blimp1fl/fl (white bars) and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl (black bars) were cultured in indicated conditions for 3 days and then subjected to qPCR analysis. Bars indicate mean expression of indicated genes relative to Actb ± S.D. (n = 3).

Blimp1 Inactivation in Adult Mice Has No Effect on Immune Cells

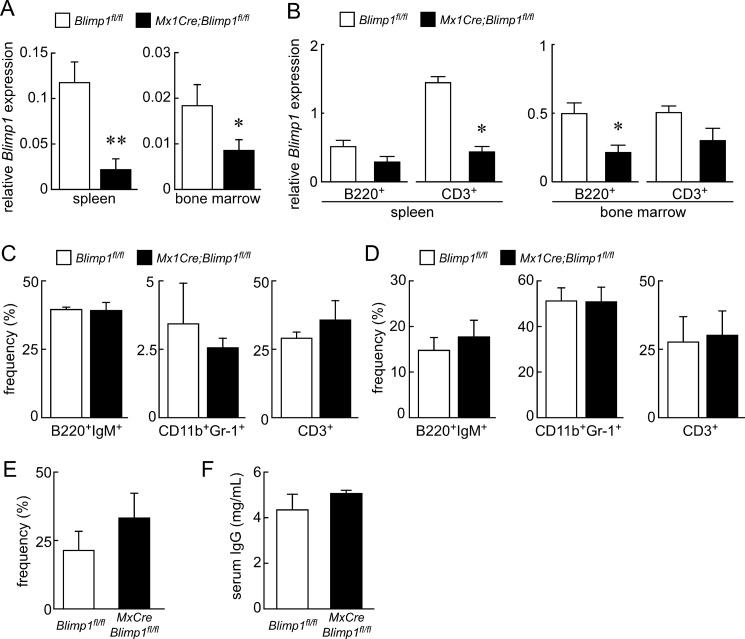

Finally, we analyzed the effects of Blimp1 inactivation on immune cells, since Blimp1 reportedly functions in immune cell development (11–13). Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl and Blimp1fl/fl mice were administrated pI-pC, and 5 weeks after pI-pC injection, splenocytes and bone marrow cells were collected from pI-pC-treated Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl and control mice and subjected to qPCR and FACS analyses. qPCR analysis of whole spleen and bone marrow confirmed that Blimp1 transcripts were markedly decreased in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice than Blimp1fl/fl mice (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, B220-positive B cells and CD3-positive T cells were sorted from spleen and bone marrow cells, and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl T and B cells showed reduced Blimp1 expression compared with Blimp1fl/fl cells (Fig. 6B). FACS analysis demonstrated that the frequencies of IgM-positive B cells, myeloid cells and T cells were unchanged by Blimp1 inactivation in both splenocytes and bone marrow cells of Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice compared with Blimp1fl/fl mice (Fig. 6, C and D). Interestingly, the frequency of osteoclast progenitor cells (c-Kit+CD11blowc-Fms+, 24) in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl bone marrow cells increased compared with control cells (Fig. 6E). Quantification of serum IgG levels in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl and Blimp1fl/fl mice demonstrated that Blimp1 deficiency did not impair IgG production (Fig. 6F), and that maturation and function of plasmacytes were normal following Blimp1 inactivation in adults. These findings indicate that conditional inactivation of Blimp1 in adult mice has little impact on immune cells.

FIGURE 6.

Immune cells are maintained after Blimp1 inactivation in adults. Spleen and bone marrow cells from Blimp1fl/fl (white bars) and Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl (black bars) female mice 5 weeks after pI-pC injection were analyzed. A, Blimp1 mRNA levels in spleen and bone marrow. B, Blimp1 mRNA levels in B220+ and CD3+ cells sorted from spleen and bone marrow. qPCR data represent mean expression relative to Actb ± S.D. (*, p < 0.01; n = 3). C and D, flow cytometric analysis of B220+IgM+, CD11b+Gr-1+ and CD3+ cells in spleen and bone marrow cells. Data for spleen and bone marrow cells are shown in C and D, respectively. E, flow cytometric analysis of osteoclast progenitors (c-Kit+CD11clowc-Fms+ cells) in bone marrow cells. F, serum IgG levels were determined by ELISA. Bars indicate mean serum IgG levels (mg/ml) ± S.D. (*, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001; n = 3 mice/group).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we established Blimp1-conditional knock-out mice by IFN-dependent Mx1Cre and found that conditional Blimp1 inactivation in adult mice promoted decreased osteoclast formation and increased bone mass. By contrast, although Blimp1 reportedly functions in lymphocyte development, immune cells were not impaired by loss of Blimp1 in adult mice. Blimp1-null mice show early embryonic lethality (25); however, when we inactivated Blimp1 in adult mice, animals survived and did not exhibit severe defects, such as weight loss, but rather showed increased bone mass. Therefore, Blimp1 could potentially be targeted therapeutically to block osteoclast formation in adults.

Blimp1 controls cell-fate decisions in mouse embryos and governs tissue homeostasis in multiple cell types in the adult organism (26). Developmental defects due to Blimp1 deficiency include defective placental development and abnormal branchial arch patterning, widespread blood leakage and tissue apoptosis, leading to lethality at ∼11.5 dpc (25). Studies reporting conditional inactivation of Blimp1 using various Cre transgenes reveal that Blimp1 regulates development or homeostasis of various tissues. Sox2-Cre-dependent Blimp1 knock-out phenotypes indicate a role for Blimp1 in development of the posterior forelimb, caudal pharyngeal arches, secondary heart field and sensory vibrissae (17). Conditional Blimp1 inactivation via CD19Cre/+ or Lck-Cre mice indicates that Blimp1 controls plasmacytogenesis and T cell homeostasis, respectively (11–13). Use of an intestine-specific Cre driver demonstrates a Blimp1 function in regulating development of the intestinal epithelium (15, 16). Finally, use of an osteoclast-specific CtskCre/+ indicates that Blimp1 is required to suppress transcriptional repressors of osteoclastogenesis (7, 9). To examine the effect of systemic inactivation of Blimp1 in adults we employed Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice. This is a new approach to elucidate the exact roles of Blimp1 in an adult stage. Our observations suggest that Blimp1 is not required to maintain organs in which it functions developmentally but is important for osteoclastogenesis and bone homeostasis in adults. Reduction in Blimp1 expression in various cell types of Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice was not complete following pI-pC injection; instead, phenotypes were specifically seen in osteoclasts, suggesting that remaining Blimp1 is likely sufficient to maintain CD3- and B220-positive cells but not osteoclasts at an adult stage. Alternatively, functional redundancy mediated by Blimp1 homologues in tissues other than osteoclasts at an adult stage may explain our results. Blimp1 is a member of the PRDM gene family, which includes 17 and 16 putative members in primates and rodents, respectively (26). Blimp1 exhibits domains characteristic of PRDM family transcriptional repressors, and other family members may compensate for Blimp1 function in some tissues. Further studies are needed to address redundant functions of these proteins in adulthood. As a transcriptional repressor, Blimp1 recruits epigenetic modifiers to alter chromatin architecture at target sites and uses different cofactors to mediate gene silencing, including a histone methyltransferase, a histone deacetylase, or a histone lysine demethylase (26). Identification of Blimp1 interacting proteins in osteoclasts may enhance our understanding of osteoclast differentiation via epigenetic regulation.

Conditional inactivation of Blimp1 in adult mice by pI-pC treatment resulted in severe defects in bone formation (as assessed by OV/TV, OS/BS, O.Th, N.Ob/B.Pm, and Ob.S/BS) and bone resorption (indicated by ES/BS, N.Oc/B.Pm, and Oc.S/BS), and promoted increased bone mass. We also detected much higher levels of Blimp1 transcripts in osteoclasts than in osteoblasts. Also, utilization of in vivo and ex vivo models enabled us to show that Blimp1 deficiency in osteoblasts did not result in bone phenotypes or changes in osteoblast-related gene expression. Osteoclast and osteoblast activity is reportedly coupled (23), suggesting that the reduced osteoblast activity seen here following conditional Blimp1 inactivation is due to impaired osteoclastic activity.

Our ex vivo studies reveal that the Blimp1 inactivation inhibited osteoclastogenesis in undifferentiated precursors and pre-osteoclasts stimulated with RANKL, suggesting that osteoclastogenesis could be blocked by Blimp1 inhibition even under RANKL-stimulated conditions in vivo. Accumulation of osteoclast progenitors in bone marrow in Mx1Cre;Blimp1fl/fl mice treated with pI-pC is likely a consequence of inhibited osteoclast differentiation. Recently, studies have shown that RANKL neutralization by specific monoclonal antibodies improves pathological bone resorption and elevates bone mass by preventing osteoclast differentiation (27, 28). Blimp1 inactivation likely promotes bone phenotypes similar to those seen with anti-RANKL antibodies and provides a new strategy to treat bone destructive disease. While Blimp1 has not been investigated as a target for drug discovery, there are successful experiences that transcription factors serve as potent drug targets. For instance, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) functions in insulin-sensitization of type 2 diabetes and in fat cell differentiation, and the compounds modulating PPARγ functions have been developed as anti-diabetic drugs (29, 30). Thus, there is precedent to consider transcription factors, such as Blimp1, as drug targets to treat pathological conditions.

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- RANKL

- receptor activator for NF-κB ligand

- Blimp1

- B-lymphocyte induced maturation protein 1

- Nfatc1

- nuclear factor for activated T cells, cytoplasmic, calcineurin-dependent 1

- Dc-stamp

- dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein

- Ctsk

- cathepsin K

- Bcl6

- B-cell lymphoma 6

- pI-pC

- polyinosine-polycytidylic acid

- MNC

- multinuclear cell

- M-CSF

- macrophage-colony stimulating factor

- BMP2

- bone morphogenetic protein-2

- Ocn

- osteocalcin

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

- BMM

- mouse bone marrow macrophage

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- CTx

- C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen

- DEXA

- dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- BMD

- bone mineral density

- micro CT

- micro computed tomography

- BV/TV

- bone volume per total volume

- Tb.Th

- trabecular thickness

- Tb.N

- trabecular number

- Tb.Sp

- trabecular space

- OV/TV

- osteoid volume per total volume

- OS/BS

- osteoid surface per bone surface

- O.Th

- osteoid thickness

- Ob.S/BS

- osteoblast surface per bone surface

- N.Ob/B.Pm

- osteoblast number per bone perimeter

- ES/BS

- eroded surface per bone surface

- N.Oc/B.Pm

- osteoclast number per bone perimeter

- N.Ob/B.Pm

- osteoblast number per bone perimeter

- Oc.S/BS

- osteoclast surface to bone surface

- PPARγ

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ.

REFERENCES

- 1. Karsenty G., Wagner E. F. (2002) Reaching a genetic and molecular understanding of skeletal development. Dev. Cell 2, 389–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rodan G. A., Martin T. J. (2000) Therapeutic approaches to bone diseases. Science 289, 1508–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kong Y. Y., Yoshida H., Sarosi I., Tan H. L., Timms E., Capparelli C., Morony S., Oliveira-dos-Santos A. J., Van G., Itie A., Khoo W., Wakeham A., Dunstan C. R., Lacey D. L., Mak T. W., Boyle W. J., Penninger J. M. (1999) OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature 397, 315–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nakashima T., Takayanagi H. (2009) Osteoclasts and the immune system. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 27, 519–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yagi M., Miyamoto T., Sawatani Y., Iwamoto K., Hosogane N., Fujita N., Morita K., Ninomiya K., Suzuki T., Miyamoto K., Oike Y., Takeya M., Toyama Y., Suda T. (2005) DC-STAMP is essential for cell-cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Exp. Med. 202, 345–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li C. Y., Jepsen K. J., Majeska R. J., Zhang J., Ni R., Gelb B. D., Schaffler M. B. (2006) Mice lacking cathepsin K maintain bone remodeling but develop bone fragility despite high bone mass. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 865–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miyauchi Y., Ninomiya K., Miyamoto H., Sakamoto A., Iwasaki R., Hoshi H., Miyamoto K., Hao W., Yoshida S., Morioka H., Chiba K., Kato S., Tokuhisa T., Saitou M., Toyama Y., Suda T., Miyamoto T. (2010) The Blimp1-Bcl6 axis is critical to regulate osteoclast differentiation and bone homeostasis. J. Exp. Med. 207, 751–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pasqualucci L., Bereschenko O., Niu H., Klein U., Basso K., Guglielmino R., Cattoretti G., Dalla-Favera R. (2003) Molecular pathogenesis of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: the role of Bcl-6. Leuk. Lymphoma 44, S5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nishikawa K., Nakashima T., Hayashi M., Fukunaga T., Kato S., Kodama T., Takahashi S., Calame K., Takayanagi H. (2010) Blimp1-mediated repression of negative regulators is required for osteoclast differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 3117–3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ohinata Y., Payer B., O'Carroll D., Ancelin K., Ono Y., Sano M., Barton S. C., Obukhanych T., Nussenzweig M., Tarakhovsky A., Saitou M., Surani M. A. (2005) Blimp1 is a critical determinant of the germ cell lineage in mice. Nature 436, 207–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shapiro-Shelef M., Lin K. I., McHeyzer-Williams L. J., Liao J., McHeyzer-Williams M. G., Calame K. (2003) Blimp-1 is required for the formation of immunoglobulin secreting plasma cells and pre-plasma memory B cells. Immunity 19, 607–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martins G. A., Cimmino L., Shapiro-Shelef M., Szabolcs M., Herron A., Magnusdottir E., Calame K. (2006) Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 regulates T cell homeostasis and function. Nat. Immunol. 7, 457–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kallies A., Hawkins E. D., Belz G. T., Metcalf D., Hommel M., Corcoran L. M., Hodgkin P. D., Nutt S. L. (2006) Transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 is essential for T cell homeostasis and self-tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 7, 466–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kallies A., Carotta S., Huntington N. D., Bernard N. J., Tarlinton D. M., Smyth M. J., Nutt S. L. (2011) A role for Blimp1 in the transcriptional network controlling natural killer cell maturation. Blood 117, 1869–1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harper J., Mould A., Andrews R. M., Bikoff E. K., Robertson E. J. (2011) The transcriptional repressor Blimp1/Prdm1 regulates postnatal reprogramming of intestinal enterocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 10585–10590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muncan V., Heijmans J., Krasinski S. D., Büller N. V., Wildenberg M. E., Meisner S., Radonjic M., Stapleton K. A., Lamers W. H., Biemond I., van den Bergh Weerman M. A., O'Carroll D., Hardwick J. C., Hommes D. W., van den Brink G. R. (2011) Blimp1 regulates the transition of neonatal to adult intestinal epithelium. Nat. Commun. 2, 452–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robertson E. J., Charatsi I., Joyner C. J., Koonce C. H., Morgan M., Islam A., Paterson C., Lejsek E., Arnold S. J., Kallies A., Nutt S. L., Bikoff E. K. (2007) Blimp1 regulates development of the posterior forelimb, caudal pharyngeal arches, heart and sensory vibrissae in mice. Development 134, 4335–4345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakanishi R., Akiyama H., Kimura H., Otsuki B., Shimizu M., Tsuboyama T., Nakamura T. (2008) Osteoblast-targeted expression of Sfrp4 in mice results in low bone mass. J. Bone Miner. Res. 23, 271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miyamoto T., Arai F., Ohneda O., Takagi K., Anderson D. M., Suda T. (2000) An adherent condition is required for formation of multinuclear osteoclasts in the presence of macrophage colony-stimulating factor and receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand. Blood 96, 4335–4343 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tohmonda T., Miyauchi Y., Ghosh R., Yoda M., Uchikawa S., Takito J., Morioka H., Nakamura M., Iwawaki T., Chiba K., Toyama Y., Urano F., Horiuchi K. (2011) The IRE1α-XBP1 pathway is essential for osteoblast differentiation through promoting transcription of Osterix. EMBO Rep. 12, 451–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoelbl A., Schuster C., Kovacic B., Zhu B., Wickre M., Hoelzl M. A., Fajmann S., Grebien F., Warsch W., Stengl G., Hennighausen L., Poli V., Beug H., Moriggl R., Sexl V. (2010) Stat5 is indispensable for the maintenance of bcr/abl-positive leukaemia. EMBO Mol. Med. 2, 98–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takayanagi H., Kim S., Matsuo K., Suzuki H., Suzuki T., Sato K., Yokochi T., Oda H., Nakamura K., Ida N., Wagner E. F., Taniguchi T. (2002) RANKL maintains bone homeostasis through c-Fos-dependent induction of interferon-β. Nature 416, 744–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ninomiya K., Miyamoto T., Imai J., Fujita N., Suzuki T., Iwasaki R., Yagi M., Watanabe S., Toyama Y., Suda T. (2007) Osteoclastic activity induces osteomodulin expression in osteoblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 362, 460–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arai F., Miyamoto T., Ohneda O., Inada T., Sudo T., Brasel K., Miyata T., Anderson D. M., Suda T. (1999) Commitment and differentiation of osteoclast precursor cells by the sequential expression of c-Fms and receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANK) receptors. J. Exp. Med. 190, 1741–1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vincent S. D., Dunn N. R., Sciammas R., Shapiro-Shalef M., Davis M. M., Calame K., Bikoff E. K., Robertson E. J. (2005) The zinc finger transcriptional repressor Blimp1/Prdm1 is dispensable for early axis formation but is required for specification of primordial germ cells in the mouse. Development 132, 1315–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bikoff E. K., Morgan M. A., Robertson E. J. (2009) An expanding job description for Blimp-1/PRDM1. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19, 379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baron R., Ferrari S., Russell R. G. (2011) Denosumab and bisphosphonates: different mechanisms of action and effects. Bone 48, 677–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Furuya Y., Mori K., Ninomiya T., Tomimori Y., Tanaka S., Takahashi N., Udagawa N., Uchida K., Yasuda H. (2011) Increased bone mass in mice after single injection of anti-receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand-neutralizing antibody: evidence for bone anabolic effect of parathyroid hormone in mice with few osteoclasts. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 37023–37031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tontonoz P., Spiegelman B. M. (2008) Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARγ. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 289–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Choi J. H., Banks A. S., Kamenecka T. M., Busby S. A., Chalmers M. J., Kumar N., Kuruvilla D. S., Shin Y., He Y., Bruning J. B., Marciano D. P., Cameron M. D., Laznik D., Jurczak M. J., Schürer S. C., Vidović D., Shulman G. I., Spiegelman B. M., Griffin P. R. (2011) Antidiabetic actions of a non-agonist PPARγ ligand blocking Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation. Nature 477, 477–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.