Abstract

Background

The burden of antimicrobial resistance worldwide is substantial and is likely to grow. Many factors play a role in the emergence of resistance. These resistance mechanisms may be encoded on transferable genes, which facilitate the spread of resistance between bacterial strains of the same and/or different species. Other resistance mechanisms may be due to alterations in the chromosomal DNA which enables the bacteria to withstand the environment and multiply. Many, if not most, of the Gulf Corporation Council (GCC) countries do not have clear guidelines for antimicrobial use, and lack policies for restricting and auditing antimicrobial prescriptions.

Objective

The aim of this study is to review the prevalence of antibiotic resistance in GCC countries and explore the reasons for antibiotic resistance in the region.

Methodology

The PubMed database was searched using the following key words: antimicrobial resistance, antibiotic stewardship, prevalence, epidemiology, mechanism of resistance, and GCC country (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and United Arab Emirates).

Results

From January1990 through April 2011, there were 45 articles published reviewing antibiotic resistance in the GCC countries. Among all the GCC countries, 37,295 bacterial isolates were studied for antimicrobial resistance. The most prevalent microorganism was Escherichia coli (10,073/44%), followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (4,709/20%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (4,287/18.7%), MRSA (1,216/5.4%), Acinetobacter (1,061/5%), with C. difficile and Enterococcus representing less than 1%.

Conclusion

In the last 2 decades, E. coli followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae were the most prevalent reported microorganisms by GCC countries with resistance data.

Keywords: Antibiotics/antimicrobials; Resistance; GCC; (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and United Arab Emirates) Gram negative; Gram positive; Anaerobes; Pathogens; Infection; Resistance mechanisms; Molecular typing

Findings

The burden of antimicrobial resistance worldwide is substantial and is likely to grow [1]. Furthermore, many factors play a role in the emergence of resistance such as from poor utilization of antimicrobial agents, transmission of resistant bacteria from patient to patient and from Health-care workers (HCWs) to patients and vice versa, lack of guidelines for appropriate and judicious use of antimicrobial agents and lack of easy-to-use auditing tools for restriction. In addition, there is clear misuse of antimicrobial agents in the animal industry, and most agents are the same agents used in humans. Further, there are few antimicrobial agents in the pipeline of production, leaving clinicians with minimal tools to combat these infections. All these factors, together, have led to the inevitable emergence and rise of resistance.

Bacteria develop antimicrobial resistance through many mechanisms including mutations in penicillin binding proteins, efflux mechanisms, alterations in outer membrane proteins and the production of hydrolyzing enzymes such as extended spectrum β lactamase (ESBL) and carbapenemases [2]. These resistance mechanisms may be encoded on transferable genes which facilitate the spread between bacteria of the same species and between different species. Other resistance mechanisms may be due to alterations in the chromosomal DNA which enables the bacteria to withstand the harsh environment and multiply.

Many, if not most, of the Gulf Corporation Council (GCC) countries do not have clear guidelines for antimicrobial use and lack policies for restricting and auditing antimicrobial prescriptions. There are no guidelines for the use of antimicrobials in the animal industries either. Thus, it is not surprising that antimicrobial resistance has emerged in these countries [3]. There are few reports studying prevalence rates of resistance among the different pathogens and mechanisms of resistance at the national level.

Objective

The aim of this study is to review the prevalence of antibiotic resistance in GCC countries and explore the reasons for antibiotic resistance in the region.

Methodology

The PubMed database was searched using the following key words: antimicrobial resistance, antibiotic stewardship, prevalence, epidemiology, mechanism of resistance, and GCC country (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and United Arab Emirates). Specific organisms were searched for Gram negative bacteria: Acinetobacter, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli, and for Gram positive bacteria: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci (VRE) and Clostridium difficile (C. difficile). To identify the resistance mechanisms, these studies followed routine laboratory diagnostics and surveillance testing.

Statistical analysis

Statistical data were generated and analyzed using the statistical software SPSS version 19. Descriptive statistics were calculated and the weighted mean was estimated using the estimated marginal mean function in SPSS. Data were expressed as number (n) and percentage (%); Table 1. Records of the total numbers of clinical isolates were grouped based on their country and species according to their gram staining classification; Table 2. Data were represented as total number of isolates (n) and their percentage (%).

Table 1.

The data of selected clinical isolates reported by GCC countries

| Country | Population | Population % | Reports (n) | Reports% | Isolates (n) | Isolates% | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahrain |

1,106,509 |

2.9% |

3 |

9.1% |

2841 |

7.6% |

[4-6] |

| Kuwait |

2,583,020 |

6.7% |

9 |

27.3% |

20339 |

54.5% |

[7-15] |

| Oman |

3,173,917 |

8.2% |

3 |

9.1% |

882 |

2.4% |

[8,16,17] |

| Qatar |

1,608,903 |

4.2% |

2 |

6.1% |

570 |

1.5% |

[7,18] |

| Saudi Arabia |

25,373,512 |

65.7% |

14 |

42.4% |

12174 |

32.6% |

[19-32] |

| UAE |

4,765,000 |

12.3% |

2 |

6.1% |

491 |

1.3% |

[33,34] |

| GCC total | 38,610,861 | 100.0% | 33 | 100.0% | 37295 | 100.0% | n = 33 articles |

GCC = Gulf Corporation Council; UAE = United Arab Emirates.

Table 2.

The prevalence of resistant pathogens in clinical isolates from GCC countries

| Country |

Gram Negative |

Gram Positive |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter | Escherichiacoli | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Clostridium difficile | Enterococcus | MRSA | Streptococcus pneumoniae | |

|

Bahrain |

N.R |

14.0% |

13.9% |

N.R |

N.R |

76.5% |

8.5% |

N.R |

|

Kuwait |

16.7% |

77.0% |

36.2% |

2.6% |

70.0% |

N.R |

3.3% |

66.3% |

|

Oman |

N.R |

N.R |

0.1% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

N.R |

58.3% |

N.R |

|

Qatar |

N.R |

1.1% |

0.8% |

0.6% |

N.R |

N.R |

N.R |

N.R |

|

Saudi Arabia |

83.3% |

7.6% |

48.3% |

92.3% |

30.0% |

23.5% |

29.9% |

30.7% |

| UAE | N.R | 0.3% | 0.7% | 4.2% | N.R | N.R | N.R | 3.0% |

GCC = Gulf Corporation Council; N.R = not reported; MRSA = methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; UAE = United Arab Emirates.

Results

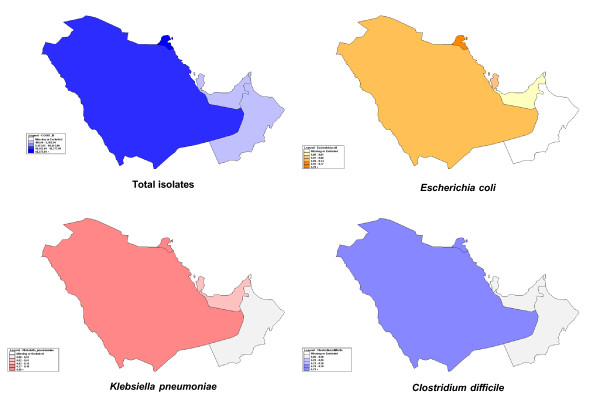

Between 1990 and April 2011, there were 45 articles published reviewing antibiotic resistance in GCC countries. Eleven articles were excluded because of their low number of isolates (n < 100) [35-45]. Thirty four articles were analyzed as they contained national data. Among all the GCC countries, 37,295 bacterial isolates were studied for antimicrobial resistance. The isolates were distributed as follows: Bahrain (2,841/7.6%), Kuwait (20,339/54.5%), Oman (882/2.4%), Qatar (570/1.5%), Saudi Arabia (12,174/32.6%) and UAE (491/1.3%); Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Geographical distributions of resistant isolates among GCC countries 1990–2011.

The most prevalent microorganism was Escherichia coli (10073, 44%), followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (4,709: 20%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (4,287/18.7%), MRSA (1,216: 5.4%), Acinetobacter (1,061/5%), with C. difficile and Enterococcus representing less than 1%.

Some national isolates showed high resistance than others. In Qatar, Khan, Elshafie et al. 2010, reported the occurrence of resistant Gram-negative organisms in 63.1% of bacteremia patients (n = 452) with the following prevalences: ESBL-resistant E coli (34%), followed by Klebsiella spp. (39/13.7%) and finally Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7.4%) [18]. Shigidi and his group found that Staphylococcus was most prevalent (29%), followed by E coli (9%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa was the least resistant with only 3% prevalence among dialysis patients in 2010 [7]. Their results, however, should be considered with caution because they tested relatively low number of cases (n = 118). A trend of MRSA infection in the burn center of the Sultanate of Oman was reported [16]. ESBL phenotypes were detected in more than 21% of the total isolates indicating their correlation with the resistance.

Conclusions

The geographical distributions of the resistance isolates during (1990–2011) in the gulf region were shown in Figure 1. The most prevalent reported microorganism with resistance data reported by GCC countries in the last 2 decades was E. coli, followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae and others. Multiple ESBL genes were identified, however, no carbapenamases were present and thus further work to identify the mechanism of resistance, such as c-di-GMP and others, is required. Many hospitals within the Kingdom have identified carbapenem resistance among enterobacteriaceae, and Oman has reported NDM-1 in Klebsiella isolates in 2010[17]. From our experience at KAMC in Riyadh, a 1000 bed hospital, we have identified for the first time carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae which led to an outbreak stemming from the adult ICU [46].

The emergence of antimicrobial resistance in GCC countries might have occurred for several reasons. One is the readily available broad spectrum antibiotics, such as 3rd and 4th generation cephalosporins, quinolones and carbapenems in the healthcare settings. Most GCC countries lack the presence of antimicrobial stewardship programs, especially in the inpatient setting where broad spectrum antimicrobial agents are used. Most hospitals’ architectural designs are old and many harbor 2 and 4 bedded rooms, which do not allow for proper isolation of infected and colonized patients with multi-drug resistant organisms. There a lack of strong infection control programs, properly trained infectious disease specialists and clinical pharmacists in the field of infectious diseases. In advanced healthcare systems, integrated computerized programs allowing for the restriction of antimicrobial agents and providing decision-assisted physician orders have proven to be helpful in controlling the use of antibiotics. Such alternatives may be expensive and not suitable for all healthcare settings. Further, highly skilled and dedicated information technology personnel are needed to support these systems. Finally, the lack of clinical pharmacists and infectious disease specialists may be a major contributor to the current emergence of resistance. Multidisciplinary teams including: infectious diseases, intensivists, surgeons, pulmonologists and emergency room specialists and clinical pharmacists may be needed to enhance utilization of antibiotics and play an important role in recommending the appropriate antimicrobial regimens and proper guidance on treatment and de-escalation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MA: acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the manuscript. HB: analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Mahmoud Aly, Email: alyma@ngha.med.sa.

Hanan H Balkhy, Email: balkhyh@ngha.med.sa.

References

- WHO. World Health Day – 7 April 2011"Antimicrobial resistance: no action today, no cure tomorrow". In Book World Health Day – 7 April 2011"Antimicrobial resistance: no action today, no cure tomorrow" (Editor ed.^eds.). City; 2011.

- Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:657–686. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.657-686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memish ZA, Ahmed QA, Arabi YM, Shibl AM, Niederman MS. Microbiology of community-acquired pneumonia in the Gulf Corporation Council states. J Chemother. 2007;19(Suppl 1):17–23. doi: 10.1080/1120009x.2007.11782430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindayna KM, Senok AC, Jamsheer AE. Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Bahrain. J Infect Public Health. 2009;2:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo EE, Panigrahi D, Jamsheer AE. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in a Bahrain hospital. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17:308–314. doi: 10.1159/000129611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace MR, Johnson AP, Daniel M, Malde M, Yousif AA. Sequential emergence of multi-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Bahrain. J Hosp Infect. 1995;31:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(95)90203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigidi MM, Fituri OM, Chandy SK, Asim M, Al Malki HA, Rashed AH. Microbial spectrum and outcome of peritoneal dialysis related peritonitis in Qatar. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21:168–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Benwan K, Al Sweih N, Rotimi VO. Etiology and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of community- and hospital-acquired urinary tract infections in a general hospital in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2010;19:440–446. doi: 10.1159/000320301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashti AA, Jadaon MM, Amyes SG. Retrospective study of an outbreak in a Kuwaiti hospital of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae possessing the new SHV-112 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase. J Chemother. 2010;22:335–338. doi: 10.1179/joc.2010.22.5.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal W, Rotimi VO, Brazier J, Duerden BI. Analysis of prevalence, risk factors and molecular epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection in Kuwait over a 3-year period. Anaerobe. 2010;16:560–565. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal WY, El-Din K, Rotimi VO, Chugh TD. An analysis of hospital-acquired bacteraemia in intensive care unit patients in a university hospital in Kuwait. J Hosp Infect. 1999;43:49–56. doi: 10.1053/jhin.1999.0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johny M, Babelly M, Al-Obaid I, Al-Benwan K, Udo EE. Antimicrobial resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in a tertiary hospital in Kuwait, 1997–2007: implications for empiric therapy. J Infect Public Health. 2010;3:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokaddas EM, Abdulla AA, Shati S, Rotimi VO. The technical aspects and clinical significance of detecting extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae at a tertiary-care hospital in Kuwait. J Chemother. 2008;20:445–451. doi: 10.1179/joc.2008.20.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotimi VO, Al-Sweih NA, Feteih J. The prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of gram-negative bacterial isolates in two ICUs in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;30:53–59. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(97)00180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotimi VO, Mokaddas EM, Jamal WY, Verghese TL, El-Din K, Junaid TA. Hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection amongst ICU and burn patients in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2002;11:23–28. doi: 10.1159/000048656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna M, Thomas C. A profile of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in the burn center of the Sultanate of Oman. Burns. 1998;24:631–636. doi: 10.1016/S0305-4179(98)00108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L, Al Maskari Z, Al Rashdi F, Bernabeu S, Nordmann P. NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in the Sultanate of Oman. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:304–306. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan FY, Elshafie SS, Almaslamani M, Abu-Khattab M, El Hiday AH, Errayes M, Almaslamani E. Epidemiology of bacteraemia in Hamad general hospital, Qatar: a one year hospital-based study. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2010;8:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S, Al-Juaid NF, Alenzi FQ, Mattar EH, Bakheet Oel S. Prevalence, antibiotic susceptibility pattern and production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases amongst clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae at Armed Forces Hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009;19:264–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhter J, Frayha HH, Qadri SM. Current status and changing trends of antimicrobial resistance in Saudi Arabia. J Med Liban. 2000;48:227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Johani SM, Akhter J, Balkhy H, El-Saed A, Younan M, Memish Z. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among gram-negative isolates in an adult intensive care unit at a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2010;30:364–369. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.67073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tawfiq JA, Abed MS. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of health care associated bloodstream infections at a general hospital in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:1213–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tawfiq JA, Abed MS. Clostridium difficile-associated disease among patients in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2010;8:373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tawfiq JA, Antony A. Antimicrobial resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Saudi Arabian hospital: results of a 6-year surveillance study, 1998–2003. J Infect Chemother. 2007;13:230–234. doi: 10.1007/s10156-007-0532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar AH, Faidah HS. Frequency and antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-negative bacteria isolated from 2 hospitals in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:1017–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babay HA. Antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients in a teaching hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2001–2005. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2007;60:123–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkhy HH, Cunningham G, Chew FK, Francis C, Al Nakhli DJ, Almuneef MA, Memish ZA. Hospital- and community-acquired infections: a point prevalence and risk factors survey in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkhy HH, Memish ZA, Shibl A, Elbashier A, Osoba A. In vitro activity of quinolones against S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11:36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilal NE, Gedebou M. Staphylococcus aureus as a paradigm of a persistent problem of bacterial multiple antibiotic resistance in Abha, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6:948–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouda SI, Kadry AA, Shibl AM. Beta-lactam and macrolide resistance and serotype distribution among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates from Saudi Arabia. J Chemother. 2004;16:517–523. doi: 10.1179/joc.2004.16.6.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memish ZA, Balkhy HH, Shibl AM, Barrozo CP, Gray GC. Streptococcus pneumoniae in Saudi Arabia: antibiotic resistance and serotypes of recent clinical isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;23:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2003.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibl AM, Al Rasheed AM, Elbashier AM, Osoba AO. Penicillin-resistant and -intermediate Streptococcus pneumoniae in Saudi Arabia. J Chemother. 2000;12:134–137. doi: 10.1179/joc.2000.12.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Muhairi S, Zoubeidi T, Ellis M, Nicholls MG, Safa W, Joseph J. Demographics and microbiological profile of pneumonia in United Arab Emirates. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2006;65:13–18. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2006.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zarouni M, Senok A, Rashid F, Al-Jesmi SM, Panigrahi D. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the United Arab Emirates. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17:32–36. doi: 10.1159/000109587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aly NY, Al-Mousa HH, Al Asar el SM. Nosocomial infections in a medical-surgical intensive care unit. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17:373–377. doi: 10.1159/000141500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babay HA, Twum-Danso K, Kambal AM, Al-Otaibi FE. Bloodstream infections in pediatric patients. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:1555–1561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang RL, Gang RK, Sanyal SC, Mokaddas E, Ebrahim MK. Burn septicaemia: an analysis of 79 patients. Burns. 1998;24:354–361. doi: 10.1016/S0305-4179(98)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukharie HA, Abdelhadi MS, Saeed IA, Rubaish AM, Larbi EB. Emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a community pathogen. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;40:1–4. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(01)00242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gang RK, Bang RL, Sanyal SC, Mokaddas E, Lari AR. Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicaemia in burns. Burns. 1999;25:611–616. doi: 10.1016/S0305-4179(99)00042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumaa PA, Neringer R. A survey of antimicrobial resistance in a tertiary referral hospital in the United Arab Emirates. J Chemother. 2005;17:376–379. doi: 10.1179/joc.2005.17.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kader AA, Kumar A. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in a general hospital. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:239–242. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2005.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narchi H, Al-Hamdan MA. Antibiotic resistance trends in paediatric community-acquired first urinary tract infections in the United Arab Emirates. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nzeako BC, Al Daughari H, Al Lamki Z, Al Rawas O. Nature of bacteria found on some wards in Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Oman. Br J Biomed Sci. 2006;63:55–58. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2006.11732720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamseldin el Shafie S, Smith W, Donnelly G. An outbreak of gentamicin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a neonatal ward. Cent Eur J Public Health. 1995;3:129–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo EE, Al-Sweih N, Phillips OA, Chugh TD. Species prevalence and antibacterial resistance of enterococci isolated in Kuwait hospitals. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:163–168. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.04949-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkhy H, El-Saed A, Al Johani S, Tayeb H, Al-Qahtani A, Alahdal M, Sallah M, Alothman A, Alarabi Y. Epidemiology of the first outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Saudi Arabia. BMC Proceedings. 2011;5:P295. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S6-P295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]