Abstract

MenE, the o-succinylbenzoate (OSB)-CoA synthetase from bacterial menaquinone biosynthesis, is a promising new antibacterial target. Sulfonyladenosine analogues of the cognate reaction intermediate, OSB-AMP, have been developed as inhibitors of the MenE enzymes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (mtMenE), Staphylococcus aureus (saMenE) and Escherichia coli (ecMenE). Both a free carboxylate and ketone moiety on the OSB side chain are required for potent inhibitory activity. OSB-AMS (4) is a competitive inhibitor of mtMenE with respect to ATP (Ki = 5.4 ± 0.1 nM) and a non-competitive inhibitor with respect to OSB (Ki = 11.2 ± 0.9 nM). These data are consistent with a bi uni uni bi ping-pong kinetic mechanism for these enzymes. In addition, OSB-AMS inhibits saMenE with of 22 ± 8 nM and ecMenE with . Putative active site residues, Arg-222, which may interact with the OSB aromatic carboxylate, and Ser-302, which may bind the OSB ketone oxygen, have been identified through computational docking of OSB-AMP with the unliganded crystal structure of saMenE. A pH-dependent interconversion of the free keto acid and lactol forms of the inhibitors is also described, along with implications for inhibitor design.

Keywords: adenylation, inhibitors, docking, drug design, antibiotics

Introduction

New antibiotics are urgently needed to combat the growing threat of drug-resistant bacterial infections.[1–6] To address this need, antibiotics that act by novel mechanisms must be developed. In this vein, bacterial menaquinone biosynthesis has emerged as a promising new antibacterial target.[7–9] Menaquinone is a lipid-soluble electron carrier that is used in the electron transport chain of cellular respiration (Scheme 1).[10–12] While humans and some bacteria use the alternative redox cofactor ubiquinone, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, most Gram-positive bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus, and some Gram-negative bacteria rely solely on menaquinone. Although menaquinone is also used in the mammalian blood clotting cascade, humans lack the de novo biosynthetic pathway,[13] and obtain it from diet or intestinal bacteria. Thus, menaquinone biosynthesis inhibitors should be highly selective for bacteria over the human host.

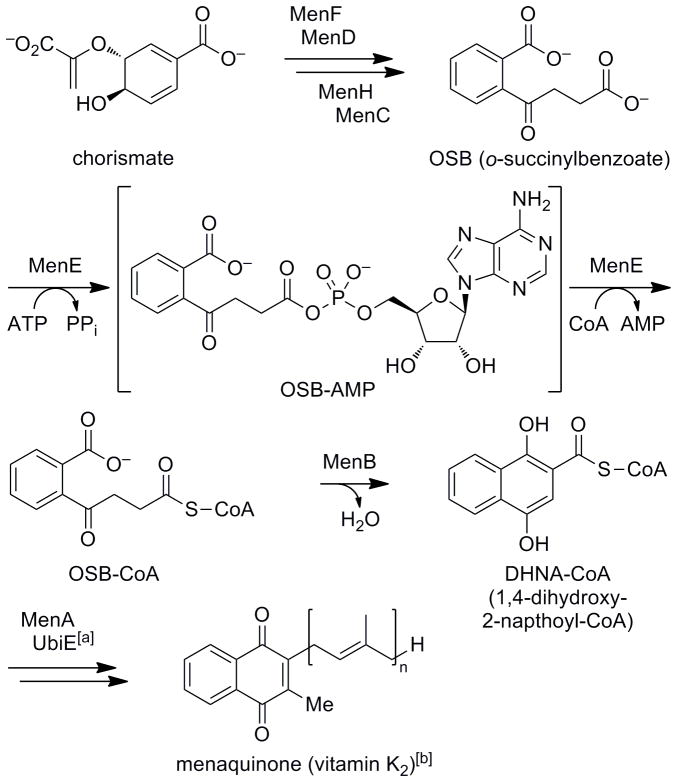

Scheme 1.

The o-succinylbenzoate (OSB)-CoA synthetase MenE catalyzes two half-reactions involving a tightly-bound OSB-AMP intermediate during menaquinone biosynthesis. [a] A third, as yet unidentified enzyme is thought to be involved in the conversion of 1,4-dihydroxy-2-napthoyl (DHNA)-CoA to menaquinone. [b] n = 4–13; n = 9 in M. tuberculosis; n = 8 in S. aureus, E. coli.

Menaquinone is biosynthesized from chorismate by a series of at least eight enzymes (Scheme 1).[14–16] The fifth of these is the acyl-CoA synthetase MenE, which carries out a two-step process involving initial activation of o-succinylbenzoate (OSB) by adenylation to form a tightly-bound OSB-AMP intermediate, followed by attack of CoA to form a thioester product.[17–19] MenE is essential in M. tuberculosis,[20] and designed inhibitors of another menaquinone biosynthesis enzyme, MenA, have potent activity against multidrug-resistant M. tuberculosis and Gram-positive bacteria.[21] In that vein, however, a human homologue of MenA that converts plant phylloquinone to menaquinone has been identified recently.[22] Menaquinone is also essential in E. coli,[23] and mutations in biosynthesis genes are associated with a slow growth phenotype in S. aureus.[24–26] In addition to the classical pathway, an alternative (futalosine) biosynthetic pathway has been identified in certain bacteria,[27–29] but the two pathways appear to be mutually exclusive in distribution, and there is no evidence for the presence of this alternative pathway in M. tuberculosis or S. aureus.[27,29] Thus, MenE is an attractive target for blocking menaquinone biosynthesis as a new antibacterial strategy. Further, since non-replicating M. tuberculosis must respire, inhibitors may also be active against latent tuberculosis infections, which affect an estimated one-third of the global population.[3]

Acyl-CoA synthetases belong to the ANL (Acyl-CoA synthetase, Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase adenylation domains, firefly Luciferase) family of adenylate-forming enzymes, which share the same overall fold.[30] This family is, in turn, part of a larger mechanistic superfamily of enzymes that catalyze adenylation of carboxylic acid substrates and subsequent coupling to sulfur, oxygen, or nitrogen nucleophiles. This superfamily includes Class I and Class II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases,[31,32] E1 activating enzymes,[33–35] N-type ATP pyrophosphatases,[36–38] and recently discovered amide ligases.[39,40]

A variety of inhibitors of this mechanistic superfamily have been reported previously, most of which are designed to mimic the acyl-AMP intermediate.[41] In particular, acyl sulfonyladenosines, pioneered by Ishida[42] and inspired by sulfamoyladenosine natural products such as nucleocidin and ascamycin,[43–46] have been investigated extensively as aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitors.[47–50] Such inhibitors have now been applied widely to other enzymes in this mechanistic superfamily, including members of the ANL family,[51–62] E1 activating enzymes,[63–65] asparagine synthetase,[66] and pantothenate synthetase.[67] In addition, electrophilic vinyl sulfonamide inhibitors have been designed to trap the incoming nucleophile in the second half-reaction catalyzed by these enzymes,[63,64,68] leveraging design strategies originally developed to target cysteine proteases.[69,70]

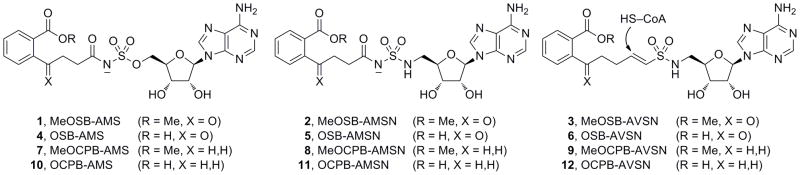

Our laboratories recently used these inhibitor design strategies to develop several sulfonyladenosine-type inhibitors of the acyl-CoA synthetase MenE (Scheme 2).[71] Two of these inhibitors mimic the cognate OSB-AMP reaction intermediate by replacing the reactive phosphate moiety with stable sulfamate (1) or sulfamide (2) moieties. The third inhibitor is designed to trap the incoming CoA thiol nucleophile with a vinyl sulfonamide electrophile (3).

Scheme 2.

MenE inhibitors designed to mimic the OSB-AMP intermediate (AMS, AMSN) or to trap the CoA thiol nucleophile (AVSN). (MeOSB = methyl o-succinylbenzoate; MeOCPB = methyl o-[3-carboxypropyl]benzoate; OSB = o-succinylbenzoate; OCPB = o-[3-carboxypropyl]benzoate).

In these inhibitors, the aromatic carboxylate moiety of OSB was masked as the corresponding methyl ester. Concurrently, Mesecar and coworkers reported a related MenE inhibitor in which the aromatic carboxylate was replaced with a trifluoromethyl group.[72] While both of these modifications were tolerated, the resulting inhibitors exhibited relatively modest, low to mid-μM potency.

To evaluate the importance of the aromatic carboxylate to MenE recognition, we sought to evaluate the corresponding carboxylate analogues of our sulfonyladenosine-type inhibitors. We report herein the synthesis and evaluation of these inhibitors and several related analogues, the discovery of a pH-dependent equilibrium between isomeric forms, and the implications for future inhibitor designs targeting MenE and menaquinone biosynthesis.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of OSB-AMP Analogues

The carboxylate-containing inhibitors 4 (OSB-AMS), 5 (OSB-AMSN), and 6 (OSB-AVSN) (Scheme 2) were readily synthesized by selective saponification of the methyl esters in 1–3, respectively (NaOH, MeOH, rt), which were prepared as previously described[71] (see Supporting Information for full details).

In our initial report, we investigated the importance of the OSB ketone moiety by replacing it with a methylene group (X = CH2, not shown).[71] None of these compounds inhibited MenE when tested at up to 200 μM concentration, and it is possible that this substitution either disrupts a hydrogen-bonding interaction or introduces steric conflicts in the active site. Thus, to investigate further the role of the ketone functionality, we also sought to synthesize the corresponding desketo analogues 7–12 (X = H,H).

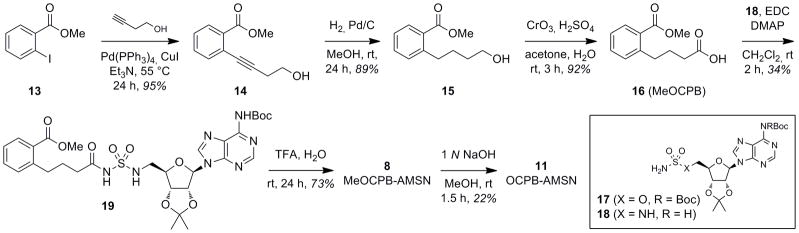

The requisite o-(carboxypropyl)benzoate (OCPB) sidechain 16 was synthesized from iodobenzoate 13 by Sonogashira cross-coupling,[73] alkyne hydrogenation, and Jones oxidation[74] (Scheme 3). Coupling to protected 5′-O-sulfamoyladenosine 17[59] was successful, but after TFA deprotection, the final acyl sulfamate product 7 (MeOCPB-AMS) proved to be hydrolytically unstable at the acyl sulfamate moiety and could not be purified sufficiently. Thus, 7 and the corresponding free carboxylate 10 (OCPB-AMS) were not pursued further. In contrast, coupling of 16 to the related sulfamide 18[71] and deprotection afforded the acyl sulfamide 8 (MeOCPB-AMSN), which proved to be stable and could also be converted to the free carboxylate 11 (OCPB-AMSN) by selective hydrolysis of the methyl ester.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of o-(carboxypropyl)benzoate (OCPB) sidechain and des-keto inhibitors 8, 11.

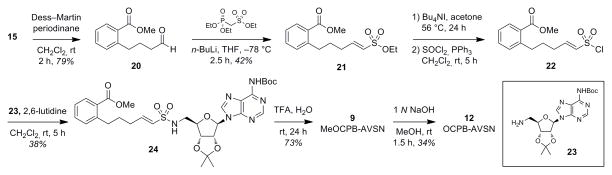

To access the corresponding vinyl sulfonamide analogues, alcohol 15 underwent Dess–Martin oxidation to aldehyde 20,[75,76] followed by Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reaction with a diethyl-phosphorylmethanesulfonate reagent developed by Ghosez to afford the vinyl sulfonate 21 (Scheme 4).[77,78] Selective cleavage of the sulfonate ester followed by chlorination provided vinyl sulfonylchloride 22, which was used without further purification and coupled to protected 5′-aminodeoxyadenosine 23.[55,71] TFA deprotection afforded methyl ester 9 (MeOCPB-AVSN), and saponification of the ester yielded free carboxylate 12 (OCPB-AVSN).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of vinyl sulfonyl chloride sidechain and des-keto inhibitors 9, 12.

Inhibition of MenE

With these compounds in hand, we tested their inhibitory activities against MenE from M. tuberculosis (mtMenE), S. aureus (saMenE), and E. coli (ecMenE) using coupled assays with MenB, the next downstream enzyme in the menaquinone biosynthesis pathway (Scheme 1).[8,71,79] This coupled assay is based on that described earlier for evaluating the inhibition of MenB, except that the concentrations of MenE and MenB are adjusted to ensure that the MenE-catalyzed reaction is rate-limiting. Assays for saMenE and mtMenE utilized M. tuberculosis MenB (mtMenB) as the coupling enzyme, while ecMenE was assayed with E. coli MenB (ecMenB). ecMenE, ecMenB, and mtMenB were expressed and purified as described previously,[8,79] while saMenE and mtMenE were cloned and expressed with N-terminal His6-tags in E. coli (BL21) cells, then purified to homogeneity using nickel affinity chromatography (see Supporting Information for full details). Reactions were initiated by adding MenE (final concentration 50–100 nM) to a solution containing MenB (5–10μM), ATP (240 μM), CoA (240 μM), OSB (120–240 μM) and inhibitor (0–200 μM). Formation of DHNA-CoA was monitored at 392 nm, and IC50 values were determined by fitting the initial velocity data to the standard dose response equation (Table 1).[71]

Table 1.

Inhibition of the MenE enzymes from M. tuberculosis, S. aureus, and E. coli[a]

| Inhibitor |

M. tuberculosis MenE IC50 (μM) |

S. aureus MenE IC50 (μM) |

E. coli MenE IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1, MeOSB-AMS | 14.2 ± 3.3 | 24.6 ± 3.5 | 38.0 ± 3.0[b] |

| 2, MeOSB-AMSN | 23.5 ±1.0 | >200 | 34.1 ± 2.8[b] |

| 3, MeOSB-AVSN | 117 ± 12 | 45.7 ± 2.8 | 5.7 ± 0.7[b] |

| 4, OSB-AMS | 0.049 ± 0.007[c] | 0.060 ± 0.005[d] | 0.21 ± 0.16[e] |

| 5, OSB-AMSN | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.63 ± 0.14 |

| 6, OSB-AVSN | 0.16 ± 0.05 | 0.33 ± 0.05 | 0.57 ± 0.06 |

| 8, MeOCPB-AMSN | >200 | >200 | >200 |

| 9, MeOCPB-AVSN | >200 | >200 | >200 |

| 11, OCPB-AMSN | 101 ± 14 | 85 ± 17 | n.d.[f] |

| 12, OCPB-AVSN | 106 ± 10 | 54.4 ± 2.3 | 31.6 ± 5.5 |

Assays were performed with 50 nM mtMenE, 100 nM saMenE or 100 nM ecMenE.

Data from ref. [71].

Competitive inhibitor with respect to ATP (Ki = 5.4 ± 0.1 nM) and noncompetitive inhibitor with respect to OSB (Ki = 11.2 ± 0.9 nM).

.

Competitive inhibitor with respect to OSB (Ki = 128 ± 5 nM).

n.d. = not determined.

We were gratified to find that the free carboxylate analogues 4–6 proved to be excellent inhibitors of all three enzymes (Table 1), and were more potent than the original methyl ester analogues 1–3. Notably, the sulfamate 4 (OSB-AMS) was the most potent inhibitor in the carboxylate series for all three enzymes, in contrast to the mixed structure–activity relationship trends observed for the methyl ester series.[71] Further, while neither of the desketo methyl ester analogues 8 or 9 exhibited appreciable activity, the corresponding desketo carboxylates 11 and 12 were moderate inhibitors. Thus, deletion of the OSB ketone functionality appears to result in decreased inhibitory activity by approximately 2–3 orders of magnitude (5 vs. 11, 6 vs. 12)

The IC50 values for the inhibition of M. tuberculosis mtMenE, saMenE and ecMenE by 4 (OSB-AMS) are within a factor of 2–3 of the enzyme concentrations used in the assay, thus meeting the experimental criterion for tight-binding inhibitors.[80] To provide additional information on the mechanism of enzyme inhibition, values were determined using the Morrison equation[81,82] as a function of substrate concentration to provide the absolute Ki values for enzyme inhibition. Sulfamate 4 was found to be a competitive inhibitor of mtMenE with respect to ATP (Ki = 5.4 ± 0.1 nM) and a noncompetitive inhibitor with respect to OSB (Ki = 11.2 ± 0.9 nM). These data are consistent with the knowledge that mtMenE follows a bi uni uni bi ping-pong kinetic mechanism in which the addition of ATP and OSB is ordered, with ATP binding first (data not shown). A similar experiment demonstrated that 4 is a competitive inhibitor of ecMenE with respect to OSB with a Ki value 128 ± 5 nM), consistent with the knowledge that OSB binds first to ecMenE (data not shown). Such a mechanism is consistent with studies on other ligase enzymes.[72,83,84] Although the dependence of on substrate concentration was not determined for the inhibition of saMenE by 4, fitting the IC50 data to the Morrison equation gave a value for of 22 ± 8 nM.

Active Site Recognition of OSB-AMP and MenE Inhibitors

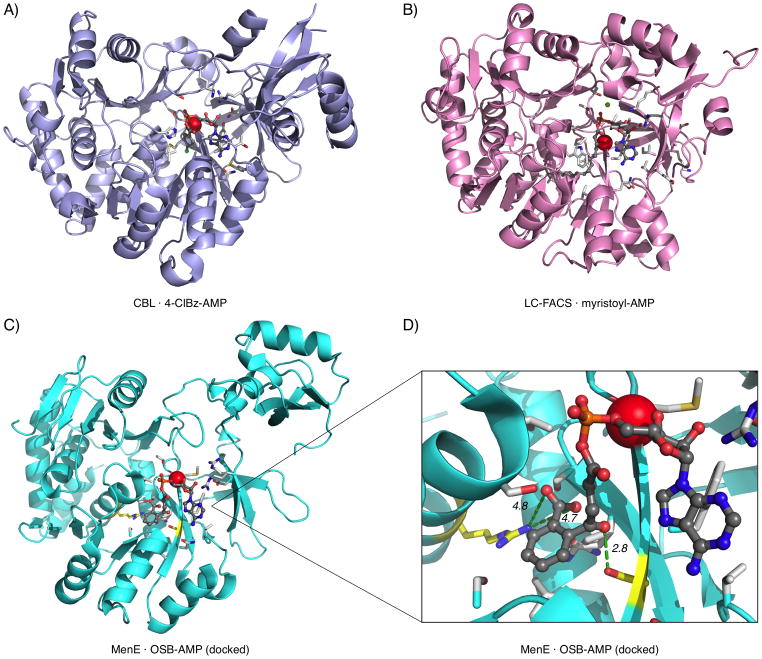

The increased potency of the aromatic carboxylate analogues 4–6 compared to all previously reported MenE inhibitors suggests that the OSB carboxylate functionality may be recognized specifically by one or more basic sidechains in the active site. While cocrystal structures of MenE with substrates or inhibitors have not yet been reported, a crystal structure of the unliganded form of saMenE (PDB ID: 3IPL) has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank by the New York Structural Genomics Research Center.[87] We identified the putative active site in saMenE by comparison to two other acyl-CoA synthetases that have been crystallized with their cognate acyl-AMP intermediates bound (Figure 1).[85,86] This binding site is also conserved across other members of the ANL family.[30,88–93] Upon examination of residues within 12 Å of the center of this binding pocket, we identified a basic residue, Arg-222, that may interact with the aromatic carboxylate of OSB (Supplementary Figure S1a, b). Notably, this residue was not readily identified in sequence alignments guided by the other acyl-CoA synthetase structures, because it lies one extra turn toward the C-terminus of helix B3/4 compared to binding pocket residues in the previously-determined structures (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Active sites of acyl-CoA synthetases. A) 4-Chlorobenzoate-CoA synthetase (CBL) with 4-chlorobenzoyl-AMP intermediate and substrate binding residues (PDB: 3CW8).[85] B) Long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase (LC-FACS) with myristoyl-AMP intermediate and substrate binding residues (portions of structure not shown for clarity) (PDB: 1V26).[86] C) S. aureus MenE unliganded form with OSB-AMP docked in the putative active site (loop residues 280–284 not shown for clarity) (PDB: 3IPL).[87] D) Arg-222 and Ser-302 (yellow) and putative interactions with OSB aromatic carboxylate (4.7, 4.8 Å) and OSB ketone oxygen (2.8 Å), respectively (loop residues 280–284 not shown for clarity). Sidechains within 4 Å of ligands (white) and C-terminus of helix B3/4 (red sphere) are shown in each case.

To evaluate this hypothesis, AutoDock 3.05[94] was used to generate an enzyme–ligand complex of OSB-AMP bound to saMenE. Importantly, the OSB carboxylate is within 5 Å of Arg-222 in this docked structure. Similarly, when OSB alone is docked into the active site, it places the aromatic carboxylate within 3 Å of Arg-222 (Supplementary Figure S1c, d). In addition, Ser-302 is within 3 Å of the OSB ketone oxygen in both docked structures, suggesting a possible hydrogen-bonding interaction. This is consistent with the decreased inhibitory activity observed for both the desketo analogues 8, 9, 11, and 12 herein and the previously described methylene analogues.[71]

Keto Acid–Lactol Equilibrium in MenE Inhibitors

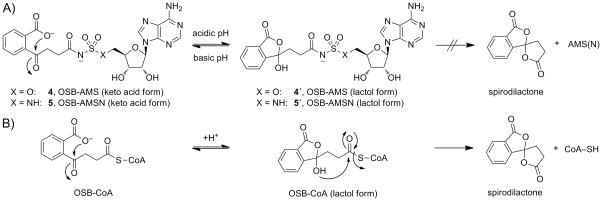

Interestingly, during the synthesis of carboxylates 4–6, we noted distinct NMR spectra after purification by normal phase silica flash chromatography (MeOH/EtOAc) compared to purification by reverse phase HPLC (CH3CN/H2O, 0.1% TFA). We determined that the former corresponded to the free keto acid form of the OSB sidechain while the latter corresponded to the lactol form (Scheme 5; see Supporting Information for full details). These isomeric forms could be interconverted reversibly in CD3OD by treatment with Na2CO3 (keto acid) or TFA (lactol). This raised the possibility that either isomeric form could be the active pharmacophore in these inhibitors.

Scheme 5.

A) Lactol formation in OSB-AMS (4,4′) and OSB-AMSN (5,5′). B) Decomposition of OSB-CoA to form a spirodilactone.

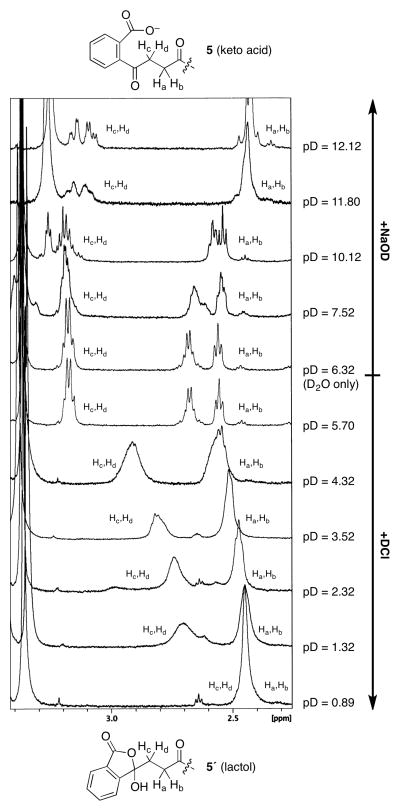

Subsequently, we evaluated the pH-dependence of the equilibrium by 1H-NMR analysis of 5 (OSB-AMSN) in D2O (Figure 2). Most notably, the ketone α-protons were observed at ≈3.2 ppm at pD ≥ 5.70 (keto acid form) and at ≈2.45 ppm at pD 0.89 (lactol form). The intermediate chemical shifts observed at intermediate pD values (1.32–4.32) are presumed to arise from rapid equilibration of the two isomers on the NMR timescale. An additional upfield shift of both the ketone α-protons and acyl sulfamide α-protons above pD 10.12 may be attributed to deprotonation of the adenosine 5′-nitrogen (not shown).

Figure 2.

pH-Dependence of keto acid–lactol equilibrium in OSB-AMSN (5), as determined by 1H-NMR in D2O. The isomeric forms (5,5′) are presumed to be in equilibrium on the NMR timescale between pD 4.32–1.32, based on the intermediate chemical shift of OSB sidechain protons Hc,Hd. The additional upfield shift of both Ha,Hb and Hc,Hd above pD 10.12 is presumed to be due to deprotonation of the adenosine 5′-nitrogen.

Thus, it is possible that the OSB aromatic carboxylate is important for potent MenE inhibition because the lactol form, formed in solution or in the enzyme active site, is actually the active pharmacophore. While the presence and orientation of Arg-222 in the unliganded structure certainly suggest that the keto acid form is the likely pharmacophore, the importance of the lactol form cannot yet be ruled out, since hydrogen-bonding of the ketone oxygen to Ser-302 may favor the lactol form. Indeed, the dramatically decreased inhibitory activity of the desketo analogues 11 and 12 is consistent with either scenario, since lactol formation is precluded in these structures.

Finally, it is interesting to note that the native MenE reaction product, OSB-CoA, is known to undergo spontaneous decomposition through the formation of a spirodilactone (Scheme 5).[17,95] In contrast, 4 (OSB-AMS) and 5 (OSB-AMSN) can also undergo the first step in this pathway to generate the lactol forms 4′ and 5′, but do not proceed further to spirodilactone formation via displacement of the sulfonyladenosine motif. Thus, even if the lactol form proves not to be relevant to MenE binding, inhibitors based on this structure may have utility as prodrugs in which the negatively charged carboxylate is masked in the lactol form.

Conclusion

We have compared the inhibitory activities of several series of sulfonyladenosine-based MenE inhibitors designed to probe structure–activity relationships in the OSB motif. In these inhibitors, both the free carboxylate and the ketone moiety on the OSB side chain are required for potent inhibition. Analysis of the crystal structure of unliganded saMenE and docking of OSB-AMP into this structure suggest that Arg-222 may interact with the OSB carboxylate and Ser-302 may bind the OSB ketone, providing a rationale for the increased potency of these inhibitors compared to previously described analogues. The discovery of a stable, isomeric lactol form of these inhibitors may have important implications for the design of additional inhibitors and prodrug variants in the future.

Experimental Section

See Supporting Information for complete experimental procedures and spectral data for all new compounds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Caroline Kisker (Rudolph Virchow Center) for a kind gift of the codon-optimized gene for mtMenE, Dr. George Sukenick, Dr. Hui Liu, Hui Fang, and Dr. Sylvi Rusli (MSKCC Analytical Core Facility) for expert mass spectral analyses, and Dr. Debarshi Pratihar (MSKCC) for assistance with chemical sample analysis. D.S.T. is an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow. Financial support from the NIH (R01 AI068038 to D.S.T.; R01 AI044639 and R21 AI058785 to P.J.T.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Dedicated to the memory of our colleague and mentor, Prof. David Y. Gin (1967–2011).

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chembiochem.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Prof. Peter J. Tonge, Email: peter.tonge@sunysb.edu.

Prof. Derek S. Tan, Email: tand@mskcc.org.

References

- 1.Davies J, Davies D. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74:417–433. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silver LL. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:71–109. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00030-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koul A, Arnoult E, Lounis N, Guillemont J, Andries K. Nature. 2011;469:483–490. doi: 10.1038/nature09657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simmons KJ, Chopra I, Fishwick CWG. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:501–510. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Science. 2009;325:1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1176667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Payne DJ, Gwynn MN, Holmes DJ, Pompliano DL. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:29–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meganathan R. In: Comprehensive Natural Products II: Chemistry and Biology, Vol. 7: Cofactors. Begley TP, Mander L, Liu HWB, editors. Elsevier; 2010. pp. 411–444. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Truglio JJ, Theis K, Feng Y, Gajda R, Machutta C, Tonge PJ, Kisker C. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42352–42360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurosu M, Begari E. Molecules. 2010;15:1531–1553. doi: 10.3390/molecules15031531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bishop DHL, Pandya KP, King HK. Biochem J. 1962;83:606–614. doi: 10.1042/bj0830606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins MD, Jones D. Microbiol Rev. 1981;45:316–354. doi: 10.1128/mr.45.2.316-354.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lester RL, Crane FL. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:2169–2175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dowd P, Ham SW, Naganathan S, Hershline R. Annu Rev Nutr. 1995;15:419–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.15.070195.002223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Begley TP, Kinsland C, Taylor S, Tandon M, Nicewonger R, Wu M, Chiu HJ, Kelleher N, Campobasso N, Zhang Y. Topics Curr Chem. 1998;195:93–142. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meganathan R. Vitam Horm. 2001;61:173–218. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(01)61006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang M, Chen X, Guo ZF, Cao Y, Chen M, Guo Z. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3426–3434. doi: 10.1021/bi7023755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meganathan R, Bentley R. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:92–98. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.1.92-98.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sieweke HJ, Leistner E. Z Naturforsch, C: Biosci. 1991;46:585–590. doi: 10.1515/znc-1991-7-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon O, Bhattacharyya DK, Meganathan R. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6778–6781. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6778-6781.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurosu M, Narayanasamy P, Biswas K, Dhiman R, Crick DC. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3973–3975. doi: 10.1021/jm070638m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakagawa K, Hirota Y, Sawada N, Yuge N, Watanabe M, Uchino Y, Okuda N, Shimomura Y, Suhara Y, Okano T. Nature. 2010;468:117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature09464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guest JR. J Bacteriol. 1977;130:1038–1046. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.3.1038-1046.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Eiff C, McNamara P, Becker K, Bates D, Lei XH, Ziman M, Bochner BR, Peters G, Proctor RA. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:687–693. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.687-693.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lannergard J, von Eiff C, Sander G, Cordes T, Seggewiss J, Peters G, Proctor Richard A, Becker K, Hughes D. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:4017–4022. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00668-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohler C, von Eiff C, Liebeke M, McNamara PJ, Lalk M, Proctor RA, Hecker M, Engelmann S. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6351–6364. doi: 10.1128/JB.00505-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiratsuka T, Furihata K, Ishikawa J, Yamashita H, Itoh N, Seto H, Dairi T. Science. 2008;321:1670–1673. doi: 10.1126/science.1160446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seto H, Jinnai Y, Hiratsuka T, Fukawa M, Furihata K, Itoh N, Dairi T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5614–5615. doi: 10.1021/ja710207s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dairi T. J Antibiot. 2009;62:347–352. doi: 10.1038/ja.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gulick AM. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:811–827. doi: 10.1021/cb900156h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibba M, Soll D. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:617–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Pouplana LR, Schimmel P. Cell. 2001;104:191–193. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulman BA, Harper JW. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:319–331. doi: 10.1038/nrm2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Capili AD, Lima CD. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:726–735. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dye BT, Schulman BA. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2007;36:131–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller MT, Bachmann BO, Townsend CA, Rosenzweig AC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14752–14757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232361199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller MT, Gerratana B, Stapon A, Townsend CA, Rosenzweig AC. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40996–41002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larsen TM, Boehlein SK, Schuster SM, Richards NGJ, Thoden JB, Holden HM, Rayment I. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16146–16157. doi: 10.1021/bi9915768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Challis GL. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:601–611. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hollenhorst MA, Clardy J, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10467–10472. doi: 10.1021/bi9013165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cisar JS, Tan DS. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1320–1329. doi: 10.1039/b702780j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ueda H, Shoku Y, Hayashi N, Mitsunaga J, In Y, Doi M, Inoue M, Ishida T. Biochim Biophys Acta, Prot Struct, Mol Enzymol. 1991;1080:126–134. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(91)90138-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Isono K, Uramoto M, Kusakabe H, Miyata N, Koyama T, Ubukata M, Sethi SK, McCloskey JA. J Antibiot. 1984;37:670–672. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osada H, Isono K. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:230–233. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waller CW, Patrick JB, Fulmor W, Meyer WE. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:1011–1012. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takahashi E, Beppu T. J Antibiot. 1982;35:939–947. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ochsner UA, Sun X, Jarvis T, Critchley I, Janjic N. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2007;16:573–593. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.5.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hurdle JG, O’Neill AJ, Chopra I. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4821–4833. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.4821-4833.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim S, Lee SW, Choi EC, Choi SY. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;61:278–288. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schimmel P, Tao J, Hill J. FASEB J. 1998;12:1599–1609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finking R, Neumueller A, Solsbacher J, Konz D, Kretzschmar G, Schweitzer M, Krumm T, Marahiel MA. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:903–906. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.May JJ, Finking R, Wiegeshoff F, Weber TT, Bandur N, Koert U, Marahiel MA. FEBS J. 2005;272:2993–3003. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Branchini BR, Murtiashaw MH, Carmody JN, Mygatt EE, Southworth TL. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:3860–3864. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.05.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferreras JA, Ryu JS, Di Lello F, Tan DS, Quadri LEN. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:29–32. doi: 10.1038/nchembio706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Somu RV, Boshoff H, Qiao C, Bennett EM, Barry CE, III, Aldrich CC. J Med Chem. 2006;49:31–34. doi: 10.1021/jm051060o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miethke M, Bisseret P, Beckering CL, Vignard D, Eustache J, Marahiel MA. FEBS J. 2006;273:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Callahan BP, Lomino JV, Wolfenden R. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:3802–3805. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pfleger BF, Lee JY, Somu RV, Aldrich CC, Hanna PC, Sherman DH. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4147–4157. doi: 10.1021/bi6023995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ferreras JA, Stirrett KL, Lu X, Ryu JS, Soll CE, Tan DS, Quadri LEN. Chem Biol. 2008;15:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Drake EJ, Duckworth BP, Neres J, Aldrich CC, Gulick AM. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9292–9305. doi: 10.1021/bi101226n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sikora AL, Wilson DJ, Aldrich CC, Blanchard JS. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3648–3657. doi: 10.1021/bi100350c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arora P, Goyal A, Natarajan VT, Rajakumara E, Verma P, Gupta R, Yousuf M, Trivedi OA, Mohanty D, Tyagi A, Sankaranarayanan R, Gokhale RS. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:166–173. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu X, Olsen SK, Capili AD, Cisar JS, Lima CD, Tan DS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1748–1749. doi: 10.1021/ja9088549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olsen SK, Capili AD, Lu X, Tan DS, Lima CD. Nature. 2010;463:906–912. doi: 10.1038/nature08765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brownell JE, Sintchak MD, Gavin JM, Liao H, Bruzzese FJ, Bump NJ, Soucy TA, Milhollen MA, Yang X, Burkhardt AL, Ma J, Loke HK, Lingaraj T, Wu D, Hamman KB, Spelman JJ, Cullis CA, Langston SP, Vyskocil S, Sells TB, Mallender WD, Visiers I, Li P, Claiborne CF, Rolfe M, Bolen JB, Dick LR. Mol Cell. 2010;37:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koroniak L, Ciustea M, Gutierrez JA, Richards NGJ. Org Lett. 2003;5:2033–2036. doi: 10.1021/ol034212n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ciulli A, Scott DE, Ando M, Reyes F, Saldanha SA, Tuck KL, Chirgadze DY, Blundell TL, Abell C. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:2606–2611. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qiao C, Wilson DJ, Bennett EM, Aldrich CC. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6350–6351. doi: 10.1021/ja069201e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Santos MMM, Moreira R. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2007;7:1040–1050. doi: 10.2174/138955707782110105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reddick JJ, Cheng J, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2003;5:1967–1970. doi: 10.1021/ol034555l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu X, Zhang H, Tonge PJ, Tan DS. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5963–5966. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tian Y, Suk DH, Cai F, Crich D, Mesecar AD. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12434–12447. doi: 10.1021/bi801311d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sonogashira K, Tohda Y, Hagihara N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975:4467–4470. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bowden K, Heilbron IM, Jones ERH, Weedon BCL. J Chem Soc. 1946:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dess DB, Martin JC. J Org Chem. 1983;48:4155–4156. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ireland RE, Liu L. J Org Chem. 1993;58:2899. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carretero JC, Demillequand M, Ghosez L. Tetrahedron. 1987;43:5125–5134. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carretero JC, Ghosez L. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:1101–1104. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li X, Liu N, Zhang H, Knudson SE, Li HJ, Lai CTJ, Slayden RA, Tonge PJ. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2011;2:818–823. doi: 10.1021/ml200141e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Copeland RA. Enzymes: A practical introduction to structure, mechanism, and data analysis. 2. Wiley-VCH, Inc. Publications; New York: 2000. pp. 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Morrison JF. Biochim Biophys Acta, Enzymol. 1969;185:269–286. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams JW, Morrison JF. Methods Enzymol. 1979;63:437–467. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)63019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zheng R, Blanchard JS. Biochemistry. 2001;40:12904–12912. doi: 10.1021/bi011522+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu R, Cao J, Lu X, Reger AS, Gulick AM, Dunaway-Mariano D. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8026–8039. doi: 10.1021/bi800698m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Reger AS, Wu R, Dunaway-Mariano D, Gulick AM. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8016–8025. doi: 10.1021/bi800696y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hisanaga Y, Ago H, Nakagawa N, Hamada K, Ida K, Yamamoto M, Hori T, Arii Y, Sugahara M, Kuramitsu S, Yokoyama S, Miyano M. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31717–31726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Patskovsky Y, Toro R, Dickey M, Sauder JM, Chang S, Burley SK, Almo SC. Protein Data Bank, Structure ID: 3IPL. Aug 25, 2009. doi: 10.2210/pdb3ipl/pdb. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Conti E, Stachelhaus T, Marahiel MA, Brick P. EMBO J. 1997;16:4174–4183. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.May JJ, Kessler N, Marahiel MA, Stubbs MT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12120–12125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182156699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jogl G, Tong L. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1425–1431. doi: 10.1021/bi035911a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nakatsu T, Ichiyama S, Hiratake J, Saldanha A, Kobashi N, Sakata K, Kato H. Nature. 2006;440:372–376. doi: 10.1038/nature04542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Du L, He Y, Luo Y. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11473–11480. doi: 10.1021/bi801363b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yonus H, Neumann P, Zimmermann S, May JJ, Marahiel MA, Stubbs MT. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32484–32491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. J Computat Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kolkmann R, Leistner E. Z Naturforsch, C: J Biosci. 1987;42:542–552. doi: 10.1515/znc-1987-11-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.