Abstract

Cognitive impairments are now widely acknowledged as an important aspect of major depressive disorder (MDD), and it has been proposed that executive function (EF) may be particularly impaired in patients with MDD. However, the existence and nature of EF impairments associated with depression remain strongly debated. While many studies have found significant deficits associated with MDD on neuropsychological measures of EF, others have not, potentially due to low statistical power, task impurity, and diverse patient samples, and there have been no recent, comprehensive, meta-analyses investigating EF in patients with MDD. The current meta-analysis uses random effects models to synthesize 113 previous research studies that compared participants with MDD to healthy control participants on at least one neuropsychological measure of EF. Results of the meta-analysis demonstrate that MDD is reliably associated with impaired performance on neuropsychological measures of EF, with effect sizes ranging from d = 0.32–0.97. While patients with MDD also have slower processing speed, motor slowing alone cannot account for these results. In addition, some evidence suggests that deficits on neuropsychological measures of EF are greater in patients with more severe current depression symptoms, and those taking psychotropic medications, while evidence for effects of age was weaker. The results are consistent with the theory that MDD is associated with broad impairment in multiple aspects of EF. Implications for treatment of MDD and theories of EF are discussed. Future research is needed to establish the specificity and causal link between MDD and EF impairments.

Keywords: executive function, major depressive disorder, meta-analysis

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common mental illnesses (with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 16.6%), and is associated with significant impairments in social, occupational, and educational functioning (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005). Cognitive impairments are now widely acknowledged as an important aspect of MDD. Indeed, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-IV) criteria for MDD include “diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Like this criterion, many theories have posited non-specific impairments in cognitive function associated with MDD, for example low motivation leading to difficulty with effortful tasks (e.g., Weingartner, Cohen, Murphy, Martello, & Gerdt, 1981), depleted cognitive resources in general (e.g., Mathews & MacLeod, 1994), difficulty initiating efficient cognitive strategies (e.g., Hertel & Gerstle, 2003), or slowed processing speed (e.g., Den Hartog, Derix, van Bemmel, Kremer, & Jolles, 2003; Nebes et al., 2000).

More recently, it has been proposed that executive function (EF) may be particularly impaired in individuals with MDD, and that problems in other domains, such as memory, attention, and problem-solving, may arise because these abilities rely heavily on aspects of EF and prefrontal function (Levin, Heller, Mohanty, Herrington, & Miller, 2007; Nitschke, Heller, Imig, McDonald, & Miller, 2004). While EF has been defined in different ways, these definitions all share the idea that EFs are higher-level cognitive processes, which control and regulate lower-level processes (e.g., perception, motor responses) to effortfully guide behavior towards a goal, especially in non-routine situations (e.g., Alvarez & Emory, 2006; Banich, 2009). Thus, EFs are distinct from more automatic cognitive processes that have been over-learned by repetition (e.g., motor, reading, and language skills, semantic memory, object recognition; Shallice & Burgess, 1996). EFs allow us to respond flexibly to the environment: to break out of habits, make decisions and evaluate risks, plan for the future, prioritize and sequence actions, and cope with novel situations, among many other things. In other words, EFs are essential for successfully navigating nearly all of our daily activities. Impairments in EF thus have serious consequences, which may be as important to quality of life and functional outcomes as affective symptoms.

EF appears to be especially vulnerable to disruption, with evidence for EF impairments associated with disorders including schizophrenia (e.g., Fioravanti, Carlone, Vitale, Cinti, & Clare, 2005), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (e.g., Willcutt, Doyle, Nigg, Faraone, & Pennington, 2005), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (e.g., Olley, Malhi, & Sachdev, 2007), among others. Thus, it has been proposed that EF deficits may be transdiagnostic intermediate phenotypes or risk factors for emotional, behavioral, and psychotic disorders (Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011). However, the existence and nature of EF impairments associated with MDD remain strongly debated, with some arguing that patients with MDD have no appreciable impairments in cognition (e.g., Grant, Thase, & Sweeney, 2001) and others that they have pronounced neuropsychological impairments (e.g., Porter, Gallagher, Thompson, & Young, 2003). Addressing this debate will be critical not only for understanding cognitive symptoms associated with MDD, but also for clarifying the degree to which EF deficits span disorders.

Executive and Prefrontal Function

Many specific components of EF have been proposed as scientists build a broad concept of EF, including creating, maintaining, and switching between task goals; sequencing behavior; inhibiting habitual behaviors (prepotent responses) and distracting information; decision-making; and selecting among competing options, among many others (e.g., Aron, 2008; Badre & Wagner, 2007; Banich, 2009; Miyake, et al., 2000; Thompson-Schill, Bedny, & Goldberg, 2005). Across models of EF, it is nearly universally recognized that while there is a unitary aspect of EF, a number of these components are also behaviorally, genetically, and neurally dissociable (e.g., Baddeley, 1996; Collette et al., 2005, Friedman et al., 2008; Miyake et al., 2000).

One influential model of EF, the three-component model (Friedman, et al., 2008; Miyake, et al., 2000) describes three key aspects of EF: (1) updating (adding relevant and removing no longer relevant information from working memory), (2) shifting between tasks or mental sets, and (3) inhibiting prepotent responses, as well as a common EF component tapped by all EF tasks (and which may subsume inhibition, Friedman et al., 2008). Multiple studies have found that while aspects of EF are moderately correlated (i.e., share a common EF component), they are separable (i.e., have unique components; e.g., Fisk & Sharp, 2004; Friedman et al., 2006; Hedden & Yoon, 2006; Huizinga, Dolan, & van der Molen, 2006; Miyake et al., 2000; Willcutt et al., 2001). Importantly, EF components are also differentially associated with aspects of psychopathology and cognition. For example, poor common EF and inhibition predict attention, conduct, and substance use problems in adolescents (Friedman et al., 2007; Young et al., 2009), while only updating predicts IQ (Friedman et al., 2006). Given these dissociations, and the unique cognitive processes, genetic influences, and neural substrates supporting different aspects of EF, it is important to consider both specific EF domains and what is common across them.

Components of EF

While updating, shifting, and inhibition are important aspects of EF, this model in no way posits that these are the only components. Indeed, several other EF domains have been well defined in the literature, including verbal and visuospatial working memory, planning, and verbal fluency. In each domain, studies using latent variable and correlational approaches have provided support for the existence of correlated but separable EF components, and confirmed that tasks posited to tap each aspect of EF are related to one another (Table 1).

Table 1.

Commonly Used Neuropsychological Measures of Executive Function (EF) and their Construct Validity

| EF Component | Task | Description | Construct Validitya | Prefrontal Involvement | Other Cognitive Demandsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shifting | Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) | Learn from feedback to sort cards by one dimension (e.g., color), and then switch to a different dimension (e.g., shape) when given negative feedback on the first dimension (repeats with multiple sorting rules). | Loads on a shifting latent variable (Miyake et al., 2000) | VLPFC, medial PFC, ACC (meta-analysis, Buchsbaum, Greer, Chang, & Berman, 2005) | Learning from feedback, visual processing, numerical processing, categorization, rule induction, working memory for current rule. |

| Trail Making Test Part B | Alternately connect letters and numbers in sequence (A-1-B-2 etc.) Often compared to Trail Making A (connect letters or numbers only, does not require shifting). |

Correlates with switch-cost on task shifting tasks Arbuthnott & Frank, 2000), and WCST (Sanchez-Cubillo et al., 2009) | VLPFC, DLPFC, medial PFC, ACC (TMT-B > TMT-A; e.g., Jacobson, Blanchard, Connolly, Cannon, & Garavan, 2011; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Moll, Bramati, & Andreiuolo, 2002; Zakzanis, Mraz, & Graham, 2005). | Visual search, motor speed, sequencing, working memory for task rule. | |

| Intradimensional/Extradimensional Shift | Learn from feedback to select a stimulus based on one dimension, switch to the previously non-rewarded stimulus (intradimensional shift), then to a different stimulus dimension (extradimensional shift). | Designed as analog to WCST, correlates with WCST (Jazbec et al., 2007). | VLPFC, DLPFC (e.g., Hampshire & Owen, 2005). | Reversal learning, feedback learning, visual processing, categorization, rule induction, working memory for current rule. | |

| Inhibition | Color-Word Stroop | Identify the color ink a color word is printed in. Trials are incongruent (e.g., “red” written in blue ink) and congruent (e.g., “red” written in red ink) or neutral (non-color word). | Loads on inhibition latent variables (e.g., Friedman et al., 2008; Miyake et al., 2000) | VLPFC, DLPFC, medial PFC, ACC (meta-analysis; Nee at al., 2007). | Visual processing, language production, working memory for task rule. |

| Hayling | Read sentences where the final word is omitted but highly predictable. First complete sentences correctly (Part A), then with an unrelated word (part B). | Loads on an inhibition latent variable with the Stroop task (de Fries, Dixon, & Strauss, 2009) | VLPFC, DLPFC (e.g., Allen et al., 2008; Collette et al., 2001, Nathaniel-James & Frith, 2002). | Reading, language production, working memory for task rules, selection among options. | |

| Updating | n-Back | Indicate if the stimulus (usually letter) matches the stimulus n (e.g., 3) items back. | Loads on updating latent variable (Friedman et al., 2008) | VLPFC, DLPFC, anterior PFC, ACC (meta-analyses; McMillan, Laird, Witt & Meyerand, 2007; Owen, McMillan, Laird, & Bullmore, 2005). | Visual processing, sequencing |

| Visuospatial Working Memory | Corsi Block Tapping/Spatial Span | Tap irregularly arranged blocks/squares in the same order as experimenter (Corsi blocks) or computer (Spatial Span). | Loads on visuospatial working memory latent variable (e.g., Fournier-Vicente et al., 2008; Miyake, Friedman, Rettinger, Shah, & Hegarty, 2001) | VLPFC, DLPFC (e.g., Owen, Evans, & Petrides, 1996; Toepper et al., 2010). | Visual and motor processing, sequencing. |

| Delayed-Match-to-Sample | View a complex shape (the sample), then indicate after a delay if a probe matches the sample. | Loads on latent variable with other visual memory tasks (Robbins et al., 1994). | VLPFC, DLPFC, ACC (e.g., Kaiser et al., 2010; Schon, Quiroz, Hasselmo, & Stern, 2009). | Visual processing. | |

| Self-Ordered Pointing | Search an array of boxes for hidden tokens. Token is only in each location once. | Loads on latent variable with spatial span (Robbins et al., 1998), correlates with spatial span (Ross, Hanouskova, Giarla, Calhoun, & Tucker, 2007). | VLPFC, DLPFC, medial PFC, ACC (e.g., Owen, et al., 1996; Provost, Petrides, & Monchi, 2010 | Visual search, strategy formation, reversal learning. | |

| Verbal Working Memory | Forward Digit Span | Repeat sequence of numbers in the same order presented. | Loads on latent variables with other verbal working memory tasks (e.g., Kane et al., 2004; Mertens, Gagnon, Coulombe, & Messier, 2006; Roberts, Stankov, Pallier, & Dolph, 1997). | VLPFC, DLPFC, medial PFC/ACC (e.g., Gerton et al., 2004; Owen, Lee, & Williams, 2000) | Auditory or visual processing, language production, sequencing. |

| Backward Digit Span | Repeat sequence of numbers in the reverse order presented. | Loads on latent variables with other verbal working memory tasks (e.g., Fournier-Vicente et al., 2008; Mertens et al., 2006; Waters & Caplan, 2003) | VLPFC, DLPFC, medial PFC, ACC (e.g., Gerton et al., 2004; Owen et al., 2000) | Auditory or visual processing, language production, sequencing. | |

| Planning | Tower of London/Stockings of Cambridge | Move rings on pegs from a starting position to a target position in as few moves as possible, following a set of rules. | Correlates with Tower of Hanoi planning task (Welsh & Huizinga, 2001; Welsh, Satterlee-Cartmell, & Stine, 1999) | VLPFC, DLPFC, anterior PFC (e.g., Kaller, Rahm, Spreer, Weiller, & Unterrainer, 2011; Wagner, Koch, Reichenbach, Sauer, & Schlösser, 2006) | Visual processing, sequencing, working memory for task rules. |

| Verbal Fluency | Phonemic Verbal Fluency | Say as many items starting with a certain letter (usually F, A, S) as possible in 1 (or 3) min. | Loads on verbal fluency latent variable (Unsworth, Spillers, & Brewer, 2011) | VLPFC, DLPFC, ACC (meta-analysis; Costafreda et al., 2009). | Vocabulary, language production, memory retrieval, strategy formation |

| Semantic Verbal Fluency | Say as many words from a semantic category (e.g., animals) as possible in 1 (or 3) min. | Loads on verbal fluency latent variable (Unsworth et al., 2011) | VLPFC, DLPFC, ACC (e.g., Hirshorn & Thompson-Schill, 2006; Whitney et al., 2009 | Semantic knowledge, semantic memory retrieval, language production, strategy formation |

Note. PFC = prefrontal cortex; VLPFC = ventrolateral prefrontal cortex; DLPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; ACC = anterior cingulate cortex.

Examples of evidence that each task is related to other tasks within the relevant EF component.

Examples of some other cognitive demands imposed by each task (there may be other demands not listed).

Updating is defined as monitoring and coding incoming information for task-relevance, and replacing no longer relevant information with newer, more relevant information (Miyake et al., 2000). The most common updating task in the MDD literature is the n-back task, in which participants indicate if the stimulus (usually a letter or number) matches the stimulus n (e.g., 3) items back. The dependent measures are reaction time and accuracy.

Shifting is defined as switching between task sets or response rules (Miyake et al., 2000). The most common shifting tasks in the MDD literature are the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, the Trail Making Test part B, and the Intradimensional/Extradimensional Shift task. In the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (Berg, 1948; Strauss, Sherman, & Spreen, 2006), participants sort cards by one dimension (e.g., color), and then switch to a different dimension (e.g., shape) when given negative feedback. This process repeats with multiple sorting rules. The measures of shifting are perseverative errors (sorting by the old rule) and category sets achieved (number of successful switches). The Trail Making Test part B (Partington & Leiter, 1949; Strauss et al., 2006) requires alternately connecting letters and numbers (A-1-B-2 etc.). It is often compared to the Trail Making Test part A, which does not require switching (connecting letters or numbers only). In the standard version of the task, the tester points out errors immediately, and the participant must correct them before going on. Thus, the dependent measure, total time, reflects a combination of slow and error-prone performance. The Intradimensional/Extradimensional Shift task (Robbins et al., 1998) requires learning from feedback to select a stimulus based on one dimension, switching to the previously non-rewarded stimulus (intradimensional shift), and then switching to a different stimulus dimension (extradimensional shift). Dependent variables include the number of trials needed to switch and number of switches achieved.

Inhibition is defined as suppressing or avoiding a prepotent (automatic) response in order to make a less automatic but task-relevant response (Miyake et al., 2000). The most common inhibition task in the MDD literature is the color-word Stroop task (Strauss et al., 2006; Stroop, 1935), in which participants name the color of the ink that color words are printed in (e.g., the word blue printed in red ink), overriding the automatic response of reading the word. This incongruent condition is compared to a neutral condition in which participants name ink colors in the absence of conflicting color word information. Dependent measures include time to complete the incongruent condition, the difference in the time required to complete the incongruent and neutral condition (interference), and accuracy on the incongruent condition.

Working memory is defined as actively maintaining (i.e., ‘holding on line’) or manipulating information across a short delay, and can be divided into verbal (e.g., words, letters, and numbers) and visuospatial (e.g., shapes, patterns, and spatial locations) components (e.g., Baddeley, 1992, 1996; Repovs & Baddeley, 2006). The most common verbal working memory tasks in the MDD literature are forward and backward digit span, in which participants hear a sequence of numbers and repeat it in forward or reverse order. The dependent measure is the participant's span, which is the longest sequence successfully repeated. The most common visuospatial tasks are spatial span, delayed-match-to-sample, and self-ordered pointing. In the spatial span task (also known as the Corsi block tapping or block span task; e.g., Strauss, et al., 2006) participants watch a pattern of taps on irregularly arranged blocks/squares and repeat it in the same order (forward span) or reverse order (backward span). The dependent measure is the participant's span (longest correct sequence). In the delayed-match-to-sample task participants maintain a complex shape in working memory across a delay (4-12 seconds) and then indicate if a probe stimulus matches it. Dependent measures are reaction time and accuracy. In the self-ordered pointing task (Owen, Downes, Sahakian, Polkey, & Robbins, 1990; also known as the spatial working memory task in the CANTAB; Robbins et al., 1998), participants search an array of boxes/images for hidden tokens. The primary dependent measure is between-search errors, when the participant returns to a previously searched location.

Planning is defined as identifying and organizing a sequence of steps to achieve a goal (e.g., Lezak, Howieson, & Loring, 2004). Planning tasks involve multiple cognitive demands (e.g., Goel & Grafman, 1995) and so may not represent a single EF ability. However, they are frequently used in clinical studies, perhaps because this complexity may be seen as a benefit for relating laboratory task performance to complex real-world tasks. The most common planning task in the MDD literature is the Tower of London, in which participants move beads across pegs from a starting position to target position in as few moves as possible (Shallice, 1982). Dependent measures include the number of moves needed to reach the target position and the number of problems solved in the minimum number of moves.

Verbal fluency is defined as the ability to generate words in a limited period of time, from semantic categories (semantic verbal fluency; e.g., animals) or starting with certain letters (phonemic verbal fluency; e.g., Troyer, Moscovitch, & Winocur, 1997). The dependent measure reported is the number of words generated. Like planning, verbal fluency tasks likely tap multiple cognitive processes (e.g., Rende, Ramsberger, & Miyake, 2002). However, they form a distinct component separable from other EF components (Fisk & Sharp, 2004), depend on prefrontal function (e.g., Alvarez & Emory, 2006), and are widely used in the clinical literature.

What is common across EF measures?

Both theoretical perspectives and empirical evidence suggest that along with these specific components of EF, there is also a common mechanism across EFs (e.g., Duncan & Owen, 2000; Engle, Tuholski, Laughlin, & Conway, 1999; Friedman et al., 2008; Miyake et al., 2000), which is separable from perceptual speed and fluid intelligence (Friedman et al., 2008). This common mechanism is hypothesized to be the ability to maintain goal and context information in working memory (Miyake et al., 2000). This view is compatible with accounts of EF that view the central role of the frontal lobes to be active maintenance of goals, plans, and other task-relevant information in working memory (e.g., Engle et al., 1999; Hazy, Frank, & O'Reilly, 2007). Thus, the ability to keep task-relevant information active in working memory may be essential for all aspects of EF (Miyake et al., 2000).

Prefrontal cortex and EF

‘Frontal lobe tasks’ and EF are often used synonymously in the literature, and indeed EF relies heavily on prefrontal cortex (PFC), although EF tasks also recruit broader neural networks, including posterior cortical and subcortical areas, and connectivity between these regions. Neuroimaging research in healthy individuals demonstrates that all of the neuropsychological measures of EF included in the current meta-analysis activate PFC (Table 1). Neuroimaging methods (fMRI and PET) provide powerful, non-invasive measures of brain function during EF tasks, by measuring hemodynamic correlates of neural activity. These methods can provide important insight into the mechanisms underlying EF deficits in MDD, by making contact with the wider cognitive neuroscience literature.

Multiple theories have been proposed for the organization of PFC and the role of different PFC regions in EF (e.g., Badre, 2008; Banich, 2009; Christoff & Gabrieli, 2000; Duncan & Owen, 2000; Petrides, 2005; Stuss & Alexander, 2007). A full discussion of these theories is beyond the scope of the current paper, but the PFC neuroanatomy relevant to understanding neuroimaging findings in patients with MDD is briefly described here. Although many neural areas have been implicated in EF, across multiple theories and empirical studies, three main subdivisions of PFC emerge as key for EF: dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC), ventrolateral PFC (VLPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). For many different EF tasks, there is joint recruitment of these regions (e.g., Duncan & Owen, 2000). Meta-analyses of neuroimaging studies have found reliable activation of DLPFC, VLPFC, and dorsal ACC for inhibition (Nee, Wager, & Jonides, 2007), shifting (Wager, Jonides, & Reading, 2004), working memory (Wager & Smith, 2003), and verbal fluency (Costafreda, David & Brammer, 2009), while a qualitative review concluded that these regions were also active for planning (Collette et al., 2006).

However, different EF components have also been found to recruit some unique neural substrates (e.g., Collette et al., 2005; Sylvester et al., 2003), with updating and inhibition associated with more anterior prefrontal areas than shifting. Within the domain of working memory, meta-analytic evidence suggests that verbal working memory more consistently activates left PFC, while visuospatial working memory more consistently activates right PFC (Wager & Smith, 2003). Additionally, manipulating items held in working memory is associated with VLPFC activation, while updating the contents of working memory is associated with DLPFC activation (Wager & Smith, 2003). Thus, as for behavioral performance, there are both shared and unique neural substrates for different components of EF.

Is EF Impaired in Patients with MDD?

MDD is associated with structural and functional abnormalities in PFC, including DLPFC, VLPFC and ACC (for reviews see Levin et al., 2007; Rogers et al., 2004), and a meta-analysis found that patients with depressive disorders had decreased DLPFC and ACC activation during a resting state (Fitzgerald, Laird, Maller, & Daskalakis, 2008). This prefrontal hypoactivity may be related to reduced levels of the main excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate, associated with MDD (for a review, see Yüksel & Ongur, 2010). As discussed in the previous section, the PFC regions that are hypoactive in MDD are implicated in multiple aspects of EF. Thus, it has been posited that impaired PFC function in MDD may lead to broad impairment in EF (e.g., Davidson, Pizzagalli, Nitschke, & Putnam, 2002). Specifically, decreased PFC function may lead to decreased goal setting and ability to override established behaviors, and subsequent decreases in the formation of organizational strategies for action in patients with MDD (avolition; Nitschke & Mackiewicz, 2005). This theory is compatible with the view that common EF, conceptualized as maintaining task-relevant information in working memory, may be impaired in patients with MDD, leading to deficits across all aspects of EF.

However, evidence for EF impairments associated with MDD is mixed. While many studies have reported significant deficits on many neuropsychological measures of EF, others have reported no significant differences between patients with MDD and healthy control participants. Authors have consequently reached a wide range of conclusions about the association between MDD and EF, from no appreciable impairments in cognitive functioning (e.g., Grant et al. , 2001) to pronounced neuropsychological impairment (e.g., Porter et al., 2003). Several recent reviews have reported partial support for impairments across multiple aspects of EF, including shifting, inhibition, working memory, planning, and verbal fluency (DeBattista, 2005; Hammar & Ardal, 2009; Ottowitz, Dougherty, & Savage, 2002; Rogers et al., 2004).

Previous meta-analyses also present mixed conclusions. While there have been no recent, comprehensive meta-analyses investigating neuropsychological measures of EF in MDD, previous meta-analyses found mixed results, based on a small number of studies. One reported significant impairments for patients with MDD on verbal fluency (semantic verbal fluency, d = 0.97, k = 2; phonemic verbal fluency, d = 0.61, k = 7), and inhibition (Stroop, d = 0.69, k = 2), but not shifting (Trail Making Test part B, d = 0.77, k = 5; Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, d = 0.32, k = 3), or verbal working memory (backward digit span, d = 0.32, k = 10; Zakzanis, Leach, & Kaplan, 1998). Another found reliable deficits on verbal fluency (phonemic verbal fluency, d = 0.55, k = 3) and ‘mental flexibility and control’ (Trail Making Test part B and Stroop, d = 1.31, k = 3), but not working memory (digit span and spatial span, d = 0.18, k = 3; Veiel, 1997). Two additional meta-analyses examined EF in mood disorders more broadly, but did not provide separate analyses for patients with MDD. One found broad impairments in verbal working memory (forward digit span, d = 0.37, k = 9; backward digit span, d = 0.39, k = 8), verbal fluency (phonemic verbal fluency, d = 0.64, k = 14; semantic verbal fluency, d = 1.07, k = 4), shifting (Trailing Making Test part B, d = 0.66, k = 5), and inhibition (Stroop, d = 1.00, k = 5; Christensen, Griffiths, Mackinnon, & Jacomb, 1997). A second meta-analysis primarily investigated verbal fluency and found significant effects for both phonemic (d = 0.30, k = 53) and semantic (d = 0.44, k = 15) fluency, with a larger effect for semantic fluency (Henry & Crawford, 2005). Within studies reporting verbal fluency, other tasks were also analyzed, with small but significant effects for shifting (Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, d = 0.27, k = 14) and inhibition (Stroop, d = 0.17, k = 11). Thus, while there has been extensive investigation of EF in patients with MDD, divergent results and a lack of recent, comprehensive meta-analyses limit the conclusions that can be drawn.

One source of mixed findings in the literature may be methodological factors, including low statistical power, the use of only one or a few neuropsychological tasks to assess EF, and failure to control for non-EF impairments. First, many studies have fewer than 30 MDD participants, which provides adequate power for detecting only large effect sizes, not more realistically moderate effects (e.g., Cohen, 1992). Most of these studies report at least one null result, which is often interpreted as showing a lack of impairment, when lack of power is a viable alternative explanation. Meta-analysis is well suited to address low power, because even results that were non-significant in the original study can contribute to a significant effect across studies.

Second, many studies use only a small number of neuropsychological measures of EF. This approach is problematic because using single tasks creates a task impurity problem, which is particularly pervasive in studies of EF (Burgess, 1997; Phillips, 1997). This is because EFs necessarily operate on other cognitive processes (e.g., shifting occurs between tasks such as identifying colors and shapes, which require non-EF abilities like visual processing; Miyake et al., 2000). Thus, a low score on a single EF task does not necessarily mean impaired EF– it could instead be due to impairment on other aspects of the task. This problem can be addressed by investigating performance on tasks that have the target component (e.g., updating) in common, but have very different non-EF aspects (e.g., the nature of the information to be updated); thus, while each task suffers from the task impurity problem, what they have in common is only the EF component of interest (Miyake et al., 2000). Ideally, more latent variable studies are needed which extract only the variance shared across multiple measures of each EF component. However, in practice such studies may be difficult to conduct with clinical populations, as it may be unfeasible to recruit a sufficiently large sample for latent-variable analysis, and patients may be unwilling or unable to complete long testing sessions. Meta-analysis provides an alternative, if imperfect, solution. Although multiple tasks may not be used by each study, multiple tasks are used across studies. Thus, effect sizes can be compared across tasks that share a target EF component but differ in other task demands.

Finally, many studies fail to control for non-EF aspects of cognition. Using multiple measures designed to tap specific aspects of EF is a critical step in establishing the specificity of EF impairments in MDD. However, it may not fully accomplish this, since some non-EF abilities, such as processing speed, may be shared across EF measures. Thus, this problem must be addressed by including additional control conditions within EF tasks and/or separate control tasks. Control conditions within tasks share the non-EF demands of the task, differing only in the key EF demand. Since it is difficult to include control conditions for tasks tapping certain EF components, it may be necessary to include separate control tasks as well. For example, psychomotor speed tasks, which are thought not to rely on EF, may be appropriate control tasks.

Are EF Deficits Moderated by Clinical and Demographic Factors?

An additional source of variance leading to mixed results across studies may be the diversity of MDD patient samples, including variability in current depression symptom severity, psychotropic medication use, age, and comorbidity.

Depression symptom severity

There is some evidence that EF impairment is greater in patients with more severe depressive symptoms (McClintock, Husain, Greer, & Cullum, 2010; McDermott & Ebmeier, 2009). A recent meta-analysis found a significant correlation between depression severity and performance on neuropsychological measures of EF (McDermott & Ebmeier, 2009). However, this meta-analysis only included the small number of studies (k = 10) that conducted correlation analyses between depression severity and task performance, rather than investigating associations with depression severity across studies. In addition, it did not examine specific aspects of EF separately, and included studies of patients with minor depression. Thus, it is uncertain whether these findings apply to MDD specifically, and whether depression symptom severity predicts performance on all aspects of EF equally. Moreover, some studies have failed to find a relationship between depression symptom severity and EF impairments (e.g., Harvey et al., 2004; Porter et al., 2007). Likewise, while some studies have found improvements in one aspect of EF, verbal fluency, as depression symptoms improved (Beblo, Baumann, Bogerts, Wallesch, & Herman, 1999; Reppermund, Ising, Lucae, & Zihl, 2009; Trichard et al., 1995), studies of other aspects of EF have found relatively stable impairments (Biringer et al., 2005; Trichard et al., 1995). Thus, it remains unclear whether impairments in some or all aspects of EF are sensitive to the current level of depression symptomatology or represent stable traits independent of current depression severity.

Medication

Cognitive deficits in depression are not merely an artifact of drug side effects, as a number of studies have found significant EF impairment in medication-free participants (Hinkelmann et al., 2009; Merriam, Thase, Haas, Keshavan, & Sweeney, 1999; Porter, Gallagher, Thompson, & Young, 2003; Tavares et al., 2007) and medication-naïve adolescents (Cataldo, Nobile, Lorusso, Battaglia, & Molteni, 2005; Matthews, Coghill, & Rhodes, 2008). However, some evidence suggests that long-term or repeated use of some antidepressant medications may impair cognitive function (McClintock et al., 2010). Tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants may produce larger impairments than selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (Porter et al., 2007), although there is some evidence for negative cognitive effects of SSRIs with anticholinergic or antihistamine actions (Lane & O'Hanlon, 1999).

Age

Age-related declines in brain function are most pronounced for PFC (e.g., Fuster, 1989; Woodruff-Pak, 1997), and performance on neuropsychological measures of EF declines with age (e.g., Bryan & Luszcz, 2000; Cepeda, Kramer, & de Sather, 2001; Salthouse, Atkinson, & Berish, 2003; Troyer et al., 1997). Thus, it seems possible that depression and age may have superadditive effects on EF, leading to more pronounced EF deficits in depressed older adults. Indeed, some researchers have argued, based on reviews of the literature, that MDD is more reliably related to cognitive deficits in elderly patients than in young adults (Elliott, 1998; Porter et al., 2007). However, this possibility has not been systematically tested, with few studies directly comparing age groups. Two studies that did compare younger and older adults with MDD found greater impairment in older MDD patients on some neuropsychological measures of EF but not others (Lockwood, Alexopoulos, & van Gorp, 2002; Nakano et al., 2008). Thus, it remains unclear whether age and depression are merely independently associated with poor EF, or whether they interact to produce larger EF deficits in depressed older adults.

Comorbidity

Nearly 60% of patients with MDD also meet criteria for at least one anxiety disorder (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005). These high rates of comorbidity pose special problems for research (and research reviews). Although findings are mixed, evidence suggests that trait anxiety and anxiety disorders are associated with impairments on neuropsychological measures of EF (e.g., Castaneda, Tuulio-Henriksson, & Marttunen, 2008; Eysenck & Derakshan, 2011; Olley et al., 2007; Snyder et al., 2010). Thus, it is possible that some deficits attributed to MDD could actually be due to a comorbid disorder (e.g., an anxiety disorder), or co-occurring disorders may contribute additively or interactively to EF impairments. For example, some studies found that only depressed patients with comorbid anxiety had impaired EF (Basso, et al., 2007; Lyche, Jonassen, Stiles, Ulleberg, & Landrø, 2011). In other cases, comorbid anxiety may mask the effect of depression (e.g., Engels, et al., 2010; Keller, et al., 2000). Many studies fail to assess or control for comorbidity, and few studies have directly investigated the effects of comorbid anxiety and depression. However, some studies have excluded participants with comorbid Axis I disorders (including anxiety disorders), while others have not. Thus, while it is not possible to fully address the issue of comorbidity given the current literature, a meta-analytic approach may provide some insight. For example, if only studies that include participants with comorbid Axis I disorders show deficits on neuropsychological measures of EF, it would suggest that comorbid disorders, rather than depression per se, are associated with EF deficits in patients with MDD.

Can EF Impairments be Explained by Deficits in Psychomotor Speed?

Psychomotor retardation, which is related to the cognitive concept of processing speed, is an important symptom of MDD (although it is not required for a diagnosis of MDD, and psychomotor agitation may also occur). Manifestations of psychomotor retardation may include slowed movements, reduced speaking rate, and delayed motor initiation (Caligiuri & Ellwanger, 2000). Some have therefore proposed that impairments on neuropsychological measures of EF associated with MDD might actually be due to slowed processing speed.

The motor slowing hypothesis posits that depression causes motor slowing, independent of higher cognitive processes (which may also be impaired; e.g., Sabbe, Hulstijn, van Hoof, Tuynman-Qua, & Zitman, 1999; van Hoof, Jogems-Kosterman, Sabbe, Zitman, & Hulstijn, 1998). Supporting this theory, studies have found significant motor slowing for MDD patients (who were not pre-selected on the basis of psychomotor retardation) on tasks with minimal higher-level cognitive demands, such as pointing at a target (Caligiuri & Ellwanger, 2000) and drawing simple lines (Pier, Hulstijn, & Sabbe, 2004; Sabbe et al., 1999). This hypothesis implies that motor slowing in MDD may account for deficits on speeded tasks or reaction time measures, while impairment of higher-level cognitive processes might affect both timed and untimed tasks.

A broader theory, the cognitive speed hypothesis, has also been proposed. However, in its current form it is not empirically falsifiable, and thus is only briefly discussed here. The cognitive speed hypothesis posits that the rate of processing limits performance on higher-level operations because if processing steps are carried out too slowly the products of earlier operations may be lost or no longer relevant by the time later operations occur (Nebes et al., 2000). This theory therefore posits that the effect of processing speed is not restricted to timed or speeded tasks, and could result in overall decrements in task performance. Thus, it is not clear what would constitute definitive evidence against the cognitive speed hypothesis. Since cognitive slowing is posited to affect even untimed and unspeeded tasks, impairments on self-paced accuracy measures of EF would not be considered evidence against this hypothesis. Nor would greater impairment on EF tasks than processing speed tasks, since it is always possible to argue that more complex tasks may require more processing steps, and are thus more affected by cognitive slowing. Thus, while the motor speed hypothesis can be empirically evaluated (including by meta-analyses), evaluation of the cognitive speed hypothesis must await more complete specification of the theory in a way that makes it empirically falsifiable.

Objectives of the Current Meta-Analysis

The current meta-analysis synthesizes research findings to addresses three central questions: (1) whether neuropsychological measures of EF are reliably impaired in patients with MDD compared to healthy control participants, (2) whether apparent EF impairments can be explained by deficits in psychomotor speed, and (3) whether deficits on neuropsychological measures of EF associated with MDD are modulated by clinical and demographic factors. To address the first question, the meta-analysis tests whether there is reliable cumulative evidence across studies for impairments on neuropsychological measures of EF in patients with MDD compared to healthy control participants, despite mixed results from individual studies. Furthermore, the current meta-analysis evaluates whether deficits on measures designed to tap particular aspects of EF are consistent across tasks, providing evidence that impairments are not task-specific. To address the second question, the meta-analysis compares effect sizes for psychomotor speed tasks with those for neuropsychological measures of EF, and evaluates impairment on self-paced, accuracy measures of EF, which provide evidence of higher-level deficits not caused by motor slowing. To address the third question, the meta-analysis includes the following moderator variables: current depression symptom severity and remission status, medication (percentage of patients receiving psychotropic medications at the time of testing), patient age, and whether patients with comorbid Axis I disorders were excluded from the study.

The current meta-analysis is limited to patients with MDD in order to reduce heterogeneity across patient samples. In comparing patients with MDD to healthy control participants, the objective is not to identify deficits specific to MDD, but rather to clarify the pattern of impairments on neuropsychological measures of EF associated with MDD. This is the first step towards understanding a clinically significant problem and provides a foundation for future work to identify which aspects of EF impairment may be specifically associated with MDD and which may represent transdiagnostic features of psychopathology.

Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were required to include a patient group with a diagnosis of MDD or major depressive episode, and a healthy control group with no diagnosed psychopathology. Patients could be currently experiencing an episode of depression or in remission at the time of testing. Studies were excluded if they reported only mixed diagnostic groups (e.g., all mood disorders), or if depression was secondary to organic brain damage (e.g., traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer's disease) or a medical condition (e.g., heart failure). Studies were included if they tested MDD and control groups on at least one neuropsychological measure of EF and reported sufficient information to calculate effect sizes. Only tasks with emotionally neutral materials were included in the meta-analysis. This was done, first, to avoid confounding altered emotional processing with EF impairments, and second, because a recent meta-analysis examined the relation between depression and cognitive control over emotional materials (Peckham, McHugh, & Otto, 2010), and thus the current meta-analysis does not duplicate this effort.

Search Strategies

The author, who has a background in EF research, conducted the search and screening process. Searches were conducted in PubMed and ISI Web of Science through July 2011 using the keywords depression or depressive paired with executive function, working memory, inhibition, shifting, switching, planning, verbal fluency, cognitive, or neuropsychological for studies published in English at any time prior to the search date. An initial screen was conducted by examining titles to eliminate studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. Next, the abstracts of all remaining articles were examined, and if an article appeared likely to meet the inclusion criteria the full text was obtained. In addition, the reference lists of included articles, and articles citing included articles, were screened for any studies missed in the database search process. This process initially identified 145 studies for inclusion. Of these, 32 were excluded because they did not report sufficient information to calculate effect sizes (k = 17), did not include a healthy control group (k = 5), reported only mixed diagnostic groups (k = 7), or reported the same data as another study included in the meta-analysis (e.g., re-analyses; k = 8). Thus, a total of 113 studies were included in the meta-analysis (see Appendix A). Only peer-reviewed, published studies were included, as they are likely to be of higher quality. Trim and fill analyses (Duval & Tweedie, 2000; implemented in the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software package) and funnel plots were examined for evidence of publication bias (Appendix B, Figures S1-S8 and Table S1).

Coding Procedures

The tasks in the included studies determined the aspects of EF covered in the meta-analysis. Neuropsychological measures of EF were coded as tapping one of the following EF components, as detailed below: inhibition, shifting, updating, verbal and visuospatial working memory, planning, and verbal fluency. This list is not meant to be exhaustive of all EF abilities, but rather of the range of neuropsychological measures of EF included in the MDD literature. The author coded all studies. In addition, for 25% of studies, a second coder with a background in cognitive psychology coded the EF component tapped by each EF task. Intercoder agreement was high (96%)1; thus, the author's coding was used in all analyses. All other aspects of coding were objective, as they were supplied directly by the included manuscripts. For each EF component, all tasks tapping that component (listed below) were combined in composite score analyses. In addition, measures with five or more studies were also analyzed separately.

In addition, two types of non-EF comparison measures were also coded. First, two neuropsychological measures of EF reported by many studies, the Trail Making Test and the Stroop task, have baseline conditions that control for many non-EF aspects of the task (see Shifting and Inhibition sections). Second, some studies report measures of processing speed or vocabulary (see the Processing speed and vocabulary section).

Inhibition

The most reported inhibition task in the studies included in the meta-analysis is the color-word Stroop task (k = 40), with studies reporting one or more of the following dependent variables: time to complete the incongruent condition (k = 19), interference (k = 20), and accuracy (k = 10). Each of these measures was analyzed individually, and also included in a composite inhibition score averaging across all inhibition tasks in each sample. In addition, time to complete the neutral condition was included as a non-EF comparison measure (k = 14). The Hayling task (see Table 1 for description, k = 5) was analyzed individually and also included in the composite inhibition score. In addition, seven studies reported other inhibition tasks. The dependent measures are reaction time and errors. The go/no-go (k = 4) and stop-signal (k = 1) tasks both require making a response to some stimuli and withholding a response to others. The Simon task is a Stroop-like task where participants ignore the location of a stimulus (k = 1), while the flanker task requires ignoring incongruent surrounding stimuli to make a judgment about the central target (k = 1). These tasks were included in the composite inhibition score.

Shifting

The three most reported shifting tasks in studies in the meta-analysis were the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST, k = 25), the Trail Making Test part B (TMT-B, k = 35), and the Intradimensional/Extradimensional Shift task (ID/ED Shift, k = 15). In addition, the Trail Making Test part A (TMT-A) was included as a non-EF comparison measure (k = 32). These tasks were each analyzed individually and also included in a composite shifting score averaging across all shifting effect sizes for each study. For the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, the dependent measure was perseverative errors (when reported), or the number of stages achieved (when perseverative errors were not reported). The primary measure reported for both parts of the Trail Making Test is total time to complete the task; a few studies used a version without error correction and reported perseverative errors (e.g., A-B instead of A-1) or number correct. For the Intradimensional/Extradimensional Shift task, the dependent measures reported vary, and include intradimensional shift, extradimensional shift, and total errors; trials to criterion; and number of stages achieved. Since reporting across studies was not consistent enough to examine each measure independently, a composite score was calculated for each study.

In addition, five studies reported other shifting tasks: two variants on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (Cogtest Set Shifting, k = 1; BADS Rule Shift Cards, k = 1), a cued task-switching task (color-shape, k = 2), and a ‘rule-shift’ task in which participants switch which color stimuli receive a yes response (k = 1). These tasks were also included in the composite shifting score.

Updating

The n-back task was the most reported updating task (k = 7). It was analyzed individually, and also included in a composite updating score averaging across all updating tasks in each sample. In addition, three studies reported other updating tasks: the letter-memory task, in which participants continuously repeat the last four numbers in a sequence (k = 1); a task in which participants say the number n back on each trial (k = 1); and a recent-probes task in which participants update their representation of the stimuli on each trial to avoid false alarms to previously presented items (k = 1). These tasks were included in the composite updating score.

Verbal working memory

The most reported verbal working memory tasks were digit span forward (k = 27) and backward (k = 23), which were analyzed individually, and also included in a composite verbal WM score averaging across all verbal working memory measures reported for each sample. Forward digit span was also included in a verbal working memory maintenance composite score (tasks requiring maintenance of information in the order presented), and backward digit span was also included in a verbal working memory manipulation composite score (tasks requiring re-arrangement of information in working memory).

In addition, ten studies reported other verbal working memory tasks. The following tasks were included in the verbal working memory composite and the maintenance composite scores: California Verbal Learning Test trial one immediate recall (k = 2, repeat a list of words), Sternberg and letter maintenance tasks (k = 2, recall three numbers or letters after a delay), and reading span (k = 1, recall the last word of sentences in order). The following tasks were included in the verbal working memory composite and manipulation composite scores: digit or letter sequencing tasks (k = 2, repeat a list of numbers, reordering from lowest to highest, or letter, reordering in alphabetical order) and a letter-number sequencing task (k = 3, repeat a list of numbers and letters, reordering to say letters first, then numbers).

Visuospatial working memory

The most reported visuospatial working memory tasks were spatial span forward (k = 18) and backward (k = 9), delayed-match-to-sample (DMTS, k = 11), and self-ordered pointing (k = 12). These tasks were each analyzed individually and also included in a composite visuospatial working memory score averaging across all visuospatial working memory measures for each study. In addition, two studies reporting a delayed spatial match-to-sample task were included in the composite visuospatial working memory score.

Planning

The planning tasks reported by the studies included in the meta-analysis were the Tower of London (TOL) and closely related Stockings of Cambridge (SOC) task from the CANTAB (Robbins et al., 1998; k = 17). Dependent measures reported varied by study, and included number of moves to solve problems, number of moves in excess of the minimum number of moves required, and number of problems solved in the minimum number of moves (perfect solutions). These measures were included in a composite planning score.

Verbal fluency

Semantic (k = 24) and phonemic (k = 37) verbal fluency tasks were analyzed individually and also included in a composite verbal fluency score.

Processing speed and vocabulary

Processing speed and vocabulary measures were analyzed as non-EF comparison measures. The most reported processing speed task was the digit-symbol substitution task (k = 23). The dependent measure is the number of items correctly completed within the time limit. This task was analyzed individually, as it may impose some EF demands (see Discussion). In addition, 23 studies reported one or more psychomotor speed measure, including simple RT (k = 12), choice RT (k = 9), finger-tapping (tap fingers as quickly as possible, k = 5), and grooved pegboard (put pegs into holes in a board as quickly as possible, k = 1). These tasks were included in a psychomotor speed composite score.

The most reported vocabulary test was the National Adult Reading Test (k = 17, including versions in languages other than English), in which participants read a list of irregular words aloud (e.g., quadruped). The dependent measure is the number of pronunciation mistakes, which is converted to a verbal IQ estimate. Other measures included the WAIS-R vocabulary subtest (k = 9), Stanford-Binet vocabulary subtest (k = 1), Binois-Pichot vocabulary subtest (k = 2), Ammons Quick Test (k = 1), British picture vocabulary test (k = 1), Mill Hill vocabulary test (k = 1), and German vocabulary test (k = 1), which all yield standardized scores or verbal IQ estimates. These tests were included in a single vocabulary analysis.

Moderator Analyses

Information was coded on current depression symptom severity, age, psychotropic medication use, and comorbidity exclusions.2 When a moderator variable was not reported by a study, that study was not included in the applicable moderator analysis, but was included in all other analyses for which it reported data.

Current depression symptom severity

The mean score of the MDD group on at least one of the following standardized rating scales of depression severity was reported by 92% of studies. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D; Hamilton, 1960) is a clinician-administered scale based on 17 items (some versions include more items, but they are not included in the score). Reliability (internal, interrater, and retest) and validity (convergent, discriminant, and predictive) are generally good, although concerns have been raised about its congruence with the DSM-IV MDD criteria (Bagby, Ryder, Schuller, & Marshall, 2004). The Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) is also a clinician-administered scale, based on 10 items, with high interrater reliability and a significant correlation with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Montgomery & Asberg, 1979). The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961) and Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) are self-report scales based on 21 items. The BDI has been shown to have high internal validity and adequate retest reliability, as well as good convergent, discriminant and predictive validity (Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988). The BDI-II has similarly high internal reliability and good convergent validity (Beck Steer, Ball, & Ranieri, 1996; Osman et al., 1997). In addition, a few studies report the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS, 15 items, self-report; Brink et al., 1982), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale depression subscale (HADS, 7 items, self-report; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983), or Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10, 10 items, self-report; Kessler et al., 2002).

While they differ from each other in some ways, these rating scales have been shown to correlate highly with one another (e.g., Carmody et al., 2006; Uher et al., 2008). Thus, they were combined into a single severity moderator variable. Since the rating scales have different numbers of items and severity level categories, they were re-coded into a common metric to make moderator analysis possible (Table 2). The lowest severity level on each scale was coded as 0 (remission), and the following levels as 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), and 3 (severe/very severe). The HAM-D and MADRS use a fourth, very severe level not used by the other scales; thus, ratings of severe or very severe on these measures were both coded as 3. In rare cases where there was disagreement on severity level between measures reported for a sample (k = 3), the average of the rating was used (e.g., a sample rated severe on one questionnaire and moderate on another would be coded 2.5). To directly test whether neuropsychological measures of EF remain impaired in remission, dichotomous analyses comparing current depressive episode vs. remission were also conducted for those measures with at least five samples in remission.

Table 2.

Recoding of Measures of Current Depression Symptom Severity into a Common Metric

| Severity Measure | Cut-Point Source | Scoring | Recoding |

|---|---|---|---|

| HAM-D | Kearns et al., 1982 | 0-7= normal | 0 |

| 8-13 = mild | 1 | ||

| 14-18= moderate | 2 | ||

| 19-22= severe | 3 | ||

| ≥ 23= very severe | 3 | ||

| MADRS | Kearns et al., 1982 | 0-7 = recovered | 0 |

| 8-15= mild | 1 | ||

| 16-25= moderate | 2 | ||

| 26-30= severe | 3 | ||

| 31≥ = very severe | 3 | ||

| BDI | Beck, 1978 | 0-9= normal | 0 |

| 10-16= mild | 1 | ||

| 17-29= moderate | 2 | ||

| ≥ 30= severe | 3 | ||

| BDI-II | Beck et al., 1996 | 0-13 = minimal | 0 |

| 14-19= mild | 1 | ||

| 20-28= moderate | 2 | ||

| ≥ 29= severe | 3 | ||

| K10 | Andrews & Slade, 2001 | 10-19= well | 0 |

| 20-24= mild | 1 | ||

| 25-29= moderate | 2 | ||

| 30≥= severe | 3 | ||

| GDS | Yesavage et al., 1983 | 0-9= normal | 0 |

| 10-19= mild | 1 | ||

| ≥20 = severe | 3 | ||

| HADS | Zigmond & Snaith, 1983 | 0-7=normal | 0 |

| 8-10=mild | 1 | ||

| 11-14=moderate | 2 | ||

| 15-21=severe | 3 |

Note. The HAM-D and MADRS use a fourth, very severe level not used by the other scales; thus, ratings of severe or very severe on were both coded as 3. HAM-D = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MADRS = Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory II; K10 = Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Age

The mean age of the MDD group was included as a continuous variable in meta-regression analyses.3 Age was reported by all studies, and nearly all studies (92%) used age-matched MDD and control groups.

Medication

The percentage of the MDD group currently taking psychotropic medications was coded for each sample. Medication usage was reported by 88% of studies. Many studies only reported the total number of medicated patients; thus, a more detailed analysis of the types or duration of medication could not be conducted.

Comorbidity

The inclusion or exclusion of patients with comorbid DSM Axis I disorders was coded as a categorical variable. Studies that did not provide information about comorbidity were assumed to have not excluded such patients. Thus, all studies were coded as either excluding or not excluding patients with comorbid Axis I disorders. Few studies reported more detailed information on comorbidity, such as number and type of other disorders or measures of subclinical anxiety, so these factors could not be considered in the moderator analyses (in the studies which did list specific comorbid disorders, all were anxiety disorders).

Statistical Methods

For each study, effect sizes comparing the performance of MDD and control groups on each measure were calculated as Cohen's d (m1 - m2 / SDpooled, where m = group mean and SDpooled is the pooled standard deviation of the two groups). The number of studies for 22 of 30 measures was sufficient to achieve adequate power (> 80%) for detecting a small effect size (d = 0.3) even with large heterogeneity, with the remaining 8 analyses having power between 40–80% (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009). The sign of d was set such that a positive value always indicated poorer performance for the MDD group relative to the control group (e.g., lower accuracy, higher error rates, or longer RTs). Hedges’ small sample bias correction was applied to each effect size (dadj = d(1- (3/4N) - 9, where N = number of participants in the patient and control samples combined; Hedges, 1980). Effect sizes were weighted by sample size using inverse variance weights (w = (2(n1 + n2)n1n2) / (2(n1 + n2)2 + n1n2d2), where n1 and n2 are the number of participants in the patient and control groups respectively). Finally, outliers with effect sizes > d = 2.0, or +/- 3 SD from the mean effect size in each analysis, were excluded. Effect sizes were only excluded from the analysis in which they were statistical outliers.

Only one effect size from each MDD and control group comparison was included in each analysis to avoid statistical dependence. When five or more studies reported a measure, individual tasks and dependent measures were analyzed separately. In addition, all effect sizes were included in composite scores, which were calculated by averaging effect sizes within a construct (e.g., multiple inhibition measures; see Methods and Results). Nineteen studies reported two different MDD samples compared to the same control sample. In these cases, to avoid introducing statistical dependence, the MDD samples were first combined into a single sample using weighted means and standard deviations. (However, comparisons between the groups are reviewed in the Discussion section). Three studies reported both younger and older adult MDD samples, compared to their own age-matched control samples. In these cases, both sample comparisons were included since there is no statistical dependence. In addition, when patients were tested more than once (e.g., at different points in treatment), only the first test was analyzed, as practice effects may diminish the EF demands of tasks.

Random effects meta-analytic models were used for all analyses, as there are likely to be many sources of variability between study samples beyond sampling error, violating the assumptions of fixed-effects models (Raudenbush, 2009). Importantly, random effects models allow inferences to be drawn about the population as a whole, rather than only the samples tested. Mean effect size analyses were conducted using the SPSS meta-analysis macro developed by David B. Wilson (Wilson, 2006). For each analysis, weighted mean effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals were calculated. The null hypothesis that the mean effect size is zero was tested with the z statistic at the alpha=.05 significance level. The random effects variance component v represents the estimate of the amount of variance due to random effects. Heterogeneity in effect sizes was tested with the Qt statistic (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). Qt quantifies the degree to which the studies contributing to each weighted mean effect size can be considered homogeneous. If Qt is significant, it suggests that there are substantive differences between the studies in that analysis. In some cases, these differences may be partly accounted for by moderators, while in other cases they may result from other sources of variability between studies. The I2 statistic ((Q - (k - 1)) / Q) represents the percentage of total variability in the set of effect sizes due to true heterogeneity.

Moderator analyses were conducted using the SPSS meta-analysis macros developed by Wilhelm Hofmann (Hofmann, 2009), using mixed effects models with method of moments estimation. Current depression symptom severity (0 - 3), patient age, and medication status (% receiving psychotropic medications) were included as continuous variables in separate and combined meta-regression analyses. Comorbidity (patients with other Axis I disorders excluded or not), and remission status (in remission vs. current depressive episode) were included as categorical variables in meta-ANOVA analyses, whenever there were at least five studies in the smaller category. Moderator analyses were only conducted for measures with 20 or more effect sizes, as analyses with fewer studies have inadequate power and may produce unstable estimates (Marín-Martínez & Sánchez-Meca, 1998; Sánchez-Meca & Marín-Martínez, 1998).

Results

In total, the 113 studies in the meta-analysis included 7,707 participants: 3,936 patients and 3,771 healthy control participants. MDD and control groups were similar in age and gender composition. MDD groups included 2,404 females (61%), 1,395 males (35%) and 137 participants for whom gender was not reported (4%). Control groups included 2,246 females (60%), 1,428 males (38%) and 97 participants for whom gender was not reported (2%). The mean age of patients was 46 years, and of controls 45 years. In those samples reporting medication use, 41% of patients were taking psychotropic medications at the time of testing (medication information was not reported by 12% of studies). At the time of testing, depression symptom severity of the MDD group was severe in 52 studies, moderate in 25 studies, mild in 10 studies, and in remission in 19 studies (9 studies did not report symptom severity). Demographics for the subjects in each analysis are provided in Appendix B, Table S2. Age, medication use, and current depression symptom severity were not correlated with one another (ps > .10). Thirty-eight studies matched MDD and control participants on both IQ and education, and 23 studies excluded participants with comorbid Axis I disorders.

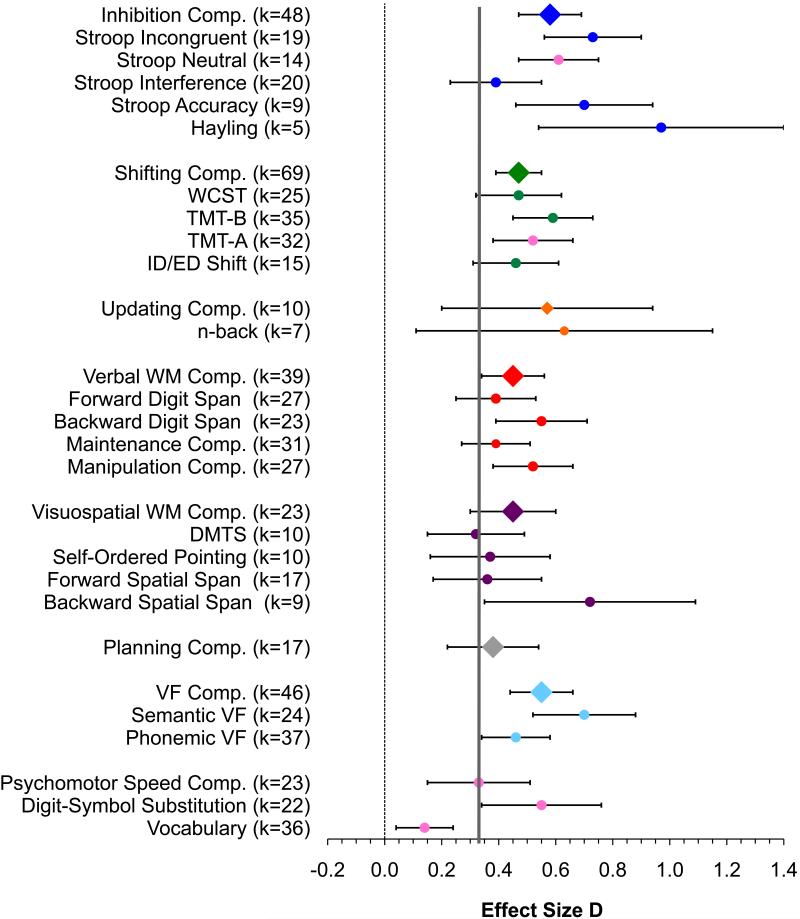

Outlier screening resulted in the exclusion of a total of 13 effect sizes, with one outlier each excluded in 10 analyses, and two outliers excluded in two analysis. Outlier effect sizes and mean effect sizes with outliers included are listed in Table 3 notes. Weighted mean effect sizes for all analyses comparing patients with MDD to healthy control participants are presented in Table 3 and plotted in Figure 1. Meta-multiple regression analyses for continuous moderators (current symptom severity, medication, and age) are presented in Table 4 (simple regression analyses are available in Appendix B, Table S3). Meta-ANOVA analyses of categorical moderators (remission status and comorbidity) are presented in Table 5 (categorical age analyses are available in Appendix B, Table S4). Analyses for IQ and education matched samples only (Table S5) and medication-free samples only (Table S6) are available in Appendix B, and complete data sets are available from the author upon request.

Table 3.

Weighted Mean Effect Size Analyses

| Measure | N | k | d | 95% Confidence Interval | SE | Z | p | Homogeneity Test | Sensitivity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | v | Q | df | p | I2 | Trim & Fill Adjusted d | IQ & Education Matched d | |||||||

| Inhibition: | |||||||||||||||

| Stroop Incongruenta | 1494 | 19 | 0.73 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.09 | 8.34 | <.001 | 0.08 | 42.76 | 18 | .001 | 58.87 | 0.58 | 0.88 |

| Stroop Neutral (comparison condition) | 1078 | 14 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.74 | 0.07 | 8.84 | <.001 | 0.01 | 14.54 | 13 | .3 | 17.47 | 0.49 | 0.68 |

| Stroop Interference | 1482 | 20 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 4.81 | <.001 | 0.06 | 39.22 | 19 | .004 | 51.56 | 0.30 | 0.47 |

| Stroop Accuracyb | 628 | 9 | 0.70 | 0.46 | 0.93 | 0.12 | 5.82 | <.001 | 0.06 | 14.60 | 8 | .067 | 45.21 | 0.50 | - |

| Hayling | 247 | 5 | 0.97 | 0.54 | 1.40 | 0.22 | 4.45 | <.001 | 0.13 | 9.23 | 4 | .056 | 56.66 | 0.97 | - |

| Inhibition Comp.c | 3274 | 48 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.69 | 0.06 | 9.95 | <.001 | 0.09 | 109.67 | 47 | <.001 | 57.14 | 0.42 | 0.62 |

| Shifting: | |||||||||||||||

| WCSTd | 1943 | 25 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.61 | 0.07 | 6.31 | <.001 | 0.07 | 52.66 | 24 | .001 | 54.42 | 0.35 | 0.43 |

| TMT-B | 2825 | 35 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.73 | 0.07 | 8.08 | <.001 | 0.12 | 101.66 | 34 | <.001 | 66.56 | 0.43 | 0.35 |

| TMT-A (comparison condition)e | 2794 | 32 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.66 | 0.07 | 7.42 | <.001 | 0.09 | 85.09 | 31 | <.001 | 63.57 | 0.35 | 0.37 |

| ID/ED Shiftf | 899 | 15 | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.61 | 0.18 | 5.88 | <.001 | 0.02 | 17.01 | 14 | .3 | 17.70 | 0.35 | 0.41 |

| Shifting Comp.g | 5154 | 69 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 10.93 | <.001 | 0.06 | 133.83 | 68 | <.001 | 49.19 | 0.36 | 0.40 |

| Updating: | |||||||||||||||

| n-Back | 324 | 7 | 0.63 | 0.11 | 1.15 | 0.26 | 2.37 | .018 | 0.38 | 27.02 | 6 | .001 | 77.79 | 0.63 | - |

| Updating Comp. | 528 | 10 | 0.57 | 0.20 | 0.94 | 0.19 | 3.00 | .003 | 0.26 | 35.22 | 9 | .001 | 74.45 | 0.57 | - |

| Verbal Working Memory: | |||||||||||||||

| Forward Digit Span | 1820 | 27 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.53 | 0.07 | 5.56 | <.001 | 0.06 | 47.55 | 26 | .006 | 45.32 | 0.39 | 0.42 |

| Backward Digit Span | 1700 | 23 | 0.55 | 0.39 | 0.71 | 0.08 | 6.86 | <.001 | 0.08 | 49.30 | 22 | .001 | 55.38 | 0.55 | 0.46 |

| Maintenance Comp. | 2093 | 31 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.51 | 0.06 | 6.32 | <.001 | 0.04 | 49.66 | 30 | .013 | 39.59 | 0.23 | 0.40 |

| Manipulation Comp. | 2051 | 27 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.66 | 0.07 | 7.42 | <.001 | 0.07 | 55.86 | 26 | .001 | 53.46 | 0.52 | 0.43 |

| Verbal WM Comp. | 2840 | 39 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 8.38 | <.001 | 0.04 | 65.59 | 38 | .004 | 42.06 | 0.45 | 0.40 |

| Visuospatial Working Memory: | |||||||||||||||

| DMTSh | 624 | 10 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.08 | 3.76 | <.001 | 0.00 | 9.18 | 9 | .4 | 1.96 | 0.23 | 0.40 |

| Self-Ordered Pointingi | 722 | 10 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.58 | 0.11 | 3.42 | .001 | 0.05 | 16.54 | 9 | .056 | 54.59 | 0.33 | 0.33^ |

| Forward Spatial Spanj | 1037 | 17 | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.55 | 0.10 | 3.70 | <.001 | 0.08 | 33.41 | 16 | .007 | 52.11 | 0.36 | 0.21^ |

| Backward Spatial | 598 | 9 | 0.72 | 0.35 | 1.09 | 0.19 | 3.85 | <.001 | 0.23 | 31.57 | 8 | <.001 | 74.66 | 0.63 | 0.75 |

| Span | |||||||||||||||

| Visuospatial WM | 1493 | 23 | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 6.07 | <.001 | 0.05 | 38.01 | 22 | .018 | 42.12 | 0.29 | 0.47 |

| Compk | |||||||||||||||

| Planning: | |||||||||||||||

| Planning Comp. | 1037 | 17 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.53 | 0.08 | 4.70 | <.001 | 0.03 | 23.40 | 16 | .1 | 31.62 | 0.26 | 0.29 |

| Verbal Fluency: | |||||||||||||||

| Semantic VF | 1642 | 24 | 0.70 | 0.52 | 0.88 | 0.09 | 7.56 | <.001 | 0.13 | 66.94 | 23 | <.001 | 65.64 | 0.53 | 0.75 |

| Phonemic VF | 2850 | 37 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 0.06 | 7.72 | <.001 | 0.06 | 73.12 | 36 | <.001 | 50.77 | 0.33 | 0.44 |

| VF Comp. | 3466 | 46 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.66 | 0.06 | 9.74 | <.001 | 0.07 | 100.43 | 45 | <.001 | 55.19 | 0.42 | 0.51 |

| Comparison Measures: | |||||||||||||||

| Psychomotor Speed | 1757 | 23 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.09 | 3.68 | <.001 | 0.11 | 63.24 | 22 | <.001 | 65.21 | 0.20 | 0.30^ |

| Comp. | |||||||||||||||

| Digit-Symbol | 1904 | 22 | 0.55 | 0.34 | 0.75 | 0.10 | 5.25 | <.001 | 0.17 | 88.76 | 21 | <.001 | 75.21 | 0.55 | 0.30 |

| Substitutionl | |||||||||||||||

| Vocabulary | 2175 | 36 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 2.68 | .007 | 0.03 | 47.81 | 35 | .073 | 26.79 | 0.08^ | n/a |

Note. Comp. = composite score; WCST= Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; TMT-B = Trail Making Test part B; TMT-A = Trail Making Test part A; ID/ED = Intradimensional/Extradimensional; WM = working memory; DMTS = delayed-match-to-sample VF= verbal fluency; d = weighted mean effect size; K = number of studies; N = number of participants; v = random effects variance component; Q = heterogeneity; I2 = percentage of total variability in the set of effect sizes due to true heterogeneity; – = Too few IQ and education matched samples to conduct analysis (k<5).

1 outlier excluded (d = 3.57): with this outlier included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.83.

1 outlier excluded (d = 2.52): with this outlier included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.75.

1 outlier excluded (d = 2.14): with this outlier included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.61.

1 outlier excluded (d = 2.66): with this outlier included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.57.

1 outlier excluded (d = 1.96): with this outlier included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.55.

1 outlier excluded (d = 2.96): with this outlier included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.60.

2 outliers excluded (d = 2.66, d = 2.96): with these outliers included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.54.

1 outlier excluded (d = 2.56): with this outlier included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.54.

2 outliers excluded (d = 4.90, d = 2.55): with these outliers included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.83.

1 outlier excluded (d = 2.12): with this outlier included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.45.

1 outlier excluded (d = 3.20): with this outlier included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.56.

1 outlier excluded (d = 2.10): with this outlier included, the weighted mean effect size was d = 0.61.

Non-significant (p > .05).

Figure 1.

Weighted mean effect sizes for all analyses. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. Compared to healthy control participants, patients with MDD are significantly impaired on all tasks. EF composite measures are indicated with diamond symbols, and individual measures within each EF component by circle symbols in the same color. Pink circles indicate non-EF comparison measures. The solid vertical line indicates the psychomotor speed composite score effect size: measures for which the lower error b ar (95% confidence interval) does not pass the grey line have significantly larger effect sizes than the psychomotor speed effect size. Comp. = composite score; WCST = Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; TMT-B = Trail Making Test part B; TMT-A = Trail Making Test part A; ID/ED = Intradimensional/Extradimensional; WM = working memory; DMTS = delayed-match-to-sample; VF = verbal fluency.

Table 4.

Simultaneous Moderator Regression Analyses

| DV | IV | Beta | 95% Confidence Interval |

B | SE | p | K | N | QB(df) | QW(df) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||||||||

| Inhibition: | |||||||||||

| Stroop Interference | Severity | 0.20 | -0.47 | 0.86 | 0.057 | 0.098 | .6 | 17 | 1482 | 0.70 (3) | 12.2 (13) |

| Age | 0.12 | -0.58 | 0.82 | 0.003 | 0.008 | .7 | |||||

| Medication | 0.18 | -0.44 | 0.81 | 0.001 | 0.002 | .6 | |||||

| Inhibition Comp. | Severity | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.64 | 0.100 | 0.050 | .045* | 43 | 3260 | 6.11 (3) | 38.69 (39) |

| Age | 0.08 | -0.22 | 0.37 | 0.002 | 0.004 | .6 | |||||

| Medication | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.64 | 0.003 | 0.002 | .046* | |||||

| Shifting: | |||||||||||

| WCST | Severity | 0.40 | -0.03 | 0.83 | 0.156 | 0.086 | .069# | 23 | 1943 | 3.36 (3) | 20.91 (19) |

| Age | -0.01 | -0.41 | 0.39 | 0.000 | 0.005 | .9 | |||||

| Medication | 0.18 | -0.25 | 0.62 | 0.002 | 0.002 | .4 | |||||

| TMT-B | Severity | 0.27 | -0.10 | 0.63 | 0.100 | 0.069 | .2 | 27 | 2787 | 8.69 (3) | 23.46 (23) |

| Age | 0.33 | -0.02 | 0.68 | 0.010 | 0.005 | .066# | |||||

| TMT-A (Comparison Condition) | Medication | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 0.004 | 0.002 | .048* | ||||

| Severity | 0.09 | -0.36 | 0.54 | 0.030 | 0.076 | .7 | 22 | 2756 | 1.69 (3) | 18.80 (18) | |

| Age | 0.02 | -0.42 | 0.46 | 0.001 | 0.007 | .9 | |||||

| Medication | 0.29 | -0.15 | 0.74 | 0.003 | 0.002 | .2 | |||||

| Shifting Comp. | Severity | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.55 | 0.089 | 0.040 | .025* | 55 | 5116 | 6.71 (3) | 54.44 (51) |

| Age | 0.11 | -0.14 | 0.36 | 0.003 | 0.003 | .4 | |||||

| Medication | 0.18 | -0.08 | 0.43 | 0.001 | 0.001 | .2 | |||||

| Verbal Working Memory: | |||||||||||

| Forward Digit Span | Severity | -0.01 | -0.43 | 0.41 | -0.003 | 0.063 | .9 | 22 | 1782 | 5.34 (3) | 17.33 (18) |

| Age | -0.06 | -0.48 | 0.36 | -0.002 | 0.006 | .8 | |||||

| Medication | 0.49 | 0.07 | 0.91 | 0.004 | 0.002 | .022* | |||||

| Backward Digit Span | Severity | 0.43 | -0.00 | 0.87 | 0.155 | 0.079 | .051# | 17 | 1662 | 7.63 (3) | 14.42 (13) |

| Age | -0.29 | -0.76 | 0.17 | -0.011 | 0.009 | .2 | |||||

| Medication | 0.40 | -0.06 | 0.86 | 0.004 | 0.003 | .086# | |||||

| Maintenance Comp. | Severity | 0.14 | -0.23 | 0.51 | 0.038 | 0.052 | .5 | 26 | 2055 | 7.85 (3) | 21.37 (22) |

| Age | 0.14 | -0.23 | 0.51 | 0.003 | 0.004 | .5 | |||||

| Medication | 0.53 | 0.16 | 0.90 | 0.004 | 0.001 | .005* | |||||

| Manipulation Comp. | Severity | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.136 | 0.063 | .031* | 20 | 2080 | 9.04 (3) | 17.27 (16) |

| Age | -0.11 | -0.50 | 0.28 | -0.003 | 0.005 | .6 | |||||

| Medication | 0.29 | -0.10 | 0.68 | 0.003 | 0.002 | .139 | |||||

| Verbal WM Comp.a | Severity | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.080 | 0.041 | .049* | 30 | 2840 | 17.05 (4) | 24.93 (25) |

| Age | 0.02 | -0.29 | 0.34 | 0.000 | 0.003 | .9 | |||||

| Medication | 0.55 | 0.21 | 0.89 | 0.004 | 0.001 | .001* | |||||

| Task | 0.10 | -0.23 | 0.43 | 0.043 | 0.074 | .6 | |||||

| Visuospatial Working Memory: | |||||||||||

| Visuospatial WM Comp. | Severity | 0.30 | -0.15 | 0.75 | 0.095 | 0.073 | .2 | 17 | 1455 | 7.64 (3) | 12.41 (13) |

| Age | -0.03 | -0.49 | 0.43 | -0.001 | 0.006 | .9 | |||||

| Medication | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.005 | 0.002 | .035* | |||||

| Verbal Fluency: | |||||||||||

| Semantic VF | Severity | 0.72 | 0.32 | 1.12 | 0.408 | 0.116 | <.001* | 17 | 1643 | 13.97 (3) | 13.95 (15) |

| Age | 0.00 | -0.40 | 0.39 | 0.000 | 0.007 | .9 | |||||

| Medication | 0.22 | -0.16 | 0.60 | 0.003 | 0.003 | .3 | |||||

| Phonemic VF | Severity | 0.66 | 0.28 | 1.03 | 0.194 | 0.057 | .001* | 29 | 2850 | 11.85 (3) | 24.79 (25) |

| Age | 0.16 | -0.19 | 0.50 | 0.003 | 0.004 | .4 | |||||

| Medication | 0.32 | -0.04 | 0.67 | 0.002 | 0.001 | .085# | |||||

| VF Comp.b | Severity | 0.58 | 0.24 | 0.91 | 0.203 | 0.060 | .001* | 34 | 3466 | 15.61 (3) | 29.73(29) |

| Age | 0.07 | -0.23 | 0.37 | 0.002 | 0.004 | .7 | |||||