Abstract

While tendons typically undergo primarily tensile loading, the human supraspinatus tendon (SST) experiences substantial amounts of tension, compression, and shear in vivo. As a result, the functional roles of the extracellular matrix components, in particular the proteoglycans (PGs), are likely complex and important. The goal of this study was to determine the PG content in specific regions of the SST that exhibit differing mechanical function. The concentration of aggrecan, biglycan, and decorin were determined in six regions of the human SST using immunochemical techniques. We hypothesized that: aggrecan concentrations would be highest in areas where the tendon likely experiences compression; biglycan levels would be highest in regions likely subjected to injury and/or active remodeling such as the anterior regions; decorin concentrations would be highest in regions of greatest tensile stiffness. Our results generally supported these hypotheses and demonstrated that aggrecan and biglycan share regional variability, with increased concentration in the anterior and posterior regions and smaller concentration in the medial regions. Decorin, however, was in high concentration throughout all regions. The data presented in this study represent the first regional measurements of PG in the SST. Together with our previous regional measurements of mechanical properties, these data can be used to evaluate SST structure-function relationships. With knowledge of the differences in specific PG content, their spatial variations in the SST, and their relationships to tendon mechanics, we can begin to associate defects in PG content with specific pathology, which may provide guidance for new therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: ELISA, extracellular matrix, shoulder, biomechanics

INTRODUCTION

Tendon is a connective tissue that primarily undergoes tensile load. While the most abundant protein is type-I collagen [1], proteoglycans (PG), comprising 1–5% of tendon dry weight, are extracellular matrix proteins that play an important role in collagen fibril formation and in resisting compressive loads [1–4]. There are a number of PGs in tendon, each with a distinct core protein and numerous attached glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains. The most common PG found in tendon is decorin, a small leucine-rich PG [1–3]. Other PGs expressed in tendon include biglycan, aggrecan, fibromodulin, versican, syndecan, and perlecan [5,6]. It has been suggested that these PGs may play a role in functions such as fibrillogenesis, fiber lubrication, and aggregation [7,8]. The mechanical role of PGs in tendon remains controversial, with some studies demonstrating an important role [9] and others reporting no role [10]. The present study aims to characterize the PGs decorin, biglycan, and aggrecan in the human supraspinatus tendon (SST). Of the four muscle-tendon complexes comprising the shoulder rotator cuff, the SST is the most commonly injured [11–13]. While tendons typically undergo primarily tensile loading, the SST likely experiences multi-axial and heterogeneous loads due to the wide range of motion of the shoulder [14], contact with the coracoacromial arch [15,16], its position over the humeral head [17], and interaction with other rotator cuff tendons [18]. In addition, the insertion site supports multi-axial loading in vivo [11–13,19,20]. These functional requirements are matched by regional variations in longitudinal and transverse tensile properties as well as collagen fiber alignment [21,22]. It is unknown whether PGs exhibit a similar regional variation.

Decorin, a small leucine-rich proteoglycan with a core protein of approximately 40 kDa in size, has one GAG chain consisting of chondroitin sulfate (CS) and is the most abundant PG found in tendons. It has been shown to play a role in collagen fibrillogenesis and has been postulated to help support tensile loading by providing cross-links between collagen fibers [8]. Biglycan, another small leucine-rich PG, shows significant sequence homology to decorin, however, it contains two CS or dermatan sulfate (DS) GAG chains. Its specific role is largely unknown, but it is present in the short-term repair response to injury [23]. In addition, both biglycan and aggrecan synthesis increase two-fold and four-fold, respectively, under compressive load during in vitro culture testing [24].

Aggrecan, with a core protein size of approximately 250 kDa, forms large aggregates with hyaluronan, which itself can be as large as several million kilodaltons. Primarily known as a structural component of articular cartilage, aggrecan can contain as many as 100 GAGs which are primarily CS and keratin sulfate (KS) chains. These highly negatively charged polysaccharides provide a hygroscopic environment which aides in water recruitment and resistance of compressive loads [25].

Despite the functional association with PGs in cartilage, little is known regarding the relative composition of specific PGs or their functional role in tendon. In regard to non-collagenous composition, most of the tendon literature has focused on the overall GAG content [26]. However, given the inter- and intra-variability of GAG content amongst specific PGs, GAG composition is only a surrogate marker for PG composition, and not representative of individual PG content nor of specific PG core proteins (e.g., decorin, biglycan, aggrecan). The characterization of SST PG content by measuring the specific PG core proteins has not been previously reported. Therefore, the objective of this study was to first develop methodology suitable to assess PG in tendon, and second, to determine the PG content in specific regions of the SST that exhibit varying mechanical properties [21,22]. We hypothesize that: 1) aggrecan will be present at the highest levels where tendon is likely to undergo compression, such as the bursal regions, 2) biglycan concentrations will also be highest in the bursal regions as well as in regions likely subjected to injury or active remodeling, such as in anterior regions [24], and 3) decorin will be ubiquitous throughout the SST but most abundant in areas subjected largely to tension (rather than compression) such as in the medial region away from the insertion site.

METHODS

Sample Preparation

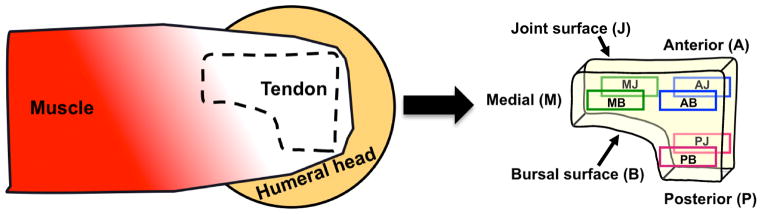

A total of 121 individual samples of suitable size for analysis were harvested from 27 cadaver shoulders. Samples used in this study were taken from the same cadaveric specimens evaluated in previous mechanical studies [21,22]; specifically, biochemical tissue samples were acquired from locations immediately adjacent to each mechanical test strip. The number of specimens for each region that were evaluated for each PG is noted in Table 1. The average age of the 27 cadavers that were studied was 56 ± 14 years. Donors had no reported history of injury to the shoulder and SSTs and partial or full thickness tears were excluded from study. All soft tissue was removed from around the SST, which was separated from the joint capsule and any remaining muscle fibers. The SST was sharply excised from its humeral insertion. Hydration of the SST was maintained using phosphate buffered saline (PBS) throughout dissection and sample preparation. Rectangular full-thickness samples (~3 × 4 mm) were cut from each SST’s anterior (A), medial (M), and posterior (P) regions. Samples were rapidly thawed in cold water and the dissection occurred over 1–1.5 hrs using PBS (no protease inhibitors) rinses to maintain the tissue hydration. These specimens were then bisected through their thickness with a scalpel to produce bursal (B) and joint (J) samples yielding six location-specific regions (Fig. 1): anterior-bursal (AB), anterior-joint (AJ), posterior-bursal (PB), posterior-joint (PJ), medial-bursal (MB), and medial-joint (MJ) (n=16 to 22 samples per region, Table 1). The samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and minced into 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5mm cubes using scalpel blades. The temperature of the tissue was maintained with liquid nitrogen throughout this process. Samples were then homogenized using a Spex Freezer Mill (Metuchen, NJ) with the following settings (5 min pre-cool, 3 impaction cycles at 10Hz for 2 mins with 1 min pause intervals). A small aliquot was saved for lyophilization and dry weight determination.

Table 1.

Number of specimens assayed in each region for each proteoglycan

| AB | AJ | MB | MJ | PB | PJ | Total/PG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decorin | 21 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 18 | 121 |

| Aggrecan | 22 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 16 | 119 |

| Biglycan | 21 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 112 |

AB: Anterior Bursal, AJ: Anterior Joint, MB: Medial Bursal, MJ: Medial Joint, PB: Posterior Bursal, PJ: Posterior Joint

Fig. 1.

Harvest location of human supraspinatus tendon samples.

Proteoglycan Extraction

Each tendon was extracted using 4 M guanidine-HCl/0.5 M sodium acetate and 1X protease inhibitor (Complete, Roche, Indianapolis, IN) in glass scintillation vials at 4 °C for 48–72 hours under constant agitation using a magnetic stir-plate (650 rpm). After 24 hours, samples that were not completely homogeneously suspended underwent manual agitation using micropipette tip. Adequate extraction and suspension was confirmed qualitatively by white color and viscous appearance. Samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 15,000 × g at 4 °C and the supernatant was retrieved and immediately transferred into Slide-A-Lyzer Dialysis cassettes (0.5–3mL 20kDa pore size, #66003 Pierce Scientific). The extract was then extensively dialyzed against ddH2O. The dialysate was removed and centrifuged for 15 min at 15,000 × g at 4 °C. A speed-vac (Thermo Savant, Asheville, NC) was utilized to dry the dialyzed extract. Samples were reconstituted at a standardized dry weight/buffer concentration of PBS with the 1X protease inhibitor used above.

PG ELISA

PG content was determined through sandwich ELISA techniques. Decorin content was determined using the Decorin Duoset ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and aggrecan using the PG-EASIA Kit (# KAP1461, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For these two PGs, the assay was performed as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The recommended dilution of kit-provided standards was used. Dilutions of samples were individually determined by sequential serial dilutions. Of note, aggrecan determination required a wide range of dilutions to reliably read against the standard curves.

In respect of aggrecan the assay was commercialized and designed using antibodies raised against aggrecan molecules purified from cartilage and as such the precise immune-epitopes are not reported. However the antibody is known to react with the hyularonan binding region of the core protein and as such we can use this assay to determine levels of aggrecan but can not exclusively relate to its being only aggrecan core protein sicne it might have some signal coming from aggrcan associated gag side chans or remements thereof. Biglycan and decorin assays utilize recombinant proteins and in these cases the results are a direct relationship to the concentration of the core protein of each PG.

Biglycan content was determined through a sandwich ELISA technique using a custom-developed assay in our laboratory, as described below. In this assay the L-15 anti-biglycan antibody SC-27936 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was utilized as the capture antibody, anti-human biglycan biotinylated antibody (#BAF2667, R&D Systems) as the detection antibody, and recombinant human biglycan (#2667-CM, R&D Systems) as the standard. In each well of clear polystyrene microplates (R&D system), 0.1 μg of the L-15 anti-biglycan antibody was incubated overnight at room temperature. After aspirating and washing (1X PBS and 0.05% Tween) three times (buffer used throughout), the plates were blocked using 300 μL of 1.0% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for a minimum of 1 hr. The wells were again washed with buffer three times. Samples (100 μL) were allowed to equilibrate with the capture antibody at room temperature for two hours. The plates were then aspirated and washed three times. The capture antibody-sample complex was allowed to incubate with the biotinylated detection antibody at a concentration of 250 ng/mL (100 μL) for two hours. The plates were again aspirated and washed three times. The capture antibody-sample-detection antibody complex was then conjugated to streptavidin-HRP (DY998, R&D Systems) by incubating the streptavidin-HRP (100 μL) with the complex for 20 min at room temperature. Substrate solution (100 μL/well) (DY999, R&D System) was added to each well and after 20 min of incubation, the optical density was measured at 450-nm using a BioTek Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). The standard curve (range 4 ng/mL-62.5 pg/mL) was determined by measuring the optical density of the recombinant human biglycan at 450-nm, and fitting the data points using a 4-parameter logistic curve fit.

Statistics

The overall presence of regional variability for each proteoglycan was assessed using Kruskal-Wallis tests with a significance level of p<0.05. A total of nine comparisons between regions within the bursal portions, between regions within the articular portions, and across bursal and joint portions within a region were made using Mann-Whitney U tests with a significance level of p< 0.05.

RESULTS

A fundamental obstacle in studying the SST extracellular matrix composition is its inherent resistance to disruption and homogenization. In this study, we incorporated the use of a freezer-mill which greatly aided in homogenization and subsequent PG extraction, which as confirmed by repeated, immeasurable quantities of GAG in the extraction residue (by dye-binding GAG assay). To quantify decorin, aggrecan, and biglycan, we expanded on existing methodology for extraction of the components and furthermore we were able to consistently measure core proteoglycan content with expected variability with sandwich ELISA techniques. The antibodies used in the assays were PG specific and did not have significant cross-reaction with other proteoglycans. The ELISA assays were very sensitive measures of PG in our samples with sensitivity thresholds of 31 pg/mL, 14,000 pg/mL, and 62 pg/mL for decorin, aggrecan, and biglycan, respectively.

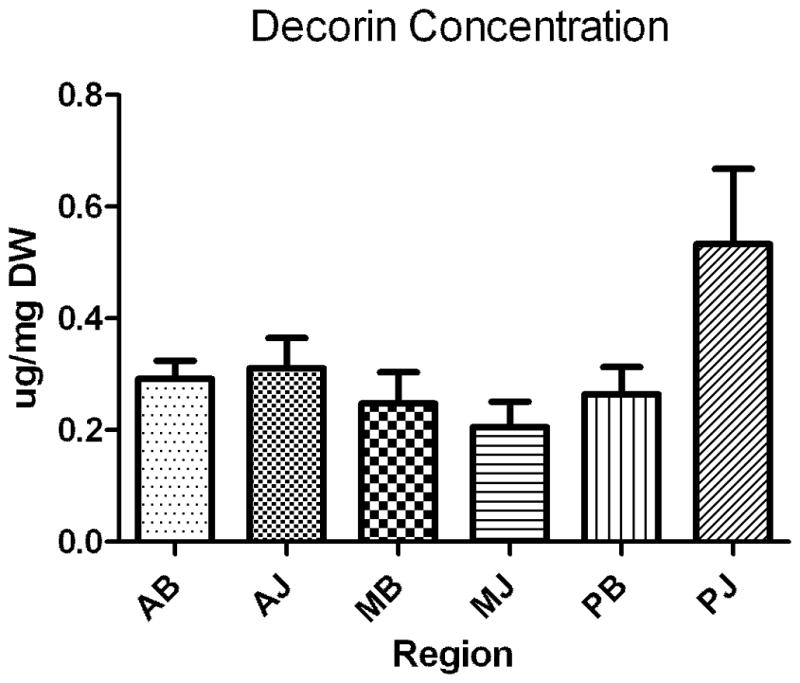

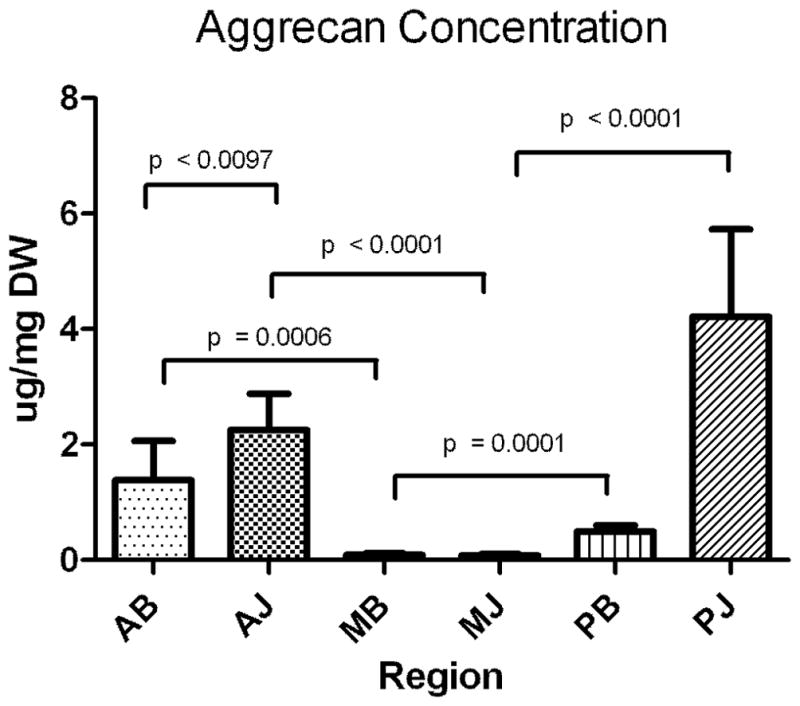

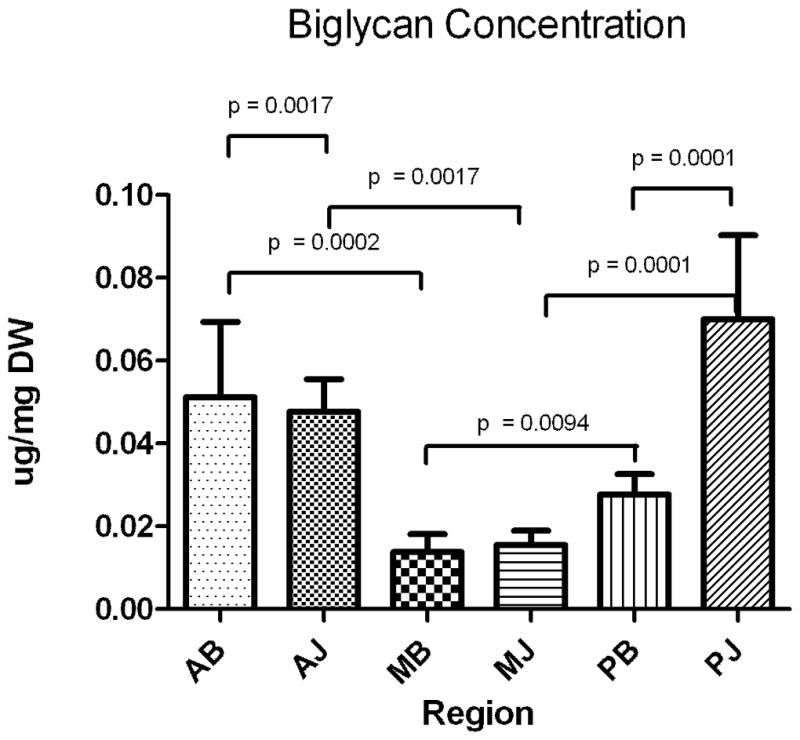

The average concentration (μg/ml) of each PG is normalized by sample dry weight (μg/mg) and shown in Figs 2A–C and Table 2. For decorin, there were no significant differences between any of the six regions as decorin was present consistently throughout (Fig. 2A). For aggrecan, significant differences were observed across regions (Fig 2B, Table 2) with concentrations statistically greater in the anterior and posterior bursal regions when compared to the medial region. There were no differences between aggrecan concentration in the anterior and posterior bursal regions. The concentration of aggrecan in the joint region showed a similar distribution (Fig 2B, Table 2). Biglycan shared a similar, statistically significant distribution between the joint and bursal regions (Fig 2C, Table 2). When the anterior, posterior, and medial regions were compared, aggrecan was present in significantly greater concentrations in the anterior joint region in comparison to the anterior bursal region (Fig 2C, Table 2). Statistical differences between the bursal and joint segments were not observed in either the posterior or medial regions (Fig 2C, Table 2). Biglycan shared a similar distribution, except there was a significantly increased concentration of biglycan in the posterior joint region when compared to the posterior bursal region (Fig 2C, Table 2). No statistical difference was found when comparing the medial bursal and medial joint regions (Figure 2C, Table 2).

Fig. 2.

A–C. Concentration of proteoglycans decorin (A), aggrecan (B), biglycan (C) as expressed in μg/mg dry weight in the assayed regions. Only significant comparisons have p values depicted. AB, anterior bursal; AJ, anterior joint; MB, medial bursal; MJ, medial joint; PB, posterior bursal; PJ, posterior joint.

Table 2.

Mean concentration of proteoglycans aggrecan and biglycan as expressed in μg/mg of dry weight.

| Aggrecan | Biglycan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | Concentration (μg/ml) | P Valuea | Comparison | Concentration (μg/ml) | P Valuea |

| Bursal Region | |||||

| AB vs MB | 1.4, 0.091 | 0.0006 | AB vs MB | 0.051, 0.014 | 0.0002 |

| MB vs PB | 0.091, 0.50 | 0.0001 | MB vs PB | 0.014, 0.028 | 0.009 |

| AB vs PB | 1.4, 0.50 | 0.2 | AB vs PB | 0.051, 0.028 | 0.2 |

| Joint Region | |||||

| AJ vs MJ | 2.3, 0.084 | <0.0001 | AJ vs MJ | 0.048, 0.016 | 0.002 |

| MJ vs PJ | 0.084, 4.2 | <0.0001 | MJ vs PJ | 0.016, 0.070 | 0.0001 |

| AJ vs PJ | 2.3, 4.2 | 0.7 | AJ vs PJ | 0.048, 0.070 | 0.8 |

| Anterior, Posterior, Medial Regions | |||||

| AB vs AJ | 1.4, 2.3 | 0.01 | AB vs AJ | 0.051, 0.048 | 0.002 |

| PB vs PJ | 0.50, 4.2 | 0.3 | PB vs PJ | 0.028, 0.070 | 0.0001 |

| MB vs MJ | 0.091, 0.084 | 0.8 | MB vs MJ | 0.014, 0.016 | 0.8 |

Note: there were no significant differences across region for decorin.

Mann-Whitney Test, two tailed, with a P-value (P < 0.05).

Bold denotes significance.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to first develop methodology and techniques suitable to assess PG content in the human SST, and second, to determine the PG content in specific regions of the SST that exhibit varying mechanical properties from previous studies. While some qualitative and gene expression information exists on various proteoglycans that make up the tendon [27,28], to the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first quantitative report of individual PG protein content in distinct regions of the SST.

Regarding methodological development, although extraction of PGs with chaotropic agents such as guanidine after various tissue disruption methods have been well described in the cartilage literature, little information exists describing the effectiveness of extraction in tendon, and in particular, the SST [29,30]. In this study, the use of a freeze mill aided greatly in homogenization, which consistently provided extraction of greater than 90% of total GAGs, as confirmed by a dye binding assay (data not shown). In addition, we demonstrated that the sandwich ELISA can be utilized in conjunction with this technique to reliably assess the concentration of various PGs within this clinically important, yet understudied tendon. Notably, our study measured the concentration of aggrecan, decorin, and biglycan proteins, rather than just the GAGs as done previously in tendon [31], and the data are presented on a PG protein-weight basis normalized by dry weight. Therefore, these data do not relate specifically to the combined weight of the core protein plus GAG content. This is important considering that the aggrecan protein molecule alone is ten times larger in molecular weight than either decorin or biglycan and potentially has hundreds of attached GAG chains compared to the one or two chains attached to decorin and biglycan, respectively [6].

As decorin is the most predominant tendon PG in general, it is commonly considered the PG most associated with tissues undergoing tension [1–3]. While the SST primarily experiences tension, our previous mechanical studies indicate clear variations in longitudinal tensile modulus across regions with the medial regions having the greatest values [21,22]. As a result, we hypothesized that the concentration of decorin would mirror these variations in tensile modulus and be highest modulus in the medial regions. Results indicate that decorin appears to be ubiquitous, with no particular regional variation in the SST. This finding was surprising and may indicate that decorin is not particularly sensitive to changes in mechanical properties or collagen fiber organization. This finding is consistent with previous reports suggesting that glycosaminoglycan does not contribute to ligament tensile mechanics [10].

Conversely, aggrecan is the most predominant PG in tissues commonly subjected to compression, such as articular cartilage [24,25]. Located between the humeral head inferiorly and the coracoacromial arch superiorly, in addition to tension, the SST may experience compressive and shear loads, especially near its insertion site. As a result, we expected higher aggrecan expression near the insertion and at the bursal surface under the acromion. Consistent with our hypothesis, we did find increased aggrecan in the anterior (both bursal and joint) and posterior (joint) regions of the SST with decreased amounts elsewhere. This was generally consistent with our previous measurements of tensile mechanics, which showed decreased moduli in regions where the aggrecan concentration was highest.

While biglycan and aggrecan share some expected findings, we hypothesized to find biglycan highest in regions likely subjected to injury and/or active remodeling [23,24]. Consistent with our expectations, we did find increased biglycan levels in the anterior regions (both bursal and joint) and these locations correspond to regions where tears often initiate clinically [11]. Surprisingly, we also found increased biglycan levels in the posterior joint regions. This result was not expected as there is no data in the literature to support that this region is where tears initiate or where active remodeling would be expected. This finding, coupled with high aggrecan levels in this region, is the subject of a future study.

This study is not without limitations. First, although we limited our cadaver shoulder specimens to those without significant shoulder pathology and rotator cuff tears, there is always some inherent variation in size and this resulted in a small number of specimens being too small to perform the extraction and analysis. We also did not attempt to measure levels of SST degeneration (other than excluding tears) as some level of degeneration is to be expected of SSTs in the age range studied. Although the locations of the samples for biochemical analysis were controlled and consistent, there was a small amount of variation in these locations between shoulder specimens due to small variations in anatomy. Nevertheless, the relatively little variation within groups and the statistically significant comparisons suggests that these minor differences did not affect our results However, the conclusions drawn by this study are not hindered by these limitations, as we sought only to describe the interregional variability of each PG and not to make a direct comparison between various PGs. Furthermore, the variation in GAG content between like protein cores precludes inter-PG comparison. Thus, the total weight contribution of PG core plus GAG chains cannot be quantitatively expressed. Other methods including mass spectrometry and specialized biochemical assays may aide in this determination. Concomitantly, as the assay of individual PG content in tendons has not been described elsewhere, there exists no confirmatory information of the quantity of each PG core. Our data is supported by qualitative data on the type of PG that comprise a tendon [27,28].

In summary, the data presented in this study represent the first regional measurements of PG protein core in the SST. Given our previous regional measurements of mechanical properties [21,22], these data can be used to evaluate structure-function relationships and may aid in understanding the roles of these PGs in tendon mechanics. With knowledge of the differences in specific PG content, their spatial variations in the SST, and their relationships to tendon mechanics, we can begin to associate defects in PG content with specific pathology, which may provide a platform for new therapeutic interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

Because of the variety of loads encountered by the supraspinatus tendon in vivo, the present work aimed to identify regional variations of proteoglycans believed to be correlated with local tissue mechanics, specifically decorin, biglycan, and aggrecan. While decorin concentrations did not vary across tendon locations, aggrecan and biglycan levels were greater in the anterior and posterior regions near the tendon-bone insertion believed to be sites of compressive loading and injury initiation. This is in agreement with findings suggesting structure-function relationships between aggrecan and compressive stiffness as well as findings linking biglycan to wound healing.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper. This study was funded by NIH/NIAMS AR055598 which did not influence the results of the project.

References

- 1.Vogel KG, Meyers AB. Proteins in the tensile region of adult bovine deep flexor tendon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999:S344–55. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199910001-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Derwin KA, Soslowsky LJ. A quantitative investigation of structure-function relationships in a tendon fascicle model. J Biomech Eng. 1999;121:598–604. doi: 10.1115/1.2800859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derwin KA, Soslowsky LJ, Kimura JH, Plaas AH. Proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycan fine structure in the mouse tail tendon fascicle. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:269–77. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin TW, Cardenas L, Soslowsky LJ. Biomechanics of tendon injury and repair. J Biomech. 2004;37:865–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jozsa L, Kannus P. Human tendons. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1997. p. 576. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rees SG, Flannery CR, Little CB, Hughes CE, Caterson B, Dent CM. Catabolism of aggrecan, decorin and biglycan in tendon. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 1):181–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldock C, Koster AJ, Ziese U, Rock MJ, Sherratt MJ, Kadler KE, Shuttleworth CA, Kielty CM. The supramolecular organization of fibrillin-rich microfibrils. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:1045–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang G, Ezura Y, Chervoneva I, Robinson PS, Beason DP, Carine ET, Soslowsky LJ, Iozzo RV, Birk DE. Decorin regulates assembly of collagen fibrils and acquisition of biomechanical properties during tendon development. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1436–49. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danielson KG, Baribault H, Holmes DF, Graham H, Kadler KE, Iozzo RV. Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:729–43. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lujan TJ, Underwood CJ, Jacobs NT, Weiss JA. Contribution of glycosaminoglycans to viscoelastic tensile behavior of human ligament. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:423–31. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90748.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt SA, Kwon YW, Zuckerman JD. The rotator interval: anatomy, pathology, and strategies for treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:218–27. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200704000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itoi E, Berglund LJ, Grabowski JJ, Schultz FM, Growney ES, Morrey BF, An KN. Tensile properties of the supraspinatus tendon. J Orthop Res. 1995;13:578–84. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100130413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakajima T, Nobuyuki R, Kazutoshi H, Taisuke T, Hiroaki F. Histologic and biomechanical characteristics of the supraspinatus tendon: Reference to rotator cuff tearing. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 1994;3:79–87. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakajima T, Hughes RE, An KN. Effects of glenohumeral rotations and translations on supraspinatus tendon morphology. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2004;19:579–85. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flatow EL, Soslowsky LJ, Ticker JB, Pawluk RJ, Hepler M, Ark J, Mow VC, Bigliani LU. Excursion of the rotator cuff under the acromion. Patterns of subacromial contact. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:779–88. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo ZP, Hsu HC, Grabowski JJ, Morrey BF, An KN. Mechanical environment associated with rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:616–20. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(98)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bey MJ, Song HK, Wehrli FW, Soslowsky LJ. Intratendinous strain fields of the intact supraspinatus tendon: the effect of glenohumeral joint position and tendon region. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:869–74. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andarawis-Puri N, Ricchetti ET, Soslowsky LJ. Interaction between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons: effect of anterior supraspinatus tendon full-thickness tears on infraspinatus tendon strain. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:1831–9. doi: 10.1177/0363546509334222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark JM, Harryman DT., 2nd Tendons, ligaments, and capsule of the rotator cuff. Gross and microscopic anatomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:713–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gohlke F, Essigkrug B, Schmitz F. The pattern of the collagen fiber bundles of the capsule of the glenohumeral joint. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 1994;3:111–28. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lake SP, Miller KS, Elliott DM, Soslowsky LJ. Effect of fiber distribution and realignment on the nonlinear and inhomogeneous mechanical properties of human supraspinatus tendon under longitudinal tensile loading. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1596–602. doi: 10.1002/jor.20938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lake SP, Miller KS, Elliott DM, Soslowsky LJ. Tensile properties and fiber alignment of human supraspinatus tendon in the transverse direction demonstrate inhomogeneity, nonlinearity, and regional isotropy. J Biomech. 2010;43:727–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corps AN, Robinson AH, Movin T, Costa ML, Hazleman BL, Riley GP. Increased expression of aggrecan and biglycan mRNA in Achilles tendinopathy. Rheumatology. 2006;45:291–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robbins JR, Evanko SP, Vogel KG. Mechanical loading and TGF-beta regulate proteoglycan synthesis in tendon. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;342:203–11. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe H, Yamada Y, Kimata K. Roles of aggrecan, a large chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, in cartilage structure and function. J Biochem. 1998;124:687–93. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon JH, Halper J. Tendon proteoglycans: Biochemistry and function. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2005;5:22–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berenson MC, Blevins FT, Plaas AH, Vogel KG. Proteoglycans of human rotator cuff tendons. J Orthop Res. 1996;14:518–25. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100140404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vogel KG, Ordog A, Pogany G, Olah J. Proteoglycans in the compressed region of human tibialis posterior tendon and in ligaments. J Orthop Res. 1993;11:68–77. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100110109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fedarko NS. Isolation and purification of proteoglycans. Experientia. 1993;49:369–83. doi: 10.1007/BF01923582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogel KG, Heinegard D. Characterization of proteoglycans from adult bovine tendon. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:9298–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riley GP, Harrall RL, Constant CR, Chard MD, Cawston TE, Hazleman BL. Glycosaminoglycans of human rotator cuff tendons: changes with age and in chronic rotator cuff tendinitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:367–76. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.6.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]