Abstract

Purpose

This study analyzed the influence of SP on growth factors related to wound healing in mice in the presence of infectious keratitis.

Methods

Naturally resistant mice were injected intraperitoneally with SP or phosphate buffered saline (PBS), infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and corneal mRNA levels of growth factors and apoptosis genes tested. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) determined protein levels, while immunohistochemistry tested distribution, macrophage phenotype, and cell quantitation. In vitro, macrophages were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) ± SP and mRNA levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and apoptosis genes tested.

Results

After SP, epidermal growth factor (EGF) mRNA and protein levels were disparately regulated early, with no differences later in disease. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and fibroblast growth factor-7 (FGF-7) mRNA and protein levels were increased after SP treatment. Enumerating dual-labeled stromal cells revealed no difference between SP- vs. PBS-treated groups in the percent of EGF-labeled fibroblasts or macrophages, but significant increases in both HGF- and FGF-7 labeled cells. Type 2 (M2) macrophages and caspase-3 mRNA levels were decreased, while B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) mRNA expression was increased after SP treatment. In vitro, mRNA levels of several pro-inflammatory cytokines and Bcl-2 were elevated, while transforming growth factor (TGF)-β was decreased after macrophage stimulation with SP (+ LPS) over LPS alone. (Mice: n=105 control; 105 experimental).

Conclusions

These data show that treatment with SP in infectious keratitis elevates growth factors, but also adversely effects disease by enhancing the inflammatory response and its sequelae.

Keywords: Bacteria, cornea, SP, growth factors, mice

INTRODUCTION

One of the most common isolates from patients with microbial keratitis is Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa).1 It is classified as an opportunistic, Gram-negative bacterium that causes keratitis in patients who are immuno-compromised and in extended wear contact lens users.2 The infection is rapid and triggers a host immune response that can lead to vision loss.3

Previous experimental studies using BALB/c [T helper cell type 2 (Th2) responder, resistant] and C57BL/6 [T helper cell type 1 (Th1) responder, susceptible] mice, have characterized their responses to P. aeruginosa infection and shown that C57BL/6 mice undergo more severe disease with corneal perforation when compared to BALB/c mice.4 These studies have examined the role of the host inflammatory response, including the production of cytokines and chemokines and the participation of various cells [e.g., macrophages,5 neutrophils,6 T lymphocytes,7 and natural killer (NK) cells8] in animal models of the disease. In macrophages, gene expression profiling has shown that Gram negative bacteria induce transcriptional activation of a common host response that induces genes in these cells expressing a type 1 macrophage (M)1 program.9 M1 polarized cells, prototypical in Th1 responder strains of mice such as C57BL/6,10 are characterized by production of Interleukin (IL)-12, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2), and high levels of nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2).11, 12 Excessive or prolonged M1 polarization can lead to tissue injury and contribute to pathogenesis, as shown in previous work from this laboratory.13 In contrast, Th2 responder mice (BALB/c) possess a higher population of alternatively activated macrophages, designated M2 cells, that produce anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10, IL-1 receptor antagonist (ra), and type II IL-1 decoy receptor,12 that up-regulate production of arginase 110 and are critical to innate immunity and disease resolution.13

An important role of the innate immune system (as well as general wound healing) in the cornea is the maintenance of homeostasis. Furthermore, in recent years, the link between the immune system and neuropeptides has been well established in numerous systems,14, 15 including models of corneal infection.16, 17 Evidence for this link includes the presence of neuropeptide receptors on and the proximity of neuronal terminals to leukocytic cells (i.e., macrophages), as well as the ability of these cells to synthesize peptides.15 One such peptide is SP that interacts with the innate immune system to stimulate the release of cytokines and augment inflammation in various experimental models.18–21

SP is an 11-amino acid member of the tachykinin family of neuropeptides that stimulates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α, and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)] through activation of transcription factor nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), creating exacerbated states of disease.22 In contrast, in non-infectious wound or trauma models, it is thought to be essential in tissue repair and has healing properties when administered exogenously.23–25 Moreover, SP-mediated cytokine release and the chemo-attraction of infiltrating leukocytes (neutrophils, macrophages) aids in healing, but can cause damage if left unregulated,22, 23 due in part to the anti-apoptotic effects of SP.26 It has been shown that levels of SP are low in BALB/c mice and, when the neuropeptide is administered exogenously via intraperitoneal injection, corneal disease is worsened with increased cellular infiltrate, bacterial number, pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, NF-κB activation, and reduced levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, all of which result in corneal perforation.16, 27

Important components in corneal wound healing after non-infectious trauma are growth factors, naturally occurring peptides that facilitate cell-to-cell communication, enhance cell proliferation and migration, and tissue function. Of interest are three classic growth factors: epidermal growth factor (EGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and fibroblast growth factor-7/keratinocyte growth factor (FGF-7/KGF). Their presence and function in non-infectious wound healing in the cornea has been firmly established,28–30 however, little information is available regarding these growth factors in a model of corneal infection.31

Thus the purpose of the current study was to test the regulatory role of SP on growth factor production in BALB/c mice, whose cornea normally does not perforate after infection.4 We provide insight into the dual role of SP in this model of bacterial infection. We show that SP has a dual role in this model of bacterial infection, unexpectedly up-regulating growth factor production. This was accompanied by macrophage specific up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, down-regulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines and up-regulation of anti-apoptotic genes, as well as a decrease in arginase-producing macrophages (M2 cells), important in stromal healing in these mice.10 All of these lead to worsened disease, despite the stimulatory effects on growth factor production and contraindicate clinical use of SP in cornea to promote wound healing, if an infection is present or suspected.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Female 8-week-old, immunologically mature, BALB/c mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines. Humane animal care conformed to the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Bacterial culture and infection

P. aeruginosa cultures [strain 19660; purchased from the American Type Culture Collection Manassas, VA] were grown in peptone tryptic soy broth as described by Hazlett et al.32 The central cornea of each anesthetized mouse was scarred with a sterile needle and a 5 μL inoculum (1×106 colony forming units per μl) applied.

SP treatment

BALB/c mice were anesthetized and injected intraperitoneally with 100 μL of sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 15 μM SP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) each day from the day before infection (d = -1) to 5 days after infection (for mRNA) or 7 days (for protein). Controls were similarly injected with sterile PBS and disease was graded after infection on days 1, 3, 5, and 7, using a clinical score system described by Hazlett et al.32

Real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Mice were sacrificed and normal and infected corneas from SP- and PBS-treated mice (n = 5/treatment/time=30 mice) were removed (1, 3, and 5 days). Each cornea was briefly stored in RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Friendsville, TX) at -20°C before processing.16

To assess transcriptional changes, mRNA levels of EGF, HGF, FGF-7, caspase-3, and B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) were tested by real-time RT-PCR (MyiQTM Single Color Real-Time PCR Detection System; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Real-Time SYBRR Green/Fluorescein PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad) was used for the PCR reaction with primer concentrations of 5 μM, as described previously by McClellan et al.16 Fold differences in gene expression were calculated after normalization with β-actin. Growth factor primer pair sequences used for real-time RT-PCR were purchased from SABiosciences (Frederick, MD). Other primers for caspase-3, Bcl-2, and β-actin have been described previously by Zhou et al.26

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

After SP or PBS treatment, translational effects (protein levels) for SP, IL-1β and the growth factors were determined using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as described previously by McClellan et al.16 SP and IL-1β protein levels were determined from individual (SP- or PBS-treated) normal and infected BALB/c corneas (n = 5/group/treatment/assay=20 mice) and uninfected duodenum (taken from 10 corneally-infected mice) at 3 days after infection. The assay sensitivity for SP was 16.8 – 43.8 pg/mL and <3.0 pg/mL for IL-1β.

For the growth factors, mice were sacrificed and individual (SP- or PBS-treated) normal and infected (1, 5, and 7 days) corneas (n=5/treatment/time=30 mice) were harvested. Corneas were individually homogenized in sterile PBS containing 0.1% TweenR 20 and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) as described previously by McClellan et al.16 The reported sensitivity of the EGF assay was 0.32 – 1.64 pg/mL. Sensitivity for the HGF and FGF-7 assays was determined by comparison to a standard curve concentration (R&D Systems). A human FGF-7 ELISA assay kit was used since a commercial murine kit was not available; others have established its effectiveness for murine samples.33

Immunostaining

Normal and P. aeruginosa-infected (5 days) eyes were enucleated from SP- or PBS-treated BALB/c mice (n=5/treatment/growth factor=30 mice), embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Sections (10 μm) were cut, fixed in acetone and incubated in blocking agent as described previously by McClellan et al.16 Sections were incubated with individual primary antibodies (goat anti-mouse EGF/HGF/FGF-7; 1:10; R&D Systems) in blocking agent for 1 hour, rinsed with buffer, and incubated for another hour with Alexa Fluor 546 donkey anti-goat IgG secondary antibody [(1:1500; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in 0.01M Tris-HCl]. In another experiment (n=5/treatment/group=60 mice), sections were incubated with antibodies specific for growth factors and macrophage-specific primary antibody rat anti-mouse F4/80 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) or fibroblast-specific rat anti-mouse ER-TR7 (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Inc.). Then, appropriate secondary antibodies were applied: Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-rat IgG (1:1500; Molecular Probes) and cyanine dye 5 conjugated donkey anti-rat (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA).

In the next experiment (n=5/treatment/group=20 mice), sections were incubated with macrophage specific primary antibody (F4/80) followed by rabbit anti-mouse NOS2 (M1 phenotype) or arginase (M2 phenotype) (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Inc.). Then, secondary antibodies (in 0.01M Tris-HCl) were applied: Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-rat IgG (1:1500; Molecular Probes) and Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes), respectively.

All sections were incubated with a nuclear acid stain (SYTOX® Green, 1:20,000; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) and controls for each of the experiments were treated the same, with exception that each primary antibody was replaced by the same host species IgG. Digital images were captured on a confocal laser-scanning microscope (TCS SP2, Leica Microsystems, Exton, PA).

Semi-quantitative cell counts

Three representative confocal micrographs (208× magnification) per group were analyzed essentially as described by Sensoo et al.34 Briefly, the total number of either F4/80 or ER-TR7 positive cells were counted in four 150 μm2 areas of each micrograph (12 areas/group). Dual labeled cells (positive for each growth factor and either specific label above) were enumerated, averaged, and expressed as a percent of the total number of F4/80 or ER-TR7 positive cells. In a separate experiment, stromal F4/80-labeled macrophages positive for NOS2 (M1 cells) or arginase (M2 cells) were counted similarly.

Macrophage culture and real-time RT-PCR

BALB/c mice (n=10 mice) were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mL of a 3% Brewer’s thioglycollate medium (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD) to stimulate macrophages into the peritoneal cavity and to increase yield.35 Seven days later, macrophages were harvested from the collected peritoneal fluid, and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 minutes. The remaining pellet was re-suspended with 10 mL of DMEM media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and a 10 μL aliquot was stained with Trypan Blue dye (1:1; Invitrogen) for cell counts with a hemacytometer. Cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 3 × 106 cells/well (n=3 wells/group) and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Media was removed and adherent cells stimulated as follows: 10 μL of 1 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS; L9143 from P. aeruginosa, serotype 10; Sigma-Aldrich) ± 1 μL of 1 × 10−9 M or 1 × 10−12 M SP36 (Sigma-Aldrich), SP alone, or media (control) to a total volume of 1 mL and incubated for 18 hours at 37°C. Then, cells and media were removed from the wells and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 7300 rpm. Pellets were reconstituted in RNA STAT-60R (Tel-Test) and processed for mRNA as described above. IL-1β, IL-18, MIP-2, TNF-α, NF-κB, and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β mRNA levels were tested as described above using previously published primer sequences.16

Statistical analysis

An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to determine the statistical significance of the real-time RT-PCR, ELISA, and cell counts. Data were considered significant at p<0.05. All experiments were repeated at least once to ensure reproducibility and data from a representative experiment are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

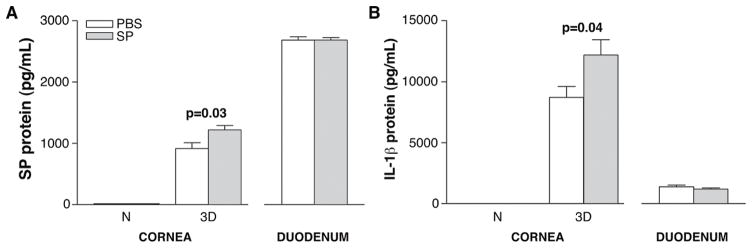

ELISA analysis of SP and IL-1β

To determine if SP injection elicited systemic effects, individual normal and infected corneas and normal duodena were harvested 3 days after infection and protein levels for SP and IL-1β assayed (Fig. 1A, B). No significant difference in SP levels was detected in either the normal cornea or duodenum after SP vs. PBS treatment. However, in the infected cornea, SP vs. PBS treatment increased local SP levels (p=0.03; Fig. 1A). IL-1β protein (Fig. 1B) was undetectable in the normal cornea in either SP- or PBS-treated mice. However, after 3 days of infection, significantly (p=0.04) increased levels of the cytokine were seen in SP- over PBS-treated samples. No differences were detected between groups in the duodenum (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

ELISA analysis of SP (A) and IL-1β(B) protein levels. Samples are taken from normal cornea and at 3 days post-infection and duodena, harvested 3 days post–infection from corneally infected mice. Samples compare mice injected with Substance P (SP) vs. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS). (n=5/group/treatment/assay=20 mice)

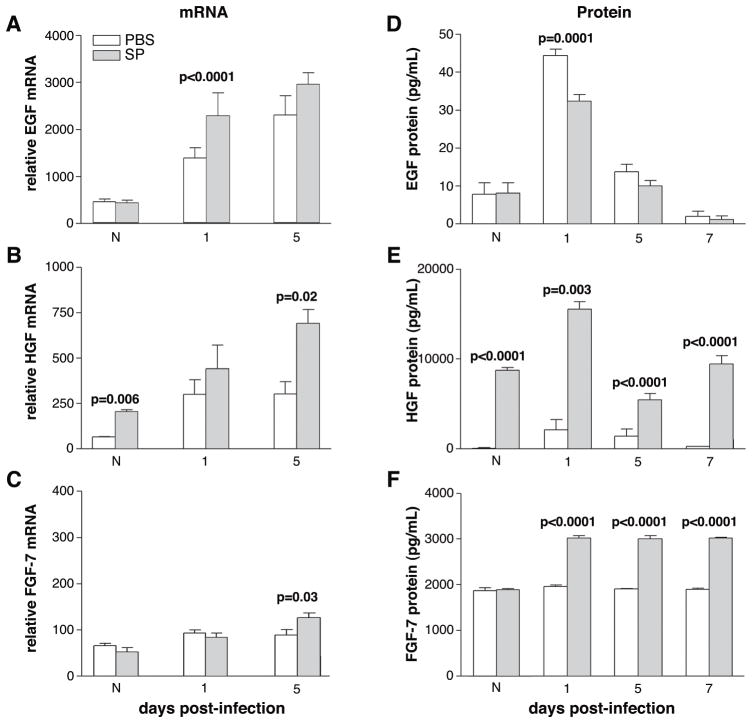

Real-time RT-PCR and ELISA analysis of the growth factors

Figure 2 shows corneal mRNA (A-C) and protein (D-F) levels of the growth factors after SP vs. PBS treatment. At 1 day after infection, EGF mRNA levels were increased (p<0.0001) in the cornea of SP- vs. PBS-treated mice (Fig. 2A), however, there was no difference between groups in the normal uninfected cornea or at 5 days after infection. EGF protein levels (Fig. 2D) were significantly decreased in the SP vs. PBS-treated group at 1 day after infection (p=0.0001), but no difference between groups was detected in the normal or after 5 or 7 days of infection. SP-treatment resulted in a significant increase in HGF mRNA expression (Fig. 2B) in the normal cornea (p=0.006) and at 5 days after infection (p=0.02), when compared to PBS controls. No difference was detected at 1 day after infection between these groups. HGF protein (Fig. 2E) was significantly increased in normal cornea and at 1, 5, and 7 days of infection after SP treatment (p<0.0001, p=0.003, p<0.0001, p<0.0001, respectively). FGF-7 mRNA expression (Fig. 2C) was significantly increased at 5 days after infection (p=0.03) following SP treatment, with no difference between groups in the normal cornea or at 1 day of infection. FGF-7 protein levels (Fig. 2F) were significantly increased after SP treatment after infection (1, 5, and 7 days) (p<0.0001 for each) with no difference between groups in the normal cornea.

FIGURE 2.

Corneal growth factor mRNA (A, B, C) and protein (D, E, F) levels after treatment with PBS vs. SP. Samples are taken from normal cornea and at 1, 5 and/or 7 days post-infection from corneally infected mice. Samples compare mice injected with Substance P (SP) vs. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS). (n=5/treatment/time/assay=60 mice; also samples used for Figure 11A, B).

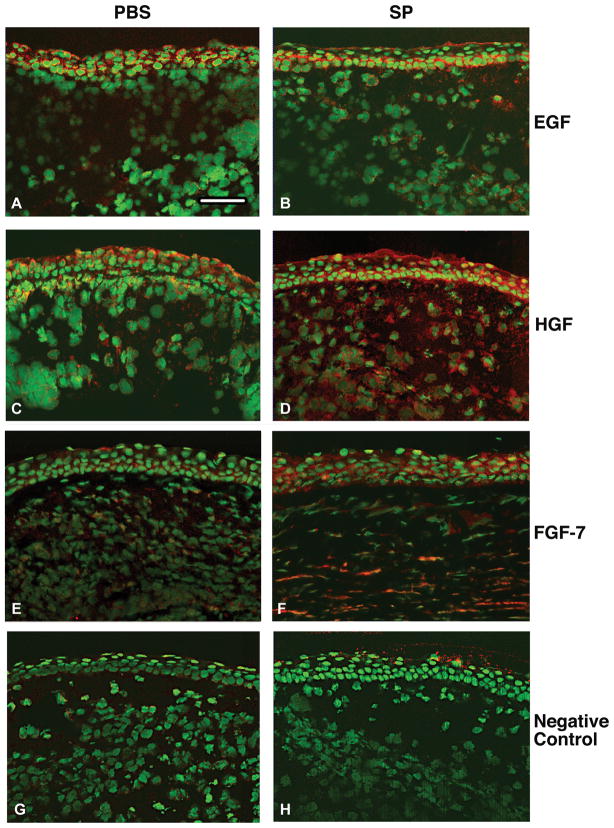

Immunofluorescent staining

Qualitative differences in immunostaining for the growth factors (red) were detected between SP- vs. PBS-treated groups (Fig. 3) after infection (5 days). Similar EGF staining was observed primarily in the epithelium in both treatment groups (Fig. 3A, B). HGF staining was observed in the epithelium and stroma, but was more intense in the SP- (Fig. 3D) vs. PBS- (Fig. 3C) treated group. More intense staining also was seen for FGF-7 after SP (Fig. 3F) vs. PBS (Fig. 3E) treatment. Representative same host species IgG controls are shown for the PBS-(Fig. 3G) and SP- (Fig. 3H) treated groups.

FIGURE 3.

Merged images of immunohistochemistry of the growth factors (red) in PBS vs. SP treated BALB/c cornea 5 days after infection. Samples compare mice injected with Substance P (SP) vs. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Nuclei are labeled with SYTOX® Green (green). Magnification=155×; Bar=80 μm. (n=5/treatment/growth factor=30 mice)

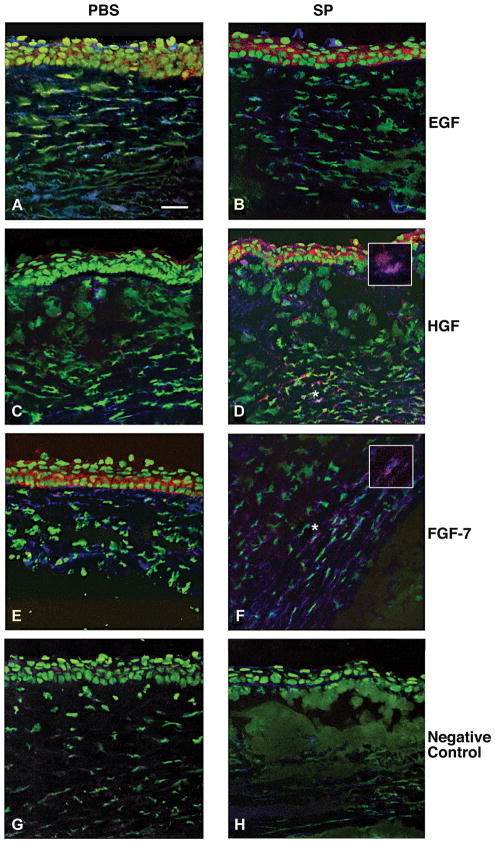

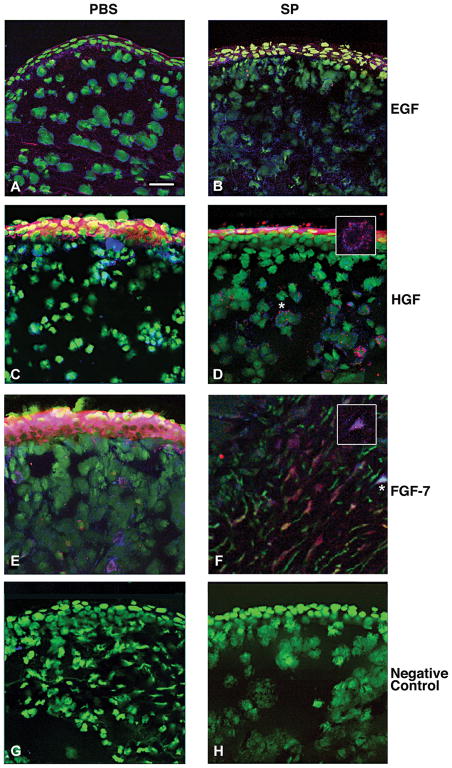

Dual-immunostaining was used to investigate the cellular origin of the growth factors. Cells were stained for an individual growth factor and either fibroblast (ER-TR7) or macrophage (F4/80) markers 5 days after infection. The results are shown in Figures 4 and 5, respectively. There was no qualitative difference in the number of dual labeled cells that stained positively for EGF (red) and ER-TR7 (blue) (Fig. 4A, B) or EGF (red) and F4/80 (blue) (Fig. 5A, B) in the PBS- vs. SP-treated groups (merged images shown). However, SP-treated mice had qualitatively more fibroblasts and macrophages that stained positively for HGF (Fig. 4D and 5D) and FGF-7 (Fig. 4F and 5F) than after PBS treatment (Fig. 4C and 5C; Fig. 4E and 5E, respectively; merged images shown). Insets (Fig. 4D, F and 5D, F) are shown at greater magnification for dual labeled fibroblasts (Fig. 4) and macrophages (Fig. 5). Representative same host species IgG controls are shown for the PBS- (Fig. 4G and 5G) and SP- (Fig. 4H and 5H) treated groups.

FIGURE 4.

Merged images of dual-immunostaining for the growth factors (red) and fibroblasts (ER-TR7, blue) in the BALB/c cornea at 5 days after infection. Samples compare mice injected with Substance P (SP) vs. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Nuclei are labeled with SYTOX® Green (green). Magnification=208×; (Insets=360×); Bar=40 μm. (n=5/group/treatment=30 mice)

FIGURE 5.

Merged images of dual-immunostaining for the growth factors (red) and macrophages (F4/80; blue) in BALB/c cornea at 5 days of infection. Samples compare mice injected with Substance P (SP) vs. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Nuclei are labeled with SYTOX® Green (green). Magnification=208×; (Insets=360×); Bar=40 μm. (n=5/group/treatment=30 mice)

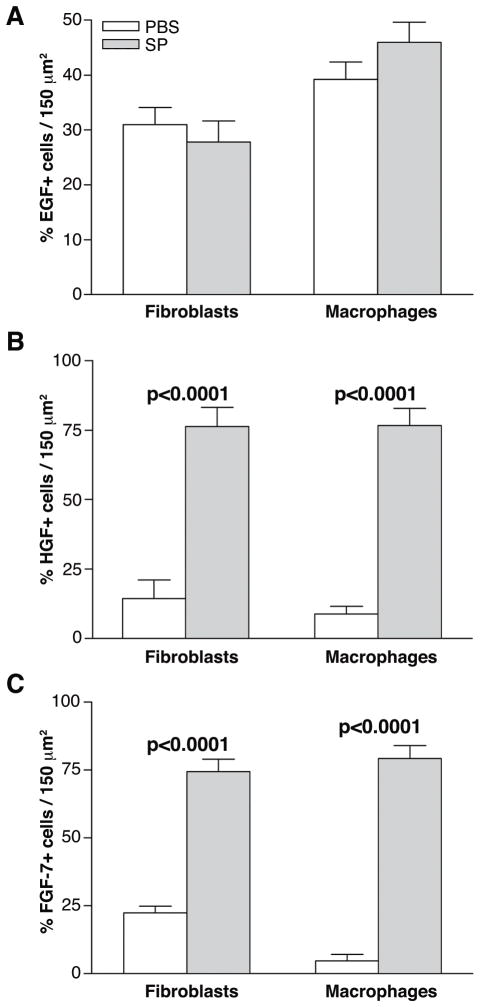

Semi-quantitative cell counts

To confirm the qualitative dual-immunostaining data, semi-quantitative cell counts were done 5 days after infection (Fig. 6). The percentage of dual labeled, EGF positive fibroblasts and/or macrophages (expressed as a percent of total fibroblast or macrophage labeling) were not significantly different between the SP- vs. PBS-treated groups (Fig. 6A). However, a significant increase in dual labeled HGF positive fibroblasts (p<0.0001) and macrophages (p<0.0001) and dual labeled FGF-7 positive fibroblasts (p<0.0001) and macrophages (p<0.0001) (expressed as a percent of total fibroblast or macrophage labeling) was seen in the SP- vs. PBS-treated controls (Fig. 6B, C).

FIGURE 6.

Semi-quantitative cell counts compared the percentage of growth factor positive cells to the total number of positively immunostained fibroblasts (ER-TR7) or macrophages (F4/80) in the stroma of the infected cornea (same mice as in Figure 5) with or without SP treatment at 5 days after infection. Samples compare mice injected with Substance P (SP) vs. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

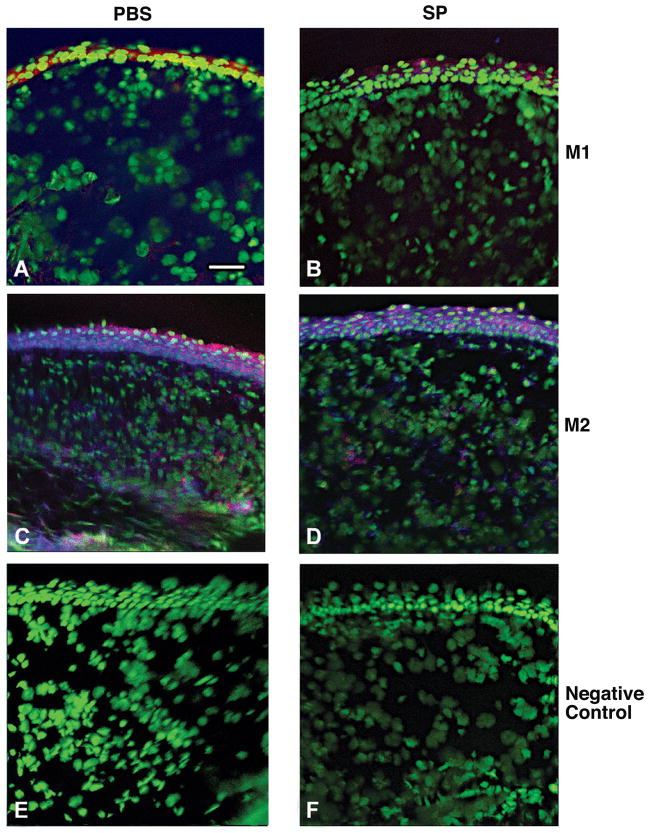

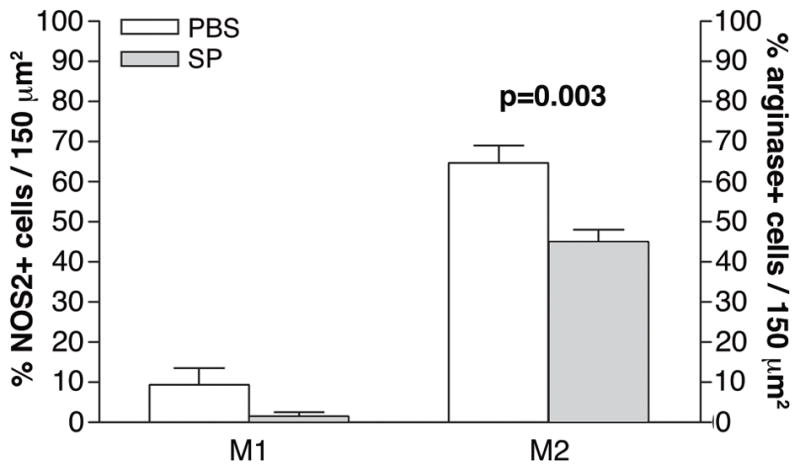

Macrophage phenotype and cell counts

Dual-immunostaining also was used to test whether SP treatment affected macrophage polarization in the stroma of the infected cornea at 5 days after infection and the data are shown in Figure 7. NOS2 positive (blue), M1 macrophages (red) were detected (merged image shown) in corneas in mice treated with PBS (Fig. 7A) or SP (Fig. 7B) and appeared similar. Arginase positive (blue), M2 macrophages (red) were also detected (merged image shown) in the infected stroma of PBS (Fig. 7C) and SP (Fig. 7D) treated mice, but appeared qualitatively decreased in the SP group. Representative same host species IgG controls are shown for the PBS- (Fig. 7E) and SP- (Fig. 7F) treated groups. At 5 days after infection, macrophages that were either arginase or NOS2 positive were quantitated and expressed as a percentage of total F4/80 positive macrophages, essentially as described above. The data are shown in Figure 8. There was no significant difference between treatment groups in the percentage of M1 macrophages, however, a significant (p=0.003) decrease in the percent of M2-labeled cells was seen after SP- vs. PBS treatment.

FIGURE 7.

Merged images of dual-immunostaining for M1 type macrophage (nitric oxide synthase-2 positive, blue) (A, B) or M2 type macrophage (arginase positive, blue) (C, D) F4/80 (red-labeled) macrophages at 5 days after infection. Samples compare mice injected with Substance P (SP) vs. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Nuclei are labeled with SYTOX® Green (green). Magnification=208×; Bar=40 μm. (n=5/group/treatment=20 mice)

FIGURE 8.

Semi-quantitative cell counts of M1 and M2 macrophages. Samples compare mice (same mice as in Figure 7) injected with Substance P (SP) vs. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

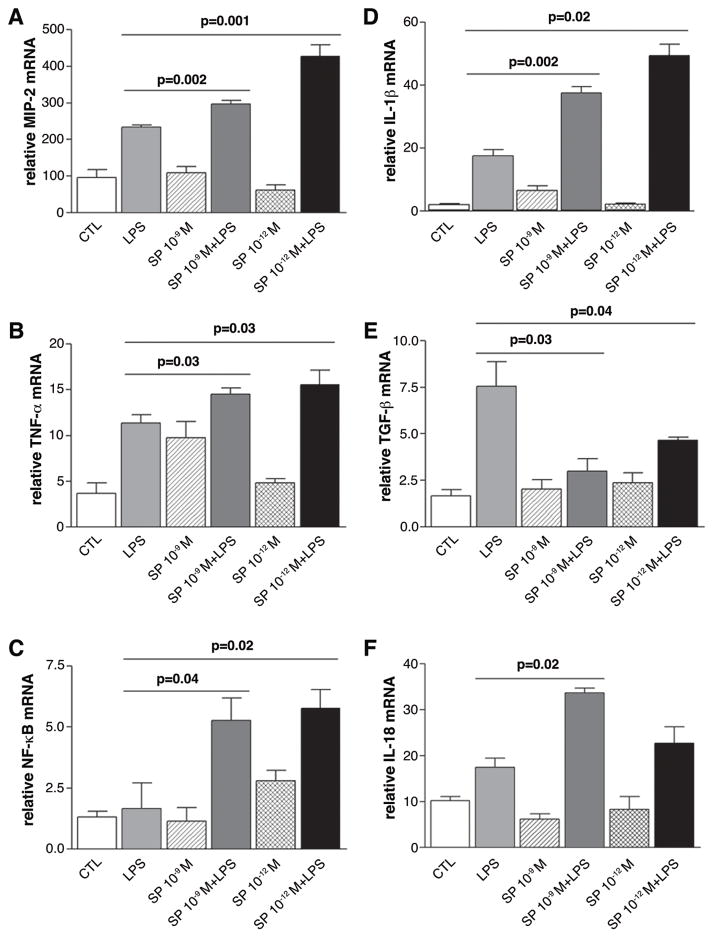

Real-time RT-PCR of macrophage cytokines

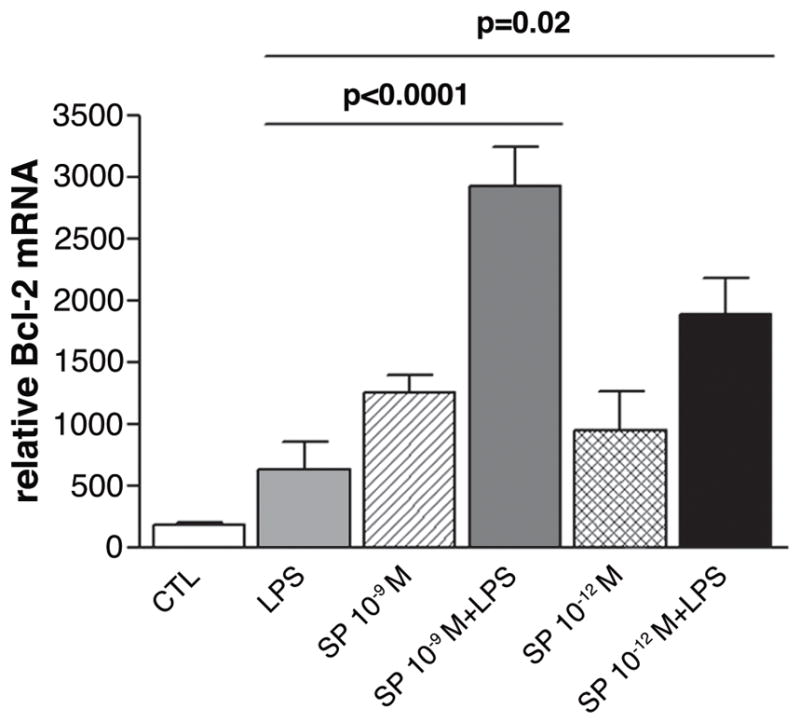

Since SP decreases the number of M2 positive cells with no difference in the M1 cell population, we next tested its effects in vitro on macrophage production of pro- (e.g., MIP-2, TNF-α, NFκB, IL-1β, IL-18; Fig. 9A-D, F) and anti-inflammatory (TGF-β; Fig. 9E) molecules to determine if, in addition to modulating growth factors, SP enhances the pro-inflammatory cytokine pathway in these cells. The data show that the effects of SP necessitated the presence of LPS and SP alone did not give similar effects. Specifically, after 18 hours of stimulation, SP (10−9 M and 10−12 M) + LPS significantly increased macrophage mRNA levels of MIP-2 (Fig. 9A; p=0.002 and p=0.001), TNF-α (Fig. 9B; p=0.03 for both), NF-κB (Fig. 9C; p=0.04 and p=0.02) and IL-1β (Fig. 9F; p=0.002 and p=0.02), while SP + LPS decreased TGF-β (Fig. 9E; p=0.03 and p=0.04) compared to stimulation with LPS alone. Both concentrations of SP (in the presence of LPS) elevated IL-18 mRNA levels, but this was significant only at the higher concentration of SP (10−9M), (Fig. 10F; p=0.02). Control wells were incubated with media alone.

FIGURE 9.

In vitro mRNA expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages. Samples compare stimulation with LPS ± Substance P (SP) (at two concentrations), SP alone and media (control). (n=10 mice)

FIGURE 10.

In vitro mRNA expression of an anti-apoptotic gene in macrophages. Samples compare stimulation with LPS ± Substance P (SP) (at two concentrations), SP alone and media (control). (n=10 mice)

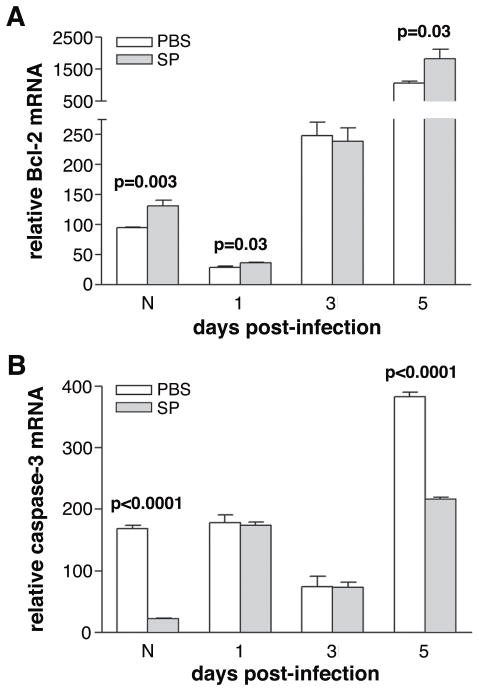

Real-time RT-PCR for Bcl-2 and caspase-3

Since SP also has been shown to delay apoptosis in vivo,26 resulting in a persistence of infiltrating neutrophils, apoptotic genes were measured in elicited BALB/c macrophages stimulated with LPS ± SP (10−9 M and 10−12 M). Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 (Fig. 10) was significantly increased after stimulation with LPS plus either concentration of SP (p<0.0001 and p=0.02) compared to LPS treatment alone. Levels of pro-apoptotic caspase-3 were below the level of detectability in the macrophage samples (data not shown).

To substantiate the above in vitro data, corneal samples were used to probe for Bcl-2 and caspase-3. In the normal cornea and at 1 and 5 days after infection (Fig. 11A), there was a significant increase in Bcl-2 mRNA (p=0.003, p=0.03, p=0.03) with no difference at 3 days of infection after SP vs. PBS treatment. Caspase-3 was detectable in cornea (Fig. 11B) and was decreased in the normal uninfected SP- vs. PBS-treated group and after 5 days of infection. (p<0.0001 and p<0.0001). No significant change was seen at days 1 or 3 after infection.

Figure 11.

(A, B) mRNA expression of apoptotic associated genes in cornea. Samples are taken from normal cornea and at 1, 3 and 5 days post-infection. Samples compare mice injected with Substance P (SP) vs. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

DISCUSSION

SP regulates numerous aspects of immune function in that it can either potentiate damage or promote healing.21–26 Hong, et al.23 characterized SP as an “injury-inducible factor” that acts early in the repair process after wounding, enhancing fibroblast proliferation, with a similar function after burn injury.37 In contrast, SP has been shown to enhance keratitis in the P. aeruginosa-infected BALB/c mouse cornea resulting in rapid influx of neutrophils into the site of infection and delaying their apoptosis.16, 26 Despite these documented effects, that study did not determine whether systemic effects of intraperitoneal injection of SP played a role in these events.16 Therefore, in the current work, we similarly tested and established that injection of SP did not induce systemic effects and that significantly elevated levels of the neuropeptide were observed only in the infected cornea, and not the duodenum (a peripheral organ site tested). To confirm these results, we also tested levels of IL-1β in both sites and found elevated levels of the cytokine only in the infected cornea, with no differences seen in the duodenum. Together, these data provide evidence that there is no detectable systemic effect following intraperitoneal injection of SP in this model. Thus, current work was able to reasonably test the hypothesis that a contributing factor of enhanced disease in the cornea after SP injection results from a decrease in growth factor production.

Growth factors are instrumental in the evolution and resolution of inflammation. They are naturally-occurring and facilitate cell-to-cell communication in order to enhance cell proliferation and migration, essential to restoring tissue functionality after injury.30, 38–41 Regarding growth factors and regulation by SP, studies have demonstrated that SP has angiogenic properties, including increasing vascular endothelial growth factor-A production by epidermal granulocytes42 and inducing growth of vascular endothelial cells into the cornea.43 Topical administration of SP and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) to the cornea after non-infectious injury has been shown to synergistically facilitate epithelial migration during wound closure.44 To date, however, information regarding SP regulation of growth factors known to be important in non-infectious wound healing (including EGF, HGF, and FGF-7/KGF) is not available in the infected cornea.

For EGF, Lai et al.45 provided evidence that the spatiotemporal expression of elevated EGF paralleled increased SP immunoreactivity in skin, while damage to SP-positive neurons decreased EGF levels, worsening disease outcome. In contrast, the current study found that after SP injection, decreased protein levels for EGF occurred early (1 day after infection), despite elevated levels of mRNA at a similar time. Later in disease, no difference in either mRNA or protein levels of EGF was observed between groups. Since previous studies on EGF have linked elevated levels of the growth factor with proliferation, migration, and differentiation of epithelial cells,30 it appears difficult to conclude that the early (but not later in disease) decrease in EGF protein levels contributes directly to increased disease severity, despite our prediction.

Another growth factor, HGF, is a potent factor in epithelial cell and keratinocyte proliferation and motility in the cornea41, 46, 47 and other tissues.48 In this regard, primary corneal epithelial cells were treated in vitro with exogenous HGF that induced marked cellular proliferation.49 In another in vitro study, HGF treatment enhanced the migration, growth, and DNA synthesis of human keratinocytes.50 The current study unexpectedly found that after injection of SP, HGF mRNA and protein levels are elevated up to 7 days after infection. Immunostaining and cell counts supported these data showing increased epithelial and stromal HGF labeling after SP treatment with an increase in the percentage of HGF-positive fibroblasts and macrophages. SP also increased expression of FGF-7/KGF in the infected cornea in a similar pattern to HGF, increasing expression of the growth factor at both the mRNA and protein level. FGF-7 is an epithelial cell-specific mitogen that is secreted by stromal fibroblasts.51 Stimulation of human keratinocytes with FGF-7 in vitro strongly enhances their proliferation and differentation.52 Furthermore, topical application of FGF-7 to central corneal epithelial wounds accelerates healing with all wounds healed in the FGF-7-treated group by 72 hours post-injury.53 However, in the SP-treated infected BALB/c cornea, despite elevated levels of the growth factors, repair of corneal tissues does not occur. In order to explore this further, we examined putative cell types and mechanisms that might contribute to this outcome.

Both fibroblasts and macrophages are sources of growth factors in the cornea and SP has been shown by others to increase their proliferation.39, 40, 54, 55 Using dual-immunostaining for either fibroblasts or macrophages, together with staining for each of the growth factors, followed by cell counts, the percent of EGF positive cells was no different for either cell type between SP vs. control groups. In contrast, SP treatment significantly increased the percentage of HGF and FGF-7 positive cells, consistent with elevated levels of these growth factors at both the mRNA and protein level. Moreover, we hypothesized that this increase in cell number may be due to proliferation39, 41 or the persistence of these cells in the cornea, perhaps due to decreased apoptosis,26, 37 as shown before for neutrophils. To test this in vitro, elicited macrophages were stimulated with LPS with or without SP. Following LPS and SP treatment, the anti-apoptotic gene, Bcl-2 mRNA levels were increased, while mRNA levels of the pro-apoptotic gene, caspase-3, were below the level of detectability. To confirm these in vitro data, we also tested whole cornea for these genes and confirmed that mRNA levels of Bcl-2 were increased and that caspase-3 was detectable and as anticipated, was decreased. Past studies have demonstrated similar findings regarding apoptotic genes in trauma models of injury (burn).37 In fact, blocking SP binding to its major receptor, neurokinin-1, improved disease by increasing the pro-apoptotic gene caspase-3, while the anti-apoptotic gene, Bcl-2, was decreased in the infected cornea of (susceptible) C57BL/6 mice30 who exhibit high levels of SP in cornea.27 Also, blocking SP interaction with its receptor has been shown to induce apoptosis in a human laryngeal carcinoma cell line.56 Taken together, these data support the anti-apoptotic properties of SP that can contribute to stromal tissue damage, which may provide a source of nutrients for bacterial growth, and worsened disease outcome after P. aeruginosa infection.57

Another contributory effect leading to increased pathogenesis after SP treatment was also explored in vitro in elicited LPS-stimulated macrophages. Neurokinin-1 receptors for SP are present on these cells and during periods of stress, SP binds to this receptor with high affinity58 releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α), as well as increasing cellular phagocytic and chemotactic capacity.25, 37 Thus, cytokine mRNA levels were measured in vitro after SP treatment (with or without LPS) in BALB/c elicited macrophages. SP plus LPS increased production of pro-inflammatory (e.g., IL-1β), while decreasing anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TGF-β). These data led us to hypothesize and test whether SP up-regulated M1 (NOS2 positive) and down-regulated M2 (arginase positive) types of macrophages, contributing to worsened disease. However, immunostaining and cell counts provided evidence that only M2 type cells were reduced, with no shift in the M1 population between treatment groups.

In summary, herein, we provide insight into the dual role of SP in this model of bacterial infection. Evidence has been provided to show the effects of SP on growth factors and stromal cells (e.g., macrophages and fibroblasts) in the infected cornea. The neuropeptide up-regulated growth factors (HGF and FGF-7), but this was accompanied by up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and anti-apoptotic genes along with down-regulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines and pro-apoptotic genes. Furthermore, the neuropeptide decreased the number of M2 types of macrophages, associated with tissue repair, with no effect on M1 type cells, associated with tissue destruction, all of which contribute to worsened disease, despite elevated levels of the growth factors. Thus, the data contraindicate the use of SP in an infected cornea, despite its clinical efficacy and ability to promote corneal wound healing in the absence of infection.59

Acknowledgments

Support: Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01EY02986 and P30EY04068.

References

- 1.Pachigolla G, Blomquist P, Cavanagh HD. Microbial keratitis pathogens and antibiotic susceptibilities: a 5-year review of cases at an urban county hospital in north Texas. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33:45–9. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000234002.88643.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilhelmus KR. Bacterial keratitis. In: Pepose JS, Holland GN, Wilhelmus KR, editors. Ocular Infection and Immunity. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995. pp. 970–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. Establishment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: lessons from a versatile opportunist. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1051–60. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazlett LD, McClellan SA, Kwon B, et al. Increased severity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa corneal infection in strains of mice designated as Th1 versus Th2 responsive. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:805–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClellan SA, Huang X, Barrett RP, et al. Macrophages restrict Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth, regulate polymorphonuclear neutrophil influx, and balance pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in BALB/c mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:5219–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kernacki KA, Barrett RP, Hobden JA, et al. Macrophage inflammatory protein-2 is a mediator of polymorphonuclear neutrophil influx in ocular bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:1037–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon B, Hazlett LD. Association of CD4+ T cell-dependent keratitis with genetic susceptibility to Pseudomonas aeruginosa ocular infection. J Immunol. 1997;159:6283–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lighvani S, Huang X, Trivedi P, et al. Substance P regulates natural killer cell interferon-gamma production and resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1567–75. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benoit M, Desnues B, Mege JL. Macrophage polarization in bacterial infections. J Immunol. 2008;181:3733–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, et al. M-1/M-2 macrophages and Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol. 2000;164:6166–73. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joshi AD, Raymond T, Coelho AL, et al. A systemic granulomatous response to Schistosoma mansoni eggs alters responsiveness of bone-marrow-derived macrophages to Toll-like receptor agonists. J Leuk Biol. 2008;83:314–24. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1007689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, et al. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–55. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazlett LD, McClellan SA, Barrett RP, et al. IL-33 shifts macrophage polarization, promoting resistance against Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1524–32. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Berger A, Milne CD, et al. Tachykinins in the immune system. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:1011–20. doi: 10.2174/138945006778019363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luger TA, Lotti T. Neuropeptides: role in inflammatory skin diseases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;10:207–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClellan SA, Zhang Y, Barrett RP, et al. Substance P promotes susceptibility to Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis in resistant mice: anti-inflammatory mediators down-regulated. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:1502–11. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szliter EA, Lighvani S, Barrett RP, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide balances pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected cornea and protects against corneal perforation. J Immunol. 2007;178:1105–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucey DR, Novak JM, Polonis VR, et al. Characterization of Substance P binding to human monocytes/macrophages. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1994;1:330–5. doi: 10.1128/cdli.1.3.330-335.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Payan DG. Neuropeptides and inflammation: The role of substance P. Annu Rev Med. 1989;40:341–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.40.020189.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chauhan VS, Kluttz JM, Bost KL, et al. Prophylactic and therapeutic targeting of the neurokinin-1 receptor limits neuroinflammation in a murine model of pneumococcal meningitis. J Immunol. 2011;186:7255–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahbaie P, Shi X, Guo T, et al. Role of substance P signaling in enhanced nociceptive sensitization and local cytokine production after incision. Pain. 2009;145:341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun J, Ramnath RD, Zhi L, et al. Substance P enhances NF-κB transactivation and chemokine response in murine macrophages via ERK 1/2 and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:1586–96. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00129.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong HS, Lee J, Lee EA, et al. A new role of substance P as an injury-inducible messenger for mobilization of CD29+ stromal-like cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:425–35. doi: 10.1038/nm.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delgado AV, McManus AT, Chambers JP. Exogenous administration of substance P enhances wound healing in a novel skin-injury model. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:271–80. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muangman MD, Tamura RN, Muffley LA, et al. Substance P enhances wound closure in nitric oxide synthase knockout mice. J Surg Res. 2009;153:201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Z, Barrett RP, McClellan SA, et al. Substance P delays apoptosis, enhancing keratitis after Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:4458–67. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hazlett LD, McClellan SA, Barrett RP, et al. Spantide I decreases type I cytokines, enhances IL-10, and reduces corneal perforation in susceptible mice after Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:797–807. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carrington LE, Boulton M. Hepatocyte growth factor and keratinocyte growth factor regulation of epithelial and stromal corneal wound healing. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:412–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Repertinger SK, Campagnaro E, Fuhrman J, et al. EGFR enhances early healing after cutaneous incisional wounding. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:982–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson SE, Chen L, Mohan RR, et al. Expression of HGF, KGF, EGF and receptor messenger RNAs following corneal epithelial wounding. Exp Eye Res. 1999;68:377–97. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang XY, McClellan SA, Barrett RP, et al. VIP and growth factors in the infected cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:6154–61. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hazlett LD, Moon MM, Strejc M, et al. Evidence for N-acetyl-mannosamine as an ocular receptor for P. aeruginosa adherence to scarified cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28:1978–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedchenko VK, Imagawa W. Estrogen treatment in vivo increases keratinocyte growth factor expression in the mammary gland. J Endocrinol. 2000;165:39–49. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1650039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sensoo T, Joyce N. Cell cycle kinetics in corneal endothelium from old and young donors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fortier AH. Isolation of murine macrophages. In: Coligan JE, Bierer BE, Margulies DH, et al., editors. Current Protocols in Immunology. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1994. pp. 14.11.11–14.11.16. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowden JJ, Garland AM, Baluk P, et al. Direct observation of substance P-induced internalization of neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptors at sites of inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8964–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jing C, Wang JH, Hong-Xing Z. Double-edged effects of neuropeptide Substance P on repair of cutaneous trauma. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;18:319–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2010.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson SE, Mohan RR, Mohan RR, et al. The corneal wound healing response: Cytokine-mediated interaction of the epithelium, stroma, and inflammatory cells. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:625–37. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klenkler B, Sheardown H. Growth factors in the anterior segment: role in tissue maintenance, wound healing and ocular pathology. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:677–88. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards JP, Zhang X, Mosser DM. The expression of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor by regulatory macrophages. J Immunol. 2009;182:1929–39. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Imanishi J, Kamiyama K, Iguchi I, et al. Growth factors: Importance in wound healing and maintenance of transparency of the cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2000;19:113–29. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(99)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohara H, Tajima S, Yamamoto M, et al. Angiogenesis induced by controlled release of neuropeptide substance P. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8617–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ziche M, Morbidelli L, Pacini M, et al. Substance P stimulates neovascularization in vivo and proliferation of cultured endothelial cells. Microvasc Res. 1990;40:264–78. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(90)90024-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakamura M, Ofuji K, Chikama T, et al. Combined effects of substance P and insulin-like growth factor-1 on corneal epithelial wound closure of rabbit in vivo. Curr Eye Res. 1997;16:275–8. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.16.3.275.15409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lai X, Wang Z, Wei L, et al. Effect of substance P released from peripheral nerve endings on endogenous expression of epidermal growth factor and its receptor in wound healing. Chin J Traumatol (English Edition) 2002;5:176–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson SE, He YG, Weng J, et al. Effect of epidermal growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor, and keratinocyte growth factor on proliferation, motility, and differentiation of human corneal epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 1994;59:665–78. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zelenka PS, Arpitha P. Coordinating cell proliferation and migration in the lens and cornea. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:113–24. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li-Juan B, Bing L, Zhi L, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor suppresses tumor cell apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by up-regulating Bcl-2 protein expression. Pathol Res Pract. 2009;205:828–37. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson SE, Walker JW, Chwang EL, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), their receptors, FGF receptor-2, and the cells of the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:2544–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsumoto K, Hashimoto K, Yoshikawa K. Marked stimulation of growth and motility of human keratinocytes by hepatocyte growth factor. Exp Cell Res. 1991;196:114–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90462-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sotozono C, Kinoshita S, Kita M, et al. Paracrine role of keratinocyte growth factor in rabbit cornea epithelial cell growth. Exp Eye Res. 1994;59:385–91. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marchese C, Rubin J, Ron D, et al. Human keratinocyte growth factor activity on proliferation and differentiation of human keratinocytes: differentiation response distinguishes KGF from EGF family. J Cell Physiol. 1990;144:326–32. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041440219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sotozono C, Inatomi T, Nakamura M, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor accelerates corneal epithelial wound healing in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:1524–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huo Y, Qui WY, Pan Q, et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are essential mediators in epidermal growth factor (EGF)-stimulated corneal epithelial cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, and wound healing. Exp Eye Res. 2009;89:876–86. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guilbert L, Robertson SA, Wegmann TG. The trophoblast as an integral component of a macrophage-cytokine network. Immunol Cell Biol. 1993;71:49–57. doi: 10.1038/icb.1993.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muñoz M, Rosso M, Aguilar FJ, et al. NK-1 receptor antagonists induce apoptosis and counteracts substance P-related mitogenesis in human laryngeal cancer cell line HEp-2. Invest New Drugs. 2008;26:111–8. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9087-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou Z, Wu M, Barrett R, et al. Role of the Fas pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2537–47. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li DQ, Tseng SCG. Differential regulation of keratinocyte growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor by different cytokines in human corneal and limbal fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 1997;172:361–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199709)172:3<361::AID-JCP10>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamada N, Matsuda R, Morishige N, et al. Open clinical study of eye-drops containing tetrapeptides derived from substance P and insulin-like growth factor-1 for treatment of persistent corneal epithelial defects associated with neurotrophic keratopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:896–900. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.130013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]