Abstract

Aims: Prostaglandin endoperoxide H2 synthase (PGHS) is a well-known target for peroxynitrite-mediated nitration. In several experimental macrophage models, however, the relatively late onset of nitration failed to coincide with the early peak of endogenous peroxynitrite formation. In the present work, we aimed to identify an alternative, peroxynitrite-independent mechanism, responsible for the observed nitration and inactivation of PGHS-2 in an inflammatory cell model. Results: In primary rat alveolar macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), PGHS-2 activity was suppressed after 12 h, although the prostaglandin endoperoxide H2 synthase (PGHS-2) protein was still present. This coincided with a nitration of the enzyme. Coincubation with a nitric oxide synthase-2 (NOS-2) inhibitor preserved PGHS-2 nitration and at the same time restored thromboxane A2 (TxA2) synthesis in the cells. Formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was maximal at 4 h and then returned to baseline levels. Nitrite (NO2−) production occurred later than ROS generation. This rendered generation of peroxynitrite and the nitration of PGHS-2 unlikely. We found that the nitrating agent was formed from NO2−, independent from superoxide (•O2−). Purified PGHS-2 treated with NO2− was selectively nitrated on the active site Tyr371, as identified by mass spectrometry (MS). Exposure to peroxynitrite resulted in the nitration not only of Tyr371, but also of other tyrosines (Tyr). Innovation and Conclusion: The data presented here point to an autocatalytic nitration of PGHS-2 by NO2−, catalyzed by the enzyme's endogenous peroxidase activity and indicate a potential involvement of this mechanism in the termination of prostanoid formation under inflammatory conditions. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 17, 1393–1406.

Introduction

Alveolar macrophages contribute to the lung's response to injury or inflammatory events by releasing signaling molecules. These include not only the bronchoconstrictor thromboxane A2 (TxA2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), but also the broncho- and vasodilator nitric oxide (•NO), as well as superoxide (•O2−), that can combine with •NO in an almost diffusion-limited interaction (6.7×109 M−1 s−1) (1, 16) to the strong oxidant and cellular-signaling molecule peroxynitrite (10, 24, 27, 31, 45). There are indications that peroxynitrite plays a vital role in the cross-talk between the prostanoid and the •NO-pathway. Peroxynitrite was demonstrated to activate prostaglandin endoperoxide H2 synthase (PGHS or cyclooxygenase) by providing the so called peroxide tone that describes the enzyme's demand for peroxides for continuous reinitiation of the PGHS catalytic cycle. PGHS contains a cyclooxygenase and a heme-containing peroxidase active site that are functionally interconnected by a radical-based catalytic mechanism. For activation, the enzyme requires defined levels of peroxides that convert the peroxidase active site ferric porphyrin [Fe3+ PPIX] into an unstable radical cation intermediate [Fe4+=O PPIX·+]. An intramolecular reduction of this intermediate is achieved by an electron originating from a tyrosine (Tyr) residue of the cyclooxygenase active site, thereby functionally connecting both domains. The resulting tyrosyl radical allows the conversion of the substrate arachidonic acid (AA). The cyclooxygenase domain strictly depends on the peroxidase activity; however, the peroxidase can work independently of cyclooxygenase turnover (2, 20, 21, 23). Due to the 10-fold higher peroxide requirement of the constitutively expressed PGHS-1 (21 nM), compared with the inducible PGHS-2 (2 nM) (22), it was proposed that the peroxide tone could represent a cellular regulatory mechanism preventing uncontrolled prostanoid synthesis under normal conditions. This was shown not only in vitro with the isolated enzyme, but also in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated smooth muscle cells where the inducible PGHS-2 required peroxynitrite in the low nanomolar range for activation (35). On the other hand, in RAW 264.7 macrophages, stimulation by LPS caused inhibition of PGHS-2, which was found to correlate with a nitration of a Tyr residue of the enzyme (36). Since peroxynitrite at high concentrations is known to nitrate the active site Tyr in isolated PGHS-1 under experimental settings utilizing high concentrations, it was proposed that also in macrophages, peroxynitrite was the nitrating species (6, 7, 41). This, however, was at variance with the observation that in RAW 264.7 macrophages, the formation of peroxynitrite and the nitration of PGHS-2 showed a different time course (32, 33). These observations indicated a delayed induction of nitric oxide synthase-2 (NOS-2) that was accompanied by the formation of relatively high levels of nitrite (NO2−). Although NO2− is partially protonated at acidic pH and can form peroxynitrous acid in the presence of H2O2, it is incapable to directly nitrate biological structures at physiological pH (44).

Innovation.

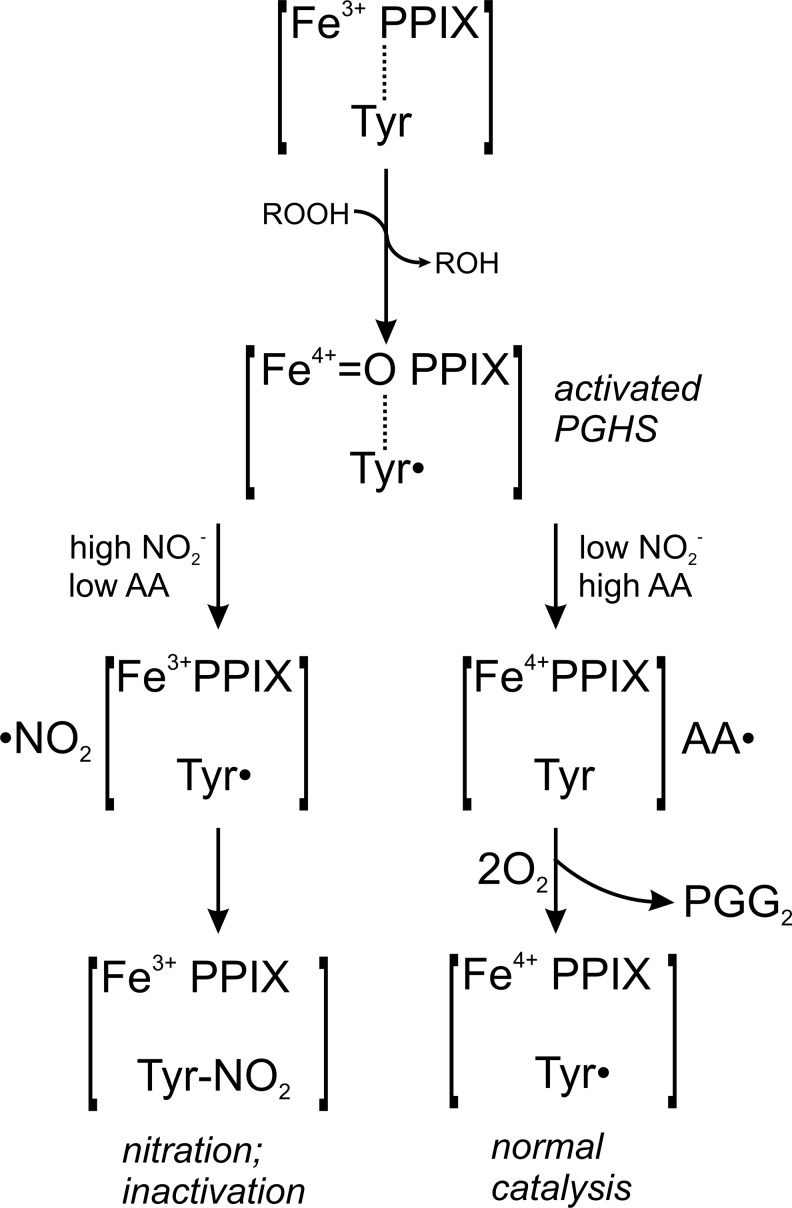

Peroxynitrite is currently assumed as the dominating nitrating species under inflammatory conditions. In activated alveolar macrophages, however, an early peak in endogenous superoxide (•O2−) formation, but a late onset of nitric oxide (•NO) formation was observed that limits a significant role of peroxynitrite in the observed nitration and inactivation of prostaglandin endoperoxide H2 synthase-2 (PGHS-2). As a novel mechanism, this study suggests a self-catalyzed nitration and inactivation of PGHS-2, assisted by the enzyme's peroxidase-mediated activation of nitrite (NO2−) into the highly reactive nitrogen dioxide radical (Fig. 8). The proposed mechanism of an autocatalytic NO2−-dependent inactivation of PGHS-2 could be involved in the resolution of acute inflammatory events.

Nevertheless, NO2− was recently suggested as an additional source for biological Tyr nitrations, as it was discovered that peroxidases such as myeloperoxidase, lactoperoxidase, or eosinophil peroxidase can catalyze a one-electron oxidation of NO2− to form the highly reactive •NO2 radical (43, 46). These peroxidases are typically expressed in white blood cells, whereas most other cell types usually do not explicitly express peroxidases. However, some enzymes, such as PGHS, contain an endogenous peroxidase activity. The potential relevance of a peroxidatic activation of NO2− in the lung becomes apparent, when plasma NO2− levels, typically in the range of 0.5–3 μM, are compared with NO2− levels in the respiratory tract-lining fluid that can easily exceed 15 μM in man even under normal conditions (12, 26). Previous publications provided first indications that the oxidation of NO2− by the intrinsic peroxidase activity of PGHS might had been involved in the observed inactivation of PGHS-2 (30, 36). In this earlier work, the position of the nitrated Tyr could not be established, and also a physiological or a pathophysiological significance was not apparent.

In the present investigation, we identified nitration of the active site Tyr371 by NO2−/peroxides in isolated PGHS-2. The biological relevance of this mechanism was underlined by the observation of a timely lack of overlap in the formation of •NO and •O2− in activated alveolar macrophages that limits the involvement of significant peroxynitrite formation. This concept was further verified in a noninflammatory NOS-2-inducible HEK 293T cell model, in which nitration and inactivation of PGHS-2 were observed irrespectively of the expression of superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD-1), excluding the contribution of peroxynitrite.

Results

PGHS-2 nitration in a lung inflammation model

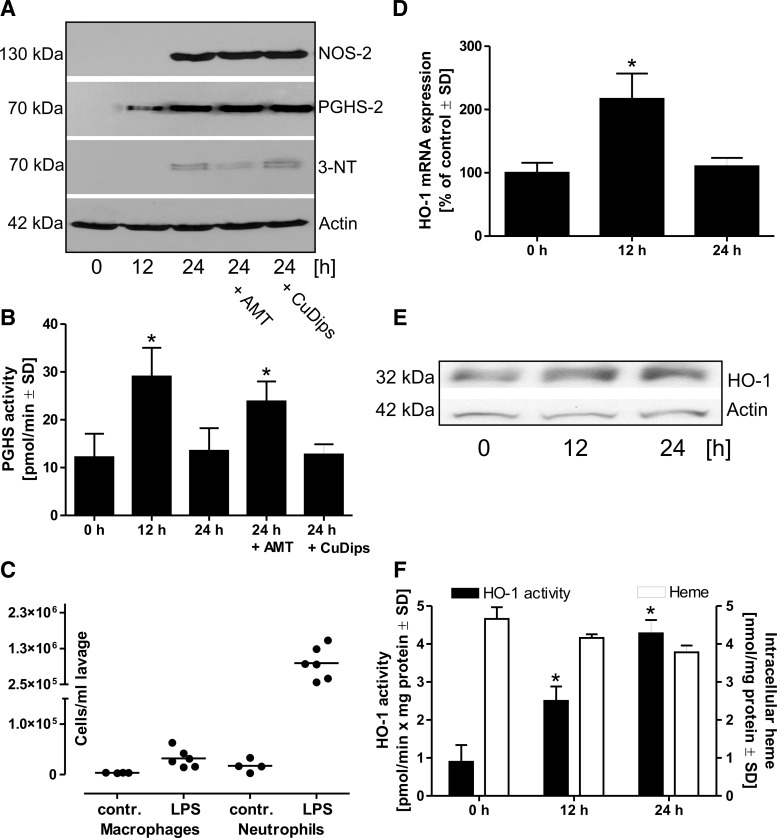

Male Wistar rats were treated with LPS (200 μg in 200 μl phosphate buffered-saline [PBS] per animal) by intranasal instillation. The rats were then kept for 12 or 24 h; separate 24-h groups additionally received the NOS-2 inhibitor 5,6-dihydro-6-methyl-4H-1,3-thiazin-2-amine (AMT) (1 mM in 200-μl volume) or the SOD-mimetic Cu(II)2(3,5-diisopropylsalicylate) (CuDips, 1 mM in 200-μl volume). After the treatment period, a bronchoalveolar lavage was performed to recover alveolar macrophages. These cells were further purified and used for a protein analysis. PGHS-2 protein expression was not detectable in cells from control animals, but was upregulated after 12 h of LPS treatment, and further increased at 24 h. NOS-2 protein expression was only detectable after 24 h. Immunoprecipitation of PGHS-2 from the isolated cells and subsequent staining of the respective protein band on a Western blot by an antibody specific for 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) indicated a nitration of PGHS-2 that was reduced by the NOS-2 inhibitor AMT, but not by the SOD-mimetic CuDips (Fig. 1A). Detection of total PGHS activity indicated an increase after 12 h of LPS treatment and a subsequent decline at 24 h. The drop in the activity was prevented by the presence of AMT, whereas CuDips had no effect (Fig. 1B). Analysis of the cell types and cell numbers in bronchoalveolar lavages from control rats or from animals treated with LPS showed a significant infiltration of neutrophil granulocytes in LPS-challenged lungs, while the total number of macrophages increased only slightly (Fig. 1C). Heme is an essential cofactor of PGHS. To rule out that changes in heme levels contribute to the observed LPS effect on PGHS activity, mRNA and protein expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), an enzyme that catalyzes the degradation of heme, as well as HO activity and intracellular levels of heme were analyzed (Fig. 1D–F). Even though the HO activity increased fourfold, total levels of heme did not change significantly over time.

FIG. 1.

Nitration of PGHS-2 and its inhibition in an in vivo lung inflammation model. (A) Rats were treated with LPS (200 μg in 200 μl PBS, intranasally) for 12, 24, or for 24 together with the NOS-2 inhibitor AMT (1 mM in 200 μl) or the SOD-mimetic CuDips (1 mM in 200 μl). Following lavage from isolated lungs, alveolar macrophages were separated from other cell types and protein expression was analyzed by Western blots, stained for PGHS-2 or NOS-2. Additionally, PGHS-2 was separated from the crude protein extracts by immunoprecipitation and then analyzed by Western blot using and antibody against 3-NT. (B) The PGHS activity was detected in cell lysates of the LPS-challenged, freshly isolated, macrophages after addition of the substrate AA (14C-AA) for 20 min. (C) Cell number of macrophages and neutrophils in crude lavages of control and LPS-challenged rats were detected by the differential cell count (•=one animal). For the detection of HO-1 mRNA (D) and protein levels (E), as well as for the analysis of total HO activity and intracellular levels of heme (F), rats were challenged for 0, 12, or 24 with LPS. Values represent means±SD of three independent isolations. *p<0.05 versus t=0. 3-NT, 3-nitrotyrosine; AA, arachidonic acid; AMT, 5,6-dihydro-6-methyl-4H-1,3-thiazin-2-amine; CuDips, Cu(II)2(3,5-diisopropylsalicylate); HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NOS-2, nitric oxide synthase-2; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PGHS-2, prostaglandin endoperoxide H2 synthase-2; SD, standard deviation; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

PGHS-2 and NOS-2 expression patterns

Due to the relatively high variability and the observed infiltration of neutrophils, all further experiments were performed with isolated alveolar macrophages that were stimulated with LPS ex vivo.

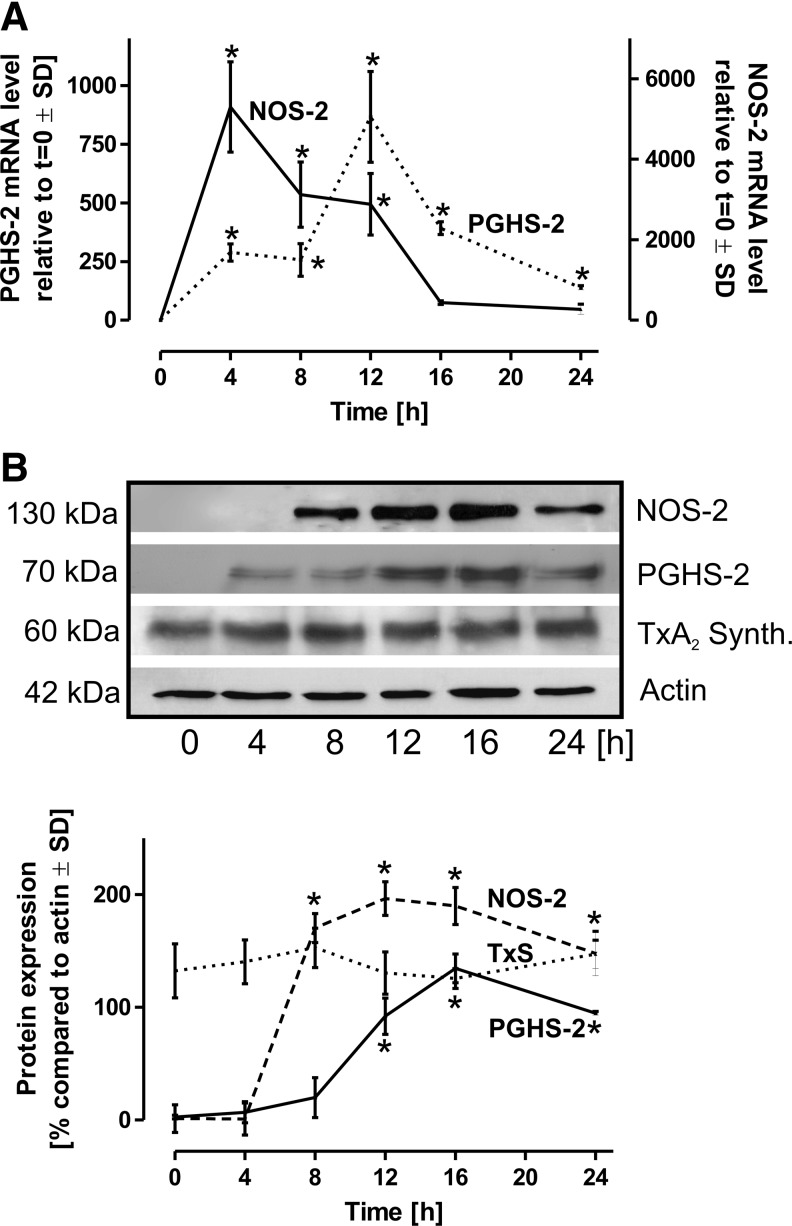

To obtain quiescenced cells, freshly lavaged alveolar macrophages were allowed to rest for at least 24 h. Both the induction of PGHS-2 as well as that of NOS-2 were observed directly after isolation. After the resting phase of 24 h, corresponding mRNA and protein levels dropped under the detection limit. The relatively high concentration of LPS added (10 μg/ml) was chosen for maximal cell stimulation. Under such conditions, PGHS-2 mRNA and protein expression demonstrated a gradual increase with a peak after 12–16 h of LPS incubation (Fig. 2A, B). After 24 h, PGHS-2 mRNA expression almost returned to resting levels. TxA2 synthase protein expression was not affected by the stimulation (Fig. 2B). The activities of terminal prostanoid synthases in the LPS rat alveolar model were tested by the addition of 14C-15-hydroxy prostaglandin-9, 11,-endoperoxide (14C-PGH2) to cell homogenates. The resulting pattern of prostanoids exhibited no significant alteration during the time course of LPS stimulation, thus allowing the conclusion that terminal synthases are not significantly affected by an inflammatory activation of rat alveolar macrophages (not shown).

FIG. 2.

Induction of PGHS-2 and NOS-2. Following isolation of primary rat alveolar macrophages, the cells were allowed to rest for 24 h to avoid baseline induction of PGHS-2 and NOS-2 that were under detection limit on the mRNA and protein level following this regiment. The cells were then stimulated with LPS (10 μg/ml) for the time periods as indicated. (A) For the mRNA expression analysis, GAPDH served as control, values at t=0 were defined as 1. (B) Protein expression of PGHS-2, NOS-2, and TxA2 synthase was quantitatively assessed, actin served as the loading control. Data represent mean values±SD of at least three independent experiments. *p<0.05 versus t=0. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; TxA2, thromboxane A2.

NOS-2 mRNA expression was maximal after 4 h of LPS incubation followed by an exponential decline (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, NOS-2 protein expression was significantly delayed compared to the appearance of mRNA transcripts and reached a plateau between 12 and 16 h (Fig. 2B).

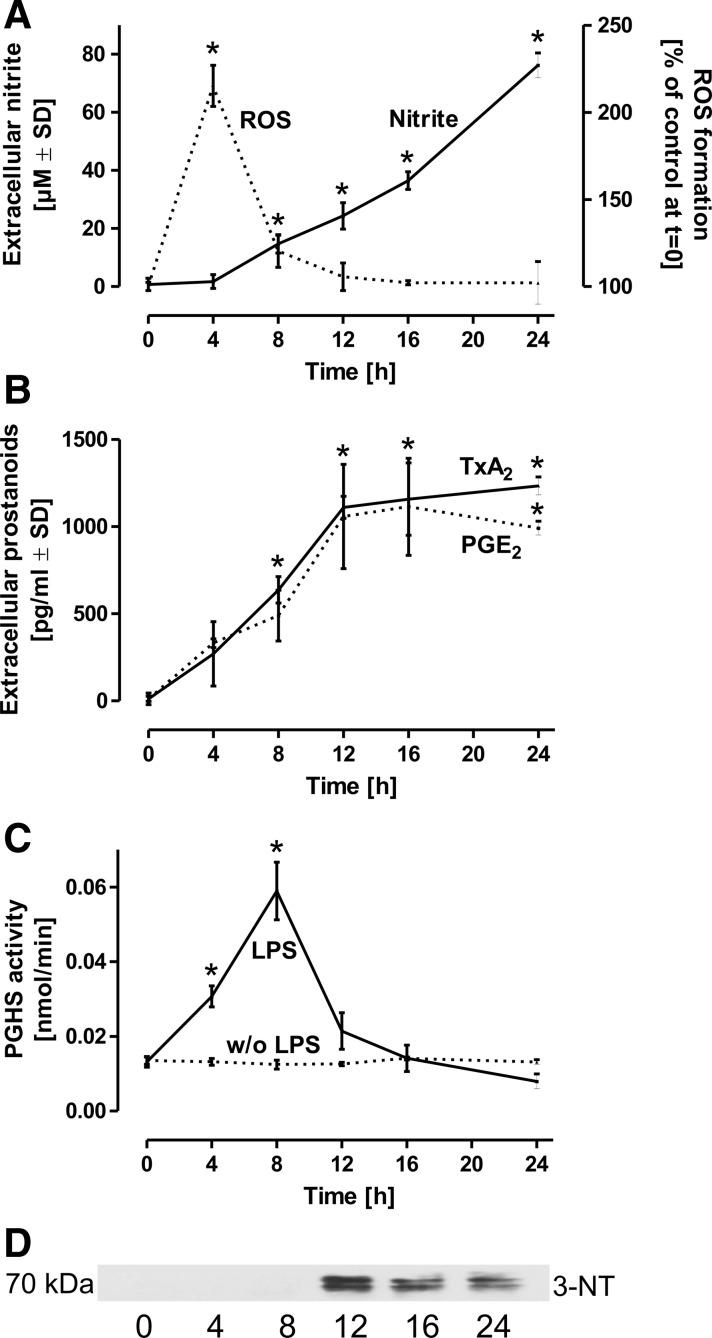

Decline in PGHS-2 activity correlates with NO2− accumulation and nitration

Peroxynitrite, originating from the interaction of •NO and •O2−, is generally considered as a key candidate for biological Tyr nitrations. We therefore assayed formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in LPS-challenged macrophages by the cell permeable fluorescence probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2-DCFDA) that indicates the formation of •O2− and its derivatives such as •OH, H2O2 and peroxynitrite. In contrast to the gradual increase in •NO generation, detected as its stable oxidation product NO2−, ROS formation demonstrated an early peak at 4 h that rapidly returned to almost baseline values (Fig. 3A). These observations indicate a significant time lag between the respective maximal formation rates of •O2- and •NO, thus limiting the likelihood for the generation of peroxynitrite, that is maximal at an •NO:•O2− ratio of 1:1.

FIG. 3.

PGHS activity in LPS-challenged macrophages. Quiescenced rat alveolar macrophages were stimulated by LPS (10 μg/ml) for the time intervals indicated. (A) Formation of ROS was assessed by H2-DCFDA (1 μM), added for a period of 30 min to cells pretreated with LPS for the time intervals as indicated. NO2−, as stable oxidation product of •NO was detected in parallel in the supernatants. (B) TxA2 and PGE2 were analyzed in the same time course as representatives of prostanoids released by activated alveolar macrophages. The values detected represent accumulated TxA2 or PGE2 levels at the respective time points. (C) To avoid an impact of substrate availability or modulation in the activities of terminal synthases, the PGHS activity was directly assessed in LPS (10 μg/ml)-primed macrophages by cell lysis and addition of 14C-labeled substrate AA for 10 min to the homogenates. Products were separated by thin layer chromatography and background values were obtained by parallel samples pretreated with the PGHS-2 selective inhibitor DuP-697 and the PGHS-1 selective inhibitor SC-560. The sum of all DuP-697 and SC-560-inhibitable prostanoids was integrated and served as measure for the PGHS activity. (D) PGHS-2 was immunoprecipitated from the respective cell homogenates, subjected to the Western blot analysis and stained for 3-NT. *p<0.05 versus t=0. H2-DCFDA, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; •NO, nitric oxide; NO2−, nitrite; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

To discover the relative contribution of the two PGHS isoforms to the experimentally measured total PGHS activity, cells were stimulated for 8 h with LPS for PGHS-2 induction, homogenized, and treated with the PGHS-2 selective inhibitor DuP-697, with the PGHS-1 selective inhibitor SC-560, or with the isoform-unselective inhibitor aspirin for 20 min. PGHS-2 almost exclusively contributed to the detected total PGHS activity, whereas PGHS-1 was involved only to a minor extent (not shown).

The PGHS activity was then measured indirectly by the detection of TxB2 (the stable hydration product of TxA2) or PGE2 as relevant representatives of prostanoids formed by activated alveolar macrophages. In accordance with the observed increase in PGHS-2 mRNA and protein expression, the two prostanoids increased between 0 and 12 h of LPS exposure, however, formation ceased after 12 h (Fig. 3B).

To circumvent a possible involvement of changes in phospholipase A2 (PLA2) activity, which liberates the PGHS substrate AA from cellular membranes, the total PGHS activity was directly assessed in freshly prepared cell lysates by the detection of PGHS-dependent metabolites following the conversion of 14C-AA. The PGHS activity in LPS-stimulated macrophages peaked at 8 h, followed by a rapid decline (Fig. 3C). This observation parallels the termination of TxA2 and PGE2 synthesis as observed in Figure 3B, but is strikingly inconsistent with the maximum in PGHS-2 protein expression after 16 h (Fig. 2A, B). According to previous observations by us and others (6, 7, 36), the observed decline in the PGHS activity may have been caused by nitration and inhibition of the enzyme. Immunoprecipitation of PGHS-2 followed by the Western blot analysis and staining for 3-NT showed first indications of PGHS-2 nitration under the conditions employed (Fig. 3D).

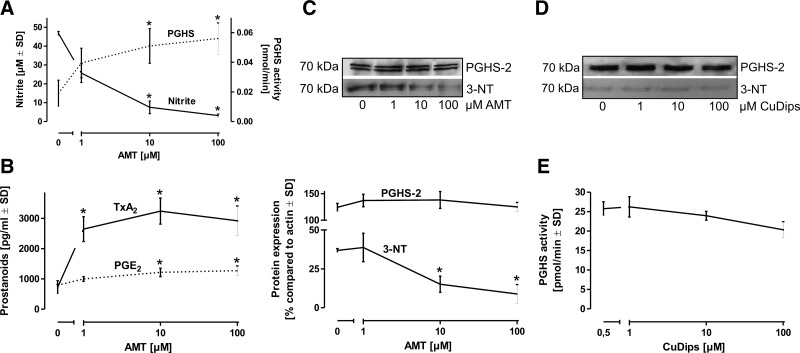

PGHS-2 inactivation depends on NO2− accumulation

The participation of NOS-2-derived •NO-dependent species in the nitration process was further investigated by using the NOS-2 selective inhibitor AMT. To avoid effects of AMT on NOS-2 or PGHS-2 protein expression (15), alveolar macrophages were pretreated with LPS for 8 h for PGHS-2 and NOS-2 induction, washed, and then incubated in a fresh medium for additional 8 h with LPS and AMT. Inhibition of endogenous •NO synthesis by AMT protected PGHS-2 from nitration and inactivation (Fig. 4A), which was paralleled by a preservation of TxA2 and PGE2 formation (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the effect was significantly less pronounced for PGE2 compared with TxA2. Immunoprecipitation of PGHS-2 from cell homogenates and staining with an anti-3-NT antibody indicated that nitration of PGHS-2 is concentration-dependently prevented by NOS inhibition (Fig. 4C). The same set of experiments as in Figure 4 was performed with the NOS-inhibitor L-NG-monomethyl arginine (L-NMMA) and qualitatively provided the same results (not shown). The same experimental setup as in Figure 4C was then applied to test the impact of the SOD mimetic CuDips instead of the NOS-2 inhibitor AMT. Dismutation of •O2− in the presence of an active NOS-2 displayed no impact on the nitration status and activity of PGHS-2 (Fig. 4D, E).

FIG. 4.

Impact of NOS-2 inhibition on PGHS activity. (A) Resting rat alveolar macrophages were incubated with LPS (10 μg/ml) for 8 h to allow PGHS-2 induction without interference by pharmacological compounds, new medium containing LPS and the NOS-2 selective inhibitor AMT was then added for additional 8 h. The concentration-dependent decline in NO2− levels by AMT inversely correlated with a rise in PGHS activity. (B) In parallel to the direct assessment of PGHS in cell homogenates, formation of TxA2 and PGE2 by intact cells was detected by an enzyme immunoassay. (C) For an evaluation of PGHS-2 nitration, the enzyme was immunoprecipitated from cell homogenates and then stained with an anti-3-NT antibody. (D) In the same experimental setup, the SOD-mimetic CuDips was used instead of AMT, immunoprecipitated PGHS-2 was subjected to the Western blot analysis and stained with an anti-3-NT antibody. (E) The PGHS activity was determined in CuDips-treated cells by lysis, addition of 14C-labeled substrate AA (14C-AA), and separation of labeled prostanoids by thin layer chromatography. Values represent means±SD of three independent macrophage isolations. *p<0.05 versus t=0.

Overexpression of SOD-1 has no significant impact on PGHS-2 nitration and inactivation

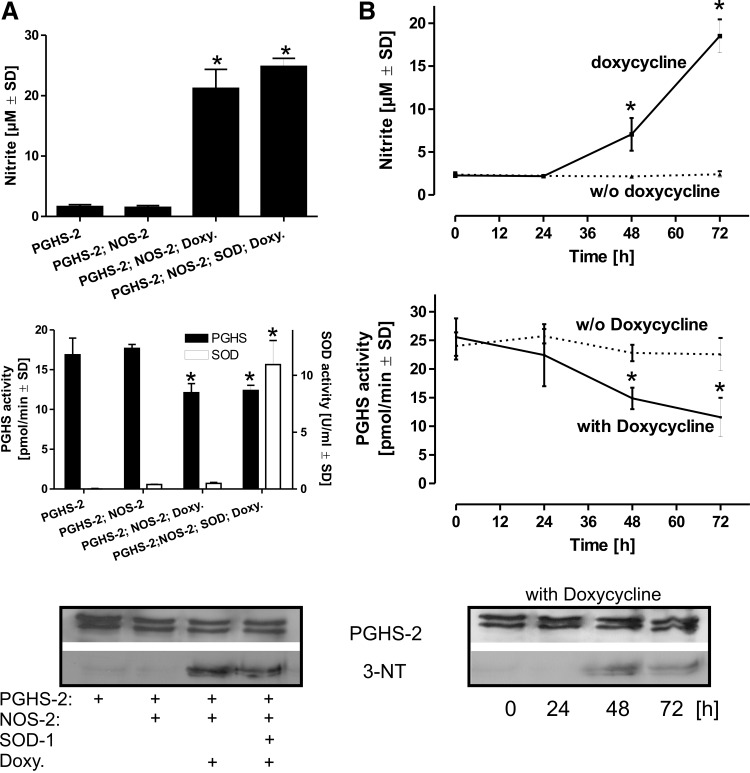

To obtain an alternative cellular system in which the generation of •O2− and hence the intracellular generation of peroxynitrite can be excluded, HEK 293T cells were transfected with plasmids coding for constitutively expressed human PGHS-2 and Cu/Zn-SOD as well as with a doxycycline-inducible NOS-2. Activation of NOS-2 by doxycycline for 48 h lead to an increase in NO2− accumulation that was paralleled by an increase in PGHS-2 nitration and a concomitant decline in the PGHS-2 activity. In the HEK 293T model, additional overexpression of Cu/Zn-SOD had no significant impact, thus excluding a significant role of endogenously formed •O2− and hence peroxynitrite in the observed inactivation of PGHS-2 (Fig. 5A). In PGHS-2–Cu/Zn-SOD–NOS-2-transfected cells, addition of doxycycline lead to a time-dependent accumulation of NO2− (which was completely prevented by the addition of NOS-2 selective inhibitors such as AMT or L-NMMA) that was accompanied by a concomitant decline in the cellular PGHS-2 activity (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Inactivation of PGHS-2 in a Cu/Zn-SOD overexpression model. To limit a potential involvement of peroxynitrite that originates from the interaction of •NO and •O2−, HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected to constitutively express PGHS-2 and Cu/Zn-SOD. The cells were additionally transfected with a construct coding for NOS-2 under the control of a doxycycline-dependent promoter. (A) HEK 293T cells were transfected with combinations of plasmids coding for PGHS-2, Cu/Zn-SOD, and NOS-2. Doxycycline (1 μg/ml) was added for 48 h and NO2−, as indicator for NOS-2 induction was detected in the supernatants. The respective cell pellets were homogenized, PGHS activity was detected by following the conversion of 14C-AA. The SOD activity was analyzed in parallel by the cytochrome c assay. PGHS-2 was then immunoprecipitated from the cell homogenate, subjected to SDS-gel electrophoresis, and probed with anti-PGHS-2 and anti-3-NT antibodies. (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected with plasmids coding for PGHS-2, Cu/Zn-SOD, and NOS-2. Doxycycline, required for the induction of NOS-2 was added for the time intervals as indicated and NO2− was detected in the supernatant as an indicator for the NOS-2 activity. The time-dependent accumulation of NO2− correlated with a decline in the PGHS activity and an increase in 3-NT staining of immunoprecipitated PGHS-2. Values are mean±SD (n=4). *p<0.05 versus AMT=0. •O2−, superoxide; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate.

Autocatalytic activation of NO2− and inhibition of PGHS-2

For defined conditions without interference by cellular components, purified and heme-reconstituted PGHS-2 was used for the following experiments. PGHS contains an intrinsic peroxidase activity and was incubated for 4 h with increasing concentrations of NO2− in the presence of various levels of unlabeled substrate AA. For the activation of the peroxidase domain and generation of the Tyr• radical, 0.1 μM of 12-hydroperoxy-5Z,8Z,10E,14Z-eicosaetraenoic acid (12-HpETE) was added.

A concentration-dependent decline of the PGHS-2 activity by NO2− was observed, which at the same time, exhibited competition with AA (Fig. 6A). Detectable nitration of purified PGHS-2 by the Western blot analysis became evident at a threshold of 10 μM NO2- in the presence of 0.1 μM AA and 0.1 μM 12-HpETE (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Nitration and inhibition of PGHS-2. (A) Purified PGHS-2 (10 U/reaction) was treated with 0.1 μM 12-HpETE for activation and variable concentrations of NO2− in the presence of different levels of unlabeled substrate AA for 30 min. Before 14C-AA was added for activity detection, levels of unlabeled AA were supplemented to add up to the maximal concentration of 10 μM AA in all samples. The activity of the enzyme was then assessed by the addition of 14C-AA for 3 min. (B) Samples preincubated with 0.1 μM unlabeled AA and increasing concentrations of NO2− were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Consecutive staining with anti-PGHS-2 and anti-3-NT antibodies demonstrated the appearance of a nitrated band with increasing concentrations of NO2− at the same molecular weight as PGHS-2. (C) Purified human PGHS-2 (10 U/reaction) in the presence of 0.1 μM 12-HpETE was incubated with variable concentrations of either NO2− or authentic peroxynitrite. Following an incubation period of 2 h, the activity was the assessed by the addition of 14C-AA. (D) For the detection of radical formation, PGHS-2 (10 U/reaction), together with 0.1 μM 12-HpETE was treated with increasing concentrations of NO2− in the presence of DHR 123 (1 μM). DHR 123 is a relatively selective dye for the detection of peroxynitrite, respectively, the •NO2 radical. Rhodamine fluorescence (λex 485 nm; λem 538 nm) was then detected after 2 h. In a second experiment, PGHS-2 was treated with 0.1 μM 12-HpETE, 100 μM NO2−, and 1 μM DHR 123 and varying concentrations of the peroxynitrite/•NO2 radical scavenger uric acid for 2 h. *p<0.05 versus conc.=0. 12-HpETE, 12-hydroperoxy-5Z,8Z,10E,14Z-eicosatetraenoic acid; DHR, dihydrorhodamine; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecylsulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

For direct comparison of the relative impact on PGHS inactivation, the enzyme was incubated for 4 h with 0.1 μM 12-HpETE to provide the peroxide tone for PGHS in the absence of substrate, together with either authentic peroxynitrite, or with the same concentration of NO2−. The experiment was conducted in the presence or absence of SOD (1 U/200-μl volume) to exclude a potential impact of •O2− that could originate from autoxidation or by enzymatic turnover. The PGHS activity was then detected by following the conversion of 14C-labeled substrate AA. In the absence of substrate during treatment, both peroxynitrite and NO2− lead to a concentration-dependent decline with a ca. 30% reduction in the PGHS activity by NO2− and an almost 100% reduction by peroxynitrite levels >100 μM (Fig. 6C). Dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR 123) is a relatively selective dye for the detection of peroxynitrite, respectively, the •NO2 radical; however, it has to be considered that also other radical species are measured. In the presence of peroxides and varying concentrations of NO2−, PGHS-2 leads to a NO2−-dependent increase in the oxidation of DHR 123, thus indirectly indicating the formation of ROS. To further highlight the potential formation of •NO2 radicals, the enzyme was incubated with fixed concentrations of peroxides and NO2− and increasing levels of the peroxynitrite/•NO2 selective scavenger uric acid that lead to a concentration-dependent decline in DHR 123 oxidation (Fig. 6D).

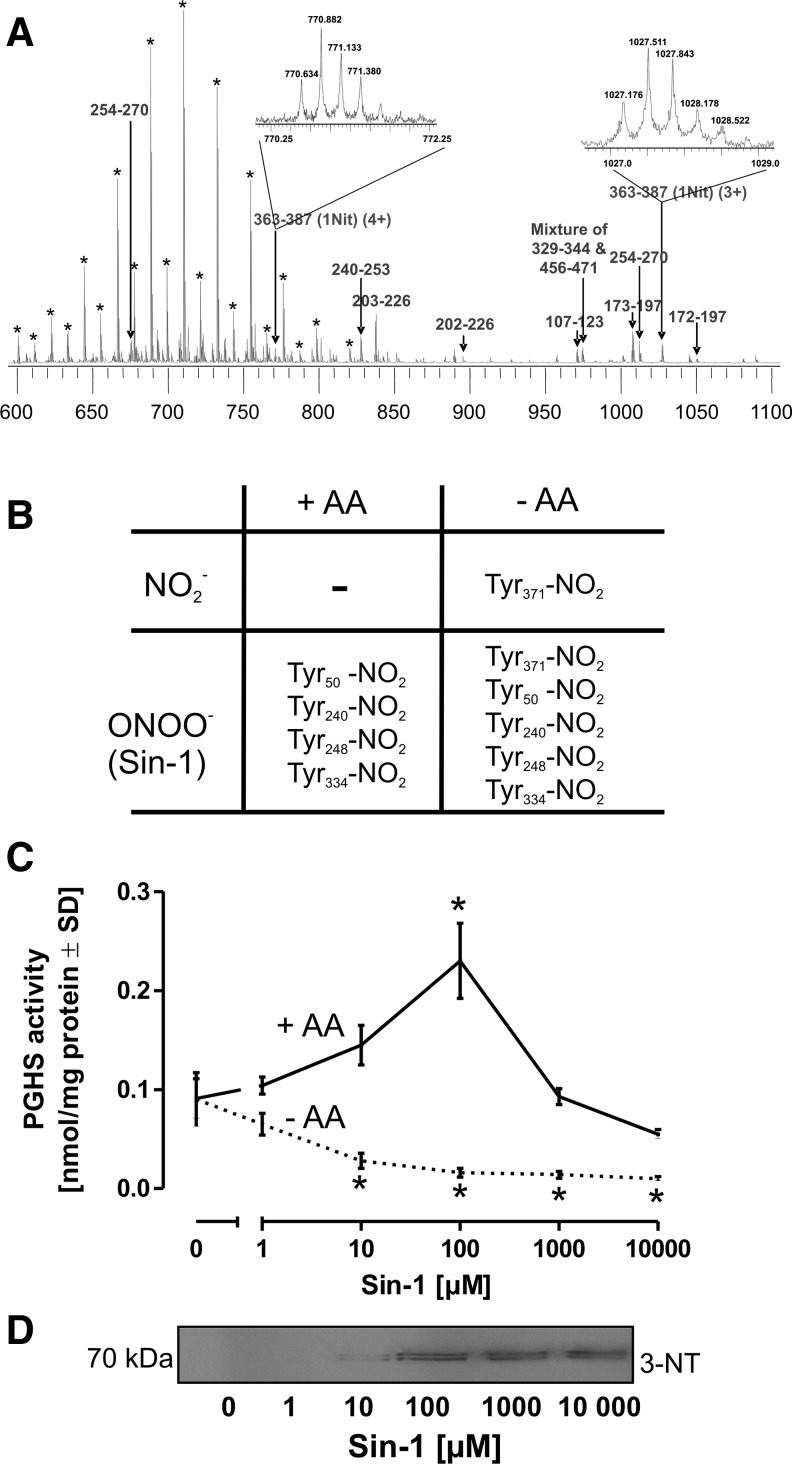

Nitration of the active site Tyr residue

The position of the nitrated Tyr residue was confirmed with purified human PGHS-2. The enzyme was incubated with 0.1 μM 12-HpETE in the presence of 50 μM NO2- for 30 min to obtain complete nitration. The nitrated enzyme was purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and all the fractions were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization – time of flight (MALDI-TOF) in the linear mode to identify the PGHS-2-containing fraction (Fig. 7A). Nitrated PGHS-2 was digested with sequencing grade trypsin and analyzed by Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. The spectrum in Figure 7A was internally calibrated by two polyethylene glycol (PEG) peaks at 644.3977 Da (H2C=CH-CH=CH-(CH2CH2O)28-H) and 776.4781 Da (H2C=CH-CH=CH-(CH2CH2O)34-H) and by a single peptide peak 240–253 (YQIIDGEMYPPTVK) at 827.4131 Da. All peptides observed in the tryptic digests of nitrated PGHS-2 were annotated, and peaks labeled by asterisk represent PEG contaminants. The two different charge states (+4 at 770.6337 Da and +3 at 1027.173 Da) of nitrated peptide 363–387 (IAAEFNTLYHWHPLLPDTFQIHDQK) were detected within 2-ppm mass accuracy. A single Tyr residue was found to be nitrated and identified as the cyclooxygenase active site Tyr371.

FIG. 7.

Detection of tyrosine nitration. (A) Human PGHS-2 (5 μg) was treated with 0.1 μM 12-HpETE and 50 μM NO2− for 1 h, trypsin digested, and analyzed by electrospray ionization-Fourier transform mass spectrometry. All the detected peptides were labeled. The inserts represent the charge-state distribution of the different charge states of nitrated peptides 363–387. (B) For a comparison of the impact of NO2− versus peroxynitrite, PGHS-2 (5 μg) and 0.1 μM 12-HpETE were incubated either with NO2− (50 μM) or with the peroxynitrite donor Sin-1 (100 μM) in the presence or absence of substrate AA. (C) For an illustration of the role of peroxynitrite as an activator and inhibitor of PGHS-2, the enzyme (10 U/reaction) was treated with varying concentrations of the peroxynitrite-donor Sin-1 in the presence or absence of substrate AA (5 μM) for 30 min, and then 14C-AA was added for 5 min for activity determination. (D) Sin-1-treated PGHS-2 was subjected to the Western blot analysis and stained with an anti-3-NT antibody. Tyr, tyrosine.

The table in Figure 7B provides an overview on the mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of PGHS-2 treated with NO2− or the peroxynitrite-donor Sin-1 (100 μM) in the presence or absence of substrate AA (10 μM). Sin-1 served as control, since it is known that peroxynitrite is capable of inactivating PGHS-2. In the presence of AA, both NO2- or Sin-1 failed to nitrate the active site Tyr371 residue. While Sin-1 also led to the nitration of other Tyr in PGHS-2, treatment with NO2− in the absence of AA only resulted in the nitration of Tyr371. To investigate the biological significance of Tyr371 nitration, PGHS-2 was treated with increasing concentrations of Sin-1. In the presence of substrate, Sin-1 led to a concentration-dependent increase in the PGHS-2 activity up to 100 μM of Sin-1, an effect described in the literature with the term “peroxide tone” (Fig. 7C), followed by a concentration-dependent decline with higher Sin-1 concentrations that was accompanied by a detectable nitration of the enzyme (Fig. 7D). In the absence of AA, nitration of Tyr371 was observed even with low Sin-1 concentrations (Fig. 7B) and correlated with a decline in the PGHS-2 activity (Fig. 7C).

Discussion

The present study was initiated by previous observations in which a nitration and inhibition of inducible PGHS-2 under inflammatory conditions had been reported (8, 36). We have chosen alveolar macrophages as a (patho)-physiologically relevant model, since Tyr-nitration is commonly observed in the lung of patients with acute pulmonary inflammation and alveolar macrophages represent one of the dominating sources of •NO under such conditions (25, 31). This scenario was recapitulated in an in vivo rat lung inflammation model, where we could observe nitration of PGHS-2. The NOS inhibitor AMT largely blocked Tyr-nitration and restored activity, but this still allows peroxynitrite or NO2− to be sources for the nitration process. However, the SOD-mimetic CuDips had no effect on the staining intensity and activity, which could be an indication for a •O2−- and hence peroxynitrite-independent mechanism. For further investigations on the nitration mechanism involved, we applied an ex vivo LPS stimulation protocol with primary rat alveolar macrophages (Fig. 1A, B). The key question of the present article was the identification of the dominating •NO-derived species responsible for the observed nitration of PGHS-2. In attempts of identifying the underlying mechanisms, the direct interaction of •NO with the active site tyrosyl radical or the nitration of PGHS-2 by peroxynitrite has been suggested (3, 18, 28, 38, 39).

Direct interaction of •NO with the Tyr• radical state of PGHS, however, was only observed at unphysiologically high fluxes of •NO in the millimolar range, since the coupling of both radicals has been identified as completely reversible (13, 14, 40). Hence, nitrotyrosine formation would require a consecutive oxidation step of the nitrosocyclohexadienone intermediate, which limits the physiological significance of this type of mechanism.

Due to the observed inadequate temporal overlap in •NO and •O2− formation in activated alveolar macrophages (Fig. 3A), generation of significant levels of peroxynitrite appears as rather unlikely, since peroxynitrite formation is maximal only at a 1:1 ratio between •NO and •O2− (4). Our finding that the NOS-2 inhibitor AMT, but not the SOD mimetic CuDips prevented nitration of PGHS-2 both in vivo (Fig. 1) and in vitro (Fig. 4) also indicated that a nitration mechanism distinct from that by peroxynitrite might be involved. Furthermore, in the HEK 293T model that constitutively expresses PGHS-2 (Fig. 5), doxycycline-induced expression of NOS-2 leads to the nitration and inactivation of PGHS-2, irrespectively of the presence or absence of overexpressed SOD-1 that decomposes •O2−, and hence prevents the formation of peroxynitrite. As an independent mechanism that could be involved in the observed decline in PGHS-2 activity, a reduction of intracellular heme levels was previously observed in some inflammation models. Since heme is an essential cofactor of the peroxidase active site of PGHS, we tested heme levels in LPS-challenged alveolar macrophages and observed a time-dependent moderate decline along with the induction of HO-1 that might contribute to the effects observed, but certainly does not play a dominant role in the nitration and inactivation of PGHS-2 (Fig. 1D–F).

The present results support the concept of an auto-nitration of PGHS-2 by NO2− by proving the selective nitration of Tyr371 at the active site. Peroxynitrite treatment of purified PGHS-2 in the absence of substrate not only resulted in the nitration of Tyr371, but also in the nitration of several other Tyr. However, at physiologically steady-state peroxynitrite fluxes in the low nanomolar range, and in the presence of substrate AA, no nitration of Tyr371, but even an activation of the enzyme (peroxide tone) was observed. In contrast, NO2− was found to cause a nitration already at levels present under inflammatory conditions and, similar to the situation with peroxynitrite, this occurred in competition with AA (5, 17, 36). Thus, a NO2−-dependent inactivation of PGHS-2 would become effective only after the downregulation of PLA2 activity that liberates AA from the cell membrane. For the cellular situation, this implies that under initial conditions of low NO2− and elevated AA availability, an autocatalytic inactivation of PGHS-2 appears rather unlikely. In contrast, in progressive stages of the inflammatory response, highly elevated NO2− levels and also a downregulation of liberated AA can be observed. The self-catalyzed nitration of PGHS-2 could therefore be involved in the events leading to the termination of the inflammatory process.

A simple mechanistic model on the self-catalyzed activation of NO2− and nitration of PGHS is so far difficult to postulate, since it has to be considered that two spatially separated activities are involved, the active site tyrosyl radical at the apex of the cyclooxygenase channel in the center of the enzyme, and the peroxidase catalytic site on the surface (34). Although it is not elucidated yet how this spatial barrier is actually resolved, the observation that 15-hydroperoxy prostaglandin-9,11,-endoperoxide (PGG2), formed in the cyclooxygenase channel, is reduced to PGH2 by the peroxidase activity, indicates the existence of efficient transport mechanisms linking both catalytic sites. Furthermore, additional channels in the cyclooxygenase domain were proposed (11) that may allow guidance of small radical species such as ·NO2 to the active site tyrosyl radical and hence facilitate PGHS nitration. The dimer interface region between the two monomers of both PGHS-1 and PGHS-2 is furthermore characterized by an enrichment of positive charges that could contribute to an accumulation of NO2− and thus support the self-catalyzed nitration with the substrate NO2− (11) (see Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Inhibition of PGHS by autocatalytic activation of NO2−. The prosthetic ferric heme [Fe3+ PPIX] of the peroxidase domain is oxidized by peroxides (ROOH) to an unstable radical cation intermediate [Fe4+=O PPIX•+] (9, 37, 42). It is assumed that an equilibrium between the ferryl porphyrin radical cation and the ferryl-tyrosyl state [Fe4+=O PPIX]+[Tyr•] exists. Interaction of NO2− with the radical cation formed at the peroxidase site would lead to the formation of a •NO2 radical and leaves the prosthetic heme in its ferryl form that would be oxidized by the presence of peroxides. In the presence of low levels of substrate AA (left), the newly generated •NO2 radical could then reach the tyrosyl radical at the cyclooxygenase active site either by diffusion via the main cyclooxygenase channel, or by one of the four alternative smaller channels connecting the active site with the exterior, leading to the nitration (Tyr-NO2) and inactivation of PGHS. In the presence of low NO2− concentrations, the tyrosyl radical would interact with AA to form AA• and ultimately 15-hydroperoxy prostaglandin-9,11,-endoperoxide (PGG2) (right), according to the proposed concept by Ruf and Kulmacz et al. (9, 20, 21, 37, 40, 42). Under these circumstances, PGG2 is reduced into PGH2 by the peroxidase site with electrons originating from the active site tyrosyl residue, leaving a Tyr• radical ready for the initiation of a new catalytic cycle. PPIX, protoporphyrin IX. PGG2, 15-hydroperoxy prostoglandin-9,11,-endoperoxide; PGH2, 15-hydroxy prostaglandin-9,11,-endoperoxide.

An interesting and yet unexplained observation concerns the weak impact of PGHS-2 nitration on PGE2 release (Fig. 4). PGE2 formation was inducible so that either a modified form of PGHS-2 was present in association with PGE2 synthase or the self-nitration by NO2− occurred in a different compartment or was hindered by formation of a PGHS-2/PGE2 synthase complex (29). In view of the multiple functions of PGE2 through its four receptors, a different signaling pathway may exist and reports in literature point to a separate organization of the PGE2-synthesizing activity. It could be speculated that PGE2 plays a role in the regeneration of an acute inflammatory activation in which ·NO continues to be formed and cAMP as well as cGMP may act on phosphorylation pathways or on the downregulation of the Ca2+-response.

In summary, our in vitro data show a release of TxA2 after LPS stimulation in a time window of 4–12 h after which an auto-nitration of PGHS-2 terminates the supply of PGH2 for the constitutive TxA2-synthase. This endogenous regulatory mechanism may be involved in the resolution of an acute inflammatory response in the lung.

Materials and Methods

Materials

LPS (Escherichia coli, serotype 026:B6), AMT, CuDips, DHR 123, and aspirin were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis), L-NMMA, Sin-1, authentic peroxynitrite, SC-560, and DuP 697 were purchased from Cayman Chemicals, 14C-AA was from Perkin Elmer.

Preparation of rat alveolar macrophages

Male Wistar rats (400–500 g) were sacrificed by inhalation of Isoflurane (Essex); lungs were excised and lavaged three times with a sterile ice-cold 0.9% NaCl solution (Braun). Cells were pooled, resuspended in the RPMI 1640 medium (Biochrom) containing 10% fetal calf serum and 100 U/ml Pen/Strep, and plated at a density of 5×106 cells/35-mm dish in 4-ml medium. After incubation for 4 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, the medium was changed and the cells were allowed to rest for at least 24 h. Animal handling was conducted by staff of the animal housing unit, the University of Konstanz, Germany, in accordance with the German Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

A few hours after lavage, the isolated alveolar macrophages contained already nitrated PGHS-2. For the purpose of stimulation by LPS, a 24 h resting period was required to obtain quiescent cells with basal levels of PGHS2 and NOS-2 under the detection limit. The stress during the isolation procedure was sufficient to activate the cells, which was supported by the absence of PGHS-2 and NOS-2 induction directly after isolation.

Airway macrophage inflammation model

Male Wistar rats were briefly anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane. LPS was instilled intranasally (200 μg in 200 μl PBS per rat). Control rats received 200 μl PBS. Animals were sacrificed after 12 or 24 h by inhalation of pure isoflurane and the lungs were quickly excised. Bronchoalveolar lavage was repeated two times with 20 ml ice-cold 0.9% NaCl solution. To recover alveolar macrophages, the total lavage was centrifuged at 2500 g for 10 min, cells were resuspended in RPMI-1640, seeded onto six-well dishes, and incubated for 30 min to allow selective recovery of macrophages. The medium was changed to remove nonadherent neutrophils.

The total cell number in crude lavages was counted with an Advia 120 hemocytometer (Siemens). Differential cell counts were performed on cytocentrifuged preparations stained with DiffQuik (Dache Behring).

All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with national and international laws and policies (EEC Council Directive 86/609, National German Animal Review Board; Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, U.S. National Research Council, 1996).

HO activity assay

The HO activity was determined according to the protocol of Klemz et al. (19). Briefly, cells (105 per data point) were lysed in 100 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and pH 7.4, including protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) for 30 min on ice and three pulses by a sonication needle. The reaction buffer consisted of 100 mM Tris, 15 μM hemin, 0.8 mM NADPH, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.8 mM glucose 6-phosphate, 300 μM bovine serum albumin, 1 U/100 μl glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and biliverdin reductase A (1 U/100 μl) (Sigma). Ten microliters of the cellular sample was mixed with 90 μl of the reaction buffer in a 96-well plate; fluorescence was detected in a fluorescence reader (Infinite M200; Tecan Instruments) at 37°C (λex 441 nm; λem 528 nm), and a biliverdin standard curve was routinely performed on the respective 96-well plate.

Intracellular heme was determined photometrically after three washing steps of freshly isolated alveolar macrophages (2×105 cells per data point) by using a commercially available detection kit (Bio Assay Systems).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was isolated by the guanidine isothiocyanate/phenol method, according to the manufacturer's instruction (Peqlab). For reverse transcription, murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random hexamer primers (Promega) were used. The reaction was performed at 42°C for 60 min. PCR amplification was carried out in a LightCycler™ Instrument using LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche Diagnostics) and the PGHS-2-specific sense primer, 5′-ATC TTT GGG GAG ACC ATG GTA GA-3′ and the antisense-primer, 5′-ACT GAA TTG AGG CAG TGT TGA TG-3′; for the NOS-2 sense-primer, 5′-AGT GTC AGT GGC TTC CAG CTC-3′ and the antisense primer, 5′-AGT GTC AGT GGC TTC CAG CTC-3′; for the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) sense primer, 5′-TCC ATG ACC GTT GTC AGC AAT GC-3′ and the antisense primer, 5′-GTG GTC ATT AGC CCT TCC ACG AT-3′. Settings were used as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 65°C for 5 s, and amplification at 72°C for 19 s. Fifty cycles were run before the reaction was stopped. Amplification was followed in real time, and its crossing-points were used for evaluation. After polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a melting curve analysis was conducted. Expression of HO-1 mRNA was analyzed with quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction using an iCycler™ iQ system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). TaqMan® Gene Expression assays (Applied Biosystems) for HO-1 and GAPDH were purchased as probe and primer sets, and gene expression was normalized to the endogenous control, GAPDH.

Western blot analysis

Proteins were separated electrophoretically by 6% or 8% sodiumdodecylsulfate–polyarylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond™-C extra) by semidry blotting. Ponceau S staining ensured equal protein loading and transfer. The membranes were blocked for 2 h with 5% milk powder and incubated with the primary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature or at 4°C overnight and for 45 min with a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature. Bands were visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescence technique (Interchim) and exposed to X-ray hyperfilm (Fuji). Anti-PGHS-2, anti-NOS-2, and anti-smooth muscle cell actin monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Transduction Laboratories. The anti-3-NT monoclonal antibody was from HBT and the anti-TxA2-synthase antibody was a kind gift from Prof. Tanabe, Osaka, Japan. For HO-1 detection, antibodies against actin (42 kDa) (1:2500, Sigma) and HO-1 (1:5000, monoclonal, Stressgen) were used.

PGHS activity

The PGHS activity was determined by the conversion of 14C-labeled AA (14C-AA). Cells were washed twice, collected in cold PBS, and centrifuged at 1000 g for 3 min. The pellet was dissolved in a lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, 1% Triton X-100, 1% aprotinin, and 10% glycerol, pH 7.5) for 30 min on ice. Following centrifugation at 12,000 g for 1 min, the supernatant was incubated with the reaction buffer (80 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 mM phenol, 5 μg/ml heme, and 5 μM 14C-AA, pH 8.0) for 20 min. Purified PGHS-2 was treated as indicated and incubated with 14C-AA for 2 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of ethyl acetate/2 M citric acid (30:1). After vortexing for at least 1 min, the organic phase was evaporated and spotted by glass capillaries onto silica thin layer chromatography plates (Silica 60, Merck) and subjected to chromatography. The solvent consisted of ethyl acetate:2,2,4-trimethylpentane:acetic acid:water (110:50:20:100). Plates were dried and exposed to a PhosphorImager™ screen overnight. For reading the screen, a PhosphorImager system from Molecular Dynamics was used. Quantification was performed by the detection of total prostanoid formation utilizing ImageQuant™ software. Purified PGHS-2 was a kind gift from Dr. R. Kulmacz, Houston, TX.

Measurements of prostanoids and NO2− in cell culture supernatants

TxB2, as the stable hydration product of TxA2, and PGE2 were determined by using commercially available enzyme immunoassay-kits (Assay Designs), according to the manufacturer's instructions. NO2−, as the stable autoxidation product of •NO formation, was measured by the Griess assay. Briefly, 30 μl 12.5 μM sulfanilamide (Sigma) and 30 μl 6 M HCl were mixed with 200 μl cell culture supernatant at room temperature and incubated for 5 min. Absorbance was measured before and after the addition of 25 μl N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamide (12.5 μM) (Sigma) at 560 nm using a microtiter plate reader. NO2− concentrations were calculated from a NaNO2 standard curve in the range of 0.5–10 μM.

Measurement of ROS

Rat alveolar macrophages were prepared as described and seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 105/well. Following LPS exposure, the fluoroprobe H2-DCFDA (1 μM) (Molecular Probes) was added for 20 min, cells were washed twice, and fluorescence was detected (λex 485 nm; λem 538 nm).

SOD activity assay

Xanthine oxidase (1 mU/ml) plus hypoxanthine (500 μM) in 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, were used as a radical generating system, and the reduction of cytochrome c (50 μM) was measured in the presence of cell homogenate samples by a spectrophotometer at 550 nm in 3-min intervals over a period of 20 min.

MS analysis of PGHS-2

Purified PGHS-2 was incubated with 0.1 μM 12-HpETE and 50 μM NO2− for 60 min. 5 μg of nitrated PGHS-2 was separated on a Beckman Coulter HPLC system with a Vydac C4 column (5 μm, 1 mm×250 mm). All fractions were collected and analyzed on a Brucker Revlex IV MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer equipped with a nitrogen laser from Laser Science having a 3-ns pulse width at 337 nm under a linear mode with a 2.5-dihydroxybenzoic acid matrix. The major fraction that contained nitrated PGHS-2 (Fig. 5B) was digested with sequencing grade trypsin (Promega) in a 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.0) at 37°C overnight and desalted by Poros 50 R1 solid-phase extraction material (Applied Biosystems). The purified and dried sample was reconstituted in 10 μl 50/50 acetonitrile/water containing 1% formic acid. This digest mixture was analyzed on a custom-built triple quadrupole Fourier transform mass spectrometer with a nanospray source and a 7T actively shielded magnet (Cryomagnetics, Inc.) (Fig. 5C). The standard ion cyclotron resonance conditions were the same as previously published (47). The data were analyzed without apodization and with two zero-fills to improve mass accuracy.

Plasmids

All genes were originally obtained from The I.M.A.G.E. Consortium. The Clone IDs are PTGS2 (PGHS-2); iratp970c0917d, SOD-1; iralp962g0610q, and NOS-2; ircmp5012g1219d. The PTGS2 (PGHS-2) gene was expressed under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate early promoter in the pCMV_SPORT6 vector (Accession No. BG913014), and this construct was used as it is. The SOD-1 gene was originally cloned in pOTB7 and recloned in the pBABE_puro vector. The NOS-2 gene was obtained as a pCR4-TOPO clone. For inducible expression, it was cloned into the bidirectional tetracycline-regulated vector pBI-5GFP. This vector is a derivative of the pBI-5 vector in which the original luc-gene was replaced by the enhanced green fluorescent protein gene. Both the NOS-2 gene and the gene for EGFP were coexpressed, allowing easy assessment of induction.

Transfection

HEK 293T cells were seeded onto six-well plates and grown to confluency. Cells in a single well were transfected with a total of 1 μg DNA complemented with 2.5 μl of lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Transfections were done according to the guidelines supplied by the manufacturer. To exclude a dose-dependent variation between the different transfections, the amount of a single plasmid was 0.25 μg. If necessary, an empty vector was added to reach 1 μg total DNA.

Twenty-four hours after transfection, the medium was exchanged, and doxycycline was added to a final concentration of 1 μg/ml for 36 h.

Statistics

All data were confirmed in at least three independent experiments. Values are expressed as the mean±standard deviation (n≥3). Data were analyzed by the one-way analysis of variance or the Student's t-test as appropriate. Differences between treatment groups in multiple comparisons were determined by the Dunnet's post hoc test (Graph Pad Prism software). Means were considered statistically significant at p<0.05.

Abbreviations Used

- 12-HpETE

12-hydroperoxy-5Z,8Z,10E, 14Z-eicosatetraenoic acid

- 3-NT

3-nitrotyrosine

- AA

arachidonic acid

- AMT

5,6-dihydro-6-methyl-4H-1,3-thiazin-2-amine

- CuDips

Cu(II)2(3,5-diisopropylsalicylate)

- DHR

dihydrorhodamine

- H2-DCFDA

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- L-NMMA

L-NG-monomethyl arginine

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MALDI-TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight

- MS

mass spectrometry

- •NO

nitric oxide

- NO2−

nitrite

- NOS-2

nitric oxide synthase-2

- •O2

superoxide

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PGG2

15-hydroperoxy prostaglandin-9,11,-endoperoxide

- PGH2

15-hydroxy prostaglandin-9,11,-endoperoxide

- PGHS

prostaglandin endoperoxide H2 synthase

- PGHS-2

prostaglandin endoperoxide H2 synthase-2

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- PPIX

protoporphyrin IX

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SDS-PAGE

sodiumdodecylsulfate–polyarylamide gel electrophoresis

- SOD-1

superoxide dismutase-1

- TxA2

thromboxane A2

- Tyr

tyrosine

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Tadashi Tanabe (The University of Osaka) for providing the antibody against TxA2-synthase, Prof. Richard Kulmacz (Houston, TX) for providing the PGHS-2 enzyme, Michael Hausding and Anna Gottschlich for analysis of HO-1 expression, and Rebecca Zee, Alicia Evangelista, and David Pimentel for helpful discussions and preparation of the article. We kindly acknowledge the continuous support and mentorship by Richard A. Cohen and Catherine E. Costello, the Boston University School of Medicine. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (SFB 969 and RTG 1331), by NIH grants PO1 HL 068758 and R37 HL104017 as well as by NHLBI, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN268201000031C. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the awarding offices.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Beckman JS. Crow JP. Pathological implications of nitric oxide, superoxide and peroxynitrite formation. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:330–334. doi: 10.1042/bst0210330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulos C. Jiang H. Balazy M. Diffusion of peroxynitrite into the human platelet inhibits cyclooxygenase via nitration of tyrosine residues. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:222–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clancy R. Varenika B. Huang W. Ballou L. Attur M. Amin AR. Abramson SB. Nitric oxide synthase/COX cross-talk: nitric oxide activates COX-1 but inhibits COX-2-derived prostaglandin production. J Immunol. 2000;165:1582–1587. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daiber A. Schildknecht S. Müller J. Kamuf J. Bachschmid MM. Ullrich V. Chemical model systems for cellular nitros(yl)ation reactions. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deeb RS. Cheung C. Nuriel T. Lamon BD. Upmacis RK. Gross SS. Hajjar DP. Physical evidence for substrate binding in preventing cyclooxygenase inactivation under nitrative stress. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3914–3922. doi: 10.1021/ja910578y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deeb RS. Hao G. Gross SS. Laine M. Qiu JH. Resnick B. Barbar EJ. Hajjar DP. Upmacis RK. Heme catalyzes tyrosine 385 nitration and inactivation of prostaglandin H2 synthase-1 by peroxynitrite. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:898–911. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500384-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deeb RS. Resnick MJ. Mittar D. McCaffrey T. Hajjar DP. Upmacis RK. Tyrosine nitration in prostaglandin H(2) synthase. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:1718–1726. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200199-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deeb RS. Shen H. Gamss C. Gavrilova T. Summers BD. Kraemer R. Hao G. Gross SS. Laine M. Maeda N. Hajjar DP. Upmacis RK. Inducible nitric oxide synthase mediates prostaglandin H2 synthase nitration and suppresses eicosanoid production. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:349–362. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietz R. Nastainczyk W. Ruf HH. Higher oxidation states of prostaglandin H synthase. Rapid electronic spectroscopy detected two spectral intermediates during the peroxidase reaction with prostaglandin G2. Eur J Biochem. 1988;171:321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ermert L. Ermert M. Merkle M. Goppelt-Struebe M. Duncker HR. Grimminger F. Seeger W. Rat pulmonary cyclooxygenase-2 expression in response to endotoxin challenge: differential regulation in the various types of cells in the lung. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1275–1287. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64998-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furse KE. Pratt DA. Porter NA. Lybrand TP. Molecular dynamics simulations of arachidonic acid complexes with COX-1 and COX-2: insights into equilibrium behavior. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3189–3205. doi: 10.1021/bi052337p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaston B. Reilly J. Drazen JM. Fackler J. Ramdev P. Arnelle D. Mullins ME. Sugarbaker DJ. Chee C. Singel DJ, et al. Endogenous nitrogen oxides and bronchodilator S-nitrosothiols in human airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10957–10961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodwin DC. Gunther MR. Hsi LC. Crews BC. Eling TE. Mason RP. Marnett LJ. Nitric oxide trapping of tyrosyl radicals generated during prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase turnover. Detection of the radical derivative of tyrosine 385. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8903–8909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunther MR. Hsi LC. Curtis JF. Gierse JK. Marnett LJ. Eling TE. Mason RP. Nitric oxide trapping of the tyrosyl radical of prostaglandin H synthase-2 leads to tyrosine iminoxyl radical and nitrotyrosine formation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17086–17090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habib A. Bernard C. Lebret M. Creminon C. Esposito B. Tedgui A. Maclouf J. Regulation of the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 by nitric oxide in rat peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 1997;158:3845–3851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huie RE. Padmaja S. The reaction of NO with superoxide. Free Radic Res Commun. 1993;18:195–199. doi: 10.3109/10715769309145868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang H. Kruger N. Lahiri DR. Wang D. Vatele JM. Balazy M. Nitrogen dioxide induces cis-trans-isomerization of arachidonic acid within cellular phospholipids. Detection of trans-arachidonic acids in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16235–16241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SF. Huri DA. Snyder SH. Inducible nitric oxide synthase binds, S-nitrosylates, and activates cyclooxygenase-2. Science. 2005;310:1966–1970. doi: 10.1126/science.1119407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klemz R. Mashreghi MF. Spies C. Volk HD. Kotsch K. Amplifying the fluorescence of bilirubin enables the real-time detection of heme oxygenase activity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulmacz RJ. Regulation of cyclooxygenase catalysis by hydroperoxides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulmacz RJ. Pendleton RB. Lands WE. Interaction between peroxidase and cyclooxygenase activities in prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase. Interpretation of reaction kinetics. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5527–5536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulmacz RJ. Wang LH. Comparison of hydroperoxide initiator requirements for the cyclooxygenase activities of prostaglandin H synthase-1 and −2. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24019–24023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landino LM. Crews BC. Timmons MD. Morrow JD. Marnett LJ. Peroxynitrite, the coupling product of nitric oxide and superoxide, activates prostaglandin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15069–15074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laskin DL. Pendino KJ. Macrophages and inflammatory mediators in tissue injury. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;35:655–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laskin DL. Sunil VR. Fakhrzadeh L. Groves A. Gow AJ. Laskin JD. Macrophages, reactive nitrogen species, and lung injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1203:60–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leone AM. Francis PL. Rhodes P. Moncada S. A rapid and simple method for the measurement of nitrite and nitrate in plasma by high performance capillary electrophoresis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200:951–957. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lombry C. Edwards DA. Preat V. Vanbever R. Alveolar macrophages are a primary barrier to pulmonary absorption of macromolecules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L1002–L1008. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00260.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marnett LJ. Wright TL. Crews BC. Tannenbaum SR. Morrow JD. Regulation of prostaglandin biosynthesis by nitric oxide is revealed by targeted deletion of inducible nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13427–13430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naraba H. Murakami M. Matsumoto H. Shimbara S. Ueno A. Kudo I. Oh-ishi S. Segregated coupling of phospholipases A2, cyclooxygenases, and terminal prostanoid synthases in different phases of prostanoid biosynthesis in rat peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 1998;160:2974–2982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palazzolo-Ballance AM. Suquet C. Hurst JK. Pathways for intracellular generation of oxidants and tyrosine nitration by a macrophage cell line. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7536–7548. doi: 10.1021/bi700123s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pendino KJ. Laskin JD. Shuler RL. Punjabi CJ. Laskin DL. Enhanced production of nitric oxide by rat alveolar macrophages after inhalation of a pulmonary irritant is associated with increased expression of nitric oxide synthase. J Immunol. 1993;151:7196–7205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfeiffer S. Lass A. Schmidt K. Mayer B. Protein tyrosine nitration in cytokine-activated murine macrophages. Involvement of a peroxidase/nitrite pathway rather than peroxynitrite. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34051–34058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100585200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfeiffer S. Lass A. Schmidt K. Mayer B. Protein tyrosine nitration in mouse peritoneal macrophages activated in vitro and in vivo: evidence against an essential role of peroxynitrite. FASEB J. 2001;15:2355–2364. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0295com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Picot D. Loll PJ. Garavito RM. The X-ray crystal structure of the membrane protein prostaglandin H2 synthase-1. Nature. 1994;367:243–249. doi: 10.1038/367243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schildknecht S. Bachschmid M. Ullrich V. Peroxynitrite provides the peroxide tone for PGHS-2-dependent prostacyclin synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. FASEB J. 2005;19:1169–1171. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3465fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schildknecht S. Heinz K. Daiber A. Hamacher J. Kavakli C. Ullrich V. Bachschmid M. Autocatalytic tyrosine nitration of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2 in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimokawa T. Kulmacz RJ. DeWitt DL. Smith WL. Tyrosine 385 of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase is required for cyclooxygenase catalysis. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20073–20076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian J. Kim SF. Hester L. Snyder SH. S-nitrosylation/activation of COX-2 mediates NMDA neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10537–10540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804852105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trostchansky A. O'Donnell VB. Goodwin DC. Landino LM. Marnett LJ. Radi R. Rubbo H. Interactions between nitric oxide and peroxynitrite during prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase-1 catalysis: a free radical mechanism of inactivation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1029–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsai AL. Wei C. Kulmacz RJ. Interaction between nitric oxide and prostaglandin H synthase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;313:367–372. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Upmacis RK. Deeb RS. Hajjar DP. Regulation of prostaglandin H2 synthase activity by nitrogen oxides. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12505–12513. doi: 10.1021/bi983049e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Donk WA. Tsai AL. Kulmacz RJ. The cyclooxygenase reaction mechanism. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15451–15458. doi: 10.1021/bi026938h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Vliet A. Eiserich JP. Halliwell B. Cross CE. Formation of reactive nitrogen species during peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of nitrite. A potential additional mechanism of nitric oxide-dependent toxicity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7617–7625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Vliet A. Eiserich JP. O'Neill CA. Halliwell B. Cross CE. Tyrosine modification by reactive nitrogen species: a closer look. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;319:341–349. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilborn J. DeWitt DL. Peters-Golden M. Expression and role of cyclooxygenase isoforms in alveolar and peritoneal macrophages. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L294–L301. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.2.L294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu W. Chen Y. Hazen SL. Eosinophil peroxidase nitrates protein tyrosyl residues. Implications for oxidative damage by nitrating intermediates in eosinophilic inflammatory disorders. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25933–25944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao C. Sethuraman M. Clavreul N. Kaur P. Cohen RA. O'Connor PB. Detailed map of oxidative post-translational modifications of human p21ras using Fourier transform mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2006;78:5134–5142. doi: 10.1021/ac060525v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]