Abstract

Aims: This study utilized proteomics, biochemical and enzymatic assays, and bioinformatics tools that characterize protein alterations in hindlimb (gastrocnemius) and forelimb (triceps) muscles in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (SOD1G93A) mouse model. The aim of this study was to identify the key molecular signatures involved in disease progression. Results: Both muscle types have in common an early down-regulation of complex I. In the hindlimb, early increases in oxidative metabolism are associated with uncoupling of the respiratory chain, an imbalance of NADH/NAD+, and an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. The NADH overflow due to complex I inactivation induces TCA flux perturbations, leading to citrate production, triggering fatty acid synthase (FAS), and lipid peroxidation. These early metabolic changes in the hindlimb followed by sustained and comparatively higher metabolic and cytoskeletal derangements over time precede and may catalyze the progressive muscle wasting in this muscle at the late stage. By contrast, in the forelimb, there is an early down-regulation of complexes I and II that is associated with the reduction of oxidative metabolism, which promotes metabolic homeostasis that is accompanied by a greater cytoskeletal stabilization response. However, these early compensatory systems diminish by a later time point. Innovation: The identification of potential early- and late-stage disease molecular signatures in an ALS model: muscle albumin, complex I, complex II, citrate synthase, FAS, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase functions as diagnostic markers and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator 1α (PGC1α), Sema-3A, and Rho-associated protein kinase 1 (ROCK1) play the role of disease progression markers. Conclusion: The differing pattern of cellular metabolism and cytoskeletal derangements in the hind and forelimb identifies the potential dysmetabolism/hypermetabolism molecular signatures associated with disease progression, which may serve as diagnostic/disease progression markers in ALS patients. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 17, 1333–1350.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease that is characterized by progressive muscular paralysis reflecting the degeneration of motor neurons in the primary motor cortex, corticospinal tracts, brainstem, and spinal cord. Approximately two thirds of patients with ALS have a spinal form of the disease (limb onset) and present with symptoms related to focal muscle weakness and wasting, where the symptoms may start either distally or proximally in the upper and lower limbs. Gradually, spasticity may develop in the weakened atrophic limbs, affecting manual dexterity and gait. Patients with bulbar onset ALS usually present with dysarthria and dysphagia for solids or liquids, and limb symptoms develop either simultaneously with bulbar symptoms or within 1–2 years. Paralysis is progressive and leads to death due to respiratory failure within 2–3 years for bulbar onset cases and within 3–5 years for limb onset ALS cases (68). Most ALS cases are sporadic, but 5%–10% of cases are familial and of these, 20% have point mutations in the gene coding for copper-zinc (Cu-Zn) superoxide dismutase (SOD1) (63). Interestingly also, 2% of the sporadic cases have a mutation in the SOD1 gene.

Several hypotheses have been suggested for the mechanism(s) of toxicity caused by these point mutation(s) in the SOD1 gene. Interestingly, SOD1 mutations such as SOD1G93A do not lead to lower SOD1 activity (27), and some actually increase SOD1 activity two- to three-fold (47). Nevertheless, the resultant SOD1 protein is dysfunctional. Goto et al. have proposed an increased structural flexibility in the proximity of the active site that reduces the specificity and enhances the reactivity of copper ions with oxidants other than superoxide (e.g., peroxides and peroxynitrite) as well as provides enhanced access of other oxidizable substrates to the active site (27). Other studies have suggested an instability and loss of Zn ions from the active site, leading to further protein unfolding (36, 58). Mutated SOD1 proteins may self-aggregate, causing an accumulation of misfolded proteins at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), possibly leading to chronic “ER stress,” production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) and degradative pathways such as autophagy (50). These effects can also be extracellular, as SOD1 is also excreted from the neurons (66).

Innovations.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease that is characterized by the selective loss of motor neurons, resulting in a progressive paralysis of skeletal muscles and respiratory failure, leading to death. Clinical biomarkers that allow a prompt diagnosis remain elusive. This study characterizes the protein alterations in hind- and forelimb muscles and identifies several potential key molecular signatures during early- and late-stage disease progression in a mouse model of ALS. These molecular signatures include muscle albumin, complex I, complex II, citrate synthase, fatty acid synthase, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase, which may serve as markers for diagnosis and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator 1α (PGC1α), Sema-3A, and Rho-associated protein kinase 1 (ROCK1), which may serve as markers of disease progression.

The transgenic SOD1 mouse, carrying the substitution of glycine at residue 93 by alanine (SOD1G93A), is a widely studied model of ALS. These mice are normal at birth and at ∼11 weeks of age, they begin to develop motor neuron dysfunctions that progress from hindlimbs to forelimbs presenting as weakness, tremors, reduced extension reflex, total paralysis, and, finally, death (5, 8, 14, 29).

Growing evidence suggests that the neuromuscular junction, the muscle(s) and cellular metabolism, and cytoskeletal processes play a key role in the disease (5–7, 15, 24–26, 28, 37, 48, 61). Significantly, neurodegeneration at the neuromuscular junction occurs before the onset of overt clinical symptoms and motor neuron death (5, 24, 25, 28). Clinical biomarkers that allow a prompt diagnosis remain elusive, despite significant advances in profiling molecular markers in cerebrospinal fluid and spinal cord in animal models and patients (9, 40, 42–44, 51).

Characterization of the molecular profile throughout disease progression in the muscle itself may identify potential clinical markers for diagnosis and monitoring as well as potential therapeutic targets. This study utilizes proteomics, biochemical and enzymatic assays, and bioinformatics tools that characterize protein alterations in the hindlimb and forelimb muscles in a mouse model of ALS with the aim of identifying several key molecular signatures during early- and late-stage disease progression.

Results

Characterization of hind and forelimb muscles in SOD1G93A mice

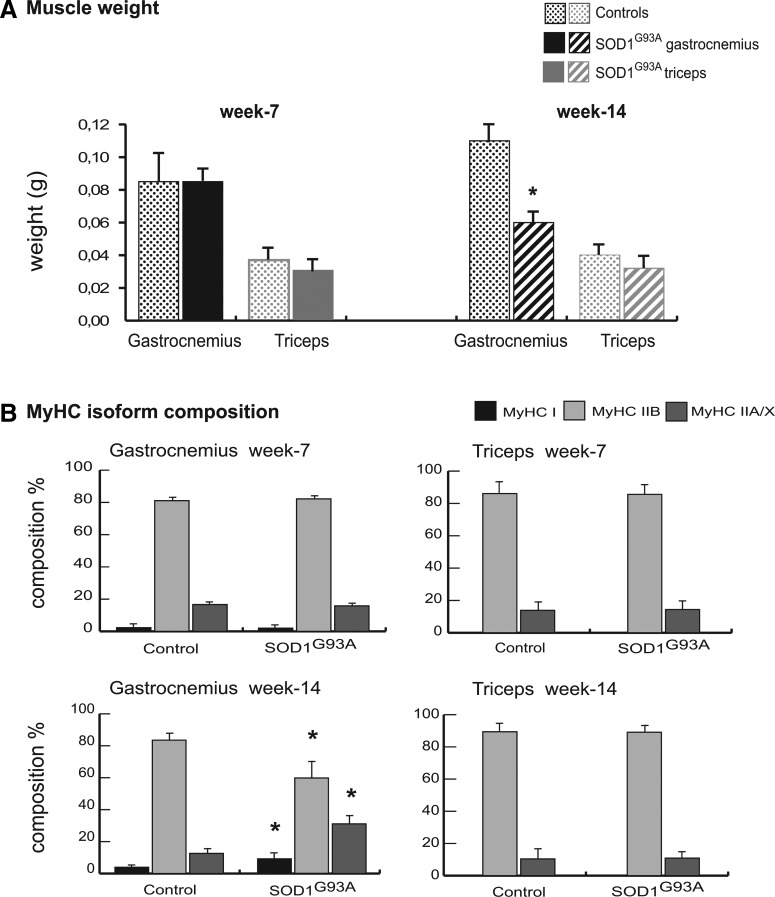

At week 7, the weight of the gastrocnemius muscles of SOD1G93A mice were similar to those of the corresponding controls; whereas at week 14, the weight was significantly reduced (Student's t-test, p<0.01; n=4). At weeks 7 and 14, the weights of the triceps muscle of the SOD1G93A mice were similar to those of the corresponding controls (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Characterization of muscles in SOD1G93A mice. (A) Weights of gastrocnemius and triceps muscles of SOD1G93A mice and control mice at week 7 and week 14. Values were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD; Student's t-test; n=4, *p<0.01). (B) Myosin heavy chain (MyHC) fiber type composition (%). Samples (1 μg) were run in duplicate at 100 V overnight. Gels were SYPRO Orange (Molecular Probes) stained, and images were acquired at 570 nm on a Typhoon 9200 laser scanner. Protein band quantification was achieved using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). Differences were computed by the Student's t-test (n=4, *p<0.01 compared with the corresponding control).

At week 7, the myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoform distributions for both muscles were similar to those of the corresponding controls. At week 14, the MyHC isoform distribution of the gastrocnemius was different from the control (Fig. 1B); whereas the content of MyHC-I (slow-twitch oxidative) and MyHC-IIA/X (fast-twitch oxidative) fibers was significantly increased in SOD1G93A mice (9% vs. 4%, 31% vs. 13%, and 9% vs. 4%, respectively; p<0.01, n=4), and that of the regenerating MyHC-IIB (fast-twitch glycolytic) fibers was significantly decreased compared with the control (60% vs. 84%; p<0.01; n=4) (Fig. 1B). At week 14, the MyHC isoform distribution of the triceps was similar to that of the control (Fig. 1B).

Proteomic analysis

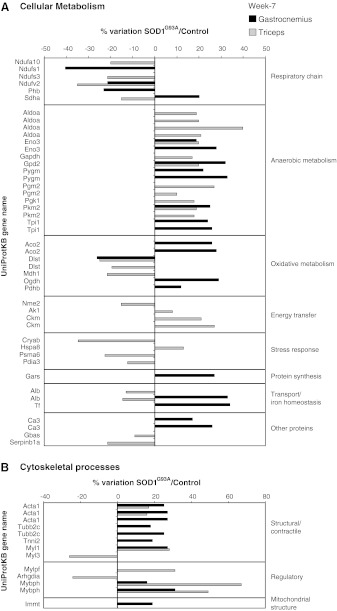

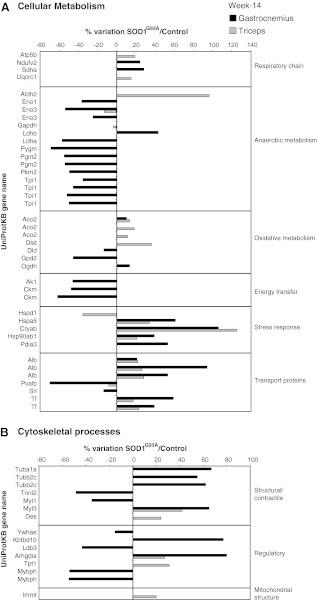

The proteomic profile showed a total of 77 (32 and 45 at week 7 and week 14, respectively) and 63 (39 and 24 at week 7 and week 14, respectively) identified spots in the gastrocnemius and triceps from SOD1G93A versus control mice respectively. At week 7, cellular metabolism was altered in both muscles, albeit to a differing extent (including a shift to a decrease in respiratory chain complex I subunits and an increase in anaerobic metabolism), and cytoskeletal processes (structural and regulatory) were also altered in both muscles (Fig. 2). At week 14, in the gastrocnemius, further alterations were observed in both cellular metabolism (including a shift to an increase in respiratory chain complex I subunits, a decrease in anaerobic metabolism, and an increase in stress response proteins) and cytoskeletal processes (including a shift to an increase in structural and contractile proteins). At week 14, in the triceps, additional alterations were observed in cellular metabolism (characterized by a shift to an increase in both oxidative metabolism and stress response proteins) and cytoskeletal processes (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Proteomic profile of SOD1G93A mice muscles at week 7. Histograms of differential protein expression in gastrocnemius (black bars) and triceps (grey bars) muscles at week 7, as detected by two-dimensional differences in gel electrophoresis (2D DIGE) analysis. Proteins significantly altered (analysis of variance [ANOVA] and Tukey, p<0.01) are expressed as a percent of spot volume variation in SOD1G93A versus control. (A) Cellular metabolism; (B) Cytoskeletal processes (structure and regulation).

- • Changes of proteins of respiratory chain activity: 2 components of NADH dehydrogenase (NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75kDa [Ndufs1], and NADH dehydrogenase ubiquinone flavoprotein 2 [Ndufv2]) and prohibitin (Phb), involved in the assembly of complex I of the respiratory chain decreased; whereas succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein (Sdha) (complex II subunit A) increased.

- • An overall increase in proteins of the anaerobic metabolism: glycolytic pathway: pyruvate kinase M2 (Pkm2) and two isoforms of glycogen phosphorylase (Pygm); triosephosphate isomerase (Tpi1) and enolase beta, (Eno3) and glycerol metabolism: glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gpd2).

- • An overall increase in the proteins of the oxidative metabolism: two isoforms of aconitate hydratase (Aco2) and pyruvate dehydrogenase beta (Pdhb). Two subunits of the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex have an opposite trend, with the dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase (Dlst) being decreased and the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase subunit (Ogdh) being increased.

- • An increase in proteins involved in: (i) protein synthesis: glycyl-tRNA synthetase (Gars), (ii) transport and iron homeostasis: albumin (Alb) and transferrin (Tf), (iii) other proteins: acid-base balance: carbonic anhydrase 3 (Ca3).

- • An increase in structural and regulatory proteins of cytoskeletal processes: alpha actin, (Acta1) and myosin binding protein H (Mybph); myosin light chain 1/3 (Myl1); troponin I, (Tnni2) and in mitochondrial inner membrane protein (Immt) and tubulin beta (Tubb2c).

- • An overall decrease in proteins of the respiratory chain activity: three components of the NADH dehydrogenase complex I (Ndufa10, Ndufs3, and Ndufv2) and succinate dehydrogenase complex II flavoprotein (Sdha).

- • An overall increase in proteins of the anaerobic metabolism: enolase beta (Eno3); fructose biphosphate aldolase (Aldoa); glyceraldheyde dehydrogenase (Gapdh); glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase (Gpd2); phosphoglucomutase 2 (Pgm2); phosphoglycerate kinase (Pgk1); and pyruvate kinase (Pkm2).

- • An overall decrease in proteins of the oxidative metabolism: dihydrolipoamide s-succinyltransferase (Dlst) and the cytoplasmic malate dehydrogenase (Mdh1).

- • Changes in proteins involved in energy transfer: decrease in nucleoside diphosphate kinase B (Nme2). Increase in Adenylate kinase (Ak1) and two isoforms of creatine kinase M-type (Ckm), a protein associated to energy transduction.

- • Changes in proteins involved in the stress response system: decrease in alpha-crystallin B chain (Cryab), proteasome subunit alpha type-6 (Psma6), and protein disulfide-isomerase A3 (Pdia3). An increase in heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein (Hspa8).

- • A decrease in proteins involved in: (i) transport and iron homeostasis: albumin (Alb), (ii) other proteins: the NipSnap homolog 2 (Gbas), a protein localized to mitochondria that plays a role in oxidative phosphorylation and in vesicular transport and Serpin peptidase inhibitor (Serpinb 1a).

- • Changes in structural and regulatory proteins of cytoskeletal processes. The majority of the identified proteins were increased: two isoforms of actin (Acta1); myosin light chain 1/3, (Myl1), myosin regulatory light chain 2 (Mylpf), and two isoforms of myosin binding protein H (Mybph), while myosin light chain 3 (Myl3) and Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor (Arhgdia) were decreased.

Note: A representative proteomic map and the identificative UniProtKB accession (AC) numbers from both muscles are shown in the Supplementary Data (Supplementary Fig. S1), along with the peptide mass fingerprint and Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry data (Supplementary Table S1A and B for gastrocnemius and Supplementary Table S2A and B for triceps muscles).

FIG. 3.

Proteomic profile of SOD1G93A mice muscles at week 14. Histograms of differential protein expression in gastrocnemius (black bars) and triceps (gray bars) muscles at week 14, as detected by 2D DIGE analysis. Proteins significantly altered (ANOVA and Tukey, p<0.01) are expressed as a percent of spot volume variation in SOD1G93A versus control. (A) Cellular metabolism; (B) Cytoskeletal processes (structure and regulation).

- • An increase in a protein of the respiratory chain activity: one component of NADH dehydrogenase (Ndufv2) and succinate dehydrogenase (Sdha).

- • An overall decrease in proteins of the anaerobic metabolism: enolase alpha (Eno1), enolase beta (Eno3), L-lactate dehydrogenase A chain (Ldha), glycogen phosphorylase (Pygm), phosphoglucomutase 2 (Pgm2) pyruvate kinase M1/M2 (Pkm2), and triosephosphate isomerase (Tpi1). An increase in Lactate dehydrogenase 2 (Ldhb).

- • Changes in the proteins of the oxidative metabolism: a decrease in glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gpd2) and dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase (Dld) and an increase in aconitate hydratase (Aco2) and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (Ogdh).

- • A decrease in proteins involved in energy transfer: adenylate kinase isoenzyme 1 (Ak1) and two isoforms of creatine kinase M-type (Ckm).

- • An increase in proteins involved in stress response: 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein (Hspa5); Cryab; Heat shock protein HSP 90-beta (Hsp90ab1); and protein disulfide-isomerase A3 (Pdia3).

- • Changes in transport and iron homeostasis proteins: an increase in serum albumin (Alb); and serotransferrin (Tf) and a decrease in parvalbumin alpha (Pvalb) and sarcalumenin (Srl).

- • Changes in structural and regulatory proteins of cytoskeletal processes: an increase in tubulin alpha-1A chain (Tuba1a); tubulin beta-2C chain (Tubb2c); myosin light chain 3 (Myl3); kelch repeat and BTB (POZ) domain containing 10 (Kbtbd10); rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 1 (Arhgdia) and a decrease in troponin I, fast skeletal muscle (Tnni2); myosin light chain 1/3, skeletal muscle isoform (Myl1); 14-3-3 protein epsilon (Ywhae); LIM domain-binding protein 3 (Ldb3); and myosin binding protein H (Mybph).

- • An increase in a protein of the respiratory chain activity: ATP synthase subunit beta (Atp5b) and cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 1 (Uqcrc1).

- • Changes in proteins related to anaerobic metabolism: an increase in aldehyde dehydrogenase (Aldh2) and a decrease in beta-enolase (Eno3) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh).

- • An increase in the proteins of the oxidative metabolism: aconitate hydratase (Aco2) and dihydrolipoyllysine-residue succinyltransferase component of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (Dlst).

- • Changes in proteins related to stress response: a decrease in mitochondrial 60 kDa heat shock protein (Hspd1) and an increase in 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein (Hspa5); Cryab and heat-shock protein HSP 90-beta (Hsp90ab1).

- • Changes in proteins involved in transport and iron homeostasis. The majority of the identified proteins were increased: three isoforms of serum albumin (Alb) and two isoforms of serotransferrin (Tf); while Pvalb was decreased.

- • An overall increase also in structural and regulatory proteins of cytoskeletal processes: myosin light chain 3 (Myl3), desmin (Des), rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 1 (Arhgdia), translationally controlled tumor protein (Tpt1), and mitochondrial inner membrane protein (Immt).

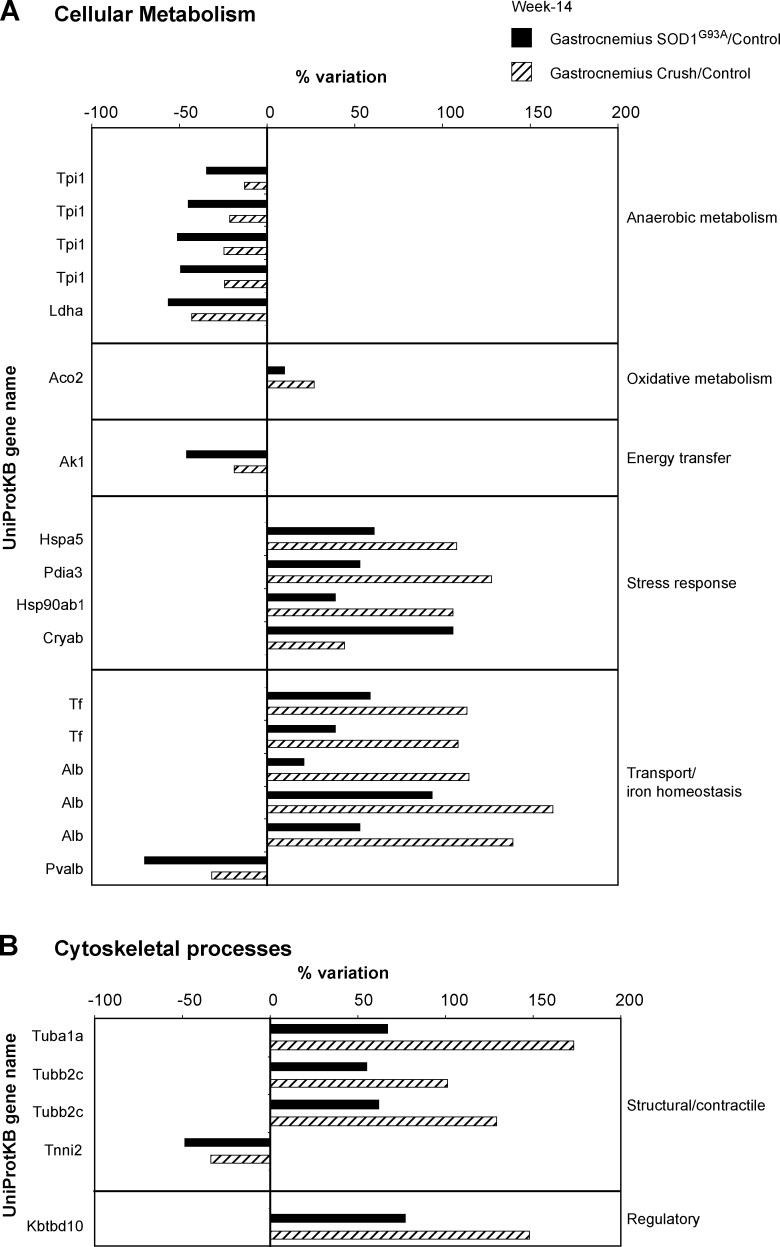

In an attempt to identify the proteomic alterations specific for ALS, an additional proteomic profile was conducted on the gastrocnemius muscle of sciatic nerve-crushed mice. The proteomic profile showed a total of 42 identified spots in the gastrocnemius from nerve-crushed mice versus control mice. Twenty-two proteins were similarly changed in the gastrocnemius of SOD1G93A and nerve-crushed mice (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Proteomic profile of nerve-crushed and SOD1G93A mice muscles. AHistograms of differential protein expression in gastrocnemius muscle (black bars) of SOD1G93A mice and gastrocnemius muscle (line bars) of nerve-crushed mice at week 14 compared with control, as detected by 2D DIGE analysis. Proteins significantly altered (ANOVA and Tukey, p<0.01) are expressed as a percent of spot volume variation in SOD1G93A or nerve-crushed versus control. (A) Cellular metabolism; (B) Cytoskeletal processes (structure and regulation).

- • An overall decrease in proteins of the anaerobic metabolism: four isoforms of Triosephosphate isomerase (Tpi1) and Lactate dehydrogenase A (Ldha).

- • An increase in protein of the oxidative metabolism: Aconitate hydratase (Aco2).

- • A decrease in protein involved in energy transfer: Adenylate kinase isoenzyme 1 (Ak1).

- • An increase in proteins involved in stress response: 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein (Hspa5); Protein disulfide-isomerase A3 (Pdia3); Heat-shock protein HSP 90-beta (Hsp90ab1), and Alpha-crystallin B chain (Cryab).

- • Changes in proteins involved in transport and iron homeostasis. Three isoforms of serum albumin (Alb) and two isoforms of serotransferrin (Tf) were increased, while parvalbumin alpha (Pvalb) was decreased.

- • Changes in structural and regulatory proteins of cytoskeletal processes: tubulin alpha-1A chain (Tuba1a); two isoforms of tubulin beta-2C chain (Tubb2c); and kelch repeat and BTB (POZ) domain containing 10 (Kbtbd10) were increased; whereas troponin I, fast skeletal muscle (Tnni2) was decreased.

Bioinformatic data analysis of molecular pathways

A bioinformatic data analysis of all the identified proteins, in both muscles at both time points, was utilized to confirm the main molecular pathways involved (MetaCore software). Alterations in two main pathways, cellular metabolism and cytoskeletal processes (structural and regulatory), were confirmed in both muscles at both time points, albeit to a differing extent. Most of the changes to the cellular metabolism (in particular, those of the respiratory chain) and cytoskeletal organization proteins (in particular, the regulatory proteins) were not observed in the proteomic analysis of the sciatic nerve-crushed mice, suggesting that these changes are specific to the SOD1G93A mice.

Biochemical analysis of molecular pathways

Cellular metabolism

Immunoblotting

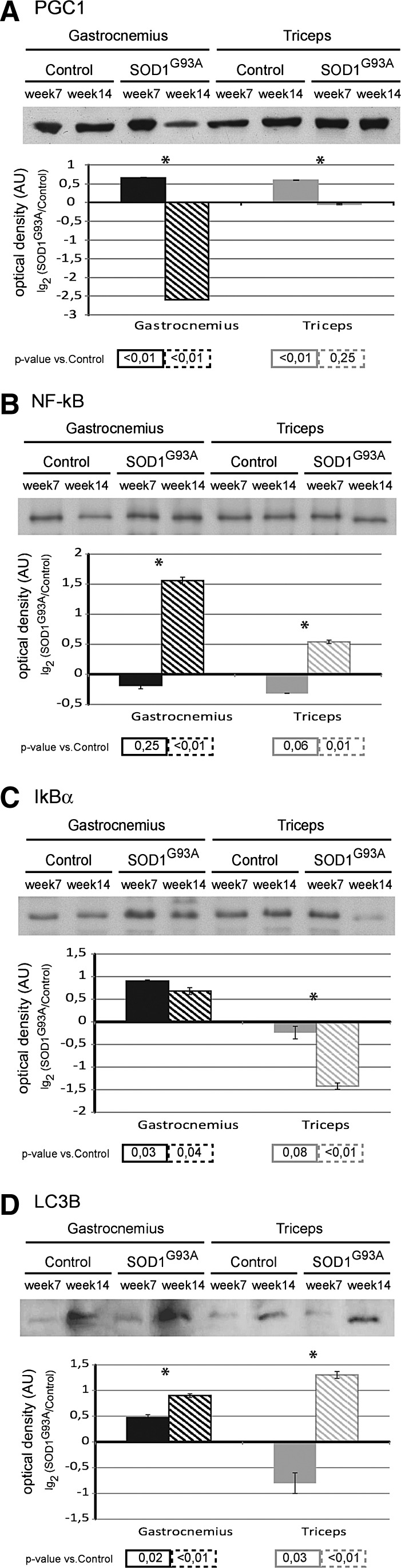

At week 7, the protein level of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator 1α (PGC1α), a transcription co-activator involved in cellular metabolism, was significantly increased in gastrocnemius and triceps muscles compared with the corresponding controls. At week 14, the level in the gastrocnemius was significantly decreased; whereas the level in the triceps returned to the control (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Biochemical analysis of biogenesis, stress response and autophagy pathways. Upper panel: Representative immunoblot images of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator 1α (PGC1α) (A), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB) p65 (B), NF-kB inhibitor alpha (IkBα) (C), and microtubule-associated protein-light chain 3 B (LC3B) (D), in gastrocnemius and triceps muscles of SOD1G93A mice and controls, at week 7 and week 14. Lower panel: Histograms of protein expression (normalized to their respective controls) in gastrocnemius and triceps muscles of SOD1G93A mice at week 7 and week 14, (mean±SD). *Significant differences (Student's t-test, n=3, p<0.05) between the time points. Significativity levels (Student's t-test, n=3) obtained by comparing the results of SOD1G93A with the control are reported below the graph (accepted as significant when p<0.05).

Note: A schematic representation of PGC1α interactions and functions is supplied in Supplementary Figure S2. Proteins differently expressed in our proteomic analysis and related to the functional classes regulated by PGC1α are represented in gray rectangles (gene symbols).

At week 7, the level of the p65 subunit of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB), a transcriptor factor, was similar to controls in both gastrocnemius and in triceps muscle. At week 14, the level was increased in both muscles (Fig. 5B).

The NF-kB inhibitor alpha (IkBα) level was increased in the gastrocnemius muscle at both week 7 and week 14. In the triceps muscle, IkBα was similar to the control at week 7, whereas the level decreased at week 14 (Fig. 5C).

At week 7, the levels of the microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 isoform B (LC3B), a protein associated to autophagosomes, were significantly increased in gastrocnemius, while they were decreased in the triceps muscle. At week 14, the LC3B protein was significantly increased in both gastrocnemius and triceps (Fig. 5D).

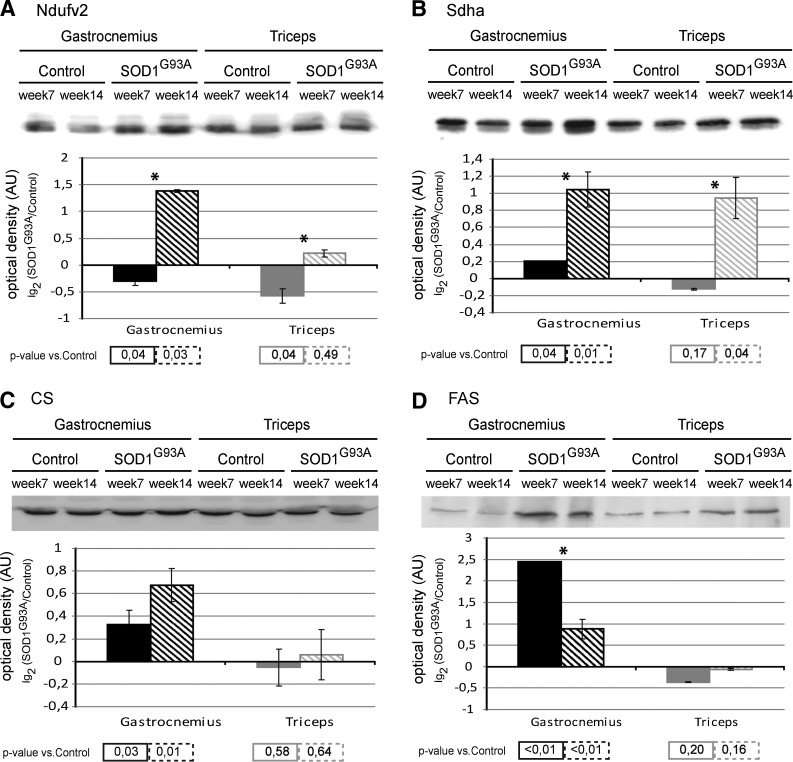

At week 7, the NADH dehydrogenase ubiquinone flavoprotein 2 (Ndufv2; a subunit of complex I of the respiratory chain) protein level of gastrocnemius and triceps muscle were significantly decreased. At week 14, the level in the gastrocnemius was significantly increased; whereas the level in the triceps returned to control levels (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Biochemical analysis of respiratory chain and lipid synthesis pathways. Upper panel: Representative immunoblot images of complex I (Ndufv2) (A), complex II (Sdha) (B), citrate synthase (CS) (C), and fatty acid synthase (FAS) (D) in gastrocnemius and triceps muscles of SOD1G93A mice and controls, at week 7 and week 14. Lower panel: Histograms of protein expression (normalized to their respective controls) in gastrocnemius and triceps muscles of SOD1G93A mice at week 7 and week 14 (mean±SD). *Significant differences (Student's t-test, n=3, p<0.05) between the time points. Significativity levels (Student's t-test, n=3) obtained by comparing the results of SOD1G93A with the control are reported below the graph (accepted as significant when p<0.05).

Note: Additional immunoblots of Ndufv2, Sdha, and CS were performed in both muscles of human wild-type SOD1 transgenic mice (SOD1Wt) and compared with those of the control (nontransgenic age-matched C57BL/6 female littermates) (Supplementary Fig. S3). No significant differences were observed.

At week 7, the succinate dehydrogenase subunit A (Sdha, a complex II enzyme that participates in both the respiratory chain and Krebs cycle) protein level of gastrocnemius muscle was significantly increased compared with the control, whereas the protein level in the triceps was similar to the control. At week 14, both the levels in the gastrocnemius and triceps were significantly increased (Fig. 6B).

At week 7 and week 14, citrate synthase (CS, the initial enzyme of the Krebs cycle, also linked with fatty acid synthesis) and the fatty acid synthase (FAS) protein levels of gastrocnemius muscle were significantly increased, whereas those of the triceps were similar to the control (Fig. 6C, D).

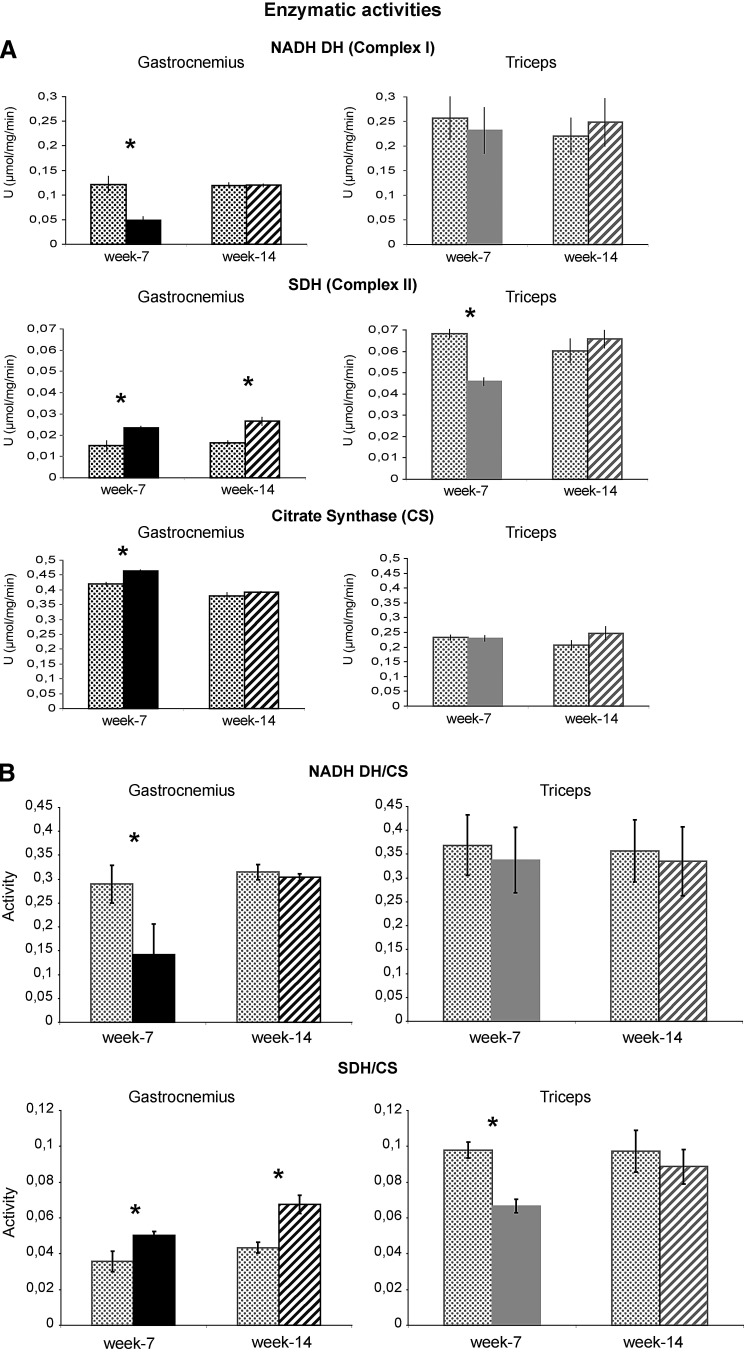

Enzymatic activity

At week 7, in the gastrocnemius muscle, the enzymatic activity of NADH dehydrogenase (complex I) was decreased compared with the control (Fig. 7) and returned to control levels at week 14. In the triceps, at both time points, NADH dehydrogenase activity was similar to the corresponding controls.

FIG. 7.

Enzymatic activity of respiratory chain complexes. Histograms showing NADH dehydrogenase (NADH DH), succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), and CS enzymatic activities on SOD1G93A and control mice at week 7 and week 14. The activities were referred to the total protein content of the samples (Units=μmol/mg/min) (A) or normalized to CS activity, a marker of mitochondrial content (B). Mean±SD, Student's t-test, n=4, *p<0.05.

Note: Additional assays of NADH DH and SDH were performed in both muscles of human wild-type SOD1 transgenic mice (SOD1Wt) and compared with those of the control (nontransgenic age-matched C57BL/6 female littermates) (Supplementary Fig. S3). No significant differences were observed.

The enzymatic activity of SDH (complex II) was increased in the gastrocnemius muscle at both week 7 and week 14; whereas in the triceps, it was decreased at week 7 compared with the control and returned to the control level at week 14 (Fig. 7).

At week 7, in the gastrocnemius, the enzymatic activity of CS was increased compared with the control and returned to control levels at week 14. In the triceps, at both time points, the enzymatic activity of CS was similar to the corresponding control (Fig. 7).

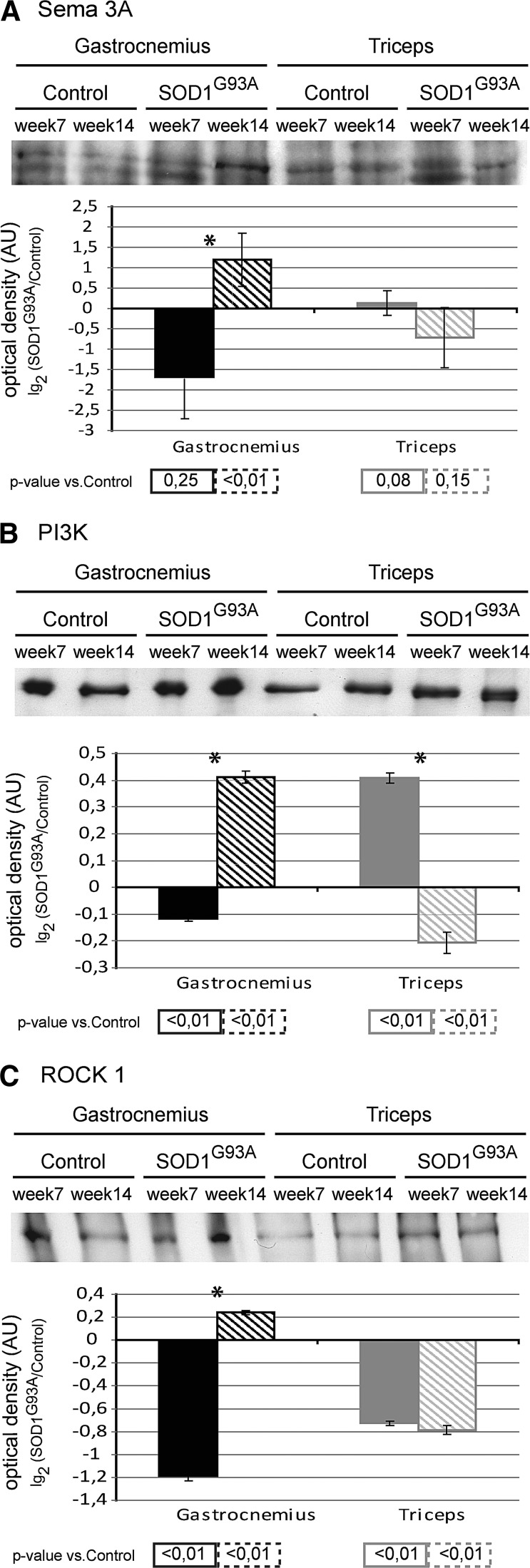

Cytoskeletal processes (structural and regulatory)

Immunoblotting

At week 7, in the gastrocnemius muscle, the protein level of Semaphorin-3A (Sema-3A) was similar to the control; whereas the protein levels of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and Rho-associated protein kinase 1 (ROCK1) were significantly decreased. By contrast, at week 7, in the triceps, the protein level of Sema-3A was similar to the control, PI3K was significantly increased, and ROCK1 was significantly decreased (Fig. 8A–C). At week 14, in the gastrocnemius, the protein levels of Sema-3A, PI3K, and ROCK1 were significantly increased. By contrast, at week 14, in the triceps, the protein level of Sema-3A was similar, whereas the protein level of PI3K decreased, and ROCK1 remained significantly decreased compared with the control (Fig. 8A–C).

FIG. 8.

Biochemical analysis of cytoskeletal processes. Upper panel: Representative immunoblot image of semaphorin-3A (Sema-3A) (A), Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) (B) and Rho-associated protein kinase 1 (ROCK1) (C) in gastrocnemius and triceps muscles of SOD1G93A mice and controls, at week 7 and week 14. Lower panel: Histograms of protein expression (normalized to their respective controls) in gastrocnemius and triceps muscles of SOD1G93A mice at week 7 and week 14, (mean±SD). *Significant differences (Student's t-test, n=3, p<0.05) between the time points. Significativity levels (Student's t-test, n=3) obtained by comparing SOD1G93A mice with control mice are reported below the graph (accepted as significant when p<0.05).

Note: A schematic representation of PI3K interactions and functions is supplied in Supplementary Figure S2. Proteins differently expressed in our proteomic analysis and related to the functional classes regulated by PI3 are represented in gray rectangles (gene symbols).

Discussion

This study analyzes the molecular signatures of the hind- and forelimb muscles (gastrocnemius and triceps, respectively) at two different time points in the SOD1G93A mouse. This model is widely studied, as it resembles several forms of human ALS. There are, however, some differences, as, although both exhibit a progressive motor neurodegeneration and a paralysis of the skeletal muscle, the mouse model always exhibits clinical signs in the hindlimb first. In human ALS, clinical signs and symptoms also occur in the upper body (e.g., bulbar onset ALS), reflecting a broader etiology. With regard to the lower body signs and symptoms, hindlimb muscles are larger with a higher metabolic rate, a higher O2 consumption, and a higher blood flow compared with their forelimb counterparts. As such, it seems that the high metabolic dependency of the hindlimb muscle may play a causative role in the greater loss of the muscle function at an earlier stage due to a greater susceptibility to alterations in energy production (55). The etiology of upper body signs and symptoms remains unknown. Nevertheless, both the mouse model and human ALS exhibit muscle dysmetabolisn/hypermetabolism in association with disease progression (10, 15, 20, 21, 23).

At week 7, the time point represents the early stage of the disease where the functional assessments are still normal (5, 8, 14, 29). From 11 weeks onward, SOD1G93A mice begin to develop the signs and symptoms of motor-neuron dysfunction that progresses from the hindlimbs to the forelimbs, presenting as weakness, tremors, reduced extension reflex, total paralysis, and, finally, death (5, 8, 14, 29). Therefore, the week-14 time point represents the later stage of the disease where functional assessments are impaired (5, 8, 14, 29).

In an attempt to distinguish the molecular signatures specific for the ALS model versus those associated with denervation itself, this study also compares the proteomic profile of the SOD1G93A mouse with that of the “nerve-crush” mouse model. Significantly, nontransgenic, age-matched C57BL/6 female mice were used as controls. A limitation of proteomics analysis is the inability to identify proteins in the range of pico to femtomoles. We have overcome this, using bioinformatic tools, associated with specific immunoblotting and enzymatic assays. This detailed and thorough scientific design enables the characterization of protein alterations in hindlimb and forelimb muscles with the aim of identifying several key molecular signatures during early- and late-stage disease progression.

This study shows that the weight of the hindlimb muscle but not the forelimb muscle in SOD1G93A mice decreases from week 7 to week 14, suggesting that the hindlimb only is undergoing atrophy over this time period. This change is supported by a modification of fiber-type distribution with an increase in MyHC type-I and IIA oxidative isoforms and a decrease in the MyHC-IIB fast glycolytic isoform, confirming muscle wasting. These results are in accordance with previous reports that muscle wasting is observed in the hindlimbs before the forelimbs (5, 8, 14, 29). In this study, we further show that the hindlimb muscle undergoes cellular metabolism and cytoskeletal alterations (structural and regulatory) at week 7 before the clinical signs and symptoms of muscle wasting at week 14.

Week 7

At week 7, proteomic analysis shows that, in hindlimb and forelimb muscles, cellular metabolism is altered, albeit to a differing extent. In both muscles, a decrease is observed in the respiratory chain complex I subunits with an increase in anaerobic metabolism. In the hindlimb, this is associated with an increase in complex II subunit and oxidative metabolism. Complexes uncoupling (decrease of complex I and increase of complex II) is consistent with an increase in the NADH/NAD+ (and probably FAD/FADH2) ratio, a condition that results in significant mitochondrial superoxide production (46). By contrast, the forelimb is associated with a decrease in complex II subunit and oxidative metabolism. This is supported by immunoblotting and enzymatic analysis, which shows that in the hindlimb muscle, there is a significant decrease in complex I associated with an increase in complex II; whereas, in the forelimb, there is a decrease in complex I and complex II.

Interestingly, in the hindlimb, albumin (Alb) increases; whereas in the forelimb, albumin (Alb) decreases. Increased levels of albumin in the muscles can be of physiological importance, aiding the enhanced transport demands related to increased metabolic activity. However, in pathological states in muscles that do not exhibit increased metabolic demands, albumin may accumulate in muscle fibers as a result of sarcolemmal lesions, altering the concentration of albumin-bound substances such as hormones or fatty acids. In this regard, albumin has been suggested as an early marker for muscle cell damage (19).

Moreover, transferrin, a glycoprotein that delivers extracellular iron (Fe) to the cells in soluble form, increases only in the hindlimb. This may be an early compensatory response to excess free iron, which catalyzes the formation of ROS, such as hydroxyl radical, and either initiates or enhances lipid peroxidation (57). Indeed, increases in free iron have been reported in neurological diseases, including ALS (13, 33).

In the hindlimb, there is also an increase in carbonic anhydrase (Ca3), an enzyme that catalyzes the rapid inter-conversion of carbon dioxide and water to bicarbonate. Since bicarbonate induces peroxidase activity of the SOD protein (39, 69), its increase could lead to the further oxidation of substrates and the additional formation of protein aggregates.

At week 7, immunoblotting analysis shows an elevation of PGC1α, in both hindlimb and forelimb muscles. PGC1α is induced by oxidative stressors and itself represents an important suppressor of further intracellular ROS levels (1, 22, 30, 59, 62, 64). Oxidative stress has been suggested as being one of the key inducers of muscle atrophy with ROS activating downstream NF-kB and, ultimately, autophagy. Indeed, the elevated PGC1α may play a role in suppressing the induction of further ROS production at an early stage, as the level of the p65 subunit of the transcription factor NF-kB remains unchanged in both muscles at week 7. Moreover, the inhibitor of NF-kB activation, IkBα, increases significantly in the hindlimb muscle, while it remains unchanged in the forelimb, suggesting a further compensatory mechanism. The major constituent of the autophagosome LC3B increases in the hindlimb and slightly decreases in the forelimb muscle, supporting the hypothesis of the early activation of autophagy in the hindlimb. The hindlimb also shows an increase in the mitochondrial inner membrane protein (Immt), which is essential for normal mitochondrial function. This suggests the activation of an additional compensatory mechanism, while no changes were observed in the forelimb at this time point.

In the hindlimb, stress proteins were unchanged at this time point; whereas in the forelimb, the heat shock 70 protein 8 (Hspa8) was increased, and other stress proteins, mainly involved in UPR (i.e., alpha-crystallin B chain [Cryab], Psma6, and Pdia3), were decreased. The reasons for these apparently disparate changes are unclear but may be associated to early proteasome inhibition (3).

Immunoblotting analyses also indicate that the CS protein (a marker of mitochondrial activity) and FAS protein (that catalyzes the formation of long-chain fatty acids) significantly increase in the hindlimb muscle. This may be the result of the changes in the NADH/NAD+ (and probably FAD/FADH2) ratio caused by the decrease in complex I and the increase in complex II, in an attempt to restore the energetic metabolism (e.g., by replenishing cytosolic NAD+ through the pyruvate/citrate cycling). The increase in FAS observed in the hindlimb muscle appears to be directly linked not only to the metabolic dysfunction and increase in NADH and acetyl-CoA but also to PGC1α (22, 44, 56, 64) and is related to ER stress (35). The lack of changes in the FAS level in the forelimb is in line with the down-regulation of complexes I and II and the observed decrease of cytoplasmic malate dehydrogenase (Mdh1), which acts as a signal driving the excess of citrate through the urea cycle.

At week 7, proteomic analysis also shows that, in hindlimb muscle, a second cellular pathway is altered which is related to cytoskeletal processes that include dysregulation in proteins responsible for muscle contraction, muscle fiber regeneration, and cytoskeletal remodeling. This is also evident in the forelimb muscle but to a much lesser extent. Cytoskeletal stabilization in both muscles appears to be activated through increases in myosin binding protein H (Mybph) (a structural protein of the sarcomeric A-band which contributes to the inhibition of ROCK1, a kinase of the Rho cytoskeletal-remodeling signaling pathway) (31). However, the forelimb muscle shows a greater increase in Mybph, indicating a greater cytoskeletal stabilization response.

Immunoblotting analysis shows that the associated cytoskeletal processes involved in the maintenance of neuromuscular junction are also altered. ROCK1 decreases in both the hindlimb and forelimb muscle, which is consistent with the increase in Mybph as just discussed.

PI3K decreases in the hindlimb muscle, resulting in a downstream reduction of cytoskeleton remodeling (34, 60) and growth factor signaling, as PI3K acts as a signal transducer between receptor tyrosine kinases, cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, motility, and intracellular trafficking (2, 41, 49, 65). By contrast, PI3K increases in the forelimb, which may reflect an important compensatory response mechanism in this muscle.

Sema-3A, a signature of motor neurodegeneration, is unchanged in both muscles. This suggests that at week 7, in the hindlimb muscle, several adverse cellular metabolism and cytoskeletal alterations precede muscle wasting. By contrast, several protective cellular metabolism and cytoskeletal compensatory mechanisms are activated in the forelimb muscle.

Week 14

At week 14, proteomic analysis shows that in hindlimb and forelimb muscles, cellular metabolism is altered further. In the hindlimb but not the forelimb muscle, the respiratory chain complexes I and II subunits increase, whereas the anaerobic metabolism decreases (with the exception of lactate dehydrogenase that increases), which may suggest an attempt to compensate a potential NADH overflow. Furthermore, by week 14, the stress response proteins (Pdia3, Hspa5, Cryab, and Hsp90ab1) are also increased in both muscles, resulting in abnormalities in protein folding machinery at the ER and engagement of the UPR. These results are in agreement with other studies showing an up-regulation of UPR genes and associated proteins in SOD1G93A mice (4, 50) with, at the late stage of the disease, an increase in Cryab (11, 53).

At week 14, the levels of albumin and transferrin in the hindlimb remain elevated, and an increase is also observed in the forelimb. At this time point, in the hindlimb, the calcium-regulatory proteins parvalbumin and sarcalumenin decrease, which may reflect an increased availability of myofibrillar calcium (parvalbumin also decreases in the forelimb, but to a lesser extent).

In the forelimb muscle, there is a significant increase in oxidative metabolism and an increase in mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (Aldh2), a detoxification enzyme that functions as a protector of oxidative damage. Of particular interest is the increase in Dlst, a protein that maintains several anti-oxidants systems, including Aldh2. There is also a decrease in Hspd1, a mitochondrial chaperon protein, suggesting mitochondrial impairment.

At week 14, immunoblotting analysis shows that in the hindlimb muscle, there are significant increases in both complexes I and II subunits; whereas, in the forelimb, complex I subunits return to the control level, and complex II subunit significantly increases. Enzymatic analysis shows that there is a significant increase in complex II activity in the hindlimb muscle only. These results may suggest that, despite the changes occurring at the protein level, the functionality of the complexes is still maintained, possibly in an attempt to compensate for the changes observed. In addition, immunoblotting analysis shows that PGC1α significantly decreases in the hindlimb muscle and returns to control levels in the forelimb muscle. A decrease in PGC1α may lead to an impaired mitochondrial respiratory function, an increase in ROS, and enhanced mitochondrial apoptotic susceptibility.

At week 14, NF-kB increases in both muscles, whereas IkBα increases in the hindlimb and significantly decreases in the forelimb, suggesting a loss of compensatory antioxidant mechanisms in the hindlimb compared with the forelimb. Moreover, LC3B remains elevated in the hindlimb muscle, indicating a further activation of autophagy and subsequent muscle atrophy. At week 14, the forelimb muscle also shows an increase in LC3B, suggesting an initiation of autophagy in this muscle.

CS protein and FAS protein remain significantly elevated in the hindlimb muscle only, despite the FAS protein level being significantly decreased compared with week 7. This is in agreement with recent findings suggesting that the expression of PGC1α enhances the use of fatty acids, preventing the inhibition of FAS (44). These changes, combined with the observed impaired mitochondria biogenesis, represent a molecular profile that is indicative of damage to muscle fibers and the loss of functionality (16, 56). The PGC1α profile in the hindlimb muscle is in accordance with the results observed in this muscle recently reported in a different ALS model (38).

At week 14, proteomic analysis shows that, in hindlimb and forelimb muscles, cytoskeletal processes are further altered, which include detrimental changes in proteins responsible for muscle contraction and muscle fiber regeneration, although this is still more evident in the hindlimb muscle. The ROCK1 inhibitor, Mybph, decreases in the hindlimb, promoting a cytoskeletal remodeling environment that can have detrimental effects on neuromuscolar junction structures, while Mybph returns to control levels in the forelimb muscle, suggesting that the initial cytoskeletal stabilization response, occurring at week 7, is decreasing.

At week 14, Immt returns toward normal in the hindlimb muscle, which suggests that the early attempt to maintain the normal mitochondrial functionality is failing and that mitochondrial biogenesis is waning. In addition, at this time point, Immt shows an increase in forelimb muscle, suggesting the activation of compensatory mechanism(s).

Immunoblotting analysis further shows that other cytoskeletal processes involved in the maintenance of the neuromuscular junction are altered; PI3K subunit increases in the hindlimb muscle and decreases in the forelimb muscle. In the hindlimb muscle, ROCK1 significantly increases; whereas in the forelimb, ROCK1 remains low. By contrast, Sema-3A increases in the hindlimb muscle, although it remains unaltered in the forelimb muscle. An increase in Sema-3A has been reported to lead to de-adhesion or repulsion of motor axons away from the neuromuscular junction, resulting in axonal denervation and motor neurodegeneration at the presynaptic side with muscular fiber loss and atrophy at the postsynaptic side (52). Sema-3A expression has also been reported to significantly increase in the terminal Schwann cells of fast-fatigable type IIB and IIX muscle fibers at the neuromuscular-junction in SOD1G93A mice (18, 52).

The differing pattern of cellular metabolism and cytoskeletal derangements in the muscles, observed in our study, provides a compelling association of these changes with a greater and more rapid onset of muscle wasting in the hindlimb and a slower onset and lesser functional impairment in the forelimb muscle. This is consistent with previous studies reporting that muscle dysmetabolism/hypermetabolism is associated with disease progression in ALS animal models and patients (10, 15, 20, 21, 23).

In particular, our study shows that both muscle types have a common early down-regulation of complex I, albeit with different functional outcomes. In the hindlimb, oxidative metabolism increases, producing uncoupling of the respiratory chain, NADH/NAD+ imbalance with an increase in ROS production. The NADH overflow due to complex I inactivation induces TCA flux perturbations, leading to citrate production, which triggers FAS and lipid peroxidation. These early metabolic changes in the hindlimb followed by sustained and greater metabolic and cytoskeletal derangements lay the foundation for progressive muscle wasting. Further studies will be required to ascertain why there is a failure of the normal physiological compensatory mechanisms in this muscle over time. It maybe that the higher muscle mass, higher oxygen consumption, and higher metabolic rate and energy requirements simply overwhelm the homeostatic mechanisms available.

By contrast, in the forelimb muscle, the down-regulation of complex I is associated with a general reduction in oxidative metabolism. The muscle appears to retain a more normal functionality by initiating physiological compensatory mechanisms, which are able to cope with the overall lesser metabolic demand. Nevertheless, these compensatory systems ultimately also show a progressive diminution over time, leading to the reported forelimb paralysis and death that occur in this model beyond the timespan of this study (>18 weeks).

Our data identify several potentially key molecular signatures during early- and late-stage disease progression in a mouse model of ALS. These molecular signatures include muscle albumin, complex I, complex II, CS, FAS, PI3K, PGC1α, Sema-3A, and ROCK1. The challenge in future will be to determine how these may serve as potential clinical markers for the diagnosis and monitoring of the disease progression.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Reagents and equipments, except when differentially stated, were purchased from GE Healthcare or Sigma-Aldrich.

Animal models

Transgenic SOD1G93A mice and sample collection

Transgenic SOD1G93A female mice (Jackson Laboratories) were used in the study (bred and maintained on a C57BL/6 mouse strain at Harlan Italy s.r.l, Bresso, Milan). Transgenic mice were identified by PCR (54).

Nontransgenic age-matched C57BL/6 female mice were used as controls for both the SOD1G93A and the nerve-crushed mice.

Transgenic SOD1G93A and control mice were sacrificed either at week 7 (n=4 female mice per group) or at week 14 (n=4 female mice per group). The gastrocnemius and triceps muscles were removed, weighed, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissues were ground in a dry ice-cooled mortar and stored at −80°C.

Nerve-crushed mice and sample collection

Nontransgenic age-matched C57BL/6 female mice (Harlan Italy) were used in the sciatic nerve-crushed model. The mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of equithesin (1% phenobarbitol, 4% chloral-hydrate, 3 μl/g). The sciatic nerve, that innervates the gastrocnemius muscle, was crushed by mechanical pressure using Martin 20-307-14 forceps (Germany Stainless) applied at 5 mm proximal to the trifurcation of the right sciatic nerve. This results in nerve degeneration followed by localized inflammation that lasts for up to 4 weeks. Nerve-crushed animals (n=4 female mice) were sacrificed 2 weeks after the injury (14 weeks of age). The gastrocnemius was removed, frozen, and stored at −80°C.

All the procedures involving animals and their care were conducted in conformity with the institutional procedures in compliance with national (D.L. No. 116, G.U. Suppl. 40, Feb. 18, 1992, Circolare No. 8, G.U., 14 Luglio 1994) and international regulations (EEC Council Directive 86/609, OJ L 358, 1 DEC.12, 1987; NIH Guide for the Care and use of Laboratory Animals, U.S. National Research Council, 1996).

Expression of human SOD1G93A protein

The SOD1G93A protein level was analyzed by immunoblotting and resulted in being unchanged in both muscles at both time points (Student's t-test, n=4; p<0.05), confirming the stability of the model during the study (Supplementary Fig. S4; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars).

Characterization of muscles in SOD1G93A mice

Muscle weight

Before being frozen in liquid nitrogen, the muscles were weighed using a calibrated electronic balance. Differences between the groups were computed by the Student's t-test.

MyHC isoforms composition

Sodium-dodecyl-sulfate electrophoresis was performed as previously described (17). Differences between groups were computed by the Student's t-test. A two-tail F-test was applied in order to verify the homoscedasticity of variances.

Protein extraction

Two-dimensional differences in gel electrophoresis (2D DIGE) and immunoblots: an aliquot of each frozen muscle was suspended in lysis buffer (urea 7 M, thiourea 2 M, CHAPS 4%, Tris 30 mM, and PMSF 1 mM) and solubilized by sonication on ice. Proteins were selectively precipitated using PlusOne 2D-Clean-up kit in order to remove nonprotein impurities and re-suspended in lysis buffer. Protein extract was adjusted to pH 8.5 by the addition of NaOH 1 M solution, and sample concentrations were determined using PlusOne 2D-Quant kit. Enzymatic activity assays: Samples were extracted using Dounce homogeneizer in potassium phosphate 5 mM pH 7.2, sucrose 220 mM, KCl 20 mM, and Hepes 10 mM pH 7.2 and immediately assayed.

Proteomic analysis

Two-dimensional difference in gel electrophoresis

Protein labeling, 2D separation and analysis (for SOD1G93A, control, and nerve-crushed mice; n=4 animals per group per time point) were performed as previously described (12). The proteomic profile of the SOD1G93A mice was compared with the correspondent control in both gastrocnemius and triceps muscles at both time points. An additional proteomic profile was conducted on the gastrocnemius muscle of nerve-crushed animals 2 weeks after nerve crush (14 weeks of age) and compared with the profile of SOD1G93A and control mice at week 14.

Statistically significant differences of 2D DIGE data were computed by an independent one-way analysis of variance coupled to Tukey's multiple-group comparison test (p<0.01). False discovery rate was applied as multiple test correction in order to keep the overall error rate as low as possible. Power analysis was conducted on statistically changed spots; only spots that reached a sensitivity threshold >0.8 were considered as differentially expressed.

Protein identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

Proteins were identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight utilizing the method previously described (67).

In cases where this approach was unsuccessful, additional searches were performed using electrospray ionization-MS/MS, as previously described (12).

The protein identification was validated performing a random analysis via 2D-immunoblotting of 15% of the identified proteins (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Bioinformatic data analysis of molecular pathways

The MetaCore software (GeneGo, Inc., V6.3 build 25177), using two different bioinformatics analyses (“Enrichment Ontologies” and “Analyze Network”), was used to search for the protein-protein interaction networks (for SOD1G93A, control, and nerve-crushed mice).

Biochemical analysis of molecular pathways

Immunoblotting

Protein extracts (50 μg) from pooled SOD1G93A and control muscles, at both time points, were loaded in triplicate and resolved on 6%, 8%, and 10% polyacrylamide gels, according to protein molecular weight. Blots were incubated with rabbit or goat polyclonal primary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology except when differently stated) as follows: anti-PGC1α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-NF-kB, anti-IkBα, anti-LC3B, anti-Ndufv2, anti-Sdha, anti-CS (Abcam), anti-FAS, anti-Sema-3A (Abcam), anti-PI3K, and anti-ROCK1. After washing, the membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit (GE Healthcare) or anti-goat (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. The signals were visualized by chemiluminescence using the ECL Plus or the ECL Advance (Ndufv2, Sdha) detection kit.

An image analysis system (Image Quant TL, Molecular Dynamics) was performed followed by statistical analysis (Student's t-test, p<0.05).

Enzymatic assays

NADH dehydrogenase activity (complex I) was analyzed by a spectrophotometric assay (32).

Succinate dehydrogenase activity (complex II) was analyzed by a colorimetric-continuous method (45).

CS was analyzed by a spectrophotometric assay (Sigma, cat. #CS0720).

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Cryab

alpha-crystallin B chain

- CS

citrate synthase

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FAS

fatty acid synthase

- IkBα

NF-kB inhibitor alpha

- Immt

mitochondrial inner membrane protein

- LC3B

microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 B

- MALDI

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization

- Mybph

myosin binding protein H

- MyHC

myosin heavy chain

- Ndufv2

NADH dehydrogenase ubiquinone flavoprotein 2

- NF-kB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- PGC1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator 1α

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- ROCK1

Rho-associated protein kinase 1

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Sdha

succinate dehydrogenase subunit A

- ToF

time-of-flight

- UPR

unfolded protein response

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Antonia Orsi and Dr. Daryl Rees, at Salupont Consulting Ltd., for their critical editorial comments on this article. This work has been funded by MIUR (grant FIRB RBRN07BMCT to C.G.) and by Telethon (grant GGP08107D to C.G.) and the European Community's Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013) under the Health Cooperation Program grant agreement n. 259867 (to C.B.).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Adhihetty PJ. Uguccioni G. Leick L. Hidalgo J. Pilegaard H. Hood DA. The role of PGC-1alpha on mitochondrial function and apoptotic susceptibility in muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C217–C225. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00070.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amano M. Nakayama M. Kaibuchi K. Rho-kinase/ROCK: A key regulator of the cytoskeleton and cell polarity. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2010;67:545–554. doi: 10.1002/cm.20472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amanso AM. Debbas V. Laurindo FR. Proteasome inhibition represses unfolded protein response and Nox4, sensitizing vascular cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced death. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkin JD. Farg MA. Walker AK. McLean C. Tomas D. Horne MK. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and induction of the unfolded protein response in human sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azzouz M. Leclerc N. Gurney M. Warter JM. Poindron P. Borg J. Progressive motor neuron impairment in an animal model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:45–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199701)20:1<45::aid-mus6>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrett EF. Barrett JN. David G. Mitochondria in motor nerve terminals: function in health and in mutant superoxide dismutase 1 mouse models of familial ALS. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2011;43:581–586. doi: 10.1007/s10863-011-9392-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendotti C. Calvaresi N. Chiveri L. Prelle A. Moggio M. Braga M. Silani V. De Biasi S. Early vacuolization and mitochondrial damage in motor neurons of FALS mice are not associated with apoptosis or with changes in cytochrome oxidase histochemical reactivity. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00627-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bendotti C. Carri MT. Lessons from models of SOD1-linked familial ALS. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergemalm D. Forsberg K. Jonsson PA. Graffmo KS. Brannstrom T. Andersen PM. Antti H. Marklund SL. Changes in the spinal cord proteome of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis murine model determined by differential in-gel electrophoresis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:1306–1317. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900046-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouteloup C. Desport JC. Clavelou P. Guy N. Derumeaux-Burel H. Ferrier A. Couratier P. Hypermetabolism in ALS patients: an early and persistent phenomenon. J Neurol. 2009;256:1236–1242. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5100-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calabrese V. Highlight Commentary on “Redox proteomics analysis of oxidatively modified proteins in G93A-SOD1 transgenic mice—a model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis”. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:160–162. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capitanio D. Vasso M. Fania C. Moriggi M. Vigano A. Procacci P. Magnaghi V. Gelfi C. Comparative proteomic profile of rat sciatic nerve and gastrocnemius muscle tissues in ageing by 2-D DIGE. Proteomics. 2009;9:2004–2020. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carri MT. Ferri A. Cozzolino M. Calabrese L. Rotilio G. Neurodegeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the role of oxidative stress and altered homeostasis of metals. Brain Res Bull. 2003;61:365–374. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu AY. Zhai P. Dal Canto MC. Peters TM. Kwon YW. Prattis SM. Gurney ME. Age-dependent penetrance of disease in a transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1995;6:349–362. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1995.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crugnola V. Lamperti C. Lucchini V. Ronchi D. Peverelli L. Prelle A. Sciacco M. Bordoni A. Fassone E. Fortunato F. Corti S. Silani V. Bresolin N. Di Mauro S. Comi GP. Moggio M. Mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction in muscle from patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:849–854. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cutler RG. Pedersen WA. Camandola S. Rothstein JD. Mattson MP. Evidence that accumulation of ceramides and cholesterol esters mediates oxidative stress-induced death of motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:448–457. doi: 10.1002/ana.10312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danieli Betto D. Zerbato E. Betto R. Type 1, 2A, and 2B myosin heavy chain electrophoretic analysis of rat muscle fibers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;138:981–987. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(86)80592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Winter F. Vo T. Stam FJ. Wisman LA. Bar PR. Niclou SP. van Muiswinkel FL. Verhaagen J. The expression of the chemorepellent Semaphorin 3A is selectively induced in terminal Schwann cells of a subset of neuromuscular synapses that display limited anatomical plasticity and enhanced vulnerability in motor neuron disease. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;32:102–117. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupont-Versteegden EE. Kitten AM. Katz MS. McCarter RJ. Elevated levels of albumin in soleus and diaphragm muscles of mdx mice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1996;213:281–286. doi: 10.3181/00379727-213-44061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dupuis L. Gonzalez de Aguilar JL. Echaniz-Laguna A. Eschbach J. Rene F. Oudart H. Halter B. Huze C. Schaeffer L. Bouillaud F. Loeffler JP. Muscle mitochondrial uncoupling dismantles neuromuscular junction and triggers distal degeneration of motor neurons. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupuis L. Loeffler JP. Neuromuscular junction destruction during amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: insights from transgenic models. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espinoza DO. Boros LG. Crunkhorn S. Gami H. Patti ME. Dual modulation of both lipid oxidation and synthesis by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha and -1beta in cultured myotubes. FASEB J. 2010;24:1003–1014. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-133728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fergani A. Oudart H. Gonzalez De Aguilar JL. Fricker B. Rene F. Hocquette JF. Meininger V. Dupuis L. Loeffler JP. Increased peripheral lipid clearance in an animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:1571–1580. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700017-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer LR. Culver DG. Tennant P. Davis AA. Wang M. Castellano-Sanchez A. Khan J. Polak MA. Glass JD. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a distal axonopathy: evidence in mice and man. Exp Neurol. 2004;185:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frey D. Schneider C. Xu L. Borg J. Spooren W. Caroni P. Early and selective loss of neuromuscular synapse subtypes with low sprouting competence in motoneuron diseases. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2534–2542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-07-02534.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez de Aguilar JL. Niederhauser-Wiederkehr C. Halter B. De Tapia M. Di Scala F. Demougin P. Dupuis L. Primig M. Meininger V. Loeffler JP. Gene profiling of skeletal muscle in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. Physiol Genomics. 2008;32:207–218. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00017.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goto JJ. Zhu H. Sanchez RJ. Nersissian A. Gralla EB. Valentine JS. Cabelli DE. Loss of in vitro metal ion binding specificity in mutant copper-zinc superoxide dismutases associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1007–1014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gould TW. Buss RR. Vinsant S. Prevette D. Sun W. Knudson CM. Milligan CE. Oppenheim RW. Complete dissociation of motor neuron death from motor dysfunction by Bax deletion in a mouse model of ALS. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8774–8786. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2315-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurney ME. Pu H. Chiu AY. Dal Canto MC. Polchow CY. Alexander DD. Caliendo J. Hentati A. Kwon YW. Deng HX, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Handschin C. Kobayashi YM. Chin S. Seale P. Campbell KP. Spiegelman BM. PGC-1alpha regulates the neuromuscular junction program and ameliorates Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Genes Dev. 2007;21:770–783. doi: 10.1101/gad.1525107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosono Y. Yamaguchi T. Mizutani E. Yanagisawa K. Arima C. Tomida S. Shimada Y. Hiraoka M. Kato S. Yokoi K. Suzuki M. Takahashi T. MYBPH, a transcriptional target of TTF-1, inhibits ROCK1, and reduces cell motility and metastasis. EMBO J. 2012;31:481–493. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janssen AJ. Trijbels FJ. Sengers RC. Smeitink JA. van den Heuvel LP. Wintjes LT. Stoltenborg-Hogenkamp BJ. Rodenburg RJ. Spectrophotometric assay for complex I of the respiratory chain in tissue samples and cultured fibroblasts. Clin Chem. 2007;53:729–734. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.078873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeong SY. Rathore KI. Schulz K. Ponka P. Arosio P. David S. Dysregulation of iron homeostasis in the CNS contributes to disease progression in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2009;29:610–619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5443-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolsch V. Charest PG. Firtel RA. The regulation of cell motility and chemotaxis by phospholipid signaling. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:551–559. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee AH. Scapa EF. Cohen DE. Glimcher LH. Regulation of hepatic lipogenesis by the transcription factor XBP1. Science. 2008;320:1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1158042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lelie HL. Liba A. Bourassa MW. Chattopadhyay M. Chan PK. Gralla EB. Miller LM. Borchelt DR. Valentine JS. Whitelegge JP. Copper and zinc metallation status of copper-zinc superoxide dismutase from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2795–2806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.186999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q. Vande Velde C. Israelson A. Xie J. Bailey AO. Dong MQ. Chun SJ. Roy T. Winer L. Yates JR. Capaldi RA. Cleveland DW. Miller TM. ALS-linked mutant superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) alters mitochondrial protein composition and decreases protein import. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21146–21151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014862107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang H. Ward WF. Jang YC. Bhattacharya A. Bokov AF. Li Y. Jernigan A. Richardson A. Van Remmen H. PGC-1alpha protects neurons and alters disease progression in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44:947–956. doi: 10.1002/mus.22217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liochev SI. Fridovich I. Copper, zinc superoxide dismutase and H2O2. Effects of bicarbonate on inactivation and oxidations of NADPH and urate, and on consumption of H2O2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34674–34678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lukas TJ. Luo WW. Mao H. Cole N. Siddique T. Informatics-assisted protein profiling in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1233–1244. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500431-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maekawa M. Ishizaki T. Boku S. Watanabe N. Fujita A. Iwamatsu A. Obinata T. Ohashi K. Mizuno K. Narumiya S. Signaling from Rho to the actin cytoskeleton through protein kinases ROCK and LIM-kinase. Science. 1999;285:895–898. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Massignan T. Casoni F. Basso M. Stefanazzi P. Biasini E. Tortarolo M. Salmona M. Gianazza E. Bendotti C. Bonetto V. Proteomic analysis of spinal cord of presymptomatic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis G93A SOD1 mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maurer MH. Proteomics of brain extracellular fluid (ECF) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Mass Spectrom Rev. 2010;29:17–28. doi: 10.1002/mas.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menendez JA. Fine-tuning the lipogenic/lipolytic balance to optimize the metabolic requirements of cancer cell growth: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munujos P. Coll-Canti J. Gonzalez-Sastre F. Gella FJ. Assay of succinate dehydrogenase activity by a colorimetric-continuous method using iodonitrotetrazolium chloride as electron acceptor. Anal Biochem. 1993;212:506–509. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagai M. Aoki M. Miyoshi I. Kato M. Pasinelli P. Kasai N. Brown RH., Jr. Itoyama Y. Rats expressing human cytosolic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase transgenes with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: associated mutations develop motor neuron disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9246–9254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09246.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Napoli L. Crugnola V. Lamperti C. Silani V. Di Mauro S. Bresolin N. Moggio M. Ultrastructural mitochondrial abnormalities in patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1612–1613. doi: 10.1001/archneur.68.12.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Narumiya S. Ishizaki T. Watanabe N. Rho effectors and reorganization of actin cytoskeleton. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nassif M. Matus S. Castillo K. Hetz C. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis pathogenesis: a journey through the secretory pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:1955–1989. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pasinetti GM. Ungar LH. Lange DJ. Yemul S. Deng H. Yuan X. Brown RH. Cudkowicz ME. Newhall K. Peskind E. Marcus S. Ho L. Identification of potential CSF biomarkers in ALS. Neurology. 2006;66:1218–1222. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000203129.82104.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pasterkamp RJ. Giger RJ. Semaphorin function in neural plasticity and disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poon HF. Hensley K. Thongboonkerd V. Merchant ML. Lynn BC. Pierce WM. Klein JB. Calabrese V. Butterfield DA. Redox proteomics analysis of oxidatively modified proteins in G93A-SOD1 transgenic mice—a model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosen DR. Siddique T. Patterson D. Figlewicz DA. Sapp P. Hentati A. Donaldson D. Goto J. O'Regan JP. Deng HX, et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;362:59–62. doi: 10.1038/362059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rosser BW. Norris BJ. Nemeth PM. Metabolic capacity of individual muscle fibers from different anatomic locations. J Histochem Cytochem. 1992;40:819–825. doi: 10.1177/40.6.1588028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rowe GC. Jiang A. Arany Z. PGC-1 coactivators in cardiac development and disease. Circ Res. 2010;107:825–838. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sadrzadeh SM. Saffari Y. Iron and brain disorders. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121(Suppl):S64–S70. doi: 10.1309/EW0121LG9N3N1YL4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sahawneh MA. Ricart KC. Roberts BR. Bomben VC. Basso M. Ye Y. Sahawneh J. Franco MC. Beckman JS. Estevez AG. Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase increases toxicity of mutant and zinc-deficient superoxide dismutase by enhancing protein stability. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:33885–33897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.118901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sandri M. Lin J. Handschin C. Yang W. Arany ZP. Lecker SH. Goldberg AL. Spiegelman BM. PGC-1alpha protects skeletal muscle from atrophy by suppressing FoxO3 action and atrophy-specific gene transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16260–16265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607795103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sasaki AT. Firtel RA. Regulation of chemotaxis by the orchestrated activation of Ras, PI3K, and TOR. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:873–895. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Siklos L. Engelhardt J. Harati Y. Smith RG. Joo F. Appel SH. Ultrastructural evidence for altered calcium in motor nerve terminals in amyotropic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:203–216. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.St-Pierre J. Drori S. Uldry M. Silvaggi JM. Rhee J. Jager S. Handschin C. Zheng K. Lin J. Yang W. Simon DK. Bachoo R. Spiegelman BM. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006;127:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Strong M. Rosenfeld J. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a review of current concepts. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2003;4:136–143. doi: 10.1080/14660820310011250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Summermatter S. Baum O. Santos G. Hoppeler H. Handschin C. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor {gamma} coactivator 1{alpha} (PGC-1{alpha}) promotes skeletal muscle lipid refueling in vivo by activating de novo lipogenesis and the pentose phosphate pathway. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32793–32800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tolias KF. Duman JG. Um K. Control of synapse development and plasticity by Rho GTPase regulatory proteins. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;94:133–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Urushitani M. Sik A. Sakurai T. Nukina N. Takahashi R. Julien JP. Chromogranin-mediated secretion of mutant superoxide dismutase proteins linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:108–118. doi: 10.1038/nn1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vigano A. Vasso M. Caretti A. Bravata V. Terraneo L. Fania C. Capitanio D. Samaja M. Gelfi C. Protein modulation in mouse heart under acute and chronic hypoxia. Proteomics. 2011;11:4202–4217. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wijesekera LC. Leigh PN. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang H. Andrekopoulos C. Joseph J. Chandran K. Karoui H. Crow JP. Kalyanaraman B. Bicarbonate-dependent peroxidase activity of human Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase induces covalent aggregation of protein: intermediacy of tryptophan-derived oxidation products. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24078–24089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.