Abstract

Community knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices are essential in any diarrhoea research. This cross-sectional study addresses these questions ill a semi-urban community in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. The study included 344 subjects and 276 controls v/’ all age groups. Most people had reasonable knowledge of diarrhoea. Mothers o/’ children with diarrhoea continued to fired them during the attack. However, some community practices were found to be harmful. The majority of diarrhoea cases neither sought medical attention, nor used oral rehydration salts (ORS) at home. Instead, they resorted to faulty self-medication. Overall use of ORS was 53%; much less than expected. Education of health personnel on ORS might improve its use. It was found that the community needs to be educated on the benefits of hand washing before meals and after changing soiled diapers, washing of eggs and the use of boiled water for the preparation of infant preparing feeds.

Keywords: Diarrhoea, Knowledge, Attitude and Practice

INTRODUCTION

Diarrhoea is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the developing world1. A number of studies on diarrhoea have been recently published in Saudi Arabia. However, only few studies have been conducted in the Eastern Province and even these are mostly retrospective and confined to children.2,3

The knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of the community are important in any research on diarrhoea. Equally important are the patterns of infant feeding, weaning and other practices. This study addresses these aspects as well as the use of oral rehydration therapy (ORT).

METHODS

Study Area & Population

The population for this study was drawn from Thogba; a typical new and urbanized township with a high Saudi population. It is part of a metropolitan complex of the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Thogba has a population made up of all socio-economic groups. The prevalence of diarrhoeal disease can therefore be expected to be considerable.

The study population comprised Saudis of all age groups. A 10% sample of the households gave us 580 households, all of which were visited. After surveying the community for diarrhoea, a control group, matched for age & sex, was also randomly selected from the same community.

For the purpose of the study, acute diarrhoea was defined as a “significant change in bowel habits toward decreased consistency and increased frequency of not more than five days duration as described by the individual or parent of a child”4. A structured questionnaire was designed to collect information on basic personal data, eating and personal habits, infant feeding, concepts of diarrhoea, home management of diarrhoea, and Oral Rehydration Salts (ORS).

The questionnaire contained open and close-ended questions in simple Arabic similar to that spoken by the locals in Thogba. The questionnaire was tested in a pilot study for validation purposes and was consequently improved afterwards. The final version was administered by a team of interviewers composed of senior resident doctors in the King Faisal Fellowship Program in Family and Community Medicine. The team was trained and headed by one of the investigators (H.B).

Answers were checked on daily basis during the field work for completeness and feedback was given to the interviewers. Although the majority of respondents were fathers, mothers were called by the interviewers whenever it was felt that the father was in doubt or could not give precise information.

As the field work proceeded, it was realized that diarrhoea cases were not as many as expected and this was the reason why adult cases were included. So the study population included all age groups. When the “case” was a child, the father/mother was asked to answer the questions.

A data base was created for analysis of data and a Biomedical Computer Program Package (BHCP) was used.

RESULTS

The size of the population was 344, out of which 68 were cases and 276 controls. There was identical distribution of the different age groups in the community but children predominated; 72% for cases and 76% for controls. The distribution of sex in the study group was more variable; there were more cases recorded in males (60%) than in females (40%).

KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDES & PRACTICES

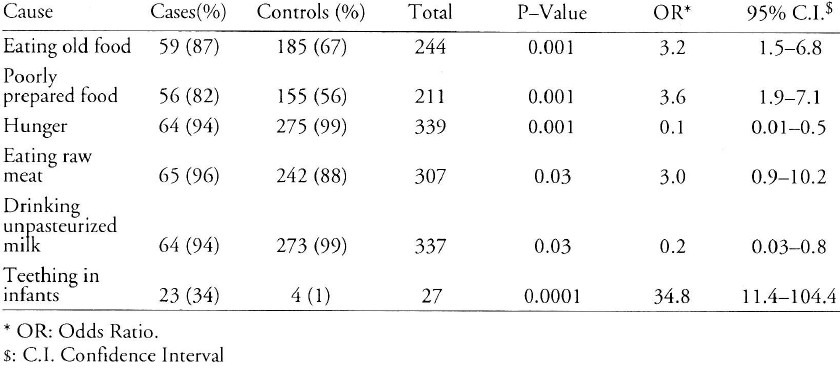

When asked to define Diarrhoea, more cases than controls gave a better definition (P value = 0.0001). Table 1 shows what the cases and controls in the community considered as causes of diarrhoea. More cases than controls thought that (i) eating old food or (ii) poorly prepared food or (iii) raw meat and (iv) teething in infants caused diarrhoea. These differences were significant, (P values of 0.0001, 0.0001, 0.03 and 0.0001 respectively). On the other hand, more controls (99%) than cases O4′%) associated the drinking of unpasteurized milk with diarrhoea. The difference was also statistically significant (P<0.03).

Table 1.

Causes of Diarrhoea according to respondents in the community

INFANT FEEDING DURING DIARRHOEA & MILK FEED PREPARATION

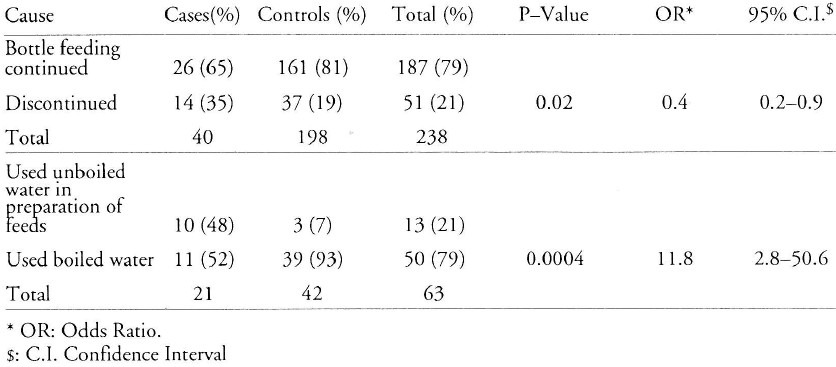

Table 2 shows the infant feeding pattern during diarrhoea as well as preparation of milk. The data show that significantly more mothers of control children than of cases would continue to bottle feed their children during diarrhoea (P<0.02). The use of boiled water in preparing infant milk was found to be significantly asso-ciated with fewer cases of diarrhoea in these infants than in those for whom unboiled water was used. It was also found that many more children in the control group had their feeding bottles cleaned with boiled water than was the case in children who had diarrhoea. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.002).

Table 2.

Feeding pattern during diarrhoea and milk feed preparation

WASHING OF EGGS AND HANDS AND DIARRHOEA

With regard to hand washing, a significant difference in the desirable habit of hand washing after diaper change was found between controls (78%) and cases (35%) (P value < 0.001). Similarly, more Controls washed their hands before meals than did cases.

It was also found that in both study populations more controls than cases washed eggs before use, 80% and 44%, respectively; (P < 0.0001).

HOME MANAGEMENT OF DIARRHOEA AND USE OF ORS

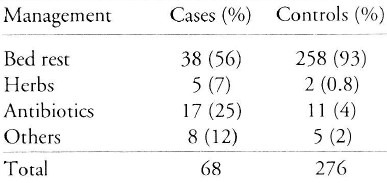

Table 3 shows the home management of diarrhoea for cases and controls. Self medication with antibiotics was practised in both popula-tion groups but was significantly more so among cases than controls (P = 0.0001). Interestingly, only a few subjects in both groups used herbs for the management of diarrhoea. When asked to recall the types of home remedies without being prompted, none of the respondents mentioned the use of ORS. However, when its use was sug-gested to them, 54% of the controls 49% cases admitted using ORS. The overall use of ORS in the community did not exceed 53% of cases and controls. Most cases and controls considered bed rest important.

Table 3.

Home Management of diarrhoea

DISCUSSION

Health workers in every society must be conversant with the concepts on diarrhoeal disease held by the local population, since wrong concepts would be harmful. Every effort should be directed towards educating the population about these wrong ideas whenever they are detected. In this study, it was noted that most of the people had reasonable knowledge of what diarrhoea is. Only a minority of the population still hold on to the belief that teething in an infant is a cause of diarrhoea. However, when the “practices” of the population were considered, it was found that there were several deficiencies that would have to be addressed. For example, the practice of washing hands either before eating or after changing a child's soiled diaper needs to be actively encouraged through the use of effective visual aids to demonstrate the transmission of endemic pathogens into the mouth through contaminated hands.

Health education of this and other points related to diarrhoea could be achieved through the mass media in a health education program to be designed and conducted by the primary health care program administrators. Boys and girls’ schools are appropriate places for such education on diarrhoea.

As the community is becoming more literate, much can be done through leaflets and posters in clinics, shops and schools. Indeed, ORS could easily and safely be sold in ordinary shops and canteens the way Aspirin is in some countries.

Similarly, it is obvious that the population is not aware that the shells of eggs can be contaminated by bacteria especially Salmonella,5 and therefore should be adequately cleaned before being broken for use to avoid contaminating the food with pathogens. Another harmful practice recorded, was that a significantly fewer number of mothers of cases of children did not use boiled water when preparing feeds for them. This fact becomes even more crucial when it is realized that although the drinking water is from taps, it is collected from public taps and stored in tanks. Such water may subsequently become contaminated during storage.

The majority of patients with acute, self-limiting diarrhoea never seek medical attention6 and resort to self-medication including restriction of fluids and foods, administration of injections by unauthorized personnel, and using opiates and purgatives. Such practices can be harmful as was found in a study in India.7 In our study, as many as 92% of the study population were not inclined to send their children to see a “Doctor”, but instead treated them at home or sought assistance from pharmacists and traditional healers.

These practices contrast sharply with the findings in studies from India7 and Kenya8 were between 63-70% of mothers preferred modern system of management. Home management, however, can be desirable if the appropriate treatment is given. Indeed, it is the recommend-ed policy of both the WHO and UNICEF that ORS be used successfully at home.9

It is recommended that feeding of the child be continued during attacks of diarrhoea to prevent malnutrition. In infants, breast feeding in particular has been found beneficial by either aborting the diarrhoea or hastening recovery. Breast milk is also known to provide protection against infections such as Salmonella.10,11,12 In the study population, the mothers of children with diarrhoea continued to feed them.

The overall use of ORS in the community (53%) was much lower than that found by Abbad & Bella in the same area13 However, these investigators interviewed mothers, whereas in the present study most questions were responded to by fathers, who may, therefore, have underestimated the use of ORS. The education of health personnel including doctors about ORS is important to promote. Since it has been reported that health workers were the source of information about ORS for mothers13 we therefore strongly recommend that its use be stressed in the training of health personnel including doctors. This would ensure that they will be able to teach and use ORS confidently at all levels of health care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walsh J A, Warren K S. Selective Primary Health Care: An Interim Strategy of Disease Control in Developing Countries. N Eng J Med. 1970;301:67–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197911013011804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.EI-Mouzan M I, Abumelha A. Clinical Aspects of gastroenteritis in Saudi Arabian Children. Trop Gastroent. 1984;5(1):35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abumelha A, El-Mouzan M I, Refaat M. Gastroenteritis in the Eastern Province: Epidemiology and Etiology. Trop Gastroent. 1982;3(5):217–221. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du Pont H. Enteropathogenic Organisms: New etiologic agents and concepts of disease. Med Clin N Amer. 1978;62(5):945–960. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts D. Sources of Infectious Diseases. Lancet. 1990;336:859–861. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92352-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Pont D. Diarrhoeal Diseases: An Overview. A J Med. 1985;78(Suppl B):63–64. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar V. Beliefs and Therapeutic Preference of Mothers in Management of Acute Diarrhoeal Disease in Children. J Trop Paediatric. 1985;31:109. doi: 10.1093/tropej/31.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maina-Ahlberg B. Beliefs and Practices Concerning Treatment of Measles and Acute Diarrhoea Among the Akamba. Trop Georgr Med. 1979;31:139–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morely D, Lovel H. My Name is Today. London: Macmillan; 1989. p. 250. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham S D. Morbidity in Breast Fed and Artificially Fed Infants. J Paed. 1979;95:685–689. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80711-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watkinson M. Delayed Weaning Diarrhoea: Association with High Breast Milk Intake. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1981;75:432–435. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(81)90113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.France G L, Mariner D L, Steele R W. Breast feeding and Salmonella Infection. Am J Dis Child. 1980;134(2):147–152. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1980.02130140021007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AI-Abbad A, Bella H. Diarrhoea in the under-Ewes in a Saudi-Semi Urban Community. Trop Georgr Medicine. 1990;42:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]