Abstract

This study on the perception of infant feeding practices was conducted among unmarried girls from two randomly selected Saudi public schools in Al-Khobar. Though it was encouraging to note that the attitude of the, girls was largely in favour of breast feeding, many deficiencies were identified in their knowledge of infant feeding. 67.1 % students were unaware of the importance of colostrum and 70.5% opted for scheduled feeding over demand feeding. To 40.2% girls an optimum duration of 18-24 months for breast Feeding was not desirable. A large proportion of students lacked knowledge on the methods of promoting lactation such as early suckling (51.4%), frequent suckling (40%) and “rooming-in” (37.9%). Only 28% of the girls knew the correct age of introducing solid food. With the present trend of decline in the duration of breastfeeding in Saudi Arabia, the schools could play an important role in training and motivating future mothers for proper infant feeding practices.

Keywords: breast-feeding, weaning, school health education

INTRODUCTION

While a remarkable resurgence of breast-feeding has been observed in the industrialized countries since the 1970s, a downward trend in breast-feeding during the last 20 years in developing countries has caused increased concern among the promoters of child health and development. Bottle feeding in these countries has become a symbol of modernity. In particular, the urban educated and well-to-do mothers have been observed to resort to bottle feeding early in the post-natal period1,2.

Saudi Arabia is no exception to this behavioural change. The present trend indicates that though most mothers start with breast-feeding, the duration of feeding is now shorter and supplementary milk is introduced in the early months3,4. The traditional practice of breast-feeding for 2 years is now uncommon particularly in urban areas. The question is, can timely intervention with target groups reverse the present trend?

Several studies3,5–8 have been conducted in the past on the practice of breast-feeding and weaning among Saudi mothers but no attempt has been made to evaluate the knowledge and attitude of would-be mothers towards this vital issue of child health. Hence, this study was carried out to investigate the perception of infant feeding practices among unmarried Saudi high school girls and identify the need for a health education programme at school level.

MATERIAL AND METHODOLOGY

Unmarried high school girls from the urban area of Al-Khobar in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia were the target population of the study. The sample population was drawn from the government schools in the area. There are six government schools at secondary level in the area, each with an enrollment of 300-400 students. The schools cater for a socio-economically homogeneous population. For the purpose of sampling, a school was considered as the unit of selection. Two schools were chosen randomly out of the six and all students of grades ten, eleven and twelve from these schools were considered for inclusion in the sample population. Out of a total of 622 students enrolled in these two schools, 589 (94.7%) girls were included in the study. The remaining students were either absent on the day of the investigation or were married and therefore excluded from the sample. Their ages ranged from 16 to 19 years. Each school was interviewed in one day in December 1990 and the students were not informed about the contents of the questionnaire prior to the investigation.

A questionnaire with both open ended and structured questions was used. These were related to the attitude of the students towards breast-feeding, their awareness of the importance of breast milk and colostrum, duration and schedules of breast-feeding, its role in spacing pregnancy and the factors affecting lactation such as “rooming-in”, day of initiation of breast-feeding, night feeding and food intake during lactation. Questions were also put regarding the age of introduction of solid food (weaning) and preferred foods for weaning. The questionnaire was pretested on 20 high school level girls and modifications were made as necessary. Responses to the questions were self-administered by the students.

RESULTS

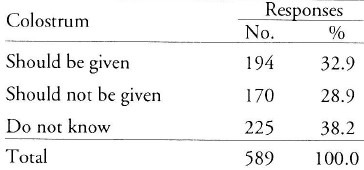

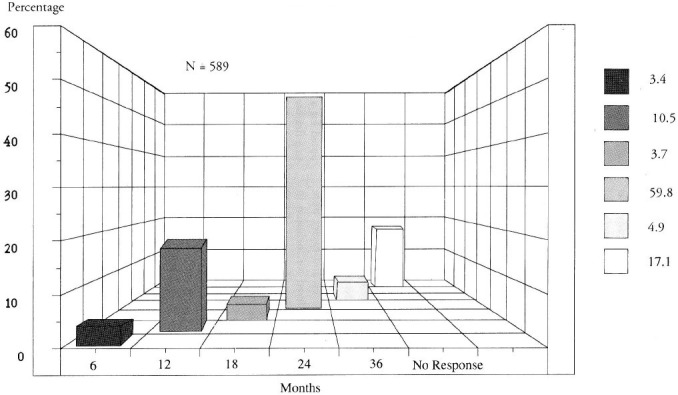

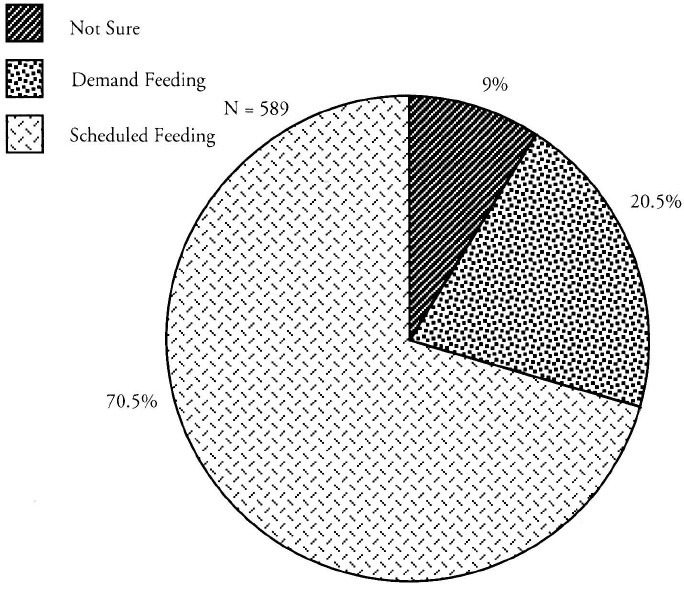

Out of 589 students, 541 (91.8%) believed that the mother's milk was ideal for the proper growth and health of the baby compared to only 41 (7.0%) girls who thought cow's milk was superior. Table 1 shows that while 194 (32.9%) students perceived the importance of colostrum, 170 (28.9%) did not and 225 (38.2%) girls preferred not to comment because of lack of knowledge. While more than one half of the stu-dents (59.8%) were of the opinion that the opti-mum duration of breast-feeding should be 18-24 months, 40.2% students were in favour of other time periods or could not comment (Fig. 1). An enquiry was made regarding preference for demand or scheduled feeding for the health of the baby. The majority of students (70.5%) opted for a rigid 3-4 hours schedule compared to a flexible feeding regime (Fig. 2). 59.8% girls were in favour of night feeding while 20.0% were not. There were varying responses to the idea of feeding a premature baby with breast milk. Two hundred and twelve (36.0%) students considered it possible whereas 182 (30.9%) and 195 (33.1%) did not agree or could not comment, respectively.

Table 1.

Distribution of students by Perceived Importance of Colostrum

Figure 1.

Preferred Duration of Breast Feeding

Figure 2.

Preference of Type of Breast Feeding

An assessment of the perception of students of some factors influencing successful breast-feeding showed that nearly half of them (48.6%) were unaware of the importance of suckling the baby on the first day of birth to improve milk production. Moreover, 40% of the students did not appreciate the fact that frequent suckling increased the quantity of breast milk. A few girls (10%) thought frequent suckling would lead to decreased milk supply.

For better lactation 366 (62.1%) and 70 (11.9%) students respectively favoured “rooming-in” and a neonatal nursery. The remaining 153 (26%) girls did not respond. A majority of the students (90.5%) believed that a lactating mother should eat more than her usual diet to improve the quality of her breast milk as well as for her own health.

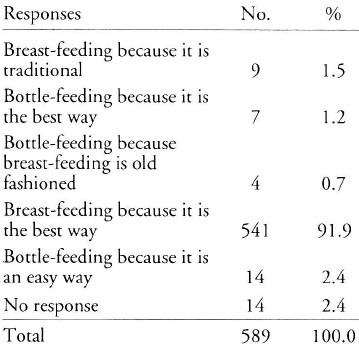

Students were almost equally divided in their knowledge of drug excretion in human milk. While 205 (34.8%) girls perceived such a possibility, 173 (29.4%) did not think so and 218 (37.0%) stated that they were unaware of this. An enquiry on whether breast-feeding could always prevent pregnancy was responded to in the affirmative by 32.9% students while 45% girls were skeptical of this fact. It was encouraging to note that the attitudinal response of students for breast-feeding their own babies in future was positive. Table 2shows that the majority of the girls (91.9%) stated that they would opt for this practice because it was “the best way” for the baby to attain good health.

Table 2.

Attitude of Students for Self-Practice of Breast-feeding in Future

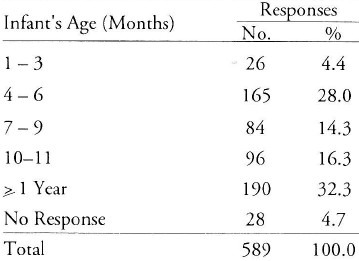

Less than a third (28%) of the students knew that 4-6 months was the correct age to introduce solid food to a baby. Some (32.3%) girls suggested that weaning time could be as late as one year or more (Table 3). A long list of weaning foods was provided by the students.

Table 3.

Distribution of students According to Preferred Time of Weaning

Common items of food mentioned were pureed fruits and vegetables (46.5%) and cerelac (10.9%). Few girls suggested eggs (7.3%), biscuits (6.5%), rice (3.2%) and dates (0.3%). One hundred and seventeen students (19.9%) did not make any suggestions.

DISCUSSION

It has been observed that breast-feeding has been on the decline as urbanization, education and standards of living increase.9 In Saudi Arabia, where the per capita GNP is high, urbanization has reached 80% and female education is on the increase4 , breast-feeding is less favoured and the period is shorter now2–3 compared to that observed in 195110 or even a decade ago.5,11,12 However, the present status of breast-feeding in the Kingdom which is around 50%2–4 of babies being breastfed at six months is much higher than that in other developing countries such as Nigeria13 and Chile14 where only 1% and 11% infants respectively, were reported to be breast-fed at that age.

A recent national survey on breast-feeding in Saudi Arabia showed a significant impact of education and socio-economic status on the duration of breast-feeding2. Rising female literacy brings about greater exposure to international literature, mass media and a tendency to emulate the modern world. Unlike some countries where socio-economic circumstances have prevented mothers from resorting to bottle feeding15 , in Saudi Arabia, the easy availability of baby milk formulae and the ability of the local population to purchase them appear to play a major role in influencing a mother's decision to cease breast-feeding early5.

The findings of the present study are a reflection of the school-going female population of Al-Khobar in the age group of 16 to 19 years. Hence, these results cannot be generalised to cover other areas or a non-school going population.

It was encouraging to note in the present study that a majority of the students (91.8%) believed in the importance of breast-feeding for the growth and health of the baby and intended to follow this practice in future. A large proportion of girls (59.8%) also favoured prolonged breast-feeding up to two years. This attitude results from an injunction in the Quran that “a mother shall breast-feed her child for two years”. Moreover, the perception of students for breast-feeding has also been possibly influenced by beliefs and practices of their mothers who belong to a generation that had been advocates of breast-feeding. While this positive attitude among students was highly commendable, some deficiencies in their knowledge on the advantages and methods of breast-feeding raises concern. Often these reasons have been the lack of motivation, failed lactation and early weaning among present day mothers.

A large proportion of girls (67.1%) did not appreciate the value of colostrum. This finding was also reflected in the practices of Saudi mothers in Turaba8 and Al-Khobar7 . However, demand feeding which is common in the country2,7,8 was surprisingly not favoured by 70.5% students. Many students had little knowledge on the importance of night feeding (40.2%), breast milk for premature babies (64.0%), the methods of successful lactation which include when to initiate breast suckling (48.6%) and frequency of suckling (40%), or knew the correct age of introducing semi-solid food (72.0%) and the value of high energy weaning foods. Surprisingly, almost none of the students in this urban-based study mentioned any traditional Saudi weaning foods such as ‘mulhalibich’ (milk and starch), ‘foul’ (beans), ‘jereesh’ (wheat) and ‘addax’ (lentils). Only 2 (0.3%) students mentioned dates.

The curriculum of government schools in this region includes some aspects of mother craft and home economics but the information provided is elementary and is taught during primary school years only, at age 8-11 years. Educational and psychological motivation for healthy child care practices, if provided at higher academic (intermediate and secondary schools), levels and age would he more meaningful to the students for their future needs. According to Hochbaum16, one of the purposes of school health education is“… to enable children to make sensible decisions when they face new situations for which they have not been directly prepared”. Accurate and supportive information provided at this stage would allow future mothers to follow appropriate practices in infant feeding knowledgeably. The courses offered to the girls should include the religious significance of breast-feeding, the nutritive value of mature and immature milk and other benefits of breast-feeding to the infant and the mother. Teachers should also hold discussions on factors that contribute to successful lactation, ways of overcoming breast-feeding problems and the techniques of proper feeding. The courses would be beneficial if complemented with practical cooking sessions on foods for weaning including traditional infant meals. Opportunities for interaction with community mothers who are inclined towards breast-feeding would certainly inject more enthusiasm and effectiveness into the learning process.

Another important consideration should be the attitude of teachers who can influence students’ views17 . Teachers with negative or ambivalent attitudes towards breast-feeding would be unlikely to promote it to their wards. Ideally, an instructor who has successfully breast-fed and cared for her own children efficiently would be the best person to deliver the message.

To promote breast-feeding in Saudi Arabia, other strategies too, need to be adopted. These should include the banning of sales promotion or advertisement of infant formulae to the public. Working mothers should be provided with facilities to breast-feed their infants at work, and be permitted short breaks during working hours for this. Educational programmes on the subject of breast-feeding through the mass media, particularly television which reaches most of the population should be encouraged. Many hospitals in the Kingdom need to be “baby friendly” by adopting the new code of practice set out in “Ten steps to Successful Breast-feeding” drawn up recently by the World Health Organization and the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund in 19914. Some institutions continue to keep their newborn in separate rooms and customarily advocate a bottle of infant formula soon after birth. The role of health personnel in the health services remains vital in counselling on breast-feeding as well as rendering support in handling minor problems and difficulties. At present, however, with a large expatriate health staff in the country18, the social and communication gulf often prevents effective health education. Sporadic health talks are conducted in health centers and some government schools by the few Saudi staff available. It is hoped that the situation will improve as more trained Saudi female workers become available for the health services. While these personnel could act as message reinforcers, the task of training future mothers in child nutrition, among other things, remains an essential responsibility of the school educational programme.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author thanks the fourth year medical students of Family and Community Medicine field course 1990 who helped in the collection of the data. Sincere appreciation also goes to the Directorate of Female Education, Dammam, the teachers and students of Saudi Government schools for their kind co-operation in making this study possible.

REFERENCES

- 1.Omer MIA, Suliman GI, Mohamed KA, El-Mufti AR, Zahir K, Hofvander Y, et al. Breast feeding and weaning in the Sudan.Contemporary patterns and influencing factors. J Trop Ped. 1987;33:2–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AI-Sekait MA. A study of factors influencing breast-feeding patterns in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 1988;9:596–601. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowdhary MAKA Infant feeding practices and immunization in the Khamis Mushayt Area. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 1989;9:19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The state of the world's children. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. UNICEF; pp. 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawson M. Infant feeding habits in Riyadh. Saudi Medical Journal. 1981;2(Suppl 1):26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haque KN. Feeding ‘pattern of children under two years of age in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1983;3:129–132. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1983.11748283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman J, Farrag OA, Chatterjee TK, Rahman MS, Suleiman A. Pattern of infant feeding in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. In: Al-Freihi, Rehan T, Al-Mouzan ME, Ashoor AA, Ballal S, Wosornu L, et al., editors. Proceedings of the seventh Saudi Medical Meeting. Dammam: King Faisal University; 1982. pp. 7–411. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sebai ZA. A case study of primary health care. Jeddah: Tihama publications; 1981. The health of the family in a changing Arabia; pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCann MF, Liskin LS, Piotrow PT, Rinehart W, Fox G. Breast-feeding, fertility and family planning. Pop Rep j. 1981;9:525–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jelliffe DB. Infant nutrition in the subtropics and tropics. 2nd edn. Geneva: WHO; 1968. p. 39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdulla MA, Sebai ZA, Swailem AR. Health and nutritional status in preschool children. In Monograph III. The health status of children. Saudi Medical Journal. 1982;3(Suppl 2):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serenius F, Fougerouse D. Health and nutritional status of rural Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 1981;2(Suppl 1):10–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akajii W. Infant feeding habits in Benin city, Nigeria. Trop Doc. 1980;10:29–31. doi: 10.1177/004947558001000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marin PC, Undurraga P. Promotion of breast-feeding in Chile. Saudi Medical Journal. 1981;2(Suppl 1):30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osinusi K. A study of the pattern of breast-feeding in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;90:325–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochbaum GM. Some select aspect of school health education. Health education. 1978;9:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Psiaki DL, Olson CM. Design and evaluation of breast-feeding material for medical students. J Trop Ped. 1982;28:85–87. doi: 10.1093/tropej/28.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sebai ZA. Health in Saudi Arabia. Vol. 2. Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz City For Science and Technology; 1987. p. 153. [Google Scholar]