Abstract

Amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides and their metal-associated aggregated states have been implicated in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Although the etiology of AD remains uncertain, understanding the role of metal-Aβ species could provide insights into the onset and development of the disease. To unravel this, bifunctional small molecules that can specifically target and modulate metal-Aβ species have been developed, which could serve as suitable chemical tools for investigating metal-Aβ-associated events in AD. Through a rational structure-based design principle involving the incorporation of a metal binding site into the structures of Aβ interacting molecules, we devised stilbene derivatives (L1-a and L1-b) and demonstrated their reactivity toward metal-Aβ species. In particular, the dual functions of compounds with different structural features (e.g., with or without a dimethylamino group) were explored by UV-vis, X-ray crystallography, high-resolution 2D NMR, and docking studies. Enhanced bifunctionality of compounds provided greater effects on metal-induced Aβ aggregation and neurotoxicity in vitro and in living cells. Mechanistic investigations of the reaction of L1-a and L1-b with Zn2+-Aβ species by UV-vis and 2D NMR suggest that metal chelation with ligand and/or metal-ligand interaction with the Aβ peptide may be driving factors for the observed modulation of metal-Aβ aggregation pathways. Overall, the studies presented herein demonstrate the importance of a structure-interaction-reactivity relationship for designing small molecules to target metal-Aβ species allowing for the modulation of metal-induced Aβ reactivity and neurotoxicity.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a serious form of dementia that causes deterioration of cognitive function in over 5.3 million people in the United States.1,2 One current hypothesis of the underlying causes of AD involves the accumulation of plaques composed of aggregated amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides in the brain.2-5 Cleavage of the transmembrane amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretases results in the production of Aβ, which contains 38 – 43 amino acid residues. Through hydrophobic interactions, Aβ monomers in solution can self-assemble to form aggregated states (e.g., oligomers, protofibrils, and fibrils).2,5-7 While the fibril-containing plaques can be identified in the brain of AD patients, how these peptides and their possible aggregation states are connected to AD is not completely understood. Current evidence suggests that Aβ monomers are relatively non-toxic while aggregated Aβ species (in particular, soluble low molecular weight (MW) Aβ species, including dimers) are shown to be toxic to neuronal cells and therefore may lead to AD neuropathogenesis; however, their relation to AD development remains obscure.2-4,6

In Aβ plaques, concentrated areas of metal ions such as Fe, Cu, and Zn have been observed.5,8-15 These metal ions are known to facilitate Aβ aggregation upon binding to the Aβ peptide (via three histidine residues, H6, H13, and H14).5,10,11,13-20 Additionally, reactive oxygen species (ROS) can be generated by the redox cycling of Cu bound to Aβ, which may be responsible for the neurotoxicity of the disease.2,10-17,21-25 These characteristics indicate that metal ions are able to influence pathways of Aβ aggregation and neurotoxicity, but the molecular mechanisms of metal-Aβ-associated events are not fully understood.

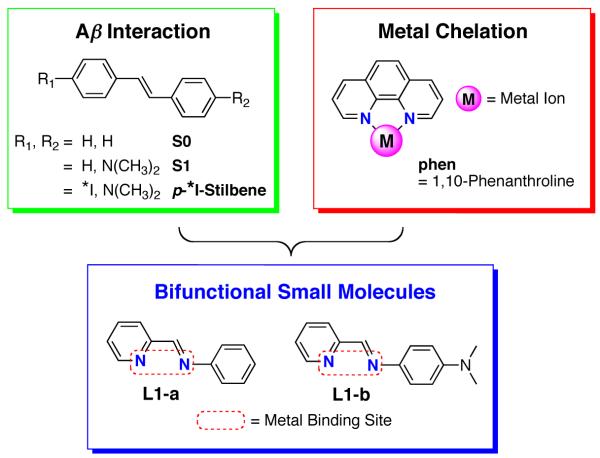

Previous studies have shown that metal chelators such as 2,2′,2″,2′″-(ethane-1,2-diyldinitrilo)tetraacetic acid (EDTA), bathocuproine, desferrioxamine, and clioquinol (CQ) are capable of reducing metal-mediated Aβ aggregation and neurotoxicity. 2,10-12,15-17,21,22,24-32 Use of these metal chelating agents to understand the details of metal-Aβ chemistry and biology is limited because they may not be specific for metal-Aβ species in vivo. This may be due to the lack of Aβ interaction functionality that could hinder metal chelators from targeting metal ions associated with Aβ species in heterogeneous environments. There have been recent efforts to rationally design small molecules that can target metal-Aβ species and modulate their aggregation pathways by appending metal chelation sites onto known Aβ imaging agents.5,15,33-39 Some of these compounds have truncated Aβ-interaction moieties and/or non-specific metal binding properties, which might hamper their capability to target and interact specifically with metal-Aβ species in vitro and in vivo.35,36 To improve this, we have constructed bifunctional small molecules via the direct incorporation of a metal binding site into the scaffold of previously reported Aβ interacting molecules without major structural modification (the rational structure-based design).33,34,37-39 Our first-generation compound (L1-b) was devised by applying this synthetic design strategy employing the structure of an Aβ imaging agent, p-123/125I-stilbene (Figure 1).37 Our small molecule showed bifunctionality (metal chelation and Aβ interaction) as well as control of Cu2+-induced Aβ aggregation processes and neurotoxicity in vitro and in living cells.38 In addition, our recent studies using other bifunctional small molecules suggest that chemical structural moieties such as the dimethylamino functionality are important to tune their reactivity toward metal-induced Aβ aggregation and neurotoxicity.38 In order to understand a structure-interaction-reactivity relationship of the stilbene framework, we report herein the studies of metal binding and Aβ interaction of L1-a (the compound that does not contain a dimethylamino group, Figure 1) and L1-b, the effects on the control of metal (Cu2+ or Zn2+)-mediated Aβ aggregation and Cu-Aβ-induced ROS production in vitro, as well as the influence on metal-Aβ neurotoxicity in living cells. Furthermore, Aβ interaction of L1-a and L1-b was compared to that of S0 and S1 that have the stilbene scaffold without a metal coordination site (a structure-interaction relationship). Our current findings demonstrate that slight difference in chemical structures of small molecules is able to influence their Aβ interaction, which can improve reactivity toward metal-Aβ species.

Figure 1.

The rational structure-based design strategy for bifunctional small molecules. Incorporation of a metal binding site into an Aβ interacting molecule is the design basis for L1-a and L1-b. L1-a = N-(pyridin-2-ylmethylene)aniline; L1-b = N1,N1-dimethyl-N4-(pyridin-2-ylmethylene)benzene-1,4-diamine; S0 = (E)-1,2-diphenylethene; S1 = N,N-dimethyl-4-(2-phenylethenyl)-benzamine. *I = 123I or 125I.

Experimental

Section Materials and Procedures

All reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used as received unless stated otherwise. The compound L1-b was synthesized by the previous method.37 Aβ1-40 peptide was purchased from EZBiolab (Carmel, IN) or rPeptide (Athens, GA). The amino acid sequence for the Aβ1-40 peptide is DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQKLVFFAEDVGSNKGAIIGLMVGGVV. The hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) assay using horseradish peroxidase (HRP, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and Amplex Red (AnaSpec, Inc.,Fremont, CA) was performed following previously published procedures.23,32,37,38,40 The metal ion selectivity of L1-b was determined in EtOH with metal chloride salts (MgCl2, CaCl2, MnCl2, FeCl2, FeCl3, CoCl2, NiCl2, and ZnCl2) using UV-vis according to the previously published report.38 All stock solutions of metal salts were prepared in EtOH. Studies employing FeCl2 were conducted anaerobically. The selectivity values (AM/ACu, Figure S2) were obtained by comparing the absorbance of the solution at 525 nm before and after the addition of CuCl2. Absorption values were normalized relative to that of L1-b and CuCl2 at this wavelength (525 nm) to provide minimal interference between absorption bands. NMR and IR spectra of small molecules were recorded on a 400 MHz Varian NMR spectrometer and on a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum BX FT-IR instrument, respectively. The NMR investigations of the interaction of compounds with Aβ were conducted using a 900 MHz Bruker Avance spectrometer (Michigan State University). Optical spectra were collected on an Agilent 8453 UV-visible spectrophotometer. Mass spectrometric measurements were performed using a Micromass LCT Electrospray Time-of-Flight mass spectrometer. A SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices) was used for measurements of absorbance for the cell viability assay and fluorescence for the H2O2 assay.

[Zn(L1-a)Cl2]

Colorless plate crystals were grown by vapor diffusion of diethyl ether (Et2O) into an acetonitrile (CH3CN) solution of commercially available L1-a (5.0 mg, 27 μmol) and ZnCl2 (3.7 mg, 27 μmol) at room temperature over 2 days. The crystals were isolated, washed with Et2O three times, and dried in vacuo (7.1 mg, 22 μmol, 81%). FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3445 (w, br), 3086 (vw, sh), 3085 (vw), 3064 (w), 3024 (w), 1620 (vw, sh), 1594 (s), 1563 (w), 1494 (s), 1476 (m, sh), 1456 (m, sh), 1445 (s), 1421 (vw, sh), 1385 (vw, sh), 1368 (m), 1339 (vw), 1303 (w), 1280 (w), 1236 (w), 1195 (w), 1186 (vw, sh), 1158 (w), 1111 (m), 1076 (vw), 1050 (w), 1024 (s), 1000 (vw, sh), 976 (w), 959 (w), 916 (m), 840 (vw), 778 (vs), 740 (s), 684 (s), 650 (m), 616 (vw, sh), 567 (w), 535 (m), 481 (vw), 462 (vw, sh), 413 (w). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN): δ = 7.54 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.94 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.85 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 9.03 (s, 1H). ESI(+)MS (m/z): [M-Cl]+ calcd for C12H10ClN2Zn, 281.0, found 280.9. Anal. Calcd for C12H10Cl2N2Zn: C, 45.25; H, 3.16; N, 8.80. Found: C, 45.24; H, 3.17; N, 8.70. UV-vis [CH3CN; λ/nm (ε × 104, M−1cm−1)]: 235 (1.1), 241 (1.2), 328 (1.9), 341 (1.8).

[Zn(L1-b)Cl2]

Orange needle crystals were grown by vapor diffusion of Et2O into a CH3CN solution of L1-b (5.0 mg, 22 μmol) and ZnCl2 (3.0 mg, 22 μmol) at room temperature overnight. The crystals were isolated, washed with Et2O three times, and dried in vacuo (6.8 mg, 19 μmol, 86%). FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3440 (w, br), 3077 (vw), 3027 (vw), 3008 (vw), 2974 (vw), 2902 (w), 2863 (vw, sh), 2822 (vw), 1622 (s), 1599 (vs), 1583 (s, sh), 1546 (vs), 1471 (s), 1447 (s), 1415 (vw, sh), 1371 (s), 1328 (vw), 1321 (vw), 1300 (w), 1284 (w), 1250 (w), 1231 (w), 1215 (vw, sh), 1188 (s), 1173 (s), 1159 (s, sh), 1123 (vw, sh), 1105 (vw), 1067 (w), 1050 (vw), 1024 (vw), 1000 (vw), 946 (w), 923 (vw, sh), 842 (vw, sh), 810 (s), 771 (m), 744 (w), 644 (vw, sh), 642 (w), 551 (vw), 529 (m), 430 (vw), 411 (w). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN): δ = 3.06 (s, 6H), 6.86 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.71 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (t, J = 4 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.75 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H), 8.86 (s, 1H). ESI(+)MS (m/z): [M+H]+ Calcd for C14H16Cl2N3Zn, 360.0, found 360.0. Anal. Calcd for C14H15Cl2N3Zn: C, 46.50; H, 4.18; N, 11.62. Found: C, 46.44; H, 4.14; N, 11.57. UV-vis [CH3CN; λ/nm (ε × 104, M−1cm−1)]: 277 (2.0), 477 (3.3).

X-ray Crystallographic Study

Single crystals suitable for data collection were mounted on a Bruker SMART APEX CCD-based X-ray diffractometer equipped with a low temperature device and fine focus Mo-target X-ray tube (λ = 0.71073 Å) operated at 1500 W power (50 kV, 30 mA). The X-ray intensities were measured at 85(2) K. Empirical absorption corrections were calculated with the SADABS or TWINABS program.41 Structures were solved and refined with the SAINTPLUS and SHELXTL software packages.42,43 All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. Hydrogen atoms were assigned in idealized positions and each was given a thermal parameter equivalent to 1.2 times the thermal parameter of the atom to which it was attached. The structure solution was checked for higher symmetry with PLATON.44 The highest electron density in the final difference Fourier maps for [Zn(L1-a)Cl2] and [Zn(L1-b)Cl2] were 1.181 and 1.112 e/ Å 3, respectively, in the vicinity of the Zn center. In the structure of [Zn(L1-b)Cl2], indexing performed using the CELL_NOW program45 indicated that the crystal was a two-component, non-merohedral twin. The data were processed with TWINABS and corrected for absorption.41 The domains are related by a rotation of 179.8 degrees about the direct and reciprocal [0 1 0] axis. For this refinement, single reflections from component one as well as composite reflections containing a contribution from this component were used. Merging of the data was performed in TWINABS and an HKLF 5 format file was used for refinement.

Two-Dimensional (2D) 1H-15N Transverse Relaxation Optimized Spectroscopy (TROSY)-Heteronuclear Single Quantum Correlation (HSQC) NMR Measurements

The 15N-labeled Aβ1-40 was purchased from rPeptide and stored at −80 °C. Aβ (ca. 0.25 mg) was dissolved into a buffered solution containing sodium dodecyl-d25 sulfate (SDS-d25, 200 mM), sodium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.3), and D2O (7%, v/v) and was briefly vortexed.37-39 The peptide solution was transferred to a Shigemi NMR tube. After acquiring spectra of the peptide, ca. 10 equivalents (stock solutions: 5 mM in above buffer solution) of either L1-a or L1-b were added to the NMR samples of Aβ (ca. 190 μM Aβ). Control samples were conducted under similar conditions with the addition of 2.28 μL of either neat dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 (DMSO-d6) or a 50 mM DMSO-d6 stock solution of S0 or S1 to a 300 μL solution containing 190 μM Aβ.46 For NMR studies with Zn2+, ca. 1.0 equivalent of ZnCl2 (0.57 μL of 100 mM stock solution in D2O) was added into the peptide solution followed by treatment with 10 equivalents of L1-a or L1-b. For the [Aβ + ZnCl2 + L1-a or L1-b] solution, no further spectral changes were observed after 1 h of incubation. For NMR studies, the TROSY version of 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra were recorded on the 900 MHz Bruker Avance NMR spectrometer (equipped with a TCI cryoprobe accessory) with 14.3 kHz and 1.7 kHz spectral width and 2048 and 128 complex data points in the 1H and 15N dimension, respectively, 4 scans for each t1 experiment and 1.5 s recycle delay; each spectrum took 10 min for completion. The water 1H peak was referenced to 4.78 ppm at 25 °C. 1H-15N HSQC peaks were assigned by comparison of the observed chemical shift values with those reported in the literature.47 Combined 1H and 15N 2D chemicals shifts (ΔδN-H) were calculated from equation 1.48-50 The 2D results were processed using Topspin software (version 2.1 from Bruker) and analyzed with Sparky (version 3.112).

| (eq 1) |

Docking Studies of Compounds with AutoDock4

Docking of L1-a, L1-b, S0, and S1 with the Aβ monomer was determined using the computational package AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4 following previous reports.38,51-53 The optimized structures of compounds were generated for AutoDockTools4 by the MMFF94 energy minimization in ChemBio3D Ultra 12.0. Ten peptide conformations from a previously determined NMR structure of Aβ1-40 monomer in SDS micelles (PDB 1BA4) were employed.54 Of these conformations, five were in agreement with the NMR data and are depicted in Figures 4 and S4. The structural files of compounds and peptides were transferred to AutoDockTools4 and prepared for AutoGrid4 using a grid volume encompassing the entire peptide with 0.375 Å spacing: [Conformation: box size ( Å ): center (x,y,z)] A: 126 × 84 × 56: 7.663, 7.889, −8.706; B: 126 × 72 × 66: 0.194, −6.01, −7.711; C: 126 × 72 × 58: 5.665, −5.79, −8.124; D: 126 × 72 × 76: 5.432, −4.614, −12.983; E: 118 × 88 × 54: 10.202, 9.338, −4.058. In AutoDock4, each compound was evaluated with 256 Lamarckian genetic algorithm local searches (GALS) by a population size of 150 and 2.5 million energy evaluations. Additional default parameters remained unchanged unless otherwise specified. Conformations of compounds were analyzed by clusters in AutoDockTools4. The highest frequency and lowest energy conformation was chosen and portrayed docked to Aβ using Pymol.

Figure 4.

Possible conformations of L1-a (light blue), L1-b (yellow), S0 (orange), and S1 (magenta) docked with Aβ1-40 (PDB 1BA4) by AutoDock4. The cartoon (left) and surface (right) versions of the peptide indicate interactions with compounds. The N-terminal and inner helix regions of Aβ (D1 – N27) are highlighted in color. Hydrogen bonding is indicated with dashed lines (1.9 – 2.2 Å).

Amyloid-β (Aβ) Peptide Experiments

Aβ1-40 peptide (1 mg, EZBiolab) was purchased, dissolved with ammonium hydroxide (1% v/v, aq), aliquoted to 10 samples, lyophilized, and stored at −80 °C. The stock solution (ca. 200 μM) for the reactions was made by redissolving Aβ with NH4OH (1% v/v, aq, 10 μL) followed by dilution with ddH2O or a buffer solution. Preparation of all Aβ samples followed the previously reported procedures.37-39,55-58 The ddH2O and buffer solutions used for Aβ experiments were treated with Chelex to remove traces of metal ions. For the inhibition study, solutions of samples contained Aβ (25 μM), a metal salt (CuCl2 or ZnCl2, 25 μM), and a compound (50 μM, stock solutions in DMSO, 1% v/v final DMSO concentration). The solutions were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with constant agitation and analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and Western blotting using an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10). For the disaggregation study, Aβ (25 μM) and a metal salt (CuCl2 or ZnCl2, 25 μM) were incubated for 24 h at 37 ° C with constant agitation. Afterwards, a compound (50 μM, stock solutions in DMSO, 1% v/v final DMSO concentration) was added and incubated for 24 h at 37 ° C with constant agitation. Buffered solutions (20 μM HEPES (2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]ethanesulfonic acid), pH 6.6 (for CuCl2) or pH 7.4 (for ZnCl2), 150 μM NaCl) were used for both studies.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Samples for TEM were prepared by following the previously reported methods.37-39,55-58 Glow-discharged grids (Formar/Carbon 300-mesh, Electron Microscopy Sciences) were treated with Aβ aggregated samples (5 μL, 25 μM) for 2 min at room temperature. Excess samples were removed using filter paper followed by washing twice with ddH2O. Each grid incubated with uranyl acetate (1%, ddH2O, 5 μL, 1 min) was blotted and dried for 15 min at room temperature. Images from each sample were taken by a Philips CM-100 transmission electron microscope (80 kV, 25,000× magnification).

Native Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blotting

The reactions described above (Aβ Peptide Experiments) were visualized by native gel electrophoresis followed by Western blotting using an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10).37-39,57,58 Each sample (10 μL, 25 μM) was separated on a 10 – 20% gradient Tristricine gel (Invitrogen). The gel was transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA, 3% w/v) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 3 h at ambient temperature, and then incubated with an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10, 1:2,000) in 2% BSA in TBS-T for 3 h at ambient temperature. The membrane was probed with the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:10,000) in 2% BSA in TBS-T for 1 h at ambient temperature. The Thermo Scientific Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate was used to visualize protein bands.

Cytotoxicity (MTT Assay)

Two human neuroblastoma SK-N-BE(2)-M17 (M17) and SK-N-AS (AS) cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The M17 and AS cell lines were maintained in ([1:1 Minimum Essential Media (MEM) and Ham’s F12K Kaighn’s Modification Media (F12K)] and [Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)], GIBCO), respectively, containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cells were grown at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. For the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, Sigma-Aldrich) assay, M17/AS cells were seeded in a 96 well plate (for cytotoxicity studies of compounds without and with metal ions, 16,000/8,000 and 10,000/5,000 cells (in 100 μL per well) for 24 and 72 h experiments, respectively; for the investigations of regulating metal-Aβ neurotoxicity by compounds, 16,000 M17 cells (in 100 μL per well)).37,38,58 After 24 h, cells were treated with [compounds with or without metal ions] and [Aβ, CuCl2 or ZnCl2, and/or compounds]. Then, the cells were incubated for 24 or 72 h at 37 °C. After the incubation, the cells were treated with 25 μL MTT (5 mg/mL in PBS) for 4 h at 37 °C and then were lysed in a buffered solution containing N,N-dimethylformamide (pH 4.5, 50% (aq, v/v)) and SDS (20% (w/v)) overnight at room temperature in the dark. The absorbance (A600) was measured using a microplate reader.

Results and Discussion

Design Consideration and Preparation of Bifunctional Small Molecules for Targeting and Modulating Metal-Aβ Species

In order to elucidate the mechanisms of metal-induced Aβ aggregation and neurotoxicity in AD, chemical tools that can specifically target and regulate metal-Aβ species are needed. We have designed bifunctional chemical reagents that contain a metal binding site in the structure of Aβ interaction molecules.33,34,37-39 In particular, we have focused on the incorporation of a metal chelation moiety into the stilbene framework (Aβ imaging agent) for bifunctionality (metal chelation and Aβ interaction) (Figure 1).

Recently, we reported that L1-b, in which two nitrogen donor atoms were introduced into the stilbene scaffold for metal binding (Figure 1), exhibited bifunctionality and its ability to modulate Cu2+-induced Aβ events such as aggregation and neurotoxicity in vitro and in living cells.37 Moreover, amine derivatives of L1-a and L1-b have been prepared for this purpose indicating promising applications in biological systems.38 From this and other studies, the dimethylamino functionality in the small molecules has been suggested to be an important structural moiety for Aβ interaction.38,59,60 In order to understand the structure-interaction-reactivity relationship, L1-a (that does not have a dimethylamino group) was studied along with L1-b (vide infra). The compounds L1-a (commercially available) and L1-b can be synthesized in high yield (> 90%) through Schiff base condensation of an aldehyde and primary amine following previously established methods.37,61

Metal Binding Properties of L1-a and L1-b

Following our rational structure-based design principle, two nitrogen atom donors were introduced into the stilbene framework to generate a metal chelation site (Figure 1). In order to elucidate metal binding properties of our compounds, the reactions of the compounds with metal chloride salts in solution were evaluated using UV-vis and the metal complexes [Zn(L1-a)Cl2] and [Zn(L1-b)Cl2] were isolated and characterized by X-ray crystallography. First, metal coordination was observed by the shifts in the optical bands of our compounds upon addition of CuCl2 or ZnCl2 in EtOH (Table 1 and Figure S1). Modest changes in the absorption spectra were shown for L1-a with 1 equivalent of CuCl2 or ZnCl2 whereas both metal chloride salts caused noticeable changes in the spectra of L1-b. The ligand L1-b interacted with Cu2+ based on the new absorption bands at ca. 450 nm. The observed peaks from 470 – 480 nm that grew in upon the addition of ZnCl2 indicated that L1-b could bind to Zn2+ as well. Furthermore, L1-b having the dimethylamino group presented more apparent changes in the optical spectra in the presence of metal chloride salts, compared to L1-a (Table 1 and Figure S1). The optical features, indicative of the Zn2+-L1-a or Zn2+-L1-b interaction, was also shown in the solution of isolated metal complexes [Zn(L1-a)Cl2] or [Zn(L1-b)Cl2] (Figure 2, vide infra) in CH3CN (Table 1 and Figure S1). Thus, UV-vis studies described above suggest metal binding of L1-a and L1-b in solution. Additionally, the investigation for the metal selectivity of L1-b using UV-vis indicated that this ligand was relatively selective for Cu2+ over other metal ions such as Mg2+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+ in EtOH (Figure S2; [L1-b] = 40 μM, [M2+/3+] = 40 μM, at room temperature). Due to the limited stability of these imine compounds in aqueous solutions,62 further metal binding properties such as pH-variable solution speciation36,38 were not studied.

Table 1.

Summary of Optical Resultsa

| Spectral Properties (nm) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Unboundb | CuCl2b | ZnCl2b | Crystalsc |

| L1-a | 280, 323 | 297 | 283, 325 |

[Zn(L1-a)Cl2] 235, 241, 328, 341 |

| L1-b | 316, 396 | 318, 445 | 403, 484 408,d 473d |

[Zn(L1-b)Cl2] 277, 475 |

The optical spectra are depicted in Figure S1.

Measurements were performed in EtOH at room temperature following 10 min incubation. Ratio of metal to ligand was 1:1 unless otherwise noted.

Optical data were obtained in CH3CN.

[ZnCl2]/[L1-b] = 10:1.

Figure 2.

ORTEP diagrams of [Zn(L1-a)Cl2] (left) and [Zn(L1-b)Cl2] (right) showing 50% probability thermal ellipsoids. X-ray crystallographic data are summarized in Table S1.

To further understand the metal binding properties, X-ray quality single crystals of the metal complexes [Zn(L1-a)Cl2] and [Zn(L1-b)Cl2] (Figure 2) were grown by slow diffusion of Et2O into a solution of ligand and ZnCl2 (1:1) in CH3CN. Crystallographic data and selected bond lengths and angles are summarized in Tables S1 and 2, respectively. As depicted in Figure 2, the structures present that two nitrogen atoms of the ligands are responsible for metal chelation. The overall conformation of the imine ligands L1-a and L1-b of the Zn complexes exhibited planarity in the solid state, with distorted tetrahedral geometry around the metal center. The bond lengths and angles for the Zn complexes did not vary significantly depending on the presence of the dimethylamino group; however, the slight difference in bond angles and the Zn-N1 bond length between [Zn(L1-a)Cl2] and [Zn(L1-b)Cl2] was indicated (Table 2; e.g., Zn-N1 (Å) = 2.060(2) versus 2.0446(17), respectively). A Zn2+ complex with a structure similar to L1-b where the dimethylamino group is substituted with an iodine atom has been reported.63 The molecule binds to ZnCl2 in a 1:1 ratio to form a slightly distorted tetrahedral metal center with bond lengths and angles that are similar to those of [Zn(L1-a)Cl2] and [Zn(L1-b)Cl2]. This suggests that neither an electron withdrawing nor electron donating substituent in the para position of the phenyl ring significantly alters bond lengths or angles. Overall, X-ray crystal structure determination confirmed metal chelation by L1-a and L1-b via two nitrogen donor atoms.

Table 2.

Selected Bond Lengths (Å) and Angles (deg).a

| [Zn(L1-a)Cl2] | [Zn(L1-b)Cl2] | |

|---|---|---|

| Zn1-N1 | 2.060(2) | 2.0446(17) |

| Zn1-N2 | 2.081(2) | 2.0828(18) |

| Zn1-Cl1 | 2.2280(6) | 2.2162(8) |

| Zn1-Cl2 | 2.1998(6) | 2.2056(8) |

| N1-Zn1-N2 | 81.20(8) | 82.24(7) |

| N1-Zn1-Cl1 | 107.72(6) | 110.16(6) |

| N1-Zn1-Cl2 | 119.14(6) | 117.42(6) |

| N2-Zn1-Cl1 | 111.40(6) | 110.06(5) |

| N2-Zn1-Cl2 | 117.10(6) | 120.03(6) |

| Cl1-Zn1-Cl2 | 115.48(2) | 113.18(2) |

Numbers in parentheses are estimated standard deviations in the last significant figures. Atoms are labeled as indicated in Figure 2.

Aβ Interaction with L1-a, L1-b, S0, and S1

To establish the extent of interaction of L1-a and L1-b with Aβ in the absence of metal ions, which along with metal chelation affords bifunctionality, high-resolution 2D 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC NMR experiments were performed. SDS-d25 was employed in NMR studies of Aβ in order to solubilize the peptide and prevent its aggregation.37-39,47,54,64 When bound to SDS micelles, the Aβ monomer adopts two α-helical segments involving residues Q15 – N27 and G29 – M35.47,54 Helicity has also been observed in solution and when in contact with other biological molecules and has been suggested to precede the aggregation pathways of Aβ leading to proposed neurotoxic oligomers.4,6,65-68 Thus, this system can provide an adquate model for determining the ability of our compounds to interact with and target a biologically relevant Aβ conformation. As a comparison of the interaction of our bifunctional molecules with Aβ, S0 and S1 that do not contain a metal binding site (Figure 1) were additionally investigated.

Changes in chemical shifts of Aβ were observed upon the addition of L1-a and L1-b (Figure 3, ca. 10 equivalents, SDS-d25 (200 mM), sodium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.3), and D2O (7%, v/v)), suggesting direct Aβ interaction with our small molecules. This experiment was carried out in the absence of DMSO, which is different from the previous report regarding the interaction of L1-b with Aβ monomer.37 Both compounds exerted an influence mainly on the N-terminal portion of the peptide (E3 – Q15) where shifting occurred the most at residues E11 and H13. To understand the effect of the dimethylamino functionality on Aβ interaction (L1-a versus L1-b), the chemical shift patterns were compared. While L1-b interacted more broadly through the N-terminal region and also with the inner helix of the peptide (Q15 – N27), L1-a had fewer contacts in these portions of the peptide and did not show as strong of an interaction (Figure 3). For L1-b, a periodic trend occurred along the peptide backbone (Figure 3b), similar to our recently reported heterocyclic bifunctional IMPY derivative.39 The shifting of residues Q15, V18, and E22 suggest that these residues may lie on a similar face of the inner helix (Q15 – N27 depicted in Figure 4) and shift due to direct interaction with compound or a change in conformation upon ligand binding.6,47,54 The absence of the dimethylamino structural moiety in L1-a, which has been proposed to be important in Aβ interaction,38,59,60 may explain why its degree of interaction with Aβ is less than that of L1-b. Furthermore, the observation that the residues E11 and H13 were significantly shifted by our bifunctional molecules is important because these residues are near the proposed metal binding site of Aβ (H6, H13, and H14). 10,11,13-15,18-20,22,40 Due to the close proximity of our compounds to the metal binding residues, it is possible that L1-a and L1-b may be able to target metal ions surrounded by Aβ peptides.

Figure 3.

2D 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC NMR studies of small molecules with 15N-labeled Aβ1-40 (900 MHz). (a) NMR spectra of the Aβ peptide (shown in black; ca. 308 μM in SDS-d25 (200 mM), sodium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.3, 7% D2O (v/v), 25 °C) and the peptide with the addition of 10 equivalents of L1-a or L1-b shown in blue (full spectrum of L1-b is shown on the left). Green arrows indicate direction of signal shifting. (b) Changes in combined 1H and 15N chemical shifts calculated from eq 1 upon the addition of 10 equivalents of compounds to Aβ as a function of peptide sequence. * Denotes absent or overlapped signals. The amino acid sequence for the Aβ1-40 peptide is DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQKLVFFAEDVGSNKGAIIGLMVGGVV.

To further compare the effect of both the addition of two nitrogen atoms and the presence of the dimethylamino group in our molecules, the compounds without a metal binding site, S0 and S1, were also studied by NMR. Due to the low solubility of S0 and S1 in the buffered conditions above, DMSO was employed to deliver the compounds to the Aβ solution.46 Both compounds and DMSO alone (ca. 2 equivalents of compound) appeared to have an influence on the shifting of residues but shifting trends were different from L1-a and L1-b (Figures S3 and 4). Upon addition of both S0 and S1 to the solution of Aβ, residues E11 and H13 did not shift as much as DMSO alone suggesting these compounds may compete for contacts with the peptide although direct comparison is difficult to discern because of the possibility of compounds interacting both with the peptide and/or counteracting the DMSO effect (Figure S3). With the consideration of the DMSO effect on the Aβ monomer, S0 and S1 did not show the same ability to recognize Aβ under these conditions as compared to the bifunctional compounds L1-a and L1-b. Contrasting L1-a and L1-b from S0 and S1, the dimethylamino functionality may not be solely responsible for interaction within this molecular scaffold. The combination of placing two nitrogen atoms into the stilbene framework with the dimethylamino group revealed that minor changes in chemical structure might better control Aβ interaction via hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic contacts. From the compounds investigated, the choice of molecular scaffold and functionality are important variables in selecting effective Aβ interacting molecules to be used as a basis for rational structure-based design. Overall, along with metal binding studies, our NMR investigations above suggest that the bifunctional stilbene derivatives can interact with both metal ions and Aβ demonstrating their bifunctionality.

Docking Studies of L1-a, L1-b, S0, and S1 with Aβ

While the residue-specific influence of our compounds (L1-a and L1-b) on the Aβ monomer was determined by 2D NMR spectroscopy, visualization of the structural details of their contact modes with the peptide backbone or residue side chains would provide more insights into the structure-interaction relationship between small molecules and the peptide. To consider possible conformations of our compounds with Aβ, docking studies were conducted using AutoDock4.38,51-53 A previously determined solution NMR structure of Aβ1-40 in SDS micelles (PDB 1BA4) was chosen and the molecules were evaluated with ten conformations of Aβ.54 Among them, five conformations of Aβ docked with L1-a and L1-b were consistent with our NMR results. Based on the lowest energy clusters with highest occurrence, the conformations of compounds with Aβ were selected (Table S2).

In agreement with NMR observations discussed above, the overall docking results suggested that our bifunctional small molecules may contact the N-terminal region and inner helix of the peptide near the proposed metal binding site (Figures 4 and S4).47,54 Most of the conformations presented that the compounds were oriented closer to the hydrophilic metal binding region while one conformation showed ligands docked near the hydrophobic inner helix (conformation C, Figure S4). The docking results for L1-a and L1-b illustrated similar binding in three of the conformations analyzed, suggesting that these molecules may behave similarly with common hydrogen bonding contacts with the peptide backbone and side chain residues. Along with hydrogen bonding interaction, positioning of the dimethylamino group of L1-b either towards the hydrophilic N-terminal region or the hydrophobic helical region revealed various amphiphilic contacts with the peptide potentially accounting for the greater chemical shift changes exhibited in the NMR experiment. For S0 and S1, interactions were indicated in the hydrophilic turn and along the inner helix of the peptide as well. More variation between these two molecules (S0/S1) was observed in the different conformations tested although some conformations showed similar binding modes of these compounds as were seen for L1-a and L1-b (Figures 4 and S4).

Different orientations of L1-a, L1-b, S0, and S1 were visible in the docking investigations, with general interaction near the turn of the peptide (near the metal binding site and inner helix) indicating the utility of the stilbene framework for recognizing the Aβ peptide (Figures 4 and S4). The individual differences between the ligands docked to the Aβ conformations displayed several possible contacts that may exist in solution, such as hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic contacts that along with NMR imply more favorable interaction of L1-a and L1-b over S0 and S1 with the Aβ peptide. Therefore, these docking results give further support for direct Aβ interaction of our bifunctional small molecules in addition to the NMR investigations.

Effect of L1-a and L1-b on Metal-Induced Aβ Aggregation

The regulation of L1-a and L1-b on metal-associated Aβ aggregation processes was investigated by TEM and native gel electrophoresis followed by Western blotting using anti-Aβ antibody 6E10.37-39,55-58 Both inhibition and disaggregation studies were carried out (forward and backward reactions as shown in Figures 5 and S5). For inhibition experiments, fresh Aβ (25 μM) and CuCl2 or ZnCl2 (25 μM) were treated with the compounds (50 μM) for 24 h (Figures 5 and S5a). In the disaggregation experiments, the samples containing Aβ and metal chloride salts were incubated for 24 h to allow Aβ aggregates to form, and then agitated with each compound for 24 h (Figures 5 and S5a).

Figure 5.

Control of Zn2+-induced Aβ aggregation by small molecules. Top: Scheme of the inhibition and disaggregation experiments. Bottom: TEM images of samples (a) from the inhibition experiment [fresh Aβ treated with ZnCl2 followed by incubation with the compounds (L1-a and L1-b)]; (b) from the disaggregation experiment [Zn2+-induced Aβ aggregates by 24 h incubation and subsequent 24 h treatment with L1-a or L1-b]. (c) Results of (a) visualized by native gel electrophoresis followed by Western blot (anti-Aβ antibody 6E10): (1) [Aβ + ZnCl2]; (2) [1 + L1-a]; (3) [1 + L1-b]. Conditions: [Aβ] = 25 μM, [ZnCl2] = 25 μM, [compound] = 50 μM, pH 7.4, 24 h, 37 °C, constant agitation.

The presence of metal ions (Cu2+ or Zn2+) triggered the formation of large, aggregated Aβ species (Figures 5 and S5a). On the other hand, upon treatment with our compounds, metal-induced Aβ aggregation was noticeably inhibited according to TEM and native gel analysis.37,38,58 As shown in Figure 5, Aβ species that had low MW (≤ 32 kDa) and could enter the gel matrix were visible when our bifunctional compounds were introduced into metal-treated Aβ samples. In particular, much less metal-mediated Aβ aggregation was seen with L1-b over L1-a. Based on our previous report, at the same conditions, the traditional metal chelators CQ, phen (Figure 1), and EDTA resulted in the generation of high MW Aβ aggregates, which was observed by the same methods.37,38 The control molecule (S1) that does not contain a metal binding site did not block metal-induced Aβ aggregation,37,38 suggesting that disruption of metal-Aβ interaction was one of the important parameters to block metal-mediated Aβ aggregation with our bifunctional compounds. In addition, the effect of L1-b on the metal-free Aβ aggregation was studied (Figure S5b). No noticeable control of Aβ aggregation by L1-b was observed under the metal-free condition, implying that the reactivity of L1-b is specific for metal-Aβ species over metal-free Aβ species. Taken together, TEM and Western blot results suggest that the bifunctional molecules could prevent metal-induced Aβ fibrillogenesis generating smaller sized Aβ species more effectively than with traditional metal chelating agents. Therefore, inhibition studies demonstrate that our bifunctional small molecules could function as modulators of metal-induced Aβ aggregate formation, which may support that metal ions could play important roles in Aβ aggregation in AD.

The ability of L1-a and L1-b to disassemble preformed metal-mediated Aβ aggregates was also explored. Both compounds L1-a and L1-b were able to alter the structure of metal-triggered Aβ aggregates affording their disaggregation (Figures 5 and S5).37 Similar to the inhibition study, L1-b provided greater effect toward disaggregation of preformed metal-Aβ aggregates than L1-a. Different from the bifunctional molecules, our previous studies showed that the traditional metal chelators phen and EDTA did not disaggregate preformed metal-associated Aβ aggregates, though changes in morphology were observed.37,38,55 In the case of CQ, partial disaggregation of Zn2+-treated Aβ aggregates was recorded.55 Therefore, based on the results from both inhibition and disaggregation experiments, our bifunctional molecules L1-a and L1-b were better able to control metal-mediated Aβ aggregation processes (formation of metal-induced Aβ aggregates as well as their disaggregation) than the traditional metal chelators. The compound L1-b that indicated greater bifunctionality (vide supra) exhibited more effective control of metal-induced Aβ aggregation, compared to L1-a. These observations imply that the bifunctionality of our compounds leads to enhanced reactivity with metal-Aβ species (structure-interaction-reactivity relationship).

Investigation of the Reaction of Zn2+-Treated Aβ with L1-a and L1-b

To understand possible mechanisms underlying the modulation of metal-triggered Aβ events by our small molecules, spectroscopic investigations were conducted using high-resolution 2D NMR and UV-vis on Zn2+-treated Aβ solutions in the absence and presence of compounds. To first determine the ability of L1-b to compete for Zn2+ binding from Aβ, the compound (40 μM) was added to a solution containing equal concentrations of ZnCl2 and Aβ (20 μM, 200 mM SDS, 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.3). The resulting UV-vis spectrum showed the generation of Zn2+-L1-b species with optical bands near 450 nm, which is comparable to those from only the metal-ligand complex (Figure S6a). Due to the small optical change upon addition of Zn2+ into the solution of L1-a (Figure S1), the UV-vis study of Aβ, Zn2+, and L1-a was not performed. Carrying out 2D TROSY-HSQC experiments under similar conditions suggested that more than simple metal chelation by our small molecules from the peptide may occur. As expected from previous reports, addition of one equivalent of ZnCl2 to an NMR solution of Aβ (308 μM, 200 mM SDS-d25, 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.3, 7% D2O (v/v), 25 °C) caused a large portion of the 2D NMR spectrum to disappear due to line broadening as a result of Zn2+ binding (Figure 6).20,69,70 With the treatment of 10 equivalents of compounds, the 1H and 15N cross peaks absent upon introduction of Zn2+ were recovered with 30 min incubation of L1-a and L1-b (Figure 6). Additionally, cross peak shifts were observed for both L1-a and L1-b that indicated small variations from the metal free samples in the N-terminal and inner helix portions of the peptide (Figures 6 and S6b). These observations suggest that the interaction of these bifunctional molecules with Zn2+-Aβ occurs via a combination of metal chelation by the compound from Aβ and interaction of free compound and/or the metal complex with Aβ.38 Metal chelation was also supported by optical spectra indicating Zn2+ binding to the compound (Figure S6a) as discussed above.

Figure 6.

NMR investigations of L1-a and L1-b interacting with Zn2+-bound Aβ1-40. 2D 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC NMR spectra (900 MHz, 200 mM SDS-d25, 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.3, 7% D2O (v/v), 25 °C) of 15N-labeled Aβ peptide (ca. 308 μM, black) and upon the addition of ZnCl2 (ca. 1 equivalent, red) followed by the addition of 10 equivalents of either L1-a (purple) or L1-b (blue) after 1 h incubation.

Based on reactivity studies of compounds with metal-Aβ species by TEM (vide supra), disruption of both metal-peptide and peptide-peptide interactions could be a driving force for preventing metal-induced Aβ aggregation. From previously reported NMR observations, the traditional metal chelator EDTA was shown to remove Cu2+ or Zn2+ from Aβ;71 but from our previously reported TEM results discussed above, EDTA and other orthodox metal chelators did not deter metal-induced Aβ aggregation.37,38 Our NMR and optical results involving Zn2+-Aβ species and compounds indicated that the observed interference on metal-Aβ reactivity could be due to the removal of the metal ion from metal-Aβ species (through metal chelation by the ligand or ligand-induced metal-Aβ conformational changes) and/or the potential formation of ternary type complexes involving Aβ, Zn2+, and compound (through the interaction of ligand with metal-Aβ species or ligand-metal complexes with the peptide).38 Thus, small variations in the stilbene scaffold could not only affect ligand binding to Aβ but also indicate the ability to tune interactions with metal-Aβ species.

Regulation of Cu-Aβ-Induced ROS Production by L1-a and L1-b

The production of ROS by redox active metal-Aβ species and subsequent oxidative stress may lead to neurotoxicity in AD.2,10-17,21-25 In addition to targeting metal-Aβ species for modulating their aggregation properties, control of ROS formation by our bifunctional small molecules must be considered. Employing the HRP/Amplex Red assay,23,32,37,40 amounts of H2O2 produced by Cu-Aβspecies in the absence and presence of our bifunctional molecules (L1-a and L1-b) was determined. Inhibition of Cu-Aβ-triggered H2O2 formation by L1-a and L1-b was observed (reduction of H2O2 formation by 64(±1.1)% (for L1-a) and 70(±0.75)% (for L1-b)37). Other metal chelating agents CQ and EDTA also exhibited decreased H2O2 production under the same conditions.37,38 In the absence of Aβ, free Cu ions generated ca. 94% of the amount of H2O2 as was produced in the presence of the peptide. The ligands were also able to lower the level of H2O2 generated by peptide-free Cu by ca. 52% for L1-a and 56% for L1-b ([CuCl2]/[ligand] = 1:2), relative to Cu-Aβ. Taken together, the prevention of H2O2 formation by peptide-free or -bound Cu in vitro by our stilbene derivatives was observed, which may suggest their use as ROS regulators.

Cytotoxicity of L1-a and L1-b with and without Metal Chloride Salts as well as Their Ability to Modulate Metal-Aβ Neurotoxicity in Human Neuroblastoma Cells

First, cell viability in the presence of our compounds at various concentrations was evaluated in human neuroblastoma M17 and AS cells after 24 or 72 h incubation. The cell survival rates were monitored by the MTT assay.37,38 After 24 h of incubation with our bifunctional small molecules, no toxic effects were observed in either M17 or AS cells. After 72 h, cytotoxicity of L1-a was not visible up to 100 μM for either cell line. For both cell lines (M17/AS), L1-b (up to 100 μM) showed 66(±3.2)/84(±4.2)% survival, respectively (Figure S7a). Considering the previously studied cell viability of CQ and phen (30(±0.3)/34(±0.8)% and 37(±0.5)/44(±0.2)% in M17 and AS cell lines, respectively),38 toxicity of our compounds may be minimal up to 100 μM. Furthermore, the cytotoxicity of L1-a and L1-b with CuCl2 or ZnCl2 (5 – 120 μM) at 1:1 and 1:2 metal/compound ratios for 24 h was examined in the M17 cell line. Cell survival (ca. 96 – 100%) was observed from cells treated with up to 20 μM CuCl2 or ZnCl2 and 20/40 μM compounds (Figures S7b and S7c). Above 40 μM metal chloride salt and 40/80 μM compounds, the cell viability decreased. When CuCl2 or ZnCl2, (120 μM) and compounds (L1-a or L1-b; 120 or 240 μM) were incubated with cells, ca. 40 – 50% cell survival was indicated. From these cytotoxicity studies, our bifunctional small molecules were minimally toxic at concentrations of 40 μM or lower in the presence of up to 20 μM metal ions. Thus, based on these cytotoxicity studies, testing our compounds’ effect on metal-Aβ species in a cellular environment could be explored.

In order to investigate how our bifunctional molecules influence the neurotoxicity induced by metal-associated Aβ species, we carried out the reactions of metal ions, Aβ, and compounds in the human neuroblastoma M17 cell line.37,38 Our cell studies exhibited 70(±2.4) or 80(±4.3)% of cells survived upon 24 h incubation with Cu2+- or Zn2+-treated Aβ (Figure 7). Interestingly, as described in Figure 7, when the compound with the dimethylamino functionality (L1-b) was added to Cu2+- and Zn2+-Aβ-treated cells, cell survival rates increased to ca. 9037 and 100%, respectively. Compared to L1-b, L1-a induced a slight increase in the survival of cells treated with Cu2+- or Zn2+-treated Aβ (77% and 86% cell viability for the samples of Cu2+ and Zn2+, respectively). Under the same conditions traditional metal chelators such as CQ, EDTA, and phen were not able to recover the cell survival from metal-Aβ neurotoxicity.37,38 Overall, these cell-based studies employing our bifunctional compounds demonstrate their capability to regulate metal-Aβ neurotoxicity in living cells, which is expected based on their reactivity in vitro (anti-Aβ aggregation as well as ROS regulation). These cell studies also agree with the overall observation that assessing the ability of our bifunctional compounds to interact with metal-Aβ species is a key factor to comprehend greater reactivity toward metal-induced Aβ events (structure-interaction-reactivity relationship).

Figure 7.

Regulation of metal-associated Aβ neurotoxicity in M17 cells for 24 h using the MTT assay. Cell viability (%) upon incubation of (1) Aβ; (2) [Aβ + CuCl2]; (3) [Aβ + CuCl2 + L1-a]; (4) [Aβ + CuCl2 + L1-b]; (5) [Aβ + ZnCl2]; (6) [Aβ + ZnCl2 + L1-a]; (7) [Aβ + ZnCl2 + L1-b]. Condition: [Aβ] = 20 μM, [CuCl2 or ZnCl2] = 20 μM, [compound] = 40 μM. Cell viability (%) shown in the figure is relative to that of cells containing 1% DMSO (v/v). Cytotoxicity from cells treated with metal ions and compounds were not indicated at this condition (Figures S7b and S7c).

Summary and Perspective

Small molecules that have the ability to target and modulate metal-Aβ species are greatly desired and could be instrumental in determining how metal-associated pathways may be involved with AD neuropathogenesis. To achieve this, we have taken the rational structure-based design approach to develop bifunctional compounds that are capable of chelating metal ions as well as interacting with Aβ species. Our group has previously applied this strategy to the chemical structures of two known Aβ aggregate indicators, p-I-stilbene and IMPY, that were altered through installation of heteroatoms for metal coordination. These small, neutral, lipophilic imaging agents have demonstrated attributes that render them beneficial for this application. According to their promising behavior, a further generation of compounds based on the same frameworks was devised. Importantly, the entire structure was likely a valuable contribution to targeting Aβ while simple structural modifications could improve their interaction and reactivity with Aβ and metal-Aβ species. Here, we focus on two compounds that serve as an extension to our previous studies of stilbene-like molecules; these studies supplement our understanding of how simple modifications such as the inclusion of two nitrogen atoms for metal chelation and the presence or absence of the dimethylamino functionality can influence interaction/reactivity. The bifunctionality (metal chelation and Aβ interaction) of the compounds (L1-a and L1-b) was verified by spectroscopic and other methods including UV-vis, high-resolution 2D NMR, and X-ray crystallography. Further biochemical studies displayed the potential direct interaction of our small molecules with metal-Aβ species through their ability to regulate reactivity (metal-induced Aβ aggregation and neurotoxicity) in vitro and in living cells. Together with our previous work, the studies presented here validate the selection of the stilbene compound as a model interaction framework as it importantly interacts with Aβ peptides in various aggregated forms and displays minimal toxicity in human neuroblastoma cells. In our studies, the structural moieties, such as dimethylamino functionality, are crucial parameters for a structure-interaction-reactivity relationship that can be applied to develop and tune small molecules that can target metal-Aβ species allowing for anti-Aβ aggregation, ROS regulation, and modulation of metal-Aβ neurotoxicity. Continuing investigations on this theme will be conducted to advance the construction and study of suitable chemical tools for understanding metal-Aβ-involved processes in chemistry and biology as well as potential therapeutic agents for AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by start-up funding from the University of Michigan, the Alzheimer’s Art Quilt Initiative (AAQI), as well as the Alzheimer’s Association (NIRG-10-172326) (to M.H.L.) and NIH (DK078885 to A.R.). We acknowledge funding from NSF grant CHE-0840456 for X-ray instrumentation. Joseph Braymer is grateful for the Murrill Memorial Scholarship from the Department of Chemistry at the University of Michigan. Kisoo Nam conducted this work as an intern from the Western Reserve Academy, OH, USA and is currently at Hankuk Academy Of Foreign Studies, Korea. We thank Kermit Johnson, Dr. Subramanian Vivekanandan, and Dr. Ravi P. R. Nanga for help with 900 MHz NMR experiments and data analysis, as well as Allana Mancino and Nathan Merrill for experimental assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Tables S1 and S2, Figures S1 – S7, as well as X-ray crystallographic file (CIF file). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1). www.alz.org.

- (2).Jakob-Roetne R, Jacobsen H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:3030–3059. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).DeToma AS, Salamekh S, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1039/c1cs15112f. DOI: 10.1039/c1cs15112f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Roychaudhuri R, Yang M, Hoshi MM, Teplow DB. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:4749–4753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800036200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Miller Y, Ma B, Nussinov R. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:4820–4838. doi: 10.1021/cr900377t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lovell MA, Robertson JD, Teesdale WJ, Campbell JL, Markesbery WR. J. Neurol. Sci. 1998;158:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Miller LM, Wang Q, Telivala TP, Smith RJ, Lanzirotti A, Miklossy J. J. Struct. Biol. 2006;155:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Rauk A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:2698–2715. doi: 10.1039/b807980n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Gaggelli E, Kozlowski H, Valensin D, Valensin G. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:1995–2044. doi: 10.1021/cr040410w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zatta P, Drago D, Bolognin S, Sensi SL. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009;30:346–355. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Faller P, Hureau C. Dalton Trans. 2009:1080–1094. doi: 10.1039/b813398k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Faller P. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:2837–2845. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Scott LE, Orvig C. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:4885–4910. doi: 10.1021/cr9000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Bush AI, Tanzi RE. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Barnham KJ, Curtain CC, Bush AI. Protein Rev. 2007;6:31–47. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Karr JW, Kaupp LJ, Szalai VA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13534–13538. doi: 10.1021/ja0488028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Karr JW, Szalai VA. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5006–5016. doi: 10.1021/bi702423h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Danielsson J, Pierattelli R, Banci L, Gräslund A. FEBS J. 2007;274:46–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Cappai R, Barnham KJ. Neurochem. Res. 2008;33:526–532. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9469-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Zhu X, Su B, Wang X, Smith MA, Perry G. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:2202–2210. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hureau C, Faller P. Biochimie. 2009;91:1212–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Molina-Holgado F, Hider RC, Gaeta A, Williams R, Francis P. BioMetals. 2007;20:639–654. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Huang X, Moir RD, Tanzi RE, Bush AI, Rogers JT. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1012:153–163. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Cherny RA, Atwood CS, Xilinas ME, Gray DN, Jones WD, McLean CA, Barnham KJ, Volitakis I, Fraser FW, Kim Y, Huang X, Goldstein LE, Moir RD, Lim JT, Beyreuther K, Zheng H, Tanzi RE, Masters CL, Bush AI. Neuron. 2001;30:665–676. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Adlard PA, Cherny RA, Finkelstein DI, Gautier E, Robb E, Cortes M, Volitakis I, Liu X, Smith JP, Perez K, Laughton K, Li Q-X, Charman SA, Nicolazzo JA, Wilkins S, Deleva K, Lynch T, Kok G, Ritchie CW, Tanzi RE, Cappai R, Masters CL, Barnham KJ, Bush AI. Neuron. 2008;59:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Perez LR, Franz KJ. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:2177–2187. doi: 10.1039/b919237a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Dickens MG, Franz KJ. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:59–62. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Boldron C, Van der Auwera I, Deraeve C, Gornitzka H, Wera S, Pitié M, Van Leuven F, Meunier B. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:1976–1980. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Deraeve C, Boldron C, Maraval A, Mazarguil H, Gornitzka H, Vendier L, Pitié M, Meunier B. Chem.--Eur. J. 2008;14:682–696. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Deraeve C, Pitie M, Meunier BJ. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:2117–2126. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Hureau C, Sasaki I, Gras E, Faller P. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:950–953. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Braymer JJ, DeToma AS, Choi J-S, Ko KS, Lim MH. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011;2011:623051. doi: 10.4061/2011/623051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Dedeoglu A, Cormier K, Payton S, Tseitlin KA, Kremsky JN, Lai L, Li X, Moir RD, Tanzi RE, Bush AI, Kowall NW, Rogers JT, Huang X. Exp. Gerontol. 2004;39:1641–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Rodríguez-Rodríguez C, Sánchez de Groot N, Rimola A, Álvarez-Larena Á, Lloveras V, Vidal-Gancedo J, Ventura S, Vendrell J, Sodupe M, González-Duarte P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1436–1451. doi: 10.1021/ja806062g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Hindo SS, Mancino AM, Braymer JJ, Liu Y, Vivekanandan S, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16663–16665. doi: 10.1021/ja907045h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Choi J-S, Braymer JJ, Nanga RPR, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:21990–21995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006091107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Choi J-S, Braymer JJ, Park SK, Mustafa S, Chae J, Lim MH. Metallomics. 2011;3:284–291. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00077a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Himes RA, Park GY, Siluvai GS, Blackburn NJ, Karlin KD. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:9084–9087. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Sheldrick GM. SADABS or TWINABS version 2008/1: Program for Empirical Absorption Correction of Area Detector Data.

- (42).SAINTPLUS: Software for the CCD Detector System. version 7.60a ed Bruker AXA; Madison, WI: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Sheldrick G. version 2008/3 ed Bruker AXA; Madison, WI: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Spek AL. PLATON, A Multipurpose Crystallographic Tool. Utrecht University; Utrecht, The Netherlands: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Sheldrick GM. Program for Indexing Twins and Other Problem Crystals. CELL_NOW version 2008/2 University of Göttingen; Göttingen, Germany: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Due to low solubility of the S0 and S1 in the NMR solvent, they were added from a stock solution prepared in DMSO.

- (47).Jarvet J, Danielsson J, Damberg P, Oleszczuk M, Gräslund A. J. Biomol. NMR. 2007;39:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Grzesiek S, Bax A, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM, Hu JS, Kaufman J, Palmer I, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:340–345. doi: 10.1038/nsb0496-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Garrett DS, Seok Y-J, Peterkofsky A, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4393–4398. doi: 10.1021/bi970221q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Foster MP, Wuttke DS, Clemens KR, Jahnke W, Radhakrishnan I, Tennant L, Reymond M, Chung J, Wright PE. J. Biomol. NMR. 1998;12:51–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1008290631575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Morris GM, Huey R, Olson AI. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2008 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0814s24. Chapter 8, 8.14.11-18.14.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Coles M, Bicknell W, Watson AA, Fairlie DP, Craik DJ. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11064–11077. doi: 10.1021/bi972979f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Mancino AM, Hindo SS, Kochi A, Lim MH. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:9596–9598. doi: 10.1021/ic9014256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Nielsen EH, Nybo M, Svehag S-E. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:491–496. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Reinke AA, Seh HY, Gestwicki JE. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:4952–4957. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.07.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).DeToma AS, Choi J-S, Braymer JJ, Lim MH. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:1198–1201. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Leuma Yona R, Mazères S, Faller P, Gras E. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:63–66. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Ono M, Yoshida N, Ishibashi K, Haratake M, Arano Y, Mori H, Nakayama M. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:7253–7260. doi: 10.1021/jm050635e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Bloom SM, Borror AL, Greenwald RB. 4,006,151 Vol. U.S. Patent. 1977

- (62).The ligands (L1-a and L1-b) have limited stability in aqueous solutions (t1/2 = ca. 70 s and ca. 240 s for L1-a and L1-b, respectively, in 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl ([ligand] = 40 μM)) due to their hydrolysis, which was confirmed by MS. The stability of the two compounds was enhanced in the presence of metal ions (two- or three-fold increase in t1/2 with CuCl2 or ZnCl2). On the basis of the stability studies of the ligands, the hydrolyzed products may contribute to metal-Aβ reactivity.

- (63).Dehghanpour S, Mahmoudi A, Khalaj M, Salmanpour S, Adib M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online. 2007;63:m2841. doi: 10.1107/S1600536807061429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Shao H, Jao S, Ma K, Zagorski MG. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:755–773. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, Regan CM, Walsh DM, Sabatini BL, Selkoe DJ. Nat. Med. 2008;14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Butterfield SM, Lashuel HA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:5628–5654. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Jarvet J, Damberg P, Danielsson J, Johansson I, Eriksson LEG, Gräslund A. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:371–374. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Walsh DM, Hartley DM, Kusumoto Y, Fezoui Y, Condron MM, Lomakin A, Benedek GB, Selkoe DJ, Teplow DB. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:25945–25952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Syme CD, Viles JH. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2006;1764:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Gaggelli E, Janicka-Klos A, Jankowska E, Kozlowski H, Migliorini C, Molteni E, Valensin D, Valensin G, Wieczerzak E. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:100–109. doi: 10.1021/jp075168m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Hou L, Zagorski MG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9260–9261. doi: 10.1021/ja046032u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.