Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a lethal, X-linked recessive, muscle-wasting disease1 caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene, located on chromosome Xp21. Mutations of the dystrophin gene result in the absence of the dystrophin protein, which leads to an impaired linkage between the F-actin cytoskeleton and the extracellular matrix protein laminin 2 via the membrane-bound dystrophin-glycoprotein complex (DGC).2,3

In the absence of dystrophin, the mechanical links from the cytoskeleton of the muscle cell to the membrane and the components of the DGC are absent.4 Progressive and ultimately fatal rounds of skeletal muscle degeneration and regeneration are hypothesized to result from either a fragile or weakened skeletal muscle membrane5,6 or altered cell signaling.

Beyond these general hypotheses, the specific cellular mechanisms and the temporal progression of the dystrophic process are as yet unclear. There is no current cure for DMD, and palliative and prophylactic interventions to improve the quality of life of patients remain limited, with the exception of corticosteroids. Corticosteroids are effective at prolonging ambulation but have several undesirable side effects, including growth retardation, obesity, glucose intolerance, and bone demineralization.7 Nevertheless, despite these side effects, a recent panel of experts recommended glucocorticoid therapy for all patients who have DMD. This recommendation suggests that until a suitable corticosteroid substitute is available, any additional palliative and prophylactic treatment approaches will likely be in conjunction with corticosteroids.8

This article describes two potential nutritional interventions for the treatment of DMD, green tea extract (GTE) and the branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) leucine, and their positive effects on physical activity. Both GTE and leucine are suitable for human consumption; are easily tolerated with no side effects; and, with appropriate preclinical data, could be brought forward to clinical trials rapidly. In dystrophic mdx mice, both GTE9 and leucine (Voelker KA, unpublished data, 2010) improve whole animal endurance and skeletal muscle function. Mechanistically both are mediated by signaling pathways to evoke these and other positive adaptations that attenuate the effects of dystrophic progression. To date, not all the specific pathways have been described.

CHARACTERISTICS OF DMD

The characteristics of DMD have been well described at the genetic, molecular, cellular, tissue, organ systems, and clinical levels (Table 1). Detailed descriptions are provided in several excellent reviews.6,7,10-14

Table 1.

Characteristics of DMD

| Level of Pathology | Definitions and Descriptors at Various Levels of the Disease |

|---|---|

| Genetic | X-linked, hereditary or spontaneous |

| Cellular | Absence of the protein dystrophin, mechanical weakening of the sarcolemma, inappropriate calcium influx, recurrent muscle ischemia, aberrant cell signaling, increased oxidative stress, histologic z-disk disruption, central nucleation, fiber size heterogeneity, reduced expression and mislocalization of dystrophin-associated proteins |

| Tissue | Intramuscular accumulation of fibrous connective and fatty tissue, pseudohypertrophy |

| Organ systems | Musculoskeletal system, nervous system, digestive system, immune system, cardiorespiratory system |

| Clinical | Lethal, progressive, 1:3500 live male births, muscle wasting and weakness, susceptibility to fatigue, muscle pain, elevated serum creatine kinase, myoglobinuria, Gower sign, lordosis, progressive difficulty with ambulation, contractures, contraction-induced injury, secondary disuse atrophy, increased fat mass, side effects of medications, cardiorespiratory failure |

Best Practices of Care

DMD is a complex disease to manage. Bushby and colleagues7,10 recently published a detailed set of recommendations for the management of DMD. Among the many recommendations are those related to nutrition and exercise (physical activity). It is not the authors’ intent here to discuss all the difficulties associated with nutrition (eg, swallowing problems) or exercise (eg, spinal deformities) but to focus on simple nutritional possibilities that may attenuate disease severity and progression.

Importance of Mobility

A goal for treatment of patients with DMD should be to improve quality of life,7,10 one important aspect of which is mobility. Mobility is dependent on sufficient strength and endurance in skeletal muscles to move joints through a range of motion to accomplish a movement task. Some tasks may be occasional movements significant in everyday life, such as reaching for a glass. Other movements may be repetitive and rhythmic, such as walking. Because ambulatory muscles, the diaphragm, and the heart are all adversely affected by dystrophin deficiency, mobility in individuals with DMD is severely compromised. Can nutritional therapies improve mobility?

WHY NUTRITIONAL AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY THERAPIES?

The US government has established guidelines for a balanced diet to meet the energy demands and macronutrient and micronutrient requirements for health (http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2010.asp), which includes balancing calories with physical activity to manage weight. Similarly, guidelines have been established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for a minimum participation in physical activity on a daily basis (http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/guidelines/index.html). At the most basic level, nutrition represents energy intake and adequate vitamins and minerals; physical activity represents energy output. These requirements are no less, and likely more, important for individuals with DMD.

WHAT IS CURRENTLY KNOWN

There has been little research published on effective nutrition7,8,10 or physical activity15,16 for individuals with DMD. Although it is recognized that genetic and molecular biological approaches will ultimately reveal a cure for DMD, is it prudent to over-look potential simple approaches, such as diet and physical activity, as palliative and prophylactic treatments until the cure is found? Unfortunately, these treatments are simply not being investigated rigorously. Simply put, little is known about the nutritional needs of patients with DMD and little is known about the potential positive (or negative) adaptive responses of dystrophic muscles to physical activity.

Nutrition

Davidson and Truby8 reported in their review that of approximately 1500 references they found on DMD, only 6 directly investigated the nutritional requirements of boys with DMD. Bushby and colleagues10 cited a similar small number of references, although some differed from those cited by Davidson and Truby. The total number of nutritional investigations seems to be only about 10 to 12. Based on these studies, the recommendations for nutritional guidance could be dramatically improved.8

Physical Activity

The effects of physical activity to treat DMD have been investigated for several decades (eg, Refs.17,18), yet there are still no defined exercise prescriptions that include intensity, duration, and frequency.15,16 A recent review by Markert and colleagues16 suggested that appropriately prescribed physical activity might counter key dystrophic pathogenic mechanisms, including (1) mechanical weakening of the sarcolemma, (2) inappropriate calcium influx, (3) aberrant cell signaling, (4) increased oxidative stress, and (5) recurrent muscle ischemia.

Energy Balance

Although this article focuses on two specific nutritional interventions, monitoring the energy content of diet is also a cornerstone of health and is especially important to consider in disease states such as DMD, which affect multiple organ systems.10 Excessive caloric intake leads to conditions of overweight or obesity, whereas inadequate caloric intake precedes weight loss. Boys treated with steroids gain nonfunctional mass (eg, fat, not muscle) because appetite is stimulated.8 In boys with DMD whose mobility is compromised, this problem is exacerbated because they take in more energy but expend less.

Energy IN is determined by the amount consumed and the content of the diet in kilocalories. Energy OUT includes the sum of the resting metabolic rate, the thermic effect of food, the nonexercise energy expenditure, and exercise energy cost, also measured in kilocalories.19 In addition, the disease and medications can contribute to energy status in patients with DMD.8 When energy IN exceeds energy OUT, weight gain results. Systematic studies of energy expenditure in patients with DMD, using metabolic equivalents20 (MET = 3.5 mL oxygen/kg body mass/min), have been suggested16 to better prescribe physical activity and exercise guidelines. These studies would also help inform dietary guidelines for energy intake.

Pharmaceutical and Nutritional Interventions

Although the main impetuses to cure DMD are focused on genetic and molecular biological approaches, nutritional therapies could represent an appropriate and simple palliative approach.21-23 For example, treatment with the amino acids glutamine24,25 and arginine plus deflazacort23 were reported to improve nitrogen retention and maintain protein balance in patients with DMD. However, at present there have been few detailed investigations of nutritional interventions in DMD. Radley and colleagues26 succinctly provided a summary and analysis of several potential pharmaceutical and nutritional interventions as therapeutic agents in mdx mice and DMD. Among the potential nutritional interventions cited was GTE, which the investigators suggested was ready for clinical trial with the exception of the appropriate dose. In addition, several amino acids were also cited for possible use in treating DMD including taurine, glutamine, alanine, and arginine (alone or in various combinations). However, a caveat to the use of these amino acids was that they had yet to be formally evaluated. The potential benefits of leucine were not reported. The authors now summarize briefly the current literature on GTE, provide the likely signaling pathways of leucine to induce protein synthesis, and provide evidence of the benefits of leucine on strength in mdx mice and whole-body endurance.

GTE

GTE has been reported to ameliorate dystrophic pathology in mdx mice. Initial studies indicated that oxidative stress may contribute to muscular dystrophy symptoms,27-32 and early administration of dietary GTE to young mdx mice (and their dams, before weaning) protected against muscle necrosis in the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle.33 Recognized for its antioxidative properties, GTE was investigated further as a possible protection against progression of muscular dystrophy. Administration early in the course of the disease was repeated in a study that compared GTE with its major component, epigallocatechin gallate (ECGC),34 a polyphenol. This study also showed reduced necrosis in muscles from GTE-treated and ECGC-treated mice, and furthermore reported improved muscle strength and fatigue resistance in functional assays.

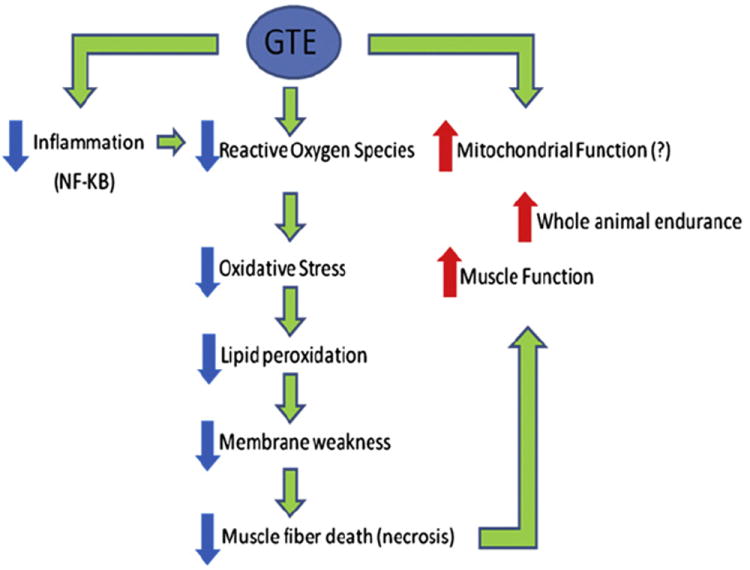

In another study,9 voluntary exercise (wheel running) and GTE were investigated in 21-day-old mdx mice. Both conditions independently showed beneficial effects in assays of contractile properties, metabolic activity, lipid peroxidation, and antioxidant capacity. Synergistic effects of the combined treatments were also reported to benefit endurance capacity, although some other beneficial effects of GTE were mitigated by running. Mechanistic and time-course data35 indicate that GTE potentially ameliorates pathology by acting on the nuclear factor κB pathway. Histologic assays of GTE-treated mdx muscle showed a reduced area of regenerating fibers, indicating a protective effect, and a fiber morphology more like that of non-diseased muscle. In summary, GTE and its polyphenolic constituents merit further study as possible regulators of oxidative stress and inflammation. Just as light swimming exercise may benefit aerobic and cardiorespiratory capacity, particularly of young ambulatory patients with DMD,10 nutraceuticals such as BCAAs and GTE may provide benefit in additional biochemical and functional outcome measures (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overview of positive physiologic effects of green tea extract (GTE) in mdx mice. The potential beneficial effects of GTE on mitochondrial function have not yet been determined mechanistically. NF, nuclear factor.

Leucine

Leucine is an essential BCAA with unique features. In addition to being a building block of proteins, it is an anabolic signal that induces protein synthesis.36 In addition, it plays a role in glucose homeostasis.37 Leucine also acts as a nitrogen donor for the synthesis of alanine and glutamine in the muscle.38 Glutamate, which itself is the precursor of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), is produced from the transamination reaction of leucine and other BCAAs, and is a major excitatory neurotransmitter.39

Leucine also improves nitrogen retention by increasing muscle protein synthesis and decreasing myofibrillar breakdown in normal pigs.40-43 Although both of these leucine-related effects would be relevant to reversal of the degradation processes in dystrophic muscle, it is not known whether dystrophic muscle will respond similarly. There is only one controlled clinical trial (conducted in 1984) that has investigated the therapeutic potential of leucine.44 This study demonstrated a transient increase in muscle strength reported after the first month of a 12-month trial, but results were later confounded by the unusual rate of functional decline in the placebo group. More recently, D’Antona and colleagues45 reported that supplementation with BCAAs promoted longevity as well as skeletal and cardiac muscle biogenesis in middle-aged mice, including enhanced physical endurance. Similarly, the authors’ recent preliminary data demonstrating improved contractile and endurance performance in the mdx mouse indicate that leucine may be an effective nutritional therapy for DMD.

Mammalian target of rapamycin

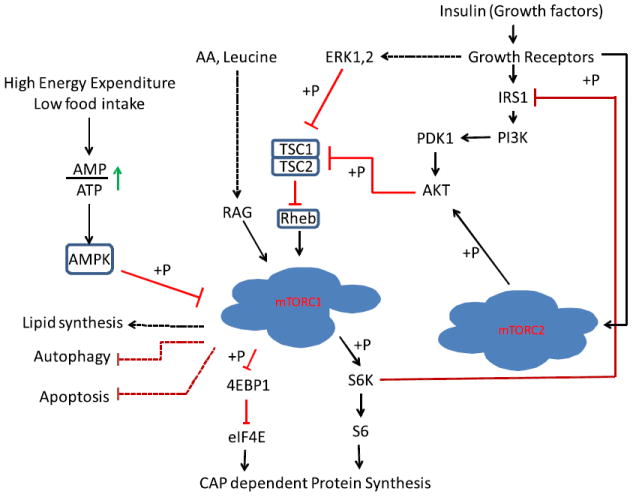

Although it is well established that leucine can stimulate protein synthesis through the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway,36,46-51 the identity of sensor(s) for leucine is not known.52 The strongest link between amino acids and mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) is the Rag guanosine triphosphatases, which, in response to amino acids, bind to raptor (Fig. 2).53,54 This interaction alters the intracellular location of the mTORC1 to a compartment where its activator Rheb is present. Activated mTORC1 phosphorylates substrates, of which ribosomal S6 protein kinase (S6K) and 4E-binding protein-1 (4EBP-1) are well known.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin complex (mTORC) signaling networks. Growth factors/mitogens (insulin, epidermal growth factor) and nutrients (eg, amino acids, energy) promote mTORC1 signaling via phosphorylation cascades that converge on tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and the mTORCs themselves. Insulin signals via its receptor (Insulin-R) to activate the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/TSC/Rheb pathway; amino acid sufficiency signals via hVps34 and the Rag and RalA guanosine triphosphatases; and energy sufficiency suppresses AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). Insulin/PI3K signaling likely promotes mTORC2 signaling via an unknown pathway. An mTORC1/S6 protein kinase (S6K)-mediated negative feedback loop signals via 2 pathways to suppress PI3K/mTORC2/Akt signaling. AA, amino acids; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; 4EBP-1, 4E-binding protein-1; eIF4E, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E; ERK, extracellular signal–regulated kinase; IRS1, Insulin Receptor Substrate 1; PDK1, Phosphoinositide Dependent Protein Kinase 1; S6, S6 Ribosomal Protein.

Phosphorylated S6K phosphorylates many substrates including S6 ribosomal protein, which is an essential component of the protein translation initiation machinery. On the other hand, 4EBP-1 phosphorylation causing its release from eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), allowing the initiation of CAP-dependent protein synthesis.55,56 In addition to nutrients, mTORC1 is activated by growth factors, especially insulin.57 Insulin binding activates Ras-Erk1/2 and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT pathways, which merge at tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2).52 The TSC1-TSC2 complex inactivates the mTORC1 complex through the hydrolysis of guanosine triphosphate, which is required for Rheb to activate mTORC1. Phosphorylation of TSC2 inhibits the activity of the TSC1-TSC2 complex, allowing the activation of Rheb and consequently mTORC1.52 Activation of the PI3K pathway activates another TOR complex known as mTORC2. mTORC2 is believed to participate in cell growth and cytoskeletal organization.58

The mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes consist of mTOR plus several proteins, some common to both complexes and others unique to each complex. These components play a role in substrate recognition, or act as positive and negative regulators of the TOR complexes.59,60 Insulin can regulate mTORC2 by increasing phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)P(3) (PIP3) through PI3K, which ultimately leads to the phosphorylation and activation of AKT.52,61 mTORC1 and mTORC2 phosphorylate different substrates and respond differently to rapamycin. Short-term treatment of cells with rapamycin inhibits mTORC1 with no effect on mTORC2, whereas prolonged treatment causes the inhibition of the mTORC2 complex perhaps through sequestration of the cellular pool of mTOR in a complex with rapamycin-FKBP12.62 Increasing evidence suggests that the two complexes directly or indirectly interact with each other. Activation of mTORC1 activates S6K, which in turn phosphorylates IRS1, downregulating insulin response.63,64 Decreased insulin response reduces the PI3K-AKT pathway activity, which would negatively affect mTORC2.65 In addition, active S6K phosphorylates Rictor, negatively affecting mTORC2 activity.66 It was shown that mTORC1 phosphorylates the growth factor receptor-bound protein 10 (Grb10) resulting in its stability, and leading to a feedback inhibition of the PI3K and extracellular signal-regulated, mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK-MAPK) pathways.67,68 The presence of these cross talks and negative feedback loops ensures controlled cell growth. Therefore, understanding the pathways and identifying molecules involved in the cross talk between mTORC1 and mTORC2 will enable these pathways to be exploited in various pathologic conditions ranging from muscular atrophy to cancer and diabetes.

Amelioration of mdx pathology by leucine

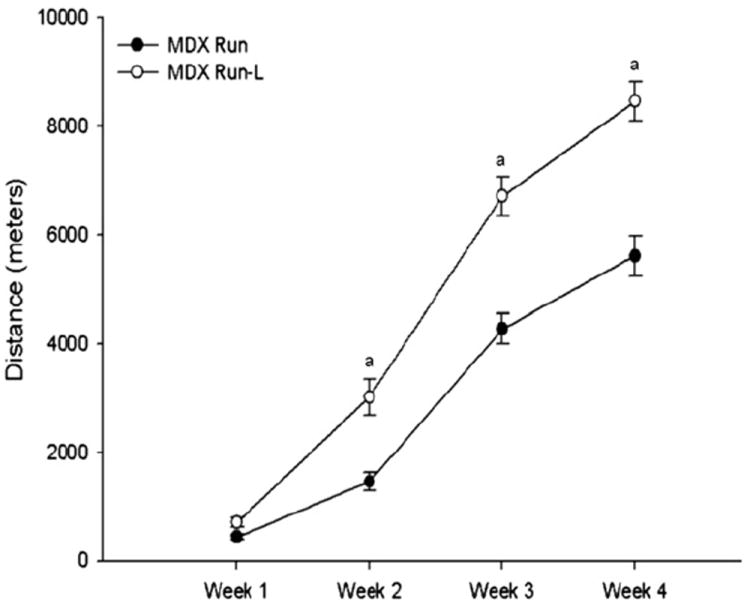

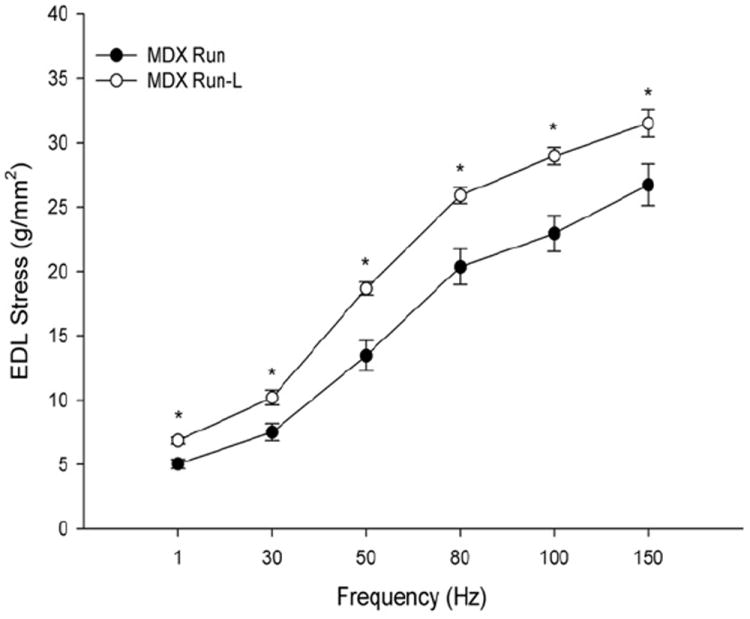

In animal models of other muscle-wasting disorders such as sepsis and cachexia, supplementation with leucine helped maintain muscle mass.55,69-74 The mdx mouse is a widely used preclinical model of DMD, because muscles of these mice, like boys with DMD, lack the protein dystrophin. Preliminary data from a pilot study conducted in the Grange Laboratory suggest that both running endurance and muscle strength in mdx mice are dramatically improved after 4 weeks of treatment with leucine-supplemented water. As shown in Fig. 3, the mean distance run was significantly higher in weeks 2 to 4 in mdx mice supplemented with leucine. Cages were equipped with a running wheel automated to measure voluntary wheel-running time. At the end of 4 weeks, muscle parameters such as stress-generating capacity were measured in vitro. Stress-generating capacity for EDL muscles was increased at all electrical stimulation frequencies (Fig. 4, P<.05). What is remarkable is that EDL muscle mass was not different between the mdx (9.4 ± 0.8 mg) and mdx-leucine groups (10.2 ± 1.4 mg), nor was fiber size (data not shown), indicating that hypertrophy did not account for the increased stress production. Furthermore, there was no change in fiber number, number of centralized nuclei, or myosin heavy chain distribution (data not shown). Collectively, these data suggest that even if skeletal muscle in leucine-treated mdx mice does not hypertrophy, it still improves endurance capacity and the ability to produce force.

Fig. 3.

Weekly running distance for the MDX Run Leucine (MDX Run-L) group was greater at weeks 2, 3, and 4 (P<.05). Leucine treatment clearly improved whole animal endurance, suggesting potential changes in muscle metabolism and the cardiovascular system.

Fig. 4.

Stress-frequency curve of MDX Run and MDX Run-L extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles. All tests were performed in vitro, in an oxygenated bath. *MDX Run-L group was significantly greater than the MDX Run group. Values are reported as mean ± SEM, P<.05.

Evaluation of Nutraceuticals and Nutritional Interventions

Experimental designs focused on elucidating the role of nutrition in the treatment of DMD may benefit from (1) incorporating previously defined standard operating procedures (SOPs) for preclinical experiments,13 and (2) approaching nutrition research questions with the same mechanistic framework16 used to define the role of exercise in the treatment of DMD. In brief, when designing experiments and selecting outcome measures in studies on both exercise and nutrition, DMD researchers should consider the reliability of the measures, their validity, how they represent DMD pathophysiology, and whether the measures facilitate translation of results from animal models to the human condition.13 Blinded assessment of outcome measures is another consideration, as is using data to generate hypotheses and plan future statistical analyses. Established SOPs for many relevant outcome measures are readily available (http://www.treat-nmd.eu/research/preclinical/dmd-sops/). In addition, selection of appropriate outcome measures may be more straightforward if the measures target specific mechanisms of DMD pathophysiology.

In brief, if sarcolemmal weakening and damage is the mechanism of disease, and an exercise or nutrition intervention is hypothesized to ameliorate the damage, then outcome measures based on methods such as Evans blue dye injection, Procion orange injection, the creatine kinase assay, current clamp, voltage clamp, histology, immunohistochemistry, force production measures, and intracellular Ca2+ indicators, are indicated.16 Interventional studies in mdx mice provide examples of experimental designs for the evaluation of nutrition in muscular dystrophy,35,75 as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples of experimental designs to test nutritional interventions

RECOMMENDATIONS

There is an immediate need to gather sufficient preclinical evidence to move forward to clinical trials.

As with studies of physical activity in muscular dystrophy, future studies of nutritional interventions, in both animals and humans, need to use standardized, reliable, systematic methods to assess outcomes. This approach allows for cross-study comparison.

Granting agencies play a key role in determining whether studies of nutrition-related topics in DMD are prioritized and funded. Targeted requests for proposals, and identification of grant reviewers who have specific expertise in evaluating the potential therapeutic benefits of nutritional interventions, may reinvigorate this area of research.

Whatever nutritional and/or physical intervention is studied, there will be a requisite need to assess combined therapy, particularly with prednisolone or deflazacort (or new corticosteroid derivatives as they are developed).

SUMMARY

There is a dearth of knowledge regarding effective interventions based on nutrition and physical activity for enhancement of physical capabilities in DMD.10,16 As a result, guidelines for each are limited. However, concerted efforts by funding agencies and the DMD research community have the potential to overcome these limitations by expanding the available data base. Promising nutritional interventions, such as GTE and leucine, may find their path to the clinic expedited in the context of reprioritized policy and funding.

References

- 1.Durbeej M, Campbell KP. Muscular dystrophies involving the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex: an overview of current mouse models. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12(3):349–61. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blake DJ, Weir A, Newey SE, et al. Function and genetics of dystrophin and dystrophin-related proteins in muscle. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(2):291–329. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies KE, Nowak KJ. Molecular mechanisms of muscular dystrophies: old and new players. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(10):762–73. doi: 10.1038/nrm2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ervasti JM, Ohlendieck K, Kahl SD, et al. Deficiency of a glycoprotein component of the dystrophin complex in dystrophic muscle. Nature. 1990;345(6273):315–9. doi: 10.1038/345315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrof BJ, Shrager JB, Stedman HH, et al. Dystrophin protects the sarcolemma from stresses developed during muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(8):3710–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrof BJ. The molecular basis of activity-induced muscle injury in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;179(1-2):111–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1006812004945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bushby K, Finkel R, Birnkrant DJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(1):77–93. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson ZE, Truby H. A review of nutrition in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2009;22(5):383–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2009.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Call JA, Voelker KA, Wolff AV, et al. Endurance capacity in maturing mdx mice is markedly enhanced by combined voluntary wheel running and green tea extract. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105(3):923–32. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00028.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bushby K, Finkel R, Birnkrant DJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: implementation of multidisciplinary care. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(2):177–89. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ervasti JM, Sonnemann KJ. Biology of the striated muscle dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Int Rev Cytol. 2008;265:191–225. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)65005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrof BJ. Molecular pathophysiology of myofiber injury in deficiencies of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81(Suppl 11):S162–74. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200211001-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willmann R, De Luca A, Benatar M, et al. Enhancing translation: Guidelines for standard pre-clinical experiments in mdx mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2011.04.012. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willmann R, Possekel S, Dubach-Powell J, et al. Mammalian animal models for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19(4):241–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grange RW, Call JA. Recommendations to define exercise prescription for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2007;35(1):12–7. doi: 10.1249/01.jes.0000240020.84630.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markert CD, Ambrosio F, Call JA, et al. Exercise and Duchenne muscular dystrophy: toward evidence-based exercise prescription. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43(4):464–78. doi: 10.1002/mus.21987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hudgson P, Gardner-Medwin D, Pennington RJ, et al. Studies of the carrier state in the Duchenne type of muscular dystrophy. I. Effect of exercise on serum creatine kinase activity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1967;30(5):416–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.30.5.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sockolov R, Irwin B, Dressendorfer RH, et al. Exercise performance in 6-to-11-year-old boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1977;58(5):195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine JA. Measurement of energy expenditure. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(7A):1123–32. doi: 10.1079/phn2005800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(6):975–91. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199806000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Passaquin AC, Renard M, Kay L, et al. Creatine supplementation reduces skeletal muscle degeneration and enhances mitochondrial function in mdx mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12(2):174–82. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00273-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruegg UT, Nicolas-Metral V, Challet C, et al. Pharmacological control of cellular calcium handling in dystrophic skeletal muscle. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12(Suppl 1):S155–61. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(02)00095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Archer JD, Vargas CC, Anderson JE. Persistent and improved functional gain in mdx dystrophic mice after treatment with L-arginine and deflazacort. FASEB J. 2006;20(6):738–40. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4821fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hankard RG, Hammond D, Haymond MW, et al. Oral glutamine slows down whole body protein breakdown in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Res. 1998;43(2):222–6. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199802000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mok E, Eleouet-Da Violante C, Daubrosse C, et al. Oral glutamine and amino acid supplementation inhibit whole-body protein degradation in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(4):823–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radley HG, De Luca A, Lynch GS, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: focus on pharmaceutical and nutritional interventions. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(3):469–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bornman L, Rossouw H, Gericke GS, et al. Effects of iron deprivation on the pathology and stress protein expression in murine X-linked muscular dystrophy. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56(6):751–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Disatnik MH, Chamberlain JS, Rando TA. Dystrophin mutations predict cellular susceptibility to oxidative stress. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23(5):784–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(200005)23:5<784::aid-mus17>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Disatnik MH, Dhawan J, Yu Y, et al. Evidence of oxidative stress in mdx mouse muscle: studies of the pre-necrotic state. J Neurol Sci. 1998;161(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy ME, Kehrer JP. Free radicals: a potential pathogenic mechanism in inherited muscular dystrophy. Life Sci. 1986;39(24):2271–8. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(86)90657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ragusa RJ, Chow CK, Porter JD. Oxidative stress as a potential pathogenic mechanism in an animal model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 1997;7(6-7):379–86. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(97)00096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rando TA, Disatnik MH, Yu Y, et al. Muscle cells from mdx mice have an increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. Neuromuscul Disord. 1998;8(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(97)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buetler TM, Renard M, Offord EA, et al. Green tea extract decreases muscle necrosis in mdx mice and protects against reactive oxygen species. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75(4):749–53. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorchies OM, Wagner S, Vuadens O, et al. Green tea extract and its major polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin gallate improve muscle function in a mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290(2):C616–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00425.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans NP, Call JA, Bassaganya-Riera J, et al. Green tea extract decreases muscle pathology and NF-kappaB immunostaining in regenerating muscle fibers of mdx mice. Clin Nutr. 2010;29(3):391–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anthony JC, Anthony TG, Kimball SR, et al. Orally administered leucine stimulates protein synthesis in skeletal muscle of postabsorptive rats in association with increase eIF4F formation. J Nutr. 2000;130:139–45. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nair KS, Woolf PD, Welle SL, et al. Leucine, glucose, and energy metabolism after 3 days of fasting in healthy human subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;46(4):557–62. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/46.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norton LE, Layman DK. Leucine regulates translation initiation of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle after exercise. J Nutr. 2006;136(2):533S–7S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.2.533S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lieth E, LaNoue KF, Berkich DA, et al. Nitrogen shuttling between neurons and glial cells during glutamate synthesis. J Neurochem. 2001;76(6):1712–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugawara T, Ito Y, Nishizawa N, et al. Regulation of muscle protein degradation, not synthesis, by dietary leucine in rats fed a protein-deficient diet. Amino Acids. 2009;37(4):609–16. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Escobar J, Frank JW, Suryawan A, et al. Regulation of cardiac and skeletal muscle protein synthesis by individual branched-chain amino acids in neonatal pigs. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:612–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00402.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Escobar J, Frank JW, Suryawan A, et al. Physiological rise in plasma leucine stimulates muscle protein synthesis in neonatal pigs by enhancing translation initiation factor activation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288(5):E914–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00510.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Escobar J, Frank JW, Suryawan A, et al. Amino acid availability and age affect the leucine stimulation of protein synthesis and eIF4F formation in muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293(6):E1615–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00302.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mendell JR, Griggs RC, Moxley RT, 3rd, et al. Clinical investigation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: IV. Double-blind controlled trial of leucine. Muscle Nerve. 1984;7(7):535–41. doi: 10.1002/mus.880070704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.D’Antona G, Ragni M, Cardile A, et al. Branched-chain amino acid supplementation promotes survival and supports cardiac and skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis in middle-aged mice. Cell Metab. 2010;12(4):362–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anthony JC, Yoshizawa F, Anthony TG, et al. Leucine stimulates translation initiation in skeletal muscle of postabsorptive rats via a rapamycin-sensitive pathway. J Nutr. 2000;130(10):2413–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.10.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buse MG, Reid SS. Leucine. A possible regulator of protein turnover in muscle. J Clin Invest. 1975;56:1250–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI108201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Busquets S, Alvarez B, Lopez-Soriano FJ, et al. Branched-chain amino acids: a role in skeletal muscle proteolysis in catabolic states? J Cell Physiol. 2002;191(3):283–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fulks RM, Li JB, Goldberg AL. Effects of insulin, glucose, and amino acids on protein turnover in rat diaphragm. J Biol Chem. 1975;250(1):290–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong SO, Layman DK. Effects of leucine on in vitro protein synthesis and degradation in rat skeletal muscles. J Nutr. 1984;114:1204–12. doi: 10.1093/jn/114.7.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakashima K, Ishida A, Yamazaki M, et al. Leucine suppresses myofibrillar proteolysis by down-regulating ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in chick skeletal muscles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336(2):660–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(1):21–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim E, Goraksha-Hicks P, Li L, et al. Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient response. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(8):935–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, et al. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320(5882):1496–501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Armengol G, Rojo F, Castellvi J, et al. 4E-binding protein 1: a key molecular “funnel factor” in human cancer with clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2007;67(16):7551–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Avruch J, Long X, Ortiz-Vega S, et al. Amino acid regulation of TOR complex 1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296(4):E592–602. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90645.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scott PH, Brunn GJ, Kohn AD, et al. Evidence of insulin-stimulated phosphorylation and activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin mediated by a protein kinase B signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(13):7772–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sparks CA, Guertin DA. Targeting mTOR: prospects for mTOR complex 2 inhibitors in cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2010;29(26):3733–44. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, et al. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell. 2002;10(3):457–68. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peterson TR, Laplante M, Thoreen CC, et al. DEPTOR is an mTOR inhibitor frequently overexpressed in multiple myeloma cells and required for their survival. Cell. 2009;137(5):873–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gan X, Wang J, Su B, et al. Evidence for direct activation of mTORC2 kinase activity by phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(13):10998–1002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.195016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, et al. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22(2):159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tremblay F, Brule S, Um SH, et al. Identification of IRS-1 Ser-1101 as a target of S6K1 in nutrient- and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14056–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706517104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Um SH, D’Alessio D, Thomas G. Nutrient overload, insulin resistance, and ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1, S6K1. Cell Metab. 2006;3:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dobashi Y, Watanabe Y, Miwa C, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin: a central node of complex signaling cascades. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2011;4(5):476–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dibble CC, Asara JM, Manning BD. Characterization of Rictor phosphorylation sites reveals direct regulation of mTOR complex 2 by S6K1. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(21):5657–70. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00735-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hsu PP, Kang SA, Rameseder J, et al. The mTOR-regulated phosphoproteome reveals a mechanism of mTORC1-mediated inhibition of growth factor signaling. Science. 2011;332(6035):1317–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1199498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu Y, Yoon SO, Poulogiannis G, et al. Phosphoproteomic analysis identifies Grb10 as an mTORC1 substrate that negatively regulates insulin signaling. Science. 2011;332(6035):1322–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1199484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ventrucci G, Mello MA, Gomes-Marcondes MC. Effect of a leucine-supplemented diet on body composition changes in pregnant rats bearing Walker 256 tumor. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34(3):333–8. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2001000300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gomes-Marcondes MC, Ventrucci G, Toledo MT, et al. A leucine-supplemented diet improved protein content of skeletal muscle in young tumor-bearing rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36(11):1589–94. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003001100017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Siddiqui R, Pandya D, Harvey K, et al. Nutrition modulation of cachexia/proteolysis. Nutr Clin Pract. 2006;21(2):155–67. doi: 10.1177/0115426506021002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ventrucci G, Mello MA, Gomes-Marcondes MC, et al. Leucine-rich diet alters the eukaryotic translation initiation factors expression in skeletal muscle of tumour-bearing rats. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.De Bandt JP, Cynober L. Therapeutic use of branched-chain amino acids in burn, trauma, and sepsis. J Nutr. 2006;136(Suppl 1):308S–13S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.308S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vary TC, Lynch CJ. Nutrient signaling components controlling protein synthesis in striated muscle. J Nutr. 2007;137(8):1835–43. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.8.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.De Luca A, Pierno S, Liantonio A, et al. Enhanced dystrophic progression in mdx mice by exercise and beneficial effects of taurine and insulin-like growth factor-1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304(1):453–63. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.041343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]