Abstract

Adenosine receptor (AR) agonists and antagonists are ~100-fold and 100,000-fold, respectively, more potent at the bovine A1AR as compared to the rat A3AR. To determine regions of ARs involved in ligand recognition, chimeric receptors composed of bovine A1AR and rat A3AR sequence were constructed and their ligand binding properties examined following expression in COS-7 cells. Substitutions oft he second extracellular loop or a region encompassing transmembrane domains 6 and 7 of the A1AR into the A3AR resulted in enhanced affinities of both agonists and antagonists compared to wild-type A3AR. The region of the second extracellular loop of the A1AR responsible for this effect was identified as the distal eleven amino acids of the loop. Replacement of this segment of the A3AR with that of the A1AR in combination with the regions encompassing transmembrane domains 6 and 7 resulted in a 50,000-fold increase in the Kd for antagonist radioligand, [3H]1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine. Agonist affinity at this chimeric was over 100-fold greater than that displayed by wild-type A3AR. Thus, multiple regions of ARs including a segment of the second extracellular loop are involved in ligand recognition, and considerable overlap exists in structural features required for agonist and antagonist binding.

Adenosine modulates a variety of physiologic functions throughout the body via the activation of cell surface receptors. Adenosine receptors (ARs)1 are thus potential therapeutic targets in the treatment of pathophysiologic conditions including those of cardiovascular (1), central nervous system (2), and pulmonary (3) origins. Because of the widespread distribution of AR subtypes, therapeutic regulation of ARs via either activation or antagonism must be selective.

Molecular cloning has resulted in the identification of four AR subtypes, the A1AR (4–10), A2aAR (11–13), A2bAR (14, 15), and A3AR (16–18) from a variety of species. ARs belong to the superfamily of the seven transmembrane domain G protein-coupled receptors and elicit cellular responses via the activation or inhibition of distinct signaling pathways. These subtypes, either in native tissues or expressed in mammalian cells, can be distinguished by their binding affinities for various agonist and antagonist ligands. Recent studies employing site-directed mutagenesis of ARs have begun to determine the structural features of the receptor involved in ligand binding. Replacement of histidine residues located in the transmembrane domains of the bovine A1AR had significant effects on agonist and antagonist binding by the receptor. Mutation of the histidine at position 278 in TM 7 resulted in a complete loss of agonist and antagonist radioligand binding, while histidine 251 in TM 6 appeared to be involved in antagonist but not agonist binding by the receptor (7). Earlier studies with diethylpyrocarbonate-treated rat brain membranes had suggested the involvement of histidines in ligand recognition by the A1AR (19). Histidine residues in TM 6 and 7 are conserved in all A1ARs, A2aARs, and A2bARs cloned to date, although the three species homologs of the A3AR contain histidines in TM 3 and 7.

Subsequent studies have indicated that the precise AR binding site apparently differs not only for antagonist and agonist ligands but also for agonists containing different functional groups at discrete positions. Distinct receptor regions form the ligand binding pocket for agonists containing a substitution at the N6-position of the adenine ring, of which R-PIA is a prototype, and those agonists substituted at the 5′-position of the ribose moiety of which NECA is representative. Specifically, Townsend-Nicholson and Schofield (20) observed that a mutation of threonine at position 277 (TM 7) of the human A1AR to an alanine produced a 400-fold decrease in the affinity for NECA, although affinities for R-PIA and the antagonist radioligand, [3H]DPCPX were relatively unaffected. In an analysis of chimeric receptors composed of bovine A1AR and rat A3AR sequence, Olah and co-workers (21) found that substitution of TM 5 of the A3AR into the A1AR resulted in a substantial enhancement of binding of a series of agonist compounds containing a 5′-functional group. The affinity of antagonists and N6-substituted agonists were not altered. This effect was localized to a 6-amino acid segment in the exofacial portion of TM 5 (21).

Thus, published studies to date have identified certain crucial amino acids of ARs involved in ligand binding and have specifically begun to characterize the regions involved in recognition of 5′-substituted agonists compounds. However, the AR binding pocket remains relatively incompletely described and regions involved in antagonist binding have yet to be truly identified. To further assess antagonist binding parameters, we have constructed and characterized a set of chimeric ARs composed of bovine A1AR and rat A3AR sequence. These specific subtypes, which display ~60% amino acid identity in the transmembrane domains, possess in many ways the most divergent ligand binding properties of ARs (Fig. 1) Primarily, the A1AR and rat A3AR differ dramatically in their binding of xanthine derivative antagonists. Several of these compounds such as XAC and DPCPX have Kd values below 1 nm for the A1AR (7, 22), while at concentrations of 10 μm displace only ~10–25% of agonist binding from the rat A3AR (16). The sheep (17) and human (18) A3ARs possess appreciably higher affinity for certain xanthine compounds but remain much less sensitive than the A1AR. Agonist pharmacology also varies at the bovine A1AR and rat A3AR subtypes with differences both in overall affinities and the rank potency order of analogs traditionally employed in AR classification. Thus, in competition for agonist radioligands, the bovine A1AR and rat A3AR display Ki values of ~0.02 and 200 nm, respectively, for R-PIA (7, 16, 20). At the bovine A1AR, R-PIA is ~100-fold more potent than NECA, while the agonists are of equal affinities at the rat A3AR (7, 16, 23).

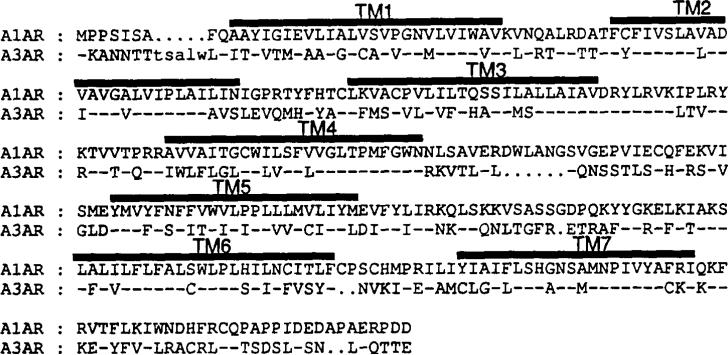

Fig. 1. Comparison of amino acid sequences of the bovine A1AR and rat A3AR.

Amino acid sequence is shown in single-letter code. Hyphens represent identical amino acids, and dots are gaps in sequence to permit alignment. The seven putative transmembrane domains are marked.

This report describes the identification of two distinct AR regions, which are involved in agonist and antagonist recognition. These regions include the distal segment of the second extracellular loop and a region encompassing TM 6 and 7 ARs. The concurrent replacement of both of these regions of the A3AR with the analogous segments of the A1AR result in chimeric receptors displaying high affinity agonist and antagonist binding.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) was employed in the polymerase chain reaction construction of chimeric receptors. Restriction enzymes were from either New England Biolabs or Boehringer Mannheim. AB-MECA was synthesized and radioiodinated as described previously (23). [3H]DPCPX and [3H]XAC were from Du-Pont NEN. R-PIA and NECA were from Sigma and Boehringer Mannheim, respectively. XAC and DPCPX were purchased from Research Biochemicals International. BW-A1433 was synthesized by K. A. J. All cell culture supplies were from Life Technologies, Inc.

Nomenclature and Construction of Chimeric Adenosine Receptors

The bovine A1AR (7) and rat A1AR (16) cDNAs were used as templates for the creation of all chimeric receptors in this study. Chimeric receptors are identified using the following nomenclature. The initial designation, A1- or A3-, represents that receptor from which the majority of sequence is obtained. Regions following the hyphen are those that have been replaced with the analogous sequence from the donor receptor with the following abbreviations: T, transmembrane domain; EL, extracellular loop; and IL, intracellular loop. The numeral following the abbreviation identifies the exact region, e.g. T35 designates transmembrane domains 3 and 5 and EL2 designates extracellular loop 2. The composition of all chimeric receptors is shown schematically in the appropriate tables.

The majority of chimeric receptors were constructed using a three-step polymerase chain reaction approach with oligonucleotides consisting of both A1AR and A3AR sequence specifying the splicing junction. For those chimeric receptors containing a limited amount of sequence substitution, A3-EL2A and A3-EL2B, mutations were made using a single oligonucleotide to specify the base changes. For those chimeric receptors containing noncontiguous regions of replaced sequence, e.g. those containing transmembrane domains 6 and 7 of the A1AR in combination with other segments of A1AR sequence, construction was performed using the “parent” chimeric receptors and a unique MluI restriction site in the A3AR cDNA that codes for the Thr-Arg-Ala sequence in the third intracellular loop of the receptor. Following subcloning of the engineered construct into the expression vector, sequence was confirmed by double-stranded cDNA sequencing using Sequenase (U. S. Biochemical Corp.).

Cell Culture and DNA Transfection

COS-7 cells were used for all studies. Cell were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transient transfection of COS-7 cells was performed viath e DEAE-dextran method (24) employing 15–25 μg of the cDNA expression vector constructs. All cDNAs were subcloned into either one of the two expression vectors, pCMV5 (Dr. D. Russell, University of Texas Southwestern) or pBC (Dr. B. Cullen, Duke University, Ref. 24). The selection of either vector was based on the presence or absence of the rare restriction enzyme sites employed in construction of the chimeric receptors thus facilitating subcloning. Equivalent radioligand binding results have been obtained for the wild-type rat A3AR subcloned into either expression vector.

Radioligand Binding Assays

Cell membranes were prepared 48–72 h post-transfection. Radioligand binding assays were performed using conditions and buffers that have been found previously to give optimum results for both bovine A1AR (7) and rat A3AR (16, 23). COS-7 cells in 75-cm2 flasks were washed twice with 10 ml of ice-cold 10 mM Tris, 5 mm EDTA, pH 7.4. Cells were scraped into 5 ml of this buffer and disrupted by 20 strokes by hand in a glass homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 43,000 × g for 10 min and the membrane pellet resuspended in 50 mm Tris, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.26, at 5 °C. Adenosine deaminase was added to give a final concentration of 2 units/ml. All assays were conducted at 37 °C for 1 h and terminated by filtration using a Brandel cell harvester and rapid washing with 50 mm Tris, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.01% CHAPS over glass fiber filters pretreated with 0.3% polyethyleneimine.

All chimeric receptors were initially screened for binding in [125I]AB-MECA and [3H]DPCPX saturation assays. [125I]AB-MECA, an N6-, 5′-disubstituted adenosine analog, has recently been characterized as a high affinity agonist radioligand for the rat (Kd = 1.2 nm) and sheep (Kd = 3.5 nm) A3AR (23). [125I]AB-MECA also displays high affinity binding (Kd = 0.6 nm) at the bovine A1AR (21, 23). The antagonist radioligand [3H]DPCPX was used in assays at concentrations up to 10 nm. Saturation binding assays were performed using 10 μm R-PIA to define nonspecific binding. Chimeric receptors were then characterized in competition binding assays employing [125I]AB-MECA as the labeled ligand. R-PIA, an N6-substituted agonist, and NECA, a 5′-substituted agonist, were both studied as previous work indicates that the ligand binding site for these ligands, although perhaps overlapping is not identical (20, 21). Finally, to determine possible antagonist binding affinities below the level of detection in [3H]DPCPX saturation analysis, XAC competition assays were performed versus [125I]AB-MECA. For certain chimeric receptors that displayed moderate antagonist affinity, the xanthine derivatives DPCPX and BW-A1433 were also examined.

Data were analyzed via a previously described computer modeling system (25). IC50 values obtained from computer analysis of competition curves were converted to Ki values using the Cheng-Prusoff equation (26). Slopes of curves were not significantly different from unity. For each construct, the appropriate Kd value obtained for [125I]AB-MECA was used in the conversion. For the WT A3AR and certain chimeric receptors displaying very low affinity for antagonist ligands, complete competition curves could not be constructed. The presence of the solvents dimethyl sulfoxide and methanol, at high concentrations in 5 mm stock solutions of XAC and DPCPX, respectively, prevented dose-response analysis to be performed in excess of 0.1 mm. In these instances, values representing the percent inhibition of radioligand binding at 10 μm antagonist is provided.

RESULTS

To determine the structural requirements of adenosine receptor ligand binding, chimeric adenosine receptors consisting of bovine A1AR and rat A3AR sequence were constructed. As these two AR subtypes differ markedly in agonist and especially antagonist binding, it was reasoned that binding alterations induced by substitution of distinct receptor regions may be more readily apparent and directly attributable to one or the other subtypes. The ligand binding properties of these chimeric receptors were studied following their transient expression in COS-7 cells. The ligand binding parameters of WT bovine A1AR, WT rat A3AR, and the first series of chimeric receptors examined are shown in Table I. The first set of constructs consisted primarily of A1AR sequence with substitution by limited regions of A3AR structure. Replacement of transmembrane domains 3 (A1-T3) or 5 (A1-T5IL3) of the A1AR with those of the A3AR, separately or in combination (A1-T35IL3), did not disrupt antagonist or agonist binding as compared to the WT A1AR. Specifically, Kd values obtained from [3H]DPCPX binding were similar for chimeric receptors A1-T3, A1-T5IL3, A1-T35IL3, and the WT A1AR. Inasmuch as the [3H]DPCPX data clearly demonstrate that these chimeric receptors can bind antagonist in a manner nearly identical to the WT A1AR, their properties were not further examined in competition assays. The high affinity binding of the antagonist radioligand by this set of chimeras indicates that TM 3 and 5 of the A3AR do not specifically inhibit antagonist binding as substitution of these regions into the A1AR with those of the xanthine-insensitive A3AR did not disrupt antagonist binding. These chimeric receptors also displayed high affinity agonist binding with some minor variations. In competition for [125I]AB-MECA binding, Ki values of less than or near 1 nm for R-PIA were obtained for the WT A1AR and chimeric receptors. A1-T3 displayed slightly lower affinity for 5′-substituted agonists ([125I]AB-MECA and NECA) than the WT A1AR or A1-T5IL3 and A1-T35IL3.

Table I.

Ligand binding parameters of WT A1AR and WT A3AR and A1/A3 chimeric receptors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECEPTOR | WT A1AR | WT A3AR | A1-T3 | A1-T5IL3 | A1-T35IL3 | A1-T345 | A3-T67 |

| Bmaxa | 1.20 ± 0.48d | 1.82 ± 0.70d | 14.0 ± 4.0 | 0.53 ± 0.03 | 16.5 ± 5.0 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.04 |

| [125I]AB-MECAb | 0.59 ± 0.18d | 1.22 ± 0.22d | 2.60 ± 0.12 | 0.71 ± 0.07 | 0.30 ± 0.09 | 1.12 ± 0.12 | 0.42 ± 0.02 |

| [3H]DPCPXb | 0.46 ± 0.03 | e | 1.98 ± 0.61 | 1.04 ± 0.32 | 0.72 ± 0.05 | e | e |

| R-PIAc | 0.22 ± 0.04d | 225.0 ± 31.8d | 0.65 ± 0.18 | 1.81 ± 0.21 | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 11.5 ± 3.7 | 6.88 ± 0.99 |

| NECAc | 16.1 ± 6.1d | 233.0 ± 35.0d | 48.7 ± 21.7 | 2.00 ± 0.35 | 11.3 ± 1.7 | 111.8 ± 30.0 | 43.3 ± 7.2 |

| XACc | 2.37 ± 0.31 | 18.5 ± 4.1%f | ND | ND | ND | 25.2 ± 9.0%e | 1380 ± 23 |

| DPCPXc | 1.15 ± 0.14 | 23.0 ± 2.0%f | ND | ND | ND | ND | 966.5 ± 223.0 |

| BW-A1433c | 1.66 ± 0.19 | 38.0 ± 8.5%f | ND | ND | ND | ND | 712.3 ± 292.0 |

Table shows mean ± standard error of three to six determinations. ND, not determined.

Obtained from [125I]AB-MECA saturation binding (pmol/mg).

Kd (nm) values obtained from saturation binding analysis.

Ki (nm) values obtained from competition for [125I]AB-MECA binding.

From Ref. 21.

No specific binding for [3H]DPCPX observed.

Represents % inhibition of [125I]AB-MECA binding at 10 mm competitor.

The chimeric receptor A1-T345, consisting of TM 3–5 and connecting regions of the A3AR substituted into the A1AR, displayed binding properties substantially different than those described for the previous constructs (Table I). Binding of [125I]AB-MECA was of high affinity (Kd = 1.1 nm); however, the binding of R-PIA by A1-T345 (Kd = ~11 nm) was intermediate between the WT A1AR (0.22 nm) and WT A3AR (225 nm). Significantly, A1-T345 did not demonstrate any specific binding of the xanthine radioligands, [3H]XAC and [3H]DPCPX. Furthermore, XAC at a concentration of 10 μm displaced only ~25% of [125I]AB-MECA binding from A1-T345. This marked lack of antagonist binding by A1-T345 is characteristic of that displayed by the WT rat A3AR, suggesting that those regions of A3AR sequence present in A1-T345 may have a role in antagonist recognition by ARs.

As A1-T345 demonstrated agonist affinity intermediate between that of the WT A1AR and WT A3AR, it was reasoned that TM 1, 2, 6, or 7 of the A1AR confers upon the WT A3AR an enhanced R-PIA (~20-fold) and NECA (~2-fold) affinity. The role of these regions was further explored in chimeric receptor A3-T67, in which TM 6 and 7 of the A3AR were replaced with those of the A1AR. As shown in the schematic in Table I, A3-T67 also contained the adjoining regions, extracellular loop 3 and carboxyl-terminal tail, of the A1AR. This chimeric receptor demonstrated high affinity [125I]AB-MECA binding (Kd = 0.42 nm). As observed for A1-T345, R-PIA affinity (Ki = 6.9 nm) and NECA affinity (Ki = 43 nm) were greater than that typical of the WT A3AR though not enhanced to the level of the WT A1AR. These findings suggest that elements of TM 6 or 7 or adjoining regions are involved in agonist binding and that interactions in these regions may be more favorable at the WT A1AR than WT A3AR. The binding of antagonists by A3-T67 was explored by determining the ability of various xanthine analogs to displace [125I]AB-MECA binding. XAC, DPCPX, and BW-A1433 demonstrated weak affinity (Ki values of ~0.7–1.4 μm) at A3-T67. This affinity, though nearly 1000-fold lower than that typical of the WT A1AR, is distinctly higher than that displayed by the WT rat A3AR. Thus, TM 6 or 7 or adjoining regions must participate in antagonist recognition and the presence of these regions of the A1AR in a chimeric receptor consisting primarily of A3AR sequence can impart a degree of antagonist binding on the receptor.

Chimeric receptors A1-T345 and A3-T67 suggest that although TM 6 and 7 of ARs have a role in antagonist recognition, elements of TM 3,4, or 5 or adjoining regions of the A1AR may be critical for high affinity antagonist binding. However, the ability of A1-T3, A1-T5IL3, and A1-T35IL3 to bind [3H]DPCPX with high affinity indicates that TM 3 and 5 are not specifically involved. Thus, two additional chimeric receptors, A3-T4 and A3-T4EL2, were constructed to examine the roles of transmembrane domain 4 and extracellular loop 2 of ARs in ligand binding. It is important to note that amino acids in the exofacial half of TM 4 of the WT A1AR and WT A3AR are identical (Fig. 1). Thus, replacement of amino acids in TM 4 of the A3AR with the analogous residues of the A1AR was limited to the cytoplasmic half of TM 4. The chimeric receptor A3-T4EL2 contains TM 4, as well as the adjoining intracellular loop 2 and extracellular loop 2 of the A1AR substituted into the A3AR. The binding properties of these two chimeric receptors are shown in Table II. A3-T4 binds [125I]AB-MECA in saturation analysis and R-PIA and NECA in [125I]AB-MECA competition experiments with properties identical to those of the WT A3AR. Furthermore, 10 μm XAC displaced only ~30% of [125I]AB-MECA binding, which is also characteristic of the WT A3AR. Very different binding properties were displayed by the chimeric receptor A3-T4EL2. [125I]AB-MECA binding was again of high affinity (Kd = 0.5 nm). Additionally, as assessed by Ki values, R-PIA and NECA were approximately 45- and 10-fold, respectively, more potent at A3-T4EL2 than at either the WT A3AR or A3-T4. The amino acid substitutions present in A3-T4EL2 also resulted in a chimeric receptor displaying relatively high affinity antagonist binding. In competition assays, Ki values of approximately 50, 70, and 300 nm were obtained for XAC, BW-A1433, and DPCPX, respectively. Thus, data from these two chimeric receptors further define the ligand binding pocket of ARs. Substitution of TM 4 of the A3AR with that of the A1AR had negligible effect on agonist or antagonist binding by the receptor. However, the simultaneous replacement of TM 4 with the adjoining second intracellular loop and second extracellular loop of the A3AR with analogous regions of the A1AR resulted in a chimeric receptor demonstrating relatively high affinity antagonist binding while consisting primarily of A3AR sequence. This substitution also resulted in enhanced agonist affinity as observed in R-PIA and NECA competition assays.

Table II.

Ligand binding parameters of A3/A1 chimeric receptors focusing on TM 4 and extracellular loop 2

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECEPTOR | A3-T4 | A3-T4EL2 | A3-T467 | A3-T467EL2 |

| Bmaxa | 1.98 ± 0.40 | 1.02 ± 0.35 | 0.96 ± 0.33 | 2.46 ± 0.28 |

| [125I]AB-MECAb | 1.05 ± 0.20 | 0.50 ± 0.08 | 0.50 ± 0.16 | 0.39 ± 0.10 |

| [3H]DPCPXb | d | d | d | 2.92 ± 0.40 |

| R-PIAc | 218.7 ± 54.3 | 4.80 ± 0.20 | 7.11 ± 1.10 | 0.60 ± 0.13 |

| NECAc | 248.5 ± 61.5 | 19.9 ± 2.1 | 45.9 ± 6.9 | 2.93 ± 1.20 |

| XACc | 18.7 ± 9.5%e | 53.4 ± 10.4 | 733.0 ± 142.0 | 2.69 ± 0.30 |

| DPCPXc | ND | 303.0 ± 55.0 | 375.7 ± 115.4 | 2.39 ± 0.42 |

| BW-A1433c | ND | 70.2 ± 13.7 | 333.0 ± 52.2 | 5.58 ± 0.29 |

Table shows mean ± standard error of three to four determinations. ND, not determined.

Obtained from [125I]AB-MECA saturation binding (pmol/mg).

Kd (nm) values obtained from saturation binding analysis.

Ki (nm) values obtained from competition for [125I]AB-MECA binding.

No specific binding for [3H]DPCPX observed.

Represents % inhibition of [125I]AB-MECA binding at 10 μm competitor.

As compared to WT A3AR, the substitution of two different receptor regions to create chimeric receptors A3-T67 and A3-T4EL2 each resulted in similar increases in agonist affinity. The increase, though marked, did not result in binding affinity equivalent to that of the A1AR. Likewise, A3-T67 and A3-T4EL2 both displayed higher affinity for antagonists than the WT A3AR. This effect was much more dramatic for A3-T4EL2, although again affinity remained ~50-fold less than that typical of WT A1AR. Based on these findings, it was reasoned that the distinct receptor regions identified in A3-T67 and A3-T4EL2 each have a role in ligand recognition by ARs. To examine this possibility, additional chimeric receptors were constructed in which TM 6 and 7 of the A1AR, i.e. that region constituting A3-T67, were substituted into the chimeric receptors A3-T4 and A3-T4EL2 to create A3-T467 and A3-T467EL2, respectively. The data are presented in Table II. Agonist (R-PIA and NECA) binding in A3-T467 was similar to that displayed by the A3-T67 parent receptor. Antagonist affinity, as assessed by competition for [125I]AB-MECA binding was ~2–3-fold higher at A3-T467 than at A3-T67. Increases in affinity for agonists and antagonists were much more dramatic for the chimeric receptor A3-T467EL2. In competition assays, Ki, values for R-PIA and NECA were 0.6 and 2.9 nm, respectively. Furthermore, affinity of A3-T467EL2 for antagonists was equivalent to that characteristic of the WT A1AR. Ki, values of 2.7, 2.4, and 5.6 nm were obtained for XAC, DPCPX, and BW-A1433, respectively, in competition assays. Affinity of this magnitude permitted [3H] DPCPX saturation binding experiments to be performed. Binding of [3H]DPCPX to A3-T467EL2 was saturable and of high affinity (Kd = 2.9 nm). This chimeric receptor, although composed primarily of A3AR sequence, is characterized by [3H] DPCPX affinity only 6-fold lower than that of the WT A1AR, while in competition assays the binding profiles of A3-T467EL2 and WT A1AR are even more similar. These data also indicate that multiple regions of AR sequence are involved in both agonist and antagonist recognition.

Data obtained with chimeric receptors A3-T4EL2 and A3-T467EL2 suggest that a region of AR sequence including TM 4 and extracellular loop 2 is involved in ligand binding. However, in that chimeric receptor A3-T4 displays properties identical to those of the WT A3AR, subsequent analysis focused on the role of extracellular loop 2 sequence in those A3AR chimeras displaying markedly enhanced agonist and antagonist affinities. Chimeras consisting of predominately A3AR sequence with substitution of the entire extracellular loop 2 (A3-EL2), proximal region (A3-EL2A, 9 amino acids), or distal region (A3-EL2B, 11 amino acids) of the loop were constructed. It should be noted that the putative extracellular loop of the A1AR is approximately 6 amino acid residues longer than that of the A3AR (Fig. 1). To create A3-EL2A and A3-EL2B, amino acids of the A3AR were replaced with those of the A1AR thus maintaining the length of the WT A3AR loop. Substitution of the entire loop or the distal portion of the loop was performed individually (A3-EL2, A3-EL2A, and A3-EL2B) or in combination with TM 6 and 7 of the A1AR (A3-T67EL2 and A3-T67EL2B). Results obtained with these five chimeric receptors are shown in Table III. Substitution of the entire second extracellular loop of the A1AR into A3AR sequence (A3-EL2) resulted in a pharmacologic profile identical to that of chimeric A3-T4EL2. R-PIA and NECA affinities were significantly greater than that of WT A3AR. XAC, DPCPX, and BW-A1433 displayed Ki values of 80, 395, and 110 nm, respectively, in competition binding assays. The region of the second extracellular loop of the A1AR conferring this increased affinity of agonists and antagonists was examined in chimeric receptors A3-EL2A and A3-EL2B. Data from both chimeras indicate that these properties were due solely to replacement of amino acids located in the carboxyl-terminal region of this area, i.e. the segment immediately preceding TM 5. A3-EL2A bound agonists and antagonists in a fashion identical to WT A3AR. However, properties displayed by those chimeras containing the entire second extracellular loop of the A3AR, A3-T4EL2, and A3-EL2 were also observed with A3-EL2B. Thus, R-PIA and NECA were of ~40-fold greater affinity at A3-EL2B than at the WT A3AR. The antagonists, XAC and BW-A1433, displayed Ki values of 111 and 88.4 nm, respectively, at A3-EL2B. DPCPX (Ki = 1120 nm) was ~3-fold less potent at A3-EL2B than at A3-EL2, yet this affinity remained significantly greater than that of WT A3AR.

Table III.

Ligand binding parameters for A3/A1 chimeric receptors focusing on regions of extracellular loop 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECEPTOR | A3-EL2 | A3-EL2A | A3-EL2B | A3-T67EL2 | A3-T67EL2B |

| Bmaxa | 2.20 ± 0.75 | 1.11 ± 0.25 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 2.20 ± 0.60 | 0.24 ± 0.05 |

| [125I]AB-MECAb | 0.28 ± 0.09 | 1.10 ± 0.22 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.49 ± 0.06 |

| [3H]DPCPXb | d | d | d | 3.51 ± 0.30 | 7.71 ± 0.86 |

| R-PIAc | 7.90 ± 3.3 | 130.5 ± 65.2 | 6.14 ± 1.26 | 0.48 ± 0.05 | 0.77 ± 0.06 |

| NECAc | 7.82 ± 1.0 | ND | 6.70 ± 0.87 | 1.71 ± 0.03 | 1.90 ± 0.07 |

| XACc | 80.4 ± 26.4 | 24.2 ± 6.0%e | 111.1 ± 10.1 | 3.33 ± 0.60 | 5.07 ± 1.21 |

| DPCPXc | 395.4 ± 54.7 | ND | 1116 ± 194 | ND | ND |

| BW-A1433c | 109.9 ± 4.9 | ND | 88.4 ± 11.1 | ND | ND |

Table shows mean ± standard error of three to four determinations. ND, not determined.

Obtained from [125I]AB-MECA saturation binding (pmol/mg).

Kd (nm) values obtained from saturation binding analysis.

Ki (nm) values obtained from competition for [125I]AB-MECA binding.

No specific binding for [3H]DPCPX observed.

Represents % inhibition of [125I]AB-MECA binding at 10 μm competitor.

These findings detail the role of extracellular loop 2 and specifically amino acids in the distal region of this segment in agonist and antagonist binding by ARs. Furthermore, previous data indicate amino acids identified in chimeric receptor A3-T67 also constitute a portion of the AR ligand binding pocket. The distinct contributions of these two discrete regions was confirmed in the last two chimeric receptors examined, A3-T67EL2 and A3-T67EL2B. Both of these chimeras bound agonists with extremely high affinity. In fact, A3-T67EL2 and A3-T67EL2B displayed the highest affinities for NECA of any wild-type or chimeric receptor presently studied. Binding of R-PIA by these chimeras also approached that of the WT A1AR with Ki values of less than 1 nm. Again, with both of these chimeras, antagonist binding in competition assays was nearly identical to that of the WT A1AR, with Ki values for XAC of 3.3 and 5.1 nm for A3-T67EL2 and A3-T67EL2B, respectively. The enhancement of antagonist binding provided by substitution of the two distinct regions was such that [3H]DPCPX saturation assays could be performed. A3-T67EL2 and A3-T67EL2B displayed Kd values of 3.5 and 7.7 nm, respectively, for [3H]DPCPX.

DISCUSSION

The present study, an analysis of A1/A3 chimeric adenosine receptors, provides several substantial insights into the regions of ARs involved in ligand recognition. Perhaps the most significant finding is that amino acids in the distal portion of the second extracellular loop play a crucial role in ligand binding. Additionally, a region encompassing TM 6 through TM 7 is significantly involved in formation of the ligand binding pocket. Substitution of either or both of these regions has marked effects on both agonist and antagonist ligands. It is also apparent that the binding pockets for both classes of ligands have considerable overlap. Other than a report on the role of histidine residues in TM 6 and 7 of the A1AR (7), the present study provides the first description of AR regions involved in antagonist binding. The conclusions obtained from this study are supported by the results obtained through the analysis of several chimeric receptors. Importantly, findings are interpreted with respect to a “gain of function.” Through the replacement of discrete A3AR regions with the analogous segments of the A1AR, chimeric receptors were created that displayed enhanced affinity for ligands. Such findings are more interpretable than a loss of binding affinity, which may result from alterations in receptor structure not directly pertaining to ligand recognition functions. Despite the identification of discrete AR regions substantially involved in ligand recognition in this study, this analysis does not completely define the AR ligand binding pocket. As described below and as is inherent in all chimeric receptor studies, the precise individual amino acids that interact with the ligand are not presently defined.

Results with chimeric receptors A3-T4EL2, A3-T467EL2, A3-EL2, and A3-T67EL2 all indicate a role for the second extracellular loop in both agonist and antagonist binding. Furthermore, chimeric receptors A3-EL2B and A3-T67EL2B specifically identify 11 amino acids at the carboxyl end of this loop as being involved. A chimeric receptor containing replacement of 9 amino acids of the amino terminus of extracellular loop 2 of the A3AR with those of the A1AR (A3-EL2A) was identical to WT A3AR in all parameters examined. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing marked enhancement of ligand recognition resulting from the mutation of solely an extracellular region of a receptor involved in the binding of a small neurotransmitter compound such as adenosine. Extensive site-directed mutagenesis studies of the β-adrenergic (reviewed in Ref. 27), α-adrenergic (28,29), muscarinic (30,31), dopaminergic (32, 33), and serotonin (34, 35) receptors, for example, have reported on the involvement of membrane-spanning domains of the receptor in ligand binding. Extracellular regions of G protein-coupled receptors have been implicated in ligand recognition; however, the endogenous agonists for these receptors are typically peptides such as the endothelins (36) or tachykinins (37–40) or glycoprotein hormones (41, 42). The wild-type rat A3AR is distinguished from all other AR subtypes based on its very low affinity for xanthine derivatives (16). The sheep (17) and human (18) A3ARs display moderate affinity for certain xanthines such as XAC (Ki ~ 100 nm). The substitution of the distal region of the second extracellular loop of rat A3AR with A1AR sequence resulted in a chimeric receptor (A3-EL2B) displaying affinities for XAC, DPCPX, and BW-A1433 nearly identical to those reported for the cloned human A3AR (18). Although the similarity in affinities may be fortuitous, it is interesting to note that certain amino acids in this region of the bovine A1AR that are not present in the rat A3AR are conserved in the human A3AR. Presently, the precise involvement of the identified 11 residue segment of the second extracellular loop cannot be defined. An obvious possibility is that an amino acid(s) in this region directly interacts with ligands thus coordinating the molecule to the receptor. Second, this region may contribute to the overall physical architecture of the receptor protein and thus influence the conformation of the ligand binding pocket and the amino acids which do directly interact with ligand. Presently, it may be speculated that it is not the ligand directly interacting with the second extracellular loop that is responsible for the enhancement of ligand affinity in several A3/A1 chimeric receptors as the effect was observed for agonists of different categories (R-PIA and NECA) and for xanthine antagonists containing distinct substitutions (XAC, a primary amine and BW-A1433, a carboxylic acid). However, as discussed below, models of ligand-AR binding do indicate considerable overlap in agonist and antagonist orientations in the receptor binding pocket (43, 44). Huang and co-workers (39) in study of mutant tachykinin receptors have also noted the difficulty involved in assigning direct or indirect roles for extracellular regions in ligand binding.

Of the 11 amino acids identified in the loop region, 3 are conserved between the bovine A1AR and rat A3AR. Interestingly, 1 of these is a cysteine residue that has been hypothesized to be involved in disulfide bond formation in ARs (45). In that this cysteine is conserved in an analogous site in all AR subtypes, including those presently studied, it is unlikely that altered disulfide bond formation is responsible for the observed effects. A second post-translational modification of G protein-coupled receptors is N-linked glycosylation of extracellular regions (27). However, an acceptor asparagine residue is not present in either the WT A1AR or WT A3AR in the analyzed segment.

It is possible that the effects of the second extracellular loop are reflected in the orientation of the fifth transmembrane domain of ARs, and the conformation of this region may be involved in formation of the ligand binding pocket. The present study (chimeric receptor A1-T5IL3) suggests that TM 5 of ARs is not directly involved in antagonist recognition. Previous work further indicated no role for amino acids in the exofacial half of this region in DPCPX binding (21). However, in both of these studies, the chimeric receptors that were employed were composed of TM 5 structure of the A3AR in combination with extracellular loop 2 of the A1AR. Thus, the influence of the second extracellular loop of the A1AR on orientation of TM 5 remained intact.

The findings with several chimeric receptors characterized in this study indicate a role for the region spanning from TM 6 through the carboxyl-terminal tail in ligand binding. The substitution of this region of the A1AR into the A3AR (chimeric receptor A3-T67) produced ~30- and 6-fold increases in the affinity for R-PIA and NECA, respectively. As reflected in Ki values for XAC, DPCPX, and BW-A1433, this substitution also resulted in enhanced affinities for antagonists. Because of the inability to obtain valid Ki values for antagonists at the WT A3AR, the -fold increase in affinities cannot be precisely stated, although it may be estimated at 20–100-fold. Furthermore, this substitution, when made simultaneously with replacement of regions encompassing the distal portion of extracellular loop 2, resulted in further enhancements of binding affinities, permitting [3H]DPCPX saturation analysis of chimeric receptors containing predominantly A3AR sequence (e.g. A3-T67EL2B). The amino acids responsible for this effect cannot be identified. Replacement of the histidine residues in TM 6 and 7 of the bovine A1AR with leucines resulted in a decrease in antagonist affinity and complete loss of agonist and antagonist binding, respectively (7). However, neither of these residues can be directly associated with the effects of the substitutions performed in the present study. The histidine in TM 7 is conserved in all AR subtypes thus far cloned including the rat A3AR. Site-directed mutagenesis of the rat A3AR to replace a serine with a histidine in TM 6 (as in all A1ARs and A2ARs) had no effect on agonist or antagonist binding by the receptor.2 A recent study also demonstrated a role for threonine at position 277 (TM 7) of the human A1AR in NECA binding (20). However, the mutation of this threonine to alanine did not disrupt [3H]DPCPX or R-PIA binding. Furthermore, replacement of the threonine to serine (the natural amino acid in the analogous position of the bovine A1AR and rat A3AR) did not have marked effects on the affinity of any ligand examined (20). Again, it is possible that the effects of substitution of this region may also be a result of alterations in overall receptor conformation thus making assignment of individual amino acid function difficult.

The effects of replacement of extracellular loop 2 and the distal regions of the A1AR on agonist and antagonist binding suggest that multiple receptor regions form the ligand binding pocket and that there is significant overlap in the regions recognizing both classes of ligands. Although there may be some variations in the fold enhancement of affinity, no amino acid substitution performed in the present analysis resulted in a selective increase in the binding of agonists versus antagonists or vice versa. Computer models of AR-ligand binding data generated by two groups (43,44) employ conformations of N6-substituted agonists and C8-substituted xanthine antagonists in which the ligands obtain a similar orientation in the hypothetical ligand binding pocket. In this “N6-C8” model, the N6- and C8-groups of agonists and antagonists, respectively, would be nearly superimposable (43, 44). The adenine and xanthine rings would also display some overlap in this orientation. Based on these models, it is possible that the conformation of the binding pocket, as well as certain amino acid-ligand interactions, may be similar for agonists and antagonists. However, as discussed above, previous site-directed mutagenesis studies of A1ARs have discriminated between residues required for agonist and antagonist recognition (7, 20, 21). It is expected that differences must exist between interactions for the two classes of ligands as agonists are fundamentally assumed to induce a conformational change in receptor structure permitting G protein interaction, an effect that cannot be obtained upon antagonist binding. The generation of unique peptide maps upon proteolytic digestion of native bovine A1AR following either agonist or antagonist occupation supports this concept (46).

In summary, multiple regions of ARs appear to be involved in ligand recognition with overlap of the agonist and antagonist binding pockets. Future mutagenesis studies of these regions and those of the A2AR subtypes should further define the structural requirements of AR-ligand binding.

Acknowledgment

We thank Mary Pound for technical assistance.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The abbreviations and trivial names used are: AR, adenosine receptor; TM, transmembrane domain(s); WT, wild-type; R-PIA, (–)-N6-(R-phenylisopropy1)adenosine; NECA, 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine; DPCPX, 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine; XAC, xanthine amine congener; [125I]AB-MECA, N6-(3-[125I]iodo-4-aminobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine; BW-A1433, 1,3-dipropyl-8-(4-acrylate)phenylxanthine; CHAPS, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propane-sulfonate.

M. Olah, unpublished results.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olsson RA, Pearson JD. Physiol. Rev. 1990;70:761–845. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.3.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudolphi KA, Schubert P, Parkinson FE, Fredholm BB. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1992;13:439–445. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90141-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaven MA, Ramkumar V, Ali H. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1994;15:13–14. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Libert F, Schiffmann SN, Lefort A, Parmentier M, Gerard C, Dumont JE, Vanderhaegen J-J, Vassart G. EMBO J. 1991;10:1677–1682. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahan LC, McVittie LD, Smyk-Randall EM, Nakata H, Monsma FJ, Jr., Gerfen CR, Sibley DR. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991;40:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reppert SM, Weaver DR, Stehle JH, Rivkees SA. Mol. Endocrinol. 1991;5:1037–1048. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-8-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olah ME, Ren H, Ostrowski J, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:10764–10770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker AL, Linden J, Robeva AS, D'Angelo DD, Lynch KR. FEBS Lett. 1992;297:107–111. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80338-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libert F, Van Sande J, Lefort A, Czernilofsky A, Dumont JE, Vassart G, Ensinger HA, Mendla KD. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;187:919–926. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Townsend-Nicholson A, Shine J. Mol. Brain Res. 1992;16:365–370. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90248-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maenhaut C, Van Sande J, Libert F, Abramowicz M, Parmentier M, Vanderhaegen J-J, Dumont JE, Vassart G, Schiffmann S. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;173:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80909-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink JS, Weaver DR, Rivkees SA, Peterfreund R, Pollack A, Adler E, Reppert SM. Mol. Brain Res. 1992;14:186–195. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furlong TJ, Pierce KD, Selbie LA, Shine J. Mol. Brain Res. 1992;15:62–66. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stehle JH, Rivkees SA, Lee JJ, Weaver DR, Deeds JD, Reppert SM. Mol. Endocrinol. 1992;6:384–393. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.3.1584214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierce KD, Furlong TJ, Selbie LA, Shine J. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;187:86–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Q-Y, Li C, Olah ME, Johnson RA, Stiles GL, Civelli O. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:7432–7436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linden J, Taylor HE, Robeva AS, Tucker AL, Stehle JH, Rivkees SA, Fink JS, Reppert SM. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;44:524–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvatore CA, Jacobson MA, Taylor HE, Linden J, Johnson RG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:10365–10369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klotz K-N, Lohse MJ, Schwabe U. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:17522–17526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Townsend-Nicholson A, Schofield PR. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:2373–2376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olah ME, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:18016–18020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwabe V, Ukena D, Lohse MJ. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1985;330:212–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00572436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olah ME, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:978–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cullen BR. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:684–704. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeLean A, Hancock AA, Lefkowitz RJ. Mol. Pharmacol. 1982;21:5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostrowski J, Kjelsberg MA, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1992;32:167–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.32.040192.001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suryanarayana S, Daunt DA, Von Zastrow M, Kobilka BK. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:15488–15492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C-D, Buck MA, Fraser CM. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991;40:168–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wess J, Gdula D, Brann MR. EMBO J. 1991;10:3729–3734. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wess J, Nanavati S, Vogel Z, Maggio R. EMBO J. 1993;12:331–338. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollock NJ, Manelli AM, Hutchins CW, Steffey ME, MacKenzie RG, Frail DE. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:17780–17786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacKenzie RG, Steffey ME, Manelli AM, Pollock NJ, Frail DE, Frail DE. FEBS Lett. 1993;323:59–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guan X-M, Peroutka SJ, Kobilka BK. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;41:695–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choudhary MS, Craigo S, Roth BL. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;42:627–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakamoto A, Yanagisawa M, Sawamura T, Enoki T, Ohtani T, Sakurai T, Nakao K, Toyo-oka T, Masaki T. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:8547–8553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fong TM, Huang R-RC, Strader CD. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:25664–25667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fong TM, Yu H, Huang R-R, C., Strader CD. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11806–11811. doi: 10.1021/bi00162a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang R-RC, Yu H, Strader CD, Fong TM. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:690–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gether U, Edmonds-Alt X, Breliere J-C, Fujii T, Hagiwara D, Pradier L, Garret C, Johansen TE, Schwartz TW. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:500–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagayama Y, Wadsworth HL, Chazenbalk GD, Russo D, Seto P, Rapoport B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A. 1991;88:902–905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie Y-B, Wang H, Segaloff DL. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:21411–21414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.IJzerman AP, van Galen PJM, Jacobson KA. Drug Design Discovery. 1992;9:49–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dudley MW, Peet NP, Demeter DA, Weintraub HJR, IJzerman AP, Nordvall G, van Galen PJM, Jacobson KA. Drug Dev. Res. 1993;28:237–243. doi: 10.1002/ddr.430280309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Galen PJM, Stiles GL, Michaels G, Jacobson KA. Med. Res. Rev. 1992;12:423–471. doi: 10.1002/med.2610120502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barrington WW, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:13157–13164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]