Abstract

Objective

To review the barriers to the uptake of research evidence from systematic reviews by decision makers.

Search strategy

We searched 19 databases covering the full range of publication years, utilised three search engines and also personally contacted investigators. Reference lists of primary studies and related reviews were also consulted.

Selection criteria

Studies were included if they reported on the views and perceptions of decision makers on the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews, meta-analyses and the databases associated with them. All study designs, settings and decision makers were included. One investigator screened titles to identify candidate articles then two reviewers independently assessed the quality and the relevance of retrieved reports.

Data extraction

Two reviewers described the methods of included studies and extracted data that were summarised in tables and then analysed. Using a pre-established taxonomy, the barriers were organised into a framework according to their effect on knowledge, attitudes or behaviour.

Results

Of 1726 articles initially identified, we selected 27 unique published studies describing at least one barrier to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews. These studies included a total of 25 surveys and 2 qualitative studies. Overall, the majority of participants (n=10 218) were physicians (64%). The most commonly investigated barriers were lack of use (14/25), lack of awareness (12/25), lack of access (11/25), lack of familiarity (7/25), lack of usefulness (7/25), lack of motivation (4/25) and external barriers (5/25).

Conclusions

This systematic review reveals that strategies to improve the uptake of evidence from reviews and meta-analyses will need to overcome a wide variety of obstacles. Our review describes the reasons why knowledge users, especially physicians, do not call on systematic reviews. This study can inform future approaches to enhancing systematic review uptake and also suggests potential avenues for future investigation.

Article summary.

Article focus

The aim was to identify the barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews.

The identified barriers to the use of evidence from systematic reviews varied.

The most salient barriers were lack of use, lack of awareness, limited access, lack of familiarity, lack of perceived usefulness and external barriers.

The review reveals why decision makers do not use systematic reviews.

Interventions to foster uptake of systematic reviews need to address a broad range of factors.

The study offers a rational approach towards improving systematic review uptake and also a framework for future research.

Key messages

While access is improving, impaired access whether real or perceived, is still a significant barrier.

Lack of first-time use is preventing generalisation and expansion of systematic review uptake in everyday practice.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this study was the extensive, systematic literature search.

A limitation was that included surveys asked closed-ended questions where the barriers investigated depended on investigator preference.

Introduction

Many researchers are worried about the extent to which research knowledge is utilised.1 An important finding from health research is the limited success in routinely transferring research knowledge into clinical practice. Tackling the knowledge-to-practice deficit is challenging and entails an investigation of the numerous obstacles to knowledge uptake.2

The transfer of important clinical knowledge is impeded by the amount and also the ongoing growth of the biomedical literature. Systematic reviews diminish this problem. A systematic review is a review of ‘a clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect and analyse data from studies that are included in the review’.3 The contribution of systematic reviews to the research literature is seen in a range of bibliographic databases such as the Cochrane Library.

A systematic review that integrates the findings of discrete studies against the background of global evidence can be considered the basic unit of evidence transfer.4 Synthesis should help with policy formulation, the development of clinical practice guidelines, as well as informing routine decision-making in clinical practice. Failure to use the findings from systematic reviews and meta-analyses can reduce healthcare efficiency and compromise quality of life.

However, the mere existence of reviews does not ensure their dissemination and their application to routine practice and policy formulation. The uptake of evidence from systematic reviews has been inconsistent.4 When unsure about diagnostic and management issues, physicians routinely consult with a colleague or read a text.5

While many investigations have been conducted on the barriers to the uptake of research evidence in general, little is known specifically about the determinants of uptake of systematic review evidence in particular. In the past, there have been reviews of the barriers to adherence to clinical guidelines,6 of the barriers to the appropriate use of research evidence in policy decisions,1 of the barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making,7 of the barriers to improving the usefulness of systematic reviews for healthcare managers and policy makers8 and lastly, of the barriers and incentives to optimal healthcare.9

Systematic reviews were the focus of this investigation, rather than the more commonly investigated clinical practice guidelines or indeed individual, primary studies. Systematic reviews are based on primary research while clinical practice guidelines are an amalgam of clinical experience, expert opinion, patient preferences and evidence. Systematic reviews are a scientific exercise aimed at generating new knowledge and they provide a summary of relevant primary research. In this way, they can help keep us current. Systematic reviews have a distinct development and scientific purpose that differs from both guidelines and primary research.

Many factors contribute to the varying uptake of evidence in general.10 These include financial obstacles, the sheer volume of research evidence, and the difficulties in applying global evidence in a local clinical context.11 Other barriers include limited time and impaired awareness of evidence sources, limited critical appraisal skills and the limited relevance of research findings.12 Given the considerable differences between systematic reviews, primary research and clinical practice guidelines, we set out specifically to identify the barriers to uptake of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

What are the barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews, meta-analyses and the databases that contain them? Here we were concerned with all decision makers, including physicians, policy makers, patients and nursing staff. Such barrier identification can aid the development of effective strategies to improve the uptake of systematic reviews and meta-analyses by decision makers. Interventions to improve the use of systematic reviews for clinical and commissioning decision-making are currently being investigated.11

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify barriers to evidence uptake from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The primary researcher (JW) searched 19 databases and used 3 search engines, for articles, not limited to the English language, drawing on the entire range of publication years covered in each database up to December 2010 using a combination of index terms and text words identified from previously identified, relevant articles. The databases included the Cochrane Library, TRIP, Joanna Briggs Institute, National Guideline Clearing House, Health Evidence, PubMed (1950–2010), EMBASE (1980–2010), ERIC, CINAHL, PsycInfo, OpenSigle, Index to Theses in Great Britain and Ireland and Conference Papers Index, and also include Campbell Collaboration, Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, EPOC, KT+, McMaster University, Keenan Research Centre and the New York Academy of Medicine. The search engines ALTA VISTA and Google scholar were also utilised. References from included primary studies and related review articles were scanned, experts in the field contacted and bibliographies of textbooks were reviewed. The following search terms were included: obstacle, barrier, impede, utilisation, uptake, systematic review and meta-analysis.

We repeated aspects of the search for the period December 2010–June 2012. The aim was to identify any further relevant or on-going studies to be included in ‘Studies awaiting classification’ or ‘On-going studies’ that could be used in a later update of this systematic review. We applied similar search strategies to PubMed and EMBASE, the two most productive bibliographic databases in terms of studies already identified for inclusion in the review.

Selection criteria

We included studies if they presented an original collection of data. Studies containing interviews, focus groups and surveys with all decision makers, such as doctors, nurses, occupational therapists, policy makers and patients, were eligible. Selection criteria did not specify that the inclusion of studies was restricted to those reporting, as their main purpose, the identification of obstacles specifically to systematic review uptake. No study design or language was excluded. Studies were included if they addressed perceived barriers to the uptake of evidence specifically from systematic reviews, meta-analyses and databases that contained them such as the Cochrane Library, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database, Oxford Database of Perinatal Trials and the Reproductive Health Library.

A barrier was defined as any factor that impedes or obstructs the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews. Barriers to evidence uptake can negatively impact on access, awareness, familiarity, intellectual adoption and actual use of systematic reviews. Barriers can also limit the positive influence of current systematic review results on patient care. We focused on factors that could be altered or overcome rather than the gender or age of decision makers.6 In many of the reports, participants specified obstacles via response to survey questions. For qualitative studies, major themes from focus groups or interviews identified the obstacles to uptake.12

Special care was taken to identify studies that appeared in multiple publications.13 When more than one report described a specific study and each presented the same data, then the most recent publication was included for analysis. However, if more than one publication described a single investigation but each presented novel and complementary evidence then both were utilised.

Data collection and analysis

Reports were retrieved if it appeared likely that they contained data regarding barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews. The first reviewer reviewed all the citations, and followed up reference lists, while the retrieved full reports were assessed by at least two reviewers (JW and BN) for inclusion in the review. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, or adjudication by a third party (MC). Reports appearing relevant initially, but which were not, joined a list of excluded studies maintained by the author (JW).

Using a data collection form, two reviewers (JW and BN) extracted data from the included studies. Information extracted from each article included a description of the barriers identified, the percentage of participants highlighting the barrier, demographics of the respondents and the characteristics of the included study. Where possible, we estimated the percentages of respondents affected by an obstacle as the difference between 100% and the sum of the percentage with no opinion and those not affected.6 The data extraction sheet was created based on a taxonomy of barriers to implementing clinical practice guidelines.6 The mechanism of action by which improved patient care is attained is believed to proceed through a number of stages.14 Research evidence alters eventual clinical outcome through the intermediate steps of first changing clinician knowledge, then improving attitudes and lastly, changing practitioner behaviour. This taxonomy had been used with success by other investigators. It is reported to stand up well in comparison with alternative taxonomies.7

Both reviewers independently read each report and identified evidence relevant to each of the main outcomes of interest. Barriers were then grouped into themes and the obstacles ordered according to the number of studies in which they were identified. The themes were organised into groups depending on whether they impacted on knowledge, attitude or behaviour.6 The categories drew on an ideal mechanism of a knowledge, attitudes and behaviour framework.14 Before a systematic review can affect patient outcome, it first affects knowledge, then attitudes and finally, behaviour.

Lack of familiarity and awareness, for instance, were listed under the Knowledge section; lack of motivation was listed under the Attitudes section; patient, review and environmental factors were grouped under the Behaviour section. Barriers impeding review uptake through a cognitive component were considered obstacles affecting knowledge. If an affective component was identified then the barrier was listed as impeding attitude. A limitation or restriction on ability was regarded as a barrier-affecting behaviour. Lack of familiarity included impaired ability to correctly answer questions about review content, as well as self-acknowledged lack of familiarity. Lack of awareness was viewed as the inability to adequately acknowledge systematic review existence.

Study characteristics were included in table 1. Methods were outlined in table 2; the results were tabulated in table 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Year published, country | Objective | Design and focus | Participants | Date conducted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilson, et al (2001), UK | To determine attitudes on the importance of effectiveness information | Postal questionnaire Cochrane Library |

338 Medical directors | 1999 |

| Paterson-Brown et al (1995), UK | To establish the availability of meta-analytic overviews and to find out how obstetricians keep up to date | Telephone survey Oxford Database of Perinatal Trials |

98 Obstetricians | 1993 |

| Hanson, et al (2004), Switzerland | To determine current, understanding of study, methodology and critical appraisal | Questionnaire, self-administered Meta-analysis |

532 Surgeons and allied professionals from 78 countries | 2002 |

| Poolman et al (2007), Holland | They examined perceptions and competence in EBM | Postal survey Meta-analysis Systematic reviews Cochrane Library |

366 Orthopaedic surgeons | 2005 |

| Sur et al (2005), USA | Investigated the attitudes of urologists towards EBM | Web-based survey Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) |

714 Urologists | 2005 |

| Dahn et al (2009), USA | To investigate the attitudes of urologists to EBM | Mail survey Meta-analyses CDSRs |

889 Urologists | 2006 |

| McAlister et al (1999b), Canada | To assess the attitudes of general internists to EBM | Postal Survey CDRSs |

294 Physicians | 1997 |

| Wilson et al (2001), UK | To identify current methods of making research evidence accessible | Postal survey Cochrane Library |

1406 General practitioner | 1999 |

| Young and Ward (2001), Australia | Examine views about EBM | Postal Survey and Semi-structured Interviews Cochrane Library |

60 General practitioners (GPs) | 1999 |

| McCaw et al (2007), Ireland | Gain an insight into the use of Internet | Postal survey Cochrane Library |

542 Community pharmacists (178) GPs (364) | 2005 |

| Kerse et al (2001), NZ | Access to Internet and Cochrane Library | Cross-sectional postal and fax survey Cochrane Library |

381 GPs | 1999–2000 |

| McColl et al (1998), UK | To determine the attitude to EBM and perceived usefulness of databases | Postal questionnaire Systematic reviews Meta-analysis Cochrane Library CDSRs DARE |

302 GP principals | 1997 |

| Bennett et al (2003), Australia | To find out about attitudes to EBP and implementation barriers | Postal questionnaire Cochrane Library |

649 Occupational therapists | 2000 |

| Young and Ward (1999), Australia | To determine awareness and use of the Cochrane Library and access to the Internet | Postal questionnaire Cochrane Library |

311 GPs | 1997 |

| Prescott et al (1997), UK | To establish the awareness of research evidence | Self-administered, postal questionnaire survey CDSRs |

800 GPs | 1996 |

| Jordans et al (1998), Australia | To determine the proportion who report using systematic reviews | Cross-sectional telephone survey obstetricians Systematic reviews |

224 Neonatologists | 1995 |

| Ciliska et al (1999), Canada | To gain an understanding of research needs, perceptions of barriers to research utilisation and attitudes towards systematic reviews | Telephone questionnaire survey Systematic reviews |

226 Decision makers in public health Included doctors | NK |

| Olatunbosun et al (1998), Canada | To examine views of EBM | Self-administered, two-page questionnaire Cochrane Library Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database |

190 Physicians in obstetric practice | 1996 |

| Melnyk et al (2004), USA | Describe major barriers and facilitators to EBP | Limited survey CDSRs |

160 Nurses | 2003 |

| Gavgani and Mohan (2008), India | Directed at exploring attitudes towards EBM | Survey method Cochrane Library CDSRs |

98 Physicians | 2008 |

| Wilson et al (2003), UK | To assess the awareness and use of NHSnet | Postal survey questionnaire Cochrane Library |

1364 GPs: 441 Nurses: 325 Practice managers: 556 |

2001 |

| Carey et al (1999), UK | To determine the attitudes of towards the practice of EBM | Postal questionnaire Cochrane Library |

139 Psychiatrists | 1998 |

| Lawrie et al (2000) UK | To examine attitudes to evidence-based psychiatry | Survey, postal CDSRs |

93 Senior psychiatrists | NK |

| Hyde et al (1995), UK | To examine use of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database (CPCD) | Postal survey CPCD Cochrane Library |

274 subscribers to CPCD Included doctors |

1994 |

| Martis et al (2008) Asia | The aim was to assess current knowledge of evidence-based practice | Survey, postal Reproductive Health Library Cochrane Library |

660 Healthcare professionals Included doctors |

2005 |

| Dobbins et al (2007), Canada | The purpose was to identify preferences for the transfer and exchange of research knowledge | Semistructured interviews Systematic reviews |

16 Policy decision makers Included a doctor |

2001 |

| Dobbins et al (2004), Canada | To discover public health decision makers’ preferences for content, format and channels for receiving research knowledge | One-hour focus groups Systematic reviews |

46 Policy makers Included doctors |

2002–2003 |

EBM, Evidence-based medicine; EBP, Evidence-based practice; NK, Not known; DARE, Database of reviews of effects

Table 2.

Methods and quality

| Study | Sample frame | Response rate | Measurement of use of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wilson et al (2001) | Purposive sample of 491 Medical directors Well-described sample |

(69%) 338/491 | Reported use |

| Paterson-Brown et al (1995) | Purposive sample of 98 obstetricians Well-described sample |

(100%) 98/98 | Reported use |

| Hanson et al (2004) | Purposive sample of 1064 surgeons/others Well-described sample |

(50%) 532/1064 | Reported use |

| Poolman et al (2007) | Purposive sample of 611 orthopaedic surgeons Well-described |

(60%) 366/611 | Reported use |

| Sur et al (2006) | Purposive sample of 8100 urologists Well-described sample frame |

(8.8%) 714/8100 | Reported use |

| Dahm et al (2009) | Random sample of 2000 urologists Well-described sample frame |

(45%) 889/2000 | Reported use |

| McAlister et al (1999) | Purposive sample of 294 general Physicians. Well-described sample frame |

(59%) 294/521 | Reported use |

| Wilson et al (2001) | Purposive sample of 3087 individuals Well-described sample frame Primary care |

(45%) 1406/3087 | Reported use |

| Young and Ward (2001) | Sample of 60 general practitioners (GPs) Sampling frame not described |

(100%) 60/60 | Reported use |

| McCaw et al (2007) | Sample of 1081 GPs and 522 pharmacists Well-described sample frame |

(34%) 542/1603 | Reported use |

| Kerse et al (2001) | Random sample of 459 GPs Well-described sample frame |

(83%) 381/459 | Reported use |

| McColl et al (1998) | Random sample of 452 GPs Well-described sample frame |

(63%) 302/452 | Reported use |

| Bennett et al (2003) | Proportional random sample of 1491 occupational therapists Well-described sampling frame |

(44%) 649/1491 | Reported use |

| Young and Ward (1999) | Random sample of 428 GPs Well-described sampling frame |

(73%) 311/428 | Reported use |

| Prescott et al (1997) | Random sample of 800 GPs Well-described sample frame |

(62%) 501/800 | Reported use |

| Jordans et al (1998) | Random sample of 145 Obstetricians and 104 neonatologists Well described sample |

(90%) 224/248 | Reported use |

| Ciliska et al (1999) | 277 who met inclusion criteria of decision makers Well-described sample |

(87%) 242/277 | Reported use |

| Olatunbosun et al (1998) | Random sample of 190 family physicians and obstetricians Well-described sample |

(76%) 148/190 | Reported use |

| Melnyk et al (2004) | ‘Convenient’ sample Well described sample | (100%) 160/1600 | Reported use |

| Gavgani and Mohan (2008) | Random sample Well-described sample |

(65%) 98/150 | Reported use |

| Wilson et al (2003) | All GPs in defined area. Well-described sample |

(44%) 1364/3090 | Reported use |

| Carey and Hall (1999) | All psychiatrists in a defined area Well-defined sample |

(64%) 139/216 | Reported use |

| Lawrie et al (2000) | All in a defined area Well-described sample |

(76%) 93/123 but just 22/123 (17%) contributed to this review | Reported use |

| Hyde et al (1995) | All subscribers to CPCD Well-described sample |

71% 274/387 | Reported use |

| Martis et al (2008) | All in a defined area Well-described sample |

NK | Reported use |

| Dobbins et al (2004) | Purposeful sample Well-described sample |

46/60 (77%) | Reported use |

| Dobbins et al (2007) | Purposeful sample Well-described sample |

16/NK | Reported use |

Table 3.

Barrier descriptive findings

| Barrier category | Barrier descriptive |

|---|---|

| Knowledge barriers | Eleven studies measured lack of awareness as a possible barrier. The percentage of respondents reporting lack of awareness as a barrier was as high as 82% and as low as 1%, with a median of 55%. Eleven surveys measured lack of access as a possible barrier. The percentage of respondents identifying lack of access as a barrier was as high as 95% and as low as 3%, with a median of 55%. Seven surveys measured lack of familiarity as a possible barrier. The percentage of respondents suggesting lack of familiarity as a barrier was as high as 98 and as low as 19%, with a median of 70% |

| Attitudinal barriers | Seven surveys measured lack of perceived usefulness as a possible barrier. The percentage of respondents identifying lack of usefulness as a barrier was as high as 95% and as low as 7%, with a median of 16.5%. Four studies measured lack of motivation as a possible barrier. The percentage of respondents identifying this barrier was as high as 10% and as low as 2% with a median of 3.6% |

| Behaviour barriers | Five studies investigated ten external barriers to review uptake. More than 10% of respondents cited lack of resources, lack of positive policy climate, lack of workshop attendance and lack of training as possible environmental barriers. Fourteen surveys looked at lack of use of systematic reviews. The percentage of respondents reporting lack of use was as high as 99% and as low as 18% with a median of 78% |

In order to assess the quality of the studies, study characteristics were extracted: year of publication, country of origin, main objective of the study, the design of the study and the characteristics of participants. In particular, the sampling strategy of the primary studies, response rate and methodological approach, including data collection strategies, were assessed.

Results

Search yield

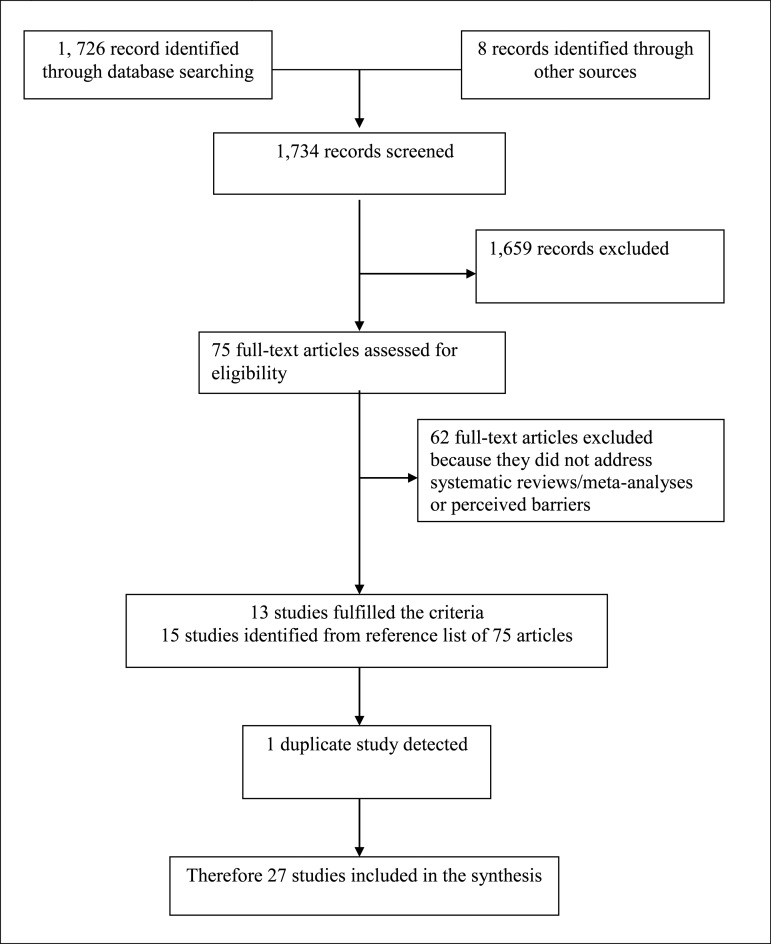

The study selection process is presented in Figure 1. Of 19 databases searched and 3 search engines utilised, there were 1726 specific candidate articles found possibly examining barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews. Some 1651 titles were excluded after examination of the bibliographic citation. After examination of the full text of 75 articles, 13 articles fulfilled the criteria. Fifteen primary studies were detected from the reference lists of these 75 articles. A total of 28 detected reports describing 27 unique studies15–41 met inclusion criteria. Thirteen studies that might possibly be expected to be included but are not, are outlined in box 1 together with the reasons for their exclusion. To be included, studies had to address perceived obstacles to the uptake of evidence specifically from systematic reviews, meta-analyses and the databases that contained them. A search of EMBASE and PubMed from January 2011 to June 2012, failed to detect any relevant, completed or ongoing studies to be added to ‘Studies awaiting classification’ and ‘On-going studies’ tables. The search terms and their combination are outlined in table 4.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow diagram

Box 1. Excluded studies.

Lavis, J. Research, public policymaking and knowledge-translation processes. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2006;26:37–45. Not a survey, focus group or interview, or an intervention.

Glasziou P, Guyatt GH, Dans AL, et al. Applying the results of trials and systematic reviews to individual patients. Evid Based Med 1998;3:165–6. Not a survey, focus group or interview study, or an intervention.

Grimshaw J, Santesso N, Cumston M, et al. Knowledge for knowledge translation: the role of the Cochrane Collaboration. HLWIKA 2006;26:55–62. Not a survey, focus group or interview study, or an intervention.

Lavis J, Davies H, Gruen R, et al. Working within and beyond the Cochrane Collaboration to make systematic reviews more useful to healthcare managers and policy makers. Health Policy 2006;1:21–33. Not a survey, focus group or interview study, or an intervention.

Dobbins M, Ciliska D, Cockerill R, et al. A framework for the dissemination and utilisation of research for healthcare policy and practice. J Know Synth Nurs 2002;18;9:7. Not a survey, focus group or interview study, or an intervention.

Petticrew M, Whitehead M, Macintyre SJ, et al. Evidence for public health policies on inequalities. J Epidemiol Commun Health 2004;58:811–16. Not specifically related to systematic reviews.

Silagy CA, Weller DP, Middleton PF, et al. General practitioners’ use of evidence databases. Med J Aust 1999;170:393.

A comment on previous studies.

Sheldon T. Making evidence synthesis more useful for management and policy making. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):S1–S5.

An essay, not a survey, focus group, or an interview, or an intervention.

Gruen R, Morris P, McDonald E, et al. Making systematic reviews more useful for policy makers. Bull World Health Organ 2005;83. A letter/essay.

Melnyk B, Fineout-Overholt E, Feinstein N, et al. Nurse practitioner educators’ perceived knowledge, beliefs and teaching strategies regarding evidence-based practice: implications for accelerating the integration of evidenec-based practice into graduate programmes. J Prof Nurs 2008;24:7–13. Does not address systematic reviews.

Volmink J, Siegfried N, Robertson K, et al. Research synthesis and dissemination as a bridge to knowledge management: the Cochrane Collororation. Bull Worlds Health Organ 2004;82:778–83. An essay. Not a survey, a focus group, an interview, or an intervention.

Mayer J, Pitman L. The attitudes of Australian GPs to evidence-based medicine: a Focus Group Study. Family Pract 1999;16:627–32. Does not address systematic reviews.

Cranney M, Walley T. Same information, different decisions: the influence of evidence on the management of hypertension in the elderly. Br J Gen Pract 1996;46:661–63. Not specifically about systematic reviews.

Table 4.

Search of PubMed and EMBASE

| PubMed was searched from December 2010 to June 2012 using the advanced search facility | ||

|---|---|---|

| Search | Query | Items found |

| 1 | Systematic review AND barriers AND knowledge uptake | 1 |

| 2 | Meta-analysis AND barriers AND knowledge uptake | 1 |

| 3 | Systematic review AND obstacles AND knowledge uptake | 1 |

| 4 | Meta-analysis AND obstacles AND knowledge uptake | 0 |

| 5 | Systematic review AND barriers AND knowledge utilisation | 3 |

| 6 | Meta-analysis AND barriers and knowledge utilisation | 2 |

| 7 | Systematic review AND obstacles AND knowledge utilisation | 0 |

| 8 | Meta-analysis AND obstacle AND knowledge utilisation | 0 |

| 9 | Overview* OR review* AND impairment* AND knowledge translation | 13 |

| 10 | Systematic review* OR meta-analysis* AND barrier* AND decision-making | 16 |

| 37 citations were returned, none of which met inclusion criteria | ||

| EMBASE was searched from December 2010 to June 2012 using the advanced search facility | ||

| 1 | Systematic review AND barriers AND knowledge uptake | 14 |

| 2 | Meta-analysis AND barriers AND knowledge uptake | 5 |

| 3 | Systematic review AND obstacles AND knowledge uptake | 0 |

| 4 | Meta-analysis AND obstacles AND knowledge uptake | 0 |

| 5 | Systematic review AND barriers AND knowledge utilisation | 14 |

| 6 | Meta-analysis AND barriers and knowledge utilisation | 0 |

| 7 | Systematic review AND obstacles AND knowledge utilisation | 0 |

| 8 | Meta-analysis AND obstacle AND knowledge utilisation | 0 |

| 9 | Overview* OR review* AND impairment* AND knowledge translation | 0 |

| 10 | Systematic review* OR meta-analysis* AND barrier* AND decision-making | 0 |

| 32 citations were returned, 1 full text article retrieved, no report met inclusion criteria | ||

The 27 included studies encompassed two qualitative studies, and 25 surveys asking a total of 57 questions regarding possible barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews, meta-analysis and databases containing them. A survey involved at least one question to a group of decisions makers about barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews. Barriers were grouped into themes: 18 derived from the surveys and additional 10 from the qualitative studies.

The studies were undertaken in the UK (n=9), Canada (n=5), Australia (n=4), the USA (n=3), Ireland (n=1), Holland (n=1), New Zealand (n=1), Switzerland (n=1), India (n=1) and South East Asia: Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines (n=1). One country, Switzerland, surveyed participants from 78 countries. Therefore, included studies reported data from decision makers in 91 countries.

Of 10 218 participants, 64% were physicians (box 2). Two studies24 25 were concerned with the use of systematic review evidence for public health policy and programme management decisions. The remaining studies had a clinical practice focus concerned with investigating attitudes to evidence-based medicine. Seventeen studies (63%) were published after the year 2000.

Box 2. Disciplines participating.

Doctors: 6549

Nurses: 1494

Practice managers: 785

Occupational therapists: 649

Midwives: 202

Pharmacists: 178

General practice staff: 91

Surgical allied professions: 69

Policy makers: 62

Information specialists: 56

Others: 83

Total: 10 218

Study quality

The included studies were limited in terms of the quality and generalisability of their results. While all but one15 had a well-described sampling frame, just 8 of the 27 studies describe selecting a random sample of participants (table 2). Response rates were not mentioned in two16 25 of the 27 studies (table 2). The response rate was variable. The rate varied from 8.8% to 100% and 17 of the 27 studies describe a response rate of at least 60% (table 2). Twenty-six studies reported the number of participants investigated, with the number varying from 16 to 1406.

The number of barriers addressed by each survey varied. Of the 25 surveys, 8 (31%) examined only one type of barrier, and the average number of barriers examined was 1.7. None of the surveys examined six or more barriers and all studies relied on reported use, not actual use, of evidence.

Characteristics of studies

Most studies were surveys (n=25), two were qualitative studies with one included study using mixed methods. Data collection strategies included focus groups (n=1), individual interviews (n=1), together with mail, telephone and web-based questionnaires (n=25).

The characteristics of each study are outlined in table 1. We found that the surveys used a heterogeneous variety of decision-making populations, based on location or specialty. They also investigated a number of resources. The surveys looked at systematic reviews, meta-analyses, the Cochrane Library, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (one of the six high-quality databases maintained by the Library), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, the Reproductive Health Library, also the earlier Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database and the Oxford Database of Perinatal Trials. The surveys displayed a wide range of the percentage of respondents reporting each barrier (table 3).

Identifying barriers

After classifying possible barriers into common themes, it was found that 57 questions about obstacles to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews encompassed 28 barriers. These were grouped according to the knowledge/attitude/behavioural framework.14 Barriers affecting knowledge could include lack of awareness, lack of familiarity and a lack of understanding of meta-analyses. Lack of confidence, decreased motivation, a perceived lack of usefulness of systematic reviews and limited trust in them, were grouped under the Attitudes section. Systematic review attributes, patient issues and environmental factors have the potential to impair usage of systematic reviews. Attributes of systematic reviews such as academic terminology, and environmental factors such as limited resources or a negative organisational climate, were grouped under the Behaviour section.

Knowledge

Eleven studies measured lack of awareness as a possible barrier. Sample size ranged from 248 to 8100 (median, 475) and the response rate ranged from 8.8% to 90% (median, 66%). The percentage of respondents reporting lack of awareness as a barrier was as high as 82% (for DARE17) and as low as 1% (for Cochrane Library18) with a median of 55%. In 9 (82%) of the 11 studies, at least 10% of the respondents cited lack of awareness as a barrier.

Seven surveys measured lack of familiarity as a possible barrier. Sample size ranged from 60 to 8100 (median, 531) and the response rate ranged from 8.8% to 100% (median, 63%). The percentage of respondents suggesting lack of familiarity as a barrier was as high as 98% (DARE17) and as low as 19% (systematic reviews17) with a median of 70%. In seven (100%) of the seven surveys, at least 10% of the respondents cited lack of familiarity as a barrier.

Attitude

Four studies measured lack of motivation as a possible barrier. Sample size ranged from 98 to 8100 (median, 1305). The percentage of respondents identifying this barrier was as high as 10% (Oxford Database of Perinatal Trials21) and as low as 2% (meta-analysis22) with a median of 3.6%. In none of the surveys did more than 10% of respondents report lack of motivation as a barrier.

Seven surveys measured lack of perceived usefulness as a possible barrier. Sample size ranged from 60 to 491 (median, 350) and the response rate ranged from 63% to 100% (median, 87%). The percentage of respondents identifying lack of usefulness as a barrier was as high as 95% (systematic reviews17) and as low as 7% (Cochrane Library18) with a median of 16.5%. In six of the seven surveys, at least 10% of the respondents cited lack of usefulness as an issue.

Behaviour

Eleven surveys measured lack of access as a possible barrier. Sample size ranged from 60 to 3087 (median, 440) and the response rate ranged from 44% to 100% (median, 71%). The percentage of respondents identifying lack of access as a barrier was as high as 95% (lack of easy access to Cochrane Library19) and as low as 3% (lack of access to Cochrane Library20), with a median of 55%. In 10 (91%) of the 11 surveys, at least 10% of the respondents cited lack of access as a barrier.

Five studies investigated 10 external barriers to overview uptake. The external barriers investigated were environment-related in five studies and also systematic review-related in one study, with no patient-related barriers cited. More than 10% of respondents cited lack of resources and lack of positive policy climate,23 lack of workshop attendance,16 and lack of training in Cochrane Library use18 20 as possible environmental barriers. Lack of time was not cited by more than 10% of participants.18 More than 10% of respondents cited the limited range of topics covered by the Cochrane Library18 as a possible barrier.

Fourteen surveys looked at lack of use of systematic reviews. Sample size ranged from 150 to 8100 (median, 490) and the response rate ranged from 8.8% to 100% (median, 63%). The percentage of respondents reporting lack of use was as high as 99% (DARE17) and as low as 18% (Cochrane Library16) with a median of 78%. In 14 (100%) of the 14 surveys, at least 10% of the respondents did not use systematic reviews or the databases containing them.

Qualitative studies

Two qualitative studies24 25 cited six important barriers to evidence uptake from systematic reviews. The two studies emphasised lack of accessibility. They also cited a lack of training in the purpose and methodology of systematic reviews as a barrier to uptake. Content issues such as lack of relevance, lack of implications for practice and limited implementation strategies were also cited. A deficient understanding of the information needs of the target audience of systematic reviews was also raised as a major barrier.

One study had a qualitative element exploring the perceived weaknesses of the Cochrane Library.18 Participants suggested as barriers the limited range of topics covered, poor access, the narrow focus on randomised controlled trials and meta-analysis, difficulty of use, lack of regular update, poor promotion and the time required to use and search the database. Number of barriers investigated by each study is tabulated in table 5.

Table 5.

Number of barriers investigated by each study to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews, meta-analyses and the databases containing them

| Surveys | Number of barriers addressed by each study |

|---|---|

| Wilson et al (2001) | 4: Lack of access, awareness, use and training |

| Paterson-Brown et al (1995) | 2: Lack of access and awareness |

| Hanson et al (2004) | 2: Lack of trust and training |

| Poolman et al (2007) | 2: Lack of understanding, use |

| Sur et al (2006) | 3: Lack of awareness, use and understanding |

| Dahm et al (2009) | 3: Lack of awareness, use and understanding, |

| McAlister et al (1999) | 1: Lack of use |

| Wilson et al (2001) | 1: Lack of access |

| Ward andYoung (2001) | 3: Lack of access, understanding and usefulness |

| McCaw et al (2007) | 1: Lack of use |

| Kerse et al (2001) | 3: Lack of access, awareness and use |

| McColl et al (1998) | 3: Lack of awareness, access and understanding |

| Bennett et al (2001) | 1: Lack of confidence |

| Young and Ward (1999) | 3: Lack of awareness, access and use |

| Paterson-Brown (1993) | 3: Lack of awareness, availability and need |

| Prescott et al (1999) | 2. Lack of use and awareness |

| Jordan et al (1999) | 3: Lack of use, awareness and access |

| Ciliska et al (1999) | 4: Lack of awareness, use, policy climate and resources |

| Olatunbosun et al (1998) | 1: Lack of access |

| Melnyk et al (2004) | 1: Lack of use |

| Gavgani et al (2008) | 2: Lack of use and usefulness |

| Wilson et al (2003) | 4: Lack of access, awareness, use and training |

| Carey and Hall, (1999) | 1: Access |

| Lawrie et al (2000) | 1: Ability to search |

| Hyde et al (1995) | 1: Ability to search |

| Martis et al (2008) | 5: Lack of access, awareness, use, usefulness and training |

| Qualitative studies | |

| Dobbins et al (2004) | 2: Lack of access and training |

| Dobbins et al (2007) | 4: Lack of relevance, implications, implementation strategies and understanding of the information needs of the target audience |

| Wilson et al (2001) | 7. Limited range, access, focus, use, up-datedness, promotion and time |

Discussion

While access is improving, the Cochrane Library is still not free in all countries and lack of access is still seen as a significant barrier. Access, of course, impacts on awareness and familiarity. While the Cochrane Library has achieved widespread awareness, in the majority of the studies, more than 10% of participants still cited lack of awareness of systematic reviews or the databases that contain them, as a barrier.

Casual awareness does not guarantee familiarity with systematic reviews. Lack of familiarity was more common than lack of awareness.17 Furthermore, at least 10% of the respondents cited the lack of usefulness of systematic reviews as a significant obstacle.

A negative attitude and a lack of knowledge may inhibit the uptake of systematic reviews. However, factors related to the review itself, the patient or wider environmental barriers may also impair uptake. Limited relevance and a paucity of implications for pratice were seen as barriers together with the limited range of topics covered.18 More than 10% of respondents cited lack of a receptive policy climate23 and lack of training in database searching20 as possible environmental barriers.

The everyday usage of systematic reviews should improve attitudes to this form of evidence. However, there is considerable evidence that this is not happening.17 Surprisingly, lack of time and motivation did not emerge as major barriers to systematic reviews uptake.

Limitations

The extensive and systematic literature search is one of the strengths of this systematic review. Explicit inclusion criteria and a transparent approach to collecting data were also utilised. Each included study was assessed by at least two of the authors. The limitations of our systematic review largely reflect the shortcomings of the reports reviewed.

All the 27 included studies, except for the two qualitative studies, were surveys using closed-ended questions. This meant that the obstacles addressed were dependent very much on investigator preference. A fear of being outside a consensus for instance, was not specifically investigated as a barrier. Use of a different taxonomy may have altered our findings. But the taxonomy selected and utilised here compares well to other taxonomies.42

Because much of the research in the knowledge translation field is poorly indexed in electronic databases and spread over many disciplines, relevant studies may have been overlooked, though searching the reference lists of related studies yielded additional reports.

Another potential defect is the use of participant self-ratings. The individual studies depended on the decision maker's perceptions and views. Actual clinical practice was not assessed. Whether an obstacle is real or perceived may affect the strategy required to address the identified barrier.

Some of the included studies were limited with respect to sampling and generalisability. Some surveys were small and used non-random samples confined to specific groups. This limits the extent to which the findings can be generalised. A well-described sampling frame and a good response rate improve our confidence in a study's results. A low response rate in some of the surveys increases the potential for selection bias. The external validity of the studies can be questioned as a poor response rate increases the impact of non-responder bias in the survey results.28 However, by including a wide range of decision makers in our systematic review, this increases our appreciation of how differences in healthcare systems can impact on review uptake.

Implications

This analysis offers a list of reasons for understanding why decision makers may be disinclined to use systematic reviews. A number of barriers already cited by Cabana and colleagues6 to guideline adherence were identified, though in our study, time constraints, limited motivation and patient-related factors were not highlighted. The results of this review have a number of implications for systematic review uptake in particular and evidence uptake in general.

Despite the high regard in which systematic reviews and the Cochrane Library are held, there are a variety of barriers to systematic review uptake. These include lack of access, lack of awareness, lack of familiarity, lack of perceived usefulness, limited actual use in practice and finally, a number of external barriers to do with systematic review content, presentation and wider organisational factors.

Few studies, however, consider the full variety of barriers that must be overcome to achieve enhanced uptake. The average number of barriers examined was 1.7. By not investigating a full variety of barriers, strategies to improve use are less likely to address all the important factors inhibiting systematic review uptake and, as a result, are less likely to be successful.6 Interventions designed to change practice should be based on an accurate assessment of the factors that support targeted health outcomes.43 The accuracy of this assessment is directly related to the future impact of the intervention.44 If we accept this finding, then it is vital to identify the factors that influence the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews in order to help develop targeted interventions to enhance information uptake from this important resource.9 Future research needs to address a fuller range of impediments to evidence uptake, with practical difficulties encountered in using systematic reviews observed and documented by researchers through ‘user testing’ of this source of evidence by participants.45

Access to the Cochrane Library is critical in order to advance evidence-based healthcare. Connectivity seems to have increased 20 but access and use of databases needs to be improved. Even different professionals working in the same clinical setting can have different levels of access to the same database, an issue deserving of further investigation.20 If most of those who have access to the database then go on to actually use the Cochrane Library then access may be an important issue to be investigated further. Strategies to assist those least likely to use Cochrane databases may help the move towards evidence-based practice.27

Conclusion

Much work has been done on the barriers to the uptake of evidence from clinical practice guidelines.6 The barriers that Cabana and colleagues commonly identified to guideline adherence were lack of awareness and familiarity, lack of belief in a good outcome after adopting the guideline, and the inertia of previous practice including lack of motivation.

Lack of motivation to use systematic reviews did not emerge as a major obstacle to systematic review uptake in our study. However, in common with research on the uptake of evidence in general, lack of access and limited awareness continue to be significant perceived barriers to systematic review uptake. Importantly, lack of practical use of systematic reviews continues to present a major challenge to evidence uptake. To become familiar with an innovation, it must be used. For systematic reviews, this is not happening often enough.

Strategies to improve uptake of reviews should emphasise the usefulness of reviews for research and clinical practice. They should also provide a practical opportunity to use and become familiar with systematic reviews and the databases containing them, preferably in an organisational climate that values research.

To our knowledge, this study represents the first systematic review, of a diverse group of decision makers, of barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews, meta-analyses and their related databases. The results presented here have immediate and practical relevance for clinicians and organisations that are trying to improve access to the best available evidence and enhance its use in routine practice. These findings provide a sound basis on which to plan future interventions to enhance the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses among physicians and other decision makers, leading to improved care for the individual patient.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Substantial contributions have been made to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation by all authors. Substantial contributions have been made to draft the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content by all authors and all have given approval for it to be published.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed by e-mailing john.wallace@wadh.oxon.org

References

- 1.Innvaer S, Vist G, Trommald M, et al. Health policy-makers’ perceptions of their use of evidence: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy 2002;7:239–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham I. Knowledge to action: what it is and what it isn't. In: Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham I, eds. Knowledge translation in health care. UK: Wiley-Blackwell, BMJ Books, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sackett D, Rosenberg WC, Muir Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ 1996;312:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tetzlaff J, Tricco A, Moher D. Knowledge synthesis. In: Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham I. D, eds. Knowledge translation in health care. UK: Wiley-Blackwell, BMJ Books, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennet NL, Casebeer LL, Zheng S, et al. Information seeking behaviours and reflective practice. J Contin Educ Prof 2006;26:120–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabana M, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282:1458–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gravel K, Legare F, Graham I. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health care professionals. Implement Sci 2006;1:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavis J, Davies H, Oxman A, et al. Toward systematic reviews that inform health care management. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:35–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochrane LJ, Olson CA, Murray S, et al. Gaps between knowing and doing: understanding and assessing the barriers to optimal health care. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2007;27:94–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavis JN. How can we support the use of systematic reviews in policy making? PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000141 doi:10.137/journal.pmed.1000141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthy L, Shepperd S, Clarke M, et al. Interventions to improve the use of systematic reviews for clinical and commissioning decision-making. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; CD009401, doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobbins M, Cockerill R, Barnsley J, et al. Factors of the innovation, organisation, environment, and individual that predict the influence five systematic reviews had on public health decisions. Int J Technol Assessm Health Care 2001;17:467–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang T, Secic M. How to report statistics in medicine. Philadelphia: ACP, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woolf SH. Practice guidelines: a new reality in medicine, III: impact on patient care. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:2646–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young J, Ward J. Evidence-based medicine in general practice: beliefs and barriers among Australian GPs. J Evaluat Clin Pract 2001;7:201–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martis R, Ho J, Crowther C. Survey of knowledge and perception on the access to evidence-based practice and clinical practice change among maternal and infant health practitioners in South East Asia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2008;8:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McColl A, Smith H, White P, et al. General practitioner's perceptions of the route to evidence based medicine: a questionnaire survey. BMJ 1998;316:361–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson P, Watt I, Hardman P. Survey of medical directors’ views and use of the Cochrane Library. Br J Clin Governance 2001;6:34–9 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson P, Droogan J, Glanville J, et al. Access to the evidence base from general practice: a survey of general practice staff in Northern and Yorkshire region. Qual Health Care 2001;10:83–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson P, Glanville J, Watt I. Access to the online evidence base in general practice: a survey of the Northern and Yorkshire region. Health Inform Libr J 2003;20:172–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paterson-Brown S, Fisk N, Wyatt J. Uptake of meta-analytical overviews of effective care in English obstetric units. J Obstr Gynaecol 1995;102:297–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sur R, Scales C, Jr, Preminger G, et al. Evidence-based medicine: a survey of American urological association members. J Urol 2006;176:1127–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciliska D, Hayward S, Dobbins M, et al. Transferring public-health nursing research to health-system planning: assessing the relevance and accessibility of systematic reviews. Can J Nurs Res 1999;31:23–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobbins M, DeCorby K, Twiddy T. A knowledge transfer strategy for public health decision makers. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2004;1:120–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobbins M, Jack S, Thomas H, et al. Public health decision-makers’ informational needs and preferences for receiving information. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2007;4:156–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett S, Tooth L, McKenna K, et al. Perceptions of evidence-based practice: a survey of Australian occupational therapists. Aust Occup Ther J 2003;50:13–22 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerse N, Arroll B, Lloyd T, et al. Evidence databases, the internet, and general practitioners: the New Zealand story. N Z Med J 2001;114:89–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dahm P, Poolman R, Bhandari M, et al. 2009. Perceptions and competence in evidence-based medicine: a survey of the American Urological Association Membership. J Urol 2009;18:767–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young J, Ward J. General practitioner's use of evidence databases. MJA 1999;170:56–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melnyk B, Fineout-Overholt E, Feinstein N, et al. Nurses’ perceived knowledge, beliefs skills and needs regarding evidence-based practice: implications for accelerating the paradigm shift. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2004;1:185–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prescott K, Lloyd M, Doughlas H-R, et al. Promoting clinically effective practice: general practitioners’ awareness of sources of research evidence. Family Pract 1997;14:320–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordans C, Hawe P, Irwig L, et al. Use of systematic reviews of randomized trials by Australian neonatologists and obstetricians. MJA 1998;168:267–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olatunbosun O, Edouard L, Pierson RA. Physician's attitudes toward evidence-based obstetric practice: a questionnaire survey. BMJ 1998;316:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gavgani V, Mohan V. Physicians’ attitude towards evidence-based medical practice and health science library services. LIBRES Libr Inform Sci Res Electr J 2008;18 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanson B, Bhandari M, Audige L, et al. The need for education in evidence-based orthopaedics. Acta Orthop Scand 2004;75:328–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poolman R, Sierevelt I, Farrokhyar F, et al. Perceptions and competence in evidence-based medicine: are surgeons getting better? J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:206–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAlister FA, Graham I, Karr G, et al. Evidence-based medicine and the practicing clinician. J Gen Intern Med 1999;14:236–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCaw B, McGlade K, McElnay J. The impact of the internet on the practice of general practitioners and community pharmacists in Northern Ireland. Inform Primary Care 2007;15:231–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carey S, Hall D. Psychiatrists’ views of evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Bull 1999;23:159–61 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawrie SM, Scott AIF, Sharpe MC. Evidence-based psychiatry—do psychiatrists want it and can they do it? Health Bull 2000;58:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hyde C. Who uses the Cochrane pregnancy and childbirth database? BMJ 1995;29:310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Espeland A, Baerheim A. Factors affecting general practitioners’ decisions about plain radiography for back pain: implications for classification of guideline barriers—a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2003;3:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grol R, Grimshaw J. Evidence-based implementation of evidence-based medicine. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 1999;25:503–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bloom BS. Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005;21:380–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenbaum S, Glenton C, Cracknell J. User experiences of evidence-based online resources for health professionals: user testing of the Cochrane Library. BMC Med Infrom Decis Making 2008;8:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.