Abstract

Objective

To examine the effects of stamped reply envelope and the timing of newsletter distribution.

Design

A randomised controlled trial in a prospective cohort study with a 2×2 factorial design of two interventions.

Setting

The Japan Nurses’ Health Study (JNHS), a prospective cohort study for women's health.

Participants

The present study included 6938 women who were part of the first-year entry cohort for the fifth wave of the biannual follow-up survey of the JNHS.

Intervention

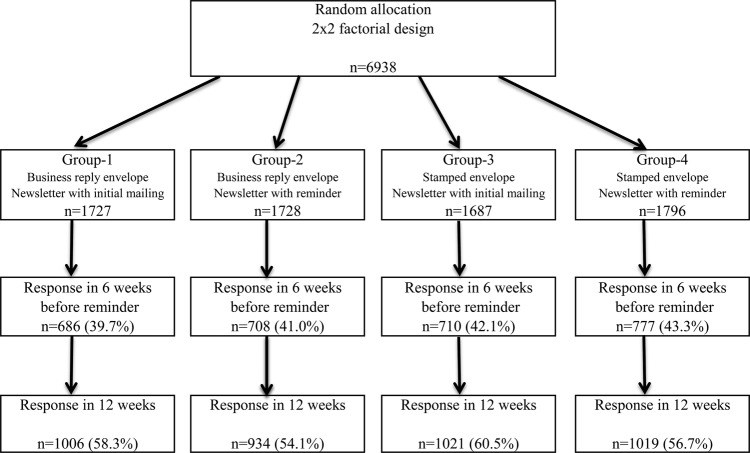

The participants were randomly allocated into four groups; Group-1 (business-reply, newsletter with initial mailing), Group-2 (business-reply, newsletter with reminder), Group-3 (stamped envelopes, newsletter with initial mailing) and Group-4 (stamped envelopes, newsletter with reminder). The thank-you and reminder letters were mailed out at the end of the sixth week. This study was censored at the end of 12 weeks.

Main outcome measures

Main outcome measures were cumulative response at the end of 6 and 12 weeks after mailing out the questionnaire.

Results

The cumulative response at 12 weeks were 58.3% for Group-1, 54.1% for Group-2, 60.5% for Group-3 and 56.7% for Group-4 (p=0.001). The odds of the response was higher for stamped envelopes than for business-reply envelopes (OR (95% CI)=1.10(1.00 to 1.21)). The odds was higher for newsletter delivery with initial mailing than for with reminder (1.18(1.07 to 1.29)). The response in first 6 weeks for stamped envelope was significantly higher than for business-reply envelope (p=0.047). Although the response in 6 weeks for women received the newsletter with initial mailing was lower than for women who did not, the proportions did not differ significantly (p=0.291).

Conclusions

The style of return envelope affected response rates of mail survey. The results of this study suggest that practices of provision of the additional information, should be handled individually in advance, as a separate event from sending follow-up questionnaire or reminder letters.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS, HEALTH ECONOMICS, SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT

Article summary.

Article focus

In the present study, drawing on data from the fifth wave of the Japan Nurses’ Health Study (JNHS), we examined whether and how stamped reply envelopes compared to business reply envelopes and the timing of newsletter delivery affected the odds of a response.

Key messages

This study randomly allocated subjects to four different survey methods within the established study population with a 2×2 factorial design, by utilising the JNHS, the first nationwide women cohort sturdy in Japan.

Enclosing stamped return envelopes was effective to increase the response rates.

The results of this study suggested that practices such as provision of additional information should be handled individually in advance, as separate events, for maintaining the cohort.

Strength and Limitation

The cohort of the JNHS follow-up survey consists of female healthcare professionals with a nursing license who agreed to participate in the survey by signing an informed consent form. It may be problematic to apply the results of the present analysis to a broader population.

A major advantage of the present analysis is that the JNHS is a nationwide occupational cohort study in Japan, and drawing on data from the cohort study, we could randomly allocate items of research interest, that is, type of return envelopes and timing of newsletter delivery, within the survey population.

Introduction

The Japan Nurses’ Health Study (JNHS) is a nationwide prospective occupational cohort study to explore women's health in Japan.1 The JNHS was designed as a prospective study, which consists of a cross-sectional baseline survey that includes a 6-year entry period from 2001 to 2007, and a 10-year follow-up study, from 2001 to 2017.1 For a prospective cohort study, maintaining the cohort, that is, maintaining high follow-up response rates is a major issue. A cohort study is used to estimate risks, rates or occurrence times of events, and thus requires that the whole cohort remain under observation for the entire follow-up period.2 Loss of subjects during the study period lowers the validity of the study, because it makes estimation more difficult due to unknown outcomes of lost subjects. Prospective cohort studies that take many years are likely to experience difficulties with locating people over the study period.2 Follow-up studies that maintain less than about 60% of subjects are considered insufficient to provide confident estimates.2

In an effort to achieve high response rates, offering incentives to respondents has become prevalent. A systematic review of 292 surveys showed that monetary and non-monetary incentives improved the odds of returning the questionnaire.3 Also, prior studies reported that the odds of receiving responses were increased when postoffice stamped reply envelopes were used compared with enclosing prepaid business-reply envelopes,3 although the results were mixed.4 Furthermore, sending advance letters have been shown to increase response rates, as well as providing follow-up contacts such reminder letters, telephone contacts and providing non-respondents with a second copy of the questionnaire.3 5–7 In addition, a study has reported that sending a cover letter that asks recipients to decline participation within 7 days if they do not want to participate raises response rates.8 Yet, using information leaflets upon recruitment did not affect the number of participants in the survey.9

As far as the JNHS is concerned, follow-up questionnaires are mailed to the cohort along with a newsletter. The newsletters are designed to update participants on new information about women's health and the progress of the JNHS. Women who do not respond to the first mailed questionnaire receive a second mailing within 6 months. Subsequently, women who still do not respond receive a third and fourth questionnaire. If the JNHS coordination centre cannot contact participants by mail, the JNHS Follow-up Committee confirms if the subject has moved, and a questionnaire is sent to the new address, which is obtained from the resident registry of the corresponding local district.

In the present study, drawing on data from the fifth wave of the JNHS, we examined whether and how stamped reply envelopes compared with business-reply envelopes and the timing of newsletter delivery affected the odds of a response. In Japan, studies that receive public funds are not allowed to offer incentives or stamped reply envelopes to survey participants as participants may not respond, and such a practice is regarded as a waste of research expenses for a study supported by the national government. However, for the JNHS it is expected that the use of stamped envelopes and delivery of a newsletter will have favourable effects on response rates. It is hoped that because the present study population draws from a homogeneous cohort consisting of healthcare professionals, information regarding women's health in general and results of previous JNHS surveys would encourage participant involvement in the study.

Methods

Objectives

The primary objective of the study was to examine whether stamped reply envelopes and enclosed newsletter improve response rates of mail survey by a 2×2 factorial randomised controlled trial in the JNHS cohort. The secondary objective was to explore the demographic and lifestyle factors that affect response rate of mail survey in a women cohort.

Participants

The JNHS consists of a cross-sectional baseline survey that includes a 6-year entry period, from 2001 to 2007 and a 10-year follow-up study, from 2001 to 2017. The study population was designed for female registered nurse, licenced practical nurses, public health nurses and/or midwives, who were at least 30 years of age and resident in Japan. Although the participants were licenced to practice nursing, they did not necessarily function as nurses. The baseline survey includes 49 927 responses from participants in Japan. Among them, 14 932 women signed an informed consent form and participated in the follow-up survey. Institutional review boards of Gunma University and the National Institute of Public Health reviewed and approved the JNHS study protocol. The study design of the JNHS has been presented elsewhere.1The present study included 6938 women who were in the first-year entry cohort for the fifth-wave follow-up survey of the JNHS.

Intervention

To estimate the effect of types of return envelope and timing of newsletters, women were randomly allocated into the four groups with a 2×2 factorial design. For Group-1 and Group-2, business-reply return envelopes for postpayment by the recipient were enclosed, and for Group-3 and Group-4, stamped return envelopes were provided. In terms of timing of newsletter delivery, for Group-1 and Group-3, the newsletter was enclosed when the questionnaires were mailed out and for Group-2 and Group-4, the newsletters were sent with the reminder letters. The questionnaires were mailed to participants on 22 December 2009, and a thank-you and reminder letter was mailed out to all respondents (regardless of whether they had already returned their self-administered questionnaires to the data centre) at the end of the sixth week (2 February 2010). The present study was censored at 16 May 2010 (12 weeks or 84 days). Sample size was determined by the size of the available cohort. With an expected number of 3469 (ie, 6938/2) per group, and a reference response rate of 60%, for 80% power and 5% significance, the detectable difference in response rate was ±3.3%.

When the participants registered at baseline survey, the sequential unique seven-digit ID numbers were assigned randomly by the JNHS data centre. According to the ID numbers, participants were allocated to the four groups. The allocated group number for each participant was the remainder when the ID number was divided by four.

Measurements

Primary outcome measure was cumulative response proportion at 12 weeks after mailing out the questionnaire. Secondary outcome measure was cumulative response at the end of 6 weeks after initial mailing, just before delivering the reminder letters.

The participants were simultaneously randomised to two interventions; type of return envelope (business reply vs stamped return envelopes) and timing of newsletter delivery (newsletter with initial mailing vs newsletter with reminder). Besides these two variables, following demographic and lifestyle variables were used to explore the factors affecting response rates: age at the survey, type of nursing licence (registered nurse, licenced nurse, midwives and public health nurse), region of residence (Hokkaiko, Tohoku, Kanto, Hokuriku_Koshin, Tokai, Kinki, Cyugoku, Shikoku, Kyusyu and Okinawa) and type of residence area (urban (Tokyo metropolitan area and other 19 large cities designated by government ordinance) and not-urban area), work status (not-working and working), smoking status (smoking and not-smoking), alcohol drinking (<3 days a week and ≥3 days a week), pregnancy (pregnant and not-pregnant) and menopausal status (postmenopausal and others). All the data were obtained from the available latest wave of survey. These variables included factors previously studied10–12 and reproductive health-related issues in women.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of participants were compared between groups using analysis of variance and χ2 test to check the relevance of randomisation process. Before examining main effect of two interventions, type of return envelope (business reply vs stamped) and timing of newsletter provision (with initial mailing vs with reminder) on cumulative response proportion at 6 and 12 weeks after initial mailing, the interaction of these two interventions was tested by logistic regression model. The main effects of the interventions were tested by χ2 test. In order to examine the factors affecting the responses in 12 weeks after initial mailing, logistic regression models were used to estimate unadjusted and age-adjusted ORs and their 95% CIs. For all statistical analysis, SAS V.9.1 (SAS Institute, North Carolina, USA) was used and p<0.05 was set as statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Of the 6938 women of the first-year entry JNHS cohort, 1727, 1728, 1687 and 1796 women were randomised into Group-1, Group-2, Group-3 and Group-4, respectively (figure 1). With the questionnaire, 3455 received business-reply return envelopes and 3483 women were provided with stamped envelopes. A total of 3414 women received the newsletter with initial mailing and 3524 women received the newsletter with thank-you and reminder mailing. The four groups did not differ significantly in demographic and lifestyle characteristics (table 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of cumulative response proportion by the allocation group.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

| Group-1 | Group-2 | Group-3 | Group-4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing of newsletter delivery | Business reply with initial mailing | Business reply with reminder | Stamped with initial mailing | Stamped with reminder |

| n=1727 | n=1728 | n=1687 | n=1796 | |

| Age at survey (years) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 49.7±7.5 | 49.7±7.5 | 50.0±7.6 | 50.2±7.7 |

| Nursing licence | ||||

| Registered nurse | 1412 (81.8%) | 1446 (83.7%) | 1390 (82.4%) | 1487 (82.8%) |

| Licenced nurse | 118 (6.8%) | 111 (6.4%) | 114 (6.8%) | 127 (7.1%) |

| Midwives | 162 (9.4%) | 136 (7.9%) | 152 (9.0%) | 151 (8.4%) |

| Public health nurse | 25 (1.4%) | 27 (1.6%) | 17 (1.0%) | 22 (1.2%) |

| Unknown | 10 (0.6%) | 8 (0.5%) | 14 (0.8%) | 9 (0.5%) |

| Work | ||||

| Working | 1599 (92.6%) | 1600 (92.6%) | 1565 (92.8%) | 1644 (91.5%) |

| Not working | 108 (6.3%) | 110 (6.4%) | 102 (6.0%) | 131 (7.3%) |

| Unknown | 20 (1.2%) | 18 (1.0%) | 20 (1.2%) | 21 (1.2%) |

| Region of residence | ||||

| Hokkaido | 22 (1.3%) | 31 (1.8%) | 28 (1.7%) | 28 (1.6%) |

| Tohoku | 192 (11.1%) | 188 (10.9%) | 183 (10.8%) | 207 (11.5%) |

| Kanto | 284 (16.4%) | 272 (15.7%) | 260 (15.4%) | 264 (14.7%) |

| Hokuriku_Koshin | 267 (15.5%) | 243 (14.1%) | 260 (15.4%) | 255 (14.2%) |

| Tokai | 139 (8.0%) | 165 (9.5%) | 143 (8.5%) | 163 (9.1%) |

| Kinki | 269 (15.6%) | 245 (14.2%) | 272 (16.1%) | 248 (13.8%) |

| Cyugoku | 140 (8.1%) | 157 (9.1%) | 142 (8.4%) | 161 (9.0%) |

| Shikoku | 136 (7.9%) | 125 (7.2%) | 132 (7.8%) | 154 (8.6%) |

| Kyusyu | 250 (14.5%) | 280 (16.2%) | 240 (14.2%) | 285 (15.9%) |

| Okinawa | 28 (1.6%) | 22 (1.3%) | 27 (1.6%) | 31 (1.7%) |

| Type of residence area* | ||||

| Urban | 308 (17.8%) | 321 (18.6%) | 323 (19.1%) | 342 (19.0%) |

| Non-urban | 1419 (82.2%) | 1407 (81.4%) | 1364 (80.9%) | 1454 (81.0%) |

| Smoking† | ||||

| Smoker | 187 (10.8%) | 184 (10.6%) | 194 (11.5%) | 195 (10.9%) |

| Non-smoker | 1537 (89.0%) | 1541 (89.2%) | 1485 (88.0%) | 1597 (88.9%) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.2%) | 3 (0.2%) | 8 (0.5%) | 4 (0.2%) |

| Drinking† | ||||

| <3 days a week | 1286 (74.5%) | 1275 (73.8%) | 1261 (74.7%) | 1359 (75.7%) |

| ≥ 3 days a week | 402 (23.3%) | 402 (23.3%) | 387 (22.9%) | 398 (22.2%) |

| Unknown | 39 (2.3%) | 51 (3.0%) | 39 (2.3%) | 39 (2.2%) |

| Pregnancy† | ||||

| Pregnant | 13 (0.8%) | 15 (0.9%) | 21 (1.2%) | 21 (1.2%) |

| Not pregnant | 1702 (98.6%) | 1709 (98.9%) | 1651 (97.9%) | 1763 (98.2%) |

| Unknown | 12 (0.7%) | 4 (0.2%) | 15 (0.9%) | 12 (0.7%) |

| Menopause† | ||||

| Postmenopausal | 603 (34.9%) | 617 (35.7%) | 625 (37.0%) | 690 (38.4%) |

| Premenopausal | 1103 (63.9%) | 1099 (63.6%) | 1046 (62.0%) | 1079 (60.1%) |

| Unknown | 21 (1.2%) | 12 (0.7%) | 16 (0.9%) | 27 (1.5%) |

| Participation in previous survey | ||||

| Wave II | 1506 (87.2%) | 1509 (87.3%) | 1490 (88.3%) | 1592 (88.6%) |

| Wave III | 1425 (82.5%) | 1429 (82.7%) | 1378 (81.7%) | 1485 (82.7%) |

| Wave IV | 1357 (78.6%) | 1366 (79.1%) | 1364 (80.9%) | 1431 (79.7%) |

*Urban areas are Tokyo metropolitan area and other 19 large cities designated by government ordinance.

†Data in latest available survey.

Cumulative response proportion by group

The cumulative response proportions at 12 weeks were 58.3% for women in Group-1, 54.1% for Group-2, 60.5% for Group-3 and 56.7% for Group-4 (figure 1), and these proportions significantly differed among the groups (χ2 = 15.5; df=3; p=0.001). There was not statistically significant interaction effect of two interventions, type of enclosed return envelope and timing of newsletter delivery, on the proportions (p=0.881). The response for women who received stamped reply envelopes (Group-3 and Group-4) was 58.6%, and it was significantly higher compared with the proportion of 56.2% for those who received business-reply envelopes (Group-1 and Group-2) (χ2 = 4.15; d.f.=1; p=0.042). With respect to the effect of newsletter, the cumulative response proportion at 12 week when the newsletter was delivered at initial mailing was significantly higher than the response when the newsletter was delivered with thank-you and reminder letters (χ2 = 11.1; d.f.=1; p<0.001); 59.4% for Group-1 and Group-3 and 55.4% for Group-2 and Group-4.

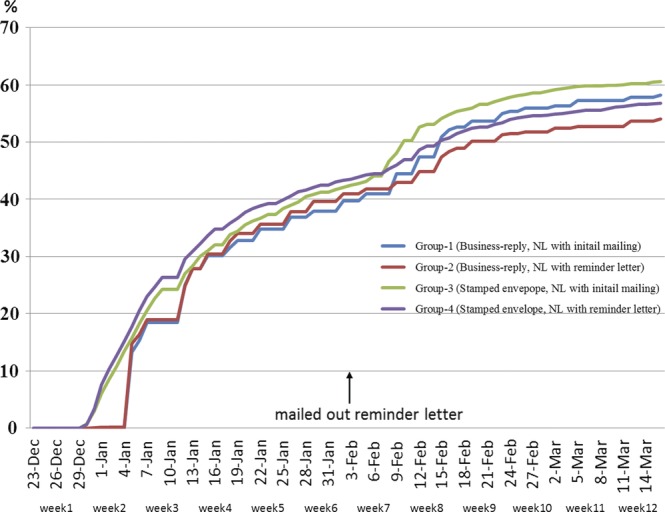

We compared the cumulative proportions at 6 weeks to confirm the main effects of interventions without the effect of reminder mailing (figure 2). The proportion at 6 weeks for business-reply envelopes (Groups-1 and 2) was 40.3% and the proportion for stamped reply envelopes (Group-3 and Group-4) was 42.7%, and those proportions differed significantly (χ2 = 3.93; d.f.=1; p=0.047). The proportion for women received the newsletter with initial mailing (Group-1 and Group-3) was 40.9% and the proportion for women who did not receive it with initial mailing (Group-2 and Group-4) was 42.1%, and these proportions did not differ significantly (χ2 = 1.11; d.f.=1; p=0.291).

Figure 2.

Cumulative response by a randomly allocated group.

Factors affecting response

The ORs and 95% CIs for cumulative responses at 12 weeks are shown in table 1. With respect to two interventions, unadjusted ORs showed statistically significant effects. The stamped envelopes raised the response by 10% relative to provision of business-reply envelopes (OR (95% CI)=1.10 (1.00 to 1.21)), and the newsletter delivery with initial mailing raised the response by 18% relative to the delivery with reminder letters (1.18 (1.07 to 1.29)). However, when adjusted by age at the survey, the effect of stamped return envelopes became non-significant (table 2).

Table 2.

OR for cumulative response of questionnaires in 12 weeks

| Unadjusted |

Age-adjusted |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Interventions | ||||

| Type of return envelope | ||||

| Business-reply return envelope | Referent | Referent | ||

| Stamped return envelope | 1.10 | (1.00 to 1.21) | 1.09 | (0.995 to 1.20) |

| Timing of newsletter delivery | ||||

| With reminder mailing | Referent | Referent | ||

| With initial mailing | 1.18 | (1.07 to 1.29) | 1.18 | (1.07 to 1.30) |

| Demographic and lifestyle factors | ||||

| Age at survey (for 1 year increase) | 1.02 | (1.01 to 1.03) | ||

| Nursing licence | ||||

| Registered nurse | Referent | Referent | ||

| Licenced nurse | 0.879 | (0.728 to 1.06) | 0.780 | (0.643 to 0.946) |

| Midwives | 0.932 | (0.786 to 1.10) | 0.934 | (0.788 to 1.11) |

| Public health nurse | 1.65 | (1.06 to 2.59) | 1.67 | (1.06 to 2.62) |

| Work | ||||

| Not working | Referent | Referent | ||

| Working | 0.802 | (0.658 to 0.976) | 0.886 | (0.725 to 1.08) |

| Region of residence | ||||

| Hokkaido | 1.66 | (1.08 to 2.54) | 1.64 | (1.07 to 2.52) |

| Tohoku | 1.02 | (0.848 to 1.23) | 0.986 | (0.817 to 1.19) |

| Kanto | Referent | Referent | ||

| Hokuriku_Koshin | 0.976 | (0.821 to 1.16) | 0.937 | (0.787 to 1.12) |

| Tokai | 1.03 | (0.842 to 1.26) | 0.988 | (0.807 to 1.21) |

| Kinki | 0.968 | (0.814 to 1.15) | 0.959 | (0.806 to 1.14) |

| Cyugoku | 0.967 | (0.790 to 1.18) | 0.925 | (0.755 to 1.13) |

| Shikoku | 0.977 | (0.794 to 1.20) | 0.956 | (0.775 to 1.18) |

| Kyusyu | 0.856 | (0.721 to 1.02) | 0.828 | (0.697 to 0.983) |

| Okinawa | 0.620 | (0.417 to 0.923) | 0.593 | (0.398 to 0.883) |

| Type of residence area* | ||||

| Not urban | Referent | Referent | ||

| Urban | 1.14 | (1.01 to 1.29) | 1.17 | (1.03 to 1.32) |

| Smoking | ||||

| Non-smoker | Referent | Referent | ||

| Smoker | 0.624 | (0.536 to 0.726) | 0.634 | (0.545 to 0.738) |

| Drinking | ||||

| <3 days a week | Referent | Referent | ||

| ≥3 days a week | 0.907 | (0.810 to 1.02) | 0.896 | (0.800 to 1.00) |

| Pregnancy† | ||||

| Not pregnant | Referent | Referent | ||

| Pregnant | 1.05 | (0.651 to 1.69) | 1.26 | (0.776 to 2.03) |

| Menopause† | ||||

| Not postmenopausal | Referent | Referent | ||

| Postmenopausal | 1.52 | (1.37 to 1.68) | 1.52 | (1.30 to 1.78) |

| Participation in previous survey | ||||

| Wave II not participated | Referent | Referent | ||

| Participated | 2.08 | (1.79 to 2.40) | 2.01 | (1.74 to 2.33) |

| Wave III not participated | Referent | Referent | ||

| Participated | 7.08 | (6.11 to 8.22) | 7.0 | (6.03 to 8.12) |

| Wave IV not participated | Referent | Referent | ||

| Participated | 17.7 | (14.9 to 21.1) | 17.5 | (14.7 to 20.9) |

*Urban areas are Tokyo metropolitan area and other 19 large cities designated by government ordinance.

†Data in latest available survey.

Regarding other factors that showed significant effects on the response by age-adjusted analyses, nursing licence, region of residence, type of residence area, smoking, menopause and participation in previous survey were associated with the odds of response.

Discussion

Timing of newsletter delivery and type of return envelope

Results of the present study showed that provision of the newsletters with the questionnaires tended to decrease the odds of returning the self-administered questionnaire. In addition, if the newsletters were provided to participants 6 weeks later with reminder letters, it would further keep participants (non-responders at that point) from returning their questionnaires. Thus, the results suggest that each practice, such as provision of information, request for collaboration and encouragement of contribution, should be managed individually, as separate events in advance. As prior studies3 10 documented that advanced contacts via letters, cards and phone calls increase the rates, if the update of the survey is offered via newsletter to respondents in advance, it may facilitate their understanding of the research issues and then improve response rates as well as enhance the quality of responses by reducing the number of items left blank or incomplete and decreasing inconsistent answers.

In the light of cost-performance, some studies suggest that allocating large sums of money to achieve high response rates may not always significantly improve the quality of the sample.13–15 Prior studies documented that with properly high response rates (approximately 70%), the bias due to non-response was unlikely to affect estimation of the survey.13–15 However, for a follow-up cohort survey like the JNHS, maintaining high follow-up response rates is crucial to maintaining the cohort.

Provision of a stamped return envelope had a significant effect of raising the odds of returning the questionnaire in the JNHS follow-up survey. Although there is an argument that providing stamped return envelopes is an inappropriate use of research expenses (especially for research with public funds) and is not cost-beneficial, it depends on the survey response rates that you expect to achieve. We should discuss about the cost-performance based on the results of an actual cost analysis.16 If we assume provision of stamped return envelopes, compared with business-reply envelopes for postpayment by the recipient, increases the response rate by 10%, in a case survey of 10 000 participants, when the response rate with business-reply envelope is 50%, assuming that the stamped return envelope approach can improve the odds of response by 10%, the business-reply approach is better in terms of cost-performance (table 3). However, if the response rate is 80% in a survey of 10 000 participants, mailing costs for the stamped return envelope approach and for business reply envelope approach will be 285 yen/response and 273 yen/response, respectively. Consequently, if the response rate is as high as 80%, the stamped return envelope approach will be more advantageous than the business-reply envelope approach in terms of cost-performance. In that case, providing stamped return envelopes is the best way for the JNHS to maintain the cohort with a better cost-performance.

Table 3.

Costs of business-reply envelope returns and stamped envelope returns

| Scenario-1 |

Scenario-2 |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business-reply envelope response rate=50% |

Stamped return envelope response rate=55% |

Business-reply envelope response rate=80% |

Stamped return envelope response rate=88% |

|||||||||

| Unit cost | Number | Total cost | Unit cost | Number | Total cost | Unit cost | Number | Total cost | Unit cost | Number | Total cost | |

| Cost of mailing | ||||||||||||

| Postal cost for mailing out survey packet | ¥120 | 10000 | ¥1200000 | ¥120 | 10000 | ¥1200000 | ¥120 | 10000 | ¥1200000 | ¥120 | 10000 | ¥1200000 |

| Stamp for return envelope | ¥120 | 10000 | ¥1200000 | ¥120 | 10000 | ¥1200000 | ||||||

| Cost for postpayment by the recipient | ¥135 | 5000 | ¥675000 | ¥135 | 8000 | ¥1080000 | ||||||

| Total cost | ¥1875000 | ¥2400000 | ¥2280000 | ¥2400000 | ||||||||

| Number of responses | 5000 | 5500 | 8000 | 8800 | ||||||||

| Cost per response | ¥375 | ¥436 | ¥285 | ¥273 | ||||||||

Other factors affecting the response

In addition to the effect of the type of return envelope and timing of the newsletter, the present analysis showed interesting points with regard to factors predicting the response to the survey. Participation in a previous survey increased the odds of responding to this survey. In particular, participants who were involved in the most recent survey were 18 times more likely to return the questionnaire (table 2). In addition, there appeared to be some differences in women's responses to the survey based on their residence regions. As shown in table 2, women living in Hokkaido were more likely than those living in Kanto to respond to the survey. In contrast, women living in Kyusyu and Okinawa were less likely to respond to the survey.

Women who experienced menopause were more likely to participate in the present survey, even after the odds were adjusted by age. The questionnaire of the JNHS included several items with respect to reproductive health-related issuers, such as pregnancy and menopause. Recognising the association of the research issues with women's personal experiences would promote their involvement in the study. In contrast, smokers in the previous survey were less likely to respond to the present questionnaire. Given a recent negative image of smoking and the public trends against smoking, smokers would be reluctant to answer questions with regard to their health. However, if this tendency becomes prominent, health effects of smoking could be underestimated, especially in later surveys.

Limitations

There are several limitations to the present study. A major one refers to generalisation of results. The cohort of the JNHS follow-up survey consists of female healthcare professionals with a nursing licence who agreed to participate in the survey by signing an informed consent form. It may be problematic to apply the results of the present analysis to a broader population. There is, however, a major advantage of the present analysis. The JNHS is a nationwide occupational cohort study in Japan, and drawing on data from the cohort study, we could randomly allocate items of research interest, that is, type of return envelopes and timing of newsletter delivery, within the survey population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Japanese Nursing Association (47 prefectures’ individual Nursing Associations) and Japan Society of Menopause and Women's Health for their collaboration in designing and conducting the Japan Nurses’ Health Study. We also thank the Independent Study Monitoring Committee, which periodically monitors the study process. The JNHS is supported partly by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B:22390128) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Contributors: KH was responsible for developing of study concept and design, and acquisition of data. CW, KN and KH performed the statistical analyses. CW interpreted the results of the data analyses and drafted the manuscript. All authors have been involved in revising and elaborating it critically in the intellectual context.

Funding: The present study is funded by the National Center for Child Health and Development (NCCHD), which is fully sponsored by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Institutional review boards of Gunma University and the National Institute of Public Health.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data sharing to other parties.

References

- 1.Hayashi K, Mizunuma H, Fujita T, et al. Design of the Japan Nurses’ Health Study: a prospective occupational cohort study of women's health in Japan. Ind Health 2007;45:679–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Chapter 7: cohort studies. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008:100–10 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al. Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: systematic review. BMJ 2002;324:1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison RA, Holt D, Elton PJ. Do postage-stamps increase response rates to postal surveys? A randomized controlled trial. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:873–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakash RA, Hutton JL, Jorstad-Stein EC, et al. Maximizing response to postal questionnaires—a systematic review of randomized trials in heart research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hembroff LA, Rusz D, Rafferty A, et al. The cost-effectiveness of alternative advance mailings in a telephone survey. Public Opin Q 2005;69:232–45 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babbie E. Chapter 9: survey research. In: The basics of social research. 4th edn. Thomson Wadsworth, Belmont, CA, USA, 2005:268–311 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenhammar C, Bokstorn P, Edlund B. Using different approaches to conducting postal questionnaires affected response rates and cost-efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1137–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brierley G, Richardson R, Torgerson DJ. Using short leaflets as recruitment tools did not improve recruitment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:147–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ, et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(3):MR000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barton J, Bain C, Hennekens CH, et al. Characteristics of respondents and non-respondents to a mailed questionnaire. Am J Public Health 1980;70:823–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steffen AD, Kolonel LN, Nomura AM, et al. The effect of multiple mailings on recruitment: the multiethnic cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomakers Prev 2008;17:447–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtin R, Presser S, Singer E. The effects of response rate changes on the index of consumer sentiment. Public Opin Q 2000;64:413–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teitler JO, Reichman NE, Sprachman S. Costs and benefits of improving response rates for a hard-to-reach population. Public Opin Q 2003;67:126–38 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keeter S, Miller C, Kohut A, et al. Consequences of reducing nonresponse in a national telephone survey. Public Opin Q 2000;64:125–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavelle K, Todd C, Campbell M. Do postage stamps versus pre-paid envelopes increase responses to patient mail survey? A randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.