Abstract

Kapβ2 (also called transportin) recognizes PY nuclear localization signal (NLS), a new class of NLS with a R/H/Kx(2–5)PY motif. Here we show that Kapβ2 complexes containing hydrophobic and basic PY-NLSs, as classified by the composition of an additional N-terminal motif, converge in structure only at consensus motifs, which explains ligand diversity. On the basis of these data and complementary biochemical analyses, we designed a Kapβ2-specific nuclear import inhibitor, M9M.

Ten different import karyopherin-βs (Kapβs, also called importin-βs)1 mediate trafficking of human proteins into the cell nucleus through recognition of distinct NLSs. Large panels of import substrates are known only for Kapβ1 (importin-β) and Kapβ2 (transportin)1,2. The substrate repertoire of each Kapβ and the functional consequences of pathway specificities are some of the main challenges in understanding intracellular signaling and trafficking. In the case of nuclear export, Crm1 inhibitor leptomycin B has been crucial for identifying many Crm1 substrates3,4. Such specific inhibitors of nuclear import could be invaluable for proteomic analyses to map extensive nuclear traffic, but none has been found.

Two classes of NLS are currently known: short, basic classical NLSs that bind the heterodimer Kapα–Kapβ1 (refs. 1,5), and newly identified PY-NLSs that bind Kapβ2 (ref. 2). PY-NLSs are 20- to 30-residue signals with intrinsic structural disorder, overall basic character, C-terminal R/K/Hx2–5PY motifs (where x2–5 is any sequence of 2–5 residues) and N-terminal hydrophobic or basic motifs. These weak but orthogonal characteristics have provided substantial limits in sequence space, enabling the identification of over 100 PY-NLS–containing human proteins2. Two subclasses, hPY-NLSs and bPY-NLSs, are defined by their N-terminal motifs: hPY-NLSs contain ϕG/A/Sϕϕ motifs (where ϕ is a hydrophobic residue), whereas bPY-NLSs are enriched with basic residues.

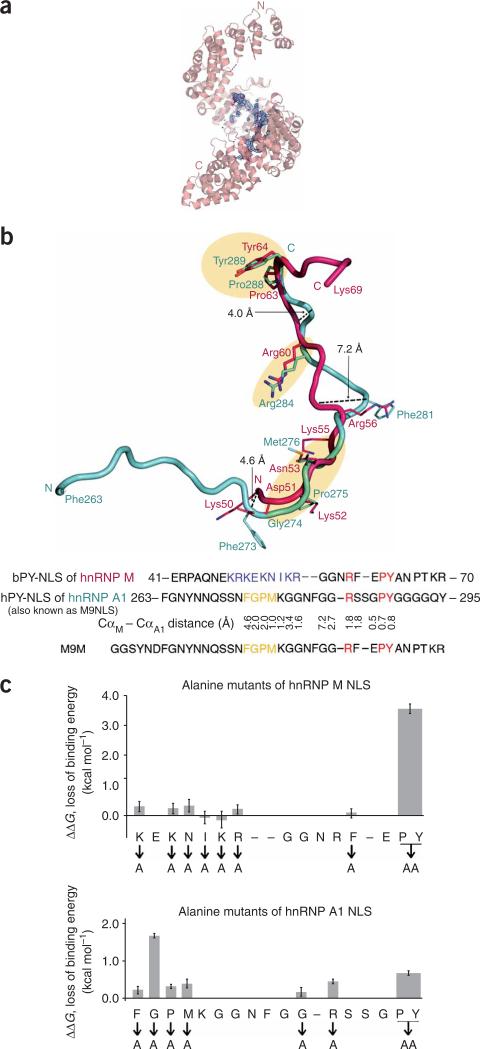

We have previously solved the structure of human Kapβ2 bound to the hPY-NLS of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNP A1)2. Here we have solved the 3.1-Å crystal structure of human Kapβ2 bound to the bPY-NLS of human hnRNP M2,6–8 (Fig. 1a,b, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 1 online) to compare structures of consensus NLS motifs and to understand how diverse hydrophobic or basic N-terminal motifs are recognized by Kapβ2. The two NLSs trace different paths while lining a common interface on the structurally invariant Kapβ2 C-terminal arch (Fig. 1a,b; Kapβ2435–780 Cα r.m.s. deviation is 0.9Å). Their NLS termini are structurally diverse, consistent with their apparent lack of sequence conservation2. At the N terminus, hnRNP A1 residues 263–266 bind the convex side of Kapβ2 (ref. 2), whereas the N terminus of hnRNP M proceeds toward the Kapβ2 arch opening. At the C terminus, hnRNP A1 is disordered beyond Pro288-Tyr289, whereas hnRNP M extends 5 residues beyond its Pro-Tyr motif.

Figure 1.

Kapβ2 bound to bPY-NLS of hnRNP M. (a) Ribbon model of Kapβ2 (pink), hnRNP M NLS (magenta) and the 2.5 σ Fo – Fc map (blue). (b) NLSs of hnRNP M (magenta) and hnRNP A1 (2H4M; blue) upon superposition of Kapβ2 residues 435–780. Regions of structural similarity are highlighted in yellow. Structurally aligned NLS sequences, Cα–Cα distances and inhibitor M9M sequence are shown. (c) Loss of Kapβ2-binding energy in alanine mutants of hnRNP A1 (ref. 2) and hnRNP M (ΔΔG = –RTln(Kd(WT)/Kd(mutant)); Kds determined by ITC).

Residues 51–64 of hnRNP M and residues 273–289 of hnRNP A1 contact a common Kapβ2 surface, with the highest overlap at their Pro-Tyr motifs (Fig. 1b). R.m.s. deviations for all Pro-Tyr atoms and for arginine guanido group atoms in the R/H/Kx(2–5)PY motifs are 0.9Å and 1.2Å, respectively, upon Kapβ2 superposition. At the N-terminal motifs, hnRNP M residues 51–54 in the basic 50-KEKNIKR-56 motif and hnRNP A1 residues 274–277 in the hydrophobic motif also overlap (main chain r.m.s. deviation 1.3Å). In contrast, intervening segments 61-FE-62 in hnRNP M and 285-SSG-287 in hnRNP A1, and those between the N-terminal and R/H/Kx(2–5)PY motifs, diverge up to 4.0Å and 7.2Å, respectively (Fig. 1b). Thus, the NLSs converge structurally at three sites: the N-terminal motif and the arginine and proline-tyrosine residues of the R/H/Kx(2–5)PY motif. These sites are key binding epitopes, confirming their designation as consensus sequences, and the structurally variable linkers vary in both sequence and length across the PY-NLS family. The multivalent nature of the PY-NLS–Kapβ2 interaction probably allows modulation of binding energy at each site to tune overall affinity to a narrow range suitable for regulation by nuclear RanGTP.

Despite a common Kapβ2 interface, functional groups in the hnRNP M basic 50-KEKNIKR-56 motif are very different from those in the hnRNP A1 hydrophobic 273-FGPM-276 motif. Most side chain interactions in the former are polar, whereas those in the latter are entirely hydrophobic. The corresponding Kapβ2 interface is highly acidic, with scattered hydrophobic patches. hnRNP A1 Phe273 and Pro275 in the hydrophobic motif make hydrophobic contacts with Kapβ2 Ile773 and Trp730, respectively. Similar hydrophobic contacts occur between the aliphatic portion of the hnRNP M Lys52 side chain and Kapβ2 Trp730, and between NLS Ile54, Kapβ2 Ile642 and aliphatic portions of Kapβ2 Asp646 and Gln685 (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). Other side chains in the hnRNP M sequence 50-KEKNIKR-56 form many polar and charged interactions with the acidic surface of Kapβ2. The relatively flat and open NLS-binding site on Kapβ2, together with its mixed acidic and hydrophobic surface, can accommodate diverse sequences, ranging from the hydrophobic segment in hPY-NLSs to basic groups in bPY-NLSs.

Despite structural conservation of key motifs, the distribution of binding energy along PY-NLSs is very different. In hnRNP A1, Gly274 is the only binding hot spot2,9–11, and the energetic contribution from the C-terminal Pro-Tyr is modest2,12. In contrast, the only hnRNP M NLS hot spot is at its Pro-Tyr motif (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2 online). Neither single alanine mutants in the 50-KEKNIKR-56 sequence nor a quadruple K50A E51A K52A N52A hnRNP M mutant had decreased affinity for Kapβ2, as measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Affinity decreased substantially only when all seven residues were mutated to alanines (Supplementary Table 2). Conformational flexibility suggested by high B-factors in this motif (Supplementary Table 1) may allow the remaining basic side chains in the mutants to reposition and compensate for truncated side chains. Furthermore, the large number of acidic and electronegative side chains on Kapβ2 may accommodate alternate conformations of the basic motif (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Thus, we predict that positive charge density rather than precise stereochemistry defines the basic motifs of bPY-NLSs.

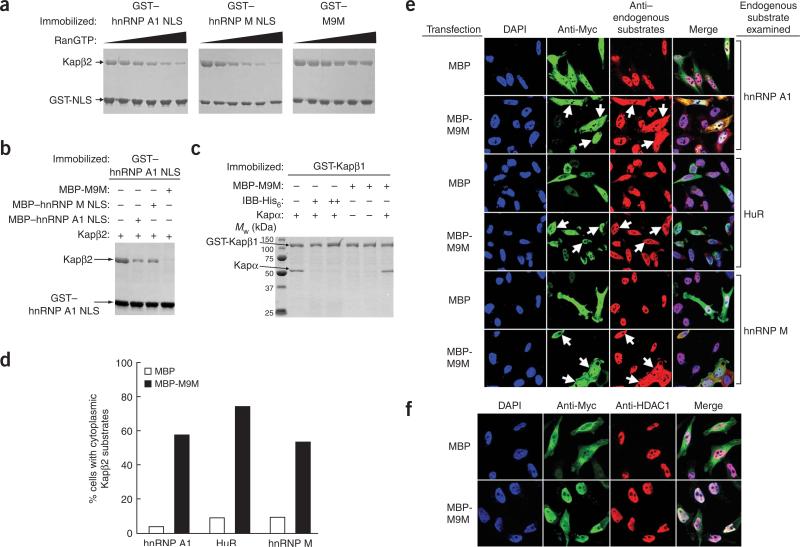

Asymmetric locations of NLS hot spots in hnRNP A1 and hnRNP M, and the presence of variable linkers between the sites, allowed the design of chimeric peptides with enhanced Kapβ2-binding affinities. A peptide that binds Kapβ2 with high enough affinity may compete with natural substrates and be resistant to Ran-mediated release in the nucleus13, and thus may function as a nuclear import inhibitor. We designed a peptide named M9M, which fuses the N-terminal half of the hnRNP A1 NLS to the C-terminal half of the hnRNP M NLS and thus contains both binding hot spots (Fig. 1b). When bound to Kapβ2, M9M shows decreased dissociation by RanGTP, competes effectively with wild-type NLS and binds specifically to Kapβ2 but not Kapβ1 (Fig. 2a–c), thus behaving like a Kapβ2-specific inhibitor. The mechanism of inhibition is explained by the 200-fold tighter binding of M9M to the PY-NLS binding site of Kapβ2 (competition ITC shows Kd of 107 pM, compared with 20 nM for hnRNP A1 NLS; Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 online). Transfection of M9M in HeLa cells mislocalizes the endogenous Kapβ2 substrates hnRNP A1, hnRNP M and HuR from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, but not the endogenous Kapα–Kapβ1 substrate HDAC1 (ref. 14) (Fig. 2d–f and Supplementary Fig. 5 online). Thus, M9M can specifically inhibit Kapβ2-mediated nuclear import in cells.

Figure 2.

M9M in vitro and in vivo inhibition studies. (a–c) Coomassie-stained gels of (a) glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusions of hnRNP A1 NLS, hnRNP M NLS and M9M bound to Kapβ2 and then dissociated by 0.3–1.6 μM RanGTP; (b) GST–hnRNP A1 NLS bound to Kapβ2 in the presence of buffer, maltose-binding protein (MBP)–hnRNP A1 NLS, MBP–hnRNP M NLS or MBP-M9M; (c) interactions of GST-Kapβ1 with Kapα, Kapα in the presence of importin-β–binding (IBB) domain of Kapα, M9M or Kapα in the presence of M9M. (d,e) Immunofluorescence and deconvolution microscopy of HeLa cells transfected with plasmids encoding Myc-tagged MBP or MBP-M9M, using anti-Myc and antibodies to hnRNP A1, hnRNP M and HuR. Histogram shows percentages of transfected cells with cytoplasmic Kapβ2 substrates. (f) Same as e, except localization of endogenous HDAC1 (Kapα–Kapβ1 substrate) is determined as control.

In summary, both bPY-NLSs and hPY-NLSs bind Kapβ2 in an extended conformation, with structural conservation at the arginine and proline-tyrosine residues of their C-terminal R/K/Hx2–5PY motifs and at their N-terminal basic or hydrophobic motifs. This confirms both the requirement for intrinsic structural disorder in PY-NLSs and the identification of N-terminal hydrophobic or basic and C-terminal R/K/Hx2–5PY consensus motifs. Finally, our discovery of asymmetric NLS binding hot spots in hnRNP M and hnRNP A1 led to the design of the M9M peptide, which binds Kapβ2 200-fold tighter than natural NLSs and specifically inhibits Kapβ2-mediated nuclear import in cells.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the University of Texas Southwestern's Structural Biology Laboratory, C. Thomas, N. Satterly, M. Matunis, M. Swanson, H. Yu, E. Seto and R. Bassel-Duby. The US Department of Energy, Offices of Science and Basic Energy Sciences (contract W-31-109-ENG-38) supported Advanced Photon Source use. Y.M.C. is funded by US National Institutes of Health grant R01-GM069909, Welch Foundation grant I-1532 and the University of Texas Southwestern Endowed Scholars Program, B.M.A.F. by US National Institutes of Health grant R01-GM067159-01.

Footnotes

Accession codes. Protein Data Bank: Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited with accession code 2OT8.

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology website.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Mosammaparast N, Pemberton LF. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee BJ, et al. Cell. 2006;126:543–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamamoto T, Gunji S, Tsuji H, Beppu T. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1983;36:639–645. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yashiroda Y, Yoshida M. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:741–748. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dingwall C, Laskey RA. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1991;16:478–481. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90184-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datar KV, Dreyfuss G, Swanson MS. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:439–446. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.3.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guttinger S, Mulhausser P, Koller-Eichhorn R, Brennecke J, Kutay U. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2918–2923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400342101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gattoni R, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2535–2542. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.13.2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fridell RA, Truant R, Thorne L, Benson RE, Cullen BR. J. Cell Sci. 1997;110:1325–1331. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.11.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakielny S, et al. Exp. Cell Res. 1996;229:261–266. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bogerd HP, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:9771–9777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iijima M, Suzuki M, Tanabe A, Nishimura A, Yamada M. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1365–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chook YM, Jung A, Rosen MK, Blobel G. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6955–6966. doi: 10.1021/bi012122p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smillie DA, Llinas AJ, Ryan JT, Kemp GD, Sommerville J. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:1857–1866. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.