Abstract

Campylobacter and Helicobacter species express a 6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine N-ribosylhydrolase (HpM-TAN) proposed to function in menaquinone synthesis. BuT-DADMe-ImmA is a 36 pM transition state analogue of HpM-TAN and the crystal structure of the enzyme-inhibitor complex reveals the mechanism of inhibition. BuT-DADMe-ImmA has a MIC90 value of < 8 ng/ml for H. pylori growth but does not cause growth arrest in other common clinical pathogens, thus demonstrating potential as an H. pylori-specific antibiotic.

Keywords: transition state analogue, BuT-DADMe-ImmA, 5′-methylthioadenosine nucleosidase, MTAN, Helicobacter pylori, Campylobacter jejuni, ulcers, antibiotics

H. pylori is a gram-negative bacterium and lives microaerophilically in the gastric mucosa of its human host. It is related to 85 percent of gastric and 95 percent of duodenal ulcers1. Drug resistance is prevalent in clinical isolates of H. pylori. After less than thirty years of antibiotic use in the patient population, it is increasingly difficult to eradicate H. pylori using a combination of two antibiotics with two weeks of therapy2. Antibiotics with new targets and mechanisms of action are needed to treat H. pylori infections.

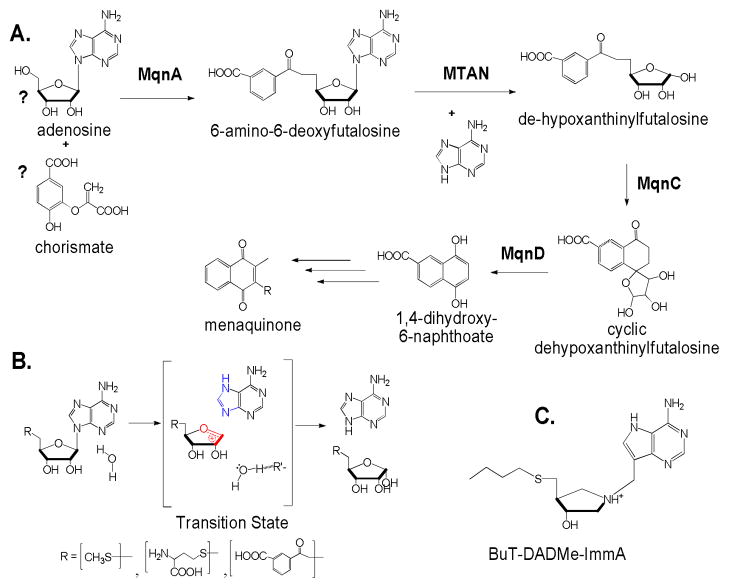

Gram negative bacteria are dependent on menaquinone as electron transporters and have an essential biosynthetic pathways for these critical metabolites3. In contrast, humans lack the pathway of menaquinone synthesis and targeting the menaquinone pathway may provide an anti-bacterial drug design approach. Recently, a menaquinone synthetic pathway has been proposed in Campylobacter and Helicobacter that differs from that found in most Gram negative bacteria4,5. In these unusual organisms, 6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine is synthesized by MqnA and cleaved at the N-ribosidic bond by a 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase (MTAN) with specificity including 5′-methylthioadenosine and adenosylhomocysteine as well as 6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine. HpMTAN converts 6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine to adenine and dehypoxanthine futalosine, the latter being used as the precursor of menaquinone synthesis (Fig. 1A). The early reactions of this pathway do not exist in the normal bacterial flora of humans, making the enzymes catalyzing these reactions appealing drug targets.

Figure 1.

Reactions catalyzed by MTANs, their proposed transition states and a transition state analogue inhibitor, BuT-DADMe-ImmA. A. Proposed early steps of the menaquinone pathway in H. pylori. The proposed substrates of MqnA reaction are labeled with question marks. B. Reaction catalyzed by HpMTAN and the proposed transition state. R′ is a proton abstracting group leading to the formation of hydroxide from water after the transition state is passed. Candidates are Glu13 and Glu175 (Fig. 2). Features of the transition state (blue and red) are represented in the BuT-DADMe-ImmA inhibitor in C.

HpMTAN is closely related to the MTANs found in other bacteria. In most bacteria MTANs are associated with quorum sensing and S-adenosylmethionine recycling but are not involved in menaquinone synthesis. In most species, MTAN is not essential for bacterial growth but are involved in quorum sensing6. Transition state analogue inhibitors of picomolar to femtomolar affinity have been developed to interrupt bacterial functions associated with quorum sensing6,7. We tested MTAN transition state analogues against HpMTAN to see if inhibition extended to this class of enzyme and to test if blocking HpM-TAN would block growth of H. pylori.

Transition states of several bacterial MTANs have been shown to have ribocationic character with minimal participation of the attacking water nucleophile and a N7-protonated, neutral adenine leaving group8–10. We assumed that the transition state of HpMTAN would be similar based on its homology to other MTANs (Fig. 1B) 4. Transition state analogues are known to bind tightly to their cognate enzymes11,12 by converting the dynamic protein motion involved in catalysis to a more stable thermodynamic state13.

BuT-DADMe-ImmA was previously characterized as a transition state analogue inhibitor of EcMTAN (Fig. 1C)8. Here, we performed inhibition assays using BuT-DADMe-ImmA against recombinant HpMTAN with 5′-methylthioadenosine as substrate. Purified HpMTAN uses both 5′-methylthioadenosine and 6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine as facile substrates. The enzyme exhibits low Km values for both substrates, 0.6 ± 0.3 and 0.8 ± 0.3 HM and kcat values of 12.1 ± 2.3 and 4.3 ± 0.9 s−1, respectively. This gives high catalytic efficiency values (kcat/Km) of 2.0 × 107 M−1s−1 for 5′-methylthioadenosine and 5.4 × 106 M−1s−1 for 6-amino-6-deoxy-futalosine. BuT-DADMe-ImmA is a slow-onset tight-binding inhibitor with an initial inhibition constant (Ki) of 0.8 nM and following slow-onset of inhibition, an equilibrium dissociation constant (Ki* = Kd) of 36 pM (see Supporting Information). With a Km value of 0.8 HM for 6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine as substrate, the Km/Kd ratio is 22,200 for this substrate. The low Kd value supports the proposal that BuT-DADMe-ImmA is a transition state analogue inhibitor for HpMTAN. A comparison of the structures of the 5′-methylthioadenosine or S-adenosylhomocysteine substrates for HpMTAN with their transition states (Fig. 1B) shows three features of BuT-DADMe-ImmA that mimic the transition states; a hydroxyl-pyrrolidine moiety, a methylene bridge between the base and sugar, and 9-deazaadenine (Fig. 1B and 1C). The nitrogen of the hydroxypyrrolidine moiety has a pKa value of 9, and thus mimics the positive charge of a ribocation at the transition state. The methylene bridge extends the distance between the sugar and the purine base leaving group, as this distance is near 3 Å at the transition state. The 9-deazaadenine alters conjugation in the purine ring, causing an elevated pKa and protonation of N7, resembling the N7-protonated adenine leaving group at the transition state.

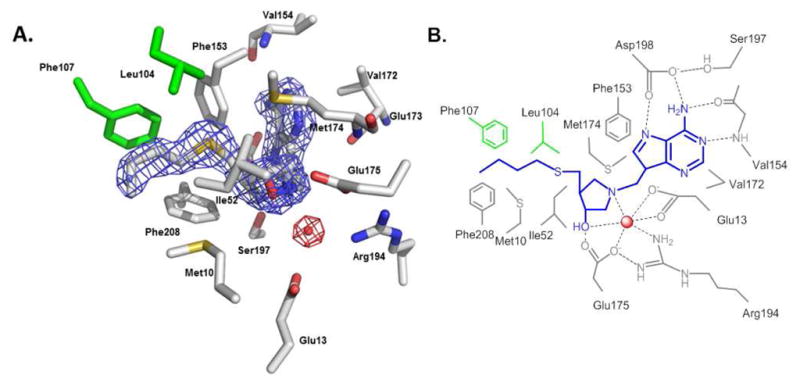

Catalytic site features involved in tight binding of BuT-DADMe-ImmA, were established from the crystal structure of HpMTAN in complex with BuT-DADMe-ImmA (Fig. 2). Like other MTANs, HpMTAN is a homodimer belonging to the superfamily of purine and uridine phosphorylases with the active sites located at the dimer interface (Fig. S1). Adenine binding is stabilized by hydrogen bods between N7 and OG2 of Asp198, and between N1 and the main chain NH of Val154. The hydrophobic group at the 5′-ribosyl position binding site is not tightly constrained, but is surrounded by a hydrophobic environment, allowing variation at this position (Fig. 2A and S1). Direct interactions between BuT-DADMe-ImmA and HpMTAN include five hydrogen bonds and a large number of hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 2). The transition state analogue complexes of MTANs include the nucleophilic water molecule in crystal structures and in complexes detected by mass spectrometry in the gas phase14,15. In HpMTAN, the nucleophilic water molecule is found 2.6 Å away from the cationic hydroxypyrrolidine nitrogen, the site of water attack in the ribocation transition state (Fig. 2). The water molecule is stabilized in HpMTAN by four hydrogen bonds from protein with two from bound BuT-DADMe-ImmA, contacts clearly contributing to the high affinity of the inhibitor complex.

Figure 2.

Active site of HpMTAN in complex with BuT-DADMe-ImmA. A. Crystal structure of the active site of HpM-TAN with bound BuT-DADMe-ImmA. The figure shows a 2Fo − Fc map around the inhibitor (blue grid) and catalytic water molecule (red grid) contoured at 1.5 σ. The graph was generated using Pymol. B. Schematic representation of interactions between BuT-DADMe-ImmA (blue), a water molecule (red sphere) and residues of HpMTAN. The residues shown in green belong to the neighboring monomer of HpMTAN dimer. Dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds. All hydrogen bonds are 3 Å or less except for three shown to water (3′-OH 3.1 Å; Glu175 3.3 Å; Glu13 3.2 Å).

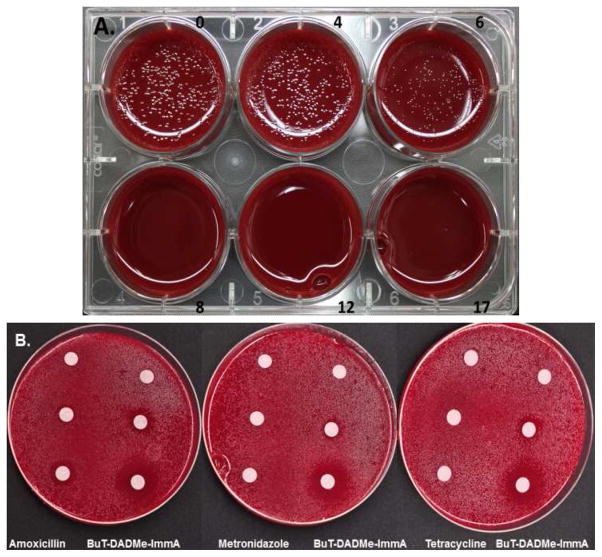

We tested the effects of BuT-DADMe-ImmA on H. pylori growing on 5% horse blood agar. At 6 ng/ml, slight growth was detected and at 8 ng/ml, no growth was detected, therefore the MIC90 value for inhibition of H. pylori growth is < 8 ng/ml (Fig. 3A). The MIC90 value of 8 ng/ml corresponds to a chemical concentration of 23 nM, sufficient to saturate HpMTAN with its Kd value of 36 pM.

Figure 3.

The effects of BuT-DADMe-ImmA on H. pylori growth. A. The effects of increasing the concentration of BuT-DADMe-ImmA (ng/ml) on growth on blood agar (one of five experiments in triplicate). B. The inhibitory effects of BuT-DADMe-ImmA are compared with amoxicillin, metronidazole and tetracyclin in zone of inhibition studies. Drug quantities per disk were: 0 (top disc), 10 ng (middle disc) or 20 ng (bottom disc). Each specified antibiotic was applied to the disc in the same manner. Small zones of inhibition were seen with 10 ng BuT-DADMe-ImmA (middle right), and large zones at 20 ng (lower right).

Commonly used antibiotics in H. pylori infections include amoxicillin, metronidazole and tetracycline. We compared the anti-H. pylori effects of BuT-DADMe-ImmA to those antibiotics in common use. The zones of inhibition for BuT-DADMe-ImmA are greater than those for any of the other antibiotics (Fig. 3B). Equivalent amounts of amoxicillin gave a smaller zone of growth inhibition than BuT-DADMe-ImmA, and equivalent amounts of metronidazole or tetracycline gave no growth inhibition. Thus, BuT-DADMe-ImmA is more efficient at inhibition of H. pylori growth than commonly used antibiotics.

In most bacteria, MTANs are expressed and catalyze the hydrolysis of the N-ribosidic bonds of 5′-methylthioadenosine and S-adenosylhomocysteine. The two reactions are involved in bacterial quorum sensing, sulfur recycling via S-adenosylmethionine and polyamine synthesis16, however, most bacterial MTANs are not essential for bacterial proliferation as judged by planktonic growth conditions.. Thus, BuT-DADMe-ImmA did not affect the growth of E. coli and V. cholerae, although MTAN activity was totally abolished6. Likewise, mtn gene deletion in E. coli does not affect growth on rich medium but creates biotin auxotrophs6,17. We also tested the effects BuT-DADMe-ImmA on the growth of other clinically common pathogens, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, S. flexneri, S. enterica and P. aeruginosa. At culture concentrations with BuT-DADMe-ImmA to 5 Hg/ml, no growth inhibition was observed for those bacteria, consistent with a non-essential role for their MTANs. Because of the inhibitor specificity for this rare menaquinone pathway, treatment of H. pylori infections with BuT-DADMe-ImmA would be unlikely to generate antibiotic resistance in off-target bacterial species.

Bacterial genome analysis predicts the HpMTAN-mediated pathway for menaquinone biosynthesis to be rare, but also to be present in Campylobacter species4. Campylobacter jejuni is the world’s leading cause of bacterial gastroenteritis18.

The action of HpMTAN is proposed to be in the hydrolysis of 6-amino-6-deoxyfutalosine, and we specifically tested the enzyme for this function. The enzyme shows robust catalytic activity on this substrate with a catalytic efficiency of 5.4 × 106 M−1s−1. The effects of BuT-DADMe-ImmA on the enzyme and growth of H. pylori demonstrates a critical role of HpM-TAN in H. pylori, and supports the proposed pathway of an essential menaquinone biosynthetic pathway for its electron transfer chain or other function4,19.

Drug resistance has developed quickly in H. pylori, and currently, approximately 30% of H. pylori infection are resistant to single-agent first line drugs20. As a result, the current approach commonly uses triple-agent therapy for H. pylori infections and includes two antibiotics with different mechanisms of action. Even with triple-agent therapy, more than 20% of H. pylori infections are not readily eradicated2. Resistance in the H. pylori population is no doubt partially due to exposing H. pylori to broad spectrum antibiotics during the treatment of other bacterial infections. In addition, current eradication of H. pylori requires antibiotics for two weeks or longer and increases the probability of resistance development if treatment is interrupted. The results with BuT-DADMe-ImmA indicate potential as a narrow spectrum antibiotic, with the opportunity for trials as a single agent or in drug combinations. The drugability of BuT-DADMe-ImmA has yet to be established. However, a similar compound with a thiomethyl-, rather than a thiobutyl- substituent is orally available and shows low toxicity in mice21.

The other pathogens (Campylobacter species) in which MTAN also appears to be essential, are currently treated clinically with ciprofloxacin, erythromycin or azithromycin. BuT-DADMe-ImmA is a more powerful antibiotic for its target in H. pylori than other antibiotics are for their targets. Thus BuT-DADMe-ImmA could also be a candidate for Campylobacter infections. Thus BuT-DADMe-ImmA has potential as a specific antibiotic in organisms using MTANs in any essential biosynthetic step. Drug combinations using BuT-DADMe-ImmA may also address current issues of antibiotic resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grant GM41916 (to V.L.S.) and a fellowship grant from the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (to A.M.H.). Support for the crystallography study was provided by the Center for Synchrotron Biosciences grant, P30-EB-009998, from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB). Data for this study was measured at beamline X29A, part of the Case Center for Synchrotron Biosciences (CCSB) located at the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratories, New York. The authors V.L.S, P.C.T. & G.B.E. declare the following financial interest. The Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Industrial Research Ltd., own joint patents in regard to the synthesis and use of BuT-DADMe-ImmA. The patent owners are seeking commercial licensees for development of this technology.

Footnotes

Accession codes

Protein Data Bank: The crystal structure of HpMTAN in complex with BuT-DADMe-ImmA is deposited under accession code 4FFS.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supplementary information is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org. Requests for materials should be addressed to V.L.S.

References

- 1.Kuipers EJ, Thijs JC, Festen HP. Aliment Pharm Therap. 1995;9(Suppl 2):59–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malfertheiner P, et al. Lancet. 2011;377:905–913. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popp JL, Berliner C, Bentley R. Anal Biochem. 1989;178:306–310. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X, Apel D, Gaynor EC, Tanner ME. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19392–19398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.229781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dairi T. J Antibiot. 2009;62:347–352. doi: 10.1038/ja.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutierrez JA, et al. Nature Chem Biol. 2009;5:251–257. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longshaw AI, et al. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6730–6746. doi: 10.1021/jm100898v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh V, et al. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18265–18273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh V, Schramm VL. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2783–2795. doi: 10.1021/ja065082r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutierrez JA, et al. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:725–734. doi: 10.1021/cb700166z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfenden R. Nature. 1969;223:704–705. doi: 10.1038/223704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radzicka A, Wolfenden R. Science. 1995;267:90–93. doi: 10.1126/science.7809611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schramm VL. Ann Rev Biochem. 2011;80:703–732. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-100742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1468–1470. doi: 10.1021/ja211176q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh V, Lee JE, Nunez S, Howell PL, Schramm VL. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11647–11659. doi: 10.1021/bi050863a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parveen N, Cornell KA. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:7–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi-Rhee E, Cronan JE. Chem Biol. 2005;12:589–593. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Man SM. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:669–685. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcelli SW, et al. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;138:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vakil N. Am J Gastro. 2009;104:26–30. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basu I, et al. J Biol Chem. 286:4902–4911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.198374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.