Abstract

Objective This study examined whether racial identity moderates the relation between pain and quality of life (QOL) in children with sickle cell disease (SCD). Methods 100 children 8–18 years of age with SCD participated during a regularly scheduled medical visit. Children completed questionnaires assessing pain, QOL, and regard racial identity, which evaluates racial judgments. Results Analyses revealed that regard racial identity trended toward significance in moderating the pain and physical QOL relation, (β = −0.159, t(93) = −1.821, p = 0.07), where children with low pain and high regard reported greater physical QOL than children with low pain and low regard. Regard racial identity did not moderate the relation between pain and other QOL dimensions. Pain significantly predicted all dimensions of QOL and regard racial identity significantly predicted social QOL. Conclusions Racial identity may be important to consider in future research examining QOL in children with SCD.

Keywords: children, pain, quality of life, racial identity, sickle cell disease

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of autosomal recessive genetic disorders, primarily found in people of African descent. SCD affects ∼1 in 500 African Americans (Lemanek & Ranalli, 2009) and >89,000 children and adults have the disease in the United States (Brousseau, Panepinto, Nimmer, & Hoffmann, 2010). SCD is characterized by the presence of abnormal beta globin gene, with HbSS being the most common and severe genotype, whereas less common genotypes are HbSC and HbS beta thalassemia (Lemanek & Ranalli, 2009). The presence of abnormal hemoglobin genes causes red blood cells to become rigid and crescent shaped (i.e., sickle-shaped), which hinders blood flow, resulting in physical complications including vaso-occlusive pain crises (VOCs), jaundice, stroke, infection, delayed puberty, and short stature [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2011]. Yet, the most common and debilitating symptom associated with SCD is pain (Barakat, Lash, Lutz, & Nicolaou, 2006).

VOCs are unpredictable and occur in children with SCD about five to seven times a year, last from one to three days (Lemanek & Ranalli, 2009) and may require hospitalization (Shapiro et al., 1995). In pediatric patients with SCD, common locations of pain include the legs, hips, and back (Dampier, Ely, Brodecki, & O’Neal, 2002). Acute pain crises often interfere with academic functioning, social activities, and sleep (Gil et al., 2000; Shapiro et al., 1995). In addition to VOCs, chronic pain related to SCD can be due to aseptic necrosis, shrinking vertebrae, and poor circulation (Ballas, 1998; Schecter, 1999). Significant advances in the diagnosis and treatment of SCD have led to increases in the life span of patients (Eiser & Morse, 2001), which has prompted researchers to focus on quality of life (QOL).

QOL is a multidimensional, patient-centered construct that includes several domains, such as physical, emotional, and social functioning, as well as performance of daily activities and disease-related symptoms (Panepinto, O’Mahar, DeBaun, Loberiza, & Scott, 2005; Quittner, 1998). Based on parent report, African American children with SCD have poorer overall QOL compared to healthy African American children (Palermo, Schwartz, Drotar, & McGowan, 2002). Research with SCD and other pediatric populations suggests that children and parents offer unique perspectives about the impact chronic illnesses may have on QOL (Eiser & Morse, 2001; Panepinto et al., 2005). Thus, there is added value to assessing children’s report of their own QOL. Research indicates that pain is a significant predictor of QOL in children with SCD (Anie, Steptoe, & Bevan, 2002). However, psychosocial factors may buffer the relation between pain and QOL in this population (Barakat, Patterson, Daniel, & Dampier, 2008; Barbarin, Whitten, Bond, & Conner-Warren, 1999; Palermo, Riley, & Mitchell, 2008). Racial identity may be one factor that might moderate the pain and QOL relation.

In general, cultural factors influence how children adjust to chronic illnesses (e.g., Clay, Mordhorst, & Lehn, 2002; Gurung, 2006). The experience of pain has been found to differ based on cultural factors (Craig & Riddell, 2003; Lasch, 2000). Differences between racial groups have been identified as one way to examine the impact of culture. For example, in adults, racial differences in pain tolerance and pain catastrophizing have been found (Forsythe, Thorn, Day, & Shelby, 2011). Racial identity may be particularly relevant to consider in SCD given that previous findings have linked it to pain and functioning in adult patients (Barbarin & Christian, 1999).

Racial identity has been conceptualized as a person’s group or collective identity based on perceptions that they share a common heritage with a specific racial group (Chavez & Guido-DiBrito, 1999). The Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (MMRI; Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997; Sellers et al., 1998) provides a framework for researchers to investigate racial identity in African Americans. The MMRI posits that racial identity is the significance and meaning people place on being a member of the Black racial group which is incorporated into their self-concept (Scottham, Sellers, & Nguyen, 2008; Sellers et al., 1998).

In adults with SCD, racial identity has been found to be negatively associated with pain severity ratings, suggesting that positive racial identity might enhance health (Bediako, Lavender, & Yasin, 2007). Another study found that parents’ with more positive racial identity had children with SCD who had better psychological functioning (Barbarin, 1999). As positive racial identity is associated with better psychological health (Bediako et al., 2007), it might positively influence physical health. On the other hand, African Americans who encounter discrimination are at risk for poorer physical and mental health outcomes (e.g., Brondolo et al., 2011), and these experiences could impact appraisals and attributions about one’s race (e.g., racial identity). Although data suggest that racial identity might be an important variable in health research, no study to date has examined racial identity in African American children with SCD.

The purpose of the present study was to describe and examine racial identity in African American children with SCD and to evaluate whether it moderates the pain and QOL relation. It was hypothesized, based on the adult SCD literature, that positive racial identity would buffer the negative impact of pain on QOL. Specifically, it was expected that children experiencing pain with more positive racial identity would report better QOL than those with a less positive view of African Americans. In addition, it was expected that pain and racial identity would act as independent predictors of QOL.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 100 children diagnosed with SCD ranging from 8 to 18 years of age (M = 13.0 years, SD = 3.2 years) and their parents who were attending a regularly scheduled outpatient SCD-related medical visit at two children’s hospitals in the southeastern United States (see Table I.). All children were identified by their parents as African American or Black, more were female (53%), and 69% had HbSS (sickle cell anemia) genotype of SCD.

Table I.

Demographic Information for Children and Parents (N = 100)

| M (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Child demographic characteristics | |

| Age | 13.0 (3.2) |

| Gender | N |

| Female | 53 |

| Male | 47 |

| Race or ethnicity | N |

| African American or black | 100 |

| SCD type | N |

| HbSS | 69 |

| HbSC | 13 |

| Beta Thalassemia | 6 |

| Type not specified | 12 |

| Parent demographic characteristics | |

| Age | 41.0 (8.1) |

| Gender | N |

| Female | 87 |

| Male | 13 |

| Relationship to child | N |

| Mother | 85 |

| Father | 8 |

| Grandmother | 3 |

| Grandfather | 2 |

| Stepfather | 2 |

| Race or ethnicity | N |

| African American | 99 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 |

| Marital status | N |

| Married or partnered | 56 |

| Single | 24 |

| Divorced or separated | 19 |

| Missing | 1 |

| Education level [M (SD) in years] | 13.8 (2.1) |

| Median family income | $40,001–50,000 |

Note. SCD = Sickle cell disease.

Most children were accompanied by their mother (85%). Parents ranged in age from 28 to 68 years (M = 41.0, SD = 8.1) and 99 identified as African American. Ninety-two parents reported their annual family income. Median family income for the sample ranged from $40,001 to $50,000. Parents reported 13.8 (SD = 2.1 years) average years of education, and the majority (56%) were married.

One hundred and fifteen families were approached to participate. Nine families (7.8%) refused to participate. Reasons for nonparticipation included not being interested in taking part in research (n = 7) and not having enough time (n = 2), resulting in 106 participants enrolled. However, two children (1.9%) did not complete the main outcome measures due to time constraints, and four children were not identified as African American and did not complete the racial identity measure. These participants were removed from analyses. The final sample consisted of 100 children with SCD and their parents, resulting in an 87% participation rate.

Measures

Background Information

Parents who accompanied children for their regularly scheduled SCD-related medical visit completed a background history form. Questions included child and caregiver age, child and caregiver races or ethnicities and genders, family income, and child current disease (e.g., type of SCD and SCD-related hospitalizations) status.

Pain

The Pediatric Pain Questionnaire (PPQ; Varni, Thompson, & Hanson, 1987) was used to assess children’s perceptions of pain. The PPQ is a structured measure that consists of visual analog scales (VAS) and open-ended questions. The PPQ VAS is a 100 mm horizontal line that measures present pain and worst pain in the past week. The VAS questions are anchored at each end with developmentally appropriate pain descriptions (e.g., no pain). Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing more pain. The PPQ has been deemed a “well-established” instrument for assessing pain in children 5–18 years of age (Cohen et al., 2008) and has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in children with SCD (Walco & Dampier, 1990). An additional VAS item was added to the PPQ in order to assess chronic pain by asking children to indicate the “general or normal pain” they experienced in the past week. Given that pain associated with SCD is both acute and chronic (Lemanek & Ranalli, 2009), we took the average of the two VAS pain ratings from the PPQ and the additional item: current (pain now), acute (worst pain), and chronic (normal or general pain), in order to include a global estimate of the multiple types of pain children with SCD may experience. This average score (overall pain) was used in primary analyses. The Cronbach’s alpha for the three pain ratings was 0.80.

Racial Identity

To assess children’s racial identity the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI; Sellers et al., 1997) was used, which consisted of 12 items from the regard scale of the measure. The MIBI regard scale assesses both private regard and public regard. Private regard refers to one’s own views of African Americans and membership in that racial group (Sellers et al., 1997). Public regard refers to one’s perceptions of others views of African Americans (Sellers et al., 1997). Children rated how strongly they agreed or disagreed with each item on a likert scale with scores ranging from 1 to 7 (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating more positive attitudes toward African Americans. The MIBI is valid and reliable in a sample of African American college students, with Cronbach’s alpha for both the public and private regard scales being 0.78 (Sellers et al., 1997). Since the MIBI was originally developed for adults, some items were modified to help children better understand them. For example, an item from the public regard scale, “Society views Black people as an asset” was reworded to include a synonym, “Society views Black people as an asset (e.g., benefit).” The revised items were then pilot tested with a patient with SCD to ensure clarity before data collection began. In this sample, internal consistency of the regard scale, which was used in primary analyses, was 0.77.

Quality of Life

The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL; Varni, Seid, & Kurtin, 2001) was completed by children to assess their QOL. The PedsQL is a 23-item QOL measure designed for children and adolescents. The PedsQL assesses physical (eight items), emotional (five items), social (five items), and school (five items) functioning and utilizes a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never a problem to 4 = almost always a problem). Scores on the PedsQL are transformed to scores ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing higher QOL. In addition to having specific scaled scores, the items on the PedsQL are averaged to create a total scale score. The PedsQL is valid and reliable for use with children and adolescents (Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.68 to 0.88) (Varni, Seid, & Kurtin, 2001) and is considered “well-established” (Palermo, Long, Lewandowski, Drotar, Quittner, & Walker, 2008). In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the PedsQL total score was 0.91 and for subscales ranged from 0.69 (School) to 0.86 (Physical). The PedsQL total score and subscale scores were used in primary analyses.

Disease Severity

At the end of the medical appointment, the SCD clinic nurse who conducted vitals and performed an initial health assessment on the child during their medical visit answered one 100 mm VAS, with anchors not at all to worst possible, to assess the patient’s disease severity. Nurses were instructed to indicate, “In general, how severe would you rate this child/adolescent’s sickle cell disease?” by making a tick mark along the 100 mm line. Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater disease severity. Previous research has demonstrated that provider ratings of disease severity via VAS are significantly correlated with objective ratings (i.e., hemoglobin levels and ER visits) in pediatric SCD (Connelly et al., 2005) and was significantly correlated with child report of pain in this study [r(100) = .23, p < 0.05].

Procedures

Children scheduled to receive regular outpatient SCD-related medical care at two urban children’s hospitals in a southeastern city, and their parents were informed of the study by clinic personnel and directed to receive additional information from a trained research assistant. Children with significant cognitive delays as determined by the medical staff were not eligible to participate. The trained research assistant explained the study and obtained parent consent and child assent. Before meeting with physicians, the child and parent completed measures in a quiet room in the clinic. Children completed the PPQ, MIBI, and PedsQL. Parents completed the demographic questionnaire. Children and parents were compensated ($5 gift cards) for their participation. After the completion of the clinic visit, the SCD nurse who worked with the child completed a VAS to rate the child’s disease severity.

Data Analysis Plan

Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine the normative distribution of the main study variables and to examine whether there were differences between the two data collection sites. Additional analyses were conducted to examine whether there were statistically significant associations between demographic (i.e., gender, age, parent marital status, and family income), disease severity, and main outcome variables, as well as examined intercorrelations between pain, QOL, and racial identity. Hot deck imputations based on child gender and site were conducted for main variables with missing data (Myers, 2011).

As part of the primary analyses, we conducted hierarchical linear regressions to examine whether regard racial identity (regard) moderated the association between pain (overall pain) and overall QOL (PedsQL total score). Additional hierarchical regressions were also conducted to analyze the domains of QOL as the dependent variable. Main effects of overall pain and regard were examined after significant interactions were interpreted. Significant interactions between overall pain and Regard were followed up by using methods outlined by Aiken and West (1991) and Holmbeck (2002). Covariates for each analysis were entered in Step 1. In Step 2, the centered main effects of overall pain and regard were entered. The interaction between pain and regard was then included in Step 3. Significant interactions were plotted by regressing QOL (y) on pain (x), as a function of two values of the significant moderator, ZL and ZH (i.e., 1 SD below the mean and 1 SD above the mean, respectively). Standardized B was used to calculate regression lines.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Preliminary analyses revealed acceptable normative distributions for the main outcome variables, and descriptive statistics are presented in Table II. Information from these analyses suggests that children with SCD report similar levels of racial identity as healthy African American children (Scottham, Sellers, & Nguyen, 2008; Yip, Seaton, & Sellers, 2006). Children across these studies report that being African American is an important part of their identity. Children’s reports of pain were similar to previous studies utilizing smaller sample sizes (Graumlich, Powers, Byars, Schwarber, Mitchell, & Kalinyak, 2001; Walco & Dampier, 1990). In addition, QOL in this sample was similar to children with SCD with no medical history of recent pain episodes (McClellan et al., 2008), which was expected given that children in this study were attending a regularly scheduled SCD clinic visit.

Table II.

Descriptive Statistics for Main Study Variables

| Descriptive statistics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Measures | M (SD) | Range |

| Overall pain (PPQ) | 21.22 (24.66) | 0–99.33 |

| Quality of life (PedsQL) | ||

| Total | 70.21 (16.21) | 26.09–100 |

| Physical | 67.97 (21.10) | 15.63–100 |

| Emotional | 71.60 (20.01) | 20.00–100 |

| Social | 79.80 (19.10) | 25.00–100 |

| School | 61.60 (19.25) | 10.00–100 |

| Regard racial identity (MIBI) | 5.37 (0.81) | 2.50–6.92 |

| Disease severity | 55.92 (23.30) | 4.00–98.00 |

Notes. PPQ = pediatric pain questionnaire; PedsQL = pediatric quality of life inventory; MIBI = multidimensional inventory of Black identity.

Chi-square analyses revealed that the two hospital sites did not differ on child gender (χ2 = .33, p = .56), type of SCD (χ2 = 2.70, p = .44), parent marital status (χ2 = 4.47, p = .11), parent education (χ2 = 4.53, p = .72), or family income (χ2 = 12.56, p = .18). Analyses with t-tests revealed no significant differences between sites on child age [t(98) = −.92, p = .36]. In regard to the main outcome variables, t-tests revealed no site differences on overall pain [t(98) = −.64, p = .52] or regard [t(98) = .39, p = .74]. Yet, there were site differences on the PedsQL total, physical, and school scales [total: t(98) = 2.85, p = 0.005; physical: t(98) = 2.92, p = 0.004; school: t(98) = 2.36, p = 0.02], where children from the second site reported significantly lower QOL compared to children from the first site. One possible reason for these differences is the unequal number of participants from each site that were recruited during an SCD specialty clinic for treatment of an SCD-related medical complication. More children (n = 22) from the second site were attending a pulmonary SCD clinic compared to children from the first site (n = 13). In addition, four children from the second site were recruited while attending an SCD pain specialty clinic, while no children from the first site were recruited while attending this type of clinic. However, nurses from the first site rated children at that site as having worse disease severity compared to nurses at the second site, t(98) = −3.19, p = 0.002. Due to site differences on QOL and disease severity, site of participation was entered as a covariate in primary analyses.

T-tests examining potential gender differences revealed no significant differences on overall pain [t(98) = −1.51, p = .13] or regard [t(98) = 1.42, p = .16]. However, males reported higher QOL on the PedsQL total, physical, and emotional scales than females [total: t(98) = 2.32, p = 0.02; physical: t(98) = 2.39, p = 0.02; emotional: t(98) = 2.57, p = 0.01]. Therefore, gender was also entered as a covariate in primary analyses.

Correlations examining child age, disease severity, and intercorrelations between variables are presented in Table III. Results revealed that child age was significantly positively correlated with the PedsQL social scale and disease severity. Disease severity was also significantly positively associated with overall pain and negatively associated with the PedsQL total and physical scales. Therefore, child age was controlled for in analyses where the PedsQL social scale was the dependent variable, and disease severity was entered as a covariate in all primary analyses. Significant negative correlations were also found between overall pain and the PedsQL total and all subscales, with children who reported higher pain also reporting lower QOL. Regard was significantly positively correlated with the PedsQL social subscale and was approaching significance on the PedsQL total, physical, and emotional subscales.

Table III.

Correlations between Age, Disease Severity, and Main Study Variables

| Correlations | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child age | – | ||||||||

| 2. Disease severity | 0.36*** | – | |||||||

| 3. Overall pain (PPQ) | 0.11 | 0.23* | – | ||||||

| 4. PedsQL total | 0.01 | −0.20* | −0.48*** | – | |||||

| 5. PedsQL physical | −0.04 | −0.27** | −0.44*** | 0.87*** | – | ||||

| 6. PedsQL emotional | −0.02 | −0.11 | −0.40*** | 0.81*** | 0.58*** | – | |||

| 7. PedsQL social | 0.24* | −0.04 | −0.30** | 0.75*** | 0.53*** | 0.50*** | – | ||

| 8. PedsQL school | −0.05 | −0.17† | −0.36*** | 0.79*** | 0.56*** | 0.57*** | 0.56*** | – | |

| 9. Regard racial identity (MIBI) | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.19† | 0.18† | 0.18† | 0.21* | 0.11 | – |

Notes. PPQ = pediatric pain questionnaire; PedsQL = pediatric quality of life inventory; MIBI = multidimensional inventory of Black identity. †p < 0.10. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

Primary Analyses

Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine whether racial identity moderates the relation between pain and QOL (see Table IV). Results revealed that the main effect of overall pain was a significant predictor of the PedsQL total scale, β = −0.44, t(93) = −5.04, p < 0.001. Thus, children who reported higher pain also reported lower overall QOL. There was no significant main effect of regard or a significant overall pain × regard interaction on the PedsQL total scale. Results examining the PedsQL emotional and school scales as the dependent variable revealed similar results, where overall pain was a significant predictor [PedsQL emotional: β = −0.37, t(93) = −3.90, p < 0.001; PedsQL school: β = −0.33, t(93) = −3.15, p = 0.002], but the main effect of regard and the interaction was not significant. However, on the PedsQL social scale, overall pain and regard were significant predictors [overall pain: β = −0.30, t(92) = −3.15, p = 0.002, regard: β = 0.19, t(92) = 2.05, p = 0.04], with higher pain associated with lower social QOL and more positive regard racial identity associated with higher social QOL. There was no significant overall pain × regard interaction on the PedsQL social subscale.

Table IV.

Regressions of Regard Racial Identity as Moderator in Pain and Quality of Life Relation

| Variables | β | R2 | R2 change | F change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV: PedsQL total quality of life | ||||

| Step 1 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 5.37** | |

| Site | −0.25* | |||

| Gender | −0.17† | |||

| Disease severity | 0.01 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 14.12*** | |

| Overall pain | −0.44*** | |||

| Regard | 0.12 | |||

| Step 3 | 0.35 | 0.004 | 0.53 | |

| Overall pain × regard | −0.06 | |||

| DV: PedsQL physical quality of life | ||||

| Step 1 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 6.45*** | |

| Site | −0.22* | |||

| Gender | −0.18* | |||

| Disease Severity | −0.08 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 10.20*** | |

| Overall pain | −0.39*** | |||

| Regard | 0.10 | |||

| Step 3 | 0.34 | 0.02 | 3.32† | |

| Overall pain × regard | −0.16† | |||

| DV: PedsQL emotional quality of life | ||||

| Step 1 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 3.74* | |

| Site | −0.18† | |||

| Gender | −0.20* | |||

| Disease severity | 0.06 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 8.53*** | |

| Overall pain | −0.37*** | |||

| Regard | 0.11 | |||

| Step 3 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.53 | |

| Overall pain × regard | −0.07 | |||

| DV: PedsQL social quality of life | ||||

| Step 1 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 3.36* | |

| Site | −0.21* | |||

| Gender | −0.05 | |||

| Disease severity | −0.00 | |||

| Child age | 0.29** | |||

| Step 2 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 7.58*** | |

| Overall pain | −0.30** | |||

| Regard | 0.19* | |||

| Step 3 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.19 | |

| Overall pain × regard | 0.04 | |||

| DV: PedsQL school quality of life | ||||

| Step 1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 2.70* | |

| Site | −0.20* | |||

| Gender | −0.07 | |||

| Disease severity | −0.08 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 6.01** | |

| Overall pain | −0.33*** | |||

| Regard | 0.07 | |||

| Step 3 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Overall pain × regard | −0.01 |

Note. †p < 0.10. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

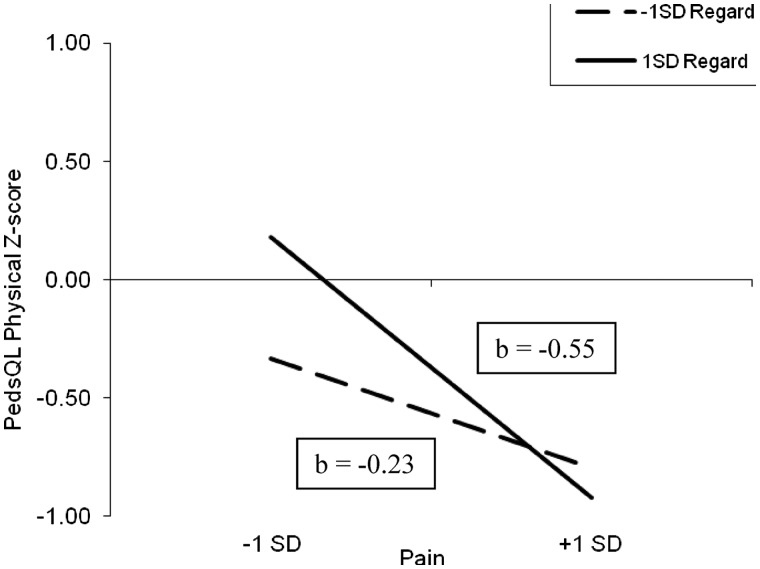

For the PedsQL physical scale, the main effect of overall pain was significant [β = −0.39, t(93) = −4.46, p < 0.001], and the interaction between overall pain and regard was trending toward significance [β = −0.16, t(93) = −1.82, p = 0.07]. Post-hoc probing was conducted to determine the direction of the potential interaction. See Figure 1 for the depiction of the interaction. From the graph, it is apparent that the effects of regard racial identity occur in the context of low pain. Therefore, children with SCD who experience low pain and high regard racial identity tend to have higher QOL compared to children with SCD who experience low pain and low regard racial identity.

Figure 1.

Post-hoc probing of interaction between overall pain and regard racial identity on PedsQL physical score. PedsQL physical as a function of overall pain and regard 1 SD above and 1 SD below the mean in children with SCD.

Discussion

The importance of cultural factors in pediatric chronic illnesses is gaining increased attention (Boergers & Koinis Mitchell, 2010; Lescano et al., 2009; Wilson, 2009). Our hypothesis, that racial identity would moderate the pain and QOL relation, was partially supported. Specifically, children with SCD reporting low pain and high regard racial identity reported higher physical QOL compared to children with low pain and low regard racial identity. However, these results were trending towards significance. For children with SCD, these preliminary results indicate that racial identity may act as a protective factor and influence QOL, but more research in this area is needed.

However, the possible protective effect of racial identity was not found with every dimension of QOL. Thus, racial identity may only impact physical QOL, whereas it may not function in this way with other domains of functioning. Beyond the moderation analyses, the main effects of regard racial identity on QOL are important to consider. Positive regard racial identity was predictive of higher social QOL. This suggests that racial identity may help children with SCD function better in social situations. Yet, these results are correlational in nature and causal conclusions cannot be drawn. Future research examining regard racial identity, including private and public aspects of regard, and other cultural factors in pediatric SCD are needed to confirm these findings and identify other cultural factors that may be associated with functioning and play a protective role in children with SCD.

Consistent with previous research in children and adults with SCD (Anie et al., 2002; Fuggle et al., 1996; Palermo et al., 2002; Panepinto, O’Mahar, DeBaun, Loberiza, & Scott, 2005), pain was a significant predictor of all dimensions of QOL, where high pain was associated with lower QOL. The link between pain and QOL can be explained in numerous ways. It is likely that pain associated with SCD influences various areas of QOL. For example, acute pain episodes are associated with significant physical symptoms that have been found to interfere with school attendance and interactions with peers (Gil et al., 2000; Shapiro et al., 1995), which may lead to decreased QOL in the physical, social, and/or academic domains. Pain experiences may also lead to children with SCD viewing their everyday functioning more negatively, thus impacting their self-reported QOL. However, due to the correlational nature of this study, causality cannot be determined, and other explanations must be considered. It could be that children with lower QOL who experience pain may suffer additional negative impacts on their daily functioning, which thus negatively impacts QOL. Lower QOL in children with SCD may lead to negative perceptions about painful experiences, which may lead to higher pain ratings. This study found that pain and QOL are associated; however, the mechanisms through which this occurs are unclear, and further research is warranted.

Despite the contributions of this study, caveats should be taken into account when interpreting results. The generalizability of the findings from this study is limited. Children in this study were attending a routine SCD-related medical visit; thus, these findings likely do not apply to children attending nonroutine medical visits or those experiencing acute pain crises. However, it is possible different results may have been found if different measures of pain (e.g., intensity ratings and number of SCD pain crises) were utilized. Our sample was also mostly middle class so results may not generalize to children of different socioeconomic backgrounds. The results of this study are correlational in nature, and causal relations cannot be determined between the constructs of interest. For example, it may be that low QOL leads to higher pain perceptions in children with SCD. In addition, it is possible that there may be an unaccounted variable (e.g., response bias, method variance, etc.) that may be influencing the findings. Given that parents are responsible for most medical decisions and management, it is clinically important to include their report in pediatric research as it could increase our understanding of parent perceptions of the impact of the disease. In addition, our use of nurses to rate disease severity may have been biased by nurses using different criteria to assess disease severity.

Research focusing on cultural and other psychosocial variables that may buffer the impact of SCD pain on children’s functioning, such as other dimensions of the MMRI model like racial centrality, is important, as it could lead to the development of culturally appropriate and acceptable interventions to improve QOL in children living with SCD. Whaley & McQueen (2010) found that utilizing an Afrocentric intervention with children 11–18 years of age led to changes in their racial identity. This intervention focused on cultural knowledge and identity development, building community relationships, acquiring self-control and social skills, and emphasized academic performance. Including aspects of interventions that promote positive views (i.e., regard) of African Americans and a sense of belonging in that ethnic group could lead to improvements in racial identity and QOL, but this would important to evaluate in future research.

Examining additional moderation and mediation models of racial identity would also be valuable for future pediatric SCD research and intervention development, as well as investigating mechanisms through which racial identity may impact perceptions of pain and QOL. For example, it is possible that a negative view about one’s race may be associated with problematic cognitions about one’s self and illness, which could lead to inadequate pain coping and negatively impact QOL. In addition, given that experiences of discrimination impact health perceptions in adults (Brondolo et al., 2011), exploring how these experiences may impact the health of African American children with SCD are important lines of inquiry. Future studies focusing on children with SCD should continue to conduct culturally sensitive research and include cultural factors in study designs (Boergers & Koinis Mitchell, 2010; Clay et al., 2002; Kaslow et al., 2000; Lescano et al., 2009; Wilson, 2009).

The impact of the family in the expression of pain, QOL, and racial identity should be considered in pediatric SCD. Families are the primary source through which children learn about pain and race (Craig & Riddell, 2003; Neblett et al., 2008), which may impact their experience and expression of pain (Beyer & Knott, 1998), views of chronic illness (Gurung, 2006), and possibly disease-related health behaviors (e.g., adherence). Another interesting sociocultural consideration is poverty and related stressors and how they may impact the functioning of children with SCD and their families. Family income was not found to be associated with the main variables in this study; however, families who participated were mostly middle class. A more thorough examination of poverty and socioeconomic stressors would be warranted in this population, especially given previous findings that financial difficulties may impact children’s adjustment to SCD (Barbarin et al., 1999). In conclusion, preliminary findings suggest that racial identity might be important to consider when examining pain and QOL in African American children with SCD. Although additional work is necessary to support these novel findings, it is possible that improving racial identity in African American children may result in improvements in physical and social dimensions of QOL.

Funding

The NHLBI of the NIH through a predoctoral NRSA fellowship to (grant number F31HL091728 to C.S.L.).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Acknowledgments

This study is based on the dissertation by Crystal S. Lim, Ph.D., supervised by Dr. Lindsey Cohen and submitted in partial fulfillment of a Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology at Georgia State University. We would like to thank all the families who participated in this study, as well as the medical team at the outpatient clinics. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI or the NIH.

References

- Aiken L S, West S G. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Anie K A, Steptoe A, Bevan D H. Sickle cell disease: Pain, coping and quality of life in a study of adults in the UK. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2002;7:331–344. doi: 10.1348/135910702760213715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballas, S. K. (1998). Sickle cell pain: Progress in pain research and management. Vol. 11 Seattle, WA IASP Press.

- Barakat L P, Lash L A, Lutz M J, Nicolaou D C. Psychosocial adaptation of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. In: Brown R T, editor. Comprehensive handbook of childhood cancer and sickle cell disease: A biopsychosocial approach. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 471–495. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat L P, Patterson C A, Daniel L C, Dampier C. Quality of life among adolescents with sickle cell disease: Mediation of pain by internalizing symptoms and parenting stress. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2008;6:60–68. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarin O A. Do parental coping, involvement, religiosity, and racial identity mediate children’s psychological adjustment to sickle cell disease? Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25:391–426. [Google Scholar]

- Barbarin O A, Christian M. The social and cultural context of coping with sickle cell disease: I. A review of biomedical and psychosocial issues. Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25:277–293. [Google Scholar]

- Barbarin O A, Whitten C F, Bond S, Conner-Warren R. The social and cultural context of coping with sickle cell disease: II. The role of financial hardship in adjustment to sickle cell disease. Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25:294–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bediako S M, Lavender A R, Yasin Z. Racial centrality and health care use among African American adults with sickle cell disease. Journal of Black Psychology. 2007;33:422–438. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer J E, Knott C B. Construct validity estimation for the African-American and Hispanic versions of the Oucher Scale. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1998;13:20–31. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(98)80065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boergers J, Koinis Mitchell D. Sleep and culture in children with medical conditions. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35:915–926. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Hausmann L R, Jhalani J, Pencille M, Atencio-Bacayon J, Kumar A, Kwok J, Ullah J, Roth A, Chen D, Crupi R, Schwartz J. Dimensions of perceived racism and self-reported health: Examination of racial/ethnic differences and potential mediators. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;42:14–28. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9265-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau D C, Panepinto J A, Nimmer M, Hoffmann R G. The number of people with sickle-cell disease in the United States: National and state estimates. American Journal of Hematology. 2010;85:77–78. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) 2011. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/symptoms.html.

- Chavez A F, Guido-DiBrito F. Racial and ethnic identity and development. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. 1999;84:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Clay D L, Mordhorst M J, Lehn L. Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: Where is the diversity? Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:325–337. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.4.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L L, Lemanek K, Blount R L, Dahlquist L M, Lim C S, Palermo T M, McKenna K D, Weiss K E. Evidence-based assessment of pediatric pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:939–955. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly M, Wagner J L, Brown R T, Rittle C, Cloues B, Taylor L. Informant discrepancy in perceptions of sickle cell disease severity. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:443–448. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig K D, Riddell R P. Social influences, culture and ethnicity. In: Finley G A, McGrath P J, editors. Pediatric pain: Biological and social context. Seattle: IASP Press; 2003. pp. 159–182. [Google Scholar]

- Dampier C, Ely B, Brodecki D, O’Neal P. Characteristics of pain managed at home in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease by using diary self-reports. The Journal of Pain. 2002;3:461–470. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.128064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiser C, Morse R. Can parents rate their child’s health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Quality of Life Research. 2001;10:347–357. doi: 10.1023/a:1012253723272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe L P, Thorn B, Day M, Shelby G. Race and sex differences in primary appraisals, catastrophizing, and experimental pain outcomes. The Journal of Pain. 2011;12:563–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuggle P, Shand P A, Gill J L, Davies S C. Pain, quality of life, and coping in sickle cell disease. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1996;75:199–203. doi: 10.1136/adc.75.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil K M, Porter L, Ready J, Workman E, Sedway J, Anthony K K. Pain in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease: An analysis of daily pain diaries. Children’s Health Care. 2000;29:225–241. [Google Scholar]

- Graumlich S E, Powers S W, Byars K C, Schwarber L A, Mitchell M J, Kalinyak K A. Multidimensional assessment of pain in pediatric sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2001;26:203–214. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.4.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung R A. Health psychology: A cultural approach. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G N. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and meditational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow N J, Collins M H, Rashid F L, Baskin M L, Griffith J R, Hollins L, Eckman J E. The efficacy of a pilot family psychoeducational intervention for pediatric sickle cell disease. Families, Systems & Health. 2000;18:381–404. [Google Scholar]

- Lasch K E. Culture, pain, and culturally sensitive pain care. Pain Management Nursing. 2000;1:16–22. doi: 10.1053/jpmn.2000.9761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemanek K L, Ranalli M. Sickle cell disease. In: Roberts M C, Steele R G, editors. Handbook of Pediatric Psychology. 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Lescano C M, Brown L K, Raffaelli M, Lima L. Cultural factors and family based HIV prevention intervention for Latino youth. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:1041–1052. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan C B, Schatz J, Sanchez C, Roberts C W. Validity of the pediatric quality of life inventory for youth with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:1153–1162. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers T A. Goodbye, listwise deletion: Presenting hot deck imputation as an easy and effective tool for handling missing data. Communication Methods and Measures. 2011;5:297–310. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett E W, White R L, Ford K R, Philip C L, Nguyen H X, Sellers R M. Patterns of racial socialization and psychological adjustment: Can parental communications about race reduce the impact of racial discrimination? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18:477–515. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T M, Long A C, Lewandowski A S, Drotar D, Quittner A L, Walker L S. Evidence based assessment of health-related quality of life and functional impairment in pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:983–996. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T M, Riley C A, Mitchell B A. Daily functioning and quality of life in children with sickle cell disease pain: Relationship with family and neighborhood socioeconomic distress. Journal of Pain. 2008;9:833–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T M, Schwartz L, Drotar D, McGowan K. Parental report of health related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;25:269–283. doi: 10.1023/a:1015332828213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panepinto J A, O’Mahar K M, DeBaun M R, Loberiza F R, Scott J P. Health related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: Child and parent perception. British Journal of Haematology. 2005;130:437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quittner A L. Measurement of quality of life in cystic fibrosis. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 1998;4:326–331. doi: 10.1097/00063198-199811000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schecter N L. The management of pain in sickle cell disease. In: McGrath P J, Finley G A, editors. Chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Vol. 13. Seattle: IASP Press; 1999. pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Scottham K M, Sellers R M, Nguyen H X. A measure of racial identity in African American adolescents: The development of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity Teen. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:297–306. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R M, Rowley S A J, Chavous T M, Shelton J N, Smith M A. Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:805–815. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R M, Smith M A, Shelton J N, Rowley S A J, Chavous T M. Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro B S, Dinges D F, Orne E C, Bauer N, Reilly L B, Whitehouse W G, Ohene-Frempong K, Orne M. Home management of sickle cell-related pain in children and adolescents: Natural history and impact on school attendance. Pain. 1995;61:139–144. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00164-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni J W, Seid M, Kurtin P S. PedsQL™ 4.0: Reliability and validity of the pediatric quality of life inventory™ version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Medical Care. 2001;39:800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni J, Thompson K, Hanson V. The Varni/Thompson Pediatric Pain Questionnaire: I. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pain. 1987;28:27–38. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walco G, Dampier C. Chronic pain in adolescent patients. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1990;12:215–225. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/12.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley A L, McQueen J P. Evaluating cohort and intervention effects on black adolescents' ethnic-racial identity: A cognitive-cultural approach. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2010;33:436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D K. New perspectives on health disparities and obesity interventions in youth. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:231–244. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Seaton E, Sellers R. African American racial identity across the lifespan: Identity status, identity content, and depressive symptoms. Child Development. 2006;77:1504–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]