Abstract

We have studied the oncolytic efficacy of two adenovirus vectors named KD3 and INGN 007, which differ from each other only in that whereas KD3 has two small deletions in its e1a gene that restrict its replication to rapidly cycling cells, INGN 007 has wild-type e1a gene. Both vectors overexpress the adenovirus death protein (ADP). Both KD3 and INGN 007 effectively suppressed the growth of subcutaneous human A549 and Hep3B tumors in nude mice upon intratumoral injection, and contained the growth of subcutaneous LNCaP tumors after intravenous injection, making some tumors shrink or disappear. However, in a more demanding model, intravenous injections of neither KD3 nor wild-type Ad5 were effective against subcutaneous A549 tumors, whereas INGN 007 increased the mean survival time by 35%. INGN 007 was also effective in suppressing tumor growth in a challenging A549 orthotopic lung cancer model. INGN 007 was superior to dl1520 (ONYX-015) in repressing subcutaneous A549 tumors. Our results suggest that vectors such as INGN 007 might provide better antitumor efficacy in the clinic as well.

Keywords: tumor, virus, replicating, virotherapy

Introduction

Replication-competent (oncolytic) adenovirus (Ad) vectors have been developed as a promising new tool in the fight against cancer.1 The principal idea behind this approach is that the vector replicates in the cancer cell, lyses the infected cell at the culmination of infection and releases progeny virus. These newly made virions in turn infect neighboring cells in the tumor, and start a new lytic cycle. In theory, such vectors should spread through and eliminate a tumor. Most oncolytic Ads constructed so far are derivatives of human wild-type serotype 5 (Ad5), a virus that causes mild respiratory illness in infants and no disease in immunocompetent adults. Ad5 is one of the best-studied viruses, is genetically stable, does not integrate into the host genome and can be produced in large amounts.

Researchers have introduced various genetic modifications to restrict Ad vector virus replication to cancerous cells. These modifications exploit genetic differences between normal and cancerous cells, for example, place essential viral genes under the control of promoters that are active only in tumor cells, delete viral genes that regulate pro-apoptotic cellular functions known to be active only in normal cells, disable the vector’s capacity to drive the infected cell into the S-phase of the cell cycle, and so on.

Oncolytic Ad vectors carrying such mutations (for example, ONYX-015 [dl1520],2 Ad5-CD/Tkrep,3 CG70604 and CG78705) have been tested in human clinical trials.6 All four vectors caused little toxicity, even when administered intravenously (i.v.) at dose levels of 1 × 1013 virus particles. However, their efficacy as single agents was limited; they produced better results when used in combination with chemotherapy.7 ONYX-015 was the most extensively studied vector among the four with numerous phase I and phase II clinical studies, but it did not proceed through phase III clinical trials in the United States. However, the development of a very similar vector (named H101) occurred in China, and H101 has been approved as an anticancer drug in that country.8

It is clear from these clinical experiments and others performed in animal models that the high anticancer efficacy seen in tissue culture with oncolytic Ads does not readily manifest in vivo. We believe that part of the reason for this is that in many cases the genetic modifications introduced to restrict virus replication to cancer cells attenuate the vector. Ad proteins routinely perform multiple functions; thus, the deletion of a gene in order to abolish one function (for example, downregulation of apoptosis in the case of deletion of the gene for the E1B-55K protein in ONYX-015) will have consequences on other viral functions (for example, Ad late mRNA export from the nucleus). In the case of promoter-substituted vectors, the cellular promoters may not be as efficient as the viral promoters that they have replaced. In addition, it may be impractical to produce the very-high-titer virus stocks required for administering high doses, especially as some of these vectors are impaired for growth.

To circumvent the vector attenuation problem, we have developed INGN 007 (a.k.a. VRX-007),9 a fully replication-competent Ad vector. INGN 007 is not impaired for replication and relies on the natural tropism of Ads for cancerous cells for tumor targeting. Ads utilize the DNA replication machinery of the infected cell for their replication, and for this and probably other reasons, cells with a deregulated cell cycle (such as cancer cells) are more permissive for Ad replication than quiescent cells (most cells in an adult human).10–12 INGN 007 spreads from cell to cell faster than wild-type Ad5 due to the overexpression of the E3-11.6K adenovirus death protein (ADP).9 Overexpression of ADP also increases the spread of Ad vectors in vivo.13 As it has been shown that vector dissemination within the tumor is crucial for efficacy,14 we believe that ADP overexpression further enhances the anticancer efficacy of INGN 007 and other anticancer Ad vectors.9,13,15,16 Recently, we have reported on the large-scale biodistribution and safety studies conducted with INGN 007 in two rodent species, the permissive Syrian hamster and the poorly permissive mouse.17,18 From these studies, we established that the safety profile of INGN 007 is similar to that of Ad5 in hamsters and that of Ad5 and a replication-defective Ad vector in mice. All the three vectors/viruses were distributed to most organs after i.v. injection. Both INGN 007 and Ad5 replicated in the lungs, livers and possibly kidneys of hamsters but not mice. As expected, the primary target organ for toxicity was the liver in both species, as evidenced by transient elevation of serum transaminase levels and by histopathological changes in the liver. A no observable adverse effect level of 3 × 1010 virus particles per kg was established for INGN 007 in hamsters. Based on pre-clinical data with INGN 007, the Food and Drug Administration approved a phase I clinical trial to test the safety of the vector.

In this study, we present data showing that INGN 007 is efficacious in repressing the growth of various tumors in animal models. We propose that INGN 007 and vectors such as INGN 007 can be used safely and effectively to treat cancer patients using intratumoral injection.

Materials and methods

Cells and viruses

MeWo melanoma and SQ-20B and HLaC head-and-neck cancer cells were received from Introgen Therapeutics Inc. (Houston, TX). A549 lung cancer, Hep3B hepato-cellular carcinoma and LNCaP prostate cancer cells were obtained from ATCC (Bethesda, MD). All these cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS) containing 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under 5% CO2 pressure. Normal human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs) were purchased from Clonetics (San Diego, CA), and were cultured in mammary epithelial growth medium (Clonetics).

The construction of INGN 0079 and KD315 was described earlier. Briefly, KD3 is a deletion mutant of Ad5; it carries two small deletions in the e1a gene that preclude the binding of E1A protein to the Rb-family proteins and p300/CBP. Further, KD3 has all genes in the E3 region deleted, except for the 12.5K and adp genes. With KD3, the adp gene is reinserted such that the ADP protein is vastly overexpressed compared with wild-type Ad5. INGN 007 is identical to KD3, except that it has the wild-type e1a gene. The Ad5 mutant dl1520,19 which is the same virus as ONYX-015, was obtained from Dr Arnie Berk (University of California at Los Angeles). dl1520 has the gene for E1B-55K deleted. It also has the genes for the E3 RIDα, RIDβ and 14.7K proteins deleted, and has a small deletion in the gene for the E3-6.7K protein.

The vectors were propagated on suspension KB cells, purified by isopycnic equilibrium centrifugation and plaque titered on A549 cells.20

Cell viability assay

For the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay for cell lysis, MeWo, SQ-20B, HLaC and HMEC cells grown in 35 mm tissue culture dishes were infected at 1 plaque-forming unit (PFU) per cell in 1 ml of serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. After an adsorption period of 1 h, 1 ml of complete medium was added (final fetal bovine serum concentration of 5%). HMEC cells were infected in mammary epithelial growth medium or mammary epithelial basal medium. To make HMEC cells quiescent, they were grown to about 50% confluency in mammary epithelial growth medium, and then the medium was changed to human mammary epithelia basal medium without growth factors. With this method, the cell-doubling rate was decreased by 40%. Infected cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. At 8 (MeWo, SQ-20B and HLaC) or 7 (HMEC) days post-infection (p.i.), supernatants were collected and microcentrifuged to remove floating cells. Total lysis samples were prepared by the addition of lysis buffer included in the Cyto Tox 96 kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Samples of volume 20 µl were assayed in triplicate using the LDH assay kit Cyto Tox 96 and read on an EL340 microplate reader (BioTec Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT) at 490 nm.

Animal experiments

Five- to six-week-old female athymic nude mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague–Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). All experiments were carried out according to the animal protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Saint Louis University. Tumor measurements were carried out with Sylvac (Crissier, Switzerland) digital calipers linked to the in-house developed Mouser Tumor Measurement and Analysis software. Tumor volumes were calculated according to the formula length × width × width/2.

Subcutaneous tumors were generated by injecting 1 × 107 A549, Hep3B or LNCaP cells in serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10–50% Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). When the tumors reached about 100 µl (300 µl for Hep3B) in size, the animals were injected either intratumorally or i.v. (into the tail vein) with 100 µl of vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline with 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM CaCl2) or vehicle containing virus vectors. For most experiments (except the LNCaP i.v. experiment with KD3), the doses were fractionated and given on three consecutive days.

The orthotopic lung tumor model was described earlier.21 Briefly, mice were injected with 2 × 106 A549 cells i.v. (tail vein). At 10 days post-injection, the animals were injected i.v. (jugular vein) with vehicle or vehicle containing various doses of INGN 007 for three consecutive days. At 21 days after the injection of cells, the animals were killed and the tumor nodules in the lungs were visualized using India ink.

The experiment to test the antiviral effect of CMX001 (hexadecyoxypropyl-cidofovir) against INGN 007 was performed in Syrian hamsters purchased from Harlan Sprague–Dawley as described previously.22 CMX001 was obtained from Chimerix Inc. (Durham, NC). The animals were immunosuppressed with twice-weekly intraperitoneal injections of 100 mg per kg of cyclophosphamide following a single dose of 140 mg per kg of the drug, and injected i.v. with 3 × 1010 PFU of INGN 007, which is the lethal dose 50% of the virus in immunosuppressed hamsters. One group of animals was left untreated, and the other was treated with six daily doses of 2.5 mg per kg of CMX001 through oral gavage, starting a day before the injection of the vector. The animals were observed daily, and were killed when they became moribund.

Determining the infectious vector load of tumors

The infectious vector content of tumors was determined as described previously.23 Briefly, at the completion of the experiment, the tumors were excised, weighed and homogenized. The homogenized extract was titered in a 50% tissue culture infective dose assay.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software package. Levene’s test was used to test for homogeneity of data, analysis of variance to assay for overall effect and Student’s t-test for pairwise comparisons. Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank statistics were utilized to assess statistical significance in survival assays. In all analyses, P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

INGN 007 lyses cancer cells more effectively than wild-type Ad5

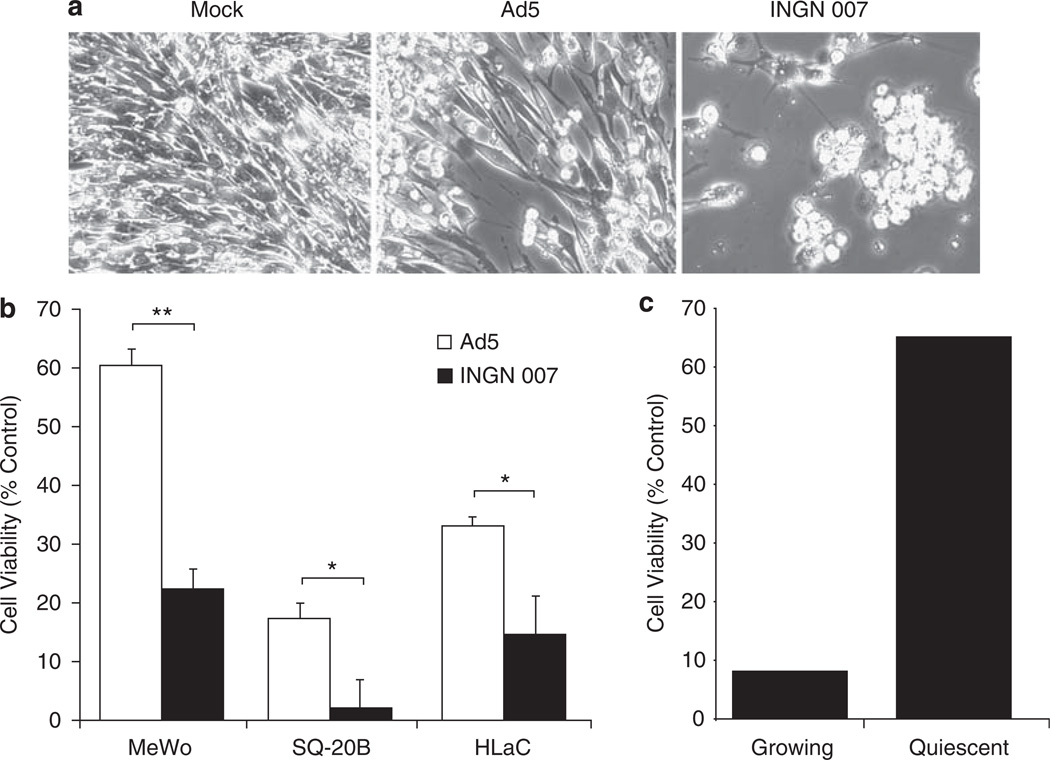

The overexpression of ADP is expected to raise the potency of INGN 007 to destroy cancer cells as compared with Ads expressing normal levels of ADP or no ADP at all This has been established earlier with lung and liver cancer cell lines;9 to expand these studies, we determined the ability of INGN 007 to lyse three cancer cell lines of various origins. MeWo melanoma and SQ-20B and HLaC head-and-neck cancer cells were mock infected or infected with 1PFU of Ad5 or INGN 007. At 8 days p.i., INGN 007-infected MeWo cells exhibited more cytopathic effect than Ad5-infected cells (Figure 1a). Further, at 8 days p.i., the viability of INGN 007-infected MeWo, SQ-20B and HLaC cells was significantly lower than that of cells infected with Ad5, as determined by an LDH release assay (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

INGN 007 lyses cancer cells more effectively than Ad5. (a) MeWo human melanoma cells were mock infected or infected with Ad5 or INGN 007 at 1PFU per cell. The cells were photographed at day 8 p.i. (b) The indicated cell lines were infected with 1PFU per cell of INGN 007 or Ad5. At day 8 p.i., the cell lysis was quantified by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in the medium. Data are presented as percent of total lysis of mock-infected cells. (c) INGN 007 replicates less well in normal cells than in cancer cells and less well in quiescent cells than in proliferating cells. Growing and quiescent human mammary epithelial cells were mock infected or infected with 1PFU per cell of INGN 007. At day 7 p.i., cell lysis was quantified by measuring LDH levels in the medium. Cell viability as percent of corresponding mock-infected cells is presented. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Statistically significant differences were determined by unpaired Student’s t-test; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.001.

INGN 007 lyses many different cancer cell lines

INGN 007 effectively lysed a number of cancer cell lines, irrespective of their origin and genetic makeup (Table 1). Nearly all cell lines examined were efficiently lysed by INGN 007, indicating that INGN 007 has a broad host range of cancer cells. However, as the structural proteins of INGN 007 are all derived from Ad5, the vector cannot infect CAR-negative cells efficiently in tissue culture (at 1PFU per cell), as illustrated by its inability to lyse SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells.

Table 1.

Effectiveness of INGN 007 in various cancer cell lines

| Cancer type | Cell line (rate of cell lysis)a |

|---|---|

| NSCLC/lung, human | A549 (+++), H441 (+++) |

| HCC, human | Hep3B (++), HepG2 (+++) |

| Cervical, human | HeLa (++), C-33A (++) |

| Prostate, human | DU145 (++), PC-3 (+++), LNCap (+++) |

| Colon, human | HT29 (++), LS513 (+++), SW480 (+) |

| Breast, human | MCF7 (+) |

| Vulval, human | A431 (++) |

| Head and neck, human | JSQ-3 (++), HLaC (++), SQ20B (++) |

| Melanoma, human | MeWo (++) |

| Ovarian carcinoma, human | SKOV3 (−) |

| Kidney, Syrian hamster | HaK (++) |

| Sarcoma, Syrian hamster | DDT1 MF2 (ductus deferens leiomyosarcoma (+)) |

| Pancreatic, Syrian hamster | PC1 (+) |

| Sarcoma, cotton rat | LCRT (mammary sarcoma) (+) |

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung carcinoma.

The rate of cell lysis was determined by various methods; in some experiments membrane integrity was measured, in others indirect immunofluorescence and yet in others the vector spread assay was used. +++, very rapid lysis; ++, rapid lysis; +, lysis; −, no lysis.

INGN 007 replicates preferentially in cancer cells

Ads need a conducive cellular environment for successful replication, that is, an abundance of enzymes and precursor substances for macromolecular synthesis, and a relative lack of antiviral defense mechanisms. These conditions are readily found in cancer cells but not in most normal cells in an adult human. We have shown previously that INGN 007 replicates 100-fold better in A549 human lung cancer cells than in primary normal human bronchial epithelial cells.21 The normal cells in that experiment were actively dividing; this is not the case with most terminally differentiated normal cells, which form the bulk of cells in the adult human body. To test whether quiescent conditions further decrease the ability of INGN 007 to kill normal cells, we compared the cytopathic effect induced by the vector upon infection of growing and growth-arrested HMECs by measuring LDH release. At 7 days p.i., 65% of the quiescent INGN 007-infected HMEC cells were still viable, as opposed to only 8% of the rapidly dividing HMEC cells (Figure 1c).

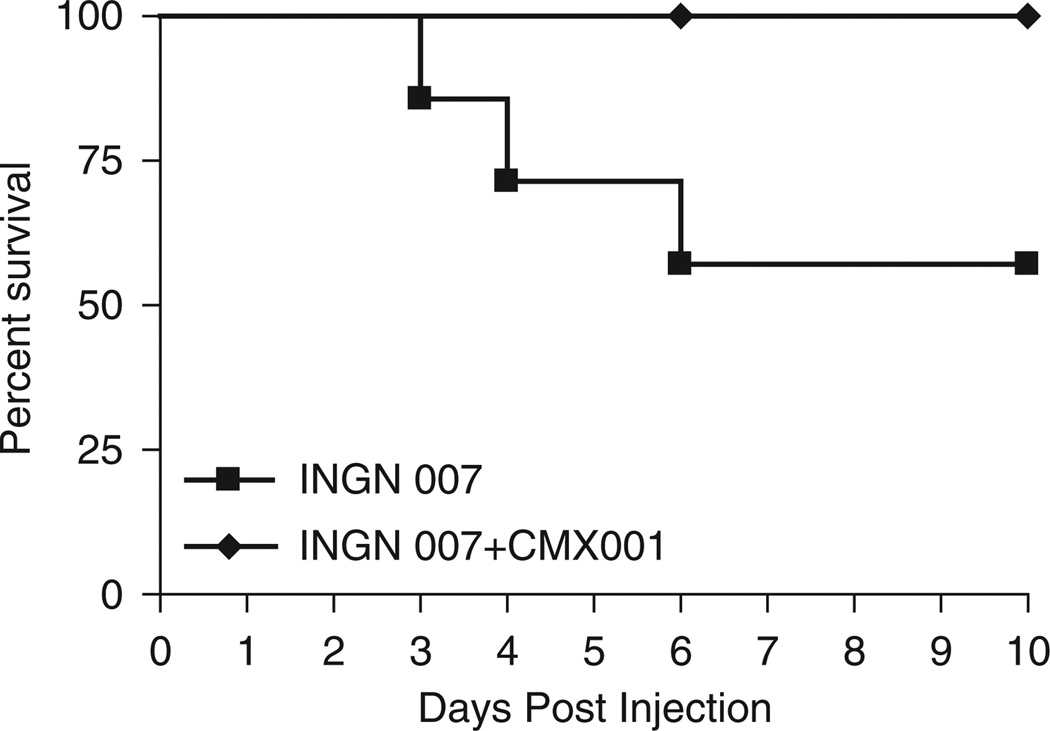

CMX001 rescues immunosuppressed Syrian hamsters from a lethal challenge with INGN 007

We have demonstrated previously that the safety profile of INGN 007 is similar to that of wild-type Ad5.17 Ad5 infections are usually asymptomatic in healthy adults, but the virus can cause severe disseminated infection in immunosuppressed patients. To emulate this situation, we have developed an animal model based on the Syrian hamster, which is permissive for species C human Ads.24–27 Immunosuppressed hamsters can be used to test the efficacy of antiviral drugs.22 We tested the ability of an antiviral drug named CMX001 to prevent virus replication-associated toxicity in a hypothetical worst-case scenario, in which an extreme dose of INGN 007 has been introduced into the blood stream. CMX001 is a chain-terminator-type nucleoside analog that is linked to a lipid moiety for better bioavailability; it inhibits the replication of Ads.22,28 Immunosuppressed hamsters were injected i.v. with 3 × 1010 PFU of INGN 007. One group of animals was treated with daily doses of 2.5 mg per kg of CMX001 for seven consecutive days starting a day before vector injection, and the other group was left untreated. All of the eight treated hamsters completely recovered by the conclusion of the experiment, whereas three of the seven untreated animals died by 6 days post-injection (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CMX001 protects Syrian hamsters from lethal challenge with INGN 007. The lethal dose 50% (LD50) of INGN 007 was injected intravenously into animals treated or not treated with CMX001. Hamsters were killed when they became moribund. Vehicle n = 7; CMX001 n = 8.

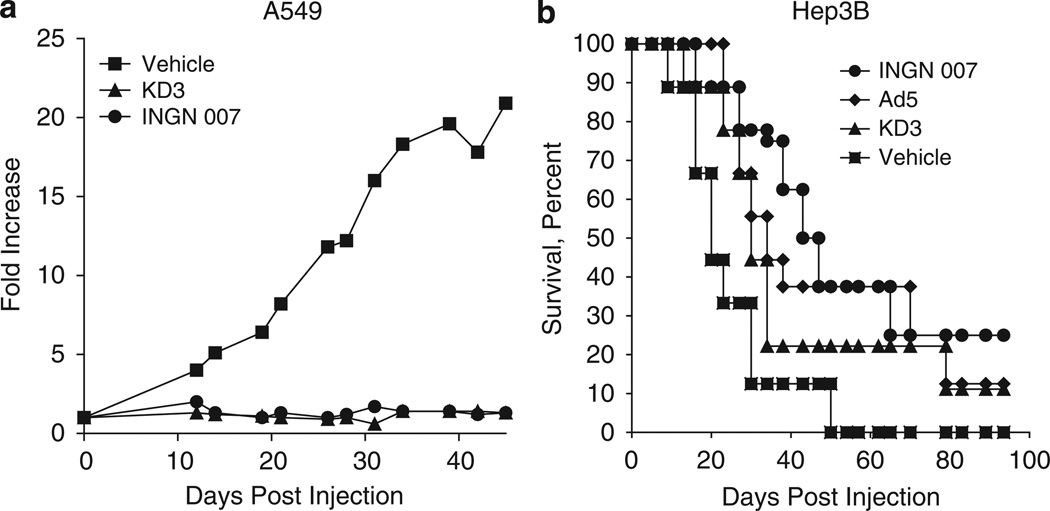

Intratumoral injection of INGN 007 and KD3 suppresses the growth of subcutaneous lung and liver cancer xenografts in nude mice

We have reported earlier that the ADP-overexpressing oncolytic Ad vector named KD3 showed enhanced antitumor effect as compared with an Ad5 mutant (dl1101/1107), which has the same two e1a deletions as does KD3 but does not overexpress ADP.15 The replication of KD3 is restricted to cells with a deregulated cell cycle owing to the two short deletions in the e1a gene; in every other respect it is identical to INGN 007. The anticancer efficacy of INGN 007 upon intratumoral injection into subcutaneous human tumor xenografts in nude mice was compared with that of KD3. In two separate experiments, A549 human lung cancer cells or Hep3B human hepatocellular cancer cells were used to form subcutaneous tumors in nude mice. When the tumors reached about 100 µl (A549) or 300 µl (Hep3B) in size, they were injected intratumorally with vehicle, KD3 or INGN 007. Both vectors significantly suppressed the growth of A549 tumors (Figure 3a). The vehicle-injected tumors grew about 20-fold, whereas tumors injected with either Ad vector remained unchanged. With the animals bearing Hep3B tumors, INGN 007 extended the mean survival time to 58 days versus 20 days with vehicle, 43 days with Ad5 and 40 days with KD3 (all three viruses significantly improved the survival compared with vehicle treatment, but the differences among the viruses were not statistically significant) (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Intratumoral injection of KD3 or INGN 007 suppresses the growth of subcutaneous A549 lung cancer and Hep3B liver tumor xenografts in nude mice. (a) Pre-established subcutaneous A549 tumors were injected intratumorally with three daily doses of vehicle (n = 16) or 3 × 108 PFU of KD3 (n = 17) or INGN 007 (n = 16). Fold increase in tumor size compared with the size at the time of injection is shown. Vehicle versus INGN 007, P = 0.026; vehicle versus KD3, P < 0.001; INGN 007 versus KD3, P = 0.24 (Student’s t-test). (b) Nude mice bearing pre-established subcutaneous Hep3B tumors were injected intratumorally with three daily doses of vehicle (n = 8) or 3 × 108 PFU of INGN 007 (n = 8), KD3 (n = 9) or Ad5 (n = 7). Animals were killed when the tumors reached 1 ml of size. Vehicle versus INGN 007, P = 0.01; vehicle versus KD3, P < 0.06; vehicle versus Ad5, P < 0.04; INGN 007 versus KD3, P = 0.24 (log rank). The differences between the virus-injected groups are not statistically significant.

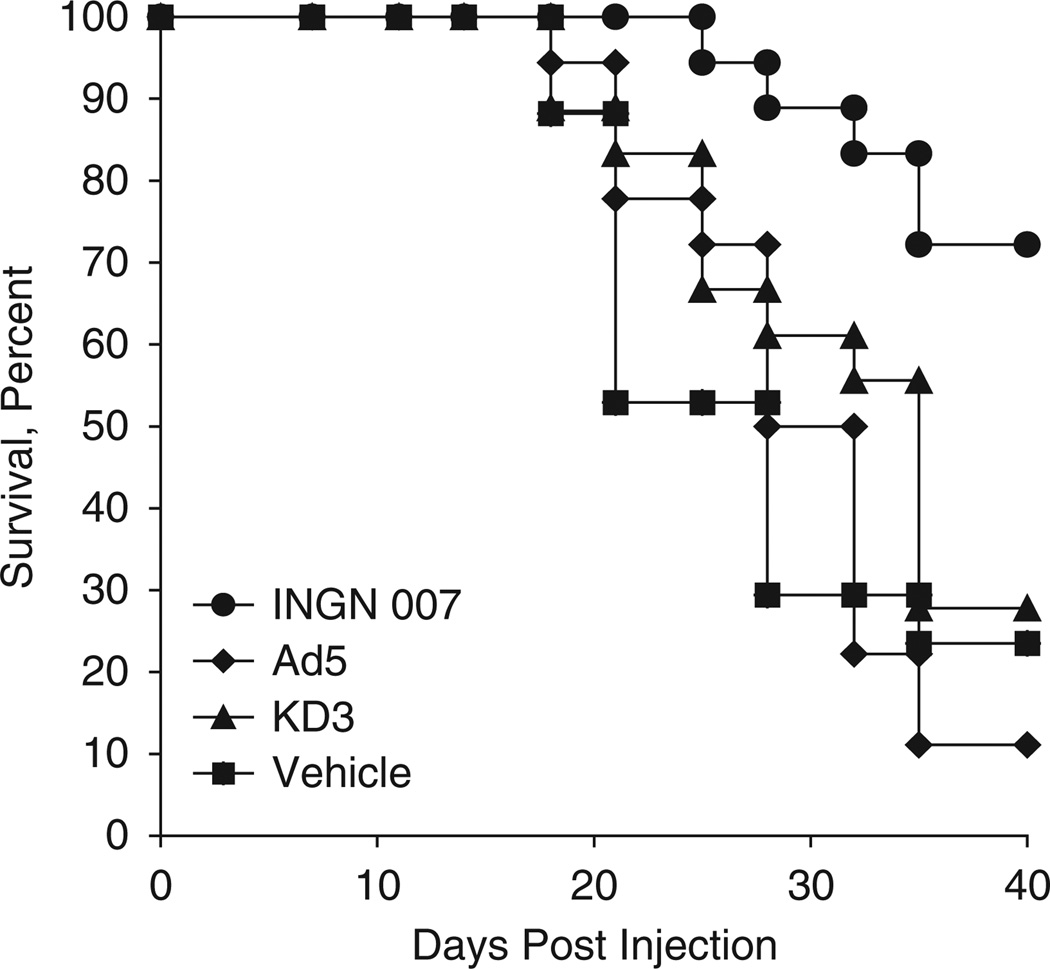

INGN 007 is more efficacious than KD3 or Ad5 against more resilient tumors when injected intravenously

A549 tumors are very compartmentalized, fibrotic and poorly vascularized, which makes the spread of the virus through the tumor more difficult. To test the efficacy of the vectors under more challenging conditions, we tested the antitumor efficacy of INGN 007 and KD3 after systemic administration. First, subcutaneous tumors were generated by injecting A549 cells into the hind flanks of nude mice. The animals were injected i.v. with vehicle or 3 × 108 PFU of INGN 007, KD3 or wild-type Ad5 on three consecutive days (total dose of 9 × 108 PFU). In this more demanding model, the enhanced efficacy of INGN 007 was more apparent. Although INGN 007 prolonged the mean survival time from 28 days (vehicle-treated animals) to 38 days (P = 0.002), neither Ad5 (mean survival: 31 days) nor KD3 (mean survival: 31 days) had a significant effect on survival (P = 0.98 and 0.65, respectively) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Intravenous injection of INGN 007 is more efficacious in extending the lifespan of A549 lung cancer tumor xenograft-bearing mice than intravenous injections of KD3 or Ad5. Mice bearing subcutaneous A549 tumors (n = 18/group) were injected intravenously with vehicle or 3 × 108 PFU of the indicated viruses for three consecutive days. Animals were killed when tumors reached 1 ml size. Vehicle versus INGN 007, P = 0.002; vehicle versus Ad5, P = 0.98; vehicle versus KD3, P = 0.65; INGN 007 versus Ad5, P < 0.001; INGN 007 versus KD3, P = 0.002; Ad5 versus KD3, P = 0.36 (log rank).

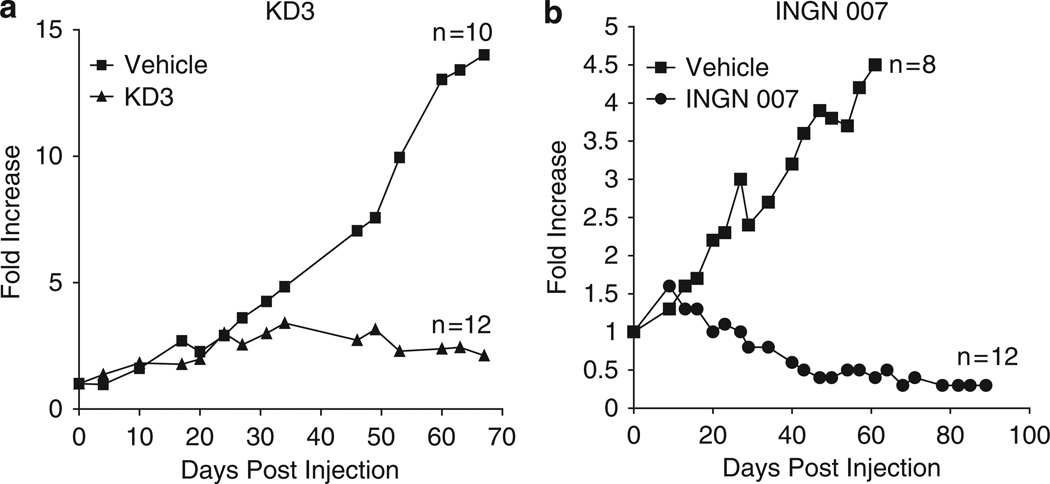

Both KD3 and INGN 007 are efficacious against LNCaP tumors following intravenous injection of the vectors

The purpose of these experiments was not to compare KD3 with INGN 007, but rather to determine how well these vectors could repress subcutaneous LNCaP tumors following i.v. administration. LNCaP tumors are frequently studied by Ad vector research groups.29–31 LNCaP tumors were induced similarly to the A549 tumors described above. When the tumors grew to about 100 µl in size, the mice were injected i.v. with either vehicle or single dose of 2 × 108 PFU of KD3. In a separate but similar experiment, mice bearing LNCaP tumors were injected with 3 × 108 PFU of INGN 007 for three consecutive days. In both experiments, the growth of tumors was followed by measuring them twice weekly. As expected, both KD3 and INGN 007 suppressed the growth of LNCaP tumors very effectively. Over the duration of the study, KD3 decreased the growth of tumors from the 15-fold growth seen with the vehicle-injected tumors to about twofold, and KD3 eliminated three out of 12 tumors (Figure 5a). In the other experiment, INGN 007 cured one-third of the animals and shrunk most tumors by day 91, producing a 70% decrease in overall tumor size (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Intravenous injection of either KD3 or INGN 007 efficiently suppresses the growth of subcutaneous LNCaP prostate cancer xenografts in nude mice. Nude mice bearing pre-established LNCaP tumors received a single injection of vehicle (n = 10) or 2 × 108 PFU of KD3 (n = 12) (a), or three daily doses of vehicle (n = 8) or 3 × 108 PFU (total dose of 9 × 108 PFU) of INGN 007 (n = 12) (b). The mean tumor growth compared with size at the time of injection is shown. Vehicle versus KD3, P = 0.005; vehicle versus INGN 007, P = 0.007 (Student’s t-test).

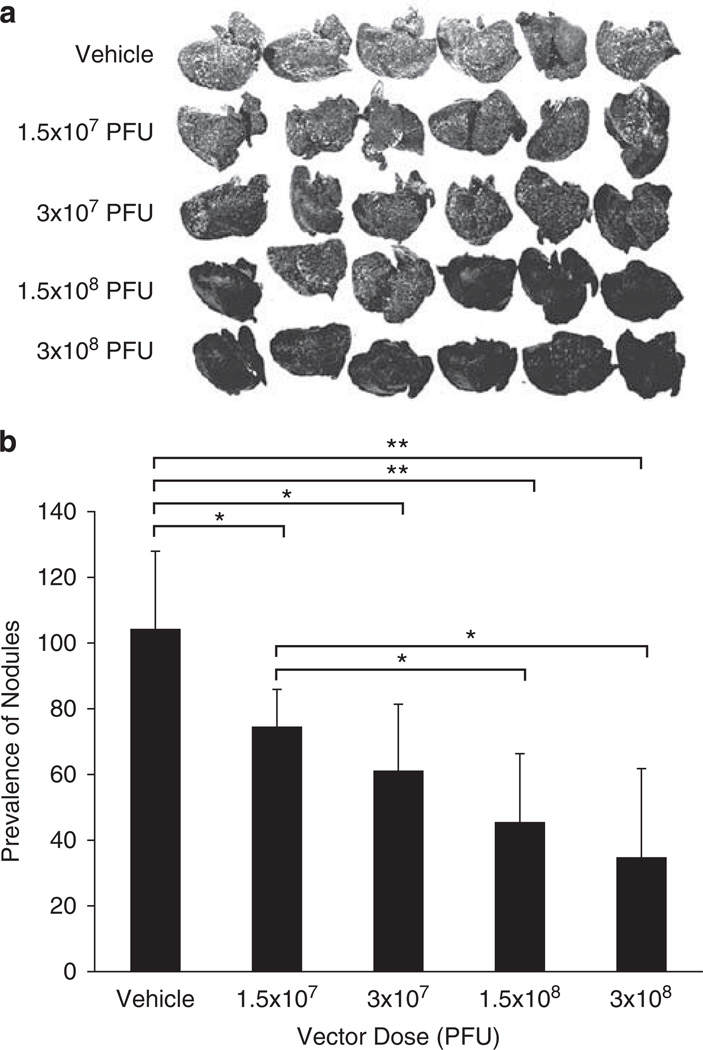

Intravenous injection of INGN 007 reduces the number and size of orthotopic lung tumor nodules in a dose-dependent manner

Next, we examined an even more challenging model using INGN 007, namely an orthotopic lung model of A549 tumors. Orthotopic lung tumors were induced in nude mice by injecting A549 cells i.v. These cells colonized the lung, and with time they gave rise to disseminated tumor nodules. At 10 days after the injection of cells, the mice were injected i.v. with vehicle or with various doses of INGN 007, ranging from 1.5 × 107 to 3 × 108 PFU, fractionated into three daily doses. At day 21 after the injection of the cells, the animals were killed and necropsied. All doses of INGN 007 produced a noticeable reduction in the number and size of lung tumor nodules (Figure 6a) compared with vehicle-injected animals. This difference became even more visible after quantifying the severity of lung lesions; the lungs of animals treated with the high dose of the vector contained 73% fewer tumor nodules than the lungs of the vehicle-treated animals (Figure 6b). Furthermore, an obvious dose effect could be observed among the groups treated with the different doses of INGN 007.

Figure 6.

Intravenous injection of INGN 007 decreases the prevalence of orthotopic A549 lung tumors in nude mice. Athymic nude mice were injected intravenously with 2 × 106 A549 lung cancer cells into the tail vein (day 0). At 10, 11 and 12 days after injection of the cells, the mice were injected via the jugular vein with vehicle (mock) or with the indicated doses of INGN 007. On day 21, the animals were killed and the lungs were stained with India ink. (a) Photographs of the stained lungs show that the tumor nodules appear as white spots on a black background. (b) The photographs for each group were scanned and then analyzed with Adobe Photoshop software. The mean luminosity of all the pixels in the same area of each lung was measured and averaged for each group (n = 6/group). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

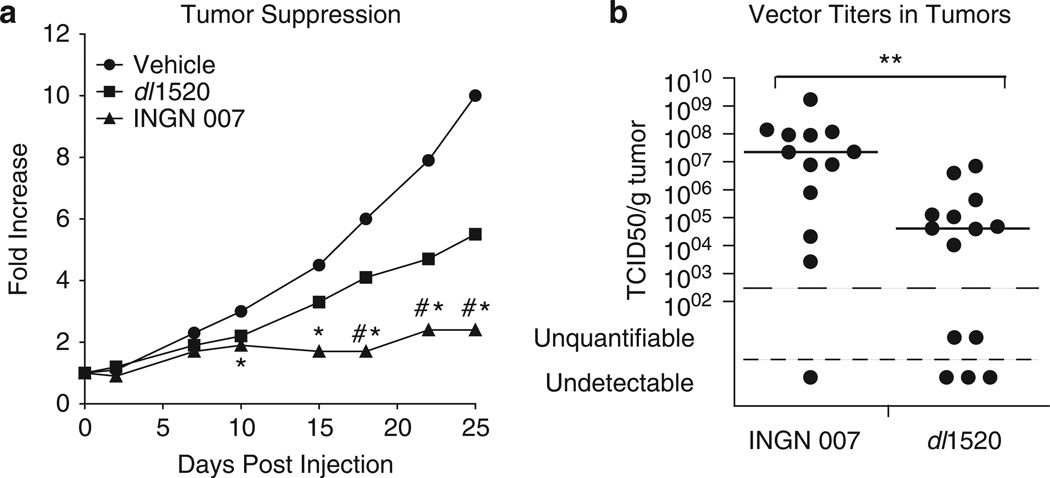

INGN 007 suppresses the growth of subcutaneous human lung tumors in nude mice to a greater extent than dl1520

We compared the efficacy of INGN 007 with that of the well-studied vector dl1520 (ONYX-015). Subcutaneous A549 human lung tumors were injected intratumorally with vehicle or 9 × 108 PFU of INGN 007 or dl1520, fractionated into three daily doses. Up to about 10 days p.i., the two suppressed tumor growth to a similar extent. However, in the second half of the experiment, the tumor suppression by INGN 007 was significantly better than that by dl1520 (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

INGN 007 suppresses the growth of subcutaneous A549 human lung cancer tumors more efficiently and replicates better in tumors than dl1520 (ONYX-015). Subcutaneous A549 tumors in nude mice were injected intratumorally with vehicle or with 3 × 108 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) of the viruses on three consecutive days, starting from day 2. One dl1520- and 3 INGN 007-treated tumors disappeared completely. (a) Median growth of tumors compared with their size at the start of the experiment. Mock and dl1520: n = 16; INGN 007: n = 15. *INGN 007 versus Mock, P < 0.05; #INGN 007 versus dl1520, P < 0.05. (b) Infectious virus titers in tumors at the completion of the experiment (day 25). The horizontal bar represents the median value. **INGN 007 versus dl1520, P < 0.01.

We determined the amount of infectious vector in the tumors at the completion of the experiment (25 days after the injection of vectors). Consistent with the efficacy data, there was approximately 500-fold more live vector in the INGN 007-injected tumors than in dl1520-injected ones (Figure 7b). As non-replicating Ad vectors do not persist in tumors,32 vectors recovered from tumors 25 days after injection are probably the product of virus replication.

Discussion

In the past few years, several oncolytic Ad vectors have been characterized in clinical trials. Although most of these trials were aimed at establishing the safety of the vectors (none of the replication-competent Ad vectors tested so far caused any dose-limiting toxicity), the limited amount of data that was collected indicated that, with few exceptions, their antitumor efficacy was less than that might have been desired. All the oncolytic Ad vectors showed limited efficacy as single agents, which was augmented in some cases by the concomitant use of radiation or chemotherapy.7 All these vectors carried one or more mutations that restricted the replication of the virus to cancerous cells. In our judgment, the attenuation resulting from these genetic changes is one of the causes for the limited antitumor efficacy exhibited in the human clinical trials. As an alternative to the so far tested replication-competent Ad vectors, we have developed INGN 007, a fully replication-competent oncolytic Ad vector. We have shown previously that INGN 007 has a faster replication cycle and is more cytolytic in vitro than wild-type Ad5 owing to overexpression of ADP.9

Another drawback of oncolytic Ad vectors with restricted replication is that often they are effective against only a specific type of cancer, or a subset of cancers, as was the case with KD3 (data not shown). INGN 007 has a broad spectrum; it very effectively lysed a panel of various types of cancer cells, irrespective of their genetic background.

This difference in host range manifests in vivo as well. Both vectors proved very effective in certain tumor models, such as intratumoral injection into subcutaneous A549 or LNCaP tumors. In accord with in vitro data (not shown), there was a marginal difference in efficacy, favoring INGN 007, in Hep3B cells. That KD3 performed as well or nearly as well as INGN 007 in subcutaneous tumors upon intratumoral injection is not surprising, as KD3 is a very potent vector itself.15 However, the advantage of INGN 007 over KD3 became obvious when the vectors were tested head-to-head in a more rigorous model, in which the vectors were administered systemically to treat subcutaneous A549 tumors. In this system, only a fraction of the injected vector dose reaches the target tumors, and those few infecting virus particles have to replicate sufficiently to have an effect on tumor growth. In this system, INGN 007 fared much better than KD3- or Ad5-treated animals (Figure 5). That INGN 007 was more effective in this model than Ad5 is particularly interesting, and might reflect the effect of ADP overexpression.

In an orthotopic disseminated lung tumor model, INGN 007 was effective against more established nodules but not against nodules consisting of a few cells only, inasmuch as it did not reduce the prevalence of tumors when it was applied 3 days after the cells were injected (data not shown). This suggests that an intravascularly administered oncolytic Ad might preferentially act on larger tumors, possibly because the vector gains access to those tumors through the blood supply, and that small, not yet vascularized tumors might escape infection.

INGN 007 replicated better in vivo in subcutaneous lung tumors than did dl1520, the same virus as ONYX-015, a vector that has been extensively tested both in pre-clinical and clinical studies (reviewed in Alemany33 and Kumar et al.34). This better replication resulted in significantly more efficacious tumor suppression. We predict that just as in animals, INGN 007 would perform better than ONYX-015 in cancer patients.

Although INGN 007 does not have an engineered genetic feature to restrict its replication to cancerous cells, it nevertheless replicates much more poorly in normal cells than in cancer cells,21 and its replication is even less efficient in quiescent primary cells. This difference probably reflects the inherent preferential replication of human species C Ads in cancerous cells.11,12 As the vast majority of normal cells in patients are differentiated, quiescent cells, INGN 007 would probably replicate poorly in those. There are certain types of cells, for example, hematopoietic cells and stem cells, that proliferate rapidly. However, species C Ads do not infect these cells well because these cells lack CAR (the Ad5 receptor) and seem to have other features that restrict Ad replication.

About 40–60% of the population has circulating antibodies against Ad5. Although this might hinder systemic administration of Ad5-based vectors, neutralizing antibodies can provide an extra layer of safety to oncolytic Ads. We reported that pre-existing immunity does not significantly alter the oncolytic efficacy of INGN 007,24 but it does alleviate the toxicity of INGN 00725 in the permissive, immunocompetent Syrian hamster model. These data indicate that a vector entering the circulation would be quickly inactivated by neutralizing antibodies in patients with previous exposure to Ad5.

Previously, we have shown that the antiviral drug CMX001 could protect immunosuppressed hamsters from lethal challenge by Ad5.22 As expected, CMX001 was fully effective in stopping INGN 007 replication and limiting toxicity in the same animal model. As this model represents a truly worst-case scenario, that is, i.v. injection of an extreme dose of an oncolytic Ad vector into a drastically immunosuppressed patient, we believe that this drug could be used to prevent viral toxicity in the unlikely event of runaway vector replication.

Based on these results, we suggest that a fully replication-competent oncolytic Ad vector such as INGN 007 could be developed as an anticancer agent. The vector will rely on the natural preference of species C Ads for replication in cancerous cells and in permissive proliferating cells. The potentially stronger side effects would be balanced by higher efficacy at lower doses; thus, such a vector would provide a therapeutic window comparable to or even wider than a tumor-restricted one. Furthermore, unlike many tumor-restricted Ad vectors, Ads with wild-type replication capabilities are easy to produce in high titers needed for clinical applications. Such vectors could be injected intratumorally; this approach limits the dissemination of the virus mostly to the injected locale.26 As Ad5, the parental virus for most replication-competent Ad vectors, does not cause clinically significant illness in immunocompetent adults and is quickly eliminated by the immune system, we expect that a fully replication-competent Ad vector might have similar characteristics in patients. This claim is supported by the fact that INGN 007 has a similar safety profile as Ad5 in hamsters.17,18 Moreover, with INGN 007, the deletion of the immunomodulatory E3 genes35 is expected to further increase safety by exposing the vector-infected cells to the host immune system. Further, there is at least one antiviral drug available that is able to mitigate the toxic effects of resulting from the replication of an oncolytic Ad.

Based on these results, we believe that INGN 007 warrants development as a novel anticancer agent.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Grant CA118022 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Some of the funding for the research was provided by VirRx Inc. WSMW and KT own stock in VirRx Inc.

References

- 1.Cattaneo R, Miest T, Shashkova EV, Barry MA. Reprogrammed viruses as cancer therapeutics: targeted, armed and shielded. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:529–540. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bischoff JR, Kirn DH, Williams A, Heise C, Horn S, Muna M, et al. An adenovirus mutant that replicates selectively in p53-deficient human tumor cells. Science. 1996;274:373–376. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5286.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freytag SO, Rogulski KR, Paielli DL, Gilbert JD, Kim JH. A novel three-pronged approach to kill cancer cells selectively: concomitant viral, double suicide gene, and radiotherapy. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:1323–1333. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.9-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez R, Schuur ER, Lim HY, Henderson GA, Simons JW, Henderson DR. Prostate attenuated replication competent adenovirus (ARCA) CN706: a selective cytotoxic for prostate-specific antigen-positive prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2559–2563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu DC, Chen Y, Seng M, Dilley J, Henderson DR. The addition of adenovirus type 5 region E3 enables calydon virus 787 to eliminate distant prostate tumor xenografts. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4200–4203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lichtenstein DL, Wold WSM. Experimental infections of humans with wild-type adenoviruses and with replication-competent adenovirus vectors: replication, safety, and transmission. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:819–829. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin E, Nemunaitis J. Oncolytic viral therapies. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:643–664. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jia H, Kling J. China offers alternative gateway for experimental drugs. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:117–118. doi: 10.1038/nbt0206-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doronin K, Toth K, Kuppuswamy M, Krajcsi P, Tollefson AE, Wold WSM. Overexpression of the ADP (E3-11.6K) protein increases cell lysis and spread of adenovirus. Virology. 2003;305:378–387. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berk AJ. Recent lessons in gene expression, cell cycle control, and cell biology from adenovirus. Oncogene. 2005;24:7673–7685. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez R, Huang W, Finnen R, Bragg C, Flint SJ. Adenovirus E1B 55-kilodalton protein is required for both regulation of mRNA export and efficient entry into the late phase of infection in normal human fibroblasts. J Virol. 2006;80:964–974. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.964-974.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaillancourt M, Atencio I, Quijano E, Howe JA, Ramachandra M. Inefficient killing of quiescent human epithelial cells by replicating adenoviruses: potential implications for their use as oncolytic agents. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005;12:691–698. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barton KN, Paielli D, Zhang Y, Koul S, Brown SL, Lu M, et al. Second-generation replication-competent oncolytic adenovirus armed with improved suicide genes and ADP gene demonstrates greater efficacy without increased toxicity. Mol Ther. 2006;13:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wein LM, Wu JT, Kirn DH. Validation and analysis of a mathematical model of a replication-competent oncolytic virus for cancer treatment: implications for virus design and delivery. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1317–1324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doronin K, Toth K, Kuppuswamy M, Ward P, Tollefson AE, Wold WSM. Tumor-specific, replication-competent adenovirus vectors overexpressing the adenovirus death protein. J Virol. 2000;74:6147–6155. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6147-6155.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toth K, Tarakanova V, Doronin K, Ward P, Kuppuswamy M, Locke JL, et al. Radiation increases the activity of oncolytic adenovirus cancer gene therapy vectors that overexpress the ADP (E3-11.6K) protein. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10:193–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lichtenstein DL, Spencer JF, Doronin K, Patra D, Meyer J, Shashkova EV, et al. An acute toxicology study with INGN 007, an oncolytic adenovirus vector, in mice and permissive Syrian hamsters; comparisons with wild-type Ad5 and a replication-defective adenovirus vector. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:644–654. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2009.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ying B, Toth K, Spencer JF, Meyer J, Tollefson AE, Patra D, et al. INGN 007, an oncolytic adenovirus vector, replicates in Syrian hamsters but not mice: comparison of biodistribution studies. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:625–637. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2009.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barker DD, Berk AJ. Adenovirus proteins from both E1B reading frames are required for transformation of rodent cells by viral infection and DNA transfection. Virology. 1987;156:107–121. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tollefson AE, Kuppuswamy M, Shashkova EV, Doronin K, Wold WSM. Preparation and titration of CsCl-banded adenovirus stocks. Methods Mol Med. 2007;130:223–235. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-166-5:223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuppuswamy M, Spencer JF, Doronin K, Tollefson AE, Wold WS, Toth K. Oncolytic adenovirus that overproduces ADP and replicates selectively in tumors due to hTERT promoter-regulated E4 gene expression. Gene Therapy. 2005;12:1608–1617. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toth K, Spencer JF, Dhar D, Sagartz JE, Buller RM, Painter GR, et al. Hexadecyloxypropyl-cidofovir CMX001, prevents adenovirus-induced mortality in a permissive, immunosuppressed animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7293–7297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800200105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toth K, Spencer JF, Tollefson AE, Kuppuswamy M, Doronin K, Lichtenstein DL, et al. Cotton rat tumor model for the evaluation of oncolytic adenoviruses. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:139–146. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhar D, Spencer JF, Toth K, Wold WSM. Effect of preexisting immunity on oncolytic adenovirus vector INGN 007 antitumor efficacy in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed Syrian hamsters. J Virol. 2009;83:2130–2139. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02127-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhar D, Spencer JF, Toth K, Wold WS. Pre-existing immunity and passive immunity to adenovirus 5 prevents toxicity caused by an oncolytic adenovirus vector in the Syrian hamster model. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1724–1732. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas MA, Spencer JF, La Regina MC, Dhar D, Tollefson AE, Toth K, et al. Syrian hamster as a permissive immunocompetent animal model for the study of oncolytic adenovirus vectors. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1270–1276. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas MA, Spencer JF, Toth K, Sagartz JE, Phillips N, Wold WSM. Immunosuppression enhances oncolytic adenovirus replication and anti tumor efficacy in the Syrian hamster model. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1665–1673. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartline CB, Gustin KM, Wan WB, Ciesla SL, Beadle JR, Hostetler KY, et al. Ether lipid–ester prodrugs of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates: activity against adenovirus replication in vitro. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:396–399. doi: 10.1086/426831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dilley J, Reddy S, Ko D, Nguyen N, Rojas G, Working P, et al. Oncolytic adenovirus CG7870 in combination with radiation demonstrates synergistic enhancements of antitumor efficacy without loss of specificity. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005;12:715–722. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang P, Watanabe M, Kaku H, Kashiwakura Y, Chen J, Saika T, et al. Direct and distant antitumor effects of a telomerase-selective oncolytic adenoviral agent OBP-301, in a mouse prostate cancer model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;15:315–322. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan PC, Jakubczak JL, Stewart DA, Hawkins LK, Cheng C, Clarke LM, et al. Antitumor efficacy and tumor-selective replication with a single intravenous injection of OAS403, an oncolytic adenovirus dependent on two prevalent alterations in human cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:555–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spencer JF, Sagartz JE, Wold WSM, Toth K. New pancreatic carcinoma model for studying oncolytic adenoviruses in the permissive Syrian hamster. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:912–922. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2009.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alemany R. Cancer selective adenoviruses. Mol Aspects Med. 2007;28:42–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar S, Gao L, Yeagy B, Reid T. Virus combinations and chemotherapy for the treatment of human cancers. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2008;10:371–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lichtenstein DL, Toth K, Doronin K, Tollefson AE, Wold WSM. Functions and mechanisms of action of the adenovirus E3 proteins. Int Rev Immunol. 2004;23:75–111. doi: 10.1080/08830180490265556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]