Abstract

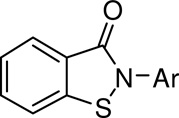

We report the discovery and validation of a series of benzoisothiazolones as potent inhibitors of phosphomannose isomerase (PMI), an enzyme which converts mannose-6-phosphate (Man-6-P) into fructose-6-phosphate (Fru-6-P), and more importantly, competes with phosphomannomutase 2 (PMM2) for Man-6-P, diverting this substrate from critical protein glycosylation events. In Congenital Disorder of Glycosylation type Ia, PMM2 activity is compromised, thus PMI inhibition is a potential strategy for the development of therapeutics. High-throughput screening (HTS) and subsequent chemical optimization led to the identification of a novel class of benzoisothiazolones as potent PMI inhibitors having little or no PMM2 inhibition. Two complimentary synthetic routes were developed enabling the critical structural requirements for activity to be determined, and the compounds were subsequently profiled in biochemical and cellular assays to assess efficacy. The most promising compounds were also profiled for bioavailability parameters including metabolic stability, plasma stability, and permeability. The pharmacokinetic profile of a representative of this series was also assessed, demonstrating the potential of this series for in vivo efficacy when dosed orally in disease models.

Introduction

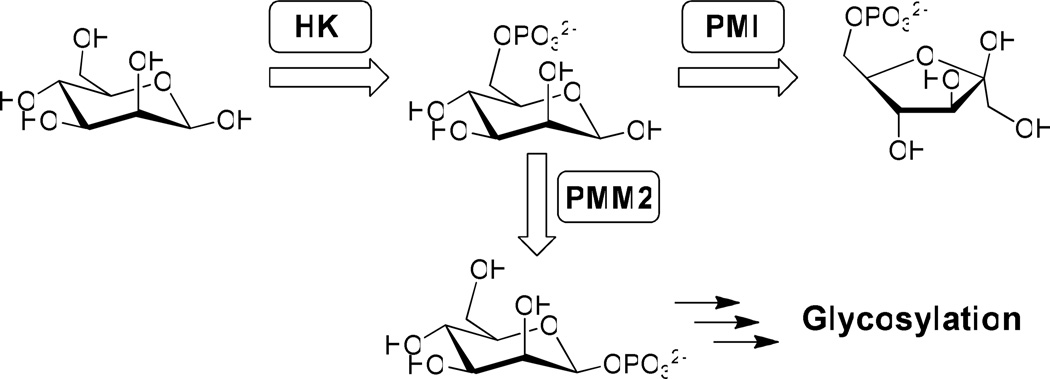

Congenital Disorder of Glycosylation Type Ia (CDG-Ia) is a genetic disorder caused by mutations in the pmm2 gene that leads to reduced phosphomannomutase 2 (PMM2) enzyme activity. PMM2 plays an important role in N-glycosylation by competing with phosphomannose isomerase (PMI) for a common substrate, mannose-6-phosphate (Man-6-P), and converting it to mannose-1-phosphate which ultimately enters the N-glycosylation pathway (Figure 1). Any aberration in PMM2 results in underglycosylation of proteins in CDG-Ia patients and this leads to multi-organ symptoms including neurological problems. There is currently no therapy for CDG-Ia patients and the prognosis is extremely poor.1

Figure 1.

Phosphomannose isomerase (PMI) and phosphomannomutase (PMM2) are important regulators of glycosylation. Inhibitors were designed to inhibit PMI but not PMM2, facilitating the accumulation of mannose-6-phosphate to drive glycosylation (HK = hexokinase).

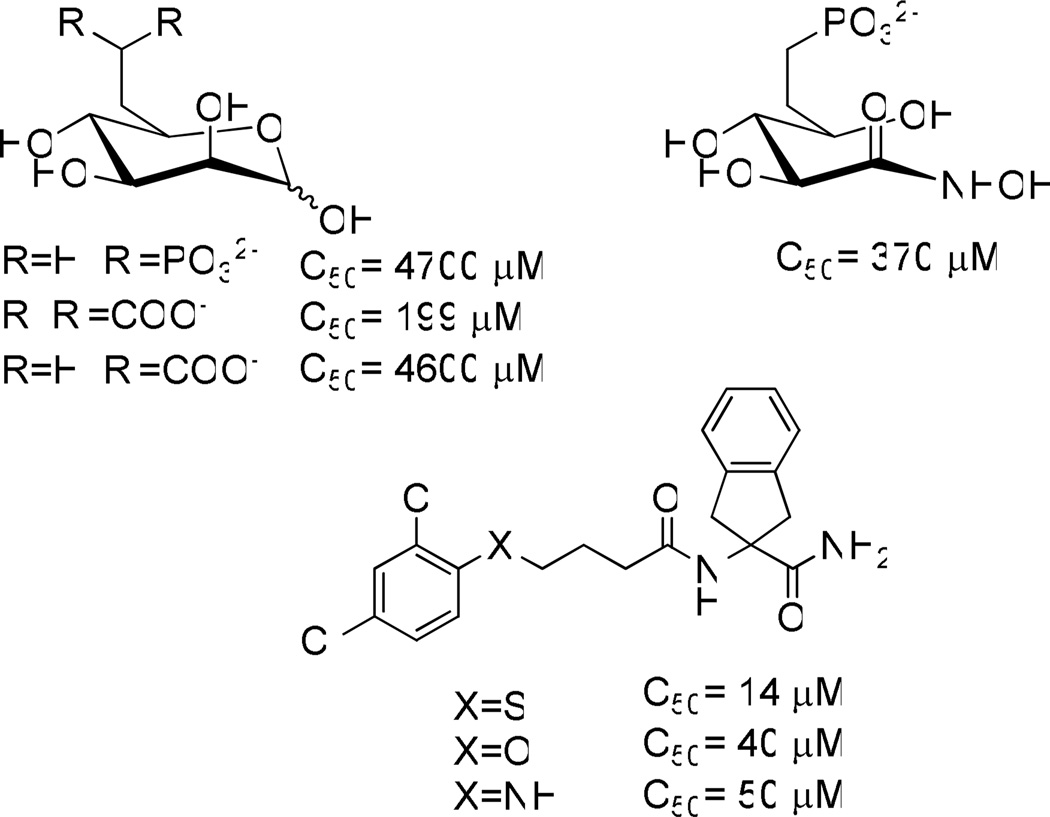

Unfortunately, mannose therapy alone does not benefit CDG-Ia patients since most of the supplied mannose is catabolized by PMI and is therefore unavailable for glycosylation. We hypothesized that CDG-Ia patients might benefit from dietary mannose supplementation combined with inhibition of phosphomannose isomerase (PMI) using small molecule inhibitors selective for PMI over PMM2, thus diverting metabolic flux towards the glycosylation pathway (Figure 1).1a, 2 Small molecule inhibitors of PMI are scarce. The only inhibitors reported are either substrate based or show very weak inhibition (Figure 2).3 In contrast, many of our newly discovered inhibitors have more than a 10 fold increase in potency over the most potent of the previously reported inhibitors. In addition, no cell-based efficacy or selectivity over PMM2 has been reported for any PMI inhibitors prior to this work. Herein we disclose the discovery and validation of benzoisothiazolone derivatives that are selective inhibitors of human PMI. This class shows favorable ADME profiles and a representative compound is orally available when dosed in mice. These compounds are viable leads for the development of novel therapeutics to treat CDG-Ia.

Figure 2.

Structures and activities of previously reported PMI inhibitors.3

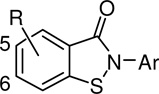

Results and Discussion

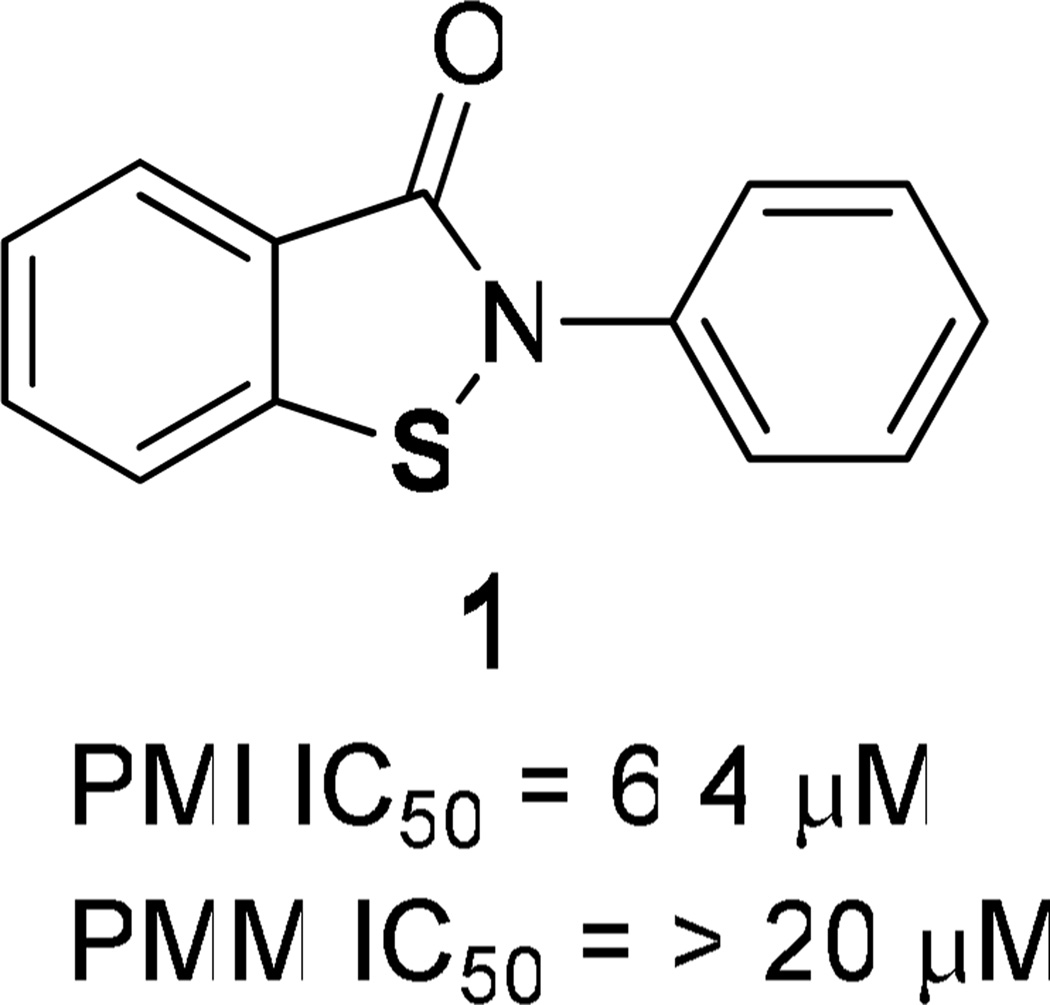

High-throughput screening (HTS) of 196,000 compounds from the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) was conducted to identify small molecule inhibitors of PMI. Since compounds of interest were expected to show efficacy in an environment rich in mannose-6-phosphate content resulting from PMM2 deficiency and a supply of external mannose, we were specifically interested in identifying compounds with non- or uncompetitive modes of inhibition. To help select the most promising scaffolds, parallel primary screening was performed in the presence of 2 × Km and 10 × Km concentrations of mannose-6-phosphate. Compounds of interest were expected to be efficacious in both assays. Among the confirmed hits that inhibited in both assays was a novel class of benzoisothiazolones showing robust PMI inhibition, PMI/PMM2 selectivity, and a structure amenable to optimization of both biological activity and drug properties. This series is exemplified by compound 1 (Figure 3), a PMI inhibitor which was among the HTS hits chosen for follow up. While this compound was selective for PMI over PMM2 when tested up to 20 µM, it was recognized as a relatively weak inhibitor of PMI (IC50 = 6.4 µM). Thus, due to the observed PMI/PMM2 selectivity and the potential for parallel synthesis, we initiated structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies around this scaffold to optimize potency, selectivity, and cellular PMI inhibitory activity. In addition, the most promising compounds were evaluated for their absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) and pharmacokinetic (PK) properties with the goal of developing a compound with a profile suitable for in vivo proof-of-concept studies.

Figure 3.

Benzoisothiazolone PMI inhibitor HTS hit.

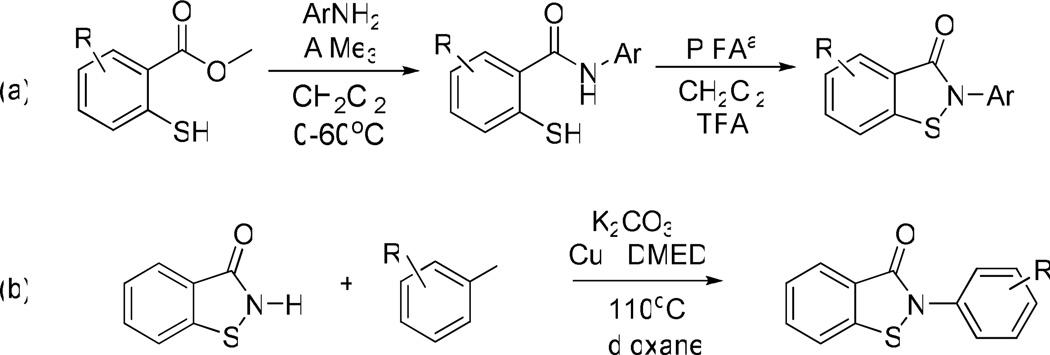

Chemical Synthesis

To facilitate the generation of analogues, two chemical routes were developed to enable parallel synthesis of chemical libraries around the benzisothiazolone scaffold (Scheme 1). The first route utilized chemistry developed by Correa et al.4 and involved a key cyclization step using phenyliodine bis(trifluoroacetate) (PIFA) to generate a N-acylnitrenium ion followed by intramolecular trapping by sulfur (Scheme 1, a). This synthetic methodology allowed for substitution of both aromatic portions of the molecule and was utilized particularly to probe the effects of substituents on the core benzisothiazolone ring.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of benzisothiazolones via (a) acylnitrenium ion mediated cyclization or (b) copper catalyzed N-arylation. aphenyliodine bis(trifluoroacetate)

To efficiently assess the effects of substituents on the N-phenyl ring, we developed a copper-mediated Ullman-type N-arylation reaction, based on a variation of methods reported by Buchwald and others.5 Beginning from commercially available benzoisothiazolone, this reaction employs catalytic amounts of copper iodide and N,N’-dimethylethylenediamine as the ligand (Scheme 1, b). These conditions allowed rapid access to a diverse set of analogues in one step. It should also be noted that other ligands and copper sources were also screened. Generally, diamines and CuI gave the best overall yields (yield range 6–42%), although CuCl and Cu2O were almost as effective. This reaction was also performed using microwave irradiation with acceptable product recovery in minutes. This is the first example of N-arylation chemistry of this heterocycle type and allowed rapid interrogation of the N-aryl species. Using a combination of both routes, the relevant sites of SAR were investigated to afford optimal substitutions with respect to PMI potency, PMM2 selectivity, and cellular efficacy.

Biochemical Evaluation

The potency and selectivity of the synthesized compounds were assessed by in vitro enzymatic assays using purified human PMI and PMM2. The effects of substitution on the pendant N-phenyl ring on PMI and PMM2 inhibition are shown in Table 1. Like the lead compound 1, all of the synthesized derivatives showed selectivity for PMI over PMM2, with the exception of the 4-trifluoromethylphenyl derivative 6 which was inactive against both enzymes. In general, para substitution was favored over meta, with a two- to three-fold increase in PMI inhibition seen. The exceptions to this trend included trifluoromethyl substitution (compounds 5 and 6) and ester substitution (9 and 10). The effect of ortho substitution was explored with compound 16. In comparison to compound 3, the des-methyl variant of this compound, little effect on PMI activity was seen. However, a measurable inhibition of PMM2 was observed (Table 1). Some notable examples for overall potency and selectivity include compound 8 with a PMI IC50 of 1.8 µM, and compound 12 which showed comparable activity. These compounds were identified as promising leads for further optimization.

Table 1.

SAR of N-phenyl ring substituents. PMI and PMM assay data are the mean of at least three determinations. See Experimental Section for assay details.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| cmpd | Ar | PMI IC50 (µM) |

PMM2 IC50 (µM) |

| 1 | Ph | 6.4 | >20 |

| 2 | 2-naphthyl | 9.4 | >20 |

| 3 | 3-Me-Ph | 6.0 | >20 |

| 4 | 4-Me-Ph | 5.2 | >20 |

| 5 | 3-CF3-Ph | 3.4 | 13.9 |

| 6 | 4-CF3-Ph | >20 | >20 |

| 7 | 3-Cl-Ph | 4.8 | >20 |

| 8 | 4-Cl-Ph | 1.9 | >20 |

| 9 | 3-COOMe-Ph | 4.9 | 15.4 |

| 10 | 4-COOEt-Ph | 7.2 | >20 |

| 11 | 3-N(Me)2-Ph | 8.5 | >20 |

| 12 | 4-N(Me)2-Ph | 1.9 | 13.3 |

| 13 | 3-I-Ph | 4.3 | >20 |

| 14 | 4-tBu-Ph | 5.0 | >20 |

| 15 | 3-OMe-Ph | 3.7 | >10 |

| 16 | 2,5-di-Me-Ph | 6.6 | 17.9 |

Next, the effects of fluorine substitution at positions 5 and 6 on the core benzisothiazolone aryl ring were assessed with respect to PMI potency and PMM2 selectivity (Table 2). Generally, fluorine substitution at these positions afforded an overall increase in PMI potency with all of the examples maintaining selectivity over PMM2. For example, compound 19 which has an unsubstituted phenyl ring and fluorine at the 5 position of the fused aryl ring had a PMI IC50 of 1.3 µM, compared to the analogous des-fluoro derivative 1, which had a PMI IC50 of 6.4 µM. In addition, both of these compounds were inactive against PMM2 when tested up to 20 µM. An exception to this trend was seen with the 4-chloro substituted compounds 24 and 8, with PMI IC50 values of 1.8 µM and 1.9 µM, respectively. The most potent compounds were in this series, specifically the di-methyl substituted 17 with fluorine in the 6-position and the 4-methoxy derivative 22 with fluorine in the 5 position. These derivatives both showed PMI inhibition of 1.0 µM, representing a full fold-better potency than the most potent derivatives from the previous des-methyl series. While inhibition of PMM2 was seen in these most potent examples, they still maintained a 7–9 fold selectivity for PMI.

Table 2.

SAR of fluorine substituted benzisothiazolones. PMI and PMM2 assay data are the mean of at least three determinations. See Experimental Section for assay details.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cmpd | R | Ar | PMI IC50 (µM) |

PMM2 IC50 (µM) |

| 17 | 6-F | 2,5-di-Me-Ph | 1.0 | 7.3 |

| 18 | 6-F | 4-OMe-Ph | 3.1 | 12.9 |

| 19 | 5-F | Ph | 1.3 | >80 |

| 20 | 5-F | 2,5-di-Me-Ph | 1.9 | 31.3 |

| 21 | 5-F | 4-F-Ph | 3.6 | >80 |

| 22 | 5-F | 4-OMe-Ph | 1.0 | 9.1 |

| 23 | 5-F | 2-F-Ph | 4.3 | >20 |

| 24 | 5-F | 4-Cl-Ph | 1.8 | >20 |

| 25 | 5-F | 3-F-Ph | 8.3 | >20 |

| 26 | 6-F | 2-Me-Ph | 2.9 | >20 |

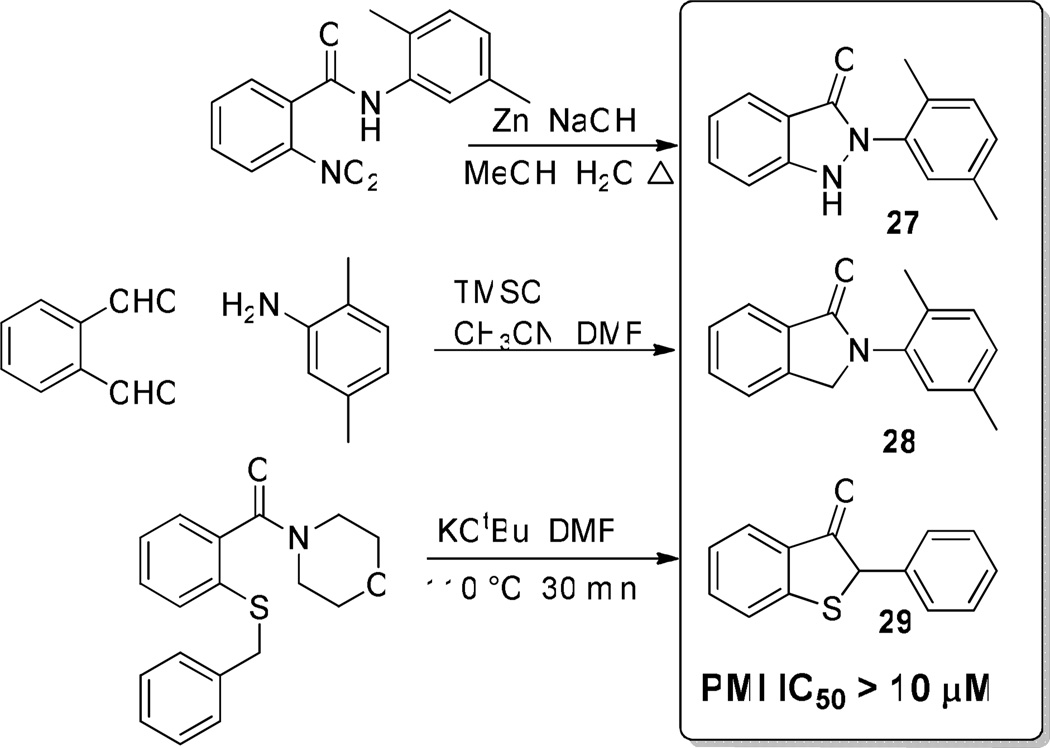

Finally, the importance of heteroatoms in the benzisothiazolone ring was investigated. To accomplish this, selected analogues were synthesized with the nitrogen and sulfur atoms in the benzisothiazolone ring either removed or replaced (compounds 27–29, Scheme 2). As can be seen, all of these modifications abrogated all PMI activity when tested up to 10 µM in the enzyme assay. These data support the importance of the benzisothiazolone ring system for PMI inhibition.

Scheme 2.

Replacement of heteroatoms of the benzisothiazolone abolished all PMI inhibition.

Cellular Evaluation

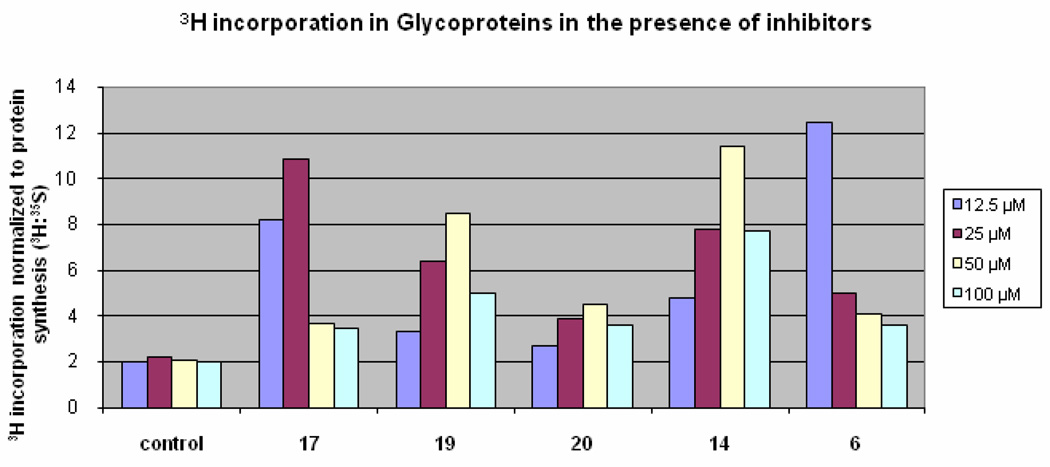

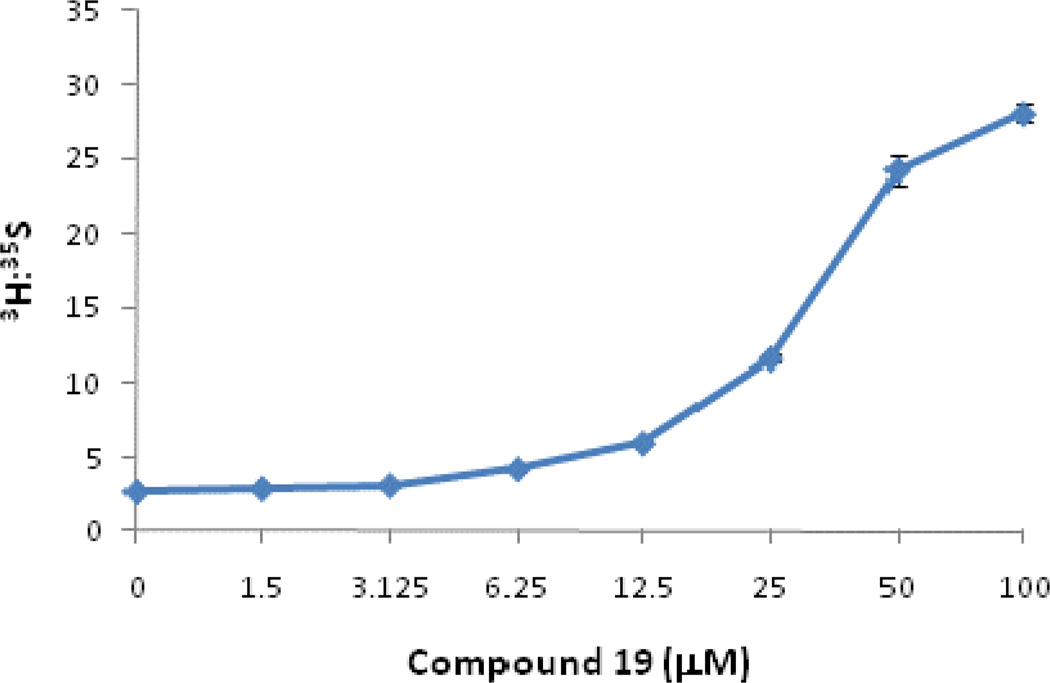

A cellular assay was developed to evaluate the biological and functional efficacy of the PMI inhibitors. [2-3H]-Mannose is a specific label which is used to measure the amount of mannose that is incorporated into glycoproteins versus that which is catabolized (Figure 1). In the presence of PMI inhibitors, more 3H-mannose will be diverted towards PMM2 resulting in more of the 3H radiolabel present in glycoproteins compared with untreated cells. Representative PMI inhibitors that display reproducible cellular activity are shown in Figure 4. Briefly, cells were incubated with inhibitor and labeled with 3H-mannose and 35S-Met/Cys. The amount of 3H- and 35S radiolabel were then determined in the precipitated proteins. The 35S label was included to determine the protein synthesis capacity of the cells as well as the toxicity. Decreased 35S-Met/Cys incorporation at high concentration was observed for some compounds. This was attributed to off-target activity because similar effects were observed in PMI null cells (data not shown). Similarly, the toxicity was unlikely to be due to PMM2 inhibition because PMM2-deficient CDG-Ia patient fibroblasts with 20% or less residual PMM2 activity grow slowly but normally in the presence of the PMI inhibitors, and do not show less 35S-incorporation into the glycoproteins. Compound 6, which was inactive against both PMI and PMM2, was included as an example of a compound that exhibits cellular toxicity in the assay. While all of the PMI inhibitors display enhanced glycosylation as indicated by increased 3H-mannose incorporation, compounds 14 and 19 both show a favorable combination of cellular efficacy with lessened toxicity. While compound 19 is the most potent compound in vitro, the maximal efficacy in cells appeared to be slightly lower than other derivatives (Figure 4). This may be due to the membrane permeability of compound 19, as it is predicted to be moderately permeable when assessed in vitro (Table 3). However, based on it’s overall profile, compound 19 was selected for evaluation at an extended range of inhibitor concentrations and displayed a dose dependent-increase in mannose incorporation (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Cell based PMI Inhibitor data. Shown is the 3H-mannose incorporation normalized to 35S protein synthesis in the presence of increasing inhibitor concentrations.

Table 3.

ADME profiles of selected PMI inhibitors.

| cmpd | Solubility pH 7.4 (µg/mL) |

Log Pea | Plasma Stabilityb (mouse) |

Microsomal Stabilityb (mouse) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 2.5 | −2.8 | 10 | 62 |

| 17 | 22.5 | −2.9 | 48 | 82.3 |

| 19 | 3.8 | −3.2 | 99 | 85 |

| 20 | 11 | −2.9 | ND | 81 |

Permeability determined by PAMPA assay.

Percent of compound remaining after incubation for 3 h (plasma) or 1 h (microsomes) at 37 °C.

Figure 5.

Cell based efficacy of compound 19. Shown is the 3H-mannose incorporation normalized to 35S protein synthesis in the presence of increasing concentrations of 19.

In vitro ADME Profiling

The PMI inhibitors with the most favorable cellular efficacy were also profiled in in vitro ADME assays to assess their drug-likeness6 and potential for systemic activity in animal models. Many of the benzisothiazolones were shown to have suitable properties for oral administration including acceptable metabolic and plasma stabilities, good permeability across artificial lipid membranes, and good solubility. The results of the specific in vitro ADME profiling assays are shown in Table 3. Although the profiles of many of the synthesized analogues had drug-like ADME profiles, it was clear that in addition to showing acceptable aqueous solubility at physiological pH, the mouse plasma and microsomal stabilities of 19 were superior (Table 3). Compound 19 was therefore selected for additional studies, including its propensity to generate glutathione (GSH)-trapped reactive metabolites. The S9-based GSH transferase assay has been shown to be a reliable means of identifying compounds known to react with GSH in vivo. When tested in the presence of rat liver S9 fraction for 2 hours in the presence of glutathione, the quantity of 19 was not significantly reduced and no GSH adducts were observed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS) analysis.

In vivo Pharmacokinetics

Based on the promising properties displayed by compound 19, potent PMI inhibition, PMI/PMM2 selectivity, cellular efficacy with low toxicity, and a favorable ADME profile, the pharmacokinetics and oral availability of this compound were evaluated in mice to enable future advanced studies in CDG-Ia disease models. To this end, compound 19 was dosed at 5 mg/kg IV and 20 mg/kg p.o. in mice. As predicted by the favorable ADME profile, the bioavailability of 19 (F = 35%) was satisfactory. The various pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table 4. Overall, the compound has a good PK profile with acceptable parameters to enable future in vivo efficacy experiments.

Table 4.

PK parameters of compound 19.

| cmpd | oral dose (mg/kg) |

Cmax (nM) |

Tmax (min.) |

AUC (0-t) (nM·h) |

t1/2 (h) | F (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 20 | 162 ± 32 | 45 ± 21 | 305 ± 34 | 1.3 ± 0.64 | 35 |

Conclusion

A series of novel, drug-like benzisothiazolone inhibitors of PMI were synthesized and their ability to modulate flux towards glycosylation has been demonstrated. Two synthetic routes for this scaffold were optimized, including a novel copper-catalyzed N-arylation reaction amenable to parallel derivitization. These compounds are the most potent inhibitors of PMI to date, and their dose-dependent efficacy in cells has been demonstrated. In addition, they are selective over PMM2 at all concentrations tested. The compounds possess favorable ADME and PK profiles, including good oral bioavailability, which should enable the further therapeutic development of these compounds.

Experimental Section

Compound collection utilized in HTS

The compound library was supplied by the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR, http://www.mli.nih.gov/mlsmr). The MLSMR, funded by the NIH, is responsible for the selection of small molecules for HTS screening, their purchase and QC analysis, library maintenance and distribution within the NIH Molecular Libraries Screening Center Network (MLSCN, http://www.mli.nih.gov/mlscn). Both MLSMR and MLSCN are parts of the Molecular Libraries Initiatives (MLI, http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/molecularlibraries) under the NIH Roadmap Initiative (www.nihroadmap.nih.gov). MLSMR compounds are acquired from commercial, and in part from academic and government sources and are selected based on the following criteria: samples are available for re-supply in 10 mg quantity, are at least 90% pure, have acceptable physicochemical properties and contain no functional groups or moieties which are known to generate artifacts in HTS (http://mlsmr.glpg.com/). Compounds are selected to represent diversified chemical space with clusters of closely related analogues around them to aid in the HTS-based SAR analysis.

In vitro assays

For concentration-response assays, 9 µL of the substrate solution was dispensed into 384-well black plates (Greiner 784076), and either the compound (2 µL in 10% DMSO) or 10% DMSO alone were added for the test and control wells, respectively. The reaction was initiated with 9 µL of the enzyme solution. Fluorescence in the rhodamine channel (excitation: 544 nm, emission: 590 nm; dichroic mirror 561 nm) was measured on a Molecular Devices Analyst HT after a 20 min. incubation at room temperature.

The PMI substrate solution contained 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 0.4 mM mannose-6-phosphate, 1.6 IU/mL diaphorase, and 0.2 mM resazurin. The PMI enzyme solution contained 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 0.5 mM NADP+, 10 mM MgCl2, 4.6 µg/mL phosphoglucose isomerase, 2 µg/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 30 ng/mL PMI and 0.011% Tween 20 (PubChem AID 1209). In the primary screening, the same assay was also performed in the presence of saturating PMI substrate concentrations. Both working solutions had the composition as above, except for 2 mM mannose-6-phosphate in the substrate solution (PubChem AID 1220).

The PMM2 substrate solution contained 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 0.17 mM mannose-1-phosphate, 0.4 IU/mL diaphorase, 56 µM resazurin. The PMM2 enzyme solution contained 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 1.1 mM NADP+, 0.11 mM alpha-D-glucose 1,6-bisphosphate, 5 µg/mL phosphoglucose isomerase, 3.33 µg/mL PMI, 2 µg/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 1.67 µg/mL PMM2, and 0.011 % Tween 20 (PubChem AID 1655). Mannose-6-phosphate and mannose-1-phosphate were omitted from the positive control wells for PMI and PMM2, respectively. The IC50 values were determined using non-linear regression data analysis according to the Hill equation.

General Synthetic Procedures

All solvents and chemicals used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Acros, or Chembridge and were used as received without further purification. Purity and characterization of compounds were established by a combination of liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy (LC-MS), and NMR analytical techniques and was >95% for all tested compounds. Silica gel column chromatography was carried out using prepacked silica cartridges from RediSep (ISCO Ltd.) and eluted using an Isco Companion system. 1H NMR spectra were acquired on a Varian Inova 300 MHz instrument. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm from residual solvent peaks (δ 7.27 for CDCl3 1H NMR). HPLC-MS analyses were performed on a Shimadzu 2010EV LCMS using the following conditions: Kromisil C18 column (reverse phase, 4.6 mm × 50 mm); a linear gradient from 10% acetonitrile and 90% water to 95% acetonitrile and 5% water over 4.5 min; flow rate of 1 mL/min; UV photo-diode array detection from 200 to 300 nm.

General methods for the synthesis of benzoisothiazolone PMI inhibitors

General method A: To a stirred solution of the amine (900 mg, 5.95 mmol) in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C under nitrogen, AlMe3 (6 mL, 2 M in THF) was added dropwise and the reaction was slowly warmed to room temperature. The mixture was stirred continuously for an additional 30 min. Methyl thiosalicylate (500 mg, 2.97 mmol) was added and the reaction was heated to 60 °C and heated under reflux overnight. The reaction was quenched with HCl (5% aq.) and CH2Cl2 was added (50 mL). The organic layer was separated and washed with saturated NaHCO3 solution, then brine, and dried over Na2SO4. The solvents were removed by rotary evaporation and the products were isolated by flash chromatography or reverse phase HPLC and lyophilized to provide the final compounds which were determined to be >95% pure by HPLC-UV, HPLC-MS, and 1H NMR. General method B: To a crimp top microwave vial was added the benzoisothiazolone (76 mg, 0.5 mmol), aryl-X (1.05 mmol), K2CO3 (138 mg, 1.0 mmol), CuI (20 mol%), and DMEDA (20 mol%) in dioxane (5 mL). The reaction mixture was heated in the microwave at 195 °C for 7 min. Following filtration and evaporation of solvents, the products were isolated by flash chromatography or reverse phase HPLC and lyophilized to provide the final compounds which were determined to be >95% pure by HPLC-UV, HPLC-MS, and 1H NMR.

2-Phenyl-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (1)

Prepared according to general procedure A (67%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ7.32(m, 1H), 7.51(m, 3H), 7.57(m, 1H), 7.67(m, 3H), 8.09(m, J= 7.9, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3):120.0, 124.6, 125.8. 127.0, 127.2, 129.3, 132.3, 137.2, 139.9, 164.1. ESI-MS m/z 227 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C13H9NOS [M + H]+: 228.0405. Found: 228.0522.

2-(3-Methylphenyl)-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (3)

Prepared according to general procedure B (22%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ2.40(s, 3H), 7.12(d, J=7.3, 1H), 7.33(t, J= 7.9, 1H), 7.49(m, 4H), 7.62(m, 1H), 8.08(d, J=7.9, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 241 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C14H11NOS [M + H]+: 242.0561. Found: 242.0672.

2-(4-Methylphenyl)-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (4)

Prepared according to general procedure B (6%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ2.37(s, 3H). 7.26(m, 3H), 7.42(m, 1H), 7.55(m, 2H), 7.64(m, 1H), 8.08(m, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 241 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C14H11NOS [M + H]+: 242.0561. Found: 242.0673.

2-[3-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (5)

Prepared according to general procedure B (15%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ7.46(t, J=7.9, 1H), 7.58(m, 3H), 7.68(m, 1H), 7.93(d, J=7.9, 1H), 8.01(s, 1H), 8.10(d, J= 7.9, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 295 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C14H8F3NOS [M + H]+: 296.0279. Found: 296.0391.

2-[4-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (6)

Prepared according to general procedure B (27%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ7.59(m, 5H), 7.90(m, 2H), 8.10 (d, J= 7.3, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 295 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C14H8F3NOS [M + H]+: 296.0279. Found: 296.0390.

2-(3-Chlorophenyl)-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (7)

Prepared according to general procedure B (15%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ7.26(m, 1H), 7.42(m, 2H), 7.62(m, 3H), 7.78(m, 1H), 8.09(m, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 261 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C13H8ClNOS [M + H]+: 262.0015. Found: 262.0092.

2-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (8)

Prepared according to general procedure B (12%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ7.43(m, 3H), 7.57(d, J= 7.9, 1H), 7.65(m, 3H), 8.05(d, J=7.9, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 261 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C13H8ClNOS [M + H]+: 262.0015. Found: 262.0098.

2-[4-(Dimethylamino)phenyl]-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (12)

Prepared according to general procedure B (38%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ2.97(s, 6H), 6.75(m, 2H), 7.42(m, 3H), 7.54(m, 1H), 7.60(m, 1H), 8.07(d, J= 7.3, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 40.5, 112.5, 120.0, 124.8, 125.4, 125.5, 126.8, 127.0, 131.9, 140.2, 149.9, 164.4. ESI-MS m/z 270 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C15H14N2OS [M + H]+: 271.0827. Found: 271.078.

2-(3-Iodophenyl)-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (13)

Prepared according to general procedure B (18%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ7.17(t, J= 7.9, 1H), 7.44(m, 1H), 7.66(m, 4H), 8.08(m, 2H). 13C NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): 94.1, 120.1, 123.6, 125.0, 126.0, 127.3, 130.7, 132.6, 133.0, 136.0, 138.3, 139.6, 164.0. ESI-MS m/z 352 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C13H8INOS [M + H]+: 353.9371. Found: 353.9492.

2-[4-(tert-Butyl)phenyl]-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (14)

Prepared according to general procedure B (42%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ1.33(s, 9H), 7.46(m, 3H), 7.61(m, 4H), 8.10(d, J=7.9, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 31.3, 34.7, 120.0, 124.4, 125.7, 126.3, 127.1, 132.2, 134.4, 150.3, 164.2. ESI-MS m/z 283 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C17H17NOS [M + H]+: 284.1031. Found: 284.1131.

2-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (15)

Prepared according to general procedure B (12%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ3.84(s, 3H), 6.81(m, 1H), 7.25(m,1H), 7.36(m, 2H), 7.43(m, 1H), 7.57(m, 1H), 7.65(m, 1H), 8.09(m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 55.5, 110.1, 113.1, 164.5, 120.0, 125.0, 125.8, 127.1, 130.0, 132.4, 138.3, 140.0, 160.2, 164.1. ESI-MS m/z 257 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C17H17NO2S [M + H]+: 258.0510. Found: 258.0622.

2-(2,5-dimethylphenyl) benzo[d]isothiazol-3(2H)-one (16)

Prepared according to general procedure B (18%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ2.18(s, 3H), 2.35(s, 1H), 7.19(m, 3H), 7.43(m, 1H), 7.56(m, 1H), 7.65(m, 1H), 8.09(d, J=7.93, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 256 [M + H]+.

2-(2,5-Dimethylphenyl)-6-fluorobenzo[d]isothiazol-3(2H)-one (17)

To a stirred solution of the 4-fluoro-2-mercaptobenzoic acid (10mmol) in ethyl acetate, was added 2-propanephosphonic acid anhydride (30mmol) and this mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 minutes. 2,5-dimethylaniline (10 mmol) and N-methylmorpholine (120 mmmol) were added, and the reaction was stirred at room temperature for 3 hours, quenched with ethyl acetate and washed with a 5 % potassium sulfate solution, saturated sodium bicarbonate solutions, brine, and dried over sodium sulfate. The organic mixture was concentrated in vacuo and purified by reverse-phase preparative liquid chromatography to afford the product in 40% yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ2.19 (s, 3H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 7.18 (m, 5H), 8.09 (m, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 274 [M + H]+.

6-Fluoro-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)benzo[d]isothiazol-3(2H)-one (18)

1H NMR (500 MHz, (CD3)2SO): δ2.18(s, 3H), 2.35(s, 1H), 7.19(m, 3H), 7.43(m, 1H), 7.56(m, 1H), 7.65(m, 1H), 8.09(d, J=7.9, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 276 [M + H]+.

5-Fluoro-2-phenylbenzo[d]isothiazol-3(2H)-one (19)

Prepared according to general procedure A (51%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ7.33(m, 1H), 7.45(m, 3H), 7.54(m, 1H), 7.67(m, 2H), 7.77(dd, J=2.4, 7.9, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 113.0, 113.3, 121.0, 121.3, 121.6, 121.7, 124.6, 127.3, 129.4, 135.1, 137.0, 160.1, 162.5. ESI-MS m/z 273 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C15H12FNOS [M + H]+: 274.0624. Found: 274.0739.

5-Fluoro-2-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (20)

Prepared according to general procedure A (65%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): 7.76(dd, J=2.4, 7.9, 1H), 7.67 (m, 2H), 7.54 (m, 1H), 7.44 (m, 3H), 7.31 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 40.5, 112.5, 120.0, 124.8, 125.4, 125.5, 126.8, 127.0, 131.9, 140.2, 149.9, 164.3. ESI-MS m/z 245 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C13H8FNOS [M + H]+: 246.0311. Found: 246.0395.

5-Fluoro-2-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (21)

Prepared according to general procedure A (33%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ7.15(m, 2H), 7.42(m, 1H), 7.54(m, 1H), 7.62(m, 2H), 7.76(dd, J=2.4, 7.9, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 263 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C13H7F2NOS [M + H]+: 264.0216. Found: 264.0299.

5-Fluoro-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (22)

Prepared according to general procedure A (80%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ3.83(s, 3H), 6.97(m, 2H), 7.41(m, 1H), 7.52(m, 3H), 7.76(dd, J=2.4, 7.9, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 55.6, 113.0, 113.2, 114.6, 126.8, 129.4, 135.2, 159.0, 162.4. ESI-MS m/z 275 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C14H10FNO2S [M + H]+: 276.0416. Found: 276.0499.

5-Fluoro-2-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (23)

Prepared according to general procedure A (47%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): 8.12 (m, 1H), 7.67 (m, 1H), 7.58(m, 1H), 7.44 (m, 3H), 7.22 (m, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 263 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C13H7F2NOS [M + H]+: 264.0216. Found: 264.0404.

2-(4-Chlorophenyl)-5-fluoro-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (24)

Prepared according to general procedure A (55%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ7.42(m, 3H), 7.54(m, 1H), 7.63(m, 2H), 7.76(dd, J=2.4, 7.9, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 278 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C13H7ClFNOS [M + H]+: 279.9921. Found: 280.0017.

5-Fluoro-2-(3-fluorophenyl)-2-hydrobenzo[d]isothiazol-3-one (25)

Prepared according to general procedure A (60%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.02(m, 1H), 7.43(m, 3H), 7.54(m, 2H), 7.75(dd, J= 2.4, 7.9, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 263 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C13H7F2NOS [M + H]+: 264.0216. Found: 264.0305.

6-Fluoro-2-o-tolylbenzo[d]isothiazol-3(2H)-one (26)

Prepared according to general procedure A (55%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ2.17(s, 3H), 2.33(s, 3H), 7.18(m, 3H), 7.41(m, 1H), 7.53(m, 1H), 7.78(dd, J= 2.4, 7.9, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 273 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C15H12FNOS [M + H]+: 274.0624. Found: 274.0734.

2-Phenyl-1H-2-hydroindazol-3-one (27)

A solution of o-nitrobenzaldehyde (242 mg, 1 mmol) in methanol (3 mL) was added to sodium hydroxide in water (4 mL) together with zinc dust. The resulting reaction mixture was then heated under reflux for 15 h and filtered while hot. The filtrate was concentrated to half volume and cooled. Any unreacted material was removed by filtration. The filtrate was diluted with water and acidified with dilute HCl. The crude product precipitated was collected by filtration and further purified by column chromatography using hexanes:ethyl acetate to afford 0.076 g (36%) of indazolone as a pale yellow solid. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ2.24(s, 3H), 2.31(s, 3H), 7.19(m, 7H), 7.55(m. 1H), 7.89(m,1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3):17.6, 20.7, 112.3, 118.5, 122.6, 124.2, 127.8, 129.8, 130.9, 132.1, 132.9, 134.8, 136.4, 147.1, 161.7. ESI-MS m/z 238 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C15H14N2O [M + H]+: 239.1106. Found: 239.1205.

2-(2,5-Dimethylphenyl)isoindolin-1-one (28)

To a stirred solution of the phthalaldehyde (250 mg, 1.85 mmol) in CH3CN: DMF was added the amine (230 uL, 1.85 mmol) followed by TMSCl (188 uL, 1.48 mmol). Stirred at room temperature over night (62%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ2.18(s, 3H), 2.31(s, 3H), 4.70(s, 2H), 7.18(m, 2H), 7.52(m, 3H), 7.93(m, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 237 [M + H]+. HRMS m/z calcd for C16H15NO [M + H]+: 238.1154. Found: 238.1276.

Permeability assay

The capacity of compounds to cross cellular membranes was determined using a Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeation Assay (PAMPA).7 Briefly, the effective permeability of the compounds was measured at an initial concentration of 25 µM. The buffer solution (pH 7.4) was prepared from a concentrated stock available from pION, and according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The compound of interest was dissolved in buffer solution or water (in the case of cargos alone, evaluated by HPLC-MS) and acetonitrile (20%, cosolvent) to the desired concentration. The sandwich plate was separated, and the donor well was filled with 200 µL of the compound solution of interest. The acceptor plate was placed into the donor plate, ensuring that the underside of the membrane was in contact with buffer. Four µL of the mixture of phospholipids (20 mg/mL) in dodecane was added to the filter of each well, followed by 200 µL of buffer solution. The plate was covered and incubated at room temperature in a saturated humidity atmosphere for 4 h under orbital agitation at 100 rpm. The concentrations of the compound remaining in the donor well, diffused through the membrane and into the acceptor well, and reference compounds were measured by LC/MS/MS. Results were classified as High, Medium, or Low predicted absorption. Test articles were run in triplicate at one concentration (25 µM) and permeability assessed at one time point (4 h) and pH (7.4). The membrane consisted of phosphatidylcholine in dodecane on a Multiscreen PVDF membrane (0.45 µm). Positive control was verapamil (high permeability) and negative control was theophylline (low permeability).

Plasma and microsomal stability assays

Test articles were run in duplicate in the presence of either fresh plasma (mouse) or 0.5 mg/ml liver microsomes (mouse) at one concentration of test compound (10 µM). Aliquots were taken at two time points, t=0 h and t=1 h (microsomes) or t=3 h (plasma). LC/MS/MS measurement of remaining parent compound as % parent remaining at a specific time point was assessed. For microsomal stability the positive control was formation of acetaminophen from phenacetin and the negative control was an NADPH deficient test mixture.

Glutathione conjugation assay

To assess the potential of compound 19 for covalent modification, the glutathione transferase activity in rat hepatic S9 fraction was measured.8 Compound 19 was incubated at 10 µM in PBS buffer with 2 mg/mL rat hepatic S9 fraction and 10 mM glutathione at 37°C for 2 hours. The incubation was stopped by protein precipitation using acetonitrile. After drying down the supernatant, the residues were reconstituted and analyzed by positive-ion electrospray LCMS and analyzed for the presence of any glutathione conjugates. Compound 19 was tested in triplicate along with the positive control diclofenac, a known GSH conjugator, which showed the expected conjugate masses.

Cellular assay

Hela cells were grown to 70% confluency in 24 well plates. The cells were incubated with compounds for 2 h at 37°C followed by the addition of 50 µCi/mL 3H-mannose and 5 µCi/ml 35S-Met/Cys trans label and further incubation at 37°C for 1 h. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and lysed in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4) containing 1% NP-40. The proteins were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid. 3H and 35S radiolabel were measured in precipitated proteins and the 3H:35S ratio was calculated. [3H]-Mannose incorporation in the glycoproteins of inhibitor treated cells were compared to cells without inhibitor (treated only with DMSO and having maximal PMI activity) which served as the negative control. No cell permeable positive control compound which increases mannose flux was available other than the new compounds tested in the present study.

In vivo Pharmacokinetics

C57BL/6 mice (n=3 per dose) were treated with 19 at doses of 5 mg/kg IV and 20 mg/kg PO. The mice were sacrificed and blood samples were collected at several time points (PO: 0.5 hr, 1 hr, 2 hr, 4 hr, and 6 hr; IV: 10 min, 0.5 hr, 1 hr, 2 hr, 4 hr, and 6 hr). Plasma was separated from the red cells by centrifugation and frozen at −20°C until assayed. 19 was extracted from the plasma samples using a 2-fold excess of acetonitrile, the extracts were vortexed for 3 min then centrifuged for 15 min (7500g) after which the supernatants were collected to be assayed by LCMS. Pharmacokinetic data were analyzed using Prism and Excel.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by NIH Grant HG003916, by The Rocket Williams Fund and by NIH Grants R01DK55615 and R21HD062914 to HHF, who is a Sanford Center Professor.

Abbreviations

- PMI

Phosphomannose Isomerase

- PMM2

Phosphomannomutase 2

- CDG

Congenital disorders of glycosylation

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- ADME

absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion

- PK

pharmacokinetic

- IV

intravenous

- p.o.

per os

- HK

hexokinase

- Man

mannose

- Man-6-P

mannose-6-phosphate

- Man-1-P

mannose-1-phosphate

- Fru-6-P

fructose-6-phosphate

- MLSMR

NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository

- PIFA

phenyliodine bis(trifluoroacetate)

- MLSCN

NIH Molecular Libraries Screening Center Network

- GSH

glutathione

- LCMS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

References

- 1.(a) Freeze HH. Towards a therapy for phosphomannomutase 2 deficiency, the defect in CDG-Ia patients. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1792:835–840. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jaeken J, Matthijs G. Congenital disorders of glycosylation: a rapidly expanding disease family. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:261–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Freeze HH. Genetic defects in the human glycome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:537–551. doi: 10.1038/nrg1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Eklund EA, Freeze HH. Essentials of glycosylation. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2005;12:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Eklund EA, Merbouh N, Ichikawa M, Nishikawa A, Clima JM, Dorman JA, Norberg T, Freeze HH. Hydrophobic Man-1-P derivatives correct abnormal glycosylation in Type I congenital disorder of glycosylation fibroblasts. Glycobiology. 2005;15:1084–1093. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Freeze HH, Sharma V. Metabolic manipulation of glycosylation disorders in humans and animal models. Semin Cell. Dev. Biol. 2010;21:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fujita N, Tamura A, Higashidani A, Tonozuka T, Freeze HH, Nishikawa A. The relative contribution of mannose salvage pathways to glycosylation in PMI-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblast cells. FEBS J. 2008;275:788–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Niehues R, Hasilik M, Alton G, Körner C, Schiebe-Sukumar M, Koch HG, Zimmer KP, Wu R, Harms E, Reiter K, von Figura K, Freeze HH, Harms HK, Marquardt T. Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type Ib. Phosphomannose isomerase deficiency and mannose therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1414–1420. doi: 10.1172/JCI2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Foret J, de Courcy B, Gresh N, Piquemal JP, Salmon L. Synthesis and evaluation of non-hydrolyzable D-mannose 6-phosphate surrogates reveal 6-deoxy-6-dicarboxymethyl-D-mannose as a new strong inhibitor of phosphomannose isomerases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:7100–7107. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bhandari A, Jones DG, Schullek JR, Vo K, Schunk CA, Tamanaha LL, Chen D, Yuan Z, Needels MC, Gallop MA. Exploring structure-activity relationships around the phosphomannose isomerase inhibitor AF14049 via combinatorial synthesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998;8:2303–2308. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Roux C, Lee JH, Jeffery CJ, Salmon L. Inhibition of Type I and Type II Phosphomannose Isomerases by the Reaction Intermediate Analogue 5-Phospho-DArabinonohydroxamic Acid Supports a Catalytic Role for the Metal Cofactor. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2926–2934. doi: 10.1021/bi035688h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correa A, Tellitu I, Domínguez E, SanMartin R. Novel alternative for the N-S bond formation and its application to the synthesis of benzisothiazol-3-ones. Org Lett. 2006;8:4811–4813. doi: 10.1021/ol061867q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klapars A, Huang X, Buchwald SL. A general and efficient copper catalyst for the amidation of aryl halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7421–7428. doi: 10.1021/ja0260465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipinski CA. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2000;44:235–249. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(00)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kansy M, Senner F, Gubernator K. Physicochemical high throughput screening: parallel artificial membrane permeation assay in the description of passive absorption processes. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:1007–1010. doi: 10.1021/jm970530e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baillie TA, Davis MR. Mass spectrometry in the analysis of glutathione conjugates. Biol. Mass Spectrom. 1993;22:319–325. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200220602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]