Abstract

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) undergo autoxidation and generate reactive carbonyl compounds that are toxic to cells and associated with apoptotic cell death, age-related neurodegenerative diseases, and atherosclerosis. PUFA autoxidation is initiated by the abstraction of bis-allylic hydrogen atoms. Replacement of the bis-allylic hydrogen atoms with deuterium atoms (termed site-specific isotope-reinforcement) arrests PUFA autoxidation due to the isotope effect. Kinetic competition experiments show that the kinetic isotope effect for the propagation rate constant of Lin autoxidation compared to that of 11,11-D2-Lin is 12.8 ± 0.6. We investigate the effects of different isotope-reinforced PUFAs and natural PUFAs on the viability of coenzyme Q-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae coq mutants and wild-type yeast subjected to copper stress. Cells treated with a C11-BODIPY fluorescent probe to monitor lipid oxidation products show that lipid peroxidation precedes the loss of viability due to H-PUFA toxicity. We show that replacement of just one bis-allylic hydrogen atom with deuterium is sufficient to arrest lipid autoxidation. In contrast, PUFAs reinforced with two deuterium atoms at mono-allylic sites remain susceptible to autoxidation. Surprisingly, yeast treated with a mixture of approximately 20%:80% isotope-reinforced D-PUFA: natural H-PUFA are protected from lipid autoxidation-mediated cell killing. The findings reported here show that inclusion of only a small fraction of PUFAs deuterated at the bis-allylic sites is sufficient to profoundly inhibit the chain reaction of non-deuterated PUFAs in yeast.

Keywords: C11-BODIPY, chain reaction, coenzyme Q, kinetic isotope effect, lipid autoxidation, oxidative stress, polyunsaturated fatty acid, ubiquinone

Introduction

PUFAs1 are essential nutrients and are avidly taken up by cells [1]. As components of phospholipids, PUFAs are key building blocks of membrane bilayers; they facilitate the assembly and stability of protein complexes, and play major roles in cellular metabolism [2]. PUFAs can be metabolized into several major classes of hormones by oxidative enzymes, including cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases, and epoxygenases, generating prostaglandins, hydroxyl-fatty acids, leukotrienes and other mediators collectively known as eicosanoids [3, 4].

PUFAs comprise the most vulnerable components of cells and are highly susceptible to non-enzymatic oxidation by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [5, 6]. ROS initiate the free radical chain reaction of PUFA autoxidation, resulting in changes in membrane permeability and fluidity due to accumulation of lipid peroxides [7] and cis to trans isomerisation [8]. The lipid peroxides resulting from PUFAs autoxidation may play a role in DNA damage [9] and carcinogenesis [10]. Because of their ability to generate oxyradicals, lipid peroxides may initiate degenerative processes and promote disorders, including inflammation [11] and cancer [12]. A separate class of non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation products comprises arachidonic acid-derived isoprostanes, which play a role in cellular signalling [13]; and PUFA-derived resolvins and protectins, which act as lipid mediators to resolve inflammation [14]. Oxidative damage to PUFAs also leads to a smorgasbord of reactive carbonyl electrophiles including products such as trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, trans,trans-2,4-decadienal, malondialdehyde, crotonaldehyde, 4-hydroxyhexenal, acrolein, and others [15–17]. These carbonyl electrophiles cause harm by reacting with cellular components such as proteins and nucleic acids [16, 18, 19]. The majority of cellular electrophiles are generated from PUFAs by a peroxidation chain reaction that is readily triggered by ROS, but propagates without their further input. Thus, the formation of lipid-derived electrophiles such as trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal is relatively insensitive to the level of initiating ROS, but depends mainly on the availability of PUFAs and O2. This is consistent with observations that life span is inversely correlated to membrane peroxidizability [20].

We have demonstrated that PUFAs harboring deuterium atoms at the bis-allylic sites are much more resistant to autoxidation reactions [21]. This is due to the isotope effect, whereby abstraction of the bis-allylic H atom, the rate-limiting step of PUFA autoxidation, is substantially slowed down by the presence of the D atoms at the bis-allylic site. Isotope-reinforced PUFAs were shown to protect coenzyme Q-deficient (coq) mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and heat-stressed wild-type yeast against the toxic effects of lipid autoxidation products [21]. Isotope-reinforced PUFAs are not diluted by endogenous PUFAs in yeast, because yeast synthesize only saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids and do not require PUFAs as essential nutrients [22]. Thus, PUFAs content can be readily manipulated, and isotope-reinforced PUFAs can provide the sole source of PUFAs in the yeast cell.

However, PUFAs are essential components of animal cells, and the total replacement of essential PUFAs in animals with isotope-reinforced PUFAs is a daunting prospect. We report herein the kinetic isotope effect of autoxidation of 11,11-D2-Lin in solution. Inclusion of only a small fraction of PUFAs deuterated at the bis-allylic sites is sufficient to profoundly inhibit the chain reaction in non-deuterated PUFAs in yeast. The exogenously added D-PUFAs slow detrimental lipid autoxidation within live yeast cells, and are effective even when present at low ratios in cell lipids. The results suggest that it may be practical to ameliorate ROS-initiated PUFA damage with the isotope-reinforcement approach.

Experimental Procedures

Fatty acids

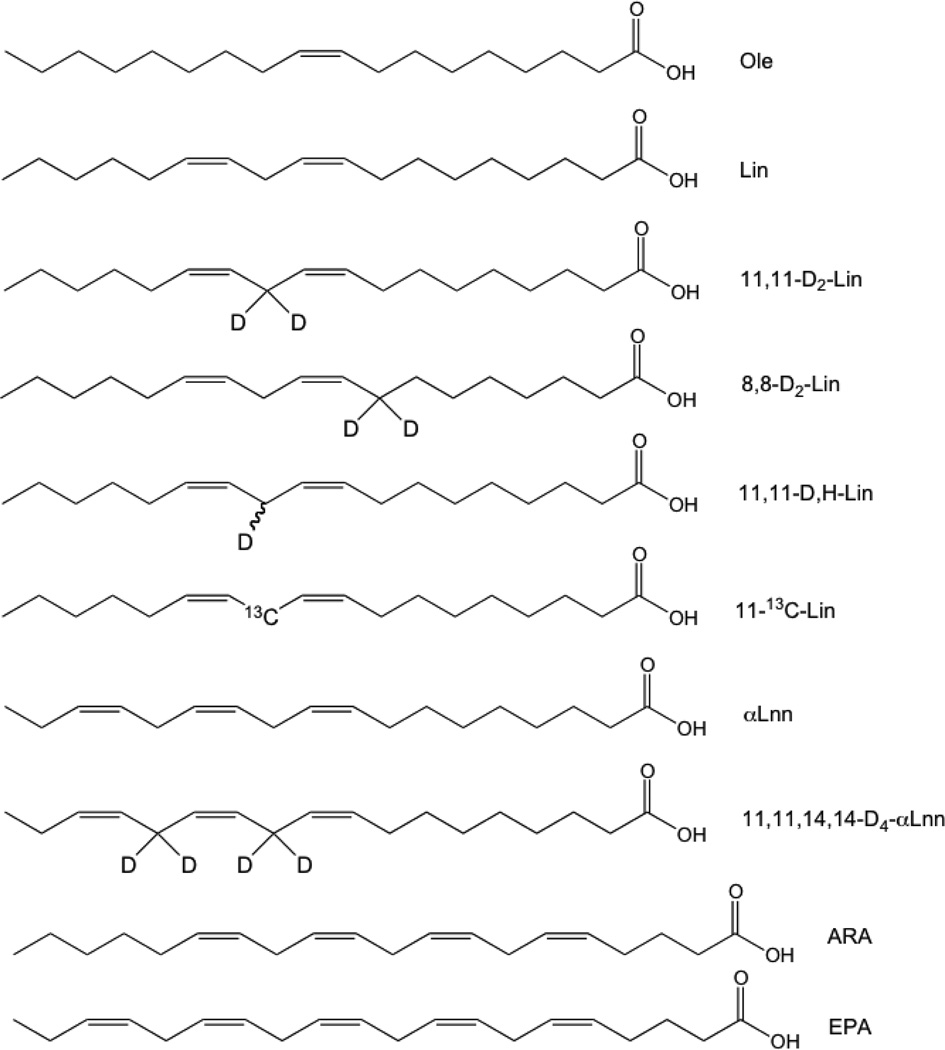

The fatty acids used in this study are shown in Fig. 1. Ole, Lin, and αLnn (99% pure) were from Sigma-Aldrich. The synthesis of 11,11-D2-Lin and 11,11,14,14-D4-αLnn was described previously [21]. The synthesis of 8,8-D2-Lin, 11,11-D,H-Lin, and 11-13C-Lin is described in Supplementary Material.

Figure 1. Structures of fatty acids used in this study.

Ole, oleic acid (18:1, cis-9-octadecenoic acid); Lin, linoleic acid (18:2, cis,cis-9,12-octadecenoic acid); 11,11-D2-Lin (11,11-D2-18:2; 11,11-D2-cis,cis-9,12-octadecenoic acid); 8,8-D2-Lin (8,8-D2-18:2; 8,8-D2-cis,cis-9,12-octadecenoic acid); 11,11-D,H-Lin (11,11-D,H-18:2; 11,11-D,H-cis,cis-9,12-octadecenoic acid); 11-13C-Lin (11-13C-18:2; 11-13C-cis,cis-9,12-octadecenoic acid); αLnn, linolenic acid (18:3, cis,cis,cis-9,12,15-octadecenoic acid); 11,11,14,14-D4-αLnn (D4-18:3; 11,11,14,14-D4-cis,cis,cis-9,12,15-octadecenoic acid).

Radical clock and co-oxidation experiments

Determination of rate constants for peroxidation of Lin and D2-Lin were performed as previously described [23, 24]. PUFAs were purified by flash column chromatography (10% EtOAc in hexanes to 20% EtOAc in hexanes) and dried overnight on vacuum. A stock solution of 0.1 M 2,2’-azobis(4-methoxy-2,4-dimethyl)valeronitrile (MeOAMVN) in benzene was used to initiate all reactions. Standards used in analysis were 4-methoxybenzyl alcohol (HPLC-UV) and D4-13-trans,cis-HODE (HPLC-MS). In all clocking or competition experiments, reagents were added in the order of: 1) benzene, 2) Lin/11,11-D2-Lin (ethyl esters or free acids), 3) MeOAMVN. Reaction vials were vortexed for 5 seconds, and then heated at 37 °C for one hour. Each reaction was quenched by addition of 25 µL of both 0.5 M BHT (to quench radicals) and 0.5 M PPh3 (to reduce hydroperoxide to alcohol). All experiments were carried out in triplicates.

In clocking experiments, Lin or 11,11-D2-Lin ethyl esters were used and the oxidation products, HODEs, were analyzed by normal phase HPLC-UV (250 × 4.6 mm silica column; 5 µm; elution solvent: 0.5% 2-propanol in hexanes; monitoring wavelength: 234 nm). The residual amount of 11-D1-Lin and D0-Lin in the 11,11-D2-Lin starting material was determined to be 2.9 and 0.8 mole %, respectively, from 1H NMR analysis and these values were used to correct the data from 11,11-D2-Lin assuming that 11-D1-Lin is half as reactive as D0-Lin.

In competition experiments, the total amount of Lin free acids (Lin + 11,11-D2-Lin) in each experiment was held constant at 0.64 M. After the reaction was quenched by addition of BHT and PPh3 (vide supra), 4-methoxybenzyl alcohol was added as an internal standard for HPLC-UV analysis and each reaction was divided into two parts. One part was analyzed by HPLC-UV for quantification of total HODEs formed in each reaction (250 × 4.6 mm silica column; 5 µm; elution solvent: 1.4% 2-propanol and 0.1% acetic acid in hexanes; monitoring wavelength: 234 nm). The other part was analyzed by HPLC-MS using D4-13-trans,cis-HODE as the internal standard (150 × 4.6 mm silica column; 3 µm; elution solvent: 1.4% 2-propanol and 0.1% acetic acid in hexanes) with selective reaction monitoring [24, 25]. Among these HPLC-MS analyses, the reactions that have large D2-Lin:Lin ratio (>5:1) were used to calculate the KIE by comparing the total D0-HODEs vs. total D1-HODEs. Note that D1-HODEs formed from 11-D1-Lin and isotopic contribution from D0-HODE were taken into consideration when calculating the actual amount of D1-HODEs that were formed from 11,11-D2-Lin. Specifically, the percentage of 11-D1-Lin in the 11,11-D2-Lin starting material, 2.9 mole % (vide supra), was used to correct the D1-HODEs formed from D1-Lin assuming that 11-D1-Lin is half as reactive as D0-Lin in solution. The isotopic contribution to the D1-HODEs from D0-HODEs was determined by running the same HPLC-MS analysis on the autoxidation of pure D0-Lin.

KODEs (corresponding ketones from HODEs) were also analysed [25] in reactions with D2-Lin: Lin ratios varying from 0 to 9. After HPLC-UV analysis was complete for each co-oxidation, solvent was removed from each vial. The resulting oil was dissolved in CDCl3 for 1H-NMR analysis to determine the true ratio of D2-Lin: Lin in each sample (excluding vials which were exclusively Lin) by comparing the integration of the vinyl protons and the bis-allylic protons.

Yeast strains and growth media

Yeast strains used in this study included wild-type, W303-1B (Mat α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2–3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1) [26], W303ΔCOR1 (Mat α ade2-1 his3-11, 15 leu2–3, 112 ura3-1 trp-1 can1-110 cor1::HIS3) [26], CC303.1 (Mat α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu 2–3, 112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq3::LEU2) [27], and W303Δcoq9 (Mat α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2–3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 coq9::URA3) [28]. Yeast growth media were prepared as described [29] and included YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% yeast peptone, 2% dextrose). Solid plate medium contained 2% Bacto agar. Components for growth media were obtained from Difco, Fisher, and Sigma.

Fatty acid sensitivity assays

Fatty acid sensitivity assays were performed as described [21]. Yeast were inoculated overnight in 5 ml YPD with aeration (250 rpm at 30 °C). Yeast cells were diluted to 0.2 OD/ml in YPD media and were grown to mid-log phase (0.2–1.0 OD600). Yeast cells were harvested at mid-log phase and collected by centrifugation (5 min at 1,000 × g) followed by two washes with sterile water. Yeast cells were diluted to 0.2 OD/ml in 0.10 M phosphate buffer (0.2% dextrose, pH 6.2). Aliquots (5 ml) were placed in overnight tubes and treated with the designated fatty acid and incubated at 30 °C with aeration (250 rpm). Aliquots were removed at the designated times and viability was assessed by spotting 2 µl of 1:5 serial dilutions (starting at 0.20 OD/ml) onto YPD plate medium. Pictures were taken after two days of growth at 30 °C.

Yeast cell lipid peroxidation assay

Yeast cells were subjected to treatment with fatty acids as described above and the assay of lipid peroxidation was performed as described [30], with the following modifications. Aliquots (10 ml) were removed from incubator (250 rpm at 30 °C) at the designated time and cells were washed twice with sterile water to remove excess fatty acids. Cells (2.0 OD600) were resuspended in 1 ml 0.10 M phosphate buffer (0.2% dextrose, pH 6.2) and treated with 4 µl of an ethanolic stock of 2 mM C11-BODIPY(581/591) (Molecular Probes) for 30 min at room temperature with shaking on a flat surface. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 sec, washed and resuspended in 1 ml 0.10 M phosphate buffer (0.2% dextrose, pH 6.2). For assays performed in wild-type cells, lipid peroxidation was induced with 50 µM CuSO4 at room temperature. Aliquots (100 µl) were placed into a black, flat-bottomed 96-well plate in quadruplicates and the OD595 was measured. Fluorescence was measured with a 485 nm excitation and a 520 nm emission filter in a Perkin Elmer, 1420 Multi label Counter and data was obtained with the Wallac workstation. Cells were visualized by fluorescent microscopy using excitation at 490 nm with a 520 nm emission filter. An aliquot of resuspended cells (9 µl) were placed on microscope slides (Fisher Scientific, 3” × 1” × 1mm) containing 1 µL of an ethanolic stock of 0.25 mg/ml DAPI (Molecular Probes). Microscope covers were pre-incubated with 30 µL of poly-L-lysine solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and were placed on microscope slides.

Fatty acid uptake and GC-MS detection of fatty acids

Fatty acid uptake and saponification, lipid extraction and alkaline methanolysis were performed as described [21]. GC-MS analyses of fatty acid methyl esters were performed as described [21], with the following modifications. Samples were subjected to analyses by GC-MS (Agilent 6890–6975) with a DB-wax column (0.25 mm inner diameter × 30 m length × 0.25-µm film thickness) (Agilent catalog number 122–7032). The temperature program was set to 100 °C for 1 min, 20 °C/min to 200 °C for 10 min, 15 °C/min to 250 °C, final temperature for 5 min and 1 µl was injected, with a split ratio of 1:10.

RESULTS

Synthesis of site specifically deuterated PUFAs

Isotope-reinforced Lin and αLnn containing two or four D at the bis-allylic sites (11,11-D2-Lin and 11,11,14,14-D4-αLnn; Figure 1) were synthesized as described previously [21]. Modifications of the published protocols [31, 32] were used to synthesize 8,8-D2-Lin, 11,11-D,H-Lin, and 11-13C-Lin (Fig. 1) as described in Supplemental Materials. The structures and purity of deuterated PUFAs were confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR (Supplemental Materials).

Kinetic measurements reveal a large KIE for the chain reaction of Lin autoxidation

Autoxidation of Lin is known to occur by a chain reaction process described by the following equations [6]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

We utilized MeOAMVN to initiate formation of two carbon-centered radicals (equations 1 and 2) that add oxygen at diffusion-controlled rates to generate two peroxyl radicals (equation 3). The rate of propagation of the chain reactions is determined by kp (equation 4). To determine the effect of the isotope reinforcement on the propagation rate constants of Lin autoxidation as compared to that of 11,11-D2-Lin, we performed parallel clocking experiments utilizing a linoleate peroxyl radical clock [6, 23, 24], as well as competition experiments by co-oxidizing 11,11-D2-Lin and Lin in solution.

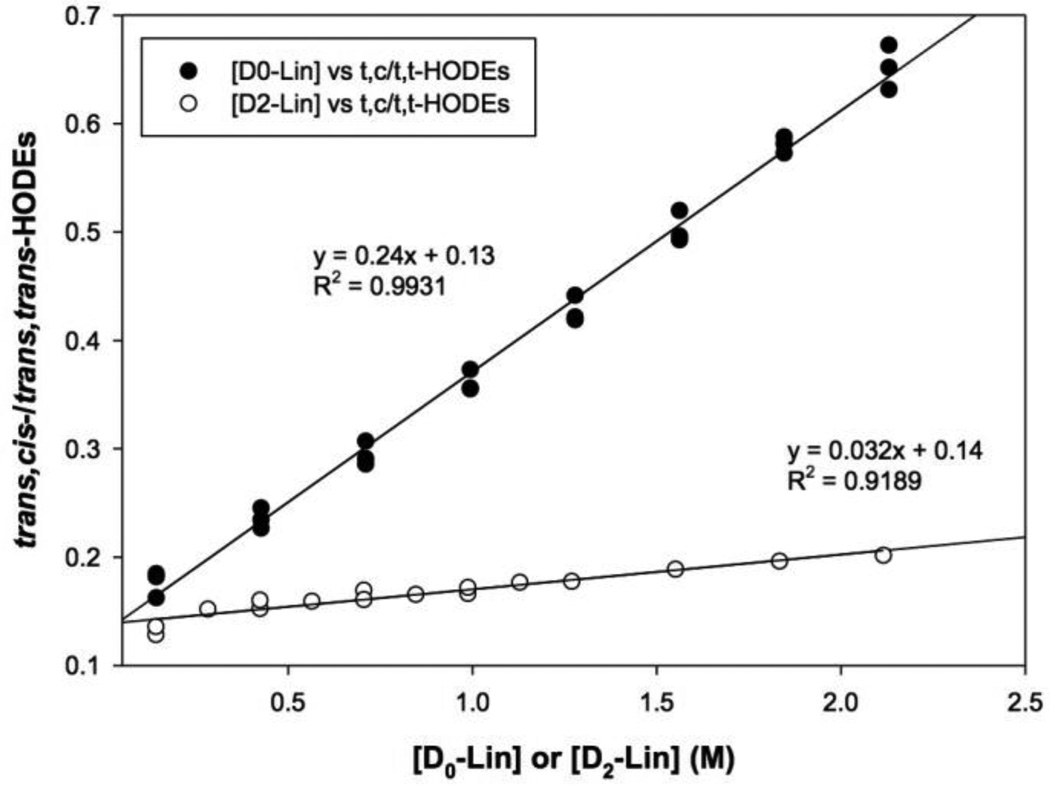

In clocking experiments, the concentrations of Lin or 11,11-D2-Lin ethyl esters were varied from 0.14 to 2.1 M. The ratios of trans,cis-HODEs to trans,trans-HODEs were plotted against the concentrations of Lin or 11,11-D2-Lin to obtain the slope that was used to calculate the KIE [23] (Fig. 2). The slopes obtained for the 11,11-D2-Lin clocking experiments were corrected based on the content of 11-D1-Lin and D0-Lin in the starting material assuming that 11-D1-Lin is half as reactive as D0-Lin in free radical chain oxidation. As the propagation rate constant is proportional to the slope of clocking plots [23] shown in Fig. 2, the KIE (i.e., ratio of the slopes for Lin and 11,11-D2-Lin) was thus found to be 9.3 ± 1.1 by the application of this method.

Figure 2. Clocking experiments on Lin and 11,11-D2-Lin ethyl esters.

Ratios of trans,cis-/trans,trans- HODEs versus concentration of ethyl linoleate (D0 or D2) were plotted. Oxidations were carried out at 37 °C in benzene for 1 h and initiated with MeOAMVN. HODE ethyl esters were analyzed by HPLC-UV (250 × 4.6 mm silica column; 5 µm; elution solvent: 0.5% 2-propanol in hexanes; monitoring wavelength: 234 nm).

To further elucidate the kinetics and KIE of 11,11-D2-Lin autoxidation, competition experiments (co-oxidation of Lin and 11,11-D2-Lin) were carried out. A typical chromatogram of HODE free acids is shown in Fig. 3A. The order of elution is as follows: 13-t,c-HODE (t = 9.5 min.), 13-t,t-HODE (t = 14 min.), 9-t,c-HODE (t = 16.5 min), 9-t,t-HODE (t = 18.5 min.), 4-methoxybenzyl alcohol (t =20.5 min.). The same mobile phase is used for HPLC-MS analyses, and the same order of elution is observed as shown in Fig. 3B, in which both D0-HODEs and D1-HODEs were analyzed.

Figure 3. In vitro kinetic studies of PUFA autoxidation.

(A) Typical chromatogram of HPLC-UV (250 × 4.6 mm silica column; 5 µm; elution solvent: 1.4% isopropanol, 0.1% acetic acid in hexanes; 1.0 mL/min; monitoring wavelength: 234 nm; analysis of D0-Lin: D2-Lin co-oxidation products. (B) Typical chromatogram from HPLC-MS analysis (150 × 4.6 mm silica column; 3 µm; elution solvent: 1.4% isopropanol, 0.1% acetic acid in hexanes; 1.0 mL/min) of D0-Lin: D2-Lin co-oxidation. The first two panels are monitoring for D0-fragmentation ions. The last two panels are monitoring for D1-fragmentation ions (which have a m/z value corresponding to a mono-deutero ion). (C) Total HODEs vs. percentage of 11,11-D2-Lin in co-oxidation experiments. Co-oxidation mixtures of D0-Lin and D2-Lin were analyzed by HPLC-UV as shown in panel A. Total amount of HODEs were quantified relative to the level of the internal standard, 4-methoxybenzyl alcohol, present in the sample.

By keeping the total concentration of (11,11-D2-Lin + Lin) constant and varying the ratio of 11,11-D2-Lin: Lin, a linear relationship was observed in co-oxidation experiments between the total amounts of HODEs formed and the percentage of D2-Lin (no turning point was observed), suggesting D2-Lin did not act as an antioxidant in the co-oxidation reactions and only acted as a less reactive co-oxidant in the autoxidations carried out in solution (Fig 3C).

The KIE was also measured by a direct competition method. When Lin and D2-Lin are co-oxidized, the ratios of the total HODEs formed from Lin (HODEs) and those from D2-Lin (D-HODEs) reflects the pseudo-first-order rate constant of the Lin and D2-Lin ([HODEs]/[D -HODEs] = kLin[D0-Lin]/kD2-Lin[D2-Lin]). Ratios of kLin/kD2-Lin can thus be calculated. Because D-HODEs formed from H,D-Lin (present in D2-Lin as determined by NMR) and isotopic peaks of HODEs will contribute to the D-HODEs signal, these contributions were subtracted from the total D-HODEs signals (see Materials and Methods). It is also important to note that the percentage of oxidation after one hour was measured to be approximately 2 % for pure Lin. Based on this it can be assumed that the percentage of oxidation in other samples with higher concentrations of D2-Lin will be lower than that for Lin (< 2%). The small oxidation extent suggests that the concentrations of Lin and D2-Lin did not change significantly during oxidation, a requirement for calculating the KIE. The average KIE value calculated from HPLC-MS data of co-oxidation experiments for samples with D2-Lin: Lin ratios greater than 5:1 was found to be 12.8 ± 0.6 (Table 1).

Table 1.

KIE of 11,11-D2-Lin oxidation obtained from co-oxidation of 11,11-D2-Lin and D0-Lin in solution.

| Run | D0 : D2 | D0-HODEs/D1-HODEs | KIE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 : 5.1 | 2.4 | 12.4 |

| 2 | 1 : 6.5 | 2.0 | 13.1 |

| 3 | 1 : 9.5 | 1.3 | 12.8 |

KODEs can be formed from the radical termination reaction. In the series of co-oxidation reactions carried out here with D2-Lin: Lin ratios varying from 0 to 9, KODEs were formed at very low levels (0.5–0.8% of the levels of HODEs), suggesting that, based on these products, the termination step was not affected significantly by the presence of D2-Lin in solution oxidation.

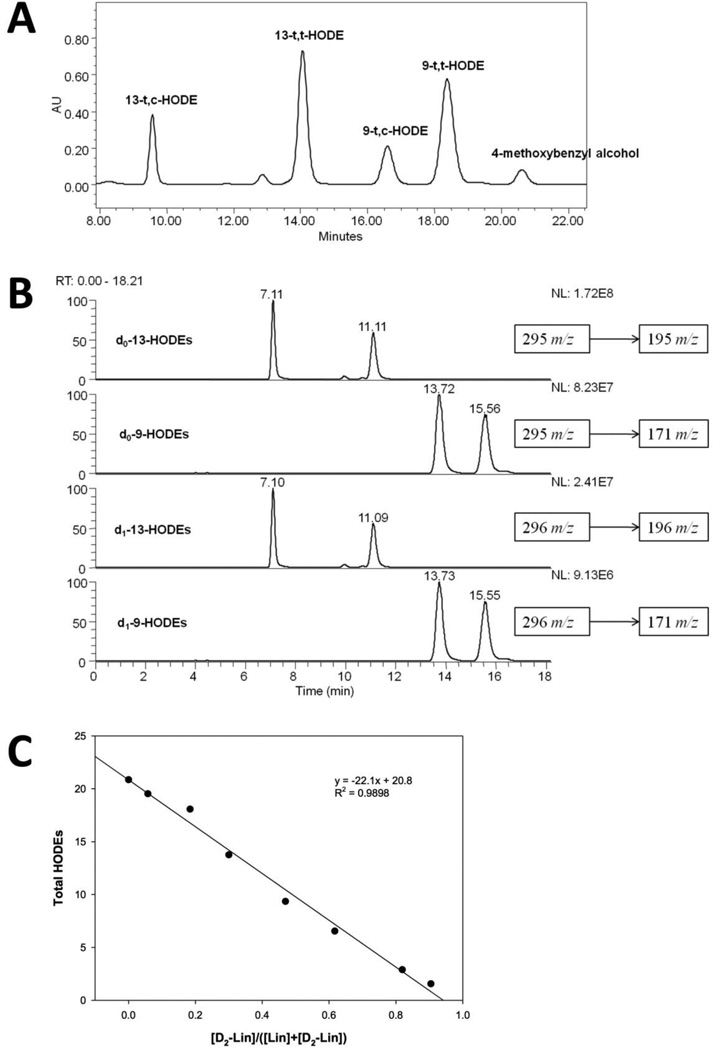

Isotope reinforcement at the bis-allylic position of PUFAs is required to protect Q-less yeast against lipid autoxidation

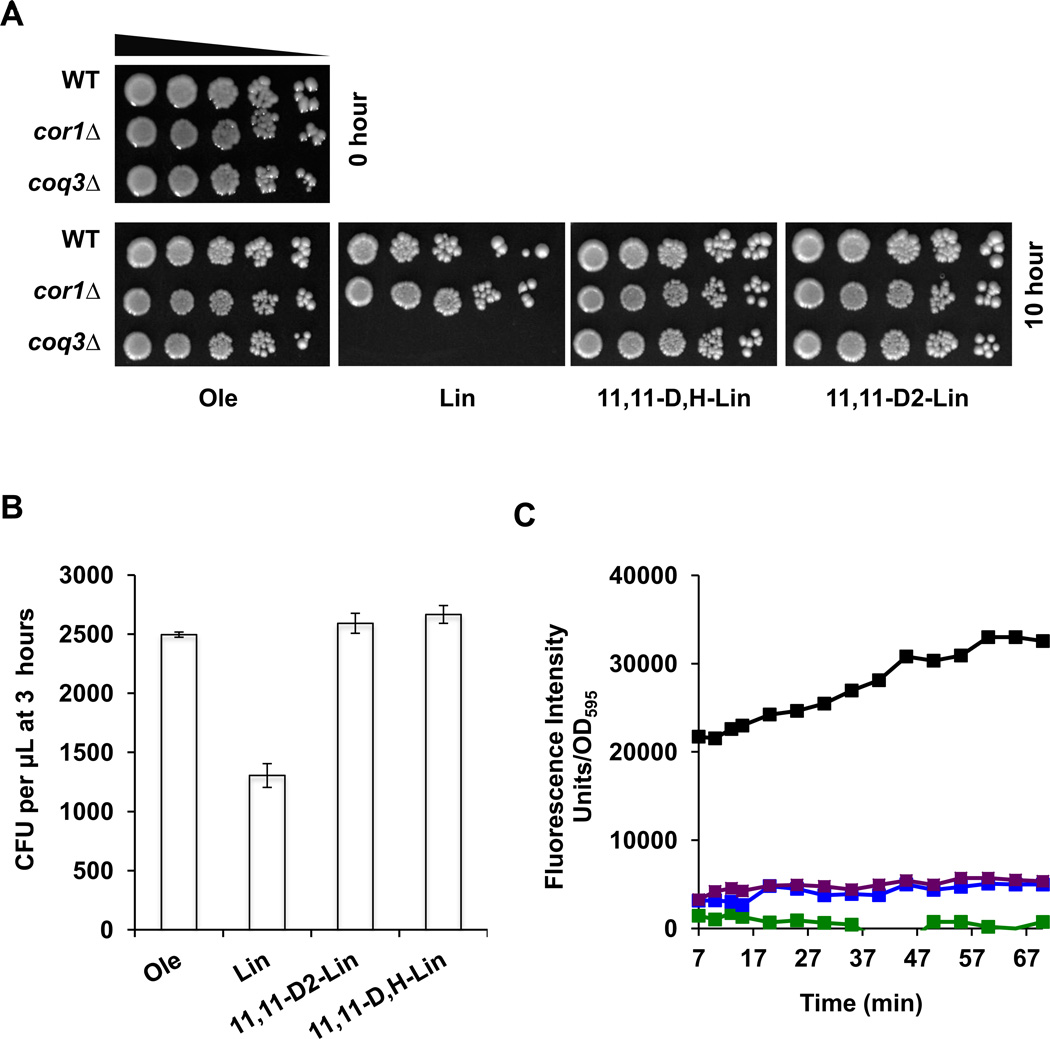

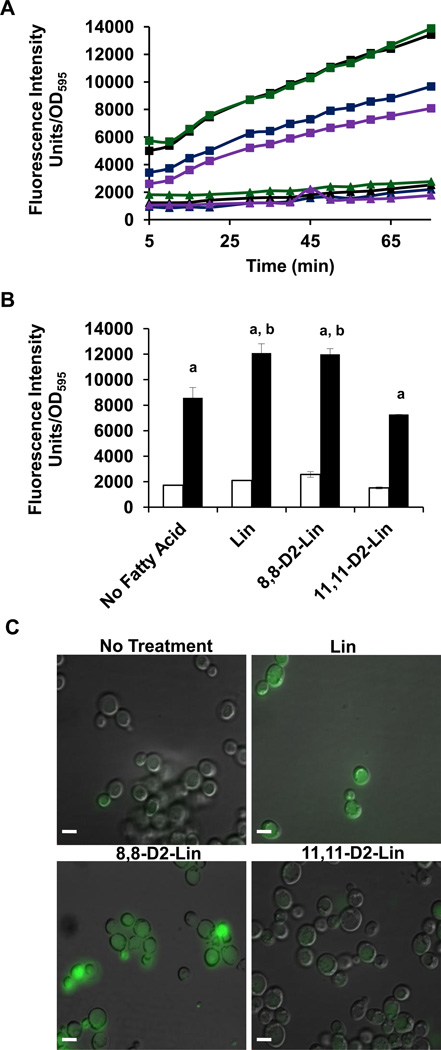

Previous studies have shown that Q-less yeast coq mutants are exquisitely sensitive to PUFA treatment [27] and can be rescued by isotope-reinforced PUFAs [21]. Here we show that site-specific reinforcement at the bis-allylic position is essential for this protection, since treatment with mono-allylic 8,8-D2-Lin failed to protect Q-less yeast (Fig. 4A). The sensitivity of the yeast coq3 null mutant to PUFA treatment is not due to the inability to respire since the respiratory deficient cor1 null mutant lacking complex III does not show sensitivity to PUFA treatment.

Figure 4. Isotope reinforcement at the bis-allylic position of polyunsaturated fatty acids is required for protection against lipid autoxidation.

(A) Wild-type, yeast Q-less coq3, or respiratory deficient cor1 null mutants were harvested during mid-log phase growth (0.2–1.0 OD600). Yeast cells were washed twice with sterile water and diluted to 0.2 OD600 in phosphate buffer. Yeast cells were treated with 200 µM of the designated fatty acid. Serial dilutions (1:5) starting at 0.2 OD/ml were spotted on YPD solid plate medium. A zero-time untreated control is shown on the top left. Pictures were taken after 2 days of growth at 30 °C. (B) Yeast coq3 null mutant cells were treated with the designated fatty acid for 2 hours and three 100 µl aliquots were removed and spread onto YPD plate medium after dilution. The chart shows the number of colony forming units (CFU) per µl after 2 hours of PUFA treatment. There was no significant difference between CFU of different treatments. (C) After 2 hours of PUFA treatment coq3 null mutant cells were treated with 8 µM C11-BODIPY 581/591 for 30 min at room temperature. Four 100 µl aliquots were plated in a 96-well plate and the fluorescence was measured by fluorimetry with a 485 nm excitation and a 520 nm emission filter using a Perkin Elmer, 1420 Multilabel counter, Victor3 in 5 min increments following 30 min of C11-BODIPY 581/591 treatment. Fatty acid treatments include: no treatment, blue; Lin, black; 8,8-D2-Lin, green; 11,11-D2-Lin, purple. (D) Lipid peroxidation in cells treated with the designated fatty acid was examined as described in (C) except cells were visualized by fluorescent microscopy using excitation at 490 nm with a 520 nm emission filter within 45 min after C11BODIPY 581/591 treatment. Lipid peroxidation was visualized by an Olympus IX70 fluorescence microscope with 100X oil objective and a 490 nm excitation and a 520 nm emission filter (FITC). (Scale bar= 6.6 µm).

A lipophilic dye, C11-BODIPY(581/591) was used to monitor lipid peroxidation in the coq3 null mutant yeast cells treated with PUFAs. This C11-BODIPY(581/591) probe is a fluorescent fatty acid analogue used as an indicator of lipid peroxidation and antioxidant efficacy in membrane systems and living cells [33]. Upon oxidation of C11-BODIPY(581/591) there is a fluorescent shift from red to green [33]. Yeast cells were treated with PUFAs for 2 h, and then treated with C11-BODIPY(581/591) for 30 min. Following 2 h of PUFA treatment, the yeast coq3 mutant cells are still viable as determined by the number of colony forming units present (Fig. 4B). Lipid peroxidation in the yeast coq3 null mutant cells was monitored with a multi-well fluorescent microplate reader and by fluorescent microscopy. The yeast coq3 null mutants treated with Lin or mono-allylic 8,8-D2-Lin have much higher levels of lipid peroxidation as compared to either untreated cells or cells treated with bis-allylic 11,11-D2-Lin (Fig. 4C and 4D). As shown in Figure 4, lipid peroxidation resulting from treatment with Lin or 8,8-D2-Lin is evident after 2 h as detected with the C11-BODIPY probe and precedes cell death.

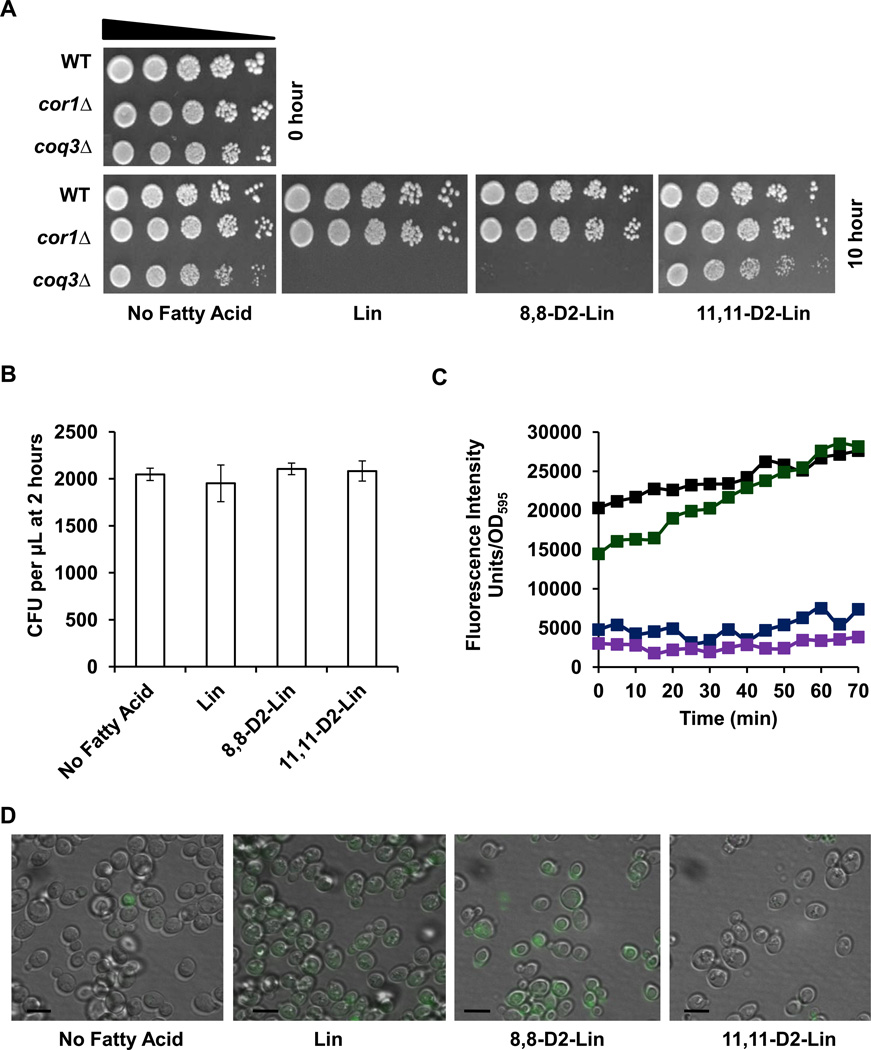

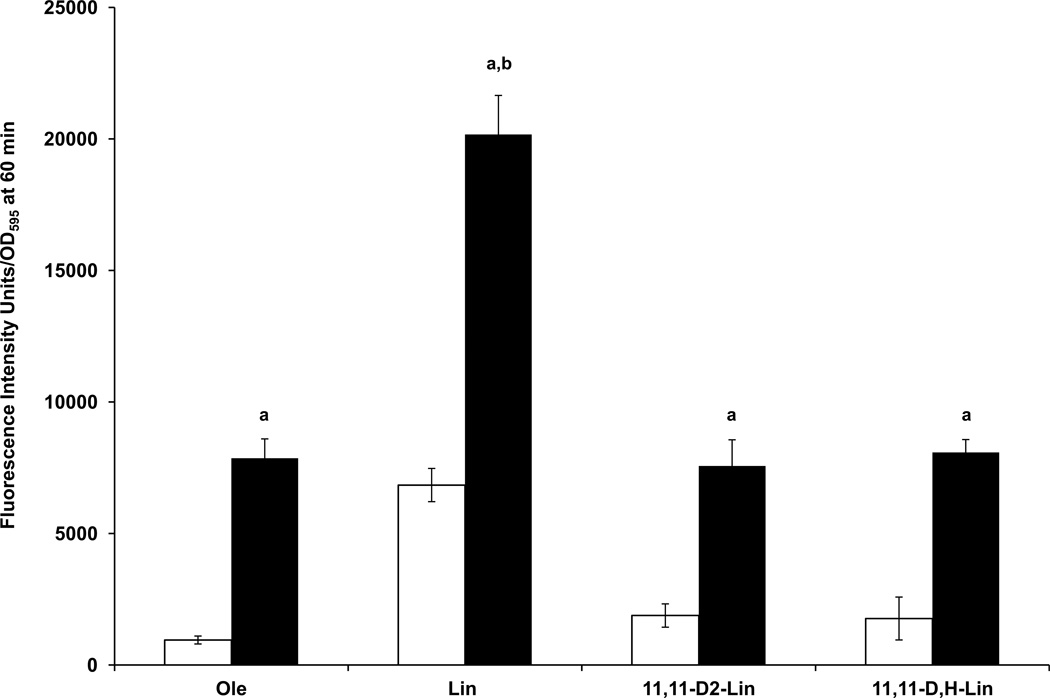

Q-less yeast are protected by mono-deuterated isotope-reinforced PUFA

We wished to investigate further the dramatic protection afforded by the site-specific deuteration of the bis-allylic H atoms of PUFAs. We reasoned that if the resistance to autoxidation was attributed primarily to the rate-limiting abstraction of a H atom from the bis-allylic site, then a “half-deuterated” Lin (11,11-D,H-Lin) would be expected to lose most of its protective effect. Surprisingly, treatment with the mono-deuterated Lin afforded the same degree of protection to the Q-less coq3 yeast mutant as the 11,11-D2-Lin (Fig. 5A). A shorter treatment with Lin (3 hours) resulted in a 50% loss of cell viability in the yeast coq3 mutant (Fig. 5B). In contrast, no loss in cell viability was detectable after 3 hours of treatment with either mono-deuterated Lin, or 11,11-D2-Lin. Yeast coq3 mutant cells treated with either mono-deuterated Lin or the 11,11-D2-Lin were resistant to lipid peroxidation, as monitored with the C11-BODIPY(581/591) probe (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Yeast coq3 null mutants treated with mono-deuterated 11,11-D,H-Lin are resistant to PUFA-induced sensitivity.

(A) Fatty acid sensitivity assays were performed as described in Figure 4, except yeast cells were treated with 200 µM of the designated fatty acid for 10 h. A zero-time untreated control is shown in the top left. Pictures were taken after 2 days of growth at 30 °C. (B) Coq3 null mutant cells were treated with the designated fatty acid for 3 hours and three 100 µl aliquots were removed and spread onto YPD plates after dilution. The chart shows the number of colony forming units (CFU) per µl after 3 hours of PUFA treatment. (C) After 3 hours of PUFA treatment coq3 null mutant cells were treated with 8 µM C11-Bodipy 581/591 for 30 min at room temperature. Four 100 µl aliquots were plated in a 96-well plate and the fluorescence was measured as described in Fig 4C. Fatty acid treatments include: Ole, green; Lin, black; 11,11-D,H-Lin, purple; 11,11-D2-Lin, blue.

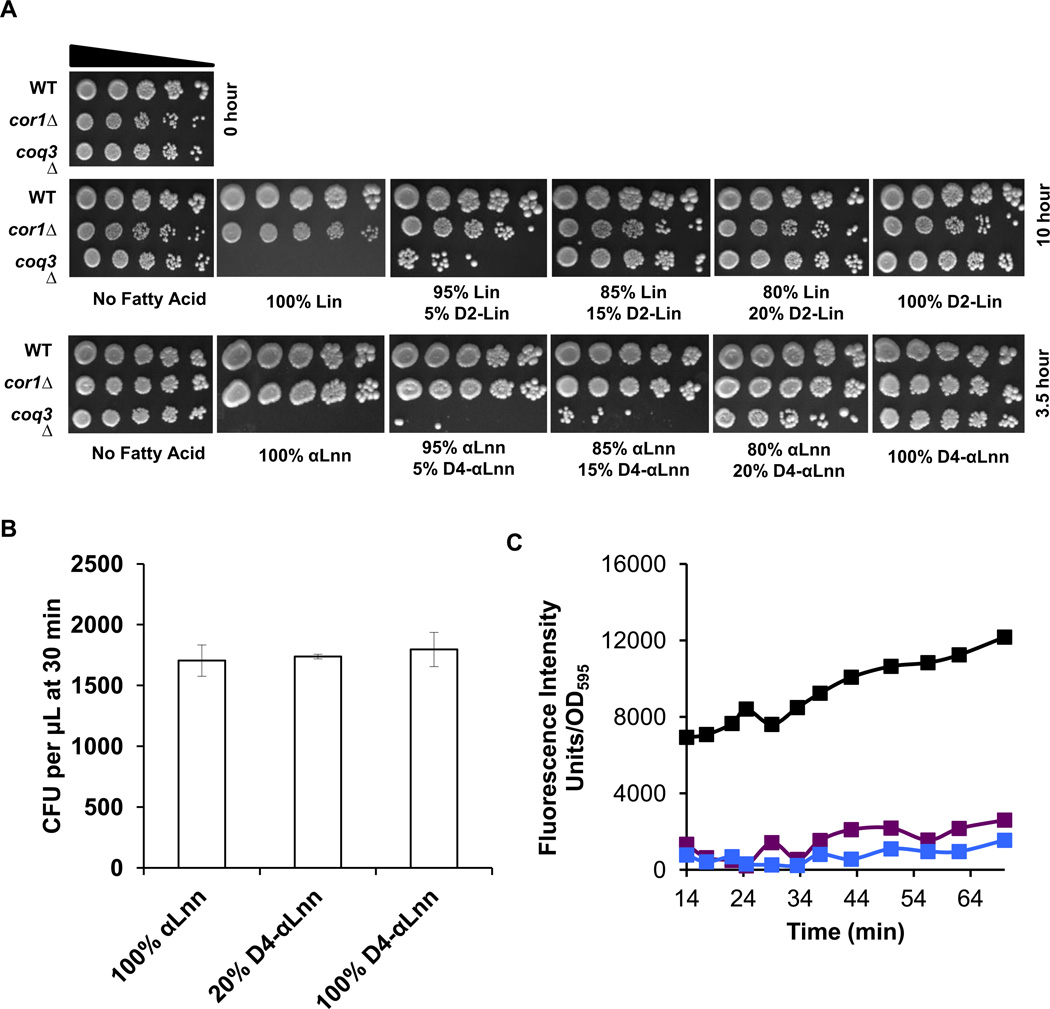

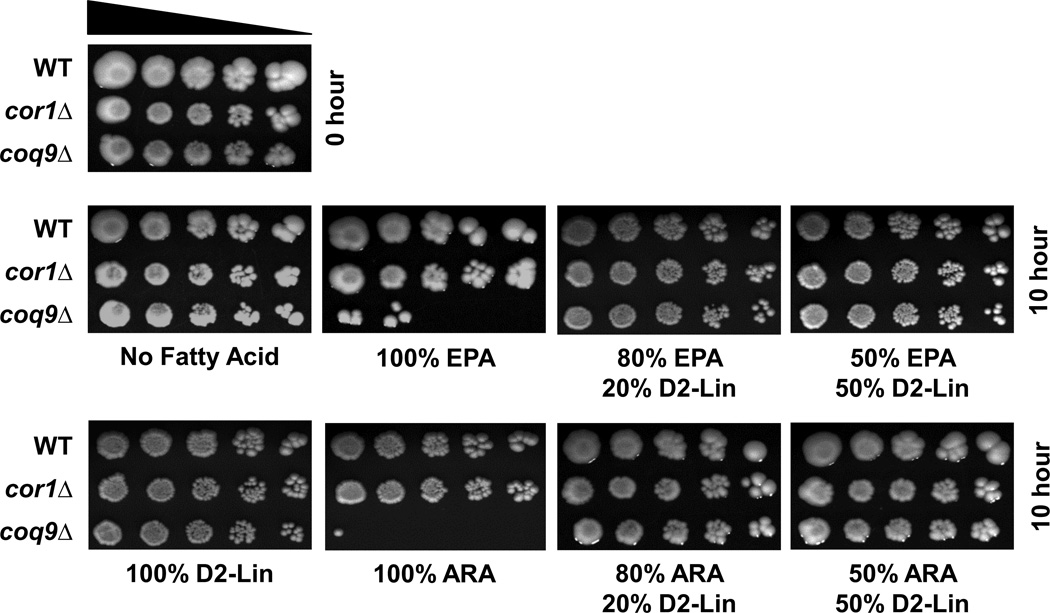

Q-less yeast are protected by small amounts of isotope-reinforced PUFA

Our previous study showed that isotope-reinforcement of only one of the two bis-allylic sites present in linolenic acid (11,11-D2-αLnn or 14,14-D2-αLnn) provided a similar degree of protection against PUFA sensitivity as compared to the fully reinforced 11,11,14,14-D4-αLnn [21]. These results, together with the protection afforded by the mono-deuterated 11,11-D,H-Lin (Fig. 5), suggested that mixtures containing isotope-reinforced PUFA together with natural PUFA may mimic the robust protection afforded by partial isotope reinforcement. To test the effect of PUFA mixtures in the yeast cell model, we subjected yeast to PUFA treatments containing only a small proportion of isotope-reinforced PUFAs. As shown in Fig. 6A, PUFA mixtures containing as little as 20% of isotope-reinforced PUFAs afforded dramatic protection, as shown by the viability of the coq3 Q-less yeast following serial dilution and plating onto rich growth medium. Although treatment for 30 min with αLnn did not affect coq3 mutant cell viability (Fig. 6B), this brief treatment resulted in lipid peroxidation products as assayed with the C11-BODIPY(581/591) probe (Fig. 6C). In contrast, inclusion of only 20% 11,11,14,14-D4-αLnn inhibited the formation of lipid peroxidation products from the 80% αLnn present in the mixture (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Only a small fraction of isotope-reinforced PUFAs is required for rescue.

(A) Fatty acid sensitivity assays were performed as described in Figure 4 except that yeast were treated with 200 µM of the designated PUFA mixture (natural PUFA : isotope-reinforced PUFA) for either 3.5 or 10 hours. A zero-time untreated control is shown on the top left. Pictures were taken after 2 days of growth at 30 °C. (B) Yeast coq3 null mutant cells were treated with the designated fatty acid mixture for 30 min and three 100 µl aliquots were removed and spread onto YPD plates after dilution. The chart shows the number of colony forming units (CFU) per µl after 30 min of PUFA treatment. There was no significant difference between CFU of different treatments. (C) Yeast coq3 null mutant cells were treated with 8 µM C11-Bodipy 581/591 for 30 min at room temperature. Four 100 µl aliquots were plated in a 96-well plate and the fluorescence was measured as described in Figure 4C. Fatty acid treatments include: 100% αLnn, black; 20% D4-αLnn, purple; 100% D4-αLnn, light blue.

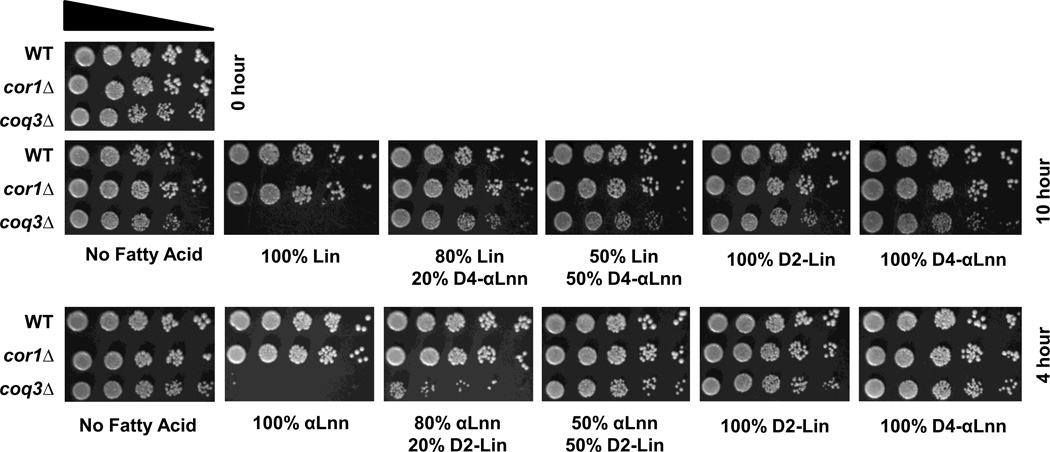

A small fraction of either type of reinforced PUFA afforded “cross-over” protection as shown by the efficacy of 11,11-D2-Lin to protect against αLnn treatment, or 11,11,14,14-D4-αLnn to protect against Lin treatment (Fig. 7). Yeast cells do not appear to discriminate among the PUFAs provided, since the content of PUFAs taken up by yeast cells roughly reflects the ratios added (Table 2). The results of these studies suggest that the dramatic protection afforded by small amounts of isotope-reinforced PUFAs are likely to derive from the multi-step process of lipid autoxidation, which serves to amplify even small kinetic isotope effects. Alternatively, it is possible that the D-PUFA• radical may have properties different from the standard H- PUFA• radical.

Figure 7. A small fraction of either D2-11,11-Lin or D4-11,11,14,14-αLnn is sufficient to rescue sensitivity of coq3 mutant yeast cells to either PUFA treatment.

Fatty acid sensitivity assays were performed as described in Figure 4 except that yeast were treated with 200 µM of the designated PUFA mixture (natural PUFA : isotope-reinforced PUFA) for either 4 or 10 hours. A zero-time untreated control is shown on the top left. Pictures were after taken 2 days of growth at 30 °C.

Table 2.

Relative fatty acid uptake of PUFA-fed wild-type yeast

| Relative Ratios of PUFA Uptakea | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ratios of PUFAs Added | αLnn | Lin | 11,11-D2-Lin |

| αLnn:Lin | 57 ± 2.3% | 43 ± 2.3% | 0% |

| αLnn:11,11- D2-Lin | 55 ± 1.5% | 0% | 45 ± 1.8% |

| Lin:11,11- D2-Lin | 0% | 44 ± 2.7% | 56 ± 2.7% |

| αLnn:Lin:11,11- D2-Lin | 40 ± 3.1% | 28 ± 0.7% | 32 ± 2.4% |

Relative ratios of PUFA uptake in wild-type cells after 4 hours of incubation with exogenously added PUFAs. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

The yeast coq3 null mutant is sensitive to a fatty acid mixture containing monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids

To determine whether the protection afforded by partial amounts of isotope-reinforced PUFA may simply reflect the decreased amount of vulnerable (natural) PUFA present in the mixing experiments, yeast coq3 mutants were treated with a 50:50 mixture of Ole: αLnn. Plate dilution assays revealed that after four hours of treatment there was a profound loss of yeast coq3 null mutant viability (Fig. 8A). Similarly, yeast coq9 mutants were sensitive when treated with a 50:50 mixture of Ole: Lin, but were protected upon treatment with 50:50 Lin: 11,11-D2-Lin (Fig. 8B). These results suggest that the isotope-reinforced PUFAs inhibit the process of lipid autoxidation and do not merely act to dilute the H-PUFAs susceptible to lipid autoxidation.

Figure 8. Yeast coq3 and coq9 null mutant cells are sensitive to a fatty acid mixture containing monounsaturated (Ole) and αLnn or Lin.

(A) Fatty acid sensitivity assays were performed as described in Figure 4 except that yeast were treated with 200 µM Ole or 100 µM of αLnn in the presence of 100 µM of the designated fatty acid for 4 hours. A zero-time untreated control is shown on the top left. Pictures were taken after 2 days of growth at 30 °C. (B) Fatty acid sensitivity assays were performed as described in Figure 4 except that yeast were treated with 300 µM Ole or 300 µM of Lin in the presence of 300 µM of the designated fatty acid for 10 hours. A zero-time untreated control is shown on the top left. Pictures were taken after 2 days of growth at 30 °C.

To investigate the protection afforded by the mono-deuterated 11,11-D,H-Lin, we reasoned that secondary isotope effects may govern the abstraction of the bis-allylic H atom adjacent to the D at position 11. Such small effects, when amplified over many chain reaction steps might be sufficient to slow the generation of toxic autoxidation products and preserve cell viability. The value of the primary KIE for abstraction of the bis-allylic H from 11-13C-Lin is roughly comparable to the secondary KIE for the H abstraction off the 11-CHD methylene group [34, 35]. However, we observed that yeast coq9 mutants were nearly as sensitive to treatment with 11-13C-Lin as they were to treatment with Lin (Fig. 8B). This result argues against the importance of small effects on the abstraction stage of the process as accounting for the protection afforded by the 11,11-D,H-Lin to inhibit the chain reaction. Instead, the presence of the D-Lin• radical may be important. Accordingly, we tested whether the 11,11-D,H-PUFA could cross-protect when mixed with Lin. As shown in Fig. 8B, although yeast coq9 mutants were resistant to treatment with mono-deuterated 11,11-D,H-Lin, the mutants remained sensitive when treated with a 50:50 mix of mono-deuterated 11,11-D,H-Lin:Lin. Taken together, these observations hint that both the abstraction step, and the presence of D in the radical system, are important for cross protection.

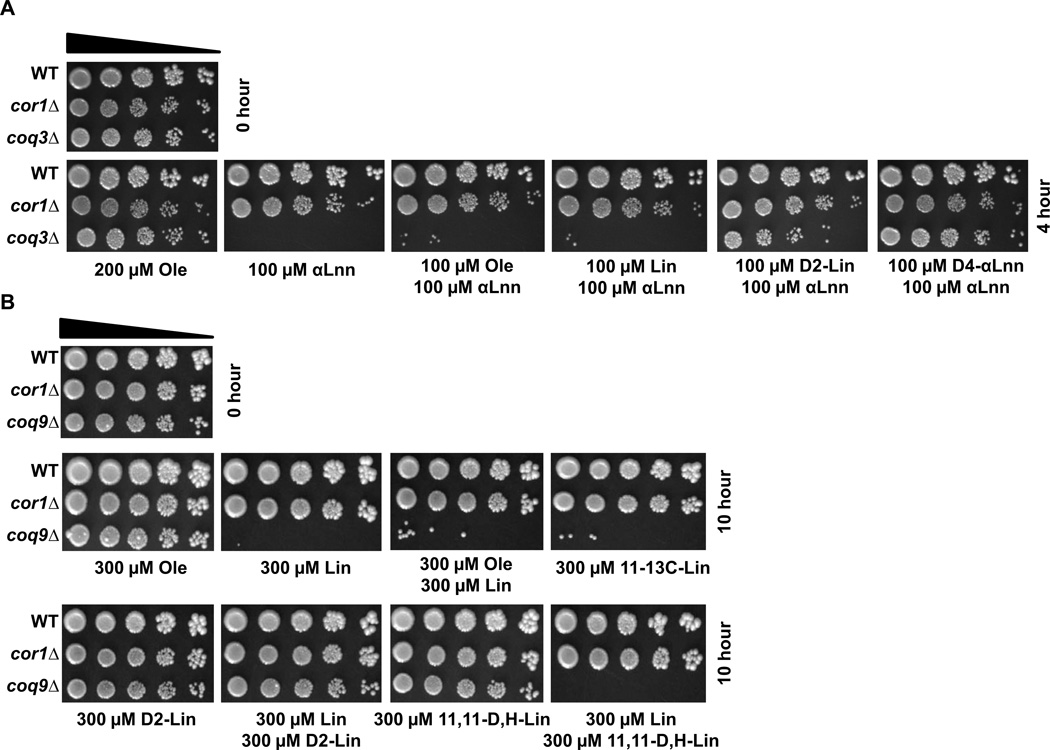

Copper-treated wild-type yeast treated with isotope-reinforced PUFAs have low levels of lipid peroxidation

We employed a model of copper-induced PUFA autoxidation previously developed by Avery et al., [36]. Wild-type yeast cells do not exhibit high levels of lipid peroxidation when treated with PUFAs. However, wild-type yeast cells treated with natural PUFAs and copper have increased levels of lipid peroxidation as compared to no addition of copper (Fig. 9A and 9B). We found that wild-type cells treated with either Lin or mono-allylic 8,8-D2-Lin failed to protect against lipid peroxidation induced by copper stress. In contrast, copper-stressed wild-type yeast cells treated with 11,11-D2-Lin have lower levels of lipid peroxidation similar to yeast not treated with PUFAs (Fig. 9). In this copper-stress yeast model, the mono-deuterated 11,11-D,H-Lin offers protection similar to the 11-11-D2-Lin (Fig. 10).

Figure 9. Isotope-reinforcement of Lin at the bis-allylic position protects copper-stressed wild-type cells from lipid peroxidation.

(A) Wild-type yeast cells were treated as described in Figure 4 except yeast were treated with 200 µM of the designated fatty acid for 2 hours, washed with sterile water, and were either not treated (triangles) or treated with 50 µM CuSO4 (squares) at room temperature. After 60 min of copper treatment cells were treated with 8 µM C11-Bodipy 581/591 for 30 min at room temperature. Four 100 µl aliquots were plated in a 96-well plate and the fluorescence was measured as described in Figure 4C. Fatty acid treatments include: no treatment, blue; Lin, black; 8,8-D2-Lin, green; or 11,11-D2-Lin, purple. (B) The chart shows the fluorescence intensity per OD595 at the 60 min time point shown in (A) and corresponds to no copper (white bars) or copper treatment (black bars). Wild-type yeast cells treated with copper in the absence or presence of PUFA have significantly higher levels of lipid peroxidation as compared to yeast not treated with copper; a, p<1.0E–4. Wild-type yeast cells treated with copper in the presence of Lin or 8,8-D2-Lin have significantly higher levels of lipid peroxidation as compared to yeast treated with copper in the absence of PUFA; b, p<1.0E–4. Differences in fluorescence signals were assessed with one-way ANOVA test followed by a Tukey comparison test (Stat View 5.0.1, SAS, CA). (C) Lipid peroxidation of the designated fatty acid was examined as described in Figure 4D except cells were visualized by fluorescent microscopy after 60 min of 50 µM CuSO4 treatment. (Scale bar = 5 µm).

Figure 10. Both mono- and di-deuterated Lin at the bis-allylic position protect copper-stressed wild-type cells from lipid peroxidation.

Wild-type cells were treated as described in Figure 4 except yeast were treated with the designated fatty acid for 3 hours, washed with sterile water, and treated with 8 µM C11-BODIPY 581/591 for 30 min at room temperature. Following BODIPY 581/591 treatment wild-type yeast were either not treated (white bars) or treated with 50 µM CuSO4 (black bars) at room temperature. The chart shows the fluorescence intensity per OD595 after 60 min of either no copper (white bars) or plus copper (black bars) treatment. Wild-type yeast treated with copper in the absence or presence of PUFAs have significantly higher levels of lipid peroxidation as compared to yeast not treated with copper; a, p<1.0E–4. Wild-type yeast treated with copper in the presence of Lin have significantly higher levels of lipid peroxidation as compared to yeast treated with copper in the presence of Ole; b, p < 1.0E–4. Differences in fluorescence signals were assessed with one-way ANOVA test followed by a Tukey comparison test (Stat View 5.0.1, SAS, CA).

Small amounts of isotope-reinforced PUFA protect yeast cells from long chain PUFAs stress

We tested the effect of small amounts of 11,11-D2-Lin on the stress imposed by a biologically important class of long chain PUFAs, including arachidonic acid (ARA, 20:4, n–6), and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5, n–3). As shown in Fig. 11, Q-less yeast were sensitive to treatment with either ARA or EPA long chain PUFAs, and inclusion of just 20% of 11,11-D2-Lin provided dramatic protection.

Figure 11. Small amounts of isotope-reinforced PUFAs protect yeast cells from long chain PUFA stress.

Fatty acid sensitivity assays were performed as described in Figure 4 except that yeast were treated with 300 µM of the designated PUFA or PUFA mixture for 10 hours. A zero-time untreated control is shown on the top left. Picture were taken after 3 days of growth at 30 °C.

DISCUSSION

Membrane lipids are highly vulnerable to oxidative damage due to the facile abstraction of bis-allylic H atoms from PUFAs [37]. Here we assess the effects of site-specific isotope-reinforcement of PUFAs, where the vulnerable bis-allylic H atoms are replaced with deuterium. We exploit the yeast S. cerevisiae to monitor lipid autoxidation within cells and to assess the toxicity of lipid autoxidation products. We also utilize in vitro assays of non-enzymatic PUFA autoxidation reactions to determine the kinetic D/H isotope effect. Both the yeast cell and in vitro assays suggest that substitution of bis-allylic H atoms with D atoms profoundly slows PUFA autoxidation and the generation of toxic products.

In this study we determine the KIE for PUFA autoxidation in solution. It is well established that deuteration substantially slows down the rate of enzymatic oxidation of 11,11-D2-Lin, with KIE values in the range of 80–100 [38, 39]. We found that there is a substantial KIE (12.8 ± 0.6) for the 11,11-D2-Lin autoxidation as compared to a non-deuterated Lin control from competition kinetic measurements (Fig. 3 and Table 1). The KIE obtained using parallel radical clock measurements of Lin and D2-Lin ethyl ester, 9.3 ± 1.1 (see results section and Fig. 2) is somewhat less than the values obtained from the competition method. However, the KIE obtained from the competition experiments is more reliable because of the error that occurs in the clocking experiments of 11,11-D2-Lin due to the low slope of the plot of trans,cis-/trans,trans-HODEs for this deuterated compound.

The HODE measurement mainly reflects the propagation step of the chain reaction (kp, equation 4). The KIE of 12.8 falls in the upper range of previously reported values for primary deuterium KIE of free radical peroxidation, which normally are less than 10 [40–43]. The reaction was initiated by controlled decomposition of an azo initiator (MeOAMVN, kd = 3.2 × 10−5 s−1, τ1/2 = 6 h) [44]. In addition, the termination step was not affected significantly by the presence of 11,11-D2-Lin in co-oxidation in solution based on the fact that the levels of KODEs, known peroxyl radical termination products [40], did not change significantly with the levels of 11,11-D2-Lin. Thus, all three stages of the free radical peroxidation (initiation, propagation, and termination) were accounted for in our analysis of Lin autoxidation in solution.

The measured KIE value for 11,11-D2-Lin autoxidation by analyzing the oxidation products (HODEs), fell short of the biological effect of the yeast viability rescue observed with D2-Lin and partially deuterated αLnn, which were found to be two to three orders of magnitude less toxic to the yeast mutants than the non-deuterated forms [21].

Also, the linear dependence of the total amount of HODEs formed on the fraction of D-PUFA in H-PUFA (Fig. 3C) did not correlate with our previous yeast results on the total inhibition of autoxidation achieved with partial deuteration at only one of the two bis-allylic sites in both 11,11-D2-αLnn and 14,14-D2-αLnn [21], which essentially amounted to an inhibition of autoxidation at bis-allylic sites by a 50% fraction of deuterated bis-allylic sites, i.e. a non-linear dependence.

The initiation reaction in in vitro studies employs azo compounds, which form a nitrogen molecule and two autoxidation initiating radicals. This may be quite different from the natural processes typically initiated by one radical moiety, making a caging effect more likely. The arrangement of PUFAs in membranes is also quite different from their distribution in solution.

We therefore turned to a yeast model to further investigate the effects of isotope-reinforced deuterated PUFAs. S. cerevisiae provides a sensitive model for monitoring the toxic products of lipid autoxidation. Yeast cells normally do not produce or require PUFAs, but are able to take them up and incorporate them into membrane phospholipids [45–47]. Although wild-type yeast cells are quite tolerant of PUFAs, coq mutant yeast lacking Q, an endogenously produced antioxidant lipid, are exquisitely sensitive to PUFA treatment [27, 48]. The site-specific replacement of the 11,11-bis-allylic H atoms of Lin with D rescues the hypersensitivity of the yeast Q-less mutants to PUFA treatment (Fig. 3) [21]. In contrast, replacement of the 8,8-mono-allylic H atoms with D provides no protection to Q-less yeast (Fig. 3). In these studies, lipid autoxidation was monitored with a membrane-intercalated indicator lipid, C11-BODIPY(581/591) [33]. Oxidation stimulates a fluorescence shift of this indicator lipid, and the time-dependent increase in fluorescence reflects the degree of lipid autoxidation [33]. Although the fluorescence does not yield quantitative information about lipid oxidation, it does give a sensitive read-out of radical processes that oxidize lipids in membranes [49]. We detected increased fluorescence and hence autoxidation products prior to loss of yeast cell viability. The results indicate that treatment of coq mutant yeast with either Lin or 8,8-D2-Lin produce marked levels of lipid peroxidation as compared to either untreated cells, or cells treated with 11,11-D2-Lin. We also used the yeast copper-dependent oxidation model developed by Avery et al., [36] to test the effects of isotope-reinforcement on copper-stressed wild-type yeast cells. We showed that copper-stressed wild-type yeast treated with isotope-reinforced PUFAs have lower levels of lipid autoxidation products as compared to treatment with standard PUFAs (Fig. 9). These results show that the protection afforded by bis-allylic isotope-reinforcement results from an enhanced resistance to autoxidation, and is not an artifact of the organic synthetic method, nor a property exerted by the presence of D atoms located at non-susceptible sites, and instead depends on the site-specific deuteration at the bis-allylic site of Lin.

We also used the yeast model to explore whether mixtures containing small proportions of isotope-reinforced PUFAs were protective. We showed that as little as 15 mol percent 11,11-D2-Lin in Lin, or 20 mol percent 11,11,14,14-D4-αLnn in αLnn, was sufficient to rescue the coq mutant hypersensitivity (Fig. 6). This protective effect is also observed when 11,11-D2-Lin is mixed with αLnn, or when 11,11,14,14-D4-αLnn is mixed with Lin (Fig. 7). A somewhat larger fraction of between 20% and 50% of D2-Lin is required to inhibit the autoxidation of αLnn, while (less than) 20% D4-αLnn inhibits Lin peroxidation. Yeast cell PUFA uptake reflects the ratios of exogenously supplied PUFAs (Table 2), thus these effects are unlikely to be due to differential uptake. However, direct comparison of the optimal ratios of D2-Lin: αLnn and D4-αLnn: Lin that afford protection is difficult due to the different relative toxicities of Lin and αLnn. Inclusion of isotope-reinforced PUFAs along with vulnerable PUFAs slowed autoxidation as assayed in the Q-less yeast coq mutant (Fig. 6). In contrast, inclusion of Ole, a monounsaturated fatty acid resistant to oxidation, neither rescued cell viability nor slowed autoxidation (Fig. 8). Thus the rescue afforded by isotope-reinforced PUFAs cannot be explained by a simple dilution of the toxicant. These studies indicate that the protection exerted by small amounts of isotope-reinforced PUFAs is due to inhibition of autoxidation, and illuminate our previous findings with partially reinforced PUFAs. In previous studies we noted that treatment of yeast coq mutants with either 11,11-D2-αLnn or 14,14-D2-αLnn, (reinforced at only one of the two bis-allylic positions), were as nontoxic as 11,11,14,14-D4-αLnn [21]. Treating yeast with mixtures of standard and reinforced PUFAs may mimic treatment with the partially reinforced 11,11-D2-αLnn or 14,14-D2-αLnn. Indeed, inclusion of the isotope-reinforced 11,11-D2-Lin (20 mol%) protected coq mutant yeast from long chain PUFAs stress mediated by either ARA or EPA.

In yeast cells, the observed chain reaction inhibition effects essentially amount to D-PUFAs playing an antioxidant role of terminating/inhibiting the chain process. PUFA autoxidation is initiated by the hydrogen (or deuterium, for D-PUFA) abstraction from the bis-allylic sites (Eq. 2 and Eq. 4) [6]. For 11,11-D2-Lin, the resulting conjugated radical will still contain one deuterium atom. Conceivably, the chain reaction inhibition effects observed (large KIE and ‘preservative/antioxidant’) may be influenced by both the initial step (deuterium abstraction) as well as by the presence of the remaining D in the resulting radical. To analyze these two steps separately, we tested the effectiveness of mono-deuterated 11,11-D,H-Lin. Although we anticipated that the mono-deuterated 11-H atom would be nearly as vulnerable as the H atoms on standard Lin, treatment of the coq Q-less yeast with the mono-deuterated 11,11-D,H-Lin afforded the same degree of protection as the 11,11-D2-Lin (Fig. 5). Our observation that the mono-deuterated 11,11-D,H-Lin is as non-toxic as the 11,11-D2-Lin suggests that the presence of a deuterium atom in the conjugated radical system may be important to the mechanism of protection. It is possible that the D-PUFA• radical may have altered reactivity with respect to peroxyl radical formation and/or termination reactions in a biological environment. For example, the D-PUFA• radical generated from either 11,11-D,H-Lin or 11,11-D2-Lin (similar to the pentadien-1,4-yl-3D•) might be less reactive than the equivalent standard PUFA• radical (similar to the pentadien-1,4-yl-3H•) [40, 50].

We also considered the possibility that a small secondary KIE may impact the abstraction of the bis-allylic 11-H atom adjacent to the D at position 11 in the mono-deuterated Lin. Typical values of secondary KIE are 1.2 to 1.4 [51], and a small KIE are amplified over multiple steps would be expected to significantly inhibit the progress of the chain reaction of lipid autoxidation. However, the lack of protection afforded by 11-13C-Lin, argues against this idea. This is because the bis-allylic H atom at position 11 is predicted to have a primary 13C KIE (with values up to 1.25 [35]) comparable to the secondary KIE for the bis-allylic 11-H atom adjacent to the D at position 11 in the mono-deuterated Lin. Thus it appears that the presence of D in the radical system is important for this inhibition effect.

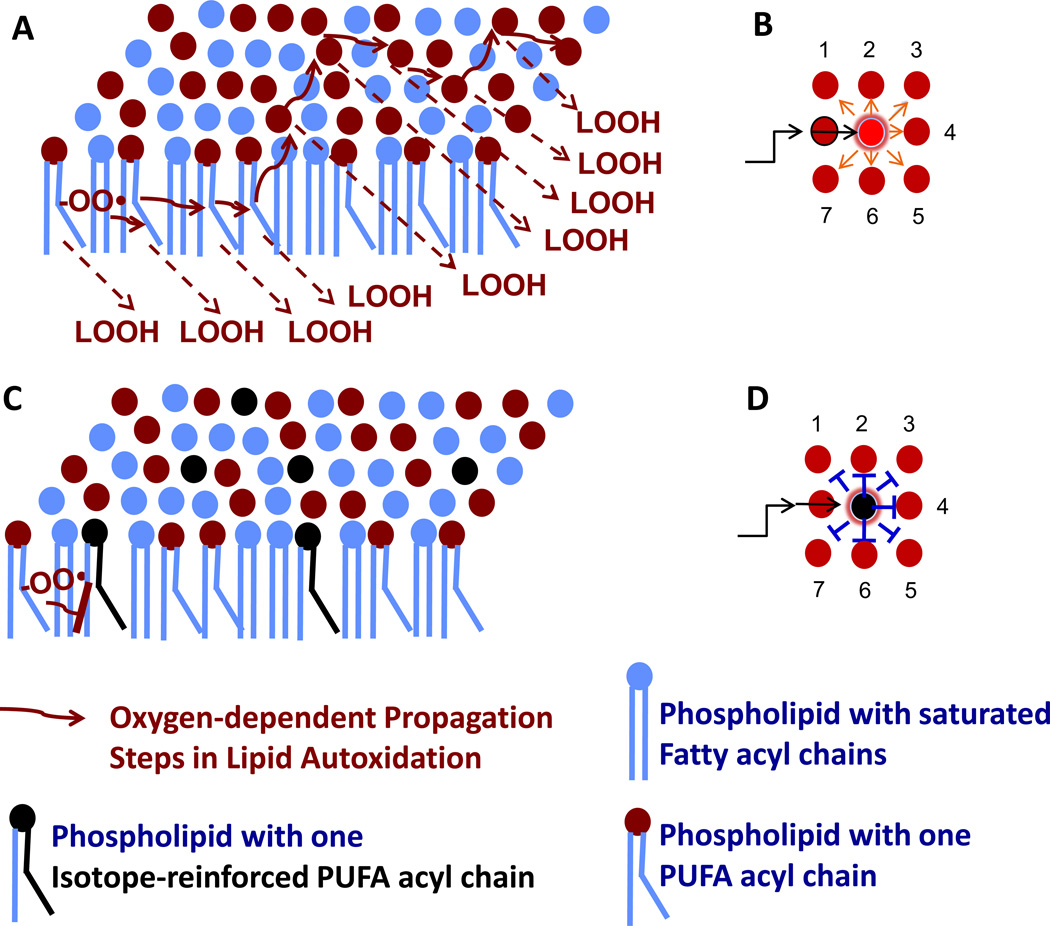

The profound protection afforded by the presence of a small fraction of isotope-reinforced PUFAs amidst vulnerable PUFAs is shown in a simple scheme in Fig. 12. Once a PUFA radical is produced it can attack other PUFAs in the lipid membrane (Fig. 12A). The probability of this reaction is higher in a bilayer of hydrogenated PUFAs than in a bilayer containing deuterated PUFAs because hydrogen abstraction is much easier than deuterium abstraction. The degree to which membranes are enriched in PUFAs correlates with the degree of electrophilic stress [20]. Conversely, membranes harboring just 20% D-PUFAs would be expected to impede the progress of the chain reaction (Fig. 12B). Deuterated PUFAs may provide a new approach to keeping electrophilic stress in check. Given that electrophilic stress is implicated in aging and neurodegenerative diseases [20], there are numerous applications where isotope-reinforced PUFAs may show efficacy [52, 53]. However, a major concern regarding the use of D-PUFAs as therapeutic agents has been that crucial enzymatic reactions involving PUFAs (e.g. lipoxygenase), are likely to be compromised due to large KIEs [38, 39]. The results presented here suggest that the inhibition of detrimental autoxidation can be achieved by employing relatively small amounts of D-PUFAs, so that most of the PUFAs will be in non-deuterated form, compatible with the enzymatic transformations. The described effect also makes it more feasible to build up necessary therapeutic levels of D-PUFAs in vivo.

Figure 12. Isotope-reinforced PUFAs limit the chain reaction of lipid autoxidation when present at only 20%.

A theoretical chain reaction is depicted where a single initiation event producing a lipid peroxyl radical (denoted by –OO•) starts a chain reaction of lipid autoxidation that in the presence of O2, may continue indefinitely (A) (red arrows), and produce many molecules of lipid peroxides; susceptible phospholipid molecules containing a PUFA acyl chain are designated by a kinked blue line and a red dot. (B) Propagation of PUFA autoxidation can progress by interaction with any neighboring PUFAs. (C) The presence of 20% isotope-reinforced PUFA (denoted by a black kinked line and a black dot) inhibit (or slow) chain propagation. (D) Propagation is inhibited for PUFAs neighboring the D-PUFA.

The limitation of the current study is our incomplete understanding of the mechanism of the reported non-additivity (antioxidant) effect of 11,11-D2-Lin in yeast (which is contrary to the effect observed in solution autoxidation), and the influence of deuterium atom(s) in the conjugated system (known to be able to transmit the secondary KIE across unsaturated sections due to hyperconjugation effects [54]) on the outcome of the chain reaction. Both the initial hydrogen/deuterium abstraction from the bis-allylic site and the presence of deuterium in the conjugated system seem to play a role, but their relative impacts are unknown, although the KIE of the H atom abstraction by the cumylperoxyl radical is around 5 at low temperature [43], and it is as large as 13 for abstraction by the linoleate-peroxyl radical at 37 °C as measured in this report. At present, we are synthesizing an additional set of variously di- and mono-deuterated and 13C-labelled Lin and αLnn to address these issues. Further insight will be obtained from in vitro kinetic studies and radical clock experiments with the isotope-reinforced PUFAs [6].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Replacement of bis-allylic H atoms with deuterium (D) arrests autoxidation of PUFA.

Linoleic acid with just one bis-allylic D replacement also resists autoxidation.

Linoleic acid with D at other sites (e.g. mono-allylic) remains susceptible.

20 mol % of deuterated PUFA profoundly inhibits the autoxidation of other PUFA

It may be feasible to build up necessary therapeutic levels of D-PUFA in vivo.

Acknowledgements

We thank Pam Ting for help with microplate reader, Dr. James Gober, Matthew Graf, and Theresa Nguyen for help with the fluorescence microscopy, Prof. Gertz I. Likhtenshtein and Dr. John K. Elder for fruitful discussions. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health General Medical Sciences Award GM45952 (to C.F.C), NSF CHE-1057500 and NIH HD064727 grants (to NAP), and by funds from Retrotope, Inc.

Mikhail S. Shchepinov and Charles R. Cantor hold stock in Retrotope, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations: αLnn, α-linolenic acid (C18:3, n–3); ARA, arachidonic acid (C20:4, n–6); BHT, butylated hydroxytoluene; D, deuterium; D2-Lin, 11,11-D2-linoleic acid or ethyl ester; D4-αLnn, 11,11,14,14-D4-α-linolenic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid (C22:5, n–3); EtOAc, ethylacetate; GC-MS, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry; HODE, hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid or hydroxyoctadecadienoate; IE, isotope effect; KIE, kinetic isotope effect; KODE, keto-octadecadienoic acid or ketooctadecadienoate; Lin, linoleic acid or ethyl ester (C18:2, n–6); MeOAMVN, 2,2’-azobis(4-methoxy-2-dimethylvaleronitrile); Ole, oleic acid (C18:1, n–9); PPh3, triphenylphosphine; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; Q, coenzyme Q or ubiquinone; QH2, coenzyme QH2 or ubiquinol; ROS, reactive oxygen species; YPD, rich growth medium with dextrose.

The other authors have no conflict to declare.

References

- 1.Miyazaki M, Ntambi JM. Fatty acid desaturation and chain elongation in mammals. In: Vance DE, Vance JE, editors. Biochemistry of Lipids, Lipoproteins, and Membranes. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dowhan W, Bogdanov M, Mileykovskaya E. Functional roles of lipids in membranes. In: Vance DE, Vance JE, editors. Biochemistry of Lipids, Lipoproteins and Membranes. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith WL, Urade Y, Jakobsson PJ. Enzymes of the cyclooxygenase pathways of prostanoid biosynthesis. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5821–5865. doi: 10.1021/cr2002992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haeggstrom JZ, Funk CD. Lipoxygenase and leukotriene pathways: biochemistry, biology, and roles in disease. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5866–5898. doi: 10.1021/cr200246d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niki E. Lipid peroxidation: physiological levels and dual biological effects. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:469–484. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin H, Xu L, Porter NA. Free radical lipid peroxidation: mechanisms and analysis. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5944–5972. doi: 10.1021/cr200084z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobretsov GE, Borschevskaya TA, Petrov VA, Vladimirov YA. The increase of phospholipid bilayer rigidity after lipid peroxidation. FEBS Lett. 1977;84:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(77)81071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatgilialoglu C, Ferreri C. Trans lipids: the free radical path. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:441–448. doi: 10.1021/ar0400847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blair IA. DNA adducts with lipid peroxidation products. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15545–15549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700051200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welsch CW. Enhancement of mammary tumorigenesis by dietary fat: review of potential mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:192–202. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parks DA, Bulkley GB, Granger DN. Role of oxygen free radicals in shock, ischemia, and organ preservation. Surgery. 1983;94:428–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angeli JP, Garcia CC, Sena F, Freitas FP, Miyamoto S, Medeiros MH, Di Mascio P. Lipid hydroperoxide-induced and hemoglobin-enhanced oxidative damage to colon cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:503–515. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milne GL, Yin H, Hardy KD, Davies SS, Roberts LJ., 2nd Isoprostane generation and function. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5973–5996. doi: 10.1021/cr200160h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serhan CN, Petasis NA. Resolvins and protectins in inflammation resolution. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5922–5943. doi: 10.1021/cr100396c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poli G, Biasi F, Leonarduzzi G. 4-Hydroxynonenal-protein adducts: A reliable biomarker of lipid oxidation in liver diseases. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long EK, Picklo MJ., Sr Trans-4-hydroxy-2-hexenal, a product of n-3 fatty acid peroxidation: make some room HNE. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Negre-Salvayre A, Coatrieux C, Ingueneau C, Salvayre R. Advanced lipid peroxidation end products in oxidative damage to proteins. Potential role in diseases and therapeutic prospects for the inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:6–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medeiros MH. Exocyclic DNA adducts as biomarkers of lipid oxidation and predictors of disease. Challenges in developing sensitive and specific methods for clinical studies. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:419–425. doi: 10.1021/tx800367d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimniak P. Relationship of electrophilic stress to aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1087–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill S, Hirano K, Shmanai VV, Marbois BN, Vidovic D, Bekish AV, Kay B, Tse V, Fine J, Clarke CF, Shchepinov MS. Isotope-reinforced polyunsaturated fatty acids protect yeast cells from oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bossie MA, Martin CE. Nutritional regulation of yeast delta-9 fatty acid desaturase activity. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6409–6413. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6409-6413.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roschek B, Jr, Tallman KA, Rector CL, Gillmore JG, Pratt DA, Punta C, Porter NA. Peroxyl radical clocks. J Org Chem. 2006;71:3527–3532. doi: 10.1021/jo0601462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu L, Davis TA, Porter NA. Rate constants for peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and sterols in solution and in liposomes. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13037–13044. doi: 10.1021/ja9029076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W, Yin H, Akazawa YO, Yoshida Y, Niki E, Porter NA. Ex vivo oxidation in tissue and plasma assays of hydroxyoctadecadienoates: Z,E/E,E stereoisomer ratios. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:986–995. doi: 10.1021/tx1000943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tzagoloff A, Wu MA, Crivellone M. Assembly of the mitochondrial membrane system. Characterization of COR1, the structural gene for the 44-kilodalton core protein of yeast coenzyme QH2-cytochrome c reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:17163–17169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Do TQ, Schultz JR, Clarke CF. Enhanced sensitivity of ubiquinone deficient mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to products of autooxidized polyunsaturated fatty acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:7534–7539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson A, Gin P, Marbois BN, Hsieh EJ, Wu M, Barros MH, Clarke CF, Tzagoloff A. COQ9, a new gene required for the biosynthesis of coenzyme Q in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31397–31404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burke D, Dawson D, Stearns T. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foulks JM, Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. A yeast PAF acetylhydrolase ortholog suppresses oxidative death. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:434–442. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tucker WP, Tove SB, Kepler CR. The synthesis of 11,11-Dideuterolinoleic acid. J Labelled Compounds. 1970;7:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer MP, Klinman JP. Synthesis of linoleic acids combinatorially-labeled at the vinylic positions as substrates for lipoxygenases. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:3600–3603. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drummen GP, van Liebergen LC, Op den Kamp JA, Post JA. C11-BODIPY(581/591), an oxidation-sensitive fluorescent lipid peroxidation probe: (micro)spectroscopic characterization and validation of methodology. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:473–490. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00848-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bigeleisen J. The Validity of the Use of Tracers to Follow Chemical Reactions. Science. 1949;110:14–16. doi: 10.1126/science.110.2844.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halevi EA. Secondary isotope effects. In: Cohen SG, Streitwieser A, Taft RW, editors. Progress in Physical Organic Chemistry. Hoboken, NH: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avery SV, Howlett NG, Radice S. Copper toxicity towards Saccharomyces cerevisiae: dependence on plasma membrane fatty acid composition. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3960–3966. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.3960-3966.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buettner GR. The pecking order of free radicals and antioxidants: lipid peroxidation, alpha-tocopherol, and ascorbate. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:535–543. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glickman MH, Wiseman JS, Klinman JP. Extremely large isotope effects in the soybean lipoxygenase-linoleic acid reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:793–794. [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGinley CM, van der Donk WA. Enzymatic hydrogen atom abstraction from polyunsaturated fatty acids. Chem Commun (Camb) 2003:2843–2846. doi: 10.1039/b311008g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell GA. Deuterium-isotope effects in the autoxidation of aralkyl hydrocarbons. Mechanism of the interaction of peroxy radicals. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:3871–3877. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howard JA, Ingold KU. Absolute rate constants for hydrocarbon autoxidation. IV. Tetralin, cyclohexene, diphenylmethane, ethylbenzene, and allylbenzene. Can J Chem. 1966;44:1113–1118. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howard JA, Ingold KU, Symonds M. Absolute rate constants for hydrocarbon oxidation. VIII. The reactions of cumylperoxy radicals. Can J Chem. 1968;46:1017–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitaguchi H, Ohkubo K, Ogo S, Fukuzumi S. Additivity rule holds in the hydrogen transfer reactivity of unsaturated fatty acids with a peroxyl radical: mechanistic insight into lipoxygenase. Chem Commun (Camb) 2006:979–981. doi: 10.1039/b515004c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noguchi N, Yamashita H, Gotoh N, Yamamoto Y, Numano R, Niki E. 2,2'-Azobis (4-methoxy-2,4-dimethylvaleronitrile), a new lipid-soluble azo initiator: application to oxidations of lipids and low-density lipoprotein in solution and in aqueous dispersions. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;24:259–268. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Black PN, DiRusso CC. Yeast acyl-CoA synthetases at the crossroads of fatty acid metabolism and regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:286–298. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cortes-Rojo C, Calderon-Cortes E, Clemente-Guerrero M, Estrada-Villagomez M, Manzo-Avalos S, Mejia-Zepeda R, Boldogh I, Saavedra-Molina A. Elucidation of the effects of lipoperoxidation on the mitochondrial electron transport chain using yeast mitochondria with manipulated fatty acid content. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2009;41:15–28. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9200-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rockenfeller P, Ring J, Muschett V, Beranek A, Buettner S, Carmona-Gutierrez D, Eisenberg T, Khoury C, Rechberger G, Kohlwein SD, Kroemer G, Madeo F. Fatty acids trigger mitochondrion-dependent necrosis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2836–2842. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.14.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poon WW, Do TQ, Marbois BN, Clarke CF. Sensitivity to treatment with polyunsaturated fatty acids is a general characteristic of the ubiquinone-deficient yeast coq mutants. Molec. Aspects Med. 1997;18:s121–s127. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(97)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacDonald ML, Murray IV, Axelsen PH. Mass spectrometric analysis demonstrates that BODIPY 581/591 C11 overestimates and inhibits oxidative lipid damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1392–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elison C, Rapoport H, Laursen R, Elliott HW. Effect of deuteration of N--CH3 group on potency and enzymatic N-demethylation of morphine. Science. 1961;134:1078–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3485.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anslyn EV, Dougherty DA. Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. Sausalito, CA: University Science Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shchepinov MS. Reactive oxygen species, isotope effect, essential nutrients, and enhanced longevity. Rejuvenation Res. 2007;10:47–59. doi: 10.1089/rej.2006.0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shchepinov MS, Chou VP, Pollock E, Langston JW, Cantor CR, Molinari RJ, Manning-Bog AB. Isotopic reinforcement of essential polyunsaturated fatty acids diminishes nigrostriatal degeneration in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Toxicol Lett. 2011;207:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shiner VJ, Kriz GS. The effects of deuterium substitution on the rates of organic reactions. X. The solvolyses of 4-chloro-4-methyl-2-pentyne and its deuterated analogs. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:2643–2645. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.