Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the efficacy and safety of nifedipine as tocolytic agent in women with preterm labor.

STUDY DESIGN

Systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials.

RESULTS

Twenty-six trials involving 2179 women were included. Nifedipine was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of delivery within 7 days of initiation of treatment (relative risk [RR], 0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.70–.097) and before 34 weeks’ gestation (RR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66–0.91), respiratory distress syndrome (RR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.46–0.86), necrotizing enterocolitis (RR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.05–0.94), intraventricular hemorrhage (RR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.34–0.84), neonatal jaundice (RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57–0.93), and admission to neonatal intensive care unit (RR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62–0.93) when compared to β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists. Sensitivity analysis restricted to high quality trials confirmed these results. There was no difference between nifedipine and magnesium sulfate for delivery within 48 hours of treatment, or birth before 34 or 37 weeks. Nifedipine was associated with a lower risk in maternal adverse events and discontinuation of treatment than tocolysis with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists and magnesium sulfate. Maintenance tocolysis with nifedipine was ineffective in prolonging gestation or improving neonatal outcomes when compared to placebo or no treatment.

CONCLUSION

Nifedipine appears to be superior to β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists and magnesium sulfate and should be considered as the first-line tocolytic agent for the management of preterm labor.

Keywords: Calcium channel blocker, preterm labor, preterm birth, tocolysis, neonatal morbidity, tocolysis, preterm birth, randomized clinical trials

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization has estimated that 12.9 million births, or 9.6% of all births worldwide, were preterm in 2005.1 In the United States, the preterm birth rate has risen over the last two decades. In 2007, preterm births constituted 12.7% of live births, an increase of 20% since 1990, and 36% since the early 1980s.2 Trends, in most other high-income countries, are similar to those in the United States.3,4 Preterm birth is the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality4 and one of the leading causes of infant mortality.2 Despite the improvement in survival rates of preterm neonates, they are at increased risk of long-term neurodevelopmental disabilities, and respiratory and gastrointestinal complications.5

Since uterine contractions are the most frequently recognized symptom and sign of preterm birth, inhibition of uterine contractions with tocolytic agents to prolong pregnancy and reduce neonatal complications has been and continues to be the focus of treatment of preterm labor. Tocolytic agents are intended to arrest uterine contractions during an episode of preterm labor (acute tocolysis) or maintain uterine quiescence after an acute episode (maintenance tocolysis). Several agents have been used for the inhibition of preterm labor but, unfortunately, it is still no clear what the first-line tocolytic agent should be:6 1) β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists reduce the risk of delivery within 48 hours of initiation of treatment.7 Nevertheless, there is no evidence that this delay in the timing of birth leads to improvements in neonatal outcomes, and maternal adverse events are substantial;7 2) magnesium sulfate is ineffective in delaying birth or preventing preterm birth, and its use could be associated with an increased risk of fetal, neonatal and infant mortality;8 3) there is not enough evidence of whether prostaglandin-synthesis inhibitors reduce the risk of preterm birth because studies have limited sample size;9 4) the oxytocin receptor antagonist, atosiban, was found to increase the proportion of patients remaining undelivered and not requiring an alternate tocolytic at 7 days when compared with placebo; yet, this was not associated with an improvement in neonatal outcomes which has been attributed to the complex design and interpretation of trials of tocolysis that involve a rescue maneuver.10 Yet, this agent has become the agent of choice in many European countries based on the results of comparative trials with beta-adrenergic agents. Barusiban, a selective oxytocin antagonist, was no more effective than placebo in delaying delivery for 48 hours;11 5) there is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of nitric oxide donors as a tocolytic drug;12 and 6) maintenance tocolysis with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists13 and oral magnesium sulfate14 is ineffective in prolonging gestation or reducing adverse neonatal outcomes. Atosiban maintenance treatment can delay the interval of time to the next episode of preterm labor, but does not reduce the rate of preterm delivery or improve infant outcomes.15

Some authors have proposed that nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker, could be used as a first-line tocolytic agent.16–18 The most recent substantial update of the Cochrane review regarding calcium channel blockers for acute tocolysis in preterm labor included 12 randomized controlled trials (10 using nifedipine) involving 1029 patients.19 This review concluded that, when compared with any other tocolytic agent (mainly beta-mimetics), calcium channel blockers (mainly nifedipine) reduce the risk of delivery within 7 days of initiation of treatment and delivery before 34 weeks of gestation with improvement in some clinically important neonatal outcomes such as respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, and neonatal jaundice. A second review from the Cochrane database on maintenance tocolysis reported that, compared with no treatment, nifedipine neither reduces the risk of preterm birth before 37 weeks of gestation nor improves neonatal outcomes.20 However, this review included only 1 trial of 74 women. The literature searches that are the basis for these two reviews were performed in 2002 and 2004, respectively. Since that time, additional randomized controlled trials with nifedipine have been published; therefore, this requires a re-assessment of the efficacy and safety of this agent.

We conducted a systematic review and metaanalysis of all available randomized controlled trials to determine the efficacy and safety of nifedipine as a tocolytic agent in patients with preterm labor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The systematic review was conducted following a prospectively prepared protocol and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials.21

Search

We searched (without language restrictions) the following computerized databases using the terms “nifedipine”, “calcium channel blocker”, “calcium antagonist”, “tocolysis”, “preterm labor”, “premature” and their associated medical subject headings (MeSH): MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and LILACS (all from inception to June 30, 2010), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/cochrane_clcentral_articles_fs.html) (1960 to June 30, 2010), ISI Web of Science (http://www.isiknowledge.com) (1960 to June 30, 2010), Research Registers of ongoing trials (www.clinicaltrials.gov, www.controlled-trials.com, www.centerwatch.com, www.anzctr.org.au, http://www.nihr.ac.uk, and www.umin.ac.jp/ctr), and Google scholar. To ensure maximum sensitivity we placed no limits or filters on the searches. Proceedings of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and international meetings on preterm birth and tocolysis, reference lists of identified studies, textbooks, previously published systematic reviews, and review articles were also searched. For studies with multiple publications, the data from the most complete report were used and supplemented if additional information appeared in other publications.

Study selection

We included randomized controlled trials in which nifedipine was used for tocolysis in patients with preterm labor compared with alternative tocolytic agents, placebo or no treatment. Trials were excluded if they were quasi-randomized, or if they only compared different doses of nifedipine or other calcium channel blockers, or if nifedipine was given in addition to or following failure of another tocolytic drug. Published abstracts alone were excluded if additional information on methodological issues and results could not be obtained. We classified trials according to aim of the treatment with nifedipine into two groups: “acute tocolysis” and “maintenance tocolysis”. Two reviewers independently evaluated studies for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through consensus among reviewers. Authors of selected studies were contacted to complement data on trial methods and/or outcomes.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes of interest were delivery within 48 hours and 7 days of treatment for acute tocolysis, delivery before 34 and 37 weeks of gestation for maintenance tocolysis, and perinatal death, admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), neurodevelopmental disability at 2 years of age, and severe maternal adverse drug reactions for both acute and maintenance tocolysis. Secondary outcomes included the interval between trial entry and delivery, gestational age at delivery, maternal adverse events, discontinuation of treatment because of adverse events, birth weight, Apgar score at 5 minutes, respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, retinopathy of prematurity, neonatal jaundice, neonatal sepsis, fetal death, neonatal death, length of stay in NICU, long term psychosocial and motor function, and pregnancy/neonatal outcomes among women enrolled at less than 32 weeks of gestation.

Study quality assessment

We conducted quality assessment according to a modified scoring system proposed by Jadad et al.22 which considers four items: randomization, blinding, follow-up, and concealment of allocation. We assigned points to each trial as follows: (1) quality of randomization (2 points: computer-generated random numbers or similar; 1 point: not described; 0 points: quasi-randomized or not randomized [we excluded such studies]); (2) double blinding (2 points: neither the person doing the assessments nor the study participant could identify the intervention being assessed; 1 point: not described; 0 points: no blinding or inadequate method); (3) follow-up (2 points: number or reasons for dropouts and withdrawals described, and assessment of primary outcomes in ≥95% of randomized women; 1 point: number or reasons for dropouts and withdrawals described but assessment of primary outcomes in <95% of randomized women; 0 points: number or reasons for dropouts and withdrawals not described); and (4) concealment of allocation (2 points: adequate method [central randomization; or drug containers or opaque, sealed envelopes that were sequentially numbered and opened sequentially only after they have been irreversibly assigned to the participant]; 0 points: no concealment of allocation or inadequate method or not described). Thus, the total score ranged from 0 (lowest quality) to 8 (highest quality). Studies that scored ≥6 points were considered to be of high quality. Two investigators (A.C.-A. and J.P.K.) independently assessed study quality, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (A.C.-A. and J.P.K.) independently extracted data from each eligible study using a standardized data abstraction form. There was no blinding of authorship. From each article, we extracted data on study characteristics (randomization procedure, blinding of providers, patients and outcome assessors, follow up period, intention to treat analysis, losses to follow up, exclusions, and concealment allocation method), participants (inclusion and exclusion criteria, definition of preterm labor, cervical dilatation and effacement at trial entry, gestational age at randomization, numbers of women randomized, baseline characteristics, and country and date of recruitment), details of intervention (aim, loading and maintenance dose, route, duration, retreatment, use of alternative tocolytic therapy, and routine administration of antenatal corticosteroids), and outcomes (number of outcome events and/or mean ± standard deviation for each outcome). Unpublished additional data used in other metaanalysis19 were included. Studies reporting preterm birth before 36 weeks’ gestation as outcome measure were included into the group of studies reporting preterm birth before 37 weeks of gestation in our data synthesis because of the relatively similar neonatal outcomes. Disagreements in extracted data were resolved by discussion among the authors.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed according to the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration.23 We analyzed outcomes on an intention-to-treat basis. If this was not clear from the original article then we carried out re-analysis when possible. If we found no evidence of a substantial difference in study populations, interventions, or outcome measurements, we performed metaanalysis. We calculated the summary relative risk (RR) for dichotomous data and weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous data with associated 95% confidence interval (CI). Four pre-specified subgroup analyses were performed to compare nifedipine with other tocoloytic agents (β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists, magnesium sulfate, atosiban, and nitric oxide donors) for acute tocolysis and one to compare nifedipine with placebo or no treatment for maintenance tocolysis. The subgroup analyses comparing nifedipine versus placebo or no treatment for acute tocolysis were not performed because trials addressing these comparisons were not identified.

Heterogeneity of the results among studies was tested with the quantity I2, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance.24 A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity whereas I2 values of 50% or more indicate a substantial level of heterogeneity.24 We planned to pool data across studies using the fixed-effects models if substantial statistical heterogeneity was no present. We used random-effects models to pool data across studies if I2 values ≥50%. A predefined sensitivity analysis was performed to explore the impact of study quality on the effect size for the main outcomes. This was performed by excluding trials with modified Jadad score <6. We conducted additional analyses stratified according to the following characteristics: definition of preterm labor (based on uterine contractions plus cervical changes versus based on uterine contractions alone), mean or median cervical dilatation at trial entry (<2 versus ≥2 cm), membranes status (intact versus ruptured), plurality (singleton versus twin pregnancy), mean gestational age at trial entry (≤30 weeks versus >30 weeks), study setting (developed versus developing countries), maintenance therapy in studies evaluating acute tocolysis (yes versus no/not reported), use of alternative tocolytic therapy (yes versus no/not reported), and antenatal corticosteroid therapy (yes versus no/not reported). The meta-analyses according to plurality of pregnancy and membranes status, however, were not undertaken due to insufficient data. Univariable random-effects meta-regression models23 were used to examine whether effect sizes were affected by these study characteristics.

We assessed publication and related biases visually by examining the symmetry of funnel plots and statistically by using the Egger test.25 The larger the deviation of the intercept of the regression line from zero, the greater was the asymmetry and the more likely it was that the metaanalysis would yield biased estimates of effect. We considered P<0.1 to indicate significant asymmetry, as suggested by Egger.

We also calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) for an additional beneficial outcome with its 95% CI for outcomes in which the treatment effect was significant at the 5% level (the 95% CI for the absolute risk difference did not include zero).26 NNT was computed from the results of metaanalysis of relative risks as follows:

In this review, NNT for an additional beneficial outcome is the number of women in preterm labor who need to be treated with nifedipine rather than with other tocolytic agents, placebo or no treatment to prevent one case of delivery within 48 hours or 7 days, or before 34 or 37 weeks, or adverse neonatal outcome.

Analyses were performed with the Review Manager (RevMan) software version 5.0.23 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Denmark), StatsDirect version 2.7.8 (StatsDirect Ltd, United Kingdom), and Stata, version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

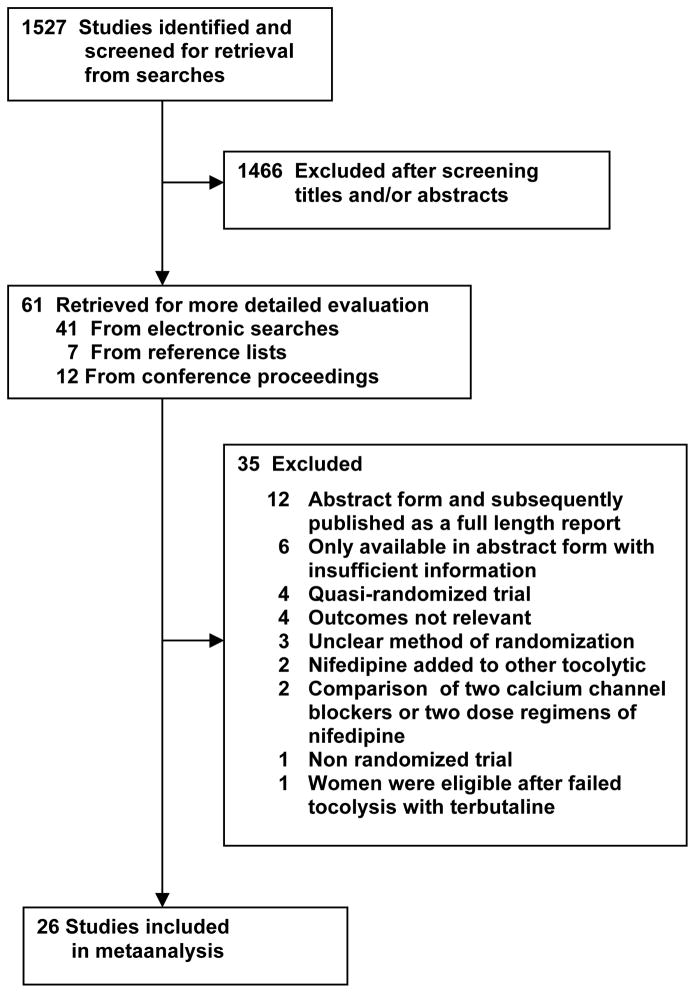

We identified 1527 studies in our literature search and considered 61 to be potentially eligible (Figure 1). Twenty-six studies, including 2179 women, fulfilled inclusion criteria of which 23 evaluated acute tocolysis27–49 and 3 evaluated maintenance tocolysis.50–52 There was strong agreement on the inclusion of studies (κ = 0.89). Additional neonatal data and long term follow up data for 1 trial32 were reported in 2 additional publications.53,54 Of the 23 trials on acute tocolysis, 16 evaluated nifedipine versus β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists (11 studies using ritodrine,27–34,36,39,42 3 studies using terbutaline,37,40,41 and 2 studies using isoxsuprine35,38), 5 evaluated nifedipine versus magnesium sulfate,43–47 and 1 each evaluated nifedipine versus atosiban48 and nifedipine versus nitric oxide donors.49 There were no trials in which nifedipine was compared with placebo or no treatment in acute tocolysis. Of the 3 trials on maintenance tocolysis, 2 evaluated nifedipine versus no treatment50,51 and 1 evaluated nifedipine versus placebo.52 In the study by Koks et al,33 only the subset of patients who were not treated with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists before trial entry was included (57 of 102 women). Thirty-four studies were excluded for the following reasons: initially available in abstract form and subsequently published as a full-length report (N=12); only available in abstract form with insufficient information on methods and results (N=6); method of generation of allocation to treatment was quasi-randomized (N=4); unclear method of randomization (N=3); study did not report relevant outcomes (N=4); nifedipine was used in combination with other tocolytic agents (N=2); comparison of two calcium channel blockers (N=1); comparison of two dose regimens of nifedipine (N=1); non-randomized trial (N=1); and women were enrolled only after subcutaneous terbutaline failed to inhibit contractions (N=1). The list of excluded studies is available from the authors upon request.

Figure 1.

Study selection process

Characteristics of the studies included in the review are summarized in Table 1. Seven studies were conducted in the United States,28,30,43,44,47,50,52 11 in Asian countries,31,35–38,40,41,45,46,48,51 7 in European countries,27,29,32–34,39,42 and 1 in Brazil.49 The sample size ranged from 4027,40 to 19247 (median, 74). Preterm labor was consistently defined as presence of uterine contractions with evidence of cervical changes in 16 trials.28–31,36–38,40,41,43,44,48–52 Ten studies did not include cervical changes in the diagnosis of preterm labor.27,32–35,39,42,45–47 Nineteen studies were limited to women with intact membranes,27,30,31,34–39,41,43–46,48–52 7 included also women with ruptured membranes,28,29,32,33,40,42,47 and 8 included women with a twin pregnancy.31,33,38,41,47,48,51,52 Standard maternal and fetal contraindications to tocolysis were reported as exclusion criteria in the great majority of included studies.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review

| First author, year | Location | Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Gestational age (weeks) | Interventions (sample size) | Alternative tocolytic therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACUTE TOCOLYSIS | |||||

|

NIFEDIPINE COMPARED WITH β2-ADRENERGIC-RECEPTOR AGONISTS

| |||||

| Read,27 1986 | United Kingdom | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: multiple pregnancy, polyhydramnios, premature rupture of membranes, history of cervical surgery, history of mid-trimester abortion or previous preterm delivery, history of any medical condition which would contraindicate the use of either of the drugs, chorioamnionitis, any irregularity of the fetal heart rate, and cervical dilatation >4 cm. |

20–35 | Nifedipine (N=20): 30 mg orally. Then 20 mg orally every 8 h for 3 days. Ritodrine (N=20): 50 μg/min IV increasing by 50 μg every 10 min to a maximum of 300 μg for 24 h. Then 10 mg orally oral every 4 h for 48 h. |

Ritodrine in nifedipine group |

|

| |||||

| Ferguson,28 1990 | United States | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor irrespective of the membranes status. Exclusion: previous treatment with tocolytics in current pregnancy, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, cardiac disease, severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, placental abruption, chorioamnionitis, multiple pregnancy, polyhydramnios, cervical dilatation >4 cm, fetal distress, severe intrauterine growth retardation, fetal death, and fetal anomaly incompatible with life. |

20–36 | Nifedipine (N=33): 10 mg sublingually. If uterine contractions persisted after 20 min, a similar dose was repeated at intervals of 20 min, up to a maximal total dose of 40 mg during the first h of treatment. Then 20 mg orally every 4–6 h. Ritodrine (N=33): 50 μg/min IV increasing by 50 μg every 15–30 min up to a maximum of 350 μg/min. Then 10–20 mg orally every 4–6 h. |

Alternate regimen and terbutaline |

|

| |||||

| Janky,29 1990 | France | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor. Exclusion: chorioamnionitis, fetal death, fetal anomaly incompatible with life, medical condition contraindicating the use of betamimetics, cervix >4 cm, and premature rupture of membranes after 34 weeks. |

28–36 | Nifedipine (N=30): 10 mg sublingually. Then 20 mg orally every 8 h for 7 days. Ritodrine (N=32): 200–300 μg/min IV until contractions ceased. Then 100 μg/min for 24 h. Thereafter 20 mg orally every 4–6 h for 6 days. |

Permitted but unspecified |

|

| |||||

| Bracero,30 1991 | United States | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: multiple pregnancy, premature rupture of membranes |

20–36 | Nifedipine (N=26): 30 mg orally. Then 20 mg orally every 6 h for 24 h, then decreased to 8-hours intervals for an additional 24 h. Thenceforth, 20 mg every 8–12 h. No data on duration of treatment. Ritodrine (N=23): 100 μg/min IV increasing by 50 μg/min every 10 min to a maximum of 350 μg/min. Thirty min prior to discontinuation of IV ritodrine, 10 mg orally every 2 h for 24 h. Then 10 mg every 4 h for 24 h. Then 20 mg every 8–12 h. Thereafter, 10–20 mg orally every 4–6 h. No data on duration of treatment. |

Ritodrine and magnesium sulfate in nifedipine group and magnesium sulfate in ritodrine group |

|

| |||||

| Kupferminc,31 1993 | Israel | Inclusion: women with singleton or twin pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: polyhydramnios, placental abruption, hypertension, infection, any medical condition that would contraindicate tocolytic therapy, cervical dilatation >4 cm, and premature rupture of membranes. |

26–34 | Nifedipine (N=36): 30 mg orally. Then 20 mg after 90 min if contractions persisted. Thereafter 20 mg every 8 hours until 34–35 weeks. Ritodrine (N=35): 50 μg/min IV increasing by 15 μg/min every 15 min to a maximum of 300 μg/min for 12 h. Then 10 mg orally every 3 h until 34–35 weeks. |

Ritodrine in nifedipine group |

|

| |||||

| Papatsonis,32 1997 | The Netherlands | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor irrespective of the membranes status. Exclusion: multiple pregnancy, intrauterine infection, fetal congenital anomalies, abruption placenta, severe fetal growth restriction, and any contraindication for the use of beta-adrenergic drugs. |

20–33 4/7 | Nifedipine (N=95): 10 mg sublingually. If contractions persisted, this dose was repeated every 15 min to maximum of 40 mg during the first hour of treatment. Then 60–160 mg/day of slow-release nifedipine until 34 weeks. Ritodrine (N=90): 383 μg/min IV after which the infusion rate was determined by the time lag after which tocolysis is established (minimum 100 μg/min) for at least 3 days. Then ritodrine 40 mg orally every 8 h until 34 weeks in two of the three participating hospitals. |

Nifedipine in ritodrine group; Indomethacin in both groups |

|

| |||||

| Koks,33a 1998 | The Netherlands | Inclusion: women with singleton or twin pregnancy in preterm labor irrespective of the membranes status. Exclusion: any contraindication for the use of nifedipine or betamimetic, intrauterine infection, irregular fetal heart rate, antepartum hemorrhage, and polyhydramnios. |

24–34 | Nifedipine (N=32): 30 mg sublingually. Then 20 mg orally every 6–12 h which was reduced to 20 mg every 8 h until 34 weeks. Ritodrine (N=25): 200 μg/min IV up to maximum of 400 μg/min. Then 80 mg orally every 8 h until 34 weeks. |

Indomethacin in both groups |

|

| |||||

| García-Velasco,34 1998 | Spain | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: previous tocolytic treatment, cervical dilatation ≥3 cm, maternal infection, vaginal bleeding, and any medical or obstetrical condition contraindicating tocolytic therapy. |

26–34 | Nifedipine (N=26): 30 mg (20 mg orally and 10 mg sublingually). Then 10–20 mg every 4–6 h. No data on duration of treatment or maintenance therapy. Ritodrine (N=26): 50 μg/min IV increasing by 50 μg/min every 20 min to a maximum of 350 μg/min for 12 h. Then 5 mg orally every 3 h. No data on duration of treatment or maintenance therapy. |

Indomethacin in both groups |

|

| |||||

| Ganla,35 1999 | India | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor. No data on membranes status. Exclusion: diabetes, hyperthyroidism, cardiac disease, severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, placental abruption, chorioamnionitis, cervical dilatation >3 cm, severe fetal growth restriction, and lethal fetal anomalies. |

26–36 | Nifedipine (N=50): 5 mg sublingually. If contractions persisted, this dose was repeated every 15 min to maximum of 40 mg during the first two hours of treatment. Then 10 mg orally every 8 h for 48 h. Thereafter 10–20 mg orally every 12 h until 36 weeks. Isoxsuprine (N=50): 0.5 mg/min IV increasing to a maximum of 10 mg/min for 12 h. Then 10 mg IM every 8 h for 48 h. Thereafter 10–20 mg orally every 8 h until 36 weeks. |

Not reported |

|

| |||||

| Al-Qattan,36 2000 | Kuwait | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: multiple pregnancy, cardiac disease, placental abruption, hyperthyroidism, severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, infection, cervical dilatation ≥4 cm, polyhydramnios, fetal pathology, premature rupture of membranes, breech presentation, fetal death, fetal distress, and congenital malformation. |

24–34 | Nifedipine (N=30): 30 mg orally. If contractions persisted after 2 h, a second dose of 20 mg was given. Then 20 mg orally every 6 h until 34 weeks. Ritodrine (N=30): 50 μg/min IV. Then 10 mg orally every 4–6 h until 34 weeks. |

Not reported |

|

| |||||

| Weerakul,37 2002 | Thailand | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: multiple pregnancy, premature rupture of membranes, previous tocolytics, cervical dilatation >3 cm, chorioamnionitis, infection, fetal distress, fetal anomalies, and medical or obstetrical complications. |

28–34 | Nifedipine (N=45): 10 mg sublingually. If contractions persisted after 15 min, a second dose of 10 mg was given. Then 20 mg after 30 min to a maximum in the first hour of 40 mg. Then 60–120 mg orally per day for 3 days. No data on maintenance therapy. Terbutaline (N=44): 0.25 mg IV followed by continuous IV infusion started at 5 μg/min and increased by 5 μg/min every 15 min up to a maximum of 15 μg/min. Then the infusion was maintained at the same rate for 2 h, after which the treatment was continued with subcutaneous injection of 0.25 mg every 4 h for 24 h. No data on maintenance therapy. |

Not reported |

|

| |||||

| Rayamahji,38 2003 | Nepal | Inclusion: women with singleton or twin pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: premature rupture of membranes, advanced labor, preeclampsia, eclampsia, cardiac disease, thyroid disorder, antepartum hemorrhage, polyhydramnios, chorioamnionitis, severe fetal growth restriction, fetal death, oligoamnios, fetal anomalies incompatible with life. |

28–36 | Nifedipine (N=32): 10 mg sublingually. This dose was repeated every 20 min to maximum of 40 mg during the first hour of treatment. Then 10–20 mg orally every 6–8 h for up to 7 days. Isoxsuprine (N=30): 0.08 mg/min IV increasing to a maximum of 0.24 mg/min. Then 10 mg orally every 8 h for up to 7 days. |

Not reported |

|

| |||||

| Cararach,39 2006 | Spain | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: cervical dilatation >5 cm, polyhydramnios, fetal anomalies, fetal distress, intrauterine infection, fetal growth restriction, contraindication for the use of betamimetic drugs, and previous treatment with tocolytics in current pregnancy. |

22–35 | Nifedipine (N=40): 30 mg (20 mg orally and 10 mg sublingually). Then 20 mg orally every 6 h for 48 h. There was no maintenance therapy. Ritodrine (N=40): 100 μg/min IV increasing by 50 μg/min every 20 min to a maximum of 350 μg/min for 48 h followed by 10 mg orally every 6 h until discharge. There was no maintenance therapy. |

Alternate regimen and indomethacin |

|

| |||||

| Laohapojanart,40 2007 | Thailand | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor irrespective of the membranes status. Exclusion: multiple pregnancy, heart or renal disease, hypertension, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, placenta previa, preeclampsia, diabetes, and thyrotoxicosis. |

24–36 | Nifedipine (N=20): 10 mg orally. If contractions persisted, 10 mg orally every 4 h to a maximum in the first hour of 40 mg. Then 20 mg every 4 h for 3 days. No data on maintenance therapy. Terbutaline (N=20): 10 μg/min IV followed by continuous IV infusion with an increment 5 μg/min every 10 min until 25 μg/min was reached. Then subcutaneous injection of 0.25 mg every 4 h for 24 h. No data on maintenance therapy. |

Alternate regimen and indomethacin |

|

| |||||

| Mawaldi,41 2008 | Saudi Arabia | Inclusion: women with singleton or twin pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: women carrying more than 2 fetuses, major antepartum hemorrhage, premature rupture of membranes, major medical disorder, temperature >37.5 °C, blood pressure <90/50 mm Hg, compromised fetus, and lethal fetal anomalies |

24–34 | Nifedipine (N=79): 30 mg orally followed by 20 mg after 90 min. If contractions persisted, 20 mg orally every 8 h for 48 h. No data on maintenance therapy. Terbutaline (N=95): 0.25 mg subcutaneous repeated every 45 min if the uterine contractions persisted. No data on maintenance therapy. |

Not reported |

|

| |||||

| Van De Water,42 2008 | The Netherlands | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor irrespective of the membranes status. Exclusion: multiple pregnancy, intrauterine infection, fetal congenital defects, placental abruption, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, hyperthyroidism, and preeclampsia. |

24–34 | Nifedipine (N=48): 20 mg orally. If contractions persisted after 30 min, a second dose of 20 mg was given. Then 90–120 mg orally per day for 48 h. Thereafter 90 mg/day for 7 days. Ritodrine (N=43): 200 μg/min IV increasing by 50 μg/min every 30 min until quiescence was achieved for 48 h. Then 80 mg orally every 8 h for a total duration of 7 days. |

Indomethacin |

|

| |||||

|

NIFEDIPINE COMPARED WITH MAGNESIUM SULFATE

| |||||

| Glock,43 1993 | United States | Inclusion: primigravid women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes Exclusion: multiple pregnancy, premature rupture of membranes, known tocolytic drug exposure during the study pregnancy, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, cardiac disease, preeclampsia, abruptio placentae, chorioamnionitis, hydramnios, renal failure, cervical dilation ≥4 cm, fetal distress, severe intrauterine growth restriction, and fetal anomaly incompatible with life |

20–34 | Nifedipine (N=39): 10 mg sublingually. If contractions persisted, this dose was repeated every 20 min to maximum of 40 mg during the first hour of treatment. Once contractions ceased, 20 mg orally every 4 h for 48 h, then 10 mg orally every 8 h until 34 weeks. Magnesium sulfate (N=41): 6-g bolus then 2 g/h, increased to maximum of 4 g/h, until quiescence for 24 h. Then, weaned at 0.5 g every 4–6 h. Thereafter terbutaline 5 mg orally every 6 hours until 34 weeks. |

Intravenous ritodrine |

|

| |||||

| Floyd,44 1995 | United States | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: Previous tocolytic therapy in current pregnancy, allergy to either study drug, medical or obstetric complications precluding treatment with either drug, and chorioamnionitis. |

20–34 | Nifedipine (N=50): 30 mg orally followed by 20 mg every 8 h until quiescence. Then 20 mg orally every 8 h until 37 weeks or delivery, whichever occurred first. Magnesium sulfate (N=40): 4-g bolus then 4–6 g/h continued for 6 h after quiescence. Then magnesium gluconate 2 g orally every 4 h until 37 weeks or delivery, whichever occurred first. |

Not reported |

|

| |||||

| Haghighi,45 1999 | Iran | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes Exclusion: known tocolytic drug exposure during the study pregnancy, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, cardiac disease, preeclampsia, placental abruption, chorioamnionitis, polyhydramnios, renal failure, cervical dilation ≥4 cm, fetal distress, severe intrauterine growth restriction, and fetal anomaly incompatible with life |

23–36 | Nifedipine (N=34): 10 mg sublingually. If contractions persisted, this dose was repeated every 20 min to maximum of 40 mg during the first hour of treatment. Once contractions ceased, 20 mg orally every 6 h during the first 24 h and 20 mg every 8 h the second day. No data on maintenance therapy. Magnesium sulfate (N=40): 6-g bolus then 2 g/h, increased to maximum of 4 g/h, until quiescence for up to 48 h. Then, terbutaline 5 mg orally every 6 h. No data on maintenance therapy. |

Not reported |

|

| |||||

| Taherian,46 2007 | Iran | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: taking other tocolytic agents, cervical dilatation ≥5 cm or obstetrical contraindications for tocolysis such as severe preeclampsia, lethal fetal anomalies, chorioamnionitis, significant antepartum hemorrhage, and maternal cardiac or liver diseases. |

26–36 | Nifedipine (N=57): 10 mg orally every 20 min (maximal dose of 40 mg in first hour). Once contractions ceased, 10–20 mg orally every 6 h. No data on duration of treatment or maintenance therapy. Magnesium sulfate (N=63): 4-g bolus then 2–3 g/h. No data on duration of treatment or maintenance therapy. |

Ritodrine or indomethacin (18% in nifedipine group and 13% in magnesium sulfate group) |

|

| |||||

| Lyell,47 2007 | United States | Inclusion: women with singleton or twin pregnancy in preterm labor irrespective of the membranes status. Exclusion: placental abruption, placenta previa, non reassuring fetal status, intrauterine growth restriction, chorioamnionitis, and maternal medical disease. |

24–33 | Nifedipine (N=100): 10 mg sublingually every 20 min for three doses total, followed by 20 mg orally every 4–6 h until at least 12 h of uterine quiescence occurred within the first 48 h. Maintenance therapy with nifedipine in 42% of women. Magnesium sulfate (N=92): 4-g bolus then 2 g/h, increased to maximum of 4 g/h, until at least 12 h of uterine quiescence occurred within the first 48 h. Maintenance therapy with nifedipine in 38% of women. |

Permitted but unspecified |

|

| |||||

|

NIFEDIPINE COMPARED WITH ATOSIBAN

| |||||

| Kashanian,48 2005 | Iran | Inclusion: women with singleton or twin pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: premature rupture of membranes, vaginal bleeding, fetal death, fetal distress, fetal growth restriction, history of trauma, cervical dilatation >3 cm, maternal systemic disorders, uterine anomaly, and blood pressure <90/50 mm Hg. |

26–34 | Nifedipine (N=40): 10 mg sublingually every 20 min to a maximum in the first hour of 40 mg. Then 20 mg orally every 6 h for the first 24 h, and then every 8 h for the following 24 h. Thereafter, 10 mg orally every 8 h for the last 24 h. There was no maintenance therapy. Atosiban (N=40): 300 μg/min IV, continued for a maximum of 12 h, or 6 h after contractions were inhibited. There was no maintenance therapy. |

Not reported |

|

| |||||

|

NIFEDIPINE COMPARED WITH NITRIC OXIDE DONORS

| |||||

| Amorim,49 2009 | Brazil | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy in preterm labor and intact membranes. Exclusion: premature rupture of membranes, preeclampsia, diabetes, placental abruption, fetal malformation, and previous treatment with tocolytics. |

24–34 | Nifedipine (N=24): 10 mg sublingually repeated after 30 min. Then 20 mg orally every 6 h for at least 24 h. No data on maintenance therapy. Nitroglycerin (N=26): 10 mg transdermal patch. If contractions persisted after 6 h, a second patch of 10 mg was placed (maximum dose of 20 mg/24 h). No data on maintenance therapy. |

Terbutaline |

|

| |||||

| MAINTENANCE TOCOLYSIS | |||||

|

NIFEDIPINE COMPARED WITH PLACEBO/NO TREATMENT

| |||||

| Carr,50 1999 | United States | Inclusion: women with singleton pregnancy who had been in active preterm labor successfully arrested with IV magnesium sulfate. Exclusion: cervical dilatation ≥5 cm, obstetric contraindications to tocolysis (severe preeclampsia, lethal fetal anomalies, chorioamnionitis, significant antepartum hemorrhage), or maternal cardiac or liver disease. |

24–33 | Nifedipine (N=37): 20 mg orally every 4–6 h until 37 weeks. It was initiated after discontinuation of acute IV tocolysis. Control (N=37): no treatment |

Magnesium sulfate or terbutaline |

|

| |||||

| Sayin,51 2004 | Turkey | Inclusion: women with singleton or twin pregnancy and intact membranes who had been in active preterm labor successfully arrested with IV ritodrine and verapamil. Exclusion: cervical dilatation ≥4 cm, triple or higher order pregnancy, intrauterine infection, fetal congenital anomalies, fetal growth restriction, and any contraindication to betamimetics such as diabetes mellitus, cardiac disease, or hyperthyroidism. |

Not stated | Nifedipine (N=37): 20 mg orally every 6 h until 37 weeks. It was initiated after discontinuation of acute IV tocolysis. Control (N=36): no treatment |

Ritodrine and verapamil |

|

| |||||

| Lyell,52 2008 | United States | Inclusion: women with singleton or twin pregnancy and intact membranes who had been in active preterm labor successfully arrested with IV magnesium sulfate or oral nifedipine. Exclusion: placental abruption, placenta previa, fetal anomaly incompatible with life, triple or higher-order multiple pregnancies, intrauterine infection, or a maternal medical contraindication to ongoing tocolysis. |

24–34 | Nifedipine (N=33): 20 mg orally every 6 h until 37 weeks. It was initiated after discontinuation of acute IV tocolysis. Control (N=35): placebo |

Magnesium sulfate |

Women receiving β2-agonists immediately before randomization (N=45) were excluded from analyses

The gestational age at inclusion varied from 20 to 36 weeks. The minimum gestational age at trial entry ranged from 20 to 28 weeks, and the maximum from 33 to 36 weeks. Most trials included women between 24 and 34 weeks of gestation. Mean gestational age at trial entry varied from 29.1 to 32.4 weeks.

For studies evaluating acute tocolysis, nifedipine dosing regimens were similar across the trials with loading doses of 10 to 30 mg administered orally or sublingually, followed by 10 to 20 mg orally every four to eight hours for 24 to 72 hours. Twelve studies28,32,35,37,38,40,42,43,45–48 repeated a loading dose every 15 to 20 minutes to a maximum of 40 mg during the first hour of treatment if contractions persisted. Eleven trials29–33,35,36,42–44,47 reported maintenance therapy, 927,28,34,37,40,41,45,46,49 did not, and 338,39,48 stated there was no maintenance therapy. Seven studies31–33,35,36,43,44 used oral maintenance therapy in both treatment groups until 34 to 37 weeks of gestation. All but 3 trials30,34,36 reported the total duration of treatment. All studies evaluating maintenance tocolysis50–52 used nifedipine 20 mg orally every 4 to 6 hours until 37 weeks of gestation or delivery, whichever occurred first. Use of alternative tocolytic therapy was explicitly mentioned in 18 studies27–34,39,40,42,43,46,47,49–52 Twenty trials28,31–38,40–43,46–52 reported administration of antenatal corticosteroids for all women enrolled. In the remaining 6 trials27,29,30,39,44,45 antenatal corticosteroids use was not reported.

Table 2 shows quality assessment of included studies. All but 5 studies35,38,43,45,51 had adequate generation of allocation sequence. Sixteen studies28–30,32–34,37,39,41–44,47,49,50,52 reported adequate concealment of allocation. For all of the 23 studies evaluating acute tocolysis, blinding of the intervention was not performed and blinding assessment of outcomes was not reported. Only 1 study52 evaluating maintenance tocolysis was double-blinded. Eighteen trials reported assessment of primary outcomes in ≥95% of randomized women.27–35,37,39,41,42,44,45,47,51,52 Thirteen trials (50%) had a modified Jadad score of 6 or more.28–30,32–34,37,39,41,42,44,47,52

TABLE 2.

Methodological quality assessment (modified Jadad scoring system22) of included studies

| Study | Randomization | Blinding | Follow-up | Allocation concealment | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read27 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Ferguson28 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Janky29 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Bracero30 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Kupferminc31 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Papatsonis32 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Koks33 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| García-Velasco34 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Ganla35 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Al-Qattan36 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Weerakul37 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Rayamahji38 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Cararach39 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Laohapojanart40 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Mawaldi41 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Van De Water42 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Glock43 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Floyd44 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Haghighi45 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Taherian46 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Lyell47 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Kashanian48 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Amorim49 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Carr50 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Sayin51 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Lyell52 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

Scores: 0=lowest quality, 8=highest quality

Acute tocolysis

1. Nifedipine versus β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists

This subgroup analysis included data from 16 trials with a total of 1278 women. Compared with women receiving β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists, those using nifedipine had a statistically significant reduction in the risk of delivery within 7 days of initiation of treatment (37.1% vs 45.0%; RR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70–0.97; I2=0.0%) (Table 3). The number of women with preterm labor who need to be treated (NNT) with nifedipine rather than with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists to prevent one case of delivery within 7 days of treatment is 12 (95% CI, 7–63). Nifedipine was also associated with a decreased risk of delivery before 34 weeks of gestation (48.4% vs 62.2%; RR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66–0.91; I2=0.0%; NNT for benefit, 7; 95% CI, 5–24), maternal adverse events (19.5% vs 56.1%; RR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.18–0.54; I2=84.0%; NNT for benefit, 3; 95% CI, 2–5), and discontinuation of treatment because of adverse events (0.6% vs 8.8%; RR, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.06–0.31; I2=0.0%; NNT for benefit, 13; 95% CI, 12–21). A significant increase in gestational age at birth (weighted mean difference [WMD] 0.7 weeks; 95% CI, 0.3–1.2; I2=0.0%), interval between trial entry and delivery (WMD, 5.8 days; 95% CI, 1.4–10.2; I2=63.0%), and birth weight (WMD, 178.8 gm; 95% CI, 84.1–273.6; I2=31.0%) was also shown. No difference was seen for the risk of delivery within 48 hours of initiation of treatment or before 37 weeks of gestation.

TABLE 3.

Acute tocolysis: nifedipine compared with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists

| Outcome | No of trials | Number of events/total number or Total number | Relative risk or Mean difference (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nifedipine | β2-agonists | ||||

| Pregnancy outcomes | |||||

| Delivery within 48 hours of treatment | 1327,28,31–34,36–42 | 114/535 | 126/524 | 0.84 (0.68, 1.05) | 35 |

| Delivery within 7 days of treatment | 1028,31–33,36–40,42 | 153/410 | 171/380 | 0.82 (0.70, 0.97) | 0 |

| Preterm birth <34 weeks’ gestation | 532,33,36,37,42 | 121/250 | 140/225 | 0.77 (0.66, 0.91) | 0 |

| Preterm birth <37 weeks’ gestation | 928,31,32,34,36–40 | 214/356 | 206/336 | 0.97 (0.87, 1.08) | 3 |

| Pregnancy prolongation (days) | 927,29,30,32,34,35,37–39 | 360 | 350 | 5.8 (1.4, 10.2) | 63 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 830,32,33,36–40 | 319 | 291 | 0.7 (0.3, 1.2) | 0 |

| Maternal adverse drug reaction | 927,28,31,32,37,39–42 | 81/415 | 235/419 | 0.31 (0.18, 0.54) | 86 |

| Discontinuation of treatment because of adverse effects | 1328–39,42 | 3/522 | 44/498 | 0.14 (0.06, 0.31) | 0 |

| Perinatal and neonatal outcomes | |||||

| Birthweight (grams) | 1027,30,32–34,36–40 | 365 | 335 | 178.8 (84.1, 273.6) | 31 |

| Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes | 231,32 | 6/137 | 10/130 | 0.6 (0.2, 1.5) | 0 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 1328–37,39,40,42 | 56/516 | 81/483 | 0.63 (0.46, 0.86) | 0 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 530,32,37,39,42 | 1/250 | 8/235 | 0.21 (0.05, 0.94) | 0 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 628,32,36,37,40,42 | 23/271 | 41/249 | 0.53 (0.34, 0.84) | 0 |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | 232,42 | 0/143 | 5/133 | 0.15 (0.02, 1.28) | 0 |

| Neonatal jaundice | 230,32 | 51/118 | 66/109 | 0.73 (0.57, 0.93) | 48 |

| Neonatal sepsis | 629,30,32,37,39,42 | 27/280 | 37/267 | 0.70 (0.45, 1.09) | 0 |

| Perinatal mortality | 1127–32,34,36–39 | 12/415 | 11/396 | 1.02 (0.49, 2.14) | 0 |

| Fetal death | 1127–32,34,36–39 | 1/415 | 1/396 | 1.00 (0.14, 6.96) | 0 |

| Neonatal death | 1427–34,36–40,42 | 15/518 | 13/483 | 1.03 (0.53, 2.02) | 0 |

| Admission to NICU | 929–34,37,40,42 | 97/364 | 116/338 | 0.76 (0.62, 0.93) | 0 |

| NICU stay (days) | 230,42 | 71 | 62 | −7.2 (−11.2, −3.3) | 0 |

| Any mental retardation at 2 years of age | 142 | 9/28 | 12/35 | 0.94 (0.46, 1.90) | NA |

| Behavioral-emotional functioning score at age 9–12 years | 132 | 45 | 51 | −1.5 (−4.7, 1.8) | NA |

| Quality of life score at age 9–12 years | 132 | 44 | 50 | −0.3 (−0.7, 0.1) | NA |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

Treatment with nifedipine was associated with an overall reduction in respiratory distress syndrome (10.9% vs 16.8%; RR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.46–0.86; I2=0.0%; NNT for benefit, 16; 95% CI, 11–51), necrotizing enterocolitis (0.4% vs 3.4%; RR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.05–0.94; I2=0.0%; NNT for benefit, 37; 95% CI, 31–514), intraventricular hemorrhage (8.5% vs 16.5%; RR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.34–0.84; I2=0.0%; NNT for benefit, 13; 95% CI, 9–42), neonatal jaundice (43.2% vs 60.6%; RR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57–0.93; I2=48.0%; NNT for benefit, 6; 95% CI, 4–30), admission to NICU (26.6% vs 34.3%; RR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62–0.93; I2=0.0%; NNT for benefit, 12; 95% CI, 7–48), and NICU length of stay (WMD, −7.2 days; 95% CI, −11.2 to −3.3; I2=0.0%). No statistically significant differences were seen for perinatal mortality, fetal and neonatal death, neonatal sepsis, Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes, retinopathy of prematurity, neurodevelopmental delay at 2 years of age, and psychosocial and motor function at 9–12 years of age.

2. Nifedipine versus magnesium sulfate

Five trials contributed data which included 556 women. There was no overall difference between nifedipine and magnesium sulfate for delivery within 48 hours of treatment, or before 34 or 37 weeks of gestation, gestational age at birth or in time from trial entry to delivery (Table 4). Nifedipine was associated with a significant reduction in maternal adverse events (23.5% vs 35.6%; RR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.48–0.82; I2=48.0%; NNT for benefit, 8; 95% CI, 5–19). In addition, one trial47 reported that severe maternal adverse effects were significantly less frequent among women receiving nifedipine than among women receiving magnesium sulfate (10.0% vs 21.7%; RR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.23–0.93).

TABLE 4.

Acute tocolysis: nifedipine compared with magnesium sulfate, atosiban, and nitric oxide donors

| Outcome | No of trials | Number of events/total number or Total number | Relative risk or Mean difference (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nifedipine | Other tocolytic | ||||

| NIFEDIPINE COMPARED WITH MAGNESIUM SULFATE | |||||

| Pregnancy outcomes | |||||

| Delivery within 48 hours of treatment | 443,45–47 | 41/230 | 53/236 | 0.84 (0.60, 1.18) | 0 |

| Preterm birth <34 weeks’ gestation | 343,44,46 | 57/146 | 60/144 | 0.99 (0.76, 1.29) | 0 |

| Preterm birth <37 weeks’ gestation | 343,44,47 | 93/189 | 92/173 | 0.94 (0.77, 1.14) | 0 |

| Pregnancy prolongation (days) | 144 | 50 | 40 | −5.8 (−18.6, 7.0) | NA |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 243,47 | 139 | 133 | −0.1 (−0.9, 0.7) | 19 |

| Maternal adverse drug reaction | 443,45–47 | 54/230 | 84/236 | 0.63 (0.48, 0.82) | 48 |

| Severe maternal adverse drug reaction | 147 | 10/100 | 20/92 | 0.46 (0.23, 0.93) | NA |

| Discontinuation of treatment because of adverse effects | 243,45 | 0/73 | 4/81 | 0.12 (0.01, 2.10) | NA |

| Perinatal and neonatal outcomes | |||||

| Birthweight (grams) | 443,45–47 | 240 | 250 | −5.6 (−67.5, 56.4) | 0 |

| Apgar score at 5 minutes | 343,45,46 | 130 | 144 | 0.0 (−0.4, 0.4) | 0 |

| Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes | 144 | 7/50 | 6/40 | 0.93 (0.34, 2.56) | NA |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 244,47 | 26/160 | 28/146 | 0.87 (0.54, 1.40) | 0 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 147 | 2/110 | 3/106 | 0.64 (0.11, 3.77) | NA |

| Neonatal sepsis | 147 | 3/110 | 5/106 | 0.58 (0.14, 2.36) | NA |

| Perinatal mortality | 343,44,47 | 3/199 | 1/187 | 1.71 (0.37, 7.88) | 0 |

| Fetal death | 343,44,47 | 1/199 | 0/187 | 2.41 (0.10, 57.65) | NA |

| Neonatal death | 343,44,47 | 2/199 | 1/187 | 1.51 (0.26, 8.74) | 36 |

| Admission to NICU | 147 | 41/110 | 55/106 | 0.72 (0.53, 0.97) | NA |

| NICU stay (days) | 245,47 | 144 | 146 | −2.2 (−3.4, −1.1) | 42 |

| NIFEDIPINE COMPARED WITH ATOSIBAN | |||||

| Delivery within 48 hours of treatment | 148 | 10/40 | 7/40 | 1.43 (0.60, 3.38) | NA |

| Delivery within 7 days of treatment | 148 | 14/40 | 10/40 | 1.40 (0.71, 2.77) | NA |

| Maternal adverse drug reaction | 148 | 16/40 | 7/40 | 2.29 (1.06, 4.95) | NA |

| NIFEDIPINE COMPARED WITH OXIDE NITRIC DONORS (NITROGLYCERIN) | |||||

| Delivery within 48 hours of treatment | 149 | 3/24 | 4/26 | 0.81 (0.20, 3.26) | NA |

| Maternal adverse drug reaction | 149 | 5/24 | 9/26 | 0.60 (0.23, 1.54) | NA |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

There were no significant differences between the groups in the risk of major adverse neonatal outcomes, although a significant reduction was seen in the risk of admission to NICU (37.3% vs 51.9%; RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.53–0.97; NNT for benefit, 7; 95% CI, 4–69) and NICU length of stay (WMD, −2.2 days; 95% CI, −3.4 to −1.1; I2=42.0%) in the nifedipine group compared with the magnesium sulfate group.

3. Nifedipine versus atosiban

This comparison included 1 trial48 involving only 40 women in each group. No difference was shown for the risk of delivery within 48 hours of treatment (25.0% vs 17.5%; RR, 1.43; 95% CI, 0.60–3.38) or within 7 days (35.0% vs 25.0%; RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 0.71–2.77) for women receiving nifedipine compared with atosiban. Maternal side effects secondary to study medication were significantly more common among women allocated to nifedipine rather than atosiban (40% vs 17.5%; RR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.06–4.95).

4. Nifedipine versus nitric oxide donors

There was only 1 trial49 that compared these two agents, involving a total of 50 women. No statistically significant differences were found between nifedipine and transdermal nitroglycerin for delivery within 48 hours of treatment or maternal adverse drug reaction.

Table 5 displays the sensitivity analysis for the comparison of nifedipine with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists and magnesium sulfate in acute tocolysis. The effects of nifedipine on reduction of delivery within 7 days of initiation of treatment and before 34 weeks of gestation, maternal adverse drug reaction, discontinuation of treatment because of adverse effects, respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, intraventricular hemorrhage, neonatal jaundice, admission to NICU, and NICU length of stay did not change after sensitivity analysis limited to trials with high methodological quality (modified Jadad score ≥6). However, the increase in gestational age at birth for women receiving nifedipine compared with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists was not demonstrated after the sensitivity analysis (WMD, 0.6 weeks; 95% CI, 0.0–1.2; I2=0.0%). Additional sensitivity and subgroup analyses for the comparison of nifedipine with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists and magnesium sulfate in acute tocolysis showed that estimates of effect sizes varied to some degree depending on the definition of preterm labor used and use of maintenance therapy, but the CIs were wide and tests for interaction were not statistically significant (data not shown). In addition, univariable meta-regression analyses indicated no association between effect sizes and study characteristics considered.

TABLE 5.

Acute tocolysis: Sensitivity analysis including only studies with high methodological quality (modified Jadad score ≥6)

| Outcome | No of trials | Number of events/total number or Total number | Relative risk or Mean difference (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nifedipine | β2-agonists | ||||

| NIFEDIPINE COMPARED WITH β2-ADRENERGIC-RECEPTOR AGONISTS | |||||

| Delivery within 48 hours of treatment | 828,32–34,37,39,41,42 | 83/397 | 78/394 | 1.00 (0.76, 1.31) | 48 |

| Delivery within 7 days of treatment | 628,32,33,37,39,42 | 106/292 | 122/274 | 0.81 (0.66, 0.98) | 31 |

| Preterm birth <34 weeks’ gestation | 432,33,37,42 | 106/220 | 122/202 | 0.79 (0.67, 0.94) | 0 |

| Preterm birth <37 weeks’ gestation | 528,32,34,37,39 | 137/238 | 131/232 | 1.01 (0.88, 1.17) | 26 |

| Pregnancy prolongation (days) | 629,30,32,34,37,39 | 258 | 250 | 5.8 (1.8, 9.9) | 49 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 530,32,33,37,39 | 237 | 220 | 0.6 (0.0, 1.2) | 0 |

| Maternal adverse drug reaction | 628,32,37,39,41,42 | 54/339 | 175/344 | 0.28 (0.15, 0.53) | 78 |

| Discontinuation of treatment because of adverse effects | 928–30,32–34,37,39,42 | 1/374 | 31/355 | 0.11 (0.04, 0.31) | 0 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 630,32,33,34,37,39 | 263 | 246 | 139.9 (13.9, 265.8) | 48 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 928–30,32–34,37,39,42 | 44/374 | 61/354 | 0.67 (0.47, 0.94) | 0 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 530,32,37,39,42 | 1/250 | 8/235 | 0.21 (0.05, 0.94) | 0 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 428,32,37,42 | 23/221 | 38/210 | 0.58 (0.36, 0.91) | 0 |

| Neonatal jaundice | 230,32 | 51/118 | 66/109 | 0.73 (0.57, 0.93) | 48 |

| Admission to NICU | 729,30,32–34,37,42 | 84/302 | 99/282 | 0.77 (0.62, 0.96) | 18 |

| NICU stay (days) | 230,42 | 71 | 62 | −7.2 (−11.2, −3.3) | 0 |

| NIFEDIPINE COMPARED WITH MAGNESIUM SULFATE | |||||

| Delivery within 48 hours of treatment | 147 | 8/100 | 7/92 | 1.05 (0.40, 2.78) | NA |

| Preterm birth <34 weeks’ gestation | 144 | 10/50 | 8/40 | 1.00 (0.44, 2.30) | NA |

| Preterm birth <37 weeks’ gestation | 244,47 | 70/150 | 68/132 | 0.91 (0.72, 1.16) | 0 |

| Pregnancy prolongation (days) | 144 | 50 | 40 | −5.8 (−18.6, 7.0) | NA |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 147 | 100 | 92 | 0.2 (−0.7, 1.1) | NA |

| Maternal adverse drug reaction | 147 | 34/100 | 60/92 | 0.52 (0.38, 0.71) | NA |

| Severe maternal adverse drug reaction | 147 | 10/100 | 20/92 | 0.46 (0.23, 0.93) | NA |

| Admission to NICU | 147 | 41/110 | 55/106 | 0.72 (0.53, 0.97) | NA |

| NICU stay (days) | 147 | 110 | 106 | −4.6 (−8.3, −0.9) | NA |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

Maintenance tocolysis

1. Nifedipine versus placebo or no treatment

Three trials, which recruited 215 women, were included. No significant differences were seen between nifedipine maintenance therapy and placebo or no treatment for preterm birth before 34 or 37 weeks of gestation, gestational age at birth, episodes of recurrent preterm labor, and adverse neonatal outcomes. Nifedipine was associated with a significant increase in pregnancy prolongation (WMD, 6.3 days; 95% CI, 1.2–11.4; I2=22.0%) (Table 6). Outcomes were similar for subgroup of women enrolled at less than 32 weeks of gestation.

TABLE 6.

Maintenance tocolysis: nifedipine compared with placebo/no treatment

| Outcome | No of trials | Number of events/total number or Total number | Relative risk or Mean difference (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nifedipine | Placebo/no treatment | ||||

| Pregnancy outcomes | |||||

| Preterm birth <34 weeks’ gestation | 150 | 12/37 | 9/37 | 1.33 (0.64, 2.78) | NA |

| Preterm birth <37 weeks’ gestation | 350–52 | 59/107 | 69/108 | 0.87 (0.69, 1.08) | 32 |

| Pregnancy prolongation (days) | 350–52 | 107 | 108 | 6.3 (1.2, 11.4) | 22 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 350–52 | 107 | 108 | 0.7 (−0.7, 2.1) | 66 |

| At least 1 episode of recurrent preterm labor | 250,51 | 16/69 | 20/68 | 1.19 (0.19, 7.30) | 66 |

| More than 1 episode of recurrent preterm labor | 251,52 | 21/70 | 18/71 | 1.21 (0.72, 2.03) | 15 |

| Perinatal and neonatal outcomes | |||||

| Birthweight (grams) | 350–52 | 125 | 120 | −29.4 (−209.1, 150.4) | 0 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 250,51 | 7/77 | 9/77 | 0.78 (0.31, 1.98) | 0 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 250,51 | 2/77 | 1/77 | 1.67 (0.23, 12.33) | 0 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 250,51 | 2/77 | 3/77 | 0.71 (0.14, 3.54) | 30 |

| Neonatal sepsis | 151 | 2/40 | 1/40 | 2.00 (0.19, 21.18) | NA |

| Neonatal death | 151 | 0/40 | 2/40 | 0.20 (0.01, 4.04) | NA |

| Admission to NICU | 250,51 | 22/77 | 19/77 | 1.16 (0.68, 1.96) | 0 |

| NICU stay (days) | 350–52 | 125 | 120 | −0.3 (−2.1, 1.4) | 0 |

| Preterm birth <34 weeks’ gestation among women enrolled at <32 weeks’ gestation | 150 | 8/25 | 8/24 | 0.96 (0.43, 2.15) | NA |

| Preterm birth <37 weeks’ gestation among women enrolled at <32 weeks’ gestation | 250,52 | 34/50 | 38/52 | 0.93 (0.72, 1.20) | 0 |

| Pregnancy prolongation (days) among women enrolled at <32 weeks’ gestation | 350–52 | 66 | 75 | 11.0 (−2.1, 24.2) | 73 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) among women enrolled at <32 weeks’ gestation | 250,52 | 50 | 52 | 0.2 (−1.2, 1.6) | 0 |

| Birthweight among women enrolled at <32 weeks’ gestation | 150 | 25 | 24 | 122.0 (−308.0, 552.0) | NA |

| Admission to NICU among women enrolled at <32 weeks’ gestation | 150 | 5/25 | 6/24 | 0.80 (0.28, 2.28) | NA |

CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

All funnel plots showed no asymmetry, either visually or in terms of statistical significance (P>.10 for all, by Egger test).

COMMENT

In this metaanalysis we found no significant differences between nifedipine and both β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists and magnesium sulfate in reducing the risk of delivering within 48 hours of initiation of treatment and before 37 weeks of gestation. However, when compared with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists, nifedipine was associated with a significant reduction in preterm birth within 7 days of initiation of treatment and before 34 weeks of’ gestation (approximately 20%) which led to significant improvements in clinically important neonatal outcomes such as respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, intraventricular hemorrhage, neonatal jaundice, admission to NICU, and length of stay in NICU. Moreover, nifedipine was less likely than β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists and magnesium sulfate to cause maternal adverse events, and its use was associated with a significant decrease in discontinuation of treatment because of adverse events when compared with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists. There were no significant differences between children exposed in utero to either nifedipine or β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists in neurodevelopmental status at 2 years of age or psychosocial and motor functioning at 9–12 years of age. The paucity of trials precluded drawing conclusions about comparisons between nifedipine and atosiban or nitric oxide donors for acute tocolysis. Maintenance tocolysis with nifedipine was ineffective in prolonging gestation or reducing any adverse neonatal outcomes when compared with placebo or no treatment.

The strength of our findings is based on the use of the most rigorous methodology for performing a systematic review of randomized controlled trials, a broad literature search, the inclusion of a relatively large number of studies in meta-analyses, the study quality assessment which was based on a widely used and validated scale, the relatively narrow confidence intervals obtained which made our results more precise, the evidence of clinical and statistical homogeneity in the results of the trials for most of the outcomes evaluated, the sensitivity analyses restricted to high quality trials that were consistent with (and thus supportive of) our overall findings, the subgroup and meta-regression analyses that failed to show any significant influence of study characteristics on effect size, and the symmetrical funnel plots that suggested absence of publication and related biases in our meta-analyses.

Our study also has some limitations. First, no placebo-controlled trial has studied the efficacy and safety of nifedipine for acute tocolysis in preterm labor. Compared with placebo, β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists reduced the risk of delivery within 48 hours of initiation of treatment (RR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.53–0.75) and within 7 days of treatment (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.68–0.90).7 Since the present metaanalysis has showed that nifedipine is as effective as β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists to reduce risk of delivery within 48 hours, and more effective to reduce risk of delivery within 7 days of treatment with a significantly better adverse-event profile, it is unlikely that a placebo-controlled trial involving nifedipine in acute tocolysis will be performed. Second, only half of the trials included herein were considered of high-quality and just one was double-blind. Nevertheless, sensitivity analyses restricted to high quality trials showed no significant differences with overall meta-analyses. In addition, assessment and measurement of most outcomes included in our review are considered objective in nature and thereby, not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. Third, several studies failed to report results on some outcome measures considered in our review. Thus, our metaanalysis may be underpowered for some outcomes and it is possible that if these results were reported more consistently, effect sizes might be different. Finally, we could not fully address the potential for performance bias by extracting consistent data on concomitant co-interventions. The difference in frequency of use and/or type of alternative tocolytic therapy between groups could have increased the apparent benefit of nifedipine compared with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists.

We were unable to determine the efficacy of nifedipine for acute tocolysis in women with twin pregnancies or with preterm premature rupture of membranes due to a paucity of data. Two studies31,33 reported data for women with twin pregnancies (N=35) and two28,33 reported data for women with premature rupture of membranes (N=58). There were no statistically significant differences between nifedipine-treated and ritodrine-treated groups for delivery within 48 hours and 7 days of initiation of treatment, and preterm birth before 34 and 36 weeks of gestation.

Some serious adverse effects such as myocardial infarction,55,56 severe maternal dyspnea,57 maternal hypoxia,58 severe maternal hypotension with fetal death,59 and atrial fibrillation60 have been reported during tocolytic therapy with nifedipine. A case series study reported that six out of seven cases of nifedipine-associated severe maternal dyspnea occurred in women with twin pregnancies and recommended caution when administering nifedipine to patients with compromised cardiovascular function, mainly those with a twin gestation, cardiac disease, maternal hypertension, and intrauterine infection.57 A recent multicenter prospective cohort study from the Netherlands and Belgium, in which an independent panel evaluated the recorded adverse events without knowledge of the type of tocolytic used, reported that among 542 women treated with nifedipine, five (0.9%) had a serious adverse side effect and six (1.1%) had a mild adverse side effect.61 In our review, nifedipine was associated with a significant decreased risk in maternal adverse effects when compared with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists and magnesium sulfate, and a significant reduction in discontinuation of treatment because of adverse effects when compared with β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists. Moreover, nifedipine had no effects on fetal and neonatal death. However, consideration of randomized control trials alone is insufficient to determine the range and severity of adverse events and both, observational studies and case reports, must be employed to assess safety data. Recently, Khan et al.62 published a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and case series which evaluated the feto-maternal safety of calcium channel blockers when used in pregnancy, no just for the treatment of preterm labor but also for use in the treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. These authors reported that adverse events were highest among women who received more than 60 mg total dose of nifedipine (odds ratio, 3.78; 95% CI, 1.27–11.2) and in reports from case series compared to controlled studies (odds ratio, 2.45; 95% CI, 1.17–5.15).

The ideal tocolytic agent should be myometrium-specific, easy to administer, inexpensive, effective in preventing preterm birth and improve neonatal outcomes, with few maternal, fetal, and neonatal side effects, and without long-term adverse effects. Since nifedipine meets most of these requirements, it should be considered as a first-line agent in the management of preterm labor. In addition, a cost-decision analysis of 4 tocolytic drugs (indomethacin, magnesium sulfate, nifedipine, and terbutaline) based on safety and cost found that nifedipine and indomethacin are the most cost-effective tocolytics used in the United States.63 The optimal dose of nifedipine for the treatment of preterm labor is yet to be determined. In most studies included in our review, the initial dose was 10 mg orally or sublingually. If contractions persisted, this dose was repeated every 15–20 minutes up to a maximal total dose of 40 mg during the first hour of treatment. Then, 20 mg orally every 6–8 hours for 2–3 days.

In summary, nifedipine appears to be a more effective tocolytic agent than β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists with improvement in neonatal outcomes, and it is better tolerated than β2-adrenergic-receptor agonists and magnesium sulfate. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to justify the routine use of nifedipine as long-term maintenance tocolytic after an episode of preterm labor. Further adequately powered studies are needed to assess the optimal dose of nifedipine, its efficacy and safety in women with multiple gestations, premature rupture of membranes, and lower gestational ages, its effectiveness as maintenance therapy after preterm labor has been arrested, the cost-effectiveness of intervention, and the long term consequences of exposure for infants. We were not able to compare efficacy and safety of nifedipine and atosiban because of the paucity of data.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Reprints will not be available

References

- 1.Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:31–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.062554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heron M, Sutton PD, Xu J, Ventura SJ, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2007. Pediatrics. 2010;125:4–15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raju TN. Epidemiology of late preterm (near-term) births. Clin Perinatol. 2006;33:751–63. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371:261–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologist. Number 43, May 2003. Management of preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1039–47. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00395-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anotayanonth S, Subhedar NV, Garner P, Neilson JP, Harigopal S. Betamimetics for inhibiting preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;4:CD004352. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004352.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Doyle LW. Magnesium sulphate for preventing preterm birth in threatened preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;4:CD001060. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King J, Flenady V, Cole S, Thornton S. Cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibitors for treating preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD001992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001992.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero R, Sibai BM, Sanchez-Ramos L, et al. An oxytocin receptor antagonist (atosiban) in the treatment of preterm labor: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with tocolytic rescue. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1173–83. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.95834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornton S, Goodwin TM, Greisen G, Hedegaard M, Arce JC. The effect of barusiban, a selective oxytocin antagonist, in threatened preterm labor at late gestational age: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:627.e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duckitt K, Thornton S. Nitric oxide donors for the treatment of preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD002860. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodd JM, Crowther CA, Dare MR, Middleton P. Oral betamimetics for maintenance therapy after threatened preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;1:CD003927. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003927.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowther CA, Moore V. Magnesium for preventing preterm birth after threatened preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000940. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valenzuela GJ, Sanchez-Ramos L, Romero R, et al. Maintenance treatment of preterm labor with the oxytocin antagonist atosiban. The Atosiban PTL-098 Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1184–90. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.105816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsatsaris V, Papatsonis D, Goffinet F, Dekker G, Carbonne B. Tocolysis with nifedipine or beta-adrenergic agonists: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:840–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King JF, Flenady V, Papatsonis D, Dekker G, Carbonne B. Calcium channel blockers for inhibiting preterm labour; a systematic review of the evidence and a protocol for administration of nifedipine. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43:192–8. doi: 10.1046/j.0004-8666.2003.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simhan HN, Caritis SN. Prevention of preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:477–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King JF, Flenady VJ, Papatsonis DN, Dekker GA, Carbonne B. Calcium channel blockers for inhibiting preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD002255. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaunekar NN, Crowther CA. Maintenance therapy with calcium channel blockers for preventing preterm birth after threatened preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;3:CD004071. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004071.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. Version 5.0.2 [updated September 2009] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analyses detected by a simple graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317:1309–12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Read MD, Wellby DE. The use of a calcium antagonist (nifedipine) to suppress preterm labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;93:933–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1986.tb08011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferguson JE, 2nd, Dyson DC, Schutz T, Stevenson DK. A comparison of tocolysis with nifedipine or ritodrine: analysis of efficacy and maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:105–11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)90679-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janky E, Leng JJ, Cormier PH, Salamon R, Meynard J. A randomized study of the treatment of threatened premature labor. Nifedipine versus ritodrine [In French] J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 1990;19:478–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bracero LA, Leikin E, Kirshenbaum N, Tejani N. Comparison of nifedipine and ritodrine for the treatment of preterm labor. Am J Perinatol. 1991;8:365–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-999417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kupferminc M, Lessing JB, Yaron Y, Peyser MR. Nifedipine versus ritodrine for suppression of preterm labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:1090–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papatsonis DN, Van Geijn HP, Adèr HJ, Lange FM, Bleker OP, Dekker GA. Nifedipine and ritodrine in the management of preterm labor: a randomized multicenter trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:230–4. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koks CA, Brölmann HA, de Kleine MJ, Manger PA. A randomized comparison of nifedipine and ritodrine for suppression of preterm labor. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;77:171–6. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(97)00255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.García-Velasco JA, González González A. A prospective, randomized trial of nifedipine vs. ritodrine in threatened preterm labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1998;61:239–44. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(98)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ganla KM, Shroff SA, Desail S, Bhinde AG. A Prospective Comparison of Nifedipine and Isoxsuprine for Tocolysis. Bombay Hosp J. 1999;41:259–62. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Qattan F, Omu AE, Labeeb N. A prospective randomized study comparing nifedipine versus ritodrine for the suppression of preterm labour. Med Principles Pract. 2000;9:164–73. [Google Scholar]