Abstract

Terpene synthases (TPSs) are pivotal enzymes for the biosynthesis of terpenoids, the largest class of secondary metabolites made by plants and other organisms. To understand the basis of the vast diversification of these enzymes in plants, we investigated Selaginella moellendorffii, a nonseed vascular plant. The genome of this species was found to contain two distinct types of TPS genes. The first type of genes, which was designated as S. moellendorffii TPS genes (SmTPSs), consists of 18 members. SmTPSs share common ancestry with typical seed plant TPSs. Selected members of the SmTPSs were shown to encode diterpene synthases. The second type of genes, designated as S. moellendorffii microbial TPS-like genes (SmMTPSLs), consists of 48 members. Phylogenetic analysis showed that SmMTPSLs are more closely related to microbial TPSs than other plant TPSs. Selected SmMTPSLs were determined to function as monoterpene and sesquiterpene synthases. Most of the products formed were typical monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes that have been previously shown to be synthesized by classical plant TPS enzymes. Some in vitro products of the characterized SmMTPSLs were detected in the headspace of S. moellendorffii plants treated with the fungal elicitor alamethicin, showing that they are also formed in the intact plant. The presence of two distinct types of TPSs in the genome of S. moellendorffii raises the possibility that the TPSs in other plant species may also have more than one evolutionary origin.

Keywords: plant specialized metabolism, lycophyte, gene origin and evolution, volatiles

Terpenoids constitute the largest class of specialized (secondary) metabolites, with more than 55,000 individual compounds identified from all forms of life (1). Many terpenoids are of plant origin, and they play diverse roles in the interactions of plants with their environment (2). Terpene synthases (TPSs) are pivotal enzymes in terpenoid biosynthesis that catalyze the formation of the basic terpene skeletons from isoprenyl diphosphate precursors. In addition to plants, many species of bacteria and fungi also contain terpenoids (3) and TPSs (4–6). Microbial TPSs, however, are only distantly related to plant TPSs (7).

The presence of terpenoids in the plant kingdom has been investigated mainly in seed plants, which have been shown to produce a variety of size classes: hemiterpenes (C5), monoterpenes (C10), sesquiterpenes (C15), and diterpenes (C20). Similarly, the TPSs producing these classes can be categorized into hemiterpene synthases, monoterpene synthases, sesquiterpene synthases, and diterpene synthases, depending on the product formed. Knowledge about the evolution of TPSs, which are said to catalyze the most complex reactions in biology (8), is clearly important for understanding the evolution of terpenes and terpene diversity. Since the first functional elucidation of a plant TPS gene (9), the number of TPS genes that has been isolated and functionally characterized from various plant species has grown exponentially. All characterized plant TPSs share significant sequence similarity with each other, implying a common evolutionary origin (10, 11). Of the several seed plants with genome sequences that have been determined, including Arabidopsis, poplar, grapevine, maize, rice, and sorghum, all possess a midsize TPS gene family of ∼30–100 functional members that include genes encoding all these classes of TPSs (with the exception of hemiterpene synthases) (11). In contrast, the genome of the moss Physcomitrella patens, the first nonseed plant to have its genome sequence determined (12), contains a single functional TPS gene encoding copalyl diphosphate synthase/kaurene synthase (CPS/KS). The P. patens CPS/KS (PpCPS/KS) is a bifunctional diterpene synthase catalyzing the consecutive reactions of geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) to copalyl diphosphate (CPP) and then CPP to ent-kaurene and ent-16α-hydroxykaurene (13).

Previous analysis of TPS gene structure and phylogeny led to the hypothesis that the ancestor of this gene class in plants is a diterpene synthase gene (14), likely resembling PpCPS/KS (11). Monoterpene and sesquiterpene synthases are shorter than diterpene synthases and have been hypothesized to have evolved from the ancestral diterpene synthase gene through the loss of an N-terminal domain (14, 15). The presence of a single diterpene synthase gene in P. patens on the one hand and several classes of TPSs in seed plants on the other hand raises the intriguing question of what evolutionary changes account for the vastly increased number and diversity of TPS genes in seed plants. To gain insight into this question, we chose to study the TPS family in Selaginella moellendorffii, a plant belonging to the lycophytes, which together with the euphyllophytes (ferns and seed plants), are the two surviving lineages of vascular plants. The critical position of S. moellendorffii in plant phylogeny and the recent determination of its genome sequence (16) make it a useful model system for understanding the evolution of plant TPSs.

Results

Identification of Two Distinct Types of TPSs in the S. moellendorffii Genome.

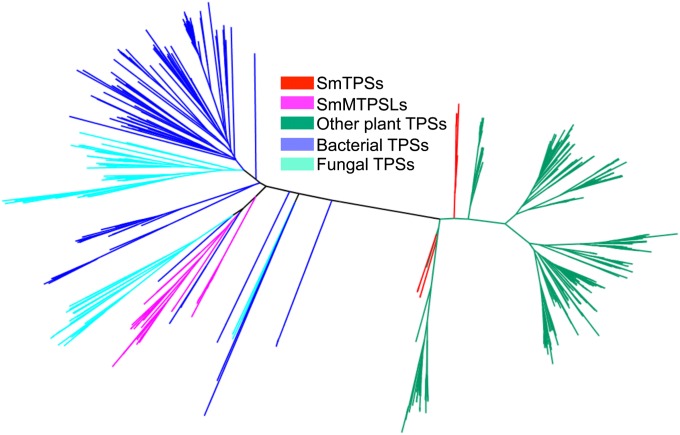

A thorough search of the S. moellendorffii genome sequence led to the identification of 66 TPS gene models (Table S1). Based on the phylogenetic analysis of S. moellendorffii TPSs and TPSs from other plants, bacteria, and fungi, these 66 TPSs can be divided into two groups, which we designated S. moellendorffii TPS proteins (SmTPSs) and S. moellendorffii microbial TPS-like proteins (SmMTPSLs). The SmTPS group consists of 18 members. The corresponding genes have been identified and analyzed in previous investigations of the S. moellendorffii genome sequence (11, 16). SmTPSs are closely related to typical plant TPSs (Fig. 1). However, the protein sequences of the SmMTPSLs, a group that contains 48 members, are more similar to microbial TPSs than SmTPSs and other plant TPSs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A phylogenetic tree constructed with the two types of S. moellendorffii TPSs: those TPSs similar to other plant TPSs (SmTPSs) and those TPSs with microbial TPS-like sequences (SmMTPSLs). Also depicted are TPSs from other plants (other plant TPSs) and putative TPSs identified from bacteria (bacterial TPSs) and fungi (fungal TPSs).

Differences between these two groups of S. moellendorffii TPSs are also evident in their gene structures and protein structures. The 14 putative full-length SmTPSs contain 11–14 introns and encode proteins of ∼800 aa in length (Fig. S1). In contrast, the SmMTPSL genes encode proteins of ∼350 aa in length and contain principally zero or one intron (Fig. S2). Furthermore, the proteins of the two S. moellendorffii TPS groups also exhibit differences in structure. As shown recently, TPS architecture is modular in nature and consists of one, two, or three separate domains, which are termed α, β, and γ (1). Typical seed plant diterpene synthases are composed of three domains in the order γ, β, and α (as exemplified by taxadiene synthase from the Pacific yew, Taxus brevifolia) (1), and typical seed plant monoterpene and sesquiterpene (and some diterpene) synthases are composed of two domains in the order β and α (represented by 5-epi-aristolochene synthase from tobacco) (17). In contrast, many microbial TPSs, such as pentalenene synthase from the bacterium Streptomyces UC5319 (18) and trichodiene synthase from fungus Fusarium sporotrichioides (19), contain only an α-domain. In S. moellendorffii, the SmTPSs have the structure of γ/β/α, whereas the SmMTPSLs have only the α-domain. Thus, both phylogenetic analysis and gene/protein structure analysis support the conclusion that SmMTPSLs are close relatives of microbial TPSs and only distantly related to SmTPSs and other plant TPSs.

Representative SmTPSs Encode Diterpene Synthases.

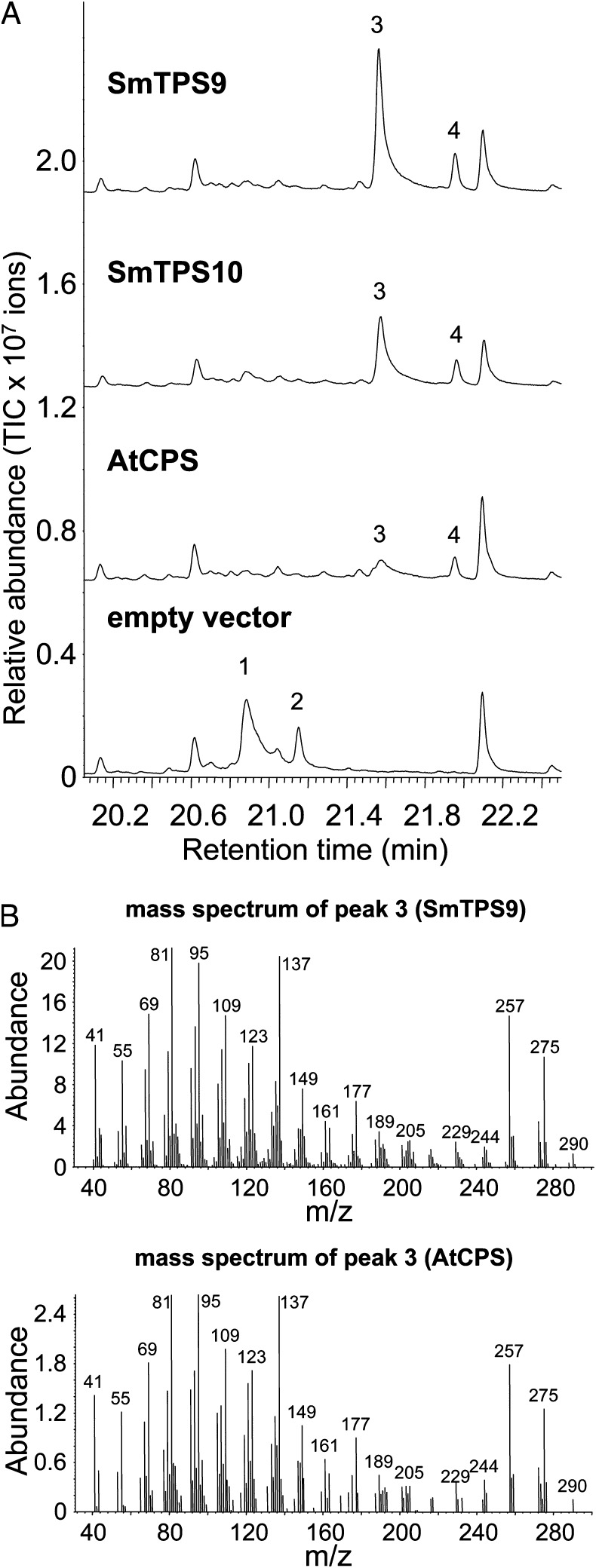

To learn more about the two groups of S. moellendorffii TPSs, their biochemical properties were investigated. Among the 18 SmTPSs, 2 SmTPSs (SmTPS7 and SmTPS4) have been recently characterized, both of which encode bifunctional diterpene synthases. Like PpCPS/KS from the moss, SmTPS7 and SmTPS4, which have been previously named as SmCPSKSL1 and SmMDS, respectively, first catalyze the formation of CPP using GGPP as substrate. These enzymes then convert CPP to λ-7,13E-dien-15-ol (20) and miltiradiene (21), respectively. To gain additional information about the catalytic functions of SmTPSs in this study, we chose to study SmTPS9 and SmTPS10, both of which contain only the DXDD and not the DDXXD motif, indicative of monofunctional diterpene synthases using GGPP as the direct substrate (13). Full-length cDNAs for SmTPS9 and SmTPS10 were isolated and expressed in Escherichia coli for the production of recombinant proteins. Both the E. coli-expressed SmTPS9 and -SmTPS10 recombinant proteins showed monofunctional diterpene synthase activity, converting GGPP to copalyl diphosphate (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

S. moellendorffii TPSs similar to other plant TPSs encode diterpene synthases. (A) Chromatograms show the gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of terpenoids produced by recombinant SmTPS9 and SmTPS10 using GGPP as substrate. AtCPS, a known copalyl diphosphate synthase from Arabidopsis, was used as a positive control. Empty vector was used as a negative control. 1, GGPP hydrolysis product 1; 2, GGPP hydrolysis product 2; 3, copalol; 4, an additional hydrolysis product of copalyl diphosphate. Copalol is the dephosphorylated product of copalyl diphosphate. The mass spectrum of peak 4 is shown in Fig. S3. (B) Mass spectrum of peak 3 from SmTPS9 and mass spectrum of copalol produced by AtCPS.

Representative SmMTPSLs Encode Monoterpene and Sesquiterpene Synthases.

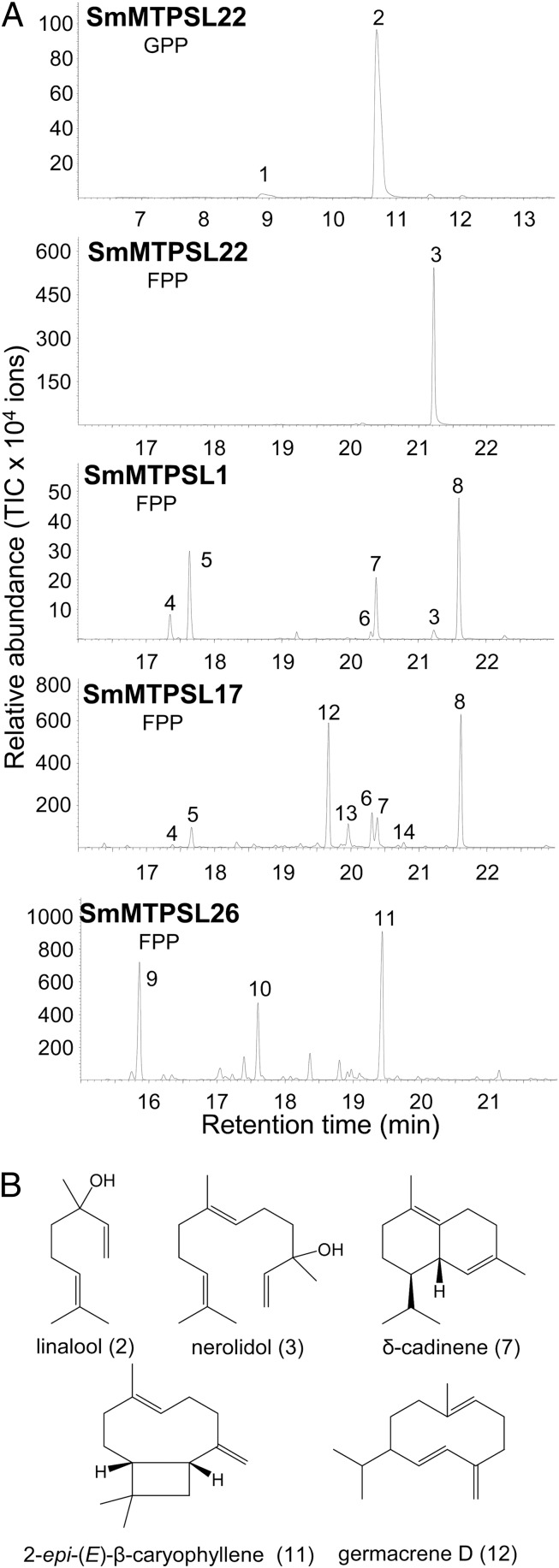

To determine whether the SmMTPSL genes encode functional enzymes and if so, whether they have similar activities to SmTPSs or very different ones, we selected a group of SmMTPSLs for biochemical characterization using in vitro enzyme assays. Full-length cDNAs for six SmMTPSL genes (SmMTPSL1, SmMTPSL13, SmMTPSL17, SmMTPSL22, SmMTPSL26, and SmMTPSL30) were isolated and expressed in E. coli for the production of recombinant proteins. The SmMTPSL1, SmMTPSL17, SmMTPSL22, and SmMTPSL26 recombinant proteins all showed sesquiterpene synthase activity in vitro with farnesyl diphosphate as substrate (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4). SmMTPSL22 catalyzed the formation of nerolidol as a single product, whereas the other three SmMTPSLs each produced multiple sesquiterpenes, which is typical of many plant sesquiterpene synthases (22). SmMTPSL1 produced six sesquiterpenes, and SmMTPSL17 produced eight sesquiterpenes, with five of the products of SmMTPSL1 also produced by SmMTPSL17. In contrast, SmMTPSL26 produced three sesquiterpene products that were specific to this enzyme. SmMTPSL22 also showed monoterpene synthase activity with geranyl diphosphate, catalyzing the formation of linalool as the major product (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4). SmMTPSL1, SmMTPSL17, SmMTPSL22, and SmMTPSL26 did not show diterpene synthase activity, and SmMTPSL13 and SmMTPSL30 did not show any TPS activity.

Fig. 3.

The microbial type of TPSs in S. moellendorffii encodes sesquiterpene and monoterpene synthases. (A) Chromatograms show the GC-MS analysis of terpenes produced by recombinant SmMTPSL22, SmMTPSL1, SmMTPSL17, and SmMTPSL26 using either geranyl diphosphate (GPP) or farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) as substrate. 1, limonene*; 2, linalool*; 3, (E)-nerolidol*; 4, α-copaene*; 5, β-elemene*; 6, γ-cadinene*; 7, δ-cadinene*; 8, unidentified oxygenated sesquiterpene; 9, unidentified sesquiterpene A; 10, unidentified sesquiterpene B; 11, 2-epi-(E)-β-caryophyllene; 12, germacrene D*; 13, bicyclogermacrene; 14, α-cadinene*. *Compounds were identified using authentic standards. All other compounds were tentatively identified based on the mass spectrum and Kovat’s retention index. Fig. S4 shows chiral analysis of linalool, nerolidol, germacrene D, and β-elemene produced by SmMTPSLs. (B) Structures of representative terpene products of SmMTPSLs.

Emission of Volatile Terpenes from Stressed S. moellendorffii Plants.

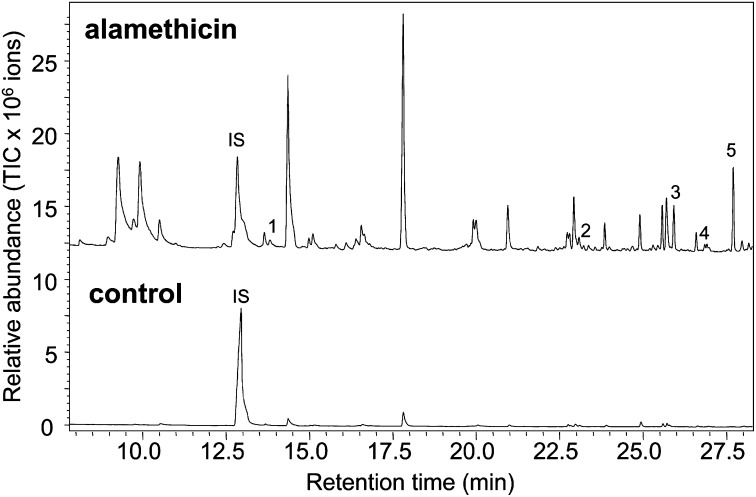

To obtain information on whether the biochemical activities of SmMTPSLs are biologically relevant, we analyzed the volatiles emitted from S. moellendorffii plants using headspace collection combined with GC-MS. Both untreated S. moellendorffii plants and plants treated with alamethicin, a fungal antibiotic that elicits defense reactions (23), were subject to analysis. Untreated plants emitted no terpenes, but a number of terpenes were detected from alamethicin-treated plants (Fig. 4), including the monoterpene linalool and the sesquiterpenes β-elemene, germacrene D, β-sesquiphellandrene, and nerolidol (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Emission of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes from S. moellendorffii plants. Chromatograms show the GC-MS analysis of the volatiles collected from the headspace of untreated S. moellendorffii plants and plants treated with a fungal elicitor alamethicin. Indicated peaks were identified to be terpenes, including the monoterpene linalool (1) and the sesquiterpenes β-elemene (2), germacrene D (3), β-sesquiphellandrene (4), and nerolidol (5). IS, internal standard.

Discussion

In this study, we report the presence of two distinct types of TPSs in S. moellendorffii. To the best of our knowledge, the presence of microbial type of TPS in a plant genome has not been reported previously. Three different lines of evidence were obtained to confirm that the SmMTPSLs are bona fide S. moellendorffii genes and not present on contaminating DNA that was sequenced together with S. moellendorffii DNA. First, most SmMTPSL genes were found to be localized in large-sized scaffolds that are integral parts of the S. moellendorffii genome (Table S1). Second, based on genome sequence annotation, all SmMTPSL genes were shown to have plant genes as neighbors (Table S2). Third, selecting SmMTPSL1 and SmMTPSL26 as representatives of SmMTPSL, we showed that a genomic DNA fragment could be amplified for each of them using PCR that covered that gene, a part of its neighboring gene, and the intergenic region. The amplicons were fully sequenced, confirming their positions in the published S. moellendorffii genomic sequence (Fig. S5).

Interestingly, both types of TPSs in S. moellendorffii are functional. As shown in this study, SmTPS9 and SmTPS10 were determined to function as copalyl diphosphate synthases (Fig. 2). As monofunctional diterpene synthases, they convert GGPP to copalyl diphosphate, which is the substrate for gibberellins or other diterpenoids. In contrast, the previously characterized SmTPS7 and SmTPS4 function as bifunctional diterpene synthases, catalyzing the consecutive reactions of GGPP to copalyl diphosphate to final terpene products (20, 21). These results indicate that S. moellendorffii contains both bifunctional and monofunctional diterpene synthases.

Selected SmMTPSLs, the microbial type TPSs, were also determined to be functional, displaying monoterpene synthase and sesquiterpene synthase activities (Fig. 3). We note that many products of the SmMTPSL enzymes that we tested, including linalool, (E)-nerolidol, α-copaene, β-elemene, γ-cadinene, δ-cadinene, 2-epi-(E)-β-caryophyllene, germacrene D, and α-cadinene, have been previously shown to be synthesized by many of the classical plant TPS enzymes (22). Some of these compounds, including linalool, germacrene D, and nerolidol, were also detected in the headspace of S. moellendorffii plants treated with the fungal elicitor alamethicin (Fig. 4), showing that these SmMTPSL products are also formed in the intact plant. Moreover, in cases where we were able to determine the chirality of the headspace compounds, they always matched the chirality obtained in the in vitro enzyme assays (Fig. S4). In addition, the expression of some SmMTPSL genes was shown to be induced by the alamethicin treatment (Fig. S6) correlating with appearance of their products, providing additional evidence that the characterized SmMTPSL proteins function as genuine TPSs in S. moellendorffii. Because the alamethicin treatment mimics pathogen infection, the emission of terpenoids from S. moellendorffii after such treatment suggests that these chemicals, like in many seed plants (24), may have a role in plant defense.

The presence of two types of TPSs with distinctive gene structures in S. moellendorffii poses intriguing questions about their evolutionary origins. The close similarity of SmTPSs to TPSs from other plants indicates that they are probably derived from a common TPS gene ancestor that was present in ancestral land plants (i.e., vertical transmission). However, SmMTPSLs are likely to have a different evolutionary origin based on their closer relationship to microbial TPSs than SmTPSs and other plant TPSs (Fig. 1). To the best of our knowledge, microbial TPS-like genes have not been found in other plant species, although so far, the only two genomes of nonseed plants available are those genomes of P. patens and S. moellendorffii. Two hypotheses can be invoked to explain the origin of SmMTPSLs. They may have been present in ancient land plants but were lost in P. patens and the seed plant lineages. Alternatively, an ancestral gene for SmMTPSLs may have been acquired by S. moellendorffii or its recent ancestor from microbes (and subsequently duplicated in the S. moellendorffii genome) through horizontal gene transfer, a mechanism where genetic material is moved across species other than by descent (25).

In summary, the data from bioinformatics approaches, phylogenetic methods, enzyme assays, and volatile metabolite analysis indicate that the S. moellendorffii genome contains two distinct groups of active TPSs, with SmTPSs functioning as diterpene synthases (Fig. 2) and SmMTPSLs functioning as monoterpene or sesquiterpene synthases (Fig. 3). Whether these conclusions hold for the rest of the S. moellendorffii TPSs awaits additional investigation. Future studies should also address the biological significance of having such a large number of SmTPS and SmMTPSL genes. Clearly, many of these genes resulted from local gene duplication, which was evidenced by their existence as tandem repeats (Table S2). However, it remains to be determined whether the maintenance of a large number of such duplicated genes in S. moellendorffii is because of random genetic drift or natural selection. Even more intriguing than the maintenance of SmMTPSLs is their evolutionary origin. Although SmMTPSLs may represent the evolutionary relics of an ancient line of TPS genes that were lost independently in the P. patens lineage and the seed plant lineages, the gain of SmMTPSLs through horizontal gene transfer is the more parsimonious explanation for the presence of microbial type TPSs in S. moellendorffii but not other plants analyzed (Fig. 1). Examination of TPSs in additional nonseed plant genomes will help distinguish between these two hypotheses.

Materials and Methods

Sequence Search and Analysis.

TPSs in S. moellendorffi and 16 other plant species (Table S3) were identified from their genome sequences using two Pfam models PF01397 and PF03936, which correspond to the two conserved domains localized at the N and C termini of known TPSs, respectively. TPSs from bacteria and fungi were identified using the Pfam model PF03936. Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using TPSs identified from S. moellendorffii, TPSs identified from the 16 plant genomes, 28 known TPSs from gymnosperms, and TPSs identified from bacteria and fungi. Maximum likelihood phylogenies were built using PhyML v3.0 and visualized using FigTree version 1.3.1. Detailed information about the species analyzed and the procedure for sequence analysis is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Gene Cloning.

S. moellendorffii plants of ∼15 cm in height were subject to treatment with a fungal elicitor alamethicin. After 24 h, above-ground parts of the plants were detached and used for RNA extraction. Full-length cDNAs for selected SmTPS and SmMTPSL genes were amplified by RT-PCR and cloned into a protein expression vector pEXP5-CT/TOPO from Invitrogen.

Terpene Synthase Enzyme Assays.

The catalytic activity of E. coli-expressed recombinant SmMTPSLs and SmTPSs was performed by using substrates geranyl diphosphate, farnesyl diphosphate, and geranylgeranyl diphosphate. Terpene products were identified using GC-MS. The detailed procedure for TPS enzyme assays is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Headspace Analysis.

Headspace collection and volatile identification were performed as described in SI Materials and Methods. Above-ground parts of control and alamethicin-treated S. moellendorffii plants were detached and placed in a glass beaker. Volatiles emitted from S. moellendorffii samples were continuously collected by pumping air from the chamber through a SuperQ volatile collection trap. Collected volatiles were analyzed using GC-MS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Reuben Peters for providing plasmid pGGeC. This project was supported by a University of Tennessee Experimental Station Innovation Grant (to F.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. JX413782–JX413789).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1204300109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Köksal M, Jin Y, Coates RM, Croteau R, Christianson DW. Taxadiene synthase structure and evolution of modular architecture in terpene biosynthesis. Nature. 2011;469:116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature09628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gershenzon J, Dudareva N. The function of terpene natural products in the natural world. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:408–414. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connolly JD, Hill RA. Dictionary of Terpenoids. London: Chapman & Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cane DE, Wu Z, Oliver JS, Hohn TM. Overproduction of soluble trichodiene synthase from Fusarium sporotrichioides in Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:416–422. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cane DE, et al. Pentalenene synthase. Purification, molecular cloning, sequencing, and high-level expression in Escherichia coli of a terpenoid cyclase from Streptomyces UC5319. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5846–5857. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agger S, Lopez-Gallego F, Schmidt-Dannert C. Diversity of sesquiterpene synthases in the basidiomycete Coprinus cinereus. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:1181–1195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao R, et al. Diterpene cyclases and the nature of the isoprene fold. Proteins. 2010;78:2417–2432. doi: 10.1002/prot.22751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christianson DW. Unearthing the roots of the terpenome. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Facchini PJ, Chappell J. Gene family for an elicitor-induced sesquiterpene cyclase in tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11088–11092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.11088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohlmann J, Meyer-Gauen G, Croteau R. Plant terpenoid synthases: Molecular biology and phylogenetic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4126–4133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen F, Tholl D, Bohlmann J, Pichersky E. The family of terpene synthases in plants: A mid-size family of genes for specialized metabolism that is highly diversified throughout the kingdom. Plant J. 2011;66:212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rensing SA, et al. The Physcomitrella genome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants. Science. 2008;319:64–69. doi: 10.1126/science.1150646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi K, et al. Identification and functional analysis of bifunctional ent-kaurene synthase from the moss Physcomitrella patens. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6175–6181. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trapp SC, Croteau RB. Genomic organization of plant terpene synthases and molecular evolutionary implications. Genetics. 2001;158:811–832. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.2.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keeling CI, et al. Identification and functional characterization of monofunctional ent-copalyl diphosphate and ent-kaurene synthases in white spruce reveal different patterns for diterpene synthase evolution for primary and secondary metabolism in gymnosperms. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:1197–1208. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.151456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks JA, et al. The Selaginella genome identifies genetic changes associated with the evolution of vascular plants. Science. 2011;332:960–963. doi: 10.1126/science.1203810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starks CM, Back K, Chappell J, Noel JP. Structural basis for cyclic terpene biosynthesis by tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase. Science. 1997;277:1815–1820. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lesburg CA, Zhai G, Cane DE, Christianson DW. Crystal structure of pentalenene synthase: Mechanistic insights on terpenoid cyclization reactions in biology. Science. 1997;277:1820–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rynkiewicz MJ, Cane DE, Christianson DW. Structure of trichodiene synthase from Fusarium sporotrichioides provides mechanistic inferences on the terpene cyclization cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13543–13548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231313098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mafu S, Hillwig ML, Peters RJ. A novel labda-7,13e-dien-15-ol-producing bifunctional diterpene synthase from Selaginella moellendorffii. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:1984–1987. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugai Y, et al. Enzymatic (13)C labeling and multidimensional NMR analysis of miltiradiene synthesized by bifunctional diterpene cyclase in Selaginella moellendorffii. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42840–42847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.302703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degenhardt J, Köllner TG, Gershenzon J. Monoterpene and sesquiterpene synthases and the origin of terpene skeletal diversity in plants. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:1621–1637. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engelberth J, et al. Ion channel-forming alamethicin is a potent elicitor of volatile biosynthesis and tendril coiling. Cross talk between jasmonate and salicylate signaling in lima bean. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:369–377. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.1.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pichersky E, Gershenzon J. The formation and function of plant volatiles: Perfumes for pollinator attraction and defense. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2002;5:237–243. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keeling PJ, Palmer JD. Horizontal gene transfer in eukaryotic evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:605–618. doi: 10.1038/nrg2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.