Abstract

Study Objective

To identify sexual health behavior interventions targeting U.S. Latino adolescents.

Design

A systematic literature review.

Setting

Peer-reviewed articles published between 1993 and 2011, conducted in any type of setting.

Participants

Male and female Latino adolescents ages 11–21 years.

Interventions

Interventions promoting sexual abstinence, pregnancy prevention, sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention, and/or HIV/AIDS prevention.

Main Outcome Measures

Changes in knowledge, attitudes, engagement in risky sexual behaviors, rates of STIs, and/or pregnancy.

Results

Sixty-eight articles were identified. Fifteen were included in this review that specifically addressed Latino adolescent sexual health behavior. Among the reviewed interventions, most aimed to prevent or reduce STI and HIV/AIDS incidence by focusing on behavior change at two levels of the social ecological model: individual and interpersonal. Major strengths of the articles included addressing the most critical issues of sexual health; using social ecological approaches; employing different strategies to deliver sexual health messages; and employing different intervention designs in diverse geographical locations with the largest population of Latino communities. Most of the interventions targeted female adolescents, stressing the need for additional interventions that target Latino adolescent males.

Conclusions

Latino adolescent sexual health is a new research field with gaps that need to be addressed in reducing negative sexual health outcomes among this population. More research is needed to produce new or validate existing, age-specific, and culturally-sensitive sexual health interventions for Latino male and female adolescents. Further, this research should also be conducted in areas of the U.S. with the newest Latino migration (e.g., North Carolina).

Keywords: Adolescents, Latinos, Hispanics, Sexual health education, Teenage pregnancy, Contraception

Introduction

The incidence and prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among U.S. adolescents ages 15–24 years is alarmingly high when compared with rates among youth from other developed countries.1,2 Furthermore, these adolescents had the highest incidence of STIs in the nation, accounting for approximately half of the 19 million STI cases in 2000,3 with risky sexual behavior being linked to increased STI incidence and prevalence.4 Research suggests that lack of effective sexual health interventions may increase risks for adverse sexual health outcomes in adolescents.5 Therefore, strategies intended for preventing STIs among sexually active adolescents are needed to address promoting healthy behaviors and reducing risky sexual behaviors.6,7

Latino adolescents are the largest and fastest growing ethnic group in the U.S.; however, little attention has focused on their sexual health, which, like the sexual health of non-Latino youth, is affected by an interrelation of factors at different social ecological levels– individual, interpersonal, community, and societal.8,9

Adolescent sexual health is affected by the social contexts in which these individuals live; therefore, consideration of adolescents’ ethnic, racial, and cultural background is important when addressing sexual risk-taking behavior.9 Latino adolescents’ cultural values may impact their sexual behavior including gender roles such as machismo (masculinity) and marianismo (feminity), familism, acculturation, the importance of religion, and educational goals.10 Research suggests that Latino health disparities exist and that the Latino adolescent community is at greater disadvantage with regard to reproductive health outcomes when compared to non-Latino adolescents.11,12

Differences may also exist based on gender in the sexual and reproductive health issues of Latinos. For example, female adolescents must consult reproductive health care professionals to obtain contraceptive methods, while male adolescents are not required to do so.13 Although birth rates among adolescents have declined over the last 10 years, Latina adolescents continue to have the highest birth rate of any ethnic minority group in the U.S.14 Currently, the STI rates for Latina adolescents is approximately two times higher than non-Latina White adolescents (8.93 and 4.3 per 1000, respectively). Additionally, Latina adolescents, ages 15–19 years, have significantly higher STI rates when compared to Latino male adolescents of the same age group (8.93 and 1.92 per 1,000, respectively).15

To address these disparities, studies have been conducted to better understand the cultural and socioeconomic factors that serve as determinants of or contributors to adverse Latino adolescent sexual health outcomes.16 However, these studies have, for the most part, focused on identifying the cause of the problem, while less attention was given to addressing the problem by promoting sexual health among Latino adolescents.17–20 Although a majority of national data and supporting research reflects the sexual health needs of the overall adolescent community in the U.S., limited cultural and age appropriate research exists that specifically addresses the needs of the Latino adolescents.21 Without effective and culturally relevant interventions that address Latino adolescents’ risky sexual behavior using a social ecological approach, the negative consequences of Latino adolescents’ risky sexual behaviors significantly impact their quality of life in adulthood.22

Social ecological approaches are an essential component of public health efforts aimed at improving complex community health problems like decreasing the prevalence of adolescent STIs.23 The Social Ecological Model is a multilevel framework that aids in understanding and solving complex public health issues by examining an individual’s social and physical environments.24 The model emphasizes interconnections and influencing factors on an individual’s health status and behavior and provides a framework with which to address health issues and develop interventions.25 The use of a theoretical framework like the Social Ecological Model is important for behavioral interventions, as it allows researchers and practitioners to better understand, predict, and address adolescent behaviors.26

The goal of the review reported here was to determine which behavioral interventions have been developed and implemented to promote the sexual health of Latino adolescents. Specifically, for this review, we focused on three objectives: (1) to conduct a systematic literature review to assess the quantity, quality, and effectiveness of behavioral interventions that addressed the sexual health needs of Latino adolescents; (2) to assess differences in intervention by gender; (3) to identify health interventions that used a social ecological approach. That is, those studies that illustrated multiple influential factors on Latino adolescent sexual health behavior from multiple levels within an adolescent’s environment. Based on our findings, we provide suggestions for moving the Latino adolescent health disparities research agenda forward to reduce adverse sexual health outcomes experienced by U.S. Latino adolescents.

Methods

Systematic Literature Review Strategy

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify intervention studies that promote Latino adolescent sexual health. We defined an intervention as any kind of planned activity or group of activities designed to prevent STIs/pregnancy or promote the reproductive health of Latino adolescents, about which a single summary conclusion could be drawn.27 The literature review was limited to peer-reviewed, English language journal articles. Five online databases were used to search for published behavioral interventions: CINAHL, OVID Medline(R), PsychINFO, PubMed, and Scopus. Additionally, the Academy for Educational Development and the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention’s Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions (DEBI) project were utilized in the literature search.28 All search terms used in the literature searches are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Literature Review Search Terms

| Adolescent | Sexual Behavior | Intervention | Latino |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent(s) | Sexual Behavior | Intervention(s) | Hispanic(s) |

| Adolescence | Sexual Activities | Early Intervention(s) | Hispanic American(s) |

| Teen(s) | Sexual Activity | Education | Spanish American(s) |

| Teenager(s) | Sex Behavior | Health Education | Latina(s) |

| Youth(s) | Oral Sex | Health Promotion(s) | Latino(s) |

| Female Adolescent(s) | Sexual Orientation | Promotion of Health | Puerto Rican(s) |

| Male Adolescent(s) | Sex Orientation | Prevention | Cuban American(s) |

| Premarital Sex Behavior | Wellness Program(s) | Central American(s) | |

| Anal Sex | Health Campaign(s) | South American(s) | |

| Sexually transmitted diseases | Health Service(s) | Mexican Americans | |

| HIV infection | Family Planning | Ethnic Group | |

| HIV education | Family Planning Service(s) | Minority Group | |

| Pregnancy | Family Planning Program(s) | ||

| Pregnancy during adolescence | Reproductive Health Service(s) | ||

| Preventive Health Service(s) | |||

| School Health Service(s) | |||

| School-Based Service(s) | |||

| Community Health | |||

| Community Health Service | |||

| Community Health Care | |||

| Community Healthcare | |||

| Community Health Education |

Based on results from the national Youth Risk Behavior Survey, no significant positive changes in the risky sexual behaviors of adolescents were noted from 1998 to 2009.29 Therefore, to focus on recent trends in adolescent sexual health interventions, the initial literature search only included articles from this time period. However, due to the scarcity of relevant articles based on their significance and contribution to Latino adolescent sexual health promotion, the literature search was expanded to include 18 years of research from 1993 to 2011.

Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion of Literature

The American Academy of Pediatrics considers individuals ages 11 to 21 years to be at the developmental stage of adolescence.30 Thus, for the purpose of this literature review, the target population was Latino adolescents within this age range. These are adolescents who can trace their origin or descent to Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Central and South America, and other Spanish cultures.31 Interventions that targeted the following measured outcomes were included: (1) increase in sexual health knowledge, (2) changes of sexual behavior attitudes or beliefs, (3) abstinence from or delay of sexual activity, (4) reduction in engaging in risky sexual behaviors, defined as sexual behaviors that contribute to unintended pregnancy and STIs, including HIV infection32 for those who were sexually active, (5) reduction in the number of pregnancies or repeat pregnancies, (6) reduction in incidence and prevalence of STIs, or (7) mixed outcomes (e.g., having one or more of the previously mentioned desired outcomes).

Articles were excluded if: (1) they did not target any of the aforementioned measured outcomes in sexual health; (2) the intervention did not have a sizable proportion of Latino adolescents (i.e., Latinos constituted less than 50% of the sample), unless the measured outcomes for different ethnic groups were analyzed separately; or (3) the age range of the intervention samples included both adolescents and adults (e.g., individuals older than 21 years of age). Finally, articles that reported the same information from a specific study were removed.

Data Extraction

The selection of data from behavioral intervention studies was guided by data extraction guidelines utilized in previous literature reviews of sexual health interventions for populations other than Latino adolescents.33–36 A data extraction table was created to include intervention qualities and to facilitate a comparison between reviewed interventions. Although methodological papers provided evidence of on-going research that addressed Latino adolescent sexual health information and related interventions, they did not provide available outcome data and were subsequently excluded from this literature review.

Classification of Articles

The theoretical framework was extracted from reviewed articles to classify the interventions based on the social ecological levels (i.e., the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal) that influence health behavior.24 If no theoretical framework was stated in the article, the intervention outcome measures were analyzed to identify a specific social ecological level that targeted behavior change.

Results

The literature search of articles published between 1993 and 2011 resulted in 1,768 hits for adolescent sexual health interventions conducted with Latino adolescents. Of these, 98 articles were behavioral interventions. Articles that were found in more than one database were considered duplicates, and after removing the duplicates, 68 articles remained. Of the 68 identified articles, there were 56 which did not meet the inclusion criteria because of the lack of measurable outcomes for sexual health (n = 8); had samples that included adult-age individuals (n = 21); less than 50% of the sample size consisted of Latinos (n = 14); or the intervention’s outcomes were not sexual health (n = 9). For articles that published information regarding the same intervention, only those articles that reported evaluation results were selected (n = 4). The only intervention from the 28 DEBI projects to meet the inclusion criteria was ¡Cuídate!; however, it had already been identified through the online databases of peer-reviewed journals.

Finally, 15 articles met the inclusion criteria for this review: 10 (67%) were located on Scopus, 3 (20%) on PubMed, 1 (6%) on OVID (Medline(R) and PsychINFO), and 1 (6%) on CINAHL. Publication details of articles were stored in a computer reference manager.

Quantity and Quality of Interventions Reviewed

Fifteen articles met the criteria for this review.37–51 A general description of each intervention, measured outcomes, and intervention effects on measured outcomes of each intervention is presented in Table 2. The most common desired outcome for reviewed behavioral interventions was STI or HIV/AIDS prevention (n = 8). The less frequently desired outcomes were abstinence-only (n = 1), and pregnancy prevention only (n = 1). Other interventions had mixed desired outcomes, including abstinence, pregnancy prevention, and/or STI and HIV/AIDS prevention (n = 5).

Table 2.

Details of Latino Adolescent Sexual Health Behavioral Interventions Reviewed

| Intervention | Desired Outcome | Description of Intervention | Measures of Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV Prevention Program 37 | STD/HIV/AIDS prevention | An AIDS prevention program designed to increase HIV/AIDS awareness and to reduce the risk of HIV infection by increasing the distribution and use condoms among sexually active adolescents. |

|

|

| Social Skills Training (SST)38 | STD/HIV/ AIDS prevention | An intervention focused on skills training that consisted of a curriculum of brief didactic instruction on sexual health topics and role-playing activities for development of skills (e.g., refusal of sexual activity, purchasing condoms). Videos were recorded of students’ role playing activities to evaluate students’ learned skills. |

|

|

| HIV Risk-Reduction Intervention39 | Abstinence; STD/HIV/AIDS prevention | A school-based intervention that was provided during weekly health education class, consisting of four blocks of learning experiences through group discussions and role-playing activities relating to alcohol use and its influence on sexual activity. |

|

|

| The GIG40 | Pregnancy prevention; STD/HIV/ AIDS prevention | A community-based intervention of a single session (6hrs), which offered education regarding pregnancy and STI risks and prevention in the context of a social event that featured a disc jockey, celebrities from local radio stations, live and recorded music, raffles, contests, and prizes and a number of activities providing instruction regarding pregnancy and STI risks and prevention. |

|

|

| California’s Adolescent Sibling Pregnancy Prevention Program (California’s ASPPP) 41 | Abstinence; Pregnancy prevention | A community-based intervention consisting of various programs focusing on the availability and accessibility to support services for adolescent pregnancy prevention, academic excellence, physical wellness, inspiration and empowerment for adolescents, and their families towards positive personal growth, goal attainments and self-sufficiency. |

|

|

| Project Children’s Health and Responsible Mothering (Project CHARM)42 | STD/HIV/AIDS prevention | HIV prevention program was a modified version of Be proud! Be responsible!, and was renamed to Be proud! Be responsible! Be protective! to reflect new focus on maternal protectiveness as a cause to reduce or eliminate sexual risk-taking behavior. New information incorporated HIV effects on pregnant women and their children to motivate adolescents to make responsible sexual decisions and reduce risky sexual behavior and to raise political awareness of the effects of HIV/AIDS on inner-city communities and their children. |

|

|

| Baby Think It Over43 | Pregnancy prevention | An intervention using a computerized infant simulation doll to offer adolescents experiences similar to those involved in attending to an infant. Pregnancy prevention classes were also offered in preparation for carrying a doll and a debriefing period after everyone in the class had carried a doll. | Degree to which adolescents recognize:

|

|

| Cuídate44 | STD/HIV/AIDS prevention | This intervention was an adaptation of Be Proud! Be responsible!, tailored to issues relevant to Latinos. Incorporated salient aspects of Latino culture, specifically familialism, or the importance of family, and gender-role expectations. Abstinence and condom use were presented as culturally accepted and effective ways to prevent STDs, including HIV. Also focused on health behaviors like diet, exercise, physical activity, and cigarette, alcohol, and drug use. |

|

|

| Familias Unidas + Parent Preadolescent Training for HIV Prevention (Familias Unidas + PATH)45 | STD/HIV/AIDS prevention | A family-based intervention designed to reduce risk and increase protection against substance use and sexual risk behaviors in Latino adolescents by increasing parental involvement in adolescent’s life, increasing family support, promoting positive parenting, and improving parent-adolescent communication. All activities were parent-centered, with adolescent involvement limited to family visits, and parent-adolescent discussions in the intervention group. |

|

|

| Safer Choices 246 | Pregnancy prevention; STD/HIV/AIDS prevention | Safer Choices 2 was an adaptation of Safer Choices for the particular implementation in alternative schools. Included skill-based and experiential activities to reduce levels of unprotected sexual intercourse through classroom-based lessons, video and journaling activities. |

|

|

| Couple-Focused HIV Prevention Program47 | STD/HIV/AIDS prevention | A culturally-sensitive, couple-focused HIV prevention program attended by adolescent mothers and their male partners. Builds on maternal and paternal protectiveness and integrate traditional teachings based on culturally rooted concepts and on values found in the indigenous teachings and writings of the ancestors of many Chicano, Latino, and Native American people. |

|

|

| Reducing HIV and AIDS through Prevention (RHAP)48 | STD/HIV/AIDS prevention | An intervention that uses hip-hop/rap music as a method of teaching students about HIV and AIDS awareness and prevention through the analysis of lyrical content that is conducive to risky sexual behavior. |

|

|

| Joven Noble49 | Abstinence; STD/HIV/AIDS prevention | A program model that addresses prevention of a number of risk-related sexual behaviors within cultural context. It is a youth development, support, and leadership enhancement program for ages 10–24. |

|

|

| Families Talking Together50 | Abstinence | A brief, parent-based intervention delivered to mothers of adolescents in a pediatric clinic as they wait for their child to complete a physical examination in order to reduce sexual risk behaviors among Latino and African American middle – school young adults. |

|

|

| Shero’s Program51 | STD/HIV/AIDS prevention | A community-based, culturally and ecologically tailored HIV prevention intervention for Mexican American female adolescents grounded in the AIDS risk reduction model, which is a stage model that provides insights into HIV risk reduction behavior change processes and offers recommendations for how to move people through the process of behavior change. |

|

|

Interventions were found to have fundamental differences among target audience characteristics (e.g., race, country of origin, age range, gender), sample sizes, attrition rates, experimental designs, theoretical frameworks, content of the intervention, type of facilitators, intervention duration and intensity, mode of assessment of outcomes, time span for follow-up, setting of the intervention, and geographical location of the intervention.

Target Population

Overall, the interventions’ targeted population included adolescents from ages 10 to 23 years. Eleven studies focused on broad age ranges in adolescence. Two studies focused on one specific adolescent subgroup (e.g., early, middle, or late adolescence). Seven studies had a sample representative of each adolescence stage: early, middle, and late. Two studies did not include age ranges of participants, providing only a mean age.

Interventions that included males and females constituted 80% of reviewed interventions; however, females composed the majority of the sample size (> 50%) in most of the reviewed interventions, except in the GIG, Reducing HIV and AIDS through Prevention (RHAP), and Joven Noble, where males represented 57%, 54% and 100% of the sample, respectively. Two interventions included only female adolescents, whereas only one intervention included only males.

The nation of origin of Latinos in the intervention samples was oftentimes unspecified (n = 9). However, six interventions did specify the participants’ nation of origin. Adolescents of Mexican and Puerto Rican descent were most frequently represented, followed by adolescents of Cuban descent. Two studies noted participants of Central and South American descent.

Sample Size

The sample sizes ranged from 26 to 1,594 individuals, with five studies having more than 500 participants. The majority of interventions used a convenience sample, with the exception of one which used a probability sample. Individuals were followed at different time points after the intervention, ranging from immediately after the intervention to 36 months post-intervention. Four studies conducted multiple follow-up sessions that varied by time span recorded in months.

Attrition Rates

Attrition rates were 20% or less for eight interventions, and between 21–50% for four other interventions. Two interventions did not report participation loss over the time of the intervention. Of the interventions that did report attrition rates, some reported attrition at the first of multiple follow-up sessions, and not thereafter. Furthermore, it is important to note that participant loss in some interventions with high attrition rates was partially due to the exclusion of participants from analysis and not necessarily because of discontinuation of the program (e.g., failure to correctly fill out evaluation forms or missed sessions of intervention).

Experimental Design

Five interventions used a randomized controlled trial design. Of these, four interventions used the individual as the unit of analysis. Within the randomized trial category, there was one modified group-randomized, controlled trial that identified a group of five schools as the unit of analysis. Three other interventions used a quasi-experimental design of one group, pre- and post-test.

Theoretical Framework

The majority of interventions reported a theoretical framework to guide the intervention (n = 12). The most commonly reported theory was the Social Cognitive Theory. Other theories utilized were the Theory of Planned Behavior/Theory Reasoned Action, the Ecodevelopmental Theory45 (which describes relationships with ecological factors that increase risk and protection in adolescents’ lives), and the Theory of Cognitive Development. Three interventions did not report using a theoretical framework to guide the research.

Content of the Intervention

Factual information of different topics and varied quantities was presented in all of the interventions. Recurrent areas of health knowledge outlined in the interventions were general adolescent sexuality, STI and HIV/AIDS, implications of pregnancy and infant care, maternal/paternal protectiveness for adolescent mothers or fathers, contraception, the influence of substance use on risky sexual behavior, overall health and wellness, and the importance of values, life goals, and family function.

Intervention Facilitators

The background of the individuals who coordinated or led interventions was varied by age and their professional training. For example, two of the interventions employed peer leaders as intervention facilitators, while the rest were conducted by adults from different professional backgrounds in education, nursing, social work, or other type of clinical experience (e.g., sexual health educators, psychologists).

Duration and Intensity

The number and frequency of sessions of the reviewed interventions were fairly diverse. The duration of the interventions ranged from single sessions of 30 minutes to 95 hours of multiple sessions over the course of 18 months. There were some interventions, particularly those which involved counseling services, which did not specify an exact duration of the intervention. An example is the California ASPPP–an intervention in which the participants received an average of 18 hours of treatment of one-on-one and group services ranging from 45 minutes to 95 hours per participant.

Mode of Assessment of Outcomes

The use of self-reported questionnaires was the most common assessment of intervention outcomes. These assessments were oftentimes offered in both English and Spanish, depending on the participants’ preferred language. Other forms of outcome assessment included personal interviews with intervention staff. One intervention (Social Skills Training) used a unique form of outcome assessment to evaluate behavioral skills learned by adolescent participants: videotaped standardized role-play tests that were evaluated by specially-trained staff.

Points of Assessment

Most commonly, participants were assessed at different time points before and after the intervention, ranging from six months before to 36 months after the intervention. Five studies conducted multiple follow-up sessions that varied by the time span in months. While five studies did not report timing at follow-up, post-intervention assessment activities were implied.

Setting of the Intervention

Schools (n = 10) were the most commonly used setting for program implementation. The interventions based in school settings were conducted during after-school hours, weekends, summer sessions, and at alternative schools. Other settings for conducting the interventions were community venues (e.g., community-based organizations, health service agencies, street corners, clinics), and the participants’ homes.

Geographical Location of the Intervention

The geographic location of the interventions spanned several regions of the U.S.: Boston, MA; Houston and southeast Texas; Los Angeles and San Diego, CA (as well as other unspecified California locations); Northeast Philadelphia, PA; Miami, FL, East Harlem and Bronx, NY, and an unspecified Midwestern city.

Effectiveness of Interventions

Based on their targeted measurable outcomes, the following interventions were effective in addressing the sexual health of Latino adolescents:

Reduction of Risky Sexual Behavior

Nine of 15 interventions reduced risky sexual behavior: (1) HIV Prevention Program (for females only), (2) California’s ASPPP, (3) Project CHARM, (4) Baby Think It Over, (5) ¡Cuídate!, (6) Couple-Focused HIV Prevention Program, (7) Joven Noble, (8) Families Talking Together, and (9) Shero’s Program.

Change in Attitudes, Beliefs and Perceptions about Sexual Health, STIs, Including HIV/AIDS

Eight of 15 interventions were effective in changing attitudes, beliefs and perceptions about sexual health and STIs: (1) High-Risk Reduction Intervention, (2) The GIG, (3) California’s ASPPP (For females only), (4) Baby Think It Over, (5) Familias Unidas + PATH, (6) RHAP, (7) Joven Noble, and (8) Shero’s Program.

Increase in Sexual Health Knowledge

Seven of 15 interventions were effective in increasing sexual health knowledge in participants: (1) Social Skills Training, (2) High-Risk Reduction Intervention, (3) Project CHARM, (4) Couple-Focused HIV Prevention Program, (5) RHAP, (6) Joven Noble, and (7) Shero’s Program.

Promotion of Sexual Abstinence or Delay of Sexual Activity

Five of 15 interventions were effective in promoting of sexual abstinence or delaying of sexual activity: (1) High-Risk Reduction Intervention (for males only), (2) California’s ASPPP (for females only), (3) Project CHARM, (4) ¡Cuídate!, and (5) Joven Noble.

Increase in skills-based learning

Three interventions were effective in increasing skills-based learning: (1) Social Skills Training, (2) California’s ASPPP (for females only), and (3) Shero’s Program.

Reduction of Incidence and Prevalence of STIs, Pregnancy or Repeat Pregnancy Rates

California’s ASPPP was the only intervention that measured incidence and prevalence of STI and pregnancy rates, and it was also effective in reducing these rates among female participants.

Increase in level of family functioning

Familias Unidas + PATH and Families Talking Together were the only two interventions that involved families (i.e., parents or guardians); however, only Familias Unidas + PATH specifically measured and increased the level of family functioning.

Classification of Interventions Based on the Social Ecological Model

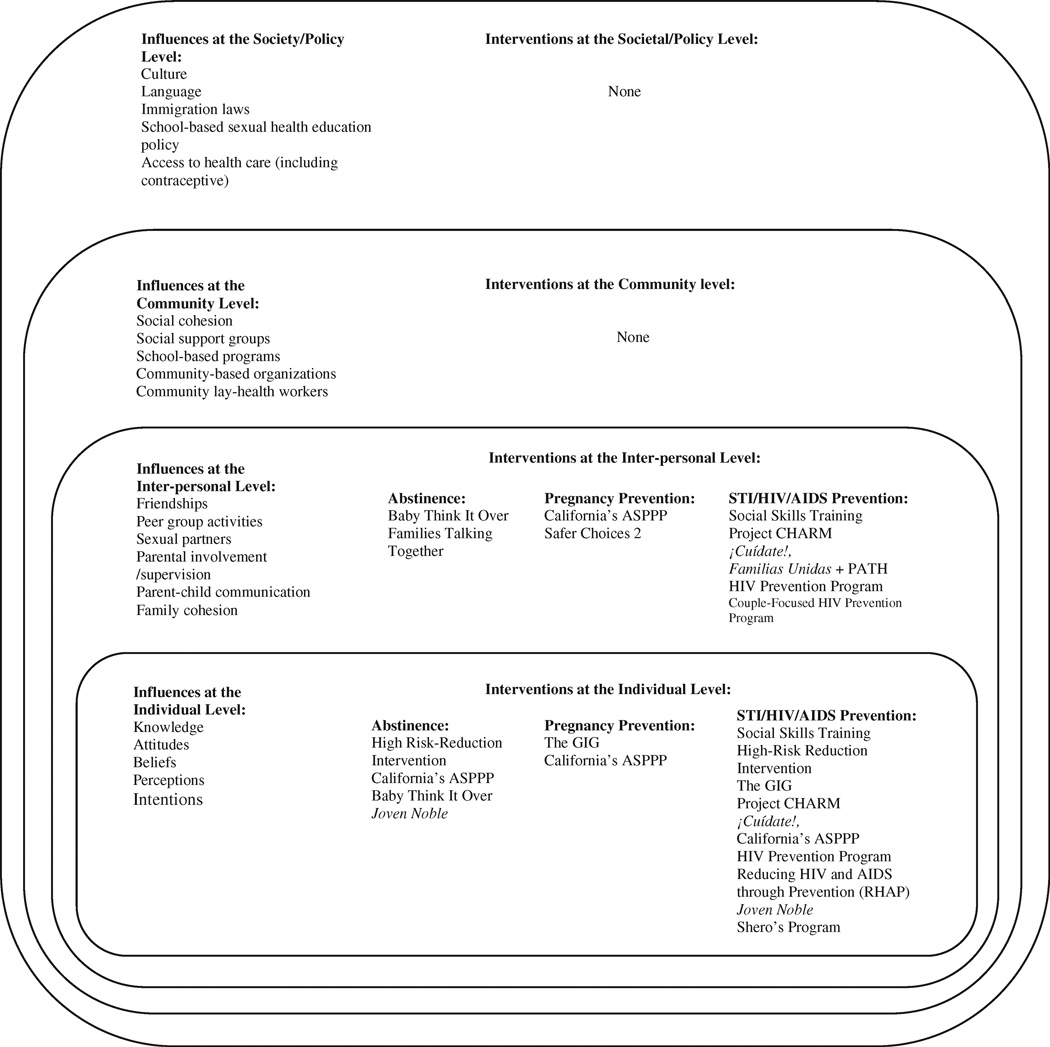

Interventions identified through this literature review were classified by levels of influence on sexual behavior of adolescents based on the Social Ecological Model (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Social Ecological model of influential factors and interventions from the literature review that affect Latino adolescent sexual health.

Interventions at the individual level

The majority of interventions addressed individual level factors associated with U.S. Latino adolescent sexual health. Theories applied at this level were the Theory of Planned Behavior40 and the Theory of Reasoned Action.41 Another theory employed at this level was the Theory of Cognitive Development42 particularly at the Formal Operational Stage; where an individual’s ability to think hypothetically about the consequences of actions (e.g., becoming an adolescent parent as a consequence of risky sexual behavior) are gauged.

Interventions at the Interpersonal Level

The Social Cognitive Theory43 emerged as the most commonly used theory among the Latino adolescent sexual health behavioral interventions. The effective interventions at this level were Project CHARM, ¡Cuídate!, Couple-Focused HIV Prevention Program, and Families Talking Together, which helped build skills in successfully handling interactions between individuals and their peers, sexual partners, and family members. Examples of these skills included self-efficacy in refusing sexual activity, decreasing number of sexual partners, negotiating condom use with sexual partners, increased sense of adolescent-maternal protectiveness to reduce risky sexual behavior, and effective parent-adolescent communication about sexual topics.

The Familias Unidas + PATH intervention was partially successful; its goals in increasing family functioning and parent-child communications were met, but the intervention did not decrease risky sexual behavior in adolescents. The Social Skills Training intervention was also partially successful, as it increased negotiation skills, but failed to successfully meet other skills-based desired outcomes such as refusal of unprotected sex, and self-efficacy in obtaining or purchasing condoms. The article did not report the use of a theoretical framework; however, its activities were specifically focused on skills-based learning at the interpersonal level. Interventions that addressed abstinence at the interpersonal level included Baby Think It Over and Joven Noble by promoting a broader view of the impact of adverse sexual health outcomes on the lives of family members (e.g., parents of parenting adolescents, children of adolescents). Moreover, interventions that addressed pregnancy prevention were California’s ASPPP and Safer Choices 2.

Interventions at the Community or Societal Levels

None of the interventions reviewed were conducted at the community or societal levels to target community, neighborhood, or social norms or even changes in policies and regulations.

Discussion

The findings from this literature review suggest that over time, very few articles systematically evaluated behavioral interventions that specifically addressed Latino adolescent sexual health. Based on results from this literature review, there are several strengths and weaknesses of the research to prevent negative outcomes in the sexual health among U.S. Latino adolescents.

Strengths of Behavioral Intervention Research Addressing Latino Adolescent Sexual Health

We discovered five major strengths in the Latino adolescent sexual health research agenda. First, interventions have addressed the three most critical issues in adolescent sexual health: abstinence, unintended pregnancies, and STIs.1 Second, interventions’ problem-solving approach has been aimed at different social ecological levels in order to effect change in the negative sexual health outcomes of Latino adolescents. For example, while some interventions targeted change in the individual’s perceptions, attitudes, and knowledge about sexual health, other interventions targeted interpersonal relationship skills that affect sexual behavior. Third, interventions used different strategies (e.g., lectures, discussions, role playing, and home visits) and settings (e.g., schools, neighborhood streets, and health clinics) to deliver sexual health messages to adolescents. Fourth, there were a variety of intervention designs (e.g., randomized controlled trials, one group pre/post-test design, and quasi-experimental design). A fifth strength was the diversity of geographical locations within the United States where the interventions were conducted, which included cities with the largest concentration of Latino communities (e.g., Miami, FL; Los Angeles, CA; and Houston, TX).

Weaknesses of Behavioral Interventions Research Addressing Latino Adolescent Sexual Health

Numerous weaknesses were noted in the research conducted to impact Latino adolescents’ sexual health. One major weakness was the paucity of behavioral interventions that specifically targeted and promoted Latino adolescent sexual health. Another weakness was the lower percentage of sexual health interventions for Latino adolescents that addressed sexual health problems from a social ecological approach, targeting multiple levels of influence. The majority of interventions focused on STI and HIV/AIDS prevention at the individual level. Furthermore, interventions, for the most part, targeted females with less attention focused on the male’s role in a sexual relationship, as well as other levels of influence that determine the health of female adolescents. By having the highest teen pregnancy and birth rates among all ethnic minority groups, Latino male and female adolescents require interventions that are proven effective in reducing pregnancy in adolescence, and that incorporate multiple levels of the Social Ecological Model.

Additional weaknesses noted were the lack of a theoretical framework for the interventions, and the sampling techniques used, which oftentimes consisted of convenience samples of adolescents. In addition, there was a lack of community capacity building vis-à-vis training of peer leaders as intervention facilitators as well as a lack of community collaboration and/or partnership in the design or implementation of any of the interventions. Finally, there was a general lack of culturally tailored programs that addressed Latino-specific cultural values and that facilitated learning among this group (e.g., culturally relevant topics of discussion, linguistically appropriate education materials, youth-friendly intervention facilitators).

A recurring limitation of the interventions was the lack of a clear definition of sexual activity when it was used as an outcome measure. For example, it would have been helpful to know if anal, oral, and vaginal sexual behavior were included in the definition of sexual activity. Another limitation was that most were conducted in school settings, which did not include adolescents who skipped class that particular day or those who were not enrolled in school. Given that Latinos have the highest dropout rates in comparison to non-Hispanic Whites and African Americans (21.4%, 5.3% and 5.4%, respectively), the lack of interventions outside of school settings poses serious limitations for intervening with this population.52 Another limitation was the lack of culturally sensitive components used during intervention implementation (e.g., employing Latino intervention facilitators, addressing cultural gender roles). Finally, no interventions targeted behavior change at the community or societal levels that would produce community-wide or social changes that would impact the policies needed to address Latino adolescent risky sexual behaviors.

Future research should examine the feasibility of replicating previously successful and valid studies that have been conducted with Latino adolescents. Specifically, these studies should be conducted in areas of newest Latino migration, where Latinos are most vulnerable because they face more isolation in terms of fewer available resources (e.g., access to culturally sensitive health services and providers).53 Both theory- and practice-based interventions are needed that address the sexual health problems of these adolescents. When conducting new interventions, researchers must recruit samples of adolescents that are more representative of the overall U.S. Latino community. Studies are needed that target specific Latino subgroups, based on socio-demographic characteristics to generate group-specific findings. More attention must be placed on targeting high-risk Latino adolescent populations. That is, those adolescents with friends and relatives who were adolescent-age parents; students with low academic achievement; adolescents who are not enrolled in schools; adolescents with delinquent behavior; undocumented immigrants; and homosexual adolescents. Future literature reviews on Latino adolescent sexual health interventions should include other types of searches (e.g., using additional databases that may include the gray literature such as the work of research organizations and government agency documents not published in journals). Additional search terms in addition to the ones listed in this article should be included that pertain to adolescent sexual health (e.g., contraception, pregnancy prevention, STD testing, high-risk adolescent).

Limitations of the Literature Review

The literature review proposed here is not without limitations. We searched and used five databases that were accessible through the University of Pittsburgh’s Health Science Library System. Only English-language articles were searched. Certain key words may have been missed in the search; however, the search term list was as comprehensive as possible in order to minimize this limitation. Additionally, published articles did not always report critical information necessary for the analytical component of this literature review; therefore, this information could not be assessed or reported. No searches were conducted to identify the gray literature (i.e., written materials that are not generally published) on Latino adolescent sexual health interventions. However, documents assessing the sexual health interventions targeting Latinos have been published by prominent organizations. One example is the brief published by The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, which describes six programs that have demonstrated delay of sexual activity, improved contraceptive use, and/or a reduction in adolescent pregnancy. 54 Another example is the document published by Advocates for Youth, which highlights programs that are effective at delaying sexual initiation or reducing sexual risk taking among Latino adolescents in the U.S.55

Conclusions

In this literature review, which spanned 18 years, regarding the sexual health behavioral interventions for U.S. Latino adolescents, the findings suggest that not many interventions have addressed their sexual health needs. Using the Social Ecological Model as a framework for mapping Latino adolescent sexual health interventions, gaps in the literature and our understanding suggest the need for incorporating multiple social ecological levels when developing and implementing interventions. Researchers have, for the most part, focused on changing behaviors at the individual and the interpersonal levels. However, the Latino community comprises complex social and cultural factors at the community and societal levels that are critical when addressing adolescent sexual health needs.

Latino adolescent sexual health is a fairly new field of research with multiple problems that need to be addressed. Understanding the multiple and complex issues within the U.S. Latino community is needed to effectively promote change. This literature review points out the multiple challenges researchers and public health practitioners may face when developing and implementing behavioral interventions for Latino adolescents. As the largest ethnic minority group in the U.S., the Latino population’s health needs must be further addressed through effective, culturally relevant interventions that not only describe health status, but also present potential solutions to eliminating the social inequalities in the outcomes of their sexual health.

In the interest of eliminating health disparities, the research agenda in this field can be viewed as a three-phase framework, which is constituted by (1) the detection of health disparities and vulnerable populations, (2) the understanding of the causes of given health disparities, and (3) the reduction of health disparities.56 Currently, national data demonstrate the measures by which Latino adolescent sexual health varies in comparison to non-Hispanic adolescents. Research has focused on identifying risk and protective factors that impact the sexual health of Latino adolescents, but more effort is needed to reduce the disparity in sexual health outcomes of Latino adolescents. This literature review of Latino adolescent sexual health indicates that more research is needed to produce novel, age-specific and culturally tailored sexual health interventions in order to reduce health disparities among Latino adolescents in the U.S.

Acknowledgments

This literature review was built upon the first author's master's thesis at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health. The second author was supported in part, through her Mentored Career Development Award (K07CA134635; PI: Patricia I. Documét). The third author was supported in part, through his Mentored Research Scientist Development Award to Promote Diversity (K01CA148789; PI: Craig S. Fryer). The fifth author was supported in part, through his Mentored Career Development Award to Promote Diversity (K01CA134939; PI: James Butler III).

Footnotes

The authors indicate no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 2007. [Accessed October 24, 2011];2009 Jan; Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/STDTrendsFactSheet.pdf.

- 2.Darroch JE, Singh S, Frost JJ. Differences in teenage pregnancy rates among five developed countries: the roles of sexual activity and contraceptive use. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33:244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:6. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGough LJ, Handsfield HH. History of behavioral interventions in STD Control. In: Aral SO, Douglas JM, editors. Behavioral Interventions for Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York: Springer; 2007. p. 3e22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santelli J, Ott MA, Lyon M, et al. Abstinence and abstinence-only education: a review of U.S. policies and programs. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:72. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenthal SL, Cohen SS, Biro FM. Stanberry LR, Bernstein DI. Sexually transmitted diseases: vaccines, prevention and control. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. Behavioral and psychological factors associated with STD risk; p. 125e138. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tilton-Weaver LC, Kakihara F United States of America. International Encyclopedia of Adolescence. Vol. 2. New York: Taylor & Frances Group; 2007. pp. 1061–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pew Hispanic Center: Census. 50 Million Latinos—Hispanics account for more than half of nation’s growth in past decade. [Accessed March 30, 2011];2010 March 24, 2011. Available: http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/140.pdf.

- 9.Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Sullivan S, et al. Ecodevelopmental HIV prevention programs for Hispanic adolescents. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74:545. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deardorff J, Tschann M, Flores E, et al. Sexual values and risky sexual behaviors among Latino youths. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;42:23. doi: 10.1363/4202310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenton KA. Strategies for improving sexual health in ethnic minorities. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2001;14:63. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200102000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jimenez J, Potts MK, Jimenez DR. Reproductive attitudes and behavior among Latino adolescents. J Ethn Cult Divers Soc Work. 2002;11(3):221. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong B, Cohall AT, Vaughan RD, et al. Involving men in reproductive health: the Young Men’s Clinic. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:902. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.6.902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathews MS, Sutton PD, Hamilton BE, et al. NCHS Data Brief: State disparities in teenage birth rates in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics. 2010;46:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for HIV, STD and TB Prevention, Division of STD/HIV Prevention: Sexually Transmitted Disease. [Accessed October 24, 2011];Morbidity Data Archives 1996 to 2008. Available: http://wonder.cdc.gov/stdmArchives.html.

- 16.Driscoll AK, Biggs MA, Brindis CD, et al. Adolescent Latino reproductive health: a review of the literature. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2001;23:255. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afable-Munsuz A, Brindis CD. Acculturation and the sexual and reproductive health of Latino youth in the United States: a literature review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:208. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.208.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazargan M, West K. Correlates of the intention to remain sexually inactive among underserved Hispanic and African American high school students. J Sch Health. 2006;76:25. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards LM, Fehring RJ, Jarrett KM, et al. The influence of religiosity, gender, and language preference acculturation on sexual activity among Latino/a adolescents. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2008;30:447. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livaudais JC, Napoles-Springer A, Stewart S, et al. Understanding Latino adolescent risk behaviors: parental and peer influences. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villarruel AM, Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, et al. Recruitment and retention of Latino adolescents to a research study: lessons learned from a randomized clinical trial. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2006;11:244. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2006.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flores G, Zambrana RE. The early years: the health of children and youth. In: Aguirre-Molina M, Molina CW, Zambrana RE, editors. Health Issues in the Latino Community. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001. p. 77e106. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grzywacz JG, Fuqua J. The social ecology of health: leverage points and linkages. Behav Med. 2000;26:101. doi: 10.1080/08964280009595758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:351. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sallis JF, Owens N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Cancer Institute. Theory at a Glance: a guide for health promotion practice. [Accessed February 20, 2009];Spring. 2005 Available: http://www.cancer.gov/PDF/481f5d53-63df-41bc-bfaf-5aa48ee1da4d/TAAG3.pdf.

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Community Guide: Glossary: intervention. [Accessed June 6, 2009]; Available at http://www.thecommunityguide.org/about/glossary.html.

- 28.Academy for Educational Development, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DEBI: Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions. [Accessed February 19, 2009]; Available: http://www.effectiveinterventions.org.

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed April 22, 2011];Trends in the prevalence of sexual behaviors, National YRBS: 1991–2009. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/us_sexual_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- 30.American Academy of Pediatrics. Children’s health topics: developmental stages. [Accessed March 20, 2009]; Available: http://www.aap.org/healthtopics/stages.cfm#adol.

- 31.Office of Management and Budget. Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. [Accessed May 28, 2009];2003 Jan; Available: http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/race/Ombdir15.html.

- 32.Shanklin S, Brener ND, Kann L, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Youth risk behavior surveillance—selected Steps communities, United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiCenso A, Guyatt G, Willan A, et al. Interventions to reduce unintended pregnancies among adolescents: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2002;324:1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oakley A, Fullerton D, Holland J, et al. Sexual health education interventions for young people: a methodological review. BMJ. 1995;310:158. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robin L, Dittus P, Whitaker D, et al. Behavioral interventions to reduce incidence of HIV, STD, and pregnancy among adolescents: a decade in review. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:3. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirby D. Emerging Answers 2007: research findings on programs to reduce teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. [Accessed January 20, 2010];National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy November 2007. 2007 Nov; Available http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/EA2007/EA2007_full.pdf.

- 37.Sellers DE, McGraw SA, McKinlay JB. Does the promotion and distribution of condoms increase teen sexual activity? Evidence from an HIV prevention program for Latino youth. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1952. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hovell M, Blumberg E, Sipan C, et al. Skills training for pregnancy and AIDS prevention in Anglo and Latino youth. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23:139. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lazebnik R, Grey SF, Ferguson C. Integrating substance abuse content into an HIV risk-reduction intervention: a pilot study with middle school-aged Hispanic students. Subst Abuse. 2001;22:105. doi: 10.1080/08897070109511450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Anda D. The GIG: an innovative intervention to prevent adolescent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection in a Latino community. J Ethn Cult Divers Soc Work. 2002;11:251. [Google Scholar]

- 41.East P, Kiernan E, Chávez G. An evaluation of California’s Adolescent Sibling Pregnancy Prevention Program. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35:62. doi: 10.1363/3506203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koniak-Griffin D, Lesser J, Nyamathi A, et al. Project CHARM: an HIV prevention program for adolescent mothers. Fam Community Health. 2003;26:94. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Anda D. Baby Think It Over: evaluation of an infant simulation intervention for adolescent pregnancy prevention. Health Soc Work. 2006;31:26. doi: 10.1093/hsw/31.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villarruel AM, Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS. A randomized controlled trial testing an HIV prevention intervention for Latino youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:772. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:914. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tortolero SR, Markham CM, Addy RC, et al. Safer choices 2: rationale, design issues, and baseline results in evaluating school-based health promotion for alternative school students. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:70. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koniak-Griffin D, Lesser J, Henneman T, et al. HIV prevention for Latino adolescent mothers and their partners. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30:724. doi: 10.1177/0193945907310490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boutin-Foster C, McLaughlin N, Gray A, et al. Reducing HIV and AIDS through Prevention (RHAP): a theoretically based approach for teaching HIV prevention to adolescents through an exploration of popular music. J Urban Health. 2010;87:440. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9435-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tello J, Cervantes RC, Cordova D, et al. Joven noble: evaluation of a culturally focused youth development program. J Community Psychol. 2010;28:799. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Jaccard J, et al. A parent-based intervention to reduce sexual risk behavior in early adolescence: building alliances between physicians, social workers, and parents. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:159. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harper GW, Bangi AK, Sanchez B, et al. A quasi-experimental evaluation of a community-based HIV prevention intervention for Mexican American female adolescents: the SHERO’s program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(5 Suppl):109. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. The condition of education. [Accessed October 24, 2011];2009 Available: http://nces.ed.gov/FastFacts/display.asp?id516.

- 53.Cunningham P, Banker M, Artiga S, et al. Health Coverage and Access to Care for Hispanics in "New Growth Communities" and "Major Hispanic Centers". [Accessed June 6, 2009]; Available: http://www.kff.org/uninsured/upload/7551.pdf.

- 54.The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy: Science says #43: effective and promising teen pregnancy prevention programs for Latino youth. [Accessed March 29, 2011];2010 Available: http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/pdf/SS/SS43_TPPProgramsLatinos.pdf.

- 55.Advocates for Youth: Science and success: science based programs that work to prevent teen pregnancy, HIV & sexually transmitted infections among Hispanics/Latinos. [Accessed March 29, 2011];2009 Available at: http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/storage/advfy/documents/sslatino.pdf.

- 56.Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, et al. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2113. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]