Summary statement

In this issue of Cell Stem Cell, Kokovay et al., uncover that VCAM1 expression in neural stem cells regulates adult neurogenesis. Cerebrospinal fluid-borne IL-1β upregulates VCAM1 expression, which in turn regulates the architecture of the stem cell niche, redox homeostasis, and neurogenesis.

Recent advances in the field of adult neurogenesis center on elucidating how systemic signals integrate with cell intrinsic cues to influence the division of neural stem cells. A poignant example comes from the work of Villeda and colleagues last year, where by using a heterochronic parabiotic approach, they found that blood-borne chemokines influence neurogenesis in an age-dependent manner (Villeda et al., 2011). Bringing us one step closer to understanding how adult neurogenesis is regulated, Kokovay et al. (2012) now provide molecular insight into how vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM1), a cell surface sialoglycoprotein and a member of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily, regulates niche architecture, and as a result, neural stem cell function.

The adult mammalian brain contains two neurogenic regions, the recently renamed ventricular-subventricular zone (V-SVZ) located adjacent to the lateral ventricles, and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampus. Kokovay and colleagues focus on the V-SVZ, where astrocytes (Type B cells, the neural stem cells) give rise to immature precursors (Type C cells, transit amplifying cells), which then generate neuroblasts (Type A cells) that migrate in chains to the olfactory bulb. The B cells, which span the full extent of the germinal epithelium, have an apical domain containing a primary cilium that navigates the ependymal cell layer (E cells), to achieve contact with the lateral ventricle cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and a basal domain extending to the vascular plexus, where B cells contact endothelial cells (reviewed in Fuentealba et al., 2012). En face, the ventricular surface offers a stunning view of the V-SVZ organized into pinwheels, with the B cells’ primary cilia extending into the CSF, surrounded by rosettes of multi-ciliated ependymal cells (See Figure 3 in Mirzadeh et al., 2008). The unique architecture of this germinal niche, and the striking polarity of the B cells, are believed to function as key determinants of adult neurogenesis.

Kokovay and colleagues reveal that enriched VCAM1 expression on the apical endfeet of B cells plays a crucial role in maintaining pinwheel architecture, β-catenin expression, and adult neurogenesis (Kokovay, 2012). While loss of polarity in the developing brain is frequently associated with premature withdrawal from the cell cycle (Lehtinen and Walsh, 2011), Kokovay and colleagues show that blocking VCAM1 function and the resulting disruption of V-SVZ pinwheels actually stimulates quiescent adult B cell proliferation. The progeny of these B cells then advance through the cell lineage, first to C cells, and then to A cells. Their swift progression ultimately results in a neural stem cell niche that is prematurely devoid of its fundamental players: the neural stem cells themselves. As a first step towards unraveling the molecular mechanisms by which VCAM1 maintains the adult neural stem cell niche, the authors find that VCAM1 expression co-localizes with NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) in the apical processes of B cells and that VCAM1 knockdown leads to decreased NOX2 expression in neurospheres, an in vitro model of neural stem cells. In a bedazzling approach, Kokovay et al. demonstrate that the artificial activation of VCAM1 with antibody-activating beads in adherent adult SVZ cultures stimulates ROS accumulation in neural stem cells, as visualized by the ROS sensor dihydroethidine. When oxidized in the presence of superoxide anion in cells, dihydroethidine forms a fluorescent signal that intercalates into DNA for straightforward quantification. Taken together, these findings support the conclusion that VCAM1 signaling helps maintain redox homeostasis in neural stem cells.

ROS in the central nervous system are notoriously associated with injury or the acceleration of age-associated neurologic disease. However, ROS can be less threatening. There is a less appreciated role for ROS involving the benefits of redox-mediated signaling, governed largely by cell type, differentiation state, and environmental signals (Droge, 2002). Although the exact mechanisms by which ROS regulate neurogenesis are not fully understood, fluctuating ROS levels have been shown to fine tune quiescent vs. proliferative stem cell states. For example, the depletion of neural stem cells upon VCAM1 inhibition is reminiscent of the phenotype observed upon deletion of Forkhead (FoxO) transcription factors. FoxO3-deficiency in neural stem cells leads to increased ROS production, which triggers an initial hyperproliferation of neural stem cells, followed by their subsequent senescence (Renault et al., 2009). Self-renewing neural stem cells have been shown to maintain high NOX-stimulated production of ROS, and this favorable effect of ROS depends upon PI3K/Akt signaling (Le Belle et al., 2011).

What regulates VCAM1 activity in vivo? Drawing parallels between hematopoietic stem cells and the adult neural stem cells niche, Kokovay and colleagues previously demonstrated that stromal differentiation factor-1 (SDF1) present in a gradient between the vasculature and ependymal cells promotes either motility or quiescence of neural stem cells (Kokovay et al., 2010). However, the apical localization of B cells along the lateral ventricle suggests that B cells may be perfectly poised to receive signals from the CSF as well, as has been demonstrated for neural progenitor cells in the developing embryonic brain (Lehtinen et al., 2011). Indeed, interleukin 1β (IL-1β) has previously been found to be expressed by the choroid plexus and distributed in the CSF, and the IL1 receptor is also present on B cells, suggesting that neural stem cells are equipped to respond to this signal. Kokovay et al. here demonstrate that SDF1 and IL-1β regulate VCAM1 expression, with IL-1β having a particularly robust effect. Kokovay et al. complete their story with a functional experiment demonstrating that lateral ventricle infusion of IL-1β leads to decreased proliferation of B cells, consistent with the model that CSF-borne IL-1β-mediated VCAM1 expression maintains the neural stem cell state and prevents lineage progression (Figure 1).

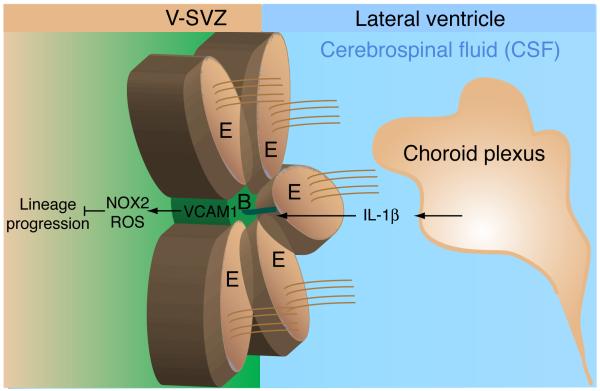

Figure 1. Schematic depicting VCAM1 mediated maintenance of the adult neural stem cell niche.

Choroid plexus-secreted IL-1β binds to IL1 receptors on the surface of Type B neural stem cells and upregulates VCAM1 expression. In turn, VCAM1 promotes adhesion to the neural stem cell niche and the pinwheel architecture of ependymal cell rosettes (brown cells) surrounding B cells (green cell) via maintenance of redox homeostasis by NOX2 activation. Inhibition of VCAM1 stimulates quiescent Type B cells to proliferate and advance through the cell lineage to Type A neuroblasts that migrate to the olfactory bulb. Abbreviations: B: Type B neural stem cell; E: Ependymal cell; IL-1β: interleukin 1β; NOX2: NADPH oxidase; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; VCAM1: vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; V-SVZ: Ventricular-subventricular zone.

Collectively, the work of Kokovay and colleagues illuminates how crucial the maintenance of niche architecture is for B cells, allowing them to sample cytokines originating from two distinct humoral sources, the CSF and blood, to integrate instructive cues for neurogenesis. Both IL-1β and SDF1 have been reported to be upregulated in the CSF upon injury or disease. These observations suggest the possibility that the vasculature and CSF actively maintain homeostatic control over damage-induced neurogenesis, so as not to prematurely deplete the brain of neural stem cells. Unraveling the full suite of cell extrinsic factors that pair with cell intrinsic mechanisms regulating polarity and cell division should spur new therapeutic advances in service of nervous system repair.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba LC, Obernier K, Alvarez-Buylla A. Adult neural stem cells bridge their niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:698–708. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokovay E, Goderie S, Wang Y, Lotz S, Lin G, Sun Y, Roysam B, Shen Q, Temple S. Adult SVZ lineage cells home to and leave the vascular niche via differential responses to SDF1/CXCR4 signaling. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokovay E, Wang Y, Kusek G, Wurster R, Lederman P, Lowry N, Shen Q, Temple S. VCAM1 is essential to maintain the structure of the SVZ niche and acts as an environmental sensor to regulate SVZ lineage progression. Cell Stem Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.06.016. In this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Belle JE, Orozco NM, Paucar AA, Saxe JP, Mottahedeh J, Pyle AD, Wu H, Kornblum HI. Proliferative neural stem cells have high endogenous ROS levels that regulate self-renewal and neurogenesis in a PI3K/Akt-dependant manner. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen MK, Walsh CA. Neurogenesis at the brain-cerebrospinal fluid interface. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:653–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen MK, Zappaterra MW, Chen X, Yang YJ, Hill AD, Lun M, Maynard T, Gonzalez D, Kim S, Ye P, et al. The cerebrospinal fluid provides a proliferative niche for neural progenitor cells. Neuron. 2011;69:893–905. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzadeh Z, Merkle FT, Soriano-Navarro M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Neural stem cells confer unique pinwheel architecture to the ventricular surface in neurogenic regions of the adult brain. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renault VM, Rafalski VA, Morgan AA, Salih DA, Brett JO, Webb AE, Villeda SA, Thekkat PU, Guillerey C, Denko NC, et al. FoxO3 regulates neural stem cell homeostasis. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeda SA, Luo J, Mosher KI, Zou B, Britschgi M, Bieri G, Stan TM, Fainberg N, Ding Z, Eggel A, Lucin KM, Czirr E, Park JS, Couillard-Després S, Aigner L, Li G, Peskind ER, Kaye JA, Quinn JF, Galasko DR, Xie XS, Rando TA, Wyss-Coray T. The ageing systemic milieu negatively regulates neurogenesis and cognitive function. Nature. 2011;477:90–4. doi: 10.1038/nature10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]