Abstract

Background

Though child sexual abuse is a universal phenomenon, only reported cases of the incidence are common source of information to get insight on how to understand the problem. Besides, investigating complaints presented by victims themselves would be a stepping stone for designing prevention and rehabilitation programs. The objective of this study was to identify the nature of sexual incidence and experience victims face.

Methods

The research was conducted by collecting reported child sexual abuse cases from Child Protection Units of Addis Ababa Police Commission and three selected non-governmental organizations working for the welfare of sexually abused children in Addis Ababa. 64 selected samples of victim children were included from the three organizations. They completed a semi-structured questionnaire and data were analyzed.

Results

Of the total reported crime cases committed against children (between July 2005 and December 2006), 23% of them were child sexual victimization. On average, 21 children were reported to be sexually abused each month where majority of the sexual abuse incidence were committed against female children in their own home by someone they closely know. The psychological trauma and physical complaints presented by victims include symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Conclusion

It was found out that child sexual abuse cases presented to the legal office was not properly managed. Female children appear to be more prone to sexual abuse than their male counterparts. By virtue of their nature, many children are at risk of sexual victimization by people they truest. Based on the findings, several implications are made, which includes the importance of nation-wide study to formulate a comprehensive policy guideline for protection and criminalization of child sexual abuse in Ethiopia.

Keywords: Children, sexual abuse, psychosocial consequences, crime, Addis Ababa, child protection

Introduction

Child sexual abuse, using children for sexual gratification of adult, is a criminal act committed against children which probably is one of the least acknowledged and least explored forms of child abuse in Ethiopia. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) explicitly states that sexual acts are assumed to be crime and punishable by the law. It asserts the child's right to be protected against all forms of sexual abuse and exploitation including being forced to engage in unlawful sexual activities, prostitution and pornography (1). Although almost three decades have passed since its recognition, researchers have not yet reached at a universal consensus on which acts to count as child sexual abuse and which are not. Scholars in this area generalize that it is a very difficult task to estimate any form of deviance in the general population particularly sexual offending targeted against children (2). In particular, finding exact number of child sexual abuse cases actually occurring is almost impossible (3). The problem of obtaining accurate statistics on the prevalence of child and adolescence sexual abuse can be attributed to several factors. For example, inconsistencies in the definitions given to what constitute child sexual abuse (4); it is committed in “complete secrecy” and most victim children do not report as they are “too ashamed to talk about it.” (5)

Though growing body of researchers believe that child sexual abuse is dangerously growing worldwide, prevalence rate of cases vary depending on studies done in different places and time. A survey conducted on adults asking if they were sexually abused as children identified that approximately 20% of adult women and 5% to 10% of adult men in the United States experienced sexual abuse at some time in their childhood(3). Most survey findings seem consistent with the general trends that female children, compared with their male counterparts, are more likely to have suffered sexual abuse. In United States, the risk of sexual abuse towards girls is two times greater than boys (6). For instance a study conducted on796 college students indicated that 19% of women and 9% of men had experienced some form of sexual abuse as children (7). Similarly, a national survey conducted in England, concluded that 3.2% of girls and 0.6% of boys have reported that they were victims of sexual assault involving physical contacts (8).

Research evidence on child sexual abuse incidence in Ethiopian is scarce. Despite this, the rate of reports accentuates serious concern. A cross-sectional study conducted in Addis Ababa identified child sexual abuse prevalence rate of 38.5 % among the general public, out of which 29% were committed by victims' family members and 68% of them were victimized by adults the children knew (9). A similar study done in South west Ethiopia also revealed that 68.7% of High School girls have reported that they were sexually abused including verbal or physical contacts (10). In a similar study, samples of hospital reports show that 61.7% of alleged sexual abuse cases were targeted against children (11). Nevertheless, the fact that few researches being conducted; negative societal attitude of reporting the incidence and limited access to health facilitates created difficulty in presenting accurate estimation of child sexual abuse in developing countries including sub-Saharan Africa (12).

In relation to victim's relationship to abusers, some estimates reveal that out of the total reported child sexual abuse cases, 50% of them were abused by someone the children know, close and trust while about 30–40% were committed by family members (incest) (12). And the remaining 10–20% of the children were abused by strangers. Here, it has to be noted that the results of such study provide estimates of the prevalence of sexual abuse in the population from which the group is selected. Prevalence rates are predicted based on the small percentages of reported sexual abuse crimes (7, 9). Nevertheless, such statistical figures indicate only the tip of the iceberg. It is predicted that if all sexual abuse cases were identified and recorded, the data would be very shocking.

Generally, it has been shown that experiencing trauma, including sexual victimization can have an effect on the child's ability to function normally. Children experience various short-term and/or long-term effects as a result of sexual victimization. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is the most common psychological impact of child sexual abuse while many victims frequently suffer from depression, anxiety, promiscuity, general behavior problems, poor self-esteem and disruptive behavior disorders (12); and clinically significant disorders, such as dissociative disorders, substance-related disorders as well as eating disorders (13). A case-control comparative analysis further identified that, children who were victims of sexual abuse in Ethiopia suffered from delicate psycho-social assistance, strong feeling of guilt and perceived the environment as full of threat (14).

Furthermore, as children mature to adulthood, they can experience impairments in social and occupational functioning. This includes isolation/withdrawal, phobias, aggression, poor work performance and disturbed interpersonal relationships (13). The effect of child sexual abuse is not only limited to host of psychological and psychiatric problems but also to physical manifestations, which include difficulty in walking or sitting, bruises, bleeding or itching in genital area or the mouth, pregnancy or sexually transmitted disease, especially among preteens and repeated urinary infections (15). In addition, engaging in unsafe sex, having many sexual partners, earlier sexual initiation, unplanned pregnancy and higher risk of infection with STDs including HIV/AIDS are also common consequence of child sexual abuse (16).

In summary, though child sexual abuse is a universal phenomenon, sources of understanding the magnitude, factors and consequences of the incidences in developing countries like Ethiopia is scanty because of socio-cultural reasons. Thus, cases presented to hospitals and the police would be the major source of such studies and these data are important though they may leave many questions unanswered. In general, the objectives of the study was to review child sexual abuse cases presented to Child Protection Units of Addis Ababa Police and to identify circumstances that surrounds the sexual victimization incidences.

Methods and Materials

The study was done in Addis Ababa City from January 15 to June 20, 2006. Data was collected from Child Protection Units of Addis Ababa Police Commission as well as three local non-governmental organizations providing psychosocial support to child victims of sexual abuse. The data collection task was accomplished in the following two steps.

Data regarding the overall reported crime cases against children, including child sexual abuse, was collected from the Addis Ababa Police Commission. The commission has a special unit organized to exclusively deal with crime cases committed by or against children in 13 sub-cities of the capital. Mainly, it assists victims of child sexual abuse with legal aids and refers victims to institutions providing psycho-social and rehabilitation supports.

For the purpose of identifying the demographic variables of victim children, the situation of the sexual abuse as well as consequences, it was necessary to collect data from selected samples of victim children. And this was done in three NGOs namely Integrated Family Service Organization (IFSO), Forum on Street Children Ethiopia (FSCE) and Organization for Protection and Rehabilitation of Female Street Children (OPRFS) which were working on psycho-social interventions including medical, psychological, educational and financial supports.

During the time of data collection in the three organizations, a total population of 203 sexually abused children (197 girls and 6 boys) were getting counseling and rehabilitation services. Out of the 203 sexually abused children, 167 (6 boys and 161 girls) were getting the service from IFSO, 30 (all girls) from FSCE and the remaining 6 (all girls) from OPRIFS. Even though the age of beneficiary children ranged from preschoolers to 18 years old, children between the ages of 11 - 18 years and those who took the service for one year and more were selected for the study. The rationale behind selecting this group of samples was that they are believed to give adequate information than children of early and middle childhood period. Thus, total samples of 64 respondents were taken from the three organizations.

Ethical clearance was obtained from department of psychology, Addis Ababa University. Accordingly, an official letter was written to Addis Ababa Police Commission and the three selected organizations. On behalf of the children, the project coordinators of each organization gave consent. After permission was secured, discussion was held with counselors and social workers in the respective organizations regarding the ethical issues and data collection procedures.

In fact, so as to safeguard the identity of victim children, external research assistants were not involved. Instead, the data were collected only by the staff members from the respective organizations, under the supervision of the principal investigator. In addition, strict confidentiality was assured through anonymous recording, and computer based coding of questionnaires, data analysis and kept in safe place.

Before respondents start completing the semi-structured questionnaires, counselors and social workers gave brief orientation on the purpose and method of completion. The study variables, which included the demographic variables, the relationship between victim and perpetrator, time and place of the initial sexual abuse incidence and perceived psychological and physical repercussions following the victimization were assessed.

Results

Overall, the Addis Ababa Child Protection Units database illustrates that between July 2005 and December 2006, about 1666 different forms of crime cases were committed against children. Out of these, 383 (23%) cases of child sexual abuse were reported during the stated period. This is an average of 21.3 children who reported that they were sexually abused each month from July 2005 to December 2006 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of Alleged Sexual Abuse Cases across Age and Sex, Addis Ababa, 2006.

| Age Range | Sex | Total | ||||

| Male | Female | |||||

| Freq. | Percent | Freq. | Percent | Freq. | Percent | |

| 1–9 | 12 | 3.13 | 95 | 24.81 | 107 | 27.94 |

| 9–15 | 28 | 7.31 | 225 | 58.75 | 253 | 66.06 |

| 16–18 | 2 | 0.52 | 21 | 5.48 | 23 | 6.0 |

| Total | 42 | 10.96 | 341 | 89.04 | 383 | 100 |

Source: Child Protection Units-Addis Ababa Police Commission, June 2006

Data from selected samples of victim children was examined to see the demographic variables of victim children, their relationship with perpetrators and the psycho-social experiences respondents were undergoing. Hence, data collected from victims in the three NGOs (IFSO, FSCE and OPRIFS) were examined.

The data presented in table 2 reveals that all participants (64 client children) are female children. The subjects' age ranged from 11 to 18 years. Those who are between 11 and 14 constitute 28.1% of the total samples and the remaining 71.9% of them are between 15 and 18 years of age. With respect to educational profile of respondents, 70.3% of them are in elementary and junior secondary school levels while the remaining 25% are high school and preparatory class students.

Table 2.

Socio — Demographic Information of Respondents, Addis Ababa, 2006.

| Variable | Frequency | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 0 | 0 |

| Female | 64 | 100 |

| Age | ||

| 11–14 | 18 | 28.1 |

| 15–18 | 46 | 71.9 |

| Total | 64 | 100 |

|

Age at the time of sexual abuse |

||

| 5–8 | 11 | 17.2 |

| 9–12 | 19 | 45.3 |

| 13–16 | 24 | 31.5 |

| Grade Level | ||

| 2–4 | 13 | 20.3 |

| 5–8 | 32 | 50 |

| 9–12 | 16 | 25 |

Table 3 reflects two important familial variables of respondents. Children who indicated that they live with both parents and those who live with their relatives are proportionally equal in number (26.6%) each followed by “others” (23.5%). The rest 18.8% live only with their mothers; whereas 1% of the total respondents live with father.

Table 3.

Living Condition of Respondents, Addis Ababa, 2006.

| Living Condition | Frequency | Percentage |

| Live with both parents | 17 | 26.6 |

| Live with relatives | 17 | 26.6 |

| with mother only | 12 | 18.8 |

| With father only | 1 | 1.6 |

| Unknown* | 15 | 23.5 |

| Total | 64 | 100 |

respondents live with their employers, on the street or unwilling to mention

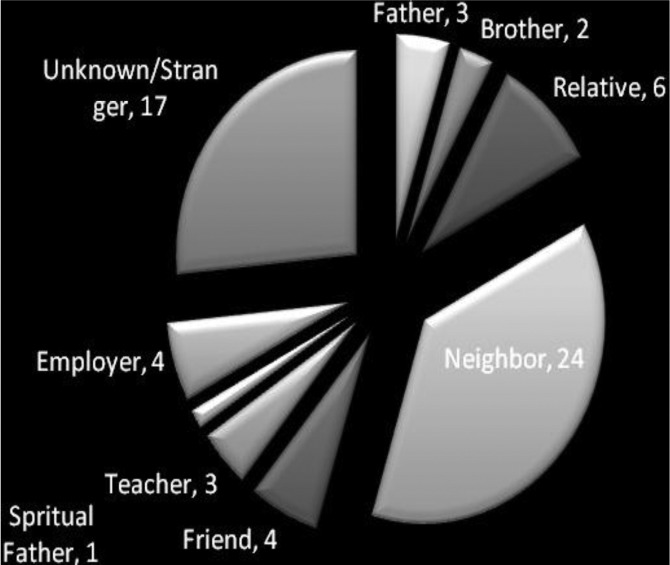

The perpetrator's relationship to the victims is depicted in a pie-chart, classified in to nine major categories. The data shows that a greater number of respondent children were victimized by someone they closely know. Accordingly, family members, relatives, neighbors, friends, teachers, employers and a priest in general constitute 73.4% of all abusers. But the remaining 26.6% of perpetrators were reported to be strangers the children never met (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Descriptions of Victims Relationship to Perpetrators, Addis Ababa, 2006.

In order to observe the situational analysis of the sexual abuse incidences, respondents were asked to indicate the time, place and the approach the perpetrator used for the sexual victimization. Accordingly, the majority of respondents mentioned that they were abused in their own home, after the sunset (6:00 pm) being tricked by the perpetrator in different ways.

All concerns identified by respondents are found to be related to common reactions of child sexual victimization as mentioned by other researchers. Theoretical explanations and research findings has also substantiated that different victim children experience the consequence of their abuse differently. Accordingly, younger children experience more severe physical complications than those in post-puberty age group.

Discussion

Most estimates of the distribution of sexual offenders as well as victims in the general population are derived from the forensic data, that is, samples of those whose victimization have been directly reported to the concerned legal institutions/police and hospitals. For this particular study, the 18 months (between July 2005 and December 2006) reported data was obtained from Addis Ababa Police Commission to examine the prevalence rate. This is because, there was no reliable data recorded before July 2005 regarding crimes committed against children including child sexual abuse. Even the existing data does not reveal the nature and magnitude of reported cases of child sexual abuse due to lack of comprehensive data management system.

The data clearly shows that only small proportion of child sexual abuse is reported out of the total incidences actually occurring in the metropolitan. Still, such cross-sectional row official data may not resolve the controversy whether there is increment in the actual incidence or more cases are brought to the law enforcement authorities. Yet, it can be used as a base to produce some implications for the scientific community as well as for those concerned bodies.

According to the figures obtained from the police department, about 21 children on average were sexually abused each month during the reported period and the majority of victims were young female children. During the eighteen months stated, about 89% of victims were found to be female children and the remaining 11% were males. Similarly, the data obtained from the three organizations reveals that more female victims are receiving support for sexual abuse in Addis Ababa which indicates their vulnerability for the problem.

The demographic variables of respondents indicated that three fourth of the victims came from single-parent families and other care takers, suggesting greater chance of being left alone and vulnerability for potential perpetrators. Surprisingly enough, similar proportions of respondents were sexually abused by someone victims knew and trust. This implies that greater number of incidences remain unreported as victims may feel shameful, fear of being punished, labeling, court process, mistrusted and blamed, especially if the victim child is reliant on the perpetrator(5). In other instances, children can also be sexually abused by the legal personnel, whom they greatly depend on for their security. The police may threaten to arrest innocent street children to force them involve in sexual activities and victimization could continue in the correction centers as well (17).

Child sexual abuse can vary along a number of dimensions including frequency, duration, age at onset, and relationship of victim to perpetrator. The main groups of perpetrators in this study were neighbors followed by strangers. This finding coincides with previous study done in Ethiopia (10) suggesting that children victims of sexual abuse were not properly monitored by their parents and care givers or they are not in a situation to understand the act itself as sexual abuse. Nevertheless, it appears contradictory but important to recognize that children living with their biological parents, as long as they are not offenders, have a greater advantage of being protected as compared to those who live with relatives, legal guardians and those living on the street.

Despite the general truth that child sexual abuse can happen anywhere and anytime, children who reported that they were victimized in their home took the greater proportion. This is because home may increase accessibility for sexual predators to catch their pray and hiding the incidence from potential witnesses. Generally, the fact that there is no clearly designated riskier or safer place for sexual victimization targeted against children, it would be relevant to consider the psychological make-up of perpetrators. In this regard, it is identified that the motivation of the perpetrator; the resolution of internal barriers; dealing with the resistance of the potential victim as well as controlling external barriers are preconditions to be met for perpetrators commit a wide variety of sexual crime (18).

In conclusion, limited and inadequately documented official records of child sexual abuse cases may not provide a comprehensive picture of the problem in a particular community. However, the researcher acknowledges that the existing documents, which are relevant in some aspects, contribute to implications for prevention, treatment, follow-up as well as design for new procedures in better controlling such crimes in Addis Ababa. For instance, increase in the number of child sexual abuse reports over a period of years, provided that it is proved, may lead to considerations of some changes in the approaches of dealing with cases. Despite the popular belief that most children are sexually victimized by strangers in unknown places, the findings of the study further implicate that sexual abuse could happen to any child irrespective of the degree of attachment between perpetrators and victims.

This study is a cross sectional study where the data were collected from the respondents only once. Thus, the development and transformation in terms of the psychosocial challenges and level of adjustment is unable to be evaluated based on their response. Accordingly, a future study is suggested to be carried out using the longitudinal method to examine the multi-dimensional impact of child sexual abuse and the development/progress they show in the process of psychosocial support they are provided.

Implications

All children are at risk of sexual abuse irrespective of their sex, age, physical condition and the life style they lead their shows that children require closer supervision by parents and responsible and emotionally matured care givers.

Studies focusing on important factors (e. g poverty and social and cultural climate in multi-cultural society) to sexual abuse can be used to get ways of reducing risk of victimization and increase prevention mechanisms.

More comprehensive nation-wide research on sexual violence against children may bring out the whole picture of the issue assisting for policy making, preventive measures and therapeutic interventions.

Table 4.

Description of the Sexual Abuse Incidence, Addis Ababa, 2006.

| Variables | Frequency | % |

| Place of Incident | ||

| Victim's home | 39 | 60.9 |

| School | 3 | 4.7 |

| Hotel room | 2 | 3.1 |

| Sport field | 2 | 3.1 |

| Neighbor | 4 | 6.3 |

| Unknown* | 14 | 21.9 |

|

Time of the sexual incidence |

||

| Morning | 13 | 20.3 |

| Afternoon | 12 | 18.8 |

| Evening | 39 | 60.9 |

| Way of abuse | ||

| By trickery | 37 | 57.8 |

| Use of force/threat | 23 | 35.9 |

| Using drug | 4 | 6.3 |

| Total | 64 | 100 |

either they do not know, remember or unwilling to mention

Table 5.

Summary of major psychological and physical experiences as a result of the sexual victimization.

| Psychological reactions | Physical reactions |

| -Symptoms of anxiety (nine respondents) | -Pain during urination |

| -Feeling lonely (five respondents) | -Repeated heart attack |

| -Easily irritated | -Abdominal pains |

| -Verbal and physical aggressiveness | |

| - Frequently break down | |

| -Attempted to run away from home | |

| -Fear of males | |

| -Poor academic performance | |

| -Attempt to commit Suicide |

Acknowledgments

The material and financial support for this study was secured from the Office of Research and Publication, Jimma University. Besides I extend our heartfelt gratitude to persons who co-operated with me during data collection and data entry.

References

- 1.United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York: United Nations; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terry KJ, Tallon J. Child Sexual Abuse: A Review of The Literature. The John Jay College Research Team; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finkelhore D. Current Information on the Scope and Nature of Child Sexual Abuse. Future of Children. 1994;4(2):31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cossins A. Masculinities, Sexualities and Child Sexual Abuse. The Netherlands: Kluwer Law International; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein S. The Sexual Exploitation of Children: A Practical Guide to Assessment, Investigation and Intervention. 2nd ed. CRC Press LLC; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dominguez Z, Nelke F, Perry D. Encyclopedia of Crime and Punishment. Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire Group; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelhor D. Sexually Victimized Children. USA: Macmillan Company; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkelhor D, Leatherman D. Children as Victims of Violence: A National Survey. Pediatrics. 1994;94(4):413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gobena D. Child Sexual Abuse in Addis Ababa High Schools: Forum on Street Children-Ethiopia (FSCE) Addis Ababa: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dereje W, Abebe G, Jayalakshmi S. Child Sexual Abuse and its Outcomes among High School Students in South West Ethiopia. Tropical Doctor. 2005;36(3):137–140. doi: 10.1258/004947506777978325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lakew Z. Alleged Cases of Sexual Assault Reported to Two Addis Ababa Hospitals. East African Medical Journal. 2001;78(2):80–83. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v78i2.9093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darkness to Light (2001–2005) Statistics. From http://www.darkness2light.org/KnowAbout/statistics_2.asp Retrieved September 22, 2006.

- 13.Rape & Sexual Abuse Center, author. Education Statistics (2002) From http://www.rasac/education/statistics.html (RSAC) Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- 14.Yemataw W. The Psychosocial Consequences of Child Sexual Abuse in Ethiopia: A Case-Control Comparative Analysis. Family & Community Health. 2008;31(1):24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bogorad B. Sexual abuse: Surviving the Pain The American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress. 1998. http://www.child/survivers/violence.htm, Retrieved November 3, 2004.

- 16.Ogunyemi O. Knowledge and Perception of Child Sexual Abuse in Urban Nigeria: Some Evidence from a Community-Based Project Reprod. Reproductive Health. 2000;4(2):44–53. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tadesse H. Marketable Skills/Viable IGA's for Sexually Abused and Exploited Children in Bahir Dar City; Forum on Street Children-Ethiopia (FSCE) Addis Ababa; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelhore D. Child Sexual Abuse: New Theory and Research. USA: The Macmillan Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]